Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus (SPiL Plus)

On-line version ISSN 2224-3380

Print version ISSN 1726-541X

SPiL plus (Online) vol.57 Stellenbosch 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.5842/57-0-810

THEME 2: THE WRITING CENTRE AND ONLINE SPACES

Evaluating the Synthesis Model of tutoring across the educational spectrum

Rebecca Day BabcockI; Aliethia DeanII; Victoria HineslyIII; Aileen TaftIV

IDepartment of Literature and Languages, University of Texas Permian Basin, USA. E-mail: babcock_r@utpb.edu

IIDepartment of Literature and Languages, University of Texas Permian Basin, USA E-mail: dean_a@utpb.edu

IIIDepartments of Literature and Languages and Psychology, University of Texas Permian Basin, USA E-mail: victoria.hinesly@gmail.com

IVDepartment of Literature and Languages, University of Texas Permian Basin, USA E-mail: aileenrt@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

The goal of this study is to verify a grounded theory model of tutoring developed by Babcock, Manning and Rogers (2012) using qualitative research literature as data. The four participants in the current study (three females) were recruited using a convenience sample as they were current or former tutees of the authors. One participant was a middle-school student while the others were college students. To obtain data, participants were tutored by the researchers either online (asynchronously) or face-to-face. Researchers coded the data based on audio recordings of face-to-face sessions and written artefacts of online tutoring sessions. The results support the model developed by Babcock et al. (2012). It is important to verify the grounded theory model since it will close the circle with grounded theory research to apply it to authentic tutoring data. Researchers have proposed grounded theory in tutoring but no one has yet attempted to verify a model. While the original model covered extensive topics such as communication, personal characteristics, outside influences, emotions, temperament, and outcomes, in this brief report we focus mainly on personal characteristics and outside influences. The model fits the data except in the case of asynchronous online tutoring, likely because the original data was from 1983 to 2006 and did not cover much online tutoring.

Keywords: tutoring, tutoring model, grounded theory, asynchronous tutoring, online tutoring

1. Introduction

Both peer tutoring and the writing centre have become widely explored topics of research within the last two decades. Several tutoring models that explicate the intricacies of tutoring sessions have been proposed by various researchers. One of these models was developed by Babcock, Manning and Rogers (2012) in their book entitled A Synthesis of Qualitative Studies of Writing Center Tutoring, 1983-2006 (henceforth, A Synthesis). There are many benefits of creating a model of tutoring that accurately explores the various facets of a tutoring session. First, knowing what influences the session is helpful for tutors. For example, tutors should be aware that "other people" (those outside of the tutor and tutee's relationship) influence the tutoring session. Second, understanding what occurs in a tutoring session allows educators, including tutors, to improve their teaching strategies. If it becomes clear that one particular facet of the model - active/passive roles, for instance - plays an important role in the tutoring session, educators and tutors would be able to identify easily that aspect of the tutoring session and work to either adapt to one of those roles or subvert them. Lastly, when a model exists for a complex phenomenon or situation, it is easier for one to understand what happens when x, y or z occurs. In other words, more research can be conducted on causal relationships between facets in the model, which can lead to better teaching/tutoring, better understanding of the complex processing happening in the tutoring session, and increased efficiency in the writing centre and among peer tutors.

The goal of the study reported on in this article was to verify the grounded theory model of tutoring developed by Babcock et al. (2012). This model was developed through a grounded theory investigation using published studies as data. Members of this research team read studies, wrote memos, and developed categories and codes to produce a grounded theory model of writing centre tutoring sessions (see section 1.1 below). In order to investigate space, place, and power, the current research team decided to test the grounded theory model in order to see if a model based on college and university writing centres would apply to tutoring sessions across different contexts. For the current study, we recruited participants from various places and spaces, e.g., from a university, a community college, and a private tutoring space. All participants were tutored outside of a formal writing-centre setting, for example, at home, at a coffee shop, or online. The four participants (three females) were recruited from a convenience sample of the authors' current tutees. To obtain data, participants were tutored by the researchers either online (asynchronously) or face-to-face. The researchers then compared observed data to the Synthesis Model, which was created using a method of research called "grounded theory". This method will be discussed further in the subsequent sections.

1.1 Background on the grounded theory tutoring model

In A Synthesis, Babcock et al. (2012) produced a description of what happens in tutoring sessions based on actual data using grounded theory. The data comprised published research studies and dissertations. Holton and Walsh (2017: 63) indicated that "of course, extant literature can be used as data, particularly if the literature is empirically grounded". In this case, Babcock et al. made sure that the literature was indeed empirically grounded by eliminating studies from the analysis that did not include actual data. In addition, they used the data presented in the studies for analysis. Babcock et al. produced grounded theory which indicated that college and university writing centre tutorials are Vygotskyan scaffolding events (Babcock et al. 2012; see also Mackiewicz and Thompson 2014, Nordlof 2014, Thompson 2009). A Vygotskyan scaffolding event occurs when a more experienced individual helps a less experienced individual with a task that is just above the less experienced individual's ability level. Through modelling, explanation or some other means of instruction, the more experienced individual helps the less experienced individual enter that potentially impossible task thereby increasing the less experienced individual's capacity to complete the task at hand. The research team did not jump to this conclusion but rather based it on painstaking analysis of grounded theory data.

What follows in the excerpt below is the grounded theory tutoring model that the original team developed to describe the tutoring process. Codes are italicised, and categories are bolded for clarity:

Tutor and tutee encounter each other and bring background, expectations, and personal characteristics into a context composed of outside influences. Through the use of roles and communication, they interact, creating the session focus, the energy of which is generated through a continuum of collaboration and conflict. The temperament and emotions of the tutor and tutee interplay with the other factors in the session. The confluence of these factors results in the outcome of the session (affective, cognitive, and material).

(Babcock et al. 2012: 11-12; emphasis added).

1.2 Evaluating grounded theory

For the current study, we wish to test and evaluate the original grounded theory model developed by Babcock et al. (2012), mentioned above, to see if it applies to tutoring sessions in other contexts. According to Glaser (1998), grounded theory can be modified or verified by comparison to other data. The phrase "close the circle" is often used when talking about grounded theory. The process of grounded theory is purely inductive and, consequently, a model or theory emerges from collected data. Without additional research, the model or theory that emerged is only applicable to the data from which it emerged. It is possible, for example, that from the metaanalysis of 55 studies, Babcock et al. (2012) did an exquisite job of grouping data into meaningful categories but missed a category that might have emerged if they had evaluated a 56th study. Therefore, in order to verify a model or theory, it needs to be tested against data that was not part of the original study (which is what the phrase "authentic/actual data" refers to - "authentic" or "actual" because it is from outside the context of the original grounded theory work). The current study is not itself a grounded theory study but rather an evaluation (test) of the 2012 study. Although grounded theory emerges from data, we feel it must also then be tested and verified, after the model is established, within studies independent of the original grounded theory work and from other contexts. Holton and Walsh (2017) present Glaser's (1998: 18-19) criteria for evaluating grounded theory as follows:

1. Fit - model is valid and aligns with the concepts in the data;

2. Workability - concepts sufficiently account for people's concerns and what is going on;

3. Relevance - research relates to the interests of the stakeholders and others; and

4. Modifiability - model can be modified as we encounter new data.

Glaser intended this model for "judging and doing theory" (Glaser 1998: 18; original emphasis) but Holton and Walsh (2017) presented it as a way to evaluate theory, which is how we use it here.

It is also necessary to clarify that the term "validate" is used loosely in the context of grounded theory, particularly for the current study. One cannot truly validate a theory or model, which is why it is a theory and not a law or fact. A researcher can only "falsify" a model. The term "validate" has been used in extant literature, and is used here in accordance with that literature. By "validate," we mean that we are testing the validity and practicality of the model for predicting outcomes in tutoring sessions. It is possible that this model is not comprehensive of all tutoring sessions; however, in the current study, we aim to evaluate the effectiveness of the Synthesis Model at predicting facets of a tutoring session.

1.3 Literature review

The current study aims to evaluate a model of tutoring established through grounded theory; the study itself does not use grounded theory but our approach is similar. In the original grounded theory work, Babcock et al. (2012) reviewed data from 55 studies, and allowed a model of tutoring to emerge from the data. The current study did the opposite of this - the researchers took the model developed by Babcock et al. (2012), and compared their actual tutoring sessions to the model in order to evaluate whether the model could be applied to real tutoring sessions in various contexts, spaces, and places, in addition to the studies that the theory emerged from in the original grounded theory work. Although the goals of these two studies were contrary to one another, the outcome is the same: to determine whether a model of tutoring is representative of real tutoring sessions. Therefore, the literature review for the present study is consequentially similar to a literature review for grounded theory. Creswell (2013) suggests delaying the literature review in grounded theory studies, case studies, and phenomenological studies because the current literature should not guide the study but rather explain patterns and categories once they have been identified. Similarly, Glaser (1998) lists some dangers of looking first to the extant literature: being "grabbed by received concepts that do not fit"; developing "a preconceived [...] problem of no relevance"; becoming "imbued with speculative, non-scientifically related" concepts that "are not relevant" (Glaser 1998: 67); becoming "awed out" by famous researchers; and becoming "rhetoricalized," that is, sounding like the literature rather than oneself (Glaser 1998: 68). This is not to say that researchers should not read. On the contrary, Glaser suggests that researchers should read widely in other fields to maintain theoretical sensitivity. Thus, while a grounded theory researcher will not include a literature review after the report's introduction (where it is expected), the researcher will refer to relevant literature in the discussion, comparing and contrasting findings. Our initial goal was simply to verify whether these categories and patterns occur in tutoring sessions across various places and spaces. After this occurred, we sought to explain the patterns and categories in the model as it related to our study. Consequently, much of the literature addressed will be delayed until the discussion.

There is, however, relevant literature regarding the practicality of verifying grounded theory models and other models similar to that of Babcock et al. (2012). As previously mentioned, these authors created a model of tutoring by looking at 55 studies reported over a period of 23 years. They used a grounded theory approach to allow a model of tutoring to emerge from their data. Hartman (1990), although working from a theory-driven analysis rather than allowing data to build the theory, devised a very similar framework for tutoring. For instance, Hartman divided her model into cognitive variables: metacognition and cognition; affect such as beliefs, values, motivation, and attitudes; and environmental context such as the academic and non-academic context. Factors in the academic context can include types of tutoring, background knowledge, educational environment, and content to be learned. It also includes teacher- or learner-centred approaches. Non-academic factors can include cultural, linguistic, socioeconomic, and family background forces. These look like Babcock et al.'s (2012) categories of "Personal Characteristics" and "Outside Influences". It is uncanny how close Hartman's model came to what Babcock et al. (2012) found, even though she was working 20 years before, and from theory rather than data.

Another theoretical model is that of Jenkins (1979, reproduced in Rings and Sheets 1991). This model involves learner characteristics like motivation, learning styles, and culture; strategies, such as time management, categorising information, and predicting test questions; materials, such as print and media; and the task at hand which includes learning goals.

It is important to verify tutoring models, and to base those models on actual tutoring data that were not originally part of the grounded theory work. For instance, Thompson et al. (2009) tested writing centre lore by surveying student and tutor satisfaction with conferences based on common beliefs about tutoring, such as student comfort and non-directiveness. Other studies, such as that of Hall (2017), used tutor intuition to guide his list of "Valued Practices for Tutoring Writing" (pp. 16-18) rather than data from actual tutoring sessions. Hall and his tutors used this list to assess tutoring sessions held at his writing centre.

2. Research question

With the aforementioned in mind, our research question that guided the study reported on in this article is as follows: Using the categories and concepts developed by Babcock et al. (2012) in A Synthesis, how does their grounded theory model of tutoring apply to tutoring sessions in other contexts?

3. Methods

The research methods for this IRB-approved study included recruiting the participants, recording and transcribing tutoring sessions, and then coding the data according to a checklist based on Babcock et al.'s (2012) study. The main concerns regarding reliability of the results lie in the criteria of confirmability, reflexivity, and dependability (Lincoln and Guba 1985). To address these concerns, data were recorded with a handheld audio-recording device. This allowed data to be reviewed several times thus increasing confirmability. Additionally, multiple researchers assessed different participants over long periods of time, therefore increasing dependability and transferability. Concerns about reflexivity are inevitable in qualitative research, and these limitations will be addressed.

3.1 Participants

The researchers tutored four students (three females). One was Indian-American, one was Caucasian, one was Hispanic/Latina, and one's race was unknown. The students were recruited using a convenience sample, as each was a current or former tutee of one of the researchers so the researchers had ready access to these tutoring sessions. Each student was at a different educational level, including a seventh-grade student, a community college student, a graduate student, and a master's graduate taking a freshman-level composition course. Dean's data were asynchronous (email and MS Word documents with Track Changes) while Hinesly and Taft's data were collected face-to-face either at the tutee's home, at a coffee shop, or on campus.

Dean tutored students as a writing fellow (course-based tutor) assigned to two online freshman-level courses, and all sessions were conducted asynchronously via email and through the Canvas Online Learning Management system. Throughout the summer, only one student who reached out to her for tutoring sessions maintained contact throughout the duration of both summer sessions. Hinesly and Taft conducted face-to-face sessions privately, separate from the university. Hinesly and Taft recruited participants from the group of students they had already been tutoring prior to the beginning of the study. Dean recruited participants as they came to her for tutoring in the class they were taking where she was assigned as a writing fellow. To protect the identities of the participants, pseudonyms replace the participants' real names. There are four participants: Hinesly's student is Anna (a seventh-grader); Taft's students are Julie, enrolled in an online graduate programme, and Mandy, a community college student; Dean's student, Tyrion, is a student with a master's degree taking a freshman course.

3.2 Materials and procedures

Both Hinesly's and Taft's tutoring sessions were audio-recorded using a handheld audio-recording device. After the sessions were recorded, the researchers saved their files onto a password-protected device. They then coded the audio, meaning that they considered every facet of the tutoring model created by Babcock et al. (2012) and, using a checklist, noted either the presence or absence of each category and subcategory. Dean's data consisted of papers with Track Changes and feedback comments, and email messages. She printed out this data and coded it according to the same checklist. Since three of the researchers were tutors in the sessions, they also used introspection as a form of data collection. For instance, the tutor could comment on her own comfort or frustration in the session.

3.3 Data analysis and presentation

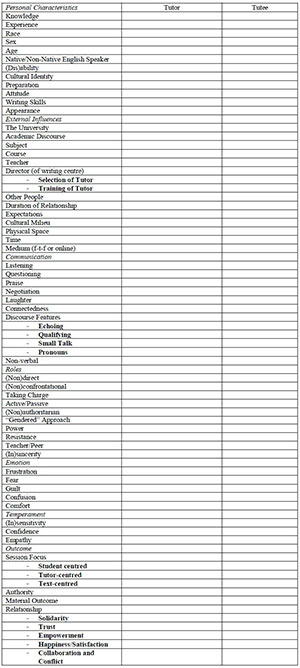

Primary coding strategies were based on the main categories found by Babcock et al. (2012) in their grounded theory study, which the current study proposes to test with the collected data. These categories were: Personal Characteristics, External Influences, Communication, Roles, Emotion, Temperament, and Outcome (see Appendix A of this article for a sample of the checklist and a completed coding matrix). While coding, the researchers considered all facets of the model for both the tutee and the tutor. During the write-up phase, rather than including evidence of each code under the appropriate section, for the reader's convenience, we have chosen to present them by tutee while still highlighting the relevant concepts.

4. Results

To obtain results, the researchers compared their data with what they would expect to find if the Synthesis Model was indeed inclusive of the facets of the tutoring sessions. In other words, they compared their tutoring data with the facets of the model that emerged from the original grounded theory work done by Babcock et al. (2012). Overall, the Synthesis Model was a good fit for the synchronous tutoring sessions. However, it was not a good fit for the asynchronous online tutoring sessions. The results from each participant will be examined in the following subsections.

4.1 Anna

Anna was a middle-school student who was being tutored at home in preparation for the SAT. The following facets of the tutoring model influenced Hinesly's session the most: Outside Influences including expectations, cultural milieu, and duration of relationship; Communication in general; Roles including active/passive roles; and Outcomes such as the trust aspect of a developed relationship.

Anna's cultural milieu was an Indian-American environment in which education, respect, and success were highly valued. The Synthesis Model of tutoring explicitly states that the cultural milieu does not include the culture an individual brings with them. However, Anna's culture that she "brought with her" was evident because all sessions were held at her home. The culture of Anna's home is much different than that of a writing centre. The place and space, which influenced the cultural milieu, impacted the tutoring sessions more than any other part of the model.

Along the same lines, the expectations (under the subcategory of Other People) that Anna's parents had for her played a role in her attitude and willingness to learn. As noted in Table 1, the original meaning of "expectations" in the Synthesis Model was geared toward the expectations that tutor and tutee have for each other. It seemed necessary that the expectations that other people held for both the tutor and the tutee would go along with this category as well. It was clear that Anna was not necessarily self-motivated. The expectations placed on her seemed to be the main motivation for her success in mastering the content being taught. A salient example of the expectations placed on Anna was that she was being tutored in SAT reading comprehension and SAT grammar. Keep in mind that she was in the seventh grade, and the SAT is not taken until the summer of one's third year in high school. Thus Anna was preparing for the SAT four years before she would actually take the exam.

Communication, in general, was another facet of the model that influenced every session. Anna mostly listened to Hinesly, there was little negotiation, and Anna was unwilling to ask questions or express confusion (which is under the emotion subcategory in the model). This goes hand-in-hand with active/passive Roles. Anna was passive in the tutoring sessions, which required Hinesly to take the active role. This is the most salient example of power roles between tutor and tutee. The only verbal communication that occurred in the first few sessions was elicited by the tutor and not by Anna. Even when spoken to, Anna would either give very short and quiet responses, or would not respond verbally at all. Most communication between Anna and the tutor was non-verbal, especially from Anna. For example, Anna answered most questions with a head nod.

Finally, the duration of the relationship and trust became important aspects of the sessions. After several months of meeting with Anna, she began to become comfortable with Hinesly. This influenced Communication and active/passive Roles. When Anna began to trust Hinesly, she opened up more, asked questions, directed some of the sessions, and became an active participant in the sessions. She verbalised more in general, used longer sentences to answer questions, and explained the answers when asked.

Overall, most aspects of the model fit the tutoring sessions. Some of the subsections in the model were not salient in every session but most subsections were applicable over the course of the tutoring relationship as a whole. Because of Anna's age, some sections of the model were not applicable, such as The University and Course, especially with regard to how they were meant to be applied as in the 2012 model.

4.2 Julie and Mandy

Julie is a non-traditional student, enrolled in an online graduate programme, and Mandy is a community college student. The categories from the tutoring model that impacted Taft's tutoring sessions either with Julie or Mandy are as follows: External Influences such as selection of tutor, duration of relationship, and other people; Communication such as praise and small talk; and Temperament such as confidence.

The participant, Julie, was first introduced to Taft through a random selection when they both attended the same community college where Taft worked as a tutor. The tutoring relationship continued, and became one of intentionality as Julie frequently set up tutoring sessions with Taft even after they had both graduated and moved on to separate universities. Mandy was introduced to Taft in a similar way - through a college tutoring centre. Mandy continued to seek tutoring from Taft when she was challenged by a particular course in which she did not understand feedback from the instructor. Although selection of tutor in the original model is a sub-category under Director because in most situations the writing centre director chooses the tutor, both tutees in this case actively sought tutoring from Taft outside of the original context of the writing centre. The selection of the tutor affected both relationships and influenced another significant category of the tutoring model under External Influences: duration of relationship. Julie, who sought help with all her courses that involved writing, frequently requested personal tutoring sessions with Taft. The tutoring relationship continued for over six years. Mandy, the other tutee, only intermittently sought tutoring assistance from Taft. The last subcategory under External Influences that impacted the tutoring session was Other People. Multiple interruptions occurred during the tutoring sessions with Julie. Distractions were typically technologically-based, with frequent phone call and text interruptions. When Julie received a phone call or text, often she would silence them but appeared distracted afterwards. At times, when Julie responded to an electronic communication, it normally resulted in conversation between Julie and Taft because Julie wanted to share something from her personal life that arose from the technological interruption from other people.

Communication is another prominent category within the model that influenced the tutoring sessions Taft held with Julie and Mandy, particularly the subcategory of Praise. Taft frequently employed praise to edify her tutees and boost their confidence in their own abilities. Julie showed a lack of self-confidence yet tried to write more without direct assistance, and was more willing to turn work in without going over it with Taft when Taft praised her for a job well-done. While Julie showed more pride in herself by smiling and having greater confidence in her abilities, Mandy reacted to praise in a casual and dismissive way. Mandy made comments such as, "I've known that for a long time. That's not really what I needed to know," and "I know it's right, but the teacher just can't see it. I should have gotten an A". Upon reflection, Taft observed that, in her attempt to build Mandy's confidence, she may have unintentionally aided Mandy in having an aggrandised attitude towards her work which disallowed her to be open to suggestions from both the teacher and Taft. As previously noted when discussing the influence of other people, small talk played a role in Julie's tutoring sessions, which is another facet in the Communication section of the model. Julie would regularly engage Taft in small talk after experiencing a technological interruption. Julie felt comfortable enough with Taft, based upon the extensive duration of their tutoring relationship, that she often wanted to discuss personal matters related to her texts or phone conversations. This often resulted in a distraction from the text, and changed the focus of the tutoring session.

Another category from the tutoring model that influenced the session was Temperament. Taft discovered that the subcategory of confidence became evident through Taft's use of praise, as previously mentioned. When Taft praised Julie for utilising good writing practices or for grasping a concept discussed during a session, Julie exhibited more confidence in her writing, and was excited to share her work with Taft. Mandy's confidence was boosted in a negative way by way of praise from Taft, as formerly stated. Mandy would insist upon incorrect grammatical conventions and composition elements because she had an exorbitant amount of misplaced confidence. Another influential element to the subcategory of confidence was an online editing program called Grammarly®. When Julie began using the program to edit and proof her writing before a tutoring session, her confidence in her writing grew. While there were still grammar issues apparent within the texts being examined, there was a decrease in small proofreading mistakes that were typical within Julie's writing. At times, Julie took suggestions from the Grammarly® platform that did not work contextually with her writing, and these areas still needed to be addressed. Overall, Taft felt that Julie was less embarrassed about showing her work to Taft, and exhibited more confidence after using Grammarly®.

4.3 Tyrion

Tyrion's Personal Characteristics are that he is a non-traditional student holding a master's degree in business who returned to college to take courses to improve his writing. In this context, the tutor, Dean, was assigned as a writing fellow to Tyrion's course sections, and was assisted by downloading all of the essays and leaving comments through MS Word's Review function. Therefore, communication took place within Canvas and via email. Dean left comments on all of the students' essays but the communication was mostly one-sided because most students did not respond to the comments. Dean and Tyrion did not engage in small talk, so Dean did not feel that she developed a relationship with Tyrion. Further, most of the sessions remained text-based. As for Roles, Dean took on an indirect role in the sessions. She left many comments that started with "I might do this here" or "I might reword this". She left a comment stating, "The introductory paragraph is good, but be sure to tie this in with the topic, which is literacy". As the course progressed, Dean noted that Tyrion was doing better at staying on topic, so the session focus changed to higher-order concerns such as organisation and conciseness. Dean felt that she could not gauge Tyrion's Temperament or Emotions in the session although she was confident, empathetic, and comfortable with the process. Dean knew that Tyrion wanted to do well because he had stated in the class discussion board that he felt his writing skills were lacking. Dean felt confident that she could help him because his writing skills were not as bad as he thought - he just lacked confidence. Dean knew that with encouragement, Tyrion would do well in the course. Since the data for Tyrion is sparse in comparison to the model, and mostly redundant to the information above, we have chosen not to create a chart.

5. Discussion

The facets of Babcock et al.'s (2012) tutoring model can be interwoven with one another. In Hinesly's case, almost every facet of the model played a role in the tutoring sessions and influenced other facets of the model. Indeed, one can observe that trying to separate aspects of the tutoring sessions is difficult because, for example, comfort levels will be dependent on duration of relationship. In short, it is difficult to talk about only one aspect of the model without talking about the other aspects as well. This is precisely why this model of tutoring is unique, amongst other reasons. Babcock et al. (2012) managed to capture the intricacies of a tutoring session and provide a physical model of it.

5.1 Anna

For Hinesly, External Influences such as Anna's cultural milieu and the duration of the relationship, and Outcomes such as the trust between tutor and tutee were the main facets of the model that influenced the way she and Anna worked together. Hinesly had to change the way she tutored in order to accommodate Anna's needs. Hinesly noted that she had to develop ways to get Anna to speak to her during the sessions. Hinesly had to ask more open-ended questions, ask questions more often, and seek out information from Anna about her confusion. At first, Anna was not willing to communicate confusion, which is essential in a tutoring session. If the tutee is not communicating confusion to be addressed by the tutor, the tutor is not able to complete the task at hand. When Anna gave an incorrect answer, Hinesly praised her and encouraged her rather than scolding her or directly telling her that her answer was wrong. Bell and Youmans (2006) found that sometimes praise was misinterpreted by second-language students. Tutors "used praise as a simple politeness strategy, but tutees misinterpreted it as being genuine" (Babcock et al. 2012: 45). Haas (1986) discussed Goffman's idea of "benign fabrication", where a tutor may praise a tutee to reassure them. The praise is not necessarily merited but it provides the student with a way to feel comfortable with revision.

Perhaps the most influential aspects of the broader category of Personal Characteristics were Temperament and cultural milieu. Anna's preparedness, her willingness to learn, and her attitude toward the sessions were all influenced by her cultural milieu. In the Synthesis Model, the cultural milieu is that of the surrounding (dominant) culture. In the case of Anna, since she lived in an Indian home, that was her cultural milieu, a difference between our study and the model. Many of the other facets of the model were influenced by Anna's Temperament. For example, Temperament influenced Communication, trust, power Roles taken on by the tutor/tutee, and was responsible for the change that stemmed from the duration of relationship. Anna's cultural identity and cultural milieu influenced the sessions in ways that are difficult to analyse because, without delving into how these facets of the model directly influenced Anna's internal thoughts or outward actions, there is no way to know the extent to which they played a role in the sessions.

Salili (1996) observed that teachers in the Asian culture rarely offer praise for a student's performance, and that, when praise is offered, it is done privately and is reserved for the most exceptional achievements on the part of the student. Thus praise is highly sought after by students. Salili cites Liu (1984) who claims that the tendency for Asian students to rely on rote memorisation (without questioning the content) stems from what he calls their "filial piety" -the idea that, in the Asian culture, younger people are expected to accept and obey their authority figures without questioning them. Salili connected these observations about filial piety to those of Ho (1991), who stated that these attitudes are related to subscribing to certain beliefs in an unquestioning manner. The theme of not questioning others is apparent throughout Ho's description of this attitude. Oakland et al. (2011) stated that Indian children have a specific learning style: they prefer practicality and hands-on activities, need many examples, and show a preference for using imaginative styles (they focus on generalisations or overarching concepts). Along the same lines, Indian children appreciate when others offer them praise for their creativity. Salili also states that, of the values exhibited by the Asian culture, educational achievement is paramount. Asian children are raised to work hard and excel in educational settings. Salili (1988) states that Asian parents set very high standards for their children, use harsh discipline to keep them in line with their expectations, and convey negative attitudes toward their children when they perform poorly. These findings support what Hinesly observed in her tutoring sessions with Anna. Indeed, Hinesly never observed praise offered to Anna by her parents, Anna did need many explicit examples, and it was clear that educational achievement was highly valued by her family. Additionally, the claims made by Liu (1984), Salili (1988), and Ho (1991) provide an explanation for Anna's unwillingness to question Hinesly or the content of the tutorial.

Power seems to be an important aspect of the cultural milieu, the relationships between Anna and other people, and the session's outcome. One can interpret, especially from the previous researchers mentioned above, that there is a unique power struggle between the parent and child in Asian culture. Granted, there are power struggles in every parent-child relationship but the expectations for Anna were different than that for most American children, and the way in which Anna dealt with this power struggle was different with respect to how most American children would have dealt with it. Anna responded with submissiveness, obedience, and respect. Additionally, if the space in which the tutoring session was held had not been Anna's home, these power struggles might not have been as evident or important to the tutoring session. Anna was situated in a physical space that was culturally familiar to her, thus almost requiring her to act in accordance with her cultural norms. In conclusion, the space and place in which the tutoring session occurred - namely, Anna's home - accentuated the cultural norms of her and her family which included a unique power struggle between Anna and authority figures. This influenced the session by creating an atmosphere where Hinesly took on the active role and Anna took on the passive role which influenced Communication, expectations, and Outcomes.

5.2 Julie and Mandy

During Taft's sessions with Julie, the categories that had the most dominant presence during the sessions were Outside Influences, Emotions (such as comfort), and Connectedness. In particular, the outside influence of other people via technology and online editing platforms such as Grammarly®, changed the Outcomes of the sessions Taft held with Julie. Demands from Julie's family, in the forms of interruptive phone calls and texts, often pulled her focus away from the session. Although Taft found that it took five to 10 minutes to regain session focus with Julie after she received an electronic communication, the tutor/tutee relationship became more intimate as a result of conversations that occurred which were not session-focused after the interruption. Categorically, this interaction exemplified Small Talk, a subcategory under Communication. Taft reflected that, had she not taken time out of the tutoring session to let Julie address and talk about her personal life, the relationship that is so beneficial to the quality of the tutoring sessions and the outcomes received would not have developed.

Grammarly® fitted into the category of Outside Influences, and produced interesting results within the tutoring sessions between Taft and Julie. While Grammarly® added to Julie's confidence as a writer, she would often show a false sense of security during the tutoring sessions when it would have benefited her to take more care with the mechanics and syntax of the paper. Taft observed that, while Julie did appear to have a paper that was relatively free of grammatical errors as a result of using the electronic editing program, she did not understand why Grammarly® was prompting her to make the changes suggested in her writing, thus causing her growth in knowledge to be stunted. Dembsey (2017) suggests that this is a typical problem for students who use Grammarly® in lieu of a tutor. This online program often uses technical language that may not be familiar to the student, therefore only giving him/her the ability to accept or reject suggested changes without fully understanding the deeper issue within the writing. Dembsey also emphasises the importance of students being able to establish connections between their sentences and the context of the paper as a whole. While the algorithms Grammarly® uses can generally recognise mistakes and suggest accurate corrections, the program often lacks the ability to convey the methodology behind grammatical conventions. Taft was able to identify the issue Dembsey addressed within the tutoring sessions with Julie. Taft reflected that a program such as Grammarly® could be very useful for a tutee if the tutee read all of the prompts closely and sought to understand the changes suggested. This being said, regardless of whether the tutee evaluated the changes Grammarly® suggested before accepting them or made a blanket decision to accept them all, the use of the program changed the dynamics and the focus of the tutoring session.

Bell (1989) found that praise can help inspire confidence in the tutee. In Mandy's case, Taft suspected that she inspired a little too much confidence, causing Mandy to think too highly of her work and thus to resist further suggestions from her teacher and Taft to improve her work. Mandy resisted many of Taft's suggestions, as was the case in Waring's (1995) study.

The relationships between Hinesly and Julie and Mandy were somewhat strained because of Taft's Temperament. It would have been uncomfortable for her to address these issues directly with either Julie or Mandy. Along these lines, Taft was surprised, upon reflection, to find that she had moved from teacher to peer instead of moving from a peer role to a teacher role, as was the case with Julie. This had much to do with the power dynamics between Taft and Julie.

The tutoring sessions we observed and conducted reflected the core finding of Babcock et al.'s (2012) A Synthesis which was that writing centre tutoring sessions are a Vygotskian scaffolding event. Although not all of the tutoring sessions were conducted in a writing centre, we found that scaffolding occurred within the tutoring sessions with Anna, especially regarding essay writing. Anna had the knowledge about how to create sentences and how to think about the various ideas within an essay's framework but did not have the knowledge necessary to construct the essay itself. That is where Hinesly's knowledge and expertise came in, which provided Anna with skills just above the level at which she was. Because Hinesly brought to the session the necessary knowledge about how to create the essay, Anna was able to create an adequate and informed essay using her knowledge about what goes in the essay.

Throughout the duration of the tutoring relationship between Taft and Julie, a noticeable improvement was apparent in Julie's writing. Much the same as with Anna in Hinesly's tutoring sessions, a scaffolding event occurred where Julie understood the class-specific content but could not transfer that knowledge skilfully into writing at the onset of the tutoring relationship. As the sessions progressed, Julie moved through different stages of development in her writing. Initially, she struggled with basic writing skills such as crafting complete sentences and forming paragraphs. Over time, Taft was able to guide Julie through how to create a well-structured essay, advancing from lower-order concerns such as punctuation and mechanics, to higher-order concerns such as organisation and essay development. Julie's content knowledge coupled with Taft's writing knowledge created a scaffolding event where Julie built upon her specific subject mastery and gradually increased her writing ability to produce a higher quality essay as a result. Taft noted that she did not know that Julie was a second-language speaker until Julie told her. This harks back to one of the most famous case studies in writing centre literature, where tutor Morgan did not realise that tutee Fannie was a second-language speaker (DiPardo 1992).

5.3 Tyrion

Dean also observed scaffolding even though most of the communication between Tyrion and Dean was one-sided. Dean noticed improved writing over the summer, and many of the comments and suggestions that she left for Tyrion early in the summer were eventually no longer an issue in his papers. For example, Tyrion struggled to stay on topic in his first couple of papers. Dean once left Tyrion a comment stating, "Although this intro is fascinating, it's a full page of why you admire police officers; it doesn't address anything relating to the prompt which is about the writing that police officers do in their work". By the end of the summer, Tyrion stayed on topic and, as a result, Dean no longer had to give him feedback about this issue.

Perhaps the most striking difference between the synchronous and asynchronous sessions in this study was a result of both place and space. The physical place (or lack thereof) in asynchronous online tutoring drastically changed the communication between Dean and Tyrion. Communication in these sessions needed to be improved. Martinez and Olsen (2015) offer several suggestions for improving asynchronous comments, including the use of audio and video. Dean left comments through the Track Changes feature in MS Word, and most of the emails she sent remained unanswered. She could only assume that if Tyrion had questions, he would respond to her emails. Dean attempted many methods of improving communication, such as sending group and individual emails, but most students did not respond. Tyrion only responded twice with "Thank you", and twice asked when Dean would be leaving draft comments. In one instance, Tyrion asked, "What did you mean when you said 'this sentence is unclear'?". Dean responded by telling him, "The sentence does not seem to fit here, and I am unclear as to what you are referring to". Tyrion said, "Thank you", so Dean assumed that he understood the clarification because he did not communicate any further to negotiate or explain.

Space was also an important influence on the asynchronous online sessions. The fact that Dean communicated exclusively through Canvas and email changed the relationship dynamics. In fact, there was almost no meaningful relationship between Tyrion and Dean. In this particular setting, there were no specific expectations - socially or otherwise - of Dean or Tyrion. The extent of the expectations was that Dean was to comment on students' writing assignments, and Tyrion was not necessarily expected to reply or to use Dean's suggestions. This made for a unique relationship dynamic dependent on both space and place.

Additional factors may have contributed to the lack of communication between Dean and Tyrion, such as the former being assigned to the class as a writing fellow as opposed to the latter seeking out the help of a general tutor at the campus Success Centre. If Tyrion had scheduled a synchronous tutoring session, then he may have been inclined to communicate more. The duration of the classes may have also contributed to the lack of communication as the course was five weeks long. Students would turn in papers by midnight on the specified day, and Dean would download all of the papers, comment on drafts, and upload the papers with the comments by noon the following day. Students usually only had a couple of days' turnaround time before the final papers were due and the draft of the next assignment would be due. Dean responded to emails quickly because the class was so fast-paced, but after she answered their questions, the line of communication closed.

Dean's student's Personal Characteristics were mostly unknown other than what was revealed in the class's online discussion board or through Dean's observation of the web conferences. There may have been unknown External Influences but they were not directly revealed through the sessions. Dean took on a more active role in leaving feedback because that was her role as a writing fellow, regardless of whether or not students asked for feedback. However, she took on a passive role in the type of feedback she left, such as making suggestions for possible alternatives as opposed to telling Tyrion outright to make the changes. Temperament may have been a factor, but it was unknown because it was not revealed in the online sessions. The communication was significantly deficient in the asynchronous tutoring sessions compared with the synchronous tutoring sessions that Dean had conducted in the past. Dean knew the outcome of the tutoring sessions because, as a writing fellow, she had access to the grades and final papers so she was able to look at the papers to see whether the student employed her advice. However, as a traditional writing centre tutor not linked to the course, Dean would not have had access to the discussion boards, conferences, grades, or final products of the drafts.

Many facets of the Synthesis Model may have made an impact on the sessions but much was largely unknown because very little of a personal nature was revealed in the class introduction, and nothing personal, such as age, culture, race, appearance or disabilities, ever came up throughout the tutoring sessions. Tyrion's name was gender neutral, and the other factors were unable to be determined. More research needs to be done to examine whether any of these factors make an impact on asynchronous tutoring sessions as well as the methods to improve communication which might improve the quality of the asynchronous tutoring sessions.

6. Conclusion

The Synthesis Model is comprehensive and transferable across various methods of tutoring. The model is applicable to tutoring sessions ranging from elementary through to graduate students. We found that all the major categories developed by Babcock et al. (2012) were applicable in these different contexts although some of the subcategories were not present because of the smaller sample size.

According to Glaser (1998: 237), one of the strengths of grounded theory in general is that if new data or new incidents occur, "the theory can constantly be modified to fit and work with relevance". The fit was a little off when it came to online tutoring, likely because Babcock et al. developed the Synthesis Model based on research conducted from 1983 to 2006, and there were not many studies of online tutoring to include. Babcock et al. put online as a medium under External Influences. From Dean's analysis, she thinks there should be an entirely separate study just covering online tutoring, both synchronous and asynchronous.

Over the past year, Dean conducted many in-person and online tutoring sessions. As she began analysing the data for this project, she realised that the synchronous tutoring sessions she held in the past aligned with the Synthesis Model just as closely as the online sessions, but the asynchronous sessions were quite different. Many of the key components of a tutoring session which make up the main categories of the Synthesis Model were not present in Dean's tutoring sessions or, at least, they were not able to be detected. Personal Characteristics, External Influences, Communications, Roles, Emotions, and Temperament often contribute to Outcomes so it is vital to examine how these factors (or lack thereof) influence the Outcomes of the tutoring session. Space and place played a significant role in the sessions, particularly for both Anna and Dean's asynchronous online sessions. Power in the form of relational struggles or harmony played a role in the synchronous sessions but not in the asynchronous online tutoring. The biggest diversion from the model occurred within the realm of asynchronous online tutoring.

To conclude, the tutoring session data verified the Synthesis Model with the exception of asynchronous online tutoring. The facets of the model that most influenced the session were: Outside Influences, Personal Characteristics, and Communication. A modification to this study is required to include asynchronous online tutoring. We propose that another study needs to be completed to observe asynchronous online tutoring sessions. This can be done by comparing writing samples before and after asynchronous tutoring as well delivering an exit survey that will attempt to measure the outcomes such as trust, satisfaction, empowerment, etc.

6.1. Limitations of the study

Not all of the categories in A Synthesis were present in our data because we purposefully took a small sample size. Of course, with a larger sample size, we would be able to see examples of more of the categories and perhaps discover new ones. Additionally, we only audio-recorded the tutoring sessions so any data on nonverbal communication was recorded through field notes only. In order to be able to conduct a closer analysis of nonverbal communication, we should have video-recorded sessions (Thompson 2009).

For the purpose of this research, Dean only analysed the data from one student since only one other student made contact, and that contact was minimal. The bulk of the information gathered about the student was gained through access to the class discussion board and through the web conferences, not from the tutoring sessions. The tutoring sessions were very short and to the point. If Dean had not already commented on a draft, the student would contact her and ask when she would return draft comments. The student asked twice for clarification on a draft comment but there was no other communication.

Regarding the trustworthiness of the study, there is a chance that confirmation bias may have played a role in the acceptance of the model as accurate and representative of the tutoring sessions. While none of the authors are aware of such a bias, it could be present which would therefore affect both credibility and confirmability (Lincoln and Guba 1985). To decrease the chance of confirmation bias occurring in a future study, perhaps researchers should first (without considering the Synthesis Model) notate the most important aspects of the tutoring session, and then compare those to the model. With enough participants, a similar model (in relation to the Synthesis Model) should emerge from the data. This is akin to grounded theory but the model already exists. In effect, this would be combining grounded theory methodology and the methodology of the current study. Regarding transferability (Lincoln and Guba 1985), we have shown that the Synthesis Model is accurate across various educational contexts, spaces, and places.

6.2 Ideas for future research

Research specifically on online tutoring should be conducted to examine Communication and Outcomes of tutoring sessions, and other factors for both traditional writing centre tutors and course-based tutors/writing fellows. Because Dean was a writing fellow, she made the initial contact with the students through the draft comments as opposed to the students reaching out to her if they needed a tutor.

More research needs to be conducted on asynchronous tutoring sessions. Denton (2017: 175) states that "discussions surrounding the format of asynchronous online tutoring exemplify the shortcomings of relying on lore alone; a format that could have represented an innovation has instead been largely relegated to the sidelines of the field". Lore should not be dismissed but must be updated as methods of tutoring evolve. Denton (2017: 176) noted "the potentials afforded when writing centre professionals embrace the possibilities that result from interrogation of the field's assumptions through research-based scholarship". If the common components of tutoring sessions are present in the other various forms of tutoring but not in asynchronous tutoring sessions, then research needs to be conducted to determine whether these variables influence the asynchronous tutoring session outcomes. Researchers can analyse and code session notes for online tutoring for future research.

We may need to follow-up with our participants for outcomes such as finding out what revisions they did to their papers or if their papers were improved or how Anna did on the SAT (as demonstrated, not all of our tutoring sessions were specifically about writing papers). In addition, we may need to go back and conduct a close linguistic analysis of the transcripts.

Finally, we may also need to include a Likert-scale exit survey to measure aspects like tutor and tutee comfort and rapport.

According to Glaser (1998), grounded theories can be expanded and generalised for other contexts. For instance, this model of tutoring could be applied to other situations where people relate to each other, such as friendship, office hours, counselling, or tutoring in other subjects. Future researchers should consider studying the ways in which cultural identity and cultural milieu influence the tutor and/or the tutee, and consequently, how they influence the session. Finally, we propose a follow-up to the original synthesis: A Synthesis of Qualitative Studies of Writing Centers, 2007-2020.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Iris Fierro for providing us with access to the necessary data for our project.

References

Babcock, R.D., K. Manning and T. Rogers. 2012. A synthesis of qualitative studies of writing center tutoring, 1983-2006. New York: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Bell, J. 1989. Tutoring in a Writing Center. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Texas. [ Links ]

Bell, D.C. and M. Youmans. 2006. Politeness and praise: Rhetorical issues in ESL (L2) writing center conferences. The Writing Center Journal 26(2): 31-47. [ Links ]

Creswell, J.W. 2013. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Dembsey, J.M. 2017. Closing the Grammarly® gaps: A study of claims and feedback from an online grammar program. The Writing Center Journal 36(1): 63-100. [ Links ]

Denton, K. 2017. Beyond the lore: A case for asynchronous online tutoring research. The Writing Center Journal 36(2): 175-203. [ Links ]

DiPardo, A. 1992. "Whispers of coming and going": Lessons from Fannie. The Writing Center Journal 12(2): 125-144. [ Links ]

Glaser, B. 1998. Doing grounded theory: Issues and discussions. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press. [ Links ]

Haas, T.S. 1986. A case study of peer tutors' writing conferences with students: Tutors' roles and conversations about composing. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section A, Humanities and Social Sciences 47(12): 4390. [ Links ]

Hall, R.M. 2017. Around the texts of writing center work. Logan: Utah State University Press. [ Links ]

Hartman, H. 1990. Factors affecting the tutoring process. Journal of Developmental Education 14(2): 2-6. [ Links ]

Ho, D.Y.F. 1991. Cognitive socialization in Confucian heritage cultures. Paper presented at the Workshop on Continuities and Discontinuities in Cognitive Socialization of Minority Children, US Department of Health and Human Services, Washington D.C.

Holton, J.A. and I. Walsh. 2017. Classic grounded theory. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Lincoln, Y.S. and E.G Guba. 1985. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Liu, I.M. 1984. A Survey of Memorization Requirement in Taipei Primary and Secondary Schools. Unpublished manuscript, National Taiwan University, Taipei. [ Links ]

Mackiewicz, J. and I. Thompson. 2014. Instruction, cognitive scaffolding, and motivational scaffolding in writing center tutoring. Composition Studies 42(1): 54-78. [ Links ]

Martinez, D. and L. Olsen. 2015. Online writing labs. In B.L. Hewett and K.E. DePew (eds.) Foundational practices of online writing instruction. Fort Collins, CO: The WAC Clearinghouse. pp. 183-210. [ Links ]

Nordlof, J. 2014. Vygotsky, scaffolding, and the role of theory in writing center work. The Writing Center Journal 34(1): 45-64. [ Links ]

Oakland, T., K. Singh, C. Callueng, G.S. Puri and A. Goen. 2011. Temperament styles of Indian and USA children. School Psychology International 32(6): 655-670. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034311403041 [ Links ]

Rings, S. and R. Sheets. 1991. Student development and metacognition: Foundations for tutor training. Journal of Developmental Education 15(1): 30-32. [ Links ]

Salili, F. 1996. Learning and motivation: An Asian perspective. Psychology and Developing Societies 8(1): 55-81. https://doi.org/10.1177/097133369600800104 [ Links ]

Thompson, I. 2009. Scaffolding in the writing center: A microanalysis of an experienced tutor's verbal and nonverbal tutoring strategies. Written Communication 26(4): 417-453. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088309342364 [ Links ]

Thompson, I., A. Whyte, D. Shannon, A. Muse, K. Miller, M. Chappell and A. Whigham. 2009. Examining our lore: A survey of students' and tutors' satisfaction with writing center conferences. The Writing Center Journal 29(1): 78-105. [ Links ]

Waring, H.Z. 1995. Peer tutoring in a graduate writing center: Identity, expertise, and advice resisting. Applied Linguistics 26(2): 141-168. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amh041 [ Links ]

Appendix A: A sample of the checklist and a completed coding matrix