Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus (SPiL Plus)

On-line version ISSN 2224-3380

Print version ISSN 1726-541X

SPiL plus (Online) vol.64 Stellenbosch 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.5842/64-1-853

ARTICLES

Interstitial small stories in Sandton, Gauteng, South Africa

William Kelleher

Unit for Academic Literacy, University of Pretoria, and LIDILE, Rennes 2 Email: william.kelleher@univ-rennes2.fr

ABSTRACT

Interstices are those residual, left-over, spaces associated with movement across and between urban forms. Interstices in the business district of Sandton, Gauteng, South Africa, represent the insurgence of the lower levels in the vertical push of the high-rise offices, luxury hotels and retail spaces of the district. In interstitial spaces encounters and interactions are often fleeting and contingent. There is a discontinuity of social space. Links between people are spread out over the grid of the city, disassembled and reassembled as people leave their homes, move through different transport nodes to different destinations in the district and there, in turn, continue and discontinue their trajectory. Interstitial stories capture a reticular activity that binds people together through movement and space. In terms of narrative research, interstitial stories, a type of 'small' story, offer particularities that concern the intersection of the spatiality and temporality of the real and diagetic worlds, linguistic representational means and social consequentiality. The aim of this article is to explore interstitial stories, as an instantiation of small stories research and as a local storytelling practice, through three extracts that represent three different configurations of space and time: superposed spatialities, temporal and spatial identity, and movement in telling trajectory. In analysing these stories, this article hopes to shed further light on the role that narrative plays in our daily lives and interactions, bringing out local conditions and linguistic repertoires in the global South. Interstices emerge as challenging, cooperative and familiar, and, in contradistinction to what their name could imply, a strong resource for identity construction.

Keywords: interstitiality; narrative; interaction; small stories; spatio-temporality; trajectory

1. Introduction

This article aims to explore interstitial stories and will look at the overlap they occasion between the spatiality and temporality of the storytelling world and the diagetic story, or tale, world, their linguistic representational means and their social consequentiality. The article attempts to shed further light on the role that narrative plays in our daily lives and interactions, and in so doing examine local conditions and linguistic repertoires in the global South. Interstitial stories are an example of 'small' stories (Bamberg and Georgakopoulou 2008; De Fina and Georgakoulou 2008; Georgakopoulou 2007) that have been successfully studied in South Africa (Oostendorp and Jones 2015). The stories that form the data are from a case study of a site, Sandton, in the metropolitan area of Johannesburg, Gauteng, South Africa. All the stories collected in the case study were strongly associated with space, since the methodology privileged trajectories to or through the site, and mapped participant stories using global positioning system (GPS) technology. However, some participants collected stories on the move in interstitial spaces such as public transport hubs, service alleys and parking bays which are often inaccessible to urban ethnographies since they require a rare familiarity with a site that is linked to the pragmatics of employment and routine. Two participants, called Elliot and Dikeledi, contributed stories that are particularly revelatory of such spaces and represent a unique opportunity for their study.

The small stories that these two participants collected in interstitial spaces involve very low narrativity, reduced or absent verbal orientation and the partial or total superposition onto the story world of the spatio-temporal coordinates of the situation of interaction. In terms of the storytelling roles identified by Koven (2002) which is to say author (a person telling the story), interlocutor (a person who is situated interactionally) and character (a person who is a figure in the story), these stories confound roles, since the tellers are positioned interactionally in the space of the storytelling world, which is also that of the storied world. The representational means of telling, the repertoires used, are also spatially determined (Blommaert, Collins, and Slembrouck 2005). The study of Elliot and Dikeledi's stories requires being open to ways of doing things with technical objects such as language and narrative structure that perhaps are unusual or less privileged in other contexts and contributes to a sociolinguistics about Africa and of Africa (Ebongue and Hurst 2017), mobilising a post-colonial perspective that takes into account, "popular - often oral and communally shared -forms" (Goebel and Schabio 2013:2) not in order to question narratology per se, but to report on and advance local approaches to narrative genre from the global South. The focus of this article is on the mechanics of these stories and on exploring the local conditions of their production.

The sections that follow introduce, firstly, the background to this research and the rationale for studying interstitial stories, and secondly, some aspects of narrative theory and of 'small stories' research. The role that spatiality and temporality can play in story construction is discussed. Following this, participant data and methodology are presented. Three story extracts are then analysed for their spatio-temporality, their linguistic representational means and their social consequentiality. The three extracts represent three different configurations of space and time: superposition of spatial frame, temporal identity of story space and storytelling space, and movement in space and time that parallels emplotment. They allow some conclusions to be drawn for storytelling in the interstices and the kinds of narrative and identity work these stories produce.

2. Background

The nexus of space and narrative interaction is a productive research axis for understanding the sites and societal configurations of South Africa. Stories told whilst walking through a site, for instance, can allow an investigation of their, "mobile and praxeological constitution" (Stroud and Jegels 2014:185). Similarly, in Johannesburg, the Yeoville Studio initiative (Benit-Gbaffou 2011) involved a photovoice workshop that concentrated on the affective and biographic ties to the district. The objects and architecture that constitute lived space, or place, are powerful aspects of narrative, since place "is discursively constructed through human intention, at the same time as these ontological objects come to constrain the agencies and subjectivities of their human users/interactants" (Bock and Stroud 2018:14). Semiosis, narrative, discourse and interaction intertwine since "interactions are entextualized in narrative, becoming explicitly part of the cluster of the material and lived reality of a place that impacts or imprints itself upon bodies" (Bock and Stroud 2018:15). This article attempts to contribute to studies such as these through a continued exploration of narrative interaction and through a focus on a particular kind of space associated with movement across and between urban forms. Such movement is often associated with the 'liminar and with a questioning of institutional boundaries that leads to a corresponding suspension or negotiation of social norm and ritual (Goffman 1959, 1972, 1986, Turner 1969). It should be clear, however that liminality is not necessarily spatialised. Liminality arises from the symbolic resources that one brings to an interaction. In terms of spatiality, therefore, the term interstice (Tonnelat 2003, 2008) is perhaps preferable.

In Sandton, the research site, interstices represent, in many ways, the insurgence of the lower levels in the vertical push of the high-rise offices, luxury hotels and retail spaces of the district. Interstices have characteristic temporalities and spatialities. Encounters are fleeting, people are on the move as they commute, obtain products and deliver merchandise, etc. There is a corresponding disjuncture of social space. Links between people are spread out over the grid of the city, disassembled and reassembled as people leave their home neighbourhoods, move through different transport nodes to different destinations in the district and there, in turn, continue and discontinue their trajectory. The data collected from participants in these interstices capture a reticular activity that binds people together through movement and space. Narrative, in this sense, as space- and time-bound, cuts across communities of practice but often not across the enormous social declivities that characterise South African cities. Sandton, despite its huge mall, some of the highest incomes in Africa, and its aesthetics of superfluity (see Mbembe 2008) is served by a network of informal and semi-formal urban and peri-urban areas (Soweto, Alexandra and Cosmo City) where unemployment is high and salaries can be low, outsourced and precarious. Housing, transport and access to health and educational services in these areas suffer from the legacies of Apartheid, compounded by the particular conditions of the governing African National Congress (ANC) approaches to urbanisation that are documented, for instance, in Harrison, Masson and Sinwell (2014).

Many of the people who live in these areas come to work in Sandton on foot or by shared taxi. They arrive in a district almost devoid of pavements, where most office block facades are blank and security monitored. The taxi rank, that sees many thousands of commuters per day, is stark grey concrete, underground, dimly lit. It contains food stalls and tuck shops in a situation of managed informality. In many ways it is a symbol of inequality. Above it is the prestige Gautrain train station with its panoply of security guards, chronometered services, electronic access and guided links to private taxis and hotels such as the Radisson with which it is associated. The taxi rank is off to one side, hidden in its subterranean location. Sandton is marked by these contradictions and would seem to be antinomic to the sense of place as described by De Certeau (1984) or Massey (1995). For these authors place represents a nexus of memory, practice, investment and socialisation that is also produced discursively. Space, as opposed to place, is "abstract geometries (distance, direction, size, shape, volume) detached from material form and cultural interpretation" (Gieryn 2000:465). However, in narrative, spatial coordinates such as height, width, topographic markers, vectors, diameters, displacements and trajectories are the means by which a teller renders a scene for her or his hearer, and by which that hearer interprets the storied world that is being evoked. This is the sense in which Georgakopoulou states that "I view every space as place: as an experienced, lived, and practised social arena by social actors" (Georgakopoulou 2015:2).

If space is place, then, to a study of place, the interstitial can contribute its movement, its residual status and the fleetingness of encounters. Interstices are an instance of the 'other' spaces (Foucault 2004) from which the world can be understood. Narratives from the interstice contribute to work on 'small stories' (Bamberg and Georgakopoulou 2008, De Fina and Georgakoulou 2008, Georgakopoulou 2007). They similarly contribute to better understanding processes of orientation in story construction (Baynham 2009, De Fina 2003, Labov and Waletzky 1997 [1967]) and to better discerning the relationality of spaces and their combination of time, and place (Vigouroux 2009, Blommaert and De Fina 2017).

3. Understanding interstitial small stories:temporality, spatiality, linguistic means and consequentiality

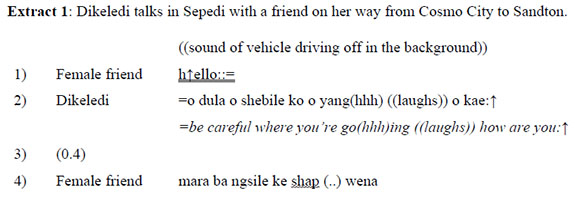

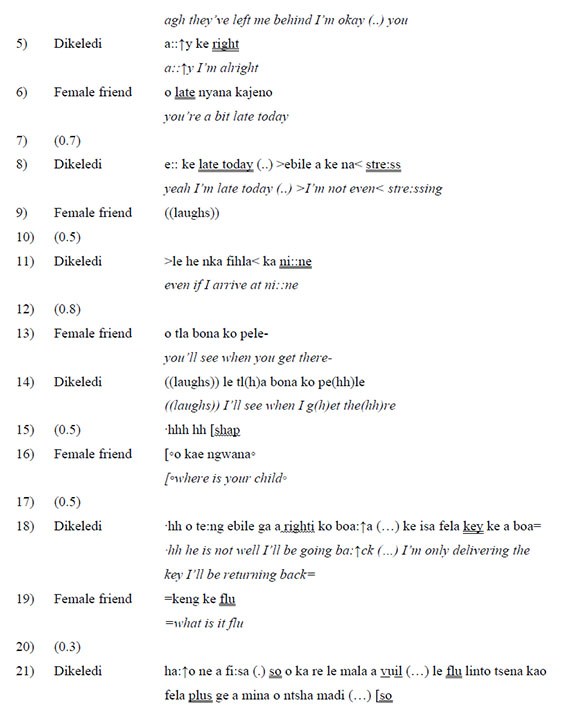

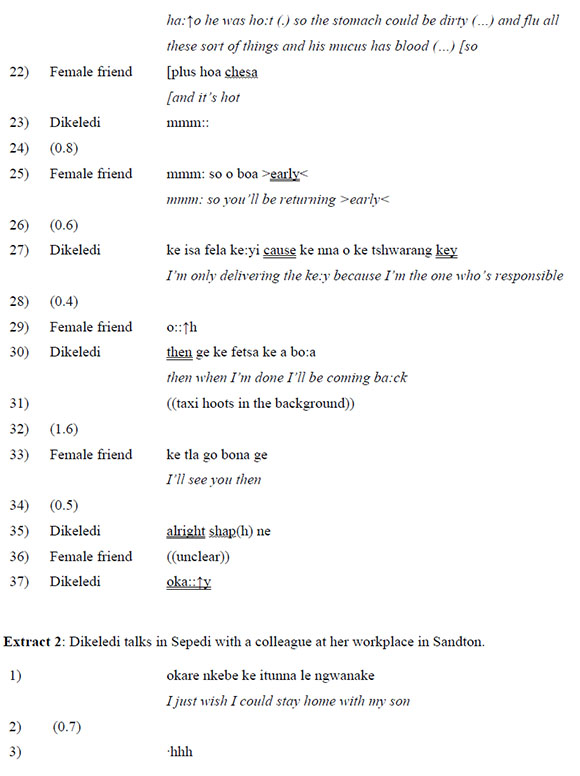

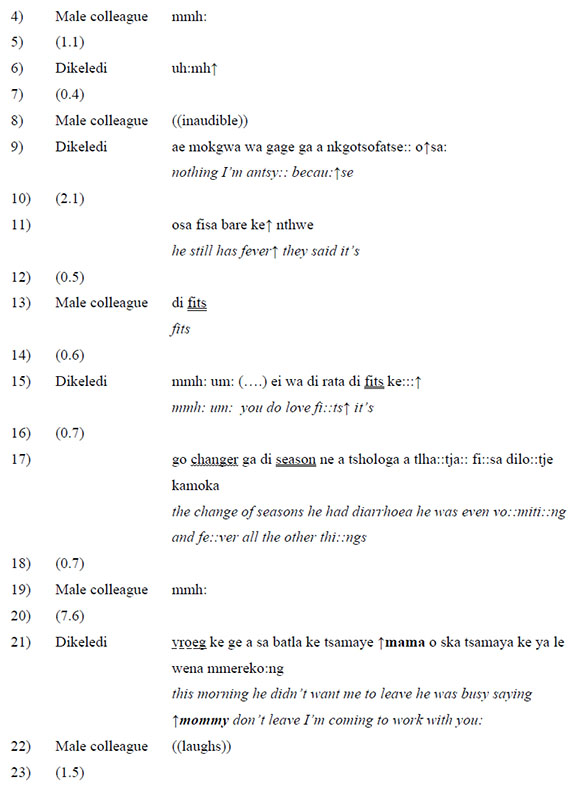

Small stories from the interstices function with situated and interlocutor-oriented deixis, overlapping of diagetic story world and storytelling world and complex temporal structures. To illustrate this, Extract 1 below gives a transcript of a recording made by Dikeledi on her way to work in the interstitial space of a taxi stop, whilst Extract 2, recorded two days later with her colleague, gives the same subject matter, her sick son, this time in her workspace. As in all the transcripts given here that are of 'Gauteng' varieties of Setswana, Sepedi and isiZulu (Lafon 2005) very informal and contact forms are underlined with a wavy line, English derived forms are double underlined and Afrikaans derived forms are underlined with dashes. Translations are given in italics below each turn. Transcriptions indicate pauses (...), vowel elongation (:::), emphasis (bolding and capitalisation), changes in intonation (fj), changes in speed (><) and breathiness (-hhh). They follow the schedule given in De Fina and Georgakopoulou (2015:7).

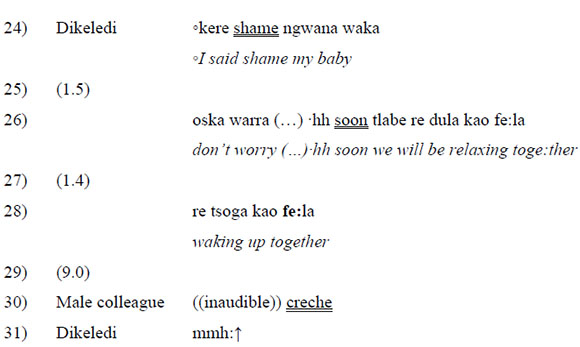

Both the small story of Extract 1 and that of Extract 2 are co-constructed and best understood in terms of social practice, and the consequentiality of their occasioning. There are significant differences however between Extract 1, the interstitial story, and Extract 2, the story told in the workplace. In Extract 1 Dikeledi literally bumps into her interlocutor. Much of the story is framed in the future and with a progressive aspect. The spatial coordinates of Dikeledi's trajectory are also included in the story structure. The going back home that is a repetitive motif of the story refers to taking a taxi in the opposite direction to that in which she is currently travelling.

In Extract 2 whilst the orientative elements are indeed in the present and are descriptive of Dikeledi and her son's emotional and physical state, the crux of the story, the scene that Dikeledi experienced when she left her son at home, is in the past tense and is conveyed using direct speech. Linguistic representational means such as direct speech assist in portraying affective states. Dikeledi emphasises how she and her child addressed each other (\mommy don't leave I'm coming to work with you, and shame my baby). The story world, Dikeledi's home, is thus clearly distinguished from her workplace. The consequentiality of the two stories, their meaning for the participants, is similarly very different. Whilst they both share news, the first extract concerns, one could suggest, an in-process negotiation of the roles of mother and employee. The second is perhaps more aptly understood as addressing and accounting for workplace dynamics.

Within small stories research, interstitial stories can further contribute to understanding processes of spatio-temporal progression, representational means and consequentiality. This can be appreciated through a discussion of Table 1, that provides a synthetic overview of different levels of narrative analysis.

Level 1 concerns narratology. 1 a) is what Ricoeur refers to as 'mythos' (Ricoeur 1983:55), which can be understood as the "configuration of incidence in the story" (Greimas, Ricoeur, Perron and Collins 1989). Stories are held to necessarily provide an ordered sequence of events which, in Genette's terms, is called the 'récit' (Genette 1966). This sequence combines with 1 b) a descriptive, evaluative, element that is discursive and in close rapport with the words spoken by a figure in the story world or the narrator of this same story world. Events are temporally ordered. Description is spatially ordered. Events are sequentially presented whilst the characters and objects which give them form occupy, and move through, space. These two criteria, and their combination, lead to genre in Bakhtinian terms, or 'chronotope' (see Todorov 1984). Within linguistics, Level 1 receives treatment in Labov and Waletzky's work, where the correspondence of syntax and event, which they refer to as temporal juncture, is held to be decisive of narrativity (Labov and Waletzky 1997 [1967]:25). Labov and Waletzky turn their attention to oral narratives (Level 2) that are told face-to-face (Level 3). The uptake and meaning of a story depend on Level 4, and include questions of evaluation and ratification by its hearers.

The Level 4 preoccupation with the framing of interaction is continued in Sacks' work on storytelling and the mechanics of conversational organisation. In Sacks' example, "the baby cried, the mother picked it up" (Sacks 1974:226), Sacks notes that "the baby cried" announces trouble, and in so doing serves as a 'ticket' by which the storyteller can obtain telling rights. The idea of occasioning, the Sacksian 'ticket', has become a highly productive line of analysis (see for instance the discussion of epistemic status in Wortham 2000). Generally, Sacks', and Labov's, treatment of the importance of stories for ordinary doing being, that implies Level 1 and Level 4 considerations, has been continued from a variety of perspectives. Prince (1988), who incorporates questions of interactionally achieved meaning into narratological reflection, is a case in point, as is the work on everyday life by Ochs and Capps (2001). Small stories approaches to narrative are very much informed by these directions in research.

Small stories emphasise socially situated practice (De Fina and Georgakopoulou 2008, Georgakopoulou 2007) and revisit, from this perspective, the grounds on which one decides to recognise a story as a story. Social consequentiality asks the question, "What insights would the analysis be missing if a strip of activity were not treated as a story for the participants' social lives?" (Georgakopoulou 2007:39). A consideration of social consequentiality is both a Level 4 and a Level 5 analytic consideration, since it deals with agentive interaction and wider social processes and discourses. It leads, in turn, to a significant recasting of Level 1 narratological questions and a reinterpretation of the treatment of spatiality and temporality. Temporally, for instance, stories can be acknowledged concerning events that are in the process of unfolding (Georgakopoulou 2008:601) or projections, in which possible future scenarios are jointly pieced together by participants (Bamberg and Georgakopoulou 2008). Spatially, the orientative elements of a story regain emphasis and are no longer considered a 'backdrop' aspect of storytelling (Baynham 2003).

In a story told at a temporal or spatial remove from the events it recounts, the orientative elements serve "to orient the listener in respect to person, place, time and behavioural situation." (Labov and Watezky 1997 [1967]:27). This is to say that, in this view, spatial and temporal references are one part of the way in which the story world is defined and clarified for the listener. As Schiffrin terms it, "'who, why, and when join where to preface what happened" (Schiffrin 2009:422). This definition would seem to give a fairly static interpretation of time and space, as embedded in the story world, and not necessarily contiguous with, superposed on, or identical to the situation of interaction. Orientation, and orientative processes, in small stories, are held to be complex, dynamic and evolutive. Firstly, mediated interaction (Level 3) has brought attention to the ways in which participants to a story can be disposed spatially as well as temporally and, as a result, be more or less available for face-to-face interaction (Georgakopoulou 2017). Secondly, antagonistic and precarious processes of social insertion can lead to 'dis'orientation in narratives (De Fina 2003), in which tellers are unsure, hesitant or unable to give orientation information. Thirdly, orientation, and the introduction of spatial references, can be part of very significant identity work in the space of the story world and in the space of the telling (Baynham 2009, De Fina 2009b). This identity work can involve the representational means used to tell the story (Level 2) since small stories are hybrid genres, going beyond the dichotomy of written/oral and reworking narrative analysis in the context of our mobile, networked lives.

In the case of interstitial small stories, they involve, as noted in the introduction, reduced or absent verbal orientation and superposition of the spatial and temporal coordinates of the situation of interaction and of the story world. Spatiality and temporality, in these stories, can be understood as a partial or total identity between Levels 1 and 4 of Table 1 with resultant implications both for participant understandings, macro social processes and discourses (Level 5) and for representational means such as language, gesture and voice (Level 2). Temporally, since these stories are responding to the relationship that the teller is maintaining with surrounding space and movement, verbal aspects can be non-finite and verb groups can express present and futurity. Different time scales are operative and are mobilised by participants. These time scales can concern the immediate situation of talk but also longer periods that touch on both personal biographic and socio-historic processes (Baynham 2009). Spatially, orientative elements in the story (Level 1) can be replaced by deixis, movements of the body, and the perception that each participant has of their surrounds (Levels 2 and 3).

Interstitial small stories, finally, are subject to spatialised linguistic regimes (Blommaert, Collins and Slembrouck 2005). In the same way that the landscape of South African cities is haunted by the spatial inequalities of apartheid (Bock and Stroud 2018), the linguistic dispensation that opposed exogenous and indigenous language varieties (Makalela 2004) continues to exist. In a monolingual English regime, stories told in African languages can suffer from the institutional fragilization noted in Krog, Mpolweni and Ratele (2009). It is in this respect that informal registers, commonly referred to as "kasi-taals" connote more fluid processes of identity construction (Brookes 2014, Makalela 2014). Finally, both Stein (2008:44-74) and Kunene-Nicolas, Guidetti and Colletta (2017) note the increased importance of gesture in story telling in isiZulu narratives and, one can suggest by extrapolation, in other South African language varieties generally. This would seem to point to a wider, more encompassing interlocutor haptic space that, in turn, has consequences for the manner in which interstitial stories are occasioned and enacted.

4. Participant data and research methods

The participant data analysed here come from a South African National Research Foundation funded doctoral project, which aimed to provide an interactional narrative linguistic ethnography of Sandton. The ethnography concerned Sandton's politics of inclusion and exclusion, its circulation of discourses and the everyday meaning making of its executives, workers, visitors and tourists. The participants were invited to self-record their interactions during the course of a day or two, although they could record for longer time-periods if they wished1. Dikeledi in fact participated for several days, as did Elliot. Alongside the audio recorder, participants carried a GPS logger so that their physical location could be read against the interactions they recorded. The audio recorded interactions were completed with interviews and, where possible, by a joint consideration of the transcripts of their small stories. Locations indicated by GPS logs and pertinent to storytelling were subsequently visited by the researcher and photographed. The audio files were edited using Audacity (https://www.audacityteam.org/) and interstitial stories separated out from what were long recordings of several hours. Transcription and translation of these extracts is credited in acknowledgments. Any mistake or inaccuracy is due to the author. Data concerning African languages corresponds to a wish for inclusivity in research.

Interstitial stories can be compared with other data collected from each participant. Elliot's stories as told in office spaces with co-workers, for instance, are usually longer and more detailed. One of his stories concerning a sick colleague takes over 81 turns at talk. For Dikeledi, a story she tells to a work colleague, about drugs in a nightclub, extends over 84 turns. Similar shifts in story telling can be observed with other participants in the study, such as informal sellers, police personnel, students and taxi drivers. An analogue process occurs with respect to register. Both Elliot and Dikeledi have semi-professional positions in companies that operate in the heart of Sandton. They both employ a formal register in a standard South African English. Nevertheless, these transcriptions show the employ of different varieties and different registers. Extract 3 was recorded by Elliot in a service alley behind the Virgin Active gym. Extract 4 was recorded by Elliot in a pedestrian area near to the Mandela Square entrance to the Sandton City Mall. Extract 1, above, was recorded by Dikeledi while travelling by taxi from Cosmo City to Sandton.

5. Analysis and findings

In order to explore the characteristics and functioning of interstitial small stories, this section will discuss three extracts that represent different configurations of space and time. Extract 3 gives an example of superposed spatialities, Extract 4 is an instance of temporal and spatial identity, whilst the last part of this discussion returns to Dikeledi's Extract 1 in order to better understand the movement in telling trajectory that this story supposes. Each story will be analysed in terms, firstly, of spatio-temporal organisation and functioning (Level 1). Then the motivated choices of the participants with respect to representational linguistic means (Level 2) will be considered. Finally, for each story, the discussion concludes with its social consequentiality (Levels 4 and 5). All stories are told in oral face-to-face interaction (Level 3).

5.1 A first interstitial small story - superposed spatialities

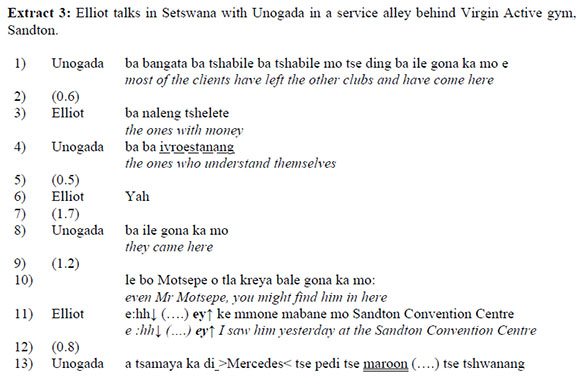

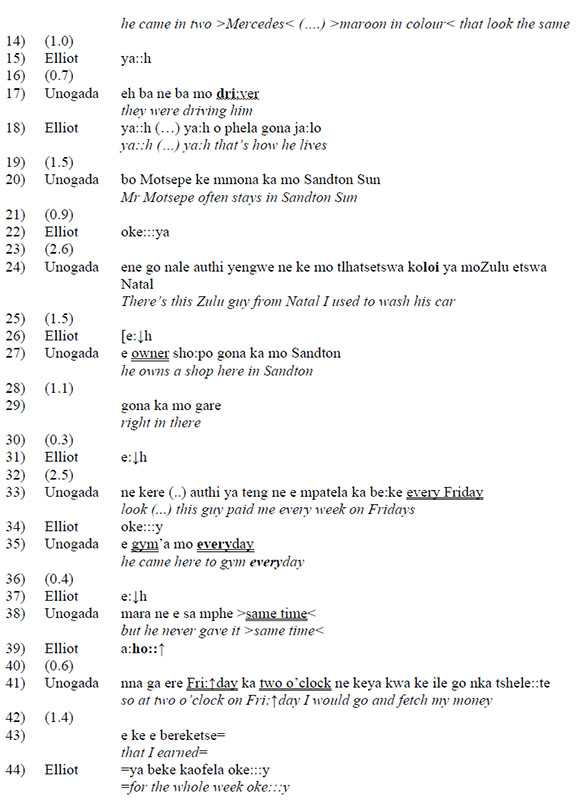

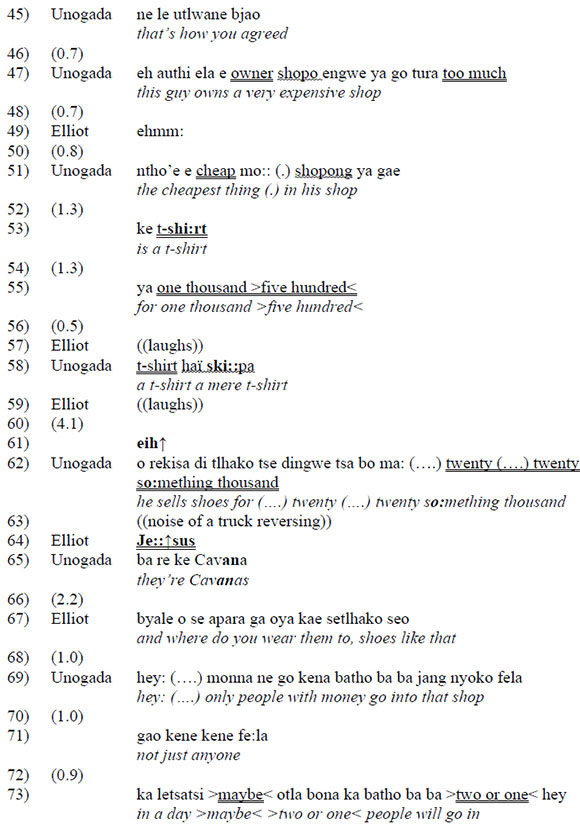

Extract 3 gives the interchange between Elliot, a personal assistant for an overseas investment bank, and a car guard who, following the custom in the Gauteng, has been called 'Unogada'. In South Africa, car guards are mainly unemployed men who look after parked cars, and sometimes wash them, in exchange for a few Rands (the South African currency). In this case Elliot is waiting in a service alley behind a Virgin Active Gym and chatting to Unogada to pass the time. The extract given here tells about two people: Mr Motsepe, a South African mining magnate who is also known for his philanthropy and closeness to the governing ANC, and a shop owner in the Sandton City Mall who used to pay Unogada weekly.

The discussion of this extract will look, firstly, at the characteristics of this story, its spatiality, temporality, and linguistic means, before turning to questions of social consequentiality.

The narrativity of this extract is low. In the first story about Mr Motsepe that occupies turns 10 to 22, only turns 11 and 13 represent a temporal series of events. In the second story about the shop owner, from turns 24 to the end of the extract in line 73, there are only four narrative clauses in the Labovian sense of a clause that is bound sequentially. These occur in lines 24, 33, 38 and 41. There is however fairly sustained work done on characterisation. Mr Motsepe is given depth and continuity through habitual actions that are reported. Unogada knows both where he stays and his general lifestyle. In a similar fashion, Unogada knew the shop owner and maintained a relationship with him that spanned several weeks. In both cases the story contains evaluation of these characters. In the case of Mr Motsepe, the story illustrates Unogada's detailed knowledge of the place and functioning of Sandton. The places mentioned in the story are the gym, the service alley, a shop in the Sandton City Mall, and the Sandton Sun, a luxury hotel near to the Sandton convention centre.

Deixis allows for reduced orientative elements. Unogada can point directly to places and accompany his telling with gesture and orientations of the body. This is more appreciable should one report the story. Turn 35, he came here to gym everyday would become, he went to the Virgin Active gym everyday. The 'here that is so immediately understandable in real-time interlocutionary speech needs to be replaced with an onomastic reference. Orientation therefore consists only of brief indicators of place (here) and of time (everyday). What is at issue is the origo for operations of deixis. The teller, Unogada, is the reference point for the movements and events that he recounts. Another example of this process can be appreciated in line 10 where Unogada introduces Mr Motsepe: even Mr Motsepe, you might find him in here. The shop in Sandton is contextualised in similar terms in line 27, he owns a shop here in Sandton.

Ryan (2009) differentiates between: a) spatial frames, which are the sites and corresponding scenes, b) setting, which is the socio-historico-geographic environment, c) story space, which is relevant to the series of events, d) story world, which is the coherent world as completed by imagination and experience, and e) narrative universe, which means the set of actual and alternate story worlds as evoked by the narrative. In the interstitial stories collected at Sandton, the spatial frame would be the urban interstice, the setting would be the general environment of fast capitalism and consumption in the global South that is manifested in places like Sandton. The story space would be the district conceived as a sum of the reticular stories that are told about it and that take place in different locations with different scenes. The story world would be the geographical and historical sense of coherence with which participants situate Sandton. In Unogada's stories, Sandton is the story space, relevant to the events of the story. It also provides the socio-historico-geographic setting. There is an ambivalence, however, in these stories between an acknowledgment of poverty and marginalisation and of the enumeration of conspicuous wealth.

The movement from the interstitial spatial frame of the service alley behind the gym, to the gym itself and its clientele, to the spatial frame of, firstly, the Sandton Sun hotel where Mr Motsepe stays, to, finally, the Sandton City Mall where Unogada's client has his shop, indexes conspicuous wealth. Elliot and Unogada are mentioning spaces that are highly exclusive. As an indication, at the Sandton Sun one can pay ZAR3500 (Approx. USD 230) for a room. The shop, similarly, sells shoes that cost ZAR20,000 (Approx. USD 1,392.00) per pair. This astronomical figure is taken up by Elliot's Je::↑susof line 64. This is a sum of money, that, if one takes Unogada's monthly income as somewhere in the region of ZAR2000 (Approx. USD 139.00) would represent more than a year's earnings. The superposition of the story world is therefore total in terms of setting, but only partial in terms of spatial frame. The spatial frames are marking out coordinates in a story world that is then filled in by the participants' imagination and experience. This occurs similarly in each story. In the story about Mr Motsepe, line 10 introduces Mr Motsepe as being regularly seen at the Virgin Active but then the spatial frame moves to the Sandton Convention Centre that is next to the Sandton Sun and several blocks away from where Unogada and Elliot are talking. In the story about the shop owner, line 24 introduces Unogada's relationship with him in the service alley but then the spatial frame moves to the shop in Sandton City Mall, not far from the Convention Centre.

This movement in spatial frame is accompanied by a temporal movement. In the first story, line 10 (where the situation of interaction corresponds to the narrative spatial frame) the story is recounted in the present. Once the spatial frame moves away to the Convention Centre the events are recounted in the past. Line 20 is again in the present, but the implication is that Unogada often works around the Convention Centre, and that this spatial frame is therefore also associated with his person and his point of view (the Sacksian 'ticket' referred to above). Unogada's field of vision overlaps with evaluative work. A similar variation between past and present can be observed in the story about the shop owner. The story that concerns Unogada and the interstitial space is in the past whilst the shift in spatial frame and the evaluative elements of the story are in the present. Although this is therefore, on one level, a fairly typical move between narrative clause in the past, and evaluation in the present, the overlap with Unogada's own spatial frame is irregular. The story whose spatial frame overlaps with the Virgin Active is longer, more detailed and contains more evaluative and biographical work.

Setting and corresponding spatial frames influence linguistic means. As the transcriptions of Extract 3 shows, telling this story involves contact forms and transferred elements from other languages that constitute the fluid identity construction to which Brookes (2014) and Makalela (2014) refer. The employ of fluid language varieties raises the question of social consequentiality. The interstitial space of the alley becomes a space of multilingualism (Blommaert, Collins and Slembrouck 2005). Following Tufi (2017) and Hurst-Harosh (2019) one could consider it to be a space of challenge to the linguistic regime of Sandton. Firstly, this service alley is in many ways a non-space that exists outside of the Sandton district. In Foucaultian terms (Foucault 2004) it is a heterotopia in that it provides a mirror image of the district. Compared to the mall and the use the mall makes of space and time in the promotion of conspicuous consumption, this service alley is a zone of transit. It has clearly marked prohibitions to parking or lingering, and, in contradistinction, direct and explicit instructions to load and complete service-related functions quickly. The alley is video surveyed and monitored and reserved for service personnel such as drivers, security guards and waste removal.

The spatial frames of the Virgin Active, Sandton Sun and Sandton City Mall reference places of wealth and fame. Unogada's stories are indexing difference linguistically, spatially and temporally.

The interaction between a personal assistant to a private bank (Elliot) who is in a service alley in his silver Toyota and a car guard (Unogada) involves a certain amount of adjustment and accommodation. The insertion of the spatiality and temporality of the interstitial allows identity work that, I would suggest, references this adjustment through characterisation, movement in spatial frame and the employ of multilingual linguistic repertoires.

5.2 A second interstitial small story - temporal and spatial identity

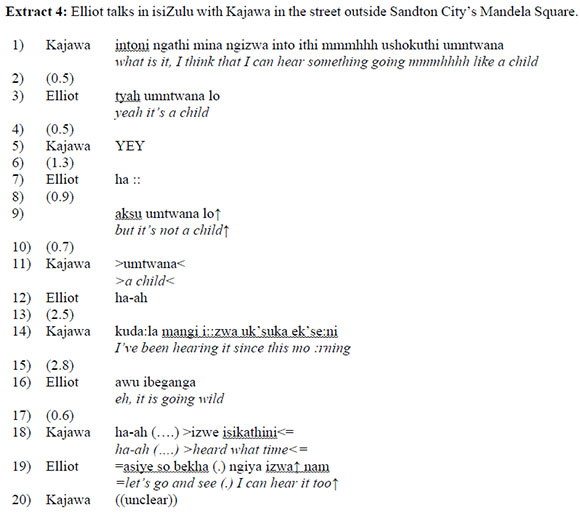

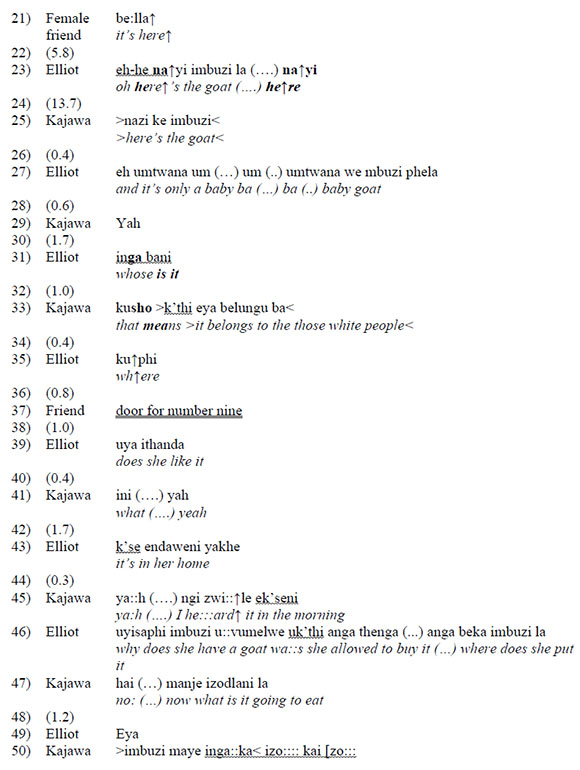

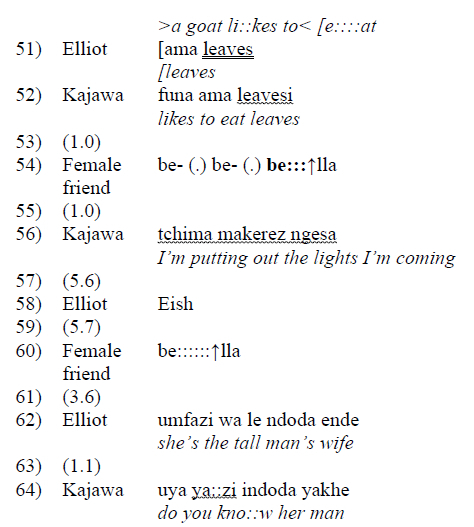

Extract 4 allows a deeper understanding of story functioning in the interstices. It is another story told by the same participant, Elliot, a personal assistant with a foreign investment bank, to Kajawa, a friend and colleague who works for the same bank representative as his gardener. The two colleagues meet outside the Nelson Mandela Square entrance to Sandton City Mall where there is a series of high-end residential units. When Elliot meets Kajawa, the latter had been listening to a series of bleats coming from one of the flats.

Extract 4 allows many of the points introduced with Extract 3 - spatio-temporality, representational linguistic means and social consequentiality - to be more closely examined. This extract presents a limiting case for treatment as a story. Only one clause is in the past tense. The sensorial and experiential stimuli are available to both participants and as a result narrative, as a situated practice, is shared rather than told. The protagonist is non-human. There are almost no descriptive or evaluative elements, and the point of telling is not immediately explicit. However, according to Georgakopoulou, one can accept that stories are, "discourse engagements that integrally connect with what gets done on particular occasions and in particular settings" and that they can concern, "very recent or still unfolding events, thus immediately reworking slices of experience and arising out of a need to share what has just happened" (Georgakopoulou 2008:601). This implies treating discourse types as coinciding with narrative dimensions such as tellership (number of participants and their roles), tellability (the social and group relevance), embedding (the closeness of the story world to participants' lives) and closed or open causal and temporal linearity (Ochs and Capps 2001). So, although this story is very close to participants' lives, and although it has a very contingent temporal and causal linearity, one notes the collaborative nature of telling roles and the social relevance for the participants.

Additionally, many characterising narrative elements are recognisable. There is clear orientation at many points in Extract 4. There is complicating action in line 23 when Elliot discovers that it is a goat and not a child making the noises. There is a coda where the implications of the story are identified and story exit is effected by a question that prompts talk about the goat's owner and her relationship status. In terms of social relevance, this extract can be best understood in terms of Prince's concept of the disnarrated (Prince 1988). As Elliot and Kajawa successively explore, verify and discard hypotheses, they are also negotiating what the story means socially, for them. The disnarrated refers to what a story is not about, the alethic, deontic, epistemic and ontologic expressions of, "nonexistence, purely imagined worlds, desired worlds, or intended worlds, unfulfilled expectations, unwarranted beliefs, failed attempts, crushed hopes, suppositions and false calculations" (Prince 1988:3). In this case the goat, that is the occasioning for the story, and that gives rise to complication and resolution is, firstly, racialised in that it is said to belong to white people (line 33), and then interpreted in domestic terms (line 46) (see Krog, Mpolweni and Ratele 2009).

Spatially, it is the story space, the space of the unfolding plot, and the real-world space of interaction that are superposed. In a certain sense, I would suggest that Elliot and Kajawa are placing themselves in the story, projecting an imaginary space on the everyday sensorial input (Caracciolo 2011). The bleats that are heard on the audio recording Elliot made, for instance, are unmistakeably those of a goat and could not seriously be taken for those of a child. Similar to Extract 3, the spatial dimension of the story can be appreciated through a restitution of its telling. Lines 19 and 23 for instance would give, in a later restitution, Kajawa and I moved closer towards the cries and, when we looked over the wall, saw a baby goat.... As with Extract 3, any retelling of this story would require a restitution of the bodily, deictic and linguistic meaning-making that is inherent in the unfolding, spatialised, narrative. Temporally, the identity between the story space and the story telling world is accompanied by an identity between the interlocutionary present and the present of the narration of events, that allows a similar identity between adverbial markers in the situation of telling and in the story world (this morning for instance, as opposed to that morning). Spatiality and temporality are dependent on each other. As Elliot and Kajawa explore space, they also set in motion the sequence of events that consists in hearing a bleat, mistaking it for a child, realising that it is a goat, and then elucidating to whom it belongs.

With respect to interlocutor role and linguistic means, this extract sheds more light on the spatiality of language practice. In discussing Extract 3 it was noted that the use of multilingualism is a 'peripheral' practice in Sandton in the sense that Blommaert, Collins and Slembrouck (2005) give this term. Extract 4 allows an examination of how interstitial stories occasion a spatially defined epistemic status (Wortham 2000) that is also relevant to Extract 3. Like Unogada, Kajawa creates and maintains an authorial role of local expert. Like Unogada he spends the whole day outdoors and is better informed of the comings and goings of the residents than Elliot. In line 1, for instance, Kajawa initiates the interpretation of the cries that leads to Elliot and himself investigating their origin. In line 14, Kajawa emphasises that he heard the cries first, before Elliot reached the site. In line 47 he raises the question of its feed. This spatially enacted epistemic status is, perhaps, what prompts Elliot to accommodate his interlocutor linguistically. Whereas in Extract 3, Elliot spoke a fluid variety of Setswana to accommodate Unogada, here, in this story, he accommodates Kajawa in isiZulu. Kajawa is from Malawi and in the recordings Elliot made, his isiZulu tends to be more informal than Elliot's who has a different socio-economic and employment status. In interviews, Elliot referred positively to his ability to accommodate different speakers in different languages and varieties and indicated that it was a frequent language strategy for him.

Following these reflections, the social consequence of this story can be better understood. It both evokes and instantiates place. In so doing, Sandton undergoes a process of inversion. Instead of being a signifier of modernity and technology, here it becomes the setting for a story about a goat that is constructed in racial, gendered and domestic terms. See also Krog, Mpolweni and Ratele (2009) for a further discussion of the meaning of goats as both symbol and occasioning for narratives. Elliot and Kajawa are enacting place by endowing architectural and urban space with meaning. Epistemically, linguistically, through the projection of the space of the story onto the space of a real-world interaction, they are accomplishing identity work.

5.3 A return to Extract 1 - movement in telling trajectory

This discussion refers to the Extract 1 that was given in section 3, the introduction to interstitial stories. One will recall that Dikeledi was on her way to work, late, to drop off the key so that she could return home and continue to look after her sick son. This extract consists of a trajectory from a point of departure to a point of arrival. The movement between these two points is also, in this case, a narrative movement from events that have occurred in the past to events that are occurring in the present and that will occur in the future. The extract was collected by Dikeledi, on her way to work at a consultancy in Sandton where she is a coordinator and facilitator. The point of departure is a house in Cosmo City, a low-rise residential zone to the Northwest of Sandton. The trajectory is by shared taxi, and the point of arrival is the taxi rank underneath the Gautrain station in Sandton.

The extract revolves around the events and places of lines 18 and 21. There are two characters, or figures, in Dikeledi's story (see Greimas, Ricoeur, Perron and Collins 1989). There is her son who is spatially removed from the situation of telling, and temporally removed from the present of enunciation. There is Dikeledi herself who is moving through space as she speaks to her friend and tells her of her son's illness. The succession of events as concerns the boy is one of illness, of being left at home and of then being cared for by his mother as soon as she returns. The succession of events as concerns Dikeledi is that of caring for her son, going to work, dropping off the key and then returning to the house. These two chains of events move with Dikeledi in the interstices of Sandton. There is a past (turn 21), a present (turns 1 - 10, 16 - 19, 21 - 24 and 27 - 29), and a future (turns 11 - 15, 18, 25, 30 and 33).

The functioning of spatiality in this story concerns motion and trajectory between spatial frames. In line 2, at the taxi stop as she leaves Cosmo City, Dikeledi warns her friend to be careful of where she is going, then, in line 4, the taxi that this friend was going to take leaves her behind. Turns 11, 13 and 14 refer to Dikeledi's arrival in Sandton. Turns 18, 25 and 30 refer to Dikeledi's return home. The participants are co-constructing this exchange just as they are in the process, themselves, of moving through space. It is the absence of a child in line 16 that prompts Dikeledi to tell her friend about his flu, but this absence is, similarly, constructed in a way that emphasises Dikeledi's motion through repetition of the verb phrase going back. However, as with Extract 3, the deixis (there lines 13 and 14) and the adverbs of time and space (back line 30) can only be understood in relation to the locus and time of enunciation.

Temporally, this extract straddles the telling of an account in the past (see De Fina 2009a), to the narrating of unfolding events in the present, to a jointly constructed projection of events in the near future. Very similarly to Extract 4, Dikeledi is talking about her acts as she accomplishes them. The transient, temporally and spatially contingent nature of the contact between Dikeledi and her friend also reflect the linguistic means that the two friends adopt in their roles as interlocutor. The exchange is generally exclamative, consisting of a hailing and interpellation of one's interlocutor. Shap a deformation of sharp, a fairly usual South African slang term that has been translated as okay, is repeated, and combines with exclamations as to the heat (chesa turn 22), lateness and stress. Use of linguistic repertoire is fairly marked in this extract with English derived language alternation creating a discourse oriented (Auer 1984) lexical field that pertains to work (late, stress, nine, key, early, cause, then ...).

The social consequentiality of the story stems from the import of the roles acknowledged and oriented to by Dikeledi and her friend. In lines 16, 19 and 22, the female friend inquires about the child, suggests a possible reason for his feeling poorly, and then mentions aggravating factors. Dikeledi herself stresses her son's illness and the fact that as soon as she has left the key at work, she will be returning home. The significance of this story concerns, firstly, therefore, I would suggest, the role of mother and caregiver and the awareness of the significance of a child's illness. However, there is also the role of coordinator at a consultancy with responsibility for a locale. In lines 18 and 27 Dikeledi rephrases the reason for her trip to work, a trip that, in leaving Cosmo City, and nearing Sandton, supposes a transfer and a separation from one role to the other. The taxi ride prevents Dikeledi from being at home, it also makes her late. It is her presence in the taxi at this uncharacteristic time of day that occasions this instance of small storying and the friend's participation. Dikeledi's responsibilities are both cited, and downplayed. In line 27, she repeats that the only reason that she is going to Sandton is to hand over the key. In line 8 she mentions that even though she is late she is not stressing. The storying of experience allows the possibility of doing evaluative work with respect to the succession of events. It also allows a sharing of experience (Georgakopoulou 2005).

6. Discussion and conclusion

The three extracts looked at above provide three examples of the spatial, temporal, linguistic and social configuration of interstitial small storying in Sandton.

Spatially, these extracts have illustrated how space can be an embedded and embedding organisational element in addition to being a resource (see Georgakopoulou 2003). In Extract 3, Unogada places himself in one spatial frame, where he has a particular role and epistemic status, before pointing to the spatial frames of the Virgin Active Gym, the Sandton Sun and the Sandton City Mall. The story, as a result, contains minimal orientative elements since situational deixis replaces information as to setting. The wealth gap between spatial frames, however, is part of the characterisation Unogada provides with respect to the figures of Motsepe and the shop owner. In Extract 4, movements through story phases from orientation to complicating action to coda correspond to physical movements through the spatial frame of the situation of telling. Finally Extract 1 emphasises the role of trajectory. The story sequence parallels the phases of Dikeledi's trip from home to work and back.

Temporally, these extracts illustrate complex framings that overlap and overlay the spatial arrangements. Extract 3, for instance, makes use of changes in present and past tense that overlap with changes in spatial frame and the distinction between story event and its description or evaluation. In Extract 4, the identity between the interlocutionary situation of the participants and that of the sequence of events allows a similar identity between aspectual and adverbial markers in the situation of telling and in the story world. In Extract 1 the story progresses from past to future in parallel with the participant's movement from home to work. The interplay of temporal elements in these extracts coincides with the work done, by the participants, with respect to characterisation and evaluation.

In terms of linguistic means and repertoire, Sandton's interstices provide insight into fluid identity construction, and can perhaps be understood as heterotopic and heteroglossic spaces of challenge to Sandton's officially promoted monolingual English regime. Whilst multilingualism in Sandton is obviously not limited to the interstitial, as Extract 2 clearly shows, interstitial spaces underline the relationship between narrative roles, such as interlocutor and character, and linguistic features and choices. Extract 1 provides an example of discourse related alternation (Auer 1984) that indexes the constraints of work. Interstitial stories would therefore seem to be displaying an orientation, by participants, to the spatiality of the speech event and linguistic repertoire can be understood in this light. A similar juxtaposition of space and discourse is hinted at by Stroud in his examination of kros (Stroud 1998) in that certain spaces authorise or disauthorise certain discoursive orientations. In this case language alternation emphasises the vertical partitioning of the district and the socio-economic differentiation between ground-level participants such as Unogada, Kajawa and to a certain extent Dikeledi and Elliot, and the executives of Sandton's high-rise corporate headquarters.

The social consequentiality of these extracts and of interstitial stories generally is more important than their ordinariness would seem, at first, to suggest. In Extract 3 Unogada accomplishes the identity work necessary to an investment of place. His stories, with their references to key stakeholders in the Sandton area, can be understood as a resistance to a marginalisation operating at personal, linguistic and socio-economic levels. In Extract 4, as the story unfolds in real time it offers the possibility of conjoint exploration of roles and their spatial performance. Elliot and Kajawa invert Sandton's more orthodox referentiality of wealth and consumption. In Extract 1 Dikeledi positions herself with respect to maternal responsibilities and the duties of work. All extracts show a sharing of information: from Unogada and Kajawa to Elliot, and from Dikeledi to her acquaintances and colleagues. They illustrate the function, if not always the form, of 'breaking news' as explored by Georgakopoulou (2008) which is to say that they allow the emplotment of significant individual and group identity work. In this respect it is important to emphasise that these extracts do not just relay gossip, but also intimate events of sickness and work that occur directly to the people telling the stories.

In conclusion, interstitial stories offer a further appreciation of how participants transpose experience through small story narratives, anchoring telling to place through spatial and temporal operations that involve both the characters and coordinates of the story world, the linguistic means used for the telling, and the unfolding temporal interaction of teller with place. The place-making of interstitial stories, however, does not operate like a map with names on it, but rather at a personal, human, level like a stream of storytelling that creates and superposes memories of different, albeit shared, corporeal and affective experiences.

Acknowledgments

This article draws on the PhD thesis Sandton: a linguistic ethnography of small stories in a site of luxury. University of the Witwatersrand. 2018. http://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/handle/10539/25897 . The author would like to acknowledge the funding received from the South African National Research Foundation and the Oppenheimer Memorial Fund.

Thank you to the participants to this research, to structures such as the Sandton City Mall, the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, the Sandton Convention Centre, as well as Johannesburg City. The project aimed to be inclusive and offer a wide image of South African society. Writing about African languages should be understood in this light.

Thank you to all those who helped with translation and transcription in the different phases of the project: Boikhutso, Mpho, Abena, Rosina, Nomadlozi and Linda Ngele who has since founded Lux Translations and Transcriptions. Any mistakes are my own.

Disclaimer

All of the views and analyses presented in this article are those of the author and do not in any way reflect the position of the host universities, nor that of the National Research Foundation.

References

Auer, J.C.P. 1984. Bilingual conversation. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Bamberg, M. 2006. Stories: big or small, why do we care? Narrative Inquiry, 16(1): 139-147. https://doi.org/10.1075/ni.16.L18bam [ Links ]

Bamberg, M. and A. Georgakopoulou. 2008. Small stories as a new perspective in narrative and identity analysis. Text & Talk, 28(3): 377-396. https://doi.org/10.1515/TEXT.2008.018 [ Links ]

Baynham, M. 2003. Narratives in space and time: beyond ''backdrop'' accounts of narrative orientation. Narrative Inquiry, 13(2): 347-366. https://doi.org/10.1075/ni.13.2.07bay [ Links ]

Baynham, M. 2009. 'Just one day like today': scale and the analysis of space/time orientation in narratives of displacement. In J. Collins, S. Slembrouck and M. Baynham (eds.) Globalization and language in contact: scale, migration and communicative practices. London & New York: Continuum. [ Links ]

Baynham, M. 2015. Narrative and space/time. In A. De Fina and A. Georgakopoulou (eds.) The handbook of narrative analysis. Spaces of multilingualism. Language & Communication, 25: 197216. https://doi.org/10.1016/Uangcom.2005.05.002 [ Links ]

Blommaert, J. and A. De Fina. 2017. Chronotopic identities: on the timespace organisation of who we are. In A. De Fina, D. Okizoglu and J. Wegner (eds.) Diversity and super-diversity. Washington: Georgetown University Press. [ Links ]

Bock, Z. and C. Stroud. 2018. Zombie landscapes: Apartheid traces in the discourses of young South Africans. In A. Peck, Q. Williams and C. Stroud (eds.) Making sense of people, place and linguistic landscapes. London: Bloomsbury Press. [ Links ]

Brookes, H. 2014. Urban youth languages in South Africa: a case study of Tsotsitaal in a South African township. Anthropological linguistics, 56(3/4): 356-388. https://doi.org/10.1353/anl.2014.0018 [ Links ]

de Certeau, M. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life (S. Rendall, Trans.). Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press. [ Links ]

De Fina, A. 2003. Crossing borders: time, space, and disorientation in narrative. Narrative Inquiry, 13(2): 367-391. https://doi.org/10.1075/ni.13.2.08def [ Links ]

De Fina, A. 2009a. Narratives in interview - the case of accounts (for an interactional approach to narrative genres). Narrative Inquiry, 19(2): 233-258. https://doi.org/10.1075/ni.19.2.03def [ Links ]

De Fina, A. 2009b. From space to spatialization in narrative studies. In J. Collins, S. Slembrouck and M. Baynham (eds.) Globalization and language in contact: scale, migration and communicative practices. London & New York: Continuum. [ Links ]

De Fina, A. and A. Georgakopoulou. 2008. Analysing narratives as practices. Qualitative Research, 8(3): 379-387. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794106093634 [ Links ]

De Fina, A. and A. Georgakopoulou. (eds.). 2015. The handbook of Narrative Analysis. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell. [ Links ]

Ebongue, A. E. and E. Hurst. (eds.). 2017. Sociolinguistics in African contexts: perspectives and challenges. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. [ Links ]

Foucault, M. 2004. Des espaces autres. Empan, 2(54): 12-19. https://doi.org/10.3917/empa.054.0012 [ Links ]

Freeman, M. 2006. Life "on holiday"? In defence of big stories. Narrative Inquiry, 16(1): 131-138. https://doi.org/10.1075/ni.16.L17fre [ Links ]

Genette, G. 1966. Frontières du récit. Communications, 8: 152-163. https://doi.org/10.3406/comm.1966.1121 [ Links ]

Georgakopoulou, A. 2003. Plotting the ''right place'' and the ''right time'': place and time as interactional resources in narrative. Narrative Inquiry, 13(2): 413-432. https://doi.org/10.1075/ni.13.2.10geo [ Links ]

Georgakopoulou, A. 2005. Same old story? On the interactional dynamics of shared narratives. In U. M. Quasthoff and T. Becker (eds.) Narrative interaction. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing. [ Links ]

Georgakopoulou, A. 2007. Small stories, interaction and identities. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing. [ Links ]

Georgakopoulou, A. 2008. 'On MSN with buff boys': self- and other-identity claims in the context of small stories. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 12(5): 597-626. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9841.2008.00384.x [ Links ]

Georgakopoulou, A. 2015. Sharing as rescripting: place manipulations on YouTube between narrative and social media affordances. Discourse, Context & Media, 9: 64-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2015.07.002 [ Links ]

Georgakopoulou, A. 2017. Narrative/life of the moment: from telling a story to taking a narrative stance. In B. Schiff, A. E. McKim and S. Patron (eds.) Life and narrative: the risks and responsibilities of storying experience. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Gieryn, T.F. 2000. A space for place in sociology. Annual Review of Sociology, 26: 463-496. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.463 [ Links ]

Goebel, W. and S. Schabio. (eds.). 2013. Locatingpostcolonial narrative genres. New York & London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Goffman, E. 1959. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Anchor Books, Doubleday. [ Links ]

Goffman, E. 1972. The interaction ritual: essays on face-to-face behaviour. London: Allan Lane, The Penguin Press. [ Links ]

Goffman, E. 1986. Frame analysis: an essay on the organization of experience. Boston: Northeastern University Press. [ Links ]

Greimas, A.J., P. Ricoeur, P. Perron and F. Collins. 1989. On narrativity. New Literary History 20(3): 551-562. https://doi.org/10.2307/469353 [ Links ]

Harrison, P., A. Masson and L. Sinwell. 2014. Alexandra. In P. Harrison, G. Gotz, A. Todes and C. Wray (eds.) Changing space, changing city: Johannesburg after Apartheid. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. [ Links ]

Hurst-Harosh, E. 2019. Tsotsitaal and decoloniality. African Studies, 78(1): 112-125. https://doi.org/10.1080/00020184.2018.1480847 [ Links ]

Koven, M. 2002. An analysis of speaker role inhabitance in narratives of personal experience. Journal of Pragmatics, 34(2): 167-217. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(02)80010-8 [ Links ]

Kunene Nicolas, R., M. Guidetti and J-M Colletta. 2017. A cross-linguistic study of the development of gesture and speech in Zulu and French oral narratives. Journal of child language, 44(1): 36-62. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000915000628 [ Links ]

Krog, A., N. Mpolweni and K. Ratele. 2009. There was this goat: investigating the Truth Commission testimony of Notrose Nobomvu Konile. Scottsville: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press. [ Links ]

Labov, W. and J. Waletzky. 1997 [1967]. Narrative analysis: oral versions of personal experience. Journal of Narrative and Life History, 7(1-4): 3-38. https://doi.org/10.1075/jnlh.7.02nar [ Links ]

Lafon, M. 2005. The future of isiZulu lies in Gauteng: the importance of taking into account urban varieties for the promotion of African languages. Paper presented at The Standardisation of African Languages in South Africa.

Makalela, L. 2004. Making sense of BSAE for linguistic democracy in South Africa. World Englishes, 23(3): 355-366. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.0883-2919.2004.00363.x [ Links ]

Massey, D. 1995. Places and their pasts. History workshop journal, 39(Spring): 182-192. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4289361 [ Links ]

Mbembe, A. 2008. Aesthetics of superfluity. In S. Nuttall and A. Mbembe (eds.) Johannesburg the elusive metropolis. Johannesburg: Wits University press. [ Links ]

Mishler, E. 2006. Narrative and identity: the double arrow of time. In A. de Fina, D. Schiffrin and M. Bamberg (eds.) Discourse and identity. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Ochs, E. and L. Capps. 2001. Living narrative: creating lives in everyday storytelling. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Oostendorp, M., T. Jones. 2015. Tensions, ambivalence, and contradiction: a small story analysis of discursive identity construction in the South African workplace. Text & Talk, 35(1): 25-47. http://doi.org/10.1515/text-2014-0030 [ Links ]

Prince, G. 1988. The disnarrated. Style, 22(1): 1-8. https://doi.org/https://www.jstor.org/stable/42945681 [ Links ]

Prince, G. 1997. Narratology and narratological analysis. Journal of Narrative and Life History, 7(1-4): 39-44. https://doi.org/10.1075/jnlh.7.03nar [ Links ]

Rampton, B. 1997. Sociolinguistics and cultural studies: new ethnicities, liminality and interaction. Working papers in urban language and literacies 4. Universiteit Gent, University at Albany, Tilburg University, King's College London.

Ricoeur, P. 1983. Temps et récit: tome 1. Paris: Editions du seuil. [ Links ]

Ryan, M.-L. 2009. Space. In P. Hühn, J. Pier, W. Schmid and J. Schönert (eds.) Handbook of narratology. Berlin & New York: Walter de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Sacks, H. 1974. On the analysability of stories by children. In R. Turner (ed.) Ethnomethodology: selected readings. Middlesex: Penguin Education. [ Links ]

Schiffrin, D. 2006. In other words: variation in reference and narrative. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Schiffrin, D. 2009. Crossing boundaries: the nexus of time, space, person, and place in narrative. Language in Society, 38: 421-445. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404509990212 [ Links ]

Stein, P. 2008. Multimodal pedagogies in diverse classrooms: representation, rights and resources. London and New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Stroud, C. 1998. Perspectives on cultural variability of discourse and some implications for code-switching. In P. Auer (ed.) Code-switching in conversation: language, interaction and identity. London & New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Stroud, C. and D. Jegels. 2014. Semiotic landscapes and mobile narrations of place: performing the local. IJSL - International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 2014(228): 179-199. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl-2014-0010 [ Links ]

Todorov, T. 1984. Mikhail Bakhtin: the dialogical principle (W. Godzich, Trans.). Minneapolis & London: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Tonnelat, S. 2003. Interstices urbains, les mobilités des terrains délaissés de l'aménagement. Chimères, 52: 134-151. [ Links ]

Tonnelat, S. 2008. 'Out of frame': the (in)visible life of urban interstices - a case study of Charenton-le-Pont, Paris, France. Ethnography, 9(3): 291-324. https://doi.org/10.1177/1466138108094973 [ Links ]

Tufi, S. 2017. Liminality, heterotopic sites, and the linguistic landscape: the case of Venice. Linguistic Landscape, 3(1): 78-99. https://doi.org/10.1075/ll.3.1.04tuf [ Links ]

Turner, V. 1969. The ritual process: structure and anti-structure. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

Vigouroux, C.B. 2009. A relational understanding of language practice: interacting timespaces in a single ethnographic site. In J. Collins, S. Slembrouck and M. Baynham (eds.) Globalization and language in contact: scale, migration and communicative practices. London & New York: Continuum. [ Links ]

Wortham, S.E.F. 2000. Interactional positioning and narrative self-construction. Narrative Inquiry, 10(1): 157-184. https://doi.org/10.1075/ni.10.1.11wor [ Links ]

1 Ethical clearance was provided by the University of Witwatersrand under Protocol number H15/07/23.