Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus (SPiL Plus)

On-line version ISSN 2224-3380

Print version ISSN 1726-541X

SPiL plus (Online) vol.59 Stellenbosch 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.5842/59-0-830

Interpreting research in South Africa: A bibliometric study

Herculene Kotzé

Translation and Interpreting Studies, School for Languages, Potchefstroom Campus, North-West University, E-mail: herculene.kotze@nwu.ac.za

ABSTRACT

After South Africa's transition to democracy in 1994, there was an expectation that problems related to translation services would receive more attention, especially given the fact that 11 languages received official status after 1994 (Lubbe 2002:78). In addition, the call to transform and decolonize South Africa has led to widespread discussion regarding which steps need to be taken to strengthen the African perspective in higher education. Kotzé and Wallmach (forthcoming) offer an in-depth look at research trends on interpreting in South Africa for the period 2006 to 2016. They highlight that, in order to transform South African interpreting studies, it is essential to know what has already been researched and, going forward, what we can learn from publication trends on interpreting.

By using a systematic literature review (Fink 2005), this bibliometric study investigates the trends of interpreting research done in South Africa, from the first publication found in 1968, through to 2017. The findings from this study will be of value to current and future interpreting researchers in that they will highlight current trends and shortcomings in South African interpreting research, and contribute to understanding and solving issues of transformation within this specific field.

Keywords: Interpreting, interpreting research, bibliometrics, counts of publication, South Africa

1. Introduction: Developing IRSA

Interpreting Research in South Africa (IRSA) is a database that I created. It currently consists of 254 publications specifically on interpreting, which were produced in South Africa or by South Africans, from 1968 to 2017. The reasoning behind developing this database was to create a tool that would provide information on the research that has been conducted on interpreting in South Africa or by South Africans. Simply put, I wanted to know what South Africa has contributed to interpreting studies. According to Van Doorslaer (2016: 17), the time is ripe for a study of this nature: "After more than half a century of scholarly research, T&I Studies has reached a stage at which it is worthwhile investigating developments, tendencies, and differences within the discipline". A database on interpreting research in South Africa, if developed and maintained properly, would offer a number of benefits, including retrospective contextual analyses of themes which would inform local future teaching and research.

In order to test the feasibility of this undertaking, Kotzé and Wallmach (forthcoming) conducted a pilot study for the period 2006 to 2016. They found that South African research on interpreting studies follows broad international trends, mainly from Europe. Furthermore, very few original theoretical position papers - which would ultimately influence the discipline as a whole - were produced, and there is a clear lack of ethnographic work which could demonstrate the impact of South African interpreters on historical events. Another trend identified was the preference to publish in English only. This trend is particularly problematic given South Africa's multilingual context, and one would expect - especially in the field of translation studies - an increase in multilingual publications. I state this because, in South Africa, academics are not only involved in producing and disseminating knowledge, it is also common practice for us to engage with our findings in a very practical way, for instance, supporting multilingualism by producing articles in languages other than English.

These findings were sufficient reason to broaden the investigation to everything that has been published on interpreting in South Africa, with the objective to provide a comprehensive view of the development of research and publications in this field.

Van Doorslaer (2016: 168) states that bibliometric studies, such as the one this article reports on, have become more than simply a method of investigation. He quotes Grbic' (2013: 20) as saying it could even be seen as "an empirical branch of the social studies of science". Van Doorslaer continues to say that the recent success of bibliometric studies can be attributed to the quantification of research output, a trend - with roots in information science - now also seen in the humanities. Methods used in bibliometric studies, such as counts of publications, allow for the measuring, quantitative studying, and investigation of academic literature and its impact (impact can relate to discipline, sub-discipline, specific publications, individual researchers, or research groups; Van Doorslaer 2016: 168). Also applied as part of scientometric studies, which developed from the early work of Price (1963/1965) and Garfield (1994, 2000/1955), counts of publications have many applications. According to Grbic and Pollabauer (2008: 91-92), counts of publications can provide information on scholarly processes such as publication growth rates, the evolution of a discipline, and the relationships among research areas, to name a few. Depending on the focus of the study, counts of publication can provide insight into individual researchers, research groups or teams, projects, institutions, disciplines, and regions or countries. These, if categorised, can be grouped into micro (individual research), meso (group research), or macro (national output by country, region etc.; Grbic and Pollabauer 2008: 91). Furthermore, Borgman (1990: 15-17, 2000: 146) defines the variables that can be studied in scientometrics and uses the term "artefacts" to refer to publications such as articles, books, conference papers, journals etc. In light of the above, the current study focuses on publications on a macro level.

2. Background

Multilingualism in South Africa is protected by the Constitution of South Africa (1996) by recognising 11 official languages and, in doing so, the right of each South African to practise their language and culture. As Webb (1999: 352) states: "the 11-language decision is thus a bold (and possibly unique) initiative to address the manifold challenges of a complexly multilingual and culturally diverse country". Unfortunately, little has come of the ideals this policy promises (Webb 1999: 352, Bornman et al. 2017: 731). Webb (1999: 353) affirms this when he says: "Despite all these formal decisions and all the supporting work by linguists, very little has changed on the African language political scene in any meaningful way", and argues that a mismatch exists between language policy and linguistic realities. Recent developments on this scene may, however, change this reality.

In 2012 and 2014 respectively, the Use of Official Languages Act (Act 12 of 2012) and the South African National Language Practitioner's Council Act (Act 8 of 2014) were adopted in South Africa. Both acts provide the opportunity to move the profession (especially that of interpreting) forward as they make provision for the regulation of the profession and the development of training programs for interpreters and research recommendations. This offers the profession some hope in light of the fact that, prior to these dates, interpreting (especially in the public domain) was of poor quality (cf. Moeketsi 1999, Pienaar 2006).

In contrast to these claims that doubt the practice of interpreting, "robust research is conducted" on interpreting in South Africa (Pienaar and Cornelius 2016: 189). However, after a short overview of interpreting research in South Africa to support this statement, Pienaar and Cornelius come to the conclusion that recommendations from said research is often not implemented. The authors illustrate this conclusion with the following specific observation: "One example is the fact that the public and media galleries in the Gauteng Provincial Legislature are still not equipped with earphones as suggested as long ago as 2000" (Pienaar and Cornelius 2016: 189). The fact that research is not implemented in the fields where it can and should be may be why interpreting quality in the public domain remains poor.

The above findings raise many questions, one of which relates directly to the current research question: What research has been done on interpreting in South Africa? In order to answer this question, an in-depth study ensued on this topic, and the methods and results follow.

Grbic and Pollabauer (2008: 91-99) provide a thorough overview of counts of publications (or, as termed by them, "publication counting"). In terms of strengths, they argue that publication counting relies on few assumptions, making it a fairly straightforward method, and that it is useful for longitudinal studies of trends due to the availability of large datasets. To address the limitations of data gathered from bibliographic databases, most quantitative studies add items that are not as easily obtained as basic bibliographic information. These include the nature of the publications, the text type, the language of publication, keywords, and affiliations of authors, a few of which were included in this investigation in addition to a number of others which will be discussed later.

A number of investigations in translation and interpreting studies have been conducted using bibliometric methods which offer useful results (cf. Van Doorslaer 2016: 171-172), but Van Doorslaer also concedes that these methods do have their limitations. Firstly, a purely quantitative approach may overlook the value that qualitative data could add in terms of uniqueness, and the results of data-based methods depend solely on the reliability of the data. If it is true that a properly defined and selected corpus will offer incisive results, it stands to reason that the converse will also be true - that poorly defined and selected data could offer misleading results (Van Doorslaer 2016: 173). In order to account for the latter, specific steps were taken to ensure the database was as reliable as possible, and are discussed in the following section.

3. Research method and analyses

Creating the IRSA database entailed a number of steps. The initial step of this bibliometric study was completing a systematic literature review (SLR). This is a stand-alone literature review that is conducted using a systematic, rigorous standard (Okoli and Schabram 2010: 2) which will be discussed next. The primary data used for this SLR is existing publications on interpreting in South Africa. According to Okoli and Schabram (2010: 6-7), there are a number of steps that need to be followed to successfully produce a SLR, and are summarised below.

The first step is to determine the purpose of the literature review. Hereafter, the necessary steps need to be taken to ensure that everyone involved in the study has access and training to use the required software. The analyses were done using MS Excel, and building the database was done in Zotero (https://www.zotero.org), a free bibliographic tool that stores publication information. Adding publication information entails selecting the type of entry to be made (this includes various options such as journal articles, magazine articles, postgraduate studies etc.) which will then provide a screen containing the relevant fields to that particular type of publication, for instance, the name of the publication, the language of the text, or other details relevant to that particular type of publication. There are also options to add an electronic version of the publication in question and to create a timeline, the latter providing a useful extensive view of the data.

Comprehensive literature searches were subsequently conducted to justify the comprehensiveness of the searches. Data for the pilot project (Kotzé and Wallmach, forthcoming) was initially collected by means of database searches on two different occasions in 2017. Readily available academic search engines were utilised, including NEXUS (the National Research Fund's database of current and completed dissertations and theses), SAePublications (South African electronic Publication database), National ETD (database of digital dissertations and theses), ISAP (Index of South African Periodicals), and OneSearch (a comprehensive search engine that covers all of the above and has the capacity to find items that are not stored in the previously mentioned databases). The time frame for the pilot investigation was limited to the 10-year period between 2006 and 2016.

During the first reading of the search reports emanating from the pilot investigation, a number of complications were encountered. Firstly, the project aimed to investigate what has been published on interpreting in South Africa. However, the data quickly indicated that, although written by South African scholars, some items were published in international journals. The scope of the project was therefore widened to include publications in international sources if written by or in collaboration with one or more South African scholars. A limitation of the study however remains that, although every attempt was made to develop the database as thoroughly as possible, the database may never be complete, and the possibility exists that more publications on interpreting in South Africa and/or produced by South Africans have yet to be located.

Another complication that arose was that, based on our knowledge of the field, we realised that these literature searches did not deliver all the publications we knew had been written on interpreting and interpreting-related topics in South Africa or by South African interpreting scholars. Although it is not possible to account for the reasons why the investigation did not discover everything it should have, it was possible to attempt to fill these gaps in other ways: both researchers carried out various individual searches and compared findings; both researchers approached colleagues and well-known scholars who publish on translation and interpreting studies, and requested their publication information (including details of postgraduate studies that they had been involved in as supervisors); and these colleagues and scholars were also asked to send our request for information to colleagues in their networks who may have published on interpreting or interpreting-related topics. After the set deadline for information had been reached, and all the data was added to the database, the dataset comprised 115 entries including both accredited and non-accredited articles, books, PhD theses, Master's dissertations, and Honours dissertations.

At the beginning of 2018, another intensive round of literature searches was conducted in order to firstly confirm that no publications were excluded during the first, second, and third rounds of data collection, and to include publications which were published more recently than the latest round of searches. The database currently consists of 254 publications, specifically on interpreting, which were produced from 1968 to 2017, and publications are added to it as they become available.

The next step in the process is practical screening, which requires that researchers are explicit about what was included and what was not included in the database. Items included for this study are as follows: . journal articles; books; book chapters; PhD-, DPhil-, and DTech theses; Master's-, MPhil-, and MTech dissertations; Master's research reports; Honours dissertations and mini-dissertations; magazine articles1; and reports2. No type of publication was excluded so as to produce as comprehensive as possible a review3.

Screening for exclusion must also be done. This process implies that a justification is required for the decision to exclude a publication on the basis of quality. As was the case with the pilot study, the goal was to offer a database that was as comprehensive as possible, and no contributions were excluded on the basis of quality.

Once the data was collected, the metadata was extracted manually in MS Excel and carried out with the support of a code guide that was created before the data was analysed, and adapted during the process of coding. The code guide made use of seven code groups: type of publication, language of publication, context, point of departure, mode of interpreting, and methodology and relevant codes attached to each group.

The completion of the SLR was followed by reporting on the findings and building the database. This database was, as stated previously, developed using Zotero which included added electronic copies of articles if they were available. However, in an age where having access to data electronically is becoming increasingly common, a surprising hurdle encountered during this study was access to data. Of the 254 publications found on interpreting in South Africa, 46 were not available electronically and hard copies were virtually impossible to get hold of. Knowledge of their existence is based solely on citations and references in other publications. Their unavailability necessitated removing them from the data analysed for this study because not being able to read the full text meant that these publications could not be analysed for the required metadata. However, every attempt is still being made to locate copies of these publications to include them in the database.

The last step of the process was coding the data inductively in Excel with the aid of a coding guide, and analysing the results for trends. The metadata extracted fall under seven headings: Type of Publication, Language of Publication, Context, Point of Departure, Language Combination, Mode of Interpreting, and Methodology. The results are discussed in the following section.

4. Findings

The following section contains the findings of the quantitative data analysis, presented in figures, with each figure followed by a discussion.

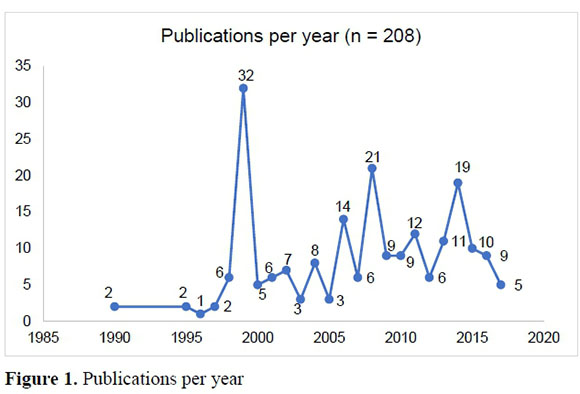

Figure 1 is a graphic representation of the number of publications produced per year over the period under investigation. There seems to be a constant rise and fall in research on interpreting, and a few years stand out in terms of publications. One of the types of publications produced is in the form of book chapters, which explains the spikes on the graph as all these items appear in one book. The largest spike is also evident shortly after democracy, which may relate to the country's official language policy - which made provision for the use of 11 official languages, thus necessitating the use of language practices such as interpreting - being adopted.

As Figure 1 shows, very little was done by the early 1990s and then, around the transition to democracy, interpreting became a topic which drew a lot of academic and research attention, and a number of journal articles were published. A book, Liaison Interpreting in the Community (Erasmus 1999), was published in 1999 and contained a number of chapters on interpreting in South Africa (a few postgraduate studies were also completed). This is indicated by the first large spike on the graph. One could deduce that the reason for this publication is related to the country's adoption of a new language policy, which offered a plethora of research possibilities for language practitioners and academics alike, a result of which was the publication of this book.

Later on, during the early 2000s, a few postgraduate studies focused on aspects of interpreting, and various journal articles were published. In 2008, another book entitled Multilingualism and Educational Interpreting (Verhoef and du Plessis 2008) was published, and contained a number of locally authored chapters. By the early 2000s, interpreting had become an established method of addressing the challenges of multilingualism. Therefore, one can conclude that researchers and students remained interested in issues regarding interpreting, and research outputs were produced annually.

Regarding the type of publication, the majority comprises journal articles, followed by book chapters, and then mostly a range of postgraduate projects, as can be seen from Figure 2. A few articles can be found in non-academic publications4 but, when analysing this particular graph in conjunction with the year of publication, there seems to be a decline in writing magazine articles and a rising preference for writing journal articles - rightfully so, given the pressure that academics are under to publish in (especially accredited) journals. The variety of types of postgraduate research output is positive, not only because these studies will hopefully turn into journal articles or book chapters in the future, but, more importantly, it is indicative of the fact that there remains a focus on interpreting research as an area of interest in postgraduate studies in South Africa.

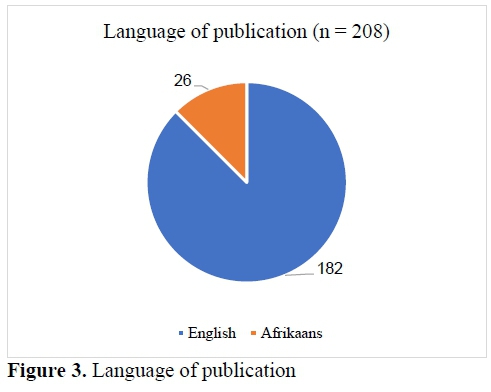

As shown in Figure 3, a trend that was identified during the pilot investigation and confirmed during the full-scale study is the preference to publish in English. Although a few publications were published in Afrikaans, it does not seem to be a preferred language of publication, and no other language (indigenous or not) was published in during the review period. As mentioned by Kotzé and Wallmach (forthcoming), in a country where only 9,6% of the population speaks English as a home language (Brand South Africa 2011), questions do arise regarding the language that scholars prefer to use when submitting their research for publication.

Although not the focus of this article, a few of the very complex issues that need to be taken into account when addressing this topic include global power structures, the social organisation of a developing country, growing North/South disparities, the question of collaborative research, and the discursive and non-discursive problems faced by researchers in peripheral countries (Salager-Meyer 2008: 121). In South Africa, as is the reality worldwide, mounting pressure on academics to publish in internationally acclaimed journals will influence the decision to write articles in English, and ensuring one's work is disseminated to and read by as large an audience as possible may tip the scales. It does stand to reason, however, that not publishing in the indigenous languages of South Africa may prove to be costlier in the long-term than not doing so if the country is truly invested in transforming its current postcolonial society - an issue which is more closely investigated in a separate project (Kotzé 2018).

Figure 4 shows that the interpreting contexts that are most frequently researched and published on are healthcare and education. This trend was also evident during the pilot investigation, and the emphasis specifically on interpreting in healthcare contexts was not surprising. Various studies done within this context have proven that the language barrier between medical professionals and patients in South Africa is a real problem (cf. Anthonissen 2010, Deumert 2010, Pfaff and Couper 2009). The majority of healthcare professionals cannot speak any of the indigenous African languages (Levin 2006), and errors in diagnosis and treatment are often made (Schlemmer and Mash 2006). Given these realities, research on interpreting in this domain is a logical trend.

Also, as was the case with the pilot period, there is evidence of a focus on educational interpreting (Education). Given the fact that spoken-language educational interpreting is used in South Africa on a scale larger than anywhere else in the world (Kotzé 2012), the research possibilities within this area are vast. Historically Afrikaans-speaking universities were met with constitutional commitments regarding multilingualism after the democratisation of the country in 1994. These institutions responded to these obligations with various attempts to solve the multilingualism challenge (Verhoef 2018: xii). Therefore, due to the practice of educational interpreting being relatively new, the resulting research interest and high number of research outputs is understandable.

The points of departure - in other words, what researchers were interested in when undertaking a particular project - included various themes and combinations of themes, which are visible in Figure 5. The main ones were interpreting quality, language policy and planning as it relates to interpreting, training interpreters, and research into interpreting practice. The focus on quality could be due to the implementation of language services, such as interpreting, after 1994. This is because, prior to democracy, interpreting services were not frequently used in South Africa and consequently offered a rich environment for research. The same applies to interpreter training: it is safe to assume that interpreters required immediate training in order to fulfil the sudden need for interpreters. In addition, due to the implementation of a new language policy in the country, a number of articles focused on policymaking and the language planning issues that ensued. As is evident from Figure 5, although a number of unique combinations appear, the publications relate mostly to quality, training, and language policy and planning.

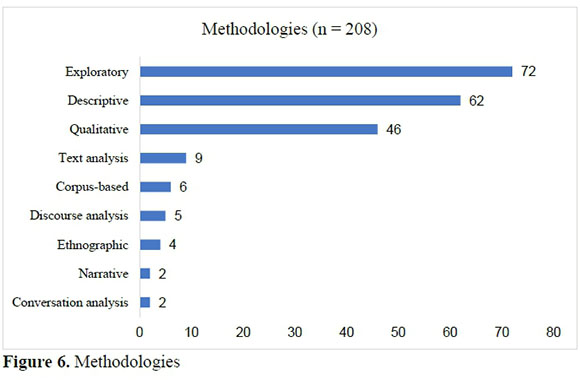

In Figure 6, it is evident that South African interpreting studies scholars prefer exploratory, descriptive, and qualitative research methodologies. There are a few instances of text analysis, corpus-based analysis, and discourse analysis, and even fewer ethnographic, narrative, and conversation analysis approaches.

Hale and Napier (2013: 11-12) comment that exploratory research is usually conducted within fields that have not yet been researched before, and is followed by descriptive and explanatory methods. These methods aim to answer the following questions: "What can we find out about X? [...], what is the nature of X? [...] and why and how X?". Although these are very useful questions to ask, given the challenges of multilingualism that we are experiencing in South Africa, it may be time to start asking questions and using methodologies that would provide us with not only useful data, but answers to pressing problems. These problems include, for instance, where to start with developing the indigenous African languages into languages which can be used in scientific domains.

In this regard, corpus studies may offer some possibilities. However, this will not be a simple task. Setton (2011: 34) describes corpus interpreting studies as a "cottage industry", with reference to the more established corpus translation studies. Problems that are prevalent within the corpus interpreting studies environment include small corpora issues regarding transcribing and annotating data, and the availability of data. Even though this may be true, Bendazzoli (2018: 12) concludes that we can also expect a rising trend in corpus-based interpreting studies as it is "becoming increasingly wired as it takes advantage of the potential of Web 2.0 technologies and collaborative work leading to larger and more representative interpreting corpora".

In addition to the findings already discussed, the data was also analysed in terms of language combinations. Figure 7 indicates that, of the 208 publications investigated, 179 investigated or referred to specific language combinations. The combinations varied between the majority (43) of publications that investigated English and Afrikaans in relation to indigenous African languages, and a number of single publications with unique language combination interests, such as isiZulu and South African Sign Language.

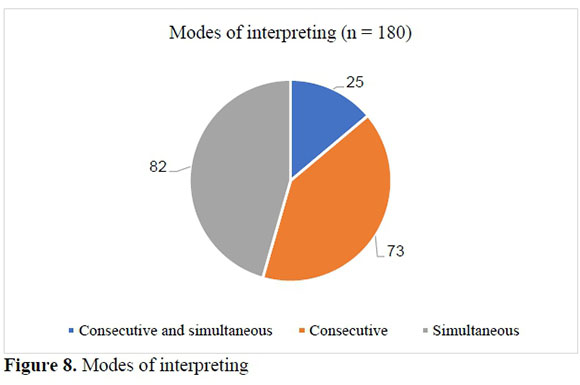

Lastly, regarding modes of interpreting, Figure 8 is a representation of where mode was under investigation in each of the publications. Of the 180 publications which explicitly researched issues regarding interpreting mode, studies on simultaneous and consecutive interpreting individually are almost evenly spread, while far fewer studies referred to both simultaneous and consecutive mode.

5. Synthesis

This investigation into research on interpreting studies in South Africa leads to a number of conclusions.

First, a research interest and publication trend in interpreting remains evident and, although not of a very high frequency, indications are that research in this area will continue to grow based on the number of postgraduate projects that are seen annually. The reasoning therefore is that all academic endeavours originate from interest on graduate level, culminating in postgraduate projects and eventually a career in academia. Several postgraduate projects are completed annually, and could possibly add to the existing body of research in the form of journal articles or book chapters.

The majority of publications analysed are of an academic nature in the form of book chapters and articles in academic journals. A next step in this research process will be to determine the impact these items have made by conducting a citation count and doing a possible network analysis on the relations that exist between individual authors or researchers.

Contextually, research on interpreting in South Africa focuses mainly on healthcare and education from the points of departure of quality, language policy and planning, training, and research. Although South Africa's healthcare and education systems have unique challenges, the recurring nature of the themes of quality, policy issues, training, and research substantiates Wadensjo's (2011: 13) statement that, although interpreting studies have developed substantially as a field, the development has "evolved around certain recurrent themes" such as those mentioned above. The fact that these themes are researched in the South African context also confirms the conclusion made by Kotzé and Wallmach (forthcoming) that South African research mainly follows international trends.

From a methodological point of view, several methodologies are not applied in studies on interpreting - methodologies that could be advantageous not only to the development of interpreting studies, but also to the country's multilingual nature. Using text-, discourse-, and conversation analysis and corpus studies will serve as valuable teaching, learning, and training resources in the country's languages. In addition, these resources will provide insight into where these languages can and should be developed and successfully used in scientific domains. If interpreting studies were approached using, for example, corpus-based studies, one would not only be taking advantage of the various benefits of corpus studies (including extracting occurrences automatically to look at trends, patterns, concordances etc.; Bendazzoli 2018: 2), but also use it as an educational tool when training interpreting students. From a pedagogical point of view, the use of indigenous language examples and local contexts would offer a rich learning environment for our interpreting students. Moreover, having access to corpora on indigenous language interpreting would allow us to have an in-depth view of where these languages should and can be developed.

This article does not report on many of the other trends to be found in the data, for instance, when and why interest in interpreting (and subsequent research on interpreting) started in South Africa. This, among other things, will be reported on in a follow-up article which aims to provide an overview of the research and the research findings contained in the IRSA database.

In conclusion, an investigation into the research on interpreting in South Africa has offered useful insight into the development of the field in the country. Much could be deduced from the data and analyses, which makes room for new directions to be taken in terms of teaching, learning, and research, and possibly provides options for addressing some of the country's multilingual challenges.

References

Anthonissen, C. 2010. Managing linguistic diversity in a South African HIV/AIDS day clinic. In B. Meyer and B. Apfelbaum (eds.) Multilingualism at work: From policies to practices in public, medical and business settings. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. pp. 107-139. https://doi.org/10.1075/hsm.9.07ant [ Links ]

Bendazzoli, C. 2018. Corpus-based interpreting studies: Past, present and future developments of a (wired) cottage industry. In M. Russo, C. Bendazzoli and B. Defrancq (eds.) Making way in corpus-based interpreting studies. Singapore: Springer. pp. 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-6199-81 [ Links ]

Borgman, C.L. 1990. Editor's introduction. In C.L. Borgman (ed.) Scholarly communication andbibliometrics. Newbury Park, London and New Delhi: Sage. pp. 10-27. [ Links ]

Borgman, C.L. 2000. Scholarly communication and bibliometrics revisited. In B. Cronin and H.B. Atkins (eds.) The web of knowledge. A festschrift in honor of Eugene Garfield. Medford, NJ: Information Today. pp. 143-162. https://doi.org/10.1108/el.2001.19.4.261.2 [ Links ]

Bornman, E., J.C. Pauw, P.H. Potgieter and H.H. Janse van Vuuren. 2017. Moedertaalonderrig, moedertaalleer en identiteit: Redes vir en probleme met die keuse van Afrikaans as onderrigtaal ['Mother-tongue education, mother-tongue learning and identity: Reasons for and problems with choosing Afrikaans as the language of teaching']. Journal of Humanities 57(3): 724-743. https://doi.org/10.17159/2224-7912/2017/v57n3a4 [ Links ]

Brand South Africa. 2011. South Africa's languages. Available online: https://www.brandsouthafrica.com/south-africa-fast-facts/geography-facts/languages (Accessed 15 June 2020).

Deumert, A. 2010. 'It would be nice if they could give us more language': Serving South Africa's multilingual patient base. Social Science and Medicine 71(1): 53-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.036 [ Links ]

Erasmus, M. (ed.) 1999. Liaison interpreting in the community. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Fink, A. 2005. Conducting research literature reviews. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Garfield, E. 1955/2000. Citation indexes for science. A new dimension in documentation through association of ideas. In B. Cronin and H.B. Atkins (eds.) The web of knowledge. A festschrift in honor of Eugene Garfield. Medford, NJ: Information Today. pp. 26-34. https://doi.org/10.1108/el.2001.19.4.261.2 [ Links ]

Garfield, E. 1994. The ISI impact factor. Available online: http://scientific.thomson.com/free/essays/journalcitationreports/impactfactor/ (Accessed 3 March 2018).

Grbic, N. 2013. Bibliometrics. In Y. Gambier and L. Van Doorslaer (eds.) Handbook of translation studies. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. pp. 20-24. [ Links ]

Grbic, N. and S. Pollabauer. 2008. To count or not to count: Scientometrics as a methodological tool for investigating research on translation and interpreting. Translation and Interpreting Studies 3(1/2): 87-146. https://doi.org/10.1075/tis.3.1-2.04grb [ Links ]

Hale, S. and J. Napier. 2013. Research methods in interpreting. A practical resource. London: Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Kotzé, H. 2012. 'n Ondersoek na die Veranderlike Rol van die Opvoedkundige Tolk ['An Investigation into the Changeable Role of the Educational Interpreter']. Unpublished PhD dissertation, North-West University. [ Links ]

Kotzé, H. 2018. Publication trends in South African interpreting studies: Which language(s) do we publish in? Paper presented at ICL2018, 2-6 July 2018, Cape Town, South Africa.

Kotzé, H. and K. Wallmach. Forthcoming. Interpreting research in South Africa: Where to begin to transform? In R.H. Kaschula and H.E Wolff (eds.) African languages in knowledge societies: The transformative power of languages. Cambridge University Press.

Levin, M.E. 2006. Language as a barrier to care for Xhosa-speaking patients at a South African paediatric teaching hospital. South African Medical Journal 96(10): 1076-1079. [ Links ]

Lubbe J. 2002. Die aard van bydraes van Taalfasette en Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Taalkunde, 1965 tot en met Desember 1999 ['The nature of contributions in Taalfasette and South African Journal of Linguistics, 1965 to December 1999']. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 20(1/2): 65-91. https://doi.org/10.2989/16073610209486299 [ Links ]

Moeketsi, R. 1999. Discourse in a multilingual and multicultural courtroom: A court interpreter's guide. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Okoli, C. and K. Schabram. 2010. A guide to conducting a systematic literature review of information systems research. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/31dc/753345d5230e421ea817dd7dcdd352e87ea2.pdf (Accessed 7 June 2016).

Pfaff, C. and I. Couper. 2009. How do doctors learn the spoken language of their patients? South African Medical Journal 99(7): 520-522. [ Links ]

Pienaar, M. 2006. Kommunikasie tussen staat en burgers: Die stand van tolkdienste ['Communication between government and citizens: The current state of interpreting']. Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Taalonderrig 40(1): 35-47. [ Links ]

Pienaar, M. and E. Cornelius. 2016. Contemporary perceptions of interpreting in South Africa. Nordic Journal of African Studies 24(2): 186-206. [ Links ]

Price, D.J.D. 1963/1965. Little science, big science. New York and London: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Salager-Meyer, F. 2008. Scientific publishing in developing countries: Challenges for the future. Journal of English for Academic Purposes 7(2): 121-132. https://doi.org/10.1016/i.ieap.2008.03.009 [ Links ]

Schlemmer, A. and B. Mash. 2006. The effects of a language barrier in a South African district hospital. South African Medical Journal 96(10): 1084-1087. [ Links ]

Setton, R. 2011. Corpus-based interpreting studies (CIS): Overview and prospects. In A. Kruger, K. Wallmach and J. Munday (eds.) Corpus-based translation studies: Research and applications. London: Continuum. pp. 33-75. [ Links ]

Van Doorslaer, L. 2016. Bibliometric studies. In C.V Angelelli and B.J. Baer (eds.) Researching translation and interpreting. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 168-176. https://doi.org/10.7202/1038692ar [ Links ]

Verhoef, M. 2008. Introduction. In M. Verhoef and L.T. du Plessis (eds.) Multilingualism and educational interpreting: Innovation and delivery. Pretoria: Van Schaik. pp. xii-xiv. [ Links ]

Verhoef, M. and L.T. du Plessis. (eds.) 2008. Multilingualism and educational interpreting: Innovation and delivery. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Wadensjo, C. 2011. Interpreting in theory and practice: Reflections about an alleged gap. In C. Alvstad, A. Hild and E. Tiselius (eds.) Methods and strategies of process research: Integrative approaches in translation studies. Philadelphia: Benjamins Translation Library. pp. 13-22. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.94.04wad [ Links ]

Webb, V. 1999. Multilingualism in democratic South Africa: The over-estimation of language policy. International Journal of Educational Development 19(4/5): 351-366. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0738-0593(99)00033-4 [ Links ]

1 "Magazines" refer to publications which are of an academic/professional nature, for instance, the newsletter of a particular association. They are not viewed as scholarly due to the fact that they are not accredited by the Department of Higher Education.

2 "Reports" refer to documents which were commissioned by a particular professional or governmental institution to investigate and report on a specific topic.

3 It is important to mention that a particular research project, such as a doctoral thesis, may be listed in the data in addition to a subsequent article published from the thesis. In other words, if a student completed a PhD and published an article, this was recorded in the database as two research outputs. However, due to the metadata that can be extracted using Zotero, such cases are easily identified, and are left as such due to their unique contributions.

4 Refer to footnote 1.