Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus (SPiL Plus)

On-line version ISSN 2224-3380

Print version ISSN 1726-541X

SPiL plus (Online) vol.59 Stellenbosch 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.5842/59-0-792

ARTICLES

Construction of deaf narrative identity in creative South African Sign Language

Ruth MorganI; Michiko KanekoII

ISASL Department, School of Literature, Language and Media, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa E-mail: Ruth.Morgan@wits.ac.za

IISASL Department, School of Literature, Language and Media, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa E-mail: Michiko.Kaneko@wits.ac.za

ABSTRACT

In this article, we observe how deaf narrative identities emerge in creative South African Sign Language (SASL) texts. We first identify how difficulties in establishing deaf cultural identities in the hearing-dominant audist world are represented in the "Man against Monster" plot (Booker 2004) commonly employed in sign language narratives. Then, we use De Certeau's (1984) notion of 'place versus space' and Heap's (2003) notion of 'Sign-deaf space' (plus our own term of "mediated Sign-speak space") to explore how deaf artists transform the Monster (i.e. the oppressive hearing place) into deafhood and deaf space, which leads to the celebration of sign language and deaf culture. We also demonstrate how the recent notion of 'sensescape', coined by Rosen (2018), can be applied to the construction of deaf narrative identity. The Monster in deaf stories can be understood not only in terms of the audist ideology but also in terms of different sensory orientations between deaf and hearing characters. We conclude that creative texts provide a wealth of opportunities to explore how narrative identities are constructed. In fictional stories, deaf narrators step back from being themselves, and extract the essence of their shared experience and sublimate it into a search for deafhood. Various notions developed within the field of deaf studies - such as 'deafhood', 'deaf space' and, 'deaf geographies' - are useful in (re-)interpreting existing texts and shedding a new light on them.

Keywords: SASL; creative signing; narrative identity; deaf

1. Introduction

In this article, we explore how sign language artists (deaf1 storytellers and poets) construct their deaf identities through creative narratives ("deaf narrative identity"). Narrative identity fits into the fluid notion of 'identity' and its dependence on context. Different aspects of one's identity are highlighted, depending on different times, places, and audiences.

A number of researchers have analysed signed biographic narratives as a means of understanding the construction of deaf cultural identities using American Sign Language (ASL) narratives (Hole 2007, Leigh 2009), British Sign Language (BSL) narratives (West 2012), and South African Sign Language (SASL) narratives (Mcllroy and Storbeck 2011, Morgan 2014). However, little research has been done on how deaf narrative identity emerges in signed literary (creative) texts2. A few notable publications on this topic include Sutton-Spence (2010) in her discussion of identity construction in BSL literature, and Morgan and Meletse (2017, and Morgan et al., in press) in their analysis of queer deaf African identity construction in SASL and International Sign (IS) poetry. Christie and Wilkins (2007) identified common themes of affirmation, oppression, and resistance in terms of identity construction that emerged in both ASL literature and post-colonial written literature.

The use of poetry performances as a means of constructing alternative identities can be found in spoken and written poetry. For example, Sarikaya (2011: 161) identifies the Afro-Caribbean identities of resistance to racism and affirmation in the spoken and written poetry of Linton Kwesi Johnson, a Jamaican dub poet.

With his use of performance and dub, Johnson achieves revival of Afro-Caribbean oral tradition through his poetry. He succeeds in turn poetry into an act of cultural activity in which the audience also is involved.

Brunner states in the context of the analysis of written confessional poems in English, that such texts "are indeed a fruitful source for questions of identities [...] the poems include multiple selves [and] self actualization [...] [P]oetry can provide aesthetically elaborated presentation of identities" (2013: 200-201). In a similar way, the performance of creative sign language is seen as a vehicle to express different aspects of deaf cultural identities.

The positive acknowledgement of deaf identity and deaf culture, however, is a relatively recent phenomenon. It started in the 1970s/80s with the recognition of sign languages as fully-fledged languages, stipulated by William Stokoe's (1960) publication on the structure of ASL. Until that time, deaf people were viewed from a medical perspective as people with problems that needed to be fixed. Deaf people were seen as substandard, and the attempt to "normalise" deaf children by imposing speech on them (and not allowing the use of sign language) has been prevalent in deaf schools across the world. This practice stemmed from an international educational conference in Milan in 1880 where sign language was banned. The belief that speech is superior to sign language is known as "audism", which we will explore later. Under such an ideology, the positive reinforcement of one's identity as a deaf person was not possible.

Since the 1980s, however, this view has started to change, and deaf people are seen more from a social perspective as a linguistic and cultural minority. In the early 2000s, the term "deafhood", coined by Ladd (2003), became widely known among deaf people and those working in the field of deaf studies. This term refers to the journey each deaf person goes through in order to find his/her place in the world as a deaf person, usually through meeting and interacting with other deaf people and learning the values of the deaf community. Deafhood theory has been criticised as too essentialist (Kusters and De Meulder 2013) although Ladd (2015) has always emphasised that it is only strategically essentialist as a result of the ongoing need for deaf people to focus on gaining equal rights. Ladd discusses a multiplicity of possible identity constructions including the role of intersectional identities, e.g., according to nation, race, ethnicity, class, age, and gender. More recently, the notions of 'deaf space' and 'deaf geography' emerged to refer to the fluid interactive spaces produced collectively by deaf people. They highlight the importance of looking at the notion of 'constructing identity' in relation to embodiment and space (Fekete 2017, Gulliver and Fekete 2017). There is also the notion of 'sensescape', proposed by Rosen (2018), focusing on the construction of deaf space as a sensory world by prioritising the role of the senses in the physical environment.

However, before the emergence of such elaborate terms in the academy, sign language artists have been talking about deaf identities and the unique space occupied by deaf people, as evident in many creative texts in sign language literature. One of the aims of this article is to apply the recently theorised notions from deaf geographies ('deaf space', 'embodiment', 'sensescape' etc.) to our analysis of narrative identities in existing creative texts in SASL.

In the US and the UK during the 1980s and 90s, renowned deaf poets such as Dorothy Miles, Clayton Valli, and Robert Panara tackled the question "Who am I?" using sign language poetry as a medium of expression (Nathan Lerner and Feigel 2009). The same can be said about SASL. As early as 2000, South African deaf artists were talking about "two worlds" - the hearing world and the deaf world - and the journey these artists took to establish themselves firmly in the deaf world rather than in the world dominated by hearing people.

Using sign language literature to recreate deaf culture is extremely important for deaf people, as more than 90% of deaf children in the US are born to hearing families (Padden and Humphries 2005). The fact that only a minority of deaf children are born into deaf families is well documented globally (Ladd 2003, Bauman 2008). Most deaf children do not inherit a deaf identity from their parents. Deaf schools, instead of families, play an important role in establishing these children's sense of belonging and enabling these children to experience the shared values and interests of the South African and international deaf communities (Baker and Padden 1978, Bauman 2008, Morgan 2008, Baker 2017, Stander and Mcllroy 2017). The storytelling tradition is at the centre of such identity development at schools - deaf teachers and older deaf children tell stories and jokes in sign language, which fosters young deaf children's linguistic development as well as cultivating their awareness of being a member of the deaf community (Ladd 2003).

The term "audism" was initially coined by Humphries (1975) in relation to hearing individuals who felt and acted superior to deaf people on the basis of "phonocentrism" (the fact that these individuals could hear and talk). This term was later extended and popularised by Lane (1992: 43) who used it beyond the level of the individual to refer to a broader ideology: "the hearing way of dominating, restructuring and exercising authority over the Deaf community". Experiences of audism in South African schools for deaf learners abound at the hands of hearing educators and housemothers (Morgan 2008, 2014; Stander and Mcllroy 2017). These experiences are also embedded in creative SASL texts (Morgan and Kaneko 2017, 2018). Creative texts are the vehicle of cultural expressions in all languages. A number of ASL poems, especially the earlier works from the 1970s and 80s, focused on painful experiences of audism, especially in relation to the oppression of sign language in schools (Nathan Lerner and Feigel 2009). Generally, a deaf child experiences audism acutely from his/her own parents, school teachers, speech therapists, and doctors. Unsurprisingly, creative SASL texts highlight issues around deaf culture and identity, specifically audism. Through sharing their oppressive painful experiences, deaf people form identities of resistance. Ladd (2003) discusses this in terms of the positive effects of oralism. Oralism resulted in the creation of an underground deaf culture of performance (Baker 2017; Morgan and Kaneko 2017, 2018).

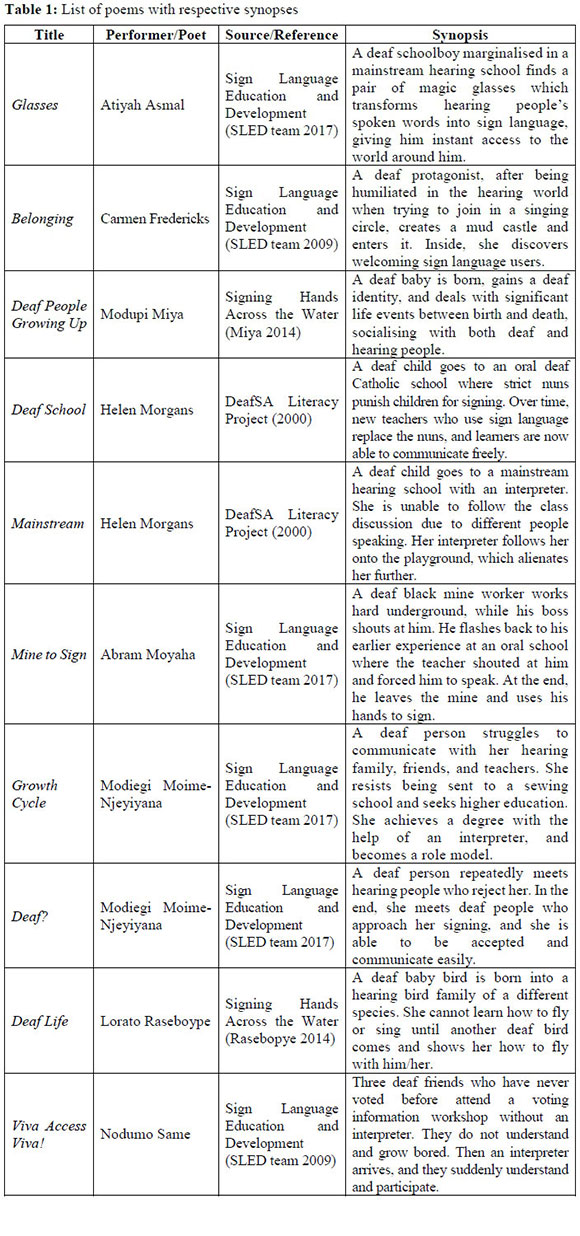

This article illustrates how deaf South Africans use creative sign language texts as a way of establishing their deaf narrative identities, both personal and collective. From the collection of 73 poems we put together in our previous work (Morgan and Kaneko 2018), we have selected 10 poems by eight signers from different cultural backgrounds. All of these poems have a deaf protagonist and show aspects of deafhood.

Using these 10 poems, we will identify common challenges and problems experienced by deaf artists, as well as looking at how these artists transform the stigma attached to deafness into the celebration of deaf identities and of their unique sensory experiences (Ladd's (2003) notion of 'deafhood'). Our discussion is divided into three sections, namely Identifying the Monster in deaf narratives (Section 2), From places to spaces (Section 3), and Sensescape (Section 4).

First, we will introduce and discuss one common plot that appears widely in sign language texts, namely "Man against Monster" (Booker 2004, Sutton-Spence and Kaneko 2016). This Monster can be any form of oppression or control (racism, sexism), but in this article we will focus on the Monsters that emerge from a hegemonic, oppressive, hearing audist world. We do so because it is usually through the struggles against hearing people that deaf people bond with each other and establish their identities. Using a deaf geographical framework, we will then explore how this process of overcoming involves the transformation of audist "places" of oppression into empowering deaf "spaces" (De Certeau 1984, Valentine and Skelton 2008, Morgan 2014). Another important focus is the transition in sensory orientations from auditory to visual (Rosen 2018). This is necessitated by the fact that sign languages are primarily visual-gestural languages produced in space. Accordingly, deaf people rely on visual processing and have long been called "the people of the eye" (Bauman 2008).

2. Identifying the Monster in deaf narratives

A number of narratives by deaf people are so-called "stories of Deaf everyman" (Peters 2000), or the "narratives of personal experiences" (Bahan 2006a) in which the narrator shares his/her experience as a deaf person in the form of a story. The deaf audience can identify with the narrator through the shared experience of being deaf in the world. A large part of such shared experiences is to do with the social prejudice and ignorance of hearing people. In expressing their struggle in a hearing-dominant world, the plot of "Man against Monster" is often utilised in deaf narratives.

In 2004, folklorist Christopher Booker identified seven universal plots in stories from various cultures. Sutton-Spence and Kaneko (2016) apply these plots to the works of sign language artists. Morgan and Kaneko (2018) further explore these seven plots using the collection of 73 SASL poems3. These authors find that the "Man against Monster" plot appears most commonly in SASL poems. The Monster can be understood as anything that comes in the way of the protagonist achieving his/her dream. In many SASL poems, the Monster portrays apartheid and the social oppression of black people; it can also be a personal archenemy or one's own weakness. However, in the texts that deal with deaf identity, the Monster is usually the hearing people who impose their audist attitudes upon deaf characters. Since deaf people interact with hearing people on a daily basis throughout their lives, the challenges of operating in a hearing world are portrayed in a number of settings and scenarios, including (i) isolation at home, (ii) the school experience, (iii) medical interventions, (iv) academic challenges, and (v) the work environment.

The first challenge for deaf children is the lack of communication with their family which leads to isolation in their own home. This is portrayed in the poem Glasses performed by Atiyah Asmal. In this poem, a deaf boy is the only deaf member of his family, and does not share a common language with his parents. A similar situation can be identified in Lorato Rasebopye's Deaf Life, an allegory in which a deaf bird is born to a hearing (singing) bird family, and feels isolated as a result of being unable to sign like and fly with her mother and siblings. In Modiegi Moime-Njeyiyana's performance of Growth Cycle, the protagonist's failure of communication at home is artistically represented by an ambiguous sign (Figure 1) which can be understood as the sign communication-breakdown, as well as the "seed" rooted in her body (a metaphor for an early form of her core self, her identity) rolling away from her.

In these contexts, hearing parents and siblings often involuntarily become the Monster for young deaf children, due the former's lack of understanding of deaf culture and unwillingness to learn sign language.

Deaf children born to hearing parents are exposed to neither the culture of their parents nor the culture of the deaf community. Every generation of deaf people needs to (re-)construct deaf culture on their own. Since this cannot be achieved at home, it is usually deaf schools that function as a place of early identity development for deaf children (Ladd 2003, Padden and Humphries 2005, Morgan 2008). There, for the first time, they meet other deaf children and deaf adults. However, the school (institutional) experience for young deaf children can be negative. Many schools still follow oralism, an education system based on the ideology of audism. Based on the belief that deaf children must be taught to speak like "normal" hearing children, oralism imposes speech and lip-reading as a medium of instructions for deaf learners (Bauman 2008, Padden and Humphries 2005). Deaf children are often punished for using signs in class (Ladd 2003, Morgan 2008). Helen Morgans' SASL poem entitled Deaf Schools clearly portrays this painful experience (Figure 2). The nuns at the deaf school impose speech and lip-reading on deaf children, and are thus viewed as the Monster in this particular context (however well-intentioned they may have been).

Some deaf children are sent to mainstream hearing schools, which can be another painful experience for a young deaf child. The school may provide interpreters or other means of accommodation, but the deaf child is often socially excluded as well as mocked by hearing children for his/her deafness. Carmen Fredericks' Belonging describes the loneliness of a deaf child who is placed among hearing children in a singing class. She attracts unwanted attention as she cannot sing like other children (Figure 3a). Helen Morgans' poem Mainstream shows frustration and disbelief toward mainstream education. The protagonist seems to be the only deaf child in the school. She wants to interact with other children, but she has to be accompanied by an interpreter wherever she goes. She is also stared at cruelly by hearing children when she approaches them (the sign is almost identical to that of Fredericks - see the comparison in Figures 3a (Fredericks) and 3b (Morgans)). These hearing children can be seen as the Monster for deaf children. However, the real Monster in these stories is the education system itself - a system that encourages integration and mainstreaming without giving sufficient thought to its impact on deaf learners who may not be able to cope in such an environment.

Young deaf children encounter medical experts at home and at school in the form of doctors, speech therapists, and audiologists, who assist in diagnosing deafness and encourage the children to make the most of their hearing and speaking abilities. In deaf stories, medical experts such as these are usually portrayed in a negative light. They are depicted as the proponents of the medical view of deafness - i.e. deafness as something "abnormal" that needs to be fixed. Specifically, their attempts to impose cochlear implants on deaf babies is seen as highly controversial4. In Figure 4 below, Modiegi Moime-Njeyiyana's Deaf? briefly illustrates receiving cochlear implants but her expressions show that the result was unsatisfactory.

A large part of deaf children's school years is spent in speech training or being taught in a spoken language which they cannot access. Little time is spent teaching them other subjects, and the fact that their teachers cannot communicate with them in sign language prevents them from learning how to read and write beyond the level of Grade 4 (corresponding to a nine-year old who has attended school since the age of six). Thus, for a long time, deaf children have not achieved well academically. While a small number of orally-gifted deaf children who could benefit from amplification were encouraged to continue their studies, the majority of deaf children, who remain unable to speak, were regarded as academic failures and were sent to vocational schools. Modiegi Moime-Njeyiyana's abovementioned poem, Growth Cycle, expresses the frustration of not being allowed to succeed academically. The main character in this story is told several times by her teacher to go to a sewing school. She refuses to do so, studies hard, and goes to university where, with the help of an interpreter, she manages to gain "the fruit of knowledge" and graduates. Her "seed", which was very small and not established at the beginning (see Figure 1), bears figurative fruit which she shares with the next generation. She is determined to defy the belief that deaf people cannot achieve academically.

Lastly, deaf people continue to struggle in the workplace as well. Persisting audism is observed in Mine to Sign, performed by Abram Moyaha, in which a deaf miner experiences harassment from his hearing boss. Just as the school teachers (nuns) impose speech in Helen Morgans' Deaf School, here, a hearing boss is forcing the deaf adult protagonist to communicate in speech. Literally and symbolically, the hearing mining boss looks down upon the deaf miner while the former is shouting at the latter (Figure 5a). As a result, the miner has a flashback to his childhood when hearing teachers shouted at him and forced his chin up in order to feel the vibration of his vocal cords when teaching him to make sounds (Figure 5b). The vicious boss bullying the deaf miner is a most credible Monster.

This section presented how creative SASL is used to represent the struggles of deaf people in a hearing world, by identifying Booker's (2004) plot of "Man against Monster". Deaf narrative identities often emerge by acknowledging and overcoming such Monsters. In the next section, we explore this process of overcoming the Monster in relation to De Certeau's (1984) notions of 'place' and 'space'.

3. From places to spaces

Deaf sign language artists use SASL literature to create deaf signing spaces of empowerment in order to construct their deaf narrative identities. We draw on the work of De Certeau (1984) who uses the terms "places" and "spaces" idiosyncratically and metaphorically. The term "places" refers to hegemonic, fixed, and static sites of control. This is in contrast to fluid, changing, and unstable "spaces" in which ordinary people conduct their lives, resisting the dominant discourse. In our context, the notion of 'audist places' (inflexible sites of oppression) is evident in our analysis of creative signed texts as seen above. These places can be understood as inhabited by the Monsters. Schools especially are often seen as oppressive "places" where sign language and developing a deaf core self is not respected or allowed. In many of the texts we discussed above, the protagonist first experiences oppression of sign language in the school context, as in Helen Morgans' Deaf School and Abram Moyaha's Mine to Sign. Hearing teachers hinder learners from achieving their potential and studying further, as demonstrated in Modiegi Moime-Njeyiyana's Growth Cycle. Self-respect and the joy of signing are only experienced once these oppressive "places" are transformed into deaf, signing "spaces". It is in these signing spaces that the deaf protagonists are finally able to achieve their deaf narrative identities through the process of deafhood.

Following Heap (2003), we now discuss two kinds of spaces in creative SASL texts. The first is "Sign-deaf spaces" where deaf people interact with each other using SASL and co-create an empowering space. The second refers to "mediated Sign-speak spaces" in which a deaf person remains in the hearing place but, through some sort of mediation and facilitation (such as interpreters), he or she can communicate and be part of the world.

3.1 Sign-deaf spaces

Heap (2003: 128) describes "Sign-deaf spaces" as "spaces of communality and solidarity; spaces where people felt that they belonged and could identify with other deaf people". In many creative SASL texts, narrative deaf identities are forged in relation to other deaf signers. We highlight below the creation of Sign-deaf spaces in four poems in our collection.

The construction of a narrative self is often portrayed in the movement or journey of the narrator between places and spaces (De Certeau 1984). This journey (from an oppressive audist place to a signing space) is most clearly demonstrated in Carmen Fredericks' abovementioned poem, Belonging. After being humiliated by hearing people, she goes off alone and physically creates a Sign-deaf space in the sandcastle she builds (see Figure 6). She makes a door/gate in her castle and somehow manages to enter inside. This is where she immediately feels at home when she is welcomed by deaf people who communicate with her in sign language. In this poem, the protagonist physically creates an actual building enclosing and protecting the Sign-deaf space. In the term used by deaf geographers (Gulliver and Kitzel 2016), it is in the "built environment" of her castle in a deaf-only space that the narrator becomes her best possible self.

In Modiegi Moime-Njeyiyana's poem Deaf?, briefly discussed above, the deaf narrator, having gone through a long struggle with audism in the hearing world, ultimately finds her own deaf narrative identity within a Sign-deaf space. As in Belonging, it is only when she meets other deaf people whom she can communicate with through sign language that her own isolation and sadness turn to feelings of self-connection and connection with others. This is in contrast to repeated rejection in the hearing world where she is ignored as a result of her inability to use spoken language, even after having received cochlear implants (Figure 7).

In Lorato Rasebopye's text Deaf Life, also briefly discussed in the previous section, the deaf baby bird feels completely isolated from her hearing bird family when she cannot fly in the way that they do. But then she meets another deaf bird with whom she can communicate using sign language, and this bird teaches her a very different way of flying. In this story, the "hearing" way of flying, as it were, is to swing the elbows while the fists remain closed (Figure 8a). In contrast, the "deaf" way of flying involves opening of the hands, which symbolically represents sign language. The narrator uses the same open handshape for sign and fly (see Figure 8b). The deaf bird easily learns this way of flying and flies out happily with her new friend.

Modupe Miya's Deaf People Growing Up is unusual as it does not focus on audism. This poem makes no mention of negative experiences in the hearing world. Instead, being deaf is normalised in his narration of the life course of a deaf child born to hearing parents. The Sign-deaf space is described as follows: as a very young child walking with his mother down the street, he is drawn to other sign language users chatting in a public space. He pulls his mother with him as he wants to better observe the Sign-deaf space (Figure 9a). In this story, the Sign-deaf space is not overtly contrasted with the hearing world. Ultimately the protagonist grows up and has a relationship with a deaf woman with whom he can communicate in sign language (Figure 9b), has children, and grows old and dies (Figure 9c). It is interesting that the late poet himself had a very good relationship with his hearing family who were strong advocates of the use of SASL (Setai 2014).

3.2 Mediated Sign-speak spaces

We now discuss three examples of SASL creative texts in which poets reposition themselves as changing the hearing place to a space of access and communication. They do this by transforming an oppressive hearing place into a signing space using different means, namely by using an interpreter, as in Modiegi Moime-Njeyiyana's Growth Cycle and Nodumo Same's Viva Access Viva!, or sometimes even by "magic", as in Atiyah Asmal's Glasses.

These spaces are different from Heap's (2003) Sign-deaf vs Sign-hear spaces. They comprise a third mediated space where either an interpreter or magic glasses are used to create a signing space for the deaf person. This allows deaf and hearing people to communicate in their own language, where deaf people sign and hearing people speak.

Growth Cycle and Viva Access Viva! focus on the power of SASL interpreters to transform hearing "places" into signing "spaces" of access and participation through the use of sign language. In Growth Cycle, the poet refuses to accept being sent to a sewing school and insists that she wants to study further through SASL at university. At university, a SASL interpreter transforms the oppressive educational system into a place of access, enabling her to follow her dream and attend hearing classes so that she can fulfil her dream to graduate with a degree.

In Same's Viva Access Viva!, the arrival of a SASL interpreter transforms the hearingdominated voting centre into a signing space. The three deaf voters are excited to be voting in the first democratic elections of 1994, and have been struggling to understand the hearing speakers and the procedures (Figure 10a). After waiting in the long queue of voters, a SASL interpreter arrives, and their confidence and engagement in the space changes as they can now understand the speakers and the instructions (see Figure 10b). They go ahead and cast their vote. The poem ends with the jubilant poet signing viva-access-viva! (Figure 10c).

In Glasses, instead of using an interpreter, Atiyah Asmal's young deaf character uses magic glasses as a way of transforming a hearing place into a signing space where he has access to communication. At the beginning of the story, the young deaf boy is rejected by the hearing children at the school where he is mainstreamed: he is not picked for any of the sports teams and is excluded from the soccer game. But then he finds some sparkly glasses, and when he puts them on, hearing children all start signing and he can understand everything they are saying - he is suddenly in a signing space where he can communicate. Similarly, when he puts on the glasses at home, the house is transformed into a signing space where his parents can sign.

As we can see from the examples above, the notion of transformation of (oppressive) "places" into (empowering) "spaces" is portrayed frequently in the SASL creative texts. The narrative of deaf identity is constructed through the process of actively engaging in creating a Sign-deaf or Sign-speak space.

4. Sensescapes

As we have seen above, audism is inherent in the portrayal of oralism as the Monster in deaf narratives. The majority of the poems transform the disempowered deaf protagonist into an empowered signing hero. However, deaf narrative identity can be established in a different way, focusing on their unique sensory orientation. The prioritising of vision as a means of self-identification through self-referencing terminology has been recognised since Veditz used the term "people of the eye" in his 1910 presidential address to the American National Association for the Deaf. Bahan later also used visual metaphors in his phrase "seeing people" (Bauman 2008: 12). Bahan (2006b) emphasised the unique sensory experiences of deaf people as an important theme in ASL literature. During a deaf story, characters (and performers, and sometimes also audiences) experience a shift in "sensescapes", a term coined by Rosen (2018). Instead of using the binary deaf and hearing spaces, the notion of 'sensescape' focuses on how deaf and hard-of-hearing (DHH) people navigate through space depending on their sensory orientation and the institutions' "culture of senses". A sensescape is an "institutional construction of the DHH body in space" (Rosen 2018: 64; our emphasis). This focus on the senses is broader than prioritising one's sense of vision, which thus excludes deaf-blind people.

In Rosen's article, sensescape is discussed in relation to the physical environment (how different institutions can be understood as exhibiting a particular sensescape). In this article, we use this term to refer to general sensory orientations of people as they navigate through the world. Hearing people rely on auditory sensecapes for communication. The sensescape of profoundly deaf people, on the other hand, relies heavily on vision and not on sound. Deaf-blind people experience the world in a tactile manner. Consequently, each sensescape will differ depending on the person's sensory orientation, the environment (in a bustling environment, even hearing people may need to communicate visually), and the person to whom they are talking.

The divide between hearing and deaf characters in the creative SASL text we discussed so far can be reinterpreted in terms of the different sensescapes in which they operate. In our stories, deaf characters are portrayed as strongly "seeing" people: their sensescape is primarily based on vision. Their struggle in the hearing world can be seen as a failure in operating in the auditory sensescape. For example, in Modiegi Moime-Njeyiyana's Deaf?, the protagonist/narrator first "sees" hearing people before approaching them (Figure 11a). While she is only seeing, she looks happy and willing to join the hearing world. However, when she actually meets them, she fails to communicate as she does not have access to information in the hearing world. All she can process in her sensescape is the cruel staring by hearing people (Figure 11b), similar to Carmen Fredericks and Helen Morgans' experiences as deaf protagonists (see Figure 3). The protagonist/narrator continues her attempt to visually navigate the hearing world, but only in vain (Figure 11c). At last, when she meets deaf people, her "seeing" tactics finally work, as they share the same sensescape of vision (Figure 11d).

Rosen (2018: 75) also highlights the fact that the visual sensescape of deaf people does not need to be contrasted with the auditory sensescape of hearing people:

The DeafWorld institutions do not build space in opposition to spaces in dominant, hearing society; instead, they use spaces that are created in the hearing society and impose their cultures and practices in the 'borrowed' spaces to the point of their alterity.

Belonging is a good example of a borrowed space (another way of referring to a "built environment") within the mainstream hearing space. The protagonist physically builds a castle and creates a DeafWorld within it. The castle is surrounded by singing and speaking people (an auditory sensescape) but inside it is a visual sensespace in which everyone operates using visual communication. The protagonist successfully altered the dominance of the institution's culture of senses by building a small, borrowed, empowering space within it.

The role of the interpreter can also be reinterpreted as someone who alters the sensescape of the place, and broadens access to information for those who operate in a visual sensescape. In Viva Access Viva!, different senses that occupy a public place are highlighted. Before the interpreter is brought in, deaf people are forced to navigate in a predominantly auditory sensescape - a large amount of information about the election is conveyed via speaking, chatting, and singing. The interpreter then transforms the sensory orientations of the place, and makes the same information available in SASL. The protagonists as well as the audience experience a shift in sensory orientation during the story - from primarily auditory to primarily visual. The sign language interpreter does not only translate the content but alters an existing sensescape - an aspect of interpreting that is not shared by spoken-language interpreters.

Lastly, although this is not the main focus of our article, we want to mention the important fact that all signed texts are created using the visual, spatial, and embodied modality of a sign language. Even when a shift in sensory orientation is not foregrounded in the story, the visual modality of sign language brings in a visual sensescape to the performance space. In other words, stories are told in sign language, in which characters are presented visually, often embodied (literally) on the body of the poet/storyteller, and audiences approach the performance visually as well. In this sense, all sign language narratives stimulate our sense of vision and create a visual sensescape.

5. Conclusion

In this article, we observed how deaf narrative identity (or identities) emerges in creative SASL texts. We first identified how difficulties in establishing deaf cultural identities in the hearingdominant world are represented in the "Man against Monster" plot (Booker 2004) commonly employed in sign language narratives. Then, we used De Certeau's (1984) notion of 'place versus space' and Heap's (2003) notion of 'Sign-deaf space' (plus our own term of "mediated Sign-speak space") to explore how deaf artists transform the Monster (i.e. the oppressive, hearing place) into deafhood and deaf space, which leads to the celebration of sign language and deaf culture. We also saw how the recent notion of 'sensescape', coined by Rosen (2018), can be used to reinterpret our own approach to deaf narrative identity. The Monster in deaf stories can be understood not only in terms of the audist ideology but also in terms of different sensory orientations between deaf and hearing characters.

Creative texts provide a wealth of opportunities to explore how narrative identities are constructed. In fictional stories, deaf narrators step back from being themselves, extract the essence of their shared experience and sublimate it into "a search for deafhood" which appeals to the deaf community. Various notions developed within the field of deaf studies - such as 'deafhood', 'deaf space', and 'deaf geographies'- are useful in (re-)interpreting existing texts and shedding a new light on them.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the deaf poets/storytellers whose creativity and all the work that they do is at the core of this article. We would also like to thank Sign Language Education and Development (SLED) for making their poems available to us for research purposes. We would especially like to acknowledge the talent of the late Modupe Miya whose work we discuss.

References

Bahan, B. 2006a. Face-to-face tradition in the American deaf community. In H-D. Bauman, J. Nelson and H. Rose (eds.) Signing the body poetic. California: University of California Press. pp. 21-50. [ Links ]

Bahan, B. 2006b. Making sense of ASL literature. Paper presented at Revolutions in Sign Language Studies: Linguistics, Literature, Literacy. Gallaudet University, Washington DC, 2224 March 2006.

Baker, A. 2017. Poetry in South African Sign Language: What is different? Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics 48: 87-92. https://doi.org/10.5774/48-0-282 [ Links ]

Baker, C. and C. Padden. 1978. ASL: A look at its history, structure, and community. Silver Spring, MD: T.J. Publisher. pp. 1-22. [ Links ]

Bauman, H-D. 2008. Introduction. In H-D. Bauman (ed.) Open your eyes: Deaf studies talking. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 1-34. [ Links ]

Bauman, H-D., J. Nelson and H. Rose (eds.) 2006. Signing the body poetic. California: University of California Press. pp. 21-50. [ Links ]

Booker, C. 2004. The seven basic plots: Why we tell stories. London: Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Brueggemann B.J. 2008. Think-between: A Deaf studies commonplace book. In K.A. Lindgren, D. DeLuca and D.J. Napoli (eds.) Signs and voices: Deaf culture, identity, language and arts. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press. pp. 30-42. [ Links ]

Brunner, E. 2013. Confessional poetry: A poetic perspective on narrative identity. In C. Holler and M. Klepper (eds.) Rethinking narrative identity: Persona and perspective. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. pp. 187-202. https://doi.org/10.1075/sin.17.11bru [ Links ]

Christie K, and D. Wilkins. 2007. Themes and symbols in ASL poetry: Resistance, affirmation and liberation. Deaf Worlds 22: 1-49. [ Links ]

De Certeau, M. 1984. The practice of everyday life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [ Links ]

DeafSA Literacy Project. 2000. VHS. Gauteng: DeafSA National Office. [ Links ]

Fekete, E. 2017. Embodiment, linguistics, space: American Sign Language meets geography. Journal of Cultural Geography 34(2): 131-148. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873631.2017.1305544 [ Links ]

Gulliver, M. and E. Fekete. 2017. Introduction to special edition on deaf geographies. Journal of Cultural Geography 34(2): 121-130. [ Links ]

Gulliver, M. and M. Kitzel. 2016. Deaf geographies. In G. Gertz and P. Boudreault (eds.) The SAGE deaf studies encyclopedia. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. pp. 451453. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483346489 [ Links ]

Heap, M. 2003. Crossing Social Boundaries and Dispersing Social Identity: Tracing Deaf Networks from Cape Town. Unpublished PhD dissertation, Stellenbosch University. [ Links ]

Hole, R. 2007. Narratives of identity: A poststructural analysis of three deaf women's life stories. Narrative Inquiry 17(2): 259-278. https://doi.org/10.1075/ni.17.2.06hol [ Links ]

Humphries, T. 1975. Audism: The making of a word: Audism. Available online: http://jjelley1.workflow.arts.ac.uk/artefact/file/download.php?file=1747574&view=165258 (Accessed 12 November 2019).

Kaneko, M. and R. Morgan. 2019. Izihlahla ezikhuluma ngezandla ('Trees who talk with hands'): Tree poems in South African Sign Language. Southern African Journal for Folklore Studies 29(1): 1-19. https://doi.org/10.25159/1016-8427/3794 [ Links ]

Klima, E. and U. Bellugi. 1979. The signs of language. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Kusters, A. and M. de Meulder. 2013. Understanding Deafhood in search of its meanings. American Annals of the Deaf258(5): 428-438. https://doi.org/10.1353/aad.2013.0004 [ Links ]

Ladd, P. 2003. Understanding deaf culture: In search of Deafhood. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [ Links ]

Ladd, P. 2015. Global Deafhood: Exploring myths and realities. In M. Friedner and A. Kusters (eds.) It's a small world: International deaf spaces and encounters. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press. pp. 274-286. [ Links ]

Lane, H. 1992. The mask of benevolence: Disabling the deaf community. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. [ Links ]

Leigh, I. 2009. A lens on deaf identities (Perspectives on deafness). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

McIlroy, G., and C. Storbeck. 2011. Development of deaf identity: An ethnographic study. The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 16(4): 494-511. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enr017 [ Links ]

Miya, M. 2014. Deaf people growing up. Poem performed at Signing Hands Across the Water. Digital raw footage housed at the SASL Department, University of the Witwatersrand. Filmed by Deaf Africa Website (Shush).

Morgan, R. (ed.) 2008. Deaf Me Normal: Deaf South Africans tell their stories. Pretoria: Unisa Press. [ Links ]

Morgan, R. 2014. A narrative analysis of Deafhood in South Africa. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 32(3): 255-268. https://doi.org/10.2989/16073614.2013.837615 [ Links ]

Morgan R. and M. Kaneko. 2017. Being and belonging as Deaf South Africans: Multiple identities in SASL poetry. African Studies 76(3): 320-336. https://doi.org/10.1080/00020184.2017.1346342 [ Links ]

Morgan R. and M. Kaneko. 2018. Deafhood, nationhood, and nature: Thematic analysis of South African Sign Language poetry. South African Journal of African Languages 38(3): 363-374. https://doi.org/10.1080/02572117.2018.1519993 [ Links ]

Morgan, R. and J. Meletse. 2017. Rainbow: Constructing a Gay Deaf Black South African identity in a SASL poem. African Studies 76(3): 337-359. https://doi.org/10.1080/00020184.2017.1346344 [ Links ]

Morgan, R., R. Moges, J. Meletse and D. Maasdorp. In press. "TROUSERS 2, DRESS 1": Performing intersecting Queer, Deaf, African identities in a signed renga (collaborative poem). Sign Language Studies.

Nathan Lerner, M., and D. Feigel. 2009. The heart of the hydrogen jukebox. DVD. Rochester Institute of Technology.

Padden, C. and T. Humphries. 2005. Inside Deaf culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Peters, C. 2000. Deaf American literature: From carnival to the canon. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press. [ Links ]

Rasebopye, L. 2014. A Deaf life. Poem performed at Signing Hands Across the Water. Digital raw footage housed at the SASL Department, University of the Witwatersrand. Filmed by Deaf Africa Website (Shush).

Rosen, R. 2018. Geographies in the American DeafWorld as institutional constructions of the deaf body in space: The sensescape model. Disability and Society 33(1): 59-77. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2017.1381072 [ Links ]

Sarikaya, D. 2011. The construction of Afro-Caribbean cultural identity in the poetry of Linton Kwesi Johnson. Journal of Caribbean Literatures 7(1): 161-175. [ Links ]

Setai, S. 2014. A Case Study of a Young Deaf Man's Identity Construction in a Hearing Family. Unpublished Master's Research Report, University of the Witwatersrand. [ Links ]

Sign Language Education and Development (SLED) Team. 2009. Preserving our signed heritage. DVD. Sign Language Education and Development.

Sign Language Education and Development (SLED) Team. 2017. SASL poetry. DVD. Sign Language Education and Development.

Stander, M. and G. McIlroy. 2017. Language and culture in the Deaf community: A case study in a South African special school. Per Linguam 33(1): 83-99. https://doi.org/10.5785/33-1-688 [ Links ]

Stokoe, W. 1960. Sign Language structure: An outline of the visual communication systems of the American Deaf. Studies in Linguistics: Occasional Papers (No. 8). Buffalo, NY: Department of Anthropology and Linguistics, University of Buffalo. [ Links ]

Sutton-Spence, R. 2005. Analysing sign language poetry. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Sutton-Spence, R. 2010. The role of sign language narratives in developing identity for deaf children. Journal of Folklore Research 47(3): 265-305. https://doi.org/10.2979/jfolkrese.2010.47.3.265 [ Links ]

Sutton-Spence, R. and M. Kaneko 2016. Introducing sign language literature: Folklore and creativity. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Sutton-Spence, R. and M. Kaneko. In press. Introduction to the special issue: Creative sign language in the southern hemisphere. Sign Language Studies.

Valentine, G. and T. Skelton. 2008. Changing spaces: The role of the internet in shaping deaf geographies. Social and Cultural Geography 9(5): 469-485. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649360802175691 [ Links ]

West, D. 2012. Signs of hope: Deafhearing family life. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [ Links ]

Woodward, J. 1972. Implications for sociolinguistic research among the deaf. Sign Language Studies 1: 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1353/sls.1972.0004 [ Links ]

1 As in our previous work (Morgan and Kaneko 2017, Morgan and Kaneko 2018, Kaneko and Morgan 2019) we use lowercase "deaf', as this has been the practice in deaf studies during the last decade. However, we emphasise that this does not refer to audiological deafness in the framework of the medical model. Instead, this signifies a move away from Woodward's (1972) essentialist binary of lowercase "deaf' signifying audiological deafness versus uppercase "Deaf' signifying cultural deafhood of sign language users. We follow the growing trend of lowercase "deaf' being used to signify the fluidity of deaf cultural identities being placed at multiple places anywhere along the continuum between "deaf' and "Deaf' (see Bauman 2008, Brueggemann 2008, West 2012). For consistency, we use "deafhood" even though Ladd (2003) capitalised the original term.

2 "Signed literary texts" refers to a body of creative signing with deliberately artistic use of language which can be differentiated from daily sign language usage. The study of signed language literature has been an established field of research since the 1980s (Klima and Bellugi 1979, Sutton-Spence 2005, Bauman, Nelson and Rose 2006, Nathan Lerner and Feigel 2009, Sutton-Spence and Kaneko 2016), and documentation of SASL literature has emerged over the last 20 years (Baker 2017, Morgan and Kaneko 2018, Sutton-Spence and Kaneko, in press).

3 Morgan and Kaneko (2018) collected these poems for research purposes to be used by staff and students at the Wits SASL Department. The material from DeafSA's Deaf Literacy project was converted from VHS format. The VHS tapes can be purchased from DeafSA's National Office. The SLED material can be purchased from SLED in DVD format. The Wits SASL Department has the unedited raw footage from SHAW 2 which was filmed by both Deaf Africa (Shush) as well as by Deaf TV. Deaf Africa has a few of the poems from SHAW 2 on their website.

4 Opposition to cochlear implants is strong in the deaf communities, especially in the US and Europe, as it is seen as an imposition of the audist ideology. Sometimes cochlear implants themselves are "personified" and become the Monster - see, for example, the BSL poem by Richard Carter entitled Cochlear Implant (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KskwGOyhLRQ).