Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Lexikos

versión On-line ISSN 2224-0039

versión impresa ISSN 1684-4904

Lexikos vol.32 spe Stellenbosch 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.5788/32-2-1700

ARTICLES

The Intellectualization of African Languages through Terminology and Lexicography: Methodological Reflections with Special Reference to Lexicographic Products of the University of KwaZulu-Natal

Die intellektualisering van Afrikatale deur middel van die terminologie en leksikografie: Metodologiese gedagtes met spesifieke verwysing na leksikografiese produkte van die Universiteit van KwaZulu-Natal

Langa KhumaloI; Dion NkomoII

ISouth African Centre for Digital Language Resources, North West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa (langa.khumalo@nwu.ac.za)

IISchool of Languages and Literatures: African Language Studies, Rhodes University, Makhanda, South Africa (d.nkomo@ru.ac.za)

ABSTRACT

Terminology development and practical lexicography are crucial in language intellectualization. In South Africa, the Department of Sport, Arts and Culture, National Lexicography Units, universities, commercial publishers and other organizations have been developing terminology and publishing terminographical/lexicographical resources to facilitate the use of African languages alongside English and Afrikaans in prestigious domains. Theoretical literature in the field of lexicography (e.g., Bergenholtz and Nielsen (2006); Bergenholtz and Tarp (1995; 2010); Gouws 2020) has attempted to resolve traditional distinctions between lexicography and terminology while also addressing terminological imprecisions in the relevant scholarship. Taking the cue from such scholarship, this article reflects on the methodological approaches for developing lexicographical products for specific subject fields, i.e., resources that document and describe terminology from specialized academic and professional fields. Its focus is on the use of traditional methods vis-à-vis the application of electronic corpora and its technologies in the key practical tasks such as term extraction and lemmatization. The article notes that the limited availability of specialized texts in African languages hampers the development and deployment of advanced electronic corpora and its applications to improve the execution of terminological and lexicographical tasks, while also enhancing the quality of the products. The Illustrated Glossary of Southern African Architectural Terms (English-isiZulu), A Glossary of Law Terms (English-isiZulu) and the forthcoming isiZulu dictionary of linguistic terms are used for special reference.

Keywords: intellectualization of African languages, lexicography, termiNOLOGY, TERMINOGRAPHY, DICTIONARY, SUBJECT FIELD DICTIONARIES, SUBJECT FIELD LEXICOGRAPHY, GLOSSARY, ELECTRONIC CORPORA

OPSOMMING

Teminologieontwikkeling en praktiese leksikografie is noodsaaklik in taalintellektualisering. In Suid-Afrika het die Departement van Sport, Kuns en Kultuur, die Nasionale Lesikografieeenhede, universiteite, kommersiële uitgewers en ander organisasies die terminologie ontwikkel en terminologiese/leksikografiese hulpbronne gepubliseer om die gebruik van Afrikatale neffens Engels en Afrikaans in toonaangewende domeine te bevorder. Teoretiese literatuur in die leksikografieveld (soos Bergenholtz en Nielsen (2006); Bergenholtz en Tarp (1995; 2010); Gouws 2020) het pogings aangewend om die tradisionele onderskeid tussen die leksikografie en die terminologie te ontleed en terselfdertyd die terminologiese onjuisthede in die relevante studieveld aan te spreek. Vanuit hierdie agtergrond neem dié artikel die metodologiese benaderings tot die ontwikkeling van leksikografiese produkte vir spesifieke onderwerpsvelde, m.a.w. hulpbronne wat die terminologie van gespesialiseerde akademiese en professionele velde dokumenteer en beskryf, in oënskou. Daar word gefokus op die gebruik van tradisionele metodes versus die gebruik van elektroniese korpora en die tegnologie daaraan verbonde in die belangrikste praktiese take soos term-onttrekking en lemmatisering. In die artikel word daarop gewys dat die beperkte beskikbaarheid van gespesialiseerde tekste in Afrikatale die ontwikkeling en benutting van gevorderde elektroniese korpora en die toepassings daarvan verhinder om sodoende die uitvoer van terminologiese en leksikografiese take te verbeter en terselfdertyd die kwaliteit van die produkte te verhoog. Die Illustrated Glossary of Southern African Architectural Terms (English-isiZulu), A Glossary of Law Terms (English-isiZulu) en die toekomstige isiZulu woordeboek van linguistiese terme word as spesifieke verwysing gebruik.

Sleutelwoorde: intellektualisering van afrikatale, leksikografie, terminologie, TERMINOGRAFIE, WOORDEBOEK, SPESIALEVELDWOORDEBOEKE, SPESIALE-VELDLEKSIKOGRAFIE, GLOSSARIUM, ELEKTRONIESE KORPORA

1. Introduction

In South Africa, the declaration of nine indigenous languages as official languages, alongside Afrikaans and English, is yet to achieve the envisaged parity of esteem of all the official languages. English continues to dominate prestigious professional and academic spaces at the expense of mother-tongue speakers of other official languages. Government departments have expressed commitment towards multilingualism by formulating and adopting language policies as per the imperatives of the Use of Official Languages Act, while institutions of higher learning have done likewise in response to the Language Policy for Higher Education. However, the implementation of language policies in ways that promote multilingualism and parity of esteem among the official languages remains elusive. Multilingualism in official government communication, including the translation of important official documents, as well as the use of African languages as academic languages in the country's universities, remains handicapped by terminological problems. According to Alberts (2017: 148), terminology is thus "a strategic resource and has an important role in the functional development of a country's languages and their users - especially in a multilingual country".

Indeed, the collection, creation, documentation and description of terminology, generally referred to as terminography, remains a vital undertaking for the intellectualization of African languages. In this contribution, we follow the guidance in Bergenholtz and Tarp (1995; 2010) and Bergenholtz and Nielsen (2006) who dismiss the existence of fundamental disciplinary differences between terminology, particularly terminography, and specialized lexicography. While we recognize their flexible approach in favour of specialized lexicography, for this article we embrace further meticulous disambiguation by Gouws (2020), who indicates that subject field lexicography is the more precise term for the branch of lexicography concerned with dictionaries that deal with language or knowledge of specialized disciplines, and subsequently subject field dictionaries as the products of this field. In so doing, we are recognizing as dictionaries even the rudimentary products by compilers with various professional disciplinary inclinations, including those who would not recognize themselves as lexicographers. For example, some of the compilers regard themselves as terminologists, translators or just subject specialists who seek to provide cognitive and communicative support to non-experts, e.g., students who are challenged by the language used in specific subject fields. This is common in African languages. Our interest is not really on the products per se, i.e., whether they qualify to be called dictionaries, but on the methodologies that are used to perform critical tasks in the compilation of special field dictionaries regardless of their scope and depth. We focus on the identification of terms from various sources for lemmatization and lexicographical treatment, as well as the preceding activities, bearing in mind the fact that terminology development remains an integral part of compiling special field dictionaries in African languages. We are interested in reflecting on methodological advances in this enterprise in the light of electronic corpora and the relevant corpus query tools which have expedited lexicographic processes against the challenges posed by lagging intellectualization of African languages. The experience of compiling three subject field dictionaries at the University of KwaZulu-Natal is used for special reference.

2. The intellectualization of African languages through terminology and lexicography

The imperative to intellectualize African languages for expanded functional use in all spheres of life is vital against centuries of their prolonged neglect in favour of colonial languages from Africa's early encounters with foreign settlers from Europe. In the context of skewed power relations that associated Europe with progress on the one hand and Africa with primitiveness on the other, languages such as English, French and Portuguese dominated all the formal public domains of life which privileged written languages. Without a strong literary history, African languages were relegated to the domestic lives of their speakers and peripheries of the new socio-economic, cultural and political order. This meant that the languages could not keep abreast with the development of the modern society. Havranek (1932: 32) defines intellectualization of a language as:

[I]ts adaptation to the goal of making possible precise and rigorous, if necessary abstract, statements, capable of expressing the continuity and complexity of thought, that is, to reinforce the intellectual side of speech. This intellectualization culminates in scientific (theoretical) speech, determined by the attempt to be as precise in expression as possible, to make statements which reflect the rigor of objective (scientific) thinking in which the terms approximate concepts and the sentences approximate logical judgements.

While Havranek's description of language intellectualization beyond doubt indicates the mammoth task of intellectualizing African languages today, it is important to put it into perspective. Writing in the preface of his famous dictionary, Samuel Johnson had this to say about the English language in the late 18th century:

When I took the first survey of my undertaking, I found our speech copious without order, and energetic without rules: wherever I turned my view, there was perplexity to be disentangled, and confusion to be regulated; choice was to be made out of boundless variety, without any established principle of selection; adulterations were to be detected, without the sufferages of any writers of classical reputation or acknowledged authority (Crystal 2005: 21).

Johnson's impression clearly suggests that English could not be used to make precise, rigorous, abstract statements to express complex thoughts in a logical way at the time of his writing. If we compare this to isiXhosa in the impression of one of the foremost 19th century isiXhosa lexicographers, John W. Apple-yard, one would argue that isiXhosa bore some vital qualities of an intellectualized language. Appleyard wrote:

How came (sic) these people or their ancestors, centuries ago, to express them in this way, and to adopt this system of alliteration. No one can tell; but whatever their language is; and whatever may have been its origin, the [isiXhosa speakers] themselves are not an intellectually (original emphasis) childish race. In all grammatical variations of form, [the] language is eminently distinguished by system and regularity. It is ... correctly spoken by all classes of the community, which is not the case, perhaps, with any of our European tongues. As a very general, if not invariable rule, [an isiXhosa speaker] will never be heard using an ungram-matical expression (Appleyard 1850: 67-68).

The perspective that is needed is that the assessment of language intellectualization ought to be contextualized. In the precolonial context with a stable African epistemological order, African languages would undoubtedly serve their speakers optimally in all their intellectual activities, which the English language could not do during Johnson's time in England. English was a disorderly language in terms of Johnson in comparison to Greek and Latin, which had hegemonic roles in Europe, and other emerging standard languages such as Italian and French, which were benefiting from the work of the language academies (Nkomo 2018). African languages were found wanting with the advent of a new intellectual order in which "an intellectualized language [w]as one which can be used for educating a person from kindergarten to the university and beyond" (Sibayan 1991: 229). What is unquestionable is Sibayan's general identification of the goal of intellectualization as that of developing the language "for use in the controlling domains of language" (Sibayan 1991: 72). The introduction of a new idea of intellectualism at the onset of European colonization was accompanied by a decentring of African languages, leading Kaschula and Nkomo (2019) to argue that the languages were in fact de-intellectualized and what they now need is re-intellectualization in the context of the new intellectual order that draws on multiplicity of epistemologies.

While the introduction of print in African languages was a significant milestone of their intellectualization for the modern world, it would not be sufficient since the goals of this partial intellectualization did not transcend the use of the languages for evangelization purposes. It is largely in this respect that Gouws (2007) classifies the earliest dictionaries in African languages as externally-motivated, since the dictionaries were primarily for the use of missionaries and other European settlers who wanted to learn the languages rather than for the empowerment of the native speakers. This would include dictionaries that were produced for use within the education system, such as the Oxford English-Xhosa Dictionary that was compiled to address the challenges experienced by second language learners of isiXhosa, most of whom were English-mother tongue speakers (Fischer et al. 1985: v). It is, therefore, not easy to talk about the intellectualization of African languages in a context where the interests of the language speakers were not a priority. This is not meant to disregard, for example, lexicographical and terminological work in African languages during the missionary and apartheid period in South Africa. In fact, we concur with Mahlalela-Thusi and Heugh (2002: 255) that present efforts to intellectualize African languages need to take "cognisance of the huge amount of work that has already been undertaken in the past" because "[t]here could be much value in a thorough analysis of both terminology and materials published in the past as this could speed up the process of producing modern and appropriate" resources. However, when we consider the broad aim of intellectualizing African languages, we note that these efforts were limited in the sense that they did not seek to empower the speakers of African languages to use their languages to their optimal level as intellectual resources. It is in recogni tion of this limitation that Mesthrie (2008) argues that while it is necessary to use African languages in higher education, the conditions for their use remain insufficient. More work still needs to be done.

National Lexicography Units (NLUs) were established primarily to "conserve, preserve, research and document the official languages concerned, by compiling a monolingual explanatory dictionary and such other dictionaries (authors' emphasis) as may be required to satisfy the needs of the target users of that language" (PanSALB 2000: 26). The compilation of monolingual explanatory dictionaries was already firmly established at the Bureau of the Woordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal (WAT) and Dictionary Unit for South African English (DSAE) for in Afrikaans and English respectively since 1926 and 1969 (Gouws 2007). The envisaged dictionaries were the so-called storehouse of the words of a language which were expected to raise the profile of each official language, particularly the African languages which lacked strong lexicographic traditions.

However, subject field dictionaries only featured anecdotally in the conceptualization of the NLUs through the add-on clause "and such other dictionaries" in the previous quotation. This add-on clause permits the NLUs to produce a variety of spin-off products including school dictionaries. This does not diminish the role of those other dictionaries as they are "required to satisfy the needs of the target users of that language" (PanSALB 2000: 26). They are essential for all the official languages to be used on parity with English in specialized professional and academic disciplines. As Lukasik 2016: 211) puts it, in educational contexts, subject field dictionaries serve "the most important ... pedagogical (didactic) function". In African languages, they do this by providing specialized academic terminology, information about terms and their use, as well as the specialized knowledge embedded in the terms. This indeed makes subject field lexicography critical in the intellectualization of previously marginalized languages.

From an organized language planning perspective, the subject field and terminological needs of speakers of African languages are primarily meant to be served by the Department of Sport, Arts and Culture (DSAC). According to Alberts (2017), through the Terminology Coordination Section, the DSAC was tasked with the responsibility of developing terminology and publishing terminological dictionaries. To that end, DSAC has produced several multilingual terminology lists whose compilers also refer to as dictionaries (http://www.dac.gov.za/terminology-list). These include the following:

- Multilingual Pharmaceutical Terminology List

- Multilingual Financial Terminology List

- Multilingual Human, Social, Economic and Management Sciences Terminology List

- Multilingual Natural Sciences and Technology Term List (Sesotho)

- Multilingual Natural Sciences and Technology Term List (Tshivenda-Xitsonga)

- Multilingual Natural Sciences and Technology Term List (Nguni)

- Multilingual Mathematics Dictionary: Grade R-6

- Multilingual HIV/Aids Terminology

- Multilingual Parliamentary/Political Terminology

- Multilingual Terminology for Information Communication Technology

The DSAC has produced most of the above-listed resources under its "Schools Project" which is dedicated to the "documentation of existing terminology, and facilitation of the development of terminology in the African languages for new concepts that appear in the teaching materials for Grades 1 to 6" (DAC 2013a: v). The same motivation has inspired the production of more or less similar products by the Project for the Study of Alternative Education in South Africa (PRAESA), which compiled the Illustrated Multilingual Science and Technology Dictionary - Intermediate Phase (English-Afrikaans-Xhosa). Commercial publishers have also published a few multilingual subject field dictionaries for use within the education system. Examples include the Maskew Miller Longman's Longman Multilingual Maths Dictionary for South African Schools: English, isiXhosa, Afrikaans and Cambridge university Press's Isichazi-magama seziBalo Sezikolo saseCambridge. The source of the motivation is the Language-in-Education Policy (LiEP), adopted in 1997, which acknowledges "the cognitive benefits [...] of teaching through one's medium (home language)". A similar motivation derived from the Language Policy for Higher Education (LPHE) of 2002 has motivated subject field lexicography that seeks to produce tools that support the use of African languages in higher education. The LPHE expressly identifies dictionaries as necessary for the effective infusion of African languages in higher education. The production of multilingual academic terminology resources (glossaries) is a key activity in South African universities, see in this regard the open Education Resource Term Bank (OERTB, http://oertb.tlterm.com/), which was a government-funded project, jointly run by the university of Pretoria and the university of Cape Town. The three dictionaries produced at UKZN, which serve as major references in this paper, are further examples.

3. Quality issues of subject field dictionaries in African languages

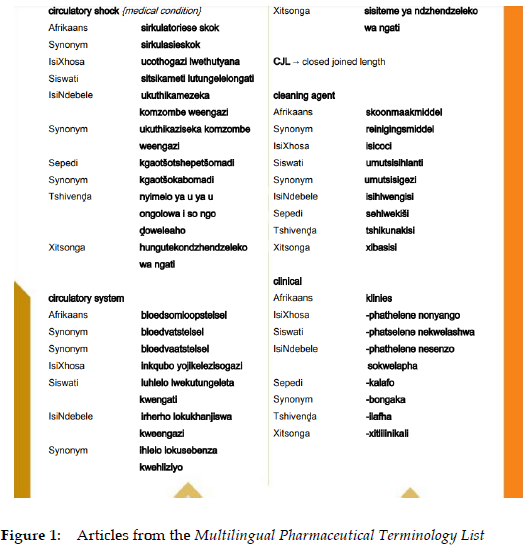

The production of subject field dictionaries in African languages has been under-researched and under-theorized compared to other dictionary types. However, this is not peculiar to African languages. Gouws (2020: 244) quotes Kilgarriff (2012) who emphasizes that "general language dictionaries are central to the lexicographical firmament", and this includes the space in dictionary research and lexicographic theory. Dictionary criticism has expressed concern with the quality of subject field dictionaries in African languages. According to Gouws (2013: 52), "[...] lack of concern with LSP dictionaries [has] led in far too many cases to LSP dictionaries not really qualifying as dictionaries but merely playing an inferior role as word lists or other restricted (and often handicapped) reference products". The articles from DASC's Multilingual Pharmaceutical Terminology List (http://www.dac.gov.za/sites/default/files/terminology/Multilingual%20Pharmaceutical%20Terminology%20List.pdf) shown below illustrate this concern.

The Multilingual Pharmaceutical Terminology List is a typical example of the publications of the DSAC within the Schools Project. While the publications provide the much-needed multilingual terminology to facilitate the use of African languages in education and other areas, the users are not provided with sufficient information that facilitates an understanding and appropriate use of the terms. With most of these products targeted at school learners, they could have been more impactful with additional explanatory and illustrative data.

Indeed, most of them are generally rudimentary multilingual terminology lists in which the word dictionary is used tentatively in introductory texts but not on the covers.

Quality issues in subject field dictionaries in African languages do not only manifest themselves in the form of limited data. Nkomo (2019) also identifies inclusion of irrelevant data in relation to the target users of some dictionaries, even though this is a less prevalent problem. Examples include part of speech data and tonal marking in dictionaries that will be used in specialized fields where the teaching of grammar is not a priority. In such cases, one notes that compilers of subject field dictionaries merely copy practices and procedures from other dictionary types with different purposes. Ironically, while doing so, the compilers often neglect vital lexicographical aspects such as the planning of dictionary structure. Microstructures and outer texts are underutilized in the planning of subject field dictionaries to enhance the quality of presentation and accessibility of dictionary contents. Gouws (2020) demonstrates that dictionary structure is equally important in subject field dictionaries when he writes:

Where the compiler of such a dictionary takes the necessary cognizance of guidelines from a general theory of lexicography such a dictionary can become a good dictionary not only on account of the contents but also due to the appropriate dictionary structures and an adherence to the user-perspective and the relevant lexicographic functions (Gouws 2020: 167).

However, the most crucial quality issue with some subject field dictionaries stems from undefined dictionary databases and haphazard lemma section. This is an issue that the subsequent sections of this paper focus on, first demonstrating how term harvesting and description have generally been approached in African languages before focusing on the UKZN projects. We consider this to be a crucial issue because it may result in the exclusion of critical subject terminology that the users need the most in order to use African languages in the high function domains. As crucial tools in the intellectualization of languages, subject field dictionaries in African languages need to be produced in such way that culminates from a scientific language documentation and explication process capable of reflecting the rigor of objective thinking and logical expression.

Nkomo (2019: 104) avers that a major source of quality problems in subject field dictionaries is that "far too often, they are ... constructed by everybody". Generally, most of the resources that may be classified as subject field dictionaries in African languages are compiled by subject-field experts without sufficient lexicographic insight, terminologists, translators and even lexicographers who over-rely on subject-field experts. The main motivation is usually terminology development, after which little consideration is given to explanatory and usage data in relation to the terms, as well as the design and presentation issues of the products in which the terms are accessed. While we do not prescribe who should produce subject field dictionaries, given their interdisciplinary nature, the production of subject field dictionaries needs to be collaborative ventures in which there ought to be a great awareness, meticulous and even creative application of lexicographic principles in order to raise the quality of the products for the benefit of the users who need to get optimal information with high levels of user-friendliness. This remains a challenge in African languages and this challenge is closely associated with the methodologies that are currently being used for key compilation processes.

4. Methodological challenges for subject field dictionaries

Although Tarp (2012) draws his examples from Europe to highlight some challenges of specialized lexicography, his characterization of progress made in this field aptly captures the situation in African languages. Tarp (2012) notes that while the two decades preceding the time of his writing witnessed a proliferation of products under this branch of lexicography, such high-level activity and output upsurge are not matched by quality improvement. He attributes what he regards as disappointing progress in specialized lexicography partly to methodological practices that fail to capitalize on the affordances offered by the developments in science and technology. Likewise, this applies to the situation in African languages.

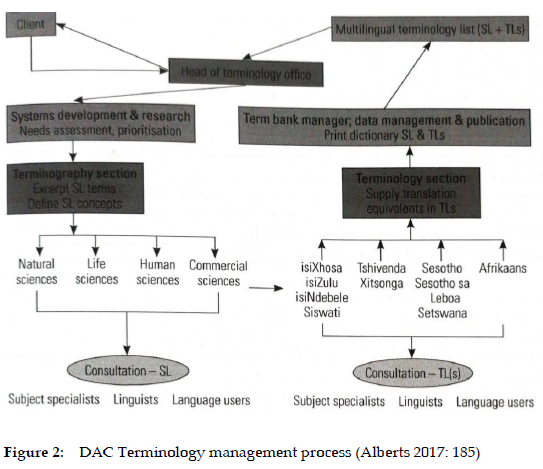

As noted in the previous section, terminology development remains a major priority enterprise in the intellectualization of African languages. In addition to the DSAC, most higher education institutions in South Africa have engaged in bi- or multilingual terminology projects in order to address the perverse "perception that terminology is an intractable obstacle to the use of African languages in high function domains" (Antia and Ianna 2016: 63). The outcome of such investment in the intellectualization of African languages has been the publication of glossaries and special field dictionaries of varying scope and detail. Apart from the problem of duplication of efforts, a standout common feature in the different projects has been the dominance of what Alberts (2017: 179) calls the translation-oriented approach, which she represents in terms of Figure 2 below. This approach is motivated by the fact that African languages have not made a strong footprint in high function domains, resulting in the paucity of specialized texts and terminological gaps in the languages. Thus, the point of departure is usually English terminology lists that are compiled by or with the assistance of subject field experts and the lists are then translated into African languages. The application of this approach is outlined in detail in Legal Terminology: Criminal Law, Procedure and Evidence, an ambitious bilingual explanatory English-Afrikaans/Afrikaans-English dictionary of which the aim was to "compile and publish translated versions in all official languages" (Prinsloo, Alberts and Mollema 2015: iii). The isiXhosa edition, Isigama Sasemthethweni: Umthetho wolwaphulo-mthetho, wenkqubo nobungqina, was published in 2019.

As illustrated in Fig. 2, in most cases, terminologists and subject experts identify the key concepts that need to be captured and described bi- or multilingually. In the case of university projects linked to specific academic subjects, students are sometimes asked to make submissions of what they have experienced to be challenging concepts for inclusion in the projects. The English terminology lists are usually compiled following a manual term extraction process from relevant sources (Alberts 2017). Unsystematic representation of subject fields may also result from the lack of balance in the selection of English texts, e.g., course outlines and academic textbooks that constitute what would become the dictionary basis from which raw data is drawn for a particular subject field dictionary. Even with a balanced dictionary basis, manual term extraction may result in unbalanced macrostructures with glaring conceptual gaps and incomplete terminological paradigms, as illustrated in Taljard and De Schryver (2002).

In the light of the foregoing, the pioneering exploratory work on corpus applications in African languages lexicography by Danie Prinsloo, Gilles-Maurice de Schryver and Elsabe Taljard, among others, held so much promise in the early 2000s. For example, based on a study on the feasibility of semi-automatic term extraction for the African languages (Taljard and De Schryver 2002: 44), recommended the use of specialized corpora and semi-automatic extraction of terminology in the compilation of subject field dictionaries. They argued that "the semi-automatic extraction of terms for the African languages is not only viable, but even crucial in order to counteract inevitable human errors" (Taljard and De Schryver 2002: 66). However, the exciting technological prospects did not blind them to challenges associated with the general level of intellectualiza-tion of African languages, as aptly described in the following quote:

However, if an electronic database is to be compiled for terminological purposes, it presupposes the availability of text material revolving around specific fields. Due to the historically disadvantaged situation of the African languages, even today virtually no subject-specific texts which could be used to build an electronic database are available. As a result of the pre-1994 political and educational system, the vast majority of subject-specific material is written in either English or Afrikaans, with textbooks on literature and grammar of the African languages a possible exception. The African-language terminologist therefore has very little, if any, access to special-field texts which can be used to compile an electronic special-field corpus. This does not only have implications for the compilation of corpora, but also determines the methodology which has hitherto been used by African-language terminologists (Taljard and De Schryver 2002: 47).

While the quotation emphasizes terminology work and terminologists as handicapped by the unavailability of texts in African languages, these problems equally affect translators, lexicographers and virtually all language practitioners who could benefit from specialized corpora. At the time of their writing, the authors were optimistic, though, "that special-language texts will soon be produced on a large scale in the African languages" (Taljard and De Schryver 2002: 47) owing to the official status of the official African languages that was meant to expand their use in the high-status domains. Twenty years on, the situation might have improved, but this would vary according to subject fields, given that English still remains dominant while the use of African languages is regarded as more viable for some subjects, e.g., humanities, than the sciences. This dominance means that African language-texts are mainly produced through translation, which has its own quality challenges as the translations are themselves produced without the assistance of good quality subject field dictionaries and term banks. We are still not in an ideal world where all lexicographic tasks could be automated. In that ideal world, Prinsloo (2014: 1344) compares the role of the lexicographer as that "of the pilot of a fully computerized modern jetliner overseeing processes with limited manual intervention". However, in the real world, Prinsloo (2009: 181) has astutely advised that the corpus "cannot replace the lexicographer, nor should it be regarded as inferior to the knowledge of the lexicographer". The real world of terminology and lexicography in African languages is still dominated by traditional manual processes in which optimal use of specialized electronic corpora still fails to pass the criteria of size, representativeness and balance (Bowker and Pearson 2002). Hence the limited visibility of corpus applications in the UKZN projects is presented as a major methodological challenge for subject field dictionaries in African languages.

5. The case of subject field dictionaries at UKZN

The intellectualization of isiZulu at UKZN has been driven by the University Language Planning and Development Office (ULPDO) in line with the university's language policy and plan (adopted in 2006 and revised in 2014). The policy seeks to promote the development of isiZulu into an academic language as per national sector imperatives. The development, documentation, description and dissemination of terminology for specialised subject disciplines is at the core of the intellectualization of the isiZulu programme at UKZN and this has culminated in the publication of two works, namely the Illustrated Glossary of Southern African Architectural Terms (2016) and A Glossary of Law Terms (2018), with an isiZulu dictionary of linguistic terms currently at an advanced stage. This section reflects on the methodological issues in the compilation of special subject field dictionaries in African languages, focusing on the impact of electronic corpora and related technologies.

5.1 Terminology development processes

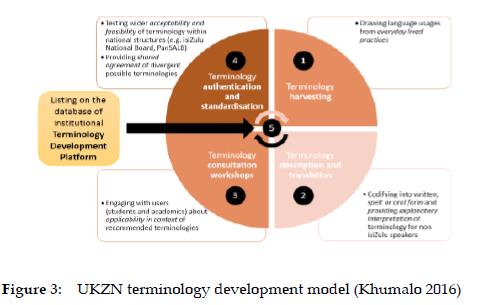

The University of KwaZulu-Natal designed and adopted a terminology development model that consists of five crucial statutory stages facilitated by the Pan South African Language Board (PanSALB) through its KwaZulu-Natal Provincial office. As captured in Fig. 3, these include:

- harvesting of existing usage terms

- description and translation of terminology that has been harvested or created

- consultation and verification with end-users about the terminology proposed

- authentication and standardization through official national (PanSALB) structures

- "finalization" of the process through the listing of terms on the terminology databases and their publication as reference books for wider institutional and national usage.

It has been observed in Khumalo (2016) that whereas the language policy at the University of KwaZulu-Natal exists as an important framework for the development of teaching materials in both English and isiZulu, the enforcement of the policy is tepid, cautious and therefore essentially not compulsory. It is in the latter sense that terminology harvesting is done voluntarily by lecturers who are committed to the principles of the language policy, and who also realize the value in making their teaching materials available to students in both languages. The harvested terms are presented as a wordlist of key terms created from a main course/module or a major reference work. It is imperative to state that for the law and architecture dictionaries lemma selection was inspired in part by the critical vocabulary in the discipline as taught at UKZN and the ability by the terminologists and language practitioners on the one hand, and the subject specialists on the other, to successfully find a term equivalent in isiZulu. In the case of the former, the discipline lecturer, who becomes the principal of the discipline terminology development process, would typically lead the process of term harvesting. This would be based on what the lecturer deems as the key English vocabulary that is crucial in the said discipline for the purposes of epistemological access. A standard requirement from the ULPDO is that the initial harvested English term list must not be less than five-hundred words. The English term list must also be accompanied by glosses or definitions that explain the scientific English term and some form of suggested isiZulu equivalent(s) by the discipline lecturer. These are meant to aid the terminologists and the language practitioners in developing and if necessary, coining a cognitively plausible term in isiZulu.

The UKZN terminology development model is largely similar to the approach presented in Figure 2 from Alberts (2017), which is prevalent in multilingual terminology projects in South Africa. In order to broaden the pool beyond lecturers, crowdsourcing was introduced as a useful strategy to harness discipline specific terminology from multiple individual sources connected to the project. These include lecturers, students, language practitioners, and the general public. The imperative to use crowdsourcing was initiated when ULPDO was developing isiZulu terminology for Information Technology and Computer Science. The two discipline experts, Dr Maria Keet and Dr Graham Barbour created a novel method (cf. http://www.meteck.org/files/commuterm/) of harnessing terms in computer science using computational resources (cf. Keet and Barbour 2014). This proved to be a useful strategy to improve the collection of terminology. It can be observed therefore that the harvesting of terms is a very important exercise as it focuses on the crucial terminology used in the discipline, and is spearheaded by experts, who are informed in the content of the discipline. The terms are then taken through the steps articulated in the model in order to arrive at the isiZulu equivalents, that are made available to the endusers using tools such as the terminology bank and the published pedagogical reference works.

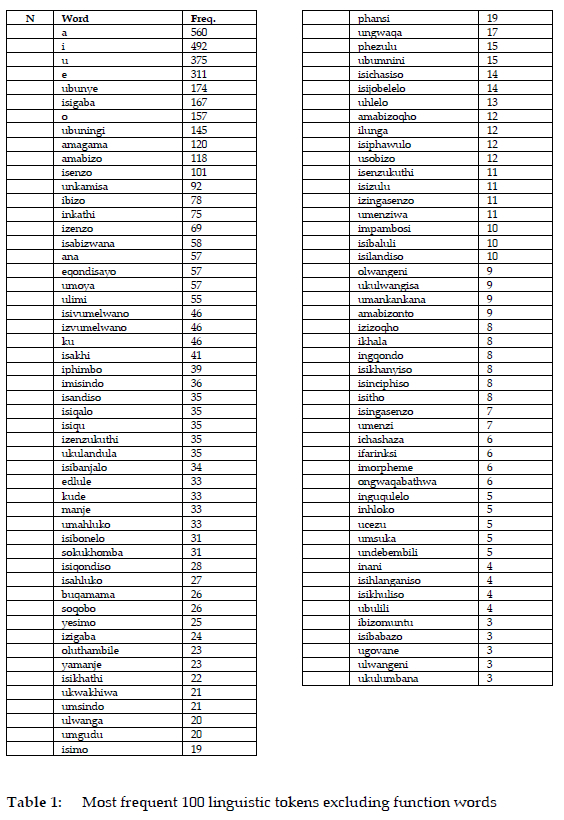

Furthermore, noting the recommendations in studies such as Taljard and De Schryver (2002), the ULPDO has tried to mitigate erratic terminology harvesting, and the effects of a clearly top down and subjective approach to terminology development, by introducing computational applications in an isiZulu dictionary of linguistic terms. This involved the use of the isiZulu National Corpus (INC) of about 1,2 million tokens as a reference corpus as well as an LSP corpus of about 100,000 tokens as a special purpose corpus. The analysis was done using WordSmith Tools, version 6 (https://lexically.net/wordsmith/version6/). It was the objective of the exercise to determine computationally, which words are typical of the linguistic domain in isiZulu and therefore stand out as preferred candidates for headword selection.

The INC as representative of language for general purposes (aka LGP) was used as a reference corpus (RC) and the LSP corpus was used as an analysis corpus (AC). The RC is a non-technical corpus while the AC is a domain-specific, technical corpus. The LSP corpus comprised of the two main isiZulu grammar textbooks Uhlelo IwesiZulu and Izikhali zabaqeqeshi nabafundi, a collection of isiZulu grammar lecture notes from academics in the School of Arts and the School of Education at UKZN, and some selected online linguistic documents in isiZulu. The aim was to semi-automatically extract terms from the LSP corpus in the subject domain of linguistics. Term extraction remains a challenge to anyone interested in domain-specific information retrieval (Jacquemin 2001; Bourigault et al. 2001). In African languages specifically, the challenges are compounded by the limited availability of specialised texts as the usage of these languages remain restricted in the specialized professional and academic domains.

Table 1 below shows a computationally generated word list (excluding the function words) of linguistic tokens extracted using WS Tools from an LSP corpus. These lemma candidates are generated faster and are presented with corresponding frequency statistical information.

Having created two types of corpora, one a general corpus (the INC) and the other an LSP corpus, it was possible to do a keyness analysis using the keyness function of WS Tools. Table 2 below shows the top 10 tokens in a list of 100 keywords after the keyness analysis.

The table shows a typical list of term candidates in the linguistics domain. The keyness tool has successfully extracted candidate terms which are key to the domain of linguistics from the corpus. The list includes the vowels a, e, i, o, u, (3, 11, 2, 38, 13); language ulimi (5); vowel unkamisa (9); singular ubunye (14), in a sentence emshweni (15); noun class isigaba (16), voiceless ongenazwi (18); noun ibizo (19) nouns amabizo (20); consonants ongwaqa (39); indicative mood eqondisayo (53); agreements izivumelwano (59); copulative isibanjalo (63) click sound ungwaqabathwa (68); cavity umgudu (80); tone iphimbo (87); subjectival senhloko (96); etc.

It was therefore evinced from this extraction process that using such a computationally aided statistical approach is faster, reliable and free from human error or bias. It was again clear that term extraction reduces the amount of noise in the list of candidate terms. However, it can be argued that mother-tongue speaker intuition remains important in complementing this vital computational method (Prinsloo 2009). Human intervention could assist in the inclusion of terms representing conceptual paradigms such as subordination, superordination and coordination relationships. For example, it is possible that the keyness search may provide 'subject concord' as a term but miss out on 'object concord'. The subject field expert can then fill in such a knowledge gap by including such a missing term.

5.2 Some comments on the metadata

The publication of works such as the Illustrated Glossary of Southern African Architectural Terms (2016) and the second A Glossary of Law Terms (2018) completes stage 5 of the UKZN terminology model and is a culmination of an organic process, which is part of the many terminology dissemination strategies. As noted earlier, the main objective in the whole terminology development process, commencing from the term harvesting of key vocabulary in the discipline by the discipline lecturer, is premised on aiding epistemological access to the subject matter. The terminologists and language practitioners are involved in a process to develop terms that are cognitively plausible and have the potential to improve the understanding of the science in question in the target language. The final product of this terminology development process is therefore aimed to be pedagogical. The two terminology dictionaries are part of the pedagogical tools aimed at improving epistemic access and help improve student success.

While the terminological processes discussed above were rigorous towards the development of scientific terms in isiZulu, the presentation of metadata in the two dictionaries appears to have lacked sufficient theoretical guidance from metalexicography. This has the effect of compromising the quality and utility value of the products. The metadata is sparse and the presentation is characteristically sketchy. Examples in Figure 4 are excerpts from A Glossary of Law Terms (2018).

In the case of PLAINTIF the headword is presented in capital bold format. The definitions are not numbered. The isiZulu equivalent headword Ummangali is presented in bold italics. There is no grammatical information. The definition is presented in italics with no usage example. The same treatment is observed with respect to the treatment of LAW OF CRIMINAL PROCEDURE. The isiZulu equivalent Inqubomthetho yamacala obugebengu/ obulelesi/egazi presents a confusing picture. In the absence of a front matter that discusses decisions that are taken in lemma selection and presentation, it is not clear to the user what the slashes stand for and how they relate to the words that come after them. Are they variants of the headword? Are they variants of the last word (as would seem to be the case in this particular lemma)? Would there have been a better way of presenting such information?

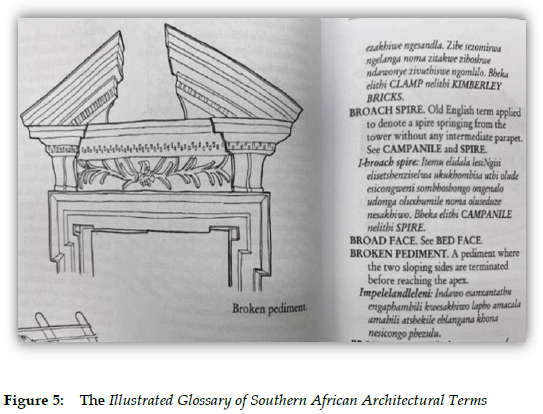

Figure 5 below is an example from the Illustrated Glossary of Southern African Architectural Terms (2016). While the presentation of the lexicographic material is the same as discussed above, this dictionary has an impressive presentation of illustrations that are key in the discipline of architecture.

Figure 5 presents the article for the lemma BROKEN PEDIMENT with isiZulu equivalent Impelelandleleni and an illustrative drawing of the broken pediment. The inclusion of the illustrations in the Illustrated Glossary of Southern African Architectural Terms was an important pedagogical consideration. However, the illustrations are only labelled in English. It is not clear whether this is a lexicographic decision or an omission on the part of the editors as there is no front matter to explain such methodological procedures.

What may be observed is that the compilation of the Illustrated Glossary of Southern African Architectural Terms (2016) and A Glossary of Law Terms (2018) used the traditional approach. Lemma selection and defining tasks were driven by the subject-field specialists. There was no recourse to an LSP corpus through the use of concordances in order to clarify or illuminate difficult terms. This naturally affected the metadata and influenced the quality of these two terminology dictionaries. Not much consideration was given to issues of dictionary structure by the subject specialists who had neither lexicographic experience nor exposure to lexicographic principles. For instance, the subject-field specialists for the Illustrated Glossary of Southern African Architectural Terms (2016) state in the introduction that:

The idea of publishing this research arose in about 1986, during the course of lectures at the University of Port Elizabeth (now Nelson Mandela University) [...]. The resultant publication (Frescura 1987) listed about 400 entries written in English, and brought together for the first time the terminology used by most of the country's language groups, with a primary focus on their historical and rural built environments. Since that time, the original manuscript has undergone extensive additions and revisions, as new research has been undertaken and additional data has become available (Frescura and Myeza 2016: xiv).

The fact that these dictionaries were built within the scope of these existing projects meant that there was very little flexibility in terms of applying the lexicographic theory that the ULPDO staff possessed, besides just converting the presentation of these data sets into a dictionary format.

The compilation of the isiZulu linguistic terms dictionary is a move away from the traditional approach. The publication of the grammar books and other teaching materials in isiZulu means that there was sufficient data to create an LSP corpus. The existence of an LSP corpus also meant that lemma selection could be done using computational approaches through the use of corpus query tools such as WS Tools. Furthermore, the existence of a bigger, IsiZulu National Corpus (the INC), meant that a lot of noise in the lemma selection could be reduced using the keyness approach as explained and demonstrated above. Defining and sense selection has also profited from the use of the concordances when the lemmas are defined. The understanding of lemma concepts does not solely depend on the subject-field specialists, but on the corpus resource as well.

The linguistic terms dictionary is intended to be printed as an A5 medium-sized pocket dictionary, that is portable and user-friendly. Currently in database form, it has just below 5 000 headwords. Size is crucially important for a reference work that is most likely to be in constant use by linguistics students. The dictionary presents lemmas in isiZulu, written in bold lowercase roman letters, followed by the IPA transcription between slashes, followed by tone marking and then the word class, the definition, usage example (optional) and finally its English equivalent. The grammatical information is important since it is part of the familiar jargon in the discipline and is useful for target user comprehension of the discipline. It is notable that such grammatical information might not be as useful in a specialized dictionary of anatomy for instance. Examples below illustrate this point.

uhlelo /úle|o/ KKP bz 11. DEFINITION. FAN grammar ibizo /lβizo/ KKP bz 5. DEFINITION. FAN noun

In addition to the above, the dictionary will have a front matter which provides a brief overview of linguistics as a discipline and a user guide. The lexicographic considerations that have been made in the conceptualization of the isiZulu linguistics terms dictionary make it a potentially more user-friendly resource compared to the other two dictionaries.

6. Conclusion

The development of terminology is an important precursor to the compilation of subject field dictionaries in African languages. The imperative to develop terminology for African languages in South Africa is driven by critical factors that include the repositioning of African indigenous languages in knowledge organization, knowledge creation, knowledge access and knowledge dissemination in (higher) education in order to improve epistemic access and student success, which hitherto has been the bane of higher education. Innovative methodologies are needed in the development, documentation, description and dissemination of terminology, taking advantage of modern advances in technology. While electronic corpus applications have great potential in that respect, as demonstrated in Taljard and De Schryver (2002), limited availability of specialized texts in African languages remains a major hinderance. This means that the benefits of specialized corpora enjoyed by lexicographers, terminologists and translators working on more advanced languages remain a pipedream for those working on African languages. While the article demonstrated that it was possible to maximize on the benefits of electronic corpora in the development of the forthcoming isiZulu dictionary of linguistic terms, it also demonstrated that largely traditional approaches were used in the compilation of the Illustrated Glossary of Southern African Architectural Terms and A Glossary of Law Terms in isiZulu. These methodological factors had implications on the quality of the products.

Acknowledgements

This article is partly produced within the research programme of the NRF SARChI Chair: Intellectualisation of African Languages, Multilingualism and Education (Grant specific unique reference number 82767), held by the second author. Both authors acknowledge that opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in any publication generated by the NRF-supported research are those of the authors, and that the NRF accepts no liability whatsoever in this regard.

References

Alberts, M. 2017. Terminology and Terminography Principles and Practice: A South African Perspective. Milnerton: McGillivray Linnegar. [ Links ]

Antia, B. and B. Ianna. 2016. Theorising Terminology Development: Frames from Language Acquisition and the Philosophy of Science. Language Matters 47(1): 61-83. [ Links ]

Appleyard, J.W. 1850. The Kafir Language. London: Wentworth Press. [ Links ]

Bergenholtz, H. and S. Nielsen. 2006. Subject-field Components as Integrated Parts of LSP Dictionaries. Terminology. International Journal of Theoretical and Applied Issues in Specialized Communication 12(2): 281-303. [ Links ]

Bergenholtz, H. and S. Tarp (Eds.). 1995. Manual of Specialised Lexicography. The Preparation of Specialised Dictionaries. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Bergenholtz, H. and S. Tarp. 2010. LSP Lexicography or Terminography? The Lexicographer's Point of View. Fuertes-Olivera, P.A. (Ed.). 2010. Specialised Dictionaries for Learners: 27-37. Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Bourigault, D. et al. 2001. Recent Advances in Computational Terminology. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Bowker, L. and J. Pearson. 2002. Working with Specialized Language: A Practical Guide to Using Corpora. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Crystal, D. 2005. A Dictionary of the English Language: An Anthology. London: Penguin. [ Links ]

Department of Arts and Culture. 2013a. Multilingual Mathematics Dictionary: Grade R-6. Pretoria: Department of Arts and Culture. [ Links ]

Department of Arts and Culture. 2013b. Multilingual Financial Terminology List. Pretoria: Department of Arts and Culture. [ Links ]

Department of Arts and Culture. 2013c. Multilingual HIV/Aids Terminology. Pretoria: Department of Arts and Culture. [ Links ]

Department of Arts and Culture. 2013d. Multilingual Parliamentary/Political Terminology. Pretoria: Department of Arts and Culture. [ Links ]

Department of Arts and Culture. 2013e. Multilingual Terminology for Information Communication Technology. Pretoria: Department of Arts and Culture. [ Links ]

Department of Arts and Culture. 2013f. Multilingual Human, Social, Economic and Management Sciences Terminology List. Pretoria: Department of Arts and Culture. [ Links ]

Department of Arts and Culture. 2013g. Multilingual Natural Sciences and Technology Term List (Nguni). Pretoria: Department of Arts and Culture. [ Links ]

Department of Arts and Culture. 2013h. Multilingual Natural Sciences and Technology Term List (SeSotho). Pretoria: Department of Arts and Culture. [ Links ]

Department of Arts and Culture. 2013i. Multilingual Natural Sciences and Technology Term List (Tshivenda-Xitsonga). Pretoria: Department of Arts and Culture. [ Links ]

Department of Arts and Culture. 2014. Use of Official Languages Act. Pretoria: Department of Arts and Culture (DAC). [ Links ]

Department of Arts and Culture. 2021. Multilingual Pharmaceutical Terminology List. Pretoria: Department of Arts and Culture (DAC). [ Links ]

Department of Education. 1997. Language in Education Policy. Pretoria: Department of Education. [ Links ]

Department of Higher Education and Training. 2002. Language Policy for Higher Education. Pretoria: Department of Higher Education and Training. [ Links ]

Deyi, S., G. Minshall and T. Tokwe. 2008. Longman Multilingual Maths Dictionary for South African Schools: English, isiXhosa, Afrikaans. Cape Town: Maskew Miller Longman. [ Links ]

Fischer, A., E. Weiss, E. Mdala and S. Tshabe. 1985. Oxford English-Xhosa Dictionary. Cape Town: Oxford University Press Southern Africa. [ Links ]

Frescura, F. and J. Myeza. 2016. Illustrated Glossary of Southern African Architectural Terms: English-isiZulu. Durban: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. 2007. On the Development of Bilingual Dictionaries in South Africa: Aspects of Dictionary Culture and Government Policy. International Journal of Lexicography 20(3): 313-327. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. 2013. Establishing and Developing a Dictionary Culture for Specialised Lexicography. Jesensek, V. (Ed.). 2013. Specialised Lexicography. Print and Digital, Specialised Dictionaries, Databases: 51-62. Lexicographica Series Maior 144. Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. 2020. Special Field and Subject Field Lexicography Contributing to Lexicography. Lexikos 30: 143-170. [ Links ]

Havránek, B. 1932. The Functions of Literary Language and its Cultivation. Hávranek, B. and M. Weingart (Eds.). 1932. A Prague School Reader on Esthetics, Literary Structure and Style: 32-84. Prague: Melantrich. [ Links ]

Jacquemin, C. 2001. Spotting and Discovering Terms through Natural Language Processing. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Kaschula, R.H. and D. Nkomo. 2019. Intellectualisation of African Languages: Past, Present and Future. Wolff, H.E. (Ed.). 2019. The Cambridge Handbook of African Linguistics: 601-622. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Keet, M. and G. Barbour. 2014. Commuterm. Available at: http://www.meteck.org/files/commuterm.

Khumalo, L. 2016. Disrupting Language Hegemony: Intellectualizing African Languages. Samuel, M., R. Dhunpath and N. Amin (Eds.). 2016. Disrupting Higher Education Curriculum: Undoing Cognitive Damage: 247-263. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. [ Links ]

Kilgarriff, A. 2012. Review of Pedro A. Fuertes-Olivera and Henning Bergenholtz (Eds.). e-Lexi-cography: The Internet, Digital Initiatives and Lexicography. Kernerman Dictionary News 20: 26-29.

Lukasik, M. 2016. Specialized Pedagogical Lexicography: A Work in Progress. Polilog: Studia Neo-filologiczne 6: 211-226. [ Links ]

Mahlalela-Thusi, B. and K. Heugh. 2002. Unravelling some of the Historical Threads of Mother-tongue Development and Use during the First Period of Bantu Education (1955-1975): New Developments and Research. Perspectives in Education 20(1): 241-257. [ Links ]

Mbude-Shale, N., Z. Wababa and K. Welman. 2008. Illustrated Multilingual Science and Technology Dictionary / Isichazi-magama sezeNzululwazi neTeknoloji Ngeelwimi Ezininzi. Cape Town: New Africa Books. [ Links ]

Mesthrie, R. 2008. Necessary versus Sufficient Conditions for Using New Languages in South African Higher Education: A Linguistic Appraisal. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 29(4): 325-340. [ Links ]

Nkomo, D. 2018. Dictionaries and Language Policy. Fuertes-Olivera, P.A. (Ed.). 2018. The Routledge Handbook of Lexicography: 152-165. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Nkomo, D. 2019. Theoretical and Practical Reflections on Specialized Lexicography in African Languages. Lexikos 29: 96-124. [ Links ]

Nkosi, N.R. and G.N. Msomi. 1992. Izikhali zabaqeqeshi nabafundi. Pietermaritzburg: Reachout Publishers. [ Links ]

Nyembezi, S. 1982. Uhlelo lwesiZulu. Fourth edition. Pietermaritzburg: Shuter and Shooter. [ Links ]

Open Education Resource Term Bank (OERTB). Available at: http://oertb.tlterm.com/.

PanSALB. 2000. Annual Report. Pretoria: Pan South African Language Board (PanSALB).

PRAESA. 2008. Illustrated Multilingual Science and Technology Dictionary - Intermediate Phase (English-Afrikaans-Xhosa). Cape Town: New Africa Education. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, D.J. 2009. The Role of Corpora in Future Dictionaries. Nielsen, S. and S. Tarp. (Eds.). 2009. Lexicography in the 21st Century: In Honour of Henning Bergenholtz: 181-206. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, D.J. 2014. The Utilization of Bilingual Corpora for the Creation of Bilingual Dictionaries. Gouws, R.H., U. Heid, W. Schweickard and H. Wiegand (Eds.). 2014. Dictionaries. An International Encyclopedia of Lexicography. Supplementary Volume: Recent Developments with Focus on Electronic and Computational Lexicography: 1344-1356. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter Mouton. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, M.W., M. Alberts and N. Mollenta. 2015. Legal Terminology: Criminal Law, Procedure and Evidence /Regsterminologie: Straf-, Strafproses- en Bewysreg. Cape Town: Juta. [ Links ]

Scott, M. 2007. WordSmith Tools version 6. Available at https: //lexically.net/wordsmith/version6/.

Sibayan, B.P. 1991. The Intellectualisation of Filipino. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 88: 69-82. [ Links ]

Taljard, E. and G.-M. de Schryver. 2002. Semi-automatic Term Extraction for the African Languages, with Special Reference to Northern Sotho. Lexikos 12: 44-74. [ Links ]

Tarp, S. 2012. Specialised Lexicography: 20 Years in Slow Motion. Ibérica. Journal of the European Association of Languages for Specific Purposes 24: 117-128. [ Links ]

Wababa, Z., K. Welman and K. Press (Eds.). 2010. Isichazi-magama seziBalo Sezikolo saseCambridge. Cape Town: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Zondi, K. 2018. A Glossary of Law Terms: English-isiZulu. Durban: University of KwaZulu Natal Press. [ Links ]