Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Lexikos

On-line version ISSN 2224-0039

Print version ISSN 1684-4904

Lexikos vol.32 spe 2 Stellenbosch 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.5788/32-3-1729

ARTIKELS/ARTICLES

The South African National Lexicography Units - Two Decades Later

Die Suid-Afrikaanse nasionale leksikografiese eenhede - twee dekades later

Mariëtta Alberts

Former Director: Terminology Development and Standardisation, Pan-South African Language Board (PanSALB) (albertsmarietta@gmail.com)

ABSTRACT

The lexicography practice in South Africa has distinctive features and to a great extent relates to the political dispensation current at a given period. During the previous political dispensation only two dictionary units existed in South Africa that were state funded, namely the Bureau of the Woordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal (WAT) and the Dictionary for South African English (DSAE). These dictionary units, therefore have a long dictionary history. Some of the African languages, such as Xhosa, Zulu, Tswana and Northern Sotho also had dictionary units at the time but they were situated at and funded by tertiary institutions. The current national government requires dictionaries in all official languages for proper communication in languages the citizens understand best, i.e. their respective mother tongues. The Pan-South African Language Board (PanSALB), established in 1996, was a direct consequence of the country's new multilingual dispensation. This dispensation required equal rights for all the official languages and the legislation governing PanSALB was therefore amended to allow for equal justice to all dictionary projects for the official South African languages. This led to the establishment of national lexicography units for each of the official South African languages. A strategic planning process conducted at the Bureau of the Woordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal not only influenced the lexicography practice at the Bureau, but also had a huge impact on the newly established national lexicography units (NLUs). Both the articles published in Lexikos, that originated in 1991, and the activities of the African Association for Lexicography (AFRILEX), established in 1995, have a huge influence on the activities of the NLUs. Although the NLUs are already 21 years old and should officially be of age, the question remains whether they really gained their independence. This article focusses on the heritage of the Bureau of the WAT as National Lexicography Unit for Afrikaans and the example that it has set to the other NLUs.

Keywords: academic journal, association, communication, dictionary, feasibility study, human language technologies, language for special purposes, legislation, lexicography, management, national lexicography units, strategic planning, terminography, terminology

OPSOMMING

Die leksikografiepraktyk in Suid-Afrika beskik oor kenmerkende eien-skappe wat grootliks verband hou met die politieke bedeling van 'n bepaalde tyd. Gedurende die vorige politieke bestel het slegs twee woordeboekkantore bestaan wat deur die staat gefinansier is, naamlik die Buro van die Woordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal (WAT) en die Dictionary for South African English (DSAE). Hierdie woordeboekkantore het dus 'n lang woordeboekgeskiedenis. Sommige van die Afrikatale, byvoorbeeld Xhosa, Zulu, Tswana en Noord-Sotho, het ook gedurende daardie tyd woordeboekkantore gehad, maar hulle was by tersiêre instansies gesetel en is ook deur hulle gefinansier. Die huidige regering vereis woordeboeke in al die amptelike tale om behoorlike kommunikasie te bewerkstellig in die tale wat die beste deur die burgers verstaan word, naamlik hul onderskeie moedertale. Die Pan-Suid-Afrikaanse Taalraad (PanSAT), wat in 1996 tot stand gekom het, was die direkte uitvloeisel van die land se nuwe meertalige beleid. Ten einde gelyke beregtiging vir alle woordeboekprojekte in al die amptelike Suid-Afrikaanse tale teweeg te bring, is die PanSAT-wetgewing gewysig. Dit het tot gevolg gehad dat nasionale leksikografiese eenhede vir elk van die amptelike Suid-Afrikaanse tale gestig is. 'n Strategiese beplanningsproses wat by die Buro van die Woordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal gedoen is, het nie net 'n invloed gehad op die leksikografiepraktyk by die Buro nie, maar dit het ook 'n groot impak gehad op die nuut gestigte nasionale leksikografiese eenhede (NLE's). Sowel Lexikos, wat in 1991 tot stand gekom het en die artikels wat daarin gepubliseer word, asook die bedrywighede van die African Association for Lexicography (AFRILEX), wat in 1995 gestig is, het 'n groot invloed op die werksaamhede van die NLE's. Hoewel die NLE's een-en-twintig jaar gelede gestig is en dus amptelik mondig behoort te wees, ontstaan die vraag of hulle werklik hul onafhanklikheid verkry het. Hierdie artikel fokus op die erflating van die Buro van die WAT as Nasionale Leksikografiese Eenheid vir Afrikaans en sy voorbeeld vir die ander NLE's.

Sleutelwoorde: vaktydskrif, vakvereniging, kommunikasie, woordeboek, lewensvatbaarheidstudie, mensliketaaltegnologie, vaktaal, wetgewing, leksikografie, bestuur, nasionale leksikografiese eenhede, strategiese beplanning, terminografie, terminologie

Language is one of the most vital factors of self-realization for a people. Lexicography is a major linguistic cornerstone, and should not be neglected. (James Duplessis Emejulu 2003: 195)

1. Introduction

The year 1991 was a Rubicon year for South African lexicography and several irrevocable decisions were made during the year that had an influence on the future of the South African lexicography practice. During 1991 the Bureau of the Woordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal (WAT) (Dictionary of the Afrikaans Language) decided to restructure (Bureau of the WAT 1989; Bureau of the WAT 1991). One of the results of the restructuring process was the first publication of a professional journal Lexikos in the AFRILEX Series from 1991. At the time the Bureau of the WAT also initiated the idea for the establishment of an Institute for Southern African Lexicography. The external feasibility study of 1992-1993 conducted by an independent researcher indicated that stakeholders did not want another bureaucratic institution and rather suggested the establishment of a clearing house or association to realize the need for collaboration, cooperation, coordination and communication in the field of lexicography (Alberts 1993). Further research on this subject by another independent team indicated the explicit need for an association and in 1995 the African Association for Lexicography (AFRILEX) was established. Coincidentally, in 1995 the Department of Arts, Culture, Science and Technology (DACST), as custodian of the two government-funded dictionary units at the time decided to repeal the WAT Act and to draft legislation to establish 11 national lexicography units - one for each of the official languages. After in-depth discussions it was, however, decided to incorporate the functions of the NLU Bill (DACST 1996) as articles into the appended PanSALB Act of 1999. Consequently, the 11 National Lexicography Units (NLUs) were established and they receive government funding via PanSALB (established in 1996). The editors-in-chief, boards of directors and staff of the NLUs received training in various aspects concerning dictionary making - from existing dictionary units as well as from members of AFRILEX (cf. Alberts 2011: 23-52). Currently the NLUs are members of AFRILEX and they all participate in the Association's activities.

In this article the focus is placed on the development and progress of the National Lexicography Units since their establishment in 2000. The enormous contribution of the Bureau of the WAT towards the South African lexicography practice receives major attention. Dr Dirk van Schalkwyk, as member of the PanSALB Board and editor-in-chief of the Bureau of the WAT, played a decisive role in the establishment of lexicography units for all the other languages in the country. Soon the Bureau also assisted in facilitating strategic planning and training sessions at other dictionary projects in Africa and abroad. The aim of this contribution is therefore to recognize the extraordinary contribution of the Bureau of the WAT in South African, African and international lexicography. Under the leadership of the previous and current editors-in-chief, Drs Dirk van Schalkwyk and Willem Botha respectively, the Bureau of the WAT was transformed into an example of efficient planning and management strategies and the WAT was developed into a modern dictionary compiled according to relevant metalexicographical principles. Having achieved this, the Bureau shifted its focus to national and international lexicography. Lexicography training courses were initiated at the Bureau which have been attended by lexicographers and lexicography students from inter alia South Africa, Namibia, Angola, Gabon, Tanzania, Zambia and the Netherlands. The establishment of the international lexicographic journal Lexikos was one of the most important consequences of the Bureau's transformation.

2. The Bureau of the Woordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal (WAT)

The Bureau of the Woordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal (WAT), established in 1926 by Prof. J.J. Smit, is one of the oldest dictionary units in South Africa and celebrated its 95th year of existence in 2021. Fortunately, the lexicographic experiences gained over nine decades by this office could be shared with related offices in South Africa, Africa and abroad. Lexicographers and scholars in lexicography could learn from the successes, problems experienced and the mistakes made by this dictionary institution. One such problem relates to the slow progress made by the Bureau - the letter K, for instance, took 30 years to complete (cf. Botha 2003a; 2003b: 49). The editors of the dictionary realized that such slow progress could mean that the dictionary would not be completed in the foreseeable future. In May 1989 the Board of Control of the WAT made drastic suggestions of which the most important were the need for a strategic planning at the Bureau and the computerisation of the lexicographic activities at the Bureau (cf. Bureau of the WAT 1989; Botha 2003b: 49).

In 1989 Mr D.C. Hauptfleisch, the then editor-in-chief of the Bureau of the WAT, requested Dr D.J. van Schalkwyk, at the time senior co-editor at the Bureau, to facilitate a process of strategic planning in order to speed-up the lexicographical process. Dr Van Schalkwyk had an in-depth knowledge of modern planning strategies due to his experience in planning during his previous career as vice-principal of the University of Namibia (Gouws 2003: 77). In the light of cooperative lexicography, it was also necessary to ensure the optimal participation of linguists in the compilation of the comprehensive Afrikaans dictionary to ensure the user-friendliness of the end-product (cf. Botha 2003b: 49). Previously there seemed to be a huge gap in participation between editors and linguists (De Vries 1989).

The aim of the strategic planning at the Bureau was mainly to accelerate the work relating to the compilation of the dictionary (Van Schalkwyk 1998: 141). During the strategic planning process a mission was formulated, strategic performance areas were determined, a historical review was compiled, a situational description was made regarding the internal and external environment (i.e. the strong and weak points of the internal environment were determined, and relevant threats and opportunities in the external environment were identified), scenarios were investigated regarding the future and what these developments could mean for the Bureau and the dictionary compilation process. The information gathered during the strategic planning process was used to formulate long-, medium- and short-term objectives (cf. Bureau of the WAT 1989; Botha 2003b: 50).

By the end of November 1989, the strategic planning process was completed and the plan of action developed during the time was implemented in order to streamline all the activities associated with the lexicographic process. The action plans for the various performance areas incorporated aspects such as data collection and the editorial manipulation thereof, marketing, language services, research, personnel issues, support services, finances, management and planning, and layout, print, binding and publishing issues (cf. Botha 2003b: 50).

The Institute for Research into Language and Arts (IRLA) at the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) assisted with the initial computerisation process at the Bureau and the Lexi program was introduced at the Bureau of the WAT (Alberts and Nieuwoudt 1992).

Specific production norms, with an integrated performance management system, were developed to continuously measure and monitor the performance of the various sections within the Bureau. This ensured the full participation of each member of staff as well as a united effort to meet the set requirements, objectives and goals on fixed target dates (cf. Van Schalkwyk 1998: 145-146).

The Bureau of the Woordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal (WAT) started publishing an academic journal Lexikos since 1991 as one of the consequences of the strategic planning exercise. One of the most important aims with the publication of Lexikos in the AFRILEX series has always been to create a communication channel for national and international discussions on lexicographical issues, and in particular to serve lexicography in Africa, with its rich linguistic diversity (https://www.wat.co.za).

As a result of an external study, conducted in 1992/1993 by the author, on behalf of the Bureau of the WAT on the feasibility of an Institute for Southern African Lexicography (Alberts 1993) and related follow-up research by her and Prof. Danie Prinsloo, of the Department of African Languages, University of Pretoria, the African Association for Lexicography (AFRILEX) was established in 1995. Lexicographic communication in Africa and abroad gained momentum with the establishment of AFRILEX and when Lexikos also officially became its mouthpiece. Officially Lexikos 6 in the AFRILEX Series was the first volume in the joint venture between Lexikos and AFRILEX.

Dr Dirk van Schalkwyk, editor-in-chief of the Bureau of the WAT, created a precedent in the South African lexicography practice by creating acceleration measures through a proper strategic planning process which later also impacted on the to be established national lexicography units. The modern character of the WAT publications since the implementation of the various strategies mentioned earlier resulted in a user-friendly dictionary, with timeous input from linguists, lexicographers, specialists and laypeople alike. The publications of the Bureau of the WAT reflect the content of a standardised Afrikaans language, but they also portray other varieties of Afrikaans such as Namakwa-lands and Kaaps and therefore serve the entire Afrikaans community. The publications, both hard copies and online versions, are relevant for average dictionary use and are useful tools for the teaching of Afrikaans at primary, secondary and tertiary levels of education.

For the past two decades the Bureau of the WAT functions as the national lexicography unit for Afrikaans. It not only receives a monthly grant from the state via PanSALB but it also generates its own funds to ensure the sustainability of the unit. Although the compilation of the comprehensive monolingual dictionary is its main concern, various satellite dictionary products were already generated from the existing database and corpus, such as Woordkeusegids: 'n Kerntesourus van Afrikaans (a thesaurus for Afrikaans containing core vocabulary), Afrikaanse idiome en ander vaste uitdrukkings (Afrikaans idioms and other fixed expressions), the Etimologiewoordeboek van Afrikaans (EWA) (etymological dictionary of Afrikaans), and the Elektroniese WAT (electronic WAT) (cf. https://www.woordeboek.co.za), available as CD-ROM version or on the internet. The WAT is also available online on the VivA platform (Virtuele Instituut vir Afrikaans [Virtual Institute for Afrikaans], cf. http://viva-afrikaans.org; Alberts 2019: 39, 41-42). The book, Basic Afrikaans. The Top 1 000 Words and Phrases (2011, 2019), compiled by the WAT and the Vriende van Afrikaans, an affiliation of the Afrikaanse Taal- en Kultuurvereniging (ATKV), in collaboration with and published by Pharos Publishing House, assists with the process of learning the Afrikaans language.

Through funds-generating initiatives under the proficient leadership of the current editor-in-chief, Dr Willem Botha, activities relating to the lexicography process such as Borg 'n Woord (Sponsor a Word) /Koop 'n Woord (Buy a Word), Woordpret (Fun with Words), and the Nuutskeppingskompetisie (competition for the creation of neologisms) in collaboration with the radio station Radio Sonder Grense (RSG) and the Afrikaanse Taal- en Kultuurvereniging (ATKV), as well as the Handelsnaamkompetisie (competition for trade or brand names in Afrikaans), ensure general visibility and user participation. Although the Bureau actively seeks public awareness and participation it maintains a strict social media policy.

The Bureau of the WAT recognizes and serves the international lexicography practice through its liaison with related offices in Africa, Europe and the United States of America. As part of its international lexicographic participation, the Bureau annually honours the birth of the father of dictionaries in America, Merriam Webster, on 16 October 1758.

3. PanSALB and the national lexicography units

3.1 Background

The language policy of a country determines the status accorded to different indigenous languages and a direct relationship exists between language planning, language policy, language practice (i.e. lexicography, terminography, translation and interpreting) and language development and management (Alberts 2017: 155). Section 6(2) of the constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996, recognizes the historically diminished use and status of the indigenous languages of South Africa and compels the state to take practical measures to design mechanisms to elevate the status and advance the use of these languages (DSRAc 2005: 3). The constitution further requires all official languages to enjoy parity of esteem and that they be treated equitably. The South African language policy accommodates linguistic diversity (Alberts 2017: 150) which accommodates the various mother tongues used in South Africa to ensure that all citizens have access to information in the languages they understand best. The Language Planning Task Group (LANGTAG) was appointed in 1995 as a language-planning exercise to investigate the language dispensation in South Africa (DACST 1995). The National Language Policy Framework of March 2003 gives effect to the constitutional rights regarding language usage and development (DAC 2002). All these actions compel the state to take practical steps to design mechanisms to elevate the status and advance the use of the South African official languages, and to ensure that government communicates with its citizens in their respective mother tongues/first languages. The development of comprehensive dictionaries in all official South African languages is a step towards these languages enjoying parity of esteem and equitable treatment. It also provides for the national government to regulate and monitor the use of official languages by legislative and other means (DAC 2011: 7; Government Gazette 2012: 2, 4; Alberts 2017: 159).

In view of the constitutional provisions for multilingualism and the development of all the official languages, it was necessary to make equitable provision for the operating of national dictionaries for these languages. Such a dispensation required legislation along the lines of the Woordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal Act 1973 (Act No. 50 of 1973, with its Amendment Acts, No. 9 of 1986 and No. 22 of 1991).

3.2 The establishment of the Pan-South African Language Board

An issue relating to the lexicography environment in South Africa concerns the establishment of the Pan-South African Language Board (PanSALB) in 1996. PanSALB was established to give effect to the letter and spirit of section 6 of the Constitution. It is a constitutional body instituted in terms of the PanSALB Act 59 of 1995 (as amended in 1999) and it functions as an independent statutory body. Its primary objectives are to promote multilingualism and to develop the previously marginalized official South African languages, including South African Sign Language (SASL), and the Khoe and San languages. PanSALB's mandate is therefore to concentrate on the promotion of equity between the South African languages and to maximize the multilingual communicative capacity of citizens in terms of the Constitution's democratic principles.

Another objective is to minimize language barriers and this involves all the languages used in South Africa (Ferreira 2002: 204).

PanSALB created advisory structures to assist it in achieving its mandate, namely to promote multilingualism, develop languages and protect language rights. These structures comprise:

- Nine provincial language committees (PLCs) - to advise PanSALB on language-related activities in the provinces, i.e. language policy formulation and implementation, and to promote and develop the different languages within the provincial boundaries;

- Fourteen national language bodies (NLBs) (one for each of the official languages; one for the heritage languages [which was, however, never established], one for Khoe and San and one for South African Sign Language [SASL]) - to advise PanSALB on aspects of spelling and orthography, language and terminology development, dictionary needs (general and technical/special purpose), literature and media, research and education;

- Eleven national lexicography units - to compile comprehensive monolingual and other types of dictionaries (i.e. bilingual translation, etymological, learners' and technical for each of the official languages) (Alberts 2003: 133; 2011: 23-52; 2017: 158).

3.3 Establishment of NLUs

The NLUs were established at a time when it was critically important to promote the formulation of a policy to meet the general need for a properly funded and managed lexicographical practice for the national monolingual general dictionary projects of South Africa. By establishing and funding national monolingual dictionaries, the Department of Arts, Culture, Science and Technology (DACST) could develop an umbrella lexicography policy for all official languages (Alberts 1996; 1997).

At the time the major existing dictionary projects in South Africa had different time schedules, venues and aims and it was difficult to align the projects and lexicographical activities. In order to create a better alignment of the government-funded part of the national dictionary projects, national lexicography (dictionary) units had to be established for all official languages. Such national lexicography units would both within themselves and in the broader national perspective comply with the national goals set out in the national language policy regarding multilingualism (cf. DACST 1996: 16).

In 1995 the Department of Arts, Culture, Science and Technology (DACST), that funded the dictionary projects of the Woordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal (WAT) and the Dictionary for South African English (DSAE), decided to draft legislation to establish national lexicography units for all the official languages. The Department (DACST) recommended that the existing Woordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal Act (Act 50 of 1973, with its Amendment Acts, 9 of 1986 and 22 of 1991) be repealed and replaced by a new Act (cf. the National Lexicography Units Bill, DACST 1996) to govern national lexicography units for the official languages. It was drafted as umbrella legislation to incorporate the existing WAT and DSAE dictionary units as well as the planned national lexicography units for the official African languages (cf. Alberts 1996). The aim of the Bill was "to provide for the establishment and management of national lexicography units; to make equitable provision for national general dictionaries for each of the official languages of South Africa and for matters incidental thereto" (DACST 1996: 2; 1997).

The linguistic heritage of the country could be preserved and further developed with these units since general lexicography describes the vocabulary of a given language by documenting it. The Bill was supposed to bring about change and transformation since it made provision for the documentation and development of all these languages (cf. Alberts 1996; 2011: 23-52). DACST aimed to preserve South Africa's linguistic diversity in all its forms, regardless of political, demographic or linguistic status (DACST 1995: 16). DACST also planned to finance these dictionary units as it was already doing with regard to Afrikaans and English and the national terminology office. The national lexicography units would receive recurrent financing from the state and they were planned to function directly under the auspices of DACST.

The drafting of the Bill was done in close cooperation with the Pan-South African Language Board. In the light of PanSALB's strong, constitutionally mandated role in language promotion and development, it was deemed appropriate to withdraw the National Lexicography Units Bill (DACST 1996) and to assign the proposed functions to PanSALB. It was envisaged that PanSALB would have a strong language promotion and development function and that the national lexicography units should rather be established in terms of the revised PanSALB Act and not under a separate Act as was contemplated by DACST. The PanSALB Act was therefore redrafted to incorporate the establishment of national lexicography units. The National Lexicography Units Bill (DACST 1996) was repealed and its various sections were incorporated as articles into the PanSALB Act 59 of 1995 (as amended in 1999).

The PanSALB amendment Act of 1999 made provision for the establishment of eleven national lexicography units (NLUs). The amended PanSALB Act stipulated that every national lexicography unit should be established at a tertiary institution in the geolinguistic area where the most first-language speakers of the relevant language reside, that they should have to function according to business plans and that they would receive funding accordingly (cf. National Lexicography Units Bill, DACST 1996; PanSALB 2000: 26-27; Alberts 1996; 1997; 2011: 27-37).

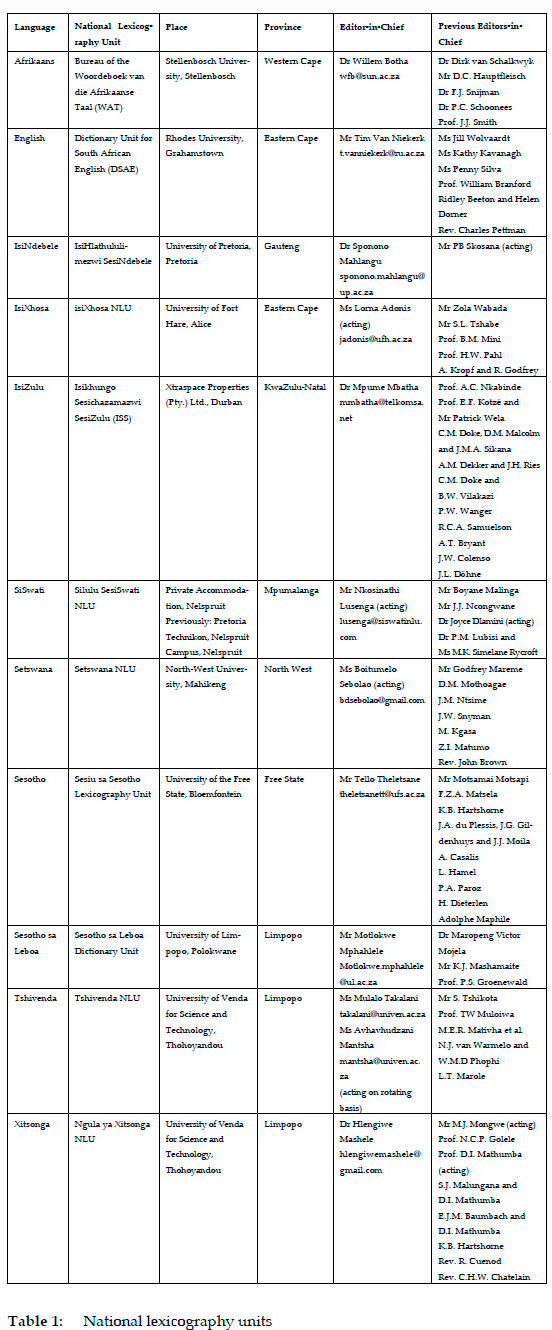

The NLUs were established as Section 21 Companies (PanSALB 2000: 26). Although the NLUs receive funding from PanSALB, they are autonomous (Alberts 2011: 30, 34-35). They are managed by editors-in-chief and function under the auspices and supervision of boards of directors. The Bureau of the WAT and the DSAE became the NLUs for Afrikaans and English, respectively, and remained where they were seated, in Stellenbosch and Grahamstown respectively. Nine African language NLUs were established and they are mainly hosted at tertiary institutions in the geolinguistic area where their majority native language speakers live (cf. Table 1).

Since 2000 eleven national lexicography units (NLUs) were established and they were also registered as non-profit Section 21 Companies in terms of the Companies Act 71 of 2008. The NLUs are:

- The Bureau of the Woordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal (https://www.wat.co.za) is the NLU for Afrikaans and its main aim is to compile a comprehensive Afrikaans dictionary which reflects the standard variety of the language as well as other varieties such as Namakwalands, GriekwaAfrikaans and Kaaps. The Bureau is situated in Stellenbosch and it publishes its own dictionaries and satellite dictionaries from the electronic database. The dictionaries and other products are available as hard copies as well as online (cf. https://www.woordeboek.co.za). The Bureau annually publishes an academic journal Lexikos in the AFRILEX Series in cooperation with the African Association for Lexicography (AFRILEX).

- The office of the Dictionary of South African English on Historical Principles (DSAE) (https://www.ru.ac.za) is situated at Rhodes University in Grahamstown and serves as the NLU for English. The dictionary on historical principles contains typical South African English and reflects the vernacular spoken in South Africa by incorporating borrowings from Afrikaans and all the other indigenous languages. This dictionary changed the local perception of South African English and includes both formal and colloquial words, and terminology which are indispensable to a proper understanding of fields as diverse as politics, the arts, fauna and flora, ritual and religion, the law, geography and agriculture, commerce and industry, history, anthropology, and sociology. South African English is considered an important variety and the DSAE fills this gap in the lexicography of English as a world language. The dictionary is recognized and used as an authoritative source. The products of the DSAE are published by Oxford University Press South Africa (cf. Silva 1996; oxford@oup.co.za).

- Most of the NLUs for the African languages are situated at tertiary institutions within the geolinguistic area of the first-language speakers (cf. Table 1). They are ideally placed to consult with the linguistic communities of the specific areas and with linguists, academics and subject specialists at the tertiary institutions. The NLUs for the African languages were established in 2000-2001 and have already compiled several dictionaries (cf. https://sanlu.africa). These dictionaries are published by the publishing house Jonathan Ball (https://www.jonathanball.co.za).

Every NLU is governed by two constitutive documents, namely:

- A Memorandum of Association (MoA)

- the founding document of a company and to which the founder members are signatories; and

- Articles of Association (AoA) - the document which determines the manner in which a company is supposed to function (cf. PanSALB 2000: 27).

4. The NLUs - the past two decades

An overview of the existence of national dictionary offices in South Africa during the bilingual dispensation stressed the need for national dictionary offices in all the official languages of the country to adhere to the constitutional multilingual prescripts of the new dispensation since 1994. This, in 2000, had led to the establishment of eleven official national lexicography units to document, standardise and preserve the linguistic heritage.

4.1 Cooperative lexicography

The idea of cooperative lexicography already manifested itself in 1991 with the restructuring of the Bureau of the WAT and its consequential suggestion for the establishment of an Institute for Southern African Lexicography. The results of the restructuring and the report on the envisaged Institute for Southern African Lexicography contained information that, at that stage, was indispensable for the further planning of the lexicographical practice in South Africa (cf. §2).

PanSALB had/has a policy of actively promoting the notion of "cooperative lexicography" (cf. PanSALB 2001: 24). The Board established systems of cooperation among all existing NLUs and other lexicographers nationally and obtained particulars of relevant stakeholders (PanSALB 2000: 30; 2001: 24-25). The experience in practical lexicographical work gained by the WAT and DSAE was/is shared with the other nine African language NLUs (cf. PanSALB 2001/2002: 9).

There was a need for a coordinating body to encourage coordination and collaboration amongst NLUs as well as a forum to share similar problems and solutions. The incumbents of editors-in-chief positions created such a committee, the LexiEditors' Forum and they all serve ex officio in the Forum. The PanSALB Board approved the establishment of the LexiEditors' Forum and encouraged the NLUs to cooperate with each other in matters related to lexicography development (cf. PanSALB 2005/2006: 26).

The LexiEditors' Forum is a discussion and consultation group and enables editors-in-chief to share their experiences and information about lexicography and the operation and progress of their particular NLU and to seek solutions to the challenges they all face in their work. The aim of this Forum is therefore to create better working relationships amongst the NLUs and to discuss issues of mutual interest (cf. PanSALB 2004/2005: 38; 2005/2006: 26; 2008; 2010).

Dr Sponono Mahlangu is the current chairperson of the LexiEditors' Forum.

Lexicography is the practice of compiling various kinds of general dictionaries, such as monolingual, bilingual, multilingual or even learners' dictionaries. The main aim of the NLUs is to compile comprehensive monolingual explanatory general dictionaries to preserve and document the respective official languages. Since PanSALB considered lexicography and terminology "to be important building blocks in the development of languages and the promotion of multilingualism" (PanSALB 2000: 26), the NLUs may, according to needs, also compile other types of dictionaries (i.e. bilingual translation, etymological, learners', school and technical dictionaries/term lists) (Alberts 2003: 133; 2011: 23-52; 2017: 158; Wolvaardt 2008).

The comprehensive monolingual dictionaries, bridging dictionaries (i.e. bilingual or multilingual dictionaries) and learners' dictionaries could assist in the preservation and development of the official languages. Multilingualism is sometimes seen as a burden but the NLUs could serve as hubs to enhance mother-tongue instruction at all levels of education. The NLUs were specifically placed in the geolinguistic areas where the most mother-tongue users reside - this was to ensure user participation and collaboration with institutions of learning at all levels of education. The NLUs were furthermore specifically accommodated at or near tertiary institutions - the reason being that the linguists and subject specialists at these institutions could assist the lexicographers. The subject specialists could assist with term creation. The NLUs should furthermore work in close collaboration with the Terminology coordination Section (TCS), National Language Service (NLS), Department of Sport, Arts and culture (DSAc) when creating terms or naming new concepts.

The lexicographic products compiled by the lexicographers at the NLUs are used across a wide spectrum of target users, inter alia by learners, students, educators, academics, the economic sector, scientists, language practitioners, etc. It is therefore essential for lexicographers and other parties interested in the field of lexicography to cooperate as extensively as possible. Such cooperation may take place at various levels, including within and between national dictionary units, with members of the speech community, with language departments at tertiary institutions, with language bodies (i.e. National Language Bodies, Provincial Language Committees), government and semi-governmental institutions, with associations for lexicography and terminology (i.e. AFRILEX, Prolingua, ISO TC/37, SABS TC 37), with the private sector, with language practitioners such as translators, interpreters, terminologists and with the media. Employees of the NLUs are members of AFRILEX and participate regularly in its activities. The NLUs have a specific slot during AFRILEX Conferences to share their experiences.

Ideally cooperative lexicography should lead to joint projects with universities, publishing houses and dictionary units in South Africa, Africa (i.e. Namibia, Gambia, Gabon, Tanzania) and abroad, i.e. the Netherlands, Belgium and the USA.

4.2 Training

The establishment of PanSALB and the NLUs coincided with the establishment of AFRILEX and the editors-in-chief, the lexicographers and members of the boards of directors suddenly had a forum to join and to participate in lexicographical activities. The workshops, seminars, annual conferences and training sessions presented by AFRILEX provided wonderful opportunities to liaise and learn more about their profession.

It was clear that the lexicographic process in South Africa moved into a higher gear with a series of activities aimed at the establishment of national lexicography units for the official South African languages. But many hurdles in respect of training, computer programs, users' needs and bureaucracy had to be overcome (Prinsloo 2000: xiv).

Various training sessions were introduced that facilitated the training of the editors-in-chief, boards of directors and staff of the NLUs in the principles and practice of lexicography, metalexicography, the use of computer hardware and software, the planning of projects and the management of NLUs, negotiation skills and marketing. Some of these training sessions were held at the Bureau of the WAT in Stellenbosch. The insights gained from the strategic planning process at the Bureau of the WAT (cf. § 2) were used to assist the NLUs.

The British Council assisted with training by bringing three experienced British lexicographers and trainers under the leadership of Ms Sue Atkins to run the practical SALEX '97 and AFRILEX-SALEX '98 lexicography training courses under the auspices of the DSAE and AFRILEX in Grahamstown with the main goal of enabling the staff of the newly established NLUs for African languages in the principles and practice of lexicography.

Prof. Rufus Gouws of Stellenbosch University was contracted by PanSALB in 2000 to facilitate, review and revise the then current and proposed projects at existing units, to assist newly established units in deciding what type of dictionary to compile first and to assist with the formulation of a dictionary conceptualisation plan and an instruction book. This resulted in an action plan for the secondary lexicographic process within the NLUs (cf. PanSALB 2001: 24).

Between 27 and 29 November 2000 staff members of existing NLUs were given the opportunity to attend a training course entitled "An introduction to theoretical lexicography and its practical applications". The course was repeated at the end of March 2001 for suitable candidates identified by the boards of directors of the newly established NLUs. Prof. Rufus Gouws was contracted by PanSALB to facilitate these training courses (cf. PanSALB 2001: 23).

PanSALB also facilitated lexicography planning by providing NLUs with information and training on issues such as data collection norms for dictionaries, norms for the inclusion and establishment of micro- and macrostructures for each dictionary project, and developing an editorial style guide for each dictionary to be compiled (cf. Alberts 2011: 37-40).

Further training was presented at the venues of the different NLUs by Prof. Daan Prinsloo of the Department of African Languages, University of Pretoria and Dr Marietta Alberts, at the time Manager of the NLUs at PanSALB.

It is of vital importance that attention should continuously be given to the further training of lexicographers, terminologists and students to enhance knowledge and skills in the principles and practice of general and technical dictionary compilation. Government should give financial assistance for lexicography and terminology awareness campaigns and the training of the practitioners in these fields. Although the training of lexicographers should receive continued attention, it is not clear from PanSALB's annual reports (cf. PanSALB 2008; 2010) whether training at the NLUs is an ongoing activity. Properly trained lexicographers will be able to contribute to the Human Language Technologies (HLT) virtual network (cf. § 4.4).

4.3 Computerisation

The Bureau of the WAT started the computerisation of its lexicographic data by using the Lexi program which was developed especially for the WAT by the HSRC, and DSAE was using X-Write software. Needs assessment studies with regard to computer hardware and software were undertaken by PanSALB in 2000 at the other nine NLUs (cf. PanSALB 2001: 24; 2001/2002: 11).

PanSALB established a relationship with a Swedish company on computational linguistics called Lexilogik AB. Their flagship program, Onoma, replaced the Lexi program at the Bureau of the WAT. PanSALB and Lexilogik AB concluded a contract at the end of March 2001 with regard to the computerisation of the other national lexicography units. After a detailed project plan was drafted during a visit to South Africa by Lexilogik AB at the end of March 2001, the Onoma program had been installed at the Sesotho sa Leboa Dictionary Unit and isiNdebele NLU (cf. PanSALB 2001: 24).

PanSALB also contracted Prof. Danie Prinsloo to assist the NLUs with the process of computerising collected data into a corpus (cf. PanSALB 2001/2002: 11). The process entailed primary practical corpus building and dictionary compilation by using software. The training was done at the NLUs. The training continued during the 2003/2004 financial year (cf. PanSALB 2003/2004: 6-7; 2004/2005: 32; Alberts 2011: 39-40).

The TshwaneLex dictionary-production software, which was developed in South Africa by Mr David Joffe and Prof. Maurice de Schryver, was demonstrated to PanSALB and in the financial year 2004/2005 the Board approved the obtaining of TshwaneLex licenses for the eleven NLUs during the financial year 2005/2006 (cf. PanSALB 2004/2005: 32; 2005/2006: 26). The staff of the NLUs received training in the use of TshwaneLex after the installation of the program at the units.

4.4 Human Language Technologies

The South African Government has approved the development of a national Human Language Technologies (HLT) virtual network. Human Language Technologies include text-based language processing, speech recognition and processing, as well as research into language practice (e.g. lexicography and terminology), culture and technology.

The Department of Science and Technology (DST) and the European Union (EU) jointly on 5 October 2016 announced the establishment of a national centre for digital research, called the South African Centre for Digital Language Resources (SADiLaR). The aim of SADiLaR is to form a national cooperative network with North-West University (NWU) as centre - using a hub and spoke model. SADiLaR is housed at NWU but it functions as a separate entity and is financed by the Department of Science and Innovation (DSI) (Alberts 2017: 386-399).

Several nodes form part of the spokes of the hub. To qualify as node, the institution needs to adhere to certain prescripts. The nodes conduct different projects, based on their experience, expertise and fields of knowledge - there is for instance a digitizing node at the University of Pretoria (UP) and some projects on corpus development, other institutions focus on speech recognition (e.g. the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research [CSIR] focuses on speech corpora built on government speeches), and the Centre for Text Technology (CTexT) of NWU concentrates on language technology, while Stellenbosch University has recently established the Child Speech Node. There is currently no lexicography or terminology-related project at SADiLaR (Calteaux 2021).

SADiLaR funds ad hoc projects and a participating institution could apply for funding without being a node. It could also disseminate language resources through SADiLaR without officially participating in SADiLaR activities. The NLUs should ideally collaborate with SADiLaR.

The hub (NWU) manages a research catalogue and a resource index. Information on language resources that could be downloaded under a specific license could be found in the research catalogue. The resource index on the SADiLaR webpage contains information on interesting available language resources that cannot be disseminated by SADiLaR.

Any institution or body (i.e. NLU) who might be interested in presenting its data to SADiLaR have to ensure that copyright issues are taken care of. The institution should present a data management plan to SADiLaR when it requests SADiLaR to fund and/or manage its project. This data management plan contains all the relevant project information and SADiLaR would be in a position to determine whether and how it would be managed/funded.

The institution who would like to collaborate with SADiLaR chooses the type of license for the dissemination of its data (open source or payable) and the data is as such available to any other institution or person for utilization. SADiLaR aims to reuse data as much as possible and to discourage duplication and a proliferation of data and projects.

Data is supplied to SADiLaR in the form of a complete corpus, and it would then determine whether the data adheres to the prescripts. Information on how to present data to SADiLaR is available on its webpage www.sadilar.org. SADiLaR presents information on new projects on the research index as soon as possible. The research index is basically an online database.

Copyright remains with the collaborating institution, and SADiLaR acts only as the disseminating agent. The value added by SADiLaR to any collaborating project is the availability of a disseminating platform, its expertise in the correct/international acceptable minimum standards and how to make the data universally accessible. If language-related data and information on language resources are available at a central hub, it makes it easier to find, access and utilize. The information is available to everyone and everywhere - national and international. Some of the data is open source, but various resources are also available under different licenses, cf. https://www.sadilar.org/index.php/en/.

SADiLaR assists with skills development and conducts workshops, etc. Unfortunately, there is still a great deal of ignorance relating to HLT and people are reluctant to share data - they basically do not understand the value of shared information - a commodity especially valuable regarding language research and development in a multilingual country where several languages need to be developed. Several individuals maintain an individualistic perspective towards data sharing - they do not realize that shared information is to the benefit of all collaborators. This is especially true in a multilingual country with limited financial resources, and trained and skilled individuals for the many language-related tasks at hand.

SADiLaR is a strategic platform for any NLU to deposit its lexicographical data for national and international dissemination. SADiLaR houses various types of language-related data and language resources, it manages access to data and protects the interests of all collaborating bodies. Any lexicographical contribution would therefore be an asset to the development of the country's languages on a more formal, organized and structured basis. Multilingual lexicographical data needs to be shared in order to be utilized.

All lexicographical and terminographical endeavours could in future be part of the HLT virtual network. Multilingual words and terms would then be available on the HLT virtual network to end-users such as linguists, academics, subject specialists, students, language practitioners and the general public.

Should the lexicographical data of the NLUs be made available in electronic format on an intranet and the internet, the national SADiLaR HLT virtual network would benefit in the following ways (cf. Alberts 2017: 324-325; 329-400):

- The data will be available in electronic format, for example on the web pages of tertiary institutions, and could, after verification and authentication by experts (e.g. NLBs), become part of the virtual network of the HLT program.

- The HLT initiative is government funded and funds will be made available for training and reskilling of language practitioners, i.e. lexicographers and terminographers.

- As part of the HLT virtual network these multilingual lexicographical data will be available to a range of end-users, either free of charge or payable.

- The official South African languages will be in a better position to develop into functional languages, and they will also become available and recognized internationally.

- All lexicographical and terminographical projects will be part of the HLT virtual network.

- It is noted that Dutch-speaking countries such as the Netherlands and Belgium, and the Flemish-speaking part of Belgium are interested in Afrikaans. Afrikaans would therefore also be made available internationally to Dutch/Flemish-speaking communities (Alberts 2014).

4.5 Dictionaries and education

In October 2010 the Department of Higher Education and Training held a Roundtable discussion on the position and developmental status of the African languages. According to the Language Policy in Higher Education, the use of South African languages in instruction and learning in higher education will require development of dictionaries and other teaching and learning materials. The existence of various general dictionaries compiled by the NLUs of PanSALB; the various multilingual terminology lists compiled by the terminologists of the Terminology Coordination Section (TCS) of the National Language Service (NLS), Department of Sport, Arts and Culture (DSAC); and other teaching and learning materials that have been produced were acknowledged. The questions, however, raised by the delegates were whether these dictionaries and materials were enough to meet the requirements of the target groups and whether more should be done to meet the requirements of constitutional multilingualism and target users. It was agreed that the state should start with systematic and widespread translation into African languages, supported by lexicography work and terminology development. It was further agreed that more funding should be made available to dictionary compilation efforts, albeit general or technical dictionaries (Alberts, Botha and Kapp 2010; Nosilela 2010).

It should be noted that there is an escalating consciousness in Africa and worldwide on the positive impact of multilingualism, especially on the role of African languages in advancing multilingualism in education. This is reflected in the language policies that acknowledge the need for the acquisition of and teaching in these languages at all levels of education (cf. Bamgbose 1991: 109-111; Alberts 2017: 149-172). It is a given that mother-tongue instruction is to the benefit of learners at all levels of education - foreign concepts are conceptualized best through one's mother tongue/first language.

According to Maseko (2012: 10) various arguments (i.e. pedagogic, economic, socio-cultural, linguistic and political) are valid for advancing the use of multilingualism in education. There is currently widespread agreement that the problem of sustainable development is more likely to be solved if indigenous knowledge systems and languages are valued and brought into play (Emejulu 2003: 195). The comprehensive monolingual and other dictionaries compiled by the NLUs could help solve developmental problems at all levels of education.

4.6 Lexicographic products of the NLUs

The compilation of a comprehensive monolingual dictionary is a long, complex and demanding process. The data collected during this process could and should also be utilized for other dictionary projects, such as the variety of dictionaries compiled by the Bureau of the WAT (cf. § 2). Cooperative lexicography between the various NLUs could also mean compiling multilingual or bilingual dictionaries. The latter should be the more practical choice and probably the better choice for the compilation of learners' or school dictionaries. The education system would benefit from bilingual dictionaries to assist learners with decoding and encoding activities.

Although the compilation of a bilingual dictionary presents the added difficulty of working with two languages, collaboration, cooperation and shared responsibility can ease the burden. Cooperation between colleagues of different NLUs should enhance working relationships, build capacity and create a strong national resource for the future since the final dictionary/dictionaries would likely be better products as the result of ongoing discussion and refinement (cf. Kavanagh 2003: 240).

Although it seems as if PanSALB interprets its mandate as the monitoring of languages through the NLBs and PLCs rather than the preservation and development of languages, its NLUs continue to develop mono- and bilingual general dictionaries in the eleven official languages. PanSALB indicated that it would like to extend the lexicography activity to the Khoi, Nama and San languages and the South African Sign Language (SASL). The consequence would be the establishment of two additional national language units with the possibility for potentially more on-demand NLUs (https://static.pmg.org.za/PanSALB_Annual_Performance_Plan_for_2020-2021_Compressed.pdf).

A comprehensive catalogue on the various dictionary products compiled by the NLUs can be found at https://sanlu.africa. There are user-friendly Foundation Phase CAPS picture dictionaries beautifully designed and illustrated to meet the requirements of CAPS Foundation Phase for Grades 1 -3. There are also monolingual mother-tongue and bilingual dictionary publications for Intermediate phase Grades 4-6, Senior Phase Grades 7-9, Further Education and Training (FET) schools Grades 11-12 and for tertiary education. PanSALB also published a N/uu audio visual dictionary. These dictionaries would assure that every child/student has access to lexicographical information in their first languages. The NLB for SASL compiled various sign language videos on neologisms to assist the deaf/hearing-impaired community. The dictionaries/ videos were developed on behalf of the Government of South Africa in response to the country's constitutional mandate that all languages must be treated equally and may no longer be disadvantaged.

4.7 Financing

The current situation is that the government of the day is characterized by multilingualism and therefore the NLUs receive annual government support. The NLUs work with limited funds and limited staff. The current government allocation (2020-2021) to each of the NLUs is R2 308 454-00 which cover business and salaries. The annual allocation and proceeds of dictionary sales are clearly not enough to sustain the lexicographical activities of these dictionary offices. The managements of the NLUs therefore need to create innovative plans and practices to generate more income.

According to the information gained from the PanSALB annual reports, it is evident that PanSALB is only financing the NLUs, and that the NLUs do not receive the kind of assistance they really need, such as continuous training, promotion, development and the monitoring of their managerial and structural issues.

The valuable work done by the NLUs should be more visible. According to Mongwe (2006: 36) the work of the South African NLUs would be of a high standard should the following points be taken into account:

- cooperation with AFRILEX

- continued in-house training

- cooperation with PanSALB structures such as the National Language Bodies (NLBs) and the Provincial Language Committees (PLCs)

- cooperation with stakeholders

- involvement of academics and professional bodies

- cooperation with teachers' organisations

- having a sound relationship with the publishing companies

- cooperation with schools

- consultation with researchers

- using the media such as SABC TV and radio stations, and the national, regional and local newspapers

- conducting community awareness campaigns

- annual general meetings with the geolinguistic community where progress reports could be given to the community served by the NLU.

The NLUs came of age in 2021 and one should suspect them to be independent and self-sufficient. They do, however, still rely to a great extent on the financial support provided by government. The NLUs are essentially the only structures suitable for undertaking the major lexicography endeavours they do, but they need to be subsidized and supported substantially if multilingualism is to be taken seriously. In 2011 it was suggested that consideration should be given to moving all lexicographical, terminographical and translation/interpreting activities to the NLUs in order to properly provide language services to the citizens of South Africa. It was furthermore suggested to remove the NLUs from PanSALB and to establish an independent (virtual) South African Institute for Lexicography and the other language-related practices to manage the decentralized NLUs in their respective geolinguistic areas at or near tertiary institutions (cf. Alberts 2011: 50-51). Such a national institute might function under the auspices of the Department of Higher Education or preferably under SADiLaR (cf. § 4.4), and could promote government and citizens' awareness of the value of multilingual language services for communication purposes.

5. Conclusion

An overview of the past thirty years indicated that the Bureau of the WAT played a significant role in the current lexicography practice in South Africa. Experiences gained from the restructuring at the Bureau of the WAT, the creation of Lexikos and the establishment of AFRILEX, PanSALB and the NLUs paved the way for the past 21 years' cooperative lexicography in South Africa, Africa and internationally. Cooperation is a two-way, give-and-take process and everyone involved should be prepared to contribute and learn. The needs of potential users should be taken into account and the contributions by lay-people, linguists, academics, subject specialists, terminologists, translators, journalists, teachers and students should always be considered when compiling the much-needed dictionaries in our official South African languages. Such collaboration would create a sense of ownership in the dictionaries compiled by the respective NLUs.

Bibliography

Alberts, M. 1993. Feasibility Study: Institute for Southern African Lexicography/ Lewensvatbaarheidstudie: Instituut vir Suider-Afrikaanse Leksikografie. Stellenbosch: Bureau of the WAT. [ Links ]

Alberts, M. 1996. Background Information on the Drafting of the National Lexicography Units Bill. Unpublished document. Pretoria: DACST. [ Links ]

Alberts, M. 1997. Reallocation of Funds to be Used for Lexicography Training and Lexicography Awareness Campaign. Pretoria: DACST. [ Links ]

Alberts, M. 2003. Appointment of Editors-in-Chief. Unpublished paper read at the PanSALB workshop held at the Sinodale Building, Visagie Street on 3 March 2003 in Pretoria.

Alberts, M. 2011. National Lexicography Units: Past, Present, Future. Lexikos 21: 23-52. [ Links ]

Alberts, M. 2014. Terminology Development at Tertiary Institutions: A South African Perspective. Lexikos 24: 1-26. [ Links ]

Alberts, M. 2017. Terminology and Terminography Principles and Practice: A South African Perspective. Milnerton: McGillivray Linnegar Associates. [ Links ]

Alberts, M. 2019. Terminologie en terminografie. 'n Handleiding. Pretoria: SAAWK. [ Links ]

Alberts, M., W.F. Botha and P.H. Kapp. 2010. Historical Experiences in Developing Afrikaans as a Language. Paper presented at the Roundtable on African Languages, organized by the Department of Higher Education and Training, held on 22 October 2010, Unisa, Sunnyside Campus, Pretoria.

Alberts, M. and B. Nieuwoudt. 1992. Die LEXI-program: 'n Gerekenariseerde woordeboekprogram. Verslag LEXI-12. Pretoria: HSRC. [ Links ]

Bamgbose, A. 1991. Language and the Nation: The Language Question in Sub-Saharan Africa. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [ Links ]

Botha, W. (Ed.). 2003. 'n Man wat beur. Huldigingsbundel vir Dirk van Schalkwyk. Stellenbosch: Bureau of the WAT. [ Links ]

Botha, W. 2003a. Van die redakteur/From the Editor. Botha, W. (Ed. ). 2003: x-xii.

Botha, W. 2003b. Die renaissance van die Woordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal. Botha, W. (Ed.). 2003: 49-70.

Bureau of the Woordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal. 1989. Verslag oor die strategiese beplanning vir die Buro van die Woordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal. Unpublished report. Stellenbosch: Bureau of the WAT. [ Links ]

Bureau of the Woordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal. 1991. Report of the Board of the Woordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal for the period 1 April 1990 to 31 March 1991. Stellenbosch: Bureau of the WAT. [ Links ]

Bureau of the Woordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal and Vriende van Afrikaans. 2011/2019. Basic Afrikaans. The Top 1 000 Words and Phrases. Cape Town: Pharos Dictionaries. [ Links ]

Calteaux, K. 2021. Information on SADiLaR. Private email. CSIR, Pretoria, 22 February 2021.

Department of Arts and Culture (DAC). 2002. National Language Policy Framework, Final Draft. Pretoria: Department of Arts and Culture (DAC). [ Links ]

Department of Arts and Culture (DAC). 2011. Presentation to the Portfolio Committee: Arts and Culture on the South African Languages Bill 2011, 16 November 2011. Pretoria: Department of Arts and Culture. [ Links ]

Department of Arts, Culture, Science and Technology (DACST). 1995. Towards a National Plan for South Africa. A Report of the Language Plan Task Group. (LANGTAG Report) Pretoria: Department of Arts, Culture, Science and Technology. [ Links ]

Department of Arts, Culture, Science and Technology (DACST). 1996. National Lexicography Units Bill. (As introduced) [B 103-96]. Wetsontwerp op Nasionale Leksikografie-eenhede. (Soos ingedien) [W 103-96]. Pretoria: Minister of Arts, Culture, Science and Technology, Department of Arts, Culture, Science and Technology (DACST). [ Links ]

Department of Arts, Culture, Science and Technology (DACST). 1997. PanSALB and the Tabling of the National Lexicography Units Bill. Unpublished document (5/3/2/7/2/3). Pretoria: Department of Arts, Culture, Science and Technology (DACST). [ Links ]

Department of Sport, Recreation, Arts and Culture (DSRAC). 2005. Language Policy Framework of the Gauteng Provincial Government. Johannesburg: Gauteng Provinsiale Regering. [ Links ]

De Vries, M.J. 1989. Jaarverslag van die Beheerraad van die WAT. 1 April 1988-31 Maart 1989.

Emejulu, J.D. 2003. Challenges and Promises of a Comprehensive Lexicography in the Developing World: The Case of Gabon. Botha, W. (Ed.). 2003: 195-212.

Ferreira, D.M. 2002. Terminologiebestuur in Suid-Afrika met spesifieke verwysing na die posisie van histories ingekorte tale. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis. Bloemfontein: University of the Free State. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. 2003. Oor patriotte en ander leksikografiese vernuwers. Botha, W. (Ed.). 2003: 71-85.

Government Gazette. 2012. Use of Official Languages Act 12 of 2012. Government Gazette 568(35742), 2 October 2012. Cape Town: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Kavanagh, Kathryn. 2003. Co-operative Lexicography - Developing Bilingual Dictionaries. Botha, W. (Ed.). 2003: 231-241.

Maseko, P. 2012. Advancing the Use of African Languages in SA Higher Education. Strategies, Challenges and Opportunities. Paper read at the Closed Workshop on Verification of Scientific Terminology and International Translation Day, 28 September 2012, CPUT, Bellville Main Campus.

Mongwe, M.J. 2006. The Role of the South African National Lexicography Units in the Planning and Compilation of Multifunctional Bilingual Dictionaries. Unpublished M.Phil. Thesis. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University. [ Links ]

Nosilela, B. 2010. Current State of African Languages in Institutions of Higher Learning. Paper presented at the Roundtable on African Languages, organized by the Department of Higher Education and Training, held on 22 October 2010, Unisa, Sunnyside Campus, Pretoria.

PanSALB. 2000. Annual Report. Pretoria: Pan South African Language Board (PanSALB).

PanSALB. 2001. Annual Report. Pretoria: Pan South African Language Board (PanSALB).

PanSALB. 2002. Annual Report 2001/2002. Pretoria: Pan South African Language Board (PanSALB).

PanSALB. 2004. Annual Report 2003/2004. Pretoria: Pan South African Language Board (PanSALB).

PanSALB. 2005. Annual Report 2004/2005. Pretoria: Pan South African Language Board (PanSALB).

PanSALB. 2006. Annual Report 2005/2006. Pretoria: Pan South African Language Board (PanSALB).

PanSALB. 2008. Annual Report 2007/2008. Pretoria: Pan South African Language Board (PanSALB).

PanSALB. 2010. Annual Report 2009/2010. Pretoria: Pan South African Language Board (PanSALB).

Prinsloo, D.J. 2000. A Few Words from AFRILEX. Lexikos 10: xiv. [ Links ]

Silva, P. (Ed.) 1996. A Dictionary of South African English on Historical Principles. Cape Town/Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press [ Links ]

Van der Berg, D.Z. (Ed.). 1998. Oorbrugging. 'n Huldigingsbundel vir Wilfred Jonckheere. Howick: Brevitas. [ Links ]

Van Schalkwyk, D.J. 1998. Die transformasie van die Buro van die Woordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal gedurende die afgelope dekade. Van der Berg, D.Z. (Ed.). 1998: 141-152.

WAT. 1926-. Woordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal. Stellenbosch: Bureau of the WAT. [ Links ]

Wolvaardt, J. 2008. Summary of NLU Products and Ongoing Projects (Updated July 2008). Unpublished document. LexiEditors' Forum.

Legislation

Companies Act 71 of2008.

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa Act 108 of 1996. (Now Constitution, 1996.)

Pan-South African Language Board Act 59 of 1995, Amendment Act 10 of 1999.

Use of Official Languages Act 12 of 2012.

Woordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal Act 50 of 1973, Amendment Act 9 of 1986, Amendment Act 22 of 1991.

Internet References

https://www.jonathanball.co.za

https://www.sadilar.org/index.php/en/

https://static.pmg.org.za/PanSALB_Annual_Performance_Plan_for_2020-2021_Compressed.pdf