Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Lexikos

On-line version ISSN 2224-0039

Print version ISSN 1684-4904

Lexikos vol.33 Stellenbosch 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.5788/33-1-1826

ARTICLES

A Necessary Redefinition of Lexicography in the Digital Age: Glossography, Dictionography and Implications for the Future

'n Noodsaaklike herdefiniëring van leksikografie in die digitale era: Glossografie, woordegrafie en implikasies vir die toekoms

Sven TarpI; Rufus H. GouwsII

IDepartment of Afrikaans and Dutch, Stellenbosch University, South Africa; Centre of Excellence in Language Technology, Ordbogen A/S, Denmark.; Centre for Lexicographical Studies, Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, China; and Centre for Lexicography, University of Aarhus, Denmark (st@cc.au.dk)

IIDepartment of Afrikaans and Dutch, Stellenbosch University, South Africa (rhg@sun.ac.za)

ABSTRACT

This paper deals with developments in the field of lexicography that resulted in the need for a new definition of this term. The paper offers a brief look at the origin, use and development of the term lexicography and at the use of glosses in former and current times. It is shown how the digital era enables the use of certain lexicographical features in other sources than dictionaries. This leads to an expansion of the scope of the term lexicography. A strong focus is on the use of glosses, originally inserted by scribes as snippets into manuscripts to help with the understanding of difficult words and expressions. The use of glosses has increased, and they are currently commonly used in a variety of environments. In digital products glosses play an innovative, productive and significant role to present new types of lexicographical data. This demands the recognition of glosses as lexicographical entries and leads to a redefinition of the term lexicography that includes two major sub-fields, namely dictionography and glossography.

Keywords: artificial intelligence, digital era, gloss, glossography, lexicographical data, scribe, dictionography, interdisciplinary collaboration, reading assistant, writing assistant

OPSOMMING

Hierdie artikel handel oor ontwikkelinge in die veld van leksikografie wat gelei het tot die behoefte aan 'n nuwe definisie vir hierdie term. Dit bied 'n blik op die herkoms, gebruik en ontwikkeling van die term leksikografie en die gebruik van glosse in die verlede en tans. Daar word gewys hoe die digitale era die gebruik van bepaalde leksikografiese kenmerke in ander bronne as woordeboeke moontlik maak. Dit lei tot 'n uitbreiding van die bestek van die term leksikografie. Daar is 'n sterk fokus op die gebruik van glosse wat oorspronklik deur skriptore as brokkies in manuskripte gevoeg is om te help met 'n beter begrip van moeilike woorde en uitdrukkings. Die gebruik van glosse het toege-neem en word tans algemeen gebruik in 'n verskeidenheid omgewings. In digitale produkte speel glosse 'n vernuwende, produktiewe en belangrike rol om nuwe tipes leksikografiese data aan te bied. Dit vereis die erkenning van glosse as leksikografiese inskrywings en lei tot 'n hedefiniëring van die term leksikografie wat twee hoofafdelings insluit, te wete woordegrafie en glossografie.

Sleutelwoorde: kunsmatige intelligensie, digitale era, glos, glossografie, leksikografiese data, skriptor, woordegrafie, interdissiplinêre samewer-king, leeshulp, skryfhulp

0. Introduction

Lexicography as a cultural practice dates back at least to the 24th century BCE, when the Sumerian-Akkadian glossary known as Urra-Hubullu was carved on clay tablets, believed to be the first work of its kind in the world. With the term lexicography coined much later, the discipline has developed in both breadth and depth over the past 4300 years, with dictionaries covering virtually all the world's languages and countless aspects of human life in terms of knowledge, arts, crafts and other pursuits, making them one of the most successful man-made products ever. At the same time, its various expressions have undergone profound changes, not only as a result of accumulated experience, but also due to periodic technological innovations that have affected the preparation, presentation and use of the finished product. Suffice it to mention the evolution from clay tablets, through bamboo strips, papyrus scrolls, handwritten and printed paper books, to today's digital platforms. And the same can be said of the evolution of its production tools, from styluses to pens, typewriters, computers and, most recently, artificial intelligence, to name but a few.

All this has influenced the way lexicographers work and, over time, has greatly changed the way they carry out their tasks and relate to the empirical material, the compilation tools, the presentation of the final product, as well as to its users. In particular, the digital revolution that began at the end of the last century has been a major driver of this development. It is therefore quite natural that Grefenstette (1998), looking forward another 1000 years, formulated the following question in the title of the paper he presented at the Euralex Congress in the same year:

Will there be lexicographers in the year 3000?

It was Rundell (2012: 18) who took up the gauntlet and gave an answer that was as optimistic as it was challenging:

There will still be lexicographers, but they will no longer do the same job.

What will they do then? That's the question! And it might be added that not only will they not be doing the same work, they will also be making very different products, although this does not mean that dictionaries of some kind will not continue to exist, at least for the time being.

This article will not speculate and try to guess what lexicography will look like in the year 3000. But its authors are convinced that current technological breakthroughs, particularly in the field of artificial intelligence, will have a huge impact on the discipline in the coming years, as can be seen both in the recent adoption of chatbots in the lexicographic compilation process and in the increasing integration of lexicographical data into AI-based language models and the creation of entirely new products.

This development requires lexicographers to adapt, as must the discipline itself. In this perspective, there is an urgent need to redefine the very term lexicography and to bring it into line with actual practice, taking into account both history and current challenges.

The following sections will deal exclusively with lexicography in a European context, from its origins in ancient Greece up to the present day. Section 1 gives a brief overview of how the subject matter of lexicography has been defined in dictionaries and scholarly literature until now, and Section 2 then reflects on the origin and development of this term. Section 3 traces the use and development of glosses from antiquity to the present day, with special focus on the period after the introduction of printing technology, especially on the more recent use. Section 4 then briefly discusses what seems to be the rebirth of glosses in the digital age, while the following section provides some examples of how lexicographical data are used in AI-driven writing assistants. Finally, Section 6 attempts a redefinition of lexicography based on the findings and arguments of the previous sections.

1. Definitions of the term lexicography until now

When attempting a redefinition of the term lexicography it is necessary first to take cognizance of the meaning traditionally associated with this term. This can be found in definitions in general dictionaries, but also in sources beyond these dictionaries. Bergenholtz and Gouws (2012: 32) indicate that the use of the term lexicography shows many differences in its interpretation and there is a variety of perspectives on the nature, extent and scope of this term within the broader lexicographical and metalexicographical field.

The typical definition of the term lexicography in general dictionaries includes a reference to the making, compiling or writing of dictionaries, as seen in the following definitions from the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English and the The New Oxford Dictionary of English, respectively:

The writing and making of dictionaries

the practice of compiling dictionaries

Some dictionaries do present a second sense that provides for something more than the practice of writing dictionaries. This is seen in the Webster's Ninth Collegiate Dictionary that has two senses for the term lexicography:

1: The editing or making of a dictionary. 2: the principles and practices of dictionary making.

These principles referred to in the second sense remain undefined, the focus remains on dictionaries and no mention is made of a formal theoretical component. Even in dictionaries dealing with special fields, the theoretical component of lexicography is not always acknowledged. In the Wörterbuch zur Lexikographie und Wörterbuchforschung, the brief tautological definition of lexicography makes no reference to a theoretical component:

total of all activities directed at the preparation of a lexicographic reference work.

A significant aspect of this definition is that it does not specifically link lexicography to dictionaries, but rather to the broader concept of lexicographical reference work, which includes, among others, dictionaries, encyclopaedias, thesauri, lexicons and glossaries.

Explicit reference to the theoretical component of lexicography can be found in the definition given in a specialized dictionary dealing with the discipline itself, namely the Dictionary of Lexicography. This source defines lexicography as:

The professional activity and academic field concerned with DICTIONARIES and other reference works. It has two basic divisions: lexicographic practice, or dictionary-making, and lexicographic theory, or dictionary research. ...

Important here is the reference not only to dictionaries but also to other reference works in general.

Scholarly publications in the field of lexicography do not always acknowledge the scientific nature of theoretical lexicography, for example in the title of Dictionaries: The Art and Craft of Lexicography (Landau 1984), which does not indicate that lexicography is a scientific field or that the compilation of dictionaries may have a scientific or a theoretical basis. However, the recognition of a theoretical component of lexicography does come to the fore more strongly in other scientific publications from this field. Wiegand (1998: 41), when discussing general language dictionaries, distinguishes between a non-scientific and a scientific form of lexicography. He regards scientific lexicography as an independent cultural and scientific practice that is directed at the production of language reference works and these products should enable the establishment of another cultural practice, namely the use of these reference works. Although he only refers to "language dictionaries" the term lexicography also includes all other types of dictionaries - as shown in subsequent sections of this paper. In addition to the practice of using dictionaries Wiegand (1998: 46) makes provision for theoretical lexicography when stating that lexicography is the subject matter domain from which the different research areas of dictionary research develop.

It is worthwhile noting that for Wiegand lexicography has to do with reference works and not specifically with dictionaries.

From the different ways in which the term lexicography has been defined one can deduce that a default understanding of the term lexicography makes provision for two types, namely:

(1) The planning and compilation of concrete dictionaries and other reference works. This part of lexicography is known as practical lexicography or the lexicographical practice.

(2) The development of theories about and the conceptualisation of dictionaries and other reference works. This part of lexicography is known as meta-lexicography or theoretical lexicography.

The focus in the majority of the above-mentioned definitions has been on the making, compilation and editing of dictionaries, but not on the presentation of dictionaries or on dictionaries as such. A more directed focus on dictionaries (and other reference works) is found in Tarp (2018: 19) when he defines lexicography as:

the discipline that deals with dictionaries and other reference works designed to be consulted in order to retrieve information.

Lexicography deals with dictionaries but not only with dictionaries and not only with dictionaries that have been planned and compiled in a traditional way and, as we will see, something essential has been forgotten in previous definitions of this field. Consequently, a more comprehensive interpretation of this term is needed. Currently other products like some writing assistants, reading assistants and learning apps also display certain lexicographical features, cf. Tarp (2020), Huang and Tarp (2021) and Nomdedeu-Rull and Tarp (2024). This needs to be accounted for in a definition of lexicography. Once again lexicography faces a transition that can drastically influence the nature of the term.

Lexicography is increasingly dealing with products other than dictionaries - something omitted in the discussion of e.g. Bergenholtz and Gouws (2012) and Tarp (2018). The definition of the term lexicography needs to explicitly acknowledge these other products as being part of a lexicographic practice. When defining the term lexicography, it could be helpful to distinguish between a dictionary perspective and a non-dictionary perspective. The first perspective will lead to a focus on the traditional lexicographic products, in printed and digital format, like dictionaries, glossaries, thesauri, lexicons, encyclopaedias, and so on. This component of lexicography can be described with the term dictionography. The second component, focusing on other products, will be discussed in subsequent sections of this article.

2. Origin and development of the term lexicography

European lexicography was born and began to develop more than two thousand years ago in ancient Greece, as reported by McArthur (1986) and Stathi (2006), among others. It is therefore appropriate that the term commonly used in the different European languages to describe the discipline defined in the previous section has its etymological roots in the classical Greek language. The term is composed of the two words léxis and gráphein, meaning "word" and "to write", respectively. This suggests that lexicography originally meant "writing about words".

The term lexicography was introduced into the Western European tradition in the seventeenth century, but it is an open question whether it was already used, at least orally, as early as Classical Greece, for example in the world-famous Library of Alexandria, whose scholars were the first in the European tradition to compile glossaries, the prototypes of later dictionaries.

In any case, the original meaning of a word, however important, does not necessarily reflect its meaning in later periods, since words, like everything else, are subject to the laws of evolution and change. According to current knowledge (see Hanks 2013), what we now call European lexicography dates back to the fifth century BCE, when Greek scribes began inserting glosses into manuscript copies of texts by Homer and other classical authors to explain rare or obsolete words to the readers of the time. This writing about the words was, of course, lexicography in the original sense of the word, even if the term was not yet in use. It is only later, when the scholars of the Library of Alexandria began to compile the glosses into glossaries, that the term can reasonably be associated with the compilation of word lists or glossaries.

Initially, glossaries were organised systematically, with words arranged in the order in which they appeared in a given book. In the second century BC, Dionysius Thrax, who worked in the library and wrote the famous Tëkhnë Gram-matikë (Art of Grammar), suggested that they should be arranged alphabetically instead. Although he did not use the term lemma, this scholar is also credited with inventing the concept of a lemma as a headword or form of citation, representing all the inflected forms of the respective words, to be followed by definitions and other data. In this way, he and other scholars of the Hellenistic period helped to standardise the content of glossaries, paving the way for their more sophisticated descendants, the dictionaries.

As a result, and without using modern lexicographical terminology, the ancient Greeks introduced five innovations that revolutionised the discipline: (1) the book form; (2) the lemma; (3) the macrostructure as the arrangement of the lemmas; (4) the article as the set of all the data attached to the lemma; and (5) the microstructure as the arrangement of these data. These five innovations are the key features of the uniquely successful product that evolved into the dictionary as we know it today, and took it from triumph to triumph for the next two thousand years.

Just as the meaning of the term lexicography was narrowed down to primarily refer only to dictionaries, so the meaning of the term dictionary itself changed over time, especially with the introduction of specialised dictionaries, spurred on by the European Renaissance, Enlightenment Age and industrialisation. The dictionary form was simply so successful that it was adopted by subject-field specialists who did not just write about words. From this perspective, the editors of the multi-volume Spanish Diccionario enciclopédico hispano-americano de literature, ciencias y artes (1887-1910: 3-4) explained their choice of structure as follows:

In order for our work to be of truly practical use, it is essential that it should be easy to use, and to achieve this, there is no doubt that the most appropriate form is that of a dictionary, since the alphabetical order is the least likely to surprise people who are not well versed in the difficult matter of the classification of sciences, which is always prone to arbitrary errors.

The large number of dictionaries written in this spirit meant that the term dictionary, which until then had referred to something about language, now included "things and facts", as d'Alembert (1754: 958) astutely noted when he classified these works in a special article in the Great French Encyclopaedia. Although many lexicographers with a linguistic background resisted, this could only mean that the term lexicography, which had previously been narrowed down to refer specifically to dictionaries, was being broadened again to mean not only writing about words, but also about things and facts, i.e. what words refer to.

In all this development, which ended up equating lexicography with dictionaries and other reference works, one thing had been tacitly left out: the glosses. The insertion of glosses in manuscript copies was the starting point not only for classical Greek lexicography, but also for European lexicography in general. Moreover, history repeated itself in several European countries. Thus, the use of glosses in handwritten books was also the trigger for specific national lexicographies such as English and Spanish, as shown by Yong and Peng (2022), and Nomdedeu-Rull and Tarp (2024), respectively. At the same time, glosses, like dictionaries, continued to evolve and find new uses even after manuscript copying of books was abandoned with the introduction of printing in the fifteenth century, as we will discuss in the next section.

3. Use and development of glosses over time

The word gloss can be traced back to the classical Greek word glossa that refers to a difficult word or a word that needs explanation. Where a glossa occurred in a text a brief explanation was added to the text. In the course of time the meaning of the word gloss shifted from referring to a difficult word to the brief explanation of such a word - like the snippets inserted into manuscripts by the scribes. Glosses were entered into texts where a reader of such a text realised that people might have difficulties with the understanding of a specific word or where they could benefit from some form of additional information. Therefore, not all words in a text received a gloss - too many glosses would have been redundant because the readers had no need for an explanation of the meaning of all the words in the text. Glosses were entered on a need to have basis.

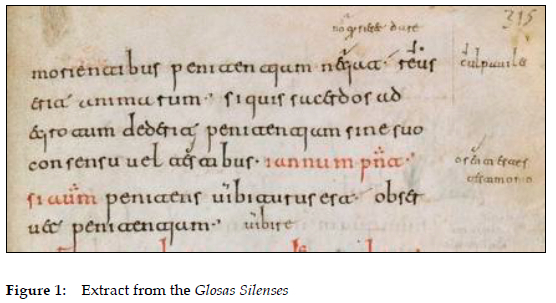

Figure 1 is reproduced from Ruiz-Asencio et al. (2020), which stands out as one of the few systematic studies of glosses in specific medieval works. It shows 4 glosses out of the 369 glosses that appear in the mid-11th century Latin Penitential, known as Glosas Silenses (Silos Glosses). The four glosses (non quisieret dare, vibire, culpauiles and o sen tiestes testimonio) are written in an early Romance language that was in the process of splitting off from vulgar Latin. It is worth noting the four different small signs used to refer the reader from a particular word in the Latin text to the corresponding gloss in the margin.

Glosses in books such as the Glosas Silenses were not only written by the scribes who would hand-copy these books from time to time due to wear and tear. They were also produced by readers, in most cases probably respected monks authorised to do so because of the extremely high value of books at the time. Just like the scribes, these new players responded to something in the text, for example to clarify some confusing concept. However, if too many glosses were inserted on a single page, it was difficult for the reader to link a specific gloss to the appropriate glossed word or expression. Consequently, the writers of glosses started to include signs, as can be seen in Figure 1, to help readers to connect a gloss to a specific word or expression. These were functional signs and nothing less than a prelude to the numbers, letters and other signs used much later to assign footnotes to particular words and phrases in a text.

As Tarp and Gouws (2019) have shown, the tradition of inserting glosses into written texts survived the introduction of printing in the late 15 th century and found a number of new expressions. But the key players were different. Now it was either the authors themselves who introduced them into their books and articles, or it was the editors, especially when publishing later editions that needed additional clarification on meaning or other matters, thus performing a task very similar to that of the classical Greek scribes more than two thousand years ago. By contrast, the readers of these texts now only added comments for their own personal use. In this respect, and according to Kennedy (2019), since the late 16th-century glosses were moved from the margins of texts to a designated place at the bottom of a page. Here they were entered as footnotes and assigned a number or sign corresponding to the number or sign entered next to a word or expression in the main text. This improved the organisation of the page layout and in the course of time such footnotes were often populated by glosses commenting on specific words and expressions in the text.

Today glosses are employed in different types of texts and different genres, including dictionaries. However, the most prolific use of glosses is found in non-lexicographic work where they are entered to provide assistance in, especially, a better comprehension of an unknown or foreign word. As Tarp and Gouws (2019) show, glosses are also presented in different forms, including their occurrence in footnotes.

Traditionally glosses were used in Greek and Latin texts, also texts of a religious nature. Even today in some editions of The Bible, glosses are still used to comment on a word or expression, or a thing referred to in the text. These glosses are usually not inserted as an annotation next to the word at which it is directed. Adhering to the principle applied in the Glosas Silenses and continued in the footnote approach, the user is directed from the glossed word or expression to a gloss accommodated elsewhere in the text - not in such close proximity as in the Glosas Silenses but rather in a footnote at the bottom of the page. Where a marker in the Glosas Silenses was a link to an entry in the margin that contained additional data, the footnote marker, usually a number, letter or symbol, in more recent publications makes the user aware of the fact that additional data are provided and can be found in the footnote introduced by that specific marker. The Nuwe Testament en Psalms: 'n Direkte vertaling (2014), one of the Afrikaans translations of the New Testament of The Bible, frequently enters glosses in footnotes. In this publication Psalm 63 commences as follows:

63 'n Psalm van Dawid. Toe hy in die woestynh van Juda was. ...

(63 A psalm of David when he was in the deserth of Juda)

The word woestyn (desert) is followed by the superscript "h". At the bottom of the page a footnote, introduced by the letter "h", accommodates the following gloss:

h woestyn Dit verwys na 'n onbewoonde, onherbergsame gebied waar skape en bokke soms gewei het.

(h desert It refers to an uninhabited, barren area where sheep and goats sometimes graze.)

Here the glossed word from the main text is repeated and functions as "lemma" of the gloss. The gloss is provided so that the reader does not have to rely on external sources for a better understanding of the meaning of the word. This enhances an uninterrupted reading of the text.

The system of footnotes is often used in modern-day publications to accommodate additional data. The user is referred by means of a footnote marker in the main text to the footnote section where the relevant gloss can be found.

Scientific textbooks utilise this form of glossing. Prins (2003), a book from the field of theoretical physics, frequently uses footnotes and often these footnotes contain glosses, as can be seen in Prins (2003: 132) where the text contains the sentence:

In terms of the latter concept, a light-quantum** collides 'like a particle' with an electron ...

The word light-quantum gets a footnote marker ("**") and in the footnote section the following gloss explains an aspect of the meaning of this expression:

** At present a light quantum is known as a photon.

This is additional data that the author considers relevant to the readers of the book in order to improve their knowledge of the subject field and to anchor the meaning of the term to the time of writing.

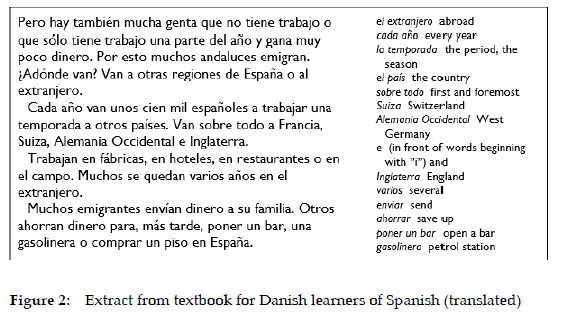

In Hâkanson et al. (1977: 42-43), a textbook for Danish learners of Spanish, glosses are placed together in a box (without frames) somewhere on the page. As seen in Figure 2, instead of numbers, letters and signs, the marker introducing the gloss is the word to be explained itself.

Here the gloss box represents a mini-glossary, a kind of transitional form between "pure" glosses and glossaries structured according to the order in which the words to be explained appear in the text.

Glosses are also presented in other forms. Sintaksis vir eerstejaars (Du Plessis 1982), a textbook on Afrikaans syntax, uses interlinear glosses, presented between two horizontal parallel lines, to provide additional data in order to expand on a preceding word or statement or to emphasise some aspect of that word or statement. In a section discussing the verb phrase in Afrikaans (Du Plessis 1982: 66) the following is found (translated from the Afrikaans):

If we look at the similarity it is noticeable that just as the phrase NP cannot function without the core N, no VP can exist without the element verb (V)

A VP must in all circumstances contain a verb in the basic sentence.

Verbs display group-forming possibilities, this is where the similarities between the VP and the NP stop.

This gloss, given between two vertical lines to separate it from the surrounding text, does not explain the meaning but emphasises a statement made in the preceding sentence. Here the gloss has a didactic purpose, a tradition that can also be traced back to a class of medieval glosses that did not explain the meaning as such, but rather interpreted the text and helped the reader to grasp the message.

Supplementing the references made in Tarp and Gouws (2019) it is interesting to note a further widespread use of glosses. As indicated in Tarp and Gouws (2019) menus often contain glosses to provide a better understanding of a word referring to a specific dish. A dish on the menu of a restaurant is vaguely indicated as The Chicken. Because guests will not know what to expect, this entry is immediately followed by the gloss:

Oven-roasted free-range chicken supreme with chargrilled artichokes, blistered tomatoes, fennel, mangetout, stone fruit & chorizo.

Glosses also occur in popular publications like recipe books. Top 500+ Wenre-septe 2 (Niehaus 2013), a well-known Afrikaans recipe book, uses glosses to complement the recipes. This information is not part of the recipe, and one does not have to follow the advice given there. These glosses are presented in a text box positioned at the end of a recipe and are introduced by the word Wenk (=Tip). These tips contain different types of data. The recipe for butternut soup has the tip "Die sop vries goed" (The soup deep-freezes well), whereas the recipe for rusks has the gloss "Jy kan die botter met margarien of olie vervang." (You can substitute the butter with margarine or oil.) The glossing is presented in such a way that the user can ignore the entry but can gain some additional guidance that could be of assistance when making the dish given in the recipe.

The preceding discussion shows that glosses are alive and well - and are living in different types of printed texts. Where dictionaries typically provide a variety of data types in their treatment of a word, a gloss by definition presents a limited treatment, in its origin mostly an explanation of the meaning of a word, but later also of "things and facts" needed in a particular context. This frequent occurrence of glosses demands a term to refer to this kind of activity.

While the term dictionography, defined in Section 1, was coined by the authors, glossography, the other term included in the title of this article, already exists. It usually refers both to the practice of preparing and inserting glosses into texts and to the compilation of glossaries. Here, however, it refers only to the former, while the compilation of glossaries is included under dictionography, since the development from glosses to glossaries to dictionaries can be seen as a continuum with no clear dividing lines.

4. Return of glosses in digital tools

It may seem paradoxical that something as old as the insertion of glosses into books, developed long before the advent of printing and largely ignored by lexicographers for centuries, could find new life and relevance at the time of the greatest technological paradigm shift in human history. Yet that is exactly what is happening today. An uneasy love affair between an ancient technique and modern software is unfolding before our eyes, fusing tradition and innovation. It is making its way into digital reading and writing assistants, where lexicographers and designers are constantly caught between doing business as usual and thinking out of the box to interpret user needs as they manifest in the new digital environment.

Digital reading assistants are defined here as all types of software designed to help readers who have difficulty understanding digital texts. As such, it includes both different types of digital dictionaries and other classes of lexicographical data provided for this purpose. While users may have different needs when reading, the predominant need in such a situation will undoubtedly be an explanation of unfamiliar words and phrases. The default solution in such cases should therefore be as short a definition as possible, or simply an equivalent in the users' native language, so as not to disrupt their reading flow and take their focus away from the text. Additional types of lexicographical data could only be disruptive in this particular situation and would constitute what Gouws and Tarp (2017: 408) describe as "relative data overload". For those users who need more information, they could easily access the relevant data if a "more" button was installed to enable this action.

As Tarp (2022) and others have shown, the problem with using current dictionaries, including those that are integrated into texts and can be activated with a single click, is that traditional dictionary articles are uploaded by default. These articles usually contain too many data that are irrelevant in the specific situation. Even if only the definitions of the senses are listed, there are often five, ten or more that the user must go through to find the right meaning. Both solutions represent business as usual.

In reality, only one default definition is needed in each lookup, the one that explains the meaning in the concrete context. How to solve this requires thinking outside the box. One solution could be to create AI-based software that can determine the specific meaning of each word or expression, as suggested by Bothma and Gouws (2022). This is undoubtedly a solution of the future. However, as it is likely to take some time to develop such a product, it is interesting to see how some text producers and publishers are starting to take matters into their own hands and provide modern glosses to their users. One such example is the news section of the Danish National Television website.

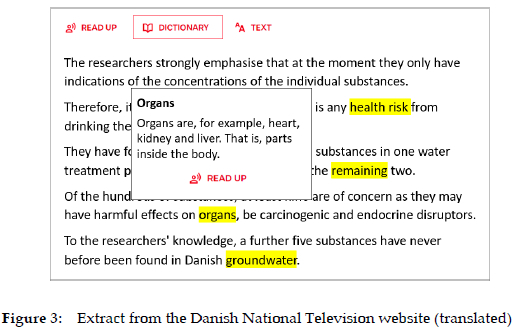

Figure 3 shows the somewhat clumsy English machine translation of an article from the Danish website. When the reader activates what is called Dictionary (Word explanation would be more appropriate), a number of words in the text are highlighted. Clicking on one of these words immediately displays a box with a Collins Cobuild-like definition. The "lemma" Organs is completely redundant as the word is already highlighted in the text. If it is removed, all that is left is a traditional gloss, no more, no less. In this way, the five key features of traditional dictionaries mentioned in Section 2 have disappeared altogether. The method is also similar to that of the ancient scribes, in that only those words that are considered difficult for the reader are commented on. What is new under the sun, however, is that the latest technology allows the glosses to appear only when the reader needs them to understand a word, as opposed to the old days when they were always there, sometimes disturbing the reader as an early expression of data overload.

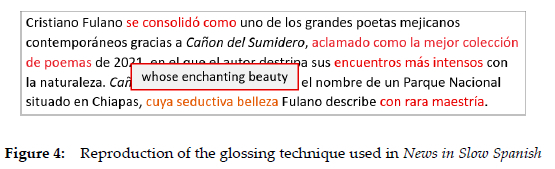

Other publishers, such as those producing learning applications and language courses, also seem to feel a spontaneous need to provide glosses to help their readers. One example is the online Spanish language course for English speakers News in Slow Spanish, which offers Spanish news articles to learners at three levels: beginner, intermediate and advanced. In this language course, words and word sequences that are considered to be difficult for users to understand are highlighted in the text and then explained, as in the case of the Danish website mentioned above. The publishers seem to have little knowledge of traditional lexicography, as they do not offer conventional definitions, but direct and presumably automatic translations, which are provided in a rectangular box immediately above the highlighted words and sequences (see Figure 4). Although some of these translations may seem awkward, they work - at least to some extent - and demonstrate the technological possibilities of breathing new life and content into the glosses to meet the perceived needs of learners and other potential users.

Of course, the technique and presentation in Figure 4 could be more elegant, for example by avoiding arbitrary sequences and highlighting only single words and extended units of meaning, as defined by Rundell (2018). Since the target audience is learners who may want additional information about the respective words and units, it would also be appropriate to allow them to click through to more detailed data from a lexicographical database, as recommended by Huang and Tarp (2021). Something similar has been suggested by Fuertes-Olivera and Tarp (2020) for lexicography-assisted writing assistants. Be that as it may, Figures 3 and 4 are evidence that the need for glosses in the digital world is real and more or less spontaneously understood by different stakeholders.

The ball is now in the lexicographers' court. It is now up to them to adapt their databases if they want to follow the route of this new normal, while at the same time engaging in interdisciplinary collaboration with designers to achieve the most appropriate presentation. This could also involve the development of special software that allows text producers to highlight the words and extended units of meaning they want to explain in a text and then upload the necessary data from a lexicographical database, as suggested by Nomdedeu-Rull and Tarp (2024).

5. New role of lexicography

As Rundell (2012) has predicted, future lexicographers will not do the same as their colleagues have done until now. In the previous sections, we have already seen how recent technological developments suggest that they should shift their focus from dictionaries to databases containing both new and old types of lexicographical data that can serve various tools, including but not limited to digital dictionaries.

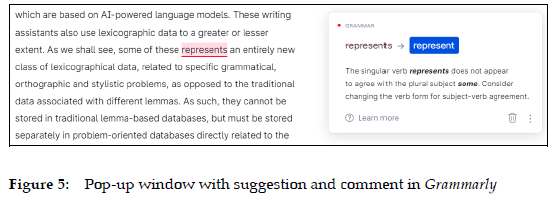

Among the tools already introduced and currently under rapid development are digital writing assistants such as DeepL Write, Ginger, Grammarly, LanguageTool and ProWritingAid, which are based on AI-powered language models. These writing assistants also use lexicographical data to a greater or lesser extent, both for internal training and communication purposes and for external presentation to their users. As we shall see, some of these represent an entirely new category of lexicographical data, related to specific types of grammatical, orthographic and stylistic problems, as opposed to the more conventional data associated with different lemmas. As such, they cannot be stored in traditional lemma-based databases, but must be accommodated separately in problem-oriented databases directly related to the language model. The methodology for their elaboration is also different. Figure 5 provides an example of this class of data.

When a writing assistant, in this case Grammarly, detects a potential problem in a piece of writing, it draws the user's attention to it by underlining it and giving it a colour that varies according to the severity of the problem. If the user clicks on the highlighted area, a pop-up window immediately opens with an alternative suggestion and an explanatory comment or annotation. With the exception of DeepL Write (at least for now), the other three writing assistants mentioned above employ similar techniques to serve their users.

The suggestions in all of these tools are automatically generated by the underlying AI-driven language model. The annotations, by contrast, are the result of human expertise and an innovative way of writing about the words or vocabulary in the digital environment. As such, they represent a new category of lexicographical data that opens up a whole new field of activity for lexicographers, who, with their time-honoured user-centred approach, seem to be the most appropriate experts to add a communicative task of this sensitive nature to their classical repertoire. This observation is reinforced by the fact that the annotations vary considerably from one writing assistant to another and do not always seem to be of the necessary quality to serve the user group adequately.

Annotations like the one shown in Figure 5 have many similarities with the classical scribes' glosses and the way they prepared and inserted them into texts. As a term with Greek roots, lexicography does not mean describing vocabulary, but writing about it. Just like the ancient scribes, their modern colleagues do not aim to describe the whole vocabulary, but only to write about a part of it. Digital-age scribes, like their predecessors, write about only those words that they think might be a problem for their readers. In this sense, they produce modern glosses, adapted to the new reality, to be inserted into texts to assist their users.

The main difference between the traditional glosses discussed in the previous sections and glosses like the one in Figure 5 is that the latter aim to assist writers with text production problems and therefore contain a certain element of recommendation or instruction, whereas the former focus on readers with text reception problems, as well as learners of languages and specific subjects, and are therefore more explanatory. Another difference is that although modern glosses appear in texts related to specific words, in most cases they are not elaborated specifically in relation to these words, but to classes of problems involving several or even many different words. This is why they have to be stored differently from traditional lexicographical data.

In conventional lexicography, including digital lexicography, the work of lexicographers consists not only in selecting lemmas and writing dictionary articles, but also in preparing the necessary empirical material, such as special corpora. The same applies to problem-oriented digital glosses. Before the glosses can be written, the language model has to be trained to identify problems and suggest alternative solutions. This requires different types of empirical training material, the preparation of which can benefit from the input and active participation of lexicographers. For example, in addition to a "traditional" corpus, it may involve the compilation of a special set of parallel corpora from which the language model can learn to distinguish between right and wrong. It may also involve the preparation of validation material to test its performance and determine whether it should be further trained to serve the intended user group.

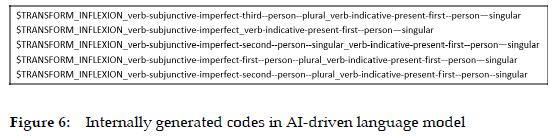

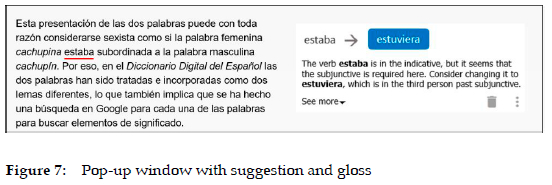

Once the language model has been trained and has reached an acceptable level of performance, it will automatically generate internal codes for each class of problems identified. These codes will number in the thousands and will be the starting point for producing explanatory glosses. Figure 6 shows five such codes taken from the AI-powered language model supporting a Spanish writing assistant for foreign learners currently under development.

It is now the task of the lexicographers to write short glosses and, if necessary, additional explanations, and then to link them to the relevant codes using specially designed software. One of these glosses will then appear in a pop-up window whenever a user clicks on a highlighted area corresponding to its particular type of error, regardless of the specific word to which it relates. Figure 7 shows an example of how this works when a learner has mistakenly used a Spanish verb in the indicative instead of the subjunctive. As can be seen, the writing assistant does not provide a general, one-size-fits-all gloss, but individualises it by inserting the two specific words in question - the appropriate one and the inappropriate one - into the gloss. The general gloss, which serves as a frame for the individualised gloss shown in the figure, can thus be used to comment on thousands of different Spanish verbs and explain the suggested corrections when the same class of grammatical problem occurs.

Working with high-tech tools such as writing assistants is certainly a new and relevant task that more lexicographers will have to take on. However, it requires an open mind and the ability to engage in interdisciplinary collaboration with computer scientists, programmers and designers, since these products are not lexicographical as such, but products with a lexicographical component. It also implies a willingness and ability to embrace the latest technologies, such as the much-discussed chatbots, which will undoubtedly revolutionise lexicographical production in the coming years.

In this respect, Huete-García and Tarp (2024) report that they use chatbots for three different tasks in the aforementioned Spanish writing assistant project. For the first task, which is for internal training purposes only, there is no need to revise the data produced by the chatbot. However, for the second task, also for internal use, the expertise of the lexicographer is essential, as it requires 100% correct data, while for the third task, which involves external data to be presented directly to the end user, human knowledge and creativity are indispensable. The two researchers show how the three tasks represent three completely different types of relationship between the lexicographers and the chatbot and how this AI-based technology significantly increases productivity without reducing its human counterparts to irrelevant extras. On the contrary, it may require even more knowledge, expertise and creativity from lexicographers, both to give relevant and precise instructions that can guide the chatbot to produce data of the desired type and quality, and to evaluate and build on these data.

The quintessence of all this, together with the reflections in the previous sections, is the main reason why the concept of lexicography needs to be redefined, with a definition adapted to actual practice and brought up to date.

6. New definition of the term "lexicography"

As indicated in this paper the term lexicography was introduced much later than many products that today can rightfully be regarded as lexicographical work. In the course of time the term lexicography was predominantly used to refer to the practice of making dictionaries. Although the writing of dictionaries represents a form of writing about words and thus adheres to the original meaning of the word lexicography, dictionaries, as they are known today, are not the only products that fall within the scope of lexicography. The work done by the Greek scribes when they inserted glosses into texts was an early form of lexicography and although not identified as such at that time the current understanding of lexicography acknowledges and includes those products.

The introduction of the printing press was a breakthrough event in many ways - also in lexicography. Although the copying of manuscripts came to an end, the use of glosses to present contextualised data continued, cf. Tarp and Gouws (2019: 253). This use of glosses covered a spectrum of text types and introduced a significant lexicographic feature into these products. However, the insertion of glosses into texts was no longer a specialised craft carried out by scribes and literary monks, but a practice with a wide variety of expressions, in which a large number of different authors and editors of texts engaged. This dilution of the traditional craft is probably the reason why lexicographical research has for a long time overlooked this activity, or simply regarded it as a long-gone precursor of "proper" lexicography, which it associates exclusively with dictionaries and similar reference works.

The digital age, with its diverse text types, has radically changed this situation, allowing for an even more productive use of glosses, which are now also integrated into digital texts, where they can be activated by touching or clicking on the screen. The main players in this new era are publishers and editors of digital books, websites, learning courses, writing assistants, etc. These publishers and editors realise that the appropriate use of glosses increases the quality, usefulness and competitiveness of their products, so any qualified and up-to-date lexicographical support would most likely be more than welcome.

The current use of glosses is clearly comparable to the original way of glossing, where the gloss presents data that can help the user in understanding or using the word in an appropriate way. The gloss is used as an item with a lexicographical nature in an extra-lexicographical environment. Bearing in mind that glosses were originally also not used in lexicographic environments, but that the occurrence of glosses can be regarded as a major step in the beginning of lexicography, it is important that the current use of glosses should also be included within the scope of the term lexicography.

The proposal was made in Section 1 of this paper that the term dictionog-raphy should be introduced to refer to the sub-field of lexicography concerned with the planning, compilation and presentation of reference works like dictionaries, glossaries, thesauri, lexicons and encyclopaedias, and with the development of theories about them. Dictionography is the sub-field of lexicography concerned with the practice and theory of dictionaries, interpreted in the broad sense of the word.

Glosses did receive some attention in theoretical lexicography but with a focus only on their occurrence in dictionaries. This confirms the status of these glosses as lexicographically relevant, but it fails to include the more comprehensive use of glosses in the lexicographical discussion.

Section 3 of this article proposed the use of the term glossography to refer to the preparation and insertion of glosses into texts. Glosses resemble certain types of lexicographic items, and they are used to present specific types of data to readers to enhance their understanding of the meaning or use of a given word or expression. The extremely productive occurrences of glosses and their advanced and sophisticated use in the digital environment demand the recognition of glossography as a formal sub-field of lexicography. Glossography is not only the preparation and insertion of glosses into texts, but also the preceding preparation of empirical material to present an entirely new class of lexicographical data that can be used in, among other, writing assistants for both internal training and external presentation. Glossography is not only concerned with the practice of an expanded way of glossing, but also with the underlying theory. The lexicographical nature of glossing and glosses may never be underestimated. Consequently, glossography should also be regarded as a sub-field of lexicography.

The massive changes in lexicography during the digital era, the numerous innovative developments in the field of reference sources, the increased use of new kinds of lexicographical data in dictionary-external environments demand a new definition of lexicography. Such a definition has to be inclusive by negotiating the distinction between dictionography and glossography as two sub-fields of lexicography. It has to reflect the past, take cognizance of the present and make provision for future developments. Different types of dictionaries, other reference sources, glosses and other types of lexicographical data as well as the underlying theories need to be covered by this definition. The following is presented as a redefinition of lexicography:

Lexicography is the discipline that deals with dictionaries, other reference works, and glosses, all of which are designed to be consulted in order to retrieve information about words, things or facts.

It can be argued that as a discipline lexicography has a practical and a theoretical component, and that these two components have two main sub-fields, namely dictionography, with its focus on dictionaries and related products, and glossography, with its focus on glosses. From a historical and contemporary perspective, dictionography and glossography are concerned with handwritten, printed and digital products.

7. Conclusions

In this article we have argued that there is a need to redefine the term lexicography, taking into account both current and historical facts. The challenge lies in the largely overlooked glosses. The traditional focus on dictionaries and similar works has not been fair to these glosses, which have been orbiting dictionaries like small planets for more than two thousand years.

Originally, dictionaries evolved from glosses, which did not disappear but continued until the advent of printing, being inserted into existing texts by scribes and other learned people who wanted to explain difficult or obsolete words to readers. As we have seen, even during the long dominance of the printed book, authors and others kept glosses alive and gave them a myriad of new expressions.

The fact that the use of glosses in this new era was no longer a craft practised by a few scholars may, as has been suggested, be the reason why they were overlooked when seventeenth-century European lexicographers began to define their discipline as one concerned solely with dictionaries and related works. Be that as it may, the fact is that with the advent of digital technologies, and in particular artificial intelligence, glosses have been given a new lease of life that requires us to rethink history and include them in a redefinition of lexicography as a discipline.

In this article, therefore, we have redefined lexicography as a two-pronged discipline, concerned on the one hand with dictionaries and related works, and on the other with glosses, both traditional and new types that have emerged in the digital world. We have called these two sub-fields dictionography and glossography respectively.

We are convinced that all this is not an empty academic exercise, but a necessary foundation for a development that is already underway and is bound to accelerate in the near future. Michael Rundell's prediction that by the year 3000 lexicographers will not be doing the same thing as before is already becoming a reality.

As for dictionography, the authors of this article were recently involved in an experiment using chatbots and other digital techniques to write almost 3000 dictionary articles in a single day. This in itself not only increases productivity, but also radically changes the role of the lexicographer.

As for glossography, at least some of the glosses that can be used to advantage in digital texts, as we have seen in Figure 3, are largely the same type of data (definitions) that already exist in some lexicographical databases. This more than suggests that lexicographers should move away from primarily focusing on dictionaries when planning new projects, and instead focus on multi-purpose lexicographical databases that can both feed dictionaries and upload data to various digital software, such as writing and reading assistants. And even if it is not always the same type of data, lexicographers can plan from the outset to compile databases containing both types of data to cover multiple types of digital products. But we have also seen above how certain types of software, such as writing assistants, require entirely new types of glosses, which also require lexicographical expertise to be of high quality. These new types of glosses are problem-oriented and therefore cannot be stored in traditional lemma-based databases, but in a new class of problem-oriented databases. Today's lexicographers need to prepare themselves for these tasks.

The new technological breakthroughs will undoubtedly greatly increase the productivity of the traditional lexicographical compilation process. And while there will still be a need for highly skilled lexicographers to ensure quality, it is unlikely that there will be as many as there are today. However, with the redefinition of lexicography as a discipline that includes modern glosses, a development already observed in digital texts, a whole new field of work is opening up for well-trained lexicographers. This new field will consist not only of revision and routine, but also of creative tasks that require an open mind and a willingness to break new ground.

Rapid technological development does not mean the end of lexicography, as some have hastily suggested. It does mean, however, that the discipline cannot continue as before, but must adapt to new realities. Hopefully, a timely redefinition of the subject matter of lexicography, as proposed in this article, can contribute to this change in direction.

Bibliography

A. Dictionaries

Diccionario enciclopédico hispano-americano de literatura, ciencias y artes. 1887-1910. Barcelona: Montaner y Simón.

Hartmann, R.R.K. and G. James. 1998. Dictionary of Lexicography. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Pearsall, J. (Ed.). 1998. The New Oxford Dictionary of English. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Mish, F.C. (Ed.). 1987. Webster's Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary. Springfield, Massachusetts: Merriam-Webster. [ Links ]

Procter, P. (Ed.). 1978. Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English. Harlow: Longman. [ Links ]

Wiegand, H.E., M. Beifiwenger, R.H. Gouws, M. Kammerer, A. Storrer and W. Wolski (Eds.). 2010-2020. Wörterbuch zur Lexikographie und Wörterbuchforschung / Dictionary of Lexicography and Dictionary Research. Berlin: De Gruyter. [ Links ]

B. Digital tools

DeepL Write (beta version): https://www.deepl.com/write

Ginger: https://www.gingersoftware.com/

Grammarly: https://www.grammarly.com/

LanguageTool: https://languagetool.org

News in Slow Spanish. 2023. https://www.newsinslowspanish.com

ProWritingAid: https://prowritingaid.com/

C. Other literature

d'Alembert, J.L.R. 1754. Dictionnaire. Diderot, D. and J.L.R. d'Alembert (Eds.). 1754. Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers. Tome IV: 958-969. Paris: André le Breton, Michel-Antoine David, Laurent Durand and Antoine-Claude Briasson.

Bergenholtz, H. and R.H. Gouws. 2012. What is Lexicography? Lexikos 22: 31-42. [ Links ]

Bothma, T.J.D. and R.H. Gouws. 2022. Information Needs and Contextualization in the Consultation Process of Dictionaries that Are Linked to e-Texts. Lexikos 32(2): 53-81. [ Links ]

Bybelgenootskap van Suid-Afrika. 2014. Nuwe Testament en Psalms. 'n Direkte vertaling. Bellville: Bybelgenootskap van Suid-Afrika. [ Links ]

Du Plessis, H. 1982. Sintaksis vir eerstejaars. Pretoria: Academica. [ Links ]

Fuertes-Olivera, P.A. and S. Tarp. 2020. A Window to the Future: Proposal for a Lexicography-assisted Writing Assistant. Lexicographica 36: 257-286. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. and S. Tarp. 2017. Information Overload and Data Overload in Lexicography. International Journal of Lexicography 30(4): 389-415. [ Links ]

Grefenstette, G. 1998. The Future of Linguistics and Lexicographers: Will There Be Lexicographers in the Year 3000? Fontenelle, T., P. Hiligsmann, A. Michiels, A. Moulin and S. Theissen (Eds.). 1998. Proceedings of the Eighth EURALEX International Congress in Liège, Belgium: 25-41. Liège: English and Dutch Departments, University of Liège.

Hanks, P. 2013. Lexicography from Earliest Times to the Present. Allan, K. (Ed.). 2013. The Oxford Handbook of the History of Linguistics: 503-536. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Huang, F. and S. Tarp. 2021. Dictionaries Integrated into English Learning Apps: Critical Comments and Suggestions for Improvements. Lexikos 31(1): 68-92. [ Links ]

Huete-García, Á. and S. Tarp. 2024. Training an AI-based Writing Assistant for Spanish Learners: The Usefulness of Chatbots and the Indispensability of Human-assisted Intelligence. (to appear)

Hákanson, U., J. Masoliver, H.L. Beeck and J. Jensen. 1977. ESO ES 1. Spansk for begyndere. Tekstbog. First Edition. Copenhagen: Grafisk Forlag. (Second Edition: PRAXIS). [ Links ]

Kennedy, A. 2019. A Brief History of the Footnote - From the Middle Ages to Today. Quetext blog: https://www.quetext.com/blog/a-brief-history-of-the-footnote

Landau, S. 1984. Dictionaries: The Art and Craft of Lexicography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

McArthur, T. 1986. Worlds of Reference. Lexicography, Learning and Language from the Clay Tablet to the Computer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Niehaus, C. 2013. Top 500+ Wenresepte 2. Cape Town: Human & Rousseau. [ Links ]

Nomdedeu-Rull, A. and S. Tarp. 2024. Introducción a la lexicografía en espanol: funciones y aplicaciones. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Prins, J.F. 2003. Superconduction at Room Temperature without Cooper Pairs. Craighall: Mulberry MoonDesign. [ Links ]

Ruiz-Asencio, J.M., I. Ruiz-Albi and M. Herrero-Jiménez. 2020. Las Glosas Silenses. Estudio crítico y edición facsímil. Version castellana del Penitencial. Burgos: Instituto Castellano y Leonés de la Lengua. [ Links ]

Rundell, M. 2012. The Road to Automated Lexicography: An Editor's Viewpoint. Granger, S. and M. Paquot (Eds.). 2012. Electronic Lexicography: 15-30. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Rundell, M. 2018. Searching for Extended Units of Meaning - and What To Do When You Find Them. Lexicography 5: 5-21. [ Links ]

Stathi, E. 2006. Greek Lexicography, Classical. Brown, K. (Ed.). 2006. Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics. Vol. 5: 145-146. Second Edition. Oxford: Elsevier. [ Links ]

Tarp, S. 2018. Lexicography as an Independent Science. Fuertes-Olivera, P.A. (Ed.). 2018. The Routledge Handbook of Lexicography: 19-33. London/New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Tarp, S. 2020. Integrated Writing Assistants and their Possible Consequences for Foreign-Language Writing and Learning. Bocanegra-Valle, A. (Ed.). 2020. Applied Linguistics and Knowledge Transfer: Employability, Internationalization and Social Challenges: 53-76. Bern: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Tarp, S. 2022. A Lexicographical Perspective to Intentional and Incidental Learning: Approaching an Old Question from a New Angle. Lexikos 32(2): 203-222. [ Links ]

Tarp, S. and R.H. Gouws. 2019. Lexicographical Contextualization and Personalization: A New Perspective. Lexikos 29: 250-268. [ Links ]

Wiegand, H.E. 1998. Wörterbuchforschung. Berlin: De Gruyter. [ Links ]

Yong, H. and J. Peng. 2022. A Sociolinguistic History of British English Lexicography. London/New York: Routledge. [ Links ]