Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus (SPiL Plus)

versão On-line ISSN 2224-3380

versão impressa ISSN 1726-541X

SPiL plus (Online) vol.65 Stellenbosch 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.5842/65-1-974

PART 3: DYNAMIZATION OF SYNCHRONY - A TYPOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE

When verbs 'stay (and) go' together: Pseudo-coordination in Jul'hoan and !Xun

Lee J. Pratchett

CIBIO-InBIO, Universidade do Porto, Portugal | Institute for Asian and African Studies, Humboldt-Universitat zu Berlin, Germany. E-mail: ljpratchett@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Multi-verb constructions are an areal feature of Kalahari Basin Area languages ("Khoisan"), a Sprachbund comprising the Kx'a, Tuu, and Khoe-Kwadi families. Presently, these languages are characterised by two distinct multi-verb constructions with specific distributions: strictly contiguous serial verb constructions in Kx'a and Tuu correspond to multi-verb constructions involving a morphophonological linker, or "juncture", in Khoe-Kwadi. This paper describes an additional multi-verb construction, namely pseudo-coordination. Drawing on a corpus of spontaneous discourse data, this paper demonstrates the rise of pseudo-coordination from a biclausal construction in Jul'hoan and !Xun (Ju, Kx'a). The comparative analysis highlights the verbs that typically arise the context of pseudo-coordination and the resulting functions. This paper describes the polygrammaticalisation resulting from pseudo-coordination, including other multi-verb constructions.

Keywords: Jul'hoan; !Xun; Khoisan; multi-verb constructions; pseudo-coordination; serial verb construction; grammaticalization; posture verbs

1. Introduction

1.1 Background

Monoclausal, multi-verb constructions are an areal feature of Kalahari Basin Area languages (aka "Khoisan"), a Sprachbund comprising the Kx'a, Tuu, and Khoe-Kwadi language families (Güldemann 1998; Güldemann & Fehn 2017). Some of these constructions have been analysed by different researchers as serial verb constructions (henceforth SVCs). Aikhenvald's (2006) prototype-approach defines an SVC as:

[A] sequence of verbs which act together as a single predicate, without any overt marker of coordination, subordination, or syntactic dependency of any other sort. Serial verb constructions describe is conceptualized as a single event. They are monoclausal; their intonation properties are the same as those of a monoverbal clause, and they have just one tense, aspect, polarity value. SVCs may also share core and other arguments. Each component of an SVC must be able to occur on its own. Within an SVC, the individual verbs may have same, or different, transitivity values.

Aikhenvald (2006:1)

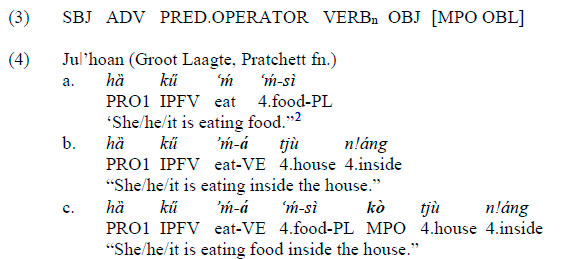

This paper focusses on distinguishing distinct multi-verb constructions (MVCs) across Ju languages. Verb serialisation in Ju is strictly contiguous, also known as nuclear-root serialisation (e.g., Foley & Van Valin 1984). As such, non-subject/agent participants never intervene between the participating verbs in SVCs in Ju. Tense-aspect is marked once per construction before the verbal complex. An example from Jul'hoan is provided in (1). Another SVC construction type is recognised by some authors. In this construction type, the tense-aspect markers are described as "post-posed", appearing between the first and second verb (e.g., König 2010a; König & Heine 2015:103-104). An example from !Xun is given in (2). Here, the aspect marker appears to be an enclitic to V1.

The primary goal of this paper is to provide a thorough analysis of the MVC illustrated in (2), and to discern if and how it relates to SVCs. The paper is structured as follows. Section 1 continues with some relevant features of the Ju languages (§1.2), including remarks on syndetic and asyndetic clause linkage, followed by a brief overview of SVCs in Ju (§1.3). Section 2 presents a cross-dialectal analysis of the "irregular SVC" type, which, by way of a bottom-up, text-based approach, I shall demonstrate is derived from pseudo-coordination. The corpus includes sources transcribed by mother-tongue transcribers, which provide unique insights into wordhood judgements and distinct grammaticalisation pathways. Section 3 provides some suggestions for how the different constructions addressed in the paper potentially relate diachronically. Some conclusions and avenues for future research are summarised in section 4.

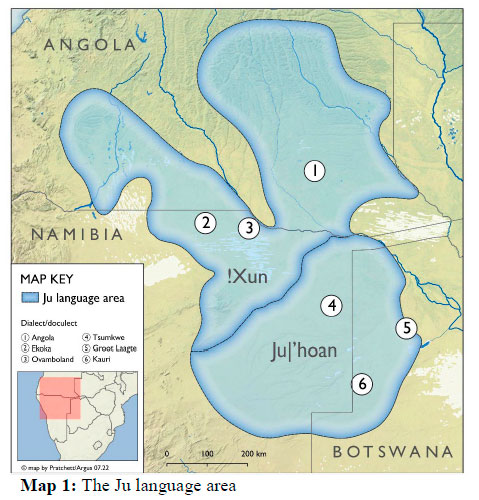

1.2 Ju languages: Jul'hoan and !Xun

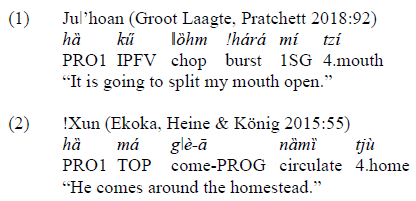

Jul'hoan and !Xun are the principal languages (dialect clusters) of the Ju language complex, itself one of two branches of the Kx'a family (see also Heine & König 2015:22ff; see Sands 2010 for a phonologically motivated classification)1. Ju is spoken by hunter-gatherer communities across southern Angola, northern Namibia, and northwestern Botswana. Ju is a highly isolating language with two main open word classes, namely nouns and verbs. An important property of Ju nouns is grammatical gender, which is conflated with number and is reflected through the agreement behaviour of noun forms with various pronouns. The pronominal gender system involves between four and five agreement classes and as many as seven genders (Pratchett 2021; also, Güldemann 2000). Except for a closed class of verbs with number-sensitive suppletive stems, Ju verbs do not inflect for person or number. Most property or descriptive words - adjectives in many other languages - are intransitive verbs in Ju. There are no ditransitive verbs (König 2010b). An elaborated clause structure is schematised in (3). The order of constituents is relatively fixed, although the only constituent necessary for a clause is the verb. Within canonical (pragmatically unmarked) clauses, the initial nominal position conflates the two roles of semantic subject/agent and pragmatic topic in a grammatical subject (= SBJ) relation. There is no case marking in Ju languages (pace König 2008a). Transitive verbs in Ju permit maximally one postverbal noun phrase (= 'OBJect') without any flagging or verbal inflection, as in (4a). A valency external postverbal participant triggers verbal inflection by means of the valency-external (= VE) suffix -a, as in (4b). As such, three-place predicates with transitive verbs trigger verbal inflection and the additional postverbal participant (= 'OBLique') is systematically encoded as valency-external by means of a multi-purpose oblique (= MPO) preposition, as in (4c). It is also possible to invert the order of postverbal participants with no obvious change in meaning (Dickens 2005:39).

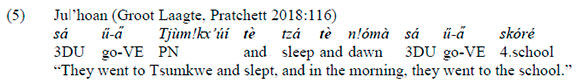

The default verbal coordinators tà in !Xun or tè in Jul'hoan link clauses, as illustrated in (5). Clauses (or utterances) consisting of solely a verb are typically coordinated this way.

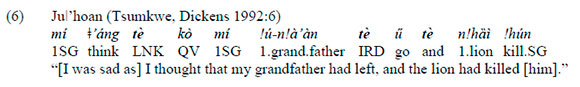

Example (6) attests to the polyfunctionality of tè in Jul'hoan, with functions including conjunctive and adversative coordination, introducing purpose clauses, and marking indirect discourse. The second instance of tè in (6) appears between \ 'áng 'think' and the quotative verb ko 'say'. Here, coordinator tè has become a semantically bleached linker morpheme (LNK) in a quotative construction (Güldemann 2008a:158, 560-561).

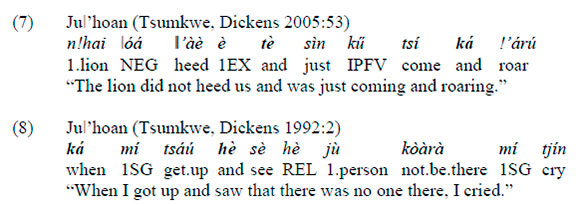

The morpheme ká is described as a coordinator for clauses expressing simultaneous events, as illustrated in (7).3 Ká also heads subordinate clauses. Within subordinate clauses, the verbal coordinators hè~yè are used, as shown in (8).

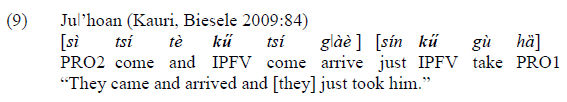

Asyndetic clause linkage is also found in Ju, as illustrated by (9). In the absence of qualitative research, asyndetic coordination is likely a matter of speaker style (cf. "narrative SVCs" in Pawley 2008). Square brackets demarcate clause boundaries.

1.3 Serial verb constructions in Ju

Dickens (2005:81) defines an SVC in Jul'hoan simply as "two verbs in a sequence". This is expanded upon by Heine & König (2015:91-92). The present definition retains some but not all of these properties, as it includes constructions that I do not analyse as SVCs (see §2).

(a) A monoclausal, uninterrupted sequence of two or more verbs acting together as a single predicate, without a morphological expression of dependency;

(b) The verbs synchronically can function independently as the predicate nucleus;

(c) The word order is iconic and the verbs are strictly contiguous;

(d) When present, polarity, tense, and aspect is marked once before the verbal complex and holds for the entire construction;

(e) Adverbs of different kinds precede the verbal complex;

(f) Argument sharing, albeit common, is not obligatory;

(g) If present, derivational morphology is used once on the final verb.

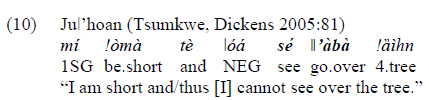

SVCs are typically described as expressing a single, even if complex, event. However, as defining eventhood can be problematic, eventhood is not elaborated on here (see Bisang 2009; Haspelmath 2016). With respect to argument sharing, several different construction types are found (for more details see Heine & König 2015:97). In (10), the participating verbs share the subject/agent and the object. Note that in this particular case, the subject/agent referent is not overtly expressed as part of the SVC. Zero anaphor is common in Ju. In the following examples, verbs in the SVC are presented in bold.

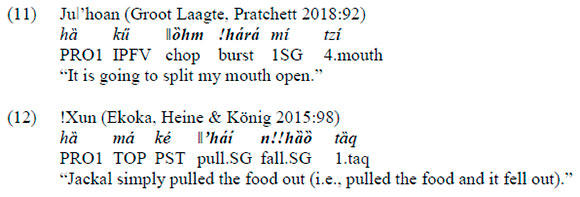

In (11) and (12) only the post-verbal argument is shared, serving as the object of V1 and the subject of V2. In typological literature, this construction is described as a "switch function" SVC (Aikhenvald 2006:14ff).

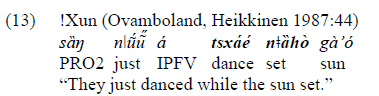

Some SVCs in Ju lack argument sharing completely, as illustrated by (13) which involves two intransitive verbs. This example could be described as an "event-argument" SVC, where an event is expressed by one part of the SVC and its temporal or locational specification is expressed by the other (Aikhenvald 2006:18-19; cf. "overlapping clause" in Ameka 2006).

Aikhenvald (2006:1, 35) distinguishes between asymmetrical and symmetrical SVCs, i.e., whether all verbs are sourced from open semantic classes (=symmetrical), or from a mix of open and closed semantic classes (=asymmetrical). In symmetrical SVCs both verbs contribute their lexical semantics to the expression of the event; in an asymmetrical SVC one verb (the "light verb") expresses distinctions with respect to aspect, direction, and modality, which hold for the event expressed by the other verb. This dichotomy has been attributed to Ju languages in previous studies (e.g., König 2010a; Heine & König 2015:99-103). In the present paper, however, I shall not uphold these categories in Ju, as I find no formal grounds for doing so. We return to this point briefly in section 3.

2. Verbs that 'stand (and) go' together: pseudo-coordination in Ju

We turn now to the formally divergent kind of "irregular SVC" highlighted in the introduction. This has been described as an SVC involving a closed class of verbs in V1 position which "have their tense aspect markers basically between the two verbs" (Heine & König 2015:103-104). An example is given below.

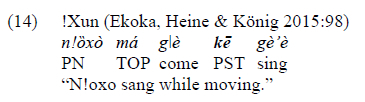

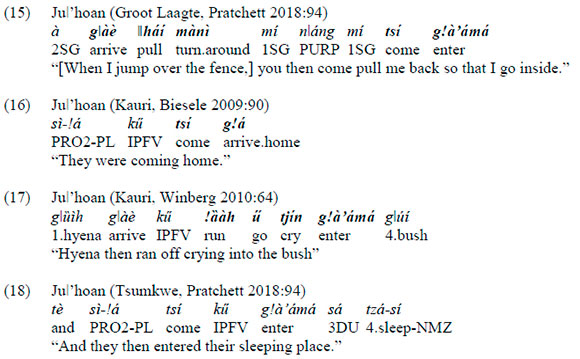

According to current analyses, the "post-posed" tense-aspect markers are moved from the canonical preverbal position to the position between the two verbs. This behaviour is not explained or motivated in the analysis. The formal variation between this construction and a canonical SVC is especially pertinent because, as the authors note, it seemingly arises with a closed class of verbs that express "schematized (grammatical) meaning when used in an SVC" (Heine & König 2015:103). This would suggest morphological evidence for distinguishing two subtypes of SVCs in Ju, ostensibly providing a form-function correlation for the symmetrical-asymmetrical dichotomy. However, one must be mindful that the morphological expression of tense and aspect is not obligatory in Ju. Thus, the verbs occurring in a MVC with "post-posed" tense-aspect marking are also found in MVCs without tense-aspect marking. This effectively results in three construction types: zero tense-aspect marking, as in (15); default tense-aspect marking, as in (16); and non-canonical tense-aspect marking, as in (17) and (18). For the present purposes, all examples involve deictic motion verbs tsí 'come' or g\àè 'arrive'.

How else might the divergent construction be explained? The aspect marker in Ju reliably demarcates the beginning of the predicate nucleus. Hence, the verbs that arise before the aspect marker may alternatively be viewed as external to the predicate nucleus, possibly pushed out due to grammaticalisation in an erstwhile MVC (Güldemann 2013:411; Pratchett 2018:93). This idea is rendered more credible considering descriptions of tsí 'come' and g\àè 'arrive' as markers of contrastive altrilocality (Pratchett 2018:93) and of "new events" (Heine & König 2015:105). Viewing the verbs as external to the predicate nucleus has an important implication: synchronically, the constructions themselves do not qualify as SVCs. Furthermore, whether the source construction is an SVC, however plausible, is not a foregone conclusion.

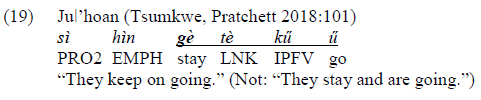

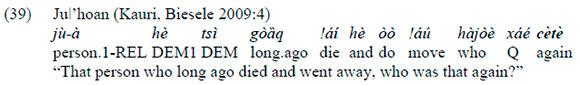

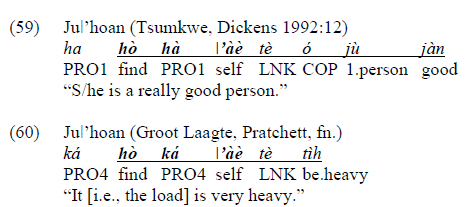

In the following, I demonstrate that the non-canonical placement of tense-aspect can help to identify a distinct, non-serialising construction. Spontaneous discourse texts representing various Ju varieties were scoured for instances of MVCs with non-canonical tense-aspect marking (see table 1). This was facilitated by previous studies of Ekoka !Xun and the verbal collocations identified therein (cf. Heine & König 2015:102-103). The comparative study unveiled a more complete picture of the construction profile, its variation, and the participating verbs. In its fullest and most complex version, the construction involves an initial verb (V1) that is separated from the main semantic verb (V2) by a morpheme that is identical in form to the clause coordinators, usually tè in Jul'hoan and tà in !Xun (see §1.2). When tense-aspect is morphologically expressed, it appears immediately before V2, as in (19).

The construction in (19) is formally indistinguishable from a string of coordinated clauses, but semantically such an interpretation is clearly awkward. Historically, verbal coordination is the plausible origin, with the clausal coordinator developing into a desemanticised linker (LNK) in a monoclausal multi-verb expression. This profile conforms well with cross-linguistic appraisals of pseudo-coordination (e.g., Ross 2021; Guisti, Di Caro & Ross 2022).4Grammaticalisation can result in the omission of the linker entirely, resulting in constructions plausibly analysed in some frameworks as SVCs. This would provide evidence for verb serialisation in Ju derived from clause fusion (see §3). However, pseudo-coordination also gives rise to structures that are segmentally indistinguishable from SVCs, but which do not meet all the criteria in subtle yet important ways. Such fuzzy boundaries seem cross-linguistically characteristic of these constructions, an important factor when distinguishing different MVCs (e.g., Ross 2022). The three attested structural variants subsumed here under pseudocoordination are provided in figure 1. The properties of the pseudo-coordination are summarised in figure 2. The next subsections are organised according to the verbs regularly found in the context of pseudo-coordination. Instances of the constructions are underlined.

2.1 Existential verbs

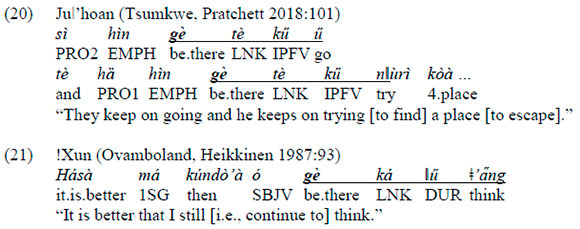

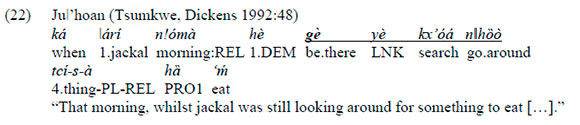

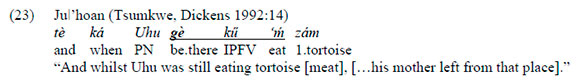

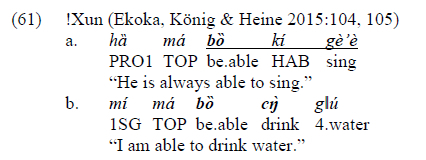

The verb gè 'be there~stay~remain' was not previously identified as a potential verb of interest; however, it provides robust evidence for pseudo-coordination. Ruling out clause coordination is crucial. Thus, utterances which would yield antonymic readings as coordinated clauses are ideal, such as (20a) from Jul'hoan, which features the construction twice. The first instance includes gè 'be there~stay~remain' and the motion verb ü 'go', which would yield an awkward interpretation if viewed as coordinated clauses. The second instance comprises gè and nlùri 'try~attempt'. This could be construed as two clauses: however, the utterance is better analysed as being composed of the repetition of a particular template, serving to contrast two (not three or four) events, namely "going" and "trying". The existential verb in pseudo-coordination typically results in a progressive reading (cf. Heine & Kuteva 2002:276). Example (21) shows the presence of the linker in the pseudo-coordination construction in !Xun, demonstrating the presence of the morphologically heavier construction in both branches of Ju.

In subordinate clauses, the linker takes the form hè~yè, as in (22). This is the expected form of a coordinator in subordinate clauses in Ju (see §1.2). In (23), the linker is omitted, resulting in a segmentally more compact construction.

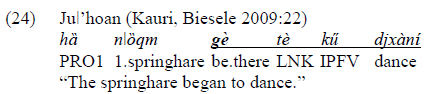

In addition to progressive aspect, the construction with gè also denotes current relevance for an event expressed in a following clause, as illustrated by (22) and (23) above. An inchoative reading is also possible, as shown in (24).

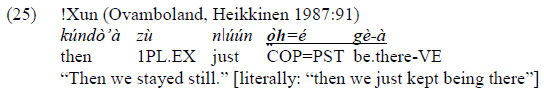

In !Xun, the existential verb gè overlaps functionally with the equational copula oh (Heine & König 2015:81; Güldemann & Pratchett, forthcoming). It is therefore unsurprising that in !Xun the equational copula oh also appears in the pseudo-coordination, as shown in (25) without a linker. Further morphological reduction is also observed: the tense marker ká undergoes the loss of the initial consonant and seemingly behaves as an enclitic to V1 (Heikkinen 1987:91).

2.2 Posture verbs

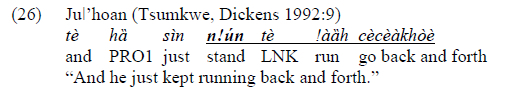

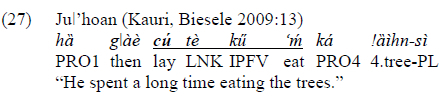

Pseudo-coordination is found with posture verbs 'lay', 'sit' and 'stand'.5 As aforementioned, optimal evidence comes from utterances which cannot be interpreted as coordinated clauses, or in terms of accompanied position (cf. Heine & König 2015:71-72). Such is the case for the next examples in which the posture verbs form progressive expressions. Such grammaticalisation is well described both areally (e.g., Kilian-Hatz 2002) and cross-linguistically (e.g., Bybee et al. 1994:127; Kuteva 1999; Newman 2002). It is particularly curious that different posture verbs form progressive expressions with dynamic verbs, with combinations such as 'stand (and) run' in (26), and 'sit (and) move' and 'lay (and) herd' in (27). We revisit this briefly at the end of the paper.

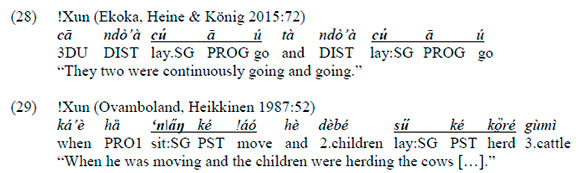

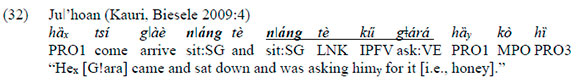

The linker is typically preserved with posture verbs in Jul'hoan, a tendency that holds for Jul'hoan more generally (cf. figure 1). This suggests that grammaticalisation is more advanced in !Xun. This is further evidenced through the loss in !Xun of an important property of some posture verbs in Ju, namely stem suppletion that agrees with the number value of nominal arguments. In (28), the non-singular subject should trigger the number-marked verb form, gllà 'lay (PL)'. The same applies to the second instance of pseudo-coordination in (29), where the plural subject dèbé (cf. dàba [1] 'child') should also trigger the form gllà 'lay (PL)'.

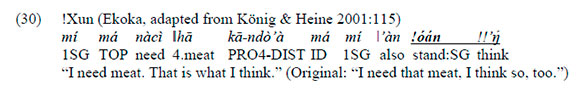

As the morphological expression of tense-aspect is not obligatory in Ju, the omission of the linker can result in structures that are segmentally indistinguishable from SVCs, as shown in (30). The translation offered by the authors does not suggest accompanied posture.

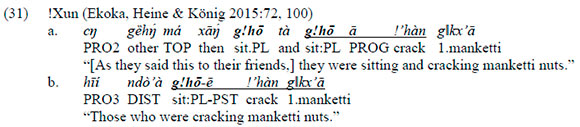

There are cases which permit a reading in terms of accompanied posture. However, accompanied posture is seemingly rendered explicit by using the posture verb in an additional independent clause. Compare the difference in the original translations in (31a) and (31b) from !Xun, as well as (32) from Jul'hoan.

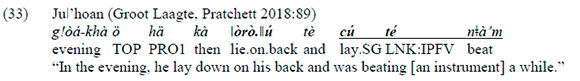

It is in relation to posture verbs that the corpus revealed constructions with other kinds of formal variation and morphological reduction. In Jul'hoan, the aspect marker kü is sometimes omitted segmentally, resulting in a floating high tone that is hosted by the morpheme immediately to the left (Pratchett 2018:89, 116). In (33), the floating tone is hosted by the linker changing its underlying tone from low to high.

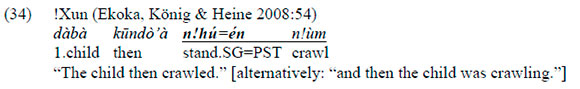

Example (34) provides another case of reduction to tense-aspect markers. Here, the past marker kë is reduced to an enclitic, and both the nasality and the tone of the final vowel of the verb lexeme spreads onto the enclitic (cf. [25]).

2.3 cè 'do again'

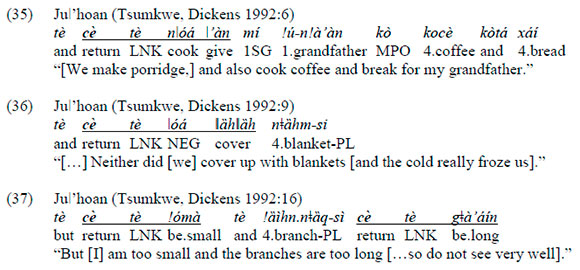

Pseudo-coordination featuring cè 'to return' as V1 yield additive and excessive expressions, as in (35), (36), and (37), respectively.

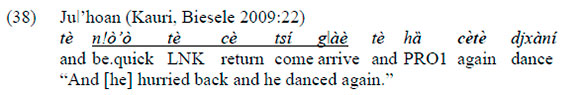

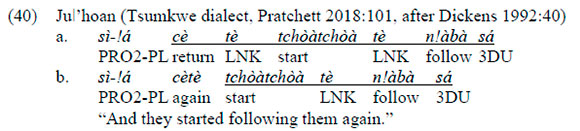

The examples above suggest the retention of the linker with the verb cè in Jul'hoan. However, texts transcribed by mother tongue transcribers provide some unique and important insights into speakers' expert wordhood judgements.6 In (38), cè tè is codified conjunctively as cètè and translated as 'again'.

The wordform cètè conforms to the relatively strict phonotactic rules in Ju, which permit only CVV, CVCV, and CVN lexical wordforms. Most grammatical words are CV in shape. Thus, underlyingly, cè is phonologically /fèè/. However, a sequence of two identical vowels is likely to be realised short phonetically. Thus, the grammaticalised verb form and the desemanticised coordinator can combine into a new CVCV word. This is not possible with CVCV roots or CVV roots with contrastive vowels because the resulting CVCVCV and CVVCV wordforms violate the language specific phonotactics. As such, the case of cè demonstrates the precise and varied ways a single MVC can develop, depending on the properties of the verbs. In (39), cètè appears clause finally and it is clearly independent of the pseudo-coordination construction.

Given this speaker-centric evidence for word formation, transcribing cètè disjunctively should probably be avoided. In addition to avoiding prescriptivism by outsider linguists, there are issues that are more pertinent to the present study. In its original transcription, (40a) could be analysed as a multi-word MVC entailing two linkers and three verb forms: cè 'return', tchôàtchôà 'start' (cf. §2.5), and the main semantic verb nlàbà 'follow' (cf. Pratchett 2018:101). It is noteworthy that such complex cases of pseudo-coordination seemingly always involve the form cè. As such, and in keeping with community expertise, these cases are more suitably analysed as entailing the adverb cètè 'again', as in (40b).

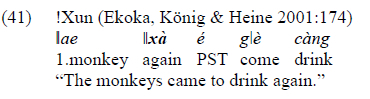

In !Xun, the adverbial expression 'again' is expressed by \\xà~xa (Heikkinen 1987:26). There is no evidence of \\xà functioning as a predicate, hence it does not form MVCs.

Fehn (pers. comm.) suggests that \\xà may in fact be a borrowing from Khoe languages. This would be one of several adverbs borrowed into Ju from Khoekhoe (e.g., káísé 'very' < kaisè 'very', kaï 'big' in Standard Namibian Khoekhoe. Cf. Haacke & Eiseb 2002:725). Such borrowings offer a morphologically lighter expression. One might hypothesise that, particularly in the case of bilingual speakers or where contact with Khoekhoe languages is more pronounced, as is the case with !Xun communities, derived adverbs adversely influence the use of pseudo-coordination (see also section 2.4).

2.4 Manner verbs

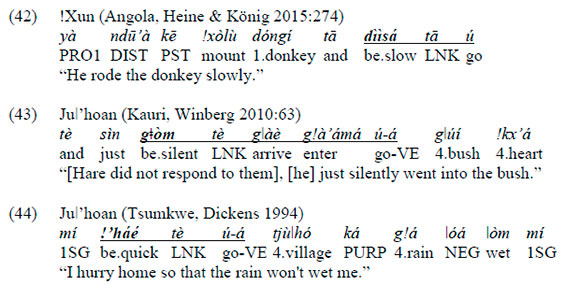

Pseudo-coordination is a prime context for certain manner verbs, in which they adverbially modify the main semantic verb (cf. Heine & König 2015:274). This is illustrated with dllsa 'be slow' in (42), g\om 'be silent' in (43), and ! 'háé 'be quick' in (44).

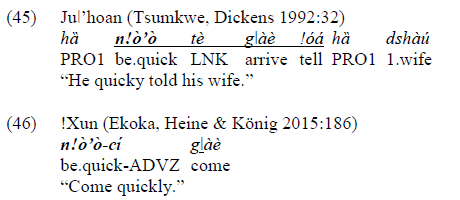

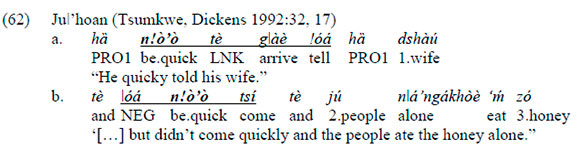

Derivational morphology is found with some manner, such as the adverbialiser suffix -sí/-cí (cf. Heine & König 2015:186). Compare n!ô'ô 'be quick' in the pseudo-coordination construction in (45) and n!ô'ôci 'quickly' as a deverbal adverb in (46).

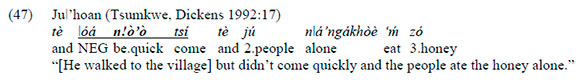

In the corpus, the linker is always retained with manner verbs in affirmative contexts. However, under negation, it is always dropped. Consider (47) in which the negation marker is followed by an uninterrupted chain of verb forms: n!ô'ô 'be quick' and tsí 'come'. The expression is formally indistinguishable from an SVC. However, the SVC analysis is incompatible as the verbs do not have the same polarity value: in the example, the subject referent is not quick, but come it does, nevertheless.

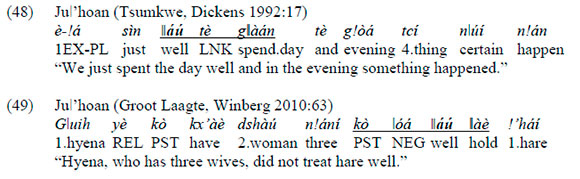

A similar pattern is attested with Wáú 'do well', as shown (48) and (49). Conceivably, negation offers a source of construction-specific variation. This hypothesis would benefit from further research, such as targeted elicitation with the other verb groups discussed in this paper.

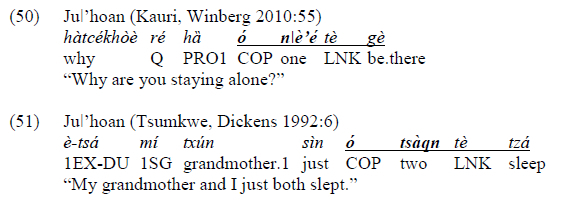

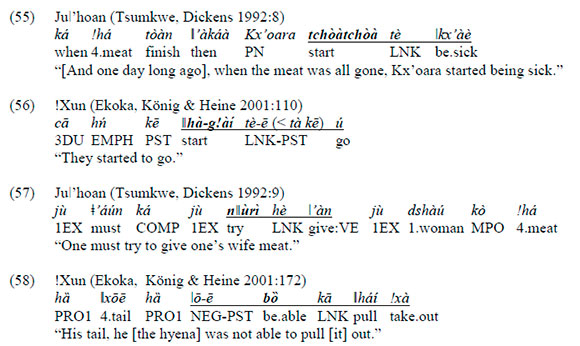

Pseudo-coordination also arises with other kinds of manner expressions, such as adverbial expressions 'alone' and 'both'. These are rendered by a non-verbal predicate involving the equational copula ó and a numeral in V1 position followed by the main semantic verb, as in (50) and (51). The linker is always present.

2.5 Auxiliary verbs

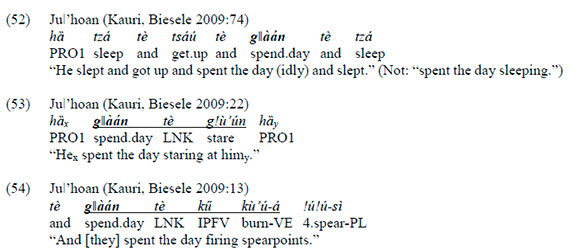

Another group of verbs frequently observed in the pseudo-coordination are subsumed here as auxiliary verbs. This includes gWaán 'to spend the day'. In (52) gWaán is the predicate nucleus in one of a string of coordinated clauses composed solely of verbs, as is typical in Ju. Comparison with (53) and (54) shows that, segmentally, coordination is indistinguishable from pseudo-coordination. Semantically, however, the constructions are quite distinct. In (52) gWaán is a distinct event, whilst in (53) and (54) g||áán provides temporal specification for the event expressed by the main verb.

Other auxiliary verbs include tchoàtchoà 'start,' nlùri 'try' and bo 'be able', illustrated in the following examples, respectively.7 There is a clear tendency for auxiliary verbs to retain the linker, which may be indicative of an earlier stage of grammaticalisation. This is also reflected in the occurrence of tense-aspect markers with the auxiliary verb, as in (56) and (58).

Another reason why constructions with auxiliary verbs exhibit a lesser degree of grammaticalisation might be the stronger "predicative force" of these verbs. Context and common ground providing, the ellipsis of the main semantic verb still renders a well-formed utterance with comparable meaning. This is not the case for pseudo-coordination with posture verbs, where ellipsis of the main semantic verb would result in a posture predication.

It is noteworthy that Dixon (1991:88) groups the auxiliary verbs discussed here (e.g., 'start', 'be able', 'try', and 'to hurry') under the label "secondary verbs", verbs which "provide semantic modification of some other verb". Aikhenvald (2018:60-62) observes that these verbs typically form a subtype of asymmetrical SVC called the "secondary concept" type. In Ju, we see that these verbs form a multi-word MVC that is quite distinct from an SVC, although pseudo-coordination may develop into structures that resemble contiguous SVCs in Ju. This is discussed in section 3.

2.6 Summary

The verbs commonly found in the context of pseudo-coordination and the resulting functions are summarised in table 2. The presumed grammaticalisation of the erstwhile biclausal structure is more advanced with certain verbs, such as posture verbs expressing progressive aspect (see §2.2). This is reflected in the gradual morphological reduction, such as the omission of the linker morpheme or the enclitic-like behaviour of the tense markers. Both processes result in an increasingly morphologically lighter, monoclausal construction.

Finally, there is another kind of manner expressions that requires a construction identical to pseudo-coordination but slightly different from the templates proposed earlier in figure 1 and for this reason is discussed separately. This concerns the somewhat idiosyncratic intensifier expression found in Jul'hoan (cf. Dickens 2005:90). In (59) and (60) 'very~really' is rendered by the transitive verb ho 'find-see' and a noun phrase comprised of a pronoun that agrees with the subject/agent, and the reflexive marker |'àè 'self. This effectively serves as a valency-reducing operation, thus bringing the construction in line with the other verbs in the V1 position.

3. On the rise and fall of the different multi-verb constructions

This paper describes the rise of MVCs from biclausal structures, a process also known as "clause fusion" (Aikhenvald 2018:196-201). In Ju, clause fusion results in a monoclausal MVC, with a surface structure that remains identical to coordinated clauses, thus referred to as pseudocoordination. With certain verbs, the desemanticised coordinator is dropped. The basic evolution of these constructions is schematised in figure 3. There is an important caveat, namely that it should not at this stage be ruled out that several distinct biclausal constructions develop into the constructions summarised presently as pseudo-coordination (Güldemann, pers. comm.). This merits further research. If this does turn out to be the case, it would further underline one of the important takeaways from the current paper, namely how surface structures are sourced from multiple constructions.

Even after the omission of the linker, the construction retains an important clue as to its biclausal origins, namely in the position of tense and aspect markers between the participating verbs. In !Xun, these tense-aspect markers can even behave as enclitics on the initial verb. This is strikingly distinct from the profile of SVCs in both !Xun and Jul'hoan in which tense-aspect precedes the verbal complex (see §1.3). As such, the present analysis highlights the risk of a prototypical approach to characterising construction types. However, in the absence of the linker and tense-aspect markers, the two construction types become indistinguishable, as illustrated in (61a) and (61b).

Pseudo-coordination may, however, only superficially resemble an SVC. Such is the case under negation, where the coordinator is seemingly dropped resulting in a verb-verb structure but where the verbs do not share the same polarity value, as seen previously (cf. [45] and [47]), repeated as (62a) and (62b) for convenience.

Aikhenvald (2018:202), in summarising research by Creissels et al. (2008), states:

In a fundamental study of morphosyntactic features shared by African languages, Creissels et al. (2018:113) explicitly state that there is no evidence that serial verb constructions in Chadic and other African languages 'arose from the combination of clauses.'

(Aikhenvald 2018:202, my emphasis)

On reflection, I interpret the statement by Creissels et al. (2008:113) as being restricted only to Chadic languages. In any case, the present study provides proof of clause fusion resulting in SVCs in an African language via the intermediary step of verbal pseudo-coordination. However, clause fusion as outlined in the present study only results in a certain kind of SVC. For example, the initial verb is always intransitive and in the resulting SVC it specifies manner, modality, or aspectual distinctions. In typological literature, such SVCs are frequently referred to as "asymmetrical" SVCs, in contrast to "symmetrical" SVCs in which all verbs contribute lexically to the expression of the event (e.g., Aikhenvald 2006). There is no evidence that the kind of clause fusion described here derives multi-verb structures in which each verb contributes lexically (i.e., "symmetrical" SVCs). If so, one would expect to see variation with respect to the position of tense-aspect markers in such contexts, which is seemingly never the case.

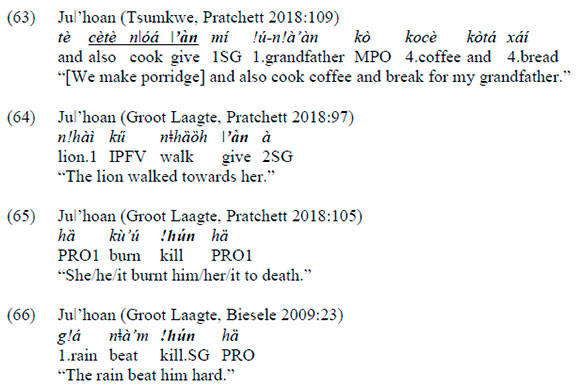

Similarly, the present paper does not suggest that clause fusion is a potential source of SVCs in which the initial verb is the main semantic verb, and the final verb takes on a more functional role. Consider the cases below showing the different functions of l'àn 'give' and lhún 'kill' as V2 in SVCs. Examples (63) and (64) show the benefactive and dative interpretations of l'àn 'give'. The cross-linguistic tendency for 'give' to develop such functions is well attested (e.g., Newman 1996:211-223). The reading of l'àn 'give' in (63) is ambiguous, and both transfer of possession and benefactive interpretations are possible. Only discourse context provides clues as to the intended reading: in this narrative, the would-be recipient is asleep at the time of the utterance and a transaction does not take place. Such contexts provide the ambiguity that drives language change (e.g., Traugott & König 1991). Examples (65) and (66) illustrate the reanalysis of SVCs with Ihún 'kill' as V2 towards an intensifier expression comparable with degree resultatives in English, e.g., 'to laugh to death' (cf. Hoeksema & Napoli 2019).

These few examples support the hypothesis that in Ju languages the grammaticalisation of V2 verbs is the result of regular occurrence in SVCs (see also Bisang 2009:808-810). Occasionally, discourse context is the only means of identifying the semantics of a construction. This makes it difficult from a language-specific perspective to draw a distinction in formal terms between two SVC subtypes, such as symmetrical and asymmetrical SVCs. Similarly, it does not make sense from a Ju perspective to homogeneously categorise SVCs in which only one verb expresses the event, and another verb contributes functionally (i.e., asymmetrical SVCs): in Ju, these SVCs are sourced from a pool of syntactically strikingly heterogenous constructions.

4. Conclusions and future research

The present analysis of pseudo-coordination contributes to a more exhaustive description of MVCs in Ju. The study simultaneously makes an important contribution from the study of African languages to typological studies on pseudo-coordination, which has been dominated by European languages (Guisti et al. 2022:6). The paper has stressed the polygrammaticalisation of verbal pseudo-coordination, which gives rise to adverbs, SVCs, and other non-serialising MVCs. Simultaneously, the results of the study also underline the many-to-one pattern in Ju with respect to the development of what is synchronically a single construction type, such as SVCs. The present study would greatly benefit from further investigation, such as exploring the exact conditions under which the interverbal segments can be dropped, and phenomena like the suprasegmental realisation of aspect.

In closing, I wish to highlight two ways in which the present study is of interest to the ongoing description of Kalahari Basin Area languages in particular. Section 2.2 highlighted the quirky progressive expressions composed of different posture verbs and dynamic motion verbs, such as 'sit (and) run' and 'lay (and) go'. Nakagawa (2016) describes a similar phenomenon in Glui, an unrelated Kalahari-Khoe language (Khoe-Kwadi) spoken in the central Kalahari. Based on experimental fieldwork, Nakawaga proposes that in additional to generic progressive expressions, Glui distinguishes posture-specific progressive expressions that, with dynamic verbs, "consider the movement of the object within the field of view of the speaker" (Nakagawa 2016:113). Thus, LIE-progressives "indicates the object's horizontal movement", i.e., movement that crosses the speaker's line of vision; by contrast, SIT-progressives "indicates the object's static position, lacking horizontal and vertical movement" (Nakagawa 2016:113). Future research should consider the areality of such posture-specific progressives and investigate the functional load of posture-specific progressives in Ju languages (and beyond).

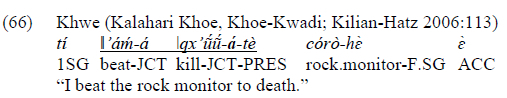

Finally, as aforementioned in the introduction, a heterogenous group of constructions across Kalahari Basin Area languages have been labelled as SVCs. Whilst SVCs in Kx'a and Tuu are strictly contiguous (cf. KieBling 2013 for Tuu), the equivalent constructions in the Khoe family feature a morphophonological linker, also referred to as a "juncture" (e.g., Köhler 1981; Rapold 2014; Vossen 2010). An example is given in (66). Due to the juncture (JCT), there is no consensus amongst specialists on whether the construction satisfactorily meets the definition of an SVC (e.g., Kilian-Hatz 2006) or represents a different type of MVC (e.g., Güldemann & Fehn 2017).

Various analyses of the juncture morpheme have been offered, including suggestions of a grammaticalised copula (Heine 1986), a desemanticised clause coordinator (Elderkin 1986), and an inherited suffix from a periphrastic MVC in an ancestral Khoe-Kwadi language (Güldemann & Fehn 2014). Given the robust evidence for a MVC involving a linker morpheme in Ju languages provided by the present study, the distinction between Kx'a and Tuu languages, on the one hand, and Khoe-Kwadi languages, on the one hand, is narrowed. This is significant because many Khoe languages, particularly Kalahari Khoe languages, are spoken by hunter-gatherer populations who have likely undergone historical language shift - presumably from a language with a profile like Kx'a or Tuu - to the languages spoken by early Khoe pastoralists when encroaching into the eastern Kalahari (e.g., Güldemann 2008b; cf. Pickrell et al. 2012 for a study on genetic admixture across the Kalahari Basin). In earlier research, I identified some formal and functional similarities between the "verb-juncture" construction in Khoe and the then still preliminary description of pseudo-coordination in Ju (cf. "bisected periphrastic construction", Pratchett 2018:232-243), and made the novel claim that "a multi-verb predicate involving a linker morpheme [forming] part of a Ju substrate in Kalahari Khoe languages, whilst still rather radical, is not beyond the realm of possibility" (Pratchett 2018:243). The present analysis of pseudo-coordination across Ju, including insights into the complex underlying nature of the elements at the "verbal juncture", certainly does not detract from original idea. On the contrary, it renders it significantly less radical.

Abbreviations

Arabic numerals when not followed by SG or PL indicate agreement classes.

A - agent, ACC - accusative, ADV - adverb, ADVZ - adverbialiser, C - consonant, CLCO -clause coordinator, COP - copula, DEM - demonstrative, DIST - distal demonstrative, DU -dual, DUR - durative, EMPH - emphatic, EVID - evidential, EX - exclusive, F - feminine, HAB - habitual, ID - identificational, INTR - intransitive, IPFV - imperfective, IRD - indirect discourse, JCT - juncture, LNK - linker, MPO - multipurpose oblique, MVC - multi-verb construction, N - nasal consonant, NEG - negation, NMZ - nominaliser, O - object, PL -plural, PN - proper name, PRED.OP - predicate operator, PRES - present, PRO - pronoun, PROG - progressive, PST - past, PURP - purpose, Q - question marker, QV - quotative verb, REL - relative marker, S or SBJ - subject, SBJV - subjunctive, SG - singular, SVC - serial verb construction, TOP - topic, V - verb or vowel, VE - valency external suffix.

Acknowledgements

This paper was written as part of the project PTDC/BIA-GEN/29273/2017 funded by the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT, Portugal) with additional support from the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science (jSPS KAKENHI #20H000011). I would like to acknowledge the valuable contributions to this paper made by Ines Fiedler, Anne-Maria Fehn, Tom Güldemann, Daniel Ross, and the anonymous reviewers. I am also grateful for the patience and encouragement shown by the volume editors.

References

Aikhenvald, A.Y. 2006. Serial verb constructions in typological perspective. In A. Aikhenvald and R.M.W. Dixon (eds.) Serial Verb Constructions: A Crosslinguistic Ttypology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1-68. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198791263.003.0010 [ Links ]

Aikhenvald, A.Y. 2018. Serial Verbs. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Ameka, F.K. 2006. Ewe serial verb constructions in their grammatical context. In A. Aikhenvald and R.M.W. Dixon (eds.) Serial Verb Constructions: A Crosslinguistic Typology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1-68. https://doi.org/10.1515/lingty-2017-0008 [ Links ]

Beach, Douglas M. 1938. The Phonetics of the Hottentot Language. Cambridge: Heffer and Sons. [ Links ]

Biesele, M. 2009. Jul'hoan Folktales: Transcriptions and English Translations: A Literacy Primer by and for Youth and Adults of the Jul'hoan Community. Victoria, British Colombia: Trafford Publishing. [ Links ]

Biesele, M, L.J. Pratchett and T. Moon. 2012. Jul'hoan and iX'aol'aen documentation in Namibia: overcoming obstacles to community-based language documentation. Language Documentation and Description 11: 72-89. https://doi.org/10.25894/ldd179 [ Links ]

Bisang, Walter. 2009. Serial verb constructions. Language and Linguistics Compass 3(3): 792814. https:doi.org/10.1111/i.1749-818X.2009.00128.x [ Links ]

Bybee, J., R. Perkins and W. Pagliuca. 1994. The Evolution of Grammar: Tense, Aspect and Modality in the Languages of the World. Chicago: Chicago University Press. [ Links ]

Creissels, D., G.J. Dimmendaal, Z. Frajzyngier and C. König. 2008. Africa as a morphosyntactic area. In B. Heine and D. Nurse (eds.) A linguistic Geography of Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 86-150. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511486272.005 [ Links ]

Dickens, P.J. 1992. N\oahnsi o Jul'hoansi masi: A collection of Jul'hoan Reminiscences and Folktales. Unpublished manuscript.

Dickens, P.J. 1991. Jul'hoan orthography in practice. South African Journal of African languages 11: 99-104. https://doi.org/10.1080/02572117.1991.10586900 [ Links ]

Dickens, P.J. 1994. English - Jul'hoan/Jul'hoan - English Dictionary. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe. [ Links ]

Dickens, P.J. 2005. A Concise Grammar of Jul'hoan with a Jul'hoan-English Glossary and Subject Index. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe. [ Links ]

Dixon, R.M.W. 1991. A New Approach to English Grammar, on Semantic Principles. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Elderkin, E.D. 1986. Kxoe tone and Kxoe 'jonctures'. In R. Vossen and K. Keuthmann (eds.) Contemporary Studies on Khoisan. Hamburg: Helmut Buske. pp. 225-235. [ Links ]

Foley, W.A. and R.D.Van Valin. 1984. Functional Syntax and Universal Grammar. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Güldemann, T. 1998. The Kalahari Basin as an object of areal typology - A first approach. In M. Schladt (ed.) Language, Identity, and Conceptualization among the Khoisan. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe. pp. 137-169.

Güldemann, T. 2000. Noun categorization systems in Non-Khoe lineages of Khoisan. Afrikanistische Arbeitspapiere 63: 5-33. [ Links ]

Güldemann, T. 2008a. Quotative Indexes in African Languages. A Synchronic andDiachronic Survey. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110211450 [ Links ]

Güldemann, T. 2008b. A linguist's view: Khoe-Kwadi speakers as the earliest food-producers of southern Africa. In K. Sadr and F.-X. Fauvelle-Aymar (eds.) Khoekhoe and the Earliest Herders in Southern Africa (Southern African Humanities 20). pp. 93-132. https://doi.org/10.10520/EJC84798

Güldemann, T. 2013. Syntax: IXam. In R. Vossen (ed.) The Khoesan languages. London: Routledge. pp. 419-431. [ Links ]

Güldemann, T. and A.-M. Fehn. 2017. The Kalahari Basin area as a 'Sprachbund' before the Bantu expansion - An update. In R. Hickey (ed.) The Cambridge Handbook of Areal Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 500-526. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781107279872.019

Güldemann, T. and A.-M. Fehn. 2014. A Kwadi perspective on Khoe verb-juncture constructions. 5th International Symposium on Khoisan Languages and Linguistics, Riezlern, July 14-16.

Güldemann, T. and L.J. Pratchett. In preparation. Non-verbal predication in Ju. In P.M. Bertinetto, L. Ciucci and D. Creissels (eds.) Non-verbal Predication: A Typological Survey. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

Gusti, G., V. N. di Caro and D. Ross. 2022. Pseudo-coordination and multiple agreement constructions: an overview. In Gusti, G., V. N. di Caro and D. Ross (eds) Pseudo-coordination and Multiple Agreement Constructions. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. pp. 1-32. https://doi.org/10.1075/la.274.01giu [ Links ]

Haacke, W.H.G. 1999. The Tonology of Khoekhoe (Nama/Damara). Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe. [ Links ]

Haacke, W.H.G and E. Eiseb. 2002. A Khoekhoegowab Dictionary, with an English-Khoekhoe Index. Windhoek: Gamsberg Macmillan. [ Links ]

Haspelmath, M. 2016. The serial verb construction: comparative concept and cross-linguistic generalizations. Language and Linguistics 17(3): 291-319. https://doi.org/10.1177/239700221562689 [ Links ]

Heikkinen, T. 1987. An outline of the grammar of the !Xü language spoken in Ovamboland and West Kavango. South African journal of African languages 7: 1ff. [ Links ]

Heine, B. 1986. Bemerkungen zur Entwicklung der Verbaljunkturen im Kxoe und anderen Zentralkhoisan-Sprachen. In R. Vossen and K. Keuthmann (eds.) Contemporary Studies on Khoisan. Hamburg: Helmut Buske. pp. 9-21. [ Links ]

Heine, B. and C. König. 2008. A Concise Dictionary of Northwestern !Xun. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe. [ Links ]

Heine, B. and C. König. 2015. The !Xun Language. A Dialect Grammar of Northern Khoisan. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe. [ Links ]

Heine, B. and T. Kuteva. 2002. World Lexicon of Grammaticalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1075/fol.10.1.12fis [ Links ]

Hoeksema, J. and D.J. Napoli. 2019. Degree resultatives as second-order constructions. Journal of Germanic Languages 31(3): 225-297. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1470542719000084 [ Links ]

KieBling, R. 2013. Verbal serialisation in Taa (Southern Khoisan). In A. Witzlack-Makarevich and M. Ernszt (eds.) Khoisan Languages and Linguistics: Proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium, July 6--10, 2008, Riezlern/Kleinwalsertal. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe. pp. 33-60. [ Links ]

Kilian-Hatz, C. 2002. The grammatical evolution of posture verbs in Kxoe. In J. Newman (ed.) The Linguistics of Sitting, Standing and Lying. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. pp. 315-331. https://doi.org/10.1075/tsl.51.13kil [ Links ]

Kilian-Hatz, C. 2006. Serial verb constructions in Khwe (Central Khoisan). In A. Aikhenvald and R.M.W. Dixon (eds.) Serial Verb Constructions: A Crosslinguistic Typology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 108-123. https://doi.org/10.1515/lingty-2017-0008 [ Links ]

Köhler, O. 1981. La langue Kxoe. In J. Perrot (ed.) Les langues dans le monde ancien et moderne, première partie: les langues de l'afrique subsaharienne. Paris: Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique. pp. 483-555. [ Links ]

König, C. 2010a. Verb serialization in !Xun. In M. Brenzinger and C. König (eds.) Khoisan Languages and Linguistics: The Riezlern Symposium. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe. pp. 152-185. [ Links ]

König, C. 2010b. Are there ditransitive verbs in !Xun? In A.L. Malchukov, M. Haspelmath and B. Comrie (eds.) Studies in Ditransitive Constructions: A Comparative Handbook. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. pp 74-114. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110220377.74 [ Links ]

König, C. and B. Heine. 2001. The !Xun of Ekoka: A Demographic and Linguistic Report. Cologne: University of Cologne. [ Links ]

Kuteva, Tania A. 1999. On 'sit', 'stand', 'lie' auxiliation. Linguistics 37: 191-213. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling.37.2.191 [ Links ]

Nakagawa, H. 2016. The aspect system in Glui: with special reference to postural features. Natural History of Communication among the Central Kalahari San. The Research Committee for African Area Studies: Kyoto University. http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/207691

Newman, J. 1996. Give. A Cognitive Linguistic Study. Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter. [ Links ]

Pawley, A. 2009. On the origins of serial verb constructions in Kalam. In T. Givón and M. Shibatani (eds.) Syntactic Complexity. Diachrony, Acquisition, Neuro-cognition, Evolution. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. pp. 119-144. https://doi.org/10.1075/tsl.85.05ont [ Links ]

Pickrell, J. K., N. Patterson, C. Barbieri, et al. 2012. The genetic prehistory of southern Africa. Nature Communications 3, Article 1143. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2140 [ Links ]

Pratchett, L.J. 2018. Dialectal Diversity in Southeastern Ju (Kx'a) and a Documentation of Groot Laagte \Kx 'aoW 'ae. PhD dissertation, Humboldt Universitat Berlin. [ Links ]

Pratchett, L.J. 2021. An areal and typological appraisal of gender in Ju. STUF - Language Typology and Universals 74(2): 279-302. https://doi.org/10.1515/stuf-2021-1033 [ Links ]

Pratchett, L.J. 2022. When verbs 'stand (and) go' together: the pseudo-consecutive construction in Jul'hoan and !Xun. Paper presented at the International Symposium for Khoisan languages and linguistics, Riezlern, 18-20 July.

Rapold, C.J. 2014. Areal and inherited aspects of compound verbs in Khoekhoe. In T. Güldemann and A.-M. Fehn (eds.) Beyond 'Khoisan': Historical Relations in the Kalahari Basin. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. pp. 153-177. https://doi.org/10.1075/cilt.330.06rap [ Links ]

Ross, Daniel. 2021. Pseudocoordination, Serial Verb Constructions and Multi-Verb Predicates: The Relationship between Form and Structure. PhD dissertation, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5546425 [ Links ]

Ross, Daniel. 2022. Pseudocoordination and serial verb constructions as multi-verb predicates. In Gusti, G., V. N. di Caro and D. Ross (eds) Pseudo-Coordination and Multiple Agreement Constructions. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. pp. 315-336. https://doi.org/10.1075/la.274.14ros [ Links ]

Sands, B. 2010. Juu subgroups based on phonological patterns. In M. Brenzinger and C. König (eds.) Khoisan Language and Linguistics: The Riezlern Symposium 2003: Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe. pp. 85-114.

Traugott, E.C. and E. König. 1991. The semantics-pragmatics of grammaticalization revisited. In E.C. Traugott and B. Heine (eds) Approaches to Grammaticalization, Volume I: Theoretical and Methodological Issues. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Vossen, R. 2010. The verbal linker in Central Khoisan (Khoe) in the context of deverbal derivation. Journal of Asian and African Studies 80: 47-60. [ Links ]

Winberg, M. 2010. The Storyteller: Folktales from the Kalahari Desert and Okavango River in Botswana. Cape Town: University of Cape. [ Links ]

1 In some sources the entire language complex is referred to as !Xun. Heine & König (2015:18) suggest that the term "Ju" is inappropriate as it appears only in a subset of varieties. On the contrary, jù 'person' [zuu~3uu~d3uu] is found across the language complex (for !Xun see e.g., Heikkinen 1987:19, 31, 35, 49; König & Heine 2001:41, 45, 53; Heine & König 2008:23; for Jul'hoan see e.g., Dickens 1994:221). This paper adopts Heine & König's (2015) classification but applies the labels !Xun and Jul'hoan to the branches named "Northwestern" and "Southeastern", respectively. Dialects of a particular language are referenced geographically. E.g., the Ju variety spoken in Ekoka is a dialect of !Xun, hence Ekoka !Xun. This reference system largely overlaps with the autonyms used by speech communities, i.e., the Ekoka !Xun community identify as !Xun.

2 Examples are transcribed using the Jul 'hoan practical orthography (Dickens 1991), diverging only in the transcription of velar ejectives, which appear in the present paper as <kx'> in all contexts. For ease of reading, note that <q> represents pharyngealisation on the previous vowel, i.e., <aq> /aV; <h> when following a vowel represents breathiness. Phonotactically, Ju languages behave like all "Khoisan" languages in permitting three root templates (cf. Beach 1938): CVCV, CVV, and CVN, where N stands for nasal phonemes, <nn> /n/, <ng> /η/, or <m> /m/. An intervocalic <n> represents the nasal consonant, and a word-final <n> following a vowel represents nasalisation, i.e., <an> /ã/.

3 At least in Jul'hoan, there is considerable speaker variation and tè and ká appear interchangeable.

4 In previous research (e.g., Pratchett 2022) I refer to the construction as pseudo-consecutive construction. My thanks to Daniel Ross for suggesting the term pseudo-coordination.

5 Heine & König (2015:72) remark that posture verbs "in conjunction with the progressive marker α serve as grammaticalised progressive or continuous markers in a serial verb construction". The authors argue that the aspect marker is in the scope of V1 (ibid. : 104). This is a different analysis than the one proposed here.

6 Examples taken from the edited volume of Jul'hoan folktales (i.e., Biesele 2009) are transcribed and translated by the Jul 'hoan Transcription Group. For a brief overview, see Biesele, Pratchett, & Moon (2012).

7 König & Heine (2001:110) state that in Ekoka !Xun the conjunction tà "may also be used to connect a verb having an auxiliary function with the main verb", exemplified by the verb ||hà-g!ài 'start'. Dickens (2005:54-55) treats these verbs as complement taking verbs, with tè functioning as a complementiser.