Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Lexikos

versão On-line ISSN 2224-0039

versão impressa ISSN 1684-4904

Lexikos vol.33 Stellenbosch 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.5788/33-1-1799

LEXICOSURVEY

Evaluating the Usefulness of the Learning Tools in Monolingual Online Dictionaries for Learners of English: Gauging the Preferences of Polish Students of English

Die evaluering van die bruikbaarheid van die aanleerdershulpmiddels in eentalige aanlyn woordeboeke vir aanleerders van Engels: Die bepaling van die voorkeure van Poolse studente van Engels

Bartosz Ptasznik

University of Warmia and Mazury, Olsztyn, Poland (bartosz.ptasznik@uwm.edu.pl)

ABSTRACT

The aim of the report is twofold. First, the learning tools available in monolingual online dictionaries for learners of English are described. Second, an evaluation of the usefulness of the learning tools in online dictionaries is provided. To meet the aims of the present contribution, a survey was administered on 318 Polish students of English. The respondents, who participated in a lecture devoted to the topic of learning tools in online dictionaries, were instructed to complete a questionnaire. A mixed-question format was adopted. In the first part of the questionnaire, the participants had to rate the usefulness of the features of the Macmillan Dictionary on a semantic differential scale of 1-7. In the second part, there were two open-ended questions. The students were asked to name the most and least useful learning tools of the Macmillan Dictionary and explain their choices. The results suggest that English majors studying at a Polish university accord high priority to consulting online learning tools which give them valuable information on collocations, synonyms and semantically related words.

Keywords: lexicography, dictionary use, online dictionary, monolingual learners' dictionary, online learning tools, survey

OPSOMMING

Die doel met hierdie verslag is tweërlei. Eerstens word die aanleerdershulpmiddels wat in eentalige aanlyn woordeboeke vir aanleerders van Engels beskikbaar is, beskryf. Tweedens word 'n evaluering van die bruikbaarheid van die aanleerdershulpmiddels in aanlynwoordeboeke verskaf. Om aan die doelwitte van hierdie bydrae te voldoen, is 'n opname met 318 Poolse studente van Engels gedoen. Die respondente, wat deelgeneem het aan 'n lesing gewy aan die onderwerp van aanleerdershulpmiddels in aanlyn woordeboeke, is versoek om 'n vraelys te voltooi. 'n Formaat van gemengde vrae is gebruik. In die eerste deel van die vraelys moes die deelnemers die kenmerke van die Macmillan Dictionary op 'n semanties gedifferensieerde skaal van 1-7 plaas. In die tweede deel was daar twee oop vrae. Die studente is versoek om die mees en mins bruikbare aanleerdershulpmiddels van die Macmillan Dictionary te lys en om redes te gee vir hul keuses. Die resultate dui daarop dat studente met Engels as hoofvak wat aan 'n Poolse universiteit studeer, hoë prioriteit verleen aan die raadpleeg van aanlyn aanleerdershulpmiddels wat aan hulle waardevolle inligting oor kollokasies, sinonieme en semanties verwante woorde verskaf.

Sleutelwoorde: leksikografie, woordeboekgebruik, aanlyn woordeboek, eentalige aanleerderswoordeboek, aanlyn aanleerdershulpmiddels, opname

1. Introduction

In today's digital world, online dictionaries present us with more information than ever before. Electronic dictionaries are more than just dictionaries. Apart from giving dictionary users the meanings of words, these reference resources can be perceived as repositories of extensive knowledge about the language. This knowledge is shared with users online via different kinds of learning tools, such as videos, language games and quizzes, thesauruses (integrated into dictionaries), blogs, translator tools, exam practice exercises and word of the day or word of the week features. No doubt, learning a foreign language outside a context restricted to book learning can be a more pleasant experience for the language learner. The wide array of online learning tools made available to users on the internet presents ample opportunity for students to further their linguistic skills. But do learners actually consult all of the different tools accompanying present-day online dictionaries? And assuming they do, how often do they decide to use them? Another question pertaining to the present report is how useful are these learning tools for students of English?

2. Learning tools in online dictionaries

The principal source of lexicographic information in an online monolingual learners' dictionary is the dictionary page. Learners of a language consult dictionaries primarily for meaning (Summers 1988: 113-114; Nuccorini 1992: 89-90; Lew 2010: 291-292; Ptasznik 2022: 236-237). In dictionaries, meanings of words are supplemented with example sentences, collocational and grammatical information (grammar codes and grammar patterns, word forms, syntactic class information), pronunciation and frequency information, helpful sense-navigation devices in the form of signposts and menus (appearing with the most polysemous words), synonyms and related words, as well as etymological and derivational information. Additionally, different English monolingual learners' dictionaries have their own unique features, appearing on the dictionary page under specific entries. For example, the Macmillan Dictionary incorporates Metaphor boxes (for words and phrases appearing with their metaphorical meanings), Get It Right! boxes (which illustrate correct usage of words, grammatical patterns, provide examples of grammatically incorrect sentences, etc.) and Expressing yourself boxes (for example, they show what types of phrases one can use when suggesting something politely in a formal context). From the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English, users can advance their knowledge of grammar patterns from Grammar notes and Common Errors notes, whereas the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary provides users with extra Vocabulary Building sections.

Nowadays online dictionaries are equipped with an integrated thesaurus. For example, the Macmillan Thesaurus gives synonyms, antonyms, and related words which form a lexical set of words for specific words and concepts. In the Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, the Merriam-Webster Thesaurus presents language information in the form of synonyms and similar words, antonyms and near antonyms, the Synonym Chooser feature (which explains the differences between selected synonyms and similar words, for example, eager and anxious), as well as phrases containing the searched word (eager beaver for eager) and articles related to the searched word ('When Pigs Fly' and Other Barnyard Idioms for the word buy).

In the light of the fact that correct use of collocations1 creates a serious challenge to language learners (Bahns and Eldaw 1993: 101; Herbst 2010: 225; Lew and Radłowska 2010: 43; Chan 2012: 69), dictionaries may additionally incorporate corpus-based collocations dictionaries tailored to suit learners' productive needs. To give an example, the Macmillan Collocations Dictionary of the Macmillan Dictionary supplies dictionary users with a wide range of strong collocates for core vocabulary. Entries, which are organized by grammar and meaning, include collocations for different kinds of grammatical relations (adjective + noun, verb + noun, noun + verb, adverb + adjective, etc.) and may also provide valuable usage notes (see entries for recognize2 and vanish). Importantly, the Macmillan Collocations Dictionary has been geared to meet the needs of all types of learners, regardless of their proficiency levels.

To increase their attractiveness, publishers supply online dictionaries with translation tools. For example, the Cambridge Dictionary is accompanied by a Translator3 tool. This multilingual translation learning tool allows one to type the text in the box and get instant translations for selected texts. And there is a broad range of possibilities: translations are performed for a fairly high number of different languages, including Arabic, Catalan, Filipino, Hindi, Korean, Polish and Thai. In the Translator tool of the Collins Online Dictionary, more than 30 languages are available.

The provision of video presentations in dictionaries for language learning purposes is standard practice nowadays. Learners have the opportunity to listen to native speakers of English elaborate on a chosen topic. Video material with a special focus on The Schwa, Lay vs. Lie, Sneaked vs. Snuck, On Contractions of Multiple Words, A Look at Uncommon Onomatopoeia, What is an Eggcorn?, How a Word Gets into the Dictionary, Ending a Sentence with a Preposition and a plethora of others can be accessed from the Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary website. The videos that have been made available at MacmillanDictionary.com are concerned with Real Grammar (e.g. Split Infinitives), Real Vocabulary (e.g. Uninterested vs. Disinterested) and Real Word English (e.g. Politeness) topics. The Collins Online Dictionary provides audiovisual material under the Learn English, Video pronunciations and Build your vocabulary sections.

Language games and quizzes make dictionaries more appealing. Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary features various quizzes to test learners' knowledge of herbs and spices, flowers, weather words, colors, fashionable words, Game of Thrones words, monsters, obscure shapes, finance words, words of snow and ice and farm idioms, to name just a few, while the Macmillan Dictionary develops students' knowledge through language quizzes (e.g. breeds of dog, royal words, figures of speech), games (e.g. irregular verb wheel) and puzzles (e.g. American culture wordsearch, Halloween wordsearch).

Another frequently-used learning tool in dictionaries is the language blog. For example, the Macmillan Dictionary Blog incorporates diary-style posts for specific words, including supplementary information with regards to their meaning, usage (grammar), etymology and spelling.

By and large, publishers also endeavor to develop a closer bond between the user and lexicographer. The Macmillan Dictionary includes the Open Dictionary feature, which enables users to participate in the dictionary-making process, by creating the opportunity for learners to suggest words that could be added to the dictionary, given their frequently-recurring usage in the language. Whether the word or phrase will eventually be incorporated into the dictionary or not is a decision solely made by lexicographers.

Other learning tools include: practice tests and exercises, word lists, buzzwords, trending words, the word of the day feature, English grammar explanations, text checkers, reference materials, etc.

3. Aims of the survey

The aims of the present survey are twofold. First, selected types of online learning tools accompanying English monolingual learners' dictionaries will be described (see section devoted to the learning tools in online dictionaries). Second, the usefulness of these online learning tools will be explored by examining the preferences and habits of English majors at the University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn, Poland.

4. Method, participants and procedure

The online version of the Macmillan Dictionary was selected for the evaluation of the usefulness of the learning tools in online dictionaries. This decision rested on two premises. First, in a previous survey of dictionary preferences (Ptasznik 2022), examining the lexical resources that students of English choose to consult, it was found that the Macmillan Dictionary is the second most frequently consulted British English monolingual learners' dictionary among the students participating in the survey (the respondents of the previous survey were provided with five different answer options, which also included the Cambridge Dictionary, Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary, Collins Online Dictionary and Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English). In order to answer the purpose of the survey, it was assumed that using this particular reference source would increase the reliability and validity of the evaluation of specific online learning tools, given the students' familiarity with this digital resource. Second, the Macmillan Dictionary presents dictionary users with a comprehensive range of learning tools available online at the click of a mouse. Apart from using the dictionary page, users can learn English by accessing the Macmillan Collocations Dictionary, Macmillan Thesaurus, Macmillan Dictionary Blog, Language Quizzes, Games and Puzzles, Videos (Real Grammar, Real Vocabulary and Real World English videos), Buzzwords and Trending Words. Importantly, the abovementioned language learning tools share the common features of the learning tools in the remaining monolingual learners' dictionaries that are available online. All things considered, it was the Macmillan Dictionary that was deemed to be the most suitable dictionary for the evaluation of the usefulness of the learning tools in online dictionaries.

318 English majors from the University of Warmia and Mazury participated in the survey. The participants were males and females, who were native speakers of Polish. Their age varied between 19-24. The respondents were first-year, second-year, third-year, fourth-year and fifth-year students of English (full-time studies). Their English proficiency level ranged from upper-intermediate to advanced (level B2 and C1 by the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages standards). The students made a voluntary decision to participate in the survey. The protection of sensitive personal information was achieved through data anonymization.

To meet the aims of the research, it was divided into two parts. In the first part, the students were asked to attend a one-hour lecture devoted to the topic of learning tools in online dictionaries. Several lectures were given, with a turnout of approximately 40-70 students for each separate lecture. The lectures were delivered by the researcher at the Faculty of Humanities of the university. As mentioned above, the Macmillan Dictionary was selected for the evaluation of the usefulness of the learning tools in online dictionaries. During the lecture, it was explained in detail to the study participants what kinds of learning tools have been made available to dictionary users by Macmillan Dictionary publishers: Dictionary page, Macmillan Collocations Dictionary, Macmillan Thesaurus, Macmillan Dictionary Blog, Language Quizzes, Games and Puzzles, Videos (Real Grammar, Real Vocabulary and Real World English videos), Buzzwords, Open Dictionary (entries4) and Trending Words. All of these learning tools were discussed in as much detail as possible within the required one-hour time frame, with specific learning tools being displayed to the participants on screen. Taking into account the fact that Polish students of English are familiar with this specific digital product (Ptasznik 2022), the lecture merely served as a reminder of what specific learning tools can be accessed from the dictionary. Examples of similar learning tools from the remaining monolingual learners' dictionaries were provided during the course of the lecture. For example, the following features from the Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary were presented to the students: Merriam-Webster Thesaurus, Games & Quizzes, Videos, Word of the Day, Words at Play. At the end of the lecture, the students were allowed to ask questions.

Given the usefulness of surveys in dictionary-user research (see Kosem et al. 2019) and the advantages of designing a questionnaire (see Jackson and Furnham 2000: 5; Mackey and Gass 2005: 94-96; Blaxter et al. 2006: 79; Debois 2019), the students were asked to fill out a questionnaire in the second part of the research. A pencil-and-paper format was selected for the questionnaire. To meet the aims of the survey, a mixed-question format was adopted (quantitative and qualitative analysis). In the questionnaire, in order to assess the students' opinions, attitudes and experiences, the participants had to rate the following features of the Macmillan Dictionary on a semantic differential scale of 1-7 (lower scale points indicated that a specific learning tool was less useful, higher scale points indicated that a specific learning tool was more useful, see Appendix A and Appendix B): Dictionary page, Macmillan Collocations Dictionary, Macmillan Thesaurus, Macmillan Dictionary Blog, Language Quizzes, Games and Puzzles, Open Dictionary, Videos, Buzzwords, Trending Words and Red Words and Stars. Open-ended questions were used sparingly (two open-ended questions were included). The students were supposed to name the most and least useful features of the Macmillan Dictionary, and explain their choices. To increase comprehension of the survey questions, the ten questionnaire items and two open-ended questions were drafted in the students' native language. To avoid confusion, technical language was not used in the questionnaire (Lew 2002, 2004). The students were given twenty minutes to complete the task (for more on the optimum duration of surveys see Macer and Wilson 2013, as cited in Brace 2018: 49-50). They had five minutes to rate the learning tools of the Macmillan Dictionary and an additional fifteen minutes to answer two open-ended questions

5. Results, findings and discussion

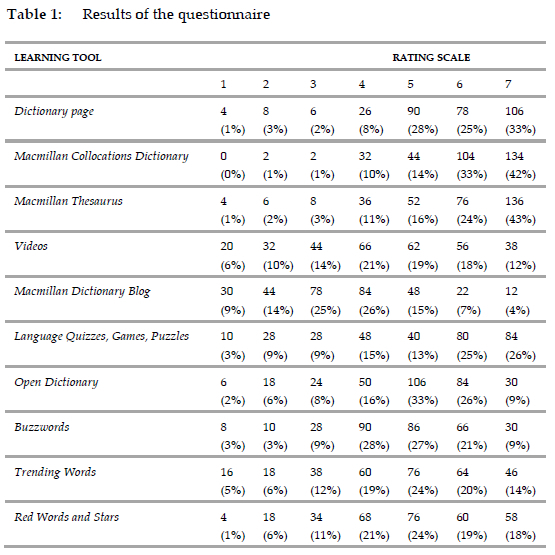

The results of the questionnaire are given in Table 1. In the table, the number of responses of the respondents are provided. Additionally, the results are expressed in percentage terms (scale points are numbered from 1-7, scale points with a higher value indicate that a specific learning tool is more useful, scale points with a lower value indicate that a particular learning tool is less useful.).

The findings invite some general conclusions. The data obtained from 318 participants suggest that upper-intermediate and advanced students of English highly value learning tools that provide them with information about collocations and synonyms (and related words). In the present survey, both the Macmillan Collocations Dictionary and Macmillan Thesaurus received the highest ratings from the respondents. As many as 43% (136 students) of the students gave the Macmillan Thesaurus a rating of 7, while the Macmillan Collocations Dictionary received the same rating from a slightly lower number of students (134 students). The survey participants were satisfied with the Dictionary page. More than three quarters (86%) of the students held the view that the Dictionary page was useful, by giving it a rating within the range of 5-7. Given that dictionary users consult dictionaries primarily for meaning, and taking into account various user-friendly features of the dictionary, such as entry navigation devices in the form of menus5 (used for the most polysemous words, for example, under the entry see), hyperlinking, recordings of sounds and noises (see Lew 2010: 297; Jackson 2018: 545; Heuberger 2020: 407), customization (e.g. show/hide further synonyms and/or related words), grammar patterns, Metaphor Boxes, and the incorporation of example sentences, this finding does not come as a surprise. In addition, it appears that English majors from Polish universities appreciate different types of language games and quizzes that can be accessed from an online dictionary. The data show that the students rated Language Quizzes, Games, Puzzles as a more useful learning tool than all the remaining features, that is the Macmillan Dictionary Blog, Videos, Buzzwords, Open Dictionary, Red Words and Stars and Trending Words. 51% of the students gave Language Quizzes, Games, Puzzles a rating of either 6 or 7. By comparison, this figure came close to reaching the ratings of the Dictionary page, with 58% of the respondents giving the Dictionary page a rating of 6 or 7. The participants found the Open Dictionary entries quite appealing, with more than 50% of the respondents giving it a rating of 5 or 6. The students rated the Macmillan Dictionary Blog as the least useful learning tool of the Macmillan Dictionary. More than half of the students (51%) gave it a rating of 3 or 4.

To elicit more detailed responses on the usefulness of the learning tools in the Macmillan Dictionary, the students were asked to answer the following questions (two open-ended questions):

(1) Which features of the Macmillan Dictionary are the most useful learning tools in your opinion? Why?

(2) Which features of the Macmillan Dictionary are the least useful learning tools in your opinion? Why?

A general consensus was reached by the survey participants on the perception of the usefulness of the Macmillan Collocations Dictionary and Macmillan Thesaurus. The majority of the students answered that the Macmillan Collocations Dictionary and Macmillan Thesaurus were the most useful learning tools, given their significance in language production tasks. Most of the students mentioned that they would especially resort to using these tools when completing their writing assignments, such as: paragraph and essay writing, as well as writing BA and MA dissertations. In addition, the participants reported that they would consult the Macmillan Collocations Dictionary and Macmillan Thesaurus when preparing an oral presentation, as both learning tools have considerable potential for vocabulary building. "Getting ready for a job interview at multinational companies" was also high on their list. No doubt, using collocations correctly can be a mammoth task for language learners (Bahns and Eldaw 1993: 101; Herbst 2010: 225; Lew and Radłowska 2010: 43; Webb and Kagimoto 2011: 260-261; Chan 2012: 69; Daskalovska 2015: 130-131). Students can sense that acquiring more knowledge about collocations plays an important role in the process of language learning. It is essential that they learn to use words naturally in productive mode. Without sufficient collocational knowledge, production becomes seriously affected. Similarly, using synonyms correctly in the target language is equally important.

Overall, the Dictionary page was credited with consistency (of how lexicographic information is organized within entries) and transparency of the presentation of information. Many of the students lauded it for lexicographic content. The students appreciated the incorporation of entry menus for polysemous words, hyperlinking of words within definitions, recordings of sounds and noises and Metaphor Boxes (for an example, see the Metaphor Box under the entry illness). Some of the participants, however, believed that fewer example sentences can be accessed from this reference source than from the remaining monolingual online dictionaries for learners of English, such as the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English or Collins Online Dictionary, which provide users with a plethora of supplementary corpus examples in the extra sections of entries. Others, however, put forward the argument that the number of examples included in Macmillan Dictionary entries is sufficient, and that incorporating more lexicographic data could lead to learners becoming overwhelmed with an excess of information. Such an argument has also been presented in the literature (L'Homme and Cormier 2014: 333; Gouws and Tarp 2017: 394; Frankenberg-Garcia 2020: 32). A handful of the participants also said that recorded pronunciations of headwords for both British and American English are not as easily accessible as in, for example, the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary, where both types of pronunciation variants appear at the top of a single entry. To get access to comprehensive information on different pronunciation variants, one needs to obtain this type of information from an appropriate link located at the bottom of the Macmillan Dictionary page, or change the default settings for the dictionary.

The Macmillan Dictionary Blog was assessed by the students as the least useful learning tool of the Macmillan Dictionary. The primary reason for this appears to be the fact that dictionary users want to acquire information as quickly as possible. Taking into account the fact that the pool of students selected for the study were digital natives, growing up with various technologies and learning tools available and easily-accessible in their digital-rich environment, it is perhaps not surprising that a fairly high number of the students rated this specific feature of the dictionary as being less beneficial than the remaining online learning tools. When learning the language online, students are not necessarily keen on scanning through larger fragments of text. The average dictionary user wants to build on his knowledge with the minimum of effort. Nowadays information is available on the internet at the click of a mouse. Dictionary users value their time and ascribe much importance to faster dictionary consultation (Bogaards 1998: 561; Chen 2010: 292; Chan 2012: 87; Knežević et al. 2021: 7), and that is why learners are likely to launch less time-consuming information search strategies rather than engage in longer reading.

As for the remaining learning tools, in their open-ended feedback the students appeared to be excited that modern online dictionaries give them access to information about neologisms or regional varieties, as well as words that are being increasingly used by the speakers of the language, but which have yet to be incorporated into the dictionary. Hence, some of the students were full of praise for Buzzwords and the Open Dictionary entries that have been made available to the users. This is proof that such features of dictionaries can generate an avid interest in learning the target language. There is no denying that these learning tools unleash creativity and build learners' vocabulary which could be particularly important when communicating in more informal contexts. Especially more advanced learners strive for such knowledge. Videos and Language Quizzes, Games, Puzzles were assessed as being useful teaching materials for the EFL classroom, given that selected students had been planning to embark on a teaching career after the completion of their studies. Quite a few of the students wondered why more videos had not been uploaded to MacmillanDictionary.com (for a few possible explanations, see Heuberger 2020: 408). Others suggested that additional topics be covered in the Videos, such as verb complementation patterns (for example, intransitive, monotransitive and ditransitive verbs, reflexive and reciprocal verbs, verbs followed by that-clauses, verbs used with prepositional and adverbial phrases), verbs commonly used in the passive, conditional sentences, etc. According to the students, video clips with a specific focus on more challenging verbs in the English language from the point of view of language production (e.g. suggest, recommend, demand, explain) would be a valuable addition to the feature. Red Words and Stars were regarded by many as a positive feature of the Macmillan Dictionary. Some of the students, however, admitted that they never paid attention to frequency information in a dictionary, as they consulted dictionaries solely for meaning and collocations. Given that highlighting core vocabulary (red words vs. black words) in dictionaries raises learners' awareness about which words are more important from a productive, as well as receptive perspective, it must be contended that it is the role of the teachers to make their students more aware of the practical significance of the presence of this feature in monolingual learners' dictionaries.

6. Conclusion

The aim of the report was to gauge the preferences and habits of Polish students of English regarding their use of the learning tools accompanying monolingual online dictionaries. The survey participants were asked to indicate their degree of satisfaction with selected online learning tools on a seven-point scale and answer two open-ended questions. Considering the findings of the present work, it may be concluded that Polish learners of English representing an upper-intermediate and advanced level think highly of online learning tools designed to supply users with pertinent information on collocations, synonyms and related words. This finding implies that English majors studying at Polish universities place much importance on language production (specifically, academic writing) in the process of foreign language learning.

Endnotes

1. See Laufer (2011), Laufer and Waldman (2011) and Chen (2017) for more on collocations in production. See Herbst (1996) and Dziemianko (2014) for more on encouraging collocational awareness among learners.

2. From the entry recognize in the Macmillan Collocations Dictionary, one learns that there is a marked preference for passivization when the verb recognize is used in an adverb + verb combination.

3. See: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/translate/.

4. For more on crowdsourcing and user-generated content see Rundell (2012: 80-81).

5. For more information on menus in dictionaries see Rundell (2007), Lew and Tokarek (2010), Ptasznik (2015).

References

Online dictionaries

Cambridge Dictionary. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/. Accessed 24 November, 2022.

Collins Online Dictionary. https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english. Accessed 24 November, 2022.

Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English. http://www.ldoceonline.com/. Accessed 24 November, 2022.

Macmillan Dictionary. http://www.macmillandictionary.com. Accessed 24 November, 2022.

Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/. Accessed 24 November, 2022.

Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary. https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/. Accessed 24 November, 2022.

Paper dictionaries

Rundell, M. (Ed.). 2007. Macmillan English Dictionary for Advanced Learners. (MED2). Second edition. Oxford: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Other references

Bahns, J. and M. Eldaw. 1993. Should We Teach EFL Students Collocations? System 21(1): 101-114. https://doi.org/10.1016/0346-251X(93)90010-E. Accessed 17 November, 2022. [ Links ]

Blaxter, L., C. Hughes and M. Tight. 2006. How to Research. Third edition. Maidenhead: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Bogaards, P. 1998. Scanning Long Entries in Learner's Dictionaries. Fontenelle, T., P. Hiligsmann, A. Michiels, A. Moulin and S. Theissen (Eds.). 1998. EURALEX '98 Actes/Proceedings: 555-563. Liège: English and Dutch Departments, University of Liège. [ Links ]

Brace, I. 2018. Questionnaire Design: How to Plan, Structure and Write Survey Material for Effective Market Research. Fourth edition. London: Kogan Page. [ Links ]

Chan, A.Y.W. 2012. Cantonese ESL Learners' Use of Grammatical Information in a Monolingual Dictionary for Determining the Correct Use of a Target Word. International Journal of Lexicography 25(1): 68-94. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijl/ecr014. Accessed 28 January, 2023. [ Links ]

Chen, Y. 2010. Dictionary Use and EFL Learning. A Contrastive Study of Pocket Electronic Dictionaries and Paper Dictionaries. International Journal of Lexicography 23(3): 275-306. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijl/ecq013. Accessed 16 January, 2023. [ Links ]

Chen, Y. 2017. Dictionary Use for Collocation Production and Retention: A CALL-based Study. International Journal of Lexicography 30(2): 225-251. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijl/ecw005. Accessed 5 January, 2023. [ Links ]

Daskalovska, N. 2015. Corpus-based versus Traditional Learning of Collocations. Computer Assisted Language Learning 28(2): 130-144. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2013.803982. Accessed 9 April, 2023. [ Links ]

Debois, S. 2019. 10 Advantages and Disadvantages of Questionnaires. https://surveyanyplace.com/blog/questionnaire-pros-and-cons/. Accessed 7 April, 2023.

Dziemianko, A. 2014. On the Presentation and Placement of Collocations in Monolingual English Learners' Dictionaries: Insights into Encoding and Retention. International Journal of Lexicography 27(3): 259-279. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijl/ecu012. Accessed 23 September, 2022. [ Links ]

Frankenberg-Garcia, A. 2020. Combining User Needs, Lexicographic Data and Digital Writing Environments. Language Teaching 53(1): 29-43. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444818000277. Accessed 21 December, 2022. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. and S. Tarp. 2017. Information Overload and Data Overload in Lexicography. International Journal of Lexicography 30(4): 389-415. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijl/ecw030. Accessed 22 February, 2023. [ Links ]

Herbst, T. 1996. On the Way to the Perfect Learners' Dictionary: A First Comparison of OALD5, LDOCE3, COBUILD2 and CIDE. International Journal of Lexicography 9(4): 321-357. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijl/9.4.321. Accessed 17 December, 2022. [ Links ]

Herbst, T. 2010. Valency Constructions and Clause Constructions or how, if at all, Valency Grammarians might Sneeze the Foam off the Cappuccino. Schmid, H.-J. and S. Handl (Eds.). 2010. Cognitive Foundations of Linguistic Usage Patterns: 225-256. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter Mouton. [ Links ]

Heuberger, R. 2020. Monolingual Online Dictionaries for Learners of English and the Opportunities of the Electronic Medium: A Critical Survey. International Journal of Lexicography 33(4): 404-416. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijl/ecaa018. Accessed 18 January, 2023. [ Links ]

Jackson, H. 2018. English Lexicography in the Internet Era. Fuertes-Olivera, P.A. (Ed.). 2018. The Routledge Handbook of Lexicography: 540-553. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Jackson, C.J. and A. Furnham. 2000. Designing and Analysing Questionnaires and Surveys. A Manual for Health Professionals and Administrators. London: Whurr Publishers. [ Links ]

Knežević, L., S. Halupka-Rešetar, I. Miškeljin and M. Milić. 2021. Millennials as Dictionary Users: A Study of Dictionary Use Habits of Serbian EFL Students. SAGE Open 11(2): 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211008422. Accessed 29 March, 2023. [ Links ]

Kosem, I., R. Lew, C. Müller-Spitzer, M.R. Silveira, S. Wolfer et al. 2019. The Image of the Monolingual Dictionary across Europe. Results of the European Survey of Dictionary Use and Culture. International Journal of Lexicography 32(1): 92-114. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijl/ecy022. Accessed 15 February, 2023. [ Links ]

Laufer, B. 2011. The Contribution of Dictionary Use to the Production and Retention of Collocations in a Second Language. International Journal of Lexicography 24(1): 29-49. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijl/ecq039. Accessed 14 January, 2023. [ Links ]

Laufer, B. and T. Waldman. 2011. Verb-Noun Collocations in Second Language Writing: A Corpus Analysis of Learners' English. Language Learning 61(2): 647-672. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2010.00621.x. Accessed 13 February, 2023. [ Links ]

Lew, R. 2002. Questionnaires in Dictionary Use Research: A Reexamination. Braasch, A. and C. Povlsen (Eds.). 2002. Proceedings of the Tenth EURALEX International Congress, EURALEX 2002, Copenhagen, Denmark, August 12-17, 2002, Vol.1: 267-271. Copenhagen: Center for Sprogteknologi, Copenhagen University.

Lew, R. 2004. Which Dictionary for Whom? Receptive Use of Bilingual, Monolingual and Semi-Bilingual Dictionaries by Polish Learners of English. Poznań: Motivex. [ Links ]

Lew, R. 2010. Multimodal Lexicography: The Representation of Meaning in Electronic Dictionaries. Lexikos 20: 290-306. https://doi.org/10.5788/20-0-144. Accessed 1 January, 2023. [ Links ]

Lew, R. and M. Radłowska. 2010. Navigating Dictionary Space: The Findability of English Collocations in a General Learner's Dictionary (LDOCE4) and Special-purpose Dictionary of Collocations (OCD). Ciuk, A. and K. Molek-Kozakowska (Eds.). 2010. Exploring Space: Spatial Notions in Cultural, Literary and Language Studies. Volume 2: Space in Language Studies: 34-47. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [ Links ]

Lew, R. and P. Tokarek. 2010. Entry Menus in Bilingual Electronic Dictionaries. Granger, S. and M. Paquot (Eds.). 2010. eLexicography in the 21st Century: New Challenges, New Applications: 193-202. Louvain-la-Neuve: Cahiers du CENTAL. [ Links ]

L'Homme, M.-C. and M.C. Cormier. 2014. Dictionaries and the Digital Revolution: A Focus on Users and Lexical Databases. International Journal of Lexicography 27(4): 331-340. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijl/ecu023. Accessed 22 November, 2022. [ Links ]

Macer, T. and S. Wilson. 2013. A Report on the Confirmit Market Research Software Survey. https://www.quirks.com/articles/a-report-on-the-confirmit-market-research-software-survey-1. Accessed 7 April, 2023.

Mackey, A. and S.M. Gass. 2005. Second Language Research: Methodology and Design. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Nuccorini, S. 1992. Monitoring Dictionary Use. Tommola, H., K. Varantola, T. Salmi-Tolonen and J. Schopp (Eds.). 1992. EURALEX '92 Proceedings. Papers Submitted to the 5th EURALEX International Congress, Tampere 1992: 89-102. Tampere: Department of Translation Studies, University of Tampere.

Ptasznik, B. 2015. Signposts and Menus in Monolingual Dictionaries for Learners of English. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM. [ Links ]

Ptasznik, B. 2022. After the Digital Revolution: Dictionary Preferences of English Majors at a European University. Lexikos 32: 220-249. https://doi.org/10.5788/32-1-1721. Accessed 31 January, 2023. [ Links ]

Rundell, M. 2012. It Works in Practice but Will it Work in Theory? The Uneasy Relationship between Lexicography and Matters Theoretical. Fjeld, R.V. and J.M. Torjusen (Eds.). 2012. Proceedings of the XV EURALEX International Congress, 7-11 August, 2012, Oslo: 47-92. Oslo: Department of Linguistics and Scandinavian Studies, University of Oslo.

Summers, D. 1988. The Role of Dictionaries in Language Learning. Carter, R. and M. McCarthy (Eds.). 1988. Vocabulary and Language Teaching: 111-125. London: Longman. [ Links ]

Webb, S. and E. Kagimoto. 2011. Learning Collocations: Do the Number of Collocates, Position of the Node Word, and Synonymy Affect Learning? Applied Linguistics 32(3): 259-276. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amq051. Accessed 9 April, 2023. [ Links ]

APPENDIX A: Original text of the questionnaire

ANKIETA

Dziękuję za udział w ankiecie. Ankieta składa się z dwóch części i jest anonimowa. Proszę udzielić odpowiedzi na następujące pytania:

CZĘŚĆ 1

1. Jak oceniasz użyteczność Dictionary page w skali 1-7?

Mniej użyteczny - 1-2-3-4-5-6 - 7 - Bardziej użyteczny

2. Jak oceniasz użyteczność Macmillan Collocations Dictionary w skali 1-7?

Mniej użyteczny - 1-2-3-4-5-6 - 7 - Bardziej użyteczny

3. Jak oceniasz użyteczność Macmillan Thesaurus w skali 1-7?

Mniej użyteczny - 1-2-3-4-5-6 - 7 - Bardziej użyteczny

4. Jak oceniasz użyteczność Videos w skali 1-7?

Mniej użyteczny - 1-2-3-4-5-6 - 7 - Bardziej użyteczny

5. Jak oceniasz użyteczność Macmillan Dictionary Blog w skali 1-7?

Mniej użyteczny - 1-2-3-4-5-6 - 7 - Bardziej użyteczny

6. Jak oceniasz użyteczność Language Quizzes, Games, Puzzles w skali 1-7?

Mniej użyteczny - 1-2-3-4-5-6 - 7 - Bardziej użyteczny

7. Jak oceniasz użyteczność Open Dictionary w skali 1-7?

Mniej użyteczny - 1-2-3-4-5-6 - 7 - Bardziej użyteczny

8. Jak oceniasz użyteczność Buzzwords w skali 1-7?

Mniej użyteczny - 1-2-3-4-5-6 - 7 - Bardziej użyteczny

9. Jak oceniasz użyteczność Trending Words w skali 1-7?

Mniej użyteczny - 1-2-3-4-5-6 - 7 - Bardziej użyteczny

10. Jak oceniasz użyteczność Red Words and Stars w skali 1-7?

Mniej użyteczny - 1-2-3-4-5-6 - 7 - Bardziej użyteczny

CZĘŚĆ 2

1. Które cechy słownika Macmillan Dictionary są według Ciebie najbardziej pożytecznymi do nauki języka angielskiego? Dlaczego?

2. Które cechy słownika Macmillan Dictionary są według Ciebie najmniej pożytecznymi do nauki języka angielskiego? Dlaczego?

APPENDIX B: English translation of the questionnaire

QUESTIONNAIRE

Thank you for taking the time to fill out the questionnaire. The questionnaire consists of two parts and is anonymous. Please answer the following questions:

PART 1

1. How do you rate the usefulness of the Dictionary page on a scale of 1-7?

Less useful - 1-2-3-4-5-6 - 7 - More useful

2. How do you rate the usefulness of the Macmillan Collocations Dictionary on a scale of 1-7?

Less useful - 1-2-3-4-5-6 - 7 - More useful

3. How do you rate the usefulness of the Macmillan Thesaurus on a scale of 1-7?

Less useful - 1-2-3-4-5-6 - 7 - More useful

4. How do you rate the usefulness of Videos on a scale of 1-7?

Less useful - 1-2-3-4-5-6 - 7 - More useful

5. How do you rate the usefulness of the Macmillan Dictionary Blog on a scale of 1-7?

Less useful - 1-2-3-4-5-6 - 7 - More useful

6. How do you rate the usefulness of Language Quizzes, Games, Puzzles on a scale of 1-7?

Less useful - 1-2-3-4-5-6 - 7 - More useful

7. How do you rate the usefulness of the Open Dictionary on a scale of 1-7?

Less useful - 1-2-3-4-5-6 - 7 - More useful

8. How do you rate the usefulness of Buzzwords on a scale of 1-7?

Less useful - 1-2-3-4-5-6 - 7 - More useful

9. How do you rate the usefulness of Trending Words on a scale of 1-7?

Less useful - 1-2-3-4-5-6 - 7 - More useful

10. How do you rate the usefulness of Red Words and Stars on a scale of 1-7?

Less useful - 1-2-3-4-5-6 - 7 - More useful

PART 2

1. Which features of the Macmillan Dictionary are the most useful learning tools in your opinion? Why?

2. Which features of the Macmillan Dictionary are the least useful learning tools in your opinion? Why?