Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus (SPiL Plus)

On-line version ISSN 2224-3380

Print version ISSN 1726-541X

SPiL plus (Online) vol.58 Stellenbosch 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.5842/58-0-846

PART III: TEXT-LINGUISTICS

The 'rise and fall' of a genre: The generic and rhetorical renditions of a Runyankore-Rukiga editorial

Levis Mugumya

Linguistics, English Language Studies and Communication Skills, Makerere University, Uganda E-mail: lmugumya@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

This article explores the discursive practice of editorial writing in Runyankore-Rukiga print media. It also explicates the generic structure of Runyankore-Rukiga editorial text and the rhetorical devices that the editorial writers have invoked to comment on issues that affect society across different times of history. Using genre analysis, the article analyses a diachronic corpus of editorial texts across Ugandan local newspapers from 1955 to 2010. The article demonstrates that while the construction of a Runyankore-Rukiga editorial appears to conform to the architectural structure of an English editorial (Ansary and Babaii 2005), it does not adhere to its rhetorical moves and the attendant argumentation principles that govern the construction of an editorial text. During the early years (1960s) and throughout the 1970s of Runyankore newspaper writing, the editorial text was a significant genre often appearing on the front page and largely characterized by rhetorical moves consisting in religious and biblical propositions. The editorialists have occasionally employed proverbs to premise or reinforce their arguments, but also to bring humour to the text. The contemporary editorial text also exemplifies use of conversational language, a discursive style that appears to identify with and endear it to putative readers. While the genre has been in constant flux, Runyankore-Rukiga print media outlets have discontinued editorial writing because of commercial reasons and apprehension concerning the consequences of articulating issues that disfavour policies and undertakings of a coercive government. The article reiterates the significance of editorial writing in newspaper discourse and advocates continued articulation of other non-political issues that do not necessarily endanger print media praxis.

Keywords: Editorial; genre analysis; generic structure; rhetorical strategies; Runyankore-Rukiga; argumentation.

1. Introduction

This article traces the evolution of editorial writing in newspaper discourse. Drawing from a corpus of editorials across the Runyankore-Rukiga print media, it explores the rhetorical and generic features that newspaper editorialists have invoked to construct editorial texts. The article analyses a diachronic corpus of editorials from the colonial times to-date. The study is underpinned by the various architectural changes that have characterized the editorial text and the nature of rhetorical strategies that are employed to promote arguments, which do not conform to the Anglo-American 'proto-type'. Secondly, editorial genres are no longer valorized in Runyankore-Rukiga newsprint because they were discontinued since 2010. Therefore, it is crucial to explore the evolution of such a genre back to its antecedents in order to reveal "the nature of the genre and its situational and cultural origins as well" (Devitt 2004: 92).

The study is based on the notion of genre, which is conceived from systemic functional linguists (SFL). Therefore, it invokes genre theory and genre analysis to analyse and explicate the textual architecture and linguistic resources used to construct editorials in Runyankore-Rukiga news discourse (see Bawarshi and Reiff 2010). As Bhatia (2004: 10) aptly notes, genre analysis is significant because it allows one to "understand how members of specific discourse communities construct, interpret and use genres in order to accomplish a communicative purpose and why they write them the way they do". Similarly, genre knowledge enables one to comprehend "the social and cultural contexts in which genres are located" and understand how such factors relate to the "language choices" users make (Paltridge 2002).

Genre theory highlights the relationship "between genres and institutions, power, the construction of subjectivity, as well as 'relations it permits/enables/constrains and refuses between readers and writers ..." (Bawarshi and Reiff 2010). Genre is conceived in terms of the goal(s) it intends to achieve. It is construed as a social process because the users interact to realise them, and as a staged activity unfolding in stages/moves through which genre users go to accomplish them. Therefore, genres are regarded as "staged, goal-oriented social processes through which subjects in a given culture live their lives" (Eggins and Martin 1997; Martin and Rose 2003: 7-8). The analysis of genres involves examining the stages through which the genre is realised and the lexicon and grammar that identify these steps. This article focuses on two aspects of genre study, namely the social context within which the genre is realised and the dynamic nature of genres. The social context or environment is critical to genre study because it enables us to understand the construction and use of a given genre (Halliday 1984; Bednarek 2006). The environment comprises the customs, ideologies, values, goals, and beliefs, which are normally reflected in various genres (Devitt 2004; Berkenkotter and Huckin 1995). Most importantly, genres reveal various methods that genre users employ to accomplish things continually via language use (Martin 2009). Therefore, the social context informs the construction of genres. Context is crucial to this study because it explains the variability between an English editorial and a Runyankore-Rukiga one, thereby explicating the socio-cultural features that bring about the differences. The study also argues that the changing context also underpins the dynamic nature of the rhetorical structure and rhetorical devices invoked at different epochs.

Runyankore-Rukiga constitutes one of the five major languages of wider communication in Uganda, including Lugbara, Luganda, Luo and Ngakarimajong. According to the 2002 population census, 2,330,000 speakers speak Runyankore, whereas 1,580,000 speak Rukiga (UBOS 2002). The 2014 population does not provide statistical information relating to languages spoken in Uganda; however, it rates Banyankore people who should be speaking Runyankore-Rukiga at 10 per cent coming second after the major ethnic group, Baganda (17 per cent). This does adequately indicate the approximate number of speakers because not all those who are identified as 'Banyankore' necessarily speak or use Runyankore. However, the language is taught at both primary and secondary school levels as well as at Makerere University. Besides being used in print media, Runyankore-Rukiga is used as a broadcasting medium for many FM radio stations in south-western Uganda. It is also widely spoken throughout western Uganda and is understood in north-western Tanzania and the eastern areas of the Democratic Republic of Congo (Paul 2009).

2. The dynamic nature of genres

Whereas some genres are homogenous and comprise somewhat stable texts with defined generic structures because they emanate from stable discourse communities, others are in constant flux and susceptible to change (Myers 2000; Fairclough 2003). Societies, within which genres are enacted exhibit beliefs, cultures, and values which evolve over time; genres respond to these changes (Miller 1994; Devitt 2004). Several studies on genres have demonstrated how genres have evolved with time, including the scientific research article (Swales 1990), promotional traits that have permeated the scientific research article (Bhatia 1993, 2004), change in the generic structure of a job interview (Kress 1993), and changes in a letter and electronic email genres (Ramanathan and Kaplan 2000; Gillaerts and Shaw 2006). Other genre changes have been recognised in memoranda, company manuals, and business reports (Devitt 2004). For example, a circular letter changed the format from a "salutation to a heading" while "the memoranda and business reports became impersonal, direct, matter-of-fact, rather than personal, courteous, or cordial" (Devitt 2004: 105). White (2000: 72) argues, "modes of journalistic textuality are not static but are in a constant state of modification and reformulation as they respond to changing social conditions". For example, until the mid-19th century, the news story unfolded as a chronological narrative recounting events as they unfolded in real time, while the contemporary news story follows a non-linear structure (Feez, Iedema and White 2008). Studies on the dynamic nature of editorial texts are almost non-existent; therefore, this study explicates the dynamic nature of this genre within a changing situational and cultural context that dictates its construction.

Genres are not only prone to change but as they do so, they are also open to possible innovations and creativity (Kress 1993). These changes could be internal and not complete changes that result in a new genre altogether, but they could also entail loss of qualities or even gaining some new features aimed at improving a genre. In this regard, genres acquire or embed features of other genres, a phenomenon that has been labelled 'genre mixing'. Genre mixing occurs when features of one genre interlope with some elements of a hybrid text (Hyland 2002; Bhatia 2004). For example, some promotional features have permeated academic genres such as book introductions (Bhatia 2004). University prospectuses, job advertisements, and academic introductions have been interloped with promotional features because of the consumerism culture prevailing in society (Norlyk 2006; Bhatia 2000). Similarly, the editorialising feature has been identified in news reports, which are expected to exemplify objectivity (Bhatia 1997; Wang 2008).

Genre change notwithstanding, genre users usually adopt their own ways of constructing genres, which usually deviate from established genre norms and prototypes to achieve their private intentions (Gillaerts and Shaw 2006; Bhatia 2004).

In view of this notion of genre change, the article does not only examine the generic and linguistic changes that characterise Runyankore-Rukiga editorial genre, it also explores the non-conventional rhetorical styles (private intentions) that the editorial writers invoke, thus rendering the genre different from other editorials.

3. Editorial writing in newspaper discourse: Generic structure and rhetorical strategies

The journalistic editorial genre belongs to the media exposition (commentary) and is a sub-genre of argumentative genres. Newspaper discourse entails other editorial genres including commentary (opinion) articles, which are beyond the scope of this article. Editorials are routinized argumentative genres that are critical in newspaper discourse and research because they function as opinion formation and persuade by argument (Caffarel-Cayron and Rechniewski 2014). An archetypal editorial appears under the newspaper's name and logo and through occupying this prime place; it implies that it is the paper's voice (Vestergaard 2000).

The editorial genres slightly deviate from other newspaper genres such as news reports. The distinction largely lies in their communicative purposes. Indeed, the communicative goal underpins the identification of texts as specific genres (Bhatia 1993; Askehave and Swales 2001). For example, the news reports' communicative goal consists of conveying news events in an objective fashion. The editorial genre of opinion and commentary in news discourse, which usually emanates from journalists as well as other writers, is to "offer up subjective interpretations in which a central role is played by explicit value judgements, aesthetic evaluations, theories of cause and effect..." (White 1997: 107). These genres overtly express interpersonal meanings unlike other news reports. The writer aims to persuade the reader to agree or disagree with their point of view on a given event or issue (Murphy and Morley 2006). Ordinarily, such standpoints are similar to the ideologies of the media outlets/newspapers within which the editorials appear (Wang 2008).

An editorial expresses the value positions or official position of a given media outlet (Wang 2008), usually employing linguistic techniques that "create favourable or unfavourable bias" in the editorialist's point of view (Bhatia 1993: 170). It usually communicates the newspaper's stance on a contemporary issue, thus reflecting the ideological positioning in society, which endears it to its 'readers'. The editorial "bolsters readers' prejudices ... and contribute to retaining reader's custom" . it caters to "readers' interests, concerns and points of view" (Reynolds 2000: 27).

This study is cognizant of the fact that a genre exhibits several communicative events, which aim to convey a specific communicative goal. Therefore, it does not take the notion of communicative purpose for granted because some genres can combine functions, while genre mixing may also occur to realise private intentions (Bhatia 2004). Whereas there is always a predominant communicative goal in a given genre, the communicative purpose may not even be one of them, and editorials could have several communicative purposes (Askehave and Swales 2001). For example, while the primary purpose of a book introduction is to provide the purpose of the book and its scope and target audience (academic purpose), it may entail 'minor purposes' intended to promote the book (Bhatia 1995, 1996). Bhatia exemplifies other promotional genres (advertisements, promotional letters, job applications) that may comprise an overlapping communicative purpose of promoting a product or service (Bhatia 1996). Thus, the change in the communicative purposes does not necessarily change the genre itself.

The newspaper editorial has been researched extensively (Bhatia 1993; Bolivar 1994; Reynolds 2000; Ansary and Babaii 2005; Le 2008, 2010; Caffarel-Cayron and Rechniewski 2014) examining the generic structure of largely English and French editorials. Riaz and Asar (2000) cited in Le (2008) extended the analysis to Persian editorials. Newspaper editorial writers invoke specific linguistic devices to express their unconcealed standpoints on current events and issues in order to influence putative readers. Whereas argument is a predominant feature in editorial writing, the English editorial text also engenders narrative and descriptive modes (Reynolds 2000). The lead segment exhibits nominal expressions to refer to previous or contemporary events and issues, which are familiar to the reader (Vestergaard 2000). The editorialist employs explicit evaluations of events (less of human conduct) (Lihua 2009) based on the good or bad values and likely consequences without attributing them to an external source. Furthermore, the editorialist proposes suggestions to avert or improve the prevailing undesirable situations. The writers often invoke predictability, necessity, certainty and probability modal expressions to convey their vantage points.

Studies on editorial writing demonstrate that while the English editorial is homogeneous and has a definable generic structure; apparently, the non-English editorials exhibit variations (Persian, French) in their rhetorical structure. Bolivar's (1994) study of English editorials (Guardian) favoured the 'triad' structure, which comprised the Lead (focused on the issue and stance), Follow (responds to the issue) and Valuate (evaluates the issue). Ansary and Babaii's research on native (American) and non-native speakers (Iran and Pakistan), established the following obligatory moves unfolding in an editorial genre: Headline, Addressing an Issue, Argumentation, and Articulating a Position. They also identified Background Information, Initiation of Argument, and Closure of Argument as optional moves. Le's (2004) study on French editorials (Le Monde newspaper) show how editorial writers present themselves as competent and responsible conveyers of public opinion. Although the study does not present the generic structure, it invokes Appraisal and shows the negative and positive values editorialists employ. In addition, it underscores the use of evidentials, person markers and relational markers in editorial construction. Bonyadi's (2010) comparative study English and Persian editorials borrowed Bolivar's triad model. In the Introduction, Bonyadi established the Orientation (OR) move, which engaged the reader and Criticism (CR) move, which asserted criticism. The Body segment was realised via the presentation, development and evaluation of sub-topics, while the End segment entailed concluding the topic. A related study by Bonyadi and Samuel (2013) indicates a contrast in the construction of editorial headlines between The New York Times and Tehran Times. Whereas The New York Times preferred punchy headlines and employed such rhetorical devices as metonymy, metaphor, rhetorical questions and parallelism; Tehran Times used full sentences and made use of allusion, neologism, and antithesis. A more recent study by Caffarel-Cayron and Rechniewski (2014) revealed that the generic structure of French editorials (Le Figaro and Liberation) exhibited an attitudinal orientation, background argument, arguments that supported the thesis, and a conclusion that summarises, evaluates the issue, and demands action. Their study highlights a variation between the French and English editorials: while the English editorials position their stance at the end of the genre, the French foreground their position in the attitudinal orientation, which is placed at the start of the genre. These studies do not only demonstrate varied rhetorical strategies across newspapers but they also indicate a shift in editorial writing since Bonyadi's first study of editorial discourse.

Although editorial genre research is fairly increasing, it still falls short of studies emanating from the mainstream non-Anglo-American news media contexts, especially Africa. Secondly, there is limited research that traces the evolutionary nature of editorial writing. Thefore, this article responds to this gap: it explores the generic and rhetorical changes that have characterised the discursive practice of editorial writing in an African media setting. Thus, it shows the contrast between the generic structure of the English and Runyankore-Rukiga editorial and the rhetorical strategies invoked by the latter.

4. Methodology

4.1 Corpus description and gathering

The present study focuses on editorial texts from the indigenous newspapers since the mid-1950s up to 2010. This period is selected because newspaper publication in Runyankore-Rukiga with its attendant writing of editorial texts appeared in Runyankore-Rukiga news discourse in 1955. However, since 2010 there has not been any editorial texts appearing in Runyankore-Rukiga newspapers. This selection of editorial texts is distributed across four different epochs: the colonial period (pre-independence, 1955-1961); the post-independence period (1962-1970); the 1971-1984 period, which is largely characterised by internal conflict during the Amin regime; and the 'contemporary' period (1985-2010) within which airwaves were liberalised. These different periods inform the nature of editorial content and arguably the rhetorical strategies carried by the existing newspaper. Therefore, the study comprises of a continual diachronic corpus of 70 editorial texts spanning a period of more than 50 years, which allow an exploration of the editorial writing in an evolutionary manner. The texts are gathered from Agari Ankole (Ankore News), Ageteraine1(Unity) Buseesire (The Dawn), Orumuri (The Torch) and Entasi (The Spy), which were started in 1955, 1959, 1960, 1989 and 1998, respectively. Besides Busessire, which was a private newspaper, Agari Ankole and Agetereine were established by the Catholic Church as monthly or bi-monthly publications. Orumuri started as a weekly government paper aiming to educate the public on government issues, while Entatsi is a weekly private newspaper and aims to provide alternative opinions to the already existing Orumuri. These indigenous newspapers have targeted readers of the same locality, south-western Uganda. Their news reporting scope has been mainly limited to the news value of 'cultural proximity', that is, they pay attention to the more familiar and culturally similar news events and glosses over those from culturally distant areas (Galtung and Ruge 1965). Although the contemporary newspapers (Orumuri and Entatsi) are regarded as tabloids, they carry significant news reports for their target readership, including issues on politics, economics, education, farming, and health, as well as social issues. This implies that not only do the newspapers target the low-end market, but they also target the readership category whose interest goes beyond tabloid content.

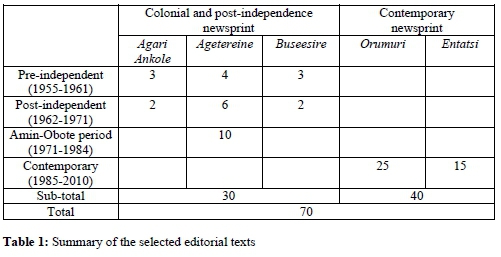

In order to obtain a representative sample, a purposive sampling technique was invoked. The selection of editorial texts is based on the publication periods highlighted above. Thirty news texts were selected from the colonial and post-independence periods (1955-1984), which entails editorials from the discontinued Runyankore-Rukiga newspapers. More texts (40) are selected from the contemporary period because of the regular weekly publication of the newspaper.

However, more examples are derived from Ageteraine because it was more regular and dominated printing news for a long time. The appearance of the indigenous newspapers during the pre-independent period was intermittent, often appearing on a monthly or bi-monthly basis, while the post-independence period was equally characterised by intermittent publications (see Table 1 below).

4.2 Analytical approach

The article invokes genre discourse analytical approach to categorise texts based on their similarities and differences and adequately analyse their textual structure. Genre analysis is about the situated analysis of linguistic behaviour in an institutionalised academic or professional context. Tardy and Swales (2008: 565) posit that texts are defined by "culturally preferred shapes", which define internal and external organisation. Through accumulated experience and constant use by the genre users to achieve a communicative purpose, a genre attains a structure which defines it. Genres possess recognisable textual and structural features that identify them and define their distinctiveness. The exploration of Runyankore-Rukiga editorial texts across different epochs to establish the structural and textual features is made in this vein. Therefore, genre analysis is invoked to establish the internal structure of a Runyankore-Rukiga editorial genre and demonstrate the rhetorical strategies it adopts to position itself ideologically but also to achieve its communicative purpose of persuading its putative readers.

Furthermore, the article relies on Swales (1990) and Bhatia's (1993, 2004) multidimensional analytical approaches, which entails a close reading of the texts, examining the intentions and motives of the text writer as well as the institutional and cultural context within which the genre is constructed. Although genre analysis enables the identification of the move structure of texts to establish the generic potential structure of a genre by analysing the lexico-grammar, a critical genre analysis is preferred to explain the socio-cultural and institutional settings that underpin the rhetorical strategies used in constructing a genre. In this regard, we attend to the notion of the socio-cultural and cognitive factors, which extends the genre analysis to understanding why genres appear the way they do (Bhatia 1993, 2004). Cafferel-Cayron and Reichniewski (2014: 27) posited that

editorials, as sub-type of the argumentative genre, are best analysed in terms of generic 'stages' that each have clearly defined and differing roles to play in the overall text, contributing to an internal ordering that is essential to the effectiveness of their communicative function and their persuasive force.

The genre analysis of the editorial texts takes into account the socio-cultural context within which the editorial genre is constructed. Therefore, not only is a methodical and critical reading of the editorial texts conducted, additional information and expert knowledge from the professional writers and editors of the examined newspapers was sought (see Bhatia 1993, 2004 who recommends interaction with expert members). The analysis also identifies other texts (religious, political) that inform the genre construction. Interaction and communication with the writers and editors revealed inside information regarding the unwritten editorial policies, which shape the discursive practice of editorial texts. Because the article traces the evolution of editorial genre, below, the historical context of indigenous newspaper publishing in Uganda is explored.

5. Historical overview of indigenous newspaper publishing in Uganda

The national press in Uganda traces its development to the early 1920s. In particular, there were several Luganda newspapers, some of which were started by Catholic missionaries like Munno and others like Sekanyolya, Mengo Notes and Uganda Empya. The religious institutions, namely the Anglican and Catholic missionaries, were instrumental in establishing print media. The news content focused on church issues; they (largely in the form of newsletters) were also used as a channel of communicating missionary work with those abroad (Isoba 1980). Although the newspaper industry in Uganda had been in existence for a long time, it experienced rapid expansion only in the 1950s and 1960s (Isoba 1980). While there was a decline in the number of newspapers (in both local languages and English) during Amin and Obote's regimes, the media industry, especially the electronic media proliferated due to the liberalisation of airwaves and because of relative press freedom in the mid-1980s and at the beginning of the 1990s. Today, there is considerable growth of newspapers across the country both in English and local languages.

The first Runyankore-Rukiga newspaper, Agari Ankole, was first published in 1955. It started as a four-page monthly paper. Although the subsequent Runyankore-Rukiga newspapers ranged from 6 to 12 pages, they indeed carried significant issues at the time. Agari Ankole largely published news on religion, especially the Catholic Church (episcopal visits), the King and Kingdom of Ankore as well as British news, with regards to news on the monarchy.

Ageteraine appeared on stage in January 1959 as a bi-monthly publication; later on, it became a weekly issue covering south-western Uganda. It was pioneered by the prelate of Mbarara Catholic Diocese and Bishop Jean-Marie Ogez to communicate church news, including propagation of the Catholic faith. Ageteraine largely published news from the south-western region, but focused on religious news within Mbarara diocese. It also carried news on education, civic duties such as the impending vote of 1960 about self-rule (independence), how people should conduct themselves in public, legends, value of taxes, and bride price. In fact, several editorials and news reports at that time focused on the impending vote, which was about self-rule. Although the colonial government had already granted independence, there were unresolved issues regarding how Africans [Ugandans] would tackle the issue of self-rule. Since the covert politics of the day were mainly about the religious grouping from which the post-independent leaders would come, the Catholic-based newspaper was forthcoming on this subject. It should be noted that most of the indigenous newspapers were established to stimulate political awareness, and respond to colonial rule as well as social development (Scotton 1973).

In January 1960, Buseesire, a private newspaper, was established and claimed to objectively engage with existing issues relating to monarchical reign in Ankore. It was largely pre-occupied with independence matters, focusing on development and civic education since the country was preparing for independence. For example, in its maiden issue, the newspaper's 'editorial' stated that it aimed to engage social justice including fighting for the workers' rights, and sensitise the readers on misuse of the Kingdom funds. Both Agari Ankole and Buseesire had a short span and did not live to witness independence developments, which they were advocating for.

Orumuri started in October 1989 as a government newspaper to propagate government policies and development programmes. It operated alongside Ageteraine, which closed in the mid-1990s (after 39 years). According to one of the former editors, Ageteraine could not cope with the more current and stylistic Orumuri. The appearance of Orumuri marked a shift in Runyankore-Rukiga newspaper discourse because it employed trained and professional news reporters and editors who did not only have a good grasp of the linguistic competences but also the journalistic acumen of news report writing. Arguably, the newspaper exhibited a news text similar to mainstream English daylies, namely The New Vison and The Monitor. The maiden issues ranged between 12 and 16 pages and carried both local and international news content, concerning corruption, AIDS/HIV, political and electoral violence, land conflict, and wars. Currently, Orumuri has evolved into a tabloid that circulates mainly in the south-western areas of Uganda, but is also read in other parts of the country, especially Kampala.

Finally, Entatsi was established in 1998 as a weekly private newspaper in south-western Uganda. It claimed that there was lack of a local language newspapers that would provide alternative opinions apart from what the government newspaper, Orumuri, was publishing. The newspaper became a tabloid in 2005 focusing on content that blends culture, entertainment, and sports. It has largely published sex, scandal and shock stories. This transformation affected the content that was previously published in the outlet. In fact, it has endeared its readers by publishing pictures of nude women, adulterous spouses and domestic and sexual violence-related stories.

6. The discursive practice of editorial writing in Runyankore-Rukiga

The editorial text did not appear as a significant genre in Runyankore-Rukiga newsprint until the appearance of Orumuri. It is even absent in some of the early issues of Agari Ankole, Buseesire and Ageteraine. The text appeared on the front pages of the maiden issues of Ageteraine as a lead article and was explicitly marked 'EDITORIAL', possibly underscoring its significance to the newspaper and its readers at the time. Nonetheless, the genre did not entail argumentative moves. It essentially comprised ecclesiastical texts whose rhetorical moves entailed an exhortation of pious and civic ways of living, perhaps reflecting the ideology and standpoint of the newspaper proprietorship, the Catholic religious establishment.

Unlike the English editorial, which is traditionally known to occupy a fixed and distinctive position in a newspaper, usually in the centre pages and appearing alongside a letters page, the Runyankore-Rukiga editorial's position has been shifted over time. While the Buseesire and Agari Ankole editorials were recounted on page 2 and 3, respectively, the Ageteraine editorial appeared on the front page along with the main news stories. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the Agetereine editorial's positioning shifted to page 2. A cursory comparative check of the English newspaper editorial at the time, Uganda Argus, reveals a similar positioning, an indication that the shift was in consonance with the discursive practice of mainstream English newspapers.

Furthermore, the nature of the news content and situations at a particular epoch influence the subject matter of the editorial. For example, the early newspapers (Ageteraine, Agari Ankole and Buseesire), which were established during the pre-independence years, constitute an editorial content that engages independence-related discourse, namely sensitising the readers to the development that would accrue from self-rule, new policies or laws and the national vote on Ugandan independence. The editorial rhetoric also focussed on the comparative parameters between the existing colonial masters, who were perceived as prototypes of good governance and the in-coming native politicians. The post-independence editorial focus entailed the independence of other African nations, debates on the formation of parties, voter education, the Ankore monarchy, as well as other issues like graduate tax, the socio-cultural issue of bride price and conserving the environment. For example, in the editorial extract below, Catholics are urged to resist possible disenfranchisers.

(1) Okuteera oburuuru ni rwo rugyero rw'okubanza rw'okukozesa engoga zawe. Mpaho, omukristu weena orikubaasa kuteera oburuuru aragirwa kubuteera. Manya n'ekiragiro ky 'obuhangwa. Na mbwenu ekiragiro ekyo nikyenza abateezi b'oburuuru okushoborokyerwa omurimo gwabo gw'okubutera ku guri ogw'okuragirwa-kukorwa; kandi abateezi b'oburuuru baragirwa okwerwanaho bonka haaba hareebekire owakukunzire okububazibira. (Agetereine, 7 March 1959: 1)

"Voting is the first step towards using your strengths. Therefore, every Catholic who is eligible to vote must vote. Because this is a natural [human] right. In fact, this right requires voter education; and voters must defend themselves in case one wishes to disenfranchise them."

The editorial text unfolding during the unsettled period of Amin's regime (exclusively appearing in Ageteraine) focuses on community development, education and other social issues including women's rights. Understandably, the prowling agents of Idi Amin threatened the newspaper enterprise; therefore, the editorialist resisted articulating critical debates on politics, democracy, extra-judicial killings, and economic malaise that would have hitherto influenced the editorial content of the day.

The contemporary period (appearing in Orumuri and Entatsi) is characterised by the new government whose governance style appears to deviate from past dictatorial governments. Therefore, the editorial texts habitually comprise persuasive arguments that were apt to favour ruling government, including express texts that de-campaign political parties that were 'a source of problems' in the country. For example, the editorial headline in (2) below referred to a legendary opposition leader, Paul Ssemogerere; it insinuates that he is a rag doll that people should not be scared of.

(2) Mutatina waringa (Orumuri, January 15-21, 1996) "Don't fear a scarecrow."

Of course, this reflects the newspaper's ideological positioning, that is, in support of and prioritising government programmes (see Reynolds 2000). Whereas Uganda experienced war in eastern and northern parts for more than two decades (1987-2005), there are no significant texts in both Orumuri and Entatsi editorialising these war events. Orumuri exhibits one extended editorial text justifying the fighting and killing of LRA rebels in northern Uganda. However, other editorials possess forceful argumentation on corruption, elections and campaigns, vote rigging, and voter bribery (see the editorial headline in example 3 below). This time, the country is experiencing voting after a long spell of absence of polling (since 1980).

(3) Okwiba oburuuru gubaire omuze (Orumuri, August 12-18, 1996: 4) "Vote stealing has become a bad habit."

A noticeable shift in editorial writing and content occurs when the newspapers metamorphose into complete tabloids, focusing on lewd content such as sex, scandal and shock news elements; a trend that affected editorial output. In addition, whereas there has been media freedom in the country, a continued crackdown on media houses and journalists has been evident. As a result, there has been self-censorship and reduced focus on editorialising issues (see also Brisset-Foucault 2014). In fact, a close reading of the contemporary Runyankore-Rukiga newspapers indicates a shrink in the editorial text at the beginning of 2000; the text ranges from one or two agraphs to a couple of segments in comparison to comprehensive segments obtained in the late 1990s. Between 2006 and 2010, both newspapers did not carry editorials in some of their issues. Occasional editorials would appear in either of the newspapers until they eventually 'discontinued' the column altogether. In fact, Entatsi discontinued editorial texts in its publication in 2006, while Orumuri's editorial genre fell in 2011. To-date, there are neither editorial texts nor commentary columns appearing in Orumuri and Entatsi. To sum up, commercial interests alongside fear of government crackdown on media outlets have driven local language newspaper to desist from editorialising issues. In fact, one news editor categorically illustrated that the newspaper cannot afford to lose its business because of articulating its ideological positioning, which is construed as 'criticising government'.

7. The generic structure of a Runyankore-Rukiga editorial

The 'contemporary' Runyankore-Rukiga editorial architectural structure is derived from a genre analysis of Orumuri and Entatsi news texts. The article did not attempt to generate an archetypal generic structure of editorial writing that characterises earlier newspapers because the genre appeared to have been in constant flux. Each newspaper maintained a unique generic structure of its editorial text because the news writers and reporters working in the indigenous newspaper industry had neither formal training nor practical experience in publishing in Runyankore-Rukiga; there were no available training institutions in Uganda (Isoba 1980). It appeared that either the construction of editorial texts was an imitation of the existing editorial genres in the English newspapers or a creation of the media outlet based on what it deemed appropriate rather than the conventions of journalistic practice. For example, Ageteraine exhibits a structure that resembles a church sermon often interspersed with segments of religious or civic exhortations. Observable instances of cross-titles intermittently occur in the post-independence editorial texts.

The Runyankore-Rukiga editorial exhibits the following rhetorical moves: H+(SI)+BIn+(A)+(PGA)+An+C. This move structure is analogous to the English editorial published in the English daylies in Uganda. The obligatory moves include Headline (H), Background Information (BI), Argument (A) and Closure (C) across the analysed Runyankore-Rukiga editorial texts. The rhetorical move of Stimulating Issue (SI) conveys the attitudinal positioning of the editorialist acting to lure the reader to align with this position. The Headline and Closure elements are fixed while the Stimulating Issue, Background Information, and Presenting Grounds for Argument (PGA) elements are iterative. The analysis also indicates that the Background Information occasionally occurs within the Argument. However, the Argument always precedes the Stimulating Issue and Presenting Grounds for Argument. Therefore, the rhetorical structure is similar to Ansary and Babaii's (2005) as well as that exhibited by English editorial structures across Ugandan English newspapers (Mugumya 2013). The similarity exhibited by the Runyankore-Rukiga editorial could be attributed to the discursive practice of indigenous news reporting which has been adapted from the mainstream English newspapers (both in structure and presentation). In addition, unlike the previous newspapers, Orumuri and Entatsi had writers and reporters who had been trained in journalism or related studies and experienced working with English-medium newspapers; therefore, they tailored their Runyankore-Rukiga news discourse of the English news and commentary prototypes.

However, the study observed a considerable number of Runyankore-Rukiga editorial texts that occasionally entail recounts and evaluations that do not necessarily engage in actual argumentation. In fact, the existing structure (rhetorical moves) does not articulate arguments and justify or refute them to achieve the communicative goal of editorial writing.The communicative goal of the text marked or identified (because of its position) as an editorial is merely informative. The texts exhibit subtle recounts and unexpected positive evaluations of issues rather than judicious arguments or counter-arguments.

8. Rhetorical strategies invoked in Runyankore-Rukiga editorial

The rhetorical strategies we explore relate to the devices that enhance argumentation because editorials inherently and constantly involve persuasion and arguments in favour of the issues of the day.

Analysis of the editorial texts during pre-independence and post-independence indicate a notable use of segments interspersed with religious exhortations or biblical propositions. The editorial often closes with advice based on civic instruction or biblical teaching. Although this is prevalent in the maiden issues of Agateraine and Buseesire, even when the editorials progress to focus their debates on development, education, farming and politics, the arguments, particularly in Ageteraine editorials, are often presented or couched in religious teaching. The editorialist cites biblical verses from the New Testament, especially Jesus' teachings, to illustrate an argument. Evidently, this invocation is traced to the newspaper's proprietorship, the Catholic diocese of Mbarara, and thus its ideology of news reporting based on the church/religious teaching.

(4) Omuhanda gwaitu n'omuhanda gw'obwinganisa n'okukundana, nigwo muhanda gwa Ruhanga waitu owatugizire ati: Ninye Muhanda, onkuratira tagyenda mu mwirima (Ageteraine, 18 April 1959: 1) "Our way is the way of justice and love; it is the way of God who said, I am the way, whoever follows me does not walk in darkness."

Besides referring to religious teachings and biblical verses, several editorials exemplify Catholic doctrinal attributions, including Papal and Episcopal Encyclicals or Vatican documents to support their arguments (see example 5, which refers to an Encyclical by Pope Pius XII)2. The editorialist invokes the Pontiffs pronouncement to justify the argument, demonstrate the positive value in politics and calling on Catholics to vote.

(5) Obushoborozi bw'okwetwara bwine abataka. Ekyo kigambo ti kihakanisibwa. Abapapa n'Abepiskopi bakakiranga ira. Papa Pio XII akehanangiriza Abafrika, n'abamanyisa ebirikubaasa kubaretera omurabanamu n'okubanaga omu bwiru, muno muno okukunda ensi y'enzaarwa omu muringo oguhinguraine kandi ogutashoborokire (Ageteraine, 7 March 1959: 1) "The power of self-governance lies with the people. This statement cannot be disputed. The popes and bishops pronounced it long time ago. Pope Pius XII exhorted Africans and told them about things that might cause them trouble and enslave them, especially excessive and unexplainable love for the native country…"

Deferring to an authority, the head of the Catholic Church, is intended to lend credence to the arguments being proposed. Given the putative reader's (Catholic) background, knowledge and belief in the absolute power of the Pope (infallibility of the pope), the editorialist would expect reader compliance with the argument. Such references were very telling because of the role that the church was playing in people's lives (education, health) and the importance that people attached to it. Therefore, invoking papal pronouncement would rally people to believe in them since they believed in the infallibility of the Pope.

In the 1970s, the editorial structure and the grounds for the arguments unfold in textual moves lending exclusively to religious teachings based on biblical verses. In some instances, the editorial is an entire sermon of some sort (see Ekitiinwa ky 'abakazi [The pride of women] in Ageteraine, 19 August 1972: 2). Each move is bolstered with a biblical teaching as evidence to support the argument(s) being advanced. For example, while commenting on the issue of treason, the editorialist advocates clemency and sympathy (6). To support the argument, the presidential pardon meted out by Amin for a British national is cited, which is further reinforced by a biblical verse from Ezekiel 18:23-28 in the Closure move.

(6) Kuri noogira ngu Ruhanga akuratira eburingaaniza bwonka akatuhenera buri kishobyo kyaitu ni oha omuri itwe owakugumireho? Kwonka Ruhanga atugumisiriza, atugirira embabazi, twaba nitwikiriza kwegarukamu atusaasira. Ruhanga naagira ati "Nikushemererwa ki okundugira omu kufa i.e. okuhenwa kw'omubi, kw'omusiisi? Eki nyenda ti okuhinduka kwe akeegarukamu akatunga amagara" (Ezekiel 18:23-28) (Ageeteereine, 19 July 1975: 2) "If God was just, He would punish us for every sin. Who among us would remain? How, God is tolerant, merciful if we accept to repent, He pardons us. God says, do I take any pleasure in the death of the wicked? Rather, am I not pleased when they turn from their ways and live?"

"Nikushemererwa ki okundugira omu kufa i.e. okuhenwa kw'omubi, kw'omusiisi? Eki nyenda ti okuhinduka kwe akeegarukamu akatunga amagara" (Ezekiel 18:23-28) (Ageeteereine, 19 July 1975: 2)

"If God was just, He would punish us for every sin. Who among us would remain? How, God is tolerant, merciful if we accept to repent, He pardons us. God says, do I take any pleasure in the death of the wicked? Rather, am I not pleased when they turn from their ways and live?"

Such rhetorical 'tactics' appear to have been invoked to eschew direct arguments and confrontations because of the dictatorial regime of Idi Amin at the time. The editorialist exercised caution to circumvent retribution from Amin's government, which controlled the media (see Isoba 1980).

The analysed diachronic corpus of Runyankore-Rukiga editorials (mid-1950s - 2000s) exhibits consistent and occasional use of anecdotes, similes and proverbs in the Headline (see 7.a-b below) or Background Information phases as premises subsequent arguments, but also to bring humour to the text. Moreover, the text segments, particularly headlines are constructed using spoken/conversational language to associate with the reader. The strategy is inherent in interaction at an informal level. Thus, the editorial writer invokes familiar language that comprises congratulatory phrases, jocular sayings, providing advice, commiserating, etc. to identify with and endear its putative readers. Vestergaard (2000) and Reynolds (2000) have posited that such narrative modes are often invoked to bolster the arguments or provide background information before launching into arguments.

Proverbs have not only been confined to the editorial genre, they have also been found in hard news reports (Mugumya 2015). Proverbs can be traced to the early days of Runyankore-Rukiga editorial writing across the three newspapers, Agari Ankole, Buseesire and Ageteraine. Proverbs are invoked to indirectly evaluate, ridicule, caution or even offer advice as the following proverbial expressions (examples 7.a-b) which appeared as headlines demonstrate.

(7) a. Tingatsiga tatsiga entomi … (Ageteraine, 22 February 1959). "He who vows to drink whatever brew is available does not avoid blows." b. Oku omutwe guri, nikwo enshunju itegwa (Ageteraine, 22 August 1959) "The shape of the head determines the style of the haircut." (This implies that one deals with a challenge/situation depending on its nature.)

Within the Argument moves, the writer often invokes the proverb to reinforce their arguments. For example, while presenting an argument on the significance of unity, an editorialist cites the following proverbs in succession, Tintwarwa afa naazenga, [Whoever refuses to be guided ends up wandering] and Eraafe tehurira nzamba [An animal that is bound to die does not heed a trumpet] (Ageeteereine, 31 August 1962: 2). The proverbs invoked often indicate the socio-cultural context within which this genre unfolds.

Another common rhetorical feature across the pre-colonial editorial consisted of the use of the expressions, 'obwiru', servitude and 'omwiru', slave. Reference to someone as an omwiru connotes low class, servant. The expression even appears in utterances that emanate from religious leaders (8).

(8) Twena tweheyo okwerwanirira ebirungyi ebiricwa obwiru bw'eihanga ryaitu, obw'omunda n'obw'aheeru (Ageteraine, 7 March 1959) "All of us should try to fight for the good things that will get rid of enslavement of our country, from within and from outside."

At the time, it was en vogue because the Ankore monarchy was still in place. The kingdom comprised two divisions, the agriculturists (Abairu) and pastoralists (Abahima). The royalty was exclusively confined to the cattle keepers from whom the Ankore king hailed. There is recorded evidence of how the royalty, particularly the King, subjected the non-cattle keepers to chores (domestic) that were humiliating. For example, they served in the courtyard of the king and performed menial, often times humiliating chores for the King. Thenceforth, the term, 'omwiru [abairu, pl; obwiru) ensued. While the expression still exists, largely in spoken language (often used to denigrate Abairu by the Abahima), it is rarely found in written discourse, especially newspaper reporting because of the sensitive nature of the subject. Needless to say, its use in recent times would stimulate anxiety, hatred and divisionism. To-date, this expression would not appear in newspaper parlance because of the tensions and uproar it could evoke among readers.

Finally, another common rhetorical device encountered was the ridiculing and abusing of political opposition leaders, usually appearing in the headlines, particularly within Orumuri editorials, which explicitly denigrated political opposition leaders. For example, the following headlines (9.a-b) comprise labels that expressly vilify opposition party leaders.

(9) a. Enkunguzi zaatandika (Orumuri, June 19-25, 1995: 4) "Witches have started." b. Emishega mugite aha mushana (Orumuri, April 18-24, 1994: 4) "Expose wolves."

Undoubtedly, the editorialist invokes this rhetorical strategy of underscoring negative labels of the adversary in the Headline or Background Information to prepare the reader's disposition to accept reasons presented in the subsequent phases of the Argument. Because Uganda had a tattered political history characterised by killings, divisionism, and discrimination during the regime of Amin and Obote, any subsequent opposition to the Museveni's government to take power was associated with past regimes. This rhetoric is intended to warn readers about the danger that the opposition political parties pose. The intention is to scare the readers (population) of the likely return to the bad past, but also covertly de-campaign those who would pose a challenge to the NRM government in terms of campaigning for voters. Surprisingly, negative conduct is extolled even where it would have naturally attracted social sanction. For example, while editorialising events of war in Uganda, the editorialist extols government forces for killing rebels. Although such a rhetoric appears to depart from the norm, the editorialist invokes it to realise a private intention (Bhatia 2008), that is, invoking a stimulating issue to extol government conduct. Both Orumuri and Entatsïs editorial texts occasionally embodied segments of similar arguments to support government actions and contestants during electoral campaigns. While this argumentation would appear acceptable in certain contexts, it would be regarded as eccentric in others that regard any deprivation of human life as unacceptable. Extolling the country's defence forces in killing citizens is equally obnoxious.

9. Conclusion

This article has examined the evolution of an editorial genre in Runyankore-Rukiga press. The genre had been constantly changing and finally stabilised during the 1990s and 2000s. The change in genre is attributed to the nature of the people who construct these genres (Devitt 2004). For example, in the 1960s and 1970s, writers who were mainly religious leaders (missionaries) carried out the Runyankore-Rukiga editorial construction. This influenced the nature of editorial genres comprising largely of arguments rooted in religious and biblical propositions. The 1980s and 1990s editorial texts were characterised by professional news reporters who were astute in Runyankore-Rukiga orthography; therefore, the editorial genre takes on a different character and structure. From the 2000s, the Runyankore-Rukiga print media was in the hands of young and dynamic writers whose world view was different from their predecessors. Although most of these writers had training in journalism, they lacked in linguistic skills, especially orthography. In addition, the commercialisation of the news industry in Uganda coupled with political influence have affected editorial writing. Consequently, the genre starts to appear infrequently in print towards the end of the 2000s. Eventually, it disappears altogether from Runyankore-Rukiga press. The genre has responded to unique situations overtime, which varied from different political governments (colonial (pre-independent era), post-colonial, Amin and Obote regimes as well as the current Museveni government. It has also been able to adapt to a wave of recurring situations (Devitt 2004), including evangelism, corruption, AIDS, political violence and wars. As Devitt (2004: 92) argues that since genres "reflect their cultural, situational, and generic contexts, and since those contexts change overtime, genres, too must change overtime".

Whereas media houses cannot withstand government pressure, discontinuing an editorial genre renders these news outlets as appendages of government and robs them of their ideological stance. Newspaper editorials are not only about opinion expression on matters that are political in nature. To think and act so would be to have a narrow conception of editorial writing. Like her English counterparts, a Runyankore-Rukiga editorial should encourage and embrace editorial writing on other contemporary issues that are not necessarily political in nature.

The editorial genre is crucial in guiding the putative readers in the right direction but also in shaping public opinion on important issues unfolding in contemporary times. It also has pedagogical implications with regards to constructing and construing argumentative writing. If such a sub-genre of argumentation is absent from Runyankore-Rukiga newsprint, it renders a newspaper undervalued but also deprives it the opportunity to assert its position and ideology in society.

This study has explored the discursive practice of editorial writing in Runyankore-Rukiga, explicating the generic structure and rhetorical devices invoked to construct an editorial text. Research into the lexico-grammatical properties that underpin editorial writing would further establish the nature of editorial writing in Runyankore-Rukiga. In addition, a comparative study of English and Runyankore-Rukiga editorials across different times in history would reveal the impact and extent of English editorial writing on editorial texts of Runyankore-Rukiga and other indigenous languages.

References

Ansary, H. and E. Babaii. 2005. The generic integrity of newspaper editorials: a systematic functional perspective. RELC Journal 36(3): 271-295. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688205060051 [ Links ]

Askehave, I. and J.M. Swales. 2001. Genre identification and communicative purpose: A problem and a possible solution. Applied Linguistics 22(2): 195-212. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/22.2.195 [ Links ]

Ayers, G. 2008. The revolutionary nature of genre: an investigation of the short texts accompanying research articles in the scientific journal. Nature English for Specific Purposes 27: 22-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2007.06.002 [ Links ]

Bawarshi, A.S. and M.J. Reiff. 2010. Genre in Linguistic Traditions: Systemic Functional and Corpus Linguistics. In A.S. Bawarshi and M.J. Reiff (eds.) Genre: An Introduction to History, Theory, Research, and Pedagogy. Fort Collins: WAC Clearinghouse. https://doi.org/10.7330/9781607324430 [ Links ]

Bednarek, M. 2006. Evaluation in Media Discourse: Analysis of a Newspaper Corpus. London: Continuum. [ Links ]

Berkenkotter, C. and T.N. Huckin. 1995. Genre Knowledge in Disciplinary Communication: Cognition/Culture/Power. Hillsdale: Laurence Erlbaum Associate Publishers. [ Links ]

Bhatia, K.V. 1993. Analysing Genres: Language Use in Professional Settings. London: Longman. [ Links ]

Bhatia, K.V. 2004. Worlds of Written Discourse. London: Continuum. [ Links ]

Bonyadi, A. 2010. The rhetorical properties of the schematic structures of newspaper editorials: A comparative study of English and Persian editorials. Discourse & Communication 4(4): 323342. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481310381579 [ Links ]

Bonyadi, A. and M. Samuel. 2013. Headlines in Newspaper Editorials: A Contrastive Study. SAGE Open 3(2): 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244013494863 [ Links ]

Brisset-Foucault, F. 2014. Domestication, coercion and resistance: the media in Central Uganda during the 2011 elections. In S. Perrot et al. (eds.) Elections in a Hybrid Regime: Revisiting the 2011 Uganda Polls. Kampala: Fountain Publishers. pp. 208-247. [ Links ]

Caffarel-Cayron, A. and E. Rechniewski. 2014. Exploring the generic structure of French editorials from the perspective of systemic functional linguistics. Journal of World Languages 1(1): 18-37. https://doi.org/10.1080/21698252.2014.893672 [ Links ]

Devitt, A.J. 2004. Writing Genres. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. [ Links ]

Eggins, S. and J.R. Martin. 1997. Genres and registers of discourse. In T.A. van Dijk (ed.) Discourse as Structure and Process. London: Sage. pp. 230-256. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446221884.n9 [ Links ]

Fairclough, N. 2003. Analysing Discourse: Textual Analysis for Social Research. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Feez, S., R. Iedema and P.R.R. White. 2008. Media Literacy. Sydney: Disadvantaged Schools Program, NSW Adult Migrant Education Service. [ Links ]

Galtung, J. and M.H. Ruge. 1965. The structure of foreign news. Journal of Peace Research 2 (1): 64-91. [ Links ]

Gillaerts, P. and P. Shaw. 2006. Introduction: genre and norm. In P. Gillaerts and P. Shaw (eds.) The Map and the Landscape: Norms and Practices in Genre. Bern: Peter Lang, International Academic Publishers. pp. 7-20. [ Links ]

Halliday, M.A.K. 1985. Context of situation. In. M.A.K. Halliday and R. Hasan (eds.) Language, Context, and Text: Aspects of Language in a Socio-semiotic Perspective. Victoria: Deakin University. pp. 3-14. [ Links ]

Hyland, K. 2002. Genre: language, context, and literacy. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 22: 113-135. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0267190502000065 [ Links ]

Hyon, S. 1996. Genre in three traditions: implications for ESL. TESOL Quarterly 30(4): 693722. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587930 [ Links ]

Isoba, J.C.G. 1980. The rise and Fall of Uganda's newspaper industry, 1900-1976. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 57(2): 224-233. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769908005700204 [ Links ]

Kress, G. 1993. Genre as social process. In B. Cope and M. Kalantzis (eds.) The Powers of Literacy: A Genre Approach to Teaching Writing. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh. pp. 2237. [ Links ]

Lihua, L. 2009. Discourse construction of social power: interpersonal rhetoric in editorials of the China Daily. Discourse Studies 11(1): 59-78. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445608098498 [ Links ]

Martin, J.R. 2009. Genre and language learning: a social semiotic perspective. Linguistics and Education 20:10-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/Uinged.2009.01.003 [ Links ]

Martin, J.R. and D. Rose. 2003. Working with Discourse: Meaning Beyond the Clause. London: Continuum. [ Links ]

Miller, C.R. 1994. Genre as social action. In A. Freedman and P. Medway (eds.) Genre and the New Rhetoric. London: Taylor & Francis Ltd. pp. 23-42. [ Links ]

Mugumya, L. 2013. The Discourse of Conflict: An Appraisal Analysis of Newspaper Genres in English and Runyankore-Rukiga in Uganda (2001-2010). PhD Dissertation, Stellenbosch University. [ Links ]

Myers, G. 2000. Powerpoint presentations: technology, lectures and changing genres. In A. Trosborg (ed.) Analysing Professional Genres. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. pp. 177-191. https://doi.org/10.1075/pbns.74.16mye [ Links ]

Norlyk, B. 2006. Clashing norms: job ads or job narratives? In P. Gillaerts and P. Shaw (eds.) The Map and the Landscape: Norms and Practices in Genre. Bern: Peter Lang. pp. 43-61. [ Links ]

Paltridge, B. 2002. Genre, text type, and the English for Academic Purposes (EAP) classroom. In A.M. Johns (ed.) Genre in the Classroom: Multiple Perspectives. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 73-90. [ Links ]

Ramanathan, V. and R.B. Kaplan. 2000. Genres, authors, discourse communities: theory and application for (L1 and) L2 writing instructors. Journal of Second Language Writing 9(2): 171- 191. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1060-3743(00)00021-7 [ Links ]

Reynolds, M. 2000. The blending of narrative and argument in the generic texture of newspaper editorials. International Journal of Applied Linguistics 10(1): 25-40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-4192.2000.tb00138.x [ Links ]

Scotton, J.F. 1973. The First African Press in East Africa: Protest and Nationalism in Uganda in the 1920s. The International Journal of African Historical Studies 6(2): pp. 211-228. https://doi.org/10.2307/216775 [ Links ]

Swales, J.M. 1990. Genres Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Tardy, M.C. and J.M. Swales. 2008. Form, text organisation, genre, coherence, and cohesion. In C. Bazerman (ed.) Handbook on Research Writing: History, Society, School, Individual, Text. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum. pp. 565-581. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410616470 [ Links ]

Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS). 2016. The National Population andHousing Census 2014 - Main Report. Kampala: Uganda. [ Links ]

Vestergaard, T. 2000. That's not news: persuasive and expository genres in the press. In A. Trosborg (ed.) Analysing Professional Genres. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. pp. 97-119. https://doi.org/10.1075/pbns.74.10ves [ Links ]

Wang, W. 2008. Intertextual aspects of Chinese newspaper commentaries on the events of 9/11. Discourse Studies 10 (3): 361-381. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445608089916 [ Links ]

White, P.R.R. 1997. Death, disruption and the moral order: the narrative impulse in mass-media 'hard news' reporting. In F. Christie and J.R. Martin (eds.) Genre and Institutions: Social Processes in the Workplace and School. London: Continuum. pp. 101-133. [ Links ]

White, P.R.R. 2000. Appraisal Outline. Available online: http://www.grammatics.com/appraisal/AppraisalOutline/UnFramed/AppraisalOutline (Accessed 18 March 2017).

1 The name of the newspaper was derived from a Runyankore-Rukiga proverb, Ageteraine nigo gaata eigufa [the teeth that bite together break the bone, 'unity is strength'.

2 This was in reference to an encyclical on Catholic Missions, especially in Africa by Pope Pius XII in 1957. Available online at: http://www.papalencyclicals.net/pius12/p12fidei.htm