Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus (SPiL Plus)

versión On-line ISSN 2224-3380

versión impresa ISSN 1726-541X

SPiL plus (Online) vol.51 Stellenbosch 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.5842/51-0-698

ARTICLES

Deconstructing and reinventing the concept of multilingualism: A case study of the Mauritian sociolinguistic landscape

Rada TirvassenI; Shalini Jagambal RamasawmyII

IDepartment of Modern European Languages, University of Pretoria, South Africa. E-mail: Rada.Tirvassen@up.ac.za

IIEnglish Department, Mauritius Institute of Education, Mauritius. E-mail: j.ramasawmy@mieonline.org

ABSTRACT

This article aims at deconstructing the conception of multilingualism developed in mainstream sociolinguistics by critically examining the assumptions underlying this trend of research, which is grounded in the scholarship of Labov (1972), Fishman (1984) and even Gumperz (1972). In order to engage in that discussion, we use the Mauritian sociolinguistic landscape, as described by researchers following that tradition, as a case. We, thus, carry out a meta-analysis of existing sociolinguistic research conducted in Mauritius, which serve to illustrate the extent to which knowledge produced bear the influence of the structuralist approach. Then, we critically discuss and reflect upon the assumptions underpinning such research, and in so doing, challenge key concepts such as language and diglossia. Finally, we open a discussion on the need to adopt an alternative epistemological position in order to construct a different type of interpretation of the phenomenon following the ground-breaking work of scholars such as Makoni and Pennycook (2007), Herdina and Jessner (2002), Blackledge and Creese (2010), Garcia (2009) and de Robillard (2005, 2007).

Key words: Multilingualism, language, diglossia, linguistic ethnography, translanguaging

1. Introduction

The discussion and reflections we engage with in this article are based on the following premises. Sociolinguists hold the view that the scope of their discipline is limited to the description and explanation of the social patterning of language practice and attitudes towards languages (Fishman 1971). While we could lengthily examine what 'social patterning' really means and how it impacts research in this discipline, we hold the view that the terms description and explanation can be misleading. The first one implies that researchers' findings are mere representations of social reality as it exists, whereas the second one gives the impression that they have the tools and the knowledge to accurately identify the social mechanisms behind language practice and attitudes towards languages. Scholars who adopt this perspective believe that empirical data are collected from field work with reliable instruments and methods, and that these data, after being analysed with the conceptual tools provided by the discipline, offer objective and unquestionable findings. When these 'findings' are linked with social factors, scholars think that they can explain language use in its social context. The definition of multilingualism in mainstream or traditional sociolinguistics (a trend of research that draws from the type of theorisation of language and society phenomena initiated by Labov (1972), Fishman (1984) and even Gumperz (1972)) has emerged from this pattern of scholarship. In this approach to multilingualism, languages are viewed as static, monolithic, bounded, and countable phenomena; multilingualism is thus seen as the sum of the number of languages used by an individual (Grosjean 1989).

This article aims at deconstructing the conception of multilingualism developed in mainstream sociolinguistics. We start with a meta-analysis of existing sociolinguistic research conducted in Mauritius. Then, we critically discuss and reflect on the assumptions underpinning such research and show how these have impacted the type of knowledge constructed about multilingualism in Mauritius. This opens a discussion on the need to adopt an alternative epistemological position in order to construct a different type of interpretation of the phenomenon following the ground-breaking work of scholars such as Makoni and Pennycook (2007), Herdina and Jessner (2002), Blackledge and Creese (2010), Garcia (2009) and de Robillard (2005 and 2007).

2. The structuralist approach to the study of sociolinguistics: The case of Mauritius

2.1 An overview of the sociolinguistic landscape of Mauritius

In mainstream sociolinguistics, Mauritius is typically and indisputably presented as a multilingual, multi-ethnic and multicultural island. The ultimate aim of this stereotypical description of the sociolinguistic landscape of the island has been to depict the linguistic organisation of the Mauritian society. Taking into account the fact that 1.3 million people are linked with a dozen languages, researchers (e.g. Moorghen and Domingue 1982; Stein 1982; Baggioni and de Robillard 1990, 1993; de Robillard 1991; Bissoonauth and Offord 2001; Rajah-Carrim 2005, 2007, 2009; Sonck 2005; Sauzier-Uchida 2009; Bissoonauth 2011) have sought to provide an explanation of the social organisation of languages by focusing on the status of languages, their functional differentiation, and attitudes towards languages in different settings. The analysis of the linguascape, from the Structuralist perspective, has shown that there exists a stable hierarchy of languages conceptualised by the notion of diglossia (Ferguson 1959) and further refined by that of asymmetrical diglossia (Chaudenson 1984). From a social perspective, researchers (e.g. Eisenlohr 2004; Eriksen 1998) argue that language is closely linked to identity (language as a religious, ethnic and cultural identity marker) as well as other sociological variables such as gender, level of education, place of residence, socioeconomic status, as well as political, cultural, psychological and religious factors.

In the following section, we carry out a meta-analysis of these studies and question the notions and concepts with which knowledge about the sociolinguistic context of Mauritius has been produced.

2.2 A meta-analysis of the Mauritian sociolinguistic landscape

The approach adopted by mainstream sociolinguistics emanates from the principle that if social order is inherent in each human community, then, from a language perspective, there would be a similar 'sociolinguistic order' to which institutions adhere and which determine the language practice of the layman. It is believed that this can be perceived in language policy decisions, in the non-written rules of institutions and, from an empirical perspective, in the linguistic behaviour of the people.

The starting point of the 'description' of sociolinguists is the notion of speech communities and the belief of many sociolinguists, made explicit by Labov (2006: 380), that "the linguistic behaviour of individuals cannot be understood without knowledge of the communities they belong to". While linguists have adopted this notion, what they have failed to realise is that it is based on socio-political constructs, that is, the boundaries of a speech community are political, not linguistic.

Part of the explanation lies in the theoretical overlapping between sociolinguistics on the one hand and, on the other, disciplines like sociology and anthropology. As a matter of fact, adopting a behaviouristic approach, many studies have analysed linguistic data in relation to sociological variables (e.g. Moorghen and Domingue 1982, Eriksen 1998, Bissoonauth and Offord 2001, Rajah-Carrim 2005, Sonck 2005, and Bissoonauth 2011). Once the political boundaries have been established, these linguists describe the sociolinguistic organisation of the community with particular stress on the relationship among languages. In order to probe into that relationship, researchers normally draw upon the communicative functions of languages. Their study is 'refined' by two distinctions. First, they make a difference between formal and non-formal communications, and between written and oral communications. Second, they examine the 'passive functions' associated with languages used in places of worship which play a pivotal role in ethnic identity construction. We choose to use the term 'passive functions' rather than 'symbolical functions' which is often used in the literature because languages have symbolical functions in all social interactions.

2.2.1 The functional differentiation of languages

(i) Formal v/s non-formal and written v/s oral communication

Let us examine the first distinction, that is, the one between formal and non-formal communications, and between written and oral communication. As one could predict, researchers support their argument with 'empirical data' (see discussion in section 1). For instance, they always highlight that while the two European languages are the languages of formal communication, a closer observation based on the distinction between written and oral communication and further refined when a difference is established between prestigious formal communication and non-prestigious ones provides a more accurate representation of the subtle hierarchical difference between English and French (e.g. Miles 2000: 215-217). The argument provided is that English is the language of administration par excellence. All official communiqués and documents are in English, namely the Constitution, the laws, and documents from the Civil Service. To pursue further their typological classification of the functions of languages, researchers draw from the choice of language used for documents meant for the wider public (Tirvassen 1999). Two noteworthy observations are made: the tax return form is available in an English-French bilingual format, and French is the language of the written press. As a matter of fact, although English is seen, overall, as the prestigious language (Bissoonauth and Offord 2001: 398), the privileged status French enjoys over English in specific institutions cannot be overlooked (de Robillard 1991: 162; Sauzier-Uchida 2009: 113). In order to account for the complex relationship between French and English, researchers have coined the term asymmetrical diglossia (Chaudenson 1984). Except for the above circumstances, a strong line of demarcation is drawn between these two languages, and among all the other languages linked with the Mauritian community. The only language that has marginal access to official communications is Mauritian Kreol1 (de Robillard 1991: 162; Miles 1999b: 97; Sauzier-Uchida 2009: 113). It is seen as the language of everyday interactions (Rajah-Carrim 2005) and the lingua franca (Miles 2000). It is further associated with illiteracy and practical tasks (Sauzier-Uchida 2009: 115), its use being, until its standardisation and introduction as an optional subject in schools in 2012, restricted to communiqués from the Ministry of Fisheries addressed to fishermen, because they are categorised as coming from low-educated income groups (Tirvassen 1999).

When linguists switch their attention to oral communication in formal institutions, they highlight the respective functions of English, French and Mauritian Kreol. Their analysis leads them to talk of "a triglossic situation with English as the highest variety, followed by French and Creole in this order" (Bissoonauth and Offord 2001: 398). For example, it is reported that 80% of parliamentary debates take place in English, while the use of French is tolerated (Cziffra 1983). To further confirm their observations, scholars highlight that Mauritian Kreol is used to crack jokes or for abuses (see Table 3 in Sauzier-Uchida 2009: 113). Another domain of language use that has attracted the attention of sociolinguists is the judiciary. This is one further example where two types of parameters are taken into account to predict language use. Because English is the official language of the Supreme Court and the language which confers high officials their status, researchers point out that these high officials, namely judges, magistrates and lawyers express themselves in English (Cziffra 1983). They thus create a situation where police officers are compelled to resort to formulaic expressions in English, for example "Yes, your Honour" or "Present, your Honour" (Tirvassen 2014: 113). They also highlight the fact that although court proceedings are in English, large sections are in Mauritian Kreol or French. The explanation given is that the use of French is tolerated for court pleadings and that most questioning is carried out in Mauritian Kreol.

Schools constitute another institutionalised domain of language use and have been important research sites for sociolinguists (Tirvassen 1991, 2003; Auleear Owodally 2010, 2011, 2012, 2015a and 2015b). The education sector is thought to offer a microscopic view of the local linguistic context, where the hierarchical rapport among languages is more apparent as languages are categorised based on the functions assigned to them. Once again, researchers (e.g. Auleear Owodally 2010, 2011, 2012, 2014) first draw from official rules to depict the patterns of communications in an institution. Therefore, they refer to the Education Ordinance (1944 and 1957), which provides teachers with the possibility of using any language that the Minister deems appropriate at lower primary level, while as from the fourth year of primary schooling, English should be the medium of instruction. They point out that as far as the implementation of the Education Ordinance is concerned:

• Written texts (textbooks, examinations, etc.) are in the sole medium of instruction, that is, English (except for the other languages, e.g. French textbooks are in French), in line with the official policy of the government.

• When it comes to oral communication, usually teachers use Mauritian Kreol and English and sometimes even French, in particular in the urban Catholic schools. It must be acknowledged that there have been several insightful studies carried out.

However, they have been undertaken with the canons of structural linguistics even when researchers claim that their studies are grounded in sociolinguistics (Stein 1982; de Robillard 1991).

Researchers have also studied the use of languages in everyday social interactions. According to sociolinguistic research carried out by Stein (1982) and de Robillard (1991), the majority of oral communications is said to take place in Mauritian Kreol, while Bhojpuri, which is typically associated with Hindus, is reported to be used in what is referred to as rural areas. Sociolinguists also claim that, until recently, French was used mainly by people of European descent and by mulattos, for whom it is a first language, and in the private business sector where the use of French is widespread because it is predominantly owned by the 'Franco-Mauritians'. They claim that during the past decades, French has evolved into a language associated with prestigious social circles and has lately been linked with upward social mobility, explaining its extended use in the home environment (Baggioni and de Robillard 1990, 1993).

(ii) 'Passive functions' of language

The second distinction relates to the notion of 'passive functions'. This concept refers to language use in religious ritual communication and as an ethnic identity marker. Linguists and anthropologists alike concur in saying that the local population holds a consensual collective representation of Mauritian society as one that is constituted of separate ethnic groups, each of which is identifiable based on its particularities, among which, language is believed to be one of the indicators of ethnic belonging (Moorghen and Domingue 1982: 52; Eisenlohr 2004; Sonck 2005: 37; Rajah-Carrim 2005: 329, 2007: 69-70, 2009: 484; Eriksen 2007: 162; Sauzier-Uchida 2009: 113; Auleear Owodally and Unjore 2013: 228; Auleear Owodally 2014: 336337). These language practices serve to characterise the identity of each group are restricted to the private domain, such as religious practices and the languages linked to them. For example, French is linked to the Christian faith, particularly Catholicism, which is reported to be the faith of 30-35% of the population, while English is associated with the rather small section of the Protestant population. Oriental languages (such as Hindi, Marathi, Tamil, and Telegu) are associated with Hinduism, and Urdu or Arabic are the languages of Islam, practised by 16-17% of the population. What linguists fail to say is that these languages are used mainly to carry out rituals, while it is Mauritian Kreol which is widely used for the purpose of oral communication (de Robillard 1991). As a result, in a context of symbolic territorial confrontation among ethnic groups, the religious sphere does not provide a valorising enough context for the use of ancestral languages. This is why, it is believed that the status of these languages is displayed publicly in the language policy decisions. The promotion of ancestral languages in the 1940s constituted the best means through which the Hindus sought to achieve social legitimacy in their attempt to uplift themselves to an iconic position, although it was also matched by the control they exerted at the political level (Tirvassen 2003). A series of language policy decisions aiming at improving the status of Oriental languages were taken by the Prime Minister, namely Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam in the 1940s (Tirvassen 2003) and Sir Aneerood Jugnauth in the 1990s (Miles 2000). The educational sector was, hence, imparted with the institutional responsibility of settling the identity crisis, at least with regards to Oriental languages.

2.2.2 From languages to categories of languages

Further to the discussion above about the functions of languages, it is clear that linguists have categorised the languages linked to the island into typologies, with an established hierarchy, based on the languages' functions, domains of use, and perceived status. Although the number of clusters the researchers (de Robillard 1991, Miles 2000, Sonck 2005, and Rajah-Carrim 2005) choose to group the languages into vary, there is nonetheless consensus in the way they present the languages:

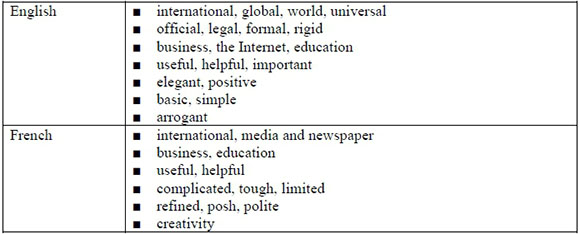

The aim of such a hierarchy is to shed light on the status attributed to these languages (see Moorghen and Domingue 1982: 52; Bissoonauth and Offord 2001: 383; Sonck 2005: 37; Rajah-Carrim 2005: 331), as illustrated by the table below from Sauzier-Uchida (2009: 113), which provides a list of perceived images towards languages.

From a theoretical perspective, the definition of the notion of status, as it has been first used by Kloss (in Cobarrubias 1983) and later refined by Ammon (1989) and Mackey (1989), is problematic. Researchers like Ammon (1989) argue that the demarcation between functions and status is far from being clear. Others (e.g. Smolicz and Illuminado 1997) define functions as an area relating to tangible use of languages and leading to the notion of complementary distribution in multilingual settings. Status would then refer to languages as an emblem of social behaviour. The question which is then raised revolves around the nature of the phenomenon. Is there anything like the national status of a language, allowing researchers to undertake research from an etic or outsider perspective to capture the status of languages? Or is it a subjective phenomenon strongly influenced by social dynamic interactions in which individual speakers are involved in everyday life situations?

3. Limitations of this description

The so-called description (see section 1) provided is drawn from the typical approach adopted when scholars want to provide an 'accurate picture' of language use in the speech community, grounded on the functions of languages. This overview is based on the assumption that official rules and regulations of institutions and the tacit rules of social interactions offer the necessary insight to predict language use and attitudes towards languages. This is far from true. The example that follows will serve to back our argument. Tirvassen (2014) reports a rather peculiar incident during an observation carried out in a court of justice. He mentions a man in his forties who had been accused of public nuisance while he was in fact drunk. On the day of the hearing, the usher asked the usual question: "koupab pa koupab?"5. The accused responded in an unusual manner, saying: "banker", a Mauritian Kreol word which comes from a common English word used in sports. According to those present at court, the man was also drunk during the hearing. While we could consider the man's reply as unorthodox and associate it with the irrational and marginal behaviour of a social outcast, should such language practices not be of interest to sociolinguists? In other words, should sociolinguistics only observe the language practices of those who conform to official norms? From a more general perspective, should social sciences focus on 'normative' social behaviour only? More importantly, as we will demonstrate later (see section 4.1), verbal interactions cannot be modelled out by the Structuralist notion of languages, whether these interactions occur in official institutions or in everyday life communication.

Consequently, we reiterate our point that the definition of multilingualism, which has emerged from research following a Structuralist tradition is grounded in this flawed representation of the sociolinguistic landscape of Mauritius. Multilingualism in the Mauritian context is described as a stable and organised sociolinguistic situation characterised by the juxtaposition of different languages. As we have seen through the meta-analysis of studies conducted, the conception of multilingualism underlying language practice and attitudes towards languages is based on the following:

• There exists a functional differentiation of languages that can be captured by the notion of complementary distribution; this implies each language has its own territory with possible overlapping that can be captured by the notions of borrowing and code-switching.

• The status of languages, which is the consequence of their relative prestige based on the functions they perform both from a communicational and a symbolical perspective helps to stabilise the situation. Both the complementary distribution of languages and their relative status regulate language use in a complex multilingual context.

What is ironic in such situations is that "we use tools of uniformization (grammars, dictionaries, and so on) invented for the construction of standard languages to do the descriptive and explanatory work of dealing with variation" (Heller 2008: 505).

4. Uncovering the underlying assumptions of the conceptual tools used

The approach to multilingualism in Mauritius as is the case with all studies undertaken in mainstream sociolinguistics is that scholarship is carried out with notions and concepts that are flawed. In this approach of the study of the language and society phenomena, both language and diglossia are perceived as first-order realities. This study will deconstruct two of the major concepts with which knowledge is produced, namely language and diglossia.

4.1 Language

Let us consider the first concept, that of language. According to Makoni and Pennycook (2007: 10-11), the concept of named language was invented in its sociocultural and political sense, based on an "ideology of countability and singularity, reinforced by assumptions of a singular, essentialized language-object situated and physically located in concepts of space founded on a notion of territorialisation". Such a definition of language as a system cannot be operationalised for language use in its linguistic sense, as pointed out by de Robillard (2005) and Tirvassen (2010, 2011 and 2014) who highlight the difficulties of reporting observations carried out in the Mauritian context. For instance, referring to the official logo of the Ministry of Tourism (Auckle and Barnes 2011), advertisements/posters from parastatal organisations (Tirvassen 2014) and from private organisations (de Robillard 2005), which are addressed to the wide public, these researchers show that the definition of language as a system is erroneous insofar as it does not allow for the modelling of these written texts produced by official institutions. This is because these posters make use of all the different linguistic resources provided by 'multilingual Mauritius' irrespective of the notions of boundaries and systems. For the purpose of illustrating the above, we shall analyse one of the sentences used in one of those posters: "Attention: tout installation électrique besoin faire par ène électricien competent"6 whose French equivalent is "Attention: toute installation électrique doit être effectuée par un électricien compétent"7. The similarity with French is striking. This is because French pragmatic style, that is, the use of the passive form to formulate instructions, has been adopted. In addition, the prepositional phrase "par ène électricien competent"8 and the verbal phrase "besoin faire par"9 are both also adapted from French. However, the verbs are not used in the inflected form nor are auxiliaries used. This is typical of the way verbs are used in Mauritian Kreol. All in all, based on the above example, we can say that the texts found on those posters are written in a code, which cannot be identified strictly to one language or the other, here Mauritian Kreol or French, if the concept of language is defined in its traditional sense.

Based on the above examples, we could venture to say that oral communication would also display similar characteristics in terms of the use of multilingual resources, especially given oral exchanges are less subjected to normative pressures than written communication. As pointed out by Tirvassen (2014), if a study was carried out by observing language practices disregarding the classification of language use as described earlier, the findings would indisputably show that actual language practices are not controlled and regulated by institutional norms. This is exactly what Auckle and Barnes (2011) report, referring to the use of hybridised language in local pop culture and youth lingo.

Other enquiries into teachers' language practices in Mauritius provide similar findings (Tirvassen 2011; Ramasawmy 2016). The studies show that teachers, who have been described as conforming to institutionally regulated language practices, make full use of their linguistic repertoire. Their language practices cannot be modelled by the concept of language. They use all the linguistic resources available to them, irrespective of language boundaries. One example from Tirvassen's (2011) study relates to a Maths lesson in a primary school where the teacher is carrying out a revision class on operations and provides examples to the pupils: "Alor 'operations', premie egzanp ki mo pu donn u par egzanp ... première question, example one: If operation y is equal to 'two plus y', find three operation one"10 (Tirvassen 2011: 108-109). The teacher uses Mauritian Kreol, English and French not as distinct named languages, that are countable, impermeable and static, but as flexible, fluid and dynamic. Similarly, Ramasawmy (2016) highlights the hybrid language practices of teachers Hence, the actual language practices of teachers are far from being guided by the strict categorisation of languages and the hierarchy the classification presented earlier (section 2.2.1) induces.

4.2 Diglossia

We shall now consider the second concept, that of diglossia. Basically, it sums up the approach adopted by macrosociolinguistics in postcolonial multilingual contexts. Diglossia has been used to paint a particular portrait of sociolinguistic situations, namely one where there is "... a relatively stable language situation in which, in addition to the primary dialects of the language (which may include a standard or regional standards), there is a very divergent, highly codified (often grammatically more complex) superposed variety, the vehicle of a large and respected body of written literature [...], which is learned largely by formal education and is used for most written and formal spoken purposes, but is not used by any section of the community for ordinary conversation" (Ferguson 1959: 336). It is important to point out that Ferguson's definition of diglossia is based on the idea of the specialisation of functions of languages. "One of the most important features of diglossia is the specialisation of function for H and L. In one set of situations only H is appropriate and in another only L, with the two sets overlapping only very slightly" (Ferguson 1959: 328). However, as the following example will demonstrate, the concept of diglossia is not appropriate to account for the multilingual realities of the Mauritian sociolinguistic context, whether the notion is restricted to the definition provided by Ferguson or takes into account the refinements brought to it by other sociolinguists such as Chaudenson (1984). Indeed, in an informal interview carried out with an illiterate woman in her sixties (Tirvassen 2014: 120), she was asked whether her grandchildren should learn "angle-franse"11 or Hindi, to which she replied "tou le de bon mem"12. What is interesting here is that angle-franse is referred to as one language. This compound form is typically used in Mauritian Kreol by those who have not attended school or who have hardly attended school. It translates their perception that these two languages are one entity because they are equally important. The asymmetrical diglossia, which linguists establish between English and French has meaning to them only and not to the laymen. The other is the refusal to rank these two categories of languages. In her social project, both are important although they serve different functions.

Translation = So, 'operations', the first example I'm going to give you, for example ... first question, example one: If operation y is equal to 'two plus y', find three operation one."

Mainstream sociolinguists posit that people in Mauritius are very much inclined towards French because of the edge they think it bestows in the social and professional domains (Baggioni and de Robillard 1990). In that sense, a hierarchy is established between French, the language of social mobility and Oriental languages, limited to the sphere of ritual religious communications. Tirvassen (2012) challenges this interpretation and suggests that the relationships people have with those two sets of languages are not necessarily incongruous. The example given above serves to show that the categorisation of languages as dominant or not is not applicable in the way people perceive language use in their social context. While the concept of diglossia is based on two principles: the separation of languages, and language hierarchies in dichotomous binaries, the informant in the previous example does not view the two languages in binary opposition.

Therefore, just like language as a cultural object and as a socio-political construct (Otheguy, Garcia and Reid 2015) fails to capture the dynamic multilingual realities of human interaction, so does diglossia in its representation of the relationship among languages. Languages, for the ordinary citizen, do not form part of a rational typology established by the linguist; they are resources managed by people in relation to their social, economic and identity projects.

These reflections lead us not only to challenge the analytical tools with which meaning has been constructed, but also ontological and epistemological assumptions on which scholars have drawn to interpret the language and society phenomena in Mauritius:

According to mainstream sociolinguistics, there exists an objective sociolinguistic reality out there, driven by social laws.

• The role of sociolinguistics is to describe the 'True' nature of that reality and explain how it works.

• Observed facts and indeed statistical figures are truths of an absolute nature and speak for themselves.

• In any case, the theoretical lenses of the researcher used to describe these truths are findings that have academic legitimacy.

• The methodological tools are reliable and unquestionable.

From the constructivist perspective that we have adopted to question the interpretation of multilingualism, facts only have meaning in relation to specific theoretical and conceptual tools used. As Guba (1990) points out, constructivists believe that specific facts only emerge within given theoretical frameworks which, themselves, have relative value. In addition, while theories can, in principle, (our emphasis) explain a body of facts, no theory can be fully tested. Human experience is far too varied, far too complex and is so tightly linked with changing contextual parameters for researchers to claim that they can explain them all: theories can explain a given body of facts but total generalisation is not possible. In any case, the researcher as a social agent, approaches human and social behaviour with his/her own values and bias. Objectivity is therefore not possible. In fact, ontologically, constructivists posit that social reality is always perceived by multiple people and these multiple people interpret events differently, leaving multiple perspectives of one and the same phenomenon. This is why constructivists adopt the position of relativism. The approach of multilingualism based on abstract metalinguistic concepts like language and diglossia or complementary distribution, etc. are meaningless to the layman and cannot model his language practice or his sociolinguistic projects or those of his children or grandchildren.

5. Towards a reconceptualisation of Multilingualism

Until recently, the field of linguistics has ignored that languages are social constructs and this has led to the "privileging of supposedly expert scientific knowledge over everyday understandings of language" (Harris 1990, in Makoni and Pennycook 2007: 18-19). As pointed out by Edwards (2009), this static notion of language has obviously had repercussions on the theoretical conceptualisation of multilingualism, so much so that there has been the coining of separate terms to refer to speakers of two languages - bilinguals, and speakers of more than two languages - multilinguals. A whole area of study has been dedicated to bilingualism and linguistic practices have been categorised yet again. Weinrich's (1953 in Edwards 2009) classification of bilinguals as balanced, compound or coordinate ones, Lambert's (1975 in Garcia 2009) model of additive and subtractive bilingualism, or other concepts such as sequential, elective, and circumstantial bilingualism presented in Baker (2011) no doubt illustrate this conceptualisation of sociolinguistics.

The social turn in the field of sociolinguistics has seen an interest in ethnography, thus giving rise to the area of linguistic ethnography (Blommaert and Rampton 2011). Coupled with this is the move away from a purely structuralist and cognitivist approach to a more socio-constructivist one which gives agency to the speaker and is concerned with an understanding of "language use as contextually embedded" (Blackledge and Creese 2010: 31). This paradigm shift along with supranational developments associated with globalisation, referred to as "super-diversity" (Vervotec 2007), as well as a revolution in technology and modes of communication (Edwards 2009), both account for the emergence of what some researchers in the field have called - "new multilingualism". The complex discursive practices inherent to multilingual practices cannot be described by the categories mentioned earlier. Even concepts such as first language, second language, additional language or mother tongue are inadequate to capture the dynamic processes of language use by multilinguals.

Using a complex systems approach, Larsen-Freeman and Cameron (2008: 155) explain that individuals' cognitive processes are "inextricably interwoven with their experiences in the physical and social world". Thus, this calls for an understanding from a psycholinguistic as well as a sociolinguistic perspective. The Dynamic Systems Theory based on the Dynamic Model of Multilingualism developed by Herdina and Jessner (2002) allows for this integrative approach. Indeed, the Dynamic Systems Theory adopts an ecological stance, thus advocating an interaction between cognitive ecosystems and external social ecosystems. Jessner (2008: 273) thus defines multilingualism as a dynamic and adaptive system, one which is:

... characterized by continuous change and nonlinear growth. As an adaptive system, it possesses the property of elasticity, the ability to adapt to temporary changes in the systems environment, and plasticity, the ability to develop new systems properties in response to altered conditions.

Thus, while an outsider defines a multilingual speaker by the number of named languages s/he uses, the multilingual speaker has a different perspective from the inside. For the latter, ". there is only his or her full idiolect or repertoire" (Otheguy et al. 2015: 281). As Canagararajah (2011: 1) explains:

For multilinguals, languages are part of a repertoire that is accessed for their communicative purposes; languages are not discrete and separated, but form an integrated system for them; multilingual competence emerges out of local practices where multiple languages are negotiated for communication; competence doesn't consist of separate competencies for each language, but a multicompetence that functions symbiotically for the different languages in one's repertoire; and, for these reasons, proficiency for multilinguals is focused on repertoire building.

This "deployment of a speaker's full linguistic repertoire without regard for watchful adherence to the socially and politically defined boundaries of named (and usually national and state) languages" (ibid. emphasis in the original) in a fluid, flexible, dynamic and creative manner, has been referred to by a plethora of terms, such as fluid lects (Auer 1999), polylingualism (Jorgensen 2008), metrolingualism (Otsuji and Pennycook 2009), and translanguaging (e.g. Williams 1996, 2002; Baker, Jones and Lewis 2012; Garcia, 2009; Garcia and Li Wei 2015), among others, although some nuances can be noted.

Based on this new conceptualisation of the phenomenon, multilingualism is not viewed as the subsequent acquisition of languages as separate entities. The multilingual speaker is no more perceived as a deficient monolingual, and the criterion for his/her linguistic abilities is not native-like competence anymore. As Kemp (2009: 19) says, ".each language in the multilingual integrated system is a part of the complete system and not equivalent in representation or processing to the language of a monolingual speaker." As a result, a multilingual speaker's languages function as a holistic and integrated system or linguistic repertoire, which is similar to a set of skills that the latter has at his/her disposal, and from which s/he draws depending on the communicative function and context.

6. Implications and avenues for post-Structural sociolinguistic research in Mauritius

Based on the arguments presented in this article, we call for more research to be carried out using a post-Structural approach. The few studies conducted by de Robillard (2005, 2007) and Tirvassen (2011, 2014, 2015) are steering research in a direction that we expect will significantly change the way language and multilingualism are perceived in Mauritian society.

Our discussion has revolved around the need for sociolinguistics to adopt a bottom-up approach and to marshal resources to set up research projects with the aim of observing and documenting actual everyday language practices. De Pietro (2005) puts forth a similar argument when he proposes his concept of norm. Drawing from theories such as variationism, interactionism and constructivism, De Pietro is thus able to conceptualise a more elaborate framework for the communication act. By focusing on the language practices of francophones living in the German-speaking area of Switzerland, he analyses this particular situation of language contact and the kind of tensions that arise as a result. According to De Pietro, each speech act in such a sociolinguistic situation contributes to the emerging norm. While these norms initially serve the immediate purpose of achieving a level of intelligibility between speakers of different languages, they are nonetheless closely linked with identity issues. De Pietro's work is also interesting insofar as he brings to light the coexistence of these changing negotiated communicative acts alongside the more prescriptive and standardised norms, which he, questionably though, associates with people of a higher social class.

There is a dire need to extend such research to the field of education as well. If we want to empower teachers and effectively equip them to handle a class in a multilingual context, qualitative research in the form of linguistic ethnography needs to be carried out. It is only by documenting the actual language practices of teachers and students in situ that the challenges these actors face in the classroom will be apparent. The analysis of these very language practices might provide insights into how to address the language difficulties both teachers and students face during the lessons.

By and large, whether one engages in theoretical or applied research, it is clear that the epistemological foundation, the conceptual tools, as well as the data production techniques need to be reviewed. It is only this paradigm shift in research that can, gradually in the long term, contribute in positively shaping the representation that multilinguals have of themselves and their language proficiency. The unsettling paradox multilinguals display, with on the one hand, their language ideologies grounded in monolingualism, a view of named languages as separate, static and bounded entities, and in neoliberal imperatives, and on the other, their hybrid language practices, is testimony to the epistemicide they have been subjected to. It is high time that the injustice and social inequality they have had to endure give way to a restorative image of their communicative and cognitive potential as multilinguals.

7. Concluding thoughts

As we have seen, the conceptual tools used by mainstream sociolinguistics partly explains the way multilingualism has been conceptualised. However, at the heart of the problem are the underlying assumptions on which the field has been built. Indeed, our argument is that the main issue lies in the epistemological foundations and the ontological stand of researchers in that area. For a very long time, sociolinguistics has followed a Structuralist approach and researchers have conducted studies from a Positivist perspective. Because Structuralism focuses on the system, it ends up denying the importance of the context whereas human behaviour cannot be detached from the meaning attached to it in a given social interaction. To conduct research, the sociolinguist adopts the sole emic or outsider view, which is compatible with the negation of the meaning that the common people attach to their language and social behaviour. Addressing the weaknesses of this paradigm implies the search for alternative approaches to scholarship based on different assumptions.

With the epistemological turn following Thomas Kuhn's ground breaking contribution on The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (Guba 1990), the impact of the qualitative approach to research has been significant. There are now alternatives to Positivism and this has opened a whole new vista. Actually, the fundamental beliefs about what constitutes knowledge and how to go about carrying research are all being questioned. Researchers have started to adopt a more reflexive stance towards their studies. The effect of this breakthrough in research has been tremendous even in the field of sociolinguistics. As a result, sociolinguists have redirected their focus on the actual language practices of individuals in their day-to-day context. Carrying out research from a different epistemological perspective has completely changed the way multilingualism is understood, especially in the Mauritian context, as shown by the few qualitative studies conducted so far (de Robillard 2005; Tirvassen 2011, 2014, 2015; Ramasawmy 2016). What is required are further in-depth studies that would enable a more adequate understanding of this phenomenon. They would contribute to the very challenging task of changing the representation of multilingualism that has been based on the definition of languages as named, countable and autonomous entities. The battle is clearly an epistemological one.

References

Ammon, U. 1989. Towards a Descriptive Framework for the Status/Functions (Social Position) of a Language within a Country. In U. Ammon (Ed.) Status and function of languages and language varieties. Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Auckle, T. and L. Barnes. 2011. Code switching, language mixing and fused lects: Emerging trends in multilingual Mauritius. Language Matters 42(1): 104-125. [ Links ]

Auer, P. 1999. From codeswitching via language mixing to fused lects: Toward a dynamic typology of bilingual speech. International Journal of Bilingualism 3(4): 309-332. [ Links ]

Auleear Owodally, A.M. 2010. From home to school: Bridging the language gap in Mauritian preschools. Language, Culture and Curriculum 23(1): 15-33. [ Links ]

Auleear Owodally, A.M. 2011. Juggling languages: A case study of preschool teachers' language choices and practices in Mauritius. International Journal of Multilingualism. doi:10.1080/14790718.2011.620108

Auleear Owodally, A.M. 2012. Exposing preschoolers to the printed word: A case study of preschool teachers in Mauritius. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 0(0): 1-46. doi:10.1177/1468798411429933 [ Links ]

Auleear Owodally, A.M. 2014. Language, education and identities in plural Mauritius: A study of the Kreol, Hindi and Urdu Standard 1 textbooks. Language and Education 28(4):319-339. doi:10.1080/09500782.2013.857349 [ Links ]

Auleear Owodally, A.M. 2015a. Supporting early oral language skills for preschool ELL in an EFL context, Mauritius: Possibilities and challenges. Early Child Development and Care 185(2): 226-243. doi:10.1080/03004430.2014.919494 [ Links ]

Auleear Owodally, A.M. 2015b. Code-related aspects of emergent literacy: How prepared are preschoolers for the challenges of literacy in an EFL context? Early Child Development and Care 185(4): 509-527. doi:10.1080/03004430.2014.936429 [ Links ]

Auleear Owodally, A.M. and S. Unjore. 2013. Kreol at school: A case study of Mauritian Muslims' language and literacy ideologies. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 34(3): 213-230. doi:10.1080/01434632.2013.763813 [ Links ]

Baggioni, D. and D. de Robillard. 1990. Ile Maurice, une francophonie paradoxale. Paris: L'Harmattan. [ Links ]

Baggioni, D. and D. de Robillard. 1993. Le francais regional mauricien: Une variété de langue en contact et en evolution dans un milieu á forte mobilité linguistique. Multilinguisme et développement, IECF/Didier Erudition, Paris. pp.141-237.

Baker, C., B. Jones and G. Lewis. 2012. Translanguaging: Origins and Development from School to Street and Beyond. Educational Research and Evaluation 18(7): 641-654. [ Links ]

Baker, C. 2011. Foundations of bilingual education and bilingualism. 5th Edition. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [ Links ]

Bissoonauth, A. 2011. Language shift and maintenance in multilingual Mauritius: The case of Indian ancestral languages. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 32(5): 421-434. doi:10.1080/01434632.2011.586463 [ Links ]

Bissoonauth, A. and M. Offord. 2001. Language use of Mauritian adolescents in education. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 22(5): 381-400. doi:10.1080/01434630108666442 [ Links ]

Blackledge, A. and A. Creese. 2010. Multilingualism: A critical perspective. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. [ Links ]

Blommaert, J. and B. Rampton. 2011. Language and superdiversity. Diversities 13(2): 1-21. [ Links ]

Canagarajah, S. 2011. Translanguaging in the classroom: Emerging issues for research and pedagogy. Applied Linguistics Review. Vol. 2: 1-28. Available online: https://www.degruyter.com/downloadpdf/j/alr.2011.2.issue-1/9783110239331.1/9783110239331.1.xml (Accessed 29 September 2012). [ Links ]

Chaudenson, R. 1984. Vers une politique linguistique et culturelle dans les Dom francais. Études Creoles, 1-2(VII): 126-141. [ Links ]

Cobarrubias, J. 1983. Ethical issues in language planning. Progress in Language Planning: international perspectives. Mouton publishers: pp. 41-86.

Cziffra, C. 1983. Statut et fonctions de l'anglais et du franqais ä l'Ile Maurice: Les pouvoirs législatif et judiciaire et la presse écrite. Unpublished PhD dissertation, Université de la Reunion. [ Links ]

De Pietro J.-F. 2005. Normes, identité et apprentissage en situation de contact. In L-F. Prudent, F. Tupin and S. Wharton (Eds.) Duplurilinguisme ä l'école - Vers une gestion coordonnée des langues en contextes éducatifs sensibles. Bern: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Edwards, V. 2009. Learning to be literate: Multilingual perspectives. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [ Links ]

Eriksen, T.H. 2007. Creolization in Anthropological theory and in Mauritius. pp 153-177. Available online: http://hyllanderiksen.net/Creolisation.pdf (Accessed 19 September 2016).

Eriksen, T.H. 1998. Common Denominators: Ethnicity, Nation-building and Compromise in Mauritius. Oxford and New York: Berg. Available online: http://hyllanderiksen.net/Denominators.html (Accessed 19 September 2016). [ Links ]

Eisenlohr, P. 2004. Temporalities of community: Ancestral language, pilgrimage and diasporic belonging in Mauritius. Journal of Linguistic anthropology 14(1): 81-98. [ Links ]

Ferguson, C.A. 1959. Diglossia. Word 15(2): 325-340, doi:10.1080/00437956.1959.11659702 [ Links ]

Fishman, J.A. 1984. Epistemology, methodology and ideology in the sociolinguistic enterprise. Language Learning (33)5: 33-47. [ Links ]

Fishman, J.A. 1971. The Relationship between micro- and macro-sociolinguistics in the study of who speaks what language to whom and when. In Bilingualism in the Barrio. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

Garcia, O. 2009. Education, multilingualism and translanguaging in the 21st Century. In A.K. Mohanty, M. Panda, R. Phillipson and T. Skutnabb-Kangas (Eds.) Social Justice through Multilingual Education. Bristol: Multilingual matters. [ Links ]

Garcia, O. and Li Wei. 2015. Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism and Education. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Grosjean, F. 1989. Neurolinguists, beware! The bilingual is not two monolinguals in one person. Brain and Language 36: 3-15. [ Links ]

Guba, E.G. 1990. The Alternative Paradigm Dialog. In The paradigm dialog. California: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Gumperz, J. 1972. Introduction. In J.J. Gumperz and D. Hymes (Eds.) Directions in Sociolinguistics. Holt: Rinehart and Winston, Inc. [ Links ]

Heller, M. 2008. Language and the nation-state: Challenges to sociolinguistic theory and practice. Journal of Sociolinguistics 12(4): 504-524. [ Links ]

Herdina, P. and U. Jessner. 2002. A dynamic model of multilingualism: Changing the psycholinguistic perspective. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [ Links ]

Jessner, U. 2008. State-of-the-art article teaching third languages: Findings, trends and challenges. Language Teaching 41(1): 15-56. [ Links ]

Jorgensen, J.N. 2008. Polylingual languaging around and among children and adolescents. International Journal of Multilingualism 5(3): 161-176. [ Links ]

Kemp, C. 2009. Defining multilingualism. In L. Aronin and B. Hufeisen (Eds.) The exploration of multilingualism: Development of research on L3, multilingualism and multiple language acquisition. The Netherlands: John Benjamins Publishing. [ Links ]

Labov, W. 2006. The Social Stratification of English in New York City. 2nd Edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Labov, W. 1972. Sociolinguistic Patterns. Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press. [ Links ]

Larsen-Freeman, D. and L. Cameron. 2008. Complex systems and applied linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Mackey, W.F. 1989. Determining the status and functions of languages in multinational societies. In U. Ammon (Ed.) Status and functions of languages and language varieties. Walter de Gruyer.

Makoni, S. and A. Pennycook. 2007. Disinventing and reconstituting languages. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters. [ Links ]

Miles, W.F.S. 1999. The Mauritius enigma. Journal of Democracy 10(2): 91-104. doi:10.1353/jod.1999.0036 [ Links ]

Miles, W.F.S. 2000. The Politics of Language Equilibrium in a Multilingual Society: Mauritius. Comparative Politics 32(2): 215-230. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/422398 (Accessed 14 September 2016). [ Links ]

Moorghen, P. and N.Z. Domingue. 1982. Multilingualism in Mauritius. Journal of the sociology of language 34: 5-66. [ Links ]

Otherguy, R., O. Garcia and W. Reid. 2015. Clarifying translanguaging and deconstructing named languages: A perspective from linguistics. Applied Linguistics Review 6(3): 281-307. [ Links ]

Otsuji, E. and A. Pennycook. 2009. Metrolingualism: fixity, fluidity and language in flux. International Journal of Multilingualism. 7(3): 250-254. [ Links ]

Rajah-Carrim, A. 2005. Language use and attitudes in Mauritius based on the 2000 Population Census. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 26(4): 317-332. [ Links ]

Rajah-Carrim, A. 2007. Mauritian creole and language attitudes in the education system of multiethnic and multilingual Mauritius. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 28(1): 51-71. [ Links ]

Rajah-Carrim, A. 2009. Use and standardisation of Mauritian Creole in electronically mediatedcCommunication. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 14: 484-508. [ Links ]

Ramasawmy, S.J. 2016. Multilingualism and Education in Mauritius: Teachers' language practices. Seminar Presentation - Celebration of World Literacy Day: Language and Education. MIE, Réduit, Mauritius, 7 September.

Robillard de, D. 1991. Développement, langue, identité ethnolinguistique: Le cas de l'Ile Maurice. Langues, Économie et développement Tome 2: 123-181, F. Jouannet et al., Didier Erudition, Paris. [ Links ]

Robillard de, D. 2005. Quand les langues font le mur; lorsque les murs font peut-être les langues: Mobilis in mobile, ou la linguistique de Nemo. Revue de l'Université de Moncton 36(1): 129-156. [ Links ]

Robillard de, D. 2007. La linguistique autrement: Altérité, expérienciation, réflexivité, constructivisme, multiversalité: En attendant que le Titanic ne coule pas. Available online: http://www.u-picardie.fr/LESCLaP/IMG/pdf/robillardCASno1.pdf (Accessed 20 August 2012).

Sauzier-Uchida, E. 2009. Language choice in multilingual Mauritius: National unity and socioeconomic advancement. Journal of Liberal Arts 126: 99-130. Available online: https://dspace.wul.waseda.ac.jp/dspace/bitstream/2065/32794/1/KyoyoShogakuKenkyu126Sauzier-Uchida.pdf (Accessed 5 March 2011). [ Links ]

Sonck, G. 2005. Language of instruction and instructed languages in Mauritius. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 26(1): 37-51. doi:10.1080/14790710508668397. [ Links ]

Smolicz, J.J. and Illuminado, N. 1997. Exporting the European idea of a national language: Some educational implications of the use of English and indigenous languages in the Philippines. Revue Internationale de l'Education 43(5-6): 507-526. [ Links ]

Stein, P. 1982. Connaissance et emploi des langues á l'Ile Maurice. Buske Verlag. [ Links ]

Tirvassen, R. 1991. Le problème de la langue d'enseignement á l'ïle Maurice:Une approche socio-politique. In Langues, Économie et développement, Tome 2. Paris: IECF/Didier-Érudition. [ Links ]

Tirvassen, R. 1999. La gestion du multilinguisme dans le domaine de la formation et de la vulgarisation: Une étude du cas mauricien. In R. Chaudenson and R. Renard (eds.) Langues et développement. Agence Intergouvernementale de la francophonie, Diffusion Didier Erudition, Paris, pp. 61-70.

Tirvassen, R. 2003. Les langues orientales á l'Ile Maurice ou la problématique du coüt de l'identité. In R. Tirvassen (Ed.) École et Plurilinguisme dans le sud-ouest de l'Océan Indien. Paris: l'Harmattan. [ Links ]

Tirvassen, R. 2010. Pourrait-on faire sans la langue et ses frontières? Etude de la gestion des ressources langagières á l'Ile Maurice. Des questionnements assumés, des réponses plurielles et de nouveaux enjeux, Cahiers de sociolinguistique 15(1): 55-75. [ Links ]

Tirvassen R. 2011. Curriculum et besoins langagiers en zone d'éducation linguistique plurielle. Le frangais dans le monde: Recherches et application: pp. 104-115.

Tirvassen R. (Ed.) 2012. L'entrée dans le bilinguisme, coll. Espaces Discursifs, l'Harmattan: Paris.

Tirvassen, R. 2014. Créolisation, plurilinguismes et dynamiques des langues. Paris: l'Harmattan. [ Links ]

Tirvassen, R. 2015. Langues et états-nations dans les pays du sud ou revoir les fondements théoriques de nos disciplines. French Studies in Southern Africa 245-215: 131-152. [ Links ]

Vervotec, S. 2007. Super-diversity and its implications. Ethnic and Racial Studies 30(6): 1024-1054. [ Links ]

Williams, C. 1996. Secondary Education: Teaching in the bilingual situation. In C. Williams, G. Lewis and C. Baker (Eds.) The language policy: Taking stock. Llangefni (Wales): CAI. [ Links ]

Williams, C. 2002. A language gained: A study of language immersion at 11-16 years of age. School of Education, Bangor. Available online https://www.bangor.ac.uk/addysg/publications/Language_Gained%20.pdf (Accessed 29 September 2012).

1 Mauritian Kreol is the creole used in Mauritius.

2 Arabic is not the ancestral language of the Mauritian Muslims per se. It has drifted into the Mauritian context because part of the Mauritian Muslims claim it as their ancestral language as it is the language of the Quran, although there exists Mauritian Kreol versions of the Holy book.

3 As has been demonstrated with the case of Arabic, this list has changed over time. For example, the ancestors of the Mauritian Muslims came from northern India, as well as Surat and Kutch, from Gujarat. They thus spoke Bhojpuri, Gujarati, and Kutchi. However, there was a shift to the use of Urdu in the late 19th and early 20th centuries (Rajah-Carrim, 2004). It must also be pointed out that Mandarin (used to refer to Modern Chinese) was introduced later. Hakka and Cantonese are the languages the forefathers of the Sino-Mauritian group.

4 The term used to refer to this group of languages changed along with the list of languages, as explained in footnote 2, above.

5 Translation: "Guilty or not guilty?"

6 Translation = Caution: all electrical works should be carried out by a certified electrician.

7 Translation = Caution: all electrical works should be carried out by a certified electrician.

8 Translation = by a certified electrician

9 Translation = should be carried out by

10 The words in bold are in Mauritian Kreol, the ones in italics are in French, while the underlined ones are in English.

11 English and French

12 Translation = They need to learn both.