Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Lexikos

On-line version ISSN 2224-0039

Print version ISSN 1684-4904

Lexikos vol.32 spe 2 Stellenbosch 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.5788/32-3-1734

ARTIKELS/ARTICLES

How School Dictionaries Treat Human Reproductive Organs, and Recommendations for South African Primary School Dictionaries

Die hantering van die menslike voortplantingsorgane in skoolwoordeboeke, en aanbevelings vir Suid-Afrikaanse primêreskoolwoordeboeke

Lorna Hiles Morris

Department of Afrikaans and Dutch, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa. (lorna@lemma.co.za)

ABSTRACT

This paper is a pilot study that investigates options for treating human reproductive organs in primary school dictionaries in South Africa, with particular emphasis on illustrations. The need for this study was made apparent during research into the design of an electronic school dictionary, where some learners expressed concern about younger children being exposed to "inappropriate" illustrations in school dictionaries. This article is placed in the South African context and shows how this is a sensitive and relevant topic in South Africa, due to the different cultures that are represented. The article shows how South African school dictionaries currently treat these words, and investigates whether they should be treated any differently. The study includes interviews with primary school teachers and parents, and contains descriptions of existing school dictionary entries, both electronic and print. Literature on the following aspects is covered: taboo topics in dictionaries, cultural aspects of sex education in South Africa, and sex education in primary schools globally. The article will show why it is important to treat these terms in a school dictionary in a clear and unambiguous way, despite this causing potential discomfort to some users. The article will conclude with recommendations for the treatment of human reproductive organs in primary schools, as well as recommendations for further research in this area.

Keywords: culture, human reproductive organs, pedagogical lexicography, primary school dictionary, school dictionary, sex organs, sexuality education, taboo

OPSOMMING

Hierdie artikel is 'n loodsstudie wat die opsies vir die hantering van menslike voort-plantingsorgane in primêreskoolwoordeboeke in Suid-Afrika ondersoek, met besondere aandag aan illustrasies. Die noodsaak vir hierdie studie het duidelik geword tydens navorsing oor die ontwerp van 'n elektroniese skoolwoordeboek waar sommige leerlinge hul kommer oor jonger kinders wat blootgestel word aan "onvanpaste" illstrasies in skoolwoordeboeke, uitgespreek het. Die artikel word binne die Suid-Afrikaanse konteks geplaas en daar word daarop gewys dat dit weens die verskillende kulture wat verteenwoordig word, 'n sensitiewe en relevante onderwerp in Suid-Afrika is. Daar word aangetoon hoe Suid-Afrikaanse skoolwoordeboeke hierdie woorde tans hanteer, en daar word ondersoek of hulle op ander maniere hanteer behoort te word. Die studie sluit onderhoude met primêreskoolonderwysers en -ouers in, en bevat beskrywings van bestaande skoolwoordeboekinskrywings, in elektroniese sowel as gedrukte formaat. Literatuur rakende die volgende aspekte word gedek: taboeonderwerpe in woordeboeke, kulturele aspekte van seks-opvoeding in Suid-Afrika, en seksopvoeding in primêre skole wêreldwyd. Die artikel sal aantoon waarom dit belangrik is om hierdie terme in 'n skoolwoordeboek op 'n duidelike en ondubbelsinnige manier te hanteer, al veroorsaak dit moontlike ongemak vir sommige gebruikers. Daar word afgesluit met aanbevelings vir die hantering van die menslike voortplantingsorgane in primêre skole, asook aanbevelings vir verdere navorsing op hierdie gebied.

Sleutelwoorde: kultuur, menslike voortplantingsorgane, pedagogiese leksikografie, primêreskoolwoordeboeke, skoolwoordeboek, seksorgane, geslagsopvoeding, taboes

1. Introduction

During research into the design of an electronic school dictionary, where primary school learners were asked whether they would like each article in a school dictionary to be illustrated, three of the learners expressed concern about "inappropriate" or "underage" illustrations. The question in the questionnaire was "Do you think every entry should be illustrated (have pictures)?" This question had tick boxes indicating yes or no, and was followed by "Why or why not?" The three learners' comments were: "Because there might be underage words" (Grade 5), "No, because sometimes there might be pictures that are inappropriate for children to see" (Grade 6), and "It might be inappropriate" (Grade 5). These learners were in Grade 5 and 6 and one can only assume that the illustrations they were referring to were sex organs. This led to the research question for this study: how should human reproductive organs be treated in school dictionaries, and more specifically, how should they be illustrated in an illustrated school dictionary? It is noted that due to the nature of these illustrations, they would all be drawings, and not photographs.

The aims of this paper are to establish how school dictionaries currently treat human reproductive organs, and how primary school teachers and parents would like them to be treated. The study is set in a South African context with literature covering different cultural attitudes to sexuality education at school. This paper will conclude with recommendations for primary school dictionaries, as well as for further research.

2. Methodology

The aims of this study are to show how human reproductive organs are being treated in primary school dictionaries, and then to provide recommendations as to how they should be treated. This study also shows why this is important, especially in the context of South African primary schools.

This study makes use of three methods of data collection, namely a literature review, questionnaires answered by teachers and parents of primary school children, and an analysis and comparison of existing school dictionaries.

The literature discussed in this paper covers the following areas: illustrations in dictionaries, taboo topics in dictionaries, sex education in primary schools, and cultural aspects of sexuality education in southern Africa. The literature shows why this is a relevant topic and why it is necessary to make these decisions that will benefit the learners in South African primary schools.

Teachers from two Western Cape primary schools were given questionnaires about whether their school includes sexuality education in the curriculum, whether they would want human reproductive organs treated in a dictionary, and how they would like to see them illustrated. The schools are both co-ed schools, with one being a private school and one being a government school. Parents of primary school children were also given questionnaires. These questionnaires set out to establish whether the parents were happy for their child or children to see sex organs in their school dictionary, and if illustrated, how they would like them to be illustrated. The two sample groups are very small, but they do give an indication of parents' and teachers' attitudes on this topic. Both the teachers and the parents volunteered to fill in the questionnaires after informal discussions on the topic.

Existing school dictionaries are then examined and compared. The dictionaries included in this study comprise six printed school dictionaries available for use in South African primary schools, as well as two online children's dictionaries. The articles for penis and liver are compared across all of the dictionaries.

The findings of the literature and the questionnaires were then used to inform recommendations for the treatment of human reproductive organs in primary school dictionaries.

3. Literature review

As the aim of this study was to provide recommendations for the treatment of human reproductive organs, and specifically the illustrations in a primary school dictionary for South African learners, the literature on topics that provide context in four areas was explored. The four areas that will be discussed in this section are: illustrations in dictionaries, taboo words in dictionaries, sexuality education in primary schools globally, and sexuality education in the South African context. Together, this literature will help to inform the recommendations given later in the study.

3.1 Illustrations in dictionaries

Illustrations in dictionaries are used "as a shortcut to meaning explanation [and] to group together vocabulary sets" (Atkins and Rundell 2008: 210). They have an important role to play in dictionaries, and specifically in children's dictionaries and school dictionaries. Landau says that "for children's dictionaries in particular, [illustrations] are of prime importance" (Landau 2001: 388).

In a Russian survey done in 2016, where the participants were teachers, parents, and students of philological faculties, 95% of the respondents felt that illustrations in children's dictionaries were "very important" or "important" (Nurlankyzy 2016: 69). "Pictorial illustrations help the dictionary user to comprehend and remember the content of the accompanying verbal equivalent ... , reinforce what is read and symbolically enhance and deepen the meaning of the verbal equivalent" (Nurlankyzy 2016: 71).

Lew notes that the benefits of illustrations, as shown in various studies, are that they "promote vocabulary acquisition" and "help with immediate recognition and comprehension" (Lew 2010: 298). He observes that lexicographers are able to reap the benefits of the extra presentation space afforded by electronic dictionaries to include "pictorial illustrations for a larger number of entries and senses than has been usual in paper dictionaries" (Lew 2010: 299).

According to Gangla, pedagogical dictionaries benefit from the inclusion of encyclopaedic information, such as illustrations (Gangla 2001: 49). "In general, on the basis of this study it can be said that pictorial illustrations add to the communicative value of dictionaries, aid in bridging the semantic gaps that may occur between languages and saves space, which would otherwise be taken up by long descriptions of a lemma" (Gangla 2001: 71).

Nesi says that "pictures are undoubtedly useful for conveying certain kinds of information, and on occasion provide the perfect gloss for an unknown word" (Nesi 1989: 125).

In terms of the most appropriate style for illustrations in school dictionaries, Landau notes that the "school dictionary should avoid the cuteness that may be suitable for children's storybooks but is jarringly discordant in a reference book" (Landau 2001: 389).

According to Nesi, while the attractiveness of an illustration "is a bonus in any book, it is clearly not the first consideration when designing illustrations for dictionaries" (Nesi 1989: 131).

She explains that in "many semantic areas a diagram providing a model of reality is preferable to a faithful representation; in a line drawing of a cross-section of an eye, for example, the component parts are far more easily identifiable than they would be in a photograph" (Nesi 1989: 131).

As can be seen from the above discussion, there are numerous benefits of illustrations in school dictionaries, and if space allows, it is advantageous to illustrate as many senses as possible, with an easily identifiable illustration.

3.2 Taboo words in dictionaries

The reason for the research being conducted in this paper, was the responses to a learner questionnaire where learners expressed concern about illustrations that were "inappropriate" or "underage". This led to the study of the treatment of taboo words in dictionaries.

In this study, the sense of "taboo" is something that is "prohibited or restricted by social custom" (Lexico.com 2022). In this case, the learners were worried about being confronted by images that were not proper for them to see.

In a discussion about the compilation of the Shona-English Biomedical Dictionary (SEBD), the authors wrote that the need for that dictionary was apparent because of the cultural and language gap between English-speaking doctors in Zimbabwe and their Shona-speaking patients. Often, older Shona-speakers use "veiled language" (Mpofu and Mangoya 2005: 118) to discuss their medical complaints. The compilers of the SEBD chose to treat the proper terms but also to include euphemistic terms to accommodate the different users.

"Euphemism is the replacement of a term seen as less refined or too direct by a more refined or less direct term. This is mostly evident when it comes to the naming of the private parts of the body and any biological functions associated with them" (Mpofu and Mangoya 2005: 129). Describing private parts "is considered to be highly obscene in Shona culture so that alternative descriptions for them have been created in an effort to diminish the obscenity which they are deemed to carry" (Mpofu and Mangoya 2005: 129).

An example is the set of translation equivalents for penis, as found in the SEBD:

mboro (penis) mhuka (animal), chirombo (a big thing), mbonausiku (a thing that sees at night), chombo (weapon), chirema (a cripple), sikarudzi (creator of a tribe)

(Mpofu and Mangoya 2005: 130)

As can be seen in the example above, there are many euphemistic terms for penis in the SEBD. None of them even suggest that the speaker using such a euphemism is referring to a part of their body. A medical consultation where one cannot refer to a part of the body by name would be very difficult for both the doctor and the patient.

While the compilers of the SEBD included the euphemistic terms, the correct Shona terms have "the important role of carrying the definitions, [which] would encourage their application in medical practice" (Mpofu and Mangoya 2005: 130).

on the contrary, the compilers of the monolingual general use Shona dictionary, Duramazwi Guru reChiShona (DGC), chose to include the euphemisms "as a way of being courteous to users and of showing respect for societal norms" (Chabata and Mavhu 2005: 260). In their paper describing the compilation of the DGC, the authors describe the conflict between "the theoretical principles on which the lexicographer bases his/her definitions on the one hand and the cultural context in which the lexicographer is working on the other" (Chabata and Mavhu 2005: 255). They knew that in order to adhere to lexicographic theory they should use the correct terminology for human reproductive organs, but in order to be culturally sensitive to the users of this dictionary, they needed to eschew lexicographic theory in the treatment of sex organs. In this dictionary male and female sex organs "were to be defined in terms of their location on a person's body and their use for non- or less sensational functions such as urinating and child bearing" (Chabata and Mavhu 2005: 261).

The compilers noted that "being theoretically sound may lead to a socially unacceptable product whilst being culturally sensitive may result in a poor reference tool" (Chabata and Mavhu 2005: 264).

While these studies show why lexicographers need to be sensitive to the treatment of taboo terms, it also needs to be noted that that "as 'authorities' on what words mean, dictionaries represent themselves as the place to find meaning" (Braun and Kitzinger 2001: 215). In an article comparing the treatment of different human reproductive organs in dictionaries, the authors advised that these terms do need to be treated carefully and consistently. They say that there is "some (limited) evidence that (young) people do consult dictionaries to gain sexual information" (Braun and Kitzinger 2001: 215).

Their study considered each article for different human reproductive organs in terms of "what is it?", "where is it?" and "what is it for?" and found huge inconsistencies in the treatment of male and female sex organs. They remind lexicographers that dictionaries "retain a cultural presence as an authority on what words mean" (Braun and Kitzinger 2001: 228).

3.3 Sexuality education in schools

Juliette Goldman, who has done extensive research into sexuality education in Australia, and the most appropriate timing for it, says that "since puberty and sexuality are inextricably linked in human development, it would seem prudent, efficacious and even morally obligatory to teach boys and girls a comprehensive, integrated programme of sexuality education in every year of their school lives" (Goldman 2011: 155). It is important to note that in lower grades, and therefore most of primary school, sexuality education is more about names of body parts, gender differences, personal safety, and self-esteem. According to Goldman "Many parents hear 'Sexuality Education for Grades 1, 2 and 3' and they think of sexual activity, and they get very anxious" (Goldman 2011: 162) but the recommended curriculum for primary school does not include sexual activity at all. "In that age group we want to normalise sexual knowledge ... as it is useful and fun for this age group" (Goldman 2011: 162) and "we want [children] to feel good, right from the beginning, about their bodies". She says that this is so important before puberty because if they start to "feel negative about their bodies at this age it doesn't bode well for them going through puberty" (Goldman 2011: 162). Duffy, Fotinatos, Smith and Burke point out that "children are reaching puberty at earlier ages than previous generations and therefore, informing students ahead of physical and psychological changes can better prepare them for the associated changes in their lives" (Duffy, Fotinatos, Smith and Burke 2013: 187).

"In light of the fact that children want to know about their bodies, and particularly crucially, that all boys and girls need to be prepared for puberty, the avoidance of sexuality education by classroom teachers and schools is totally inappropriate and severely disadvantages students" (Goldman 2011: 171).

According to Goldman, "teachers in many countries have legal obligations to protect the children in their care from sexual abuse and harm, and education promoting risk awareness, safety and resilience would seem sensible and helpful" (Goldman 2011: 155).

Children and adolescents want, need, and "have the right to access adequate information essential for their health and development" (Goldman 2013: 448).

As to why sexuality education needs to happen at school, Duffy et al. say that "school-based information has been considered a more trustworthy source of learning than friends," (Duffy, Fotinatos, Smith and Burke 2013:189) and therefore the school needs to support these lessons with quality resources.

"Much confusion, anxiety and misinformation regarding puberty, sexuality and reproduction can be overcome by normalising its vocabulary, including clear and simple discussions about basic but accurate anatomical names and processes such as childbirth, implemented by trained and relatively impartial teachers in the early school years" (Goldman 2013: 451). Learning the correct vocabulary for body parts is so important, because "you have a classroom of 20 students, and 20 different families might have 20 different names for these body parts" (Goldman 2011: 161).

These examples show that primary school sexuality education is not about sexual activity, but rather about noticing our bodies, knowing the vocabulary for body parts, and looking after our bodies. It is also about noticing that there are changes that occur in humans as they mature.

3.4 The southern African cultural context

Finally, this study gives the context of the South and southern African cultural environment, and how different cultures in sub-Saharan Africa treat sexuality education. This is not an exhaustive study, merely an introduction to some issues that can be found in the literature.

To begin with, in traditional southern African societies, sexuality education was the responsibility of initiation schools and older relatives. According to Msutwana, "in sub-Saharan Africa, initiation schools were spaces where sexuality education used to happen" (Msutwana 2021: 339) and according to Khau, "Basotho boys learnt about their bodies from elder brothers out in the wild while shepherding livestock" (Khau 2012: 62) and "Basotho girls also learnt about their bodies while out collecting firewood with friends or doing laundry in nearby rivers" (Khau 2012: 63).

Formal sexuality education at schools is a relatively new development that often contradicts traditional teaching. Msutwana says that "in contemporary Xhosa culture, sexuality is viewed as a private and taboo affair" and "it is 'unAfrican' that older people talk about sexuality matters with children" (Msutwana 2021: 341). By "older people", Msutwana means people who are not related to the children, such as teachers.

Another obstacle is that "boys tended to be unwilling to be taught certain aspects of sexuality education by female teachers. Some of these aspects included the male reproductive system" (Msutwana 2021: 349).

Khau confirms the weight of initiation schools and the traditional views that adults should not talk to children about anything sexual, and confirms that "within Lesotho rural communities it is believed that only those who have been to the traditional initiation school have the moral standing and capability to effectively address issues of sexuality with the youth" (Khau 2012: 65). Unfortunately, "research shows that the cultural rules do not always facilitate healthy and safe sexuality" (Msutwana 2021: 339).

Added to the obstacle of challenging traditional views, is the fact that parents are suspicious of the teaching of sexuality education at school. As Khau says, "with parents believing in childhood sexual innocence ... talking to children about ... sex would ... be tantamount to promoting teenage and premarital promiscuity" (Khau 2012: 64). There is often a sense that ignorance is equal to innocence, and whoever teaches children about sexuality is taking their innocence. However, a 2003 study "found that young children know a great deal about sex, gender and HIV/AIDS, which goes against dominant teaching discourses that positioned children as unknowing and innocent" (Bhana 2009: 168).

Another cultural obstacle to teaching sexuality education in schools is that "many teachers in rural schools are un- or underqualified, making it impossible for them to deliver the kind of education that could be transformative of rural contexts and rural people" (Khau 2012: 62). Teachers in rural schools find that "lack of cooperation by parents and learners, shortage of teachers and poor infrastructure as the main stumbling blocks towards quality education" but that parents in these communities do "want an education that is useful to them and their children in making a living and recognizing and appreciating their history and culture" (Khau 2012: 62).

As can be seen in the previous section, sexuality education is vital in schools, and rural communities do acknowledge this. As Khau says, "rural communities would want a sexuality education that recognises and appreciates rural histories and cultures. In order to do this, educators must understand and appreciate the history of sexuality education within rural communities" (Khau 2012: 62). "Unless rural communities have a sense of ownership of the curriculum, unless the curriculum reflects aspects of what people believe in, and unless the sexuality education offered in schools is what is needed by people within rural villages, then school-based sexuality education in rural classrooms will not have the desired effect on youth" (Khau 2012: 67).

Khau also explains that parents are not necessarily against the teaching of sexuality, but they are hesitant about the content of the lessons and what is covered and how it is taught.

Msutwana concurs and says that sexuality lessons do not need to be about sex. They need to cover "the other stuff in sexuality education, such as relationships, sexual orientations, reproduction, gender identities, roles and others" (Msutwana 2021: 341).

Considering the cultural context in which these decisions need to be made, "education is a 'vaccine' against HIV due to relatively lower rates of infection among people with higher levels of educational participation" (Khau 2012: 61).

Bhana submits "that HIV/AIDS prevention has expanded the permissible sphere, including schools, for communicating about sex, gender and sexuality" (Bhana 2009: 165). "The primary school is now becoming an important area for the development of safe-sex messages and the prevention of HIV/AIDS" (Bhana 2009: 166).

As can be seen in this section, sexuality education needs to be taught at school, starting in primary school. Schools need the resources to complement the lessons and primary school dictionaries need to treat the words of human reproductive organs. Learners will benefit from these organs being illustrated in a clear and identifiable way.

4. Teacher questionnaires

Teachers teaching Grades 5 and 6 at two Western Cape primary schools were given questionnaires to fill in and return. As this is a pilot study, these questionnaires were only given to four teachers, who volunteered to complete them, with the goals of gauging their attitudes and preferences for dictionary articles, and testing to establish whether the questionnaires are appropriate for use in a larger study or whether the questions need to change before being used with more teachers. The two schools are both co-ed. One school is a private school and the other is a government school. One questionnaire did not get returned, so these results are based on three questionnaires.

The questionnaires set out to establish what, if any, sexuality education is done at school, and how the teacher feels about the inclusion of human reproductive organs in their school dictionaries. The questionnaire also covered the style of illustrations to accompany the dictionary articles.

The teachers said that puberty and body changes are taught in Life Skills, and that in Grade 7, human reproduction is covered in the Natural Sciences curriculum. One of the teachers mentioned actual sexuality education - in the form of a workshop that is presented by an outside provider, given to the Grade 6 and 7 classes.

The teachers were then asked if sex organs such as breast, genitals, penis, scrotum, testicle, vagina, vulva should be included in a primary school dictionary. One teacher said that all except scrotum, testicles, and vulva should be included, and the others were happy with the inclusion of all of them. This list of words was taken from words found in a variety of school dictionaries.

The teachers mentioned that learners will look up these words and giggle, but "that doesn't mean we must pretend that the words don't exist". A teacher suggested including a note to say that "these are sometimes called private parts because they are private and should not be touched or seen by other people".

The remaining questions considered the illustrations of such words in a primary school dictionary. Question 6 asked if these words should be illustrated. All of the teachers responded in the affirmative, with one of them being "a cautious yes". Her full response was, "This is a tough question. Different cultures and religions hold very different views, and some parents will definitely object. I think I would lean towards saying yes, but it's a very cautious yes."

The follow-up question asked why or why not, and these are the other two responses: "I think in schools we should seek to educate, while keeping it simple and scientific. It might even reduce 'rude' stigma around the topic" and "I feel that if other words are illustrated then all the words need to be illustrated. I would select a very basic drawing".

The next question offered different styles for illustrating private parts and asked what style the teachers preferred.

All three of the teachers chose an anatomical drawing, such as a cross section of the organ in question showing internal and external parts. Two of the teachers also suggested a full (naked) child's body, with everything labelled - arm, leg, penis, etc. One teacher also chose a clear, no-nonsense picture of the organ in question.

It is important to note that learners are getting some form of sexuality education as part of the Life Skills curriculum and the Grade 7 Natural Sciences curriculum. Life Skills covers respect for one's own and others' bodies, positive self-esteem and body image, child abuse, issues of age and gender, HIV and AIDS education, gender stereotyping, sexism and abuse. (Department of Basic Education 2011: 11).

This means that any words for body parts that are introduced or discussed in these lessons should be accessible in a primary school dictionary. The curriculum does not state which body parts should be covered, and it is left up to the textbooks and the teachers how these topics are taught.

The teachers were very helpful with their responses, and it would be a constructive exercise to repeat this questionnaire with a larger sample group of teachers, representing more schools in more provinces of South Africa.

As to how a questionnaire would change for further research, it would be useful to include some information about the school and class sizes. It would also be useful to examine teachers' attitudes about the paraphrases of meanings provided in dictionary articles about human reproductive organs, and whether they should follow the same pattern as other organs, or be treated differently. The challenge with such a questionnaire is to keep it as short as possible to keep the respondents' attention, while covering all the questions that are necessary for the study.

Despite this being a small study, the responses have been very valuable.

5. Parent questionnaires

Questionnaires were also given to parents of primary school children. Again, the sample is a small group of parents who volunteered to fill in the questionnaires, and it is not representative of all parents of primary school children in South Africa. As this is a pilot study, the intention with this questionnaire was to gauge how parents feel about the inclusion of human reproductive organs in their children's school dictionaries, and evaluate whether the questionnaire is appropriate for a larger study.

The questionnaire's introductory paragraph stated that the intention with this study was to establish what sort of illustrations parents would feel comfortable with their child(ren) seeing in their school dictionary. They were also told that this would depend on their personal, cultural, religious, and family background.

Fourteen parents responded to the questionnaires, and as there were no questions asking what schools the children go to, it is unclear how many schools are represented by the responses.

The respondents were parents of Grade 1-6 learners. The home languages spoken by the respondents were either English or Shona. The Shona families are residents of South Africa, attending South African schools. The religions mentioned were Christianity and Muslim. Five respondents indicated that they were not religious.

The parents were asked if they were happy with the inclusion of breast, genitals, penis, scrotum, testicle, vagina, vulva in a primary school dictionary. Here, every respondent said that they were happy with all of the words.

The next question gave some examples of the paraphrases of meaning given for the word penis in school dictionaries.

penis: the male sex organ or genitals (Francolin Illustrated School Dictionary for Southern Africa)

penis: the part of a man's or male animal's body that is used for getting rid of waste liquid and for having sex (Oxford South African School Dictionary 4th edition)

penis: the male sex organ through which sperm is transferred to a female. The penis is also used to dispose of urine. (Kids.Wordsmyth.net)

Parents were asked if they were comfortable with these definitions, followed by whether the parent would like more or less detail in the definitions. Most of the parents were comfortable with them but some gave longer answers, such as:

[The definitions] could be better. The emphasis on their function is unnecessary, since this is a dictionary not an encyclopedia. Just mentioning that it's the pointy bit between a male's legs is probably fine! There's a meaningful difference between defining a word and explaining a concept.

The last seems most relevant but seemingly urinating would be the 'primary' purpose of a penis i.e. everyday usage that every child would know; not the sexual usage so why is the sexual definition most prevalent in this definition? It would make it more relatable.

When asked whether parents would be comfortable with these articles being illustrated in an illustrated school dictionary, all of the respondents said they would be.

The next question asked if parents thought human reproductive organs should get similar dictionary entries to other organs, and all of them said they should. Some parents elaborated:

Yes. I'd like to think it's possible to help children get the difference between the physical organ and its cultural associations, and treating all physical body parts similarly might help make this distinction.

I think in a broad sense as the detail would not necessarily add value for children. While there are many components to most organs, like the heart, the primary definition is for the organ - a hollow muscular organ of the body that expands and contracts to move blood through the arteries and veins. Could genitals not be viewed in the same way? As an overall organ with multiple purposes.

Yes, these organs should be treated comparatively, as 'normally' as possible.

I think similar, so there is less sense of embarrassment or shame around them.

The next question asked parents what style of illustration they would prefer to see in a primary school dictionary. It is interesting to note here, that an overwhelming majority (78%) of the parents preferred a labelled diagram of a body with everything, for example, arm, shoulder, penis, labelled.

The parents were also asked why they chose their preferred option, and a few of them mentioned seeing the body part in the context of the whole body, or seeing it in relation to the rest of the body. One of the responses was, "It's accessible to children, but not coy". One parent spoke of "demystifying" body parts and others spoke of normalising them.

The next question asked whether the parents thought that their cultural/ religious/family background influenced their attitudes about illustrations of human reproductive organs in primary school dictionaries, and here there were six respondents (43%) saying yes, three (21%) saying no, and the rest giving a variety of answers such as "maybe", "yes and no", "partially", "likely".

One of the participants responded to that question with the following: "I think a family history of discomfort around mentioning private body parts or anything to do with sex influences me to believe it is certainly not healthy to continue this silence/embarrassment into the next generation."

The final question in the questionnaire asked if parents had any other comments, and these responses were also very valuable in the context of the rest of the questions.

This is a great opportunity to help clear up misunderstandings of words through using illustrations as an additional descriptor. I think that just as the definitions should describe as clearly as possible the meaning of the words in question, in accessible language for children, the pictures should also be as clear and easy to understand as possible for kids. Hiding pictures of body parts behind coy images or clicks implies that there is something naughty or embarrassing to the body part. I can't see a context in which that kind of messaging would be positive or helpful.

I feel illustrations should be part of the learning tool i.e. avoid photos that may create "hype" between the children. We are a family that do not hide body parts from each other, however, we do try teach respect.

It's good for kids to know their body parts so if they learn from school it's right.

I think children should be well informed about these entries so they know what it is and what it is used for. It will also help kids to speak out if they are sexually abused because they know these things and they will not be shy.

Children that are doing lower grades must not be exposed to too much information about sex organs, only when they get older that's when they have a better understanding.

Never thought of this but to me it's simply anatomy and the earlier they learn about the body parts the better.

I would add level of education as an influencer in my comfort, in addition to cultural/religious/family background.

These responses are interesting. They are suggesting that the parents have not given this issue much thought, but they are thinking about it now, and they do not want to make mistakes from previous generations. The parent who suggests that the penis be defined as "the pointy bit between a male's legs" is not ready to write paraphrases of meaning for dictionaries! It is also interesting that one of the comments above says that children in lower grades do not need to be exposed to too much information, followed by a quote saying that the earlier they learn this, the better.

The responses suggest that parents are open to, and would prefer, to see human reproductive organs treated in primary school dictionaries and that these body parts need to be treated clearly, while normalising the vocabulary about them, but that the non-sexual functions should be emphasised.

There is definitely room for further research into this: more parents from a wider range of schools, and in different provinces in South Africa. As can been seen in the literature section, there is a wide variety of cultural and religious attitudes regarding the teaching of human reproductive organs in primary schools.

This questionnaire could be improved by adding a section about the make-up of the family, and whether the children are boys or girls, and whether the respondent is male or female. Parents may find it easier to talk to boys or girls about puberty and related vocabulary. It could also be improved by having multiple-choice answers in some places. There should also be more of a separation between considering the different paraphrases of meaning and the illustrations.

The responses to this questionnaire have been valuable and will inform some decisions that will be made in future dictionaries for primary school learners.

6. Analysis and comparison of school dictionaries

This section will examine and compare school dictionary articles for human reproductive organs. Firstly, a set of South African school dictionaries will be discussed, followed by two articles from online school dictionaries. The word penis will be used as the lemma used to compare across the dictionaries. This lemma was chosen simply because it is one of the human reproductive organs. The penis articles will be compared with the articles in the dictionaries for liver, as this is another organ in the body. The dictionary comparison will also include which of the following words are contained in the school dictionaries: breast, genitals, testicle(s), vagina.

The following dictionaries are available for use in South African primary schools: The Collins New School Dictionary (Collins), the Oxford South African School Dictionary 4th edition (OSASD4e), the Longman South African School Dictionary (Longman), the Francolin Illustrated School Dictionary for Southern Africa (Francolin), the Oxford South African Illustrated School Dictionary (OSAISD), and the Pharos English Dictionary for South African Schools (Pharos). All of these dictionaries, with the exception of Collins, were adapted or published for the South African primary school market. The dictionaries are available to purchase in South African bookshops, with the exception of the Francolin, which is no longer in print. It was included because it is a school dictionary specifically produced for primary schools in southern Africa, and is thus comparable to the other dictionaries used in this section.

The Oxford South African School Dictionary 4th edition (OSASD4e) was published in 2019 and is aimed at Grades 4 to 12. It contains a few illustrations, but not many at all.

The Longman South African School Dictionary (Longman) was published in 2007 in the United Kingdom with the South African edition edited by South African editors and consultants. There is no indication in the dictionary as to which grades or ages the target users are. The Longman contains a few illustrations.

The Francolin Illustrated School Dictionary for Southern Africa (Francolin) was developed by the Dictionary unit for South African English and published in 1997 in Cape Town. The Francolin was specifically "aimed at senior primary school pupils who do not speak English as their first language, but who have English as a subject or as the language of learning" (Dictionary unit for South African English 1999). The dictionary contains more illustrations than the previous two dictionaries; at least two to three illustrations per double page spread.

The Oxford South African Illustrated School Dictionary (OSAISD) was published in 2008 and is aimed at learners from Grade 3 to 7. It contains a few illustrations.

The Pharos English Dictionary for South African Schools (Pharos) was published in 2014. There is no indication of age or grade range in the dictionary. It contains a few illustrations.

The following are reproductions of the articles for penis in the above dictionaries. The use of bold and italics, brackets, as well as line breaks have been reproduced, but not the different fonts.

Collins:

penis penises

NouN A man's penis is the part of his body that he uses when urinating and having sexual intercourse OSASD4e:

penis (say pee-niss) noun (plural penises)

the part of a man's or a male animal's body that is used for getting rid of waste liquid and for having sex

Longman:

penis /peen-iss/ noun the part of a boy's body that he uses to urinate

Francolin:

penis [say pee-niss] noun (two penises) the male sex organ or genitals

OSAISD:

n/a

Pharos:

penis noun the male sexual organ in humans and many animals: Males have penises and females have vaginas.

Of the six dictionaries consulted, one does not treat penis at all. The OSAISD may have excluded the lemma due to the lower target age group, or due to the shorter word list.

Of the other dictionaries, only one, Pharos, provides an example sentence. The others only provide a paraphrase of meaning. All of the paraphrases of meaning mention the functions of the penis, and one only refers to urination, two only refer to sex, and two refer to both sex and urination. Only Francolin and Pharos refer to the penis as an organ, compared to all the dictionaries referring to the liver as an organ, as can be seen below.

Collins:

liver livers

NOuN 1 Your liver is a large organ in your body which cleans your blood and helps digestion from Greek liparos meaning 'fat'

OSASD4e:

liver (say liv-uh) noun

1. (plural livers) the organ inside your body that cleans the blood -> see illustration at organ

Longman:

liver /liv-uh/ noun 1 the large organ inside your body that cleans your blood

Francolin:

liver noun

1 a large organ in your body which helps to clean your blood

OSAISD:

liver (say liv-er) noun (plural livers)

a large organ in the body that keeps the blood clean and helps to digest the food we eat.

Pharos:

liver noun 1 a large organ in the body that cleans the blood: Drinking too much alcohol can damage your liver.

Comparing penis to liver, one can see that all the dictionaries contain the article for liver, and all of them refer to the liver as a large organ in the/ your body. All of the liver articles refer to the function of the liver. (The articles that mark the sense number also include the sense of the liver being a type of food.) The OSASD4e contains a cross reference to an illustration at organ. This illustration is a line drawing of a person's torso, with the following organs labelled: brain, lung, heart, liver, stomach, kidney, intestines.

The two online dictionaries compared in this study are the Wordsmyth Children's Dictionary and Kids Britannica. The online Wordsmyth Children's Dictionary does not have a printed counterpart. It can be accessed at kids.wordsmyth.net.

The Wordsmyth Children's Dictionary is aimed at learners from Grade 5 to Grade 8.

According to the Kids Britannica About us page, Kids Britannica's "safe and age-appropriate content keeps [kids] focused on what you want them seeing online while enabling them to succeed in school and life" (Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc, 2022). It does not give a target age range.

Wordsmyth:

penis noun penes, penises

the male sex organ through which sperm is transferred to a female. The penis is also used to dispose of urine.

Kids Britannica

penis noun

a male organ of copulation containing a channel through which sperm is discharged from the body that in mammals including humans also serves to discharge urine from the body

What is notable about both of these paraphrases of meaning is that they are complicated compared to the printed school dictionaries shown above. The Kids Britannica uses the term "copulation" which is very unlikely to be understood by primary school children. It also contains the complicated sentence structure, "... through which sperm is discharged" which is also very advanced language for primary school learners, especially those learning in their second language. However, both dictionaries refer to the penis as an organ. Again, both paraphrases of meaning refer to the function of the penis, and in both of these dictionaries, both the functions of sex and urination are mentioned.

Wordsmyth:

liver noun

a large, reddish brown organ in the body that has many functions. The liver cleans the blood, stores energy and nutrients, makes bile, and helps the body digest fats. It is found at the top of the abdomen. Drinking too much alcohol can damage the liver.

Kids Britannica

liver noun

a large glandular organ of vertebrates that secretes bile and causes changes in the blood (as by changing sugars into glycogen and by forming urea)

As can be seen by the paraphrases of meaning for liver, both dictionaries refer to the liver as an organ and define it by its functions. The Wordsmyth article also refers to the position in the body of the liver, as well as its size and colour: a first for any of these dictionary articles. Both the online articles give more detail than the printed school dictionaries. Again, the Kids Britannica paraphrase of meaning is too complicated for primary school learners.

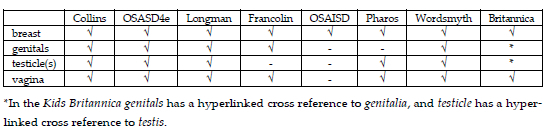

When comparing the dictionaries in terms of the words listed at the beginning of this section, the table below shows which terms are in which dictionaries.

As can be seen by this table, the Collins, OSASD4e, Longman, and Wordsmyth all contain all of the articles, while the other dictionaries do not treat all of them. OSAISD is notable in that it only has breast. The two online dictionaries only have illustrations of birds in the article for breast, to illustrate the part of the bird that is referred to as a breast - for example in an orange-breasted sunbird.

As can be seen by these comparisons, penis and liver are treated differently within the dictionaries. A more detailed study of more human reproductive organs needs to be done to establish whether there is consistency in each dictionary across the lexical set of sex organs.

7. Discussion and conclusion

As can be seen by the previous sections in this paper, this is a substantial topic that this article is unable to do justice to.

Some clear recommendations, however, can be taken from this research. Firstly, from the literature it is evident that it is necessary to teach primary school learners about their bodies and puberty. This is important despite it being a possibly uncomfortable topic for some teachers and despite possible resistance from some parents. A dictionary enters the picture because the vocabulary for body parts that is used in these lessons needs to be accessible in the school dictionaries, along with clear illustrations. A good guideline for the treatment of human reproductive organs, or indeed any organ, is to answer the questions: what is it? Where is it? What is it for?

The teachers involved in this study were unanimous in the opinion that dictionaries should include words for human reproductive organs, but they did not agree on which words should be included in a primary school dictionary.

Teachers expressed the feeling that including these words in dictionaries would help to normalise the vocabulary used - an opinion that was also expressed in the literature review.

The responses of the parents of the primary school children who filled in the questionnaire were also very insightful. They wanted their children to have access to human reproductive organs in their dictionaries, and again, they wanted to normalise the vocabulary used in sexuality education. The parents gave suggestions as to what style of illustration would be most appropriate in a primary school dictionary, and also gave their opinions on the information to be contained in the paraphrases of meaning. These are people who do not have any lexicographic experience, and so their input was based on their thoughts and experiences as parents.

It was very useful including teachers and parents in the study as they offered different perspectives.

The analysis of the words in the school dictionaries could be a whole study on its own. To get a sense of consistency within each dictionary, one would need to compare all articles for human reproductive organs, as well as other organs in the human body. However, the small sample of dictionary articles here does give one a sense of how the different school dictionaries treat sex organs.

In terms of recommendations for primary school dictionaries, this research shows that the following words should be included: breast, genitals, penis, testicle, vagina as these are the words that would come up in primary school sex education lessons. It should be noted that sexuality education is the umbrella term for lessons that include knowing about one's body, puberty, and related topics, not necessarily to do with sexual activity. Each term should be illustrated; in the case of penis and testicles, they should be included and labelled on a picture of a boy, along with other visible body parts. Genitals should also be included in this diagram. The diagram of a girl would include vagina and genitals, and breast would need to be labelled on a picture of a woman. Each of the dictionary articles would be accompanied by the relevant diagram instead of the diagram being cross-referenced at the articles.

There could also be a note at each of these articles telling learners:

These are your private parts and nobody should ask to look at or touch them. If somebody makes you feel uncomfortable, speak to an adult you trust or call Childline on 116 from any cellphone.

Regarding recommendations for further study, all of the topics covered in the literature review can be studied in more depth. The teacher and parent questionnaires need to be given to a much larger sample of both groups. The appropriate permission would need to be sought and the participants would need to be selected from a variety of schools and backgrounds. The dictionaries can be analysed in more detail and across more parameters, as discussed above.

However, this is an important topic and further research in all of these areas will be very worthwhile and valuable. The three learners who expressed concern would be pleased to know that their concerns have been taken seriously.

Bibliography

Dictionaries

Bullon, S. et al. (Eds.). 2007. Longman South African School Dictionary. Harlow, Essex: Pearson Education [ Links ]

Cullen, K. et al. (Eds.). 2002. Collins New School Dictionary. Second edition. Glasgow: HarperCollins. [ Links ]

De Kock, C. et al. (Eds.). 2014. Pharos English Dictionary for South African Schools. Cape Town: Pharos Dictionaries. [ Links ]

Dictionary Unit for South African English. 1999. Illustrated School Dictionary for Southern Africa. Cape Town: Francolin. [ Links ]

Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. 2022. Britannica Kids Dictionary. [Online] Available at: https://kids.britannica.com/kids/browse/dictionary (22 February 2022).

Hiles, L. et al. (Eds.). 2008. Oxford South African Illustrated School Dictionary. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Oxford University Press. 2022. Lexico.com. [Online] Available at: https://www.lexico.com/ (22 February 2022).

Reynolds, M. et al. (Eds.). 2019. Oxford South African School Dictionary. Fourth edition. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Wordsmyth. 2022. Word Explorer Children's Dictionary. [Online] Available at: https://kids.wordsmyth.net/we/ (22 February 2022).

Other sources

Atkins, B.T.S. and M. Rundell. 2008. The Oxford Guide to Practical Lexicography. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Bhana, D. 2009. 'They've Got All the Knowledge': HIV Education, Gender and Sexuality in South African Primary Schools. British Journal of Sociology of Education 30(2): 165-177. [ Links ]

Braun, V. and C. Kitzinger. 2001. Telling it Straight? Dictionary Definitions of Women's Genitals. Journal of Sociolinguistics 5: 214-232. [ Links ]

Chabata, E. and W.M. Mavhu. 2005. To Call or Not to Call a Spade a Spade: The Dilemma of Treating 'Offensive' Terms in Duramazwi Guru reChiShona. Lexikos 15: 253-264. [ Links ]

Department of Basic Education. 2011. National Curriculum Statement (NCS): Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement, Intermediate Phase Grades 4-6. Pretoria: Government Printing Works. [ Links ]

Duffy, B., N. Fotinatos, A. Smith and J. Burke. 2013. Puberty, Health and Sexual Education in Australian Regional Primary Schools: Year 5 and 6 Teacher Perceptions. Sex Education 13(2): 186-203. [ Links ]

Gangla, L.A. 2001. Pictorial Illustrations in Dictionaries. Unpublished M.A. dissertation. Pretoria: University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

Goldman, J.D.G. 2011. External Providers' Sexuality Education Teaching and Pedagogies for Primary School Students in Grade 1 to Grade 7. Sex Education 11(2): 155-174. [ Links ]

Goldman, J.D.G. 2013. International Guidelines on Sexuality Education and their Relevance to a Contemporary Curriculum for Children Aged 5-8 years. Educational Review 65(4): 447-466. [ Links ]

Khau, M. 2012. "Our Culture Does not Allow that": Exploring the Challenges of Sexuality Education in Rural Communities. Perspectives in Education 30(1): 61-69. [ Links ]

Landau, S.I. 2001. Dictionaries: The Art and Craft of Lexicography. 2nd edition. New York/Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Lew, R. 2010. Multimodal Lexicography: The Representation of Meaning in Electronic Dictionaries. Lexikos 20: 290-306. [ Links ]

Mpofu, N. and E. Mangoya. 2005. The Compilation of the Shona-English Biomedical Dictionary: Problems and Challenges. Lexikos 15: 117-131. [ Links ]

Msutwana, N.V. 2021. Meaningful Teaching of Sexuality Education Framed by Culture: Xhosa Secondary School Teachers' Views. Perspectives in Education 39(2): 339-355. [ Links ]

Nesi, H. 1989. How Many Words is a Picture Worth? A Review of Illustrations in Dictionaries. Tickoo, M.L. (Ed.). 1989: 124-134.

Nurlankyzy, N.B. 2016. The Role of Illustrations in Modern Dictionaries. Вестник 7(19): 69-71. [ Links ]

Tickoo, M.L. (Ed.). 1989. Learners' Dictionaries: State of the Art. Anthology Series 23. Singapore SEAMEO Regional Language Centre.