Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Lexikos

On-line version ISSN 2224-0039

Print version ISSN 1684-4904

Lexikos vol.31 Stellenbosch 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.5788/31-1-1643

ARTICLES

A Lexico-phonetic Comparison of Olukumi and Lukumi: A Procedure for Developing a Multilingual Dictionary

Une comparaison lexico-phonétique d'Olukumi et de Lukumi: une procedure pour développer un dictionnaire multilingue

Joy Oluchi Uguru

Department of Linguistics, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria (joy.uguru@unn.edu.ng)

ABSTRACT

Generally, most multilingual dictionaries do not give adequate lexical and phonetic information (like contrasts and distributions). This could delay language learning (particularly among second language learners). This study demonstrates a comparative display of lexico-phonetic features of Lukumi and Olukumi in a proposed multilingual dictionary. The study, based on cognitive semantics and variation theories, proves that this display reveals how the user can distinguish the lexical and phonetic details within and across the languages. Downloaded Lukumi wordlists (132 words) were used to elicit information on Olukumi equivalents through an oral interview conducted in Ukwunzu, a major Olukumi speaking community in Delta state, Nigeria. However, 74 words were purposefully selected for comparative analysis while 23 words were used to demonstrate dictionary compilation. Through comparative analysis, free variants, synonymous and polysemous words were discovered and displayed in the dictionary. The study concludes that adequate lexical and phonetic comparison (and analysis) of words is vital in compiling a multilingual dictionary and will facilitate dictionary usage and language learning.

Keywords: lexico-phonetic, olukumi, lukumi, multilingual dictionary, COGNITIVE SEMANTICS, VARIANTS, FREE VARIATION

RÉSUMÉ

En général, la plupart des dictionnaires multilingues ne donnent pas d'informations lexicales et phonétiques adéquates (comme les contrastes et les distributions). Cela pourrait retarder l'apprentissage des langues (en particulier chez les apprenants de langue seconde). Cette étude démontre un affichage comparatif des dispositifs phonétiques lexico de Lukumi et d'Olukumi dans un dictionnaire multilingue proposé. L'étude, basée sur la sémantique cognitive et les théories de la variation, prouve que cet affichage révèle comment l'utilisateur peut distinguer les détails lexicales et phonétiques dans et entre les langues.Les listes de mots Lukumi téléchargées (132 mots) ont été utilisées pour obtenir des informations sur les équivalents Olukumi grâce à une interview orale menée à Ukwunzu, une importante communauté parlant olukumi dans l'État du Delta, au Nigeria.Cependant, 74 mots ont été délibérément sélectionnés pour l'analyse comparative tandis que 23 mots ont été utilisés pour démontrer la compilation du dictionnaire. Grâce à l'analyse comparative, des variantes libres, des mots synonymes et polysémiques ont été découverts et affichés dans le dictionnaire. L'étude conclut qu'une comparaison (et une analyse) lexicales et phonétiques adéquates des mots est essentielle à la compilation d'un dictionnaire multilingue et facilitera l'utilisation des dictionnaires et l'apprentissage des langues.

Mots-clés: LEXICO-PHONETIQUE, OLUKUMI, LUKUMI, DICTIONNAIRE MULTILINGUE, SÉMANTIQUE COGNITIVE, VARIANTES, VARIATION LIBRE

1. Introduction

According to Rundell (2012) all linguistic procedures play important and key roles in dictionary compilation. This is so because all aspects of language are interconnected and these aspects, manifested through linguistic procedures, are displayed in the dictionary. Hence it is necessary to adopt the right linguistic procedures in order to have a good and reliable dictionary. In this paper, the procedures of phonetic transcription, procedures involving the determination of phonemic variants, procedures of parts of speech classification and procedures of meaning analysis through cognitive semantics are some of the procedures undertaken in the sample compilation of Lukumi and Olukumi (with English gloss) multilingual dictionary.

Schierholz (2015) shows that different methods and phases are involved in dictionary compilation. He cites Wiegand (1998) as outlining the following phases: the preparation phase, the phase of acquiring the material and the data, the phase of treating the material and the data; the evaluation phase and the phase of preparing the material for printing.

This study defines lexico-phonetic comparison as one of these phases that are necessary for compiling a good multilingual dictionary; it could be categorized under the phases of treating and evaluating the data. Lexico-phonetic comparison is important because the proposed dictionary is a new project; hence adequate information about the languages is necessary. According to Schierholz, the lexicographer should determine the type of project being undertaken (old or new). This will go a long way to help him or her know what steps to take.

Thus this study stands at a good pedestal to produce a reliable dictionary because the necessary linguistic procedures and lexicographic methods have been adopted. For such linguistic systems (as Lukumi and Olukumi) that are largely unwritten and without standard forms, good procedures are necessary to avoid producing a dictionary that may not effectively capture their lexicon. The display of pronunciation and phonetic variables in dictionaries on African languages, particularly, is rare (Uguru and Okeke 2020; Stark 1999). This study is geared towards performing this rare and difficult task since; presently, the use of Lukumi and Olukumi is mainly oral.

In Delta state of Nigeria, a number of linguistic systems with unique features abound. These include Ika which manifests intonation and tone (Uguru 2015) unlike other Igbo dialects. Olukumi is another unique system, being a Yoruboid language spoken in an environment where Igbo is predominantly spoken (in Oshimili Local Government Area). It has high similarities with Lukumi, also a Yoruboid language spoken in Cuba (Uguru and Okeke 2020). Both varieties are in the New Benue Congo subgroup of the Niger Congo family. Lukumi has the code, ISO 639-3 luq while that of Olukumi (spelt Ulukwumi by Ethnologue) is ISO 639-3 ulb. Both are spoken by Yoruba descendants. These varieties resulted from slavery and migration respectively. Scholars have shown that Olukumi is highly related to Yoruba (Arokoyo 2012; Okolo-Obi 2014). Also, Lukumi is highly related to Yoruba (Ayoh'Omidire 2017).

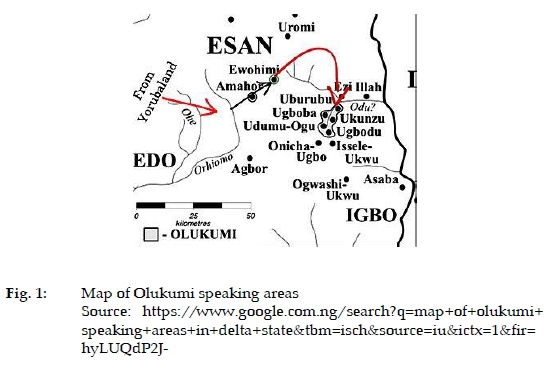

Lukumi speakers are descendants of Yoruba slaves taken to Cuba. Olukumi is spoken by descendants of Yorubas who migrated from Western Nigeria to Eastern Nigeria; it is spoken in Ugbodu, Ukwunzu, Ubulubu, Idumu-ogo and Inyogo. See fig. 1 below.

According to Mason (1997) in Cuba, Lukumi (also spelt as Lucumi, Ulcumi or Ulcami) refers to Africans of Yoruba descent as well as their language. He further reveals that in the United States, Lukumi is synonymous with Orisha worship because it is basically used for traditional Yoruba religion.

Both Olukumi and Lukumi are largely unwritten and not studied in schools. Therefore, the compilation of a dictionary is a good way of enhancing their development and usage for both oral and literary purposes. In this study therefore, we show how their lexical items can be compiled, displaying their lexical and phonetic features comparatively to enable language users and learners to easily capture their similarities and dissimilarities. This research therefore, will aid their documentation and preservation.

According to Mason (1997) Yoruba descendants are called by different names in various countries: in Brazil, they are known as the Nago or the Jeje while in Haiti they are known as the Nago. In Trinidad, they are called Sango/ Shango and in Cuba, they are known as the Lukumi. Hence Lukumi designates both the language and the Yoruba descendants.

Mason (1997) further shows that Lukumi was preserved due to Africans' resistance to whites' cultural oppression. It is closely tied to the Yoruba traditional religion. In fact, Mason (op cit.) shows that in the United States, Lukumi does not refer to the descendants of Africans from Nigeria or Cuba but rather to people (irrespective of ethnicity) who practise the Yoruba traditional religion.

According to Brandon (1993) Lukumi is a sacred ritual language. Santeria worshippers are forced to use Lukumi; many worshippers could not understand the language. Olmsted (1953) therefore shows that Lukumi is a highly conservative language; worshippers believe that they can go on with worship whether they understand the language or not. According to Brandon (1993) it is acquired in adolescence and adulthood, some people learning from copyings in notebooks; thus they have limited knowledge. Furthermore, Brandon reveals that the pronunciation and spelling of Lukumi are not uniform; the variety is known by several names like Lukumi, Ulcami, Lucumi and so on. This can be confusing. Hence, studying and documenting the language in a multilingual dictionary will aid in having uniform pronunciation and spelling for its name.

Ayoh'Omidire (2003) published a book, Àkògbádün: ABC da Língua, Cultura e Civilização Iorubanas, for students in Brazil. It contains information about Orisha and Yoruba culture, poetries, songs and comparison of Brazilian Orishá traditions and Yorúbá customs. Arokoyo and Mabodu (2017) compiled Olukumi-English bilingual dictionary. However, it has some flaws as some of the lexical items were not well documented. For instance, aso (cloth) was not documented yet aso abe (under cloth), aso erefuná (curtain) and aso oyin (bee wax) were included. Also, though pronunciation was indicated, the IPA symbols were not strictly followed; this could be confusing to readers. Furthermore, phonetic features like allophonic variants were not shown. Most importantly, the information supplied is on one language; the English equivalents are just the gloss of the headwords. Also, Anderson, Arokoyo and Harrison (2012) compiled a talking dictionary. This also had lapses as many words were omitted in addition to the fact that the variants and other phonetic information necessary for effective language learning were not included.

There are concerns of imminent death of Olukumi due to the influence of Igbo language spoken in neighbouring communities (Onwueme 2015). Lukumi retains Yoruba features because it is solely used for religious purposes (Ayoh'Omidire 2017). Albeit, its survival is also threatened since it is not used for everyday communication; hence the necessity of compiling a dictionary on the two varieties. The lexico-phonetic comparison carried out in this study includes the procedures of phonetic and phonological analyses, classification of parts of speech; and analysis of the meanings of lemmas. These will be aligned comparatively between the varieties and compiled for easy identification.

Lexico-phonetic information in dictionaries

While it is more straightforward, and perhaps, easier to reflect lexical information (particularly meaning and grammar) in dictionaries, it appears somewhat more tasking to indicate phonetic information of headwords in dictionaries (Sobkowiak 2000). This may be why most dictionaries, particularly those on African languages do not contain phonetic information (Uguru and Okeke 2020; Mbah et al. 2013). This is more so because the common goal in dictionary compilation is mainly meaning (Jain 2003).

The tendency for lexicographers to focus on meaning may be the reason why pronouncing dictionaries are necessary. In pronouncing dictionaries, the pronunciation and phonetic details of lemmas are displayed for language users. Such dictionaries display the pronunciation and variants to which language users can make reference. However, though these may be beneficial, they may not be easily available. Furthermore, they are not convenient to use; hardly could a language user obtain a pronouncing dictionary in addition to a learner's or general dictionary. Hence it is wiser to include phonetic information in the widely used types of dictionaries so that greater number of people will be conversant with the pronunciation of the language. Stark (1999) in his study of about fifty research works on dictionary usage, laments that only a few was centred on learners' pronunciation. Rather, the studies showed that learners neglect the phonetic aspect of language but are prone to looking up information on meaning, spelling and grammar. He summarizes this gap with the following excerpt from Sobkowiak (2000: 244):

The place of phonetics in dictionaries generally, and in learners' dictionaries in particular, its role in the composition of the macro- as well as the microstructure of the dictionary, the wonder and challenge of multimedia in machine-readable dictionaries, the psycholinguistic issues of pronunciation look-up, and many others are all waiting to be researched.

Based on the foregoing, the present study recommends that the proposed Lukumi/Olukumi dictionary, which is a learner's dictionary, include phonetic information in addition to lexical/ semantic information. This will enable foreign learners, native learners and other users have detailed information about the spoken form of the language. Hence, theories that can adequately account for, analyse and reflect both lexical and phonetic information about the varieties under study are necessary.

Booij (2003) laments that traditional dictionaries tend to emphasize written language. He shows that this ought to be corrected since information about the phonetic features of words is part of lexical information; hence it should not be ignored in the compilation of a dictionary. In giving the phonetic information, the variants of phonemes (if any) are also displayed to enable the users of the dictionary to be conversant with all the available usage featuring in the linguistic system. For instance, a Yoruba dictionary with phonetic information should give the user information about the status of [ã] in Yoruba. It should show that it is not phonemically contrastive but rather in free variation relationship with [5]. Jain (2003) has argued that each variation should be entered separately in the dictionary. We, however, argue against this because it will not only be confusing to the dictionary user, but will also make the document to be too voluminous. Rather, we propose that each variant should be attached to its headword. This way, the dictionary user knows alternating pronunciations to a given lemma. It has been shown that the pronunciation of a headword, given in International Phonetic Association symbols, should be clearly indicated in a dictionary (Jain 2003). The pronunciation of the symbols can also be simplified in the preliminary pages of the dictionary.

Sobkowiak (2000) reveals that there should be more research on the phonetic structure and choice of keywords so that the dictionary user can be well guided when looking up phonetic information. According to him, this task of phonetic look-up is difficult; hence the lexicographer needs to simplify it by making descriptions with the right choice of words and key phonetic structures. Also, words and phonetic transcriptions should be listed in such a way that they are easy to pronounce.

In giving lexical information in dictionaries, Booij (2003) opines that the emphasis should not be on giving all the possible meanings of a lemma; rather focus should be on showing its function and usage in the language. The part of speech of the lexical entry is also very vital information to be included in the dictionary. The meaning of the word, preferably given in one word, is the central information given about the lexical entry. It is however important to consider the type of dictionary and its users in giving information about headwords.

Theories for analyses

Linguistic and lexicographic theories enable the lexicographer to adequately analyse and synthesise linguistic data for dictionary compilation (Swanepoel 1994). The theories of variation and that of cognitive semantics form the base of this study. Cognitive semantics shows that language is acquired through cognition; that is, it is based on the conception of its speakers (how they conceive the world). Hence, each language will be made up of the concepts and objects around its speaker. Language is therefore, culture-bound. The concepts and objects first exist in the mind as thought patterns before being named. Hence it is only natural that people may not be able to have a lexical item for a concept or object that is not in their immediate environment, particularly if they do not have access to them. Thus though concepts are not tied to particular languages, they are influenced by environments and culture; this is why there are varied categorizations of lexical items for concepts. Hence the data used for this study are concepts that Lukumi speakers are familiar with.

The variation theory enables us to examine, explain and link the variations between the linguistic varieties. Variation means saying the same thing in different ways (Meechan and Rees-Miller 2001). It means representing a concept or object with different words. It also includes the use of varying symbols in the lexical item to represent the same object or concept (Jarrar 2018). The latter definition is the main focus of this paper. Phonology appears to be a prominent domain in which variation features (Guy 2007).

Indicating linguistic variation in a dictionary will not only avail users with alternative usages, but also aid in informing them about the origins and etymology of the variable/variant. All languages have variations; these may originate from dialects, social groups, professions and so on. Hence linguistic variation is a natural phenomenon that should not be neglected in pursuit of a standard. In the case of Lukumi and Olukumi which are still undergoing development, without any standard, it is important to include their linguistic variables (particularly phonetic variables) in their documentation. This will aid in any future development of a standard form.

According to Lanwermeyer et al. (2016) dialect variation influences phonological and lexical-semantic word processing in sentences. In their lexico-phonological comparison of lexical items in two dialect areas (Central Bavarian and Bavarian-Alemannic transition zone) they discover that /oa /oa-oa-/ and /ou - ou -/ are used variously in the two dialects. For instance, the word for straw is /Jtroa -oa -/ in BA, but in CB it is pronounced as /Jtrou-ou-/. This kind of variation, if not explained to language learners, could lead to difficulties in form-meaning associations in the dialect areas. Hence a dictionary such as the one this study projects, is very necessary. When these sound variations do not yield meaning differences, then the varying sounds are allophones and this must be pointed out in the dictionary. Information to be given includes whether occurrence is conditioned as well as the environments in which they occur. If they are not conditioned, then they are free variants (in free variation). Free variation is a situation where two or more sounds or forms occur in the same environment without a change in meaning. Alternating variants occur in regular patterns (Guy 2007).

Hence, it is significant that Olukumi and Lukumi, which are spoken by people in different continents, have a lot of lexical and phonetic similarities. Going by the cognitive semantic interpretation of their word meanings, lexical and phonetic similarities portray the fact that they have the same origin. There can be no other plausible explanation for this high degree of similarities.

Hence it is important to indicate the phonetic features of words in a dictionary since it will not only make for ease of usage, but will also reveal the relationship (that is, similarities or otherwise) between the concerned languages. Dellert et al. (2020) assert that most grammar books contain general information about the phonology of languages, and that languages, particularly less documented ones, rarely have phonetic transcriptions for individual words. They show that this causes people to depend on the written forms which could be problematic if the orthography does not fully represent pronunciation.

Adda-Decker and Lamel (2006) reveal that even in the use of speech recognizing systems, indicating phonetic features in multilingual dictionaries, particularly, helps to reduce poor performance since multilingual dictionaries contain non-native speech forms. However, most lexicographers de-emphasize phonetic features and that has resulted in its non-reflection in most dictionaries. Cermák (2010) in discussing steps in dictionary compilation, de-emphasizes pronunciation, showing that it is used only for distinction and for foreign words. This view is erroneous since anybody can benefit from the indication of the phonetic features of entries in any dictionary because both native and second language speakers (and also learners) can have access to the dictionary.

2. Methods

Lukumi word lists were downloaded from some websites (cf. references) because Lukumi is not spoken in the environment of research. Seventy four words were purposefully selected for comparative analysis and twenty three words were used to demonstrate dictionary compilation. An Olukumi native speaker supplied the Olukumi equivalents of the downloaded words during an oral interview. The equivalents in Olukumi and Lukumi were compared with words bearing similar concepts. Cognitive theory was used to analyse lexical meaning and variation theory was used to determine the phonetic variables in the two varieties. The effect of these phonetic variables on the meanings of lemmas was examined in the varieties.

Additionally, similarities and differences in the occurrence and distribution of Lukumi and Olukumi phonemes were determined. Based on this, a sample compilation of the proposed dictionary was done.

3. Lexico-phonetic comparison of Lukumi and Olukumi

In this section, the words are analysed in terms of their meanings and parts of speech and the phonemes are analysed in terms of their similarities, variation and distribution.

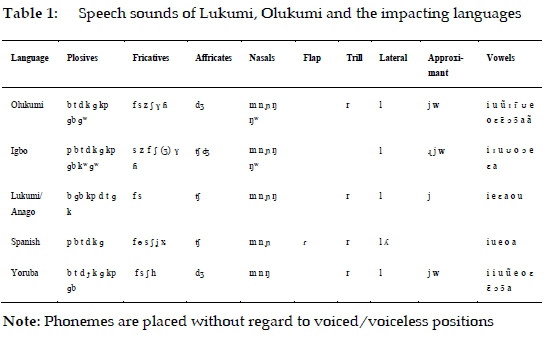

3.1 Phonetic comparison of the speech sounds of Lukumi and Olukumi

In this section, phonemes and lexical items that made up the sample wordlist are displayed in the following tables.

Phonetic comparison of Lukumi and Olukumi

Phonetic similarity is concerned with articulatory, acoustic, and perceptual similarities between vowels and consonants (Schepens et al. 2013).

In terms of the phonetic details, it can be observed that some Yoruba phonemes which do not exist in Lukumi exist in Olukumi. Hence Lukumi speakers replace the phonemes with those nearest to them in articulation. For instance /gb/ is replaced with /b/ in Lukumi since the former does not feature in the variety.

3.2 Prosody

The analysis of the prosodic features in the varieties is shown below.

3.2.1 Tone

Adeshokan (2018) reveals that just like in Spanish, accents feature in Lukumi words. Tone, a feature of Yoruba, the parent language, does not feature in Lukumi but it exists in Olukumi.

3.2.2 Stress and syllabic structure

Lukumi words are not tone marked but rather accents (typical of Spanish) are used to indicate stressed syllables and they usually occur in word final position (Ramos 2012; Concordia 2012). As can be observed from the data, Lukumi and Olukumi have CV syllable structure. Hence they do not have closed syllables. Spanish has a closed syllable structure but that did not influence Lukumi.

Also there are some linguistic processes that occur in both Lukumi and Olukumi varieties. For instance, syllabic repetition as a way of expressing colour is evident in the expression of dudu (Lukumi for dark) and okwukwu (Olukumi for the same colour). Similarly, funfun (white) for both varieties has syllabic repetition. Furthermore, syllable elision is observed in Olukumi. Observe the examples below.

Lukumi Olukumi

Baba ba

Babalawo awo

Yeye ye

3.3 Lexical comparison of Lukumi and Olukumi

Vowel nasality appears to be a common feature in both varieties as seen in funfun, nwun, eyin and so on. Thus the varieties share some phonetic features in addition to lexical and semantic similarities.

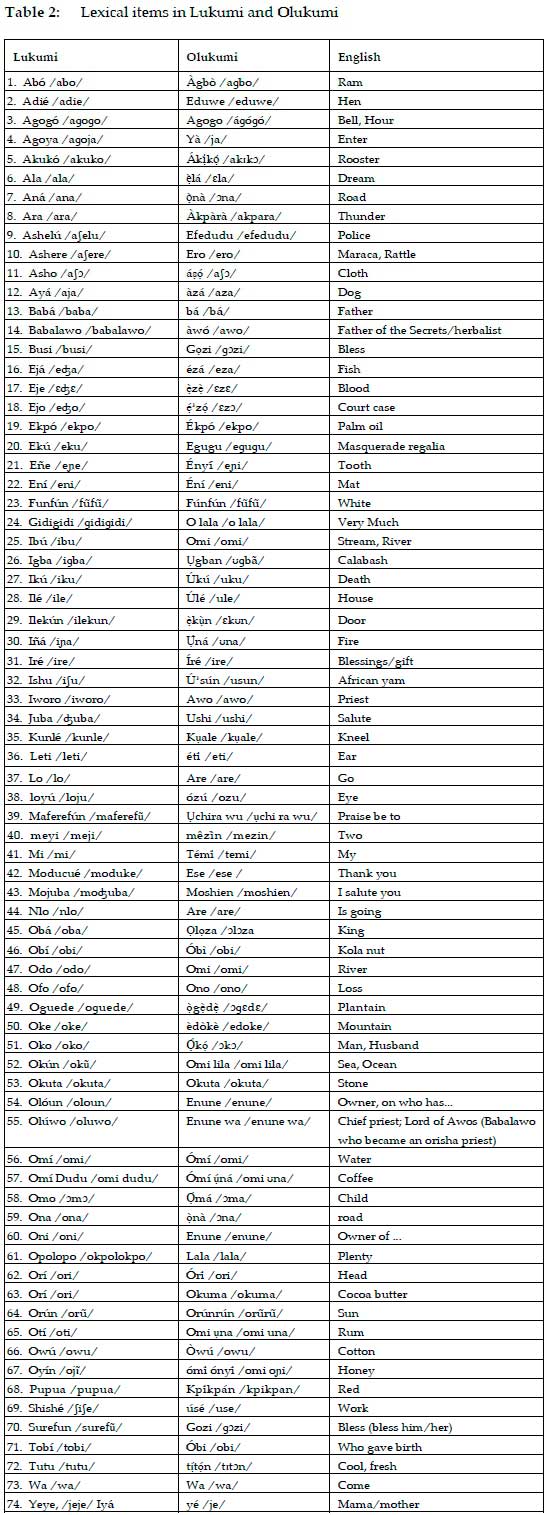

These can be clearly shown in lexical items in Lukumi and Olukumi which appear below.

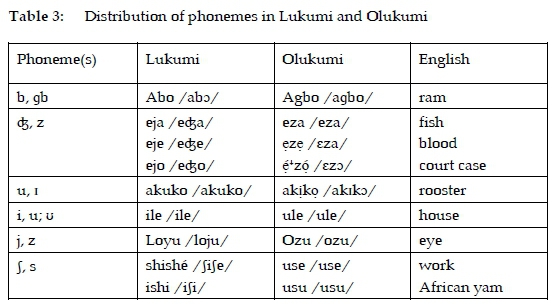

From the data above, some distribution of phonemes can be seen. These are shown in table 3.

3.4 Discussion

From Tables 2 and 3, it can be observed that many of the concepts in the two varieties have the same form units. Also, some allophones exist in the varieties.

That is, some words have varying phonemes without such variations yielding changes in meaning. The allophones can be proposed to be used as free variants by language users/learners since the lemmas do not have any change of meaning when the allophones are interchanged; more so, their occurrence does not appear to be conditioned by any environment/phoneme. This is similar to what operates in the English language where either British or American spellings can be used by writers. Just as American spelling and pronunciation are indicated in dictionaries of English language, and users are free to use any one, in the proposed dictionary, Lukumi and Olukumi allophonic variations are indicated for users. Consequently, dictionary users are free to adopt anyone they feel like using since the lexical meanings are not changed by the use of varied allophones. This is what this study is all about: to display these allophonic variations and show their impact on lexical meanings.

Indicating the free variation existing between the two varieties will go a long way to help speakers and dictionary users alike. This is so because, since the variations are not complementary, grammar books alone cannot adequately be used to explain their usage to users of the languages. The variations must necessarily be pointed out in the dictionary and this is what the projected dictionary will do. This will go a long way to help learners, particularly those who use Lukumi mainly for religious purposes.

The meaning analysis of the words used for the study portrays that there are some synonymous and polysemous words in the varieties. It takes lexical analysis of meaning, using cognitive semantics, to arrive at this. These are pointed out for learners as shown in our sample compilation below. The Olukumi word for water omi for instance, is used for water, stream/river; and indicates it in its equivalent for ocean/sea 'omi lila' ocean. On the contrary, furthermore, the word 'omi' is used to show a sense of liquid as seen in omi una (rum; Olukumi data 65) (hot drink - literal translation). The same expression is also used synonymously with the equivalent for coffee (see data no. 57). Omi dudu (Lukumi data 57) and efe dudu (Olukumi data 9) reflect that both varieties make use of description in naming some concepts. Lukumi has the following words for these concepts: omi, (water), ibu (stream), okun (ocean). Similarly, Lukumi has a number of synonyms as shown in Table 2. While Olukumi has only one word, gozi, for bless, in Lukumi, both busi and surefun mean bless. All these could be confusing for a language learner hence it should be the duty of the lexicographer to reduce ambiguity by accurate indication of these features in the dictionary. These can be seen in the sample compilation below.

4. Sample compilation of lemmas for the multilingual dictionary

In a previous paper, a certain form of compilation was adopted because three languages were involved; also, free variants and detailed lexical information as well as cross references were not included. An excerpt from that paper is shown below (Uguru and Okeke 2020).

Hence, still maintaining space economy as was done in the previous paper, a new compilation method is adopted here to create room for more information that this study sets out to display in the dictionary.

In the proposed dictionary, it will be clearly pointed out at the preliminary pages, that since most head words have the same meanings in both varieties, indication of variety will only be made in cases of sound and meaning differences. That is, where there is a difference in form units. The preliminary pages will also contain the phonemes of the varieties as well as the sounds involved in free variation. Below, demonstration is made, showing sample compilation of the dictionary. The compilation shows how lemmas with the same form units can be entered, how those with varying phonemes can be entered, and how those that differ in form units can be represented in the dictionary. In addition, lexical and meaning information is given, pointing out synonymous and polysemous headwords.

4.1 The Sample Dictionary Compilation

4.1.1 Preliminary page information

Outline of phonemic distributions: In most cases, sound distribution in both varieties is as follows: in most environments where Lukumi would use the following sounds - /b, e, c%, i, j, J/ Olukumi would use the following: / gb, e, z, u, z and s/. Hence the following sounds could be used interchangeably, in the varieties, for some headwords which have the same meaning but vary in one or two phonemes: b/gb, e/e, ct;/z, i/u, j/z and J/s.

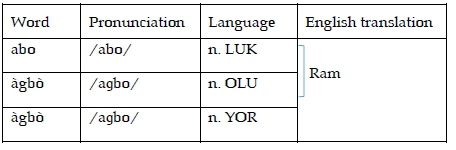

1. Abo /abo/ (ram) N; àgbò /agbo/ (Oluk) [b] / [gb] (free variants)

2. Agogó /agogo/ (bell) N.

3. Akuko /akuko/ (rooster) N. akiko /akik5/ (Oluk) u / i (free variants)

4. Babalawo (herbalist; keeper of secrets) N; Awo /awo/ (Oluk): OLUWO; IWORO

5. Busi /busi/ (bless) V; gozi /gozi/ (Oluk): SUREFUN

6. Eja /ecfea/ (fish) N; eza /eza/ (Oluk) [d3] / [z] free variants

7. Eje /ecfee/ (blood) N; eze /eze/ (Oluk)

[e] / [e]; [ct;] / [z] free variants

8. Ejo /ect;o/ (court case) N; é4,zO /ezo/ (Oluk)

[e] / [e]; [ct;] / [z] free variants

9. Ibú /ibu/ (stream, river) N; omi /omi/ (Oluk) - COMPARE OKUN, ODO, OMI

10. Ile /ile/ (house) N; ule /ule/ (Oluk)

[i] / [u] free variants

11. Ishi /ijï/ (African yam) N; usu /usu/ (Oluk)

[i] / [u]; [J] / [s] free variants

12. Iworo (chief priest) N; awo /awo/ (Oluk): BABALAWO, OLUWO

13. Iyá /ija/ (fight) N; úzà /uza/ (Oluk)

[i] / [u]; [j] / [z]; free variants

14. Loyu /loju/ (eye) N; Ozu /ozu/ (Oluk)

[j] / [z] free variants

15. Odo /odo/ (river) N; omi /omi/ (Oluk): COMPARE IBU, ODO, OMI

16. Okun /oku/ (ocean) omi lila /omi lila/ (Oluk): COMPARE IBU, ODO, OMI

17. Oluwo /oluwo/ (chief priest, lord of Awos) N; Enune wa (Oluk): BABALAWO, IWORO

18. Omi /omi/ (water) N.

19. Owó /owo/ (money) N. éghó /eyo/ (Oluk)

20. Pupua /pupua/ (red) Adj; Kpikpán /kpikpan/ (Oluk)

[p] / [kp] free variants

21. Shishé /JiJe/ (work) N; use /use/ (Oluk)

[i] / [u]; [J] / [s] free variants

22. Surefun /surefu/ (bless him) V; gozi /gozi/ (Oluk): BUSI

23. Tutu /tutu/ (cool, fresh) Adj.; títOn /titon/ (Oluk)

Key of abbreviations used in the sample:

Adj. - adjective

N. - noun

Oluk. - Olukumi

Key of abbreviations:

Adj - adjective

N - noun

Oluk. - Olukumi

V - verb

Many phonemes, words and concepts in Lukumi and Olukumi are similar despite the distance separating the locations where they are spoken. Above, we have shown these lexical and phonetic similarities in a sample Lukumi-Olukumi multilingual dictionary (with English gloss). For the entries where free variants have been indicated for instance, either of the pronunciation is acceptable as seen in economics in English which can be pronounced /eknomiks/ or / iknomiks/. It is also applicable to Igbo language where the word for ground can be pronounced as /ala/, /ali/, /ana/ or /ani/. Hence the pronunciation for the word for ram can either be pronounced as /abo/ or /agbo/. As the features of these varieties are maintained this way, they will not die; this will particularly benefit the Nigerian variety, Olukumi, whose existence is said to be threatened (Onwueme 2015).

4.2 Discussion

There are lots of similarities in the phonemes and lexical items of Lukumi and Olukumi. Interestingly, lexical similarity appears to align with phonetic/phonemic similarity in these varieties. They have mainly phonetic spelling; that is, most of their phonemes bear the same symbols as the letters of their alphabet. This is because according to Coulmas (1996) alphabets for African languages were influenced by the work of phoneticians at the International Institute of African Languages and Cultures in London. They established the Practical Orthography of African Languages; it was influenced by the International Phonetic Association, thus being based on the principle of one letter corresponding to one sound.

4.2.1 Implications of the phonetic and lexical similarities for a multilingual dictionary

Showing the phonetic and lexical similarities of entries, as done in our sample compilation in this paper, equips the dictionary user (especially language learners) adequately to undertake the use of the dictionary with ease, being able to distinguish the sounds and entries that are peculiar to a variety and the ones they share. This reduces errors in language use.

Indicating the phonetic components of words in a dictionary makes the dictionary effective for comprehension (reading and listening) and production (writing and speaking) Mdee (1997).

4.3 The significance of the multilingual dictionary in Lukumi and Olukumi conservation

In line with Kroskrity (2015) this work has documented the lexical items of two varieties, Olukumi and Lukumi and compiled them, providing their English gloss. The study reveals their lexical and phonetic features and displays these in the sample dictionary compiled in section 4.1. This will help to preserve Olukumi (spoken in Delta state, Nigeria) which is largely endangered as well as Lukumi (spoken in Cuba) which is not used for everyday activities but rather solely for religious purposes. This step will preserve these varieties, spoken in diaspora, from going into extinction. Dictionaries are of obvious importance to endangered language communities, being learning resources to speakers, including those who are acquiring their heritage languages as second languages (Haviland 2006: 129).

The use of Lukumi solely for religious purposes cannot guarantee its maintenance. For instance the sole use of Latin as a religious language has not enhanced its survival or evolution into a modern language. Hence the documentation and compilation of these varieties (alongside English translations in a multilingual dictionary) as exemplified in this paper, will go a long way to ensure their regular and wider usage, thereby preserving them from imminent death.

5. Conclusion

In this paper, we have been able to comparatively analyse the lexico-phonetic features of Lukumi and Olukumi. The analysis aided the display of lexico-phonetic features in a sample compilation of a multilingual dictionary on the varieties. Thus, lexical and phonetic information of dictionary entries were shown in the dictionary, while maintaining space economy. It was discovered that the varieties have many concepts that are represented with the same form units; hence their lexical similarities are much. In the same vein, a lot of their phonemes are similar though there are a few that are peculiar to either varieties and these peculiar ones tend to occur in the same environment with their counterparts in the other variety. Due to this peculiarity, they share many words that are in free variation. This is already shown in the sample. Also, there are synonymous and polysemous words in the varieties, particularly Lukumi.

Hence, in the sample compilation, all these were taken into account. Information about the entries in free variation was included. Furthermore, the entries that are synonymous and polysemous respectively, were indicated through cross-referencing. With this depth of information given in the dictionary, users will find it easy to understand the varieties; language learning will be a lot facilitated.

The study confirms that dictionary compilation should not be haphazard. A good analysis of the language to be compiled is important to arm the lexicographer with detailed information to display in the dictionary. Based on the analysis of the two varieties under study, the entries of the proposed dictionary are categorised as follows: words of the varieties that have the same form units and the same meaning; those that have different form units for the same concept; those that differ in one or two phonemes (free variants) across the varieties and those concepts that are represented by more than one word as well as some words that denote more than one concept. Hence this knowledge enabled adequate explanation of the entries. Therefore, we have shown how the lexical items can be compiled in the dictionary in such a way that the dictionary user can easily identify features that distinguish the entries, those that the varieties share as well as those they can interchange (free variation). This has been made possible by the analysis of lexical and phonetic features of the words.

References

Dictionaries and word lists

Anderson, G.D.S., B. Arokoyo and K.D. Harrison. 2012. Olükümi Talking Dictionary. Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages. Available at: http://www.talkingdictionary.org/olukumi and http://talkingdictionary.swarthmore.edu/olukumi/.

Arokoyo, B.E. and O. Mabodu. 2017. Olükümi Bilingual Dictionary. 2017. Oregon: Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages.

Lucumi Dictionaries. Available at: https://www.orishaimage.com/blog/dictionaries. Downloaded 30 January 2018.

Lucumi Vocabulary. Available at: http://www.orishanet.org/vocab.html. Downloaded 30 January 2018.

Map of Olukumi speaking areas

Available at: https://www.google.com.ng/search?q=map+of+olukumi+speaking+areas+in+delta+state&tbm=isch&source=iu&ictx=1&fir=hyLUQdP2J-. Downloaded 30 January 2018.

Oral interview

Lucumi Vocabulary. Available at: http://www.orishanet.org/vocab.html and https://www.orishaimage.com/blog/dictionaries. Downloaded 30 January 2018.

Ogwu, E. 2017. Word list collected from Ogwu, E. 2017. Headmaster of a primary school in Ukwunzu, (oral interview) researcher: 31st March 2017.

Other literature

Adda-Decker, M. and L. Lamel. 2006. Multilingual Dictionaries. Schultz, T. and K. Kirchhoff (Eds.). 2006. Multilingual Speech Processing: 123-168. Amsterdam et al.: MA: Academic Press.

Adeshokan, O. 2018. An In-depth Look into Lucumi and Yoruba in Comparison. The Guardian, 18 March 2018. Available at: https://guardian.ng/life/an-in-depth-look-into-lucumi-and-yoruba-in-comparison/.

Arokoyo, B.E. 2012. A Comparative Phonology of the Olukumi, Igala, Owe and Yoruba Languages. Paper presented at the Conference on Towards Proto-Niger Congo: Comparison and Reconstruction, Paris, 18-21 September 2012.

Ayoh'Omidire, F. 2003. Àkògbádún: ABC da língua, cultura e civilização iorubanas. (ABC of the Yoruba language, Culture and Civilization.) Salvador: EDUFBA. [ Links ]

Ayoh'Omidire, F. 2017. Yorúbá, Lukumí and Nagô: The Ilé-Ife Perspective. Available at: http://www.orishaimage.com/blog/felixayohomidire. Accessed 12/08/18.

Booij, G. 2003. The Codification of Phonological, Morphological, and Syntactic Information. Van Sterkenburg, P. 2003. A Practical Guide to Lexicography: 251-259. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. DOI: 10.1075/tlrp.6.30boo. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/300848849 6.1. [ Links ]

Brandon, G. 1993. Santería from Africa to the New World: The Dead Sell Memories. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

Cermák, F. 2010. Notes on Compiling a Corpus-Based Dictionary. Lexikos 20: 559-579. [ Links ]

Concordia, M.J. 2012. The Anagó Language of Cuba. Unpublished M.A. Thesis. Miami: Florida International University. [ Links ]

Coulmas, F. 1996. The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Writing Systems. Oxford, UK/Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell.

Dellert, J., T. Daneyko, A. Münch, A. Ladygina, A. Buch, N. Clarius, I. Grigorjew, M. Balabel, H.I. Boga, Z. Baysarova, R. Mühlenbernd, J. Wahle and G. Jäger. 2020. NorthEuralex: A Wide-coverage Lexical Database of Northern Eurasia. Language Resources and Evaluation 54: 273-301. [ Links ]

Guy, G.R. 2007. Variation and Phonological Theory CUUK1061B-Bayley, R. and C. Lucas (Eds.). 2007. Sociolinguistic Variation: Theories, Methods, and Analysis: 5-23. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available at: http://gregoryrguy.com/wp-content/uploads/GuyProofs-BayleyLucasvolpdf. [ Links ]

Haviland, J.B. 2006. Documenting Lexical Knowledge. Jost, G., P.H. Nikolaus and M. Ulrike (Eds.). 2006. Essentials of Language Documentation: 129-162. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Jain, M. 2003. Lexicography for Endangered Languages. Available at: http://www.tezu.ernet.in/wmcfel/pdf/Cog/lexico/03.pdf.

Jarrar, M. 2018. Introduction to Lexical Semantics. Lecture Notes on Introduction to Lexical Semantics. Birzeit University, Palestine. Available at: http://www.jarrar.info/courses/Jarrar.LectureNotes.LexicalSemantics.pdf.

Kroskrity, P.V. 2015. Designing a Dictionary for an Endangered Language Community: Lexicographical Deliberations, Language Ideological Clarifications. Language Documentation and Conservation 9: 140-157. [ Links ]

Lanwermeyer, Manuela, Karen Henrich, Marie J. Rocholl, Hanni T. Schnell, Alexander Werth, Joachim Herrgen and Jürgen E. Schmidt. 2016. Dialect Variation Influences the Phonological and Lexical-Semantic Word Processing in Sentences. Electrophysiological Evidence from a Cross-Dialectal Comprehension Study. Frontiers in Psychology 7:739. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00739. [ Links ]

Mason, J. 1997. Ogun: Builder of the Lukumi's House. Barnes, S.T. (Ed.). 1997. Africa's Ogun: Old World and New: 353-368. Second, expanded edition. Bloomington/Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

Mbah, B.M., E.E. Mbah, E.S. Ikeokwu, C.O. Okeke, I.M. Nweze, C.N. Ugwuona, C.M. Akaeze, J.O. Onu, E.A. Eze, G.A. Prezi and B.C. Odii. 2013. Igbo Adi. Nsukka: University of Nigeria Press. [ Links ]

Mdee, J.S. 1997. Language Learners' Use of a Bilingual Dictionary: A Comparative Study of Dictionary Use and Needs. Lexikos 7: 94-106. [ Links ]

Meechan, Marjory and Janie Rees-Miller. 2001. Language in Social Contexts. O'Grady, William, John Archibald, Mark Aronoff and Janie Rees-Miller (Eds.). 2001. Contemporary Linguistics: 485-524. Fourth edition. Bedford: St. Martin's. [ Links ]

Okolo-Obi, B. 2014. Aspects of Olukumi Phonology. A Project Report of the Department of Linguistics, Igbo and other Nigerian Languages, University of Nigeria. Nsukka: University of Nigeria. [ Links ]

Olmsted, D.L. 1953. Comparative Notes on Yoruba and Lucumí. Journal of the Linguistic Society of America 29 (2): 157-163. [ Links ]

Onwueme, I.C. 2015. Questions Not Being Asked: Topical Philosophical Critiques in Prose, Proverbs, and Poems. Bloomington: AuthorHouse. [ Links ]

Ramos, M.W. 2012. Obí Agbón: Lukumí Divination with Coconut. Miami: Eleda.Org. Available at: https://books.google.com.ng/books?isbn=1877845116. Downloaded 27 January 2018.

Rundell, Michael. 2012. It Works in Practice but Will it Work in Theory? The Uneasy Relationship between Lexicography and Matters Theoretical. Fjeld, R.V. and J.M. Torjusen (Eds.). 2012. Proceedings of the 15th Euralex International Congress, 7-11 August 2012, Oslo: 47-92. Oslo: Department of Linguistics and Scandinavian Studies, University of Oslo.

Schepens, J., T. Dijkstra, F. Grootjen and W.J.B. van Heuven. 2013. Cross-language Distributions of High Frequency and Phonetically Similar Cognates. PLoS One 8(5): e63006. [ Links ]

Schierholz, Stefan J. 2015. Methods in Lexicography and Dictionary Research. Lexikos 25: 323-352. [ Links ]

Sobkowiak, W. 2000. Phonetic Keywords in Learner's Dictionaries. Heid, U. et al. (Eds.). 2000. Proceedings of EURALEX 2000: 237-246. Stuttgart: IMS, Universität Stuttgart. [ Links ]

Stark, M. 1999. Encyclopedic Learners' Dictionaries. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer. [ Links ]

Swanepoel, P. 1994. Problems, Theories and Methodologies in Current Lexicographic Semantic Research. Martin, W. et al. (Eds.). 1994. Euralex 1994. Proceedings, Papers Submitted to the 6th EURALEX International Congress on Lexicography in Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 11-26. Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit. [ Links ]

Uguru, J.O. 2015. Ika Igbo. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 45(2): 213-219. [ Links ]

Uguru, J.O. and C.O. Okeke. 2020. Reflecting Pronunciation in a Multilingual Dictionary: The Case of Lukumi, Olukumi and Yoruba Dictionary. Lexikos 30: 519-539. [ Links ]

Wiegand Herbert Ernst. 1998. Wörterbuchforschung. Untersuchungen zur Wörterbuchbenutzung, zur Theorie, Geschichte, Kritik und Automatisierung der Lexikographie. Volume 1. Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter. [ Links ]