Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Lexikos

On-line version ISSN 2224-0039

Print version ISSN 1684-4904

Lexikos vol.32 spe Stellenbosch 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.5788/32-2-1699

ARTICLES

Critical Lexicography at Work: Reflections and Proposals for Eliminating Gender Bias in General Dictionaries of Spanish

Kritiese leksikografie aan die werk: Gedagtes oor en voor-stelle vir die uitskakeling van gendervooroordeel in algemene Spaanse woor-deboeke

Pedro A. Fuertes-OliveraI; Sven TarpII

IInternational Centre for Lexicography, University of Valladolid (Spain) and Department of Afrikaans and Dutch, University of Stellenbosch, South Africa (pedro@emp.uva.es)

IICentre for Lexicographical Studies, Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, China, Centre for Lexicography, University of Aarhus, Denmark and Department of Afrikaans and Dutch, University of Stellenbosch, South Africa (st@cc.au.dk)

ABSTRACT

This study highlights the fact that dictionaries are ideological texts that are very influential, because millions of people regard them as sources of authority. It shows that existing general dictionaries of Spanish are so gender-biased that they contribute to the upholding of unfair situations, for example, by making women invisible and maintaining gendered traditions based on male-centred power and ideology. In order to avoid such an unfair situation, we introduce several new ideas regarding the question of language and gender. We also show how this can be put into practice in a dictionary portal that we are constructing at the time of writing this article. Therefore, this article offers several specific solutions with the aim of making women lexicographically visible, promoting the use of inclusive language in public and private discourse and eliminating gendered practices.

Keywords: inclusive language, dictionary, Spanish, ideology, profession NOUNS

OPSOMMING

in hierdie artikel word daar beklemtoon dat woordeboeke ideologiese tekste is wat 'n groot invloed uitoefen, aangesien miljoene mense woordeboeke as gesaghebbende bronne beskou. Daar word aangetoon dat bestaande algemene Spaanse woordeboeke so bevooroordeeld is t.o.v. gender dat hulle 'n bydrae lewer tot die aanmoediging van onbillike situasies, byvoorbeeld, deur vroue onsigbaar te maak en deur gendertradisies, wat gebaseer is op manlikgesentreerde mag en ideologie, te handhaaf. Om so 'n onbillike situasie te vermy, stel ons verskeie nuwe idees rondom die taal- en genderkwessie voor. Ons toon ook aan hoe dit in 'n woordeboekportaal, wat tydens die skryf van hierdie artikel deur ons saamgestel word, toegepas kan word. Hierdie artikel bied dus verskeie spesifieke oplossings aan met die doel om vroue leksikografies sigbaar te maak, om die gebruik van inklusiewe taal in die openbare en private diskoers te bevorder en om genderpraktyke uit te skakel.

Sleutelwoorde: inklusiewe taal, woordeboek, spaans, ideologie, beroeps-NAAMWOORDE

1. Introduction

Scholars typically analyse the linguistic relationship between gender and sexuality under the tenets of well-established linguistics approaches, such as conversation analysis, corpus-based and corpus-driven analyses, (critical) discourse studies, ethnography of communication, multimodal discourse studies, language ideological analysis, stylistics, and so on (Holmes and Meyerhoff 2003). In her review of the Handbook of Language and Gender, for instance, Pichler (2005: 637) indicates that most of the publications in the Handbook have abandoned the traditional sociolinguistic conceptualisation of gender as an independent social variable composed of two components, one male and one female. instead, most authors "appear to take a broadly constructionist approach to gender, viewing gender as being accomplished in interaction rather than as a fixed category". This view has led to different types of analysis, for example, those focusing on socio-pragmatics view the categories of 'sex' and 'gender' as complex and intertwined and have argued that "differences between women's and men's use of language were best accounted for by attending to societal power relations" (Holmes and King 2017: 121). A large body of research supports the above conclusion (e.g. Tannen 1990, Fuertes-Olivera 1992, 2007, Velasco-Sacristán and Fuertes-Olivera 2006). Holmes and King (2017) indicate that research into the relationship between gender and language suggests that

- power (see Keating 2009) is dynamically constructed and exercised; in other words, different participants may exercise power in different ways and, therefore, "power is constantly being constructed, negotiated, maintained and re-asserted, as people interact" (Holmes and King 2017: 122);

- power is systemic, that is, the norms and expectations of the most powerful groups are taken for granted in most situations and imitated (see Wodak 1999, Holmes 2005);

- power is a central component of leadership, as research on workplace interactions has shown (see Holmes 2006, Mullany 2007, Baxter 2010).

This paper adds to the above body of research by analysing the role lexicographers have played in maintaining some of the abovementioned imbalance, and it will show that lexicographers can and must adopt a different approach with the aim of making language dictionaries inclusive. We first describe the theoretical framework of the dictionary as an ideological text, and present the concepts of power and ideology and their influence in existing general dictionaries of Spanish. After formulating the research questions we will address in this article, we will then go on to describe some existing general dictionaries of Spanish, discussing the significance of the findings for gender and lexicographic theory and dictionary practice. We will then present the Diccionarios Valladolid-UVa, a brand-new dictionary project that aims to use inclusive language, eliminate gender bias and respond to demands from current Spanish society, which, first of all, is asking for the feminisation of official texts and, second, is fighting against male-dominant approaches to day-to-day life.

Regarding the first issue, the Vice-president of the 2018 Spanish socialist government officially asked the Royal Spanish Academy, which is the editor of the Diccionario de la Lengua Española (DLE), to take a leading role in two main tasks. Firstly, it should prepare a set of guidelines for recommending the use of inclusive language in Spanish official texts, such as the Spanish Constitution. Secondly, it should adapt the DLE to inclusive language guidelines, for example, by including the feminine forms of profession nouns and avoiding the use of male generic terms.

It seems that the Vice-president's request aimed at advancing the fight against the Spanish machista society. On the one hand, the new texts and dictionary articles will make the feminist agenda more visible, by indicating that the political debate must also be the object of gender considerations. On the other hand, this request will highlight the role language plays in the construction of society. Both objectives will promote the de-genderisation of Spanish society, that is, Spanish entrenched gender stereotypes should be eliminated as soon as possible. Unfortunately, the response of the Royal Spanish Academy (RAE) has been so tame that it has only accepted the inclusion of some feminine words, for example, the word presidenta ('female president') and some doubles (e.g. presidentes y presidentas ('male and female presidents') in the texts, but with no real change in its DLE (Informe sobre el buen uso del lenguaje inclusivo en nuestra carta magna 2020).

We do not know the rationale for the response given to the Vice-president. This does not, however, concur with a lot of research, especially - and to name just a few examples - those championed by feminist linguists (e.g. Mills and Mullany 2011) on language and gender, by Halliday (1978) on the social interpretation of language meaning, and by Van Dijk (1984, 1987) on the connection between ideology and language. These, and many more authors, have defended the social role of language, which should be analysed not only in isolation, that is, taking into consideration its formal properties, but also in terms of its context, for example, by focusing on language as text and discourse. This is what we will do in the following sections.

2. The dictionary as ideological text

Dictionaries can be described in various ways, and one of them uses a textual approach. Dubois and Dubois (1971) and Frawley (1989), among others, have analysed the conceptualisation of dictionaries as text by focusing on the information structure of the lexicographic text. Fuertes-Olivera and Nielsen (2018: 17), for instance, observe that the textual structure of dictionaries is initially connected with their functions(s). In this regard, dictionaries compiled to help users searching for knowledge contain texts such as systematic introductions that provide their potential users with a description of the knowledge structure of a particular domain, for example, accounting (Fuertes-Olivera 2009, Niño Amo and Fuertes-Olivera 2017). They also indicate that, essentially, dictionaries are information tools that have been compiled to offer assistance in certain types of situation in which they are consulted. This includes communicative situations in which interlocutors engage in communicative acts and need help to successfully complete the tasks; for example, when authors write texts in their native language and when translators translate texts into or from a foreign language. Another type of situation, often referred to as cognitive, is when a person needs to acquire knowledge about something in general or specific knowledge about a particular matter. This could be when students consult dictionaries in order to widen their knowledge basis prior to lectures and when translators make a consultation in order to acquire knowledge about a subject field as a prerequisite for properly understanding source texts. Dictionaries consulted in these situations are collections of different examples of text (Bergenholtz, Tarp and Wiegand 1999: 1763) which contain varieties of data that support more than one lexicographic function, that is, to provide certain types of assistance to certain types of users in certain types of use situations (see Fuertes-Olivera 2018, Fuertes-Olivera and Tarp 2014).

Secondly, dictionaries are usually divided into sections that often represent different text types. These sections can be use-related if they contain data that help people to use the dictionary properly and to its fullest extent, such as user guides, while other sections are function-related, containing data that provide a service insofar as they satisfy lexicographically relevant needs, such as wordlists and dictionary articles. This division into sections is particularly evident in print dictionaries, which can be described as special types of books that are divided into a number of chapters; however, online dictionaries may also contain similar sections, which are in effect different web pages under specific dictionary websites. Each sectional text type found in dictionaries can be a potential source or target text. For instance, the print version of the DLE (2014) contains information sections (e.g. the name of academicians, including those in charge of the DLE), use-related sections, such as an explanation of the main changes introduced in the 23rd edition of the dictionary, and function-related sections, for example, each dictionary article.

Use-related sections contain data sets that may be termed generic, in the sense that many of these give general guidance about dictionaries and can be reused in other dictionaries. However, data sets in function-related sections are less likely to be generic, in that they are directly dependent on aspects such as the domains selected for consideration and the dictionary functions. This means that function-related sections in, say, specialised dictionaries, are likely to be more difficult to decode, transfer and encode than those in general-language dictionaries (Fuertes-Olivera and Nielsen 2018).

Since dictionary articles can be regarded as texts, it is appropriate to look briefly at relevant text levels. Two levels stand out: headwords, that is, texts that are made up of headlines that introduce their (text) topics, and co-texts, such as 'definition', 'sentence example', 'equivalent', 'lexicographic note', etc., each of which describes the meaning, usage and possible restriction of each headword. In rudimentary dictionaries, dictionary articles have very few elements; for example, some specialised bilingual dictionaries have only headwords and equivalents. However, modern lexicography prioritises user needs in communicative and cognitive situations and, therefore, dictionary articles are now likely to contain more than two textual elements in order to provide help that can satisfy user needs (see Fuertes-Olivera 2018, Fuertes-Olivera and Tarp 2014: 48-57, Fuertes-Olivera and Nielsen 2018, Nielsen 2018). This is the case in all the general language dictionaries that will be analysed below.

Dictionary sections, then, can be subjected to different types of analysis. For instance, they can be studied in terms of the external social factors relating to them. This is, basically, what critical discourse analysis has done with many different text types. We will follow suit and will analyse function-related dictionary texts under the tenets of 'critical lexicography', a concept developed by Kachru (1995) to explain that "[l]exicography and its products, dictionaries, are never value-free, apolitical or asocial. Instead, they are subject to ideology, power and politics" (Chen 2019: 362).

Critical lexicography can be connected with the feminist movement, e.g. De Beauvoir (1949). For the purpose of this article, we can enumerate some changes that show the influence of this movement in English dictionaries: the creation of lemmas such as chair, chairperson, police officer, etc., which replace the generic uses of chairman, policeman, and so on; the new uses and definitions of human race and humankind replacing 'generic man'; the use of notes and comments against sexist and racist meanings; see, for example, man in Lexico; the use of 'singular they' instead of 'generic he'; and the publication of the Feminist Dictionary by Kramarae and Treichler (1985) (see also Baron 1986, Fuertes-Olivera 1992, Hidalgo Tenorio 2000). More recently, critical lexicography has morphed into several varieties, Critical Lexicographical Discourse Studies (CLDS) representing one of them. This

rests on the assumption that lexicography is a recontextualizing practice and that the dictionary, as a recontextualized discourse, is closely associated with other social/discursive practices and a site where ideological and social struggle take place. As a recontextualized discourse, the dictionary does not simply replicate its source or just 'transport' meaning; rather, it creates meaning; it rewrites and represents things in new ways (Chen 2015).

Under the tenets of CLDS, we will show that existing lexicographic practices have embedded their lexicographic data in their social context, have taken a political stance explicitly and have not offered their users ways of emancipating themselves from traditional forms of domination (Wodak and Meyer 2015).

The following analysis and critique of general dictionaries of Spanish is based on the concepts of power and ideology. Power is exercised by dominant groups with the aim of exerting "domination, coercion and control of subordinate groups" (Simpson and Mayr 2010: 2). Ideology sustains the interests of groups by promoting a "coherent and relatively stable set of beliefs and values" (Wodak and Meyer 2015: 30). Both concepts are relevant because ideology is primarily transmitted and enacted through language and language also contributes to exercising and maintaining power. Furthermore, dictionaries describe languages in terms of lexicographers' particular ways of seeing the world and their social contexts. Hence, dictionaries are powerful tools for transmitting power and ideology. Very often, Spaniards are 'informed' that something is as it is because this is what the DLE says. In other words, the dictionary of the Royal Spanish Academy is acclaimed as the source of authority, although it was conceptualised more than 300 years ago and has not incorporated most of the social changes that have occurred during this time. Some researchers - e.g. Nissen (1986), Fuertes-Olivera (1992), Forgas Berdet (1996), Calero Vaquera (2010), Rodríguez Barcia (2012), and Cabeza Pereiro and Rodríguez Barcia (2013) - have argued that the DLE should be totally updated; for example, by eliminating any trace of sexism in its structures. One possible adaptation is connected with the lemmatisation policy of dictionaries, as we will show below.

For reasons of space, we will analyse some function-related texts that clearly show how existing general dictionaries of Spanish influence the maintenance of a male-dominant society in Spain and the Spanish-speaking world. We will analyse in particular three research questions:

1. To what extent are women visible in general dictionaries of Spanish?

2. If not, which function-related texts are contributing most to the (in)visibility of women?

3. Are there any proposals we should advocate for increasing the visibility of women, and thus for eliminating the gender bias in general dictionaries of Spanish?

3. Methodology

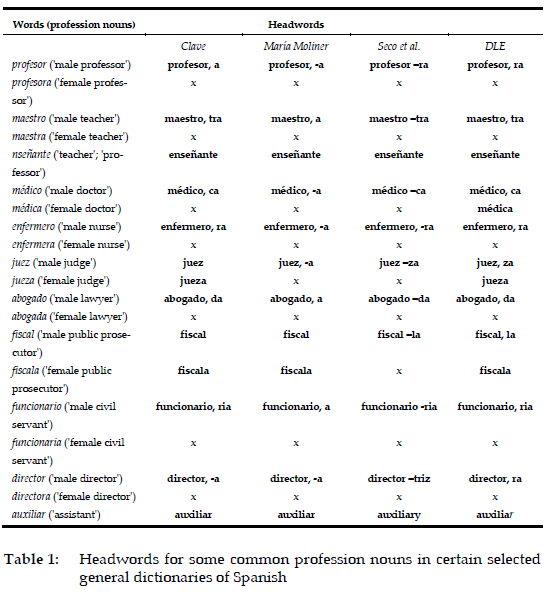

Bosque and Barrios Rodríguez (2018) show that the Spanish lexicographic market is dominated by four printed general language dictionaries, all of which have published new editions in the last 15 years (two of them also have retro-digitised versions): Diccionario de uso del español actual (Clave 2004; this was retro-digitised in 2010), Diccionario de uso del español (María Moliner 2007), Diccionario del español actual (Seco, Andrés and Ramos 2011), and Diccionario de la lengua española (DLE 2014; this was also retro-digitised in 2014).

Due to limitations of space, we will investigate the lexicographic treatment of 'profession nouns', that is, nouns referring to male and female professionals. Spanish official statistics show that there are 10.8 million men and 9.1 million women working in Spain in 2020, and that they are evenly distributed in socio-economic sectors such as teaching, health, justice and the civil service (Ministerio de Trabajo 2020). If there is a 50% chance of finding either a woman or a man working in these sectors, it can be hypothesised that existing dictionaries, especially those that have recently published new editions, should offer a balanced analysis of some of the common nouns used for referring to them in these four socioeconomic sectors:

- 'teaching': we will analyse the Spanish words profesor, profesora ('professor'), maestro', maestra ('teacher'), and enseñante ('teacher');

- 'health': we will analyse the Spanish words médico, médica ('doctor'), enfermero, and enfermera ('nurse');

- 'justice': we will analyse the Spanish words juez, jueza ('judge'), abogado, abogada ('lawyer'), fiscal, and fiscala ('public prosecutor'); and

- 'civil service': we will analyse the Spanish words funcionario, funcionaria ('civil servant'), director, directora ('director') and auxiliar ('assistant').

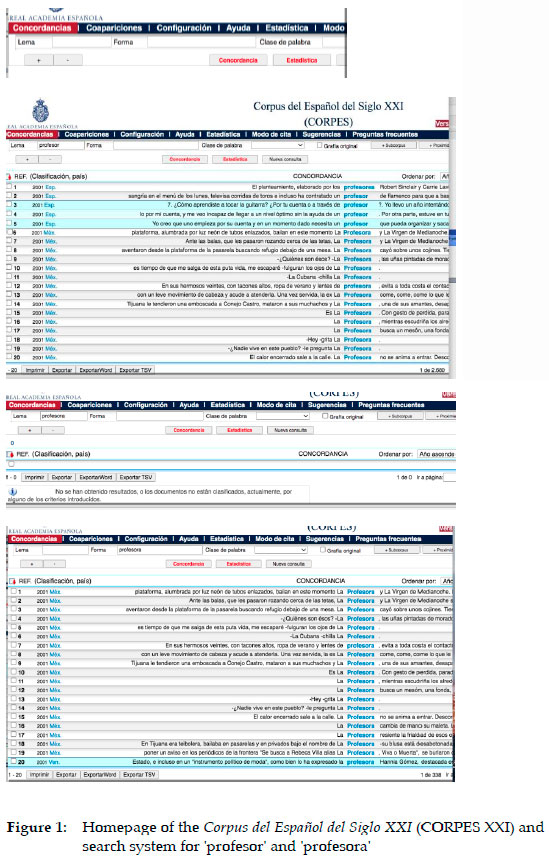

These words have been selected for three reasons. Firstly, they are very common words [e.g. they frequently appear in the Corpus de referencia del español actual (CREA) and the Corpus del español del siglo XXI (CORPES XXI)]. For instance, a search for the Spanish words profesor and profesora in CORPES XXI retrieves more than 45,000 and 5,000 hits, respectively. This difference is determined by the policy of lemmatisation used in the corpus, which is the same as the one used in general dictionaries of Spanish, as we will show below (e.g. Table 1 and Discussion).

Secondly, as common and very easy-to-find words, their lexicographic treatment will easily show whether or not power and ideology are still dominant in mainstream Spanish culture, as we must insist that Spaniards typically resort to the authority of dictionaries, especially that of the Royal Spanish Academy, when they are discussing public matters.

Thirdly, the selected words, which, to the best of our knowledge, have never been analysed from a sociolinguistic perspective, are not associated with relevant male or female features. In other words, there is no objective reason for treating them differently from a lexicographic point of view. If their lexicographic consideration reproduces a bias, it may mean that these general dictionaries of Spanish continue playing a role in the upholding of a gendered society.

Our analysis will focus on two function-related texts: headwords and definitions. Headwords - also called lemmas, dictionary words, or dictionary entries - are typically subjected to a process called lemmatisation. This allows lexicographers to group together the inflected forms of a word. For instance, the forms eat, eats, ate, eating and eaten are lemmatised under eat, which is the canonical form one may look up in a dictionary, as it represents the whole inflection paradigm.

The concept of definition has been the subject of scrutiny in different fields, e.g. Philosophy, Logic, Law, Linguistics, Terminology and Lexicography. For the purpose of this paper, definitions describe the meaning of the headword, that is, the "set of conditions which must be satisfied by a lexical unit in order to denote the extra-linguistic reality/ies which correspond(s) to each of its senses" (Fuertes-Olivera and Arribas Baño 2008: 69). Hence, they refer to the "specific set of data that explains the meaning of a lemma and which is clearly addressed to the lemma" (Nielsen 2011: 202).

4. Data and results

Headwords are usually selected depending on etymology, grammar, such as part-of-speech, frequency and traditions which are taken for granted. By way of example, the DLE selects two Spanish headwords for the Spanish word alma, one deriving from the Latin anima ('soul') and one from the Hebrew almá ('virgin'), and two headwords for the Spanish word cantar, one for a noun ('poem') and one for a verb ('sing'). In general, selections based on etymology and grammar have little, if any, trace of power and ideology.

Lemma selection based on taken-for-granted traditions and frequency, however, may be strongly influenced by power and ideology. The use of 'frequency' for selecting headwords has been gaining momentum since 1987, that is, after Sinclair and his team published the Collins Cobuild English Language Dictionary (Sinclair 1987), which paved the way for using corpora in dictionary-related activities. Although some lexicographers have insisted on the benefits of a corpus approach to lexicography (Hanks 2012), its use has not been able to avoid the influence of power and ideology in the selection process. For instance, almost all corpus-based dictionaries rely exclusively or to a large extent on written texts; in other words, the prioritisation of the written language over spoken language is ideological in nature, as favouring langue over parole is a rhetoric of standardisation which serves the "transmutation of standard language into mythical national languages" (Fairclough 1989: 22). The abovemen-tioned general dictionaries of Spanish have not selected their headwords on frequency counts. Instead, they have continued using taken-for-granted traditions, three of which are relevant for this article: (a) lexicographers mainly (sometimes exclusively) select the lemma list from standard sources, typically from literary works and newspapers; (b) lexicographers standardise their lemma list by assuming that their generalisations include women and men and that these are socially and politically neutral; (c) space constraints demand the use of 'dictionarese', that is, typical dictionary conventions.

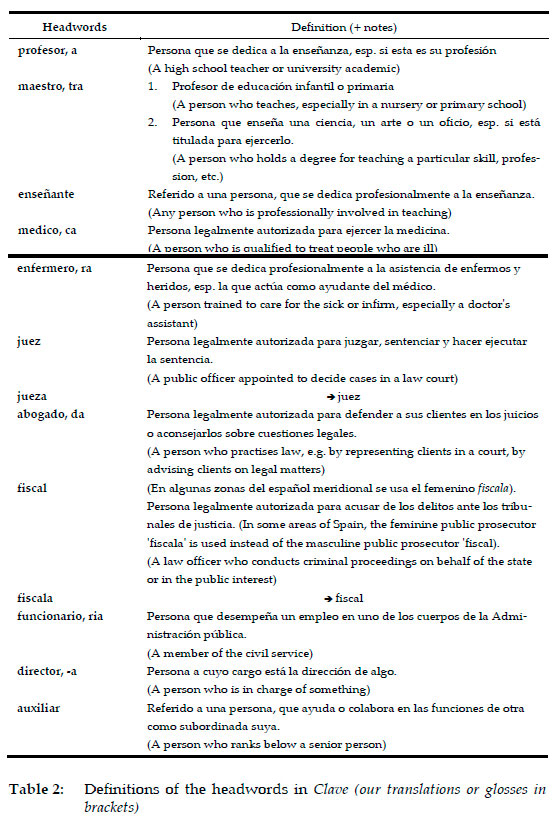

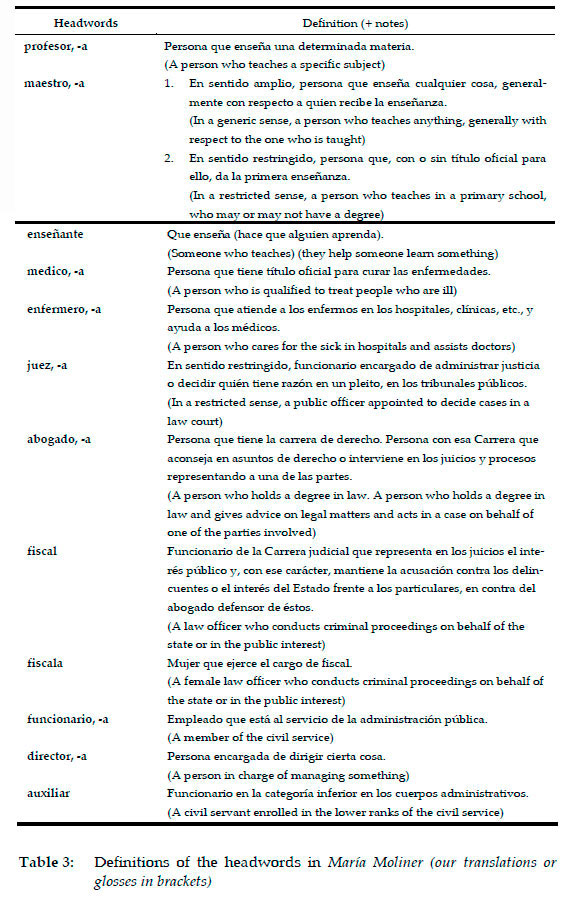

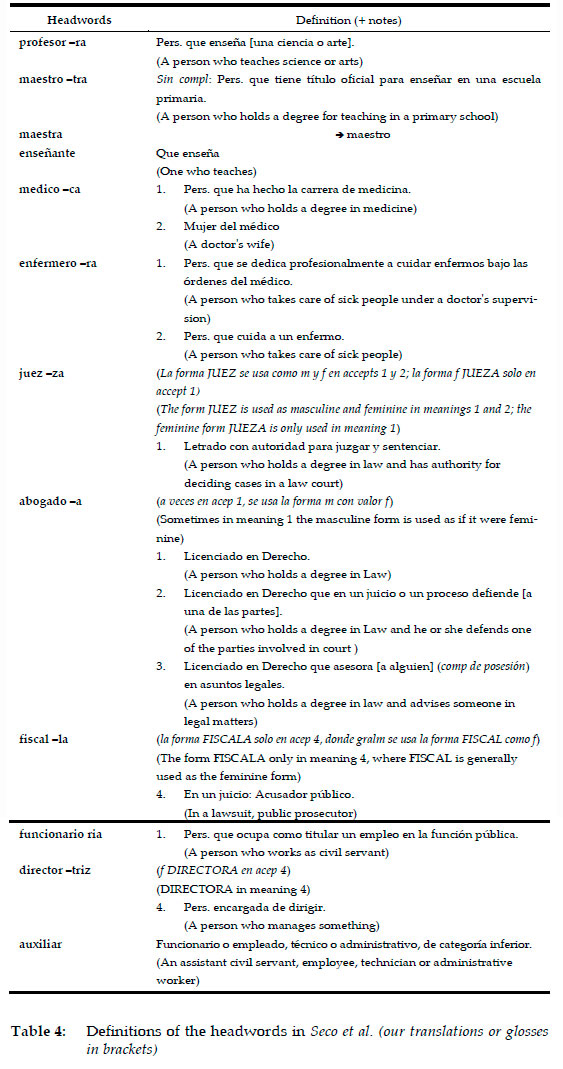

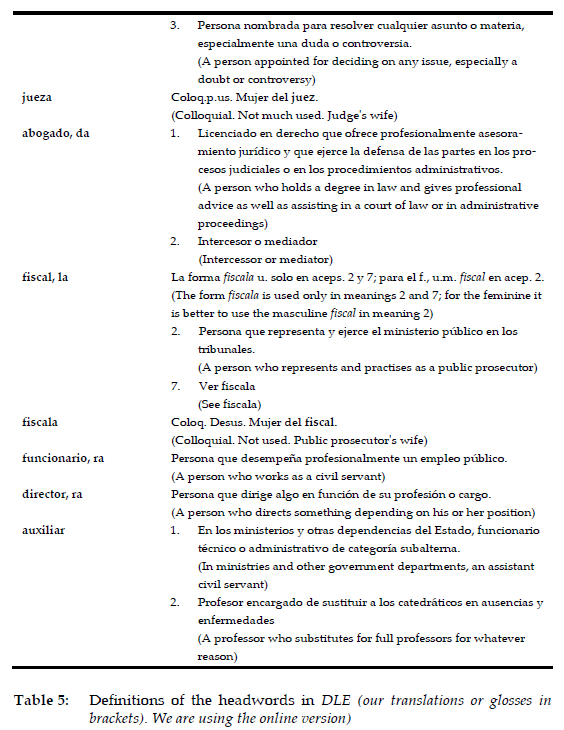

One of these conventions is the use of headwords such as profesor, a. This headword does not exist in natural Spanish (Table 1). It shows that lexicographers have taken for granted that a headword such as profesor, a is the lemma for the Spanish words profesor ('male teacher'), profesora ('female teacher'), profesores ('male teachers'), and profesoras ('female teachers'). In other words, headwords such as profesor, a; profesor -a; profesor -ra; and profesor, ra (Table 1) are lexicographic conventions, that is, dictionarese, which do not exist in running texts. This convention seems to rest on the idea that female nouns derive from male nouns by adding a final a (which sometimes happens but not always) and that users must know the different formulae employed in each dictionary, as the four dictionaries under analysis show (they are the following: profesor, a; profesor -a; profesor -ra; and profesor, ra). In some cases, they must know that they may have to add or eliminate one or more letters in order to create an authentic feminine word from the headword. For instance, a user looking up the headword profesor, ra (DLE) must eliminate one r to create the feminine word profesora. This explains why, in Tables 1 to 5, words such as profesora ('female teacher'), maestra ('female teacher'), médica ('female doctor'), enfermera ('female nurse'), jueza ('female judge'), abogada ('female lawyer'), fiscala ('female public prosecutor'), funcionaria ('female civil servant') and directora ('female director') are either absent as headwords or, when present, are described as the wife of a man who may be a doctor, a judge, a civil prosecutor, and so on.

Regarding definitions, Rundell (2015: 314) indicates that, in the printed era, a focus on economy led to definitions "which achieve conciseness (and aspire to precision) through the use of standard formulae ('the act of X-ing), 'characterised by Y', and so on) and through a recursive strategy". These strategies have costs that are passed on to the user, who has to learn these conventions in order to understand what the dictionary is saying (e.g. the previously mentioned Spanish headword profesor, a). He adds that in the last 30 years publishers, and especially those in the UK, have addressed this issue by developing more open defining styles. These aim to offer enough information for understanding the definition without knowledge of 'dictionarese', that is, the typical dictionary conventions such as the use of a recursive strategy, always assuming that

a lexicographical definition (...) does not identify a meaning independently existing in actual usage and discovered there by the lexicographer: it is deliberately constructed and allocated by the lexicographer on the basis of materials selected for study, and its allocation will depend on the viewpoint the lexicographer has chosen to adopt. (Harris and Hutton 2007: 78)

and

A definition can only be as effective as the context allows it to be, and the context includes the situation of the person seeking to understand the meaning. The notion of a definition adequate to all occasions and all demands is a semantic ignis fatuus. (Harris and Hutton 2007: 49)

Tables 2 to 5 show the definitions used for each of the headwords included in the dictionaries under analysis. We will include only the definitions of the nouns referring to the women and men employed in the abovementioned socioeconomic sectors. We assume that if these are evenly distributed, both women and men will be clearly identified. Some of the definitions are accompanied by lexicographic notes that are relevant for the topic under examination in this article.

Tables 1 to 5 show three main results that will be discussed below. Firstly, Spanish dictionaries do not use natural words as headwords. Secondly, they lemmatise conventions that are typically formed by using the male form as the base form of the convention. Finally, women are either not specifically mentioned or, when mentioned, are usually treated as 'the wife of a professional man'.

5. Discussion and lexicographic solutions

From a qualitative point of view, Tables 1 to 5 show that women are mostly absent from general dictionaries of Spanish, and that when they are included, they are not presented fairly. Firstly, the use of headwords such as profesor, ra eliminates the figure of women from dictionaries. Although millions of Spaniards agree and take for granted that dictionaries are sources of authority, only a handful of them have received some training in 'dictionarese', and therefore will easily assume, say, that ra is a kind of symbol for the Spanish word profesora. For many Spaniards, 'dictionarese' such as profesor, a and profesor, -ra are meaningless because they are conventions that must be learned, e.g. at school. Unfortunately, these conventions are not taught at school. Hence, such headwords greatly contribute to the invisibility of women. Nothing can be more dangerous for the public image of a person than to make them invisible.

Secondly, dictionarese forms such as professor -ra are converted into 'masculine' forms straightaway. For instance, in CORPES XXI the search system of this corpus allows users to search for lemma and form (Figure 1). The Spanish word profesor is assumed to be the lemma or headword, whereas profesora is a form. Any search with profesor will retrieve all the tokens of the headword profesor, ra [e.g. profesor, profesora, profesores, and profesoras], whereas any search with the token profesora will only retrieve hits of profesora and profesoras as forms. In sum, this mechanism helps explain that the Spanish word profesor is 9 times more frequent in CORPES XXI than its feminine counterpart profesora: 2,680 hits against 338 (Figure 1):

Thirdly, Spanish lexicographers are making women invisible subconsciously, for example, by creating software that transforms headwords such as profesor, ra into masculine forms (profesor) (see the search mechanism in CORPES XXI in Figure 1), and by creating male and well-differentiated headwords for referring to powerful males. For instance, for more than a thousand years Spaniards have used the feminine word modista for referring to a person whose job is making clothes, typically women's dresses. As soon as men gained status in the profession, Spanish lexicographers created the masculine headword modisto, which corresponds to the actual word modisto ('couturier'). Furthermore, they defined it as 'a man who created women's dresses and fashion'. Why have Spanish lexicographers not created the headwords modista, o or modista, to for this new word is an open question, as many Spanish lexicographers usually claim that masculine words typically end in o in the same way that they assume that feminine words typically end in a (see headwords in Table 1, most of which have a final a as a kind of symbol for the feminine word). And, if dictionaries such as the DLE now lemmatise modista ('dressmaker') and modisto ('couturier') as headwords, why have they avoided the same lexicographic process with the Spanish feminine words profesora, maestra, enfermera, and so on?

To the best of our knowledge, nobody has answered this question, as shown below.

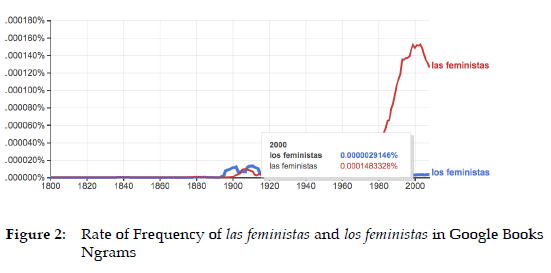

Fourthly, Spanish lexicographers use both rules that exist only in formal grammars as well as taken-for-granted traditions. These rules do not always work in language, especially in informal face-to-face encounters. Fuertes-Olivera (1992), for instance, has shown that Spaniards use social gender with some nouns (e.g. those relating to a profession). Social gender implies the use of male or female generics depending on users' social expectations and conventions. For instance, Spanish mainstream newspapers have recently used and continue using headlines such as Las feministas se manifiestan contra la sentencia de la Manada instead of Los feministas se manifiestan contra la sentencia de la Manada [the former is feminine and the latter masculine, and the headlines refer to the uproar caused by the rape of a young woman at the hands of a group of young men, identified as 'la Manada' ('the herd')]. Spanish newspapers use feminine generics (Las feministas) because Spanish society associates 'feminist' with women. This also explains why the generic expression las feministas is 42 times more used than los feministas in Google Books Ngram Viewer (Figure 2; see Pechenick, Danforth and Dodds (2015) for an analysis of some of the limitations of the Google Books Corpus). Such a figure would be impossible if the rules explaining the use of masculine words or expressions as generics were real. Instead, they are constructions based on the influence of power and ideology:

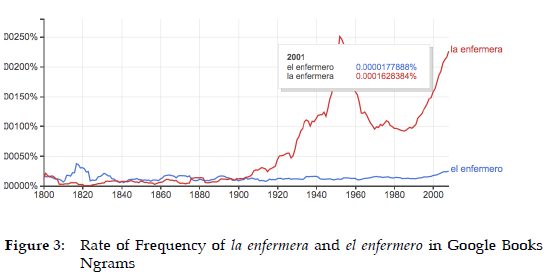

Fifthly, Spanish lexicographers immediately created the headword modisto ('couturier') for referring to a man influencing fashion and making women's dresses. Why, then, have they not created the headword enfermera ('female nurse') if this word tends to be used 90% of the times in which Spaniards refer to the person trained to care for the sick or infirm, especially in hospitals (Figure 3):

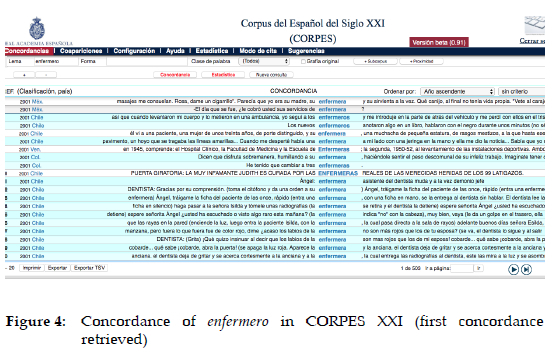

Furthermore, searching the Spanish word enfermera in the lemma search system of CORPES XXI retrieves no hits. However, searching enfermero ('male nurse') in this search system retrieves more than 10,000 hits, most of which are for the word enfermera, as shown in the first concordance (Figure 4):

Finally, lexicographers sometimes include female nouns and notes referring to them. The inclusion of headwords such as jueza, médica, cross-references (e.g. > fiscal) and notes such as 'the form juez is also used for feminine' reinforce the male dominance seen in general dictionaries of Spanish. Some of the above dictionaries define jueza or médica as a 'judge or doctor's wife'. This use was common in informal Spanish 40 or 50 years ago. At that time, most people who trained to care for the sick or infirm were female nurses (enfermera), and, following the same logic of the headwords jueza and médica, Spanish lexicographers should have included a definition of enfermero as 'a female nurse's husband'. Such a definition was never included, although it was also used in informal spoken Spanish. The only explanation for this is the influence of power and ideology in dictionary making; that is to say, lexicographers assume the ideology of the dominant group (males) and act accordingly (a) by creating lemmas for referring to a man entering a new profession (without doing the same in the case of a woman), or (b) by referring to the marital status of a woman but not of a man.

To combat this, we believe that proscription notes, that is, lexicographic notes recommending uses and meanings, must be included (see the section below).

Briefly, general dictionaries of Spanish are examples of the influence of the power and ideology that reinforce male dominance, contributing to male leadership and maintaining the norms and expectations of the most powerful group, by, for instance, explaining that masculine terms are generic and include feminine ones. To finish with such gendered practices, we have created a new type of dictionaries: the Diccionarios Valladolid-UVa. This is an integrated dictionary portal. Fuertes-Olivera (2016) defines it as:

a reference tool whose Dictionary Writing System is equipped with disruptive technologies. These allow lexicographers to store as much data as possible and users to retrieve only the data they need in specific use situations. Its articles are prepared by the same team with the basic aim of helping human and/or machine users to meet their needs in a quick and easy way. They contain both lexicographically prepared data and open linked data with lexicographic value. The lexicographic data is reusable, subject to a constant process of updating and can be used in conjunction with other tools, e.g. assistants.

The above definition shows that our integrated dictionary portal is a tool, that is, a utility and information device conceived for consultation with the genuine purpose of meeting users' specific information needs in different extra-lexicographic situations. This concept fully concurs with the idea of lexicography advocated by proponents of the Function Theory of Lexicography (Bergenholtz and Tarp 2003, Fuertes-Olivera and Tarp 2014, Tarp 2008). In practical terms, this means that we envisage an integrated dictionary portal as a repository of lexicographic data dealing with language, facts and things. Hence, this portal aims at offering reference solutions regardless of their being deemed semantic, encyclopaedic, linguistic, onomastic or whatever. At the time of writing this paper, the portal contains around 80,000 definitions of general Spanish headwords, approximately 20,000 definitions of general English headwords and some 15,000 definitions of English and Spanish accounting terms. We plan to publish several online general dictionaries of Spanish, various online bilingual Spanish-English/English-Spanish dictionaries and several online specialised dictionaries. For this paper, we will refer to decisions concerned with the use of inclusive language in Spanish. For reasons of space, we will limit our analysis to the words profesora and profesor. These will illustrate the general philosophy of the tool, focusing on offering a de-gendered approach to dictionary making with the aim of eliminating power and ideology from lexicographic practice, offering a fair perspective of women and men, and recording and promoting social changes.

All lexicographic data are extracted from the Internet. We have used crawlers to find out which words Spaniards typically search for, and we are using Google minitexts, that is, the three lines Google shows when searching for a particular word, as sources for understanding and recording the meaning, use, function, etc., of a particular headword (Tarp and Fuertes-Olivera 2016). The data extracted is subjected to different types of analysis, and of relevance here is that concerned with the use of inclusive language in dictionary making. To the best of our knowledge, no scholar has so far addressed this issue in an integrated way. Existing publications only describe the phenomenon of feminisation in dictionaries in current use and do not explain how lexicographers must eliminate gender bias in dictionaries. Baider et al. (2007), for instance, investigate the definitions in entries for the nouns homme 'man' and femme 'woman' in the online EuroWordNet dictionary. Their comparison reveals that "andro-centrism still prevails in this online dictionary, since most examples given in the entries refer to males" (Westveer, Sleeman and Aboh 2018: 376).

Similarly, Darmestádter (2011) compares the 8th and 9th editions of the dictionary of the French Academy with the aim of analysing possible differences between both editions concerning "including the feminisation of profession nouns", and observes that the French Academy "still disfavours the use of feminine forms, prescribing the use of compound forms with femme (e.g. femme médecin 'female doctor') when no feminine form exists" (Westveer et al. 2018: 376).

Epple (2000) investigates diachronic changes in the presence of female-denoting nouns in different editions of bilingual dictionaries covering American English, French, German and Spanish, and finds "considerable progress in the visibility of women among the different editions of the dictionaries with respect to the inclusion of female-denoting nouns". However, as she shows in the examples in the dictionaries' entries of animate nouns, "women are often not included" (Westveer et al. 2018: 377).

Our first decision has been to eliminate headwords such as professor, ra from dictionary making. In the Diccionarios Valladolid-UVa all headwords are real words, that is, they are presented as they are used. Hence, the 20 words covered in Tables 1 to 5 are lemmatised as profesora, profesor, maestro, maestra, enseñante, médico, médica, enfermero, enfermera, juez, jueza, abogado, abogada, fiscal, fiscala, funcionario, funcionaria, director, directora and auxiliar.

Secondly, all headwords are grammatically described with their inflexions and the articles with which they typically occur. For instance, the headwords profesora and profesor are grammatically described as: una profesora; la profesora; unas profesoras and las profesoras (In Spanish, these articles are typically associated with feminine nouns); and un profesor; el profesor; unos profesores and los profesores (In Spanish, these articles are typically associated with masculine nouns). This allows us to eliminate concepts such as masculine, feminine, common, etc., which are usually used in general dictionaries of Spanish. This decision has two implications: (a) we take a broadly constructionist approach to gender, and view it as being accomplished in interaction rather than as a fixed category; (b) we claim that generics can be constructed with both, say, las profesoras and los profesores. For instance, for headwords such as enfermera our dictionaries record specific and generic definitions, (see below).

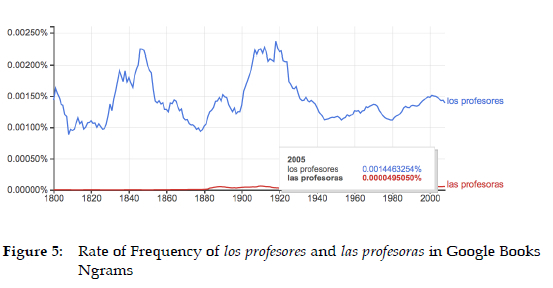

Thirdly, the definitions of profession nouns include specific and generic explanations. By way of example, the Spanish word profesor is defined as (1) hombre que se dedica profesionalmente a la enseñanza, es decir, que está especializado en una materia, disciplina académica, ciencia o arte determinadas y enseña a otras personas ('man who teaches professionally') and (2) persona (hombre o mujer) que se dedica profesionalmente a la enseñanza, es decir, que está especializada en una materia, disciplina académica, ciencia o arte determinadas y enseña a otras personas ('person, i.e. man or woman, who teaches professionally'). The generic definition is recorded under the headword that occurs typically in Spanish. For instance, in Google Books Ngram Viewer, we observe that los profesores is around 30 times more frequent than las profesoras (Figure 5), and therefore we include the generic definition under the headword profesor. However, for the word feminista ('feminist') the generic meaning is under the headword feminista described with the articles una, la, unas, and las (Figure 2 shows that las feministas is 42 times more frequent than los feministas):

Fourthly, all definitions use the same style and wording with the exception of the Spanish words mujer ('woman'), hombre ('man') and persona ('person'), which are used at the beginning of the definition of profession nouns for referring, respectively, to a woman, a man, or a person (see the definitions of the word profesor above).

Fifthly, each meaning is reinforced with synonyms, antonyms, notes, collocations and examples that are balanced and ideologically neutral. For instance, for the specific meaning of the headword maestro we include the synonym profesor ('male professor') and for the generic meaning of maestro we include the synonyms profesora ('female professor') and profesor ('male professor'). Then we include notes such as 'this meaning is outdated and should be avoided', referring to the informal meaning of fiscala, as 'a male public prosecutor's wife'. Especially relevant is the use of proscription notes. Bergenholtz (2003) has claimed that dictionaries must record the forms and uses found in their sources and, when needed, they should include recommendations. Thus, for the Spanish meaning of the headword médica as 'a male doctor's wife' we have included the note no recomendamos este uso porque hace referencia a un tipo de sociedad que, o bien ya no existe o está desapareciendo por ser discriminatoria para la mujer (we do not recommend this usage because it refers to a type of society that either does not exist or it is disappearing as it discriminates against women). There are several types of proscription notes, of which those concerned with the use of inclusive language are of relevance for these articles. For instance, for the generic definition of the headword profesor, we have also included the synonym profesores y profesoras ('male and female professors') and a note indicating that this synonym is typically found in public discourse with the aim of making women visible and eliminating gender bias from Spanish society.

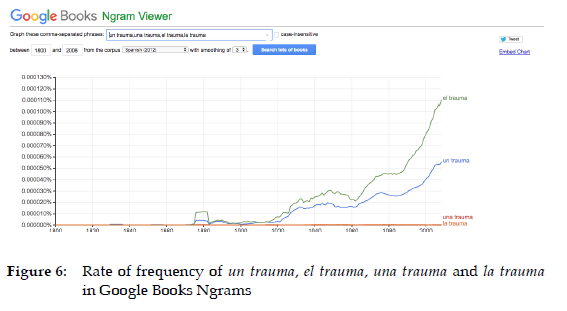

Finally, when we find, say, a male headword whose female counterpart is difficult to spot, for example, because it is a nonce formation, we always search for its female counterpart reproducing typical Spanish patterns of word formation. If, say, we have found the Spanish word trauma (informal Spanish for 'male and female orthopaedic surgeon'), then we lemmatise it by attaching suitable inflections and articles. In such situations, we have two headwords, one with the articles un, el, unos and los, and another with the articles una, la, unas and las. The former refers to a male orthopaedic surgeon whereas the latter describes a female one. Both headwords are lexicographically treated in the same way. This means that each of them will be described specifically (i.e. referring to a male or female orthopaedic surgeon), and one of them will have a generic meaning (i.e. referring to both male and female orthopaedic surgeons). For deciding which will be defined generically, we basically resort to Google Books Ngram Viewer. For instance, Figure 6 shows that un trauma and el trauma are much more common than una trauma and la trauma. Hence, the generic meaning is included in the headword with the articles un, el, uno and los:

6. Conclusions

This study has offered a new perspective on language and gender by focusing on gendered practices in general dictionaries of Spanish. We have hypothesised that the lexicographic treatment of very common Spanish words will show to what extent much acclaimed and commonly used dictionaries deal with the question of inclusive language, especially at a time when a Spanish Vice-president has officially requested the elimination of any gender bias, and unfair power and ideology, from official texts and from the DLE, the Royal Spanish Academy's dictionary, always regarded as a source of authority. Our hypothesis is based on our assumption that we can observe the possible existence of gendered practices by analysing profession nouns referring to female and male professionals who work in socioeconomic sectors where both are evenly distributed.

Our analysis has focused on two types of function-related texts: headwords and definitions, some of which also include lexicographic notes that are relevant for this study. Regarding our first research question, we have shown that existing general dictionaries of Spanish make women invisible because they use headwords that do not contemplate the existence of women and they use definitions that reproduce the gender bias existing in Spanish speaking societies.

Regarding our second research questions, we have shown that Spanish dictionaries make sometimes women visible, although treating them unfairly, especially by referring to them as 'the wife of a professional man'. This practice does not exist when the new lemma should be coined from an existing female one, e.g. 'modista' or when it could also refer to the husband of a professional woman. In other words, the dictionaries under analysis, which are the most influential and most used in the Spanish-speaking world, are examples of the influence of the power and ideology that reinforce male dominance, contribute to male leadership and maintain the norms and expectations of the most powerful group. We have made our case that the elimination of such dangerous practices in reference works demands a new approach to dictionary making.

This new approach, in line with our third research question, is based on the concept of the dictionary as both a text and a tool, which must be as balanced as possible and must aim at offering a fair view of society in general and of its members in particular. To achieve this purpose, we have advocated several lexicographic practices, all of which are exemplified with our practice in making the Diccionarios Valladolid-UVa. This new type of online dictionaries has eliminated 'dictionarese', has lemmatised profession nouns of women and men on an equal footing, has created balanced and equal definitions, and has introduced new ideas and practices for promoting the use of inclusive language in Spanish. In sum, we

- use real words as lemmas, e.g. 'profesor' and 'profesora' are two lemmas;

- craft identical definitions for 'hombre' (man), 'mujer' (woman) or 'persona' (person), each of which refers to a specific or generic profession noun;

- use proscription notes and other lexicographic devices for emphasizing the use of inclusive language

- eliminate any trace of ideology and power in the lexicographic treatment of all lemmas; and

- base all our lexicographic decisions on data extracted from the internet and analyzed in their sociological contexts.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to two anonymous reviewers and to Dr. Elsabé Taljard for their comments on a previous draft of this paper.

References

A. Dictionaries

Clave. 2004. Diccionario de uso del español actual. Maldonado, María Concepción (Dir.). Seventh edition. Madrid: SM. Accessed on 22 August 2021. http://clave.smdiccionarios.com/app.php.

DLE. 2014. Diccionario de la Lengua Española. Real Academia Española de la Lengua y Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Española. 23rd edition. Madrid: Espasa. Accessed on 22 August 2021. https://dle.rae.es/. [ Links ]

EuroWordNet. Accessed on 22 August 2021. http://projects.illc.uva.nl/EuroWordNet/.

Kramarae, C and Treichler, P. 1985. A Feminist Dictionary. London: Pandora. Lexico by Oxford. Accessed on 22 August 2021. https://www.lexico.com/. [ Links ]

Moliner, María. 2007. Diccionario de uso del español. Third edition. Madrid: Gredos. [ Links ]

Seco, Manuel, Olimpia Andrés and Gabino Ramos. 2011. Diccionario del español actual. 2nd edition. Madrid: Aguilar. [ Links ]

Sinclair, John (Ed.). 1987. Collins Cobuild English Language Dictionary. London: Collins ELT. [ Links ]

B. Other literature

Baider, F., É. Jacquey and A. Liang. 2007. La place du genre dans les bases de données multilingues: le cas d'EuroWordNet. Nouvelles Questions Feministes 26(3): 57-69. [ Links ]

Baron, D. 1986. Grammar and Gender. New Haven: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Baxter, J. 2010. The Language of Female Leadership. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Bergenholtz, H. 2003. User-oriented Understanding of Descriptive, Proscriptive and Prescriptive Lexicography. Lexikos 13: 65-80. [ Links ]

Bergenholtz, H. and S. Tarp. 2003. Two Opposing Theories: On H.E. Wiegand's Recent Discovery of Lexicographic Functions. Hermes, Journal of Linguistics 31: 171-196. [ Links ]

Bergenholtz, H., S. Tarp and H.E. Wiegand. 1999. Datendistributionsstrukturen, Makro- und Mikrostrukturen in neueren Fachwörterbüchern. Hoffmann, L., H. Kalverkämper, H.E. Wiegand, together with Christian Galinski and Werner Hüllen (Eds.). 1999. Fachsprachen. Ein internationales Handbuch zur Fachsprachenforschung und Terminologiewissenschaft/Languages for Special Purposes. An International Handbook of Special-Language and Terminology Research, Bd./Vol. 2: 1762-1832. Berlin: De Gruyter. [ Links ]

Bosque, I. and M.A. Barrios Rodríguez. 2018. Spanish Lexicography in the Internet Era. Fuertes-Olivera, Pedro A. (Ed.). 2018. The Routledge Handbook of Lexicography: 636-660. London/New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Cabeza Pereiro, M.C. and S. Rodríguez Barcia. 2013. Aspectos ideológicos, gramaticales y léxicos del sexismo lingüístico. Estudios Filológicos 52: 7-27. [ Links ]

Calero Vaquera, M.L. 2010. Ideología y discurso lingüístico: La Etnografía como subdisciplina de la glotopolítica. Boletín de Filología 45(2): 31-48. [ Links ]

Chen, W.G. 2015. Bilingual Lexicography and Recontextualization: A Case Study of Illustrative Examples in a New English-Chinese Dictionary. Australian Journal of Linguistics 35(4): 311-333. [ Links ]

Chen, W.G. 2019. Towards a Discourse Approach to Critical Lexicography. International Journal of Lexicography 32(3): 362-388. [ Links ]

Corpus de Referencia del español actual. Accessed on 22 August 2021. http://corpus.rae.es/creanet.html.

Corpus del Español del Siglo XXI. Accessed on 22 August 2021. http://web.frl.es/CORPES/view/inicioExterno.view.

Darmestädter, C. 2011. Modernité et modernisation du Dictionnaire de l'Académie française: quelles transformations de la huitième à la neuvième édition? Études de linguistique appliquée 163(3): 285-306. [ Links ]

De Beauvoir, S. 1949. Le Deuxième Sexe. Les faits et les mythes. Volume 1. L'expérience vécue. Volume 2. Paris: Gallimard. [ Links ]

Dubois, J and C. Dubois. 1971. Introduction à la lexicographie: le dictionnaire. Paris: Larousse. [ Links ]

Epple, B. 2000. Sexismus in Wörterbüchern. Heid, U., S. Evert, E. Lehmann and C. Rohrer (Eds.). 2000. Proceedings of the Ninth EURALEX International Congress, EURALEX 2000, Stuttgart, Germany, August 8th-12th, 2000: 739-754.

Fairclough, N. 1989. Language and Power. London: Longman. [ Links ]

Forgas Berdet, E. 1996. Lengua, sociedad y diccionario: La ideología. Forgas Berdet, E. (Ed.). 1996. Léxico y diccionarios: 71-90. Tarragona: Universitat Rovira i Virgili. [ Links ]

Frawley, W. 1989. The Dictionary as Text. International Journal of Lexicography 2(3): 231-248. [ Links ]

Fuertes Olivera, Pedro A. 1992. Mujer, lenguaje y sociedad. Los estereotipos de género en inglés y en español. Madrid: Ayuntamiento de Alcalá de Henares. [ Links ]

Fuertes-Olivera, Pedro A. 2007. A Corpus-based View of Lexical Gender in Written Business English. English for Specific Purposes 26(2): 219-234. [ Links ]

Fuertes-Olivera, Pedro A. 2016. European Lexicography in the Era of the Internet: Present Situations and Future Trends. Plenary talk, Beijing, 2 December 2016. Talk sponsored by the Commercial Press and the Chinese Association of Lexicography.

Fuertes-Olivera, Pedro A. (Ed.). 2018. The Routledge Handbook of Lexicography. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Fuertes-Olivera, Pedro A. and A. Arribas-Baño. 2008. Pedagogical Specialised Lexicography. The Representation of Meaning in English and Spanish Business Dictionaries. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Fuertes-Olivera, Pedro A. and S. Nielsen. 2018. Translating English Specialized Dictionary Articles into Danish and Spanish: Some Reflections. 3L: Language, Linguistics, Literature 24(3): 15-25. [ Links ]

Fuertes-Olivera, Pedro A. and S. Tarp. 2014. Theory and Practice of Specialised Online Dictionaries. Lexicography versus Terminography. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter. [ Links ]

Google Books Ngram Viewer. Accessed on 3 February 2021. https: //books.google.com/ngrams.

Halliday, M.A.K. 1978. Language as Social Semiotic: The Social Interpretation of Language and Meaning. London: Arnold. [ Links ]

Hanks, P. 2012. The Corpus Revolution in Lexicography. International Journal of Lexicography 25(4): 398-436. [ Links ]

Harris, R. and C. Hutton. 2007. Definition in Theory and Practice. Language, Lexicography and the Law. London: Continuum. [ Links ]

Hidalgo Tenorio, E. 2000. Gender, Sex and Stereotyping in the Collins COBUILD English Language Dictionary. Australian Journal of Linguistics 20(2): 211-230. [ Links ]

Holmes, J. 2005. Power and Discourse at Work: Is Gender Relevant? Lazar, Michelle M. (Ed.). 2005. Feminist Critical Discourse Analysis: 31-60. London: Palgrave. [ Links ]

Holmes, J. 2006. Gendered Talk at Work. Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Holmes, J. and B.W. King. 2017. Gender and Sociopragmatics. Barron, Anne, Yueguo Gu and Gerard Steen (Eds.). 2017. The Routledge Handbook of Pragmatics: 121-138. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Holmes, J. and M. Meyerhoff (Eds.). 2003. The Handbook of Language and Gender. Oxford: Blackwell. Informe sobre el buen uso del lenguaje inclusivo en nuestra carta magna. 16 de enero de 2020 (January, 16, 2020). Accessed on 3 February 2021. https://www.rae.es/noticias/el-pleno-de-la-rae-aprueba-el-informe-sobre-el-buen-uso-del-lenguaje-inclusivo-en-nuestra.

Kachru, B.B. 1995. Afterword: Directions and Challenges. Kachru, Braj B. and Henry Kahane (Eds.). 1995. Cultures, Ideologies and the Dictionary. Studies in Honour of Ladislav Zgusta: 417-424. Tubingen: Max Niemeyer. [ Links ]

Keating, E. 2009. Power and Pragmatics. Language and Linguistics Compass 3(4): 996-1009. [ Links ]

Mills, S. and L. Mullany. 2011. Language, Gender and Feminism: Theory, Methodology and Practice. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Ministerio de Trabajo. 2020. Accessed on 3 June 2020. https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/categoria.htm?c=Estadistica_P&cid=1254735976595.

Mullany, L.J. 2007. Gendered Discourse in the Professional Workplace. Basingstoke: Palgrave Mac-millan. [ Links ]

Nielsen, S. 2011. Function- and User-related Definitions in Online Dictionaries. Kartasova, F.I. (Ed.). 2011. Ivanovskaya leksikograficheskaya shkola: traditsii i innovatsii: 197-219. Ivanovo: Ivanovo State University. [ Links ]

Nielsen, S. 2018. LSP Lexicography and Typology of Specialized Dictionaries. Humbley, John, Gerhard Budin and Christer Laurén (Eds.). 2018. Languages for Special Purposes: An International Handbook: 71-95. Berlin/Boston: Mouton de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Nissen, U.K. 1986. Sex and Gender Specifications in Spanish. Journal of Pragmatics 10(6): 725-738. [ Links ]

Pechenick, E.A., C.M. Danforth and P.S. Dodds. 2015. Characterizing the Google Books Corpus: Strong Limits to Inferences of Socio-Cultural and Linguistic Evolution. PLoS ONE 10(10). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0137041. [ Links ]

Pichler, P. 2005. Review of J. Holmes and M. Meyerhoff (Eds.). The Handbook of Language and Gender. Language in Society 34(4): 633-638.

Rodríguez Barcia, S. 2012. El análisis ideológico del discurso lexicográfico: una propuesta metodológica aplicada a diccionarios monolingües del español. Verba. Anuario Galego de Filoloxía 39: 135-159. [ Links ]

Rundell, M. 2015. From Print to Digital: Implications for Dictionary Policy and Lexicographic Conventions. Lexikos 25: 301-322. [ Links ]

Simpson, P. and A. Mayr. 2010. Language and Power: A Resource Book for Students. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Tannen, D. 1990. You Just Don't Understand: Women and Men in Conversation. New York: Morrow. [ Links ]

Tarp, S. 2008. Lexicography in the Borderland between Knowledge and Non-knowledge: General Lexicographical Theory with Particular Focus on Learner's Lexicography. Tubingen: Max Niemeyer. [ Links ]

Tarp, S. and Pedro A. Fuertes-Olivera. 2016. Advantages and Disadvantages in the Use of Internet as a Corpus: The Case of the Online Dictionaries of Spanish Valladolid-UVa. Lexikos 26: 273-295. [ Links ]

Van Dijk, T.A. 1984. Prejudice in Discourse. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Van Dijk, T.A. 1987. Communicating Racism: Ethnic Prejudice in Thought and Talk. Sage: Newbury Park, CA.

Velasco-Sacristán, M. and Pedro A. Fuertes-Olivera. 2006. Towards a Critical Cognitive-Pragmatic Approach to Gender Metaphors in Advertising English. Journal of Pragmatics 38(11): 1982-2002. [ Links ]

Westveer, T., P. Sleeman and E.O. Aboh. 2018. Discriminating Dictionaries? Feminine Forms of Profession Nouns in Dictionaries of French and German. International Journal of Lexicography 31(4): 371-393. [ Links ]

Wodak, R. 1999. Critical Discourse Analysis at the End of the 20th Century. Research on Language and Social Interaction 32(1-2): 185-193. [ Links ]

Wodak, R. and M. Meyer. 2015. Critical Discourse Studies: History, Agenda, Theory and Methodology. Wodak, R. and Michael Meyer (Eds.). 2015. Methods of Critical Discourse Studies: 18-50. Third edition. London: Sage. [ Links ]