Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus (SPiL Plus)

versión On-line ISSN 2224-3380

versión impresa ISSN 1726-541X

SPiL plus (Online) vol.51 Stellenbosch 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.5842/51-0-696

ARTICLES

Multilingualism and the language curriculum in South Africa: contextualising French within the local language ecology

Karen Aline Françoise Ferreira-MeyersI; Fiona HorneII

IInstitute of Distance Education, University of Swaziland, Swaziland E-mail: karenferreirameyers@gmail.com

IIFrench and Francophone Studies, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. E-mail: fiona.horne@wits.ac.za

ABSTRACT

In this article, we question the role of second additional language (that is, an optional, non-official language) teaching, with special reference to French at school level in South Africa. Over and above the fact that some additional languages reflect minority cultures and communities (Greek, Serbian, Hebrew, etc.), we consider their real and potential place in the promotion of multilingualism. As revealed as part of a regional research project, sponsored by the Agence Universitaire de la Francophonie, entitled Curriculum, contextualisation et formation des enseignants (CCPFE-AUF-BOI-S0195COV0401), motivations for studying French in South Africa stem from the dual representation of its exoticism, constituting a form of "linguistic tourism", as well as its potential usefulness in various professional contexts. We question whether the basis for this language market, which plays out in an exolingual, formalised context can make a real claim to promoting multilingualism within the South African linguistic ecology. In this regard, we will examine ways in which a shift in perspective from an "additive" to an integrative and plurilingual conception of language acquisition is required to resituate the teaching/learning of French as an authentic form of social and linguistic construction in South Africa. Using a socio-constructive (Molinié 2011) and co-actional model (Melo-Pfeifer 2015, Mroz 2012) to teaching French, we explore ways in which language acquisition can be a collaborative, integrative process, taking into account multiple cultural and language resources.

Key words: French, second additional language, South Africa, language market, multi- and plurilingualism

1. Introduction

The teaching of languages in South African schools has long been fraught with debate, tensions and sensitivities, particularly in relation to the continued exclusion and marginalisation of African languages. The democratic dispensation has attempted to counter this situation through linguistic policies, which actively promote multilingualism1 and the teaching/learning of local African languages, in line with the general goals of nation-building, diversity and tolerance (Language-in-Education Policy (LieP) 1997). The teaching of foreign languages at school level, ("second additional languages"), that is languages that are neither official nor national languages, has been absent from debates regarding local language ecology and multilingualism in South Africa. Generally, the teaching of these languages occupies a double role: as value adding "international" languages (such as in the case of French) and/or in cultivating minority linguistic and cultural communities in South Africa (such as in the case of Hebrew, Greek or Serbian). In this respect, the Second Additional Language (SAL) has been typically seen as distinct from existing local language repertoires (and cultures).

This article focuses on French as a foreign language and SAL within the South African School context, a language characterised by a weak presence in the country (in terms of the number of speakers), but which occupies an important place on the language market as a high status international language. We question the ways in which French is represented and "marketed" in the local imaginary and how these intersect within the polemics of national languages in terms of power dynamics, status and relevance. Further, we provide suggestions on how to bridge ideological and linguistic divides between the foreign and the local, through outlining principles for an integrated (Hufeisen and Neuner 2003) and plurilingual approach2 (Véronique 2005; Gajo 2006; Rispail 2006;) to the teaching and learning of French in South Africa.

The first part of this article provides an overview of the South African language curriculum at school level, the debate around the introduction of "The Incremental Introduction of African Languages (IIAL) in South African Schools" (2013) policy and its impact on the teaching and learning of SALs. The role of representations (viz. socially constructed attitudes) on the value of learning French in South Africa will be discussed in relation to the language market and multilingualism in South Africa. The second part of the article addresses the challenges of learning French as a foreign language, with reference to its late, formalised acquisition, and the ways in which these limitations may be overcome through drawing on existing cultural and linguistic repertoires to promote the general aim of plurilingual and pluricultural education.

The last part of this article focuses on how different approaches to language teaching and learning can be used to make the expected and necessary transition into exolingual situations where language negotiation finds its place within globalised citizenship. The Curriculum, contextualisation et formation des enseignants (roughly translated as the Curriculum, Contextualisation and Teacher Training Project) mentioned above provides some indications on how these could be implemented through new forms of language teacher training.

2. Language Politics and the South African School Curriculum

In line with the Constitution of South Africa, the LieP (1997):

[...] recognises that our cultural diversity is a valuable asset and hence is tasked, amongst other things, to promote multilingualism, the development of official languages, and respect for all languages used in the country, including South African Sign Language and the languages referred to in the South African Constitution.

Following the catastrophic consequences of Bantu Education3, the policy is based on the recognition that South Africa is multilingual and that the mother tongue (or Home Language) is the most appropriate language for learning. The addition of a second and third language as part of an additive bi-/multi-lingualism makes provision for a strong proficiency in another language, very often English by default, which is seen to guarantee linguistic and academic success (Heugh 2002). As per the 1997 LieP, obligatory official languages that are offered include the Home Language (HL) and one First Additional Language (FAL) subject. Foreign languages can be offered at SAL level and do not include official languages. Unfortunately, the narrow implementation of the policy has undermined multilingual education for several reasons, first and foremost because of the early transition to English medium instruction for a majority of African language-speaking students4, resulting in poor learning outcomes5. Very often, access to languages beyond English and Afrikaans is not guaranteed, meaning that historically inherited horizontal bilingualism has, to a large degree, been maintained. In short, little has changed in providing upliftment and equity to indigenous African languages at school level.

2.1 An "overpopulated" language curriculum?

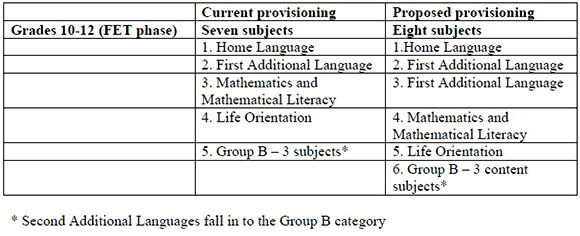

As a result of this situation, the Department of Education introduced a new policy called "The Incremental Introduction of African Languages (IIAL) in South African Schools", the explicit aims of which are to improve proficiency in African languages; increase access to languages to all learners beyond English and Afrikaans and promote social cohesion, economic empowerment and the preservation of heritage and cultures (Department of Education 2013: 6). In terms of the new policy framework, to be implemented from 2017, learners will offer three official languages from the first year of School, one at HL level and two at FAL level. By adding one obligatory African language to the curriculum, the policy constrains learners of all backgrounds to offer at least one African language (other than Afrikaans) at all phases of learning: Foundation, Intermediate, Senior and Further Education and Training (FET) phases (Grades 1-3, Grades 4-6, Grades 7-9, Grades 10-12, respectively).6 This means that offering a SAL, typically at FET phase, would constitute a fourth subject of learning (out of a total of eight subjects). As noted by the Independent Board of Examiners (IEB) (responsible for the assessment of non-official languages) in a submission to the Department of Education, the effects of this policy are potentially detrimental to the teaching of foreign languages at School level, in that the curriculum is overburdened7.

Both the IIAL policy rolled out by the Department of Education to promote the acquisition of African languages as well as the IEB submission to defend the value of teaching non-official languages are based a priori on similar rationales - first and foremost, the promotion of multilingualism, and with it, social cohesion, cultural and linguistic awareness, and tolerance. In the case of the IIAL policy, this is articulated within the local project of nation-building (DoE 2013: 6):

Community life takes place mainly in African languages. Learners proficient in African languages are thus able to participate and take leading roles in local institutions and organizations. However the linguistic skills and knowledge acquired in this formal education system are often not compatible with the linguistic skills and competencies needed in other, less formal contexts, especially in the informal sector.

Arguments advanced in favour of the teaching and learning of non-official languages reflect an outward-looking position, cogent of South Africa's aspirations to be a role player on the continent and in the world at large. In this regard, the international status of foreign languages is highlighted in the submission, as well as the "competitive edge" they afford learners on the job market (IEB 2015). The IEB document further refers to the importance of learning foreign languages in the context of local immigration, outlining the importance of preserving linguistic and cultural minority communities (Portuguese, Greek, Jewish, etc.) and through "combating xenophobia" (idem). Here the figure of the Francophone or Lusophone African migrant in South Africa implicitly shifts the argument from high status languages (and their respective privileged social enclaves) to a more inclusive Africanist agenda.

The tensions between these interest groups are borne out of an arguably "overpopulated" school language curriculum, attempting to accommodate as many official language combinations as possible. The resistance to the implementation of this policy highlights local and global agendas (which are certainly not mutually exclusive), as well as the tensions and representations particular to high and low-status languages, which are somewhat confirmed by the fact that most SAL are offered on the privileged margins of South African schools, in privately run or former Model C schools. While the intrinsic social, cultural and linguistic value of learning any foreign language cannot be denied, the receding status of SAL, at the crossroads between local language reform and the hegemony of English (perceived as the language of social ascension, distinction and employability both locally and internationally), seems inevitable.

2.2 French as a SAL - Euro-elitism or Afro-optimism?

The teaching/learning of French has an enduring tradition in South Africa, evidenced by dedicated French Language departments at secondary and higher places of learning, and private language schools and institutions such as the Alliance Francaise. Being neither an official, national, nor local African language, French occupies a position in the local imaginary as an "exotic" foreign language, embodying a number of widespread representations and stereotypes, some of which were identified in the research project described below. Indeed, for many learners, the language represents a prestigious form of linguistic and cultural capital that carries high symbolic and instrumental value.

In South Africa, learning French was historically a distinctly white, elitist enterprise, due to its "European" status and the fact that it was studied in white schools and universities only8. In the post-apartheid South Africa, a shift is taking place: French is no longer represented or marketed as the unique mono-linguistic/cultural vector of France, but also as an African language, whose linguistic and cultural plurality is inscribed in the notion of Francophonie. In the South African context, Francophonie has been used to describe the developing role(s) of French within the post-apartheid democratic project and its relation to Africa, viz. as a language of diplomacy, economy, politics, development, etc. (Balladon and Peigné 2010). It has also been used to describe the emergence of a locally rooted language identity, that is, of African Francophone migrants living in South Africa (Vigouroux 1998).

The reconfiguration of French within the democratic dispensation highlights transnational and transcultural trends linked to migration, globalisation as well as socio-economic priorities. Within this context, utilitarian and instrumentalist motivations for studying the language have increasingly come to the fore: learners see French as a potential professional asset and, more generally, one which would allow them to participate in global citizenship (Horne 2013). The undeniable fact that French is an international, super central language, occupying third position in the global language system after English and Spanish, respectively9, ensures its dominant position on the language market.

An yet, in spite of the repositioning of French in South Africa as a global and African language, it is taught in relatively few South African schools (private and former Model C) and only at the discretion of the school itself. Further, the language is being phased out at some of these schools. Over and above institutionalised tradition, this situation speaks to a lack of political and institutional will linked to the prioritisation of local languages at the expense of additional languages. As a result, French has largely remained a "luxury product" by default. Universities and Alliances Francaises offer beginner's courses to adult students and professionals to make up for this gap, but these are rarely sustainable in the long term.

2.3 Making a claim to multilingualism in South Africa

Can learning French make a real claim to promoting multilingualism in South Africa? This would mean both acquiring a level of functional proficiency and integrating and drawing on existing competence and repertoires. Preliminary observations would suggest that this is not possible. The "foreignness" of the French language in South Africa, as well as the niche, formalised teaching/learning contexts in which it is taught, preclude its use from authentic contexts of communication within the local language ecology10. In general terms, French cannot shape or be shaped by the local environment as it occurs outside this environment, in the somewhat artificial context of the classroom, which for the majority of learners represents the only form of contact with the language.

Over and above the structural constraints of teaching SAL, as cited above (viz. limited access, reduced contact time, late introduction in the curriculum), the conditions of the foreign language classroom hinder and indeed often suppress spontaneous forms of exolingual communication and their corresponding difficulties and lapses (Bange 1996). In contrast to the impromptu nature of spoken interaction in unguided and natural settings, formalised learning contexts are defined by ritualised roles and activities, including a linear and "additive" progression, explicitly defined outcomes and a stable distribution of roles (teacher/student). The drawbacks of these contexts are evident: learners do not have the opportunity to be "socialised" into the language, much less use it in conjunction with their existing language repertoires. All too often, in spite of teachers' best intentions (such as communicative simulations), declarative, passive knowledge does not transfer to procedural, active knowledge. In addition, the late introduction of SAL at school level (Senior and FET phases) and the limited number of allocated teaching hours, present obstacles to autonomous language proficiency11. One is tempted to ask: if, on the one hand, learners cannot participate in local communities of practice and, on the other, formalised teaching contexts inhibit true acquisition, in what way (if at all) can SAL such as French make a claim to promoting multilingualism? Could it be that the instrumental motivations articulated by learners for learning French are unrealistic? Or do they rather point to an illusory form of linguistic and cultural desire for otherness?12

3. Plurilingual and pluricultural competence

In a world characterised increasingly by multilingual and multicultural environments (of which South Africa is a prime example), a body of research around plurilingual pedagogy has opened up new ways of thinking about multilingualism in the classroom. Plurilingual competence, outlined by Coste, Moore and Zarate (1997; English translation, 2009), is defined as a range of partial and differentiated competence, which fulfil different roles according to language use and communicative function. This new paradigm is to a large degree replacing an additive notion of language competence associated with the communicative approach and based on the (unrealistic) model of the monolingual native speaker. This hitherto dominant position is seen as disempowering and unreflective of learners' linguistic and socio-cultural backgrounds. Plurilingual competence, on the other hand, is defined as the strategic manner in which individuals manage and draw on unbalanced language repertoires, a skill which remains key to building diverse forms of plurilingualism. Within this framework, the notion of translingual and transcultural competence, that is, the ability to operate between languages and cultures, has gained traction (MLA 2007; Kramsch 2008).

3.1 Project presentation

The educational and scientific community in the Southern Africa and Indian Ocean region possesses no recent data on the management of multilingualism in schools, which is what propelled the four-year (2013-2017) Agence Universitaire de la Francophonie (AUF)-funded project entitled Curriculum, contextualisation et formation des enseignants. The project is devoted to the analysis of the training of language teachers (in particular teachers of French) in multilingual contexts in the participating countries (South Africa, Comoros, Madagascar, Mauritius, Reunion (France), Mozambique and the Seychelles). It has the following main research hypothesis: multilingual and multicultural contextualisation13 is relevant and appropriate only when it mobilises learning to better manage the language contact situation in which the learner lives (in the case of South Africa, this refers to the contact between plurilingual learners in and outside the classroom). The project involves a variety of investigative tools (questionnaires, interview guidelines, class observation grid) and a number of regional stakeholders at different levels (government representatives, student-teachers, teachers, parents, learners) in a bid to obtain qualitative and quantitative data on whether: (1) Plurilingualism in the classroom is encouraged; and (2) teachers are trained/equipped to deal with plurilingualism and pluriculturalism.

The results of the preliminary research (literature review and pilot testing) undertaken between September 2014 and June 2015 were presented at a regional workshop in September 2016. A preliminary report on the project's first years of implementation as well as the workshop has been drafted (Ranaivo, V., Rapport d'avancement périodique 2015) and submitted to the sponsoring agency, AUF.

3.2 Preliminary results

The preliminary results, in the form of questionnaires responses (from decision-makers, teacher trainers, teachers - an example of this can be found in Annexure 2 - and learners) and a focus group with teachers provide a sense of participants' views and opinions on multilingualism. All teachers and trainers of teachers recognise that multilingualism is a government priority, as reflected in school curricula and official policy documents. However, one teacher notes that this policy "only applies to official languages and Mandarin", pointing to the exclusion of SAL within this framework. A second teacher trainer states that multilingualism "is a hugely underused resource in South Africa [as it develops] cognitive benefits; empathy; work opportunities and social cohesion". This view is further reflected by a decision-maker who signals the de facto use of English as the language of instruction, business and parliamentary interactions, and the disjuncture between "the priorities on paper and what gets prioritised through resources in reality". According to this respondent, "the greatest challenge is the lack of political will on the part of the government to enforce and resource multilingualism". This respondent points to the training of teachers in African languages and the lack of resource materials for effective teacher education as one of the major challenges in the implementation of multilingualism. This view stands somewhat in opposition to that of the French teacher working on the ground (cited above), who feels that African languages are being prioritised at the expense of SAL. The minor status of the French language within the schools system in South Africa is reflected by responses to the question "Is the development of Francophonie a priority of the educative system?" Teachers and teacher trainers respond mostly in the negative, insisting on government's focus on local languages and cultures. One respondent states that "most decision-makers don't even know that French exists at certain schools". At the opposite end of the spectrum, a single respondent states that "French is a hugely important language in Africa and key for the African Union as well".

Most teachers of French have a Bachelor of Arts degree and a Higher Diploma in Education, which is a general teacher training course offered across the board, for all subjects. Certain teachers have had the opportunity to update their skills through short courses, some of which are offered and sponsored (or at least partially subsidised) by the French Embassy in South Africa14. It is unclear whether these short courses propose approaches to multilingualism and multiculturalism.

Teachers describe their approaches as communicative and learner-centred and signal that they attempt to instil awareness in learners of the differences (and similarities) between languages and cultures. One teacher states that she draws parallels between English and Latin (and, to a lesser degree, Italian and Portuguese) in order to demonstrate similarities and differences between these languages and the target language, French. This was echoed in the focus group where participants emphasised a comparative approach to introducing new vocabulary, involving strategies such as translation to develop an inter-language awareness. To be noted here is the lack of African languages within this comparative approach (the main language of recourse being English), as well as the formal, structural and ad hoc use of inter-language comparison.

The research results show that, in general, learners have a positive view of multilingualism. They see it as something that fosters a dialogue between languages and cultures. Many learners in the region15 (65%) feel that the multicultural aspect is not yet taken into consideration in the classroom and that they learn about "civilisation" and culture outside the classroom or during their history classes. Some learners (25%) felt it was not the curriculum content that needed updating, but rather the teaching methods used in the classroom.

While there is clearly an understanding of the need for multilingualism and plurilingualism to be actively fostered in the classroom (together with multi- and pluriculturalism, even though this article does not focus on these aspects), one can question whether the informal comparative (and ad hoc) methods used by participants count as a functional and authentic way towards promoting these priorities. It seems as though while learners are immersed in multilingual contexts in informal settings, these are hardly drawn upon, if at all, in the classroom as valuable linguistic and cultural skills and assets. This could be partially ascribed to the fact that language subject teaching has traditionally banished other languages from the classroom, in an attempt to maximise contact time with the target language and avoid any supposed "interference" from the first language, an idea that has since been challenged: today, it is widely acknowledged that language learning reposes on the construction of metalinguistic hypotheses and comparisons with the first language (Bouchard 2012).

The question which then begs to be answered is the following: how can this situation be remedied? What can be done to equip teacher trainers and teachers with the necessary skills to ensure a pedagogical approach that can include and develop multi- and plurilingual competence16? What kinds of approaches can interact with learners' existing knowledge and competencies?

3.3 Preliminary suggestions for a plurilingual pedagogy

Ideally, multilingual education should promote an awareness of why and how one learns the languages one has chosen, an awareness of and the ability to use transferable skills in language learning, a respect for the language use of others, including non-normative varieties, irrespective of their perceived status in society. This goes hand in hand with increased respect for the cultures embodied in languages and the cultural identities of others. In order for this to exist in reality, teachers need to gain the ability to perceive and mediate the relationships that exist among languages and cultures, and adopt a global, integrated approach to language education in the curriculum.

In order to ensure that learners come out of the educational system with multi- and plurilingual competence to better face the professional (and personal) world in which they interact, a modified pedagogical "approach" is necessary. It has to be combined with a shift in attitude that moves away from the ideal of the "native monolingual" speaker, upheld for decades in foreign language pedagogy and its corresponding endolingual competence as the ultimate aim. Language teaching pedagogy should, on the contrary, move towards a model of exolingual competence (that is, communication between first language speakers and foreign language speakers or among foreign language speakers only). Within this perspective, and in line with translingual and cultural competence cited above, meaning is never evident, static and shared, but shaped by the multicultural and linguistic makeup of the speakers, who rely heavily on negotiation and cooperation for meaning. In this regard, teachers need to encourage an attitude of cooperation between learners and encourage the use of more than one language to facilitate metalinguistic conceptualisation and the execution of communicative tasks. This can only be done if teachers are trained to better understand their learners' multilingual background, as the preliminary results of the AUF-funded project suggest.

It is thus clear that the required change of attitude and building of multi- and plurilingual competence cannot be acquired without an appropriate teaching method and approach. Molinié (2011: 147) proposes the use of the biographical method, which is already well established in sociology, anthropology and education, and has now found its way into didactics. Written, audio and video correspondence, reflexive journals, (auto)biographies of language learners, socioconstructivist portfolios17 and "reflexive" drawings with subsequent verbal commentaries can be used to elicit awareness on plurilingual realities and have learners work on various linguistic and cultural repertoires and learning stages. When they listen to and gather language-life stories that can be used as sources of knowledge for cultural integration and as starting points for pedagogical intervention, teachers (and teacher trainers) comprehend the intrinsic link between pedagogy and teaching contexts, the fact that learners are a source of knowledge in and by themselves, and that comparing languages and cultures can take place without devaluing one of them. The end result of this comparing and accepting of the "other" would go far to undoing the "constructed" tensions between language groups since each language will be valued within the learner's enhanced linguistic repertoire as occupying different, but valuable roles.

4. Conclusion

One of the objectives of this article was to briefly describe the situation of the teaching and learning of French in South Africa at school level, from the particular point of view of multilingualism. The preliminary results of the AUF-funded research project entitled Curriculum, contextualisation et formation des enseignants show that, while most stakeholders (government, teacher trainers, teachers, learners and their parents) understand and value the concept of multilingualism, there is still little to rejoice about when it comes to its actual implementation in the language classroom. This is, among other factors, due to a hiatus in the teacher training curriculum, which could possibly be filled through the introduction in teacher trainer programmes of appropriate methodologies that provide for multilingual contextualisation. There should also be recommendations for better inclusion of such contexts in language policy and language education policy development.

As stipulated in the various charters and governmental policy documents, multilingualism is a vital tool for promoting democratic citizenship. Linguistic and cultural diversity and understanding are inseparable from this notion as multilingual skills underlie mutual comprehension. Language diversity ensures plurality and richness of representations. In our opinion, any educational system must offer the possibility of learning various languages from an early age and develop the skills required for independent learning in order to enable people to engage in lifelong language learning. This task should never be designed to promote the use of a single foreign language as a minimal channel of communication, having an essentially commercial objective (synonymous with a narrow, instrumentalist attitude to language learning).

The preliminary findings of our research project show that many of the desired characteristics, attitudes and abilities regarding comprehension and implementation of a plurilingual approach to the teaching of the French language in South Africa are not yet in place nor activated. The lack of the latter shows that teacher training programmes need to be infused with new skill-gaining and skill-transmission teaching approaches. At the core of plurilingual teaching and learning lies a combination of scientific, academic, general, but also expert and social knowledge (Council of Europe 2009). If one is plurilingually and pluriculturally competent, one can link resources in several languages/language varieties to solve problems in less known languages/varieties, one positions oneself as an attentive interlocutor in exolingual exchanges (where interlocutors do not share the same linguistic and cultural repertoires - as is certainly the case in South Africa) and one is able to associate, confront and articulate diverse experiences of plurality to transform them in competence. Finally, this requires a reflexiveness of one's linguistic and cultural environment.

References

Balladon, F. and C. Peigné. (Eds.) 2010. Le francais en Afrique du Sud: Une francophonie émergente? Numéro spécial (40): French Studies in Southern Africa. pp. 11-27.

Bange, P. 1996. « Considérations sur le röle de l'interaction dans l'acquisition d'une langue étrangère », Les Carnets du Cediscor [En ligne], 4, Available online: http://cediscor.revues.org/443 (Accessed on 28 October 2015).

Bouchard, R. 2012. « Didactique plurilingue, cycle dialogal et interaction exolingue ». In G. Alao, M. Derivry-Plard, E. Suzuki, S. Yun-Roger (Eds.) Didactique plurilingue et pluriculturelle: l'acteur en contexte mondialisé. Paris: Editions des archives contemporaines.

Calvet, L-J. 2006. Towards and ecology of world languages. Cambridge: Polity.

Canagarajah, S. 2013. Translingual practice: Global Englishes and cosmopolitan relations. Oxford and New York: Routledge.

Castellotti, V. and D. Moore. 2011. « La compétence plurilingue et pluriculturelle. Genèses et évolutions d'une notion-concept ». In: Guide pour la recherche en didactique des langues et des cultures. Approches contextualisées, P. Blanchet, P. Chardenet, Paris, Agence universitaire de la francophonie / Archives contemporaines. pp. 241-252.

Cenoz, J. and D. Gorter. 2011. « Focus on multilingualism », The Modern Language Journal, Special Issue: The Special Issue: Toward a Multilingual Approach in the Study of Multilingualism in School Contexts, 95(3): 356-369.

Conseil de l'Europe, 2009. Langues de l'éducation, languespour l'éducation. Plateforme de ressources et de références pour l'éducation plurilingue et interculturelle. Available online: www.coe.int/lang (Accessed 23 March 2016).

Council of Europe. 2001. Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge, U.K: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge.

Coste, D., D. Moore and G. Zarate, 1997. Compétence plurilingue et pluriculturelle, Strasbourg, Ed. du Conseil de l'Europe. English translation Coste, D., D. Moore and G. Zarate. 2009. Plurilingual and Pluricultural Competence, Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Department of Education. 1997. Language-in-Education Policy.

Department of Basic Education. 2013. The Incremental Introduction of African Languages at Schools (Draft Policy). Available online: http://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/Documents/Reports/IIAL%20Policy%20September%202013.pdf?ver=2014-04-09-162048-000. (Accessed 11 January 2016).

Gajo, L. 2006. « D'une société á une education plurilingues: constat et défi pour l'enseignement et la formation des enseignants ». Synergie Monde, 1: 62-66.

Garcia, O. 2009. Bilingual Education in the 21st Century: A Global Perspective. Malden, MA and Oxford: Basil/Blackwell.

Heugh, K. 2002. « The case against bilingual and multilingual education in South Africa: laying bare the myths: Many languages in education: issues of implementation ». In: Praesa, Occasional Papers no. 6. Available online: http://www.praesa.org.za/files/2012/07/Paper6.pdf (Accassed 17 January 2016).

Horne, F. 2013. Cultures et representations d'un champ disciplinaire en évolution: Le cas de la littérature au sein des études franqaises à l'université en Afrique du Sud. Unpublished DPhil. thesis. University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Hufeisen, B. and D. Neuner. 2003. « Le concept de plurilinguisme: Apprentissage d'une langue tertiaire - L'allemand après l'anglais ». Strasbourg and Graz: Conseil de l'Europe. Independent Examinations board, 2015. Public comment from the IEB: IIAL - Government Gazette 39406.

Jørgensen, J., M.S. Normann, L. Karrebaek, M. Madsen and J.S. M0ller. 2011. « Polylanguaging in Superdiversity ». Diversities 13(2), pp. 23-38. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/shs/diversities/vol13/issue2/art2 (Accessed 23 March 2016).

Kramsch, C. 2008. « Ecological Perspectives on foreign language education. ». Language Teaching, Cambridge University Press 41(5): 389-408.

May, S. (Ed.) 2013. The multilingual turn: Implications for SLA, TESOL and bilingual education. New York: Routledge.

Melo-Pfeifer, S. 2015. « Blogs and the development of plurilingual and intercultural competence: report of a co-actional approach in Portuguese foreign language classroom », Computer Assisted Language Learning, 28(3), 2015.

MLA (Modern Language Association; Ad Hoc Committee on Foreign languages). 2007. « Foreign languages and higher education: new structures for a changed world ». New York: Modern Language Association. Available online: https://www.mla.org/Resources/Research/Surveys-Reports-and-Other-Documents/Teaching-Enrollments-and-Programs/Foreign-Languages-and-Higher-Education-New-Structures-for-a-Changed-World (Accessed 16 September 2015).

Molinié, M. 2011, « La méthode biographique: de l'écoute de l'apprenant de langues à l'herméneutique du sujet plurilingue ». In P. Blanchet and P. Chardenet (Eds.) Guide pour la recherche en didactique des langues et des cultures. Paris: Edition des Archives contemporaines, en collaboration avec l'Agence Universitaire de la Francophonie.

Moore, D. and V. Castellotti. 2011. « La compétence plurilingue et pluriculturelle: genèse et évolutions d'une notion-concept ». In P. Blanchet and P. Chardenet (Eds.). Guide pour la recherche en didactique des langues et des cultures. Paris: Edition des Archives contemporaines, en collaboration avec l'Agence Universitaire de la Francophonie.

Mroz, A. P. 2012. « Nature of L2 negotiation and co-construction of meaning in a problem- based virtual learning environment: a mixed methods study ». Available online: ir.uiowa.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3098&context=etd (Accessed 23 March 2016).

Otsuji, E. and Pennycook, A. 2010. « Metrolingualism: Fixity, fluidity and language in flux ». In: International Journal of Multilingualism, 7.

Peigné, C. 2007. « 'Des fenêtres aux murs': la visibilité du français dans la perspective transitionnelle sud-africaine ». In: Le français en Afrique, Revue du Réseau des Observatoires du Français Contemporain en Afrique, Nice, 22, pp. 353-369.

Rispail, M. 2006. « Le français en situation de plurilinguisme : un défi pour l'avenir de notre discipline ? Pour une socio-didactique des langues et des contacts de langues ». In: S. Plane and M. Rispail (Eds.), La lettre de l'AIRDF, L'enseignement du français dans les différents contextes linguistiques et sociolinguistiques, 38, pp. 5-12.

Véronique, D. 2005, « Questions à une didactique de la pluralité des langues », In: Plurilinguismes et apprentissages. Mélanges Daniel Coste, M.-A.Mochet, M.-J. Barbot, V. Castellotti, J.-L. Chiss et al. Coord., Lyon, ENS-LSH.

Vigouroux, C. 1998. « Entité francophone ou identités francophones ? Les immigrés africains francophones en Afrique du Sud et leurs relations à la langue française ». In: Le français en Afrique, Revue du réseau des observatoires du français contemporain en Afrique. Available online: http://www.unice.fr/bcl/ofcaf/12/Vigouroux.htm (Accessed 23 March 2016).

1 Alternative models to multilingualism as proposed by, among others, Cenoz and Gorter (2011) and May (2013, the multilingual turn) include translingual practice (Canagarajah 2013), polylingualism (Jergensen, Normann, Karrebsk, Madsen and Meller 2011), metrolingualism (Otsuji and Pennycook 2010), translanguaging (Garcia 2009). We have chosen multilingualism and plurilingualism as our basic concepts.

2 In French, the notion of plurilingualism was first introduced by Daniel Coste in 1991. The first English translation of his book Vers le plurilinguisme: Ecole et politique linguistique used the terms multilingual and multicultural in 1997 and 2001, but replaced them with plurilingual and pluricultural in 2009. The history of the term was discussed in Castellotti and Moore (2011).

3 To quote Heugh (2002: 4): "Segregated education, a language policy designed for separate development, unequal resources, and a cognitively impoverished curriculum has resulted in the massive under-education of the majority of the population".

4 These are students whose first language is an indigenous African one and who are at a disadvantage when being taught in English at Foundation phase level.

5 See Heugh (2002).

6 See Annexure 1.

7 As argued in the submission, many learners would be reluctant to select a non-official language, as their curriculum would be overburdened with language learning, and they would have limited possibilities in terms of further study, especially those wishing to complete Bachelor of Science or Bachelor of Commerce degrees.

8 This perception was also reinforced by the distant memory of the French Huguenots in South Africa and their association with Afrikaner nationalism.

9 Calvet's barometer of world languages is an instrument used to measure the relative importance or weight of languages in the world, according to several factors, inter alia, the number of speakers, official languages, translations, presence on internet (Wikipedia), Nobel prizes in Literature (Calvet 2006). French is seen as "super central" in terms of its position within a constellation of languages that are more/less dominant on a global scale.

10 This dynamic does not apply to Francophone migrants living in South Africa, whose integration and social identity is characterised by navigating between new and existing language repertoires, which include French. Interestingly, the socio-economic status of many of these migrants means that to them French represents a "useless" language in South Africa, a far cry from the aspirational social and linguistic capital it represents to young learners (Vigoureux 1998).

11 At the end of the school syllabus, students have reached an A2 level according to the Council of Europe (2001)'s Common European Framework of Reference for Languages. This is arguably a threshold level for autonomous proficiency.

12 See Peigné (2007) for insights on the relationship to linguistic and cultural "otherness" that French represents to South African learners.

13 Contextualisation here means using language items in a meaningful and real context rather than being treated as isolated items for language manipulation practice only. Contextualising language gives real communicative value to the language that learners encounter. The context can help learners remember the language and recall it at a later date. Learners can thus use natural learning strategies to help them understand contextualised language, such as guessing meaning from contextual cues.

14 Such as the TFFL programme (Teaching French as a foreign language) offered at UCT, at Honours and Masters' level, and short courses with specialists in the field of French foreign language pedagogy.

15 21 learners participated in the pre-tests, 4 from South Africa, 3 from the Comores, 7 from Madagascar, 5 from Mozambique and 2 from Mauritius. Their ages varied from 15 to 22 years.

16 As alluded to in point two, this refers to the ability to put together diverse linguistic and cultural resources to solve problems (communication, identification, location in space and time, action and reflection) and in less familiar environments, to be conscious of the diversity of factors and challenges that contact situations generate (interlinguistic and intercultural) and to have a reflexive attitude towards knowledge and experience (Moore and Castellotti 2011: 251).

17 Socioconstructivists believe that portfolios can be used as tools to enhance both the students' learning (and personal comprehension of that learning) and the teacher's understanding of the students' progress.

18 Souligner le pays concerné.

19 Pour Madagascar, le pré-test enseignant en exercice peut se faire dans le privé ou à l'INFP ou dans les CRINFP (délocalisation de l'INFP en province).

20 Il s'agit des réalités malgaches (voire Equipe Pédagogique Inter-Etablissement).

21 Malgache, créole seselwa, etc. Choisir une langue en danger ou minorée?

22 Portugais, anglais, allemand, espagnol notamment

23 Donnez l'équivalent en anglais et autres langues si cela existe.

Annexures

Proposed subject provisioning as per the Incremental Introduction of African Languages in South African Schools policy:

Annexure 2: Initial survey used with in-service teachers

Pré-test

Enseignant en exercice

Le présent questionnaire porte sur les pratiques d'enseignants de langue en contexte francophone et plurilingue en Afrique du Sud, aux Comores, à Madagascar, à Maurice, au Mozambique, à La Réunion, aux Seychelles18.

Merci d'y répondre avec précision et sincérité.

1. VOTRE PROFIL

1.1 Sexe: F /_/ M /_/ Cochez la case appropriée

1.2 Age:......................................................................................................

1.3 Profession du (de la) conjoint (e): ...................................................................

1.4 Profession du père: ....................................................................................

1.5 Profession de la mère:.................................................................................

1.6 Dernier diplôme obtenu: ..............................................................................

1.7 Date d'obtention du dernier diplôme:...............................................................

1.8 Etablissement19: .......................................................................................

....................................................................................

1.9 Classes tenues:........................................................................................

1.10 Nombre d'années d'expérience

....................................................................................

2. LES PRIORITES DU SYSTEME EDUCATIF ET VOUS

2.1 D'après vous, le développement de la francophonie est-il actuellement une priorité du système éducatif?

Oui /_/ Non /_/ Cochez la case appropriée

Précisez brièvement votre réponse

....................................................................................

2.2 Selon vous, le développement du plurilinguisme est-il actuellement une priorité du système éducatif?

Oui /__ / Non /__ / Cochez la case appropriée

Précisez brièvement votre réponse

....................................................................................

2.3 Quelles activités menez-vous en vue d'une meilleure appropriation des textes officiels en vigueur (loi d'orientation, programmes, instructions officielles)?

2.3.1 Recherche de documents complémentaires support papier:

Toujours /_/ Souvent /_/ Rarement /_/ Jamais /_/ Sans Réponse /_/

2.3.2 Recherche de documents complémentaires via Internet:

Toujours /_/ Souvent /_/ Rarement /_/ Jamais /_/ Sans Réponse /_/

2.3.3 Confrontation avec d'autres systèmes éducatifs:

Toujours /_/ Souvent /_/ Rarement /_/ Jamais /_/ Sans Réponse /_/

2.3.4 Confrontation avec les textes officiels antérieurs:

Toujours /_/ Souvent /_/ Rarement /_/ Jamais /_/ Sans Réponse /_/

2.3.5 Echanges avec les collègues de l'Equipe Pédagogique d'Etablissement20: Toujours /_/ Souvent /_/ Rarement /_/ Jamais /_/ Sans Réponse /_/

3. ETRE ENSEIGNANT DE LANGUE

3.1 Pour vous, qu'est-c e qu'un bon enseignant dans le domaine des langues-cultures?

....................................................................................

3.2 Avez-vous reçu une formation en sociolinguistique?

Oui /_/ Non /_/ Cochez la case appropriée

3.3 Avez-vous reçu une formation en anthropologie?

Oui /_/ Non /_/ Cochez la case appropriée

3.4 Avez-vous reçu une formation en didactique des langues et des cultures (DLC)? Oui /_/ Non /_/ Cochez la case appropriée

3.5 De telles formations vous permettent-elles d'exercer votre fonction d'enseignant?

Tout à fait /_/ Suffisamment /_/ Pas vraiment /_/ Pas du tout /_/ Sans réponse /_/

Précisez succinctement pourquoi

....................................................................................

3.6 Les programmes de français en vigueur

de langue maternelle21

des autres langues22

sont-ils adaptés, selon vous?

....................................................................................

Tout à fait /_/ Suffisamment /_/ Pas vraiment /_/ Pas du tout /_/ Sans réponse /_/

Précisez succinctement pourquoi

3.7 Quel type de manuel ou de méthode utilisez-vous?

....................................................................................

3.8 Faites-vous participer vos élèves:

Toujours /_/ Souvent /_/ Rarement /_/ Jamais /_/

Précisez votre réponse

....................................................................................

3.9 Vous sensibilisez vos élèves aux différences entre les langues (différences d'ordre phonétique, morphosyntaxique, lexical et sémantique):

Toujours /_/ Souvent /_/ Rarement /_/ Jamais /_/

Précisez votre réponse

....................................................................................

3.10 Vous sensibilisez vos élèves aux différences entre les cultures (valeurs, attitudes, comportements, gestes):

Toujours /_/ Souvent /_/ Rarement /_/ Jamais /_/

Précisez votre réponse

....................................................................................

3.11 Vous prenez en compte le parler des jeunes:

Toujours /_/ Souvent /_/ Rarement /_/ Jamais /_/

3.12 Vous mobilisez la perspective actionnelle:

Toujours /_/ Souvent /_/ Rarement /_/ Jamais /_/

3.13 Dans vos enseignements, vous avez recours aux TICE:

Toujours /_/ Souvent /_/ Rarement /_/ Jamais /_/

Précisez votre réponse

3.14 Vous utilisez un référentiel de compétences de type CECRL23? Toujours /_/ Souvent /_/ Rarement /_/ Jamais /_/

3.15 Quels types d'évaluation mettez-vous en œuvre concernant les domaines:

- de la langue

....................................................................................

- de la littérature/ civilisation

....................................................................................

3.16 Les formes d'évaluation sommative concernant la connaissance de la langue, de la littérature/civilisation vous semblent-elles adaptées?

Tout à fait /_/ Suffisamment /_/ Pas vraiment /_/ Pas du tout /_/ Sans réponse /_/

Précisez succinctement pourquoi

....................................................................................

3.17 Dans la mise en place de l'approche interculturelle, vous rencontrez des obstacles de type:

- psychoaffectif

Toujours /_/ Souvent /_/ Rarement /_/ Jamais /_/

40 Ferreira-Meyers and Horne -matériel

Toujours /_/ Souvent /_/ Rarement /_/ Jamais /_/

-méthodologique

Toujours /_/ Souvent /_/ Rarement /_/ Jamais /_/

-autre, précisez

....................................................................................

4. VOS SUGGESTIONS

Vos suggestions en tant qu'enseignant pour un meilleur accès à la francophonie et au plurilinguisme.