Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus (SPiL Plus)

On-line version ISSN 2224-3380

Print version ISSN 1726-541X

SPiL plus (Online) vol.58 Stellenbosch 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.5842/58-0-843

PART II: APPLIED LINGUISTICS

Using African languages at universities in South Africa: The struggle continues

Richard N. Madadzhe

Faculty of Humanities, University of Limpopo, South Africa E-mail: richard.madadzhe@ul.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Both the advent of democracy in 1994 and the adoption of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa in 1996 kindled hope that ultimately official African languages, in addition to English and Afrikaans, would soon be utilised as languages of teaching and learning throughout the education sector of South Africa. However, in spite of government efforts and significant measures assumed by both private and public institutions to promote the use of African languages, this article reveals that the use of African languages in higher education still leaves much to be desired. This article presents a variety of causes for this state of affairs such as globalisation, economic factors, negative attitudes towards African languages and a lack of will or confidence by both students and university officials to take the plunge in using African languages in teaching and learning. Furthermore, developments in the country around issues such as #RhodesMustFall, decolonisation and Africanisation of higher education curricula, as well as the imminent introduction of the Revised Language Policy for Higher Education in 2019 make it imperative to make a reappraisal of the possibility of utilising African languages at universities in South Africa. Finally, the article argues that it is high time to walk the talk because debating the relevance of African languages in teaching and learning at universities in South Africa cannot take place indefinitely. Indeed, it has to come to a stop somewhere considering that for the past 50 years, scholars have been debating the aptness of African languages in education in general. The present analysis hinges on two theoretical frameworks, that is, Sociocultural theory and Afrocentricity.

Key words: African languages; Afrocentricity; decolonisation; higher education; language of teaching and learning.

1. Introduction

The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (1996: 4) bestows official status upon eleven languages, namely Afrikaans, English, isiNdebele, isiXhosa, isiZulu, Sepedi, Sesotho, Setswana, SiSwati, Tshivenda and Xitsonga. The inclusion of African languages as official languages is meant to rectify the historical, linguistic imbalances that apply to various areas of life in South Africa. It is for this reason that the same Constitution (1996: 4) enjoins the state to take "practical and positive measures to elevate the status and advance the use" of all of these languages. Furthermore, the aforementioned Constitution (1996: 15) explicitly states that "everyone has the right to receive education in the official language or languages of their choice in public educational institutions where that education is reasonably practicable." As impressive as this provision is, it is disheartening to observe that the use of African languages as languages of teaching and learning (LoTL) in higher education is still negligible. In fact, English (to a greater extent) and Afrikaans (to a lesser extent) still enjoy more prominence in higher education in South Africa. Therefore, this article would like to establish the causes of such a situation and propose the steps that should be undertaken to fully realise the use of African languages in higher education in South Africa.

2. Current debate on South African language situation

The debate on the use of a specific language as the most appropriate as a language of teaching and learning (LoTL) in South Africa has been raging for many years - in the pre-apartheid (1652-1949), apartheid (1949-1994) and post-apartheid eras (1994-) (Alexander 1989; Madadzhe and Sepota 2006; Olivier 2009; Madiba 2010; Nkwashu, Madadzhe, and Kubayi 2015). During the pre-apartheid period, Dutch and English were used as LoTLs for mainly the white population and "some of the so-called coloured people" (Olivier 2009: 1). The apartheid age saw the emergence of Afrikaans from Dutch in full force, and the strengthening of English as the LoTL. In all this, African languages were hardly promoted for use except in "the first couple of years" (Olivier 2009: 1) at school. In the same vein, the apartheid regime used African languages to promote the homeland system where each homeland was identified by the dominant African language spoken therein. It is therefore not surprising that African languages were wrongly despised by virtue of their association with homelands.

This notwithstanding, it did not nullify the fact that African languages were spoken by the majority of South Africans and they thus deserved to be promoted in order to bring about development and dignity to their speakers. Not to do so would have meant that English and Afrikaans, even though belonging to minorities, would still continue to bulldoze other languages in the linguistic space in South Africa. Thus, the advent of democracy in 1994 was warmly received by the majority of South Africans as it implied, among others, that African languages would occupy their rightful place in the education arena, and that everyone would have the right to choose a language of their choice as their LoTL. Although this optimism was not misplaced, it was however doused to some extent as proponents of African languages were confronted by multifaceted complexities that are often associated with language use in higher education such as the lack of support from both officials and students, and the entrenched dominance of English in all key areas (study materials, technology and funding).

In fact, language use in education, politics, the economy, religion or life in general has been and is still one of the most vexing issues in South Africa and Africa in general. Currently on the continent (Africa), due to largely historical reasons, there is discord between Anglophone and Francophone regions in Cameroon. Although Cameroon is politically a single country, the conflict is made more acute because one region is English-speaking whereas the other is French-speaking. For example, "what began as a simple request for English to be used in the courtrooms and public schools of the country's two Anglophone regions has escalated into a crisis in which dozens of people have died, hundreds have been imprisoned and thousands have escaped across the border to Nigeria" (Maclean 2018: 1). This demonstrates that ignoring language issues can lead to severe conseqeunces.

Here in South Africa, the Afrikaners' struggle in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries where the imposition of English (Anglicization) at the expense of Afrikaans was resisted. Although the Anglo-Boer Wars (1880-1881 and 1899-1902) are largely attributed to the discovery of gold in the Transvaal (South African Republic) and the Republic of the Orange Free State, it cannot be denied that the impact (through the Uitlanders) and imposition of English colonialism on an unwilling Afrikaner populace also acted as a trigger (Pretorius 2011: 1-7). In addition, the Soweto Riots of 1976 which resulted in the deaths of many black students were a direct result of the rejection of Afrikaans by black students who equated the use of Afrikaans to the oppression of the black majority and the extension of apartheid (Welsh 2009: 153-164).

Therefore, language issues cannot be taken for granted; they are in fact a matter of life and death as the Soweto Riots of 1976 attest. This is why with the political demise of apartheid in 1994, the subsequent democratic government did not waste time to declare 11 languages as official (The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa 1996: 4), of which nine were African languages (isiNdebele, isiZulu, isiXhosa, Sepedi, Sesotho, Setswana, siSwati, Tshivenda and Xitsonga). The expectation was that all these languages would practically "enjoy parity of esteem" and usage in all areas of life, especially in education and the economy (The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa 1996: 4). Although there is distinct progress as regards the use of African languages in the public sphere (radio, television and newspapers) in South Africa, the same cannot be said about these languages as far as education is concerned (Olivier 2009).

It is against this backdrop that the present article will attempt to examine whether the use of African languages at universities in South Africa is attainable or not. In order to realise this aim, the article will endeavour to answer the following questions:

(a) What is the current situation regarding the use of African languages at South African universities?

(b) What is the attitude that students, parents and academics have towards African languages?

(c) What are the advantages and disadvantages of using African languages in higher education in South Africa?

(d) Are there solutions to amend the language problem at South African universities?

3. Theoretical framework

The article will use both Vygotsky's Sociocultural theory and Afrocentricity (Asante 1988) as its linchpin. Vygotsky's Sociocultural theory is "based on the concept that human activities take place in cultural contexts, are mediated by language and other symbol systems and can best be understood when investigated in their historical development" (John-Steiner and Mahn 1996: 191). According to Vygotsky, all human endeavours occur in cultural spaces and cannot be comprehended without these spaces. Language, as a sociocultural product, thus becomes a critical component of human learning because it is through language that people can acquire the deepest cognitive development possible. For Vygotsky, thinking, reasoning and problem solving are underpinned by language in a specific context or milieu (Turuk 2008: 244-259). Vygotsky's views are thus apt when one attempts to establish whether adequate learning takes place for Black South African students if they are taught in a language that is foreign to them and their cultural context.

Secondly, in order to properly examine the possibility of implementing African languages as media of teaching and learning at South African universities, it is evident that this question would need to be addressed from an African perspective. Thus, an apt foundational theory in this regard would be Afrocentricity (Asante 1988) since it is a "frame of reference wherein phenomena are viewed from the perspective of the African person" (Asante 1988: 171). The emphasis here is that for long lasting solutions, problems afflicting African countries such as South Africa can best be understood, illuminated and resolved from an African perspective, not Western or Asian as is presently the norm. Dalvit, Murray and Terzolli (2009: 45) support this thesis as they suggest that "knowledge relevant to the African context must be made available in a language the majority of African people understand". This viewpoint is slowly but surely gaining traction in South African universities as evidenced by the introduction of Africanisation projects at institutions such as Universities of KwaZulu-Natal and Stellenbosch; and by a clarion call from student organisations to decolonise South African universities.

4. International and South African pictures

4.1 The international picture

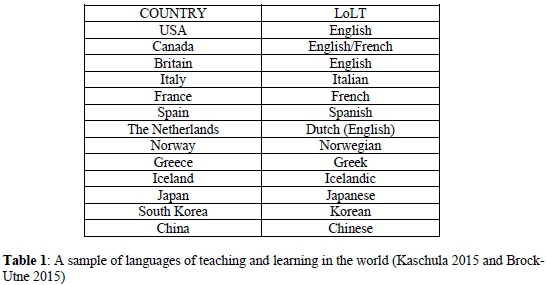

The section that follows presents a table where the international situation is portrayed in terms of LoLT in higher education:

Table 1 demonstrates that all the indicated countries use their first languages (mother tongues) for learning and teaching. Remarkably, all these countries are regarded as economically and socially developed or advanced countries; and moreover, they rate very highly in literacy levels. This is not surprising because there is hardly any student who cannot perform well when taught in his or her first language. While some of these countries such as South Korea were economically at the same level as African countries such as Ghana and Nigeria a few decades ago, today the former countries are known as Asian Tigers because of their thriving economies whereas their latter counterparts are struggling and are part of the 'third-world'. Undoubtedly, the Asian countries are marching ahead of Africa because they use their own first languages for development (economically and politically) (Wolff 2018). For instance, South Korea developed immensely in the past 60 years after adopting Korean as an official language after jettisoning Japanese (a colonial language in this instance). Had African students studied History, Mathematics, Natural Science and Geography in their own mother tongues, the likelihood is that the majority of them would have passed every qualification with flying colours. But they could not because they first had to think in their own African language and then translate it into English. The English that they speak is 'African language - English'; it is not 'proper' English. In this regard, Wolff (2018) posits: "Research has made it explicitly clear: if efficiency of learning and cognitive development is the target, the mother tongue should be the medium of instruction from primary school, through secondary schools and into universities. Other languages, like English, can be introduced as subjects from lower primary level."

Of course this does not mean that one can definitively state that being taught in one's mother tongue is the only prerequisite to good performance at school. As Jansen (2013: 5) asserts, "simply learning in your mother tongue is absolutely no guarantee of improved learning gains in school... the problem is [...] the quality of teaching, the knowledge of the curriculum and the stability of the school that determines educational chances in a black school". The point however is that, learning in one's mother tongue, at whatever level, increases the chances of success in learning as UNESCO Meeting of Experts in 1951 (Bamgbose 2004: 7) had already concluded that "on educational grounds, we recommend that the use of the mother tongue be extended to as late a stage in education as possible. In particular, pupils should begin their schooling through the medium of the mother tongue because they understand it best and because to begin their school life in the mother tongue will make the break between the home and the school as small as possible."

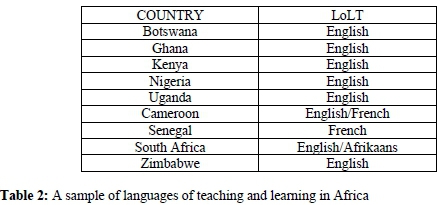

Table 2 above depicts a sorry state of affairs because African countries still use the languages of their former colonial masters for teaching and learning. This is a legacy that African countries should think of discarding. It becomes a big burden for African students because they are expected to compete with speakers of foreign languages (English, French and Portuguese) in the countries of their birth. As Wolff (2018: 3) divulges, "this disadvantages mainly black African students and creates what South African educationist Neville Alexander called a kind of 'neo-apartheid'". It is therefore not surprising that African countries are not achieving their developmental goals as quickly as they would like as the quality of education that students receive plays a major role in the economic development of their countries (Coughlan 2015).

Currently, many higher education students do not have the requisite English competency to succeed in their studies. Among many other causes, this is attributed to the fact that English is not a native language of the majority of South Africans. Thus, students interact with English in class only, not in their homes or local environment where their parents and relatives speak any number of African languages. Secondly, majority of the English teachers are themselves not proficient in English and this inadequacy is then also inherited by their pupils. As a result, what often happens is that African students end up memorizing the content of their subjects with little understanding of the subject matter (Alexander 1999 and Bamgbose 1999). Again, due to the inadequate grasp of English on the part of students, universities are then forced to conduct extra classes and tutorials for such students. As the number of students who do not meet university admission requirements increases annually, universities in South Africa have resorted to designing what is called Extended Curriculum Programmes (ECPs) to cater for such students. All this becomes more expensive for both the universities and the country because this requires more funding to pay salaries of extra staff members and mentors who are involved in conducting extra classes or supplementary instruction for underperforming students. The question then becomes, what needs to be done? It is apparent that South Africa cannot afford to sit back and hope that things will improve without intervention. In order to address this problem properly, it is necessary to examine it by undertaking a situational analysis as far as South Africa is concerned.

4.2 The South African context

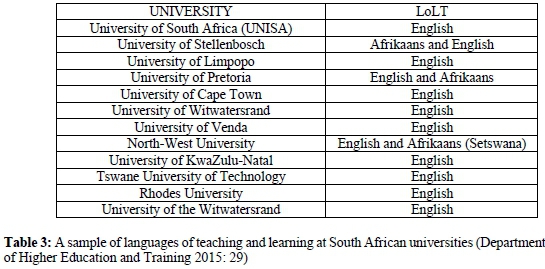

The table below gives a sample of South African universities in terms of the languages that they use for teaching and learning across various programmes (there are 26 public Universities in South Africa).

Currently, as indicated in Table 3 above, all universities in South Africa use English as a language of teaching and learning. However, there are some universities that also accommodate Afrikaans, especially historically Afrikaans universities such as the universities of Pretoria, Stellenbosch and North-West; and offer African languages in a few programmes. In spite of the laudatory endeavours highlighted above, for all intents and purposes English is still dominant as a language of teaching and learning at South African universities. There are many reasons for this state of affairs as described by parents, students and professionals:

(a) English as an international language is essential because it enhances chances for a successful financial and social future (Oxford Royale Academy 2014);

(b) The job market nationally and internationally demands knowledge of English. In this regard, Menakaprija (2016: 22) adds, "English is a global language which is used in international communications, science, information technology, business, seafaring, aviation, entertainment, radio and diplomacy."

(c) It is politically correct to discourage tribalism and ethnicity tensions which may be triggered by the use of African languages (Nkwashu, Madadzhe and Kubayi 2015: 13);

(d) African languages are often associated with backwardness, poverty and inferiority (Nkwashu, Madadzhe and Kubayi 2015: 13);

(e) A large number of parents who are professionals (teachers, nurses, doctors, etc.) do not enroll their children where African languages are taught hence students or pupils end up taking English as a language of teaching and learning;

(f) African people themselves have developed negative attitudes to these languages (Makamu, 2009: 17);

(g) It is (falsely) perceived that African languages are grammatically inadequate for use in teaching subjects such as Natural Sciences and Mathematics (Alexander 1989: 66; Annamalai 2006; Wolff 2018). In other words, there is a belief that African languages are not able "to carry academic discourse effectively and therefore to function as fully-fledged languages of learning and teaching [because their] standard written forms remain in many ways archaic, limited and context-bound, and out of touch with the modern scientific world" (Foley 2001: 2);

(h) There is "suspicion that mother tongue is a ploy of those in power to keep them perpetually marginalized, or the belief that their language is a liability for them to progress, which is ingrained subliminally in their minds by the negative articulation of the value of their language by the dominant speakers" (Annamalai 2006: 344).

To answer the concerns adumbrated above, it is crucial to understand that the attainment of knowledge is not only the prerogative of English; in fact, usage of one's mother tongue promotes it as well (Cf. Foley, 2001). In this regard, Kaschula adds, "what can be articulated, studied and negotiated in one tongue can be done in any other language. Now we need the political will to teach and boost different languages". One is heartened to learn that as of next year (2019), if the Revised Language Policy for Higher Education is enacted, it would be mandatory for Universities to use African languages in some of their programmes. Of course this step may not be met with glee by everybody because "for those to whom an African-centred approach is like a red flag to a bull, the prospect of the above raises the ire and frightens others. But this does not need to be so. The elevation of African languages and culture in South Africa to equality, and the demographic centrality they deserve is only an exercise in democracy and an expression of the cultural rights of the people of South Africa" (Prah 2006: 23). Prah's assertion is that South Africa is an African country, and therefore, its African languages as languages of the majority, cannot remain at the periphery forever. By practically according African languages the status they deserve, South Africa will be simultaneously celebrating its genuine African character and thus shedding its temporary skin as the pseudo-European country many would like to believe it is. It is worth observing that should African languages be neglected as languages of teaching and learning, South Africa will not be able to grow either economically and politically. Prah (2006: 20-21) puts it bluntly when he contends that "development in South Africa cannot be sustained in conditions where the majorities are by purpose or omission, culturally and linguistically disempowered".

It is fashionable of course to argue that African languages lack the requisite terminology to offer Science and Mathematics. This seems to be a delaying pretext or tactic. If such an argument were to be entertained, then African languages will never be developed to such an extent that they would be deemed adequate to offer the aforementioned subjects. The solution is to develop programmes in higher education that utilise African languages as languages of teaching and learning. It is encouraging to learn that this has already started in a few programmes at some universities in South Africa, thus simultaneously meeting societal and student demands that decolonisation of curricula be launched in South African universities. Decolonisation in this context means that apart from reconstructing the curricula to focus on African issues (Heleta 2016: 1), the use of African languages in higher education should also enjoy prominence. It is heartening to state that some universities in South Africa have already started to utilise African languages in various academic programmes. Examples in this regard are as follows (Kaschula 2015):

(a) IsiZulu is a mandatory first-year course at the University of KwaZulu-Natal;

(b) Journalism students at Rhodes University must pass an isiXhosa subject;

(c) A programme called Multilingual Studies at the University of Limpopo is offered in both Northern Sotho and English;

(d) UNISA has in the past few years started to offer all its African language programmes at undergraduate and postgraduate level either in English or an African language. Again, it has embarked on a massive project to translate some subjects from English into African languages. Students in this case will be afforded the choice of using either English or an African language in their studies;

(e) "Both Stellenbosch University and the Cape Peninsula University of Technology offer multilungual glossaries in English, isiXhosa and Afrikaans for various faculties" (Wolff 2018: 4).

Furthermore, at the Universities of Limpopo, Pretoria, South Africa and Venda, students are afforded the choice to conduct their studies in African languages in either English or an African language of their choice at Master's and Doctoral level. Although the issue of vocabulary is still a challenge, one may say that it is an opportune challenge because students and staff end up developing appropriate vocabulary for their fields of study. As Prah (2006: 25) counsels, "what the African language-speaking majorities in South Africa need to do is to ensure that, in as short a time as possible, we develop African languages into languages of science and technology and become equals, culturally and linguistically, of the English-speaking and Afrikaans-speaking communities in the country..." In addition, the Department of Arts and Culture as well as National Lexicographic Units under the auspices of the Pan South African Language Board have developed a large number of multilingual dictionaries and terminology lists that can be successfully applied in the study of most academic programmes offered at universities.

It seems some academics, parents and students are not aware of the advantages of using one's mother tongue in education in general. As Wolff (2018: 5) urges, "re-empowering African languages is a way to contribute sustainably to societal transformation and economic progress by fully exploiting the cognitive and creative potential of all young Africans." Of course it is important not to underrate the fears that academics, parents and students have about using African languages as mediums of teaching and learning. Universities and the government should launch campaigns extolling the virtues of mother tongue (that is, African languages in this case) education. Although job opportunities already exist for graduates in African languages (for example, teaching, language practice, translation and interpreting, writing, and publishing), more practical steps (see recommendations) should still be undertaken to provide better job opportunities in health, science, agriculture and technology for those who achieved their qualifications through the use of African languages. This would go a long way in dispelling the fear that acquiring quality education in African languages would not allow for resultant sustainable employment.

Furthermore, as the hegemony of English in world affairs is a fact that cannot be disputed (Green et al. 2012), it would also be important to assure the aforementioned stakeholders that studying through African languages does not mean that students will not learn English. English will still be presented as a subject and this will have the added advantage of making students become competent bilingual (additive bilingualism) scholars as proposed by Cummins (1991: 70-89) and thus more marketable and suitable for the current epoch. Also, as Haynes (2007: 1) suggests, "learning academic subjects in their native language helps English Language Learners learn English," and "students who have strong literacy skills in their native language will learn English faster." This should immensely assist in resolving the issue of students who are neither good in English nor their mother tongue (that is, African languages) as this step would make them competent in both English and African languages.

From the foregoing narrative, it is self-evident that English would exist for many years to come as a language of teaching and learning in universities. In the same breath, there is no denying that African languages also need to be utilized in universities if South African universities are to decolonise their curricula and also meet their local needs. The argument therefore becomes that both English and African languages should be provided with adequate space to fulfil their respective roles. Rather than being in competition, both these languages can co-exist meaningfully in providing quality education to students. As Wolff (2018: 3-5) postulates, "applying these lessons in postcolonial Africa means embracing truly multilingual education" and "these and other initiatives work towards two outcomes. The first is to produce university graduates who are able to converse freely in both a world language like English and in one or more African languages. A good command of global languages will open a window to the world for all those who've come through such a tertiary system - and put an end to the marginalization of Africa. The second outcome is that ultimately, African societies can be transformed from merely consuming knowledge to producing it. Until today and exclusively, knowledge came to Africa from the North, wrapped up in the languages of former colonial masters. This one-way road must change into a bidirectional one." Wolffs suggestion can only become a reality if African languages are afforded the opportunity to be languages of teaching and learning at the highest level, that is, at university. Otherwise, Africa will remain a begging bowl (materially and intellectually) for many years to come.

5. Recommendations

In the quest to fortify African languages as media of teaching and learning at South African universities, this article provides the following recommendations:

(a) Our elites, politicians and celebrities should speak African languages most of the time to become exemplary to the rest of the country.

(b) Furthermore, what could be done to ameliorate this situation would be for government structures to ensure that there are jobs for those who would have been qualified using their mother tongue.

(c) It would be desirable to use both English and African languages in higher education as this would make students sought-after in the present economic context and pertinent to their communities.

(d) Universities should contribute significantly to the promotion of academic literacy in African languages as this enhances educational access and success.

(e) In pursuance of the preceding recommendation, universities must establish language units whose major role would be to translate teaching material from English into African languages and vice versa.

(f) Instead of presenting all academic programmes in African languages, institutions in South Africa should choose one or a few courses where African languages, together with English, can be used as languages of teaching and learning. For instance, a university may opt to teach History in both English and an African language of the students' choice. In cases of this nature, students may be offered the choice of studying towards the degree in either English or an African language.

(g) Parents must stop dissuading their children from learning an African language.

6. Conclusion

The debate about the appropriateness of using African languages as languages of teaching and learning in South Africa has been taking place for many years. Year in and year out, this topic has been and will still be discussed at conferences and government-sponsored indabas. Critics would often pontificate that it has been all talk, and very little action. However, recently, it is pleasing to note that in spite of seemingly insurmountable challenges, the use of African languages in universities has become a reality; it is no longer a mirage. Slowly but surely, African languages, with the support of government and institutions such as PanSALB, are starting to occupy their rightful place in South Africa. Should the current trend continue, there is no doubt that in a few years to come, much progress would have been attained in this regard. As Mandela (Durando 2013) advises, "it always seems impossible until it's done."

References

Alexander, N. 1989. Language Policy and National Unity in South Africa/Azania. Cape Town: Buchu Books. [ Links ]

Annamalai, E. 2006. Mother tongue education. In K. Brown (ed.) Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics. Elsevier. pp. 342-345. https://doi.org/10.1016/b0-08-044854-2/00650-7

Asante, M.K. 1988. Afrocentricity. Trenton: Africa World Press. [ Links ]

Bamgbose, A. 1999. African Language Development and Language Planning in Social Research. New York: Pearson Publishers. [ Links ]

Bamgbose, A. 2004. Language of Instruction Policy and Practice in Africa. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/education/languages-languageinstruction-africa.pdf (Accessed 22 May 2018).

Brock-Utne, B. 2015. Language of instruction in Africa - the most important and least appreciated issue. Unpublished lecture presented at the University of Limpopo. 13 August, Polokwane.

Caxton, A.S. 2017. The Anglophone Dilemma in Cameroon: The Need for Comprehensive Dialogue and Reform. Available online: http://www/accord.org.za/conflict-trends/anglophone-dillemma-cameroon (Accessed 14 May 2018).

Cook, M.J. 2013. South Africa's Mother Tongue Education Challenge. Available online: http://www.mediaclubsouthafrica.com/youth-and-education/43-culture/culturenews/3555-south-africa-s-mother-tongue-education-problem#ixzz5G9TxF0e3 (Accessed 21 May 2018).

Coughlan, S. 2015. Asia Tops Biggest Global School Rankings. Available online: http://www.bbc.com/news/business-32608772 (Accessed 12 May 2018).

Cummins, J. 1991. Interdependence of first- and second language proficiency. In E. Bialystok (ed.) Language Processing in Bilingual Children. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 70-89. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511620652.006 [ Links ]

Department of Education. 2002. South African Language Policy for Higher Education. Pretoria: Department of Higher Education and Training. [ Links ]

Department of Education. 2003. The Development of Indigenous African Languages as Mediums of Instruction in Higher Education. Available online: www.dhet.gov.za/Reports%20Doc%20Library/Development%20of%20Indigenous%20African%20Languages%20as%20mediums%20of%20instruction%20in%20Higher%20Education.pdf (Accessed 18 November 2019).

Department of Higher Education and Training. 2015. Report on the use of African languages as mediums of instruction in higher education. Available online: http://www.dhet.gov.za/Policy%20and%20Development%20Support/African%20Langauges%20report_2015.pdf (Accessed 18 November 2019).

Department of Higher Education and Training. 2018. The Revised Language Policy for Higher Education (Draft). Pretoria.

Durando, J. 2013. 15 of Nelson Mandela's best quotes. Available online: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation-now/2013/12/05/nelson-mandela-quotes/3775255/ (Accessed 18 November 2019).

Foley, A. 2001. Mother-tongue education in South Africa. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7480/e45690cf7819b8e19de46fb050dbf5da3231.pdf (Accessed 18 November 2019).

Green, A., W. Fangqing, P. Cochrane, J. Dyson,and C. Paun. 2012. English spreads as teaching language in universities worldwide. University World News [Electronic], 8 July. Available online: http:///www.universityworldnews.com/article.php?story=20120621131543827 (Accessed 11 May 2018).

Haynes, J. 2007. Getting started with English Language Learners. Available online: http://www.ascd.org/publications/books/106048/chapters/How-Students-Acquire-Soc (Accessed 11 May 2018).

Heleta, S. 2016. Decolonisation of Higher Education: Dismantling Epistemic Violence and Eurocentrism in South Africa. Available online: https://thejournal.org.za/index.php/thejournal/article/view/9/3/ (Accessed 28 July 2019). https://doi.org/10.4102/the.v1i1.9

Jansen, J. 2013. South Africa's mother tongue education challenge. Media Club South Africa. Available online: http://www.mediaclubsouthafrica.com/youth-and-education/43-culture/culturenews/3 (Accessed 22 May 2018).

John-Steiner, V. and H. Mahn. 1996. Sociocultural approaches to learning and development: A Vygotskian framework. Educational Psychologist 31(3/4): 191-206. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3103&4_4 [ Links ]

Kaschula, R.H. 2015. Reclaiming our languages. City Press. 14 June. Available online: https://city-press.news24.com/Voices/Reclaim-our-languages-20150612 (Accessed 18 November 2019).

Madadzhe, R.N. and M.M. Sepota. 2006. The status of African languages in higher education in South Africa: Revitalization or stagnation. In D.E. Mutasa (ed.) African Languages in the 21st Century: The Main Challenges. Pretoria: Simba Guru Publishers. pp. 126-149. [ Links ]

Madiba, M. 2010. Towards multilingual higher education in South Africa: The University of Cape Town's experience. Language Learning Journal 38(3): 327-346. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2010.511776 [ Links ]

Makamu, T.A.B. 2009. Students' Attitude Towards the Use of Source Languages in the Turfloop Campus, University of Limpopo: A Case Study. MA dissertation, University of Limpopo. [ Links ]

Maclean, R. 2018. Deaths and detentions as Cameroon cracks down on Anglophone activists. The Guardian. 3 January. Available Online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jan/03/deaths-and-detentions-as-cameroon (Accessed 14 May 2018).

Menakapriya, P. 2016. Challenges in learning English as a second langauge. South Asian Journal of Engineering and Technology 14(2): 22-25. [ Links ]

Nkwashu, D., R.N. Madadzhe and S.J. Kubayi. 2015. Using Xitsonga at the University of Limpopo. South African Journal of Higher Education 29(3): 8-22. https://doi.org/10.20853/29-3-485 [ Links ]

Olivier, J. 2009. South Africa: Language and Education. Avaiable online: http://salanguages.com/education.htm (Accessed 11 May 2018).

Oxford Royale Academy. 2014. "Why should I learn English?" - 10 compelling reasons for EFL learners. Available online: https://www.oxford-royale.co.uk/articles/reasons-learn-English.html (Accessed 09 June 2019).

Pluddemann, P. 1999. Multilingualism and education in South Africa: One year on. International Journal of Education Research 31: 327-340. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0883-0355(99)00010-5 [ Links ]

Prah, K.K. 2006. Challenges to the Promotion of Indigenous Languages in South Africa. Review Commissioned by the Foundation for Human Rights in South Africa. Cape Town: The Center for Advanced Studies of African Society. [ Links ]

Pretorius, F. 2011. The Boer Wars. Available online: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/victorians/boer-wars-01 (Accessed 11 May 2019).

Republic of South Africa. 1996. The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Turuk, M.C. 2008. The Relevance and Implications of Vygotsky's Sociocultural theory in the Second Language Classroom. ARELCS 5: 244-262 [ Links ]

University of Limpopo. 2006. Language Policy of University of Limpopo. Polokwane: University of Limpopo Printers. [ Links ]

Welsh, D. 2009. The Rise and Fall of Apartheid. Jeppestown: Jonathan Ball Publishers. [ Links ]

Wolff, H.E. 2018. African Universities Should Use African Languages not just English, French and Portuguese. Available online: https://qz.com/africa/1201975/african-universities-should-use-african-languages-not-just-english-french-and-portuguese (Accessed 11 May 2019). https://doi.org/10.1080/10118063.1996.9724068