Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus (SPiL Plus)

versão On-line ISSN 2224-3380

versão impressa ISSN 1726-541X

SPiL plus (Online) vol.51 Stellenbosch 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.5774/51-0-700

ARTICLES

Youth discourse in multilingual Mauritius: The pragmatic significance of swearing in multiple languages1

Tejshree Auckle

Department of English Studies, University of Mauritius, Mauritius E-mail: t.auckle@uom.ac.mu

ABSTRACT

Drawing from Dewaele (2010, 2013), this paper seeks to analyse the socio-pragmatics of swearing in face-to-face multilingual conversational encounters and argues that the conversational locus (Auer 1984) of playfulness favours, among others, the co-occurrence of slang and code-switching (CS). Defined by Eble (1996: 11) as an "ever changing set of colloquial words and phrases that speakers use to establish or reinforce social identity or cohesiveness within a group or with a trend or fashion in society at large", slang is more often than not associated with the speech of youngsters seeking to set up the linguistic boundaries of their in-group. Viewed as a global phenomenon, which is transposed differently in local contexts by young people hailing from different social, cultural and linguistic backgrounds - including, as Zimmerman (2009: 121) notes, dialectal and sociolectal backgrounds - it acts as a marker of symbolic "desire and consciousness of youth alterity". Such a situation can be endowed with further sociolinguistic complexity in multilingual situations such as Mauritius, where the wide range of available languages endows speakers with an equally fertile repertoire of swear words derived from diverse sources.

In keeping with the above, this paper focuses on a series of multi-party recordings carried out between October 2011 and March 2012 and analyses the ways in which the usage of swear words in multilingual contexts can act not only as a reflection of speakers' communicative competence, but also as an externalisation of their dynamism and creativity. The use of swear words in conjunction with CS is, thus, viewed as being a pragmatically consequential conversational act. Such linguistic versatility appears to be indexical of a reflexive position that youngsters orient themselves to by allowing their linguistic output to be seen as a performance, "involv[ing] on the part of the performer an assumption of accountability to an audience for the way in which communication is carried out, above and beyond its referential content" (Bauman 1975: 293).

Key words: code-switching, swear words, multilingualism, Mauritius

1. Introduction

An insular island located in the southern part of the Indian Ocean, Mauritius is known mainly for its tropical climate, beautiful lagoons and sandy beaches. Over the past several decades, linguistic interest in the island has tended to focus quasi-exclusively on issues pertaining to Mauritian Creole (MC, cf. the seminal work of Baker 1972). In contrast, multilingualism, though a staple of daily conversational encounters, remains understudied. This paper, therefore, aims to bridge the aforementioned theoretical and empirical gap by focusing on the issue of code selection during instances of swearing in face-to-face interactional sequences. Researchers such as Dewaele (2010) argue that, contrary to monolingual settings where the swear word is, more often, derived from one of the corresponding dialects of the language, in multilingual ones, speakers have the option of choosing a swear word from their multilingual repertoire. The interactional phenomenon of swearing, thus, becomes a pragmatically consequential act allowing speakers to endow their conversations with a hint of playfulness (cf. Auer 1984). In the light of the above, this study aims to answer the following research questions:

• In which language(s) do multilingual Mauritian speakers swear, operating within what Auer (1984) labels as the conversational locus of playfulness?

• Secondly, what is the pragmatic significance of selecting a particular language at a given point in a face-to-face interaction?

The issue of using multiple languages while swearing is one that remains topical in contemporary Mauritius. Indeed, unlike many other postcolonial nations using the post-independence period to come up with a language policy that is both uniquely their own and breaks away from the decisions made during the colonial era (cf. Blommaert's 1996 work on language policy in Tanzania), Mauritius has opted for what Schiffman (1995) labels as a 'covert' language policy. In contrast to Tanzania, for instance, where language policies may refer to a formalised system of rules and regulations that govern the use of languages in primarily the public domain, Mauritius makes no explicit, de jure, provision for the use of specific languages in formal contexts (Mooneeram 2009). Similar to other countries, which have opted for a covert language policy, Mauritius relies on inferences derived from tangentially relevant sub-policies and constitutional provisos (Carpooran 2003).

In fact, following the independence of the island from the United Kingdom, only one explicit reference is made to language in the Constitution voted by the then Legislative Assembly (Constitution of Mauritius 1968: ch5(49)). It states that "[t]he official language of the Assembly shall be English but any member may address the chair in French" (ibid). It also adds that members democratically elected to serve in the Mauritian parliament must ensure that they have a "degree of proficiency sufficient to enable [them] to take part in the proceedings of the Assembly". The recommendation to use English, and to an extent French, in formal settings is one that was also extended to the legal domain - where until 1989, it was mistakenly assumed that English was the official language of both the parliament and the island as a whole (Carpooran 2003). Consequently, it was compulsory for all testimonies to be provided in English (Lallah 2001). It took Judge R. Ahnee's landmark ruling in L 'affaire Kramutally ('The Kramutally Case') for Mauritian citizens to realise that the island had no official language (ibid)2. Further compounding this issue was Judge Ahnee's recommendation that, given the absence of any official language policy document, the hegemony of English - and by extension, French - could be legitimately contested (Lallah 2001; Carpooran 2003; Hein 2014). His ruling has had far-reaching consequences, with non-governmental organisations (NGOs) such as Ledikasyon pu Travayer lobbying successive governments for the amendment of the 1968 Constitution in favour of MC-friendly laws. These laws would allow for the language, which is the mother tongue of 90% of Mauritians today (Statistics Mauritius 2011), also to be used in parliament (Carpooran 2005). This request has been repeatedly denied by respective heads of government on the basis that parliamentarians might view the introduction of MC as an indication of a relaxation of the overall norms of conduct adopted in the parliament and might end up using the language only to swear at the opponents (Le Mauricien 2013).

As the above argument indicates, despite the successful introduction of MC in primary schools in 2011, successive prime ministers remain apprehensive regarding the potentially disruptive impact of MC (Le Mauricien 2013). English, in contrast, is believed to have an inhibitive effect resulting in enhanced levels of conversational politeness. The interactional act of swearing and the language in which such swearing occurs is, therefore, one which the Government of Mauritius appears to take very seriously. As a matter of fact, the Prime Minister's Question Time (PMQT) session held on 23 April 2013 was entirely devoted to the hypothetical use of MC swear words in the National Assembly should the language be introduced in the parliament (Le Mauricien 2013). Expressing his disapproval of this suggestion, then Prime Minister Navin Ramgoolam argued that the adoption of MC would result in politicians behaving in an "unruly" manner. This prompted Steve Obeegadoo, member of the opposition party to draw parliament's attention to the fact that "[i]mproper language in the House is not always in Creole. The word "shit" is not Creole" (Le Mauricien 2013). The above debate gives rise to an interesting linguistic conundrum: in a multilingual island where language alternation between French, English, MC and other languages is common, what is the language that would ensure maximum propriety on the part of interlocutors? Conversely, are switches to MC genuinely more likely to coincide with heightened instances of swearing? So far, the answers to these questions have remained elusive and have contributed to the ostracism of MC from the Mauritian parliament.

However, this study, far from being an exhaustive one, only aims to provide a snapshot of the language choices made by conversationalists as they juggle between English, French, MC, Mauritian Bhojpuri (MB) and other Asian languages such as Hindi. Indeed, it should be kept in mind that the debates carried out in the National Assembly pitting MC against English and French are indicative of a far more complex reality: given the colonial history of the island, Mauritian speakers have the freedom to choose from more than just three languages to fulfil their interactional needs. Eriksen (1999: 14) attributes this "mongrel" culture existing in Mauritius to historical serendipity, which resulted in the cohabitation of people from different linguistic and cultural backgrounds, eventually culminating in the multilingual melting pot that is contemporary Mauritius.

Discovered by Arab and Portuguese sailors in the early 16th century, the first human settlement of the island was by the Dutch (1598-1710) who, in deference to the Dutch Prince Maurits van Nassau, named the island Mauritius (Correia 2003). Following the departure of the Dutch, the island was taken over by the French (1710-1810) who, during their millennial-long rule of the country, used French as the sole language of interaction in all domains of colonial administration (Miles 2000). Furthermore, in contrast to the Dutch, who opted against the occupation of the island, the French transformed Mauritius into a thriving sugar-producing plantation economy (Kalla 1984). Renaming the island to Ile de France, the French administration was also responsible for the arrival of "successive convoys of slaves from Mozambique and elsewhere in East Africa (40-45 percent) and from Madagascar (30-35 percent). [...] Small numbers of slaves were transported to the island from Seychelles, Cape Verde, Rio de Janeiro, and West Africa. [...] Benin has also been suggested as a source of Mauritian slaves" (Miles 1999: 213). One of the immediate consequences of such a high degree of diversity in slave origins was the genesis of MC, which evolved over the years from a highly valued lingua franca to the mother tongue of a large majority of the population (Bissoonauth 2011). The year 1810 marked a turning point in the linguistic history of Mauritius. Vanquished by the British (1810-1968) in the Battle of Grand Port, the French ceded all geopolitical rights to the island (Miles 2000). However, their defeat at the hands of the British did not deter them from imposing certain conditions upon their successors: the terms of the 1810 Act of Capitulation appear to have been, quite unexpectedly, dictated by the French (ibid). First of all, although members of the French colonial administration were forced to leave the island, the early French settlers were not required to relinquish their rights over their respective plantations (Kalla 1984). As a result, the outgoing French administration sought to secure their cultural and linguistic autonomy by ensuring that French culture, and by extension the French language, were given precedence over English. Miles (2000: 217) elaborates:

The 1814 Treaty of Paris reinforced this understanding. Implicitly, the French language was preserved. Mauritius thus continued to be a French and French Creole speaking society under the relatively unintrusive umbrella of British sovereignty. The one significant exception to Anglo-Saxon aloofness was the judiciary. In 1845 it was decreed that English would become the language of the higher courts.

One immediate consequence of a British-style judiciary was the abolition of firstly the slave trade and eventually that of the institution of slavery itself.

The resulting shortage in manpower was addressed through the large-scale import of indentured labour from India. Mauritian society, thus, underwent a dramatic demographic and most importantly, linguistic change. The arrival of the Indian indentured labourers marked the transition of the country from a trilingual (French, MC and English) speech community to one which was effectively multilingual (Kalla 1984). Bhojpuri, Marathi, Tamil, Telugu, and Gujarati were now added to the Mauritian linguistic mosaic along with Hindi and Urdu, which were especially valued in liturgical contexts (Miles 2000). The subsequent arrival of Chinese traders from mainland China resulted in the insertion of Hakka Chinese and Cantonese into the Mauritian multilingual matrix (Rajah-Carrim 2005). Eventually, after 158 years of British colonial rule, when Mauritius gained independence from the United Kingdom, there was already a well-established "four-part harmony" of Mauritian languages with MC as "the uncontested lingua franca; French as the inherited language of social and cultural prestige; English as the language of education, law, public administration and to a degree commerce; and [a] panoply of Indian and Asian languages" (Miles 2000: 217).

In a conversational context where multilingualism has been such an integral part of the development of the social, cultural and linguistic identity of the nation, it is to be expected that interactional phenomena such as language alternation would prove to be pragmatically loaded (cf. Auckle and Barnes 2011). Along similar lines, though understudied in the Mauritian context, the interactional act of swearing is also one which is endowed with pragmatic consequentiality. The choice of MC, French, English or any other Indian or Asian language is bound to bring to the fore the ability of a competent multilingual to resourcefully capitalise upon the opportunities his/her linguistic repertoire provides. As the following subsection will further illustrate, such an ability is not limited solely to the Mauritian context.

2. Use of swear words in multilingual contexts

Defined by Eble (1996: 11) as an "ever changing set of colloquial words and phrases that speakers use to establish or reinforce social identity or cohesiveness within a group or with a trend or fashion in society at large", slang, of which swear words are a subset, is more often than not, associated with the speech of youngsters seeking to reify the linguistic boundaries of their nascent in-group. Building on the above perspective, Zimmerman (2009) argues that far from being a static phenomenon, the construction of youth identities needs to be seen as a dynamic performance that is often carried out in situ during face-to-face interactions. Viewed as a global phenomenon that is transposed differently in different local contexts by young people hailing from different social, cultural and linguistic backgrounds - including, as Zimmerman (2009: 121) notes, dialectal and sociolectal backgrounds - slang acts as a marker of symbolic "desire and consciousness of youth alterity". Focusing on what he terms as 'youngspeak', Zimmerman (2009: 122) lists three subcategories within which varieties of speech can be categorised, namely diatopic (varieties related to specific regions), diastratic (varieties associated with particular social groups or classes, sociolects) and diaphasic (varieties sensitive to shifts in domains or functions). Calling for a diatopic and diaphasic instead of a diastratic focus on youngspeak, Zimmerman (2009) argues that the anti-normative bent in youngsters' behaviour makes them unsuitable to be simplistically pigeonholed into restrictive social categories. Instead, he believes that youngsters' wish to index both a geographical sense of belonging and a sensitivity to changes in situations may result in modifications in styles and registers. Therefore, the use of slang items needs to be viewed within this two-tier paradigm of diastratic and diaphasic variation.

Such a situation can be endowed with further sociolinguistic complexity in multilingual situations such as Mauritius, where the wide range of available languages endows speakers with an equally fertile repertoire of swear words derived from myriad sources. Focusing on the use of swear words in multilingual contexts, Drescher (2000) argues that far from acting as simple interjections capable of expressing the emotions of speakers, swear words are, in fact, versatile discourse units that can serve different pragmatic functions. For instance, they may indicate a shift in the participant constellation of an interaction by being deliberately offensive and thus precipitating the departure of one speaker from a multiparty conversation (Drescher 2000). Acting as discourse markers, swear words can also indicate turn handover at Transition Relevance Points (TRPs) or act as floor seizure mechanisms resulting in the termination of a speaker's turn in the conversation (Schegloff 2007). Where in monolingual contexts, swear words can serve to affirm group membership to a particular age group, in multilingual ones, they allow speakers within the same age group to divide themselves further into smaller units of interaction by using specific swear words to draw the boundaries between their budding in-group and the out-group (Léard 1997).

This is evidenced in the case of swear words used by speakers in Quebec and mainland France. Although the varieties of French in both speech communities are mutually intelligible, the differing patterns of settlement in mainland France and Quebec as well as the co-existence of French with English in Canada have given rise to a semantic category of swear words that would be considered pragmatically unmarked in France (Léard 1997). For instance, Léard (1997) noticed that while words with a religious connotation such as hostie de voisin ('damn neighbour') were considered to be fairly offensive in Quebec, this was not the case in France where they would be deemed merely unflattering. Although the examples provided by Léard (1997) do not explicitly refer to interferences from English, it can possibly be inferred that the evolution of French alongside other languages in Canada might have resulted in an increase in pragmatic value for swear words derived from a particular language. Similar to the Mauritian context where the use of swear words is popularly believed to coincide with the selection of MC as the matrix language for an interaction, Léard (1997) indicates that the choice of code may be affected by the perceived social, psychological and emotional resonance that these might have for a particular group of speakers. For speakers of French in Quebec, the use of a distinct category of swear words marks them as being both young and loyal to the speech community within which they grew up. Therefore, swear words act as a form of powerful we-code allowing them to construct and maintain the boundaries of their in-group vis-á-vis speakers of mainland France.

Concurring with the above perspective, in his blog post for the language blog Verbal Identity, Dewaele (2015) asserts that "[w]hat matters when swearing is to know do it 'appropriately', in other words, [to] know the context in which certain swearwords and expressions may be tolerated or appreciated." He gives the example of foreigners who might inadvertently offend members from their host country by using swear words from their L2. Since their accent already marks them as being foreign, the act of swearing in the L2 may be deemed as being as disrespectful as "making fun of the King, Queen or Head of State" (ibid). For them, even though the use of swear words from the L2 might appear to be an innocuous act capable of giving vent to their feelings, these are perceived to be inappropriate and are consequently, frowned upon by their addressees. Accordingly, swear words appear to be caught in a double-bind situation: they are dependent, not only on the connotations that they evoke for the speaker but also on the interpretation that addressees impose on them when they decode the meaning of a construction, which involves the use of swear words from multiple languages (Dewaele 2015).

However, not all bi- or multilinguals have to be sensitive to the semantic and pragmatic demands of a home and a host community. In the case of multilinguals who might have a relatively stable level of proficiency in most, if not all, the languages that form part of their mental repertoire, opting for one language over the other is a decision that lacks the social sensitivity required from immigrants to another host community. Instead, the selection of a code remains an individual decision that reflects their own, and possibly their addressees' attitudes towards specific languages. Santiago-Rivera and Altarriba (2002) agree with the above perspective and argue that many speakers may purposefully opt for languages that they learnt earlier in life because these have a stronger emotional hold on them compared to languages learned in later stages in life, which are devoid of the same degree of emotional resonance. Javier and Marcos (1989) extend this argument further and assert that swear words derived from languages learnt in later stages of life might dominate in situations where speakers need to distance themselves from either the content or the co-conversationalists taking part in an interaction. In this case, switching to a language that they might not feel as comfortable in or be emotionally connected with allows them the possibility of either rescinding their conversational turn or may, in some cases, lead to the total breakdown of a conversational unit by making other addressees feel uncomfortable (Javier and Marcos 1989; Bond and Lai 1986).

Along similar lines, Harris, Aycicegi and Gleason (2003) and Harris (2004) suggest that multilinguals report feeling more emotionally connected to emotions expressed through swear words derived from languages that they either learnt earlier in life or feel more comfortable in. In these cases, although the speakers are fully capable of producing a syntactically correct sentence in languages mastered at different stages of their life, they appear to choose their verbal performance based on the pragmatic options offered to them by languages that allow them to display a degree of personal involvement. Dewaele (2004: 207-208) further quotes the reaction of Canadian author Nancy Huston (English L1) who, when asked to name the languages that she uses to swear, responded:

To take my case, if I am involved in an intellectual conversation, an interview, a colloquium or any linguistic situation that draws on concepts and categories learned as an adult, I feel most at ease in French. On the other hand, if I want to go mad, let myself go, swear, sing, yell, be moved by the pure pleasure of speech, I do all that in English.

The above example, though anecdotal, supports existing theoretical and empirical evidence regarding the fact that multilinguals feel empowered in choosing the codes in which they can swear, depending on their interactional needs and, in some cases, depending on the perceived approval or disapproval of their addressees.

The above considerations apply in the case of youngsters too. Indeed, sociolinguistic studies in the field of swearing have repeatedly shown a clear preference by youngsters for the use of swear words (Rayson, Leech and Hodges 1997). For instance, a study carried out by Rayson et al. (1997) revealed that contrary to expectations, social class appeared to have no impact on the number of swear words used by speakers. Carrying out a frequency analysis of a list of vocabulary items in the conversational section of the British National Corpus, they observed that incidences of specified swear words were far higher in speech samples from both males and females who were under 35. Stenstrom (1995) concurs with these findings and drawing from The Bergen Corpus of London Teenager Language, also highlights the extended use of swearing by teenagers in contrast to their middle-aged counterparts. Gender was seen to have a negligible impact on the proportion of swear words used by these teenagers, with males and females using a quasi-equal number of swear words. A similar observation is made by Bayyard and Krishnayya (2001) whose analysis of swear words used by a group of youngsters at New Zealand University found that though gender affected the type of swear words used by speakers, it did not have an inhibitive effect on the act of swearing itself.

Elaborating further on the use of swear words by youngsters, Allan and Burridge (2006) argue that this is an interactional act that benefits from the multilingual abilities of speakers by allowing them to express a broader range of meanings and emotions through the act of opting for one code instead of the other. They mention that just like monolingual speakers have the option of selecting colloquial expressions such as 'croak', 'snuff it' and 'peg out' instead of the more formal 'die' or 'pass away', multilingual ones have the opportunity of using words from multiple languages and the diverse dialects that may be associated with these languages (Allan and Burridge 2006: 241). In fact, youngsters are as sensitive as older speakers to the importance of using one language over the other for swearing. Similar to research carried out on older multilingual speakers (Dewaele 2004), teenagers and young adults are also more likely to have recourse to the language that they are most comfortable in while swearing. This is because, as Allan and Burridge (2006) argue, as children, all multilingual speakers do not acquire just the languages that they are exposed to. In fact, they may also connect emotionally with them. In contrast, swear words acquired in other languages post-childhood, might lack the same cultural imprint and have different connotations, making them more suitable for particular interactional needs. In a similar vein, commenting on her own frequent acts of code-switching (CS) from Polish to English as a youngster, Hoffman (1989: 146) points out that although English was the matrix language of most of her interactions, she would use both Polish and English while swearing. She believed that Polish allowed her to express her "romantic self while English was a means for her to remain pragmatic and rational. In other words, using swear words in English, even during emotionally-charged arguments, allowed her to maintain a perceived upper-hand in the interaction whereas due to the emotional resonance that Polish had for her, she was unable to remain as level-headed when conversing in Polish.

Pavlenko (2006) uses the Bakhtinian concept of double-voicing3 to explain the verbal performance of multilingual youngsters. She believes that CS allows youngsters to creatively inject humour, sarcasm, irony and other forms of subtle emotional micro-expressions into language by using a swear word in accordance with shifting conversational contexts. According to her, a change in language may, thus, be accompanied by further changes in verbal or nonverbal behaviour which "may be interpreted differently by people who draw on different discourses of bi/multilingualism and the self (Pavlenko 2006: 27). In other words, swearing is not simply an idiosyncratic process that serves the interactional needs of the speaker, but depending on the relationship between speaker(s) and addressee(s), meaning may also become multi-layered. Through the interactional act of swearing, CS becomes both initiative and responsive. On the one hand, it indicates to co-participants that something other than referential meaning is being conveyed. On the other hand, it also has the ability to take on board the interpretations of other co-conversationalists and to negotiate for a shared platform of understanding.

In essence, as this section has tried to illustrate, language choice is crucial to multilingual youths when they utilise swear words during face-to-face multilingual encounters. While the psycholinguistic or neurolinguistic impact of swearing in one language over the other is beyond the scope of this paper, an attempt will be made to explain the pragmatic consequences of selecting one language over the other during conversational exchanges between a group of young, multilingual informants.

3. Methodology

3.1 Sample

This paper reports on data collected between October 2011 and March 2012 for the purposes of a doctoral project investigating the different types of language alternation phenomena in multilingual Mauritius today. Emphasis was eventually placed on the conversational locus of playfulness (Auer 1984) of which swearing is part. Participants were recruited via the friend-of-a-friend approach and through social media sites such as Facebook. As the administrator of the Facebook group Langaz KreolMorisyen (Mauritian Creole Language), the interviewer was able to post messages on discussion forums and spread the word to a wide network of receptive group members. This is an active group that uses all the features made available by Facebook. Since this is an open group, other users of Facebook can search for and join it and messages can be posted both on the wall and on the discussion forum of the group. Thus, this group remains the electronic meeting point of aficionados of the MC language and culture. The recent move to a new format enforced by the Facebook team led to the unfortunate loss of quite a few members. However, in October 2011, the starting point of the data collection process, the group boasted of a total of roughly 900 members.

In addition, similar messages requesting for interested participants to get in touch were posted on the personal Facebook page of the interviewer. These, coupled with relevant messages posted on the Facebook profile of the interviewer's friends, helped to catch the interest of potential volunteers. Thus, word-of-mouth through the judicious exploitation of the friendship and kinship networks of friends and subsequently their acquaintances proved to be quite beneficial to the project since it allowed the group to grab the conversational limelight for a while, earning it much-needed exposure. In total, 40 informants, aged between 16 and 23 and split into groups of five, eventually took part in the recording process. A tabular representation (see Table 1) of the sample frame of this project is provided below:

As the above table indicates, each group of informants had a team leader who was responsible for liaising with the interviewer regarding the time and venue of meetings. Spanning a period of roughly six months, a total of between 14 to 20 hours of data per group were collected, yielding an overall spoken corpus of about 150 hours. Multiparty conversations were preferred because they allow informants the safety of interacting within a circle of close friends and the additional bonus of being able to contribute to the analysis carried out by the researcher.

3.2 Methods

Duranti (1997: 118) convincingly argues that speakers do not "invent social behaviour, language included, out of the blue". Patterns of linguistic variation are only transposed from the more private domain of friendship to the more public one of audio-recording. Psathas (1995: 2) concurs with Duranti (1997) and contends that locally salient conversational practices are easily highlighted through recordings of multiparty talk since such social interactions are often symbolically "meaningful for those who produce them". Consequently, the aim of the interviewer is to capture on tape the respondents' normal, everyday conversations while at the same time, ensuring that their interpretation of their sequential contribution to the talk-in interaction is given priority during the analysis phase of the project. According to Auer (1984: 6) privileging the participants' "interpretational leeway" instead of that of the analyst constitutes one of the methodological lynchpins of Conversation Analysis (CA). Similarly, this study also adopted this basic premise of the CA enterprise and sought not only to record instances of language alternation, but also to ensure the maintenance of naturalistic settings such as multiparty interactions so as not to alienate the participants from the subsequent data analysis phase of the project.

The focus on swear words was suggested to the interviewer by the informants themselves during the data collection phase of this project. Indeed, while trying to break the ice between the interviewer and the prospective interviewees and in an attempt to earn their trust, the interviewer found that she regularly had to make similar language choices as those made by her target group. For instance, many of the young adults sampled in this study were initially reluctant to be audio-recorded due to their tendency to slip into extended episodes of swearing. In the words of one of the informants:

Speaker 1: Be to pou kon tou nou sekre. Fer atansyon zourer.

But you will learn all our secrets. Beware of swear words.

As the short excerpt provided above highlights, the concern of the interviewee was two-fold. Firstly, he was apprehensive about sharing information of an exceedingly personal nature on tape; secondly, he was worried about the reaction of the interviewer when swear words would occasionally be used by the participants. Consequently, it was up to the interviewer to anticipate any possible feelings of awkwardness by not reacting negatively to the use of swear words in her presence and by occasionally using a few of them herself. Sensitivity to such discursive practices was undeniably rewarding since none of the participants selected to take part in this study backed out of the recording process and even though the number of swear words recorded were not as high in number as the informants led the interviewer to expect, they did manage to shed light on the interactional practices adopted by the participants taking part in this study. The participants in this study were all native speakers of MC and were also conversant with MB, Hindi/Urdu, English and French.

In the light of the above, the selection and analysis of extracts from this medium-sized corpus of data regularly took on board the input of the participants themselves. Therefore, the findings provided in the following subsections present the concatenated view of the analyst as nonparticipant observer and the participants whose opinions were sought and incorporated into the analysis.

4. Findings

The following subsections provide an insight into the ways in which CS and the insertion of sequences of swear words are creatively embedded into the routine face-to-face interactions of the informants taking part in this study. For ease of reference, the following table presents a summary of the different font styles associated with each language operating in the current multilingual matrix:

Although the current dataset consists of further examples of similar kinds of linguistic behaviour, this paper explores a few prototypical shapes that swearing-related CS took in this study.

4.1 Swearing in MC

Swear words in MC were often used as framing devices by contextualising an alternation in language and consequently, bringing about a shift in the overall meaning of the conversation (Goffman 1981). Similar to films where attention can be drawn to a particular activity by "freeze-fram[ing]" a particular moment, in conversation, frames allow speakers to indicate certain elements of an interaction that they might wish their addressee to focus on (Allan 2003: 337). Therefore, by extension framing devices can be defined as being the interactional devices used by speakers to achieve this 'freeze-framing' effect (ibid). Such devices can take the form of interjections or as in the case of this study, swear words. Extract 1 provides an illustration for the above claims4:

In the above excerpt, the group is discussing the various technical problems encountered while trying to play a newly-acquired video game. Unfortunately, despite their repeated entreaties to one of their friends who happens to be more knowledgeable about computers, the expected help is not forthcoming. In fact, Speaker 32 keeps finding excuses to delay the troubleshooting process, eventually framing his procrastination through a switch to the French temporal marker bientôt. Unfortunately, this shift in language in a predominantly MC-speaking segment does not go down too well with his co-participants, with Speaker 31 responding with a swear word while speakers 33 and 34 express their explicit approval towards his recourse to slang through the overlapping segment of talk-in interaction.

It is particularly noteworthy that the shift to a swear word is preceded by the reduplication of the French word bientôt by Speaker 31. As a rule, reduplication, that is the recurrence of the same morphological unit twice within the same conversational sequence, occurs for emphatic purposes and is considered as one of the defining characteristics of both pidgins and creoles (Bakker and Parkvall, 2005). As far as the above extract is concerned, a contrast can be established between the rejoinders of Speakers 31 and 32. The former's contribution can be unequivocally qualified as being in French and is a strategic conversational move adopted by the speaker as he tries to gain the upper hand over his co-conversationalists by framing his procrastination in a more formal code. However, this attempt at manipulating the power dynamics of the conversation eventually fails since Speaker 32 cleverly sidesteps the issue by using reduplication in order to integrate the French segment into MC and bring the footing of the conversation back to that of camaraderie. At this point, reference can also be made to Myers-Scotton's (1983) notion of the Rights and Obligations (RO) set. As she argues, all conversations hinge on either the maintenance or the disruption of an expected set of language alternation behaviour. In the case of Extract 1, Speaker 31 clearly attempts to move away from an existing RO set - an action which meets with the apparent disapproval of Speaker 32 who, in turn, steers the conversation back to its original interactional code.

That Speaker 32 understands the attempt of his co-interactant at asserting his dominance and clearly disapproves of it is shown through his use of slang as a derogatory address term as a precursor to his demand to the latter to provide plausible reasons for his delay in responding to the group's request. In fact, Speakers 33 and 34's overlapping segment of minimal responses plainly convey their endorsement of the slang item as a harsh admonishment towards their friend, a point of convergence in an otherwise conflicting interactional segment. Consequently, Speaker 31's change in attitude and promptness in rectifying his errors by providing them with the expected technical support comes as no surprise: it, powerfully, reflects his adherence to their in-group and his understanding of their shared slang vocabulary, which eventually acts as a marker of their communal identity. Not only does it serve to mark them out as being cool, it also effectively helps them to sort out their discussions by using such items to express feelings of happiness, pride or in this case, displeasure.

4.2 Swearing in MC and MB

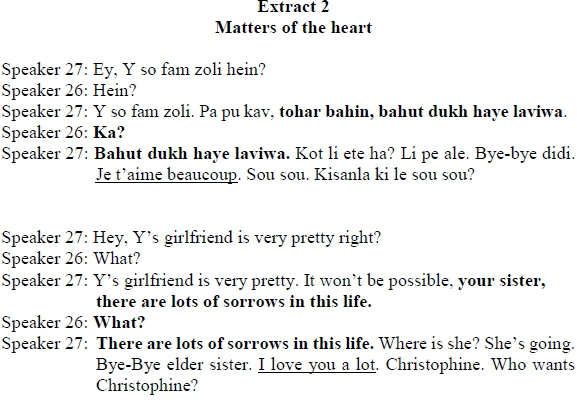

Far from being restricted to only male speech (as in the case of Extract 1), slang usage was a popular feature among all interactants, even those operating in female-only groups. Extract 2 exemplifies this observation:

The conversation, in the above extract, centres upon the love life of close friends and relatives of Speakers 26 and 27. Openly appreciative of the attractive girlfriend of one of their mutual friends, Speaker 27 switches to Bhojpuri in order to express her sympathy to her co-conversationalist regarding the slim chances of the latter's sister to date Y. Unwilling to acknowledge this fact, speaker 26 pretends not to hear her and responds twice with the interrogative marker 'what', firstly in MC (hein) and secondly in Bhojpuri (ka) before finally making her disapproval felt more forcefully by leaving the room. Unfazed by her obvious displeasure, Speaker 26 still makes use of the kinship term didi (elder sister) as an endearment before switching to French to declare her love for her friend. Both strategies seem to function as mitigating devices to attenuate the emotional blow that she has dealt to her friend. Her awareness of the crush that Speaker 26's sister has on Y, coupled with the loyalty that is expected, prompt her to assuage the perceived harshness of her comment through an unambiguous avowal of her enduring love and appreciation for her friend by switching to a more formal code. However, the failure of her efforts and the eventual departure of Speaker 26 give rise to a cheekier response as she shifts back to MC and asks the latter whether she likes eating sou sou (Christophine).

Christophine, also written as Christophene, is known as chou chou in Mauritius. A tropical vine squash that is also widely used in Caribbean cuisine, the Christophine resembles a large green pear and has a fibrous texture (Ganeshram 2005). Both the vine on which it is grown, as well as the fruit are edible. Due to its mild taste, it is often served as a side dish along with spicier concoctions such as curries (ibid). Known in the scientific community by the Latin name sechium edule, it is part of the staple diet of many tropical and subtropical communities (Ganeshram 2005). In South America, for instance, the fruit itself, that is the Christophine, is famous under its Nahuatl label Chayote (Saade 1996). In contrast, South Indians refer to it as the Chow Chow (Saade 1996: 13) and there appears to be a distinct possibility that the Mauritian term Chou Chou owes its name to the South Indians who migrated to Mauritius and neighbouring Reunion island during French and British rule and brought their linguistic heritage with them. In fact, the vegetable is so popular that there is even an annual Fête du Chou Chou (literally translated as 'feast of the Chou Chou') in nearby Reunion island (Panon 2014).

At first glance, the topical shift to Speaker 27's dietary preferences might seem rather incongruous. However, the pronunciation of the fricative [ƒ] in chou-chou as the sibilant [s] sou sou is a clever phonetic strategy adopted by the speaker, thus endowing her words with an undercurrent of sexual connotations. Indeed, in Mauritian parlance, while voiceless /ƒ/ sounds are routinely expressed as voiced sibilant /s/ segments, sou sou happens to be an exception since it functions as a slang word referring to female genitalia. In contrast to common lexical items such as chaque ("each") or charme ("charm"), which are pronounced as [sak] and [sa:m] respectively, speakers consciously avoid a similar phonetic process in the case of the term chou-chou. Thus, Speaker 27's tongue-in-cheek code-switch to such a connotative term can be interpreted as a subtle taunt towards her departing friend, reminding her that while her sister's chances of dating Y might be slim to none, he might fancy her enough to entertain the idea of a physical relationship with her. In this case, the judicious use of a popular slang item provides Speaker 27 with an opportunity to avenge herself of the hurt and embarrassment that she suffered at the hands of Speaker 26 as the latter opted to disregard Speaker 27's declaration of immense love. The crude reference to sex provides Speaker 27 with the satisfaction of having won the argument against her co-interactant while simultaneously allowing her to nurse her wounded ego after having her friendship and love so summarily rejected by a close friend.

There is another degree of ambiguity inherent in the term sou sou. Under its more Frenchified form of chou chou, it is not only homophonic, but also shares a very large degree of orthographic similarity with the French noun chouchou or its feminine counterpart chouchoute. The French Larousse dictionary defines a chouchou as either a child or a student who happens to be the parent's or the teacher's favourite. In its verb form of chouchouter, it refers to the excessive care, attention and affection bestowed upon a love. In the above extract, although the MC term sou sou is a slang item and might be considered offensive, the fact that speaker 26 does not immediately offer a response to speaker 27's crude references can probably be attributed to its phonetic similarity to its French counterpart. Although speaker 27 makes a strong case for their mutual acquaintance Y not wanting to date speaker 26's sister, the play on the word chou chou might not be lost on her as it might encapsulate her hope that Y might eventually come to regard her sister with affection.

In both extracts 1 and 2 a shared repertoire of slang items extends speakers' pragmatic abilities and endows them with the potential to make optimum use of the ensuing shift in conversational power dynamics.

4.3 Swearing in French

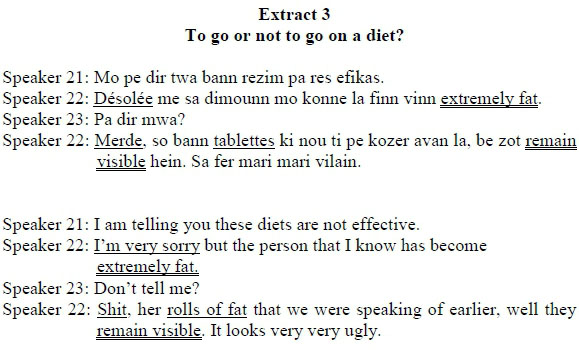

Not all the swear words used by participants were from MC or MB. A few of them were also derived from French. Extract 3 provides an example of a French swear word, accompanied byCS to English.

In the above extract, Speakers 21, 22 and 23 have been having an animated discussion about an acquaintance of theirs who has put on quite a lot of weight, as a result of which there has been a dramatic change in her physical appearance. Although the conversation has, for most of this interaction, been couched in MC, Speaker 22 switches to the French swear word merde before using the word tablettes to provide a very unflattering description of the rolls of fat that ostensibly make the above-mentioned person look extremely ugly.

This switch is a fascinating one given that the speaker could have easily opted for the more usual MC term lapang (literally translated as 'love handles') and an accompanying swear word in MC. In fact, according to the French Larousse dictionary, even in French, the literal translation of tablette (plural form tablettes) is not 'roll of fat'. A derivative of the French noun table ("table"), the word tablette commonly refers to either a small shelf or to a square of food items such as chocolate or chewing gum (tablette de chocolat, tablette de chewing gum). In the present context, it can de deduced that speaker 22 is comparing her acquaintance's rolls of fat to multiple shelves that have been stacked upon each other. It could also be taken as an insinuation that the latter's weight gain could be possibly attributed to the consumption of multiple squares of chocolate.

In such a case, the switch to French proves to be a strategic one because it allows the speaker to describe the physical consequences of weight gain in a more euphemistic way. Indeed, it has often been noted that discussions about weight gain and obesity tend to be sensitive issues because of the possibility of using words that might be deemed to be offensive. In fact, Mott (2009) observes that unflattering descriptions of a person's physical appearance remain one of the contexts in which a euphemism is the norm rather than the exception since honesty can be perceived as being deliberately insulting. Indeed, while the MC term lapang is more direct, it has a higher potential to offend. Consequently, Speaker 22 opts for the euphemism tablettes as a means to soften her harsh assessment of her acquaintance's physique, in an attempt not to embarrass her other co-participants who might not be comfortable with the more unsympathetic label of lapang.

However, what is interesting is that, even though, in other parts of the conversation, she sticks to the word tablettes, in this extract, she opts for the French swear word merde to frame her utterance. This suggests that even though she is following the expected norms of verbal propriety, she is unable to adopt a non-judgemental attitude to the weight gain of her acquaintance. In this case, although she knows that politeness is expected from her, she cannot remain tactful and considerate and one way for her to indicate her displeasure at her acquaintance's sedentary lifestyle is to use a swear word. The fact that she chooses to use a swear word from the same language as the pun tablettes is also significant. It indicates her possible need to maintain topical cohesion by associating the issue of weight gain and her judgement on the matter.

The choice of one language over the other when trying to appear agreeable and generally likeable is not new. Ramirez-Esparza, Gosling, Benet-Martínez, Potter and Pennebaker (2006) have shown that adult Spanish-English bilinguals can appear to be conscientious, likeable and agreeable when they are administered a test in English rather than in Spanish. This has led Ramirez-Esparza et al. (2006: 118) to conclude that multilingual speakers can and do "change their interpretations of the world, depending upon their internalized cultures, in response to cues in their environment (e.g. language, cultural icons)." In other words, as Speaker 22 illustrates, offering the same insult and the same assessment of her acquaintance in MC would have, perhaps, been deemed to be too brutally honest by her co-participants. The same arguments, when provided in French, appear to seemingly soften the blow. Another particularly noteworthy fact is that the conversation carries on without any gap or overlap. One of the indicators of the displeasure of a co-conversationalist is a violation of turn-taking rules and regulations (Schegloff 2007). So, for instance, in case Speakers 21 and 23 had been unhappy with the content and the formulation of Speaker 22's conversation, they could have shown their displeasure by seizing the floor away from her by either usurping her turn or instigating a switch to another language. This is not the case: in fact, the rest of the interaction takes place with MC as the matrix language and occasional switches to either French or English. The use of the swear word merde, coupled with the French word tablettes functioning as a pun, followed by a CS to English all coalesce to, eventually, allow the co-participants to deal with what might be a potentially difficult topic of conversation in a way that is acceptable to all of them.

4.4 Swearing in English

Another language utilised by the informants for swearing was English. An example is provided in Extract 4 below:

Extract 4 shows Speakers 1 and 2 debating the merits of buying a pink handbag. At first glance, it would seem that this extract contains very few instances of language alternation since the words pran nisa are widely recognised as MC colloquial terms preferred by the youth. However, this is not entirely accurate. The term nisa has, in fact, been borrowed from the Hindustani word nasha, which refers to a state of intoxication. With time, nasha got nativised into the Mauritian landscape so much so that nowadays, nisa can refer to both the state of drunkenness and the act of being teased. Similar cases of semantic extension can also be seen in the case of expressions like kass enn yen where the word yen can, depending on the context, mean both 'a strong hankering for' (just like its English counterpart, which is itself in turn derived from Cantonese) or 'to relax and have fun' (Auckle and Barnes 2011).

According to Siegel (2012), such semantic shifts are not uncommon in language contact situations. Citing Malaysian and Fijian English as examples, he asserts that, in both language communities, the interaction between multiple linguistic systems has culminated in a change of meaning of lexical items from both languages. For instance, in Malaysian English, the expression 'shake legs' has come to mean 'remain idle' - the consequence of the loan translation of the Malay idiom goyang kaki. Similarly, in Fijian English, the word 'vacant' is used to describe a house whose occupants are away for a short period of time. This is in line with the semantic range of the Fijian term lala, which means 'no-one at home' (Siegel 2012: 522). In fact, Siegel's (2012) perspective is one which was briefly touched on in the mid-1970s by theorists such as McClure (1976: 526) who maintains that "[t]he more contact an individual has with a second language, the more semantic borrowing his use of his native language will show". Simply put, she adopts a similar line of reasoning as Auer (1999) and Backus (2005) and believes that constant language alternation is one the catalysts contributing to the creation of words that are polysemous in nature.

What is interesting in the above extract is the pairing of the word nisa with the English swear word 'shit'. In fact, in this dataset, while MC and Bhojpuri swear words took different forms, so far as English and French are concerned, speakers opted for the more common merde or shit. It could be argued that since merde is commonly used by Mauritians in general, they might no longer consider it as a CS to French. A similar observation could be made for 'shit'. Adopted by MC speakers, it could, in essence, be acting as a framing device marking an impending switch to another language. Indeed, in the above extract, the main purpose served by the English swear word 'shit' is emphatic, as coupled with the word nisa, it indicates the exasperation of Speaker 2.

The emotional resonance of swear words in multilingual contexts is attested by various researchers such as Altarriba (2003) who asserts that when multilinguals need to provide an insight into their emotional state of being, they often resort to words from a language that they are most comfortable in. In the majority of cases, multilinguals will choose to utilise a lexical item from their L1, rather than from any other language of theirs. In the above extract, Speaker 2 does exactly that by using the term nisa to inform her co-conversationalist that she does not appreciate being made fun of. However, through the use of the English swear word 'shit', she also manages to dissuade Speaker 1 from troubling her further. Indeed, while Speaker 2 had, even before this extract, been complaining about the poor verbal behaviour of Speaker 1, the latter had not taken her seriously. Considering that the native tongue of both speakers is MC, the use of nisa, though potentially cathartic for Speaker 2, did not manage to get Speaker 1 to behave in a manner that would be more acceptable to Speaker 2. Consequently, the latter had to opt for a strategic form of CS to English in an attempt to convey the degree of her displeasure and exasperation. It should be noted that the pink handbag in question was not purchased by either speakers.

On the whole, this section has attempted to provide a few examples of swear words derived from the multiple languages with which the informants sampled in this study were conversant. It should be noted that although other instances of swearing are available, the swear words themselves tend to be overwhelmingly similar. In other words, despite the ready availability of other extracts illustrating the interactional act of swearing, the exact swear words themselves (for example, 'shit', merde, sou sou, and so on) occurred over and over again and in relatively similar contexts. Consequently, in this section, as mentioned earlier, only a few prototypical examples have been provided. In accordance with the CA method of analysis language alternation, the interpretational leeway of the analyst has been tempered by the views provided by the informants regarding their own language practices.

5. Discussion

Arguing for the conception of verbal performance as a creative expression of a speaker's masterful command over his linguistic repertoire, Bauman (1975) calls for an enhanced focus on performance-oriented features of conversation such as swearing. According to Bauman (1975: 293), indexing a specific reflexive position that the speaker conversationally orients himself to, performance "involves on the part of the performer an assumption of accountability to an audience for the way in which communication is carried out, beyond and above its referential content." In other words, the shift in conversational frame from one topic to the other or one style (for example, formal) to the other, empowers participants to 'enregister' their speech by allowing "linguistic forms [to] become ideologically linked with social identities" (Agha 2006, cited in Johnstone 2011: 657). This is also the case in the current study.

Although informants taking part in this study tended to have a limited repertoire of swear words, the co-occurrence of CS with interactional phenomena such as swearing indicates that they felt empowered to use language as a means to index an identity that is rooted in the sociocultural reality of Mauritius. Indeed, as the observations in section 4 highlight, language practices in all societies cannot take place in a social vacuum. By the same logic, since all multilingual communities around the world have a different socio-cultural background, the performance of language alternation is also bound to be distinctive. In the case of Mauritius, as this section will argue, the fact that the participants already operate within a sociocultural framework that places a high premium on the performance of multilingualism, they use all the tools available to them in their linguistic repertoire such as language alternation in order to construct equally dynamic performance-geared sessions during their own everyday conversational interactions. Insertional CS in the form of swear words, in this case, simply serves to reinforce the message that speakers wish to pass on to their co-conversationalists. So, for instance, the creativity of the young informants is displayed when they have recourse to swear words such as the phonetically ambiguous sou sou word, in an attempt to either indicate to a co-participant that the latter's switch to another language has been deemed as being inappropriate or as a euphemistic way to undermine another co-speaker's argument.

In the case of the swear word gogot, the switch to MC appears to be deliberately inserted as a form of verbal chastisement of a speaker who has expressed his unwillingness to provide assistance to his co-participant through a switch to the French temporal marker bientöt. In this particular situation, CS to a MC swear word functions as an indication of his co-speakers' disapproval of both his inability to provide the support that they expect from him and his attempt to thwart the peer pressure being exerted on him by moving away from MC. In the second instance, the swear word sou sou ("Christophine"), through its phonetic similarity with its French counterpart chou chou ("my pet"), allows speaker 21 to, convincingly and forcefully, express her opinion about speaker 22's sister's dismal love prospects. Once again, the switch to a swear word from MC, together with the homophony and consequent polysemy involved in the selection of such an ambiguous term, become valuable resources to the multilingual participants taking part in this study as they manage to get their argument across in as tactful a way as possible.

The above examples illustrate that, so far as the participants of this study are concerned, the judicious selection and maintenance of various languages appeared to be as crucial as the actual performance of those multilingual abilities. As theorists such as Auer (1984) and Li Wei (1998) argue, meaning is 'brought about' as a result of the particularities of a specific conversational interaction but this meaning-making process needs to be eventually understood from the perspective of a speaker who is as much a product of the community that (s)he operates in as the analyst is. Limiting the analyst's interpretational leeway does not, in any way, minimise the importance that a speech community's norms have on shaping the mental repertoire and subsequent linguistic repertoire of the speaker. In deference to the above argument, it is argued that the different forms of language alternation practices uncovered in the previous section should be understood in reference to the strong performance-oriented culture that has always existed in Mauritius. They should, in fact, be viewed as but another means through which interactants can give free rein to their creativity.

While the multilingual nature of Mauritius has been duly acknowledged by scholars (cf. Miles 1999), the performance of multilingualism in the daily life of Mauritians has, so far, remained largely understudied. Indeed, in contrast to the Caribbean where the co-existence of multiple languages in popular forms of cultural expression such as its musical texts has been the focus of research - for instance, Myers's (1998) and Ramnarine's (2001) work on the music of countries like Trinidad and Guyana - Mauritian pop culture and the language(s) in which it is couched is still shrouded in mystery. As a matter of fact, similar to its Caribbean counterparts, Mauritius also has a rich cultural and linguistic heritage. For the purposes of this study, emphasis is placed on one popular form of pop culture namely oral story-telling, which may involve both language alternation and multilingual swear words (Cangy 2012; Haring 2011).

During his fieldwork in Mauritius in the 1990s, Haring (2011) carried out a series of recordings with the story-teller, late Ton ("Uncle") Nelzir Ventre, who constantly underlined the importance of the performance mode for most face-to-face interactions in Mauritius. Labelling non-MC words as langaz ("language"), he revealed that he viewed the process of performance-oriented, interactive and possibly multilingual forms of story-telling and conversing as a process of 'translation' (Haring 2011: 186). In his words (Ventre's Interview 1990, cited in Haring 2011: 186, emphasis mine):

I had to have finished presenting [tradwir] the story - to present all the words to the people listening. Do you understand me? Drum players and musicians accompany me. There is no dancing at that point. Tradwir means to tell the whole story beforehand, while singing. No dancing, just drumming. Everybody sits down and listens.

As the above lines reveal, for story-teller Nelzire Ventre, multilingualism was an asset that could be capitalised on by the proficient story-teller or conversationalist. All it required was a willingness to carry out insertional CS from other languages in the matrix language of MC. The introduction of discourse particles from other languages was deemed to be beneficial to the MC lexicon as a whole, and presents the story-teller with the opportunity to broaden his/her target audience. Haring (2011: 186) notes that he has often "wonder[ed] how many other Southwest Indian Ocean story-tellers have been as expert translators as Nelzir Ventre" and how many other communities have been as sensitive to insertional CS as Mauritius has.

Although researchers like Dewaele (2015) offer compelling reasons for the insertion of embedded languages in a dominant matrix language, they very rarely pay sufficient attention to the sociocultural context that has resulted in the language behaviour that they are studying. This study shows that such an oversight can be detrimental to the overall understanding that sociolinguists have of the different conversational loci of switching. In the case of Mauritius, the use of swear words from multiple languages, ticks a number of the boxes from the extended checklist provided in section 2 of this article. Yet, these checkboxes only manage to describe and illustrate language alternation at work. They do not, necessarily, manage to explain the reasons behind the behaviour.

Haring (2011) fills in these gaps in the literature by connecting the performance of language with the sociocultural specificities that are part of the ethos of a speech community. In the case of Mauritius, the use of swear words from multiple languages can be explained by the oral culture that exists on the island - an oral culture which permits the co-existence of multiple languages, even while swearing, in daily face-to-face interactions. Oral story-tellers such as Nelzir Ventre are, undoubtedly, gifted. However, it should be borne in mind that, even in their case, imagination is firmly constrained within the boundaries of the social realities of the island. They indulge in extended sessions of 'translation' as they provide voice to their characters because this is a common enough occurrence in the daily life of the people that have inspired their tales.

So far as the informants of this study are concerned, switching from one language to the other while swearing, is facilitated by a sociocultural context, which adopts an intrinsically permissive attitude towards such forms of language behaviour. This is, once again, evidenced in the field of politics. On 1 May 2010, at Labour Day celebrations, then Prime Minister Navin Ramgoolam was called to address a crowd of supporters. Unfortunately, his speech was plagued by technical difficulties with the microphone, which were, according to him, not taken seriously by another member from his own party. Exasperated, he had recourse to a MC swear word to signal his disapproval (L'Express 2010). In his words: "Lipa marser tapitin ['it doesn't work you slut']". Upon being subsequently interrogated by the media, he explained that he was, at that particular point in time, not even speaking MC. Instead, he had simply switched to French - a fact that the media had not been alert enough to notice. According to him, the word pitin was, in fact, a nativised version of the French word putain and was perfectly acceptable in colloquial contexts. In other words, while the MC word pitin could be deemed to be offensive, the insertion of the French word putain, though equally derogatory, was considered by many Mauritians to be tolerable (L'Express 2010). Considering that he was elected in the general elections held in the same year for another mandate of five years, it can only be surmised that even claiming to code-switch to another language while swearing can have significant benefits for a speaker.

The above argument finds an echo in Bauman (2011) and Bell and Gibson (2011) who maintain that the sociolinguistic emphasis on 'natural, unselfconscious' speech should not render the analyst insensitive to other forms of context-specific and culturally-relevant vocal performances. To quote Bauman and Sherzer (1989: 7), performance consists of the "interplay between resources and individual competence, within the context of particular situations." In the case of individual speakers, this competence is honed through their continuous contact with the languages and the interactional norms prevalent in their own speech community. It should also be kept in mind that the informants taking part in this study were all either teenagers or young adults. The creation of youth discourse is, often, viewed as an enterprise that depends on linguistic features such as swear words as a form of communal glue to bind community members together. What this study demonstrates is that the reification of the boundaries between youth and middle-age can be inscribed within the broader socio-cultural macrocosm of a speech community. Multilingualism becomes a tool that all speakers, and in this case, youngsters can use to create a distinct identity of their own.

Eble (1996) has famously argued that teenagers and young adults use slang as a means to be sociable. This point is equally valid in Mauritius. The participants contributing to this dataset are all previously acquainted with each other and have established strong bonds of friendship. Their use of swear words is, therefore, one of the components of their we-code. But what makes this we-code uniquely Mauritian is its ability to replicate patterns of language behaviour evidenced in forms of pop culture such as oral story-telling. This bears powerful testimony to the fact that youth discourse, despite sharing certain overarching similarities across speech communities, is, at the end of the day, both culture and context-sensitive.

6. Conclusion

All in all, this paper has attempted to provide a brief snapshot of language alternation practices adopted by conversationalists while swearing. In accordance with previous research carried out by researchers such as Dewaele (2015), Pavlenko (2006) and others, it has demonstrated the pragmatic consequentiality of swearing in a multilingual context such as Mauritius. By focusing on the performance-oriented nature of CS in Mauritius, it has also argued for an interpretation of language alternation data, which are more sensitive to the sociocultural realities of the speech community on which it focuses.

In addition, this paper has contributed to research carried out in the field of youth discourse. So far, theoretical and empirical interest in the field of language alternation and youth language have tended to be limited to contexts that are very different from Mauritius. The application of sociolinguistic axioms derived from the field of age-based language variation does not always consider the impact that culturally-specific language practices may have on language. By connecting the dots between the practice of oral, multilingual story-telling and the creation of a distinctively Mauritian youth discourse, this paper has shown that it is high time for sociolinguistic theory in the fields of both language alternation and age-based language variation to take into account the culture and context-specific particularities of a speech community.

References

Auckle, T. 2015. Code Switching, Language Mixing and Fused Lects: Language alternation phenomena in multilingual Mauritius. Unpublished Dlitt et Phil Thesis. Pretoria: University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Allan, K. and K. Burridge. 2006. Forbidden words: Taboo and the censoring of language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Allan, K. 2003. The social lens: An invitation to social and sociological theory. North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. [ Links ]

Altarriba, J. 2003. Does carino equal 'liking'? A theoretical approach to conceptual nonequivalence between languages. International Journal of Bilingualism 7(3): 305-322. [ Links ]

Auckle, T. and L. Barnes. 2011. Code-switching, language mixing and fused lects: Emerging trends in multilingual Mauritius. Language matters 42(1): 104-125. [ Links ]

Auer, J.C.P. 1984. On the meaning of conversational code-switching. In J.C.P Auer and A. Di Luzio (Eds.) Interpretive sociolinguistics: Migrants, children, migrant children. Tübingen: G. Narr. pp 87-112. Available online: http://www.freidok.unifreiburg.de/volltexte/4466/pdf/Auer_On_the_meaning_of_ conversational.pdf (Accessed 7 April 2016). [ Links ]

Auer, J.C.P. 1999. From codeswitching to language mixing to fused lects: Toward a dynamic typology of bilingual speech. The International Journal of Bilingualism 3(4): 309-332. [ Links ]

Backus, A. 2005. Code-switching and language change: One thing leads to another? The International Journal of Bilingualism 9(3): 307-340. [ Links ]

Baker, P. 1972. Kreol: A description of Mauritian Creole. London: C. Hurst. [ Links ]

Bakker, P. and M. Parkvall. 2005. Reduplication in pidgin and creole. In B. Hurch (Ed.) The Handbook of Pidgin and Creole Studies. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. pp 511-532. [ Links ]

Bauman, R. 1975. Verbal art as performance. American anthropologist 77(2): 290-311. [ Links ]

Bauman, R. 2011. Commentary: Foundations in performance. Journal of Sociolinguistics 15(5): 707-720. [ Links ]

Bauman, R. and J. Sherzer. 1989. Explorations in the ethnography of speaking. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Bayard, D. and S. Krishnayya. 2001. Gender, expletive use, and context: Male and female expletive use in structured and unstructured conversation among New Zealand university students. Women and Language 24(1): 1-15. [ Links ]

Bell, A. and A. Gibson. 2011. Staging language: An introduction to the sociolinguistics of performance. Journal of Sociolinguistics 15(5): 555-572. [ Links ]

Bissoonauth, A. 2011. Language shift and maintenance in multilingual Mauritius: The case of Indian ancestral languages. Journal of multilingual and multicultural development 32(5): 421-434. [ Links ]

Blommaert, J. 1996. Language and nationalism: Comparing Flanders and Tanzania. Nations and Nationalism 2(2): 235-256. [ Links ]

Bond, M. and T-M. Lai. 1986. Embarrassment and codeswitching into a second language. The Journal of Social Psychology 126(2): 179-186. [ Links ]

Cangy, J.C. 2012. Le Sega, des origines ά nos jours. Mauritius: Edition Makanbo. [ Links ]

Carpooran, A. 2003. Des langues et des lois. Paris: L'Harmattan. [ Links ]

Carpooran, A. 2005. Langue créole, recensements et legislation linguistique á Maurice. Revue Frangaise de Linguistique Appliquée 10(1): 115-127. [ Links ]

Correia, C.P. 2003. Return of the crazy bird. New York: Copernicus Books. [ Links ]

Dewaele, J-M. 2004. The emotional force of swearwords and taboo words in the speech of multilinguals. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 25(2/3): 204-222. [ Links ]

Dewaele, J-M. 2010. Emotions in multiple languages. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Dewaele, J-M. 2013. The link between foreign language classroom anxiety and psychoticism, extraversion, and neuroticism among adult bi- and multilinguals. The Modern Language Journal 97(3): 670-684. [ Links ]

Dewaele, J-M. 2015. Guest post: Prof. Jean-Marc Dewaele- on winning the award for 'most obscene title of a peer-reviewed scientific article'. Verbal Identity Blog. Available online: http://www.verbalidentity.com/guest-blog-prof-jean-marc-dewaele-winning-award-obscene-title-peer-reviewed-scientific-article/ (Accessed 8 April 2016).

Drescher, M. 2000. Eh tabarnouche! c'était bon: Pour une approche communicative des jurons en francais québecois. Cahiers depraxématique 34: 133-160. [ Links ]

Duranti, A. 1997. Linguistic anthropology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Eble, C.C. 1996. Slang and sociability: In-group language among college students. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [ Links ]

Eriksen, T.H. 1999. Tu dimunn pu vini Kreol: The Mauritian Creole and the concept of creolization. WPTC-99-13. Available online: http://www.transcomm.ox.ac.uk/working%20papers/eriksen.pdf (Accessed 6 April 2016).

Ganeshram, R. 2005. Sweet hands: Island cooking from Trinidad and Tobago. New York: Hippocrene Books. [ Links ]

Goffman, E. 1981. Forms of talk. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [ Links ]

Haring, L. 2011. Techniques of creolization. In R. Baron and A.C. Cara (Eds.) Creolization as cultural creativity. Mississippi: University of Mississippi Press. pp 178-197. [ Links ]

Harris, C.L., A. Aycicegi and J.B. Gleason. 2003. Taboo words and reprimands elicit greater autonomic reactivity in a first than in a second language. Applied Psycholinguistics 24(4): 561-579. [ Links ]

Harris, C.L. 2004. Bilingual speakers in the lab: Psychophysiological measures of emotional reactivity. Journal of multilingual and multicultural development 25(2/3): 223-247. [ Links ]

Hein, M. 30 November 2014. Is English our official language? L'Express Available online: http://www.lexpress.mu/idee/255742/english-our-official-language (Accessed 5 June 2015).

Hoffman, E. 1989. Lost in translation: A life in a new language. New York: Dutton. [ Links ]

Javier, R. and L. Marcos. 1989. The role of stress on the language-independence and codeswitching phenomena. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 18(5): 449-472. [ Links ]

Johnstone, B. 2011. Dialect enregisterment in performance. Journal of sociolinguistics 15(5): 657-679. [ Links ]

Kalla, A.C. 1984. The Language Issue: A Perennial Issue in Language Education. In H. Unmole (Ed.) National Seminar on the Language Issue in Mauritius. Reduit, Mauritius: University of Mauritius Press. pp 117-136. [ Links ]

Lallah, R. 2001. Kreol and the Administration of Justice. In L. Collen (Ed.) Langaz Kreol Zordi: Papers on Kreol. Port Louis: Ledikasyon Pu Travayer. pp 42-58. [ Links ]

L'Express. 2 May 2010. Meeting 1er mai: Nita Deerpalsing dit que le juron prononcé par Ramgoolam ne la visait pas. Available online: http://www.lexpress.mu/article/meeting-1er-mai-nita-deerpalsing-dit-que-le-juron-prononc%C3%A9-par-ramgoolam-ne-la-visait-pas (Accessed 8 April 2016).

Léard, J-M. 1997. Structures qualitatives et quantitatives: Sacres et jurons en québecois et en franéais. In P. Larrivée (Ed.) La structuration conceptuelle du langage. Leuven: Peeters. pp 127-147. [ Links ]

Le Mauricien. 24 April 2013. Kreol au parlement: Un certain nombre d'implications doivent d'abord être étudiées. Available online: http://www.lemauricien.com/article/kreol-au-parlement-certain-nombre-d-implications-doivent-d-abord-etre-etudiees (Accessed 8 April 2016).

Li Wei. 1998. The why and how questions in the analysis of conversational code-switching. In J.C.P Auer (Ed.) Code-switching in conversation: Language, interaction and identity. London and New York: Routledge. pp 156-179. [ Links ]

McClure, E.F. 1976. Ethnoanatomy in a multilingual community: An analysis of semantic change. American ethnologist 3(3): 525-542. [ Links ]

Miles, W.F.S. 1999. The Creole malaise in Mauritius. African affairs 98(391): 211-228. [ Links ]

Miles, W.F.S. 2000. The politics of language equilibrium in a multilingual society: Mauritius. Comparative politics 32(2): 215-230. [ Links ]

Mooneeram, R. 2009. From Creole to standard: Shakespeare, language, and literature in a postcolonial context. Amsterdam: Rodopi. [ Links ]

Mott, B.L. 2009. Introductory semantics and pragmatics for Spanish learners of English. Barcelona: University of Barcelona Press. [ Links ]

Myers-Scotton, C. 1983. The negotiation of identities in conversation: A theory of markedness and code choice. International journal of the sociology of language 1983(44): 115-136. [ Links ]

Myers, H. 1998. Music of Hindu Trinidad: Songs from the India diaspora. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]