Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Lexikos

versão On-line ISSN 2224-0039

versão impressa ISSN 1684-4904

Lexikos vol.33 Stellenbosch 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.5788/33-1-1821

ARTICLES

Developing Dictionary Skills through Monolingual and Bilingual English Dictionaries at Tertiary-level Education in Hungary

Die ontwikkeling van woordeboekvaardighede m.b.v. eentalige en tweetalige Engelse woordeboeke in die onderwys op tersiêre vlak in Hongarye

Katalin P. MárkusI; Ida Dringó-HorváthII

IInstitute of English Studies, Department of English Linguistics, Károli Gáspár University of the Reformed Church in Hungary, Budapest, Hungary (p.markus.kata@kre.hu)

IIICT Research Centre / Educational Technology Training Centre, Károli Gáspár University of the Reformed Church in Hungary, Budapest, Hungary (dringo.horvath.ida@kre.hu)

ABSTRACT

Among reference works, dictionaries are particularly important in foreign language learning. Dictionaries provide language learners with a wide range of data, however, wading through the mass of data and information can be a daunting task. Mastering dictionary skills should be important in the language learning process; however, in official educational documents in Hungary, there are no clear guidelines on how to develop these skills. By integrating dictionary skills into the curriculum and teaching them explicitly in lessons, teachers could play an important role in bridging the gap between lexicographers and dictionary users. In the present study, we report on our methods of teaching lexicography and dictionary skills to students at a Hungarian university. The authors are speaking from experience, the discussion and accompanying material are based on more than 15 years of teaching practice. To ensure that the training can meet the expanding needs of young students, a longitudinal study was launched in 2020 to examine students' changing habits and needs. The aims of the article are threefold: first, to encourage the teaching of lexicography at university level by providing concrete methods, then to highlight the importance of dictionary skills, and finally, to emphasise the importance of integrating the effective teaching of the use of electronic dictionaries into dictionary didactics. In this context, the article underlines the need to incorporate new evaluation criteria as well as to develop new skills for digital dictionaries, different from those for print dictionaries, into education.

Keywords: teaching lexicography, dictionary didactics, reference skills, dictionary skills, dictionary use, university course design, course evaluation, online dictionaries, evaluation of dictionaries

OPSOMMING

Onder naslaanwerke is woordeboeke besonder belangrik in die aanleer van 'n vreemde taal. Alhoewel woordeboeke taalaanleerders van 'n wye reeks data voorsien, kan dit 'n enorme taak wees om deur die massa data en inligting te worstel. Ofskoon dit belangrik behoort te wees om woordeboekvaardighede in die taalaanleerproses te bemeester, bestaan daar geen duidelike riglyne in amptelike onderwysdokumente in Hongarye oor hoe om hierdie vaardighede te ontwikkel nie. Deur woordeboekvaardighede in die kurrikulum te integreer en dit eksplisiet in lesse te onderrig, kan onderwysers 'n belangrike rol speel om die gaping tussen leksikograwe en woordeboekgebruikers te oorbrug. In hierdie studie word verslag gelewer oor die metodes wat ons gebruik om leksikografie en woordeboekvaardighede aan studente by 'n Hongaarse universiteit te onderrig. Die outeurs beskik oor baie ervaring en die bespreking en bygaande materiaal is op meer as 15 jaar se onderrigpraktyk gebaseer. Om te verseker dat die opleiding in die toenemende behoeftes van jong studente kan voorsien, is 'n longitudinale studie in 2020 van stapel gestuur om die veranderende gewoontes en behoeftes van studente te bestudeer. Die doel met hierdie artikel is drieërlei van aard: eerstens, om die onderrig van leksikografie op universiteitsvlak aan te moedig deur konkrete metodes te verskaf, daarna, om die belangrikheid van woordeboekvaardighede uit te lig, en laastens, om die belangrikheid van die integrasie van effektiewe onderrig van die gebruik van elektroniese woordeboeke in die woordeboekdidaktiek te beklemtoon. Teen hierdie agtergrond word die behoefte aan die inkorporering van nuwe evaluasiekriteria sowel as die ontwikkeling van nuwe vaardighede vir digitale woordeboeke, verskillend van dié vir gedrukte woordeboeke, in die onderwys beklemtoon.

Sleutelwoorde: leksikografieonderrig, woordeboekdidaktiek, naslaanvaardighede, woordeboekvaardighede, woordeboekgebruik, ontwerp van universiteitskursusse, kursusevaluering, aanlyn woordeboeke, evaluering van woordeboeke

Introduction

In today's fast-changing online world, we need to have a wide range of knowledge - but not necessarily in our heads. Students need an education that builds a solid foundation for life-long learning to compete with advanced professional skills in our rapidly changing society, in which new knowledge must constantly be acquired and integrated (European Commission 2019; RFCDC 2018). The dictionary is one of the first reference sources students should learn to use and in turn, these skills will help to prepare them for university-level work since it is one of the most appreciated and widely used resources for learning a language (cf. Lew 2016; Nied Curcio 2022). In the hands of a skilled learner, a dictionary is an invaluable resource and once we learn how to use it successfully, it opens the way to autonomous learning, which puts the power in the students' hands. What is more, these skills play a crucial role in supporting lifelong learning (Campoy-Cubillo 2015).

When talking about dictionaries, first it is important to clarify that there are many types of dictionaries available today, each of which aims to meet a different need (see Engelberg and Lemnitzer 2009; Wiegand et al. 2010). As far as the form of publication is concerned, one can distinguish between print and electronic dictionaries. Typologies of electronic dictionaries can be developed on the basis of different features (cf. Wiegand et al. 2010), but it is fundamental to distinguish between electronic dictionaries for the use of people or of machines/ software (e.g., translation software) - the latter is not the subject of this article. Read (2023) notes the other specific types of data dictionaries may contain (e.g., pronunciation, grammatical forms, etymologies, syntactic peculiarities, variant spellings) and the various roles they can play in different contexts, emphasising the diversity of dictionaries from the viewpoint of their objectives and content. Read (2023) also highlights the role of the dictionary in the learning process, stating that "dictionaries can encourage schoolchildren to learn about language". Dictionaries, especially monolingual and bilingual learner's dictionaries, are still considered to be very useful language learning tools in today's digital world where we are surrounded by technology such as AI (Artificial Intelligence), and MTs (Machine Translators) (cf. Campoy-Cubillo 2015; Lew and De Schryver 2014; Nied Curcio 2022). At the same time, the role of dictionaries is constantly changing, with more and more digital tools entering the educational process. In the future, we will have to learn to collaborate and train students on how and when to use the wide range of resources effectively (cf. De Schryver and Joffe 2023; Jakubíček and Rundell 2023; Lew 2023; Lew and De Schryver 2014). Students who have mastered the use of reference works will find it simpler to use a variety of reference materials as they progress from primary school to secondary school and then to university.

In the language learning process, it should be the task of language teachers to draw students' attention to the effective use of monolingual and bilingual learner's dictionaries and other reference works, which assist language learners in reading, writing, and translation activities (cf. Campoy-Cubillo 2002, 2015; Nied Curcio 2022). For this reason, teachers should be prepared for this task within the framework of teacher training. The use of reference works should also be emphasised as part of the language learning process in universities to foster lifelong learning and learner autonomy, substituting for the human teacher in addressing language problems. All these background events clearly outline some important steps to be taken in order to provide training for teachers to fill this gap (cf. Atkins and Varantola 1998; Cowie 1999, Chi 2003; Dringó-Horváth 2017; Lew 2011; Lew and Galas 2008; P. Márkus 2020a; P. Márkus and Pődör 2021; P. Márkus et al. 2023; Sinclair 1984; Yamada 2010).

With this article, we would like to contribute to the enrichment of studies on the teaching of lexicography (and dictionary skills) as an academic subject. The more widely we share our academic experiences, the more insight we can provide into different practical teaching methodologies and their effectiveness (for more on the subject, see for example Bae 2011; Béjoint 1989; Chi 1998; Hartmann 2001; Magay 2000; Martynova et al. 2015; Nkomo 2014; Prćić 2020; P. Márkus 2020b). The main idea of this article was inspired by Prćić (2020), who describes a university course in lexicography that was specifically designed and developed for advanced EFL (English as a Foreign Language) students. Prćić advocates for the teaching of both theoretical and practical lexicography to university students by offering specific recommendations. In the present study, a similar approach is attempted, with the difference that the course is complemented by the development of dictionary skills and its methodology. In light of the above-mentioned, the aims of the article are threefold: first, to encourage the teaching of lexicography at university level by providing concrete methods, then to highlight the importance of dictionary skills, and finally, to emphasise the importance of integrating the effective teaching of the use of electronic dictionaries into dictionary didactics. In the following section, the related research will be outlined, which has been conducted to support the teaching of "Lexicology and Lexicography" as an academic subject at Károli Gáspár University of the Reformed Church in Hungary.

1. Researching didactic lexicography and dictionary use

Many research projects at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at Károli Gáspár University of the Reformed Church in Hungary are focused on dictionary didactics, dictionary use and how dictionaries could best be employed in the context of language teaching and learning. As members of these projects, the authors have been investigating EFL and GFL (German as a Foreign Language) students' dictionary use habits and strategies in the Hungarian context since the early 2000s. The research projects were launched to help develop teaching materials for lexicography courses. Based on the results, we can offer courses tailored to the needs of students.

Márkus and Szöllősy (2006) used a questionnaire in conjunction with a set of tasks to test whether secondary school EFL students could use their dictionaries effectively. Participants (n=122) were asked about their dictionary use habits and a set of practical exercises was used to identify the factors that make it difficult to use a dictionary. The tasks focused on the following main topics: interpreting abbreviations and symbols used in dictionaries; using grammatical information; finding meanings, collocations, idioms, and phrasal verbs. The findings revealed that students' language awareness and dictionary use awareness were very low. As a result, it was suggested that dictionary training be included in school and academic curricula (Márkus and Szöllősy 2006). The survey provided valuable insights that could be implemented in teaching aids, such as workbooks, and study pages in coursebooks to develop dictionary skills (P. Márkus 2020b; P. Márkus 2023; P. Márkus et al. 2023).

In her survey of undergraduates (n=80), Dringó-Horváth (2017) indicated that online dictionaries were becoming more and more popular. Approximately half of the respondents claimed that they used online dictionaries to look up the meaning of a word or expression, whereas just a quarter reported that they used print dictionaries for this reason. When looking for pronunciation information, the dominating influence of online dictionaries appeared to be obvious, with almost 60% of respondents reporting that they used online dictionaries. Due to the difficulty of interpreting phonetic symbols, print dictionaries have already played a very minor role in this activity. The final section of the survey was particularly important since it addressed the learning of dictionary skills. The vast majority of respondents stated that they acquired those skills in a self-taught way (Dringó-Horváth 2017). The results appear to confirm the research of Márkus and Szöllősy (2006), who found that only a small percentage of respondents received training in dictionary use at school and university.

In her study, P. Márkus (2020a) discussed the state of dictionary culture and dictionary didactics in Hungary by analysing educational documents (Common European Framework of Reference for Languages, National Core Curriculum, Framework Curriculum, syllabuses). The analyses showed that in Hungary 'dictionary awareness' was generally rather low and that more attention to the teaching of dictionary skills was needed in the curricula for foreign language learning. The study also demonstrated the use of a dictionary workbook to remedy the situation. Designed to accompany an English-Hungarian/Hungarian-English Learner's Dictionary, the workbook contained exercises and activities which aimed to help language learners in two ways: first, by teaching the basic dictionary skills that students need to locate headwords or expressions and their meanings in the dictionary; and second, by showing how the dictionary can be used as a tool and a source of information about the English and Hungarian languages. The workbook was piloted by teachers and students at primary and secondary schools, and it was designed to be used both in the classroom and for self-study. In 2020, P. Márkus et al. (2023) launched a longitudinal research project on the dictionary use habits of EFL and GFL students, as well as their attitudes towards learning and teaching dictionary skills in the L2 classroom. The aim of the project is to assess students' dictionary use habits and needs at three-year intervals in order to tailor dictionary training to those needs.

The results of international surveys and monitoring of dictionary use seem to show a dismal picture of language learners' reference skills (see for example Atkins and Varantola 1998; Bogaards 1998; Chan 2012; Dringó-Horváth 2017; Márkus and Szöllősy 2006; Müller-Spitzer et al. 2018; Nesi and Haill 2002; Nesi and Meara 1994; Nied Curcio 2022). Among other things, it is a common problem that language learners are not aware of where to start looking up the information they require; where to find answers to their questions about words, fixed expressions, synonyms and grammar - or if they do find the answer, they often cannot interpret the data found (cf. Frankenberg-Garcia 2011; Müller-Spitzer et al. 2018). Usual issues with interpretation are mostly caused by the lexicographical codes, symbols and abbreviations used in dictionary practice. Moreover, a lot of previous research reports that very little training in dictionary use takes place in schools (cf. Dringó-Horváth 2017; Márkus and Szöllősy 2006; Nied Curcio 2022; P. Márkus et al. 2023).

The development of dictionary skills should start in primary school and be progressively developed in secondary school as the language level rises, in order to ensure quality knowledge and skill development. Even university students, especially teacher trainees, need to learn to use (online) dictionaries properly (cf. Campoy-Cubillo 2015; Nied Curcio 2022) because if students learn how to use dictionaries effectively, they will be able to teach it more successfully. It is encouraging to see that more and more universities are recognising the importance of teaching lexicography and dictionary use (cf. Bae 2011; Hartmann 2013; Magay 2000; Nied Curcio 2022; P. Márkus 2020a; P. Márkus and Pődör 2021; Prćić 2020).

With the given objectives in mind, focus now shifts to the "Lexicology and Lexicography" course.

2. Lexicography and dictionary use as a university course at Károli Gáspár University of the Reformed Church in Hungary

2.1 About the course in general

In the area of pedagogical lexicography, there is widespread agreement that dictionaries should be more and more user-oriented and at the same time, users should be trained to use dictionaries successfully (see for example Bae 2011; Lew 2016; Nied Curcio 2022; P. Márkus et al. 2023). The aims and findings outlined in section 1 suggest that it would be useful to complement theoretical lexicographic teaching in the university context with dictionary didactics, and the teaching of dictionary use. In the following section, a course in "Lexicology and Lexicography", which has been taught since the academic year 1996/1997 (at the Department of English Linguistics), will be outlined. The lexicology section of the course serves as a foundation for the various lexicographic topics that follow. The goal is to introduce the theoretical and practical connections between these two key areas and to provide all the necessary elements needed for practical training in the use of dictionaries.

Károli Gáspár University was founded in 1993 and it was the first among Hungarian universities to introduce the teaching of lexicography (for more information on the original course design, see Magay 2000). In 1996, Tamás Magay devised the course, which since his retirement has been taught by Dóra Pődör and Katalin P. Márkus, the developers of the course and authors of the course's teaching materials. "Lexicology and Lexicography" is a compulsory elective course. It lasts 12 weeks and has two classes per week for between 20 and 30 English and German as a Foreign Language teacher trainees. During the semester, students learn all the basic concepts of lexicology and lexicography, gain insight into research on dictionary use, dictionary analysis, and learn about print and electronic dictionaries relevant to language learning. After exploring the different types of dictionaries, the emphasis is placed on general synchronic descriptive (English monolingual and bilingual) dictionaries, and therefore no in-depth study of etymological or specialised dictionaries is undertaken. When the students leave university, they will need to know for what purpose, for what age group, and what type of dictionary to use, so they should have sufficient knowledge of reliable monolingual and bilingual English dictionaries. In addition, they will need to be familiar with methods of teaching dictionary use. In selecting the course material, we have to take into account that on the theoretical and practical level of lexicography, we have four main actors: the dictionary-maker compiles the dictionary, which is purchased by the user, who is often supported by the teacher who teaches dictionary skills, and finally, we have to mention the researcher, whose work supports the development and ensures continuous quality (cf. Hartmann 2001).

Every one of the four roles must be covered during the training. In the theoretical part, the dictionary editing process is outlined. After learning about the micro-, macro- and megastructure of dictionaries, the topic of dictionary use is introduced, and it is worthwhile to accompany it with vocabulary and grammar exercises so that different language problems can be illustrated by answering them with a dictionary. This brings us to the area of dictionary didactics, where we may discuss methods of teaching dictionary use, illustrated by practical exercises. Finally, when students have a broader picture of the various fields of lexicography, they learn about possible methods and tools of dictionary research (cf., e.g., Fóris 2018; Lew 2016; Nied Curcio 2022; P. Márkus 2020b; P. Márkus and Pődör 2021).

2.2 The syllabus

In accordance with the aforementioned objectives, the syllabus of this course has been designed to present a balanced picture of lexicology and lexicography to students at an advanced level of English proficiency (focusing in particular on English monolingual and English-Hungarian/Hungarian-English bilingual learners' dictionaries). It has been developed to give teacher trainees an understanding of the field of lexicographic research as well as a variety of methodological tools and didactic materials for teaching dictionary use. The syllabus (Table 1) is divided into three thematic sections (Lexicology; Lexicography; Dictionary use and dictionary skills), each of which is further subdivided into several thematic units. Here are the complete thematic sections and their associated units:

2.3 Course requirements and grading policy

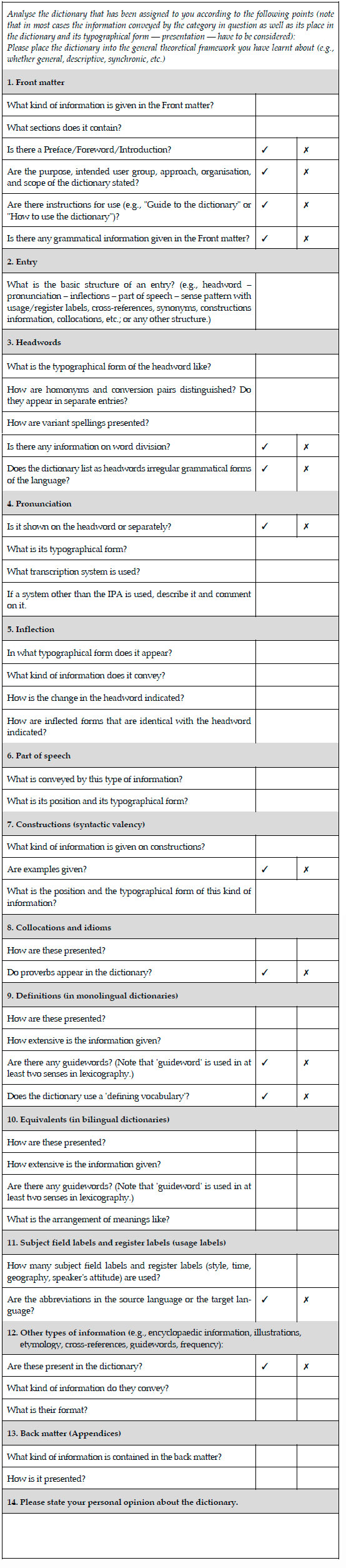

To successfully complete the course, students are required to complete two written assignments for grading. First, they are asked to choose a dictionary from a given list (the list includes dictionaries published by renowned international and Hungarian publishers - English monolingual and English-Hungarian/Hungarian-English bilingual dictionaries) and analyse it according to a set of guidelines prepared by Dóra Pődör (for an abridged version see Appendix 1). An important aspect of the guide was to cover every detail of the dictionary so that students could become acquainted with it thoroughly. This home assignment represents 50% of the final grade. Second, students must complete a project in which they create a workbook (worksheets) for the development of dictionary skills. This assignment represents 50% of the final grade. To receive a grade, students must score at least 51% on each of these assignments.

The primary aim of the dictionary analysis is to assist students in thoroughly exploring their chosen dictionary using the criteria provided (see Appendix 1). It is essential because even during their university years, most students use dictionaries only superficially and are unaware of the wealth of data they contain (see for example Müller-Spitzer et al. 2018; Nied Curcio 2022; P. Márkus et al. 2023). To assist students in better comprehending the structure of the dictionary and the richness of information it contains, a substantial number of questions are included in the guide. If they feel the necessity, students may employ the criteria at any point during their classroom practice. Teacher trainees need to be prepared to teach dictionary use, so the analysis is followed by the compilation of a dictionary workbook, which is usually attached to their teaching portfolio (which is required to be completed and submitted to graduate).

Before delving into more depth, it is crucial to understand and distinguish between two fundamental forms of dictionary use: active and passive. Teachers need to develop exercises to demonstrate and practise both types of dictionary use if we want to develop a conscious use of dictionaries in learners. In the seminars, methods and exercises for the different dictionary elements are demonstrated, and students are given the opportunity to prepare their own exercises based on the examples presented. The exercises cover each part of the entry, practising the identification of each type of data. The activities aim to demonstrate effective dictionary use and to develop dictionary competence.

From a methodological point of view, there are several key aspects to keep in mind regarding the tasks. Here are only a few examples because it is not possible to provide a complete picture within the scope of this study: recognition; observation; comparison; creativity; and cooperation. When designing the exercises, it is critical to emphasise the process of recognition by using exercises that focus on selecting the correct information (e.g., finding the correct meaning) or on the interpretation of the data in the dictionary (e.g., interpreting signs and abbreviations). Tasks describing the structure of the entry and interpreting the dictionary's instructions for use reinforce the process of observation. Reading the external texts of dictionaries can be a significant aid to effective use, especially if the dictionary type is new to the user or if the use of the dictionary is required for more complex tasks. Both are typical of the activities of foreign language students in higher education. That's why the importance of reading the introduction to the dictionary should be stressed and the correct interpretation of abbreviations and phonetic symbols should be practised. The process of comparison is developed, for example, when students compare a dictionary entry from an electronic dictionary with a print dictionary (or a dictionary entry from a previous edition with the revised edition) as a comparison and analysis task. Tasks that require creativity and cooperation (when learners create similar tasks independently) will have huge motivational power in the language learning process (cf. Gonda 2009; P. Márkus and Pődör 2021).

2.4 General feedback and future aims

In line with the Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in the European Higher Education Area (ESG 2015), our university has its own quality assurance system (Student Evaluation of Teacher Performance). Students rate the success of the course on a scale of 1 to 5 (where 5 means extremely or very satisfied; 1 means extremely or very dissatisfied). Completion of the questionnaire is not mandatory; the results provide feedback to the university on how well the course is meeting the requirements of the ESG. Based on the results of the previous four years, the average rating of the course was 4.8 out of 5.

When asked, students exhibit a willingness to learn more about lexicographic tools. They want to know which dictionaries are accessible to language learners, which are the most reliable, how they are built and structured, and how to recognise information that is reliable. Most students reported that the course was very useful, they enjoyed it, and that they were now more familiar with learner's dictionaries and lexicographic tools. The feedback from students suggests that they start to look at dictionaries with "different eyes".

Regarding course modifications in the future, we should place a greater emphasis on digital dictionaries as well as related resources (electronic translators, or the combination of translators, AI, and dictionaries) in the course material. Digital competence is one of the eight key competences for lifelong learning developed by the European Union - a core competence that facilitates the acquisition and development of other competences (such as languages) and is in fact considered one of the core competences for the 21st century (European Commission 2019). As the foundations of our modern culture are increasingly based on and powered by the digital world, info communication and digital tools are increasingly present in a wide range of contexts (such as language learning, language exams, dictionary use or dictionary writing), and digital tools are therefore an essential part of schools. Developing digital competence is essential, as knowing how to use a computer does not necessarily mean that students can quickly access and process the information they are looking for. Knowing the layout and basic properties of data structure is essential to accessing the right information. Students need to know the internal structure (whether it is a dictionary entry or a corpus) of the textual content that they read in print or on the internet, otherwise the retrieval of information will take a lot of time or fail completely (cf. Tarp and Gouws 2020; M. Pintér 2019). The next section will outline the directions set by future challenges and share the materials that are in the preparatory phase.

3. New challenges: Specific skills for the teaching of electronic dictionary use

Research shows that electronic and especially web-based online dictionaries are becoming increasingly popular among language learners (Dringó-Horváth 2012; Nied Curcio 2015; Töpel 2015). The significant decline in user interest in print dictionaries as well as the high costs compared to electronic dictionaries has led to a continuous decrease in the production of print dictionaries while the online offer continues to expand (cf. Töpel 2015). Several studies of user research show a lack of knowledge of electronic dictionaries (cf. Nied Curcio 2015; P. Márkus et al. 2023), which indicates a great deal of uncertainty when selecting from the growing offer.

Since electronic dictionaries differ in many respects from print dictionaries, new examination criteria and new skills of use are needed to be established (for textual differences and terminological difficulties, see Müller-Spitzer 2014; details of new evaluation criteria and the differences in usage and successful skills can be found in Kemmer 2010; Dringó-Horváth 2012, 2021; Müller-Spitzer, Koplenig and Wolfer 2018; Müller-Spitzer et al. 2018). The relevant quality features presented below offer a practical orientation aid in the modern dictionary landscape (also presented in a checklist form in Appendix 3). Furthermore, concrete task suggestions show how specific features of digital dictionaries can be included in dictionary didactics.

3.1 Changing quality characteristics as drivers of new dictionary skills

In addition to the established, primarily content-based criteria that are transferable to electronic dictionaries, other, new quality characteristics should also be used that are only valid in the electronic learning environment. The reason for this lies essentially in the changed structure and functioning of this new form of publication: "Appropriately designed electronic dictionaries differ from print dictionaries not only in terms of media but above all in the variety of linguistic information offered or in the revolutionary way in which the linguistic data are presented. In this respect, unfortunately, one finds serious differences in quality in the landscape of electronic dictionaries" (Dringó-Horváth 2012: 35). Accordingly, it is extremely important to know appropriate features, including newly established ones, for selection and effective use in foreign language teaching.

3.1.1 Traditional quality characteristics

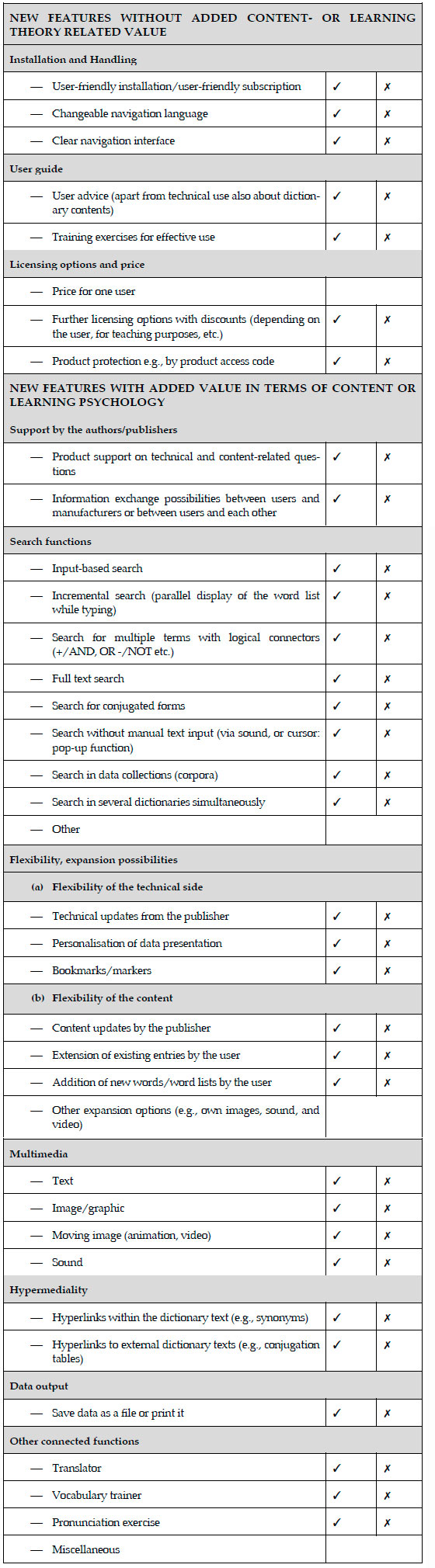

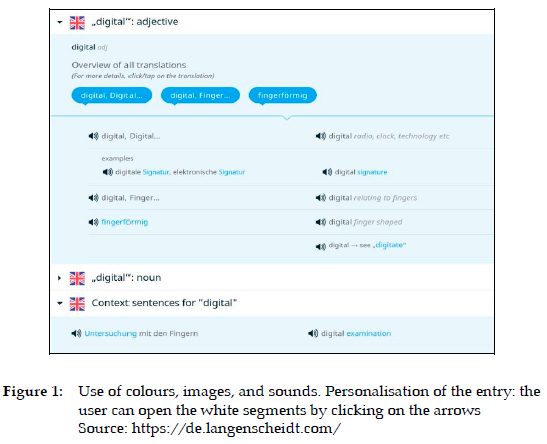

Many criteria, especially those related to content, can be applied - possibly in a slightly modified manner - to electronic dictionaries as well. The basic criterion is still the examination of the data set: the number of entries or the number of equivalents and the quality of information in the entries. The former can hardly be checked in the case of electronic dictionaries, so in this respect the user is entirely dependent on the data provided by the authors/publishers. In the presentation of entries, it is necessary to check to what extent the structural indicators make the information clear and unambiguous, or whether they are designed in a way that is suitable for the digital context (possibility of personalisation, use of colours, highlighting or other media such as images or sounds, cf. Figure 1).

It is important to note, however, that research on dictionary use has shown that not all users value the above-listed features (cf. Müller-Spitzer and Koplenig 2014; Kosem et al. 2018).

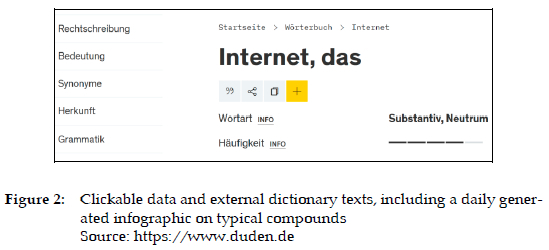

Elements that make the text more compact should be used less since in the digital environment one does not necessarily require these summaries thanks to the increased storage capacity and the flexible presentation possibilities of data. This increased capacity allows for the presence of as many external dictionary texts as possible that promote foreign language acquisition, such as notes on abbreviations, dictionary grammar or tables on the morphology and syntax of lexemes, which in turn makes it an important quality criterion. A new feature is that data and external dictionary texts can be adapted to the element being searched for (e.g., conjugation tables for each unit), and are generated automatically on a daily basis (Figure 2).

In addition, the quality of the content must be checked: To what extent can the editorial team be described as reputable, or is it indicated if the dictionary is based on the print version? A distinction must be made between products that can be described as electronic versions of print dictionaries and those that have been designed directly for the electronic environment (cf. Wiegand et al. 2010).

3.1.2 New quality characteristics

Among the new aspects, there are quality features that can make working with the dictionary much more convenient and faster for the user compared to print dictionaries but do not provide any advantage in terms of content. Such features are, for example, options that make using the product easier or even possible in the first place: installation and handling of the clear user interface as well as author/publisher support. This group also includes aspects that enable an adequate purchase/use decision, such as the corresponding user note (information on the most important characteristics of the dictionary with pictures and training exercises to practise adequate use) and the licence information with special consideration for the possible school use of the product.

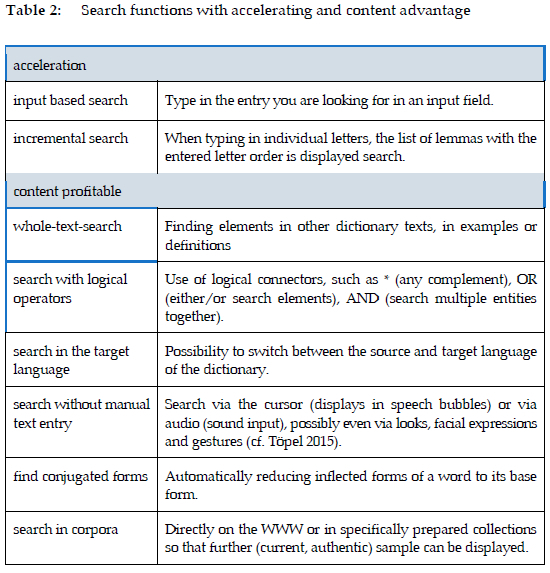

Other new features bring advantages in terms of content compared to print dictionaries. These include the different search functions, the type and number of which offer a decisive criterion in the evaluation. Here, we can also distinguish search functions that only contribute to facilitating and accelerating the retrieval of searched information for dictionary users from functions that also provide an advantage in terms of content (Table 2):

A self-report questionnaire survey found that participants do not seem to take advantage of the various search techniques (P. Márkus et al. 2023), but research based on screen recording in conjunction with a thinking-aloud task showed, that users adapt their search strings to the particular tool they use, so in this respect they "are quite aware of the different functionalities of search engines, translation tools and dictionaries" (Müller-Spitzer et al. 2018: 310).

Other quality features that can be beneficial in terms of content or learning psychology are above all the following:

- Multimedia: The possibility of integrating different types of media (such as images, graphics, animation, and video).

- Flexibility of the technical side: Possibility of updating the management software or the online interface, changing and possibly saving the data presentation options according to user wishes (setting of colours or displayed elements), or the possibility of creating bookmarks, markings to directly reach the elements that are important for the user.

- Flexibility of content: Possibility to expand the data by the publisher as well as by the user. This creates personalised dictionaries for individual as well as community use (in the case of publicly editable built-up dictionaries, with or without editorial review).

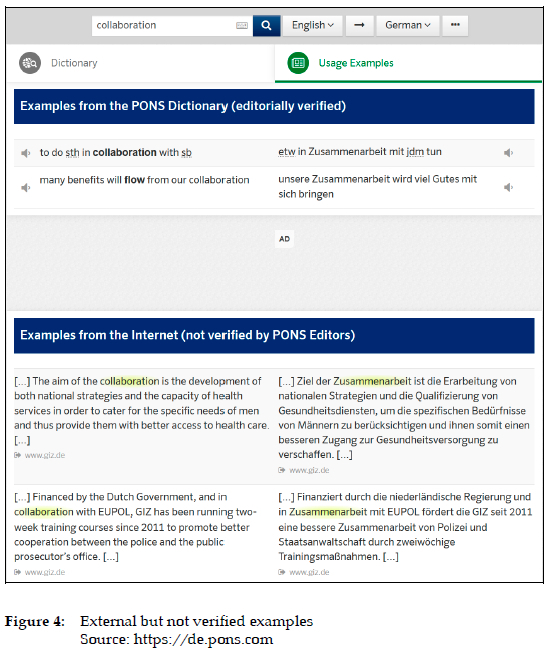

- Hypermediality: the meaningful linking of individual dictionary entries to each other as well as to external dictionary texts (abbreviations, grammar tables, etc.) and to other dictionaries or corpora in order to increase the number of hits and the number of (authentic, up to date) examples (see Figure 4).

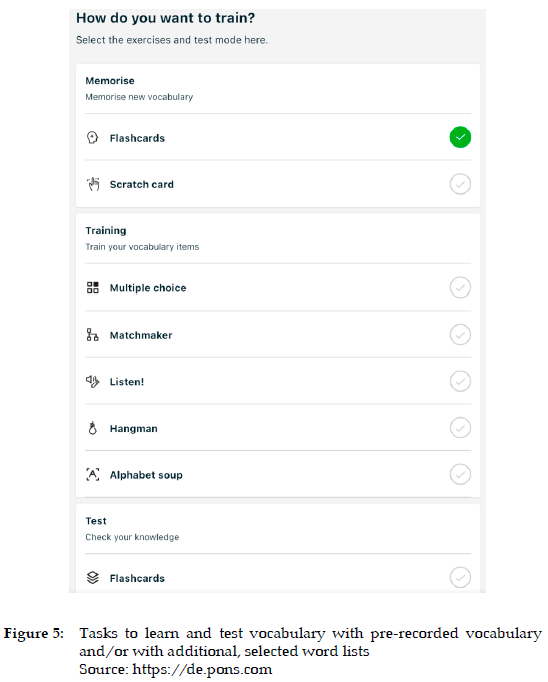

- Functionality: In addition to the dictionary function, electronic dictionaries often deliver other functions that are usually helpful for foreign language learners, such as translator function, vocabulary trainer or pronunciation practice function (see Figure 5).

- Author/publisher support: In the case of digital, updatable products, the need for continuous mutual contact and information exchange increases from both sides to make technical and content updates as well as further user-induced development of the dictionary possible.

Quality features that provide an advantage in terms of content or learning psychology compared to print dictionaries should be valued more highly. It could be used for quick orientation of foreign language teachers and learners as well as for teaching purposes.

3.2 Adapted dictionary didactics when teaching the use of electronic dictionaries

The new, enhanced quality features of dictionaries in the digital learning environment also have an impact on dictionary didactics, i.e., on the development of concepts and working methods for teaching effective dictionary use. Following a basic description by Zöfgen (2010), the main functions and tasks of dictionary didactics can be formulated as follows: Learners should

- know the different types of dictionaries and the data they contain;

- acquire knowledge about the structure, arrangement principles and text-typical features of dictionaries;

- be enabled to master the basic skills of searching and retrieving lexicographic data and the technique of looking up information;

- be encouraged to use dictionaries responsibly, which includes both the ability to make selections and to contribute to the development of dictionaries that are appropriate for the target group and are user-friendly.

In the following section, ideas as well as concrete task suggestions are given on how specific features of digital dictionaries can be included in this respect.

- Knowledge about dictionary types

When acquiring bibliographic knowledge, the problem arises that, on the one hand, some previously familiar terms lose their original meaning (pocket dictionary, unabridged dictionary) and, on the other hand, new phenomena have to be named, whereby the lack of a uniform terminology makes orientation difficult. From the perspective of foreign language teaching, the reliability of the data stock (see above) and completeness (dictionaries that can no longer be expanded, or advanced dictionaries that can be expanded by the editors and/or users, cf. Wiegand et al. 2010) are also important.

Some traditional type designations common for print dictionaries can be used well (monolingual, bilingual or multilingual dictionary, thematic dictionary, learner's dictionary, specialised dictionary, etc.), but a clear-cut distinction is becoming increasingly difficult as a result of the growing complexity of these products: dictionary portals or complex software with multiple, coupled functions can search several dictionaries simultaneously.

- Knowledge about structure

With the respective publication form of a dictionary - even if it is the same dictionary in printed or electronic form - the structure, the structural elements and the characteristic features inevitably change (cf. Dringó-Horváth 2012; Müller-Spitzer et al. 2018). Consequently, learners must be made aware that certain data in electronic dictionaries can also be found in new, unusual or even impossible forms in print dictionaries and they must discover how they work.

- Basic skills in searching

When thinking about making successful searches in the digital environment, one must also include the appropriate handling of the user interface. The recognition and adequate use of different search functions are also important; therefore, in the lessons, the focus should be on tasks for getting to know and practising individual search options. However, if elements can be retrieved quickly and effortlessly again and again, one (subconsciously) makes less effort to memorise them (cf. Rüschoff and Wolff 1999). Thus, lesson instruction should also include awareness raising activities that emphasise the conscious applying of found information to practice.

- Responsible use

Since electronic dictionaries are likely to contain a wide range of data sets, the ability to make selections is particularly important, especially in the case of collaboratively editable built-up dictionaries. At the same time, these make it possible for users to really contribute actively and effectively to the production of dictionaries that are user-friendly and appropriate for the target audience. The shared responsibility for this work should also be emphasised in the classroom. As a further contribution possibility, users can regularly inform publishers about deficiencies in dictionaries.

4. Conclusion

In this article, we aimed to describe in detail a university course in Lexicology and Lexicography. In addition to the theoretical and practical aspects, the description includes additional information on related research projects which have been conducted to support the design of the course. By providing the syllabus and a set of course requirements, we may be able to provide inspiration for other universities planning similar courses. The materials attached in the appendix may also provide ideas for resources for lexicographic and dictionary skills training. The article also looks at future challenges and possible course modifications, since we need to understand how the role of dictionaries is changing and be able to adapt to a constantly changing world. The incredible pace of technological progress is taking lexicography and dictionary didactics into new areas, changing dictionaries and thus dictionary use. At the same time, in our modern world, the role of dictionaries and lexicons as information carriers is becoming increasingly important. The information literacy skills developed through the use of dictionaries can be useful in many areas of the information society - for example, independent learning, digital literacy, problem-solving and information retrieval (DCF 2020; ECA 2021; European Commission 2019). Acquiring all these will be difficult if reference works, dictionaries and encyclopaedias are left out of the educational process (cf. DCF 2020). The teaching of dictionary use should be given a more prominent role in future public education to meet the challenges of the 21st century, hence teacher training at university level should prepare teacher trainees for this. Working and learning with digital dictionaries is - despite many similarities - marked by significant differences compared to working with print dictionaries. Hopefully, this article can help foreign language teachers and learners to become aware of these differences and to include them more and more in their dictionary use.

Acknowledgements

For constructive comments, the authors wish to thank the anonymous reviewers. Additionally, they extend their appreciation and thanks to Mr André du Plessis for his valuable suggestions and support.

References

Atkins, B.T.S. and K. Varantola. 1998. Language Learners Using Dictionaries: The Final Report on the EURALEX/AILA Research Project on Dictionary Use. Atkins, B.T.S. (Ed.). 1998. Using Dictionaries. Studies of Dictionary Use by Language Learners and Translators: 21-81. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110929997.21 [ Links ]

Bae, S. 2011. Teacher-Training in Dictionary Use: Voices from Korean Teachers of English. Akasu, K. and S. Uchida (Eds.). 2011. ASIALEX2011 Proceedings, LEXICOGRAPHY: Theoretical and Practical Perspectives: 45-55. Kyoto: Asian Association for Lexicography. [ Links ]

Béjoint, H. 1989. The Teaching of Dictionary Use: Present State and Future Tasks. Hausmann, F.J., O. Reichmann, H.E. Wiegand and L. Zgusta (Eds.). 1989. Wörterbücher/Dictionaries/Dictionnaires: Ein internationales Handbuch zur Lexikographie/Dictionaries. An International Encyclopedia of Lexicography/Dictionnaires. Encyclopédie internationale de lexicographie. Vol. 1: 208-215. Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Bogaards, P. 1998. Scanning Long Entries in Learner's Dictionaries. Fontenelle, T., P. Hiligsmann, A. Michiels, A. Moulin and S. Theissen (Eds.). 1998. EURALEX '98 Actes/Proceedings: 555-563. Liège: English and Dutch Departments, University of Liège. [ Links ]

Campoy-Cubillo, M.C. 2002. Dictionary Use and Dictionary Needs of ESP Students: An Experimental Approach. International Journal of Lexicography 15(3): 206-228. [ Links ]

Campoy-Cubillo, M.C. 2015. Assessing Dictionary Skills. Lexicography ASIALEX 2: 119-141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40607-015-0019-2 [ Links ]

Chan, A. 2012. Cantonese ESL Learners' Use of Grammatical Information in a Monolingual Dictionary for Determining the Correct Use of a Target Word. International Journal of Lexicography 25(1): 68-94. [ Links ]

Chi, M.L.A. 1998. Teaching Dictionary Skills in the Classroom. Fontenelle, T., P. Hiligsmann, A. Michiels, A. Moulin and S. Theissen (Eds.). 1998. EURALEX '98 Actes/Proceedings: 565-577. Liège: English and Dutch Departments, University of Liège. [ Links ]

Chi, M.L.A. 2003. An Empirical Study of the Efficacy of Integrating the Teaching of Dictionary Use into a Tertiary English Curriculum in Hong Kong. Vol. IV: Research Reports (Ed. G. James). Hong Kong: Language Centre, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. [ Links ]

Cowie, A.P. 1999. English Dictionaries for Foreign Learners: A History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

DCF = Office of the Secretary-General of the European Schools. 2020. Digital Competence Framework for the European Schools. https://www.eursc.eu/BasicTexts/2020-09-D-51-en-2.pdf

De Schryver, G.-M. and D. Joffe. 2023. The End of Lexicography, Welcome to the Machine: On How ChatGPT Can Already Take over All of the Dictionary Maker's Tasks. Conference paper. 20th CODH Seminar, Center for Open Data in the Humanities, Research Organization of Information and Systems, National Institute of Informatics, Tokyo, Japan, 27 February 2023.http://codh.rois.ac.jp/seminar/lexicography-chatgpt-20230227/

Dringó-Horváth, I. 2012. Lernstrategien im Umgang mit digitalen Wörterbüchern [Learning Strategies in Dealing with Digital Dictionaries]. Fremdsprache Deutsch 46: 34-40. [ Links ]

Dringó-Horváth, I. 2017. Digitális szótárak - szótárdidaktika és szótárhasználati szokások [Digital Dictionaries - Dictionary Didactics and Dictionary Use Habits]. Alkalmazott Nyelvtudomány 17(5): 1-27. [ Links ]

Dringó-Horváth, I. 2021. Digitale Wörterbücher - Auswahlkriterien und angepasste Wörterbuchdidaktik. Fremdsprache Deutsch 64. https://fremdsprachedeutschdigital.de/download/fd/FD_64_online_Dringo-Horvath.pdf [ Links ]

Dringó-Horváth, I., K. P. Márkus and B. Fajt. 2020. Szótárhasználati ismeretek vizsgálata német és angol szakot végzettek körében [Dictionary Skills in Teaching English and German as a Foreign Language in Hungary]. Modern Nyelvoktatás 26(4): 16-38. [ Links ]

ECA = European Court of Auditors. 2021. EU Actions to Address Low Digital Skills. Review no. 2.https://www.eca.europa.eu/Lists/ECADocuments/RW21_02/RW_Digital_skills_EN.pdf

Engelberg, S. and L. Lemnitzer. 2009. Lexikographie und Wörterbuchbenutzung. 4th edition. Tübingen: Stauffenburg. [ Links ]

European Commission, Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture. 2019. Key Competences for Lifelong Learning. Publications Office.https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2766/569540

Fóris, Á. 2018. Lexikológiai és lexikográfiai ismeretek magyar (mint idegen nyelv) tanároknak [Lexicology and Lexicography for Teachers of Hungarian (as a Foreign Language)]. Budapest: Károli Gáspár University - L'Harmattan. [ Links ]

Frankenberg-Garcia, A. 2011. Beyond L1-L2 Equivalents: Where Do Users of English as a Foreign Language Turn for Help? International Journal of Lexicography 24(1): 97-123. [ Links ]

Gonda, Zs. 2009. A szótárhasználati kompetencia elsajátítása és fejlesztése [Competence Acquisition and Development in the Use of Dictionaries]. Anyanyelv-pedagógia 2.http://www.anyanyelv-pedagogia.hu/cikkek.php?id=160 [ Links ]

Hartmann, R.R.K. 2001. Teaching and Researching Lexicography. Harlow: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Hartmann, R.R.K. 2013. Resources. Jackson, H. (Ed.). 2013. The Bloomsbury Companion to Lexicography: 373-390. London: Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Jakubíček, M. and M. Rundell. 2023. The End of Lexicography? Can ChatGPT Outperform Current Tools for Post-editing Lexicography? Medveď, M., M. Měchura, C. Tiberius, I. Kosem, J. Kallas, M. Jakubíček and S. Krek (Eds.). 2023. Electronic Lexicography in the 21st Century (eLex 2023): Invisible Lexicography. Proceedings of the eLex 2023 Conference, Brno, 27-29 June 2023: 518-533. Brno: Lexical Computing CZ s.r.o.

Kosem, I., R. Lew, C. Müller-Spitzer, M. Ribeiro Silveira, S. Wolfer et al. 2018. The Image of the Monolingual Dictionary across Europe. Results of the European Survey of Dictionary Use and Culture. International Journal of Lexicography 32(1): 92-114.doi:10.1093/ijl/ecz002 [ Links ]

Lew, R. 2011. Studies in Dictionary Use: Recent Developments. International Journal of Lexicography 24(1): 1-4. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijl/ecq044 [ Links ]

Lew, R. 2016. Dictionaries for Learners of English. Language Teaching 49(2): 291-294. [ Links ]

Lew, R. 2023. ChatGPT as a COBUILD Lexicographer.https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/t9mbu

Lew, R. and G.-M. de Schryver. 2014. Dictionary Users in the Digital Revolution. International Journal of Lexicography 27(4): 341-359.https://doi.org/10.1093/ijl/ecu011 [ Links ]

Lew, R. and K. Galas. 2008. Can Dictionary Skills Be Taught? The Effectiveness of Lexicographic Training for Primary-School-Level Polish Learners of English. Bernal, E. and J. DeCesaris. (Eds.). 2008. Proceedings of the XIII EURALEX International Congress Barcelona, 15-19 July 2008: 1273-1285. Barcelona: Universitat Pompeu Fabra. [ Links ]

Magay, T. 2000. Teaching Lexicography. Heid, U., S. Evert, E. Lehmann and Ch. Rohrer (Eds.). 2000. Proceedings of the 9th EURALEX International Congress EURALEX 2000, Stuttgart, Germany, August 8th-12th, 2000: 443-451. Stuttgart: Institut für Maschinelle Sprachverarbeitung, Universität Stuttgart.

Márkus, K. and É. Szöllősy. 2006. Angolul tanuló középiskolásaink szótárhasználati szokásairól [The Dictionary Use Habits of Hungarian Secondary School Students Learning English as a Foreign Language]. Magay, T. (Ed.). 2006. Szótárak és használóik [Dictionaries and their Users]. Lexikográfiai füzetek 2: 95-116. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

Martynova, I.N. et al. 2015. Modern Approaches to Teaching English Lexicography at the University of Freiburg, Germany. Journal of Sustainable Development 8(3): 220-226. [ Links ]

M. Pintér, T. 2019. Digitális kompetenciák a felsőoktatásban [Digital Competencies in Higher Education]. Modern Nyelvoktatás 25(1): 47-58.

Müller-Spitzer, C. 2014. Textual Structures in Electronic Dictionaries Compared with Printed Dictionaries: A Short General Survey. Gouws, R., U. Heid, W. Schweickard and H. Wiegand (Eds.). 2014. Dictionaries. An International Encyclopedia of Lexicography: Supplementary Volume: Recent Developments with Focus on Electronic and Computational Lexicography: 367-381. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110238136.367 [ Links ]

Müller-Spitzer, C. and A. Koplenig. 2014. Online Dictionaries: Expectations and Demands. Müller-Spitzer, C. (Ed.). 2014. Using Online Dictionaries: 143-188. Lexicographica Series Maior 145. Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110341287.143 [ Links ]

Müller-Spitzer, C., A. Koplenig and S. Wolfer. 2018. Dictionary Usage Research in the Internet Era. Fuertes-Olivera, P.A. (Ed.). 2018. The Routledge Handbook of Lexicography: 715-734. London: Routledge.https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315104942-45 [ Links ]

Müller-Spitzer, C., M.J. Domínguez Vázquez, M. Nied Curcio, I.M. Silva Dias and S. Wolfer. 2018. Correct Hypotheses and Careful Reading Are Essential: Results of an Observational Study on Learners Using Online Language Resources. Lexikos 28: 287-315. [ Links ]

Nesi, H. and R. Haill. 2002. A Study of Dictionary Use by International Students at a British University. International Journal of Lexicography 15(4): 277-305. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijl/15.4.277 [ Links ]

Nesi, H. and P. Meara. 1994. Patterns of Misinterpretation in the Productive Use of EFL Dictionary Definitions. System 22(1): 1-15. [ Links ]

Nied Curcio, M. 2015. Wörterbuchbenutzung und Wortschatzerwerb. Werden im Zeitalter des Smartphones überhaupt noch Vokabeln gelernt? [Dictionary Use and Vocabulary Acquisition. Is Vocabulary Still Learned at All in the Age of the Smartphone?]. Info DaF 5: 445-468. [ Links ]

Nied Curcio, M. 2022. Dictionaries, Foreign Language Learners and Teachers. New Challenges in the Digital Era. Klosa-Kückelhaus, A., S. Engelberg, Ch. Möhrs and P. Storjohann (Eds.). 2022. Dictionaries and Society: Proceedings of the XX EURALEX International Congress: 71-84. Mannheim: IDS-Verlag. [ Links ]

Nkomo, D. 2014. Teaching Lexicography at a South African University. Per Linguam 30(1): 55-70. [ Links ]

P. Márkus, K. 2020a. A szótárhasználat jelene és jövóje a közoktatásban - a nyelvoktatást szabályozó dokumentumok és segédanyagok tükrében [The Present and Future of Dictionary Use in Public Education - In the Light of Documents Governing Language Teaching]. Modern Nyelvoktatás 26(1-2): 59-79. [ Links ]

P. Márkus, K. 2020b. Szótárhasználati munkafüzet - Angol tanulószótár [Dictionary Skills Workbook - English Learner's Dictionary]. Szeged: Maxim.

P. Márkus, K. 2023. Teaching Dictionary Skills. Budapest: L'Harmattan. [ Links ]

P. Márkus, K. and D. Pődör. 2021. Lexikográfia és szótárdidaktika a Károli Gáspár Református Egyetem Angol Nyelvészeti Tanszékén [Lexicography and Dictionary Didactics at the Department of English Linguistics - Károli Gáspár University of the Reformed Church in Hungary]. Iskolakultúra 31(5): 92-107.

P. Márkus, K., B. Fajt and I. Dringó-Horváth. 2023. Dictionary Skills in Teaching English and German as a Foreign Language in Hungary: A Questionnaire Study. International Journal of Lexicography 36(2): 173-194.https://doi.org/10.1093/ijl/ecad004 [ Links ]

Prćić, T. 2020. Teaching Lexicography as a University Course: Theoretical, Practical and Critical Considerations. Lexikos 30(1): 293-320.https://doi.org/10.5788/30-1-1597

Read, A.W. 2023. Dictionary. Encyclopedia Britannica.https://www.britannica.com/topic/dictionary

RFCDC = Council of Europe. 2018. Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture. Volume 2. Descriptors of Competences for Democratic Culture. Council of Europe: Strasbourg.

Rüschoff, B. and D. Wolff. 1999. Fremdsprachenlernen in der Wissensgesellschaft: zum Einsatz der Neuen Technologien in Schule und Unterricht [Foreign Language Learning in the Knowledge Society: On the Use of New Technologies in Schools and Classes]. Ismaning: Hueber. [ Links ]

Sinclair, J. 1984. Lexicography as an Academic Subject. Hartmann, R.R.K. (Ed.). 1984. LEX'eter '83 Proceedings. Papers from the International Conference on Lexicography at Exeter, 9-12 September 1983: 3-12. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer. [ Links ]

Tarp, S. and R. Gouws. 2020. Reference Skills or Human-centered Design: Towards a New Lexicographical Culture. Lexikos 30: 470-498. [ Links ]

Töpel, A. 2015. Das Wörterbuch ist tot - es lebe das Wörterbuch?! [The Dictionary is Dead - Long Live the Dictionary?!] Info DaF 5: 515-534. [ Links ]

Wiegand, H.E., M. Beißwenger, R.H. Gouws, M. Kammerer, A. Storrer and W. Wolski (Eds.). 2010. Wörterbuch zur Lexikographie und Wörterbuchforschung. Band 1 [Dictionary of Lexicography and Dictionary Research. Volume 1]. Berlin: De Gruyter. [ Links ]

Yamada, S. 2010. EFL Dictionary Evolution: Innovations and Drawbacks. Kernerman, I. and P. Bogaards (Eds.). 2010. English Learners' Dictionaries at the DSNA 2009: 147-168. Tel Aviv: K Dictionaries. [ Links ]

Zöfgen, E. 2010. Wörterbuchdidaktik [Dictionary Didactics]. Königs, F.G. and W. Hallet. 2010. Handbuch Fremdsprachendidaktik [Handbook of Foreign Language Didactics]: 107-110. Seelze-Velber: Klett Kallmeyer. [ Links ]

Appendix 1

Guidelines for preparing your analysis and questions to be answered (an abridged version)

(The evaluation guide was compiled by Dóra Pődör.)

Appendix 2

Guidelines for compiling a dictionary skills workbook

Dictionary skills are important because they transfer to the use of other reference books that students will use in their future studies. Unfortunately, many students are not confident about using dictionaries. The Dictionary Skills Workbook should be designed to familiarise students with the information included in the dictionary (you have chosen), as well as to help them quickly and effectively locate words, find meanings, etc.

- compile a workbook for teaching dictionary use with different types of exercises, tasks (focusing on different parts of the dictionary, e.g., pronunciation, grammar, meanings)

- an exercise should naturally include several questions: e.g., if you want to practise phonetic transcription, do it with about 10 words, not just one

- the reproducible exercises/worksheets should provide progressive instruction on topics such as alphabetizing, phonetic spellings, guide words, meanings, etc.

- the workbook will help students learn to use any dictionary successfully

Suggested framework

Topic: e.g., using dictionaries

Level: (use The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR))

Aims: e.g., to develop students' dictionary skills

Age group:

Time:

Material:

Sources:

Contents:

I. Headword

II. Pronunciation

III. Part of speech

IV. Inflection

V. Equivalents

VI. Grammar

VII. Collocations and idioms

VIII. Appendix

The fundamental rule for avoiding plagiarism is to always list your sources. Never use someone else's worksheet unless you explicitly state so in your own workbook.

Appendix 3

Checklist for the evaluation of electric dictionaries (Following Dringó-Horváth 2021)