Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus (SPiL Plus)

On-line version ISSN 2224-3380

Print version ISSN 1726-541X

SPiL plus (Online) vol.65 Stellenbosch 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.5842/65-1-971

PART 2: DYNAMIZATION OF SYNCHRONY - RELATED LANGUAGES ACROSS TIME

The earliest Serial Verb Constructions in Aramaic? Verb-verb constructions with hlk 'go' and ?th 'come' in Old Aramaic

Christian Locatell

Department of Linguistics, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. E-mail: christian.locatell@mail.huji.ac.il

ABSTRACT

This paper presents examples in which hlk 'walk, go' and ?th 'come' appear in multi-verb constructions conforming to the definition of asymmetrical serial verb constructions (SVCs). In these constructions, hlk and ?th do not appear to be used with their concrete lexical senses as verbs constituting the predicate of a separate clause. Rather, they are found in the V1 position and appear to be used as minor verbs contributing an aspectual nuance of immediacy to the major verb in the V2 position. Broader usage of these verbal forms in Old Aramaic and cognate languages is consistent with a source of such SVCs from the fusion of bi-clausal constructions.

Keywords: Serial verb constructions; Old Aramaic; grammaticalization; historical linguistics

1. Introduction1

There has been relatively little work done on serial verb constructions (SVCs) in the Aramaic of the first millennium BCE. This phenomenon has been more widely noted in later stages of Aramaic in which SVCs are much more apparent and entrenched.2 Lack of attention toward this phenomenon in earlier layers of the language means that the emergence of SVCs and traces of the source of SVCs in Aramaic have remained understudied. Notable exceptions are Andrason and Koo (2020) and Andrason (this volume). However, the focus of these studies is Biblical Aramaic. This paper examines SVCs in Old Aramaic (i.e. Aramaic texts dating from c. 612 BCE and earlier)3 and explores the implications these uses have for the development of this construction in the language. Examination of the earliest examples of SVCs in Aramaic can help clarify its degree of serialization at an earlier stage and provide clues as to the source from which the construction initially emerged.

Prototypical SVCs are defined by formal and semantic properties. These are only briefly mentioned here. For recent detailed descriptions, see Aikhenvald (2006; 2018: esp. 3-5, 2054). A canonical SVC is characterized by the following: monopredicate (i.e. on par with a monoverbal clause in the discourse), monoclausal (the verbs are not separated by intervening material and are not related by syntactic dependency), prosodically realized as a single clause,4shared TAM, polarity, and illocutionary force values, monoeventhood (the verbs describe elements of a single overall event), and share at least one argument. SVCs may also be symmetrical or asymmetrical. The SVCs discussed below are asymmetrical. That is, the minor verb in the SVC contributes some aspectual or modal nuance to the main verb. In the case of Aramaic and other Semitic languages, the minor verb is V1 and the major verb V2 (see Andrason this volume). This is also what is found in the Old Aramaic data presented below. V1 is from a semantically closed class, e.g. the motion and postural verbs listed below which are common sources of the minor verb in asymmetrical SVCs (Aikhenvald 2006:23; 2018:58).

One of the controversies in analysing SVCs has been in defining these criteria and treating constructions that approximate this idealized definition but do not perfectly conform to every aspect. In order to avoid these controversies, we focus on more canonical cases of SVCs in Old Aramaic. However, the development of SVCs in a language entails that non-canonical constructions will gradually conform to the canonical SVC profile. Additionally, as SVCs further develop in language change, they will gradually depart from the canonical SVC profile. Thus, in contrast to a ridged all-or-nothing definition of SVC category membership, a prototype approach can accommodate the facts of diachronic change. See Andrason (this volume) for a description of the SVC category in terms of its canonical and non-canonical category members within a grammaticalization framework. This approach not only allows for the necessary mechanisms of language change, but also mitigates the largely artificial difficulties that arise from assuming all-or-nothing category membership when defining SVCs.

2. The use of hlk and ?th in SVCs

It must be stated from the outset that the data from this corpus are limited. The vast majority of Aramaic language data comes from the mid-3rd century CE and on. Thus, conclusions should be provisional to the degree that they are based on limited data. We searched the corpus of Die Alt- und Reichsaramaischen Inschriften (Schwiderski 2004, 2008) for possible occurrences of SVCs.5 We limited our search to the verb types most crosslinguistically associated with SVCs. Thus, we searched the corpus of Old Aramaic for all uses of the verbs hlk6 'walk', ?zl 'come', ?th7 'go', npq 'depart', ill 'enter', qwm 'rise', and qrb 'approach'. Both in North-West Semitic (to which Aramaic belongs) as well as in broader typological perspectives, such motion and postural verbs have been seen to have the greatest propensity to develop as part of an SVC (Lord 1993:9; Aikhenvald 2006; 2018; Andrason and Koo 2020; Andrason this volume). Of these verbal forms, we only found uses of ?th 'go', and hlk 'walk, go' which appeared to approach the profile of an SVC. It is these examples which we discuss below.

2.1 hlk 'walk'

The only occurrence of hlk resembling an SVC in the corpus of Old Aramaic occurs in a mid-8th cent. BCE inscription from Deir 'Alla.8 The precise identification of the language is debated. Opinions include identifying it as part of the Aramaic branch of Northwest Semitic, a unique dialect of the Canaanite branch, or a conservative dialect approximating Northwest Semitic prior to the spilt of the Aramaic and Canaanite branches.9 Regardless of how one classifies the text as a whole, of special significance for the present study is the fact that the verbs used in the SVC here (hlk 'go, walk' and r?h 'see') are more characteristic of the Canaanite, not the Aramaic, branch of Northwest Semitic (cf. Pardee 1991:103; Rendsburg 1993:325; Gzella 2013). There are uses of hlk in texts that are uncontroversially Aramaic.10

Furthermore, this line itself has several features which characterize the Aramaic, rather than Canaanite branch: e.g. nunation (-in) for plural marking (?ilah-in, 'gods'). Thus, the analysis of hlk 'walk' in this text as a potential SVC must keep these caveats in mind, especially when considering the implications the language of this text may have for the development of SVCs within Aramaic. The text in question is the following.

In the context, a certain "seer" is troubled by visions given to him by the gods. When people approach him to ask what is wrong, he answers with the text above. The use of hlk 'walk, go' here is used as a V1 with r?h 'see' as V2. Here, both verbal forms share the same TAM, person, number, and gender values. They are both in the peal verbal stem which is the basic verbal stem (or G for Grundstamm), vis-à-vis other verbal stems with more complex argument structures, such as causative or reflexive. Both are inflected as second person masculine plural imperatives. The verbs are also completely contiguous. Note that the dots in the text are word dividers. The mono-eventhood of these two verbs is also indicated by several features in the text. The imperative in the first clause of the utterance, "Sit down", shows here that hlk in the subsequent clause cannot be taken in its normal lexical sense of a verb of motion. It would hardly make sense to tell the audience to sit only to immediately tell them to 'go' in the next utterance. The fact that the speaker is recounting to the audience the deeds of the gods, as it were, in their minds eye, also lends a more abstract interpretation to hlk. Bekins (2020:175) also notes the function of hlk here as a departure from its typical usage and describes it as acting like an interjection, as in "Come on!" or "Come now!". He also refers to parallels with Biblical Hebrew hlk in similar constructions.13

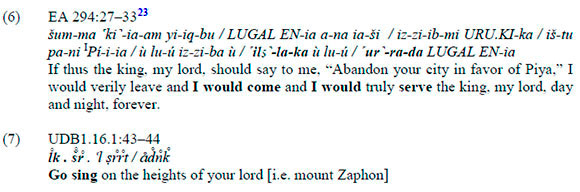

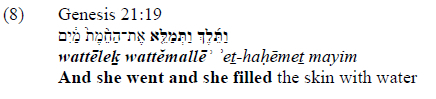

In terms of the nuance added to V2 by hlk as V1, such verbs of motion tend to grammaticalize one of several nuances, including progressive, continuative, and habitual meanings.14 Such nuances are indeed found with hlk as V1 in asymmetrical SVCs (see examples in fn. 18). However, these nuances do not seem to fit this context. More compatible is the proposal regarding cognates of hlk: aláku in Amarna Canaanite (Andrason 2019b) and hlk in Ugaritic (Andrason and Vita 2020). These cognates occur in several examples approaching the prototypical profile of SVCs where the cognate of hlk appears as a minor verb in V1 position. In these cases, Andrason (2019b) and Andrason and Vita (2020) read these in terms of an aspectual nuance of emphasis, urgency, and intensity added to the major verb V2. Consider example (2). Similar observations have been made concerning Ugaritic hlk. Consider example (3).

In these examples, 'go' in V1 position suggests an aspectual nuance of urgency added to the V2 which provides the lexical meaning of the command.

Skorodumova (2015:174) makes the same argument for the use of hlk in such constructions in Biblical Hebrew to mark intensity.18 In discussing the use of hlk in an SVC to provide an aspectual nuance of intensity (הגדשה) to the V2, she mentions Exodus 19:24 as an example of the prosodic integration of hlk to the V2, characteristic of verb serialization. This can be seen in the fact that the normal long vowel /ë/ is reduced to /ε/, and hlk is prosodically linked to V2 with a maqef (dash) as a single accentual unit.

This usage of hlk appears compatible with interpretating it as adding to the V2 an aspectual nuance of urgency.20

An aspectual nuance of urgency or immediacy is also plausible when considering potential bi-eventhood, coordinating precursors to such uses. When considering coordinating constructions where hlk precedes another verb, V2 can only start when V1 is accomplished, that is, when the subject goes (hlk, V1) to preform V2. Verbs with the root letters hk, taken by some to be from the root hlk,21 are also found in Old Aramaic in such coordinating constructions. Consider example (5) from the Sefire Inscriptions.

In such coordinating constructions with bi-eventhood, built into the sequence of events is the fact that the completion of V1 begins the execution of V2. That is, the commencement of the speaker's activity of 'placating' coincides with the completion of hlk. The speaker must first come, and then he can do the placating. Such a built-in conceptualization may have been what allowed hlk to be reanalysed as a V1 in an asymmetrical SVC in order to add the nuance of urgency to the V2, especially with imperatives. The speaker can say "go X" in order to communicate the urgency or immediacy with which X is to be performed. Thus, such coordinating constructions may also be consistent with the development of an asymmetrical SVC with hlk as the minor verb in the V1 position.

The same observation can be made concerning cognate data. Consider the following examples from Amarna Canaanite (6), Ugaritic (7), and Biblical Hebrew (8).

As suggested regarding example (5), such coordinating constructions with bi-eventhood have built into themselves the conceptualization that the completion of V1 begins the execution of V2. In fact, lk (2fs.IMPV of hlk) in example (7) could be read as asyndetically coordinate to the following verb in a bi-event construction, or with mono-eventhood as V1 in an asymmetrical SVC providing an aspectual nuance of immediacy and urgency to V2 'sing'. This is perhaps the very sort of bridging context that allowed such uses to be reanalysed as mono-clausal asymmetrical SVCs. Cases like (1) can perhaps be read as switch contexts taking this one step further, where hlk no longer has the concrete meaning of 'go, walk' and the erstwhile bi-eventhood is reduced to mono-eventhood. The meaning of hlk as V1 is then schematized to expressing the urgency or immediacy with which V2 is to be performed.

There is also evidence for the use of hlk in SVCs in subsequent layers of the language.24 In the following stage of Imperial Aramaic, there is indication that this indeed was or came to be a more productive V1 in asymmetrical SVCs in Aramaic, and not simply confined to second person imperatives. This would avoid the problem, pointed out by Aikhenvald (2018:124125), of categorizing SVCs as verb-verb combinations when they are restricted to contexts when neither verb is inflected for person or tense. 25 Take for example the following text in (9) from the first quarter of the 5th cent. BCE. In this example, there is no intervening material between V1 (hlk 'go') and V2 (?gs 'grind'). Both are marked for the same TAM, person, and number values. They are both peal (basic verbal stem) imperfect forms with future temporal reference marked as first person singular (which does not distinguish between masculine and feminine). In this case as well, there appears to be a nuance of immediacy added by hlk to the V2. That is, what is being said is that as soon as "he" comes out, "I will go grind." However, the surrounding text has missing sections and it is difficult to know the full context of this statement.

Taken together, this data appears to be recoverable evidence, scarce though it may be, both within Old Aramaic, as well as in Northwest Semitic cognates, that the root hlk (including verbal forms with the root letters hk) 'walk, go' was used in constructions consistent with the emergence of an SVC via the fusion of bi-clausal constructions, as illustrated in examples (5)-

(8). That is, in a bi-clausal construction consisting of V1+V2, the lexical meaning of V1 is abstracted and reanalysed as an aspectual modification of V2 in a mono-clausal construction.27

On this reading of the data, hlk 'walk, go' then came to be used as a V1 to add the aspectual nuance of urgency to a V2, as seen in (1). If the language of the Dier 'Alla text in (1) is in fact an Aramaic dialect, or even a conservative Northwest Semitic dialect preserving an idiom prior to the divergence of Aramaic and Canaanite, then this token may constitute the earliest trace of hlk in an SVC in Aramaic (or its immediate ancestor), which can also be seen in subsequent periods, as in example (9).

2.2 ?th 'come'

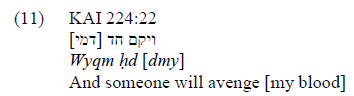

The verb ?th 'come' is also found as a V1 in some constructions which appear to fit the characteristics of an SVC. This is found in the third of the Sefire Inscriptions. These are a group of treaty texts which date to the mid-8th cent. BCE.28 In the section where ?th appears in what looks like an SVC, the treaty is listing the duties of a vassal king in the case that his suzerain (the great king) or one of his heirs is assassinated. In this event, the vassal is called on to "come avenge" the blood of the suzerain, his son, or his grandson.

In each of the four occurrences in this text, both verbal forms share the same TAM, person, number, and gender values. The first includes the coordinator 1 wow, while the following three do not.30 In terms of TAM values, the verbal forms are once again in the basic verbal stem peal with imperfective conjugation and future temporal reference. However, these imperfective forms are used here with deontic modality (cf. Li 2009:112-117) as is common in stipulation sections of treaty texts like this (Van Rooy 1989). However, it should be noted that formally speaking, these are not imperative forms. This would appear to indicate usage of such constructions is not confined to imperatives, strictly speaking.

Regarding the aspectual nuance added by ?th, the sense of emphasis, urgency, and intensity again seems to plausibly fit here. Once again, this development as a V1 in an SVC could have arisen via a similar extension as that suggested above for hlk discussed in examples (5)-(8). That is, cases of ?th such as those in (10) could be read as coordinate to the following verb in a bi-event construction, or with mono-eventhood as V1 in an asymmetrical SVC providing an aspectual nuance of immediacy and urgency to V2 ' avenge'. Later in the text, this same activity of avenging the blood of the suzerain is again mentioned in an indicative, rather than prescriptive context.

Here, "avenge" appears without ?th "come" in an indicative context, even though here too, the one who would avenge the blood of the suzerain would still need to first "come" physically to another location in order to do so. This could be taken as an indication that the verbal idea of "[come] avenge" is conceived of as a single event, but the use of ?th "come" with "avenge" adds an aspectual nuance of urgency in an imperative utterance.

Additional evidence of the use of ?th as a V1 in an asymmetrical SVC comes from the earliest Aramaic letter on papyrus, called the Adon Letter/Papyrus. It was written near the end of the 7th century BCE (ca. 605 BCE) around the transition from Old Aramaic to Imperial (or Official) Aramaic (Kaufman 1992).31 In the letter, king Adon (of Ekron) writes to the Pharoah (Neco II) in Egypt asking for military assistance to defend against Babylonian invasion (by Nebuchadnezzar II).32 Similarly to Sefire inscription discussed above, this letter appeals to a treaty relationship between king Adon (as vassal) and Pharoah Neco (as suzerain) as the basis for the call for help. In the letter, king Adon follows his request for help with the statement that he had kept his treaty obligations with the implication that he was therefore entitled to the protection the treaty ostensibly offered from the suzerain. Within this request for help is found the following text.

Here, ?th 'come' appears to function as V1 in an asymmetrical SVC with the verb mt? 'arrive' as V2. There is no conjunction waw connecting the two verbs. Both share the same TAM, person, gender, and number values. The verbal forms are in the basic peal stem in the perfect conjugation with past temporal reference and third person masculine plural marking. Significantly, these are not imperative forms and do not have deontic modality, as with the apparent SVC use of ?th in (11). Thus, there is notable variety in TAM marking and verbal morphology with these potential SVCs, indicating a degree of entrenchment and diffusion beyond imperative constructions.

In terms of the aspectual nuance added by ?th as V1, as with the above examples, a nuance of intensity fits quite well here, especially in the context of the letter. Recall that this letter was urgently sent with a dire request for military aid. This was made all the more urgent by the fact that the location to which the troops of Babylon had just arrived was Aphek, a strategic point from which a significant military force could control several major intersecting routes in the region. It is hard to see how taking ?th mt? 'come arrive' as two, independent coordinated verbs would be anything more than tautologous. However, a better interpretation may be available in light of the proposal offered above regarding the source of ?th as a V1 in an asymmetrical SVC. Restating the proposal briefly, ?th as the first verb in canonically coordinate constructions marked the beginning point of the following verb (see the discussion of (5)-(9) above). This conceptualization of marking the beginning of the following verb inherent in such constructions could then lead to bridging contexts where it could be extended in imperative utterances to add a nuance of urgency or intensity to the following verb. In essence it would be saying to ' come x' as in start it now, with urgency, intensity, and immediacy. Likewise, this example in (12) appears to show another possible extension in non-imperative contexts where the intensity nuance added by ?th to the V2 in the past is that the execution of V2 had just happened. Just as a motion verb could appear in coordinate and asyndetic constructions to mark the execution of the following verb in future contexts (e.g. (5) and (9)), or mark the urgency and immediacy with which to enact the execution of V2 in imperative/volitive contexts (e.g. (1)-(4) and (10)), here it marks the immediacy of the execution of the following verb in a past context adding the nuance that it had just happened, i.e. immediate anteriority.34 Indeed, it would have been immediately upon hearing this that king Adon sent to Pharoah Neco II to bring urgent help. As it turns out, this request was urgent indeed. Egypt was not able to stave off this Babylonian invasion and Ekron was destroyed in 604 BCE, just after this letter would have been sent (COS 3.54). Thus, this verb-verb construction may be better understood as an SVC, rather than as a coordinate construction, which is how it is typically rendered in translation (e.g. "has come and reached").35 If correct, this would better illuminate the tenor of the language and one of the syntactic means used to express the dire circumstances communicated by the letter.

3. Conclusion

In Old Aramaic and on into Imperial Aramaic, there are uses of hlk and ?th as V1 in verb-verb sequences which appear to fit the profile of asymmetrical SVCs. In these constructions, the aspectual nuance contributed by the V1 in both cases seems to be that of urgency or immediacy.

That is, these forms communicated the urgency to immediately execute a command of the V2, e.g. "come see" in (1) and "come avenge" in (10). They are also used to communicate the immediacy regarding a future or past action of the V2, i.e. as soon as "he" comes out, "I will go grind" in (9) and "they have just now reached Aphek" in (12). Formally, the verb-verb constructions discussed here show significant variation, including imperative forms with deontic modality, imperfective forms and perfective forms with future and past temporal reference (respectively) and root modality. The verbal forms are also found with first, second, and third person, and singular and plural inflection. The verbs appearing as V2 appear to belong to an open class and include r?h "see", nqm "avenge", and mt? "arrive". The usage of hlk and ?th in overtly coordinating constructions was seen to provide possible bridging contexts where their more concrete sense as verbs of motion could be reinterpreted as contributing a sense of urgency or immediacy to the following verb. Thus, the data from Old Aramaic is consistent with the identification of SVCs in the earliest Aramaic texts in the 8th century BCE. With only two roots appearing in constructions conforming to the profile of SVCs, this analysis suggests a very low level of serialization in Old Aramaic. In light of the broader usage of these verbs in Old Aramaic and cognate languages, the source of these SVCs from the fusion of erstwhile bi-clausal constructions is also plausible.

References

Aikhenvald, A. 2006. Serial verb constructions in typological perspective. In A. Aikhenvald and R. M. W. Dixon (eds.) Serial Verb Constructions: A Cross-linguistic Typology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1-68. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198791263.003.0010 [ Links ]

Aikhenvald, A. 2018. Serial Verbs. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Andrason, A. 2019a. Categorial gradience and fuzziness - The QWM gram (serial verb construction) in Biblical Hebrew. In G. Kotzé, C. Locatell and J. Messarra (eds.) The Ancient Text and Modern Reader. Leiden: Brill. pp. 100-126. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004402911006 [ Links ]

Andrason, A. 2019b. A serial verb construction with the verb alâku "Go" in Canaano-Akkadian. Antiguo Oriente 17: 11-38. [ Links ]

Andrason, A. and B. Koo. 2020. Verbal serialization in Biblical Aramaic. Altorientalische Forschungen 47(1): 3-33. https://doi.org/10.1515/aofo-2020-0001 [ Links ]

Andrason A. and J. P. Vita. 2020. Serial verb constructions in Ugaritic. Aula Orientalis 38(1): 5-33. [ Links ]

Arayathinal, T. 1957-1959. Aramaic Grammar, I-II. Mannanam: Saint Joseph's Press. [ Links ]

Bar-Asher Siegal, E. 2016. Introduction to the Grammar of Jewish-Babylonian Aramaic. Lehrbücher orientalischer Sprachen III/3. 2nd edition. Ugarit-Verlag: Munster. [ Links ]

Bekins, P. 2020. Inscriptions from the World of the Bible: A Reader and Introduction to Old Northwest Semitic. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Academic. [ Links ]

Bembry, J.A. 2015. The Aramaic root 'to go'-HWK or HLK? In J. M. Hutton and A.D. Rubin (eds.) Epigraphy, Philology, and the Hebrew Bible: Methodological Perspectives on Philological and Comparative Study of the Hebrew Bible in Honor of Jo Ann Hackett, e. Atlanta: SBL Press. pp. 87-96. [ Links ]

Blau, J. 2007. Reflections on the linguistic status of two ancient Semitic languages with cultural ties to the Bible. Lesonénu 69(3/4): 215-220. (In Hebrew) [ Links ]

Cook, E. M. 2015. Dictionary of Qumran Aramaic. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. [ Links ]

Cook, E. M. 2008. A Glossary of Targum Onkelos According to Alexander Sperber's Edition. Leiden: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/ei.9789004149786.i-314 [ Links ]

COS = Hallo, William W., and K. Lawson Younger (eds.). 1997-2003. Context of Scripture. 3 vols. Leiden: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/eib2211-436x [ Links ]

Creason, S. 2008. Aramaic. In R.G. Woodward (ed.) The Ancient Languages of Syria-Palestine and Arabia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 108-144. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511486890.009 [ Links ]

Degen, R. 1969. Altaramaische Grammatik Der Inschriften Des 10.-8. Jh.v. Chr. Abhandlungen Für Die Kunde Des Morgenlandes, 38, 3. Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner. [ Links ]

Fassberg, S. E. 2015. Translation technique in Targum Onqelos: The rendering of Hebrew הל׳׳ך In J. M. Hutton and A. D. Rubin (eds.) Epigraphy, Philology, and the Hebrew Bible: Methodological Perspectives on Philological and Comparative Study of the Hebrew Bible in Honor of Jo Ann Hackett. Atlanta: SBL Press. pp. 97-108. [ Links ]

Fitzmyer, J. A. 1965. The Aramaic letter of king Adon to the Egyptian pharaoh. Biblica 46: 41-55. [ Links ]

Fitzmyer, J. A. 1995. The Aramaic Inscriptions of Sefire. Rome: Pontificio Istituto Biblico. [ Links ]

Garr, W. R. 2004 [1985]. Dialect Geography of Syria Palestine 1000-586 BCE. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. https://doi.org/10.2307/415522 [ Links ]

GKC = Gesenius, Friedrich Wilhelm. 1910. Gesenius' Hebrew Grammar. Edited by E. Kautzsch and Sir Arthur Ernest Cowley. 2nd English ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [ Links ]

Gzella, H. 2013. Deir 'Alla. In G. Khan (ed.) Encyclopedia of Hebrew Language and Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.1163/2212-4241ehllehllcom00000333

Hackett, J. A. 1980. The Balaam Text from Deir 'Alla. Harvard Semitic Monographs, 31. Chico, CA: Scholars Press. [ Links ]

HALOT = Koehler, Ludwig, Walter Baumgartner, M. E. J. Richardson, and Johann Jakob Stamm. 1994-2000. The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament. Leiden: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/2352-3433halotall [ Links ]

Heine, B. and T. Kuteva. 2002. World Lexicon of Grammaticalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Hoftijzer, J. and G. van der Kooij (eds). 1991. The Balaam Text of Deir 'Alla Reconsidered. Proceedings of the International Symposium held at Leiden 21-24 August 1989. Leiden: Brill. [ Links ]

Hoftijzer, J. and G. van der Kooij. 1976. Aramaic Texts from Deir Alla. Leiden: Brill. [ Links ]

Huehnergard, J. 1991. Remarks on the classification of the Northwest Semitic languages. In J. Hoftijzer and G. van der Kooij (eds) The Balaam Text of Deir 'AllaReconsidered. Proceedings of the International Symposium held at Leiden 21-24 August 1989. Leiden: Brill. pp. 282-293. [ Links ]

JM = Joüon, P. and T. Muraoka. 2006. A Grammar of Biblical Hebrew. Roma: Pontificio Istituto Biblico. [ Links ]

KAI = H. Donner and W. Röllig. 1971-1976. Kananaische und Aramaische Inschriften. 3 vols. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz [ Links ]

Kaufman, S. A. 1992. Languages: Aramaic. In D. N. Freedman (ed.) The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary. New York: Doubleday. [ Links ]

Krotkoff, G. 1982. A Neo-Aramaic Dialect of Kurdistan: Texts, Grammar and Vocabulary. New Haven: Yale University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/603568 [ Links ]

Lambdin, T. O. 1971. Introduction to Biblical Hebrew. New York: Scribner. [ Links ]

Li, T. 2009. The Verbal System of the Aramaic of Daniel: An Explanation in the Context of Grammaticalization. Leiden: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004175143.i-200 [ Links ]

Lord, C. 1993. Historical Change in Serial Verb Constructions. TSL 26. Amsterdam: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.2307/416196 [ Links ]

Macúch, R. 1965. Handbook of Classical and Modern Mandaic. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. [ Links ]

McCarter. 1991. In J. Hoftijzer and G. van der Kooij (eds) The Balaam Text of Deir 'Alla Reconsidered. Proceedings of the International Symposium held at Leiden 21-24 August 1989. Leiden: Brill. pp. 87-99.

Müller, H. P. 1991. Die Sprache der Texte von Tell Deir 'Alla im Kontext der nordwestsemitischen Sprachen-mit einigen Erwàgungen zum Zusammenhang der schwachen Verbklassen. Zeitschrift für Althebraistik 4(1): 1-31. [ Links ]

Nöldeke, T. 1875. Mandaische Grammatik. Halle: Buchhandlung des Waisenhauses. [ Links ]

Nöldeke, T. 1904. Compendious Syriac Grammar. Translated by James A. Crichton. London: Williams and Norgate. [ Links ]

Pardee, D. 1991. The linguistic classification of the Deir 'Alla text written on plaster. In J. Hoftijzer and G. van der Kooij (eds) The Balaam Text of Deir 'Alla Reconsidered. Proceedings of the International Symposium held at Leiden 21-24 August 1989. Leiden: Brill. pp. 100-106. [ Links ]

Pat-El, N. and A. Wilson-Wright. 2015. Deir 'Alla as a Canaanite dialect: A vindication of Hackett. In J.M. Hutton and A.D. Rubin Epigraphy, Philology, and the Hebrew Bible: Methodological Perspectives on Philological and Comparative Study of the Hebrew Bible in Honor of Jo Ann Hackett. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. pp. 13-24. [ Links ]

Porten, B. 1981. The identity of King Adon. Biblical Archaeologist 44: 36-52. https://doi.org/10.2307/3209735 [ Links ]

Rainey, A. 2015. The El-Amarna Correspondence: A New Edition of the Cuneiform Letters from the Site of El-Amarna based on Collations of all Extant Tablets. 2 vols. Edited by William Schniedewind. Leiden: Brill. [ Links ]

Rendsburg, G. 1993. The dialect of the Deir 'Alla inscription. Bibliotheca Orientalis 50(3/4): 309-329. [ Links ]

Robker, J. M. 2019. Balaam in Text and Tradition. FAT 131. Tubingen: Mohr Siebeck. https://doi.org/10.1628/978-3-16-156356-0 [ Links ]

Schniedewind. 2005. Accordance North West Semitic Inscriptions Module. Oak Tree Software.

Schwiderski, D. 2004. Die Alt- und Reichsaramaischen Inschriften. Band 2: Texte und Bibliographie. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110875706 [ Links ]

Schwiderski, D.. 2008. Die Alt- und Reichsaramaischen Inschriften. Band 1: Konkordanz. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Skorodumova, P. 2015. Paths of grammaticalization in Hebrew [דרכי הגרמטיקליזציה בעברית] Revue Européenne Des Études Hébraïques 17: 169-180. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24721905 [ Links ]

Shitrit, T. 2020. The Language of Jewish Babylonian Aramaic Stories: Linguistic Means of Text Structure in the Aramaic of Talmudic Stories. PhD Dissertation, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. (In Hebrew) [ Links ]

TAD = Porten, Bezalel and Ada Yardeni. 1986, 1989, 1993, 1999. Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt: Newly Copied, Edited, and Translated into Hebrew and English. Vols. 1-4. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. [ Links ]

Van Rooy, H. F. 1989. The Structure of the Aramaic Treaties of Sefire. Journal of Semitics 1: 133-139. [ Links ]

Vilsker, L.H. 1981. Manuel d'araméen samaritain (French ed. by J. Margain). Paris: Centre national de la recherche scientifique. [ Links ]

UDB = Cunchillos, J-L., J.-P. Vita and J.-Á. Zamora (eds.). 2003. Ugaritic Data Bank. Madrid: Labratorio de Hermeneumática. https://doi.org/10.31826/9781463209384 [ Links ]

1 I would like to thank Prof. Steven Fassberg and the anonymous reviewer for helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper. All errors, of course, remain my own responsibility. I would also like to thank the Golda Meir Fellowship at Hebrew University for funding this research.

2 As noted by Andrason and Koo (2020:8): "Bi-verbal constructions have been dealt with in studies on Mandaic (Nöldeke 1875:441-445; Macúch 1965:449-451), classical Syriac (Nöldeke 1904:272-276; Arayathinal 19571959:356-357), Samaritan Aramaic (Vilsker 1981:84), Jewish-Babylonian Aramaic (Bar-Asher Siegal 2016:269-272), and several neo-Aramaic dialects (e.g., Krotkoff 1982)." See also Shitrit (2020:115-170) on serial verb constructions in Jewish Babylonian Aramaic, with extensive discussion of the roots ?zl 'come', qwm 'rise', and ?th 'go' with respect to their textual and communicative function in story-telling.

3 See Kaufman (1992).

4 This is not recoverable for Old Aramaic.

5 However, specific examples are labelled according to their number given in KAI. Examples from Imperial Aramaic are also listed according to their number in TAD.

6 This paper will also include with the discussion of hlk uses of a verb with the root letters hk, e.g. 3ms prefix conjugation yhk 'he will come'. These verbs have been taken by many as derived from hlk. This position will be taken as a point of departure for this paper. Cases will be referred to with the root hlk throughout. However, this view has been debated. Others see such verbs as deriving from a separate root hwk. The basic argument for taking verbs like yhk 'he will come' as deriving from hlk is that the root hlk with the meaning 'go, walk' is widely attested in Northwest Semitic, whereas a root hwk is only known in Ethiopic meaning "to agitate". Additionally, proponents of the view that yhk 'he will come' derives from hlk explain the deletion of the /l/ as parallel to the 3ms prefix formysq 'he will arise' from the root slq 'go up'. For a recent treatment of this debate and a defence of the view that hlk is the underlying root, see Bembry (2015). But see Fassberg (2015:99 fn. 12). The complementary distribution in later Aramaic of hk forms in the G-stem (the basic stem in Semitic), and hlk in the D-stem may be taken as suggesting that these are different roots. However, even if these are properly seen as different roots, this would not necessarily detract from their use in structures resembling SVCs and the implications this has for the emergence of the construction in Aramaic.

7 Note that the final letter of this root shows (the common) variation between /h/ and /y/ in the third root letter. For simplicity, this root will be represented as ?th rather than ?ty throughout.

8 For background on this text, see COS 2.27; Hackett (1980:1-8); Gzella (2013); and contributions in Hoftijzer and Van der Kooij (1991).

9 In the editio princeps, Hoftijzer and van der Kooij (1976) identified the language of the text as Aramaic. On the place of this language relative to Canaanite and Aramaic, placing it closer to Aramaic, see Garr (2004 [1985], esp. 205-235). For the view that places the language of this text closer to Canaanite, see Hackett (1980:109-125) and more recently Pat-El and Wilson-Wright (2015). Rendsburg (1993) offers the more precise identification of the language of the Deir 'Alla text as closest to Israelian Hebrew, and even more specifically, "Gileadite". McCarter (1991), instead of identifying the language as either Aramaic or Canaanite, prefers to describe it geographically with elements of influence from surrounding dialects. Pardee (1991) defends the traditional classification as Aramaic (cf. Robker 2019:276-279, 302). Blau (2007) is more hesitant to classify it as Aramaic and also entertains the idea that it represents a separate branch (like Huehnergard below). Müller (1991) argues that it is a remnant of Northwest Semitic before the split of the Aramaic and Canaanite branches, preserved up to the point in time of the inscription because of the geographic isolation of the area. Huehnergard (1991) argues from a diachronic perspective that the language represents a separate branch of Northwest Semitic (though in some ways his proposal overlaps with Müller's).

10 Huehnergard (1991:292) lists likü as a conservative form of common Northwest Semitic shared by the Aramaic and Canaanite branches. Also note that hlk occurs in the G-stem (the basic stem in Semitic) in the Deir 'Alla text, an Aramaic text from Asoka (see Schwiderski 2004:41 for references), Canaanite (Hebrew, Phoenician, Moabite), Ugaritic, and Akkadian. However, in later Aramaic, hlk occurs in the D-stem, which is typically used with a transitive meaning but is used with hlk intransitively. For occurrences of hlk in Old and Imperial Aramaic, see Schwiderski (2008:232). It also occurs in the Biblical Aramaic of Daniel (3:25; 4:26, 34). For its use in the Middle Aramaic of Qumran and Targum Onqelos, see Cook (2014:64) and Cook (2008:69), respectively. However, even if one counts Deir 'Alla as Aramaic, this would be the only use of the verb r?h in an Old or Imperial Aramaic text. However, it has been argued that the reconstructed nominal root *rw "appearance", based on rêwêh in Biblical Aramaic, rëwa? in Dead Sea Scrolls Aramaic, and rêyw in Jewish Palestinian Aramaic, is from the root r?h (see HALOT, 1979).

11 Note that consonantal texts without vowels or a vocalization tradition are left unvocalized.

12 This translation of the text follows standard renderings which can be found in several different sources.

13 See GKC §110.h which mentions examples along the lines of (4) below.

14 Aikhenvald (2006:23; 2018:58). As such, this would be an aspectual nuance added by the minor verb of the SVC. For other types of modification seen with asymmetrical SCVs, see Aikhenvald (2018:56-73).

15 Rainey (2015: 556-557).

16 Note that while Rainey uses this conjunction in his translation, there is not actually any such conjunction in the text.

17 Note that the dots between words in the transcription represent word division markers. The circles above letters indicate probable readings of damaged text.

18 In Modern Hebrew, she discusses the use of hlk to mark an aspect of "gradation" (גרדטיב) in constructions like כמות המלח במזון הולכת וגדלה kamut ha-melax bemazon holexet ve-gedelah 'the amount of salt in the food is increasing (lit. going and enlarging)'. Such a use can also be found in Biblical Hebrew, e.g. Jonah 1:11- הַיָּם֖וסְעֵֹרֽ hayyàm höwlëk wësö ër ".. .the sea stormed more and more" (lit. 'the sea went and stormed'). In another example, the nuance provided by hlk appears to be some sort of emphasis: והוא פשוט הלך ושיקד ve-hu pasut halax ve-siqed 'and he just went and lied'. Skorodumova (2015:177-178).

19 Biblical texts are vocalized after the Tiberian tradition.

20 Compare the GO > HORTATIVE developmental path included in Heine and Kuteva (2002:159-160). For additional parallel examples from Biblical Hebrew, see Lambdin (1971:239); GKC §120.g-h; JM §177e-f. Also see Chrzanowski (2011:253-255) who interprets such cases of hlk as an auxiliary communicating gradual progression or development. However, he does not mention this case in Exodus 19:24, presumably because he does not see it as a case of what he calls "verbal hendiadys."

21 See fn. 6 above.

22 Fitzmyer (1995:136-137), labelled Sf III 6. The verb in question אהך ?hk "I will come" is parsed in Schniedewind (2005) as having the root הוך. However, Fitzmyer (1995:222) and Schwiderski (2008:229) parse this as having the root הלך. See further fn. 6.

23 Rainey (2015:1136-1137). See the discussion in (Andrason 2019b:26-29).

24 Note that these examples contain forms with the root letters hk which has been understood as being derived from hlk. See the discussion in fn. 6 above.

25 Aikhenvald has in mind constructions such as come play, or go eat, as used in American English. However, even with such restrictions, as Aikhenvald (2018:125) points out, these still share important traits with SVCs, leading some to classify them as 'quasi-serial verb constructions'.

26 Compare the later use in Syriac of constructions like □□ □□□ □□□ qwm hlk t? "Rise go come", noted in Nöldeke (1904:247). Nöldeke renders this sentence more idiomatically as "up! go and come"".

27 Aikhenvald (2018:196-201) gives crosslinguistic examples of clause fusion as the source of asymmetrical SVCs. On the origin of SVCs in Northwest Semitic in general via "clause fusion", see Andrason (this volume).

28 See Fitzmyer (1995:17-20) for a basic introduction to the background of the text.

29 The forward slash indicates a line break.

30 Fitzmyer (1995:153) suggests that the asyndetic pairs may be a mistake of the engraver. Degen (1969:127) lists this as a case of asyndeton.

31 Of course, any precise date dividing Old Aramaic from Imperial Aramaic is arbitrary, since language change is gradual. Indeed, Old Aramaic itself is not completely homogenous. The main impetus for drawing a distinction here is due to the adoption of Aramaic as the lingua franca around this time by the Babylonian Empire. Some reckonings draw the dividing line between Old and Imperial Aramaic at the rounder date of 600 BCE (e.g. Creason 2008:109).

32 See Fitzmyer (1965) and Porten (1981).

33 This text is also presented in TAD A1.1 4. Compare TAD D7 20:2 for another possible case of ?th in an SVC.

34 It is tempting to see here similarity with the function of ?th in SVCs in Jewish Babylonian Aramaic stories from the Talmud discussed by Shitrit (2020:156) who describes their function as sometimes appearing to present the event from the internal perspective of a character as the deictic center. Perhaps similarly in this letter, the fresh arrival of the Babylonains appears to be presented from the perspective of King Adon which is highlighted as the deictic center.

35 See Fitzmyer (1965:44); Porten and Yardeni (1986:6); COS 3.54. Interestingly, in their Modern Hebrew rendering, Porten and Yardeni (1986:6) translate this verb-verb sequence asyndetically as באו הגיעו "came arrived".