Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus (SPiL Plus)

versão On-line ISSN 2224-3380

versão impressa ISSN 1726-541X

SPiL plus (Online) vol.62 Stellenbosch 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.5842/62-0-907

ARTICLES

Pre-nominal DP modifiers and penultimate lengthening in Xitsonga

Seunghun J. LeeI; Kristina RiedelII

IInternational Christian University, Japan and University of Venda, South Africa. E-mail: seunghun@icu.ac.jp

IIDepartment of Linguistics and Language Practice, University of the Free State, South Africa. E-mail: riedelk@ufs.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Bantu languages generally have noun-initial DP word order but they typically allow for demonstratives, and in some languages also the quantifier meaning 'each, every', to precede the noun. Beyond this, Bantu languages generally allow changing the relative order of the post-nominal modifiers, which leads to subtle (focus-related) changes in meaning. Bantu languages generally do not allow for adjectives, numerals, and possessives to appear before the noun. However, Xitsonga allows such orders and these orders trigger lengthening effects. In this paper, we discuss DP word order alternations in Xitsonga and their effects on prosody in terms of penultimate lengthening. We show that there is a stable, statistically significant effect on length which can be demonstrated experimentally.

Keywords: nominal modifiers, penultimate lengthening, Xitsonga, Bantu, syntax-prosody

1. Introduction

In this paper, we examine apparent focus effects on prosody in Xitsonga in the form of longer penultimate lengthening (PL) that is shown by modifiers appearing in marked word orders where these modifiers receive a focused interpretation. We show that, for at least certain types of nominal modifiers, the marked word order of noun and modifier triggers longer PL on the modifier. However, this longer PL is position-dependent, with post-verbal objects showing a greater effect than the modifier in pre-verbal subjects.

As in other Bantu languages with phonological PL, Xitsonga displays several levels of PL, with the longest appearing on the final word in an intonational phrase but some PL appearing on each prosodic word.1 However, up to now, the existence of such levels has not been investigated experimentally but was based on impressionistic data of vowel length. In our experiment, we establish a baseline PL, the longest (maximum) PL, and the longer than baseline (but shorter than longest) PL that appears on certain pre-nominal modifiers in the marked word order.

Xitsonga (Guthrie code S53; alternative names include Shangaan and Tonga) is spoken by about 5,5 million first-language speakers in South Africa, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe. PL in Xitsonga has been described by Beuchat (1962), Kisseberth (1994), and Zerbian (2007). Xitsonga DPs have not been studied in any detail but basic descriptions of nominal morphosyntax are provided in Baumbach (1987) and du Plessis, Nxumalo and Visser (1995).

Bantu languages generally allow variable word order in the DP in the post-nominal position (Rugemalira 2007). However, besides this flexibility, there are variations in the grammatical orders of DP modifiers in pre-nominal positions in Southern Bantu languages. These variations have received no detailed attention in the literature, even though they have been noted in recent work on a number of Southern Bantu languages (Letsholo and Matlhaku 2014 and Creissels 2016 for Setswana, Guthrie code S31; Mokoaleli, Riedel and Furumoto forthcoming for Sesotho, Guthrie code S33; de Dreu 2008 for Zulu2, Guthrie code S42). Xitsonga allows pre-nominal demonstratives, numerals, and adjectives. In fact, Xitsonga allows the ordering of DP-internal modifiers in every logically possible order, including with multiple modifiers. However, here we will focus on DPs that include a noun and only one modifier, as this is how our experimental data was collected (but see Riedel and Lee 2021 for a discussion of complex DPs and their prosody). As has been noted for other Bantu languages which allow this pre-nominal nominal modifier placement, including Zulu (de Dreu 2008), two varieties of Makonde (Guthrie code P23; Devos 2004, Kraal 2005), and Setswana (Letsholo and Matlhaku 2014), the marked word order is associated with focus effects in Xitsonga. In this paper, we show that in Xitsonga the pre-nominal element is prosodically marked with a longer duration of PL when compared to post-nominal elements in non-sentence-final position.

Prosodically, PL (marked with a colon in our examples) marks the right edge of a prosodic level in Xitsonga at the levels of the prosodic word, phonological phrase, or intonational phrase. While phonetic studies on this are rare, languages with several "levels" of PL have been described in the literature for some time. For example, Hyman (2009) notes the relevance of the utterance for Southern Bantu PL patterns, based on work such as Cole's (1955: 55) description of Setswana PL: "Full length occurs in the penultimate syllable of a word pronounced in isolation or at the end of a sentence [...] When a word is in non-final sentence position, it still retains its penultimate accent, but in much lesser degree, i.e. only half-length is used". Fortune (1980) reports a similar type of half-lengthening in Shona.

We are interested in the lengthening patterns at all three levels: the word level in non-prominent positions (i.e. in non-phrase-final position) as the baseline PL and how this might be affected by marked word order associated with focus, the PL found at the end of phonological phrases, and PL at the end of the intonational phrase (which would correspond to the "full" length described in Cole 1955). The paper is structured as follows: section 2 provides background on Xitsonga DPs and PL, section 3 provides the necessary background on Bantu DPs and their prosody, section 4 describes the experiment, section 5 discusses the results and implications, and section 6 offers our conclusions.

2. Xitsonga PL and DPs

Like in other Bantu languages (Carstens 1991, Rugemalira 2007), in Xitsonga, nominal modifiers appear after the noun in unmarked word order (1). Where these noun phrases appear in isolation or in sentence-final position, the penultimate vowel of the modifier shows the most marked PL (1a, c, and d). However, note that demonstratives do not normally show PL (1b). This seems to mirror what has been found for both tones and PL in other Bantu languages in a number of syntax-prosody studies (Kanerva 1990a, 1990b; Kisseberth 1994; Zerbian 2007; Downing and Mtenje 2011; Clemens and Bickmore 2020).

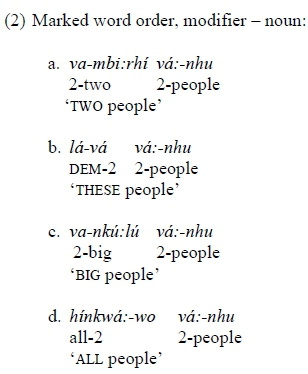

When the modifier is emphasized, it appears pre-nominally and the noun shows longer PL (in 2) because it occurs in the intonational-phrase-final position (Kisseberth 1994). But certain types of modifiers in the marked pre-nominal position also show longer PL than other (non-pre-nominal) modifiers when they appear in non-final position. A pre-nominal modifier gets a clear focus interpretation, according to our consultants. The same kind of pattern has been reported for numerous other Bantu languages (see examples below; the element in focus is marked with small caps in the translation).

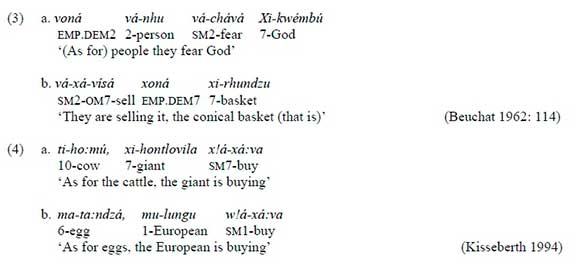

The focus effect of the pre-nominal order has also been noted for demonstratives in Xitsonga (Beuchat 1962; see examples 3a and b below), as were PL effects in pre-verbal and final positions (4).

Based on these facts, we take the focal properties and the general pattern of PL in Xitsonga as established and focus on determining experimentally whether there is a clear and statistically significant phonetic pattern for several levels of PL in Xitsonga that are related to a pre-nominal position of an element in the DP.

3. Bantu DP

In this section, we provide a brief overview of the literature on the morphosyntax of Bantu DPs and what is known regarding their prosody and focus patterns.

3.1 Bantu DP word order and structure

The properties of DPs or noun phrases in Bantu languages have received relatively little attention in the literature beyond studies of noun classes, the augment, and the internal structure of nouns and their prefixes. With very few exceptions, nominal modifiers in Bantu languages agree with their head noun in noun class/number and can normally stand on their own (for general overviews, cf. Katamba 2003). There are different patterns for what constitutes the unmarked or marked, and/or grammatical orders of demonstratives across Bantu (cf. Rugemalira 2007 for a discussion of several languages of Tanzania, Van de Velde 2019, and Van de Velde 2020 for an overview of Bantu languages). While there is a clear basic order of modifiers that is fairly consistent across the Bantu languages for which it has been described, in post-nominal position these modifiers are fairly freely ordered with some scope/focus effects found when they appear in the more marked orders. Existing studies of nominals and noun phrases include: Carstens (1991, 2008) who discusses Swahili (Guthrie code G42) DP structures; Kanampiu and Muriungi (2019) who discuss Kïïtharaka (Guthrie code E54) DP orders and motivate different types of DP structures and movement processes to explain the range of possible orders for different types of quantifiers and other nominal modifiers observed; Tada (2016) who looks at the order of post-nominal adjectives in Zulu; and Letsholo (2006), Letsholo and Matlhaku (2014), and Creissels (2014) who discuss Setswana noun phrases and modifiers.

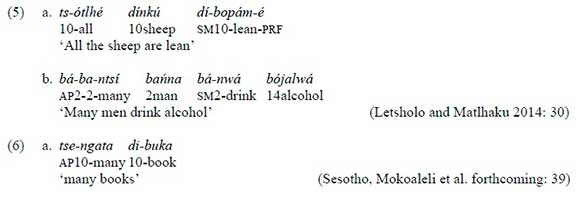

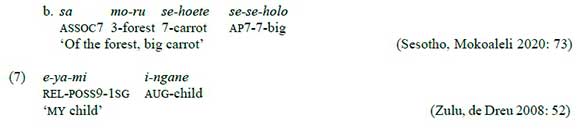

Like Xitsonga, several other Southern Bantu languages also allow pre-nominal DP modifiers, as illustrated for Setswana in (5), Sesotho in (6), and Zulu in (7). Mokoaleli (2020) and de Dreu (2008) note the focused/emphatic readings of pre-nominal DP modifiers.

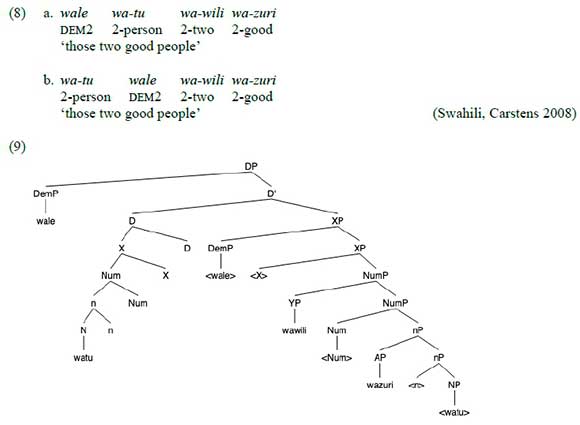

Carstens (2008) proposes an extended DP for Swahili, where the noun moves to D via head movement, while demonstratives can move to a specifier of DP where that is licensed by special definiteness effects, as shown in (9), which represents the Swahili phrase in (8a). In this structure, the number wawili 'two (class 2)' is attached as a specifier of NumP, while the qualitative adjective is a specifier of nP. For a construction such as (8b), the demonstrative would simply stay in situ in Carsten's analysis.

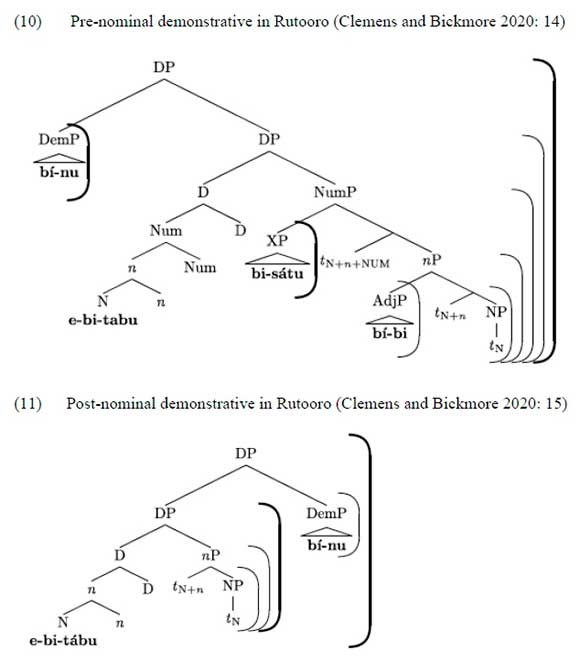

Clemens and Bickmore (2020) largely follow Carstens (2008) in their analysis of the DP structure in Rutooro (Guthrie code JE12), shown in (10). However, Clemens and Bickmore assume that the demonstrative is base-generated as an adjunct to DP, rather than moving there, and that this can happen on the left (10) or the right (11), leading to demonstrative-initial or demonstrative-final word orders.4Clemens and Bickmore (2020) also show that Rutooro has a different prosodic phrasing pattern and different syntactic properties for demonstratives and the agreeing quantifier meaning 'all' (but not other quantifiers or numerals), which can appear pre-nominally, unlike other nominal modifiers.

While the demonstrative is higher than the other modifiers in both structural accounts, an analysis where the focused element moves to the specifier position could be accommodated fairly easily for structures with a single pre-nominal modifier. In this case, the main difference between Swahili and Xitsonga DPs is that Swahili allows a demonstrative to appear immediately after the noun, but Xitsonga patterns with Rutooro in preferring the demonstrative to appear in final position when it does not precede the noun.5 An alternative account may involve nominalisation of modifiers, as proposed by Van de Velde (2020). However, his proposal that nominal modifiers can become noun phrase constituents via nominalisation, where they first become phrasal and then become part of another phrase (i.e. no longer being phrasal), does not match our general understanding of phrase structure (based on operations such as Merge, Move, and Agree) where adjectives, numerals, and demonstratives are always phrasal categories. In these respects, our understanding of syntax is similar to that on which studies such as Carstens (2008) or Clemens and Bickmore (2020) are also based. We think an account based on movement and pre-nominal positions offers a simpler explanation of the data presented here.

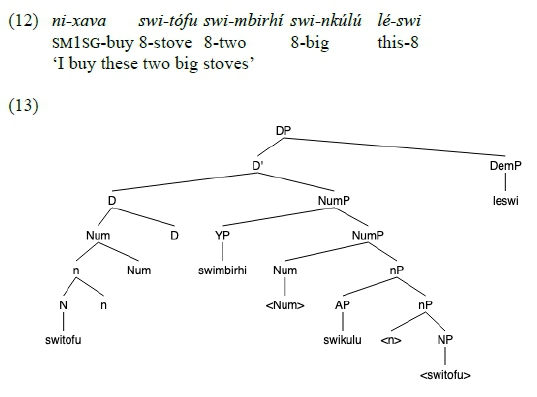

Following Clemens and Bickmore (2020), but treating the demonstrative (DemP) as a specifier, we assume that a Xitsonga DP, where the modifiers appear in the unmarked order like the one in (12), has the structure in (13).6

Most Bantu languages restrict which types of elements can appear pre-nominally, unlike Xitsonga. The simplest option for deriving constructions where nominal modifiers appear before the noun syntactically might be one or more adjuncts (following Clemens and Bickmore 2020) or multiple specifiers (following Carstens 2008) that are attached to the DP, potentially above the specifier/adjunct phrase hosting the DemP. Aboh (2004) proposes focus and topic projections inside the DP for Gungbe (a Gbe language primarily spoken in Benin). However, these are attached below D which would additionally require multiple landing sites for the noun (instead of just moving to D). It is possible that languages like Xitsonga and maybe also Rutooro have a FocP above D. However, this becomes even more complicated for the other possible marked orders in Xitsonga since several modifiers can appear pre-nominally which would potentially require multiple positions. We will leave these questions for further research.

3.2 The prosody of the DP in Bantu

PL can apply at different levels in Bantu languages: from the word level to the utterance, or to different types of clauses, such as w/z-questions versus statements (Hyman 2009). Earlier literature reports that the duration of the penultimate syllable is longer than other syllables in Bantu languages (Van Bulck 1952, Burssens 1954, Doke 1967). In Ikalanga (Guthrie code S16), for example, /ku-túm-a/ 'to send' is realised as [kutü:ma] with a lengthened penultimate syllable and a falling tone when the word appears in the phrase-final position, but as [kutúma] without PL and with a simple high tone when it appears in non-phrase-final position (Hyman and Mathangwane 1998: 199).

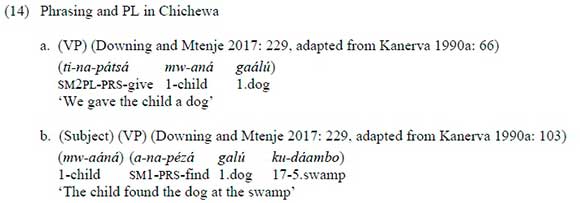

Studies on the prosody of Chichewa (Guthrie code N31) report that PL reflects prosodic structure (Kanerva 1990a, Downing and Mtenje 2017). The examples in (14) show that PL (marked with a double vowel in this dataset) indicates that a prosodic word is in phrase-final position. In (14a), the entire clause is grouped together and only the penultimate syllable of the last word /galú/ 'dog' is lengthened. In (14b), the same word appears in phrase-medial position and there is no lengthening. The overt subject of the sentence in (14b) shows that subjects in Chichewa are phrased separately from the rest of the clause, as evidenced by the lengthened penultimate vowel of the subject noun phrase in the pre-verbal position.

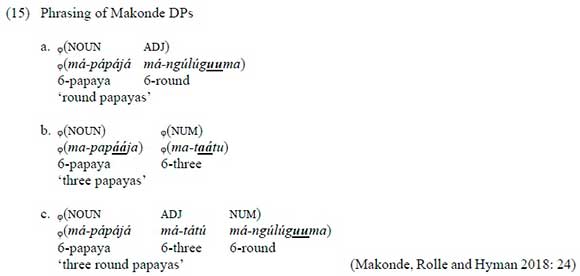

Rolle and Hyman (2018) analyse the prosodic patterns of DPs in Makonde, where adjectives and numeral modifiers follow the nominal head. The phrasing of these Makonde DPs is shown in (15). Here, the adjective is phrased together with the nominal head (15a), but the numeral is phrased separately (15b). Evidence for the phrasing asymmetry again comes from PL. Interestingly, when a nominal head in Makonde is followed by an adjective and a numeral, the numeral is phrased together with the preceding noun and adjective, displaying what Rolle and Hyman (2018) refer to as "prosodic smothering".

These types of phrasing differences show the variable nature of phrasing-induced PL, even when the morphosyntactic category of a word is the same; the presence or absence of PL appears to provide evidence for the internal structure of DPs. One caveat is that it is not clear how directly PL reflects the syntactic properties, rather than the prosodic properties, of these DPs and their constituents.

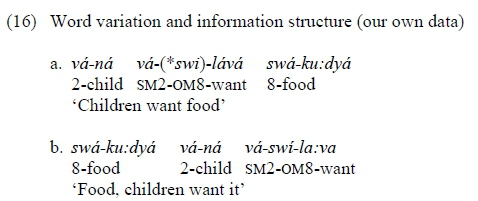

Zerbian (2007) notes that variation in word order is one way to encode information structure in Xitsonga. In (16a), a context-neutral sentence shows PL on the final prosodic word. Zerbian (2007: 66-67) shows that if an object marker co-occurs with a lexical object that is in situ, as in (16a), this has information structural effects, with emphasis on the object that is object-marked. In our own elicitation, consultants judged object markers in sentences such as (16a) to be ungrammatical. However, when the object DP is left-dislocated, as in (16b), an object marker agreeing with the dislocated noun swa-kudya '8-food' is required.

The Xitsonga data from earlier studies (Beuchat 1962, du Plessis et al. 1995) discussed in Zerbian (2007) is not marked for PL. Thus, our work is a start towards addressing Zerbian's remark that much work needs to be done regarding the prosody of Bantu languages. In this paper, we do just that and show that the prosodic structure indirectly reflects the DP-internal morphosyntactic structure.

Clemens and Bickmore (2020) show that prosody can be sensitive to syntactic movement in Rutooro noun phrases. Rutooro has asymmetrical phrasing patterns in the DP structure. Nouns modified by strong determiners and full relative clauses are marked with a high (H) tone whereas nouns modified by weak determiners, adjectives, and reduced relative clauses lack such a H tone. Clemens and Bickmore's proposal is that the presence or absence of a H tone is caused by generating modifiers in a DP-internal or DP-external position, respectively. The study does not address PL, but it shows the effect of syntactic structures on the phonology of Bantu DPs.

Aside from the patterns reported here for a small number of Bantu languages, the DP and its prosody remain an underexplored topic in Bantu linguistics. DP-internal PL is the major type of evidence used in Rolle and Hyman's (2018) work on prosodic smothering in Makonde. Our paper investigates whether focused prosodic words have any additional/longer PL in Xitsonga. Noting the differences in prosodic phrasing between subjects and objects in other Bantu languages, our stimuli sentences include the target DP in the subject and object positions which, as we will show, also influence the PL pattern in Xitsonga.

4. Phonetic evidence for Xitsonga PL

Having provided an overview of Xitsonga and Bantu DPs and relevant prosody above, in this section we describe how our data was collected and analysed, and what our results were.

PL in Xitsonga is reported to mark the boundary of an intonational phrase (Kisseberth 1994, Selkirk 2011). Whether or not penultimate syllables of the lower prosodic levels (phonological phrases and prosodic words) are also realised as lengthened vowels has not been reported. Anecdotally, one of the authors of this paper reports that PL is heard at the prosodic word level in naturalistic conversation amongst native speakers of Xitsonga. The scarcity of systematic studies on PL in Xitsonga or even other Bantu languages makes it difficult to evaluate whether penultimate syllables are always longer in Xitsonga. Hence, we conducted an experiment to investigate the length of penultimate syllables in different positions, namely pre- and post-verbal two-word DPs, and whether these DPs show prosodic marking of focus in the form of longer PL.

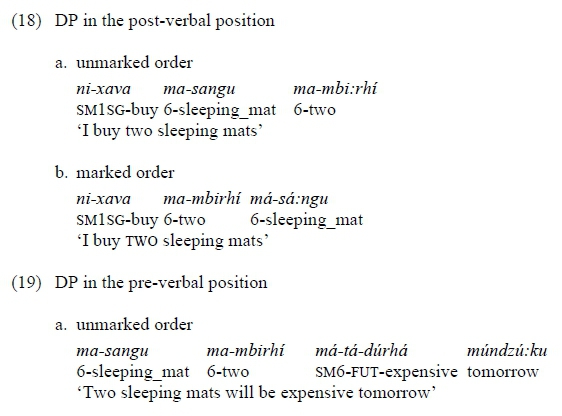

When a DP with a single modifier appears in the post-verbal position, all things being equal, we expect the duration of the penultimate syllable of the final prosodic word (in the unmarked word order, this would be the penultimate syllable of the DP modifier) to be the longest, since it is also the penultimate syllable of an intonational phrase. This is indeed confirmed by the data.

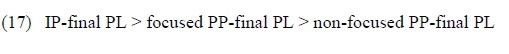

We assume that there are three potential relative lengths of PL: Intonational phrase (IP) final PL is the longest, while phonological phrase (PP) final PL is less long than IP-final PL, where focused PP-final PL is longer than non-focused PP-final PL. Finally, there are words without PL.

We now turn to describing our stimuli before describing the participants and other experimental details in the following subsections.

4.1 Stimuli

The stimuli consisted of 30 sentences with varying orders of the DP-internal elements. These sentences included the target DP as pre-verbal subject and as post-verbal object, with both types of sentences reflecting the unmarked word order with respect to subjects and objects in Xitsonga. In the stimuli with a pre-verbal DP, a post-verbal temporal modifier was also used. This was added to make the sentences sound more natural to the participants, not for prosodic or syntactic reasons. Pairs of sentences were constructed to investigate the difference between DPs with modifiers preceding the noun and DPs with modifiers following the noun in pre- and post-verbal positions because of the tendencies in Bantu languages to phrase subjects and other pre-verbal elements differently prosodically from objects and other post-verbal elements. The stimuli include different types of DP modifiers: numerals, adjectives, the agreeing quantifier meaning 'all', and a demonstrative. All subject sentences used ma-ta-durha mundzuku '(they) will be expensive tomorrow' as the frame and all object sentences used ni-xava 'I buy'.

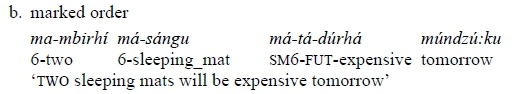

The nominal modifier follows the noun in (18a) and (19a), which is the unmarked word order in Xitsonga. When the nominal modifier precedes the head noun, as in (18b) and (19b), which is the marked word order in Xitsonga, the modifier is interpreted as being focused.

4.2 Participants

Eight Xitsonga speakers (four male and four female) all in their twenties participated in the study. All of them were students at a regional university majoring in the Xitsonga language as part of a teacher training program. Those who graduate from this program qualify to teach Xitsonga at secondary school level and receive basic training in linguistics as part of their curriculum, but this does not cover concepts related to information structure, such as topic and focus. The minimum number of years of English education that participants had is 14 years, and all of them identified themselves as being at an advanced level of English proficiency.

4.3 Data collection and processing

The Xitsonga data reported here was recorded in March 2020 in a quiet office at the University of Venda in Thohoyandou, Limpopo, South Africa. A Zoom H5 recorder mounted on a tripod was used. The sampling rate was 44,100 Hz with 16-bit quantization. After participants completed the consent form and a demographic questionnaire, stimuli sentences were presented using PowerPoint slides advanced by the experimenter. Participants were presented with five practice sentences before seeing the target stimuli. A set of randomized target sentences was presented, with one sentence per slide. The complete set was read three times by each participant, resulting in three repetitions for each target sentence. Sentences in each slide were read only once each time in order to avoid unnatural prosody from repetitions. Filler sentences were included in the experiment as distractors. A post-test interview confirmed that participants were not aware of the purpose of the experiment.

The recording sessions used 30 stimuli sentences (see Appendix A) that were each repeated three times by eight speakers. Half of the sentences had the target DP in the subject position and half had the target DP in the object position. The resulting 720 sentence tokens were then annotated using Praat (Boersma and Weenink 2019). For tokens where the target DP appears in the object position, the penultimate syllables of the last three words (i.e. the verb and the DP object consisting of the noun and its modifier) were further annotated with the following labels: final word (FW), penultimate word (PW), and antepenultimate word (AW). The penultimate syllable of the AW in the object sentences is always the verb form ni-xava 'I buy'. The AW's PL pattern can be considered the baseline. When the target DP appears in the subject position, the FW is the adverb mundzuku 'tomorrow' and the PW is ma-ta-durha 'they will be expensive'. The target penultimate syllables appear in the AW and in the fourth word from the end (4W). In these pre-verbal DPs, the PL pattern of PW is considered the baseline. The duration of the penultimate syllable of these prosodic words was extracted using a Praat script (Boersma and Weenink 2019) and then processed using R (R Core Team 2020).

4.5 Results

In this section, we first report the results of our analysis of PL in post-verbal DPs (i.e. objects), then we present the results of our analysis of PL in pre-verbal DPs (i.e. subjects). Finally, we present the differences between lexical and functional modifiers for PL in different positions.

In Figure 1 the durations of penultimate syllables in the FW, in the PW, and in the AW are plotted as a boxplot. As we expected, the penultimate syllable of the FW is the longest both in the unmarked and the marked conditions. Our interests lie in the penultimate syllable of the PWs. The duration of penultimate syllables is longer in the marked condition (where the PW is the pre-nominal modifier) than in the unmarked condition (where the PW is the post-nominal modifier): t(282.28) = -6.45, p < 0.001. This finding suggests that for preposed modifiers in a DP, the marked word order shows a phonetic reflex in the form of longer penultimate syllable lengthening.

In Figure 2 we present each speaker's PL patterns of post-verbal noun phrases, with one nominal modifier appearing in the marked and unmarked conditions. Figure 2 shows that the FW has the longest penultimate syllable for all participants except for speaker TSO047. While most participants display the FW with the longest penultimate syllable, when the duration of penultimate syllables in three prosodic words is examined, two groups emerge: one group (TSO048, TSO050, TSO051, TSO052) expresses a pre-nominal modifier with a longer duration on the penultimate syllable (t(150.1) = -6.76, p < 0.001), while the durational difference of penultimate syllables in the other group (TSO047, TSO049, TSO053, TSO054) is significant (t(154.27) = -2.54, p = 0.01),7with a higher probability of facing a type-1 error.

Participant TSO047 does not exhibit any prosodic effect on the duration of the penultimate syllable of the pre-nominal modifier when comparing the marked and unmarked conditions. The speaker may exhibit a task effect and may have produced an unnatural prosody when reading the sentences. We rule out a possibility of dialectal variation, as she comes from the town of Malamulele where five other participants (TSO049, TSO050, TSO051, TSO052, TSO053) also came from.

The stimuli set includes four different types of modifiers: adjectives, demonstratives, numerals, and quantifiers. In the marked order, the PW is the modifier in the pre-nominal position, and in the unmarked order, the PW is the noun head. Examining PL patterns shown by the element in the PW position in these two orders would reveal whether or not pre-nominal modifiers display longer PL. We report our results divided by two groups based on the types of modifiers: adjective and numerals are lexical words, and demonstratives and quantifiers are functional words. The difference in the duration of the penultimate syllable in PWs with adjective and numeral modifiers is significant: t(207) = -7.1984, p < 0.001. When the modifiers are function words such as demonstratives and quantifiers, the durational difference is not significant: t(76.78) = -0.30994, p = 0.76. As shown in Figure 3(a), lexical modifiers in the pre-nominal position display longer PL in PW. The functional words such as demonstratives and quantifiers do not display such differences, as shown in Figure 3(b).8

The right panel in Figure 3 masks the observation that demonstratives do not display PL in either post-nominal or pre-nominal position. When we examined the results for each speaker, all speakers produced demonstratives without PL in the pre-nominal position, but demonstratives in the postnominal position were produced with two distinct patterns: one group (three speakers) exhibited no PL in the sentence-final demonstrative (left panel in Figure 4(a)), while the other group did exhibit PL in that demonstrative (right panel in Figure 4(a)). Since the speaker group that produced post-nominal demonstratives with PL is expected to behave similarly to the lexical group, we compared the duration of PL in the PW position - no statistical significance (t(86.5) = 1.47, p = 1.43) was found between the marked and the unmarked group.

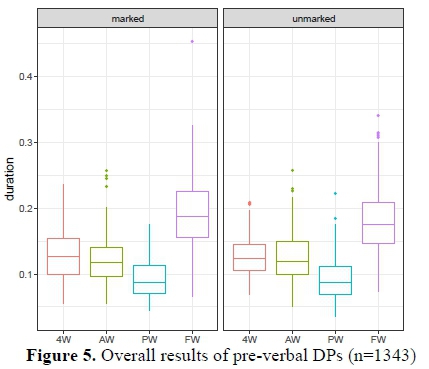

The next set of graphs shows the results of measurements of tokens where the target DP is located in the pre-verbal subject position. The FW is the adverb mundzuku 'tomorrow' and the PW is the tensed verb ma-ta-durha 'they will be expensive'. The modifier and the noun appear in the AW position and in the prosodic word position before the AW (called "4W" in this paper).

Figure 5 shows that the duration of the penultimate vowel of FW is the longest in both conditions (t(333.6) = -1.67, p = 0.09), and that of PW is the shortest across both conditions (t(334.78) = -0.61, p = 0.54). The frame sentence displays consistent results, which allows us to examine the PL in AW and 4W. When the marked and unmarked conditions are compared, the durational differences of the penultimate vowels in the AW position are not significant (t(331.9) = 0.64, p = 0.52). The durational difference is not significant for 4W either (t(312.38) = -0.84687, p = 0.40).

Although the durations of the penultimate vowels in the two conditions are not significantly different, PL in both 4W and AW positions is longer than that in the PW position. PL is presumably absent in the PW, which is the verb of the sentence. When PL in all four positions was tested, we found a statistically significant difference in PL duration by the position of PL in a sentence (f(3) = 299.8, p < 0.001). A Tukey post-hoc test revealed that FW resulted in a longer duration on average than PW (92 ms), a longer duration on average than AW (62 ms), and a longer duration on average than 4W (68 ms). A subsequent groupwise comparison showed a longer duration of PL on FW, but no durational difference between 4W and AW.

In the post-verbal condition, we observed that lexical modifiers display a longer penultimate syllable in the marked condition (Figure 3). In Figure 6 which looks at lexical versus functional modifiers in pre-verbal position, the two adjacent graphs show that the difference in the duration of the penultimate syllable in pre-nominal modifiers (4W) in the marked condition and that of 4W in the unmarked condition is statistically significant (t(224.45) = 2.14, p < 0.05). For the lexical modifiers: in the marked condition, PL is an average of 10 ms longer than in the unmarked condition. With the functional modifiers, the pattern is reversed: the marked condition of the functional modifiers has shorter PL than the unmarked condition (t(92.3) = -2.19, p < 0.05).

We also examined the pre-verbal data per participant as well as by modifier type. What we found was consistent with the post-verbal data in that the modifier in the marked condition (in the position 4W) was realised with a longer duration in the penultimate syllable.

To conclude this section, the PL patterns in Xitsonga DPs with a single modifier are summarized in Table 1 In the post-verbal position, IP-final prosodic words show maximum duration of PL (IP-final PL in (17): max PL). In the marked pattern, pre-nominal lexical modifiers display longer PL (focused PP-final PL in (17): longer PL), whereas pre-nominal functional modifiers do not exhibit longer PL (but rather a normal PL). In the post-verbal position, nouns in the unmarked pattern are realised with normal PL. All the remaining prosodic words in pre-verbal and post-verbal positions display some degree of PL (non-focused PP-final PL in (17): normal PL).

5. Discussion: Phrasing of Xitsonga DPs

The data presented in section 4 matches what has been reported for prosodic phrasing in other Bantu languages in terms of positional effects (as in Chichewa and Rutooro) and the differences between different types of modifiers (as in Rutooro and Makonde).

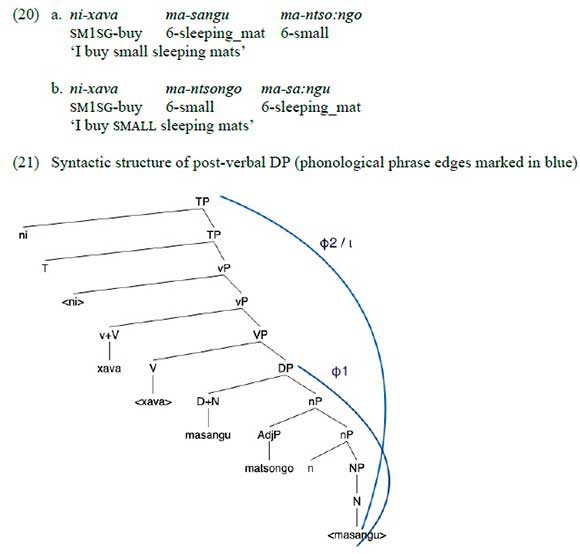

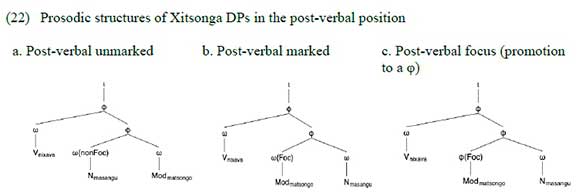

The prosodic phrasing of Xitsonga DPs with a pre-nominal or post-nominal modifier is proposed to be matched to the syntactic structure assumed in (21). Three prosodic levels indirectly match with structure in the morphosyntactic component of the grammar: an intonational phrase (i) matches a clause (CP or TP), a phonological phrase (9) matches a syntactic phrase (XP), and a prosodic word (co) matches a morphological word (cf. Selkirk 2011).

The prosodic phrasing of post-verbal DPs is shown in (22). The projections of the noun and modifier in (22a-b) are not matched by a phonological phrase in the prosodic structure because each only contains a single prosodic word. In Xitsonga, phonological phrases are required to have minimally two prosodic words, hence they are prosodic words which do not form phonological phrases on their own (see Lee and Selkirk forthcoming). The underlying structure in (22a) differs from (22b), where the pre-nominal modifier is focused. We propose that the focused pre-nominal modifier is promoted to a phonological phrase (q>Foc), as shown in (22c). We argue that this promotion to 9 is the source of the longer PL in the focused pre-nominal DP.

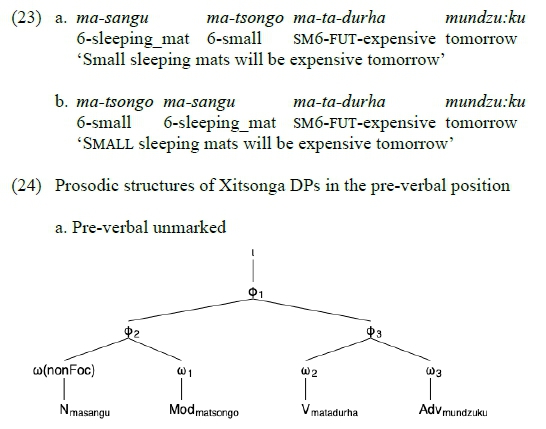

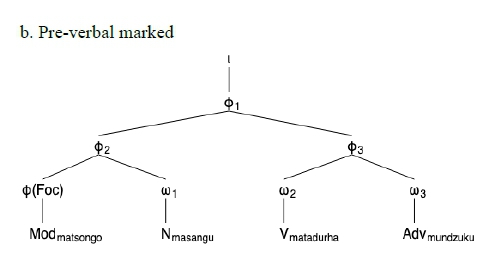

Examples with DPs in the pre-verbal position are presented in (23), and their prosodic structures are shown in (24). As in (22b), the focused pre-nominal modifiers display longer PL, suggesting that they are promoted prosodically from prosodic words to phonological phrases. The duration of the penultimate syllable in the modifiers in (24a) and the noun in (24b) is also lengthened, but to a lesser degree than in a focused pre-nominal modifier because both the modifiers and the noun are the final prosodic words of the phonological phrase (φ2).

Patterns of PL differ between Xitsonga DPs that appear in the post-verbal position and those that appear in the pre-verbal position. In the pre-verbal position, DPs are phrased on their own, which means that the PL of the final prosodic word of the phonological phrase (i.e. the DP) occurs. As shown above, a similar type of asymmetry has been reported for Chichewa (Kanerva 1990a, Downing and Mtenje 2017) where the pre-verbal subject DP forms a prosodic unit separately from the rest of the verb phrase but not DPs in post-verbal non-dislocated position. Xitsonga DPs show a comparable pattern to Chichewa, because the final prosodic word of the pre-verbal phonological phrase displays PL.

Demonstratives in Xitsonga behave differently from other modifiers in that they do not undergo PL in any position for most of the speakers we have worked with. In this study, la-ma 'DEM-6' was used, which has the demonstrative base la followed by a class 6 marker. Possible explanations include the length of the demonstrative, positional restrictions on the demonstrative, or the prosodic status of the demonstrative. First, the demonstrative has only two syllables, while other modifiers in our stimuli set are trisyllabic when including the noun class prefix. Minimality effects on prosodic stems in Bantu languages are well known (Downing 2000, 2001), and the demonstrative lama cannot form a prosodic word in Xitsonga because the stem la- is not long enough. Second, demonstratives tend to behave differently syntactically from other nominal modifiers across Bantu; the positional restrictions of demonstratives in Swahili and Rutooro noted above illustrate this. The lack of PL in Xitsonga demonstratives may simply reflect a special syntactic status of demonstratives being realised in the prosodic structure, which begs for a prosody-based account. Third, in the prosodic structure, we could assume that demonstratives encliticize to the preceding prosodic structure without forming their own prosodic word. We can entertain a scenario in which PL of an intonational phrase or a phonological phrase does not occur when the final element of the intonational phrase is an unparsed element, such as demonstratives in Xitsonga. This idea needs to be tested in future studies.

An alternative analysis of the pre-nominal modifier with PL in post-verbal position is that the modifier forms its own syntactic phrase (either a DP or a DP-linked phrasal category such as DemP) which appears in the immediately-after-verb (IAV) position. This position is known to be focused in a number of Bantu languages, including Xitsonga (although this requires further study), and is therefore marked prosodically for focus. Such an analysis would be closer to Van de Velde (2020) but would not account for the additional PL in pre-verbal position, which is not a general focus position in Xitsonga or any Bantu language, apart from the problems noted above. We therefore do not think this is an IAV effect (syntactically). However, more research on the prosodic marking of elements in IAV and how longer and shorter phrases of different types behave in Xitsonga would be needed to evaluate this prosodically.

6. Conclusions

Xitsonga PL is increased when a focused element within the DP appears in the pre-nominal position. Not unexpectedly, based on what has been observed for other Bantu languages with PL or similar phrasal prosodic patterns, there is a difference between subjects and objects or, potentially more generally, between pre- and post-verbal DPs (this requires further study), as well as a difference between different classes of words.

While we have established a first baseline for PL patterns in Xitsonga noun phrases, the results give rise to many new questions and highlight the need for further studies. While the types of modifiers in Xitsonga DPs are a fairly small set, more research is needed on what might cause the difference observed between demonstratives, quantifiers, adjectives, and numbers. Additionally, more data needs to be added to the existing set to see how robust the effects observed here are, and to address remaining questions such as whether all types of demonstratives fail to show PL and whether all quantifiers show the same pattern.

All examples show maximum PL (maxPL) in the final prosodic word, and two mechanisms can be identified as a source for the maxPL: either the presence of an intonation phrase boundary triggers maxPL, or maxPL may occur due to a cumulative effect that occurs when the phonological phrase boundary and the intonational phrase boundary follow the same word. This effect can be distinguished if we construct examples which have final prosodic words that are not part of the preceding phonological phrase. If such constructions can be examined in Xitsonga, we would be able to better identify the source of maxPL.

PL may, like high-tone spreading in Xitsonga, differentiate between different types of morphemes (e.g. stems or agreement) in different parts of the grammar. However, more research is needed to establish whether this is the case and, if so, what happens in verbal domains and with locative suffixes (seeing as these are most relevant for the analysis of PL). Finally, preliminary data on Sesotho collected by the authors has shown that the Xitsonga pattern is also found in other Southern Bantu languages.

References

Aboh, E.O. 2004. Topic and Focus within D. Linguistics in the Netherlands 21: 1-12. [ Links ]

Baumbach, E.J.M. 1987. Analytical Tsonga grammar. Pretoria: University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Beuchat, P.D. 1962. Additional notes on the tonomorphology of the Tsonga noun. African Studies 21: 105-122. https://doi.org/10.1080/00020186208707162 [ Links ]

Boersma, P. and D. Weenink. 2019. Praat: Doing phonetics by computer. Available online: http://www.praat.org (Accessed 17 December 2019).

Burssens, A. 1954. Introduction à l'étude des langues bantoues du Congo belge. Anvers: De Sikkel. [ Links ]

Carstens, V.M. 1991. The Morphology and Syntax of Determiner Phrases in Kiswahili. unpublished doctoral dissertation, uCLA. [ Links ]

Carstens, V.M. 2008. DP in Bantu and Romance. In C. De Cat and K. Demuth (eds.) The Bantu-Romance connection: A comparative investigation of verbal agreement, DPs, and information structure. Amsterdam: Benjamins. pp. 131-165. https://doi.org/10.1075/la.131.10car [ Links ]

Clemens, L. and L. Bickmore. 2020. Attachment height and prosodic phrasing in Rutooro. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory. Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11049-020-09492-w (Accessed 13 January 2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-020-09492-w

Cole, D.T. 1955. An introduction to Tswana grammar. London: Longmans. [ Links ]

Creissels, D. 2016. Additive coordination, comitative adjunction, and associative plural in Tswana. Linguistique et Langues Africaines 2: 11-42. [ Links ]

De Dreu, M. 2008. The Internal Structure of the Zulu DP. Unpublished Master's thesis, University of Leiden. [ Links ]

Devos, M. 2004. A Grammar of Makwe. Unpublished PhD dissertation, University of Leiden. [ Links ]

Doke, C.M. 1967. The Southern Bantu languages. London: Published for the International African Institute by Dawsons of Pall Mall. [ Links ]

Downing, L.J. 2000. Satisfying minimality in Ndebele. ZAS Papers in Linguistics 19: 23-39. https://doi.org/10.21248/zaspil.19.2000.67 [ Links ]

Downing, L.J. 2001. Ungeneralizable minimality in Ndebele. Studies in African Linguistics 30(1): 33-58. [ Links ]

Downing, L.J. and A. Mtenje. 2011. Un-Wrap-ing prosodic phrasing in Chichewa. Lingua 121(13): 1965-1986. https://doi.org/10.1016/Uingua.2010.12.003 [ Links ]

Downing, L.J. and A. Mtenje. 2017. The phonology of Chichewa. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198724742.001.0001 [ Links ]

Du Plessis, J.A., N.E. Nxumalo and M.W. Visser. 1995. Tsonga syntax. Stellenbosch Communications in African Languages 2. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University. [ Links ]

Fortune, G. 1980. Shona grammatical constructions. Salisbury, Zimbabwe: Mercury Press.

Hyman, L.M. 2009. Penultimate lengthening in Bantu: Analysis and spread. UC Berkeley PhonLab Annual Report 5. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3q00m84d (Accessed 24 July 2021). https://doi.org/10.5070/p73q00m84d

Hyman, L.M. and J.T. Mathangwane. 1998. Tonal domains and depressor consonants in Ikalanga. In L.M. Hyman and C.W. Kisseberth (eds.) Theoretical aspects of Bantu tone. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications. pp. 195-230. https://doi.org/10.1017/s002222679925774x

Kanampiu, P.N. and P.K. Muriungi. 2019. Order of modifiers in Kïïtharaka determiner phrase. International Journal on Studies in English Language and Literature 7(6): 10-21. https://doi.org/10.20431/2347-3134.0706002 [ Links ]

Kanerva, J. 1990a. Focus and phrasing in Chichewa phonology. New York: Garland Press. [ Links ]

Kanerva, J. 1990b. Focusing on phonological phrases in Chichewa. In S. Inkelas and D. Zec (eds.) The phonology-syntax connection. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. pp. 145-161. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0952675700001536

Katamba, F. 2003. Bantu nominal morphology. In D. Nurse and G. Philippson (eds.) The Bantu languages. London: Routledge. pp. 103-120. [ Links ]

Kisseberth, C.W. 1994. On domains. In J. Cole and C.W. Kisseberth (eds.) Perspectives in phonology. Stanford, CA: CSLI. pp. 133-166.

Kraal, P. 2005. A Grammar of Makonde (Chinnima, Tanzania). Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Leiden. [ Links ]

Lee, S.J. and E. Selkirk. Forthcoming. A modular theory of the relation between syntactic and phonological constituency. In H. Kubozono, J. Ito and A. Mester (eds.) Prosody and prosodic interfaces. Oxford University Press.

Letsholo, R.M. 2006. The role of tone and morphology in the syntax of the Ikalanga DP. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 24: 291-309. https://doi.org/10.2989/16073610609486422 [ Links ]

Letsholo, R. and K. Matlhaku. 2014. The syntax of the Setswana noun phrase. Marang: Journal of Language and Literature 24: 22-41. [ Links ]

Mokoaleli, 'M. 2020. Sesotho Compounding. Unpublished Master's thesis, University of the Free State. [ Links ]

Mokoaleli, 'M., K. Riedel and M Furumoto. 2021. Sesotho (S33). In S.J. Lee, Y. Abe and D. Shinagawa (eds.) Descriptive materials of morphosyntactic microvariation in Bantu vol. 2: A microparametric survey of morphosyntactic microvariation in Southern Bantu languages. Tokyo: Institute for the Study of Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa. https://doi.org/710.15026/99969 [ Links ]

R Core Team. 2020. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (Accessed 24 July 2021). [ Links ]

Riedel, K. and S.J. Lee. 2021. Recursivity and focus in the prosody of Xitsonga DPs. (Submitted to Languages.)

Rolle, N. and L.M. Hyman. 2018. Phrase-level prosodic smothering in Makonde. UC Berkeley PhonLab Annual Report 14. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4w58812r. https://doi.org/10.5070/p7141042473

Rugemalira, J.M. 2007. The structure of the Bantu noun phrase. SOAS Working Papers in Linguistics 15: 135-148. [ Links ]

Selkirk, E. 2011. The syntax-phonology interface. In J. Goldsmith, J. Riggle and A. Yu (eds.) The handbook of phonological theory. Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 435-484. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444343069.ch14 [ Links ]

Tada, H. 2016. NP internal adjective order in Zulu. ICU Working Papers in Linguistics 1: 22-30. [ Links ]

Van Bulck, G. 1952. Les langues bantoues. In A. Meillet and M. Cohen (eds.) Les langues du monde. Paris: CNRS. pp. 847-903. [ Links ]

Van de Velde, M. 2019. Nominal morphology and syntax. In M. van de Velde, K. Bostoen, D. Nurse and G. Philippson (eds.) The Bantu languages. New York: Routledge. pp. 237-269. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315755946-8 [ Links ]

Van de Velde, M. 2020. Nominal Expressions in the Bantu Languages are Shaped by Apposition and Reintegration. Unpublished manuscript. https://doi.org/10.1515/tlr.2007.009

Zerbian, S. 2007. Phonological phrasing in Northern Sotho (Bantu). The Linguistic Review 24: 233-262. https://doi.org/10.1515/TLR.2007.009 [ Links ]

1 No systematic study reports word-level PL in Xitsonga. However, such lengthening has been reported for other Bantu languages, as noted below.

2 In Zulu, pre-nominal modifiers are relativised and morphologically marked with a so-called "relative prefix" (for discussion, cf. de Dreu 2008). This is not the case in Xitsonga, so the data might not be comparable across all Southern Bantu languages.

3 The Xitsonga data is transcribed in a modified version of the standard orthography where word boundaries have been adjusted to reflect phonological words accurately. Examples cited from the literature have been modified for consistent labels in glosses. High tones are marked with accent and length is marked with a colon. The following abbreviations are used in the glosses (numbers refer to noun class / person): aug = augment; ap = adjectival prefix; assoc = associative; dem = demonstrative; emp=emphatic; fut = future; om = object marker; pl = plural; pres = present tense; prf = perfective; pro = pronoun; poss = possessive; rel = relative marker; sg = singular; sm = subject marker; ! = downstep.

4 The brackets in (10) and (11) indicate phonological phrase boundaries, with bold face brackets marking the domains of high tones.

5 The pattern in Xitsonga is not as simple because all permutations of constituent orders in a DP are possible. A DP with two modifiers shows six possible word orders, and a DP with three modifiers, including a demonstrative, occurs in 24 different word orders. A detailed examination of these free word orders in Xitsonga DPs is beyond the scope of this paper, and we will defer an investigation to a future study.

6 The absence of PL in the sentence in (12) is due to the demonstrative not displaying PL in general.

7 A reviewer pointed out that the absence of PL in the FW in TSO047 may skew the results that we report here. When we ran a t-test on the second group, excluding speaker TSO047, we found that the exclusion did not have a discernible effect (t(119.52) = -2.66, p < 0.01).

8 As shown in (1) and (2), demonstratives never undergo PL for most speakers of Xitsonga. A reviewer raised a question whether grouping demonstratives and quantifiers into a single group skews the results reported in Figure 3. Confirming the reviewer's point, when demonstratives were grouped separately from the other modifiers, the PL duration of PW did not differ between marked and unmarked order (t(39.7) = 1.38, p = 0.18). However, this result from the demonstrative as a single group does not mean that quantifiers pattern together with numerals and adjectives. When quantifiers were grouped separately, the PL duration of PW also did not differ between marked and unmarked order (t(36.5) = -0.92, p = 0.36). Therefore, the grouping in Figure 3 holds.