Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus (SPiL Plus)

On-line version ISSN 2224-3380

Print version ISSN 1726-541X

SPiL plus (Online) vol.58 Stellenbosch 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.5842/58-0-847

PART III: TEXT-LINGUISTICS

Participation and decision-making at community development meetings: An appraisal of a subtle style in Luganda

Merit Kabugo

Department of Linguistics, English Language Studies and Communication Skills, Makerere University, Uganda E-mail: mkabugo91@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

This paper is based on corpus data from a study that was conducted in Uganda by the Center for Research on Environmental Decisions (CRED). Using a multi-perspective approach to spoken discourse analysis, the paper discusses the manifestations and patterns of participation and decision-making as they emerge through evaluation and appraisal in the context of participatory community development processes. Taking the discourse of farmer group meetings as a genre of business meetings, the paper explores how participants use Luganda to express assessment and make decisions during interactive discourse. In this paper, I discuss the manifestations of the subtle decision-making style, which demonstrates a culturally constructed concept of participation in Luganda. I refer to this culturally unique discursive process as the non-explicit style of participation and decision-making. The main characteristic of subtle decision-making discussions is that participants reach a consensus or take a spontaneous implicit group position on a matter without anyone formally announcing the decision.

Key words: Participation; meeting; decision-making; evaluation; discourse.

1. Introduction

Working in groups has particularly been emphasized by Governments, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and development agencies as an important component of participatory rural development and empowerment (Chambers 1974: 12; Iedema 1997: 73; Orlove et al. 2010: 243; Roncoli et al. 2011: 127). However, the process of rural development through groups brings with it new challenges of participation discourse of members at meetings (Cleaver 1999: 597; Hausendorf and Bora 2006a: 1, 2006b: 85; Roncoli et al. 2011: 123). One of the challenges is how different actors, including participants at community development project meetings, construe the notion of participation.

In a general sense, participation means to take part. It may also, according to Firth (1995: 3) and Sidnell (2010: 1), be viewed as ubiquitous talk by which we use language to negotiate, to argue, to persuade, to denigrate, to justify, to flatter, and so on. On the other hand, Merrit (as cited in Tannen 2007: 27) construes participation as mutual engagement, which is an observable state of being in coordinated interaction, as distinguished from mere co-presence. Participation may also be viewed as the expression of internal and emotional connections that bind individuals to other people, places, activities, memories and words (Duranti 1997: 20; Tannen 2007: 27).

Consequently, participation may be construed as the direct involvement of ordinary people in the affairs of planning, governance and overall development programs at local or grassroots levels (Williams 2006: 197). This notion of participation suggests that participatory discourse emerges whenever a decision-making process requires the public to be included in an activity of social decision-making (Firth 1995: 3; Hausendorf and Bora 2006a: 1; O'Mahony and O'Sullivan 2006: 72). In this respect, when people contribute dialogue, they demonstrate their allegiance to the group and their commitment to the ultimate goal of participation, which is to reach a consensus (Roncoli et al. 2011: 125).

However, participatory approaches especially among rural African communities may not always necessarily be beneficial to majority of the members of a community, even though community participation features as a key component of development programs at the local level (Roncoli et al. 2011: 127; Williams 2006: 197). This situation illustrates how the established relations of social dominance expressed through language may affect processes of persuasion and assent. In this case, participation relates to evaluation and appraisal in issues of negotiation, decision-making, and problem-solving through sharing and joining activities between the individual and larger reference groups. This view of participation raises the notion of citizenship, which is described as participation perceived by the participants themselves and manifested in their communicated images of self and others (Bora and Hausendorf 2006: 23; Fairclough et al. 2006: 98; Norris 2008: 134; Sbisa 2006: 151; Strauss 2005: 211).

2. Participation, community development and the discourse of meetings

One way that an individual may join the activities of a larger group and express citizenship is to participate in meetings. Meetings embody and provide a platform for various practices. In other words, meetings are the participatory frameworks through which a community can address its goals and develop its practice. Therefore, in the context of participatory community development, there is a need to explore the language that people use in meetings, and how this language may relate to and constitute the immediate and wider contexts in which meetings unfold. This is because meetings frequently involve the discussion of people, events and values that are referred to inexplicitly (Handford 2010: 76). In this sense, the discourse of meetings is a form of negotiation, involving discursive behaviors like topic control, turn-taking, argumentation, disagreement, and consensus-building (Bell 1995: 47; Firth 1995: 3; Morand 2000: 245). When participants argue and explain, they set up different versions of reality, and deal with each other's proposals for how those different versions might be resolved (Antaki 1994: 186; Mazzi 2006: 271; Smith and Bekerman 2011: 1683).

However, negotiations in meetings, like all other forms of social interaction, involve disagreement, requests, suggestions, persuasions, and other speech acts that are, in discursive terms, an effort to reach agreement and consensus within the cultural context of the participants and the situation (Eslami 2010: 217; Malamed 2010: 199; Martinez-Flor 2010: 257; Roloff et al. 2003: 803; Uso-Juan 2010: 237; Virtanen and Halmari 2005: 5). Therefore, if we are to accept that meetings are concerned with discussing, and sometimes solving real and hypothetical problems, we need to identify creative problem-solving and decision-making strategies through which participants get involved in the meeting process (Cortazzi and Jin 2000: 111; Handford 2010: 214; Patterson 2008: 37; Squire 2008: 43; Tannen 2007: 58).

Creative decision-making strategies at meetings entail the use of specialized discourse by which specific communities of practice manifest and demonstrate the notion of taking part in their practice. As Bhatia et al. (2008: 228) observe, discourse is one of the many cultural tools with which individuals act to get linked to their socio-cultural environments. Although Firth (1995: 35) explains that the term 'discourse' has been used in several different ways in language study, the specific sense that I adopt in this discussion defines it as 'the situated use of language-in-social-interaction'. With this working definition of discourse, I attempt to analyze a culturally constructed spoken discourse in order to understand and account for the realities of the world as we see them - complex, dynamic, and constantly changing. Unfortunately, the linguistic dimension of world knowledge is often ignored, although such knowledge of the world is associated with and invoked by language and other semiotic systems.

In other words, my aim of analyzing spoken discourse in this paper is to make explicit what is normally taken for granted and to show what talking accomplishes in people's lives and in society at large. After all, the overriding function of spoken language is to maintain social relationships, and until the characteristics of locally organized settings are investigated and explicated in appropriate detail, the extraction of language from them is a procedure with unknown properties and consequences. In particular, I examine how addressers construct linguistic messages for addressees and how addressees work on linguistic messages in order to interpret them (Flowerdew 2008: 115).

Although intercultural communication problems have been studied for a variety of reasons, there has been relatively little study to date of negotiation interactions in naturally-occurring situations. There is a need for more in-depth work on native speaker negotiation encounters, especially in less developed parts of the world (Biber 2008: 102; Marriott 1995: 267). I attempt to address the above concerns by contributing to the analysis of the evaluative discourse of Luganda in meetings. My analysis sheds light on the ways in which a culturally-constructed understanding of participation is reflected in its actual use (Bednarek 2010: 13; Handford 2010: 204; Martin and White 2005: 1; Thompson and Hunston 2000: 10).

By discussing the non-explicit sub-genre of the evaluative discourse of Luganda meetings in the context of participatory community development processes, I make an attempt to answer the following questions: What is participatory discourse? Who participates and how do they participate? How are decisions reached?

3. Theoretical and methodological points of departure

Considering theories of speech acts (Levinson 1983; Martinez-Flor and Uso-Juan 2010) and the methodological conventions of conversation analysis (Cameron 2001; Drew and Curl 2008), as well as the prerequisite requirements of corpus linguistic analysis (Biber et al. 2007; O'Keeffe and McCarthy 2010), my discussion and analysis generally falls within the domain of spoken discourse analysis. I regard spoken discourse analysis as a research design under which I explore the discursive patterns of participation and decision-making among rural communities in a meeting setting. I specifically invoke the appraisal theory (Martin 1997; White 2002; Martin and White 2005; Bednarek 2008), to explore the social functions of language.

4. Analysis of findings

In this section, I analyze and discuss one meeting to track the patterns of participation, decisionmaking, and evaluation within the context of meetings on rural community development work. This meeting demonstrates an indigenous African or a subtle decision-making mode of discussion, where participants reach consensus or take an implicit group position on a matter without anyone formally announcing that the position is a decision. The analysis gives an introductory overview of the meeting, provides a multi-perspective template of the appraisal and generic move structure of the meeting, and thus presents a detailed analytical characterization of the meeting. The section concludes with a summary of the multi-perspective trends that emerge from the 'subtle decision-making' cluster of meetings.1

4.1 Overview of the meeting

The meeting does not have a formal opening, but there is a chairman (Male 1) who, after a recorded weather forecast is played, opens the discussion by stating that he wonders whether crops will grow to maturity, in light of the weather forecast that has been presented. Other members follow by reacting to the chairman's statement and subsequently taking turns to assess the implications of the weather forecast to their farm work. The reaction to the chairman's statement as well as the subsequent spontaneous turns in the discussion (as I illustrate later) demonstrate the role of repetition in enhancing the production and comprehension of discourse, as well as facilitating connection and interaction among participants. The functions of repetition in this respect support Tannen's (2007: 101) contention that one cannot understand the full meaning of a conversational utterance without considering its relation to other utterances, in its discourse environment as well as in prior text. There is a free expression of a wide range of opinions and turn-taking regarding what to plant and when. Male 1, Male 2, and Male 4 attempt to close the discussion at various stages, but the discussion is re-opened by other members who either persist to conclude an unconcluded topic or raise a new topic all together.

Decisions are made in subtle ways, without clear moments of conclusion. Participants negotiate for their positions in the discussion freely. The taking of turns is spontaneous, except in a few instances when a participant tries to moderate the discussion by reflexively inviting fellow participants to take turns. The meeting closes when members have no more contributions to make, and after several speech turns in which various participants express an agreement to end the discussion. There is no formal announcement from the chair or any other participant about the end of the discussion. Rather, there is the use of a metaphor - egenda kutumwa enviiri (hunger is going to shave off our hair) - which expresses the view that farmers are bound to have poor harvests because there is likely to be little rain for the crops during the coming rain season. After the citation of the metaphor, participants raise no more opinions on the debate, apart from taking recursive turns to express their concurrence and end the discussion.

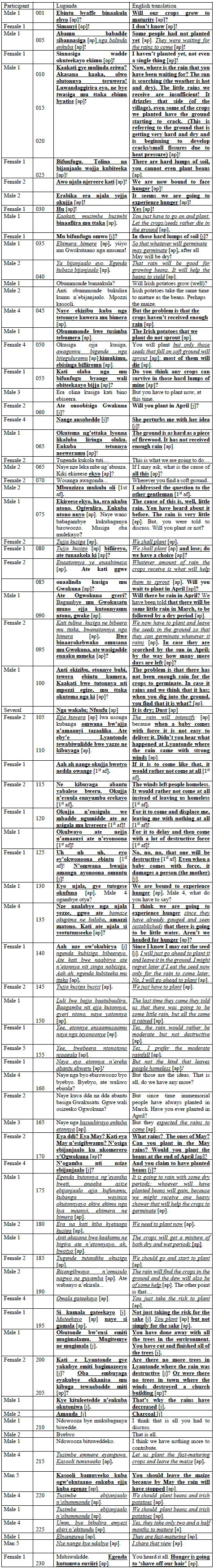

4.2 Analytical template of appraisal resources and the generic move structure of the meeting

4.3 Analytical perspectives on appraisal, participation, and decision-making

Participants, through inscribed and invoked appreciation and judgment, concur on their critical evaluation of the weather forecast, which is that 'the rain will be too little to sustain a full crop cycle' and for that matter 'the community is bound to face hunger'. This negative attitude is illustrated, through the expression of despair and lament, by various participants in different turns (Male 1: 001-013, 048-9, 061-3, 070, 093-6, 123; Female 1: 003, 007, 023-4, 054-5, 0767, 216; Female 2: 026, 079-080; Male 2: 028; Male 4: 045, 059, 126-9; Female 4: 052). The negative attitude is made more clear by a collective assessment 'nga wakalu; nfuufW (it is dry; dust: 104), which is a 'consensus' appraisal of the situation. The assessment is concluded with a metaphor (230), which also serves to close the discussion.

Indeed, before the concluding metaphor, other metaphors (106-7, 127-8) are employed as resources of evaluation to express negative attitudes toward extreme weather conditions. While - egenda kutumwa enviiri (hunger is going to shave off our hair: 230) - is invoked to express 'serious' concern about the potential impact of insufficient (too little) rain to the crops and consequently to the community, a similar 'magnitude' of concern is expressed about the impact of excessive (too much) rain when - omwanabw 'ajjan'amaanyi tazaalika(when a baby comes with force it is not easy to deliver it: 106-7) and n'omwana bwajja amangu ayonoona omuntu (when a baby comes with force, it damages a person - the mother: 127-8) - are invoked.

The metaphors allude to practical, fearful, and unwanted experiences of the ordinary lives of participants, hence making the discussion less abstract. Thus, the precision with which the three metaphors capture the properties of negative attitude which the participants intend to express in this meeting illustrates Handford's (2010: 204) argument that "cultural allusions and metaphors tend to be extremely evaluative."

At a lexico-grammatical level, the negative attitude is particularly expressed through the recursive use of specific linguistic units as negative keywords, most notably the following: the negative marker si-/te- (not: 003, 005, 007, 023, 046, 049, 099), food noun njala (hunger: 026, 028, 126, 130, 133), weather verb -aaka/-okya (scorch: 010, 094), weather nouns sana (sun: 010, 094) and kibuyaga (wind: 110, 115, 202), adjectives -sana/-kalu (dry: 036, 094, 104) and -tono (little: 012, 090, 136, 149), nouns kizibu (problem: 045, 098) and maanyi (force: 107, 123, 128), verb onoon- (destroy: 123, 128, 152, 201, 203).

However, through inscribed appreciation, participants make an implied group decision to take the risk and plant their crops (Male 1: 031; Female 2: 079, 086, 138, 173; Female 1: 080; Male 2: 169; Male 4: 206; Male 5: 215). The decision can be regarded as a group decision because it is suggested and reiterated by various participants in different turns. The reiteration of the 'decision-making' phrase is a form of repetition which, according to Tannen (2007: 61), does not only tie parts of discourse to other parts, but also bonds participants to the discourse and to each other, linking individual speakers in a conversation and in relationships. The implied group decision is particularly expressed through the reiteration of the following positive keywords:

farm verbs simb-lsig- (plant: 031, 057, 079, 080, 091, 140, 145, 181, 214, 220), mer-ltegulur-(germinate/sprout: 035, 052, 082, 093), weather verb tonny- (rain: 082, 093, 142, 156, 166, 173), modal verb -jja (shall: 079, 080).

The lamentation (001-030, 090-099, 123), desperation (076, 126-130, 216), as well as the consensus to take the risk to plant (075-6, 086-7, 169, 200-215) build a platform for constructing a group identity, which is expressed by the consistent use of "tu-" (we) in the dialogues. The group identity is especially reaffirmed by the use of the metaphor - egenda kutumwa enviiri (hunger is going to shave off our hair: 230) - which is a moment to express 'inclusive' humor and also to close the discussion.

The position of the "concerned individual" that is assumed by participants in the above-cited cases of constructing group identity is an expression of citizenship as a collective and participatory decision-making process. Indeed, when Female 1 tries to show hesitation (054-6) about the 'collective decision' of taking the risk to plant, she is judged by Male 3 (057) and Female 2 (059) as proposing an outrageous idea which is against group consensus and therefore against the spirit of group identity. The negative judgment of Female 1 is confirmed by Female 4 who explicitly retorts - nange ansobedde! (she perturbs me with her idea: 061). In this segment, Female 1 is isolated as a bad member of the group.

The cognitive move structure of the discussion presents in three juxtaposed parts - i) evaluation of the weather forecast and its implications for the community (001-030, 045-090); ii) critical reasoning on the state of affairs (091-171); iii) decision-making and closure of discussion (031040, 173-230). The totality of constitution of the three parts of the discussion arises from the iterative nature of their respective cognitive moves. Two of the metaphors (106-7, 127-8) which I mentioned above come in the second segment of the meeting where participants endeavor to make sense of the apparently complex weather-related phenomena.

The understanding of the complex phenomena is facilitated by the use of the two metaphors, in which case, as Tannen (2007: 2) argues, creativity in problem-solving serves as the "sound or music of language, by means of which hearers and readers are rhythmically involved, and at the same time involved by participating in the making of meaning." Another metaphor (216) comes in the third segment of the meeting and after it is invoked the discussion closes. In this sense, interpersonal creativity is used not only to affirm group identity, but also to summarize a position.

A further look at the cognitive move structure of this meeting also reveals that the chairperson (Male 1) does not assume his role as moderator to open the meeting. Instead, the chairperson takes the first turn to contribute to the debate and then he leaves other members to spontaneously take turns to participate in the discussion. Similarly, the chairperson does not take the last turn to close the discussion. However, the chairperson takes occasional intervals (041, 073, 132) to moderate the discussion by controlling turns and topics, as well as to close the discussion (212). All participants, including the chairperson, take their discursive turns in a spontaneous manner, without having to seek the permission of the chair. The spontaneous nature of taking turns further illustrates the sense of oneness and citizenship among the participants, because through it members demonstrate both their individual and collective 'belonging' to the group by allowing an orderly exchange of speech turns.

5. Conclusion

The analysis of this meeting reveals that through spontaneous turn-taking, subtle decision-making, and the citizenship position of a "concerned individual", participants work towards consensus-building through which they construct and cement a strong group identity. The analysis highlights the relationship between participatory discourse and participatory community development which proves that participation at a meeting may be expressed through interaction with other participants by way of a discussion style in which a specific point is shaped by several participants rather than a single turn and enunciated by one individual. When participants contribute to the dialogue, they demonstrate their allegiance to the group and their commitment to the ultimate goal of participation, which is to reach consensus. By manipulating specific linguistic resources of appraisal, participants are able to approve or disapprove, applaud or criticize, and share their emotions and tastes, as well as create attitudinal positions which they wish their listeners to adopt.

References

Antaki, C. 1994. Explaining and Arguing: The Social Organization of Accounts. London: SAGE. [ Links ]

Bednarek, M. 2010. Evaluation in the news: A methodological framework for analysing evaluative language in journalism. Australian Journal of Communication 37(2): 15-50. [ Links ]

Bednarek, M. and H. Caple. 2010. Playing with environmental stories in the news - good or bad practice? Discourse and Communication 4(1): 5-31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481309351206 [ Links ]

Bell, D.V. 1995. Negotiation in the Workplace: The view from a political linguist. In A. Firth (ed.) The Discourse of Negotiation: Studies of Language in the Workplace. Oxford: Pergamon. pp. 41-58. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-08-042400-2.50008-x [ Links ]

Bhatia, V.K., J. Flowerdew and R.H. Jones. 2008. Approaches to discourse analysis. In V.K. Bhatia, J. Flowerdew and R.H. Jones (eds.) Advances in Discourse Studies. London/New York: Routledge. pp. 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9841.2009.00438_4.x [ Links ]

Biber, D. 2008. Corpus-based analyses of discourse: Dimensions of variation in conversation. In V.K. Bhatia, J. Flowerdew and R.H. Jones (eds.) Advances in Discourse Studies. London/New York: Routledge. pp. 100-114. [ Links ]

Chambers, R. 1974. Managing Rural Development: Ideas and Experiences from East Africa. Uppsala: The Scandinavian Institute of African Studies. [ Links ]

Cleaver, F. 1999. Paradoxes of participation: Questioning participatory approaches to development. Journal of International Development 11: 597-612. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1099-1328(199906)11:4<597::aid-jid610>3.0.co;2-q [ Links ]

Cortazzi, M. and L. Jin. 2000. Evaluating evaluation in narrative. In S. Hunston and G. Thompson (eds.) Evaluation in Text: Authorial Stance and the Construction of Discourse. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 102-120. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614456020040041104 [ Links ]

Drew, P. and T. Curl. 2008. Conversation analysis: Overview and new directions. In V.K. Bhatia, J. Flowerdew and R.H. Jones (eds.) Advances in Discourse Studies. London/New York: Routledge. pp. 22-35. [ Links ]

Duranti, A. 1997. Linguistic Anthropology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Eslami, Z.R. 2010. Refusals: How to develop appropriate refusal strategies. In A. Martinez-Flor and E. Uso-Juan (eds.) Speech Act Performance: Theoretical, Empirical and Methodological Issues. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. pp. 217-236. https://doi.org/10.1075/lllt.26.13esl [ Links ]

Fairclough, N., S. Pardoe and B. Szerszynski. 2006. Critical discourse analysis and citizenship. In H. Hausendorf and A. Bora (eds.) Analysing Citizenship Talk: Social Positioning in Political and Legal Decision-Making Processes. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. pp. 98-123. https://doi.org/10.1075/dapsac.19.09fai [ Links ]

Firth, A. 1995. The discourse of negotiation: Studies of language in the workplace -Introduction and overview. In A. Firth (ed.) The Discourse of Negotiation: Studies of Language in the Workplace. Oxford: Pergamon. pp. 3-39. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0047404500019291 [ Links ]

Flowerdew, J. 2008. Critical discourse analysis and strategies of resistance. In V.K. Bhatia, J. Flowerdew and R.H. Jones (eds.) Advances in Discourse Studies. London/New York: Routledge. pp. 195-210. [ Links ]

Handford, M. 2010. The Language of Business Meetings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Hausendorf, H. and A. Bora. 2006a. Analysing citizenship talk: Introduction. In H. Hausendorf and A. Bora (eds.) Analysing Citizenship Talk: Social Positioning in Political and Legal Decision-Making Processes. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. pp. 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1075/dapsac.19.04bor [ Links ]

Hausendorf, H. and A. Bora. 2006b. Reconstructing social positioning in discourse: Methodological basics and their implimentation from a conversation analysis perspective. In H. Hausendorf and A. Bora (eds.) Analysing Citizenship Talk: Social Positioning in Political and Legal Decision-Making Processes. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. pp. 85-97. https://doi.org/10.1075/dapsac.19.08hau [ Links ]

Iedema, R. 1997. The language of administration: organizing human activity in formal institutions. In F. Christie and J. Martin (eds.) Genre and Institutions: Social Processes in the Workplace and School. London/New York: Continuum. pp. 73-100. [ Links ]

Malamed, L.H. 2010. Disagreement: How to disagree agreeably. In A. Martinez-Flor and E. Uso-Juan (eds.) Speech Act Performance: Theoretical, Empirical and Methodological Issues. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. pp. 199-215. https://doi.org/10.1075/lllt.26.12mal [ Links ]

Marriott, H.E. 1995. 'Deviations' in an intercultural business negotiation. In A. Firth (ed.) The Discourse of Negotiation: Studies of Language in the Workplace. Oxford: Pergamon. pp. 247268. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-08-042400-2.50016-9 [ Links ]

Martin, J. 1997. Analysing genre: functional parameters. In F. Christie and J. Martin (eds.) Genre and Institutions: Social Processes in the Workplace and School. London/New York: Continuum. pp. 3-39. [ Links ]

Martin, J. and P. White. 2005. The Language of Evaluation: Appraisal in English. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Martinez-Flor, A. 2010. Suggestions: How social norms affect pragmatic behaviour. In A. Martinez-Flor and E. Uso-Juan (eds.) Speech Act Performance: Theoretical, Empirical and Methodological Issues. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. pp. 257-274. https://doi.org/10.1075/lllt.26.15mar [ Links ]

Martinez-Flor, A. and E. Uso-Juan. 2010. Pragmatics and speech act performance. In A. Martinez-Flor and E. Uso-Juan (eds.) Speech Act Performance: Theoretical, Empirical and Methodological Issues. Amsterdam/Philadephia: John Benjamins. pp. 3-20. https://doi.org/10.1075/lllt.26.01mar [ Links ]

Mazzi, D. 2006. "This is an attractive argument, but...". Argumentative conflicts as an interpretive key to the discourse of judges. In V.K. Bhatia and M. Gotti (eds.) Explorations in Specialized Genres. Bern: Peter Lang. pp. 271-290. [ Links ]

Morand, D.A. 2000. Language and power: an empirical analysis of linguistic strategies used in superior-subordinate communication. Journal of Organizational Behavior 21: 235-248. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1099-1379(200005)21:3<235::aid-job9>3.0.co;2-n [ Links ]

Norris, S. 2008. Some thoughts on personal identity construction: A multimodal perspective. In V.K. Bhatia, J. Flowerdew and R.H. Jones (eds.) Advances in Discourse Studies. London/New York: Routledge. pp. 132-148. [ Links ]

O'Keeffe, A. and M. McCarthy. (eds.). 2010. The Routledge Handbook of Corpus Linguistics. London/New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

O'Mahony, P. and S. O'Sullivan. 2006. Procedure and participation: A social theoretical assessment of GM licensing procedures in Ireland and the UK. In H. Hausendorf and A. Bora (eds.) Analyzing Citizenship Talk: Social Positioning in Political and Legal Decision-Making Processes. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. pp. 61-82. https://doi.org/10.1075/dapsac.19.06oma [ Links ]

Orlove, B.S., C. Roncoli, M.R. Kabugo and A. Majugu. 2010. Indigenous climate knowledge in southern Uganda: The multiple components of a dynamic regional system. Climatic Change 100: 243-265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-009-9586-2 [ Links ]

Patterson, W. 2008. Narratives of events: Labovian narrative analysis and its limitations. In M. Andrews, C. Squire and M. Tamboukou (eds.) Doing Narrative Research. Los Angeles: SAGE. pp. 22-40. https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857024992.d3 [ Links ]

Roloff, M.E., L.L. Putnam and L. Anastasiou. 2003. Negotiation skills. In J.O. Greene and B.R. Burleson (eds.) Handbook of Communication and Social Interaction Skills. New Jersey/London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 801-833. [ Links ]

Roncoli, C., B.S. Orlove, M.R. Kabugo and M.M. Waiswa. 2011. Cultural styles of participation in farmers' discussions of seasonal climate forecasts in Uganda. Agriculture and Human Values 28(1): 123-138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-010-9257-y [ Links ]

Smith, W.B. and Z. Bekerman. 2011. Constructing social identity: Silence and argument in an Arab -Jewish Israeli group encounter. Journal of Pragmatics 43: 1675-1688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.11.009 [ Links ]

Squire, C. 2008. Experience-centred and culturally-oriented approaches to narrative. In M. Andrews, C. Squire and M. Tamboukou (eds.) Doing Narrative Research. Los Angeles: SAGE. pp. 41-63. https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857024992.d4 [ Links ]

Strauss, C. 2005. Analyzing discourse for cultural complexity. In N. Quinn (ed.) Finding Culture in Talk: A Collection of Methods. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 203-242. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-05871-3_6 [ Links ]

Tannen, D. 2007. Talking Voices: Repetition, Dialogue, and Imagery in Conversational Discourse (Second ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511618987 [ Links ]

Thompson, G. and S. Hunston. 2000. Evaluation: An introduction. In S. Hunston and G. Thompson (eds.) Evaluation in Text: Authorial Stance and the Construction of Discourse. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1-27. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614456020040041104 [ Links ]

Uso-Juan, E. 2010. Requests: A sociopragmatic approach. In A. Martinez-Flor and E. Uso-Juan (eds.) Speech Act Performance: Theoretical, Empirical and Methodological Issues. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. pp. 237-256. https://doi.org/10.1075/lllt.26.14uso [ Links ]

Virtanen, T. and H. Halmari. 2005. Persuasion across genres: Emerging perspectives. In H. Halmari and T. Virtanen (eds.) Persuasion Across Genres: A Linguistic Approach. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. pp. 3-24. https://doi.org/10.1075/pbns.130.03vir [ Links ]

White, P.R. 2002. Appraisal. Available online: http://www.benjamins.com.ez.sun.ac.za/ (Accessed 17 May 2011).

Williams, J.J. 2006. Community Participation: Lessons from post-apartheid South Africa. Policy Studies 27(3): 197-217. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442870600885982 [ Links ]

1 The following typeface conventions, as adopted and modified from Thomson et al. (2008: 70), are employed in the analysis of appraisal resources and generic properties of the meeting: bold underlining - inscribed (explicit) negative attitude; bold - invoked (implied) negative attitude; italics underlined - inscribed positive attitude; italics - invoked positive attitude. The sub-type of attitude is indicated in square brackets immediately following the relevant span of text: [j] = judgment (positive/negative assessments of human behavior in terms of social norms); [ap] = appreciation (positive/negative assessments of objects, artifacts, happenings and states of affairs in terms of systems of aesthetics and other systems of social valuation); [af] = affect (positive/negative emotional responses); 1 af = first-person or authorial affect; 3 af = observed affect, i.e. the participant describing the emotional responses of third parties.