Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus (SPiL Plus)

versión On-line ISSN 2224-3380

versión impresa ISSN 1726-541X

SPiL plus (Online) vol.55 Stellenbosch 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.5842/55-0-776

ARTICLES

A pseudo-consecutive non-canonical serial verb construction in isiXhosa

Alexander Andrason

Department of African Languages, Stellenbosch University. E-mail: andrason@sun.ac.za

ABSTRACT

This snippet contributes to the study of less canonical Serial Verb Constructions (SVCs) of a multiclausal consecutive origin. The author demonstrates that the BUYA gram in isiXhosa constitutes an example of a pseudo-consecutive non-canonical SVC. Although BUYA complies with most features postulated for the prototype of a SVC, it also exhibits formal marking of consecutivisation. Nevertheless, as the gram does not comply with the various properties exhibited by consecutive patterns in isiXhosa, this marking is dummy.

Keywords: isiXhosa; serial verb construction; consecutivisation; prototype; cognitive linguistics

1. Background

According to the prototype approach, the category of Serial Verb Construction (SVC) is organized around an exemplar with which language-specific instantiations comply to a greater or lesser degree (Aikhenvald 2006, Dixon 2006; see also Crowley 2002).

The SVC prototype consists of two finite verbs that can occur independently outside an SVC; it exhibits a unitary TAM interpretation, polarity value, and argument structure; denotes a single event; exhibits a cohesive intonation pattern; functions as a single predicate and a single clause, which precludes any type of clause combining, in particular, subordination, complementization, (conjunctive) coordination, and consecutivisation (Muysken & Veenstra 1994, Aikhenvald 2006, Dixon 2006, Bisang 2009).

The varying degree of canonicity exhibited by language-specific SVCs reflects these constructions' advancement on the grammaticalisation path that connects multiclausal structures and SVCs. At an intermediate stage, less canonical SVCs preserve visible traces of their diachronic multiclausal origin: while in most aspects, they comply with the SVC prototype, they also exhibit formal features of multiclausality; specifically, morphological markers of clause-combining. Such markers are nevertheless dummy - the true multiclausal relationships being weakened or absent (Aikhenvald 2011, Andrason 2018).

2. Hypothesis

Coordinating and subordinating dummy elements in less canonical SVCs, and coordinating and subordinating sources of SVCs, are well attested to and comprehended (Aikhenvald 2006, 2011:21-22; see also Johannessen 1998:49-51). In contrast, dummy consecutivisers and the consecutive origin of SVCs are documented and understood to a lesser extent, even though the relationship between SVCs and consecutive structures has been noticed (Ameka 2006). Given the prototype theory of SVCs and their dynamic interpretation in terms of a grammaticalisation path (Aikhenvald 2006, 2011), consecutive patterns should generate SVCs like other multiclausal structures. Crucially, similar to pseudo-coordination and pseudo-subordination, markers of consecutivisation should be weakened to dummy elements during grammaticalisation towards SVCs. I will argue that isiXhosa attests to such pseudo-consecutive, non-canonical SVCs.

3. Evidence and discussion

In isiXhosa, one finds a gram(matical construction) composed of the V(erb) buya (V-1) and another verb (V-2) that together yield an iterative sense "(do something) again", as in example (1) below. This entire sequence, henceforth referred to as BUYA, is analysed in Bantu scholarship as one of the deficient-verb constructions (Du Plessis 1978, Du Plessis & Malinga 1978, Du Plessis & Visser 1992, Visser 2015, Poulos & Msimang 1998).1

BUYA complies with most features characteristic of the SVC prototype. V-1 and V-2 are inflected in finite categories - they are marked by noun-class Subject Agreement prefixes (e.g. nda- in (1)) and by TAM suffixes. V-1 appears in all TAM categories available in isiXhosa (Oosthuysen 2016:301), e.g. Remote Past (ndabuya lit. "I returned" in (1)), Present (ubuya lit. "I return" in (2)), and Future, composed of the Present of "come" and an Infinitive (uza kubuya lit. "I will return" in (3)). In contrast, V-2 is always inflected in the Consecutive (ndathetha "I talked" in (1)) or Subjunctive (anike "he gives" in (2)). Both verbs can occur on their own outside BUYA. In such cases, V-1 means "return" (ndibuya esikolweni "I return from school"), while V-2 exhibits its lexical value, analogous to that found in its uses with V‑1 buya. BUYA expresses a single event. Temporal (izolo "yesterday" in (1)) and spatial (esikolweni "at school" in (4)) modifiers obligatorily operate over the entire construction, not over V-1 or V-2 separately. The same holds true for adverbs of manner, means, or instrument (nge-Sunlight "with Sunlight soap" in (3)), and other types of adjuncts (nenkwenkwe "with the boy" in (1)). When interviewed, speakers perceive the expressed event as unitary (i.e. an action or activity occurring again), not as a sequence of two events or their overlapping occurrence. In these mono-event readings, the lexical type of event draws from the semantics of V-2 (e.g. talking in (1), giving in (2), washing in (3), singing in (4), and working in (5)), while V-1 communicates an aspectual nuance of repetition, translatable as "again" as in (1) - (5). BUYA exhibits a cohesive type of intonation, with no pause or bi-clausal contouring. As demonstrated by examples (1) - (5), the chain of V-1 and V-2 tends to be uninterrupted. Crucially, when moved out of its canonical preverbal position, the nominal subject occupies the construction-final position, rather than being placed between V-1 and V-2 (see uLandile in (5)). For that reason, in (6) - with the mono-event reading - only Kwabuya kwacula inkwenkwe is acceptable, while *Kwabuya inkwenkwe yacula (lit. gloss: 15.SA.PAST.return 9.boy 9.SA.CONS.sing) is ungrammatical. BUYA exhibits a single polarity and TAM value. Polarity and TAM have the entire construction as their scope, not only the separate components. Negation is expressed only once, appearing on V-1 (ababuyanga lit. "did not return" in (4)), although it operates over V-2 as well. BUYA assumes a unitary argument structure. As illustrated in all the sentences, the subject of V-1 and V-2 always coincide. The internal valency draws from the argument structure of V-2 and operates over the whole construction. If V-2 is intransitive, as in (1), (4) and (5), transitive, as in (3), or di-transitive, as in (2), BUYA is also - holistically - intransitive, transitive and di-transitive, respectively. The fact that V-1 only appears in the short forms of the perfect/recent-past and the present, as in (2), is consistent with the monoclausal interpretation of BUYA.

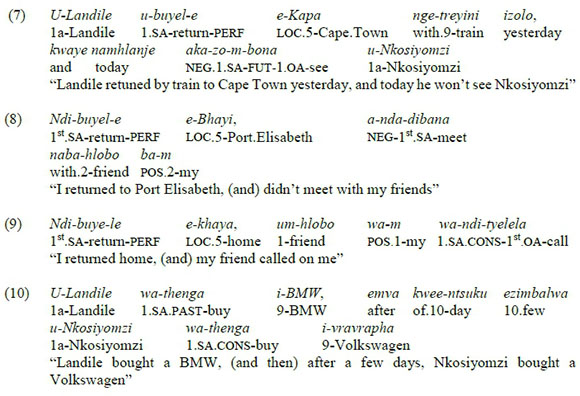

Despite the above features, BUYA is not a canonical SVC. Critically, it is marked for multiclausality, since V-2 appears in the Consecutive, as in (1), or its non-remote-time variant referred to as Subjunctive, as in (2) (this also implies that V-1 and V-2 need not be marked by the same TAM categories, contrary to the SVC prototype). Nevertheless, although formal consecutivisation is evident through the use of special Subject Agreement prefixes (nda- in (1), a- in (2) and wa in (5)) and verbal suffixes (e.g. -e in (2)), "logical" consecutivisation can be questioned. As demonstrated above, BUYA is obligatorily characterized by mono-eventhood, temporal and spatial identity, shared argument structure, unitary polarity and TAM interpretation (despite V-1 and V-2 hosting distinct TAM morphemes), mono-clausal phonology, and uninterrupted word order (including the position of the subject before V-1 or after V-2). All such features are either non-compulsory or ungrammatical in genuine consecutive patterns that are found in isiXhosa (Du Plessis 1978, Oosthuysen 2016).2 In isiXhosa, consecutive constructions regularly have a bi-event reading, as in (7), (8), (9) and (10); do not require the spatial and temporal identity of the events expressed by the conjuncts, as in (7) and (10); the conjoined verbs may govern their own internal, as in (10), and external arguments, as in (7), (9) and (10), as well as exhibit independent TAM readings, as in (7), and polarity values, as in (7) and (8); both conjoined verbs, including the second one, can host negative markers, as in (7) and (8), and can be separated by all types of arguments and adjuncts, as in (7) - (10); and, lastly, the conjuncts exhibit a phonological phrasing typical of multiclausal structures, as in (7) - (10). Given this contrast with authentic consecutive patterns, the consecutive marking of V-2 in the BUYA gram can be viewed as dummy - rather than genuine - thus constituting an example of pseudo-consecutivisation.3

4. Conclusion

This squib argued that the BUYA gram found in isiXhosa constitutes an example of a pseudo-consecutive non-canonical SVC. BUYA complies with most features postulated for the prototype of a SVC - the main exception being the presence of the consecutive marking on V-2. However, as BUYA fails to exhibit various properties that are characteristic of genuine consecutivisation, this marking is dummy.

Abbreviations

BUYA - the BUYA gram; CONS - consecutive; FUT - future; LOC - locative; NEG - negative/negation; OA - object agreement; PAST - the A "remote" past tense; PERF - perfect, "near" past tense; POS - possessive; PRES - present; SA - subject agreement; SUBJ - subjunctive; SVC - serial verb construction; V-1 and V-2 - the first and the second verb in the BUYA gram; 1(a), 2, 3, 9, 15 - noun classes.

References

Aikhenvald, A. 2006. Serial verb constructions in typological perspective. In A. Aikhenvald and R.M.W. Dixon (eds.) Serial Verb Constructions: A Cross-linguistic Typology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1-68. [ Links ]

Aikhenvald, A. 2011. Multi-verb constructions: Setting the scene. In A. Aikhenvald and P. Muysken (eds.) Multi-Verb Constructions: A View from the Americas. Leiden: Brill. pp. 1-26. [ Links ]

Ameka, F. 2006. Ewe serial verb constructions in their grammatical context. In A. Aikhenvald and R.M.W. Dixon (eds.) Serial Verb Constructions: A Cross-linguistic Typology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 124-143. [ Links ]

Andrason, A. 2018. From coordination to verbal serialization - the pójść (serial verb) construction in Polish. Research in Language 16(1): 19-46. [ Links ]

Andrason, A. 2016. The Coordinators i and z in Polish: A Cognitive-Typological Approach. PART 1. Lingua Posnaniensis 58(1): 7-24. [ Links ]

Bisang, W. 2009. Serial verb constructions. Language and Linguistics Compass 3(3): 792-814. [ Links ]

Crowley, T. 2002. Serial verb in Oceanic: A Descriptive typology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Dixon, R.M.W. 2006. Serial verb constructions: Conspectus and coda. In A. Aikhenvald and R.M.W. Dixon (eds.) Serial Verb Constructions: A Cross-linguistic Typology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 338-350. [ Links ]

Du Plessis, J.A. 1978. IsiXhosa 4. Goodwood: Oudiovista. [ Links ]

Du Plessis, J.A. and M.W. Visser. 1992. Xhosa syntax. Pretoria: Via Afrika. [ Links ]

Du Plessis, J.A. and R. Malinga. 1978. IsiXhosa 3. Goodwood: Oudiovista. [ Links ]

Haspelmath, M. 2004. Coordinating constructions: An overview. In M. Haspelmath (ed.) Coordinating Construction. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. pp. 1-40. [ Links ]

Haspelmath, M. 2007. Coordination. In T. Shopen (ed.) Language Typology and Syntactic Description, Vol. II: Complex Constructions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1-51. [ Links ]

Johannessen, J.B. 1998. Coordination. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Muysken, P. and T. Veenstra. 1994. Serial verbs. In J. Arends, P. Muysken, and N. Smith (eds.) Pidgins and Creoles. An introduction. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. pp. 289-301. [ Links ]

Oosthuysen, J. C. 2016. The Grammar of isiXhosa. Stellenbosch: Sun Media. [ Links ]

Poulos, G. and C.T. Msimang. 1998. A Linguistic Analysis of Zulu. Cape Town: Via Afrika. [ Links ]

Visser, M.W. 2015. Xhosa 214, 244. Syntax. Stellenbosch: University of Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

1 In isiXhosa, there is a large set of such bi-verbal structures. Apart from buya, other examples of V-1 are: andula "begin"; fana/fumana "just/only"; hle "suddenly"; khawuleza "quickly"; khe "once/never"; phantse "almost"; qala "first/begin"; qokela "again"; shiya "greatly"; suka "just/ then"; tshetsha "quickly"; ye "just/without reason"; ze "must / [negative] "never"; zinga "constantly" (Visser 2015). In all such constructions, V-2 specifies the semantic type of an action, while V-1 contributes to its aspectual or modal interpretation (ibid.).

2 These features are also incompatible with a crosslinguistic prototype of conjunctive coordination (see Haspelmath 2004 and Andrason 2016). They are, in contrast, common in pseudo-coordinated structures (Johannessen 1998:49-51).

3 Overall, sentences like ndabuya ndathetha may, at least in principle, have two interpretations: a mono-event interpretation ("I talked again"; i.e. as the BUYA gram) and a bi-event interpretation ("I returned and spoke"; i.e. as a genuine consecutive pattern). In many cases, due to a broadly understood context, a given construction built around the verb buya can be disambiguated, such that only one reading is acceptable. Crucially, certain syntactic operations are ungrammatical in genuine consecutive constructions, while others are excluded from the SVC BUYA. See, for instance, (4) where a bi-event interpretation "The children did not return and sang at school" is implausible (as nearly nonsensical), and (9) where a mono-event reading "My friend called me again" is impossible (as the subject arguments of V-1 and V-2 do not coincide).