Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus (SPiL Plus)

On-line version ISSN 2224-3380

Print version ISSN 1726-541X

SPiL plus (Online) vol.55 Stellenbosch 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.5842/55-0-778

ARTICLES

Recontextualisation and reappropriation of social and political discourses in toilet graffiti at the University of the Western Cape

Fiona FerrisI; Felix BandaII

IDepartment of Linguistics and Modern Languages, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa. E-mail: ferrifs@unisa.ac.za

IIDepartment of Linguistics, University of the Western Cape, Bellville, South Africa. E-mail: fbanda@uwc.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Applying notions of interdiscursivity, commodification of discourse (Fairclough 1993) and semiotic remediation (Bolter and Grusin 2000), this paper analyses toilet graffiti in men's and women's toilets at the University of the Western Cape in order to capture how the toilet walls become platforms where texts associated with other genres and discourses are appropriated, remediated, and transformed for expanded production and consumption of meaning. In turn, it explores the ideological and identity manifestations of the inscriptions in the transformed and remediated semiotic material, and the dialogicality and the trajectory of the texts across space and time. Thereafter, a discussion is presented of the implications of the expanded meaning potentials resulting from blended and recontextualized discourses from other genres and cultural contexts.

Keywords: toilet graffiti, identity, remediation, UWC

1. Introduction

The earliest study recorded on toilet graffiti is by Kinsey, Pomeroy, Martin and Gebhard in 1953. A number of studies then followed which focused on the amount of graffiti written by men and women, and themes, particular those to do with issues around sex and sexuality (Bates and Martin 1980; Bruner and Kelso 1980; Dundes 1966; Farr and Gordon 1975; Flores and Sechrest 1969; Greenberg 1979; Lomas 1973; Stocker, Dutcher, Hargrove and Cook 1972; Pennebaker and Sanders 1976). Studies on social identity in toilet graffiti have also been done in this area but are still scarce (Ferris 2010; Green 2003; Schouwenburg 2012). In their study of male toilets at the University of the Western Cape in South Africa, Ferris and Banda (2015) show how graffiti artists use images accompanied by verbalised forms - such as punctuation marks, capitalisation and other linguistic forms - as semiotic material in the construction of evaluative discourses. They also show how the artists repurpose well-known taboo language and other verbal and non-verbal semiotic material to fine-tune evaluations of 'self' and often the negative 'other', and for new and extended meanings.

As noted above, much of the research on toilet graffiti focuses on the quantity of graffiti written by men and women, as well as the reference contained in the graffiti to sexually related matters and homosexuality. There is thus a need to investigate toilet graffiti from a more dynamic perspective to cater to the areas not much explored in the research. This paper is a contribution to this gap by using a multisemiotic approach to analyse toilet graffiti in men's and women's toilets at the University of the Western Cape (UWC). We particularly focus on how the toilet walls became a platform where texts associated with other genres and discourses are appropriated, remediated, and transformed for expanded meaning production and consumption in the toilet graffiti. This paper also contributes to the call for research on how people use social semiotic or multimodal texts in everyday, mundane spaces for meaning making, the toilet being a particularly under-explored area in South Africa. A number of authors (Kress 2010, Hengst and Prior 2010, and O'Halloran 2011, to name a few) have lamented the dearth in studies in multimodality, especially those designed to sharpen and contribute to the social semiotic theory to multimodality in the contemporary world. This is aptly captured by Kress (2010: 7) as follows:

We do not yet have a theory or tools which allow us to understand and account for the world of communication as it is now. In their absence we tend to use the terms that we have inherited from the former era of relative stability […] but using tools that had served well to fix horse-drawn carriages becomes a problem in mending contemporary cars.

There are two other major universities in the Western Cape province of South Africa. These are the University of Cape Town (UCT) and Stellenbosch University (SU). We situated the study at UWC because, although UCT and SU have made strides in transforming themselves into inclusive universities, they still remain English- and Afrikaans-speaking with 'white' culture predominating even outside the classroom (Bangeni and Kapp 2011; Mafofo and Banda 2014). In terms of linguistic transformation, for instance and Bangeni and Kapp (2011) appear to suggest that black students at UCT are forced to perform 'whiteness' through institutionalised 'white' culture that pervades every facet of UCT, therefore losing their sense of belonging to Xhosa identities. UWC, on the other hand, has been known for championing diversity in both lecturer and student populace from the university's inception during apartheid in the early 1960s (Lalu and Murray 2012). Indeed, Banda and Peck's (2015) studies on social interactions suggest that students at UWC are not encumbered by institutionalised English discourses of the classroom, as they perform linguistic diversity by often using languages other than English outside the classroom. Although the study would be more comprehensive if all the three universities were involved, we thought UWC as a space would present semiotically more diverse samples for analysis in the toilet graffiti because of these abovementioned reasons.

2. Theoretical and conceptual framework

We use notions of 'recontextualisation', 'intertextuality', 'interdiscursivity', 'remediation' and 'commodification' as analytical tools to analyse the ideological and identity manifestations of the semiotic choices made by participants in the social and cultural discourses appropriated. These tools are vital in determining how different discourses are not only appropriated and recontextualised, but how they are also transformed in the toilet graffiti for new meaning.

Intertextuality was first conceptualised by the poststructuralist Julia Kristeva in 1966, and refers to the relationship of texts with other texts in terms of form and content in order to build on them, refute them or to present them as well known (Fairclough 1992; Johnstone 2008; Lefebvre 1971). Kristeva credited this coinage on the influence of Bakhtin's work, particularly his dialogic account of language in "Rabelais and his word" (Bakhtin 1941). Bakhtin (1981) refers to 'intertextuality' as the dialogic qualities of texts; how multiple voices are transformed and reused in texts. This is because texts often acquire their meaning in relation to other texts; therefore intertextuality operates on the notion that no text functions in isolation (Bakhtin 1986).

The intertextual references are those characteristics that are recognisable to the reader because s/he has come across them in other texts. These references are thus not necessarily overtly inherent in the text, but should be interactionally acknowledged and recognised to have significance. Texts thus provide contexts within which other texts may be created and interpreted. In this way, they draw on multiple cues from the wider context in which they occur. These cues can be textual, social or cultural. As a result of this social construction of intertextuality, it is possible for the reader to assign more than one connection and meaning to a text in relation to other texts, depending on one's schemata.

Kristeva (1986) identified two different kinds of intertextuality - horizontal and vertical intertextuality. Horizontal intertextuality refers to how texts build on texts with which they are related sequentially (texts they follow or precede). In this way, texts have been materially incorporated into other texts by referring back to them or pre-empting them. This is also referred to as the material "snatches" in texts that originate from other texts.

Texts can also build on the other texts they are related to in terms their conventions. This is referred to as vertical intertextuality or interdiscursivity. This can be represented in the shared structural forms or rhetoric organisation, and conventions and practices that are associated with various genres. Bhatia (2007) associates interdiscursivity with the creation of hybrid or relatively new constructs by appropriating or exploiting conventional practices, structures or resources associated with other genres and practices. Thus, the analysis of the interdiscursivity of texts is about unravelling the mix of genres and styles on which texts draw (Fairclough 1992). The analysis of intertextuality is about disambiguating and making sense of the mixed and often blurred genres.

The notion of 'interdiscursivity' recognises the heterogeneity of texts. According to Fairclough (1993), texts usually comprise combinations of various discourses and genres. In the process of interdiscursivity, existing texts and genres are transformed into new co(n)texts (Fairclough 1993). In his work on the marketisation of public discourse, Fairclough (1993) illustrates how private domain practices are appropriated and colonised by the public domain. This is through Higher Education, for example, adopting conversational discourse as part of its communication regime and promotional culture. He singles out the promotional culture in Higher Education as having gained prominence over years in a number of information discourses. This is evident in the appropriation of discourses of promotion and advertising in advertisements for posts within Higher Education, and in university prospectuses, leading to an "interdiscursively hybrid quasi-advertising genre" (Fairclough 1993: 157). This signalled the fracturing of the structuring of orders of discourse, as appropriation occurs across these orders. Drawing discourses across genre boundaries and using them as commodities leads to the creation of new identities and social roles. The appropriation and commodification across orders of discourse, and the increasing fuzzy boundaries between these orders, are evident in hybrid genres such as infomercials and edutainment. Because these forms are not only appropriated but form integral parts of the discursive practices at hand as they serve as commodities, the notion of 'remediation' as defined below becomes crucial. In short, issues of appropriation, commodification and colonisation of various discourses become pertinent in the analysis of toilet graffiti at UWC.

When a text builds on other texts in terms of its materiality, practices or conventions, the text's traces are recontextualised and remediated in its new context. When the material is modified and remodelled to suit the purposes of the new context, we say that it is "semiotically remediated" (Bolter and Grusin 2000). Semiotic remediation, according to Hengst and Prior (2010: 1), refers to "taking up the materials at hand, putting them to present use, and thereby producing altered conditions for future action". They further assert that semiotic remediation entails re-presenting, re-contextualisation, re-cognition, re-formulation, and re-use of discourse from prior semiotic resources (Hengst and Prior 2010). It has been noted in the literature that remediation as a conceptual and analytical tool is slippery and one needs to define exactly how the authors are using it (Banda and Jimaima 2015; Irvine 2010; Vandenbussche 2003;). Following Banda and Jimaima (2015) and Bolter and Grusin (2000), we would like to isolate two senses of semiotic remediation: (i) the quoting and recycling of material or content from one medium in another medium, not necessarily for a different purpose, and (ii) the creative reworking of materials and practices as well as the appropriation and transformation of material and techniques for new meanings and purposes. Interdiscursivity and intertextuality are captured in the first sense, while the idea of 'repurposing', that is, accounting for new and extended meanings is captured in the second sense of the notion.

An exploration into semiotic remediation is essential because we are interested in the new meanings that various semiotics acquire in their new contexts and realisations in the confines of a bathroom cubicle. By using semiotic remediation, we assert that the participants are not just borrowing but repurposing semiotic material for new meanings and purposes in new contexts. We are thus going beyond intertextual references and textual borrowing to appropriation and transformation of semiotic material for novel and expanded meanings.

3. Sampling and data collection

Data was collected over a period of ten months, during hours when access of students to the university toilets was minimal (early mornings and late evenings) to avoid "disturbing" the research environment, from the most frequented toilets on the main campus of the University of the Western Cape. A total of 10 toilets were selected, and the codes F and M were selected to differentiate between the data collected in the toilets frequented by women (F) and men (M) respectively. Over 150 tokens were collected for analysis. A token represents a single inscription; this can be in the form of a word, sentence, icon or paragraph. The first period of data collection occurred from June to September 2008. The second period occurred from April to July 2009. The study therefore can be said to be longitudinal, thus enabling a study of phenomena and various transformations over time.

A digital camera was used to collect data. Data that could not be captured by the camera, owing to faded colour, was handwritten or video recorded.

In terms of number, the women's toilets had more comprehensive writings than the men's toilets in the first sample. In the second sample, the data in the women's toilets stayed fairly stable, whereas an enormous increase in data occurred in the men's toilets. Both women's and men's toilets had a range of themes including relationships, love, culture, religion, politics, economics, etc. The graffiti in the men's toilets were more diverse than that found in the female toilets since the male graffiti writers used a number of different forms of expression including pictures, various punctuation marks, colour and so forth to express themselves. The graffiti in the female toilets, on the other hand, consisted mostly of words and the creative use of vectors to indicate discourse flow. The discussion and analysis of the data is arranged according to the emerging themes, namely agony aunt discourses, textese and graffiti as didactics; religious, cultural and social discourses; commodification of sex, and political and racial discourses.

4. "HELP!!!!"- Appropriation of agony aunt discourses

The instances of graffiti found are often transactional in nature. Their instantiation is dialogic in the sense of Bakhtin (1981), and also in the sense of ordinary one-to one conversation. Thus, participants (especially in the women's toilets) frequently ask advice and often receive feedback on their questions posed. From the writing style, as well as the materials used, it appeared that some of the participants return to the toilet stalls and express thanks to their fellow female participants after receiving a response to their queries. In many of these cases, not only is the interactional nature of the toilet graffiti signalled, it also mimics the patient-psychologist interactions in counselling settings. In this section, we discuss how the participants draw on the "agony aunt" genre, and how this genre has been remediated and transformed in the toilet graffiti.

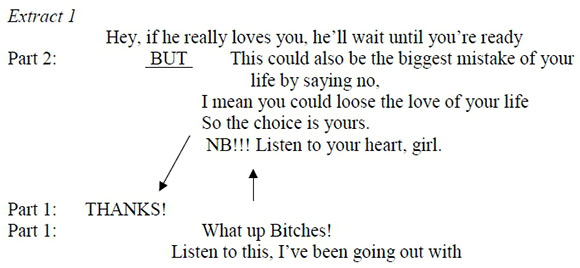

In Extract 1 below, the female participant responds to another participant's query about not being ready for marriage. The presentation of a problem, the evoked attitudes of insecurity, and advice-seeking is common in "agony aunt" genres (Khaustov 2014). In the data collected, the "agony aunt" genre is remodeled to suite the toilet environment. In Extract 1, for example, the politeness strategies in terms of a respectful greeting, which is characteristic of agony aunts, is re-framed in hip hop language (Alim, Ibrahim and Pennycook 2009; Pennycook 2009 as "What up Bitches". The language used is also re-constituted in hybrid form, blending full and truncated words and sentences, as well as formal and conversational styles of writing.

The space is also remediated differently in terms of response flow. The response can be below, above or on the side of the original message. There are restrictions on the number of words written and responses depending on availability of space. In addition, unlike the "agony aunt" genre, the use of names or pseudonyms is absent in toilet graffiti.

Participant 1 intertextually referenced Martha Stewart in the extract above. Martha Stewart is a businesswoman, writer (she has written a number of cooking, baking, lifestyle, housekeeping, business books, etc.), publisher (Martha Stewart Living Magazine), talkshow host and actor who was born in 1941. She is a well-known, mature woman with "expertise" in domestic affairs. By making this intertextual reference, this participant signals that she is not ready to take on this role.

Greetings and the expression of thanks for advice given are also evident in the graffiti found in the female toilets. The participant initiating the conversation and selecting the topic of conversation in the data in most cases starts with a greeting, as is shown in Extracts 2 and 3 below.

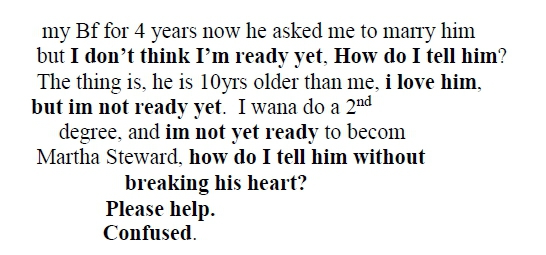

The two extracts above, which occur on the same toilet wall, appear unrelated as both appear to be beginnings of new conversations, yet they complement each other. Both extracts are rich in emotional content. Feelings of negativity colour these extracts. In the first instance, the participant feels displeasure because of the apparent dysfunction of her clitoris. The participant has positive feelings towards sex - "I love it [...] i like sex" - but because of the seemingly physiological problem she has, she feels unhappy. The participant concludes by letting the reader know that she is confused - "Help me what must I do" - since she lacks the knowledge to solve her own problem, which causes her further distress. A structural pattern associated with "agony aunt" genres exists in both extracts. Participant 1 begins from a negative statement of discomfort and unhappiness, which is a result of the disturbance of the participant's enjoyment of sex although she still "loves" sex, which followed with her call for help. The second extract also indicates a similar pattern, but starts with happiness, which turns to feelings of anguish and unhappiness as the participant cannot be with the loved one. Both extracts are framed to make the reader sympathetically positioned towards the participants. In addition, both share the suffering of the other and thus are side by side as if comforting each other.

In both instances, the use of respelled and abbreviated forms in terms of spelling - "Hai" (Hi), "4" (for), "2" (two), "bt" (but), "2gether" (together), etc. - and emoticons - "J" - redefines the conventions of "agony aunt" genres in formal platforms to suit the context of toilet graffiti. This indicates that the participants did not only draw on these genres, but they could creatively remodel them for their own purposes in the toilet environment.

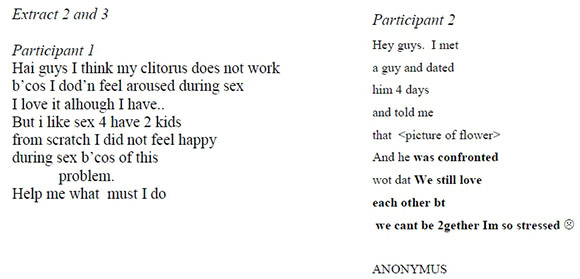

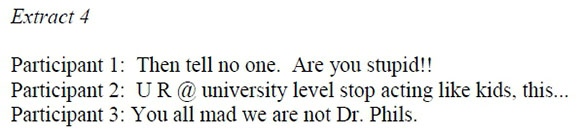

Participants often do not always receive positive feedback on their problems via the toilet graffiti, as the examples below illustrate:

In the first response, participant 1 positions as stupidity another participant's tendency to tell people that she is a virgin, knowing that they mock her every time. The other responses were: "stupid girl", "u r a idiot" and "what a dumb[...]". Participant 2 responds to one girl's comment on the booth discussions in their entirety as a judgement of the female writers as immature. For this writer, university students are expected to act like adults. Participant 3 takes the situationality of the interaction into account. The participant feels that the toilet walls are not an adequate place for seeking psychological advice because the respondents of these types of queries are not psychologists like the famous Dr. Phil (McGraw), who is trained to handle such problems and has a television show. Consequently, remediation fails as the toilet environment is not conducive to seeking advice and, according to these participants, those who use these toilets are not trained to provide expert feedback.

In this section, we have shown that the participants did not simply draw on generic conventions from "agony aunt" genres, but that these genres have also been remodelled in the toilet environment as a feature of situationality. In these instances, transgressive greetings and forms, abbreviated forms, as well as emoticons have been used to blur the conventions of the "agony aunt" genres found in the graffiti. This section also indicates that instances of remediation and recontextualisation are evident because, although the responses mimic that of "agony aunt" genres, the meanings are expanded due to the reframing within the context of the university and the toilet as a site of social discourse with its own affordances.

5. Graffiti as didactic: The use of textese in the context of the university

One of the discourses that is most frequently appropriated in the toilet graffiti, particularly in toilets frequented by women, is didactic communication. Didactic communication is communication with the intent to instruct, teach or moralise excessively (Sabău and Niculescu 2011). In the data collected, a number of the tokens collected were in response to the manner in which language is used, both in terms of the code used and ungrammaticalities. These instances will form the basis of the discussion in this section.

Instructive didactic graffiti was only found in the female toilets. One form of instructive didactic graffiti, which incorporates Mxit code, is discussed in this section. Mxit was an instant messaging application that was popular amongst the youth since its introduction in 2005. However, in recent years, its popularity has declined with the increased use of WhatsApp and other instant messaging devices. The general writing style of Mxit is akin to Textese, texting language or SMS language, which is abbreviated language used in short message services (SMS) of mobile phones or other internet-based communication devices (Thurlow and Poff 2011; Tagg 2012; Dyers and Davids 2015). Characteristics of texting language (henceforth "textese") include the use of abbreviated forms, e.g. "lol" (laugh out loud); the exclusion of vowels in some cases, e.g. "bcz" (because); the use of single homophones to represent words, e.g. "8" (ate); the combination of number and letter homophones, e.g. "gr8" (great), etc.(Tagg 2012; Dyers and Davids 2015).

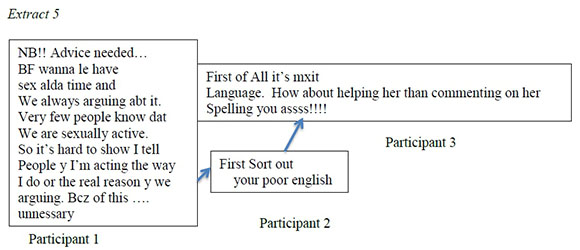

One instance of didactic reprimanding occurs where textese is evaluated against the norms of Standard English. This, in turn, opens the floor to further re-evaluation on the basis of the Mxit "language's" own standards, as the interaction below illustrates.

In this conversation, a participant asks for advice about a personal issue which creates tension with her partner. This in itself is reminiscent of the "agony aunt" genres discussed earlier. The reply that the participant receives has nothing to do with the content of the message; it is, instead, a didactic reprimand based on the previous participant's incorrect style of writing (the use of abbreviated forms such as "alda" for all the and "Bcz" for because) from a prescriptive stance. This writing style also represents what Tagg (2012: 62) calls "colloquial contractions", that is, "contracted written forms which reflect informal pronunciation", and phonetic respelling, which "involves substituting letters in irregular conventional spellings for those which more regularly correspond to the particular sound" (Tagg 2012: 65). Participant 3, in turn, responds to the reply of Participant 1, stating that it is "mxit language" and that the participant should rather assist Participant 1 than scold her for "incorrect" language use. Participant 3 recognises textese as a legitimate code in the toilet graffiti. The blending of the conversational genre (Eggins and Slade 1997) with textese and the "agony aunt" genres can be categorised as genre blending (Fairclough 1993).

It also seems to be the case that phonetic respelling and colloquial contractions in particular "suggest various emotions" the meanings of which evoke elements of identity and register (Tagg 2012: 62). Participant 1, a university student, has reinvented herself as an ordinary and perhaps non-literate person by appropriating, linguistically performing and evoking the identity of a "street smart" person (Alim, Ibrahim and Pennycook 2009). However, Participant 2 (mis)reads the misspellings and colloquial contractions such as "wanna" and "alda" that are indexical of Participant 1's personal, social and education level. This illustrates that a reader's subjectivities may mediate in how they consume or do not consume a particular message. Participant 2 does not respond to Participant 1's cry for help. Thus, in this case, for Participant 2, what Participant 1's message contained in spelling choices is less significant than the readers' interpretations of the level of formality and/or speaker's identity.

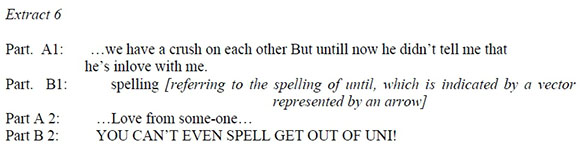

In part, the readers' responses or personal opinions are not based on the advice requested, which deviates from the supportive responses in "agony aunt" genres. These subjectivities are captured in instances in the women's toilets where participants ignored the content of the messages and responded to ungrammaticalities with didactic reprimanding. The extract below is also evidence of this.

In Extract 6 we see that respondents B1 and B2 ignore the contents of the inscriptions and comment on grammatical errors. The responses of B1 and B2 can also be said to be what Bourdieu (1991) calls a misrecognition of standard language as the legitimate code. This didactic response is typical of formal educational settings that have a prescriptive stance on the use of language. Thus, B1 and B2 can be said to extend the idea of the education setting or university classroom as a typical site for misrecognition of the legitimacy of standard language to behind the walls of the toilet. However, this is also typical in comment sections of online newspapers. Banda (2016) has shown in his analysis of comments sections of Zambian online news platforms that there is tendency to attack the writer and his/her language rather than the ideas or content of the messages.

6. Commodification of sex in toilet graffiti

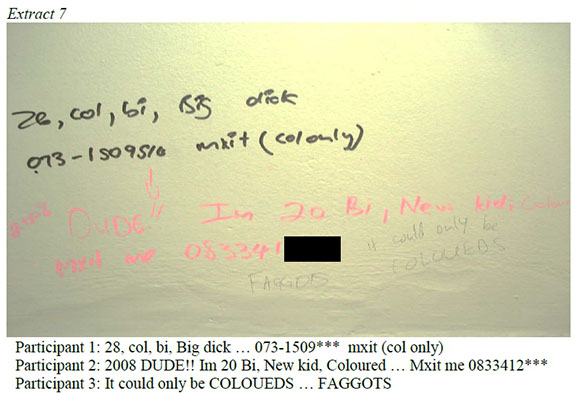

In the male toilets, there were several tokens of graffiti found to resemble advertisements for sexual services in the classifieds section of newspapers. Gonos, Mulkern and Poushinski (1976) discuss graffiti that functions to arrange sexual contact with another user in the toilet as "tea-room trade graffiti". These instances are discussed in terms of their content and resemblance to advertisements about sexual services offered.

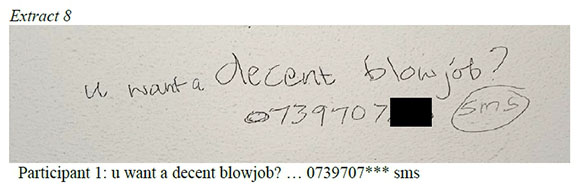

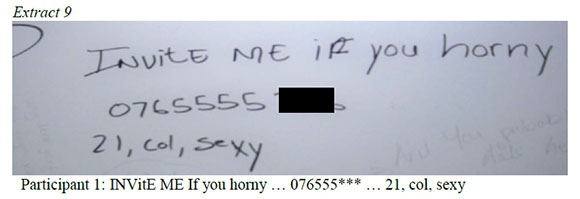

In these extracts, we once again see instances of genre blending in which graffiti resembles newspaper advertisements. In this case, we have descriptions such as "28, col, bi, BIG dick" and "21, col, sexy". In some cases, the kind of client is specified in terms of his level of sexual excitement "iF you horny". In addition, contact details are provided and the preferred methods of establishing contact are specified. An appraisal of the "services" offered is also evident in the word "decent". These are all characteristics of advertisements, which Fairclough (1993) refers to as "marketisation discourse".

Although the script and language use here is similar to one found in newspaper sex service advertisements, the extracts are hybrid sex-and-social commentary when one considers the co(n)texts such as "Faggots" and "It could only be coloureds". Elements of homophobia are introduced and the phrase "It could only be coloureds" borders on racial discourses, that is, discourse designed to denigrate/undermine a targeted racial group. It also draws on prevailing discourses in African countries where homosexuality is thought to be alien to Africans but afflicts 'whites' and other racial groups (Amory 1997 in Chiorazzi 2018), in this case, 'coloureds'.

There were other inscriptions that did not indicate the race of a client or partner. For instance, Extract 8 only mentions the kind of service and mode of communication, while Extract 7 is an open invitation to anyone who is "horny".

The extracts discussed above are in line with Koller and Whiting's (2007: 11) argument that the occurrence of instances of graffiti are to initiate sexual contact in the male toilets and, to a larger extent, to become sites of sexual practices such as masturbation. The advertisement as a genre has thus been appropriated in the toilet stalls to arrange sexual contact.

7. Appropriation of religious, cultural and social discourses in graffiti

The toilet walls also serve to share testimonies, discuss issues of religion as well as to transgress religious norms.

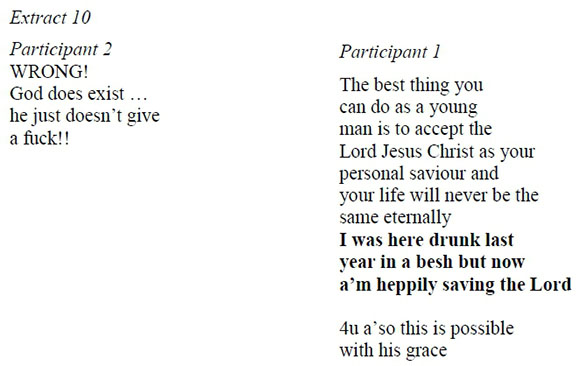

In the context of toilet graffiti, it is not unusual for participants to transgress, even where religion is concerned. In most societies, it is considered taboo to speak negatively about God. In the tokens below, religious discourse is drawn on. Anger (implicit and signalled through the use of exclamation marks) and judgement towards God are expressed.

Male Participant 1 shares his testimony in his writing and explicitly expresses his happiness ("a'm heppily saving the Lord"), his trust in God and his opinion on the acceptance of Him as one's personal saviour ("best thing you can do as a young man"). This participant indicates progression by highlighting the negative space in his life before accepting Jesus, then indicating the change with the word 'but" and the reassurance "your life will never be the same eternally", which is characteristic of testimonies. Participant 2 responds with a counter testimony to the effect that God does not care about people. The selection of words used, as well as the creative use of font and punctuation by the participants, is a symbolic representation of their religious stance. The above extracts are rich in emotional content, although the conflicting emotions are implicitly realised in the contexts of the extracts. The toilet environment thus provided a space in which counter narratives of religion could be provided and consumed.

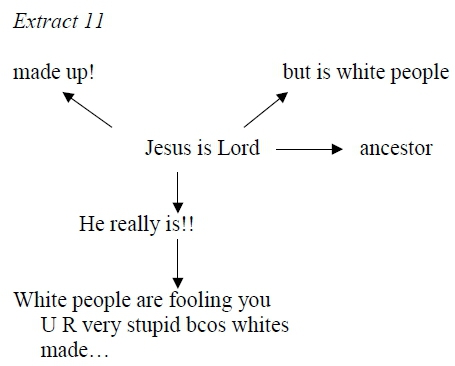

In other instances, religion - or rather ideologies about religion - are framed as integral to cultural and racial identities, as the example below illustrates.

The inscription "Jesus is Lord" provoked both cultural and racial discourses. From one frame, Jesus as being Lord is presented as an idea that is generated by 'white' people. Another participant draws on the cultural reference of ancestors. In this instance, the toilet walls serve as a site for opposing social, religious and cultural discourses. In reality, most Africans live a hybrid life embracing modernity and, most often, Christianity and traditional ways of living, including beliefs in the power of ancestors. This holistic view of religion is captured by Olupon [quoted in Chiorazzi (2015)] when he states that "African spirituality simply acknowledges that beliefs and practices touch on and inform every facet of human life, and therefore African religion cannot be separated from the everyday or mundane."

This interaction also takes on a debate structure in the sense that respondents affirm or negate a statement. The materiality of the toilet graffiti also results in interactions being prompted from any stage or generic move within the communicative process, across the trajectory of time. This results in the reading path of the debate not being linear. The reader, who can also become a potential respondent, is therefore confronted with multiple chains of the interaction at the same time, made possible by materiality of the context, which transcends the trajectory of time.

As is shown above, religious norms are often transgressed in the confinement of the toilet. The toilet walls serve as a platform for contesting religious, cultural and historical views. In addition, dialogicality across time, space and context is evident in these instances.

8. Political and racial discourses in toilet graffiti

In the second phase of data collection, racial and political discourses were prominent in the toilet graffiti collected in the men's toilets. This is attributed to the shift in the political context of South Africa, since this sample was collect in the period when a new South African president was elected, and when the country made headlines for xenophobic attacks in 2009. In this section, we discuss the instances of graffiti focusing on politics, particularly then-president Jacob Zuma and race. The relationship between politics, music and race in the data will be illustrated.

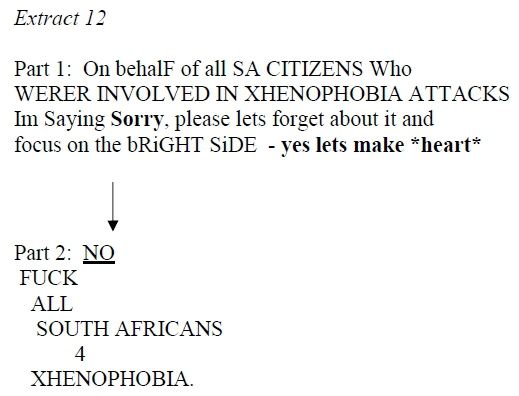

In the first example, Participant 1 apologises to the victims of the xenophobic attacks that started in May 2008 and flamed up again in May 2009. Participant 1's response includes feelings of remorse, repentance and moral anguish, which are evident in the verbal phrase "Saying Sorry". However, this admission of guilt and repentance of the past misdeed on behalf of the attackers is not positively received by Participant 2. He responds by expressing his anger towards South Africans generally and not only those South Africans involved in the xenophobic attacks. Evidently, toilet graffiti can be a source of information on current social issues and what people think about them.

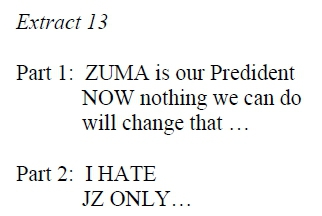

Feelings about the South African president at the time, Jacob Zuma, are frequently and strongly expressed in the data. The following inscriptions in Extract 13 were made after the general election held in late April 2009. Just before then, Zuma was embroiled in some controversies including having intercourse with a woman who was HIV positive. The woman had claimed that she had been raped but the charges were dismissed in court. Despite being acquitted of any wrongdoing, Zuma was still viewed negatively by sections of the South African public. The hopelessness and negative feelings of those who did not want Jacob Zuma to be president are captured below.

Participant 1 saying "nothing we can do will change that" is also reference to the nature of South African politics in which the party that wins the country's general elections chooses the president. Since Jacob Zuma was the president of the African National Congress (ANC), the governing party, he automatically became president when his party won these elections. In expressing his displeasure with Zuma, Participant 2 uses Zuma's initials, JZ, which was also a typically disparaging way in which the media referred to the then-president elect.

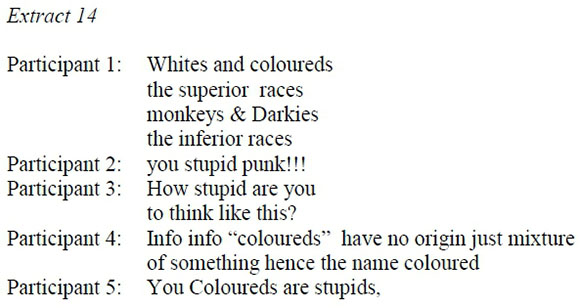

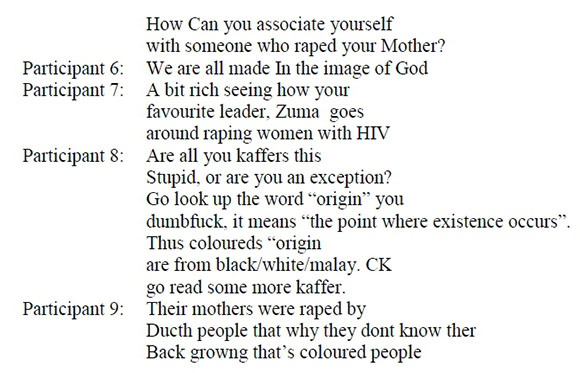

Issues on politics and race are also recreated in the data. These tokens form part of a larger discussion, where racial identities are drawn on and cultural origin is discussed. The general interaction between the participants is hostile and the participants construct themselves as forming part of one segregated racial group. The participants construct a situation where there is animosity between the different races and where 'coloured' people are constructed as oblivious to their origins. Most of these instances specify the receivers to which these emotions are directed. Evidence of othering is also visible in the use of racial labels accompanied by excessive swearing.

Extract 14 starts with Participant 1 drawing on racist discourses and apartheid ideology in which 'blacks' were at the bottom, followed by 'coloureds' and 'whites' at the top the racialised hierarchy. This hierarchy was reflected in the social and economic structure of apartheid South Africa. This triggers a number of negative responses, with some (Participants 4 and 5) questioning the origins of 'coloureds'. It is ironic that Participant 8 opines that the origin of the 'coloured' race is a blend of 'black', 'white' and Malay people, and calls Participant 4 - who is assumed to be a 'black' participant - the loaded and derogatory term "kaffer". The word "Kaffer" is a racist term which is associated with the colonial and apartheid years referring to 'black' South Africans. The capitalisation of "Darkies" in the inscription below is noteworthy; it is used as a proper noun, which reinforces the ideologies of separatism and inferiority associated with the apartheid era.

The origin of 'coloureds' was a ubiquitous topic for discussion in the men's toilets. In Extract 14 above, Participant 8 provides Participant 4, who stated that "'coloureds' have no origin" and are "just a mixture of something and hence the name coloured", with a definition of origin. Participant 8 has a didactic response in the interaction, negatively constructs Participant 4 as a "dumbfuck", and provides him with the suggestion to "go [and] read some more". The use of the inverted commas for "coloureds" in both extracts above is to raise the emotional effects of the utterance as well as to highlight the contested nature of the term. When one considers the context in which this exchange occurs, where 'coloured' people are judged as not knowing about their origins, the inverted commas suggest that the people who call themselves "coloured" are not really coloured. Through the anger expressed in the racial discourse, one also gains an insight into the dissatisfaction the participants experience with regard to racial issues. The use of swearwords is also evident in all three instances discussed below. These swearwords signal the emotions of the participants when the racial inscriptions were made.

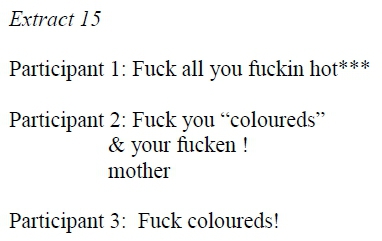

Again, in Extract 15 it is the 'coloureds' that are the target of racist inscriptions. The inscription hot**** refers to "hotnots" (parts of the word have been disguised by making use of asterisks). "Hotnot" is a derogatory word used for people who were classified under the apartheid regime as "Coloured", and who have profound Khoisan ethnic facial features. The lexicon in this instance is therefore intentionally used to belittle people of mixed racial origins.

A historical trajectory is thus evident in the inscription, where separatist ideologies were drawn on in this period when a new president had to be elected. The larger political and historical context therefore influenced the inscriptions in the toilet graffiti in this period of social transformation.

The toilet walls served as a platform for reconciliation, to vent as well as for the expression of emotions which contravene societal norms. Discourse of both tolerance and intolerance is visible in discussions on race, politics and culture.

9. Conclusion

The confines of a toilet seem to disengage some social, political, racial and cultural inhibitions. It provides a rich site for discourses to be decontextualised from their known contexts and recontextualised in the toilet graffiti. Students appropriated and transformed semiotic material from the instructive didactic context, "agony aunt", religious, political, cultural and social discourses for new meanings on toilet walls. Although these discourses were identifiable as belonging to other genres and context, their materialisations were remodelled to suite the spatial and functional limitations of the toilet wall. The extensive use of textese, short sentences and brief passages is indicative of the limitations imposed by the physicality of small and compact walls, as well as the primary purpose of the toilet - as the space to relieve oneself. This also means there is no time for long-winded sentences and extended paragraphs.

The appropriation of discourses from other contexts and practices resulted in multiple points of reference, resemiotisation and remediation of discourses, and the dialogic trajectory across context, space, practice and time. These discourses were informed by and reflected social and political changes.

The material nature of the conversations on the toilet walls spurred replies to any stage of the conversational chain at any time, creating a multidimensional dialogical flow which opens communication to several participants at any point or stage in the conversational exchange, which differs from casual conversation. The "conversational" space therefore created communicational affordances which are not possible with spoken interactions or debates and therefore transcended time and space trajectories.

References

Alim, S., A. Ibrahim and A. Pennycook. 2009. Global linguistic flows: Hip hop cultures, youth identities and the politics of language. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Banda, F. 2016. Towards a democratisation of new media spaces in multilingual/multicultural Africa: A heteroglossic account of counter hegemonic discourses in Zambian online news media. Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus 49: 105-127. https://doi.org/10.5842/49-0-686 [ Links ]

Banda, F and H. Jimaima. 2015. The semiotic ecology of linguistic landscapes in rural Zambia. Journal of Sociolinguistics 19(5): 643-670. https://doi.org/10.1111/josl.12157 [ Links ]

Banda, F. and A. Peck. 2015. Diversity and contested social identities in multilingual and multicultural contexts of the University of the Western Cape, South Africa. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 37(6): 576-588. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2015.1106547 [ Links ]

Bangeni, B. and Kapp, R. 2011. A longitudinal study of students' negotiation of language, literacy and identity. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language 29(2): 197-207. https://doi.org/10.2989/16073614.2011.633366 [ Links ]

Bates, A.J. and M. Martin. 1980. The thematic content of graffiti as a nonreactive indicator of male and female attitudes. Journal of Sex Research 16(4): 300-315. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224498009551087 [ Links ]

Bakhtin, M. 1941. Rabelais and his world. (Translated by H. Iswolsk.) Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

Bakhtin, M.M. 1986. Speech genres and other late essays. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. [ Links ]

Bakhtin, M.M. 1981. Dialogic imagination: Four essays. (Translated by C. Emerson and M. Holquist.) Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. [ Links ]

Bhatia, V.K. 2007. Towards critical genre analysis. In V.K. Bhatia, J. Flowerdew and R. Jones (Eds.) Advances in Discourse Studies. London: Routledge. pp. 166-177. [ Links ]

Bolter, J.D. and R. Grusin. 2000. Remediation: Understanding new media. Cambridge: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Bourdieu, P. 1991. Language and symbolic power. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Bruner, E.M. and J.P. Kelso. 1980. Gender differences in graffiti: A semiotic perspective. Women's Studies International Quarterly 3(2/3): 239-252. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-0685(80)92260-5 [ Links ]

Chiorazzi, A. 2018. The Spirituality of Africa. Available online: https://hds.harvard.edu/news/2015/10/07/spirituality-africa (Accessed 11 November 2018)

Dundes, A. 1966. Here I sit: A study of American latrinalia. Kroeber Anthropological Society Papers 34: 91-105. [ Links ]

Dyers, C. and G. Davids. 2015. Post-modern "languagers": The effects of texting by university students on three South African languages. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 33(1): 21-30. https://doi.org/10.2989/16073614.2014.999994 [ Links ]

Eggins, S. and D. Slade. 1997. Analysing casual conversation. London: Cassel. [ Links ]

Fairclough, N. 1992. Discourse and social change. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Fairclough, N. 1993. Critical discourse analysis and the marketization of public discourse: The universities. Discourse and Society 4(2): 133-168. [ Links ]

Farr, J.H. and C.A. Gordon. 1975. A partial replication of Kinsey's graffiti study. The Journal of Sex Research 11: 158-162. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224497509550889 [ Links ]

Ferris, F.S. 2010. Appraisal, Identity and Gendered Discourse in Toilet Graffiti: A study in Transgressive Semiotics. Unpublished Master's thesis: University of the Western Cape. [ Links ]

Ferris, F.S. and F. Banda. 2015. "Poof! a'm heppily saving the Lord…": Multimodality and evaluative discourses in male toilet graffiti at the University of the Western Cape. Journal of African Identities 13(4): 243-261. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725843.2015.1087302 [ Links ]

Flores, L. and L. Sechrest. 1969. Homosexuality in the Philippines and the United States: The handwriting on the wall. The Journal of Social Psychology 79: 3-12. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1969.9922380 [ Links ]

Gonos, G., V. Mulkern and N. Poushinski. 1976. Anonymous expression: A structural view of graffiti. Journal of American folklore 89(351): 40-48. https://doi.org/10.2307/539545 [ Links ]

Green, J.A. 2003. The writing on the stall: Gender and graffiti. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 22(3): 282-296. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X03255380 [ Links ]

Hengst, J.A. and P.A. Prior. (Eds.) 2010. Exploring semiotic remediation as discourse practice. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Irvine, J. 2010. Semiotic remediation: Afterword. In P.A. Prior and J.A. Hengst. (Eds.) Exploring semiotic remediation as discourse practice. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 35-242. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230250628_10 [ Links ]

Johnstone, B. 2008. Discourse analysis. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. [ Links ]

Khaustov, M. 2014. Pragmalinguistic features of agony aunt columns in American, British and Russian newspapers. Young Scientist USA. Auburn, WA: Lulu Press. p. 71. [ Links ]

Kinsey, A., W. Pomeroy, C. Martin and P. Gebhard. 1953. Sexual behaviour in the human female. Philadelphia: Saunders. [ Links ]

Koller, V and S. Whiting. 2007. Dialogues in solitude: The discursive structures and social functions of male toilet graffiti. Working Paper Series No.126.

Kress, G. 2010. Multimodality: A social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Kristeva, J. 1986. Word, dialogue and novel. In T. Moi (Ed.) The Kristeva reader. Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 34-61. [ Links ]

Lalu, M. and N. Murray, eds. 2012. Becoming UWC: Reflections, Pathways and Unmaking Apartheid's Legacy. Cape Town: UWC Centre for Humanities Research. [ Links ]

Lefebvre, H. 1971. Everyday life in the modern world. (Translated by S. Rabinovitch.) New Brunswich, NJ: Transaction Publishers. [ Links ]

Lomas, H.D. 1973. Graffiti: Some observations and speculations. The Psychoanalytic Review 60: 71-89. [ Links ]

Mafofo, L and Banda, F. 2014. Accentuating institutional brands: A multimodal analysis of the homepages of selected South African universities. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 32(4): 417-432. https://doi.org/10.2989/16073614.2014.997068 [ Links ]

O'Halloran, K.L. 2011. Multimodal discourse analysis. In K. Hyland and B. Paltridge (Eds.) Companion to discourse analysis. London: Continuum. pp. 120-137. [ Links ]

Pennebaker, J.W. and D.Y. Sanders. 1976. American graffiti: Effects of authority and reactance arousal. Personality Social Psychology Bulletin 2: 264-267. https://doi.org/10.1177/014616727600200312 [ Links ]

Pennycook, A. 2009. Global Englishes and transcultural flows. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Sabău, E. and G. Niculescu. 2011. Some consideration about the didactic communication in physical education lesson. Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Braşov, Series VIII: Art Sport. Vol. 4(53) No. 1: 239-246. [ Links ]

Schouwenburg, H. 2012. "Het corps = kansloos". Towards a New Materialist University History? The Case of Student Graffiti at the Utrecht University Library. Available online: dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/253495. (Accessed 10 April 2013.)

Stocker, T.L., L.W. Dutcher, S.M. Hargrove and E.A. Cook. 1972. Social analysis of graffiti. Journal of American folklore 85(338): 356-366. https://doi.org/10.2307/539324 [ Links ]

Tagg, C. 2012. The discourse of text messaging: Analysis of SMS communication. London: Continuum. [ Links ]

Thurlow, C. and M. Poff. 2011. Text messaging. In S.C. Herring, D. Stein and T. Virtanen (Eds.) Handbook of the Pragmatics of CMC. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Vandenbussche, B. 2003. Remediation as medial transformation: Case studies of two dance performances by 'Commerce'. Available online: http://www.imageandnarrative.be/inarchive/mediumtheory/bertvandenbussche.htm (Accessed 4 October 2015.)