Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Lexikos

versión On-line ISSN 2224-0039

versión impresa ISSN 1684-4904

Lexikos vol.32 Stellenbosch 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.5788/32-1-1681

ARTICLES

Improving the Compilation of English-Chinese Children's Dictionaries: A Children's Cognitive Perspective

Verbetering van die samestelling van Engels-Chinese kinder-WOOrdeboeke: Die kognitiewe perspektief van 'n kind

Dan ZhaoI; Hai XuII

ISchool of Foreign Studies, Guangdong University of Finance and Economics, Guangzhou, P.R. China (ddanzhao@163.com)

IICentre for Linguistics and Applied Linguistics, Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, Guangzhou, P.R. China (Corresponding Author, xuhai1101@gdufs.edu.cn)

ABSTRACT

Children's dictionaries have existed for more than one thousand years in China, and play an important role in children's learning. However, many of those produced in China are deficient in the selection of the wordlist, in exemplification, and in definition. This paper aims at improving the compilation of English-Chinese children's dictionaries (ECCDs) from a children's cognitive perspective. Children's dictionaries should not only be an abridgement or simplification of dictionaries for adults, because their target user group is immature, uninformed and untrained children. Informed by some innovations in current English learner's dictionaries, this paper proposes that the making of ECCDs needs to be improved in the following aspects. Firstly, instead of lexicographers' intuition, the selection of headwords should be based on an English corpus for Chinese children. Secondly, the words used in examples should be congruent with children's limited cognitive and learning abilities. Thirdly, a multifaceted method of explanation should be provided in order to assist children in understanding the meaning of headwords.

Keywords: english-chinese children's dictionaries, user focus, children's corpus, headwords, children's cognitive ability, illustrations, examples

OPSOOMING

Kinderwoordeboeke bestaan reeds meer as 'n duisend jaar in China, en speel 'n belangrike rol in die leerproses van kinders. Baie van dié wat in China saamgestel word, is egter ontoereikend in die keuse van die woordelys, in die gebruik van voorbeelde en in die definisie. in hierdie artikel word gepoog om die samestelling van Engels-Chinese kinderwoordeboeke (ECKWe) vanuit die kognitiewe perspektief van 'n kind te verbeter. Kinderwoordeboeke behoort nie net 'n beknopte uitgawe of vereenvoudiging van woorde-boeke vir volwassenes te wees nie, want hul teikengebruikersgroep is onvolwasse, oningeligte en onopgeleide kinders. Aangespoor deur sommige vernuwings in huidige Engelse aanleerderswoor-deboeke, word daar in hierdie artikel voorgestel dat die samestelling van ECKWe ten opsigte van die volgende aspekte verbeter moet word. Eerstens behoort die seleksie van trefwoorde op 'n Engelse korpus vir Chinese kinders en nie op leksikografiese intuïsie gebaseer te word nie. Tweedens behoort die woorde wat in voorbeelde gebruik word, in ooreenstemming met kinders se beperkte kog-nitiewe en aanleervermoëns te wees. Derdens behoort 'n veelvlakkige metode vir verduideliking verskaf te word om sodoende kinders te help om die betekenis van trefwoorde te kan begryp.

Sleutelwoorde: engels-chinese kinderwoordeboeke, gebruikersfokus, KINDERKORPUS, TREFWOORDE, KINDERS SE KOGNITIEWE VERMOËNS, ILLUSTRASIES, VOORBEELDE

1. Introduction

Children's dictionaries not only have a long history in China but also play a vital role in children's learning. They are intended for the edification of children. However, children's lexicography has received less attention than adult-oriented lexicography.

Dictionaries that are designed explicitly for children have a shorter word-list consisting of the most "important" words of the language, excluding regionalisms, archaisms, slang words, etc. They also use different techniques for the explanation of meaning, including, for instance the use of illustrative examples without definitions. They are often interesting for the metalexicographer, but oddly enough they have never been the object of serious research (Béjoint 2000: 40).

For many languages, there are few or even no children's dictionaries. For example, in Slovenia, no dictionary has been designed for the school population (Roz-man 2008); and in Greece, few children's dictionaries have been published (Gavrilidou et al. 2008). One of the reasons why many publishers hesitate to allocate resources to the development of school dictionaries is the relatively poor sales and corresponding profits coming from this category of dictionaries (Tarp and Ruiz Miyares 2013). Although the situation with lexicographic publishing has changed remarkably over the last decade, with digital resources becoming almost ubiquitous for adults, paper dictionaries continue to be used in schools because children are forbidden to use electronic products in school (at least in China). Nevertheless, revenues from school dictionaries are still not significant for publishers. When at home, children tend to use digital resources instead of print dictionaries.

Children's dictionaries were found to have some apparent deficiencies (Turrini et al. 2000, Verburg 2006, Rozman 2008, Gavrilidou et al. 2008, Potgieter 2012, Kosch 2013, Sene Mongaba, B. 2016). In children's dictionaries, the list of head-words is often selected at random (Verburg 2006). Definitions are too difficult for this target audience (Rozman 2008; see also De Schryver and Prinsloo 2011 on definitions in Van Dale dictionaries). Lexicographic and typographical codes are incomprehensible to children (Rozman 2008). Some of the children's dictionaries are only a revised and simplified version of the existing unabridged dictionaries, such as monolingual children's dictionaries in Italy (Turini et al. 2000) and in Greece (Gavrilidou et al. 2008), and a bilingual Afrikaans school dictionary in South Africa (Potgieter 2012). Example sentences supply the user with little or no contextual guidance (Potgieter 2012). Above all, most of children's dictionaries fail to take into due consideration the abilities and interest of young users. As a result, they can hardly meet the specific needs of the intended target users and are often more of an obstacle than an aid.

The making of monolingual dictionaries for children thrived in China. The oldest extant monolingual school dictionary in China is Ji Jiu Pian (急就篇), The Instant Primer) which was compiled by Shi You (史游) in the Western Han Dynasty in the first century BC. There were some other monolingual school dictionaries published before and after it, such as Cang Jie Pian (仓颉篇) in the Qin Dynasty between 221 and 207 BC, Fan Jiang Pian (《 凡将篇 》) in the Western Han Dynasty about 150 BC, Xun Zuan Pian (《 训纂篇 》) in the Western Han Dynasty between 53 and 18 BC, and Pang Xi Pian (《 滂喜篇 》) in the Eastern Han dynasty in the first century AD. However, these children's dictionaries except for Ji Jiu Pian were lost. In 1953, Xinhua Zidian(《 新华字典》),Xinhua Dictionary of Chinese Characters), the first modern Chinese monolingual dictionary for children, was published. It is the most influential and authoritative Chinese children's dictionary, and has the highest circulation of any dictionary in the world. It has been revised many times and reprinted more than two hundred times. The latest (i.e., 12th) edition was published in August, 2020.

By comparison, the number of bilingual dictionaries for Chinese-speaking children, mainly English-Chinese Children's Dictionaries (ECCDs), are few. For example, the Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press, one of the top publishers in China, has published 47 English-Chinese learner's dictionaries, but of these only four are bilingual dictionaries for children.

ECCDs can be divided into three main types, based on the cognitive abilities of children at different ages: dictionaries for preschool children (2-6 years old), those for elementary school children (6-12 years old), and those for children in junior high school (12-16 years old). However, our investigation into the main ECCDs shows that some current ECCDs have no clear target group of users. Some dictionaries include 'children' in their titles but do not indicate for which age bracket they are intended. An analysis of these dictionaries shows the following problems: Firstly, the number of headwords varies widely among ECCDs for the same age group. For example, Zhongguo Xiaoxuesheng Yingyu Xuexi Cidian (An English-Chinese Dictionary for Primary School Learners in China) contains approximately 4,000 headwords while Xinbian Xiaoxuesheng Yinghan Cidian (The Brand-New English-Chinese Dictionary for Primary School Students) only comprises approximately 1,500 headwords. Secondly, some words used in examples are beyond children's knowledge. For instance, in Xiaoxuesheng Yinghan Cidian (An English-Chinese Dictionary for Primary School Students), there is an example under the headword also: She's a talented singer and also a fine actress. But talented is neither a headword nor a word which Chinese pupils are often exposed to. If children have difficulty in understanding the words in examples, they will not use the dictionary with enjoyment and enthusiasm. Thirdly, the headwords in these dictionaries are arranged differently: some are arranged thematically such as in Ertong Yinghan Baike Tujie Cidian (My First Visual Dictionary) while others are arranged alphabetically such as in Tujie Ertong Yinghan Cidian (Illustrated Children's English-Chinese Dictionary). Finally, the method of explanation used as in dictionaries for adults (such as only translation equivalents) may not be applicable to dictionaries for children of the three different categories, because children's understanding and cognitive abilities are very limited. Even in ECCDs, the methods of explanation should vary greatly according to the cognitive abilities of children at different ages.

Synthesizing these problems, this paper will address the following research questions:

(1) In what ways should a children's dictionary accommodate its target user group?

(2) How should the headword list of a children's dictionary be developed?

(3) Should the headword list of a children's dictionary be arranged alphabetically or thematically?

(4) How should word meanings be explained in a children's dictionary?

Section 2 discusses how to define the user group according to Piaget's cognitive development theory. Section 3 proposes that when selecting headwords, an English corpus for Chinese children should be taken into account. Section 4 compares the thematic arrangement with the alphabetical order in children's dictionaries. Section 5 discusses various ways of explaining word meanings.

2. Defining the user group according to Piaget's cognitive development theory

'In planning the preparation of a dictionary, it is of vital importance to decide as early as possible what character the dictionary should have, in type, size, users and so on' (Zgusta 1971: 221). Producers and editors need to identify the specific group of users when they commence designing a dictionary. Deciding upon the intended target user is the first stage of dictionary production in a four-stage process (Rundell 2010: 367). It is noted that 'during the last few years lexicographers have become more and more aware of the importance of the so-called user perspective - determining who the intended target user is and what his or her specific needs are with regard to the dictionary' (Potgieter 2012: 262). More and more producers and editors of ECCDs also become aware that they need to define the user group when they initiate a dictionary project.

All dictionaries are written for a specific user group, and the content and presentation must therefore be directed/aimed at that specific target group (Cheng 2001, Potgieter 2012). 'Child', a general term, usually refers to people younger than 16. In China, children are generally divided into two age groups. The first group is from 2 to 6 years old, and the second from 6 to 12 years old (Yu 1998: 960). Those aged between 12 and 18 are called teenagers. This category is only applicable to laws in China, different from the category based on children's cognition. But the age brackets of children vary according to countries. In Britain, 'child' refers to young persons under the age of 18 according to the Children Act of 1948, while it refers to young persons under the age of 16 in the Education Act of 1994. Therefore, there is no clear dividing line according to age for the term 'children'. In terms of lexicography, young people under the age of 16 are generally considered children.

In fact, children at different ages, even if all under the age of 16, are very different in terms of their cognitive development. According to Piaget's cognitive development theory (Piaget 1969), children's cognitive development can be divided into four stages. The first stage (birth to 2 years) is the sensorimotor stage in which children experience the world through their senses and actions. Object permanence and stranger anxiety are its main developmental phenomena. The second stage (2 to 6 years) is the preoperational stage in which children start to be able to represent things with words and images. The preoperational stage is characterized by three developmental phenomena: pretend play, egocentrism, and language development. The third stage, from 7 to 11 years old, sees children able to think logically about concrete events and grasp concrete analogies. It is called the 'concrete operational' stage, and is characterized by two developmental phenomena: conservation and mathematical transformation. Piaget refers to the fourth stage (12 onwards to adulthood) as the formal operational stage. In this stage, children can think about hypothetical scenarios and process abstract thoughts. It has two developmental phenomena: abstract logic and potential for mature, moral reasoning.

In the first stage, children only sense the world by natural feeling, touch and behaviour, and most children cannot use many words or use dictionaries. Therefore, a dictionary does not make sense for them. When they reach the second stage, children's language abilities develop very quickly by matching words and images or things. In the third stage, children begin to have logical thinking ability. The cognitive and learning abilities of children in the last stage approximate those of adults.

The focus of this paper is on children in the second and third stages (2 to 6 years, and 6 to 12 years, respectively). Although both are referred to as 'children', they differ considerably in cognitive and learning abilities. The word 'children' in the titles of many ECCDs is really ambiguous or unclear, since children's dictionaries should rather have two explicit categories: for younger children (2 to 6 years) and for primary school students (6 to 12 years old). At the beginning of a children's dictionary project, it is essential for producers and editors to identify its prospective users in terms of these age groups: either younger children or primary school students. The dictionaries for children over the age of 12 also vary greatly with adult dictionaries although they have fewer difficulties in using adult dictionaries than those under the age of 12. Headwords such as swear words should be excluded; slang should be selective; definitions are less complicated; and it is easy for children to carry their dictionaries around.

3. Selecting headwords based on a children's English corpus

After determining the group of intended users, the issue of how to select the headword list is the next challenge for developers of ECCDs. What words are children most likely to be exposed to? Which words should be included and which excluded? The criteria for lexical coverage should take into account the evidence from an English corpus for Chinese children. 'The children's corpus can be used to help lexicographers make decisions about headwords' (Wild et al. 2013: 190).

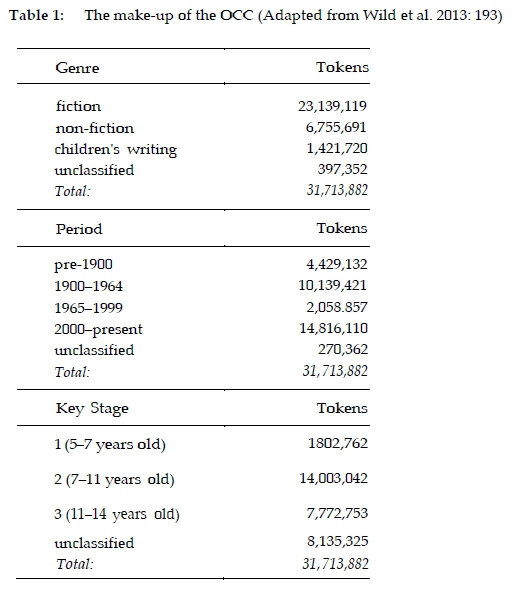

The Oxford Children's Corpus (OCC), a corpus of over 30 million tokens of writings targeted at 5-14 year-olds, contains a wide range of fiction, non-fiction, children's writing, etc. (see Table 1).

The subcorpus of children's writings (approximately 1.4 million tokens) is made up of material from websites where children have posted reviews, poems and stories. There are plans to expand this part of the corpus, so that the language that children use can be compared with the language to which they are exposed. Hence, typical spelling and usage errors committed by children can be identified (Wild et al. 2013: 194). Since its creation in 2006, lexicographers have used oCC to make decisions about headwords in writing dictionaries for children. Wild et al. (2013: 207-208) offer a case study of how the OCC helped to select the list of musical instruments in children's dictionaries. The first step was obtaining a list of musical instruments in order of frequency from the oCC. The raw data had to be manually checked due to some polysemous words in the list not being in the required sense. There are some surprising findings in the list, such as the high frequencies of the words lute and lyre, which are mainly found in history texts for KS3 (11 to 14 years old). This type of findings from a children's corpus can help lexicographers make decisions about which words should be included in children's dictionaries for different age groups. Similarly, the list of headwords in ECCDs should also be based on an English corpus for Chinese children. Without a corpus as evidence, an editor is likely to exclude some words to which children are mostly exposed, and include some words to which children are seldom exposed.

A children's English corpus like the OCC has not yet been built in China, though there are some small corpora of children's language for specific research purposes. A 7-million-token Chinese corpus, which was based on popular Chinese books for children aged 1 to 12, has been constructed to investigate language features of children's books (Zhi 2016). in order to compare the use of different parts of speech, Gu (2018) has also constructed a very small Chinese children's cartoon corpus (48,401 tokens) and a foreign children's animation corpus (48,900 tokens). Xu (2018) has created a small corpus, consisting of data from audio story books for children aged 3 to 6. However, these corpora will do little to ECCDs. In addition, none of them are freely accessible.

To produce a reliable headword list and select appropriate examples (see Section 5.2.2), lexicographers of ECCDs call for a balanced English corpus for Chinese children. The corpus could consist of English textbooks for children, children's English magazines, children's books in English, children's compositions in English, etc. (cf. Unstead 2009), and be balanced in terms of text types, and of writings for children and writings by children. In addition, websites, children's English cartoons and other digital texts are very essential corpus sources in the digital era.

While constructing an English corpus for Chinese children, the OCC can be a reference. However, a close imitation is not advocated. In terms of data sources, the corpus for Chinese children should mainly include English novels popular in China rather than in Britain. Popular English novels in other parts of the English-speaking world should also make an appropriate contribution. in OCC, the writings by children are made up of material from websites where English children have posted reviews, poems and stories, whereas an English corpus for Chinese children should consist of compositions, test papers and other material written by Chinese children. In OCC, there are three classified key stages: 5-7 years old, 7-11 years old, and 11 -14 years old. Because of different proficiency levels, a corpus for Chinese children should have three different key stages: 2-6 years old, 6-12 years old and 12-16 years old.

4. Arranging the headwords list: thematically vs. alphabetically

In monolingual Chinese dictionaries for primary school children, the headwords are predominantly arranged in alphabetical order, for pupils have learnt pinyin (the standard system of Roman spelling in Chinese) in school. An index of radicals of Chinese characters and sometimes an index of strokes of Chinese characters are also provided to help students to locate a Chinese character whose pronunciation is not known.

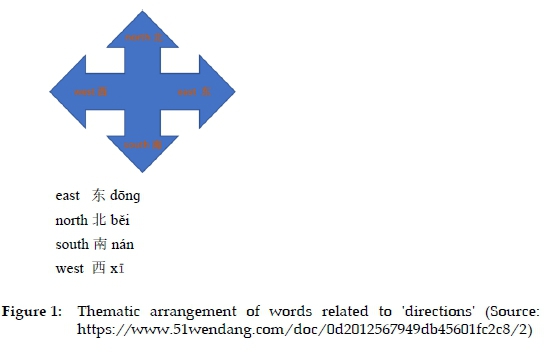

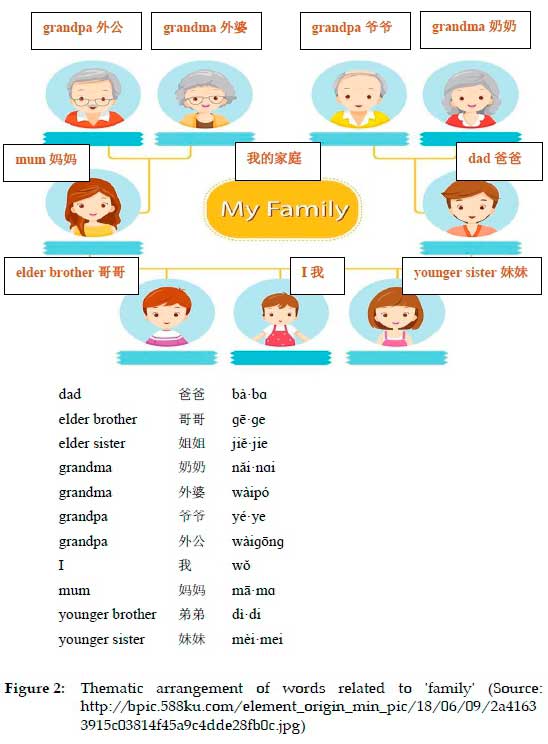

In ECCDs for primary school students, compilers can arrange the headword list in alphabetical order, because pupils are very familiar with the sequence of the alphabet. However, in ECCDs for younger children, it is beyond their ability to look up an English word in a dictionary arranged alphabetically. For this reason, a thematic arrangement would be more suitable. Headwords can be arranged in semantic sets, including related concepts, synonyms, etc. To help these younger children to use an ECCD, lexicographers can choose themes that will appeal to children, such as shapes, transport, colours, animals, plants, toys, and games. The words related to a theme can be shown in one picture. In this way, images will not only represent the referents but also reflect the relationship among related words. Accompanying headwords can then be arranged alphabetically, and sometimes explained with simple sentence examples. Consider the two themes - 'directions' and 'family' - in Figures 1 and 2.

The two samples demonstrate that it is more effective for this age group to group words related to theme than to scatter them throughout a dictionary arranged alphabetically. The thematic arrangement shows the relationships among the headwords in a group. Children can clearly get to know how they are connected to each other. This method is suitable for related words in a semantic field, such as furniture, facilities in the playground, colours, musical instruments, toys, and transport. But for some abstract nouns (e.g., honour, loyalty, truth) or abstract verbs (e.g., discuss, compare, evaluate, analyse), it will be unsuitable. Unlike an alphabetical arrangement, a thematic order can attract younger children, and promote their understanding of related concepts. Therefore, dictionaries for younger children should combine fun and learning.

However, there are some downsides to the thematic arrangement. It takes up considerable space, and pictorial illustrations are potentially expensive. In addition, words in thematic order are inconvenient to look up, and it is also difficult to fit examples (or definitions) into a highly illustrated thematic structure. Therefore, it would be a good idea to supplement it with an index of English headwords in alphabetical order, and an index of Chinese equivalents in pinyin.

5. Multifaceted methods of explanation

5.1 Pictorial illustrations in ECCDs for younger children

One of the vital functions of a children's dictionary is to help users understand the meaning of a headword in question. While verbal definition is a major method in a monolingual dictionary, a bilingual dictionary uses translation equivalents and/or example sentences. In ECCDs for younger children, few provide example sentences. Sole translation equivalents can hardly meet the needs of younger children. Therefore, pictorial illustration plays a significant role in this type of children's dictionaries.

Dictionaries are generally consulted rather than read as running text. However, in ECCDs for younger children, a dictionary is read rather than consulted, because the main task is to help younger children acquire English vocabulary. What they want to know is not 'why it is' but 'what it is'. Dictionaries for them should be interesting and attractive. Pictorial illustration, either photographic, digitally created or hand-drawn, serves this function. 'An illustration is a particular kind of image which is used in conjunction with a text and which decorates, illustrates, or explains the text' (Klosa 2015: 516). Lew et al. (2018: 53-54) further point out that of the three functions Klosa has discussed, explaining the text that is 'the most central function of lexicographic illustration'. Similarly, it is not decorating but explaining the text is the main function of a pictorial illustration in ECCDs. A pictorial illustration helps children to build up connection between a headword and its designatum.

In dictionaries for younger children, pictorial illustration is not a complement but a principal method of explanation. Its main function is to help younger children acquire second language vocabulary and build connection between images and words. Therefore, it is a challenge for illustrators to create suitable pictures to match children's cognitive levels, appeal to their interests, and support their understanding of headwords. In order to meet the standards, the pictures should be representative, attractive and vivid.

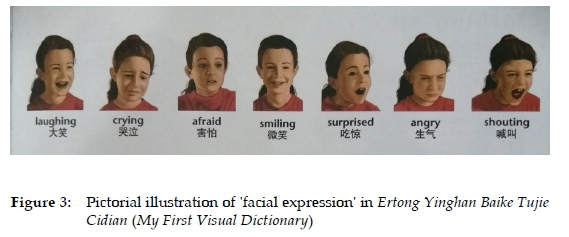

Consider the following pictorial illustration of 'facial expression' in Ertong Yinghan Baike Tujie Cidian (My First Visual Dictionary).

Images 2 (crying), 3 (afraid) and 6 (angry) in Figure 3 have not clearly represented their corresponding meaning. Image 2 shows that the girl is sad but not 'crying': there are no tears on her face. From Images 3 and 6, it is difficult to discern whether the girls are really 'afraid' or 'angry' from their facial expressions. Also, arguably, laughing, crying, smiling, shouting are not emotions (which are by definition nouns), although happiness, sadness, amusement and fear/anger are.

To summarize, in ECCDs for younger children, pictorial illustration complements translation equivalent. Editors need to acquire some understanding of the principles of good illustration and the stages of children's development before they can select appropriate pictures for illustration. In order to avoid inappropriate pictures, illustrators can join in the work of compiling, and psychologists could be consulted if necessary. Feedback from children on draft or sample illustrations would also be very helpful in selecting the most appropriate illustrative style or approach.

5.2 Multifaceted methods of explanation in ECCDs for primary school students

5.2.1 Pictorial illustration

In ECCDs for primary school students, pictorial illustration does not play a dominant role as in ECCDs for younger children, because users at this later stage have some basic language knowledge and can recognize some basic English words. Nevertheless, when being asked to define an ideal dictionary, this group of children still listed attractive pictorial illustrations as one of the most important features (Turrini et al. 2000). Visual content makes a dictionary more attractive (Klosa 2015: 516, Biesaga 2017: 133). This is particularly true of school dictionaries.

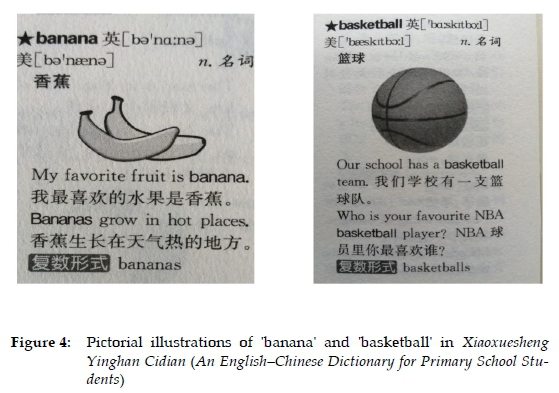

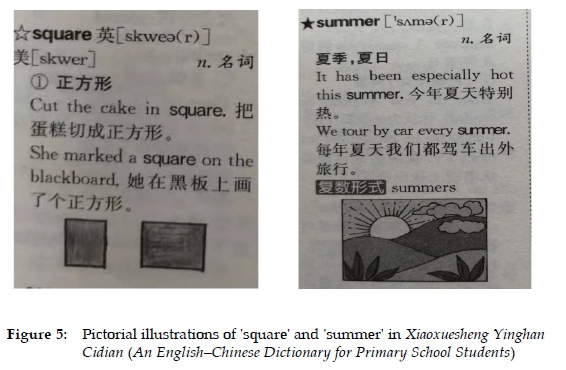

Due to technical, financial and other factors, pictorial illustration is not often used in a general-purpose dictionary (Biesaga 2017: 134). However, some words are more appropriately illustrated with a picture than defined verbally, such as musical instruments, household goods, computer equipment, styles of architecture, animals, plants and furniture. In terms of categories like fruit, games, vegetables, plants and clothes, it is not difficult to illustrate them with appropriate pictures, as Figure 4 demonstrates. But some pictorial illustrations in an ECCD may cause confusion. As Figure 5 shows, one of the images in the pictorial illustration at square is not a square but a rectangle. Similarly, learners have no idea whether the pictorial illustration at summer is meant to suggest 'sun', 'landscape' or something else. A defined word should be linked to a clear pictorial illustration. There are some other issues with the entries in these figures, such as an article and a plural missing in the two sentence examples: "My favorite fruit is [a] banana." at banana, and "Cut the cake in square [squares]." at square.

5.2.2 Examples

Unlike dictionaries for younger children, lexicographers can offer some simple examples in ECCDs for primary school students. It is commonly accepted that examples help users understand headwords, and complement grammatical information. Some principles of exemplification in learner's dictionaries have been proposed. Examples should provide the typical usage of headwords (Fox 1987), should have practical applicability (Moulin 1983), and should be easy to understand (Lemmens and Wekker 1991, Atkins 1995, Potgieter 2012), natural and concise (Cowie 1999).

As for exemplification in ECCDs for primary school students, compilers should focus on the following three aspects. Firstly, they should select, from a corpus, typical as well as simple example sentences. In terms of contexts of usage, typical examples are more informative than untypical ones, and primary school students are more likely to encounter similar sentences. In addition, examples should be easy to comprehend, because pupils do not have adequate knowledge to understand some difficult words and complicated sentence structures (Thorndike 1991: 15). Admittedly, corpus-based examples may include words and structures beyond children's proficiency. In this case, lexicographers can eliminate or revise them.

Secondly, the chosen examples should assist learners in understanding the meaning and proper use of headwords by providing typical contexts of usage. Consider how Zhongguo Xiaoxue Yingyu Xuexi Cidian (An English-Chinese Dictionary for Primary School Learners in China) and Waiyanshe Kelinsi Yinghan Hanying Cidian (FLTRP COLLINS Elementary English-Chinese Chinese-English Dictionary) exemplify miss in (1) and (2), respectively.

(1) Henry has missed the bus.

(2) - Did you get on the train? - No, I missed it.

- Goodbye! I'll miss you. - I'll miss you, too.

For this headword, Waiyanshe Kelinsi Yinghan Hanying Cidian (FLTRP COLLINS Elementary English-Chinese Chinese-English Dictionary) appears to be more useful than Zhongguo Xiaoxue Yingyu Xuexi Cidian (An English-Chinese Dictionary for Primary School Learners in China), since the former distinguishes the two different senses of miss with separate example sentences (showing the verb can be used for an inanimate object - 'the train' - as well as for a person). The brief dialogues in the former dictionary show the typical use of the headword in a way that is more comprehensible to children. In contrast, example (1) uses 'missed' in a way that gives the user little idea of the meaning of the word: one could replace 'missed' with 'painted', for example, or several other verbs, and the sentence would still make sense.

Thirdly, ECCDs should give prominence to grammatical information that children just beginning to learn English often confuse, because of the influence of Chinese grammar - the negative L1 transfer. According to Jiang (2000: 47), second language learners at the early stage are likely to copy the lemma information of the L1 counterpart into the L2 lexical entry, thus mediating L2 word use. if the grammatical usage of an English headword is different from that of its Chinese equivalent, the negative L1 transfer will come into play. A typical error committed by children is the inflection of an English predicate verb. While an English verb must agree with the number and person of the subject in a sentence, Chinese is an inflection-free language. To inhibit the transfer of L1 Chinese, lexicographers can illustrate the grammatical usage with some sentence examples. For instance,

English Chinese

I am a student. 我是一个学生 (wö ski yïgè xuéshëng)

You are a student. 你是一个学生 (ni ski yïgè xuéshëng)

She/He is a student. 她/他是一个学生 (tä ski yïgè xuéshëng)

We/They are students. 我们/他们是学生 (wömen/tämen ski yïgè xuéshëng)

Considering space for print and time for lexicographers, examples of be can be optimized as follows:

I am / You are / She is / He is a student.

我是/你是/她是/他是一个学生 (wö shi/ni shi/tä shi/tä shi yïgè xuéshëng) We/They are students. 我们/他们是学生 (wömen/tämen ski xuéshëng)

We may take for granted the inflection of 'be'. However, many Chinese pupils often commit such errors, for the Chinese equivalent shi does not change its form whatever the subject is.

As an essential didactic tool for language acquisition, a school dictionary should provide children with some example sentences (and sometimes usage notes), which warn them against potential grammatical errors caused by L1 negative transfer. To identify pupils' grammatical errors, lexicographers can exploit resources such as an English composition corpus by Chinese children and a grammar book.

To recapitulate, examples in ECCDs should use simple words and grammatical structures to demonstrate the typical context of usage of a headword, its grammatical properties and semantic features.

6. Conclusion

Children's dictionaries should not be an abridgement or simplification of dictionaries for adult learners. Factors such as children's proficiency level and learning and cognitive abilities have an impact on the making of ECCDs. In this paper, we propose distinguishing dictionaries for younger children from those for primary school students, because children in the two periods are quite different in terms of language development and cognitive ability. The construction of an English corpus for Chinese children is imperative because corpus data could facilitate the production of a reliable and useful headword list, and the selection of typical sentence examples which demonstrate the semantic, syntactic, and collocational features of a headword. In addition, evidence provided by corpus data can be used to warn students against potential grammatical errors. Pictorial illustration complements translation equivalent in ECCDs for younger children and for primary school students. In addition, words used in example sentences should be congruent with children's limited cognitive and learning abilities.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Philosophy and Social Science Fund of the 13th Five-year Plan of Guangdong Province of China (Project No. GD18XWW02) and China Scholarship Council (No. 201808440098). We are grateful to Professor Elsabé Taljard and two anonymous adjudicators for their valuable comments and suggestions. Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Hai Xu.

References

A. Dictionaries

Huo, Qingwen (Ed.). 2001. Zhongguo Xiaoxue Yingyu Xuexi Cidian (An English-Chinese Dictionary for Primary School Learners in China). Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. [ Links ]

Institute of Linguistics, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (Ed.). 1953. Xinhua Zidian (Xinhua Dictionary of Chinese Characters). Beijing: The Commercial Press. [ Links ]

Li, Yuzhi (Ed.). 2003. Xinbian Xiaoxuesheng Yinghan Cidian (The Brand-New English-Chinese Dictionary for Primary School Students). Beijing: The Commercial Press. [ Links ]

Luo, Lie and Qinghua Xiao (Eds.). 2017. Xiaoxuesheng Yinghan Cidian (An English-Chinese Dictionary for Primary School Students). Chengdu: Sichuan Lexicographic Publishing House. [ Links ]

QA International (Ed.). 2004. Ertong Yinghan Baike Tujie Cidian (My First Visual Dictionary). Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. [ Links ]

Yu, Shutong (Ed.). 1998. Xinhanying Faxue Cidian (A New Chinese-English Law Dictionary). Beijing: Law Press. [ Links ]

Zhang, Daozhen. 2000. Tujie Ertong Yinghan Cidian (Illustrated Children's English-Chinese Dictionary). Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. [ Links ]

Zhang, Siying (Ed.). 2006. Waiyanshe Kelinsi Yinghan Hanying Cidian (FLTRP COLLINS Elementary English-Chinese Chinese-English Dictionary). Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. [ Links ]

Zhong, Jiayan (Ed.). 2011. Zhongguo Xiaoxuesheng Yingyu Xuexi Cidian (An English-Chinese Dictionary for Primary School Learners in China). Changchun: Jilin Education Press. [ Links ]

B. Other literature

Atkins, B. T. S. 1995. The Role of Examples in a Frame Semantics Dictionary. Shibatani, M. and S.A. Thompson (Eds.). 1995. Essays in Semantics and Pragmatics: In Honour of Charles J. Fillmore: 25-42. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Béjoint, H. 2000. Modern Lexicography: An Introduction. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Biesaga, M. 2017. Dictionary Tradition vs. Pictorial Corpora: Which Vocabulary Thematic Fields Should Be Illustrated? Lexikos 27: 132-151. [ Links ]

Cheng, Rong. 2001. Hanyu Xuexi Cidian Bianzuan Tedian de Tantao (Features of the Compiling of Chinese Learners' Dictionary). Cishu Yanjiu (Lexicographical Studies) 2: 64-71. [ Links ]

Cowie, A.P. 1999. English Dictionaries for Foreign Learners: A History. Oxford: Oxford University Press/Clarendon Press. [ Links ]

De Schryver, G.-M. and D.J. Prinsloo. 2011. Do Dictionaries Define on the Level of their Target Users? A Case Study for Three Dutch Dictionaries. International Journal of Lexicography 24(1): 5-28. [ Links ]

Fox, G. 1987. The Case for Examples. Sinclair, J.M. (Ed.). 1987. Looking Up. An Account of the COBUILD Project in Lexical Computing and the Development of the Collins COBUILD English Language Dictionary: 137-149. London/Glasgow: Collins ELT. [ Links ]

Gavrilidou, M., V. Giouli and P. Labropoulou. 2008. The Greek High School Dictionary: Description and Issues. Bernal, E. and J. DeCesaris (Eds.). 2008. Proceedings of the 13th EURALEX International Congress, EURALEX 2008, Barcelona, Spain, 13-19 July 2008: 515-524. Barcelona: Institut Universitari de Linguistica Aplicada, Universitat Pompeu Fabra. [ Links ]

Gu, Mengmeng. 2018. Jiyu Yuliaoku de Ertong Donghuapian Yanjiu (Corpus-based Research on Vocabularies in Children's Animations). M.A. Thesis. Shanghai: Shanghai Normal University. [ Links ]

Jiang, N. 2000. Lexical Representation and Development in a Second Language. Applied Linguistics 21(1): 47-77. [ Links ]

Klosa, A. 2015. Illustrations in Dictionaries. Encyclopaedic and Cultural Information in Dictionaries. Durkin, P. (Ed.). 2015. The Oxford Handbook of Lexicography: 515-531. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Kosch, I. 2013. An Analysis of the Oxford Bilingual School Dictionary: Northern Sotho and English. Lexikos 23: 611-627. [ Links ]

Lemmens, M. and H. Wekker. 1991. On the Relationship between Lexis and Grammar in English Learners' Dictionaries. International Journal of Lexicography 4(1): 1-14. [ Links ]

Lew, R., R. Kazmierczak, E. Tomczak and M. Leszkowicz. 2018. Competition of Definition and Pictorial Illustration for Dictionary Users' Attention: An Eye-tracking Study. International Journal of Lexicography 31(1): 53-77. [ Links ]

Moulin, A. 1983. The Pedagogical/Learner's Dictionary II: LSP Dictionaries for EFL Learners. Hartmann, R.R.K. 1983. Lexicography: Principles and Practice: 144-152. London: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Piaget, J. 1969. Psychologie et Pédagogie. Paris: Denoël. [ Links ]

Potgieter, L. 2012. Example Sentences in Bilingual School Dictionaries. Lexikos 22: 261-271. [ Links ]

Rozman, T. 2008. Mother-tongue's Little Helper (The Use of the Monolingual Dictionary of Slovenian in School). Bernal, E. and J. DeCesaris (Eds.). 2008. Proceedings of the 13th EURALEX International Congress, EURALEX 2008, Barcelona, Spain, 13-19 July 2008: 1317-1324. Barcelona: Institut Universitari de Linguistica Aplicada, Universitat Pompeu Fabra. [ Links ]

Rundell, M. 2010. Taking Corpus Lexicography to the Next Level: Explicit Use of Corpus Data in Dictionaries for Language Learners. Zhang, Y. (Ed.). 2010. Learner's Lexicography and Second Language Teaching: Proceedings of First International Symposium on Lexicography and L2 Teaching and Learning: 367-386. Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press. [ Links ]

Sene Mongaba, B. 2016. A Terminological Approach to Making a Bilingual French-Lingala Dictionary for Congolese Primary Schools. International Journal of Lexicography 29(3): 311-322. [ Links ]

Tarp, S. and L. Ruiz Miyares. 2013. Cuban School Dictionaries for First-Language Learners: A Shared Experience. Lexikos 23: 414-425. [ Links ]

Thorndike, E. 1991. The Psychology of the School Dictionary. International Journal of Lexicography 4(1): 15-22. [ Links ]

Turrini, G., A. Paccosi and L. Cignoni. 2000. Software Demonstration: Combining the Children's Dictionary Addizionario with a Multimedia Activity Book. Heid, U., S. Evert, E. Lehmann and C. Rohrer (Eds.). 2000. Proceedings of the Ninth EURALEX International Congress, EURALEX 2000, Stuttgart, Germany, August 8th-12th, 2000. Vol I: 107-110. Stuttgart: Institut für maschinelle Sprachverarbeitung, University of Stuttgart. [ Links ]

Unstead, S. 2009. A Question of Words. Books for Keeps: The Children's Book Magazine 175. https://booksforkeeps.co.uk/article/a-question-of-words/. [ Links ]

Verburg, M. 2006. The Making of My First Van Dale: A Pre-School Dictionary. Corino, E., C. Marello and C. Onesti (Eds.). 2006. Proceedings of the 12th EURALEX International Congress, EURALEX 2006, Torino, Italia, September 6-9, 2006: 357-362. Alessandria: Edizione Dell'Orso. [ Links ]

Wild, K., A. Kilgarriff and D. Tugwell. 2013. The Oxford Children's Corpus: Using a Children's Corpus in Lexicography. International Journal of Lexicography 26(2): 190-218. [ Links ]

Xu, Kaili. 2018. Jiyu Yuliaoku de 3-6 Sui Ertong Yousheng Gushi Yuyan Yanjiu (Corpus-based Research on Audio Stories Language of Children Aged 3-6). M.A. Thesis. Shanghai: Shanghai Normal University. [ Links ]

Zgusta, L. 1971. Manual of Lexicography. Prague: Academia. [ Links ]

Zhi, Luyao. 2016. Jiyu Hanyu Ertong Duwu Bianxie de Hanyu Yuliaoku Jianshe (The Construction of Chinese Corpus Based on Chinese Children's Books). M.A. Thesis. Guangzhou, Guangdong University of Foreign Studies. [ Links ]