Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus (SPiL Plus)

On-line version ISSN 2224-3380

Print version ISSN 1726-541X

SPiL plus (Online) vol.58 Stellenbosch 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.5842/58-0-838

PART I: FORMAL LINGUISTICS

The associative copulative and expression of bodily discomfort in Northern Sotho

Mampaka Lydia Mojapelo

Department of African Languages, University of South Africa, South Africa E-mail: mojapml@unisa.ac.za

ABSTRACT

This article discusses one of the meanings expressed by the associative copulative construction with -na le, 'have' in Northern Sotho, namely to 'physically experience discomfort', 'suffer from' or 'be ill with' something. In light of alternative available verbs that are employed to express the same concept in specific ways, this article aims to investigate the occurrence of such alternative verbs, their semantic relationship with -na le 'have' and with each other. A lexical semantics investigation involving verb classes, selectional restrictions and paradigmatic sense relations reveals that -na le 'have' functions as a superordinate in a troponymy relationship with these verbs. It also shows that these verbs are not on the same level in the hierarchical scheme, placing -bolaya 'kill', -tshwenya 'trouble' and -swara 'catch'/ 'hold' just below -na le 'have' as they select both body-part and affliction arguments. The rest of the verbs are positioned on a lower level, selecting either body-part or affliction.

Keywords: Associative copulative; verb classes; bodily discomfort; troponymy; Northern Sotho.

1. Introduction

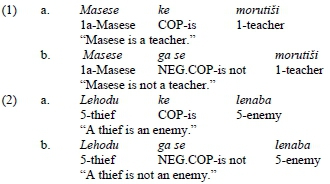

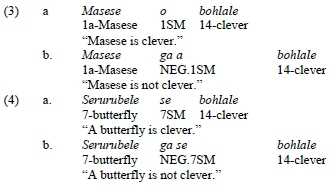

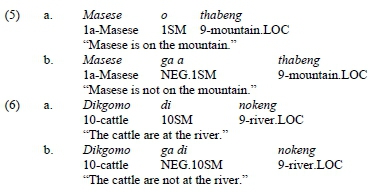

The major Northern Sotho grammars identify -na as a copulative verb stem occurring in the associative copulative construction. Louwrens (1994: 40) asserts that, in some grammars, a distinction is drawn between the concepts copula and copulative, according to which the term copula is used to refer to the 'linking' prefix/verb only. Poulus and Louwrens (1994: 290) state that copulatives are "assigned different names depending on the type of information that they convey". The associative copulative is one of either three or four types of copulatives, as distinguished by a number of Northern Sotho grammars. Lombard (1985), Louwrens (1991), Louwrens (1994) and Van Wyk et al. (1992) distinguish three types, namely the identifying, descriptive and associative copulatives. Poulos and Louwrens (1994), however, add the locational copulative to the aforementioned three (cf. also Lanham 1953), thus stating that there are four types. Poulos and Louwrens' (1994) types, below1, illustrate the disparity regarding the number of types presented in these grammars:

Identifying copulative

Descriptive copulative

Locational copulative

Associative copulative

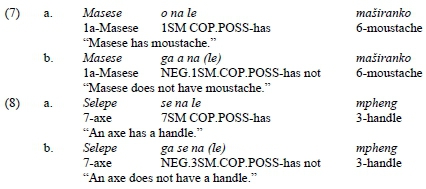

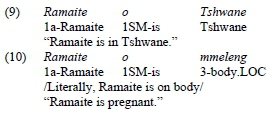

Examples (1.a) - (8.b) above reflect a variety of copulative constructions in Northern Sotho. Each copulative type is illustrated with subjects from different noun classes. As demonstrated by examples (1) and (2), the identifying copulative construction has an invariable copula ke 'is' or 'are' (negative: ga se 'is not' or 'are not'), which is not affected by the change in the noun class of the subject. The rest of the copulatives include the subject agreement marker, and this is also evident in their variable character. Poulus and Louwrens (1994: 317) note that as far as form is concerned the locational copulative is "identical to the descriptive copulative, the only difference between the two being that the descriptive copula describes the subject in terms of a specific feature, whereas the locational copula expresses the locality in which the subject finds itself. Hence, distinction between the two should be based on what they express rather than on the form they take. It is of importance that, in Northern Sotho, not all locational nouns are morphologically marked and also that not all nouns that are morphologically marked with locational affix -(i)ng necessarily express location, as is illustrated by the following two examples:

Tshwane is a place name, which does not need morphological marking to be interpreted as referring to location. The literal translation of (10) is that Ramaite 'is on a body'. The problem with this meaning is that the body can only be hers, which does not make sense. This is a giveaway that the meaning is not literal. What the expression means is that Ramaite is 'with child' or 'pregnant', which would be a typical description of her state of being rather than of her location. The foregoing examples demonstrate that the similarity of the descriptive and locational copulatives in form may be one of the sources of the disparity in the number of Northern Sotho copulatives mentioned above.

The associative copulative has a different form. While it contains the subject agreement marker, it is also identified by the copulative verb stem -na (Lombard 1985; Louwrens 1991, 1994; Poulos and Louwrens 1994; Du Plessis 2010; Ziervogel and Mokgokong 1975: 834), which is always followed by the associative preposition le, if it is in the affirmative. The associative copulative will be discussed separately in the next section.

2. Associative copulative

The associative copulative in Northern Sotho consists of the copulative verb stem -na, preceded by the subject agreement marker and followed by the associative prepositional phrase headed by preposition le. The associative preposition le is optional in the negative, but obligatory in the affirmative. This structure, SM-na-le-NP, forges a relationship of 'association' between the subject and the complement NP. The form -na is found in other Bantu languages (Batibo and Rombi 2016; Du Plessis 2010), also preceded by the subject agreement marker, but the preposition le, or any counterpart, is not necessarily available in other languages. Setswana and Sesotho are similar to Northern Sotho in form (cf. Batibo and Rombi 2016; Du Plessis 2010). Examples of other languages with -na as part of the associative copulative structure are isiXhosa (Du Plessis and Visser 1992; Du Plessis 1999), isiZulu (Hlongwane and Nkabinde 1998), Tshivenda (Mushiane 1999), Ikalanga (Letsholo 2012), Digo, Herero and Swahili (Gibson et al. 2019). Batibo and Rombi (2016) attribute the existence of the associative copulative, as it functions today, to the process of grammaticalization as it evolved from the Proto-Bantu linking word na, which means 'and' and 'with'. In discussing the evolution of na in Bantu languages, Batibo and Rombi (2016) note that:

The two original functions of na, as marker of coordination or association of syntactic units, has been maintained in most Bantu languages. However, some languages have extended its use through the process of grammaticalization to assume other functions. The most common are:

From a coordinative to a copula

(Batibo and Rombi 2016: 73)

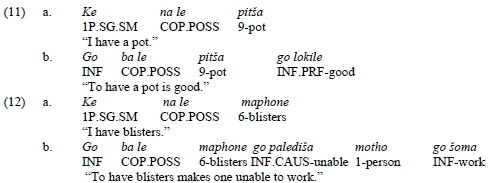

As far as Northern Sotho is concerned, the remnants of the original functions of -na, as described by Batibo and Rombi (2016), are fading away along with the spoken form used by the much older generations. This form is also difficult to find in written texts. Closer to this archaic function of -na is what Ziervogel and Mokgokong (1975: 834) identify only as "a connective formative before absolute pronoun", where for example there is an option to shorten le yena 'and him/her' or 'with him/her' to naye. In Northern Sotho -na functions as a copula and every first language speaker will be familiar with this function in both spoken and written form. It is upon this function as copula, as observed by Batibo and Rombi (2016), that the current lexical study focusses. Although the verbal form -na may change according to mood and actuality, the form that will be used for illustration in this article is the principal form of the indicative mood, in the positive, as this is considered the basic form. When the mood or actuality changes, the copulative verb stem changes form too, such as in the following (b) examples where -na becomes -ba in the infinitive mood:

Semantic interpretation of the copulative with -na also shows similarities across the languages mentioned. Batibo and Rombi (2016) maintain that, in some languages, the original functions of the Proto-Bantu na have been extended to assume other functions, the most common of these being as a copula to express existential meaning, as a temporal aspectual marker, and to denote possession. Letsholo (2012: 7) identifies three main functions of na- as expression of existential meaning, the notion of possession and "the idea of being 'with' [is] often referred to as 'associative' meaning". Du Plessis and Visser (1992) find that the interpretation of the copulative verb with na in isiXhosa is usually possessive. Domination of possessive interpretation is also expressed in Gibson et al. (2019).

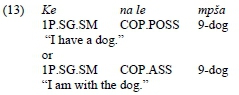

Poulos and Louwrens (1994) and Taljard (2013) attest to the presence of two interpretations of the associative copulative in Northern Sotho, namely ownership/possession and association. Poulos and Louwrens (1994: 311) explicate that, depending on the context in which they are used, sentences such as the following can have one of two interpretations:

Another semantic interpretation of the associative copulative, of interest to this article, is the expression of 'suffer from' or 'be ill with' something. It is debatable whether this is a separate significance - that is, if it relates to either possession or association, or to both of them. In other words, the question is whether suffering from an illness constitutes ownership of the illness or being in its company. The associative copulative expresses this sense in a general way in Northern Sotho. However, it is possible to express the same concept in different, specific ways using various verbs. These specific ways were examined, and the verbs involved recorded. This article aims to investigate the occurrence of such verbs and their relationship with the latter sense of the associative copulative in Northern Sotho. Questions such as the following needed to be answered: When and why is one verb preferred over another verb or other verbs to express a certain 'bodily state and damage to the body' (Levin 1993)? What argument selection do these verbs present? Are they substitutable by one another? What are the sense relations that hold between these verbs? What are the sense relations that hold between these verbs and -na le

'have'? Answering these questions requires looking into concepts such as verb classes, sense relations and selection. The following section will briefly explain these concepts, and the remaining part of the article will analyse the data that relates to -na le 'have' as in 'suffering from' or 'being ill with' something using semantic feature analysis. The main semantic features that will guide the analysis in ascertaining selection patterns are body-part, affliction and bodily excretion.

3. Verb classes

The notion of verbs classes is explained by Levin (2009: 1) as "sets of semantically-related verbs sharing a range of linguistic properties, such as:

- possible realisation of arguments

- interpretation associated with each possible argument realisation."

In keeping with the identified linguistic properties above, Levin (2009: 1) further cites Fillmore's study of the verbs 'break' and 'hit' which demonstrate the significance of "verb classes as:

- devices for capturing patterns of shared verb behaviour

- a means of investigating the organisation of the verb lexicon

- a means of identifying grammatically relevant elements of meaning."

According to Levin's (1993) model of verb semantic classes used for English, a verb's meaning influences its syntactic behaviour, and this can largely be determined from the alternation patterns of verbs. Levin (1993) distinguishes broader verb classes such as 'verbs of motion', which can further be classified into narrower classes such as 'roll verbs', 'chase verbs' and others. One of Levin's classes is 'verbs involving the body'. Under this class are several subclasses including 'verbs of bodily state and damage to the body', which further includes classes such as 'pain verbs'. The current article discusses verbs that are commensurate with Levin's (1993) English 'verbs of bodily state and damage to the body'. In explaining the semantics of such verbs, Levin (1993: 226) states that "these verbs relate to the occurrence of damage to the body through a process that is not under control of the person that suffers the damage". She further notes that this verb class takes body part objects that are possessed by the subject and is often restricted to a few specific body parts as objects.

Verbs that are in the broader sense expressible by -na le 'have' as in 'suffer from' or 'be ill with' in Northern Sotho will be considered for this discussion. Most of these verbs have primary meanings unrelated to 'bodily state and damage to the body', but have the additional semantic function of expressing specific forms of 'suffering from' or 'being ill with'. Since classes of verbs are grouped on semantic grounds, it is worth looking into the notion of sense relations in order to determine their relatedness.

4. Sense relations

The sense of a linguistic expression is its meaning, or any one of its meanings, as seen from its relationship with other linguistic expressions in a language. Trask (2007) defines sense as the central meaning of a linguistic form, regarded from the point of view of the way in which it relates with other linguistic forms. He further notes that the sense of a linguistic form is often formalised as its "intension - that is, as the set (in the formal mathematical sense) of all the properties which an object must have before the form can be properly applied to it" (Trask 2007: 255). According to Crystal (2008: 432), sense is a "system of linguistic relationships which a lexical item contracts with other lexical items". Semantics recognises that linguistic expressions exist and make meaning in a language by being in relation with one another. Sense relations are therefore semantic relations that hold between lexical items (cf. Palmer 1976; Lyons 1977). On a theoretical basis, a distinction is drawn between syntagmatic and paradigmatic sense relations2. Syntagmatic sense relation refers to the relationship that "a linguistic unit contracts by virtue of its combination (in a syntagm, or 'construction') with other units of the same level" (Lyons 1977: 240). Cruse (2000) notes that these linguistic units that occur in the same sentence also stand in an intimate syntactic relationship. Therefore syntagmatic relationships involve collocations and selections.

A paradigmatic relationship, on the other hand, "holds between a particular unit in a syntagm and other units which are substitutable for it in the syntagm" (Lyons 1977: 241). Paradigmatic sense relations include synonymy, antonymy, homynymy, polysemy, hyponymy, meronymy and troponymy. Among them are paradigmatic sense relations of identity and inclusion (Cruse 2000: 150-161). For example, hyponymy is a paradigmatic sense relation of identity and inclusion. A paradigmatic sense relation of inclusion holds between sense units that relate to each other in a hierarchical order, with the general sense unit called the superordinate (hyperonym) at the top, along with a number of subordinate units called hyponyms (cf. also Lyons 1977). Hyponyms are not synonymous, but they are used to express a shared general conceptual phenomenon (Brinton 2000). For example, motho 'human being' is a superordinate with hyponyms monna 'man', lesea 'infant', maphodisa 'police', molwetsi 'patient' and ngaka 'doctor', which are co-hyponyms of each other. Hyponymy is a relationship of entailment - to say Y is a doctor suggests that Y is a human being, but the converse does not apply. Other sense relations of inclusion are meronymy and troponymy.

The term "troponymy" was formulated by Fellbaum (1999) in the context of WordNet3specifically for predicates to denote a sense relation that refers to a manner of doing something or a manner in which something happens. Troponymy and meronymy are both sense relations of inclusion, but differ in that meronymy is a part-whole relationship while troponymy involves 'a manner of doing something'. For example, ntlo 'house' is a superordinate with meronyms tlhaka 'roof, leboto 'wall', lebati 'door', and other component parts of a house. As a sense relation of inclusion, troponymy is characterised by a hierarchy and entailment. For example, the verb stem -bolela 'speak' as a superordinate has troponyms such as -hebaheba 'whisper', -kgakgana and -kgamakgametsa 'stutter/stammer'. It stands to reason that -hebaheba 'whisper' entails -bolela 'speak' but that the converse does not apply. Similarly, -sepela 'walk' has troponyms such as -nanya, 'walk slowly', -phakisa 'walk hurriedly', -gwataka 'walk fast, defiantly or arrogantly' -nanabela 'walk with the aim of catching someone or something you stalk', and several others. In terms of predicates that express bodily discomfort, the associative copulative with -na le 'have' seems to represent a superordinate in a troponymy relationship with several verbs that form the data for this article. Therefore, this article will look at the occurrence of those verbs and how they behave in relation to argument selection.

5. Selection

Selection, specifically s-selection in contrast to c-selection, refers to the inclination of the predicate to decide on the semantic content of its arguments. "S-selection is forced by the semantics of the governing verb" (Crystal 2008: 427). In the realm of 'selection' we encounter 'selectional restrictions' and 'selectional preferences', where co-occurrence is prohibited or preferred on semantic grounds. Trask (2007: 250) explains selectional restriction as "a restriction on the combining of words in a sentence resulting from their meanings". An example of selectional restriction is a verb stem -nwa 'drink'. The primary meaning of -nwa 'drink' can only select arguments with the semantic feature [+fluid] and is restricted from selecting arguments with the semantic feature [-fluid]. However, in extended metaphoric senses, argument selection may be widened. In Northern Sotho the concept of mammal birthing is represented by different words, depending on the mammal concerned. -belega selects [+human] arguments such as motho 'person' and mosadi 'woman'; -tswala selects [-human] and [+bovid] such as kgomo 'cow' and pudi 'goat'; -hlatsa (lit. 'vomit') selects [-human], [-hatching] and [-bovid] such as mpsa 'dog' and katse 'cat', which includes both canids and felids. To use the verb stem -tswala with motho 'person' in reference to a birthing process would be considered an insult, unless it appears in a non-literal or special type of context such as descent information and genealogy. Such contexts are most prevalent in traditional poetry, where the subject is usually [+ male], thereby excluding the literal birthing process. Similarly, the verb used to express being pregnant is -ima for a human being; -dusa for a cow; -gwemehla for a dog; and -emere [stative past] for a scorpion.

6. Associative copulative construction with -na le 'have' and verbal expressions of bodily discomfort in Northern Sotho

As indicated earlier in this article, in their extended senses, the Northern Sotho verbs that will be considered here are generally commensurate with Levin's (1993) verbs of 'bodily state and damage to the body'. Such verbs were, first of all, identified by considering how else the concept of 'suffer from' or 'be ill with' could be expressed. This is generally expressed by the associative copulative with -na le 'have'. The initial data was gathered from general knowledge of afflictions and how they are expressed in Northern Sotho. Alertness of usage in spoken language and searches of sources such as Ziervogel and Mokgokong (1975), the Northern Sotho Language Board (1988) and health-related documents followed. A list of possible arguments, such as names of afflictions, body parts that may be involved in physical discomfort and names of bodily excretions were also recorded. The associative copulative construction was examined, along with the recorded verbs, for selectional patterns, and semantic feature analysis was used to determine the kind of arguments that they prefer.

The following verbs were identified as expressing specific manners of -na le X 'have X', where X is either a body part, affliction or bodily excretion. Most of them have distinct primary meanings that are not related to having any bodily discomfort, and those primary meanings are reflected in the accompanying literal English equivalents.

-bolaya 'kill'

-swara 'catch'/'hold'

-tshwenya 'trouble'

-opa 'hit'/'knock'

-rema 'chop',

-loma 'bite'/'sting'

-sega 'cut'

-tswa 'come out'/'appear'

-ela 'flow'

-ruruga 'swell'

-thunya 'explode'

-hlohlona 'itch'

-tshatshama 'fry'

-hlaba 'stab'

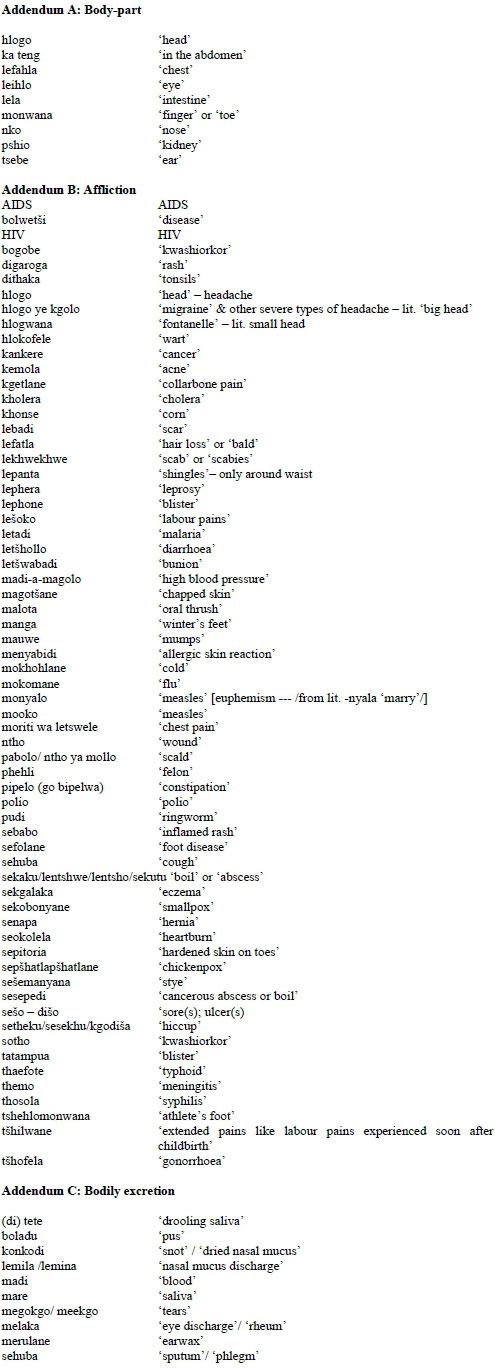

Addendums A, B and C contain examples of candidate complements4 of -na le 'have', categorised into body parts, afflictions and bodily excretions that were used to test selection preferences of -na le 'have' and specific verbs.

6.1 Active-passive encoding in Northern Sotho

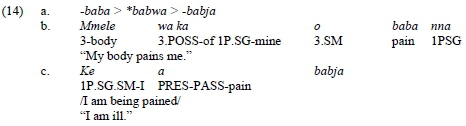

Although statements expressing illnesses and other bodily discomforts may appear in active constructions, placing the illness or body part in the subject position, the alternation pattern that is observed with these verbs involves passive movement. To begin with, the verb for 'being ill' -babja is a passive form. The active form is -baba 'bitter', also 'painful', developed as follows through palatalisation:

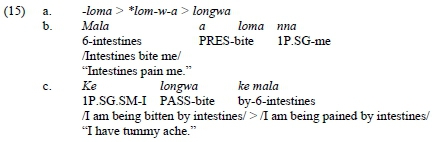

The active construction (14.b) demonstrates that the external argument is the body part or affliction and the internal argument is the [+animate] possessor of the body part or the sufferer of an affliction, respectively. Through passive movement, the original internal argument moves to the external argument position and the original external argument moves to the post-verbal position as the complement of agentive ke. The following examples illustrate this point:

The evolution of the passive form in spoken Northern Sotho sees constructions with an overt complement of agentive ke rendering the passive morpheme -(i)w- redundant. Therefore, example (15.b) above will be spoken as follows:

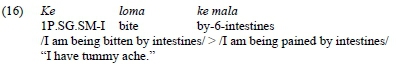

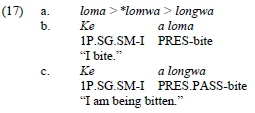

From example (16), above, the presence of agentive ke is sufficient to represent the passive form without inclusion of the passive morpheme -(i)w- in the verb. However, without any overt complement of agentive ke, inclusion of the passive morpheme -(i)w- becomes obligatory in order to capture the passive interpretation, for example:

For more on this phenomenon concerning the passive, refer to Kosch (2003). With the understanding that it is the spoken form that drops the morphological marking of passive sentences when the complement of the agentive ke is present, the examples in this article will retain the passive -(i)w-, consistent with the formal orthographical convention.

6.2 Verbs that select body parts

Examination of the listed verbs above found that the following three verbs5 have a narrower argument selection in comparison with the associative copulative -na le 'have', showing preference to both body-parts and affliction complements:

-bolaya 'kill'

-swara 'catch'/'hold'

-tshwenya 'trouble'

The verb stem -swara 'catch' or 'hold' illustrates, in the following example, the dual selection preference of this set of three verbs:

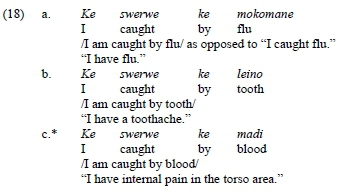

Examples (18.a) and (18.b), above, demonstrate that -swara 'catch' or 'hold' selects both an affliction and a body-part, mokomane 'flu' and leino 'tooth', respectively. -bolaya 'kill' and -tshwenya 'trouble' may be substituted for -swara 'catch' or 'hold' in the same examples and, in a broader picture, also appear with other afflictions and body parts. (18.c) reflects selection of a bodily excretion, however the argument does not refer to the literal madi 'blood', and it therefore disqualifies swara 'catch'/'hold' for this category. In this context it refers to a type of illness. Other afflictions and conditions include pulmonary reflexes such as setheku/ sesekhu/kgodisa 'hiccup' and gastro-oesophageal reflux seokolela 'heartburn', which, similarly, can be expressed by the verbs -swara, -bolaya and -tshwenya.

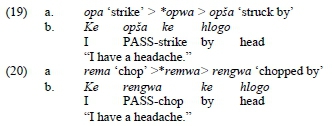

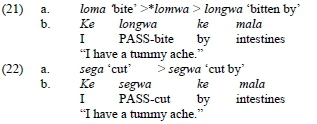

Other verbs seem to select either body-part or affliction, rendering themselves more restricted than -bolaya 'kill', -swara 'catch'/'hold' and -tshwenya 'trouble'. For example, -opa 'strike' or 'knock', rema 'chop', loma 'bite' or 'sting', sega 'cut', tswa 'come out' or 'appear', -thunya 'explode' and -hlaba 'stab'.

The following verbs select body-part arguments, and are restricted to specific body parts:

-opa 'strike'/'knock'

-rema 'chop'

-loma 'bite'/'sting'

-sega 'cut'

Some of these verbs demonstrate an association with conceptualisation of the pain, such as in the case of the types of tummy ache expressed by -sega 'cut' and -loma 'bite'. The next verb does not select body parts.

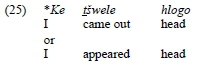

6.3 -tswa 'come out' or 'appear'

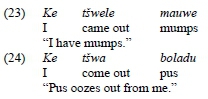

-tswa 'come out' or 'appear' is restricted from taking body-part arguments. It also does not select all afflictions, but only those that appear and can be visually attested to, including bodily excretions. Such afflictions include mauwe 'mumps', digaroga 'rash', diso 'sores', mooko 'measles', pudi 'ringworm', dikemola 'acne', and other conditions that are accompanied by some outbreak, swelling or inflammation. -tswa 'come out' or 'appear' also selects bodily excretions, such as madi 'blood', boladu 'pus' and mamila 'nasal mucus'. The past tense of -tswa is -tswile < -tsw-ile, also written as -tswele. The past tense expresses the state in which the sufferer is, for example:

The following arguments may be substituted for mauwe 'mumps' in example (23) above: seso/diso 'sore(s)' or 'ulcer', digaroga 'rash', sebabo 'inflamed rash', sekgalaka' eczema', bogobe/sotho 'kwashiorkor', lentshwe 'boil or abscess', sesepedi 'cancerous abscess or boil', sepshatlapshatlane 'chickenpox', mooko 'measles', lekhwekhwe 'scab/scabies', sekobonyane 'smallpox', (di)pudi 'ringworm(s)', dithaka 'tonsils', (di)kemola 'acne', lephone 'blister', tatampua 'blister', hlokofele 'wart', sesemanyana 'stye', tshehlomonwana 'athlete's foot', sepitoria 'hardened skin on toes', manga 'winter's feet', magotsane 'chapped skin', malota 'oral thrush',phehli 'felon', menyabidi 'allergic skin reaction'. These are all names of illnesses. The semantic feature that binds these nouns together restricts selection of body-parts. For example, hlogo 'head', would not be substituted for any of these nouns - the following sentence would be silly and meaningless:

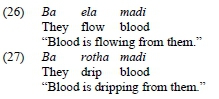

The difference between examples (23) and (25) is that a head does not suddenly appear because it is sore. Moreover, the appearance of a head does not visually differentiate between a person having a headache and the one who does not. Example (24) illustrates selection of a bodily excretion. Other, more specific words that express -tswa 'come out' or 'appear' are -ela 'flow' and -rotha 'drip'. Similarly they do not select body-part arguments. Examples:

Examples (26) and (27) differentiate the manner or intensity of bleeding as a flow and a drip.

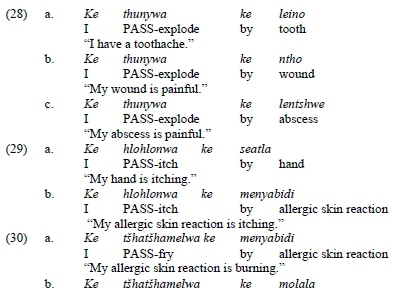

6.4 -thunya, -tshatshama, -hlohlona, and -hlaba

Closely related to the verbs in the previous discussion are the following verbs which, in a very narrow sense, express the manner of experiencing the pain or discomfort which will inevitably link to the body part likely to be so affected. The verbs are -thunya 'explode', as of tooth ache or painful bone, -tshatshama 'fry', literally, to cause the sound made by something roasting -in terms of pain this means to suffer burning pain on the skin, -hlohlona 'itch', -hlaba 'literally, stab', that is, to have a stab-like or stabbing pain:

The verb -thunya 'explode', which expresses a particular manifestation of pain, selects body parts such as the knee, wrist, shin, hip, collarbone and other bone structures. -thunya also selects other nouns discussed under -tswa above, if the intensity of the pain is high. The following examples illustrate the selection:

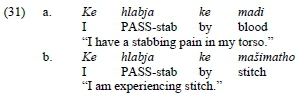

6.5 -hlaba 'stab'

In its use of denoting bodily discomfort, the verb -hlaba 'stab' expresses a stabbing pain. In terms of illness, -hlaba 'stab' appears in metaphoric contexts, and it selects the nouns madi 'blood' and masimatho 'stitch'. The passive form is -hlabja < -hlabwa*. The following examples illustrate the usage of -hlaba 'stab' and its selectional preferences:

7. Summary and future work

The discussion in this article is focussed on the function of -na as copula; yielding the construction SM-na-le-NP. The copulative construction with -na le 'have' is the general expression of 'bodily state and damage to the body' relating to various bodily discomforts. The concept can also be expressed through various verbs which assume additional senses over and above their primary meaning. The verbs -bolaya 'kill' , -tshwenya 'trouble' and -swara 'catch' or 'hold' express bodily discomfort in senses narrower than -na le 'have', while selecting both body-part and affliction complements. Other verbs such as -opa 'struck', -rema 'chop' -loma 'bite' and -tswa 'come out' or 'appear' demonstrate narrower selection than -bolaya 'kill' , -tshwenya 'trouble' and -swara 'catch' or 'hold' in that they select either body-part or affliction. However, their selection is also confined to specific body parts. -tswa 'come out' or 'appear' is restricted not only from body parts, but also from afflictions that are not visible. Hence, -tswa 'come out' or 'appear' selects arguments that refer to conditions such as swelling, scalding and outbreaks.

The scenario with -na le 'have' and the rest of the verbs generates a hierarchy where -na le 'have' is the superordinate. The next level in the hierarchy is occupied by -bolaya 'kill' , -tshwenya 'trouble' and -swara 'catch' or 'hold'. The rest of the verbs are positioned on the third level in different groups, such as those that select only body-part arguments, those that select affliction arguments and -tswa 'come out' or 'appear', which select only certain types of afflictions. This makes -na le 'have' a superordinate in a troponymy relationship where the other verbs are co-troponyms of each other. There are also verbs such as -thunya 'explode', -hlohlona 'itch', -tshatshama 'fry' and -hlaba 'stab' that express a manner of manifestation of a particular discomfort. These verbs seem to constitute a separate sub-class which needs to be investigated further and connected to the other sub-classes.

The intention is to continue to build on these lists of verbs and to improve the analysis into a more systematic one that is almost all-inclusive. Another point of interest would also be to look into the connection between the primary meanings of the verbs that are used for this extended sense, in order to determine how they relate to the conceptualisation of the pain or of the body part in which the pain is experienced.

References

Batibo, H.M. and M-F. Rombi. 2016. The evolution of Na in Bantu languages. Linguistic and Literary Broad Research and Innovation 5(1): 71-77. [ Links ]

Brinton, L.J. 2000. The Structure of Modern English: A Linguistic Introduction Vol 1. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Cruse, A.D. 2000 Meaning in Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Crystal, D. 2008. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. 6th edition. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing. [ Links ]

Du Plessis, J.A. and M. Visser. 1992. Xhosa Syntax. Pretoria: Via Afrika. [ Links ]

Du Plessis, J.A. 1999. Lexical Semantics and the African Languages. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University. [ Links ]

Du Plessis, J.A. 2010. Comparative Syntax: The Copulative in the African Languages of South Africa (Bantu). Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University. [ Links ]

Fellbaum, C. 1999. The organization of verbs and verb concepts in a semantic net. In P. Saint-Dizier (ed.) Predictive Forms in Natural Language and in Lexical Knowledge Bases. Boston: Kluwer Academic. pp. 93-109. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-2746-4_3 [ Links ]

Gibson, H., R. Guérois and L. Marten. 2019. Variation in Bantu copula constructions. In M. Arche, A. Fábregas and R. Marin (eds.) The Grammar of Copulas Across Languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 213-242. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198829850.003.0011 [ Links ]

Hlongwane, J.B. and A.C Nkabinde. 1998. Some Issues in African Linguistics: Festschrift, AC Nkabinde. Pretoria: J.L. van Schaik. [ Links ]

Kosch, I.M. 2003. Sandhi under the spotlight. South African Journal of African Languages 23(3): 144-153. https://doi.org/10.1080/02572117.2003.10587213 [ Links ]

Lanham, L.W. 1953. The Copulative Construction in Zulu: With a Comparative Study of the Construction in the Bantu Language Family. BA Hons dissertation, University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Letsholo, R. 2012. The copula in Ikalanga. South African Journal of African Languages 32(1): 1-9. https://doi.org/10.2989/saial.2012.32.L2.1125 [ Links ]

Levin, B. 1993. English Verb Classes and Alternations: A Preliminary Investigation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Levin, B. 2009. Where do verb classes come from? Paper presented at the Verb Typologies Revisited: A Cross-linguistic Reflection on Verbs and Verb Classes Conference, Ghent University, Ghent, Belguim, February 5-7 2009. Available online: https://web.stanford.edu/~bclevin/ghent09vclass.pdf (Accessed 15 August 2018).

Lombard, D.P. 1985. Introduction to the Grammar of Northern Sotho. Pretoria: J.L. van Schaik. [ Links ]

Louwrens, L.J. 1991. Aspects of Northern Sotho Grammar. Pretoria: Via Afrika. [ Links ]

Louwrens, L.J. 1994. Dictionary of Northern Sotho Grammatical Terms. Pretoria: Via Afrika. [ Links ]

Lyons, J. 1977. Semantics Vol.1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Mushiane, A.C. 1999. The Preposition na in Venda. MA dissertation, University of Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Northern Sotho Language Board. 1988. Sesotho sa Leboa Mareo le Mongwalo No. 4/ Northern Sotho Terminology and Orthography No. 4/ Noord-Sotho Terminologie en Spelreëls No. 4. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Palmer, F.R. 1976. Semantics: A New Outline. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Poulos, G. and L.J. Louwrens. 1994. A Linguistic Analysis of Northern Sotho. Pretoria: Via Afrika. [ Links ]

Taljard, E. 2013. 'To be (with)' or to 'have'? A case of grammaticalisation in Northern Sotho. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 21(3): 169-181. https://doi.org/10.2989/16073610309486339 [ Links ]

Trask, R.L. 2007. Language and Linguistics: The Key Concepts. London: Routledge [ Links ]

Van Wyk, E.B., P.S. Groenewald and L.J. Louwrens. 1992. Northern Sotho for First-Years. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Ziervogel, D. and P.C.Mokgokong. 1975. Pukuntsu ye kgolo ya Sesotho sa Leboa/ Comprehensive Northern Sotho Dictionary / Groot Noord-Sotho woordeboek. Pretoria: J. L. Van Schaik. [ Links ]

1 The examples appear in the indicative mood, present tense, affirmative and negative.

2 Crystal (2008) includes derivational sense relations as well

3 http://wordnet.princeton.edu

4 The possibilities concerning what body part can be affected by which disease are endless.

5 Only the verb stems will be used in this article since the full verb involves a host of different prefixes.