Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Lexikos

versão On-line ISSN 2224-0039

versão impressa ISSN 1684-4904

Lexikos vol.33 spe Stellenbosch 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.5788/33-2-1842

ARTICLES

Lexicography, Culture and Mediation. Or Why a Good Lexicographer Must Also Be a Good Cultural Mediator

Die leksikografie, kultuur en bemiddeling. Of waarom 'n goeie leksikograaf ook 'n goeie kultuurbemiddelaar moet wees

Martina Nied Curcio

Università degli Studi Roma Tre, Italy (martina.nied@uniroma3.it)

ABSTRACT

Culture-bound items are often omitted in lexicographic resources, and when they are present, they are rarely described in an appropriate way, especially in bilingual dictionaries: the listed equivalents often do not reflect the meaning of the cultural word precisely, usage examples may be missing and above all - especially for a non-native speaker - important information on the cultural level is omitted (Nied Curcio 2020). Communication problems and misunderstandings which are triggered not by divergences on the linguistic level, but on the cultural level, can arise between speakers of different languages and cultures. Specific cultural knowledge and an advanced level of intercultural competence are required.

Mediation of texts and concepts and using mediation strategies can provide significant input developing the lexicographer's intercultural competence, which is essential for an adequate lexicographic description of cultural aspects. Mediators often resort to their plurilinguistic and pluricultural repertoire and use mediation strategies. The same skills can also be harnessed by lexicographers for adequate and successful descriptions of culture-bound items in lexicographic resources. In this article the focus is on the concept of mediation; the Companion Volume of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (2018) shows parallels in the requirements of skills between mediators and lexicographers, and advocates the use of mediation strategies by lexicographers to ensure that cultural information is adequately represented in the dictionary.

Keywords: bilingual dictionaries, cultural items, translation, intercultural competence, mediation, mediation strategies, plurilingual competence, pluricultural competence

OPSOMMING

Kultuurgebonde items word dikwels weggelaat uit leksikografiese bronne, en wanneer hulle aanwesig is, word hulle selde, veral in tweetalige woordeboeke, op 'n toepaslike wyse verklaar: die gelyste ekwivalente reflekteer dikwels nie die betekenis van die kultuurwoord akkuraat nie, gebruiksvoorbeelde mag ontbreek, en bowenal - veral vir 'n niemoedertaalspreker - word belangrike inligting op kultuurvlak weggelaat (Nied Curcio 2020). Kommunikasieprobleme en misverstande wat, nie deur afwykings op linguistiese vlak nie, maar op kultuurvlak, veroorsaak word, kan tussen sprekers van verskillende tale en kulture ontstaan. Spesifieke kultuurkennis en 'n gevorderde vlak van interkulturele vaardigheid word vereis.

Bemiddeling van tekste en konsepte en die gebruik van bemiddelingstrategieë kan belangrike insette lewer om die leksikograaf se interkulturele vaardigheid, wat noodsaaklik is vir 'n voldoende leksikografiese beskrywing van kultuuraspekte, te ontwikkel. Bemiddelaars maak dikwels gebruik van hul veeltalige en multikulturele repertoire en gebruik bemiddelingstrategieë. Leksikograwe kan ook dieselfde vaardighede vir die voldoende en suksesvolle beskrywing van kultuurgebonde items in leksikografiese hulpbronne inspan. In hierdie artikel word die fokus op die mediasiekonsep geplaas; die Companion Volume van die Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (2018) toon ooreenkomste in die vaardigheidsvereistes tussen bemiddelaars en leksikograwe, en steun die gebruik van bemiddelingstrategieë deur leksikograwe om te verseker dat kultuurinligting in die woordeboek voldoende verteenwoordig word.

Sleutelwoorde: tweetalige woordeboeke, kultuuritems, vertaling, interkulturele vaardigheid, bemiddeling, bemiddelingstrategieë, veeltalige vaardigheid, multikulturele vaardigheid

1. Cultural items in translation and in lexicography

Because of the globally interconnected and networked world, we find constantly ourselves engaged in cross-cultural communication (cf. Gudykunst and Ting-Toomey 1988), whether in everyday life, when travelling, learning a foreign language or in professional interpreting and translating. Comparable situations in which communication is misunderstood and even disrupted as a result of cultural divergences are numerous, precisely because communication partners often concentrate on the linguistic level and disregard the cultural level. However, every language contains a large number of culturally determined words. These relate to everyday life (plants and animals, food, clothing, housing, work, leisure), politics, religion, geography, nature, ethnography, justice and administration, as well as social rules and values and the image that people or a nation have of themselves and others (cf. Newmark 1988). In the broadest sense languages are carriers and symbols of identity of a national/ethnic entity or culture assigned to a country, a region, a continent.1

In translation studies it is acknowledged that there are various terms that refer to a concept that is clear to a native speaker, but often remain unclear in their cultural connotations to a second-language speaker.

In translation studies, these references have been variously referred to as cultural references (or referents), cultural elements, culture-specific items, realia or culturemes. All these terms intend somehow to point to a concept that can be more or less intuitively grasped, at least by translators and translation scholars (Marco 2019: 21).

Cultural items are repeatedly the subject of theoretical and methodological discussions, since there is often a lexical gap in the other language as a result of cultural incongruence2 (Stolze 1999: 224).

[I]f there is a lexical gap, i.e. if words or phrases are not known or when lexical equivalents do not exist in the target culture and language, such culture-specific items cause problems in translation (Persson 2015: 1).

Translators are challenged to address this lack of appropriate words in one language; they have to fill the lexical gap and - if possible - to find the appropriate lexical expression (while also devoting attention to the register and possible linguistic connotations of the variety). Alternatively, if no equivalent of the culture-bound item exists, they are challenged to describe the cultural item in an adequate and comprehensible way. It is their task to ensure the most precise reception of the culturally determined word or expression by the users.

Not only in translation studies, but also in lexicography, the question of translatability or strategies for the transfer of cultural items has been dealt with extensively, because the lexicographer has to face the same challenges when dealing with cultural items in a dictionary. Based on the theoretical studies of Molina Martínez (2006) and Luque Nadal (2009) and combining the different nuances of this concept, Sanmarco Bande (2017) provides a very useful definition of cultural items for meta-lexicography, putting the focus on contrasts, i.e. language and culture comparison,3 thus working towards overcoming the problem. Sanmarco Bande (2017: 303) states that the most effective method of dealing with culturally specific words is not only offering the closest equivalent to the source language term, but also addressing the entire microstructure with a combination of different strategies: clarifications in brackets, numerous linguistic labels, clear and well-contextualised examples, semantic, cultural and pragmatic remarks, all reinforced by targeted typography. It is necessary to continue reinforcing the translation with other parts of the microstructure, because without the support of these tools, it is very likely that the user will misinterpret the information provided within the translation.4

One could assume that lexicographers have by now solved the translation problem of cultural items in bilingual dictionaries and that these dictionaries offer suitable equivalents for the users. However, this is - as already mentioned - a fallacy with regard to the cultural level. While much attention has been devoted to cultural items that are typical of a particular culture or nation and that have neither a linguistic nor a cultural equivalent in another language (German: "Kulturspezifika"),5 less attention has been devoted to an adequate translation or lexicographic description of cultural items that are typical of several (at least two) cultures and for this reason have linguistic equivalents in the other language (German: "Kulturwort")6 (for a categorization of culture-bound items for lexicography cf. Nied Curcio 2020). The equivalents are very often not completely equivalent; without intercultural competence, the cultural divergence is not recognisable at first glance. Words such as breakfast or coffee always have an equivalent in bilingual dictionaries, i.e. breakfast: ontbyt (Afrikaans), Frühstück (German), petit déjeuner (French), (prima) colazione (Italian), café da manhã (Portuguese) kahvaltı (Turkish), reggeli (Hungarian) or coffee: koffie (Afrikaans), Kaffee (German), café (French), caffè (Italian), café (Portuguese) kahve (Turkish), kávé (Hungarian). Some of these "Kulturwörter" can be international and quite easy to understand, but at the cultural level they are often false friends in terms of content, usage, habits and traditions. As can be seen in Figs. 1-4, the choice of ingredients that are part of a (typical) breakfast can vary across different cultures. (Figs. 1-4)

Let's take a closer look at coffee. Despite the linguistic equivalence between German Kaffee and Italian caffè, cultural differences are apparent, which remain hidden if only the linguistic level is taken into account. It is generally known that we are dealing with two different types of coffee with different preparation processes. At first glance, this comparison at the word level seems very trivial, but what is less known, however, and can therefore also lead to misunderstandings, is that the cultural concept of drinking coffee differs in Germany compared to Italy. The question "Shall we have a coffee?" can lead to major misunderstandings. Some Germans become irritated when they are invited to have coffee in Italy because the Germans usually link "drinking coffee" to the cognitive concept of the German Kaffeeklatsch, which includes sitting at a table, having a chat and probably eating cake (Kaffee und Kuchen). By contrast, they experience that drinking a coffee in Italy is all about standing at the counter with an espresso, not sitting comfortably at a table, not chatting for a long time and most probably not even having a piece of cake. Everything is over in a few minutes. If you are offered an espresso as a guest at home in Italy, the coffee is usually served perfectly, i.e. the amount of sugar requested by the guest is added and stirred. A German may feel uncomfortable or even offended in his autonomy. It might seem to them that they are not capable of doing this themselves. Misunderstandings like these occur frequently in everyday life, and are usually resolved through tolerance and understanding. If we move on an international political level, cultural differences can also lead to more serious conflict if the parties are not familiar with the other culture and are not aware of differences in specific cultural contexts.

2. Mediation and Lexicography

2.1 Cultural items in an Italian-German dictionary - a case of mediation

In bilingual dictionaries - even online - cultural items are usually considered as equivalences and their cultural level and possible differences between cultures/ culture nations are not taken into account (Fig. 5 and Fig. 6).

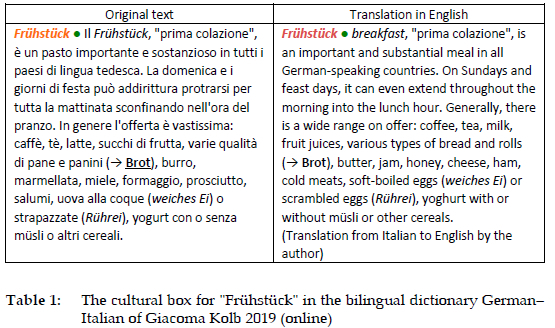

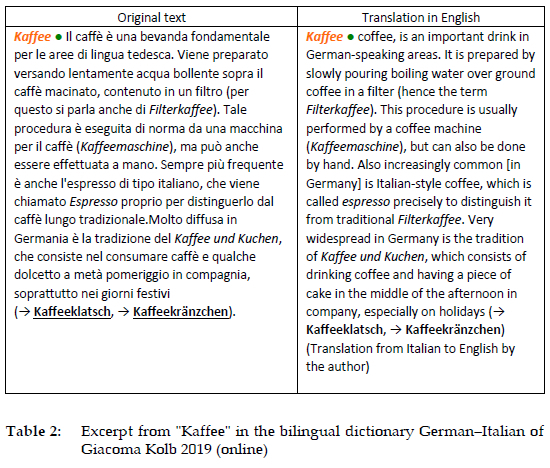

An exception with regard to the German-Italian language pair are the dictionaries Giacoma Kolb 2019 and Verdiani 2010 in which cultural information has been added in specially designed boxes at the end of the dictionary entry (Table 1 and Table 2).9

These two examples show how important cultural information has been added. The entry points out that Frühstück in German-speaking countries - in contrast to the customs and traditions in Italy - can go on until lunchtime on certain days and that both savoury and sweet food can be served. Additional explanations in the case of Kaffee refer not only to the fact that the typical coffee is a filtered coffee, but that the Italian espresso has become equally widespread; therefore naming the two types should be done carefully to distinguish clearly between the two. The entry also explicitly refers to the habit of having cake with coffee, usually in the afternoon and especially during the holiday season.

2.2 Mediation activities and strategies - tools for a successful lexicographer

In Giacoma Kolb (2019) and Verdiani (2010), these space-consuming information boxes are present in the print version, too. This means that an adequate representation of cultural items does not primarily depend on the space available in the dictionary. In contrast, both PONS and LEO, where the space argument does not play a role, lack qualitatively reliable cultural information. There we even find the tendency to link all word entries to one linguistic equivalent in the other language, so that a bi-directional search is possible, which makes the same word appear as a lemma in back and forward translations. (cf. Figs. 5, 6) This falsely reinforces the assumption of a 1:1 correspondence, which in reality does not exist. So it is not a question of whether a dictionary is printed or made available online, but whether the lexicographers are aware of the specific cultural meanings and of the intercultural divergences, as well as on whether they explicitly choose to represent such differences in the dictionary (Nied Curcio 2020: 200).

The prerequisite for this approach is that lexicographers - even in a time of digitalisation, in which translation machines and computer-assisted translation tools surpass dictionaries - have very good knowledge of both their own culture and the culture of the target user. Furthermore, lexicographers - especially in bilingual or plurilingual dictionaries - should act as mediators in communicating the adequate description of cultural items. Only on this condition can culturally specific items have a chance of being included in a dictionary at all, and being adequately presented.

What does it mean to act as a mediator? Mediators are intermediaries between interlocutors who cannot understand each other directly. They act as social agents who build bridges and help construct or mediate meaning, generally from one language to another (cross-linguistic mediation) and sometimes within a language, between different varieties (e.g. standard language - dialect) or modalities (e.g. from spoken language to sign language). A very good mediator (C2 level)

[c]an mediate effectively and naturally, taking on different roles according to the needs of the people and situation involved, identifying nuances and undercurrents and guiding a sensitive or delicate discussion. Can explain in clear, fluent, well-structured language the way facts and arguments are presented, conveying evaluative aspects and most nuances precisely, and pointing out sociocultural implications (e.g. use of register, understatement, irony and sarcasm) (Council of Europe 2018: 105).

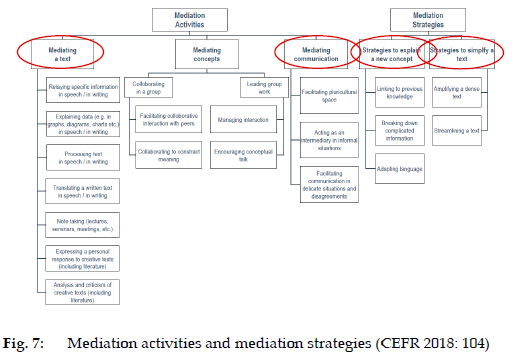

In the CEFR 2018 mediation is differentiated into mediation activities and mediation strategies. Mediation activities are further subdivided into mediating a text, mediating concepts and mediating communication.

Of particular concern to the lexicographer as a mediator are mediating a text, mediating communication, and effectively using mediation strategies while describing the meaning of cultural items.

Mediating a text involves passing on to another person the content of a text to which they do not have access, often because of linguistic, cultural, semantic, or technical barriers. […] Mediating communication: The aim of mediating communication is to facilitate understanding and to shape successful communication between users/learners who may have individual, sociocultural, sociolinguistic or intellectual differences in standpoint (CEFR 2018: 106).

When mediating a text, especially relaying a text in speech or in writing, selection is fundamental. The mediator has to decide on the specific content of the source text which has to be conveyed to somebody else. The mediator - and this is also valid when preparing a lexicographic article - must first select from the vast volume of information available and then transfer it to the target person in a more condensed but still truthful/accurate form.

By Mediating communication, the authors of the CEFR intend mediators to facilitate the understanding of other people's needs and previous knowledge and they expect the capacity to switch from their own perspective to that of the other, keeping both perspectives in mind and facilitating the communication. Mediators, therefore, need to have a well-developed emotional intelligence and empathy for the viewpoints and emotional states of other participants. They have to show interest in understanding cultural norms, demonstrate sensitivity and respect for different sociolinguistic and sociocultural points of view, and anticipate misunderstandings which could arise because of the differences (CEFR 2018: 122).

Especially with regard to cross-linguistic mediation, being a good mediator includes social and cultural competence, as well as plurilingual competence. (CEFR 2018: 106) Plurilingual competence involves the ability to call flexibly upon an inter-related, uneven, plurilinguistic repertoire to:

- switch from one language or dialect (or variety) to another;

- express oneself in one language (or dialect, or variety) and understand a person speaking another;

- call upon the knowledge of a number of languages (or dialects, or varieties) to make sense of a text;

- recognise words from a common international store in a new guise;

- mediate between individuals with no common language (or dialect, or variety), even with only a slight knowledge oneself;

- bring the whole of one's linguistic equipment into play, experimenting with alternative forms of expression;

- exploit paralinguistics (mime, gesture, facial expression, etc.) (CEFR 2018: 28).

The mediator's task - as well as the lexicographer's, especially in describing cultural items - is to facilitate pluricultural space:

Rather than simply building on his/her pluricultural repertoire to gain acceptance and to enhance his own mission or message […], he/she is engaged as a cultural mediator: creating a neutral, trusted, shared 'space' in order to enhance the communication between others. He/she aims to expand and deepen intercultural understanding between participants in order to avoid and/or overcome any potential communication difficulties arising from contrasting cultural viewpoints. Naturally, the mediator him/herself needs a continually developing awareness of sociocultural and sociolinguistic differences affecting cross-cultural communication (CEFR 2018: 122).

To be able to realise this goal, the mediator should resort to various communication strategies in a mediation situation. To explain new concepts and meanings s/he should link to previous knowledge ("[…] introduce complex concepts (e.g. scientific notions) by providing extended definitions and explanations which draw upon assumed previous knowledge") (ibid.: 128)", break down complicated information ("[…] facilitate understanding of a complex issue by explaining the relationship of parts to the whole and encourage different ways of approaching it") (ibid.), and adapt their language ("[…] adapt the language of a very wide range of texts in order to present the main content in a register and degree of sophistication and detail appropriate to the audience concerned") (ibid.). For the simplification of a text it is necessary to amplify a dense text ("[…] elucidate the information given in texts on complex academic or professional topics by elaborating and exemplifying"), and to streamline a text ("[…] redraft a complex source text, improving coherence, cohesion and the flow of an argument, whilst removing sections unnecessary for its purpose") (ibid.: 129).

By acquiring a decent level of intercultural competence, using mediation and applying mediation strategies, the lexicographer will not only be able to select an important cultural item for the (bilingual/plurilingual) dictionary but also adequately present it. In this way the lexicographer will become a successful mediator between cultures.

The importance of cultural knowledge, intercultural awareness, and the consideration of mediation as an activity and strategy for adequately presenting lemmas in bilingual dictionaries was already noted by Robert Morrison for the compilation of the first English-Chinese dictionary in 1815. It would be important to bring these issues back into focus in lexicography and in the training of lexicographers.

The way Morrison positioned himself as a bilingual lexicographer between two very different languages and their associated cultures, which had very little contact and interaction prior to his task of dictionary compilation, was significant. His dictionary entries, illustrative examples, and detailed explanations went beyond typical bilingual lexicography. His efforts were more an experience in intercultural mediation than merely giving lexical equivalents. He ensured the provision of detailed cultural and contextual explanations of the Chinese language, making the language and associated culture accessible to a Western readership wishing to learn Chinese and understand its culture through his text. Morrison sought not only to enhance the understanding of his English equivalents through providing additional illustrative phrases, he also relied on an additional strategy in trying to mediate his understanding of the culturally embedded nature of the meanings he applied to characters and words included in his dictionary. He provided additional, non-linguistic cultural information through explanatory notes, which quoted or described information drawn from original Chinese works, from the Chinese classics, popular literature, and contemporary official notices that reflected the philosophy, values, social systems, and everyday experiences of Chinese, as expressed through language. His inclusion of illustrative examples, commentaries, and explanations went far beyond the work of traditional bilingual lexicography and provided extensive insights into the world of Chinese culture through language, in a manner described as a culture-oriented approach […] to dictionary compilation. (Scrimgeour 2016: 444-445)

As we have seen, this historical reference indicates that the recognition of cultural knowledge in dictionary compilation dates back to at least 1815, emphasizing the enduring importance of these considerations in lexicography and lexicographer training. Lexicographers have to mediate communication. They have - like mediators - to bridge linguistic and cultural gaps, facilitating communication. They have to be able to convey nuanced meaning, with sensitivity and respect for different sociolinguistic and sociocultural points of view, with emotional intelligence and empathy, with the target user in mind, who do not have a direct access to the culture and the various culture-bound items described by the lexicographer. With their plurilingual competence, cultural knowledge, and intercultural awareness lexicographers have to facilitate pluricultural space. To achieve the goal, lexicographers should resort to various communication strategies, just as mediators do, i.e. link to previous knowledge, adapt their language, explain in clear words the cultural information, all this to create understanding of specific cultural information and to guarantee a successful interpersonal and intergroup communication.

Endnotes

1 „[…] Identitätsträger eines nationalen/ethnischen Gebildes, einer nationalen/ethnischen Kultur - im weitesten Sinne - und werden einem Land, einer Region, einem Erdteil zugeordnet." (Markstein 1998: 288)

2 „kulturellen Inkongruenz" (Stolze 1999: 224)

3 "Basandosi sugli studi teorici di Molina Martínez (2006) e Luque Nadal (2009) e combinando le diverse sfumature che assume questo concetto, possiamo fornire la seguente definizione per la metalessicografia contrastiva: la parola culutrale è il termine o l'espressione che potrebbe far parte di un articolo lessicografico, il cui contenuto culturale, semantico o pragmatico appartiene a una lingua determinata e il cui trattamento dipende dal rapporto interculturale fra le lingue messe a contatto. La constraitivtà, cioè il rapporto esistente fra due sistemi linguistici messi a confronto, determina il modo di gestire i contenuti all'interno della traduzione o dell'articolo lessicografico." (Sanmarco Bande 2017: 292)

4 "Il metodo più efficace nel trattamento delle parole culturali non solo deve offrire il traducente più vicino al termine della lingua di partenza, ma concerne tutta la microstruttura, con la combinazione di diverse strategie: chiarimenti fra parentesi, numerose etichette linguistiche, esempi chiari e ben contestualizzati, osservazioni di tipo semantico, culturale e pragmatico, tutto ciò rafforzato da una tipografia mirata a questo scopo. È necessario continuare a rafforzare il traducente con altre parti della microstruttura, perché senza il sostegno di questi strumenti è molto probabile che l'utente interpreti sbagliatamente le informazioni fornite all'interno dell'articolo." (Sanmarco Bande 2017: 303)

5 "Kulturspezifika sind kulturell geprägte Wörter, typisch für eine bestimmte Kultur, die weder ein sprachliches noch ein kulturelles Äquivalent in einer anderen Sprache haben. […] (Nied Curcio 2020: 186)

6 "Als Kulturwörter werden kulturell geprägte Wörter bezeichnet, die typisch für mehrere (mindestens zwei) Kulturen sind, und aus diesem Grund dafür sprachliche Äquivalente in der anderen Sprache existieren. Die Entsprechung gilt jedoch nicht auf der kulturellen Ebene; die kulturelle Divergenz ist ohne interkulturelle Kompetenz auf den ersten Blick nicht erkennbar. Es kann sich dabei auch um einen Internationalismus handeln […] oder/und um sog. Falsche Freunde […]." (Nied Curcio 2020: 186-187)

7 https://de.pons.com/%C3%BCbersetzung/deutsch-italienisch/Kaffee

8 https://dict.leo.org/italienisch-deutsch/Kaffee

9 For a more detailed description cf. Nied Curcio 2020.

References

A. Dictionaries

Giacoma Kolb 2019 = Giacoma, Luisa and Susanne Kolb. 2019. Il nuovo dizionario di Tedesco. Dizionario Tedesco-Italiano / Italiano-Tedesco. Das Großwörterbuch Deutsch-Italienisch / Italienisch-Deutsch. Fourth edition. Bologna/Stuttgart: Zanichelli PONS. [ Links ]

LEO = https://www.leo.org/englisch-deutsch (Accessed 15 January 2023.)

PONS = https://de.pons.com/ (Accessed 15 January 2023.)

Verdiani 2010 = Verdiani, Silvia. 2010. Tedesco Junior. Dizionario di apprendimento della lingua tedesca. Tedesco Italiano - Italiano Tedesco. Torino: Loescher. [ Links ]

B. Other literature

Council of Europe. 2018. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Companion Volume with New Descriptors. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. https://rm.coe.int/cefr-companion-volume-with-new-descriptors-2018/1680787989 (Accessed 21 December 2022. [ Links ])

Gudykunst, William B. and Stella Ting-Toomey. 1988. Culture and Affective Communication. American Behavioral Scientist 31(3): 384-400. https://doi.org/10.1177/000276488031003009 [ Links ]

Luque Nadal, Lucía. 2009. Los culturemas: ¿unidades lingüísticas, ideológicas o culturales? Language Design 11: 93-120. http://elies.rediris.es/Language_Design/LD11/LD11-05-Lucia.pdf (Accessed 15 January 2023. [ Links ])

Marco, Josep. 2019. The Translation of Food-related Culture-specific Items in the Valencian Corpus of Translated Literature (COVALT) Corpus: A Study of Techniques and Factors. Perspectives 27(1): 20-41.DOI:10.1080/0907676X.2018.1449228 (Accessed 21 December 2022. [ Links ])

Markstein, Elisabeth. 1998. Realia. Snell-Hornby, Mary, Hans G. Hönig, Paul Kußmaul and Peter A. Schmitt (Eds.). 1998. Handbuch Translation: 288-291. Tübingen: Stauffenberg. [ Links ]

Molina Martínez, Lucía. 2006. El otoño del pingüino. Análisis descriptivo de la traducción de los culturemas. Castelló de la Plana: Publicacións de la Universitat Jaume I. [ Links ]

Newmark, Peter. 1988. A Textbook of Translation. London: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Nied Curcio, Martina. 2020. Kulturell geprägte Wörter zwischen sprachlicher Äquivalenz und kultureller Kompetenz. Am Beispiel deutsch-italienischer Wörterbücher. Lexicographica 36: 181-204. [ Links ]

Persson, Ulrika. 2015: Culture-specific Items. Translation Procedures for a Text about Australian and New Zealand Children's Literature. MA Thesis. Växjö: Linnaeus University, Sweden.http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:850704/FULLTEXT01.pdf (Accessed 21 December 2022. [ Links ])

Sanmarco Bande, María Teresa. 2017. Le parole culturali della gastronomia nella lessicografia italospagnola odierna. Bajini, Irina, M.V. Calvi, G. Garzone and G. Sergio (Eds.). 2017. Parole per mangiare. Discorsi e culture del cibo: 289-306. Milan: LED. [ Links ]

Scrimgeour, Andrew. 2016. Between Lexicography and Intercultural Mediation: Linguistic and Cultural Challenges in Developing the First Chinese-English Dictionary. Perspectives 24(3): 444-457.DOI: 10.1080/0907676X.2015.1069859 (Accessed 21 December 2022. [ Links ])

Stolze, Radegundis. 1999. Die Fachübersetzung. Eine Einführung. Tübingen: Narr. [ Links ]