Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus (SPiL Plus)

On-line version ISSN 2224-3380

Print version ISSN 1726-541X

SPiL plus (Online) vol.61 Stellenbosch 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.5842/61-0-919

ARTICLES

A long walk to freedom: Charting a way for doing comparative translation studies in Africa

Kobus Marais

Department of Linguistics and Language Practice, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa E-mail: jmarais@ufs.ac.za

ABSTRACT

In recognition of the work that Ilse Feinauer has done for the development of translation studies in Africa, this paper considers the position of translation studies on the continent. It proposes a comparative approach to translation studies on the continent to counter the two extremes of universalism and provincialism in the field of study. After considering some of the epistemological problems that translation studies faces in Africa, the paper suggests that a complex adaptive systems approach linked to a semiotic conceptualisation of translation allows for this kind of comparative approach. The paper concludes with some suggestions about the nature of comparative work in translation studies.

Keywords: translation; Africa; comparative; semiotics; biosemiotics

1. Introduction

Ilse Feinauer and I have been involved in numerous discussions and experiences about translation studies in Africa. Since I contacted her, probably sometime in 2008, to join me in hosting the first Summer School for Translation Studies in Africa (SSTSA) in Bloemfontein in 2009, we have discussed the problems of translation studies in Africa, organised six summer schools, experienced different contexts of translator training in Africa, and collaborated with students and lecturers from all over Africa. We have debated the dominance of training over research in most institutions on the continent, we have considered the impact of the lack of resources at African universities, and we have spoken about ways to organise SSTSA in such a way that we achieve the most impact. From the deliberations at SSTSA, also with the participants and keynote speakers of each summer school, flowed the founding of the Association for Translation Studies in Africa (ATSA) in Nairobi. Ilse had a large hand in drafting the constitution and setting in place structures for ATSA. Except for the problems the continent faces, about which Ilse made some scholarly contributions of her own (Feinauer 2016, Feinauer and Lesch 2013, Fourie and Feinauer 2005), we were constantly musing about the future of translation studies in Africa or a research agenda for the continent. These musings found their way into a co-edited volume (Marais and Feinauer 2017) in which we explored the possibilities of translation studies in Africa moving beyond the postcolonial debate. This volume was an exploration of Bandia's (2012, 2013) ideas, discussed in detail at the 2014 SSTSA in Zambia, that a postcolonial cultural approach could limit the purview of translation studies to the postcolony in Africa and to culture, thus ignoring translation issues that arose after decolonisation itself.

Translation studies in Africa finds itself in a curious space, I think. For one, it remains influenced (to what extent is debatable) by translation theory that originated outside of the African context. For another, data from the continent itself remains relatively weakly theorised (again, the extent of which is debatable) or theorised in categories that originated in different contexts. While this situation need not be undesirable in itself, scholars on the continent may want to reflect on it and respond to it. One example of possible implications of the situation should suffice. Community translation in Europe, for instance, and the literature that has arisen from that context is usually set in the context of populations that have immigrated to predominantly monolingual countries. Africa has few, if any, countries in which the population speaks only one language. Thus, community translation potentially plays a different role. The question is whether the nuances of practice in the African context have been studied on their own terms rather than in terms of "European" conceptualisations. In other words, can community translation scholars in Africa be sure that the practice is exactly the same as described in the literature and, if not, have they studied the practice itself in order to better understand it and better respond to it (Chesterman 2017a)?

I have touched on most of the issues that I am addressing in this paper, but Ilse Feinauer's sixtieth birthday seems like a good occasion to draw together some thoughts about the long road to liberation that lies ahead for translation studies in Africa, to refine and expand some ideas, to continue the long walk together with colleagues in translation studies in Africa.

2. Problematising epistemological positions in translation studies in Africa

It seems that translation studies in Africa is caught somewhere between a rock and a hard place, having to consider (or not) the decolonisation of its theoretical constructs and having to find (or not) relevant constructs (which may or may not be original) with which to conceptualise and respond to its data. Philosophically, this challenge plays out as finding a nuanced (read: complex) position between universalism and particularism. Ideologically, it plays out in finding a nuanced position in the politics of academia between the other and the self. Epistemologically, this challenge plays out in a complex selection of perspectives from which to study the field, identify translational aspects of practices and phenomena on the continent, and use and adapt approaches and conceptual frameworks. Operating on the hermeneutic assumption that observation cannot take place carte blanche, the question is how and where scholars in translation studies on the continent should place themselves in order to address the challenges I identified above. I argued elsewhere (Marais 2020) that particular theoretical biases in translation studies limit translation scholars in Africa concerning what they are able to "see" in their contexts. The question is thus: Which theoretical constructs will function best as lenses to help us see the translation data in Africa in all its complexity - including its similarities and differences with data from elsewhere?

Postcolonial/postmodern translation studies scholars, and particularly complexity thinkers (Kauffman 2013: 20), argue convincingly that space and time matter. As far as space is concerned, Tymoczko (2007: 68-77) argues that translation cannot be the same everywhere. Her argument is that "Western" translation studies are being informed by "Western" translation practices and that other contexts may lead us to see other practices which, in turn, may lead us to theorise translation differently. In addition, the abundance of historical studies currently being produced in translation studies argue for the importance of time in translation studies (see the work of McElduff and Sciarrino 2014; Delisle and Woodsworth 2012; Pym 1998, 2009; and Robinson 1997 as only a few examples).

While I am partly convinced by Tymoczko's conclusion, I am not convinced by the way she goes about arguing her case, nor by all the implications of her conclusion. The arguments of Tymoczko and others (cf. Susam-Sarajeva 2002) are mainly built on the premises of cultural studies which, in my understanding, are built upon cultural relativism and a number of (stronger or weaker) postmodernist and/or constructivist epistemological assumptions. As problems have been pointed out with the inherent solipsism in both these assumptions (for instance, Deely 2001; Latour 2003, 2007, 2010; and Rabbani 2011; see also Toury 2010 and Trivedi 2007 for a translation studies perspective), I think translation studies should be looking for an alternative conceptual framework from which to compare translation practices in Africa with those in other places in the world. In addition, it has been argued convincingly that neither cultural relativism nor postmodernism provides a conceptual platform from which to perform comparative studies (e.g. Marais 2014: 74-95, Pym 2016) and that one has to look for a broader base for thinking (Eco 1997: 1-25). If one assumes that each culture is a world unto itself and that each human being is a perceptual agent unto herself, one has no basis for comparison. In more philosophical parlance, if you build your argument solely on the local and the contingent, you are not able to draw generalised (holding for more than the local and the contingent) conclusions from your data. A biosemiotic approach (Marais 2019) allows one to delve deeper than language, situating semiosis in the realm of living organisms, not language groups. It acknowledges the biological fact that all of humanity is one species with a shared pool of DNA, which means that humanity is biologically primed to interact despite language differences. It shifts the question from "How different are we as language groups?" to "Why are we able to interact humanely despite the differences?". It shifts the focus to a species-wide "consensus" or "common confession" (Andacht 2014: 16) and to semiotic synechism or continuity (Petrilli 2014) or, what Robinson (2016, 2017) calls, "icosis".

Furthermore, translation studies has been riddled with debates about "what counts as a translation" and how to define translation (Eco 1997, Jakobson [1959] 2012). Looking at early writings in translation studies, interlingual translation or translation proper was the main, if not only, focus of scholars (see, for instance, the section "Foundational Statements" in Venuti 2012). Based on Jakobson ([1959] 2012), scholars became interested in and would agree that, additionally, intralingual translation is to be regarded as translation. Alternative views on inter-and intralingual translation, which I have discussed in detail elsewhere (Marais 2019), could be ascribed to Eco (2004) and Steiner (1998), among others. Enter subtitling and audio description, and scholars would agree, after some debate, that these phenomena could also be studied under the notion of 'translation studies'. Enter the adaptation of drama texts or the transposition of books into movies and the definitions start to flounder because "Is it translation?". Enter the setting to music of a poem or the reworking of a folk song into a symphony and scholars say: "No, now you are diluting the field of study". Enter cultural translation or Latour's (2007) sociology which uses the concept of translation for the transformation of material into social phenomena, and serious warning notes are sounded (see, for example, Toury 2010 and Trivedi 2007, although I do not disagree with all of their criticism on cultural translation).

Here, I attempt to construct a complex, paradoxical, Janus-faced, linked interface between universal and particular, never disavowing the one in favour of the other. It is only on the basis of the universal that the particular becomes meaningful, and it is only on the basis of the particular that the universal becomes meaningful. My work differs from modernists' work such as that of Toury (1995, 2010), who wanted to construct universals. It also differs from cultural relativists such as Tymoczko (2003, 2007) and Baker (2006), who underplay universality and explain all translation principles in terms of contingency. I maintain, in Latourian style (Akrich et al. 2002a, 2002b), a paradoxical, translational, emergent semiotic perspective.

So yes, the perspective is Africanist. And yes, the perspective is universalist. The perspective is comparative, shuttling, on the move, process-oriented. Because there is no neutral third space (Tymoczko 2003), I shall be on the move, continuing to travel between here and there. A long walk - to free Africa from its dependence as well as its burden of trying to be unique. A long walk - to free "the West" from its independence as well as its burden of trying to be unique. Neither "they" nor "us" can be free as long as some of "them" and some of "us" are not yet free.

What is needed in translation studies is a vantage point - a temporally and spatially non-neutral vantage point from which to compare African translation practices and research with that of the rest of the world (Merrell 2003: 181). Put differently, what is needed are conceptual tools that allow for dialogic comparison, for icosis (Robinson 2017). Using the travel metaphor from the title of this paper (mirroring the journey of another, yet much more remarkable, African), I believe that it is possible to draw a map through which one is able to link the little arrow marking the "You are here!" point with the wider map of the territory one wants to traverse. I am not looking for a neutral space; I am looking for a very particular space. I do, however, believe that some spaces provide you with better vantage points than others. Not neutral, not absolute, not good - just better for the purpose of what you would like to see.

So, what would count as beacons on this walk? In this article, I argue that approaching translation from a systems approach - in particular, a complex adaptive systems approach that attends to both structure and agent - is one beacon that could make possible comparative work in translation studies. Note the focus on "complex", not ignoring the agent. I further argue that translation studies should adopt as its scope the interaction between emergent semiosic systems on the condition that these semiosic systems are conceptualised as an all-encompassing semiotics, i.e. logosemiotics as well as biosemiotics (Kull and Torop 2003: 316). In effect, I argue that it is in the interface between the material and the mental, i.e. the semiosic, that translation studies will find a point of comparison for translation practices in different contexts. This theory entails a refinement of Latour's "sociology of translation" approach, explaining why sociology needs the concept of translation (Chesterman 2017b).

I first set out to provide a conceptual framework for thinking from a complex adaptive systems perspective, i.e. conceptualising translation in terms of the interactions between emerging systems. This I link up with the notion of 'emergent semiotics', in which I present the outlines of a theory of semiotics within which to conceptualise translation. I conclude by drawing some implications for comparative translation studies.

3. Relating systems

Using the notion of 'translation' itself as a point of comparison presents one with a number of problems. Firstly, the word "translation" is culturally loaded in the sense that, as Tymoczko (2007) argues, it means different things to people from different cultural backgrounds.

Secondly, it is well known that the word carries etymological baggage, limiting the meaning of the phenomenon under investigation to spatiality (Marais 2014, Tymoczko 2007). Thirdly, the moment one translates the word into other languages, one encounters cultural relativity.

Instead, I turn to the notion of 'systems' and the interaction between systems as a first beacon on the road to comparison. The notion of 'system' is abstract enough to provide us with a point of comparison (Von Bertalanffy 2010). The advantage of systems thinking is that it does not presuppose the data in any way, like the word "translation" does. In other words, one could apply systems thinking to any kind of data in any context. The problem with using, for instance, a particular sociological theory as a framework for comparing translation practices all over the world is that the particular theory has been devised on the basis of a particular social analysis which may not hold for all contexts. In contrast, systems thinking does not have such presuppositions built into it and should therefore render possible a comparison of data in different contexts. Also, systems thinking can be applied to different disciplines of study. Thus, one could have systems thinking in physics and chemistry as well as in biology, psychology, and sociology. One could thus also have it in linguistics and in economics - and therefore in translation studies.

An important advantage of systems thinking is that it allows one to think in terms of process organisation (Hoffmeyer 2008: 46). Translation studies tends to focus too much on phenomena rather than on the relationships between phenomena, the processes of organisation that link phenomena and the particular links themselves. This bias exists while the very nature of translation is that of relationships in process, linking systems, linking sub-systems of systems, or linking parts of a system. Merrel (2003) uses complex adaptive systems theory to point out that all semiotic activities are dynamic processes in nature - they are object-representamen relationships that cause/lead to interpretants which, in turn, become the representamen for a subsequent semiosic process.

I also propose an approach to systems that is in line with Latour's (2007) actor-network theory in the sense that social systems or networks include material phenomena. In fact, I am of the view that the differences between contexts are, at least partly, due to material differences in space and time. From the perspective of complexity, even thoughts or ideas are based in material conditions, i.e. the brain. Simply put, the use of language in Iceland and the use of language in the Sahara differ, not because the people are inherently or mentally different but because the material and temporal conditions under which they live differ. Like Eco (1997: 125), who grounds thinking (and thus semiosis) in being, I ground translation in the physicality of being. People, like any other organism, have to adapt all of their physical and mental abilities to their conditions of living. In the next section, I shall put forward a theory of semiosis that will allow scholars to include the material in comparative translation studies.

Thinking in terms of complex adaptive systems also holds the advantage that the relationships between the system and its parts are themselves seen as complex. Latour's (2007) systems thinking excludes neither the individual translator-actor, nor the pencil, the mouse, the desk, the heat, the nature of the economy, and the politics of the day from a study of translation. With this kind of systems thinking, one should thus be able to study translation at the level of both system and part, society and individual.

I thus propose that systems thinking, and here I mean general systems thinking of the complex adaptive systems variety and not the already applied or limited use of systems thinking in sociology, should form the basis of a comparative translation studies. Such a translation studies would then be able to study and conceptualise relationality of any nature between systems of any nature in places and times of any nature, allowing for comparison in all possible ways. Because the conceptual framework is open to relationships and processes, as well as both system and individual, it should guide the researcher in comparing the full variety of entities, phenomena, and agents involved in translation.

4. Emergent semiotics

The next beacon on the road to a comparative translation studies is semiosis. From a certain perspective, rewriting a book in another language is similar to rewriting a piece of music in another genre. Of course, from other perspectives, there are differences, but these differences have been overemphasised in translation studies to the virtual exclusion of similarities, weakening the ability of the field of study to compare. If one is in search of a basis for comparison, one needs to look at similarities too. A semiotic system is changed into another semiotic system (or linked to another semiotic system) by changing the code or the signs or even perhaps the interpretants under which the initial system operated (Marais 2014, Tyulenev 2011: 79). I thus argue that semiosis provides translation studies with the broadest possible basis for comparison (Goethals et al. 2003: 254).

Apart from linguistic bias, translation studies also suffers from the typically Western bias of a Cartesian schism between material and virtual reality. This bias is visible in the type of paradigms that dominate certain parts of the cultural studies field in which ideas and the spread of ideas are studied as if they had no material basis. A semiosic approach would thus allow one to compare not only different semiosic systems (e.g. those made possible by new technology in the media) but also semiosic systems of different historical and spatial (cultural) origins, even straddling the divide between human and non-human semiosic interactions.

In particular, I posit what I call "emergent semiosis", where I conceptualise semiosis in terms of complex adaptive systems (Marais 2014). The ontology that I envisage is aimed at relativising the Cartesian gap by means of an all-encompassing semiotic approach, including biosemiosis, with the same stroke overcoming the linguistic bias in translation studies. Thus, I view reality as emerging, i.e. being based in the physical out of which, by means of differing organisation and linking, emerges new phenomena such as the chemical and biological. Nothing is added to energy to create matter; rather, it is the specific organisation or linking of energy or systems of energy that create matter (Kauffman 2000: 68). Similarly, when certain configurations of matter are linked or organised in unique ways, biological phenomena emerge out of which psychological and social phenomena emerge in the same fashion.

Each of these points of transfer can be regarded as a phase transition, where the phase of energy transfers to the phase of matter and the phase of matter transfers to the phase of living matter. Now, to my mind, one of the crucial phase transitions that takes place with the emergence of life is that of semiosis. It entails the ability to link material and mental/virtual, i.e. representamen/object and interpretant, thus making it possible to relate to or interact with the "not there" by means of the "there". It is putting something in the place of something else, relating absent and present, getting to know the absent by means of the present, perhaps getting access to the absent by means of the present, perhaps even making the absent possible.

My thinking on semiotics thus entails attention to both bio- and logosemiotics, which I shall discuss now.

4.1 Biosemiotics

One of the problems with current efforts at comparative work in translation studies is that it mostly departs from a cultural studies or comparative literature point of view, both of which are usually built upon a postmodernist epistemology. The problem with this epistemological choice is that one cannot compare if your point of departure is the incommensurability of the phenomena you want to compare. In line with the work done by Latour, I thus suggest that translation studies adopts an approach that will allow for a comparison of all, including the material, conditions that influence the production of translations. Furthermore, a biosemiotic approach to translation promises to counter the anthropocentric (Cronin 2017) and linguicentric biases in cultural studies and comparative literature. In this regard, a biosemiotic approach to semiosis will force researchers to consider the materiality of human interaction as well the continuum between the human animal and the non-human animal as far as semiosis is concerned.

What I am interested in here is thus the notion of 'agent'. What is an agent? What does agency mean? Who/what can be agents? What would count as agents of translation?

Kauffman (2000: 107) pointed out that an autonomous agent, i.e. "a physical system [...] that can act on its own behalf in an environment", has to:

• be a non-equilibrium system

• be able to replicate itself

• be able to complete at least one work cycle

• have a membrane that separates it from its environment

• have a receptor with which to interact with its environment

• have motor abilities

• have a semiosic ability in order to discriminate information from the environment (Kauffman 2000: 109-118, 2013: 5-6; Scarfe 2013: 27).

In this definition, matter cannot be deemed to be alive unless, amongst other things, it is able to interact with its environment and interpret the signals from its environment to its own advantage, i.e. be an autonomous agent. Thus, the semiosic ability is one of the fundamentals of life. This semiosic process is, as Goethals et al. (2003: 258) point out, about processes and relationships; it is always process and it is always process that relates. My thesis is thus that semiosis itself is a kind of a phase transition (Kauffman 2013) where material and the virtual/mental are related. A sign is something that has both material and virtual qualities, i.e. there is always a material sign that is linked up, related to, translated into (Merrell 2003) an interpretant which, to some extent, is virtual, not material (though it may be), linking the material representamen to the immaterial/virtual interpretant, i.e. ideas, thoughts, hopes, decisions, values, etc. Even at the cellular level (Barbieri 2007), life and semiosis are connected in the link between the material cell, chemicals, physicality, and the virtuality of codes such as the genetic code. What is conceptualised as matter and mind thus stand in an irreducible, paradoxical relationship to one another. There can be no meaning without matter, and the nature of living matter is that it makes meaning (Hoffmeyer 2008). Matter and meaning, and matter and value judgement are thus connected through semiosis because an autonomous agent is, by definition, a system that is able to act in its own interest on the basis of its ability to interpret signs. And interest, per definition, entails a value judgement of some sort. It is, amongst others, out of this translation from matter alone to matter and meaning that life and all its possibilities spring. Matter is regulated by (relatively) stable laws while virtuality entails an increasing loosening of the influence of law and an emphasis on creativity and imagination. Exactly how this happens is not yet known, but at this stage, I propose that the nature of semiosis as the paradoxical material/virtual and presence/absence plays a role in this.

In particular, Hoffmeyer's (2008: 80; Hoffmeyer and Emmeche 1991) notion of 'code-duality' seems to be of particular interest to translation studies. Hoffmeyer argues that there are only two basic types of code in reality, i.e. digital codes and analogue codes. For him, life is a process of translation between digitally coded and analogically coded information exchanges. Life starts off with digitally coded information in the genetic makeup of living beings. This digitally coded information has to be translated into analogically coded information in the cell for the cell to function mechanically because a living thing cannot function digitally. Similarly, in the brain, one finds digitally coded exchanges of information, i.e. the individual firings or chemical exchanges between synapses, which are translated into analogically coded information when a human being is able to experience, for instance, a sunrise. Hoffmeyer's code-duality not only provides interesting food for thought for semiotics, but it also doubles as a philosophy or ontology that tries to overcome the Cartesian mind-matter divide. This difference is overcome in the one notion of 'semiosis', which is both material and non-material, both digital and analogical.

Expanding the conceptualisation of translation to include biosemiotics will broaden the comparative ability of translation scholars to include comparisons between human and nonhuman semiosis, amongst others. This would provide a conceptual or philosophical foundation for a truly ecological translation studies.

4.2 Logosemiotics

A specific instance of the larger subset of biosemiotics is what Kull and Torop (2003: 316) call "logosemiotics". This refers to the very specific way in which human beings use sign systems, including language. Biosemiotics thus refers to the pre-linguistic process of meaning-making while logosemiotics is a subset of biosemiotics, referring to meaning-making in organisms endowed with language. This is obviously a constructed distinction based on the assumption that the major phase transition from non-living to living material and the phase transition from semiosis to language are generally accepted distinctions in philosophical, semiotic, linguistic, and other thinking.

Jakobson's ([1959] 2012) conceptualisation of translation assumes and is therefore biased towards a logosemiotic approach to translation. He intends to study the various translation processes from a human perspective, i.e. intra-linguistic and inter-linguistic (translation proper) translation. (The limitation in his notion of 'inter-semiotic translation' is that it does not, overtly at least, include biosemiotics.) Eco (2004: 125) correctly argues that not all interpretation is translation proper, and that one should distinguish between interpretation/hermeneutic activity and translation. However, defining the term "translation" narrowly by limiting its use to 'translation proper' or 'interlingual translation', like Eco does, will not solve the problem of conceptualising translation as such, nor is it helpful in constructing a framework for comparative translation studies. We first need to determine what the outer boundaries of translation are, i.e. to conceptualise it as widely as possible. Once we have some more clarity on that, we can draw finer distinctions or make finer categorisations.

In the semiotics tradition based on Peirce (Colapietro 2003, Merrell 2003), there is a sense in which interpretation1 is translation, i.e. linking semiotic (linguistic) systems to other semiotic (linguistic) systems (words to other words, for instance). Conceptualising fields of study, e.g. translation studies, should include both similarities and differences, i.e. complex interrelations. This means that one should not just focus on differences between interpreting and translation. One could argue that interpreting has, for instance, a different goal, i.e. understanding, whereas for translation, understanding is just one of the goals or part of the process, while both use the same principles, i.e. linking semiotic systems. The implication is that interpreting cannot take place if an agent is not able to link two systems in a semiosic relationship.

I thus suggest that we conceptualise translation studies as widely as possible and then see what data we can come up with to support or invalidate those conceptualisations. In the meantime, scholars who wish to work with a narrower conceptualisation (translation proper only) are obviously welcome to do so - as long as they conceptualise their bias. However, the kind of translation studies that I envisage is more of an interface - a transdiscipline that studies the links, relationships, and processes between systems, be they physical, biological, or logogical.

5. Towards a framework for comparative translation studies

Philosophically and theoretically, the parameters above should make possible the comparison of translators, translation practices, and translation products in all contexts. In particular, I suggest that a comparative translation studies should compare in the following ways.

Firstly, a comparative translation studies should compare the full range of translation phenomena. In the framework above, I opened up the notion of 'translation' to, at least, interaction between semiotic systems of all kinds. This means that there is much more to study than just language or humans. A comparative translation studies should study, at least, all semiotic phenomena where there are examples of translations or, if you will, which are translations (Colapietro 2003, Merrell 2003, Short 2003). This will allow translation scholars to compare the translation of novels with the translation of DNA in cells, for instance. In other words, I am rejecting the notion that only phenomena culturally recognised as "translations" can be studied in translation studies. Rather, I suggest that translation studies study the translational aspect of any phenomenon, wherever it occurs.

Secondly, comparative translation studies should compare the full spatio-temporal, materially determined complexity of context. Translation studies should compare the histories of translation and the geography of the spaces in which translation takes place, but should also focus on the technology, social networks, and cultural influences. Context includes sociological and psychological factors, as well as culture and matter. A comparative translation studies should be a complex translation studies, rejecting all reductionist tendencies. It should be able to compare the translation of a piece of wood into a complex social artefact such as a door (Johnson 1988) as well as the translation of a poem into music. I quote at some length from Latour (2010: 601) to clarify the implications of my own thinking for a comparative translation studies:

The name ["translation" - KM] was a bit awkward but over the years I realized that it was a very handy concept because I now had in hand a comparative method for studying various types of truth production that did not rely on the usual notions (the supernatural and the natural for instance), but instead on two and only two elements: networks of translations on the one hand, and, on the other, the key, the mode or the regime in which they were made to spread. This opened me to a very different vista that I characterized with the word irréduction [...]

Thirdly, a comparative translation studies should compare in an interdisciplinary way, comparing all factors playing a role in translation practices: economic, political, theological, sociological, etc. The suggestion here is not only to include a variety of perspectives but to do this in an interdisciplinary way. By studying translation in the economy with an economist, translation studies scholars are not only to gain a deeper understanding of the issues but also to demonstrate the relevance of the new knowledge to the collaborating discipline. We know only a small portion of what gets translated, in which country, by whom, and why. We have literary theories that claim that translations are made to strengthen the target system, but what about economic translations, political translations, religious translations, educational translations? Also, a comparative translation studies should be able to compare translation practices in formal economies with those in informal economies globally (Marais 2014).

Fourthly, in order to be able to be comparative in an interdisciplinary or even transdisciplinary (Nicolescu 2008) way, translation studies scholars should consider creating transdisciplinary or interdisciplinary centres from which to study translation. The funding models and managerial approaches in most contemporary universities make it very difficult to work in an interdisciplinary or transdisciplinary way from within a traditional department.

As an example of the value that a comparative approach could have, I refer to Beukes' (2007: 125) conclusion after her thorough study of the politics of translation as it pertains to the South African Translators' Institute and the development of Afrikaans. She avers:

[... ] it is clear that, notwithstanding progressive language policy provisions, the implementation of policy - and hence in particular translation practice - has been relegated to the backseat in contemporary South Africa.

Factually, she has presented evidence that supports her finding, so she cannot be faulted on that score. However, this finding shows a lack of awareness of the difference in space and time, including politics, governance, and economics, between Europe, Apartheid South Africa, and post-Apartheid South Africa. Comparing the complexity of the contexts, one would find that Apartheid South Africa had money available for translation because of an exploitative racialised economy, and it had European-style nationalism behind it as a motivator for developing a language. Post-Apartheid South Africa, which does not have colonies or categories of people who can be forced into performing cheap labour, is now berated for putting language implementation on the backseat without any acknowledgement of the different contexts. A comparative approach could lead translation studies scholars to gain insights into the factors from which particular translation-practice trajectories emerge rather than normatively judging the rights or wrongs of these practices.

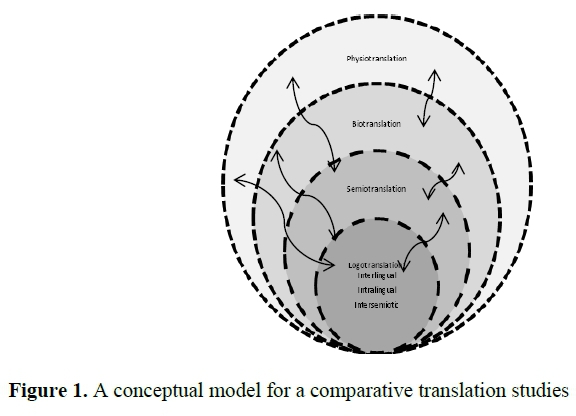

To my mind, the time has come for a differently conceptualised translation studies, which will mean a fully comparative translation studies. Conceptualised as a field of study that focuses on the relationships between systems, this translation studies could sport two distinct but related branches, i.e. physiotranslation and semiotranslation. The first studies the relationships between material systems and the second the relationships between living systems. The field of semiotranslation can then branch into two fields again, namely logotranslation and biotranslation, where logotranslation then entails the three fields determined by Jakobson: intralingual, interlingual, and intersemiotic translation. Note, however, that I distinguish the branches of study in a nested and related relationship (see Figure 1). This implies that even intralingual translation has a physical component to it because it forms part of all kinds of translation. Also, my conceptualisation allows one to conceptualise Latour's notion of 'translation' in which material phenomena are translated into social phenomena by means of semiosis. The spheres of translation are thus all linked. Translations can take place within and between all spheres.

6. Conclusion

I am not suggesting a "West and the rest" binary. Neither am I suggesting a parochial translation studies in and for Africa. Rather, I hope the walk I am suggesting will contribute to opening new points of comparison for translation studies, allowing African and other Global South scholars to compare the translation practices in their contexts with that of scholars all over the world. This goal will only be achieved if our initial assumptions and philosophical points of departure allow us to look at phenomena other than what is prestigious in or determined by vested interests of the West or the East or the Global South. We need as basis for comparison a widely-conceptualised field of translation studies able to study all possible kinds of translational activities and phenomena. We need fresh eyes with which to look at the context(s) in which we work, comparing it with the context(s) in which the other "we" works. We Africans, we Asians, we South Americans, we Europeans, we rich, we poor, we "developed", we "underdeveloped", we however defined, need to take a long walk, need to embrace the walk to explore the meaning of "freedom", also for our field of study.

I honour Ilse Feinauer as one strolling with many of us on this rocky road.

References

Akrich, M., M. Callon and B. Latour. 2002a. The key to success in innovation. Part I: The art of interessement. International Journal of Innovation Management 6(2): 187-206. https://doi.org/10.1142/s1363919602000550 [ Links ]

Akrich, M., M. Callon and B. Latour. 2002b. The key to success in innovation, Part II. Journal of Innovation Management 6(2): 207-225. [ Links ]

Andacht, F. 2014. Semiotic gold at the end of Peirce's rainbow: On the fallible pursuit of reality. In T. Thellefsen and B. Sorensen (eds.) Charles Sanders Peirce in his own words: 100 years of semiotics, communication and cognition. Berlin: De Gruyter. pp. 13-19. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781614516415.13 [ Links ]

Baker, M. 2006. Translation and conflict: A narrative account. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Bandia, P. 2012. Postcolonial literary heteroglossia: A challenge for homogenizing translation. Perspectives: Studies in Translatology 2(4): 419-431. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676x.2012.726233 [ Links ]

Bandia, P. 2013. Translation and current trends in African metropolitan literature. In K. Batchelor and C. Bisdorff (eds.) Intimate enemies: Translation in Francophone contexts. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. pp. 235-251. https://doi.org/10.5949/liverpool/9781846318672.003.0016 [ Links ]

Barbieri, M. (ed.) 2007. Biosemiotics: Information, codes and signs in living systems. New York: Nova Publishers. [ Links ]

Beukes, A-M. 2007. Governmentality and the good offices of translation in 20th-century South Africa. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 25(2): 115-130. https://doi.org/10.2989/16073610709486451 [ Links ]

Chesterman, A. 2017a. Universalism in translation studies. In A. Chesterman (ed.) Reflections on translation theory: Selected papers 1993-2014. Amsterdam: Benjamins. pp. 295-303. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.132 [ Links ]

Chesterman, A. 2017b. Questions in the sociology of translation. In A. Chesterman (ed.) Reflections on translation theory: Selected papers 1993-2014. Amsterdam: Benjamins. pp. 307321. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.132 [ Links ]

Colapietro, V. 2003. Translating signs otherwise. In S. Petrilli (ed.) Translation translation. Amsterdam: Rodopi. pp. 189-215. [ Links ]

Cronin, M. 2017. Eco-translation: Translation and ecology in the age of the anthropocene. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Deely, J. 2001. Four ages of understanding: The first postmodern survey ofphilosophy from ancient times to the turn of the twenty-first century. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. https://doi.org/10.3138/9781442675032 [ Links ]

Delisle, J. and J. Woodsworth (eds.) 2012. Translators through history. Amsterdam: Benjamins. [ Links ]

Eco, U. 1997. Kant and the platypus: Essays on language and cognition. London: Harcourt Inc. [ Links ].

Eco, U. 2004. Mouse or rat?: Translation as negotiation. London: Phoenix. [ Links ]

Feinauer, I. 2016. Are South African print newpaper narratives reframed for Internet news portals or not? Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics 49: 167-197. https://doi.org/10.5842/49-0-685 [ Links ]

Feinauer, I. and H.M. Lesch. 2013. Health workers: Idealistic expectations versus interpreters' competence. Perspectives: Studies in Translatology 21(1): 117-132. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676x.2011.634013 [ Links ]

Fourie, J. and I. Feinauer. 2005. The quality of translated medical research questionnaires. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 23(4): 349-367. https://doi.org/10.2989/16073610509486395 [ Links ]

Goethals, G., R. Hodgson, G. Proni, D. Robinson and U. Stecconi. 2003. Semiotranslation: Peircean approaches to translation. In S. Petrilli (ed.) Translation translation. Amsterdam: Rodopi. pp. 253-267. [ Links ]

Hoffmeyer, J. 2008. Biosemiotics: An examination into the signs of life and the life of signs. London: University of Scranton Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11016-010-9410-7 [ Links ]

Hoffmeyer, J. and C. Emmeche. 1991. Code-duality and the semiotics of nature. In M. Anderson and F. Merrel (eds.) On semiotic modeling. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 117-166. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110849875.117 [ Links ]

Jakobson, R. [1959] 2012. On linguistic aspects of translation. In L. Venuti (ed.) The translation studies reader. 2nd edition. London: Routledge. pp. 138-143. [ Links ]

Johnson, J. 1988. Mixing humans and nonhumans together: The sociology of a door-closer. Social Problems 35(3): 298-310. https://doi.org/10.2307/800624 [ Links ]

Kauffman, S. 2000. Investigations. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Kauffman, S. 2013. Foreword: Evolution beyond Newton, Darwin, and entailing law. In B. Henning and A. Scarfe (eds.) Beyond mechanism: Putting life back into biology. Plymouth: Lexington. pp. 1-24. [ Links ]

Kull, K. and P. Torop. 2003. Biotranslation: Translation between Umwelten. In S. Petrilli (ed.) Translation translation. Amsterdam: Rodopi. pp. 315-328. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110253436.411 [ Links ]

Latour, B. 2003. The promises of constructivism. In D. Ihde (ed.) Chasing technology: Matrix of materiality. Indiana: Indiana University Press. pp. 27-46. [ Links ]

Latour, B. 2007. Reassembling the social. An introduction to actor-network theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1108/eoi.2008.27.3.307.2 [ Links ]

Latour, B. 2010. An attempt at a 'compositionist manifesto'. New Literary History 41(3): 471-490. [ Links ]

Marais, K. 2014. Translation theory and development studies: A complexity theory approach. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Marais, K. 2019. A (bio)semiotic theory of translation: The emergence of social-cultural reality. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315142319 [ Links ]

Marais, K. 2020. Putting meaning back into development; or (semio)translating development. Journal for Translation Studies in Africa 1: 43-58. [ Links ]

Marais, K. and I. Feinauer (eds.) 2017. Translation beyond the postcolony. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [ Links ]

McElduff, S. and E. Sciarrino (eds.) 2014. Complicating the history of Western translation: The ancient Mediterranean in perspective. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315760070 [ Links ]

Merrell, F. 2003. Sensing corporeally. London: Univerity of Toronto Press. [ Links ]

Nicolescu, B. 2008. Transdisciplinarity: Theory and practice. Cresskill: Hampton Press. [ Links ]

Petrilli, S. 2014. Man, word, and the other. In T. Thellefsen and B. Sorensen (eds.) Charles Sanders Peirce in his own words: 100 years of semiotics, communication and cognition. Berlin: De Gruyter. pp. 5-11. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781614516415.5 [ Links ]

Pym, A. 1998. Method in translation history. Manchester: St Jerome. [ Links ]

Pym, A. 2009. Humanizing translation history. Hermes: Journal of Language and Communication Studies 22(42): 23-48. [ Links ]

Pym, A. 2016. A spirited defense of a certain empiricism in translation studies (and in anything else concenring the study of cultures). Translation Spaces 5(2): 289-313. https://doi.org/10.1075/ts.5.2.07pym [ Links ]

Rabbani, M.J. 2011. The development and antidevelopment debate: Critical reflections on the philosophical foundations. Surrey: Ashgate. [ Links ]

Robinson, D. 1997. Western translation theory: From Herodotus to Nietzsche. Manchester: St Jerome. [ Links ]

Robinson, D. 2016. Semiotranslating Peirce. Tartu: University of Tartu Press. [ Links ]

Robinson, D. 2017. Schleiermacher's icoses: Social ecologies of the different methods of translating. Bucharest: Zeta Books. https://doi.org/10.1515/les-2017-0014 [ Links ]

Scarfe, A. 2013. Introduction: On a 'life-blind spot' in Neo-Darwinism's mechanistic metaphysical lens. In B. Henning and A. Scarfe (eds.) Beyond mechanism: Putting life back into biology. New York: Lexington Books. pp. 25-64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-016-9825-7 [ Links ]

Short, T. 2003. Peirce on meaning and translation. In S. Petrilli (ed.) Translation translation. Amsterdam: Rodopi. pp. 217-231. [ Links ]

Steiner, G. 1998. After Babel: Aspects of language and translation. 3rd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Susam-Sarajeva, S. 2002. A 'multilingual' and 'international' translation studies?. In T. Hermans (ed.) Crosscultural transgressions: Research models in translation studies, II: Historical and ideological issues. Manchester: St Jerome. pp. 193-207. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315759944 [ Links ]

Toury, G. 1995. Descriptive translation studies - and beyond. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Toury, G. 2010. Some recent (and more recent) myths in translation studies: An essay on the present and future of the discipline. In M. Muňoz-Calvo and C. Buesa-Gómez (eds.) Translation and cultural identity: Selected essays on translation and cross-cultural communication. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 155-171. https://doi.org/10.21992/t9791x [ Links ]

Trivedi, H. 2007. Translating culture vs. cultural translation. In P. St-Pierre and P.C. Kar (eds.) In translation - Reflections, refractions, transformations. Amsterdam: Benjamins. pp. 277-287. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.71.27tri [ Links ]

Tymoczko, M. 2003. Ideology and the position of the translator: In what sense is the translator 'in between'?. In M. Calzada Perez (ed.) Apropos of ideology: Translation studies on ideology - ideologies in translation studies. New York: Routledge. pp. 181-202. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315759937-14 [ Links ]

Tymoczko, M. 2007. Enlarging translation, empowering translators. Manchester: St Jerome. https://doi.org/10.7202/1013407ar [ Links ]

Tyulenev, S. 2011. Applying Luhmann to translation studies: Translation in society. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Venuti, L. (ed.) 2012. The translation studies reader. 3rd edition. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Von Bertalanffy, L. 2010. An outline of general system theory. In A. Juarrero and C.A. Rubino (eds.) Emergence, complexity and self-organization: Precursors and prototypes. Litchfield: Emergence Publishers. pp. 219-236. https://doi.org/10.1162/artl.2010.16.2.16205 [ Links ]

1 The hermeneutic activity, not "interpreting" as used in interpreting studies.