Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus (SPiL Plus)

versão On-line ISSN 2224-3380

versão impressa ISSN 1726-541X

SPiL plus (Online) vol.61 Stellenbosch 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.5842/61-0-915

South Africa's image as translated in Dutch-language media

Luc van DoorslaerI, II, III

IDept. of Translation Studies, University of Tartu, Estonia

IIDept. of Translation Studies, KU Leuven, Belgium

IIIDept. of Afrikaans and Dutch, Stellenbosch University, South Africa. E-mail: luc.vandoorslaer@ut.ee

ABSTRACT

This contribution first explores the position of Journalistic Translation Research within the discipline of Translation Studies and, subsequently, describes the relevance of relating it to imagological approaches. It presents a case study that analyses how journalistic discourse in current Dutch-language newspapers (both from the Netherlands and Belgium) represents South Africa(ns). Five recurring images and topical fields are distinguished. They do not only build the imageme, i.e. the imagological range of presentations for South Africa(ns) in Dutch-language journalistic representations, but also confirm the constructed character of national and cultural image-building.

Keywords: journalistic translation research; imagology; localisation; representation; framing; national images

1. Introduction: Journalistic Translation Research

"Journalistic Translation Research" (JTR) is a term coined by Valdeón (2015) in his overview of 15 years of research in this field. It mainly originated in the discipline of Translation Studies (TS), where several scholars explicitly acknowledged the central role of translation and language transfer in international news transfers. A few years later, Davier, Schäffner and van Doorslaer showed "that scholarly activity on the topic has not finished after those fifteen years" (2018b: 156) and published a special issue of Across Languages and Cultures, which was focused on "Methods in News Translation" (2018a), thereby linking the historical and conceptual issues of this research strand to the specific methodological challenges.

The discipline of TS over the past decades has moved far beyond the study of a "simple" interlingual transfer between a source and a target text. It is now widely accepted that every translation produces not only linguistic changes, but also modifications at other levels. In our modern societies, this is often not confined to the simple, unambiguous situation of text A resulting in text B. The daily practice of international journalism illustrates both the ubiquity and the complexity of the multiplication of source texts and multi-authored journalistic texts.

In such a complex writing and rewriting situation of text production, both at intra- and interlingual levels, translation in the journalistic field not only disintegrates the status of the single or unique source text, but also problematizes the very concept of traditional authorship. Seen from this complexity and multiplication perspective, it is understandable that research on translation in journalism has led to the coinage of hybrid terms such as "transediting" (Stetting 1989) or "journalator" (van Doorslaer 2012), indicating the blurred borders between translating and (journalistic) authoring. In the journalistic writing process, translated texts are being "dismembered" (Orengo 2005: 170) and used as raw materials for a combination of activities such as copying, pasting, adding, deleting, and translating. The journalist in many cases functions as an invisible translator. Translation was so successfully integrated into journalism that it has even been deleted as such in the perception of readers, listeners, and viewers. Although journalists largely make use of the principles of free translation, this "highly interventionist role of journalists as translators contrasts with the very invisibility of translation within journalism" (Bielsa 2010: 45).

Obviously, these phenomena and the resulting translation-related reflection and research have become even more widespread in a context of globalisation and globalising news media. What is global "is such not because it is the same everywhere, but because it has been adapted to infinite numbers of different cultural and social contexts" (Orengo 2005: 169). This represents an essential localising function of translation in a global news environment. Translated news texts can be seen as a complex combination of summarising, paraphrasing, transforming, supplementing, reorganising, and recontextualising procedures, as a product that is "renegotiated (in terms of meaning, form and function) to respond to a new context of use" (Kang 2007: 222). Such localised translation of foreign news texts happens massively in journalism on a daily basis and is also mentioned by Pym as a legitimate case of localisation of foreign-language texts, moreover a case where the characteristics of the transformation process clearly "go beyond endemic notions of translation" (Pym 2004: 4).

Accepting the inevitability of change through translation also includes JTR attention for framing and reframing research as conducted quite extensively in communication, and more particularly in journalism studies. The processes of text production and reproduction studied in journalistic contexts obviously show many parallels with the reframing through translation. In her book, Translation and Conflict., Baker (2006) has written one specific chapter on the framing of narratives in translation. In her case, she mainly concentrates on framing as treated in the literature on social movements. This is quite a particular tradition in which framing is defined as "an active strategy that implies agency and by means of which we consciously participate in the construction of reality" (Baker 2006: 106). Renegotiating interpretations and (parts of) texts is practised daily in newsrooms all over the world. Both the journalist's and the audience's reality, as well as their social knowledge and viewpoints, are actively (re)constructed. Several strategies are used for materialising renegotiated interpretations, such as foregrounding and backgrounding, explicitness or implicitness of information, as well as selection and de-selection procedures. Such information and reconstructed information strategies often predetermine the construction potential of journalistic narratives (see van Doorslaer 2010: 182-184). In many cases, the absence of certain facts or topics is just as meaningful as their presence would be. From the point of view of the reader, the viewer, or the listener, subjects that are not included in the news coverage have not taken place or do not exist; they are not part of the news. Suppressed topics are important for the study of journalism, as they also generally reveal matters of power.

Baker's narrative frame model is also applied by Feinauer (2016), who investigates the translation of newspaper texts in South Africa, specifically from Afrikaans/English newspapers for Afrikaans/English internet news portals. Feinauer (2016: 194) detects:

a definite reframing of information for the English and Afrikaans readerships, regardless of the genre of media platform used; in other words, frame ambiguity does occur between these two readerships. For the Afrikaans readership, the reports were phrased in more neutral terms, or they were less sensational, less harsh and less negative than their English counterparts.

Very often, an ideological component, explicit or implicit, plays a role in the manipulation of the journalistic target texts. In Feinauer's study, the sensitivities of the South African past as well as the "reason for the Afrikaans media to frame post-apartheid South Africa in a more positive way" (2016: 195) are mentioned as determining ideological factors.

Absence or presence affects the centrality or non-centrality of representing specific people, events, or countries. Such localisation practices are omnipresent in newsrooms, particularly during the editing process. They are thoroughly applied to all kinds of reporting and are "heavily influenced not just by the norms of the target language, but also by the national narratives of the writers, which permeate the events themselves and offer domestic perspectives of European and world issues, altering the thematic organization of the texts", as Valdeón (2009: 149) concludes after his study on the perspectives of Euronews. Despite all tendencies of internationalisation and globalisation, domestic, regional, and especially national perspectives still have major impacts on journalistic choices and formulations. Esser (2016: 23) applies this to the TV landscape and states that the "[a]udience's viewing habits and expectations have been shaped over decades by national terrestrial broadcasters, and industry executives use the nation label for marketing purposes at international TV markets, speaking of 'Danish drama' [...] or 'Japanese animation'". Explaining media landscapes in mainly national categories is in itself a construction and does not correspond to our societal complexities. On the other hand, researchers cannot but take into account the existence of this dominant categorisation principle when analysing localisation phenomena.

At whatever level, these perspectives also co-determine the underlying values, norms, and explanations. Under such circumstances, a journalist-translator almost necessarily shapes narratives - sometimes consciously, but most often unconsciously. Newsroom workers are inevitably embedded in translation and information transfer, and they embed or fit their messages according to the norms that are either dominant or aimed at. Because of the centrality of national categories in our world presentations, national or cultural images will also have impacts on the rewriting and reformulation processes as well as on the coverage about countries and nationalities. This brings the potential importance of imagology in JTR into the picture.

2. Imagology and JTR

With reference to Baker, Feinauer (2016) states that human knowledge can always be considered as narrative in nature and representing a particular perspective. Therefore, there "is no neutral ground, no neutral knowledge and consequently no neutral translation. Every translation is in one way or another a re-narration and a re-telling of the source text" (Feinauer 2016: 170). When ideological positions play a role in this perspectivisation and re-narration process, the construction of "self and "other" in (journalistic and other) text writing constitutes an outstanding field of illustration.

Over the past decades, such forms of self- and other-representation as well as national and cultural image-building in texts have been studied by imagology. Although the roots of imagology lie in literary studies, as a specialisation of comparative literary research (see for instance Beller 2007: 7), over the past decade there is a clear extension to other types of discourse, such as journalistic texts. Imagological approaches study and theorise national and cultural stereotypes from a transnational and comparative point of view, in particular discursive articulations of national, cultural, or ethnical characterisations called "ethnotypes".

This should not be confused with a theory of national or cultural identity. Imagology does not study what nations or nationalities are; it concentrates on how they are discursively represented. From a historical point of view, terms such as "nation", "people", or "identity" are clearly charged. Therefore, imagological approaches explicitly focus on constructionist models and distance themselves from essentialist definitions. Despite all globalisation and internationalisation trends, it is difficult to deny that a considerable part of people's views of the world is dominated by national and cultural categorisations that are adopted as a criterion for categorising human knowledge, human activity, and cultural practices. Leerssen (2016: 14) notes that "[a]longside gender, ethnicity and nationality are perhaps the most ingrained way of pigeonholing human behaviour into imputed group characteristics". Also, the researcher's point of view has to take this into account when analysing reality. Therefore, imagology has to be seen as descriptive rather than explanatory, for "it is the aim of imagology to describe the origin, process and function of national prejudices and stereotypes, to bring them to the surface, analyse them and make people rationally aware of them" (Beller 2007: 11-12).

In TS, Lefevere is often referred to as the main scholar who related translation to forms of rewriting (Lefevere 1992). It is less known that he also explicitly connected that rewriting process to the image-creating power.

In the past, as in the present, rewriters created images of a writer, a work, a period, a genre, sometimes even a whole literature. These images existed side by side with the realities they competed with, but the images always tended to reach more people than the corresponding realities did, and they most certainly do so now. Yet the creation of these images and the impact they made has not often been studied in the past, and is still not the object of detailed study. This is all the more strange, since the power wielded by these images, and therefore by their makers, is enormous.

(Lefevere 1992: 5)

Although Lefevere associates such image-building power with literary situations and contexts, it can be paralleled with journalistic discourse as well, since several of the characteristics he describes are also present in journalistic production (see van Doorslaer 2012). This is clearly the case for the producer of the text, where Lefevere writes that the images constructed by such rewriters play an important and powerful role in societies. Another parallel can be drawn with the reception of journalistic texts. When readers of literature say they have read a book, for Lefevere (1992: 6) this means "that they have a certain image, a certain construct of that book in their heads". Similar reception and construction processes take place when readers, listeners, or viewers of journalistic text production read, hear, or see representations of nationalities, countries, or cultures. When Lefevere (1992: 8) states that "rewriters adapt, manipulate the originals they work with to some extent", this also seems perfectly valid for a similar text construction process as in journalistic rewriting. Imagological research in literary studies has given ample evidence of the richness of literary discourse with regard to image building. The importance of literary canonicity strengthens the perception and value of ethnotypes. However, in our modern media world, the omnipresence of journalistic discourse plays an equally canonising role with the use of different means. The feature of constant repetition of certain (national and cultural) stereotypes in the media may achieve an effect similar to canonisation in literature.

Another TS author who establishes a clear link between image building and translation is Kuran-Burcoglu. She attributes an initiating, a formative, as well as a transforming role to translations as far as image construction is concerned (Kuran-Burcoglu 2000: 144-145). In addition, she distinguishes between three levels or stages at which image building can have an impact: the stages of text selection, of the encoding process, and of the reception process. Similarly, these levels could be distinguished for journalistic texts and image construction. Chew can also be referred to as regards his statement that "the potential sociocultural and, indeed, political benefits of image studies for the field of language and inter-cultural communication can hardly be exaggerated" (Chew 2006: 186). From a more interdisciplinary perspective asking how exactly to connect disciplines such as TS with imagology, van Doorslaer (2019: 64) states that "imagological approaches will probably remain fruitful for future research on all types of text modification, including translation".

Obviously, journalism studies scholars have also produced a considerable amount of research on representation, which sometimes has important features in common with the study of stereotypes. This is illustrated here with just a few examples explicitly relating representation to the construction of national or cultural auto- and hetero-images, as they are generally called in imagology. An auto- or self-image refers to a reputation within the same group, while a hetero-image expresses the opinion that others have about characteristics of a different group. One example connecting representation with discourses of identity and self-other rhetoric is Le (2006). Li (2012) focuses on the framing of China and the United States on Australian television and notes that "the media shape public opinion about any country's reputation" (2012: 186). It is one of the constants in imagological research that there exists a whole bandwidth of images and counter-images for countries, cultures, or nationalities. That whole range is called the underlying "imageme" (Leerssen 2016: 18). These mental images often contradict one another, as such showing their constructed nature. Li's findings confirm that element of continuity compared to earlier images about China in Australia. At the same time, the imageme is flexible enough to allow the creation of new elements and partly new images (Li 2012: 203). Feinauer (2016: 168) gives the example of a paper presented by Chen in 2009 in which he investigates the construction of "self and "other" in the transediting of news texts that are related to political conflicts. Centuries-old clichés can often also be found in travel journalism, a very productive genre for national and cultural stereotyping. Van Doorslaer (2021) describes several examples of the relevance of travel writing for imagological research: from the development of the image of Spain in travel writing through the centuries, over British colonial narratives including image constructions, up to more extended examples of contemporary travel journalism about South Africa in Dutch-language sources.

The case study presented below also deals with South Africa. Unlike Feinauer's case study, it is not based on a narrative frame model, but starts from an imagological perspective. It investigates how journalistic discourse in current Dutch-language newspapers (both from the Netherlands and Belgium) represents South Africa(ns). The Dutch-language area is chosen because of the historical cultural links through Afrikaans. At the same time, it starts from the national category of "South Africa", with its multitude of cultures, races, and languages. As explained before, international journalism mainly thinks and describes in national, not regional or continental, categories. Paradoxically, this example also shows the relativity of the so-called "national" categorisation. In the case of South Africa, the country category is actually not national, but overtly multinational.

3. Case study

3.1 Corpus selection

The database used for this analysis is Nexis Uni, which is the new name for the former LexisNexis Academic since 2017. It is an international database of newspapers and magazines also covering the Dutch-language media, both in the Netherlands and Flanders - the Dutch-language part of Belgium. As we are interested in the discursive presentation of South Africa(ns) in current journalistic discourse, we selected the whole year of 2019 for the category of newspapers. The first search term for the country name "Zuid-Afrika" produced 7842 hits in Dutch-language newspapers in 2019. As country names often appear in purely descriptive contexts without any imagological relevance, we subsequently decided to focus on the people and the adjectives. The combination of the search terms "Zuid-Afrikaan" (citizenship), "ZuidAfrikanen" (its plural), "Zuid-Afrikaans" (adjective), and/or "Zuid-Afrikaanse" (its declined form) produced a total number of 3931 hits for the year 2019. The quantitative analysis was based on this corpus of 3931 articles.

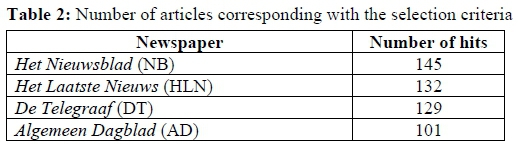

For the qualitative textual-imagological analysis, out of the larger corpus we selected the newspapers with the highest print runs in the respective countries: De Telegraaf (DT, 386.000) and Algemeen Dagblad (AD, 341.000) in the Netherlands, and Het Laatste Nieuws (HLN, 275.404) and Het Nieuwsblad (NB, 246.610) in Flanders1. As the data of AD were not included in the Nexis Uni category of "Newspapers", it was only in this case we had to make use of the category "Web-based publications".

3.2 Quantitative data analysis

Nexis Uni has itself categorised all news items thematically, with the articles often belonging to one or more (sub)categories. In alphabetical order, the categories are:

• Business News, including the subcategories Business Reports & Forecasts, Company Activities & Management, Economy & Economic Indicators, Financial Market Updates, and Trade & Development;

• Crime, Law Enforcement & Corrections, including the subcategories Human Rights Violations, Law Enforcement, Crimes against Persons, and Sex Offenses;

• Government & Public Administration, including the subcategories International Organizations & Bodies, Public Finance, Government Departments & Authorities;

• Humanities & Social Science, including the subcategories Literature, Visual & Performing Arts, and Writers;

• Medicine & Health, including the subcategories Diseases & Disorders, Medical Science, and Public Health;

• Population & Demographics, including the subcategories Demographic Groups, and Population Characteristics;

• Science & Technology, including the subcategories Astronomy & Space, Ecology & Environmental Science, Life Forms, and Medical Science;

• Society, Social Assistance & Lifestyle, including the subcategories Associations & Organizations, Communities & Neighborhoods, Death & Dying, Drugs & Society, and Race & Ethnicity;

• Sports & Recreation, including the subcategories Sports & Recreation Events, Sports & Recreation Facilities & Venues, Sports Regulation & Policy, and Sports, Games & Outdoor Recreation;

• Trends & Events, including the subcategories Corruption, Festivals, Holidays & Observances, and Tournaments.

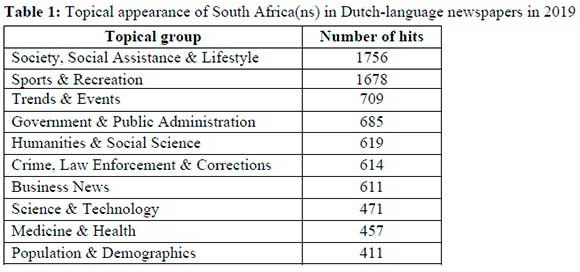

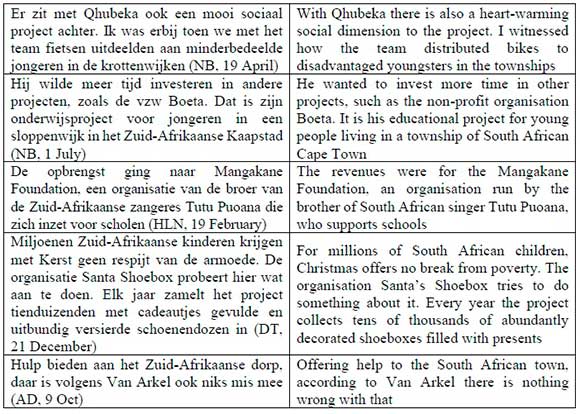

For this quantitative part, we make use of the Nexis Uni categories. We are aware that other categorisers may have worked partly along different lines and might have grouped articles here and there in other categories. Unlike a more thorough qualitative analysis, counting is more superficial and can lack nuance. Nevertheless, we believe that the importance of this quantitative analysis is mainly to distinguish larger tendencies about the topics South Africans are being related to in Dutch-language newspapers. Such trends are discernible in the following table, presented in descending order of quantitative importance.

The 10 Nexis Uni overarching topical categories are too general for an in-depth interpretation. Nevertheless, it might at least have an indicative value that social, lifestyle, or sports topics appear three to four times more often than health or science issues. Having a closer look at the different subcategories sometimes makes the interpretation options more concrete. The broad Society category, for instance, also includes subcategories such as Drugs & Society or Race & Ethnicity. These rough data and tendencies will now be refined by narrowing them down to a more focused and imagologically relevant selection in the articles of the four newspapers under qualitative study.

3.3 Qualitative data analysis

As indicated by Leerssen on several occasions (most recently in 2016), an imagologically relevant analysis always requires a combination of a textual, a contextual, and an intertextual level. These three levels can only be detected and connected through a qualitative analysis. The textual analysis focuses on the topic and the degree of foregrounding. At the contextual level, social, political, or historical circumstances are taken into account. The intertextual level shows that stereotyping is the result of multiple occurrences of textual instances. A single occurrence has no imagological value in itself. We realise that the corpus in this limited case study lacks a diachronic component. Historical sequence would raise the imagological importance, but cannot be measured within the set-up of this article. Nevertheless, the repetitive character of certain features and associations exceeds the value of a single national or cultural characterisation. The degree of typicality is necessarily limited with this type of corpus, but can serve as a basis for later comparisons with other and/or larger corpora.

Based on the criteria and search terms indicated above, we found a comparable number of hits in the four newspapers. In general, the two Flemish newspapers produced slightly more articles corresponding with the selection criteria. This might be explained by the fact that - at least in our corpus - the average length of the articles in HLN and NB was shorter than in DT and AD.

Subsequently, we selected all passages that expressed a potential of typicality for "South African" (both adjective and noun). This part of the investigation is the least exact activity, as typicality is experienced in a partly subjective way. Inevitably, it is also related to certain recurring themes or topics. In this sense, selection criteria or selection appreciations for typicality are partly related to topicality. The analysis of all selected passages shows that in the corpus we mainly find five recurring topics that are related to characterisations of "South African". We present them here in descending order of frequency.

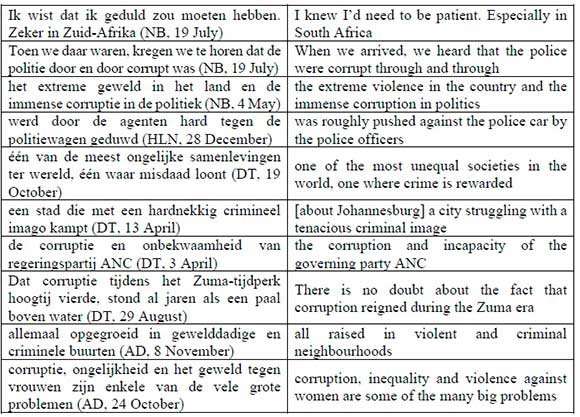

3.3.1 Malfunctionings

The characteristic that is by far most dominant in numbers, up to three times more than the second one, is the presentation of South African authorities as not functioning properly. This category shows how difficult it sometimes is to distinguish a "general" characteristic. It mostly refers to politicians, in particular several times to former president Jacob Zuma, but is also extended to the police and to other official and institutionalised instances - often materialised through descriptions of corruption and/or violence. Because of the official character and the repetition of these features, such descriptions contribute to the idea of representativeness. At the same time, they show that signification and interpretation are also partly in the eye of the beholder. From a different ideological perspective, it is not impossible to interpret this mainly as a social and power clash between the authorities and the South African "people", or as a consequence of social inequality. Nevertheless, the frequent descriptions of official wrongdoing are facts of journalistic discourse. To illustrate this, I present here a selection of examples with their translations in English2.

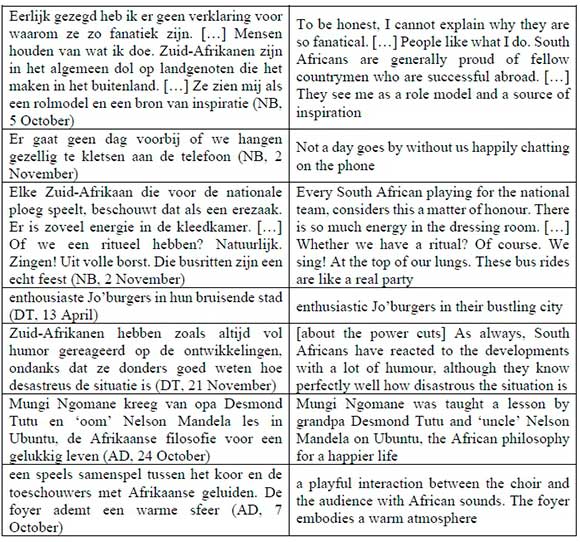

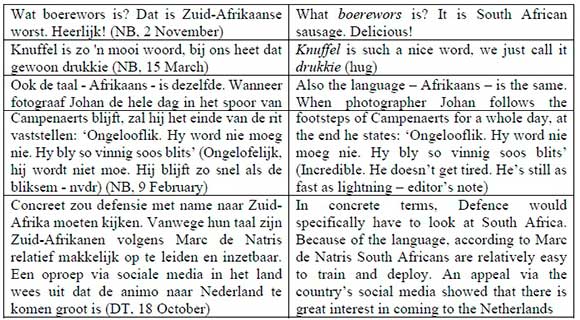

3.3.2 Enthusiasm and cheerfulness

Interestingly, the second characteristic seems to represent a contradictory attitude. Instead of being dominated by corruption and violence, (some) South Africans are presented as enthusiastic, cheerful, smiley, warm-hearted, and full of humour. Sometimes this is connected to being enthusiastically proud of a successful fellow countryman. This is mainly the case in the Flemish newspapers, where in 2019 several articles appeared about Percy Tau, a South African soccer professional playing in Belgium, but also for the South African national team. The social media of his Flemish team Club Brugge suddenly noticed a huge increase of passionate, sometimes fanatic followers from South Africa. The positivism in life is presented as South African in general, although sometimes explicitly related to multiculturalism, the black communities, or "African" happiness. Some of the examples in the table below come from an interview with Percy Tau. In this case, it is partly an auto-image of a South African about South Africans. Nevertheless, the mere selection of this characteristic by the Dutch-language journalist includes a hetero-image dimension as well. Every representation of an interview is itself based on foregrounding and deselection of information. The paradoxical character of this feature is most obvious when the humour is presented as a reaction to malfunctionings, such as the frequent power cuts in South Africa. In these cases of rather wry or black humour, the two first categories shown here are closely intertwined.

3.3.3 Social needs (and benevolence)

This topical field connects one aspect belonging to the topic of malfunctionings (see section 3.3.1), the social needs and the poverty, to what is essentially the construction of an auto-image by the target culture, in this case the Dutch language area. Quite frequently, the corpus mentions social projects for South Africans, often initiated by Dutch or Flemish citizens. This is highly interesting from an imagological point of view, as the hetero-image (South Africans as poor people needing help) in this case interacts with the Dutch or Flemish constructed auto-image of benevolent, good people.

3.3.4 The "cute" language

It could be hypothesized for further research that the benevolence from Dutch speakers is not only more present for South Africa than for other, often poorer countries, but also that this higher frequency is related to the historical connections, in particular the language relations with Afrikaans - derived from the language of the original Dutch settlers, and as such with clear historical connections to Dutch. When writing about South Africans, mainly Flemish journalists regularly enhance or illustrate their articles with an Afrikaans language word, preferably when it is understandable for the Dutch-language readers, but experienced as slightly awkward or cute. In combination with the previous field, this one shows how poly-interpretable the concept 'South African' potentially is, ranging from poverty and social needs to a historical and cultural bond through one of the languages.

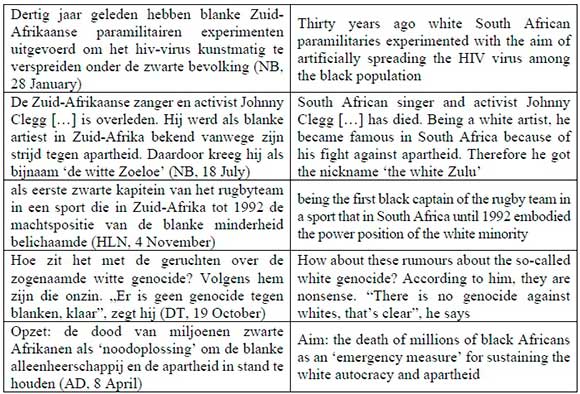

3.3.5 Racial tensions and the apartheid past

The smallest of the five fields is the one that refers to the tensions between the different races and the military apartheid past of South Africa. The topic is mainly dealt with because of an English-language documentary that was shown on television in 2019. Through this presentation choice, the journalists themselves seem to consider this image as less relevant or less desirable for 21st-century South Africans.

4. Conclusion

The articles in the corpus are very often based on interlingual translation, obviously. The reality in most Dutch-language newsrooms is that international news is based to a great extent on English-language sources of international press agencies. As explained earlier in this contribution, such texts are then partly translated, adapted, localised, and recontextualised, a process which makes the original source text(s) if not invisible, then at least very hard to trace (see Davier and van Doorslaer 2018). Taking this into account, this contribution has not aimed at studying interlingual textual transfer, but has concentrated on the target language and target culture discursive products. The aim was to know which images of South Africa(ns) appeared in current journalistic discourse in the Dutch-language area, how they were selected, and how they were presented.

Essential in the process of looking for imagological relevance in the target texts is the repetition of certain features and contexts. Typicality, in this case, is more of a narrative constructed and created through discourse than directly referring to reality. This is shown in the five main topical (and typical?) fields that we could deduce from the corpus. In imagological terms, all five fields together build the imageme, i.e. the range of possible images journalists and other rewriters can draw on. It confirms earlier imagological findings that for every country or nationality, there are contradictory images and options available. "Typically South African" can apparently be presented as violent and corrupt, as suffering under violence and corruption, as enthusiastic, warm-hearted and full of humour, as humorous because of the hopeless situation, as in high social need, as culturally interesting because of the language bonds, as determined by racial tensions and the apartheid history, as multiculturally cheerful, etc.

All these characteristics can be found several times in this relatively limited corpus of journalistic texts. It shows that national image presentation is not about truth, because all of these features are both true and not true. The journalistic presentation of the national and cultural image is about selection and deselection, and about framing through translation, as illustrated in Feinauer's (2016) contribution. "Afrikaans" can be presented as cute and related, or conversely as harsh when associating it with apartheid. "African" can be presented as dynamic and joyful, or as corrupt and violent. Particularly in international journalism, translation is yet another filter for the expected reframing, localisation, and recontextualisation.

Similar further research could add a diachronic dimension to the present corpus. That would refine the imagological relevance of the representation of South Africa(ns) not only in 2019, but also in different years and eras. From a journalism studies point of view, it would add value to have a closer look at the representation differences between Dutch and Flemish newspapers. The Netherlands and Belgium have conducted partly different policies towards South Africa, both culturally and politically. It would be interesting to see to what extent there is a correlation between these different official policies, on the one hand, and the ways in which national and cultural images were represented in the respective media, on the other. Furthermore, the findings of this contribution could be compared to the ways in which South Africa is trying to improve its image through nation branding, as well as the effectiveness or non-effectiveness of those attempts when related to foreign newspaper presentations.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the University of Tartu Astra Project Per Aspera and grant number PHVLC19917.

References

Baker, M. 2006. Translation and conflict. A narrative account. London and New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Beller, M. 2007. Perception, image, imagology. In M. Beller and J. Leerssen (eds.) Imagology: The cultural construction and literary representation of national characters - A critical survey. Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi. pp. 3-16. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004358133 [ Links ]

Bielsa, E. 2010. Translating news: A comparison of practices in news agencies. In R.A. Valdeón (ed.) Translating information. Oviedo: Universidad de Oviedo. pp. 31-49. https://doi.org/10.7202/1023822ar [ Links ]

Chew, W.L. 2006. What's in a national stereotype? An introduction to imagology at the threshold of the 21st century. Language and Intercultural Communication 6(3-4): 179-187. https://doi.org/10.2167/laic246.0 [ Links ]

Davier, L., C. Schäffner and L. van Doorslaer (eds.) 2018a. Methods in news translation. Special issue of 'Across Languages and Cultures' 19(2): 155-292. https://doi.org/10.1556/084.2018.19.2.1 [ Links ]

Davier, L., C. Schäffner and L. van Doorslaer. 2018b. The methodological remainder in news translation research: Outlining the background. Across Languages and Cultures 19(2): 155-164. https://doi.org/10.1556/084.2018.19.2.1 [ Links ]

Davier, L. and L. van Doorslaer. 2018. Translation without a source text: Methodological issues in news translation. Across Languages and Cultures 19(2): 241-258. https://doi.org/10.1556/084.2018.19.2.6 [ Links ]

Esser, A. 2016. Defining 'the local' in localization or ' adapting for whom?' In A. Esser, M.Á. Bernal-Merino and I.R. Smith (eds.) Media across borders: Localizing TV, film and video games. New York and Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 19-35. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315749983 [ Links ]

Feinauer, I. 2016. Are South African print newspaper narratives reframed for Internet news portals or not? Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus 49: 167-197. https://doi.org/10.5842/49-0-685 [ Links ]

Kang, J-H. 2007. Recontextualization of news discourse. The Translator 13(2): 219-242. [ Links ]

Kuran-Burcoglu, N. 2000. At the crossroads of translation studies and imagology. In A. Chesterman, N. Gallardo San Salvador and Y. Gambier (eds.) Translation in context: Selected contributions from the EST Congress, Granada, 1998. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. pp. 143-150. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.39.16kur [ Links ]

Le, E. 2006. The spiral of 'anti-other rhetoric': Discourses of identity and the international media echo. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.7202/018724ar [ Links ]

Leerssen, J. 2016. Imagology: On using ethnicity to make sense of the world. Iberic@l: Revue d'études ibériques et ibéro-américaines 10: 13-31. [ Links ]

Lefevere, A. 1992. Translation, rewriting, and the manipulation of literary fame. London and New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Li, X. (Leah). 2012. Framing China and the United States: The Australian Broadcasting Corporation's current affairs television programming at the start of the twenty-first century. In J. Clarke and M. Bromley (eds.) International news in the digital age: East-West perceptions of a new world order. New York and Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 186-207. [ Links ]

Orengo, A. 2005. Localising news: Translation and the 'global-national' dichotomy. Language andIntercultural Communication 5(2): 168-187. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708470508668892 [ Links ]

Pym, A. 2004. The moving text: Localization, translation and distribution. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Stetting, K. 1989. Transediting: A new term for coping with the grey area between editing and translating. In G. Caie (ed.) Proceedings from the Fourth Nordic Conference for English Studies. Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen. pp. 371-382. [ Links ]

Valdeón, R.A. 2009. Euronews in translation: Constructing a European perspective for/of the world. Forum 7(1): 123-153. [ Links ]

Valdeón, R.A. 2015. Fifteen years of journalistic translation research and more. Perspectives 23(4): 634-662. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676x.2015.1057187 [ Links ]

Van Doorslaer, L. 2010. The double extension of translation in the journalistic field. Across Languages and Cultures 11(2): 175-188. https://doi.org/10.1556/acr.11.2010.2.3 [ Links ]

Van Doorslaer, L. 2012. Translating, narrating and constructing images in journalism: With a test case on representation in Flemish TV news. Meta: Translators' Journal 57(4): 1046-1059. https://doi.org/10.7202/1021232ar [ Links ]

Van Doorslaer, L. 2019. Embedding imagology in translation studies (among others). Slovo: Baltic Accent 10(3): 56-68. https://doi.org/10.5922/2225-5346-2019-3-4 [ Links ]

Van Doorslaer, L. 2021. Stereotyping by default in media transfer. In J. Barkhoff and J. Leerssen (eds.) National stereotyping and identity politics in times of European crises. Leiden and Boston: Brill. pp. 205-220. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004436107 [ Links ]

1 The print runs of newspapers have been declining rapidly over the past years. For the Dutch newspapers, the figures refer to 2017 (source: https://www.ocwinciifers.nl/cultuur-media/media/landeliike-en-regionale-dagbladen, consulted on 6 February 2020). The Flemish newspapers recently prefer to publish their outreach numbers, i.e. the number of people they reach. The figures mentioned in the text are the print- and digital-run numbers of 2015 (source: https://www.tijd.be/ondernemen/media-marketing/alleen-de-tud-de-morgen-en-l-echo-verkopen-meer-kranten/9760810.html, consulted on 6 February 2020).

2 In this contribution, all English translations of the Dutch newspaper passages are produced by the author.