Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus (SPiL Plus)

versão On-line ISSN 2224-3380

versão impressa ISSN 1726-541X

SPiL plus (Online) vol.61 Stellenbosch 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.5842/61-0-921

ARTICLES

Interpreter training: Devising a model for aptitude testing for simultaneous interpreters

Simoné GambrellI; Harold M. LeschII

IDepartment of Afrikaans and Dutch, Stellenbosch University, South Africa E-mail: simone.gambrell@yahoo.com

IIDepartment of Afrikaans and Dutch, Stellenbosch University, South Africa E-mail: hlesch@sunac.za

ABSTRACT

The proper selection and training of simultaneous interpreting candidates would ensure that they meet all essential requirements and are fully prepared to face any professional assignment they might encounter. Aptitude tests for entrance to training courses may be a step on the path to improving interpreting quality and strengthening the professionalisation of the field. As a result, this study aimed to design a comprehensive, custom-made aptitude test for simultaneous interpreting relevant for the South African context. A further aim for this test was for it to be used in practice to differentiate between those students who have the ability to succeed as interpreters and those who do not, in order to ultimately improve the quality of the professional field of interpreting.

This aim was accomplished through a qualitative research design. First, a review was conducted on the available literature on interpreter aptitude testing. Further analysis showed that only eight of these tests had been proven to reliably predict aptitude for interpreting. Second, online surveys and in-person, semi-structured interviews were utilised to gather the opinions of interpreter trainers and potential interpreting students. The trainers were asked, among other questions, which cognitive and personality traits they would wish to test for in prospective students. The students were also asked, among other questions, to rate on a Likert scale their confidence in successfully completing the different available aptitude tests.

Through this data, it was found that there is a need for aptitude testing for the training of simultaneous interpreting students in South Africa, and that both trainers and students advocated for its use. Moreover, it was possible to determine the most effective aptitude tests from among those that are available and, furthermore, those that would be easy to administer and complete.

Keywords: aptitude test; screening students; training; language ability; introductory course

1. Introduction

According to Corsellis (1999: 197-198), trust in a profession has to be earned before it, or any associated status, can be obtained. Therefore, to meet the standards of expertise required of a profession, all potential members should undergo a process of selection, training, and objective assessment. An aptitude test is a predictor or forecaster (Russo 2011: 6) and can be used to distinguish between those applicants who are deemed to have the potential to become interpreters and those who are not.

Due to the complex mental processes of interpreting1, students should be recruited at a higher level. Keiser (1978: 13) notes that learning interpreting skills requires maturity and a certain level of previous training. Students should also have a sufficient level of mastery over their active and passive languages in order to avoid pressure caused by stumbling in an interpreting programme that focuses on skills and not language learning. Thus, by separating interpreting from language learning and linguistics, it is possible to define the relevant abilities and standards for the interpreting profession (Donovan 2006: 79). This can also be achieved by organising selection criteria in order to ensure that students are fully prepared to face any professional assignment (Keiser 1978: 11).

While it is normal to be highly selective when it comes to admitting students into a course, this has previously not been the case in interpreting (Donovan 2006: 73). However, present and developing market trends have ensured that employers have a wider field from which to choose only the best, and so it would be irresponsible, according to Keiser (1978: 12, 14), to allow large numbers of students to enrol, raising their hopes for future careers, when they may not pass their studies or be hired.

The interpreting profession within the South African context is very unstable, as depicted by Pienaar and Cornelius (2015) with reference to happenings during high profile interpreting events. By the turn of the century, "it was clear that the quality of interpreting services was poor or completely lacking in public domains such as courts, the police service, state hospitals and state pharmacies" (Pienaar and Cornelius 2015: 187). The impact of the lack of interpreting services or the use of untrained interpreters in various settings was evident, which "adversely affected the quality of services provided by institutional service providers" (Pienaar and Cornelius 2015: 187). However, interpreter training has improved substantially in the country in the recent past.

The rest of the article is set out as follows: (i) the rationale for the study is stated in sections 1.1 and 1.2; (ii) a literature review is provided in section 2; (iii) the empirical study together with the discussion of the results follows in sections 3 to 6; and (iv) a custom-made aptitude test is proposed in section 7.

1.1 Research problem

Limited research on aptitude testing is available and while the Antwerp symposium back in 2009 already addressed this concern, leading to a boom in publications during the 2010s, this success seems to have waned in the recent past. Moreover, very little research has been done on a model of aptitude testing informed at the local level (i.e. not using the universal ideal). This study will therefore investigate the nature of aptitude test(s) for interpreting. The presence or absence of such a test will be investigated in the South African tertiary institutions which offer interpreting training. Furthermore, we will explore the possibility of devising a model for a comprehensive aptitude test for interpreting, to be offered by training institutions to students applying for a programme in interpreting.

1.2 Objective of the article

The main research question for this article is as follows:

• What should a custom-made aptitude test for simultaneous interpreting in South Africa encompass?

The secondary research questions for this article are as follows:

• Which aptitude test components can best be used to effectively screen applicants for interpreting training, as determined through the literature review?

• Which existing aptitude test(s) is suitable for the South African context, that does not limit one's ability to perform due to unfamiliarity with the test(s)?

• How can the number2 of test activities assessing the various skills and personality traits be optimised?

2. Literature review

The literature review investigates the opinions and insights of previous researchers in the field of aptitude testing for interpreting. Existing aptitude tests, which have been tried and tested for validity, also come into play.

2.1 Generally accepted qualities of interpreters

Interpreting is generally considered to be a highly complex cognitive processing task which requires components of listening, comprehending, communication planning, and language production, usually happening simultaneously in two different languages. Interpreting also includes analysing the speaker's goals, inferences, and subtleties while simultaneously deciding how to convey the speaker's meaning into a second language and culture (Macnamara, Moore, Kegl and Conway 2011: 121-1223). During interpreting, the interpreter needs to listen to the incoming message, store the information in his/her short-term memory, manage the interpreting process and its demands, and then analyse, reason, and make decisions based on that analysis as well as the interpreter's own abilities.

Therefore, the task of interpreting not only encompasses linguistic tasks, but also general cognitive abilities across working memory capacity and reasoning ability. These abilities are assumed by psychological researchers to be innate qualities that present in early development and remain relatively stable over time (Macnamara et al. 2011: 122). As a result, these qualities are generally considered to be prerequisites for those individuals who want to apply for interpreter training (hereafter referred to as "candidates"). The role of cognitive skills has been foregrounded in the study of aptitude testing (Shlesinger and Pöchhacker 2011: 3), and the first framework for candidate prerequisites, as inspired by professional and training experience and intuition, has remained largely unchanged as a frame of reference (Russo 2011: 9, 24).

However, the question of linguistic tasks and language proficiency is of utmost importance in the interpreting act, and many researchers agree that general language proficiency is a prerequisite to any interpreting course (Garzone 2002 and Kurz 1993). It is a basic tenet that language acquisition cannot form part of interpreter training but must precede it, which therefore makes the degree of language competence a vital criterion. In order to succeed as a trainee or in the interpreting profession, researchers agree that a candidate must have a profound knowledge of their language combinations as well as the ability to rapidly grasp meaning in one language and then convey the essential meaning in another. The candidate must have the ability to project information with confidence and possess a good voice with the ability to express oneself with clarity and conviction. Finally, the candidate must be able to reproduce and convey the source message in a cohesive and coherent manner, reconstructing the semantic structure in the target language (Campbell and Hale 2003: 212, Corsellis 1999: 199, Pöchhacker 2004: 180, Russo 1989: 57, Russo and Pippa 2004: 410).

Along with a profound knowledge of languages, a wide general knowledge and range of interests, coupled with a willingness and skill to acquire new information, is essential. A broad understanding of the general cultures involved is usually added to this category, as understanding the culture attached to the language assists interpreters in reproducing the meaning of the source message so that the target audience will fully understand the translation. This general knowledge usually lends itself to a university-level or professional experience, and includes the major fields of daily human interest, such as politics, economics, and culture. As a result, a broad general knowledge assists an interpreter with comprehension of the source message as well as self-expression, and ascertains that the interpreter has an open mind, intellectual curiosity, and is flexible with strong powers of deduction (Campbell and Hale 2003: 212, Corsellis 1999: 202, Pöchhacker 2004: 180, Russo 2014: 2, Russo and Pippa 2004: 410).

Also considered among the necessary cognitive skills for interpreting is a good working memory, particularly short-term memory, as it allows interpreters to capitalise on intertextuality within, for example, a conference setting. An interpreter's powers of concentration need to be high in order to make optimal use of working memory and anticipation strategies (Campbell and Hale 2003: 212; Rosiers, Eyckmans and Bauwens 2011: 54; Russo 2014: 2). An excellent long-term memory is also required for storage of terminology, vocabulary, factual information, and interpreting strategies (Marais 1999: 307).

Despite this almost exclusive focus on cognitive traits, the role of personality traits in a composite profile of potential interpreting candidates did gain importance. However, there are very few personality aptitude tests used for interpreting training (Russo 2011: 12-13, Shlesinger and Pöchhacker 2011: 2). In general, the kinds of personality traits considered to be essential for the "ideal" interpreter include the ability to work in a team, as well as high levels of stress tolerance and physical and psychological stamina (Campbell and Hale 2003: 212; Gerver, Longley, Long and Lambert 1989: 724; Pöchhacker 2004: 180; Russo 2014: 2; Russo and Pippa 2004: 410).

Other personality traits, or "soft skills", include a code of ethics, a faculty of analysis, the ability to adapt to the subject matter, tact and diplomacy, good nerves, a positive attitude, motivation, emotional stability, and linguistic self-confidence (Corsellis 1999: 202, Keiser 1978: 17, Rosiers et al. 2011: 56, Russo 2014: 2). Furthermore, interpreters are usually described by their peers as self-reliant, extroverts, intelligent, actors, somewhat superficial and arrogant, having a liking for variety, and possessing nerves of steel and high levels of self-confidence (Rosiers et al. 2011: 56).

In summary, interpreters should have the following qualities: fluency in all of their language combinations; a broad general knowledge coupled with a keen interest in learning; good shortand long-term memory; excellent linguistic skills; an outgoing and strong personality but is still able to work in a team and understand cultural subtleties; strong motivation; and a high tolerance for stress. These qualities can be divided into three categories: cognitive variables, affective variables (such as motivation and attitudes), and personality variables (such as being an extrovert) (Rosiers et al. 2011: 55).

2.2 Aptitude tests

Aptitude tests for interpreting generally reflect open-ended testing instruments, similar to essays, where the statistical methods of reliably estimating the individual test items are extremely difficult to apply (Campbell and Hale 2003: 221). That is to say, the issue of grading is usually highly subjective. Most scholars in the literature have assembled batteries of tests of cognitive skills, personality, and performance under stress. The candidates' performance in these tests is then correlated with final examination scores in order to determine the best predictors of aptitude, and thus success, in interpreting (Longley 1978: 48). The components of these tests are generally described by scholars in their studies, but the administration procedures and assessment criteria are not always specified (Pippa and Russo 2002: 249), making it difficult for future scholars to replicate the tests for validity or even further build upon them.

Traditional testing methods include holistic communicative tasks such as bilingual or multilingual interviews, on-the-spot speech production, and oral summary renditions in another language. These tests determine general knowledge and language proficiency, but have a strong subjective component, particularly in grading (Pöchhacker 2004: 181). Yet it is important that test designers ensure the reliability and validity of their test constructs (Campbell and Hale 2003: 205).

Literature shows that many projects on reliable aptitude testing have been attempted, from the broad range of Gerver et al.'s (1989) series of cognitive and linguistic tests to Russo and Pippa's (2004) single paraphrasing test. These include, among others: written cognitive aptitude tests, e.g. written translation, rewriting, and summary writing; memory aptitude tests, e.g. the Wechsler Memory tests and recall tests; and spoken cognitive aptitude tests, e.g. interviews, sight translation, shadowing, error detection, paraphrasing, cloze, synonyms, and SynCloze.

Then there is also testing for personality traits: e.g. Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), Achievement Motivation Test (AMT), Gardner's Attitude/Motivation Test Battery (AMTB), Nufferno Speed Tests, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), and tests for self-efficacy, goal orientation, and negative affectivity.

It is evident that a wide variety of tests is available but it is unnecessary to include tests that determine the same skills. Bingham (1942: 220) states that a test will contribute the most to a battery when it not only closely correlates with the criteria to be tested, but also does not closely correlate with other tests in the battery. Thus, when one compares paraphrasing with the synonyms test, it is clear that both tests determine language fluency and linguistic skills, while synonyms further determine memory skills, and paraphrasing further determines expressive ability and stress or anxiety.

3. Method

The empirical survey for this article encompasses questionnaires for two groups of respondents, namely the trainers and students, as well as interviews with the students. The necessary ethical clearance was granted by Stellenbosch University (project number: AFR-207-0864-603) for this purpose.

3.1 First group

The first group of respondents consisted of the interpreting trainers - those individuals who teach, lecture, or are involved in the teaching of interpreting to individuals at a tertiary level. In order to select the sample of trainers to send the online questionnaires to, it was first necessary to determine which tertiary institutions offer interpreting training. From a simple internet search, a list of institutes can be found that offer training in interpreting in South Africa. The researchers of this study used the list provided by the South African Translator's Institute (2007) and compared it with the list provided by Lexicool (2017). This comparison resulted in 13 tertiary institutes that offer interpreting studies in South Africa. Table 1 shows the final 10 institutes, the department which offers the course, the type of course offered, and the number of interpreting trainers that were contacted at each institute.

Of the 14 surveys sent out, six responses were received. In other words, a return of approximately 43% was achieved.

3.2 Second group

The second group consisted of a sample of possible interpreting candidates who were selected from undergraduate language students at Stellenbosch University (Department of Afrikaans and Dutch, and Department of Modern Foreign Languages). Timarová and Salaets (2011: 35) point out that a limitation on aptitude testing research in interpreting is related to population size. Therefore, in order to achieve a larger sample, undergraduate students who had some basic knowledge of the interpreting practice and who had completed a component on interpreting in their curriculum, were asked to participate, rather than only selecting from current interpreting students.

Survey invitations were sent out to a total of 41 third-year students from the departments of Afrikaans and Dutch, and Modern Foreign Languages (specifically, the French section) at Stellenbosch University. A total of 15 responses were received, which is an average return of approximately 37%.

3.3 Data collecting instruments

The questionnaire for the first group of respondents (Addendum A) was designed to gather data on their current forms of aptitude tests (if applicable) and the skills they test. The questionnaire for the second group (Addendum B) was designed to determine the difficulty that would be involved in completing the aptitude tests.

The interview questions for the second group were structured in order to gain clarification on certain answers to the questionnaire given to that group. The interviews were of a semi-structured design to allow for more in-depth conversations on the topic of the study. Furthermore, this design allowed for a flexible interview, which is a key factor in interviewing that allows the interviewer to respond to any issues that emerge during the interview. An interview guide was developed to provide the researcher with an outline of the main topics to be covered, but still allow the flexibility for the interviewee to lead the interview (King and Horrocks 2011: 35).

Six students (who took part in the online questionnaire) were invited to take part in an interview. The interview process opened with general background questions to ease the interviewee into the more in-depth opinion and knowledge questions. The researchers hoped to find an answer to the question of whether aptitude tests add to the improvement of the quality of the interpreting profession. This was done during the interview by providing candidates with a better understanding of interpreting in general and their ability to complete an interpreting programme specifically.

4. Results

Regarding the background information (i.e. Questions 1 to 6 of the questionnaire for the first group, the trainers), four out of the six respondents indicated that their programme is a postgraduate course, and two indicated an undergraduate course. Three of the courses are one-year generic courses, one is a two-year specialised course, one course is 18 months long, and one is an unspecified amount in duration. This indicates that the average amount of time of an interpreting course in South Africa is 15,6 months. An average of approximately 16 candidates apply for these courses, and an average of approximately two candidates drop out during the year. In addition, four out of the six trainers indicated that the applying candidates do not have previous experience with interpreting. In other words, an average of approximately 67% of candidates applying for interpreting courses do not have any experience with interpreting.

The trainers were then asked if it was preferable for the candidates to have previous knowledge of interpreting. The majority (that is, four) indicated that it was not necessary, as the programmes assumed beginner status and so taught the basics of interpreting, although some knowledge as to what interpreting is would be to the students' benefit. However, two of the six interpreters stated that experience is necessary for a postgraduate course "so that [students] can build on this experience and work at a specialised level" (Trainer 2).

Question 7 asks: In your opinion, what are the characteristics and/or skills of an "ideal" interpreter? The list of skills, including the frequency agreed upon by the trainers, are as follows:

• Near native fluency in A and B languages (f = 3)

• Good language skills (to this is added the ability to reformulate a language into another) (f = 3)

• Interest in current affairs (f = 3)

• Inquisitive nature and eagerness to learn (f = 3)

• Good general knowledge (f = 2)

• Research competence (f = 2)

• Ability to think on one's feet (f = 2)

• Not being a perfectionist (f = 1)

• Competence in a C language (f = 1)

• Cultural competence (f=1)

• Knowledge of content fields (e.g. law) (f = 1)

• Computer literacy (f = 1)

• Passion for languages (f = 1)

• Good concentration and focus (f = 1)

• Ability to remain calm under high stress (f = 1)

• Good voice (f = 1)

• Confidence (f = 1)

• Analytical skills (f = 1)

• Memory skills (f = 1)

Question 8 focuses on the value of an aptitude test: What is your opinion on aptitude testing? The respondents' feedback on this question in general was that aptitude testing is an excellent tool as it will give the candidate an idea of whether s/he is suitable for the profession and will also determine the possible success rate of the students. Candidates with language or speech problems (e.g. soft speakers or possible speech impediments) can be determined beforehand. The language capabilities and the levels of the candidates' two languages can also be determined as it is not a language acquisition programme. This means that students' language skills (listening, comprehension, and speaking) should be on an acceptable level as comprehension and deverbalisation is of utmost importance for the (trainee) interpreter.

The trainers were asked if their courses currently had a screening procedure (Question 9), and two out of the six respondents answered "yes". In other words, only one third of training institutes actively screen their applicants for interpreting potential. Access to the one programme consists of a three-and-a-half-hour test comprising a translation, a written opinion on a short text, and a text to be edited. Borderline cases are invited to a second screening consisting of an oral interview and a summarising test. The second respondent did not provide details of his/her institute's screening procedure, but simply indicated that s/he considered it to be sufficient. The four trainers who answered negatively to the question on screening procedures were asked to provide a list of the skills that they would wish to test for (Question 10). Three indicated language skills (with one respondent further expanding that to listening, writing, and speaking), one trainer advocated for concentration skills and the ability to stay calm, one trainer wished for analytical and memory skills, and one simply stated the ability to receive and produce at the same time.

The following results and frequencies were determined with reference to Question 11: Which skills would you wish to test for in an aptitude test?

• Language skills (listening, writing, and speaking) (f = 3)

• Concentration skills (f = 1)

• Ability to stay calm (f = 1)

• Analytical skills (f = 1)

• Memory skills (f = 1)

• Ability to receive and produce simultaneously (f = 1)

Question 12 asked the respondents their opinion on testing for soft skills (i.e. personality traits). One respondent was not in favour, while the rest of the respondents agreed that testing for soft skills is of importance and of value for the interpreter student. The following two responses stood out for us in this regard:

Not everyone who has a good command of a language can become an interpreter. Therefore, certain personal traits are important in the profession.

It probably has its advantages, but I am not in favour of this simply because each individual will develop his unique way of interpreting. Some are born with interpreting skill, others should be taught to interpret.

Question 13 asked if the scores on an aptitude test would be needed immediately, to which five out of the six respondents answered "yes". In response to Question 14 (Which would be better in your opinion: an aptitude test, an introductory course for interpreting, or both?), five of the respondents answered that they would prefer both an aptitude test and an introductory course to interpreting, and one respondent advocated for an aptitude test only. Two respondents failed to give reasons for their answers to Question 14 (as requested in Question 15), including the respondent who preferred the aptitude test. The four respondents who provided a reason generally agreed that an aptitude test would indicate the base knowledge and allow the trainers some insight into the students' abilities. The introductory course would then build on this base knowledge so that all students have a similar background. An aptitude test would also allow the students to make an informed decision on enrolling for the interpreting programme, as one can deduce from the following participant responses:

Aptitude test will screen for the baseline competencies that need to be there. An introductory course in interpreting will ensure that students have a similar theoretical background on which to build and are aware of what it takes to pass a course at this specific institution. Students wishing to go on to MA study partly by coursework should either have passed an introductory course in interpreting or have some prior experience.

With an aptitude test, one tests to see what the student knows about the profession. The introductory course will then build onto that knowledge.

Give an introductory course to give information about what the job is about, and then do a test. It is so that candidates know beforehand what they 're letting themselves in for before they waste their time.

An aptitude test would provide trainers with the opportunity to know their students better, an introductory course for interpreting would allow the students to know more about interpreting in order to be able to make an informed decision on whether they wish to pursue this career or not.

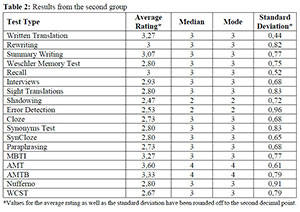

Concerning the second group, i.e. the students, seven out of the 15 respondents were studying BA Languages and Culture, three were studying BA Humanities, and one each was studying the following: BA Law, International Relations, Linguistics and French, and French. One student simply indicated that s/he was in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences. Furthermore, seven of the 15 respondents, approximately 47%, were interested in pursuing a career in interpreting. The 18 Likert scale questions (i.e. Questions 5-23 in Addendum B) of the survey provided students with the name and a short explanation of the various available aptitude tests for interpreting. The students were asked to rate their confidence level in completing any of the aptitude tests on a Likert scale of 1 to 4. The options were as follows: 1 = "I do not understand the concept", 2 = "Not confident", 3 = "Mildly confident", and 4 = "Very confident". An average rating was found for each test, which was then translated into a rating of difficulty for each test. The results from the second group are summarised in Table 2 below:

The purpose of these questions was to find an average rating for the perceived difficulty of each test. However, as can be seen in this table, this is not a sufficient difference to narrow the list of tests to a manageable number for time management on administration of the tests. Therefore, the median and the mode were also calculated in an attempt to find a more diverse range of ratings. However, as is evident in Table 2 above, both values were nearly constant at a rating of 3. The only anomalies are the shadowing and error detection tests rating at 2, and the AMT and AMTB rating at 4. Finally, the standard deviation was calculated to determine to what extent respondents were certain of their answers: written translation had the lowest standard deviation, meaning that the respondents were sure of their responses and there was consistency in the rating received. On the other hand, error detection had the highest standard deviation, which indicates that the ratings received were more evenly spread across the four options and thus that the respondents were less sure of their choice.

5. Findings

The results gathered from the trainer survey indicate that the majority of training institutes in South Africa do not screen potential candidates for interpreting aptitude before entrance is granted to a course. Yet in Questions 8 and 15, the trainers indicated that aptitude testing would allow interpreting trainers to gain insight into the candidates' abilities and thus determine which candidates have the potential to succeed in the profession of interpreting. Consequently, all the trainers were in favour of aptitude testing for interpreting studies. Therefore, it is clear that there is a need for interpreter aptitude testing in South Africa.

The results also indicate that, due to the limited amount of time available for training, it is necessary for candidates to already hold a near-native fluency in their language combinations, as the relative shortness of the interpreting course prevents any language learning from taking place. Therefore, an aptitude test for language ability is a must. On the other hand, the majority of trainers stated that prior knowledge of interpreting is not a requirement for candidates, thus signifying that it is not necessary to test for interpreter skills (such as note-taking and code-switching), as the attainment of these skills will form the focus of interpreter courses. Furthermore, the small number of candidates applying for interpreting courses does not place any constraints on the medium of the aptitude test that can be administered.4

The types of aptitude tests needed can be further specified when considering the traits of the "ideal" interpreter, indicated by the trainers, as well as the traits the trainers would wish to test for. It is evident that trainers ideally expect interpreter candidates to be fluent in their language combinations, hold good language skills as well as a good knowledge base and an interest in acquiring knowledge, and to be cognitively flexible. Moreover, trainers wish to test for language, concentration, analytical and memory skills, as well as the abilities to stay calm, and receive and produce simultaneously. It can be said that the trait of having an interest in gaining knowledge and the ability to stay calm are more personality traits, which the majority of trainers indicated are important skills to test for, possibly with an interview.

When combining these traits with the list of aptitude tests that were proven to be reliable and valid (see Table 3 below), one can determine which tests are already available, and which skills must still be determined via new tests. It is therefore clear that only a test for concentration skills is lacking in the available list.

A possible solution to this lack of a test can be found in Moser-Mercer (1985: 97), where the author suggested the use of dual-task training memory exercises to test a candidate's attention to the primary task of listening to a recorded speech. This exercise is so far untested as to its validity, as Moser-Mercer (1985) suggested it as part of an introductory course to interpreting, meant to be observed over a period of time (in the 1985 case, a period of 10 weeks). However, if simplified by having the candidate recite numbers in his/her A language while listening to a speech also in his/her A language, it is possible that this will prove to be an adequate test for concentration skills, the ability to send and receive simultaneously, and short-term memory skills, through the recollection of the given speech. Therefore, all desired skills to be tested for have a test (or tests) which can be used to determine those skills.

During the interviews, the students indicated that they had some form of exposure to or experience with interpreting before taking part in the current study. However, when asked to explain what interpreting is, 11 survey respondents (group 2) and two students in the interviews explained interpreting as a form of oral translation. Furthermore, three students simply stated that it was a way to convey a message from one language to another. These varied responses show a lack of understanding as to the basic concepts and skills involved in interpreting, in that only one interviewee and two survey respondents alluded to the elements of time involved ("on the spot" (Student 1), "in real-time" (respondents 2 and 4)), with no mention of the fact that the source text is only presented once and there is thus no time for revision or correction in the production of the target text.

Furthermore, when asked what they would expect to learn in an interpreting course, four of the five interviewees believed the course would entail training in language skills. It has already been seen from the results obtained from the lecturers that exceptional language skills are an expected trait in an interpreting candidate, thus not a skill that will be developed during interpreter training. This further shows that students do not understand what interpreting actually entails, which begs the question: how can one make an informed decision on whether to pursue a career in interpreting or not when one does not fully understand what this career entails?

This question brought forth an interesting dilemma in the present study: whether it would be preferential to have an introductory course to interpreting or an aptitude test. An analysis of the results from the trainer surveys shows that trainers would prefer to implement both an introductory training course and an aptitude test, as the course would ensure that all students have a similar background in and base knowledge of interpreting, which would then allow the students to make an informed decision. Following this course, the aptitude test would then provide trainers with an insight into the candidates' abilities. In the interviews, the students agreed with the trainers that an introductory course would give students that basic knowledge of interpreting, thus aiding them in deciding on a future career path. However, three of the five students advocated for the use of an aptitude test after the course, as they explained that an individual might be interested in a particular career but might not have the ability to do well in their chosen career path. Thus, it would seem the need for an aptitude test is validated.

Returning to the concept of aptitude testing, 11 survey respondents (group 2) stated that such testing would be useful and necessary in aiding both the candidates and the institutes in making informed decisions. All five interviewees agreed with this assessment, although there was a marked uncertainty amongst both the survey respondents and the interviewees as to the validity and reliance of aptitude testing. This further validates the necessity of this study and the crafting of a model of effective tests for interpreter training. However, it can be surmised from the students' uncertainty towards the validity of these tests that an aptitude test for interpreting training, at this stage, should not be an exclusionary device. Rather, when there is a shortage of resources available to a particular institute, these tests should aid lecturers in selecting the best students who have the highest possibility of successfully completing the course. Furthermore, as stated by Student 3 in the interviews, if the results of the aptitude test were made available to the candidates, the candidates themselves would then have the necessary information to make an informed decision about their future.

6. Discussion

In order to make an informed decision, an aptitude test model should include tests that are effective and also easy to administer. It is clear that interviews and the AMT should be included in the model, as both these tests were rated high (at an average of 2,9 and 3,6 respectively) with a correspondingly low standard deviation (approximately 0,67 and 0,61 respectively). This indicates that the students were more certain of their answers when the majority rated these tests 3 out of 4 (8 out of 15 respondents) and 4 out of 4 (10 out of 15 respondents) respectively. Similarly, the cloze and paraphrasing tests received a higher rating, an average of 2,7 each, with a lower standard deviation of 0,67 each. Thus, these two tests should also be included.

On the other hand, error detection received a lower rating of 2,5 with a standard deviation of 0,95. This indicates that students were very uncertain as to this test, which can be seen in the more even spread of results on the Likert scale. Therefore, error detection is eliminated from the pool of possible tests. The shadowing test received the lowest rating out of the eight proven tests (an average of 2,4) and has a relatively low standard deviation of 0,71, indicating that students were more certain when the majority (7 respondents) rated this test as a 2 on the Likert scale. Therefore, shadowing is also eliminated from the aptitude test model even though it is a very popular test.

Finally, there is some uncertainty as to the synonyms test and the WCST. The synonyms test received an average rating of 2,8 but has an equally high standard deviation of 0,83. Therefore, the respondents were not certain of this test or their response to it, although the majority (7 out of 15 respondents) rated the test as a 3 on the Likert scale. The WCST received an average rating of 2,6 with a standard deviation of 0,78. Therefore, while the majority of respondents (7 out of 15) rated this test as a 3 on the scale, they were uncertain of their response. However, as the synonyms test is currently the only proven test for interpreting which tests memory skills, and the WCST for cognitive flexibility, it seems that these two tests should be included in the aptitude test model in order to test the full range of skills as required by the lecturers. Furthermore, according to Bingham (1942: 220-221), if the scores of a test are near either the upper limit or lower limit, the test will usually be less reliable than a test with scores around the middle range. In other words, a test should be neither too easy nor too difficult to complete - a criterion which the synonyms test and the WCST would seem to fulfil. Moreover, both tests do not require spoken skills, as the synonyms test requires candidates to write their answers while the WCST does not require a candidate to speak or write at all. Therefore, the issue of spoken language anxiety is negated in these tests.

A further uncertainty lies with the interviewees and their rating of the dual-task training memory exercise. Despite its lower rating of 2,4 with a standard deviation of 0,48, this test cannot be compared with the others as a smaller sample group was used. Therefore, while there is a higher uncertainty towards this test, at present it should be included as there is no other available, proven interpreting aptitude test for concentration skills aside from Chabasse and Kader's (2014: 26-27) use of cognitive shadowing, which has been eliminated due to the students' uncertainty towards that test. Consequently, the seven tests that fit the requirements of testing the skills wished for by the trainers but which are still easy for candidates to complete are: interviews, cloze, synonyms, paraphrasing, AMT, WCST, and the dual-task memory test.

A further consideration needs to be made regarding time constraints. In the surveys, the trainers indicated that results of any aptitude test would be needed immediately, thus an aptitude test model needs to be easy to administer in a short period of time as well as easy to evaluate. This places a slight constraint on the number of individual tests that can be included in the model. At present, the tests, which must be administered and scored individually as they involve spoken tests, are the interviews, cloze test, WCST, and dual-task training memory exercise. It must be reiterated from the literature review that interviews, while proven to be effective, have a tendency to be extremely subjective and difficult to score. Therefore, it was suggested in the review that interviews be kept aside as a last resort for evaluating borderline cases after the results from the aptitude test model have been determined.

A final count of five tests (Table 4) to be included in the aptitude test model was reached. These tests include the cloze test, synonyms, WCST, dual-task training memory exercise, and interviews. The table also indicates the qualities they test:

The implementation of a time limit on a battery of tests is discussed by Foxcroft (2013: 73). This author references Israeli universities as demonstrating that an overall time limit of 150 minutes proved to be effective and increased predictive validity by 20%. Conversely, she further states that the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University in South Africa has found that the assessment of multicultural groups is enhanced if there are no time limits. However, as interpreting requires an element of speed and the ability to remain calm in stressful situations, implementing a time limit would more effectively assess interpreting students' capabilities. It must then be considered that a time limit will place restrictions on the number of tests to be included in the aptitude test model (Foxcroft 2013: 73).

7. Introductory course versus aptitude test

With a selection of tests in place, it is important to consider the factors involved in test development. This includes test and language anxiety as well as ethics, fairness, and cultural awareness.

According to Helms-Lorenz and Van de Vijver (1995: 161), there are various subject-related factors that can have an impact on test performance, including (but not limited to) test-wiseness. Test-wiseness is the ability to perform well on tests and to handle the time limits usually imposed on tests. When an individual is not test-wise, they are said to exhibit test anxiety, which is usually characterised by feelings of worry about performing well or running out of time. These feelings impact concentration on the task at hand and are a common problem which diminishes the validity of tests (Kaplan and Saccuzzo 2001: 510). This form of anxiety leads to task-irrelevant responses, which causes a person to respond in ways that interfere with his/her performance, thus negatively impacting the results of the test (Kaplan and Saccuzzo 2001: 512). According to Helms-Lorenz and Van de Vijver (1995: 163, 165), there are ways of reducing bias caused by anxiety and culture. Clear, lengthy instructions can be given to candidates taking aptitude tests, followed by providing examples and then exercises, and avoiding complicated grammatical structures and local idioms. Otherwise, test-wiseness can be increased by using familiarisation and training.

Another concern for the development of a test design is fairness. Fair assessment practices, according to Foxcroft, Roodt and Abrahams (2013: 117-118), involve:

• the appropriate, fair, professional, and ethical use of assessment measures and assessment results;

• the needs and rights of those involved;

• the assessment conducted closely matching the purpose for which the assessment results will be used; and

• the broader social, cultural, and political context in which assessment is used.

In his studies with second language English students, Horwitz (2001: 115) stated that implementing an introductory course to interpreting could aid students by allowing them to familiarise themselves with the various exercises in the aptitude test model, which would then greatly reduce test anxiety. As stated by Student 1 in the interviews, "the more exposure you get, the better, and you can also see where you're at before you start".

It also became apparent in the interviews that some students are concerned about the amount of oral language training they receive in foreign language learning classes. For example, Student 2 expressed the following concern:

Given the way that languages are taught currently, I think you would find that the results of a spoken aptitude test would be lower than the written test, but I think that it's important to understand the level that people are willing- that people are at in terms of speaking. So, I don't think that [spoken aptitude tests] would be unhelpful; I think it would be very helpful but it also would be helpful in showing that, you know, maybe there needs to be a restructuring of language courses in general to include more oral teaching, as opposed to written [sic].

Furthermore, the implementation of an introductory course would introduce more students to the concept of interpreting as a professional occupation, as there are possibly not many people who are familiar with it as a field of study (Student 4). In addition, Moser-Mercer (1985: 100) states that an introductory course provides trainers with the opportunity to observe students over an extended period, which allows for greater accuracy in judgement. Yet testing still provides a quick, economic, and objective way to gain information about people and can be used to enhance decision-making (Bedell, van Eeden and van Staden 1999: 1). As a result, the authors of the current article suggest the use of aptitude testing until the field of interpreting has reached a more stable level of professionalisation in South Africa. With an adequate level of professionalisation, it is possible that interpreter training courses would receive more recognition, and an introductory course could then be presented in undergraduate study to make the option of interpreting more available to a wider range of potential candidates.

8. Conclusion

The initial objective of this article was to develop a custom-made aptitude test for simultaneous interpreting, thereby determining which aptitude test is most suitable for the South African context and also which components can best be used to effectively screen applicants for interpreting training. The underlying principle was to optimise the number of test activities used to assess the various skills and personality traits that are needed for students to succeed in their training.

The article has presented the data gathered from the surveys sent out to interpreter trainers and from those sent out to students at Stellenbosch University, as well as the pertinent data gathered from the interviews. This formed the basis for crafting a custom-designed aptitude test suitable for at least the South African context. One of the limitations of the study is that, due to the very small sample size (especially for the first group), the results cannot be seen as convincing and subsequently cannot be extrapolated to the population. Nevertheless, the insight gained from the results was used to narrow down the list of available aptitude tests that could be utilised in an aptitude test model. The issues of test and language anxiety, and the ethics and fairness of aptitude testing, were analysed. This further reduced the list of available tests to a final model of five aptitude tests. The challenge that remains is to put the findings to the test in practice and monitor the outcomes.

References

Bedell, B., R. van Eeden and F. van Staden. 1999. Culture as moderator variable in psychological test performance: Issues and trends in South Africa. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology 25(3): 1-7. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v25i3.681 [ Links ]

Bingham, W. 1942. Aptitudes and aptitude testing. New York and London: Harper & Brothers Publishers. [ Links ]

Campbell, S. and S. Hale. 2003. Translation and interpreting assessment in the context of educational measurement. In G. Anderman and M. Rogers (eds.) Translation today: Trends and perspectives. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters Ltd. pp. 205-224. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781853596179-017 [ Links ]

Chabasse, C. and S. Kader. 2014. Putting interpreting admission exams to the test: The MA KD Germersheim project. Interpreting 16(1): 19-33. https://doi.org/10.1075/bct.68.09cha [ Links ]

Corsellis, A. 1999. Training of public service interpreters. In M. Erasmus, L. Mathibela, E. Hertog and H. Antonissen (eds.) Liaison interpreting in the community. Pretoria: Van Schaik. pp. 197-205. [ Links ]

Donovan, C. 2006. Training's contribution to professional interpreting. In M. Cai and J. Zhang (eds.) Professionalization in interpreting: International experiences and developments in China: Shanghai. Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press. pp. 72-85. [ Links ]

Foxcroft, C. 2013. Developing a psychological measure. In C. Foxcroft and G. Roodt (eds.) Introduction to psychological assessment in the South African context. Cape Town: Oxford University Press Southern Africa. pp. 69-81. [ Links ]

Foxcroft, C., G. Roodt and F. Abrahams. 2013. The practice of psychological assessment: Controlling the use of measures, competing values, and ethical practice standards. In C. Foxcroft and G. Roodt (eds.) Introduction to psychological assessment in the South African context. Cape Town: Oxford University Press Southern Africa. pp. 109-124. [ Links ]

Garzone, G. 2002. Quality norms in interpretation. In G. Garzone and M. Viezzi (eds.) Interpreting in the 21st Century: Challenges and opportunities. Selected papers from the 1st Forll Conference on Interpreting Studies, 9-11 November 2000. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins. pp. 107-119. https://doi.org/10.7202/009362ar [ Links ]

Gerver, D., P. Longley, J. Long and S. Lambert. 1989. Selection tests for trainee conference interpreters. Translators' Journal 34(4): 724-735. https://doi.org/10.7202/002884ar [ Links ]

Helms-Lorenz, M. and F.J.R. Van de Vijver. 1995. Cognitive assessment in education in a multicultural society. European Journal of Psychological Assessment 11(3): 158-169. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.1L3.158 [ Links ]

Horwitz, E. 2001. Language anxiety and achievement. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 21: 112-127. [ Links ]

Kaplan, R.M. and D.P. Saccuzzo. 2001. Psychological testing: Principles, applications, and issues. Belmont: Wadsworth Thomson Learning. [ Links ]

Keiser, W. 1978. Selection and training of conference interpreters. In D. Gerver and H. Wallace Sinaiko (eds.) Language interpretation and communication. New York: Plenum Press. pp. 11-24. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-9077-43 [ Links ]

King, N. and C. Horrocks. 2011. Interviews in qualitative research. Los Angeles: SAGE. [ Links ]

Kurz, I. 1993. Conference interpretation: Expectations of different user groups. In F. Pöchhacker and M. Schlesinger (eds.) The interpreting studies reader. London: Routledge. pp. 313-324. [ Links ]

Longley, P. 1978. An integrated programme for training interpreters. In D. Gerver and H. Wallace Sinaiko (eds.) Language interpretation and communication. New York: Plenum Press. pp. 45-56. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-9077-46 [ Links ]

Macnamara, B., A. Moore, J. Kegl and A. Conway. 2011. Domain-general cognitive abilities and simultaneous interpreting skill. Interpreting 13(1): 121-142. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.13.L08mac [ Links ]

Marais, K. 1999. Community interpreting and the regulation of the translation and interpreting profession(s) in South Africa. In M. Erasmus, L. Mathibela, E. Hertog and H. Antonissen (eds.) Liaison interpreting in the community. Pretoria: Van Schaik. pp. 303-310. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.5.1.10swa [ Links ]

Moser-Mercer, B. 1985. Screening potential interpreters. Translators' Journal 30(1): 97-100. [ Links ]

Pienaar, M. and E. Cornelius. 2015. Contemporary perceptions of interpreting in South Africa. Nordic Journal of African Studies 24(2): 186-206. [ Links ]

Pippa, S. and M. Russo. 2002. Aptitude for conference interpreting: A proposal for a testing methodology based on paraphrase. In G. Garzone and M. Viezzi (eds.) Interpreting in the 21st Century: Challenges and opportunities. Selected papers from the 1st Forli Conference on Interpreting Studies, 9-11 November 2000. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins. pp. 245-256. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.43.24pip [ Links ]

Pöchhacker, F. 2004. Introducing interpreting studies. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Pöchhacker, F. and M. Liu (eds.) 2014. Aptitude for interpreting. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Rosiers, A., J. Eyckmans and D. Bauwens. 2011. A story of attitudes and aptitudes? Investigating individual difference variables within the context of interpreting. Interpreting 13(1): 53-69. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.13.1.04ros [ Links ]

Russo, M. 1989. Text processing strategies: A hypothesis to assess students' aptitude for simultaneous interpreting. The Interpreters' Newsletter 2: 57-64. [ Links ]

Russo, M. 2011. Aptitude testing over the years. Interpreting 13(1): 5-30. [ Links ]

Russo, M. 2014. Testing aptitude for interpreting: The predictive value of oral paraphrasing, with synonyms and coherence as assessment parameters. Interpreting 16(1): 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1075/bct.68.07rus [ Links ]

Russo, M. and S. Pippa. 2004. Aptitude to interpreting: Preliminary results of a testing methodology based on paraphrase. Translators' Journal 49(2): 409-432. https://doi.org/10.7202/009367ar [ Links ]

Shlesinger, M. and F. Pöchhacker. 2011. Aptitude for interpreting. Interpreting 13(1): 1-4. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.13.1.01int [ Links ]

Timarová, S. and H. Salaets. 2011. Learning styles, motivation and cognitive flexibility in interpreter training: Self-selection and aptitude. Interpreting 13(1): 31-52. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.13.L03tim [ Links ]

1 Interpreting is never a case of merely understanding the source language message and delivering it in a word-byword translation. Rather, it is a complete rendition, at a very rapid rate, of the original message along with the speaker's intended contents, shades, and emotions in such a way that the listener does not realise that a translation has been delivered (Keiser 1978: 13).

2 It would be preferable to assess one particular skill with one particular test. If one attempts to assess multiple skills with one test, there may potentially be confusion as to which skill actually generates the result. However, it would be impossible to do this based on time and economic constraints.

3 The article referenced here is part of a series of articles published in the 2011 issue of Interpreting 13(1), from a collection of papers given at a symposium held in Antwerp in 2009, entitled "Aptitude for Interpreting: Towards Reliable Admission Testing" (Pöchhacker and Liu 2014: 1). This collection of papers has since been republished in Pöchhacker and Liu's (2014) edited volume, Aptitude for Interpreting. Hence, this reference can also be seen in Macnamara, Moore, Kegl and Conway's (2014: 107-108) contribution to Aptitude for Interpreting.

4 An example of a constraint can be seen in a written test being easier to administer to a larger group of candidates than an oral test which must be conducted individually.

ADDENDUM A - Trainer questionnaire

1. Is this course a postgraduate or undergraduate course?

2. How long is this course?

- 1 year general course

- 1 year specialised course (i.e. court interpreting)

- 1 year general + 1 year specialised course

- 2 year general course

- 2 year specialised course

- Other

3. Approximately how many students apply for this programme per year?

4. Approximately how many students drop out during the course or fail at the end of the course (total numbers)?

5. Do the candidates (i.e. those applying for an interpreting course) generally have previous experience with interpreting?

6. Would it be preferable for candidates (i.e. those applying for an interpreting course) to have previous knowledge of or experience with interpreting?

7. In your opinion, what are the characteristics and/or skills of an "ideal" interpreter?

8. What is your opinion on aptitude testing?

9. Does this course have a screening procedure?

10. If yes to 9, what does the screening procedure entail, and do you think it is sufficient and effective? If not, which skills would you wish to test for in an aptitude test?

11. If no to 9, if you did have an aptitude test, which skills would you wish to test for?

12. What is your opinion on testing for soft skills (i.e. personality traits)?

13. Would the scores or evaluations of an aptitude test be needed immediately?

14. Which would be better in your opinion: an aptitude test, an introductory course for interpreting, or both?

15. Please provide a reason for your answer to the above question.

ADDENDUM B - Student questionnaire

1. Please state your current field of study.

2. Do you have an interest in pursuing a career in interpreting?

3. What do you understand by the term "interpreting"?

4. What is your opinion on entrance exams or aptitude tests in general?

The following questions have to do with types of aptitude/entrance tests and how easy or difficult they are to understand and complete. Please rate the questions on a scale of 1 - 4, with 1 = I don't understand the concept, 2 = Not confident, 3 = Mildly confident, and 4 = Very confident.

5. Written translation is the transposition of a text written in one language into a text written in another language. How confident are you in successfully completing this test?

6. Rewriting requires the rewriting of three sentences each in two different ways. How confident are you in successfully completing this test?

7. Summary writing involves a written summary in your A language (mother tongue) of a written or oral speech given in your A or B language. How confident are you in successfully completing this test?

8. The Wechsler Memory Tests consist of a list of words grouped into memory units which must be recalled in their original order. How confident are you in successfully completing this test?

9. Recall tests generally involve the reconstruction of the content of a discourse differently (i.e. through paraphrasing, summarising, or over-generalising). How confident are you in successfully completing this test?

10. Interviews involve one-on-one conversations with a judge, an improvised short speech on a randomly chosen topic, or a short presentation on a cultural or current event. How confident are you in successfully completing this test?

11. Sight translation involves the transposition of a text written in one language into a text delivered orally in another language. How confident are you in successfully completing this test?

12. Shadowing involves listening to a text and simultaneously repeating it word-for-word in the same language. How confident are you in successfully completing this test?

13. Error detection requires the detection of lexical errors (such as a non-word resulting from a slip in mispronunciation), syntactic errors (such as an alteration of the tense of a verb), and semantic errors (such as the insertion of words that are different in meaning from those in the text) in an auditorily presented text. How confident are you in successfully completing this test?

14. The cloze test requires restoring words that have been deleted from a text by relying on anticipation based on experience (or knowledge of current affairs) coupled with perception of the structure and internal relationship of the text. How confident are you in successfully completing this test?

15. The synonyms test requires noting as many synonyms as possible for a given word. How confident are you in successfully completing this test?

16. The SynCloze test requires filling in gaps in a text based on the content, and also supplying as many contextually appropriate synonyms as possible. How confident are you in successfully completing this test?

17. In a paraphrasing test, you are asked to render the meaning of a message into other words and in a different syntactic construction. How confident are you in successfully completing this test?

18. The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator consists of a series of personality related, situational questions which you must rate on a Likert scale (the measure of the level of agreement or disagreement). How confident are you in successfully completing this test?

19. The Achievement Motivation Test consists of a 90 multiple-choice item questionnaire and you must choose the response you most favour for each statement. How confident are you in successfully completing this test?

20. Gardner's Attitude/Motivation Test Battery consists of a list of statements that you must respond to on a Likert scale. How confident are you in successfully completing this test?

21. The Nufferno test involves three sets of letter series problems which you must solve, first timed and then untimed. How confident are you in successfully completing this test?

22. The Wisconsin Card Sorting Test entails sorting a deck of 64 cards into four different slots. However, you will only receive feedback as to the correctness or incorrectness of the categorisation you have chosen after sorting each card, with no explanation given as to why. There are three rules to the categorisation of cards, but you will not be told which rule is being applied. These rules can also change without warning during the test and you must then adjust to the new rule. How confident are you in successfully completing this test?

23. What is your opinion on the aptitude tests mentioned and the understanding you may gain through these tests of your ability to complete an interpreting course and to perform as an interpreter?