Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus (SPiL Plus)

versão On-line ISSN 2224-3380

versão impressa ISSN 1726-541X

SPiL plus (Online) vol.62 Stellenbosch 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.5842/62-0-895

ARTICLES

When factivity meets the conjoint/disjoint alternation1

Lisa Lai-Shen Cheng

LUCL, Leiden University, The Netherlands. E-mail: l.l.cheng@hum.leidenuniv.nl

ABSTRACT

This paper examines the conjoint/disjoint alternation in matrix verbs which take clausal complements in Zulu. It shows that the typical verbs which by default take the disjoint form with a clausal complement are factive verbs, though it is also clear that other attitude verbs can undergo the conjoint/disjoint alternation as well. The paper explores the connection between focus and the conjoint/disjoint alternation in Zulu utilising the Question Under Discussion (QUD) approach. This will help to understand the interpretations associated with the alternations in combination with clausal complements.

Keywords: conjoint; disjoint; Zulu; Question Under Discussion; focus

1. Introduction

The conjoint/disjoint alternation is one of the hotly discussed topics in Bantu linguistics (see, e.g., the volume edited by Van der Wal and Hyman in 2016). The conjoint/disjoint alternation in Zulu is typically marked morphologically in two tenses: present tense affirmative and recent past affirmative. Recent works by Zeller, Zerbian and Cook (2016) and by Halpert (2016) also look into the prosodic side of the alternation in Zulu. As summarised by Zeller et al. (2016), the distinction in Zulu is generally analysed as a reflex of syntactic constituency: the conjoint form indicates that the verb is followed by material inside vP, while the disjoint form indicates that the verb is vP-final.

The discussion so far mainly concerns verbs and their nominal arguments as well as adjuncts which follow the verb (and verbal arguments). Crucially, as mentioned in the introduction chapter of Van der Wal and Hyman (2016), as well as in Van der Wal (2016), one of the questions related to the conjoint/disjoint alternation concerns the information structure of the alternation. In particular, it is often mentioned that when the verb is in the disjoint form in Zulu, it is the verb that is focused. When it comes to conjoint/disjoint alternation followed by a clause, there are only a few papers, which mainly discuss the type of subordinate clauses and how they relate to the conjoint/disjoint alternation (see Van der Wal 2016 and the works cited therein). Halpert (2012) discusses complement clauses in Zulu in connection with the conjoint/disjoint alternation and, in particular, complement clauses introduced by different complementizers. This paper hopes to contribute further to this discussion, in particular, the interpretation of the conjoint vs. disjoint marking followed by a complement clause.

In section 2, after a brief overview of the basics of the conjoint/disjoint alternation in Zulu, I turn to the core data in this paper, i.e., sentences with complement clauses with conjoint or disjoint forms. Section 3 discusses the possible distinction, i.e., factivity, that yields the conjoint or the disjoint form with verbs that take complement clauses. I also briefly discuss problems associated with a lexical view of factivity. Section 4 provides an analysis, using the Question Under Discussion (QUD) approach. I discuss how an analysis using the focus-sensitive QUD approach (following Simons, Beaver, Roberts and Tonhauser 2017, and Beaver, Roberts, Simons and Tonhauser 2017) can help us tie together the conjoint/disjoint alternation and focus reading even in the case of Zulu (leaving the trigger of conjoint/disjoint alternation associated with constituency intact).

2. Overview of the conjoint/disjoint alternation in Zulu

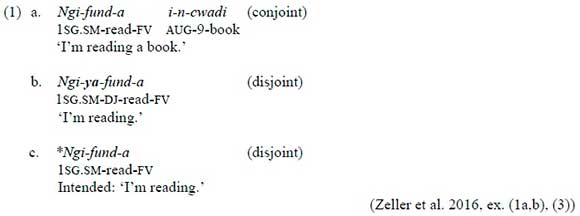

In this paper, I concentrate on the conjoint/disjoint alternation in the present tense affirmative. Example (1) illustrates the basic morphological distinctions in the case of the disjoint form, where the morphemeya appears before the verb stem (as in (1b)), while the conjoint form does not have any overt marking in the present tense (1a).

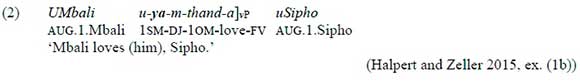

The conjoint verb form in (1a) is followed by a direct object, whereas the disjoint form is needed when the verb is the only element in the vP (compare (1b) and (1c)). Previous research by Van der Spuy (1993) and Buell (2006), among others, has shown that if the object following the verb is dislocated (i.e., with an object marker on the verb agreeing with the dislocated object), the object is outside of the vP, leading to the disjoint form on the verb, as in (2).

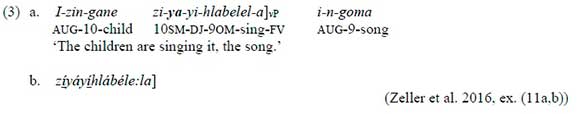

In (2), the object marker m agrees with uSipho 'Sipho' in noun class. The corroborating prosodic evidence for the vP-final status of the verb in (2), as well as the dislocated status of the object uSipho, is the fact that the penultimate vowel of the verb in sentences like (2) must be lengthened (see Cheng and Downing 2007, 2009 for identifying the right edge of the vP-phase as one of the syntactic edges which aligns with an Intonational Phrase). Zeller et al. (2016) also discuss a second piece of prosodic correlate of the disjoint form: high-tone spread. (3b) illustrates both H-tone spread and penultimate lengthening.2

What (3a,b) illustrate is that H-tone spread in the case of disjoint forms spreads (from the object marker in (3)) only to the antepenult instead of the penult (as in cases of conjoint forms). We furthermore see that the penult is lengthened.

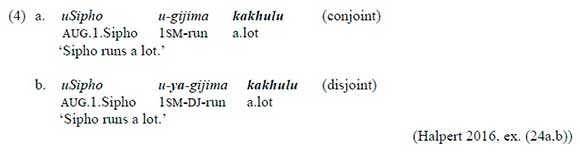

The above view connects the conjoint/disjoint alternation with vP-constituency. It should be noted that discussions concerning the conjoint/disjoint alternation are often also related to focus (see Van der Wal and Hyman 2016 for a cross-Bantu discussion). For Zulu, Halpert (2016) supports Buell's (2006) view that the correlation between conjoint/disjoint alternation and focus is a side effect of syntactic structure: material inside the vP can be focused, while right-dislocated elements belong to old information. Halpert (2016) shows that with adjuncts such as kakhulu 'a lot', either the conjoint or the disjoint form can be used, though with the conjoint form (4a), the adverb tends to be interpreted as focused or as new information, while with the disjoint form (4b), the adverb tends to be interpreted as old information.

We will come back to the connection between conjoint/disjoint alternation and focus below.

2.1 Clausal arguments and conjoint/disjoint alternation

As already mentioned above, the discussions of conjoint/disjoint alternation in Zulu have mainly concentrated on cases where the verb is followed by its nominal argument(s) as well as cases involving adjuncts. Halpert (2012) is one of the very few exceptions. Below, I first present a brief overview of her discussion before introducing extra data.

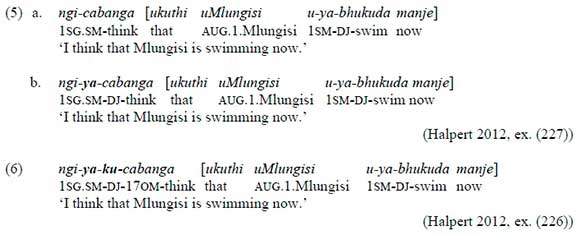

Halpert (2012) shows that both the conjoint and disjoint forms are possible with clausal complements, as we see in (5) with the verb ukucabanga 'to think'. She also shows that in the case of the disjoint form, the addition of the object marker ku (class 17) is possible, as in (6) (cf. (5b) which does not have ku).3

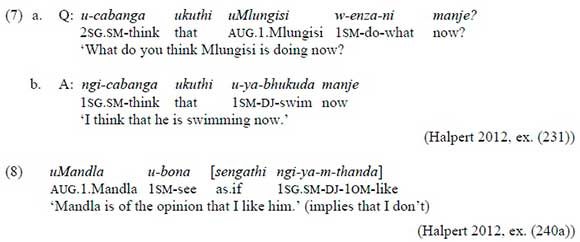

Halpert notes that in out-of-the-blue contexts, speakers do not show systematic preference for either the conjoint or disjoint form (i.e., (5a) and (5b) are equally acceptable). She further notes that there are two scenarios where the conjoint form is preferred or required: (i) when part of the contents of the complement clause is focused, the conjoint form is preferred (7b); and (ii) when the complementizer sengathi 'as if is used, the conjoint form is required (8). For the scenario with sengathi, see Halpert (2012) for a detailed discussion.

Given the context in (7a), the embedded uyabukuda 'he is swimming' in (7b) is focused, and the matrix conjoint verb form is preferred. In contrast, if the matrix verb itself is focused, the disjoint form is preferred. Compare (9a,b) with (7a,b).

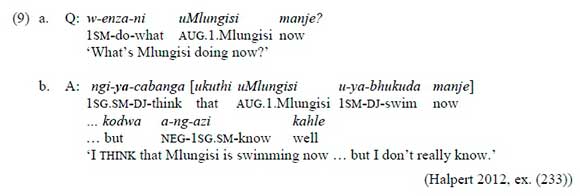

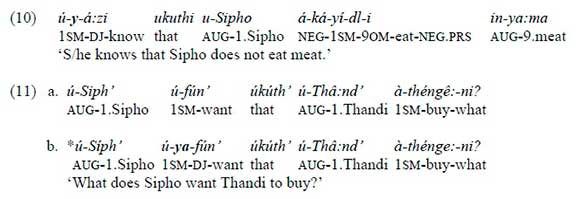

The data from our elicitations largely confirm the observations in Halpert (2012).4 In particular, for matrix verbs such as ukucabanga 'to think' and ukukholwa 'to believe', both the conjoint and the disjoint forms can be used, and it is not clear whether there is any interpretational difference. Nonetheless, there is one more scenario where the disjoint form has to be used (e.g., (10)), as well as another scenario where the conjoint form is required (11).

Based on previous work concerning the conjoint/disjoint alternation, the null hypothesis is that regardless of whether we are dealing with nominal arguments or clausal arguments, the conjoint form indicates that the verb is not vP-final, while the disjoint form means that it is. Extending the hypothesis more concretely to the case of complement clauses of verbs, the presence of the object marker ku requires a disjoint form, suggesting that the complement clause is also outside of the vP. Though the object marker is optional, we can still conclude that the complement clause is outside of the vP when the disjoint form is used (as the object marker can be null). That is, the complement clause is extraposed out of the vP. In other words, the constituency analysis of the conjoint/disjoint alternation also holds in the case of complement clauses.

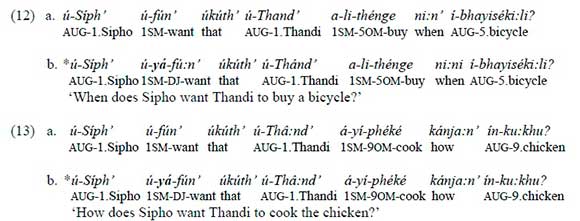

Let us now turn to the cases with the preferred/required conjoint forms in (7) and (11). These cases are the same in nature. For (7b), Halpert (2012) concludes that it has to do with focused material in the embedded clause. In (11a,b), we are dealing with complement clauses containing a wh-phrase. It should be noted that what we see in (11) can be replicated with other wh-phrases, such as nini 'when' and kanjani 'how', as in (12) and (13).

The question is whether the preferred/required conjoint forms in (7b) and (11)-(13) can be explained by the constituency analysis. First, we should note that the cases mentioned in (11)-(13) involve subjunctive clauses, and extraction out of subjunctive clauses is possible in principle. We know this because, firstly, all the (a)-sentences in (11)-(13) also involve a wh-phrase, which can also be thought of as being focused. The only difference between the (a)-sentences and the (b)-sentences in (11)-(13) is the difference in the conjoint/disjoint form. Secondly, Halpert and Zeller (2015) show that raising-to-object can take place out of a subjunctive clause.

If the disjoint matrix verb form in (11b)-(13b) indicates that the matrix verb is vP-final, the complement clause can be analysed as being extraposed out of the vP and adjoined to the main clause. The complement clause is thus an adjoined clause constituting an adjunct island. Any subsequent wh-movement, albeit covert (as in the case of in situ wh-phrases), would involve extraction out of an adjunct island, leading to ungrammaticality. This can explain why the disjoint form is not possible when we have wh-phrases. This analysis can be extended to focused items, which are hypothesized to undergo covert movement as well (to a focus projection higher up). Note that Halpert and Zeller (2015) also show that raising-to-object can happen before extraposition of the CP complement. However, in the case of wh-phrases, since they are in situ in overt syntax, any movement that takes place needs to do so after extraposition has taken place.

Though this analysis can successfully account for cases with a wh-phrase/focus in the embedded clause (e.g., (7b) and (11b)-(13b)), it does not directly tell us why (10) needs to be in the disjoint form, and whether there is any interpretational difference between (5a) and (5b).

3. Factivity and extraposition

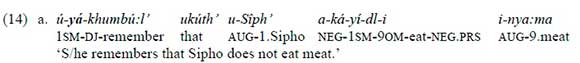

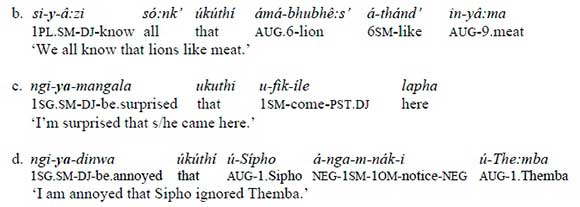

The most clear-cut cases with the disj oint form only or with a very marginal conj oint form are cases involving verbs such as ukukhumbula 'to remember', ukukhohlwa 'to forget', ukuazi 'to know', ukumangala 'to be surprised', and ukudinwa 'to be annoyed'. (14a-d) are some illustrations.

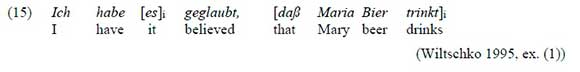

These verbs belong to the class of factive predicates, and the clausal arguments they take are interpreted as presupposed (see Kiparsky and Kiparsky 1971). As discussed in the previous section, a likely analysis of the disjoint form and the interpretation of the sentences in (14) is as follows. First, these clausal complements of factive verbs are extraposed or dislocated. According to Wiltschko (1995), the complement clause in German dislocated clauses such as (15) is interpreted as presupposed because it is associated with a nominal argument (see Wiltschko's paper for details).

Following Wiltschko, we can posit a null pronoun in the matrix clause of the sentences in (14) (on a par with cases where the disjoint form is used with the object marker ku), leading to a presupposed reading of the complement clauses in (14).5

It should be noted that this analysis of the sentences in (14) implies that factive verbs in particular are obligatorily associated with the presence of a null pronoun in Zulu, leading to dislocation and a presupposed reading of the complement clauses. As for verbs that can optionally take a disjoint form, it implies that the presence of a null pronoun is optional. Regardless of whether we adopt Wiltschko's analysis of the presupposed reading, it is important to see that this essentially adopts a lexical view, i.e., it is the nature of the verbs that yields the results that we see.

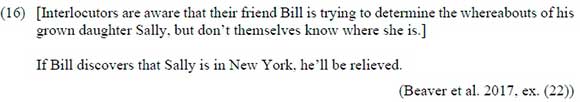

Recent works by Simons et al. (2017) and Beaver et al. (2017) call into question the lexical view of Kiparsky and Kiparsky (1971), among others, which is based on the lexical nature of the verb (e.g., factive). Simons et al. (2017) show that the context of an utterance can in fact yield a non-projective reading; that is, the content of the complement clause cannot be understood as implied or presupposed. Consider the context and the utterance in (16) (see also Chierchia and McConnell-Ginet 1990: 354).

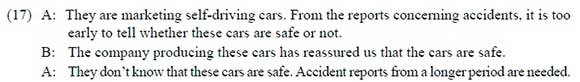

Discover is a factive predicate. However, in (16), given the context, the speaker does not commit to the complement clause (Sally is in New York). In other words, in (16), the clausal argument of discover is not presupposed, despite the fact that discover is a factive verb. Beaver et al. (2017) and Simons et al. (2017) further indicate that a change of narrow focus in factive sentences can change the presupposed content (I will return to this in section 4). Another case in which non-projection can be shown is with negation. For example, in (17), the second utterance of speaker A involving know is non-projective.6

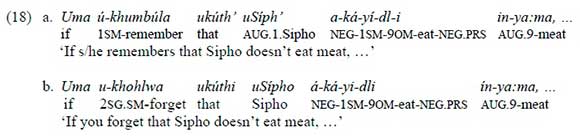

Turning to factive verbs in Zulu, the most straightforward way to test non-projective readings à la Beaver et al. (2017) is to use conditionals (as in (16)) and negation (17). Unfortunately, Zulu conditionals involve participial mood, which does not show conjoint/disjoint alternations, as in (18).7

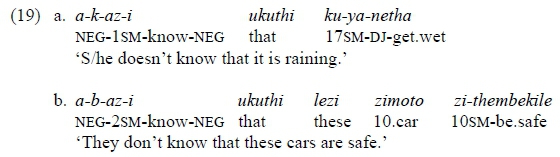

Similarly, negation also does not show the conjoint/disjoint alternation,8 as we see in (19), where (19b) is presented with the context in (17).

Despite the fact that neither conditionals nor negative sentences can inform us further concerning the conjoint/disjoint alternation in Zulu, following Simons et al. (2017) and Beaver et al. (2017), it is still worthwhile to consider an alternative to a lexical analysis, especially due to the fact that for some verbs, the conjoint/disjoint alternation does not seem to be connected to clear-cut interpretational differences or lexical properties. In the next section, I suggest an alternative analysis of the conjoint/disjoint alternation in light of the interaction between QUD and focus.

4. Focus, QUD, and conjoint/disjoint alternations

In this section, I lay out my analysis of the conjoint/disjoint alternation in relation to complement clauses. My analysis, based on Beaver et al. (2017) and Simons et al. (2017), entertains a close relation between focus and the QUD model. As mentioned in section 2, focus is considered to be a side effect of the conjoint/disjoint alternation. To understand how this side effect occurs, as well as how this connects to factive verbs and the conjoint/disjoint alternation, I first briefly provide background information concerning focus in Zulu.

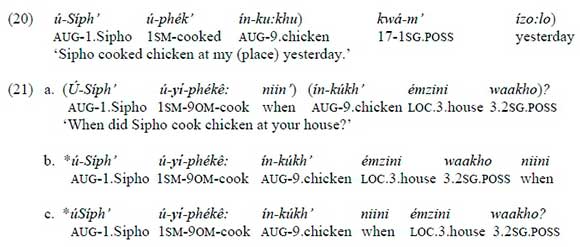

First, to recapitulate what we have mentioned so far about the conjoint/disjoint alternation: vP-constituency in Zulu is the main factor for determining conjoint/disjoint form. If a verb is vP-final, it is in the disjoint form; otherwise, it is in the conjoint form. Nonetheless, it is clear that there are some focus-related effects. This is not surprising, as the position immediately following the verb (the so-called "IAV position") is the typical focus position (see Buell 2005, 2009 and Cheng and Downing 2012, among others). For example, though non-w/z-adjuncts follow direct objects canonically (20), w/z-phrases such as nini 'when' in (21) must appear in the IAV position.

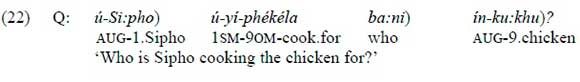

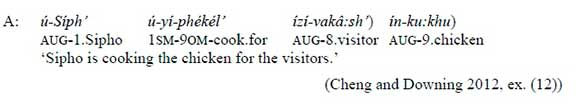

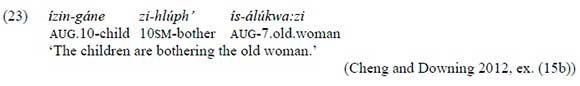

The sentences in (21a-c) illustrate the IAV effect of w/ -phrases; (21b,c) are ungrammatical because the w/z-phrase nini 'when' does not appear immediately after the verb. Cheng and Downing (2012) show that even when w/ -phrases or their corresponding answers appear in the canonical IAV position (e.g., as in the case of indirect objects in (22)), the direct object following the w/z-phrase or the focused phrase must be dislocated (and resumed with an object marker).

Nonetheless, if there is only a single argument in the verb phrase, as in (23), the object is optionally interpreted as focused. This is similar to the data presented above in (4a) (cited from Halpert 2016) concerning the adjunct which follows a conjoint verb. In both of these cases, the verb is in conjoint form, and there is one single element following the verb.

Furthermore, as (4b) above shows, when the verb is in disjoint form, the adjunct following the verb tends to be interpreted as old information, with the verb interpreted as focused. The sentences in (2) and (3) illustrate the same pattern: the verb is in disjoint form and the direct object is dislocated and interpreted as given information; the disjoint verb can be interpreted as being focused.

The fact that the disjoint verb can be interpreted as focused is not a surprise. Following Cheng and Downing (2012), the vP-final verb is the only element in the vP, and thus the only one that can have prosodic prominence in the vP. Let us now turn to the QUD model and the interaction between QUD and focus, before we turn back to the Zulu conjoint/disjoint form.

4.1 QUD and focus

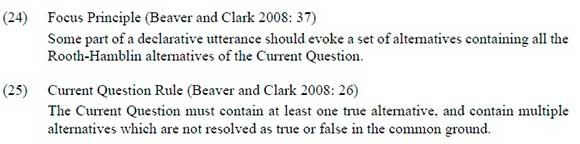

Beaver et al. (2017: 266) summarise the QUD model as follows: "QUD models characterize semantic and pragmatic phenomena in terms of the strategy of inquiry that discourse participants follow [...]". A strategy of inquiry consists of a sequence of questions. This can be easily combined with alternative semantics (Rooth 1985, 1992) connected to information structure, specifically using Beaver and Clark's (2008) Focus Principle (24) and the Current Question Rule (25).

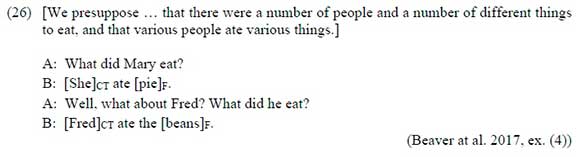

One of the examples that the authors use to illustrate this is (26), where CT stands for "contrastive topic" and F for "focus".

The questions asked by A form part of a strategy for achieving a larger discourse goal. In particular, given the questions asked by A, we can derive an implicit question: who ate what? In other words, the questions asked by A form a strategy of inquiry, with the Current Question consisting of a contrastive topic which in turn provides a partial answer to the implicit question.

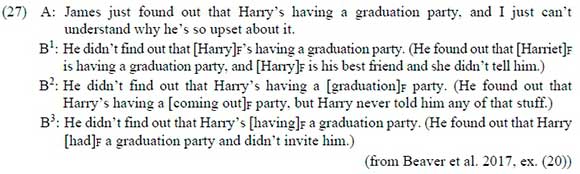

Beaver et al. (2017) argue that focus is linked to QUD because it has a discourse function and because focus is sensitive to context. They further connect factivity to focus and QUD (see also Simons et al. 2017). Consider the utterances of A and B in (27).

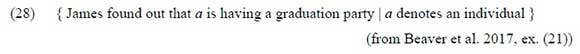

What I would like to zoom in on is the contrast between B1 and B3. On the basis of the Focus Principle, the focus meaning of B1 is as in (28).9

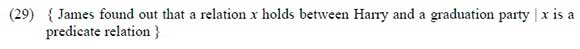

Harry is focused in B1 and, based on Rooth's alternative semantics as well as the Current Question Rule, the set in (28) must have at least one true alternative. That is, there must be at least one individual such that James found out that s/he is having a graduation party. Consider now B3, which is very relevant to the conjoint/disjoint alternation discussion. The focus meaning of B3 would be (29).

Again, based on the Current Question Rule, the set involved must have at least one true alternative. That is, there must be at least one kind of predicate relation (e.g., is having, had, is giving, gave) that is true between Harry and the graduation party, making Harry and the graduation party given (presupposed) information. Based on the above, it is clear that with focus and QUD, we can see that what is presupposed under factive verbs does not stay constant; that is, it can vary based on what is being focused.

4.2 Back to conjoint/disjoint in Zulu

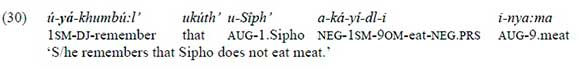

What I set out to do is to figure out the interpretation connected to the conjoint/disjoint alternation and the clausal arguments in Zulu, and the role focus plays in the interpretational differences. In this section, we first turn back to the examples with the factive verbs in Zulu. Consider again the sentence in (14a), repeated here as (30).

The sentence in (30) is one of the cases where the disjoint form is obligatory and the content of the embedded clause is interpreted as presupposed, conforming to the interpretation of factive verbs. The question we need to address is why such a presuppositional reading arises if it is not the lexical properties of factive verbs that are to blame.

Let us now consider (30) in light of the QUD approach discussed in the previous section. In particular, in cases such as (30), it is often mentioned that the verb is "somehow" interpreted as being emphasized or focused (see Halpert 2012 and the discussion above). Under such an interpretation, (30) would have the focus meaning in (31).

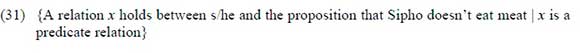

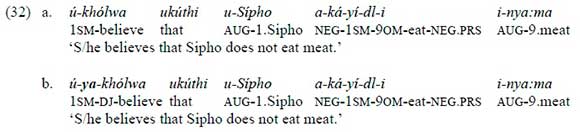

The reasoning above allows us to understand that the conjoint/disjoint alternations in sentences with ukacabanga 'to think', as in (5a,b), or with ukukholwa 'to believe', as in (32a,b), are very difficult to tear apart.

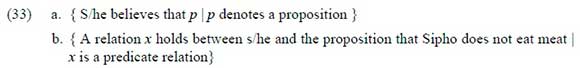

Consider the focus meanings of (32a) and (32b) in (33a) and (33b), respectively.

For (32b/33b), we get the reading that the proposition that Sipho does not eat meat is presupposed, similar to what we see in (30) and (31). I suggest that (32a) has the reading in (33a) because the complement clause can be interpreted as focused. In other words, the sentence means that there is a proposition that s/he believes, out of a list of alternatives, and the proposition that Sipho does not eat meat may be the true alternative. The distinctions between (33a) and (33b) are thus very difficult to distinguish, since the proposition that Sipho does not eat meat can indeed be the true alternation amongst all the alternatives.

If the above reasoning concerning the interpretations is on the right track, the question that remains is why factive verbs tend to take the disjoint form by default, as in the cases in (14). Following Simons et al. (2017), who note that verbs like know are veridical, which is still different from a verb like think, I suggest that by being veridical, factive verbs are by default only compatible with a complement clause which is by default interpreted as presupposed. This distinguishes factives from non-factive verbs.

5. Conclusion

The conjoint/disjoint alternation in Zulu has been shown in previous literature to be based on constituency, with focus as a side effect. In this paper, I discussed the conjoint/disjoint alternation when the matrix verb is followed by a complement clause. I showed that there is a basic distinction between factive and non-factive verbs. This paper showed that although focus has been considered to be a side effect, it nonetheless plays a role in the interpretation of clausal complements, depending on the conjoint or disjoint verb form. If the proposal in this paper in on the right track, we need to test more contexts, which may distinguish the conjoint from the disjoint forms with attitude verbs which are not factive.

References

Beaver, D.I. and B.Z. Clark. 2008. Sense and sensitivity: How focus determines meaning. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell. [ Links ]

Beaver, D.I., C. Roberts, M. Simons and J. Tonhauser. 2017. Questions Under Discussion: Where information structure meets projective content. Annual Review of Linguistics 3: 265-284. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-linguistics-011516-033952. [ Links ]

Bresnan, J. and S.A. Mchombo. 1987. Topic, pronoun, and agreement in Chichewa. Language 63(4): 741-782. https://doi.org/10.2307/415717. [ Links ]

Buell, L. 2005. Issues in Zulu Verbal Morphosyntax. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles. [ Links ]

Buell, L. 2006. The Zulu conjoint/disjoint verb alternation: Focus or constituency? ZAS Papers in Linguistics 43: 9-30. https://doi.org/10.21248/zaspil.43.2006.283 [ Links ]

Buell, L. 2009. Evaluating the immediate postverbal position as a focus position in Zulu. In M. Matondo, F. McLaughlin and E. Potsdam (eds.) Selected proceedings of the 38th Annual Conference on African Linguistics: Linguistic theory and African language documentation. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press. pp. 166-172.

Buell, L. 2011. Zulu ngani 'why': Postverbal and yet in CP. Lingua 121(5): 805-821. https://doi.org/10.1016/Uingua.2010.11.004. [ Links ]

Cheng, L.L. and L.J. Downing. 2007. The prosody and syntax of relative clauses in Zulu. SOAS Working Papers in Linguistics 15: 51-63. [ Links ]

Cheng, L.L. and L.J. Downing. 2009. Where is the topic in Zulu? The Linguistic Review 26(2-3): 207-238. https://doi.org/10.1515/tlir.2009.008. [ Links ]

Cheng, L.L. and L.J. Downing. 2012. Against FocusP: Arguments from Zulu. In I. Kucerova and A. Neeleman (eds.) Contrasts and positions in information structure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 247-266. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511740084.012 [ Links ]

Chierchia, G. and S. McConnell-Ginet. 1990. Meaning and grammar. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Halpert, C. 2012. Argument Licensing and Agreement in Zulu. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. [ Links ]

Halpert, C. 2016. Prosody/syntax mismatches in the Zulu conjoint/disjoint alternation. In J. van der Wal and L.M. Hyman (eds.) The conjoint/disjoint alternation in Bantu. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. pp. 329-349. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110490831-012. [ Links ]

Halpert, C. and J. Zeller. 2015. Right dislocation and raising-to-object in Zulu. The Linguistic Review 32: 475-513. https://doi.org/10.1515/tlr-2014-0029. [ Links ]

Kiparsky, P. and C. Kiparsky. 1971. Fact. In D.D. Steinberg and L.A. Jakobovit (eds.) Semantics: An interdisciplinary reader in philosophy, linguistics and psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 345-369. [ Links ]

Poulos, G. and C.T. Msimang. 1998. A linguistic analysis of Zulu. Cape Town: Via Afrika. [ Links ]

Riedel, K. 2009. The Syntax of Object Marking in Sambaa: A Comparative Bantu Perspective. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Leiden. [ Links ]

Rooth, M. 1985. Association with Focus. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Massachusetts at Amherst, MA. [ Links ]

Rooth, M. 1992. A theory of focus interpretation. Natural Language Semantics 1: 75-116. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02342617. [ Links ]

Simons, M., D. Beaver, C. Roberts and J. Tonhauser. 2017. The best question: Explaining the projection behavior of factives. Discourse Processes 54(3): 187-206. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2016.1150660. [ Links ]

Van der Spuy, A. 1993. Dislocated noun phrases in Nguni. Lingua 90(4): 335-355. https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-3841(93)90031-q [ Links ]

Van der Wal, J. 2016. What is the conjoint/disjoint alternation? Parameters of crosslinguistic variation. In J. van der Wal and L.M. Hyman (eds.) T/e conjoint/disjoint alternation in Bantu. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. pp. 14-60. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110490831-002. [ Links ]

Van der Wal, J. and L.M. Hyman (eds.) 2016. T/e conjoint/disjoint alternation in Bantu. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110490831. [ Links ]

Wiltschko, M. 1995. Presuppositions in German dislocation constructions. Folia Linguistica 29(3-4): 265-295. https://doi.org/10.1515/flin.1995.29.3-4.265. [ Links ]

Zeller, J., S. Zerbian and T. Cook. 2016. Prosodic evidence for syntactic phrasing in Zulu. In J. van der Wal and L.M. Hyman (eds.) T/e conjoint/disjoint alternation in Bantu. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. pp. 295-328. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110490831-011. [ Links ]

1 The baseline data of this paper were gathered together with Laura Downing on different occasions when Laura was in Leiden. She is therefore also a co-author of the paper but, because of the nature of the volume, I cannot consult her regarding my hypotheses or conclusions. I am grateful to our Zulu consultant, Meritta Xaba, who helped us tremendously with the elicitations, as well as answering my recent questions. I also thank Blessing Mangwanda for discussing the data with me. I thank Leston Buell and Merijn Dreu for their help with the paper. Lastly, I am very grateful to Laura for being such a great and reliable co-author throughout our years of collaboration.

2 See Zeller et al. (2016), among others, for discussions concerning H-tone spread involving a H-tone on prefixes spreading to a toneless verb in Zulu.

3 Halpert (2012) also shows that if ku is present, the disjoint form has to be used, while with subjunctive clauses, ku is only possible if the complementizer ukuthi is present.

4 Most of the data involving clausal arguments are from elicitation sessions that Laura Downing and I conducted in 2008 and 2010. It should be noted that the vowel lengths are not consistently indicated and have not been double-checked.

5 The question we can posit here is of course whether the null pronoun is a null object marker, on a par with the overt object marker ku. Whether or not subject/object markers are pronouns or agreement marking has been a long debated issue in Bantu linguistics. See Bresnan and Mchombo (1987) and, more recently, Riedel (2009) for relevant discussions.

6 (17) models after the utterances in Beaver et al. (2017, ex. (18)).

7 The present tense participial mood form in the positive is the same as the principal counterpart. In other words, it is the same as the conjoint form.

8 Buell (2011) reports on the negative perfect tense, which shows the alternation (with -e/-ile alternation). Poulos and Msimang (1998) note that the -ile form is only possible for inchoative roots. Nonetheless, factive verbs are all stative. Thus, they do not show the alternation.

9 See Beaver et al. (2017) and Simons et al. (2017) for details concerning the interaction between negation and factivity, as well as the focus meaning in (28).