Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Lexikos

On-line version ISSN 2224-0039

Print version ISSN 1684-4904

Lexikos vol.31 Stellenbosch 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.5788/31-1-1652

ARTICLES

Lexicographic Data Boxes. Part 2: Types and Contents of Data Boxes with Particular Focus on Dictionaries for English and African Languages*

Leksikografiese datakassies. Deel 2: Tipes datakassies en hulle inhoud, met spesifieke verwysing na woordeboeke vir Engels en die Afrikatale

D.J. PrinslooI; Rufus H. GouwsII

IDepartment of African languages, University of Pretoria, South Africa (danie.prinsloo@up.ac.za)

IIDepartment of Afrikaans and Dutch, Stellenbosch University, South Africa (rhg@sun.ac.za)

ABSTRACT

This article, the second in a series of three on lexicographic data boxes, focuses primarily on the types and contents of data boxes with particular reference to dictionaries for English and African languages. It will be proposed that data boxes in paper and electronic dictionaries can be divided into three categories and that a hierarchy between these types of boxes can be distinguished, i.e. (a) a bottom tier - data boxes used as mere alternatives to other lexicographic ways of presentation such as the bringing together of related items and/or to make entries visually more attractive, (b) a middle tier - addressing more salient features e.g. range of application, contrast, register, restrictions, etc. and (c) a top tier - vital salient information, e.g. warnings, taboos and even illegal words. A distinction is made between data boxes which are universal in nature, i.e. applicable to any language, data boxes pertaining to a language family and data boxes applicable to a specific language.

Keywords: dictionaries, lexicographic data boxes, text boxes, shaded BOXES, AFRICAN LANGUAGES, SEPEDI, ISIZULU

OPSOMMING

Hierdie artikel, die tweede in 'n reeks van drie oor leksikografiese datakassies, fokus hoofsaaklik op die tipes datakassies en hulle inhoud, met spesifieke verwysing na woordeboeke vir Engels en die Afrikatale. Daar sal voorgestel word dat datakassies in papier- en elektroniese woordeboeke in drie kategorieë verdeel kan word en dat 'n hiërargie tussen hierdie tipes kassies onderskei kan word, d.w.s. (a) 'n onderste vlak - datakassies wat slegs as alternatiewe vir ander leksiko-grafiese aanbiedingsmetodes gebruik word soos die bymekaarbring van verwante items en/of om inskrywings visueel aantrekliker te maak; (b) 'n middelvlak - om meer opvallende kenmerke aan te spreek, bv. die reikwydte, kontras, register, beperkings, ens. en (c) 'n hoogste vlak - essensiële inligting, bv. waarskuwings, taboes en selfs onwettige woorde. Daar word onderskei tussen data-kassies wat universeel van aard is, dit wil sê van toepassing op enige taal, datakassies wat ter sake is vir 'n taalfamilie en datakassies wat van toepassing is op 'n spesifieke taal.

Sleutelwoorde: woordeboeke, leksikografiese datakassies, tekskassies, SKADU-DATAKASSIES, AFRIKATALE, SEPEDI, ISIZULU

1. Introduction

Data boxes are commonly used in paper and electronic dictionaries to convey a variety of data not typically catered for by, what could be called standard presentation procedures that employ for example items giving the paraphrase of meaning (definitions), translation equivalents, examples of usage, pictorial illustrations, pronunciation guidance, and frequency indicators. Data boxes are used in cases where data entries are required to improve the lexicographic presentation and treatment - they add value to the default treatment. They typically include a variety of data types such as guidance in terms of grammar, pronunciation, sense distinction, contrasting related words, restrictions on the range of application, register, pronunciation, etc. Gouws and Prinsloo (2005: 133) state that:

... text boxes are put to good use to convey relevant data which falls outside the scope of the default categories presented in the normal search fields of the article.

Oxford Bilingual School Dictionary: Zulu and English (OZSD) and Oxford Bilingual School Dictionary: Northern Sotho and English (ONSD) refer to their shaded boxes as usage notes and describe their nature as follows.

Usage notes guide learners on potential areas of difficulty, helping them avoid common mistakes. Usage notes are also used to give additional information on how and when to use a headword (OZSD and ONSD: vi).

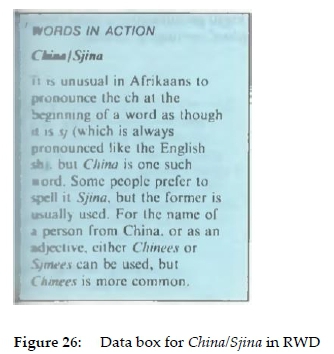

In the section "using your dictionary", Macmillan English Dictionary for Advanced Learners (MED) distinguishes between three types of shaded boxes, i.e. "information to learn more about how a word is used", "hints to avoid common errors" and notes that tell you about the origin of a word". Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary of Current English (OALDC) (Appendix 9: 1414) provides notes on usage of various types, e.g. clarification of grammar aspects, British and American usage or dealing with differences between words with similar meanings. Reader's Digest Afrikaans-Engelse Woordeboek / English-Afrikaans Dictionary (RWD) (page 5) informs the user about shaded boxes announced as "understand the other language as never before".

... there are always problems that constantly trip one up. In order to help you overcome the trickier points of style and usage we have included hundreds of 'words in action' ...

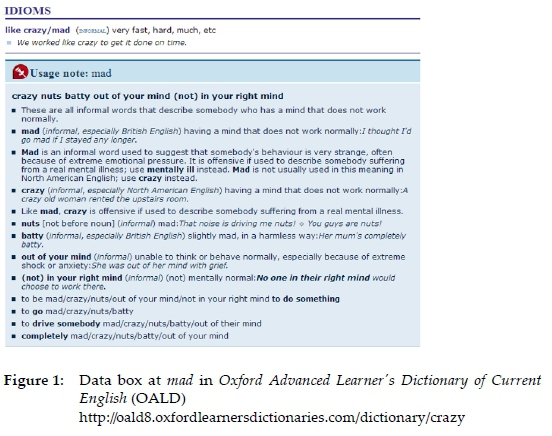

However, in spite of the frequent occurrence of data boxes in a variety of dictionary types, relatively little has been done to analyse data boxes with regard to the data types included in these boxes or the typological range of data boxes. This article embarks on an effort to identify different types of data found in data boxes of existing paper and electronic dictionaries and suggests that these boxes can be divided into three categories based upon type and content. it will be proposed that a hierarchical ordering between these categories can be distinguished, i.e. (a) a bottom tier - data boxes used as mere alternatives to other lexicographic ways of presentation, e.g. mere groupings or bringing together of related items. This is often done to make an entry visually more attractive; (b) a middle tier - giving more data, comparable to the type of additional data often found through cross-references, but addressing more salient features and (c) a top tier - vital salient data, e.g. warnings, taboos and even illegal words. Any attempt at the classification of data boxes is, however, arbitrary - no water tight classification is possible since a single data box often deals with a variety of issues as in figure 1. This data box primarily displays words and expressions semantically related to the word mad, but it also conveys other types of usage guidance. A number of bullets deal with register, i.e. formal versus informal use of the word, the third and fifth bullets deal with offensive use, the sixth bullet gives grammatical restrictions, and bullets 2, 3, 4, and 7 contrast language variations i.e. British English versus American English in this case.

Different scopes of application can also be distinguished, i.e. data box types which are (a) general in nature and not restricted to any specific language; (b) data box types pertaining to a language family and (c) data box types applicable to a specific language. Typical examples of the general utilization of data boxes are specifying semantic and syntactic restrictions, contrasting related words, warning against improper use, etc. Data boxes applicable to a language family deal with data that members of a specific language family have in common. Typical examples, given in a next section, of data boxes pertaining to a language family are those dealing with nominal classes, concords and pronouns. For a specific language it would, e.g. be data boxes giving syntactic restriction for specific words, e.g. question particles afa and afaeya in Sepedi.

This article does not take a critical approach to either the contents and presentation of data boxes or whether a specific entry that might perhaps be regarded as a data box in a current dictionary actually qualifies to be called a data box. Criteria for data boxes have yet to be formulated and it will not be done in this article. Data boxes are typically presented as frames or as a coloured background to one or more items in a dictionary. For the purpose of this article the occurrence of frames as a slot for the accommodation of certain items or of a coloured section functioning as highlighting background to certain items will be regarded as data boxes. A critical assessment with proposals for what should actually qualify as a data box is envisaged for the last article in this trilogy.

A topic not discussed in this article regards the metalanguage used in data boxes in bilingual dictionaries. Arguments could be offered that the metalanguage should be the source language of a monodirectional or of a specific component of a bidirectional bilingual dictionary, but equally compelling arguments could be offered that it should be the target language in both these dictionary types. The decision regarding the metalanguage should not be done in a haphazard way. Lexicographers need to determine the needs and reference skills of their target users and the lexicographic functions to be satisfied by a given dictionary. These matters should be considered when making a decision regarding the metalanguage to be used in the data boxes of any given bilingual dictionary, but space constraints do not allow a full investigation into this aspect in this article.

Updating both printed and online dictionaries inevitably leads to changes that can also influence their use of data boxes. The data boxes discussed in this paper come from specific editions and versions of the respective printed or online dictionaries. Some of these data boxes no longer appear in the most recent editions or versions. The authors of the article are aware of this situation but still use these examples due to their applicability to the discussion of specific contents or type of data box.

2. Proposed hierarchy of data boxes as found in current dictionaries

2.1 A bottom tier of data boxes

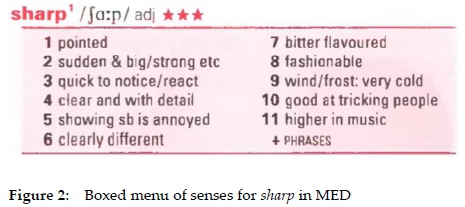

In this category data boxes are utilized for mere groupings, bringing together of related items, and to make entries visually more attractive. The first type of data box in the bottom tier that could be distinguished is a box containing a list that brings together the different senses in a menu that provides a quick overview, as in figure 2 in MED.

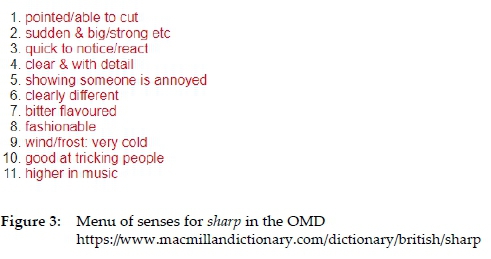

The boxed senses in figure 2 could as well be presented in an alternative way, consider the same lemma in the paper version versus the Macmillan Dictionary (OMD) in figure 3.

The menu in figure 3 is a mere summary of the senses that will be presented and this form of assistance is useful especially in the case of articles of words with multiple senses. By looking at this menu the user who is interested in sense 5, for example, can save time by skipping the subcomments on semantics in which senses 1-4 are presented and go directly to the subcomment on semantics containing sense 5.

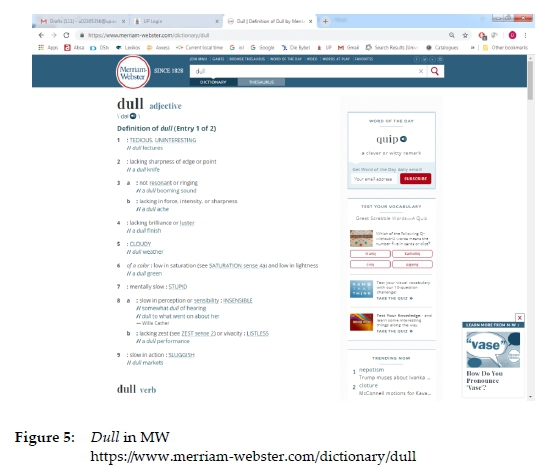

A second approach to boxing different senses is to box sense headings separately as in Cambridge Dictionary (CD) in figure 4.

In figure 4 in comparison to figure 2 the headings are not numbered nor given together but separately boxed at the start of each subcomment on semantics. The boxed information in figure 4 can be regarded as navigational devices, i.e. guide words. Taken at face value, words such as TEDIUS, UNINTERESTING, CLOUDY and STUPID in figure 5, are comparable to the boxed sections in figure 4 but words given in capital as well as lower case letters in figure 5 could be viewed as definitions.

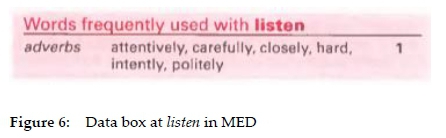

A third type of proposed low level data boxes is collocation boxes. The aim is to provide or bring together collocations of the lemma or derivatives and phrases in which it occurs in a data box as in figure 6.

The data box in figure 6 is useful to the reader looking up the word listen since it provides the typical collocations attentively, carefully, etc. in a box with the default treatment of listen.

Once again, the possible gain is on visibility - these collocations could be unboxed and presented, e.g. at the end of the article or in a search zone allocated to collocations.

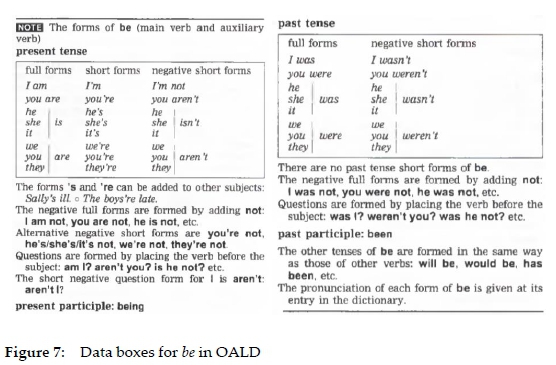

A fourth type can be regarded as mere note boxes as appropriately labelled as such in (OALD). Consider figure 7 as a typical example for the data boxes linked to be2in OALD. The entry brings together the different forms of the present and past tenses of the verb be under the heading "NOTE".

Figure 7 indicates what could be called note data boxes. The presentation starts with a horizontal line, followed by a white-on-black background capitalised label "note" and the present and past tenses boxed with full borders inside the note box amidst additional text. The note box as a whole does not have vertical lines on the left and right sides but is concluded by another horizontal line.

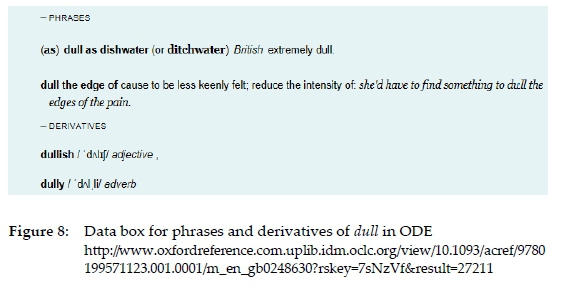

The Oxford Dictionary of English (ODE) uses data boxes for phrases and derivatives as in figure 8.

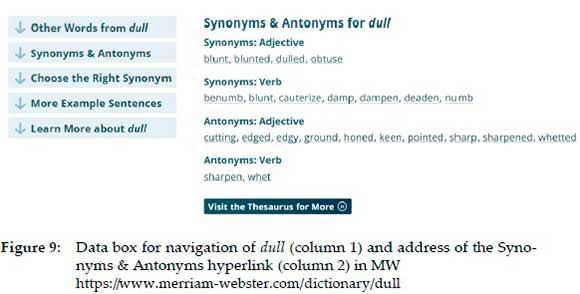

MW uses data boxes for navigation as in figure 9.

The guidance given in bottom tier boxes can also be conveyed by other means that are employed in various dictionaries. These means, which will not be discussed here, include shortcuts, as found in the OALD, signposts, as used in the LDOCE, and guide words, as presented in the Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary (CALD).

2.2 A middle tier of data boxes

This type of data box gives salient information that is not conveyed by items in the default search zones of the articles of a specific dictionary such as items giving the paraphrase of meaning, translation equivalent paradigms and examples of usage. Typical boxes deal with guidance in terms of grammar, pronunciation, sense distinction, contrasting related words, restrictions on the range of application, register, spelling, pronunciation, etc.

2.2.1 Data boxes used to contrast related words

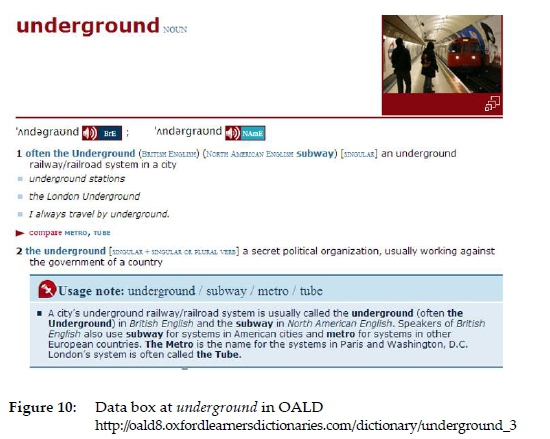

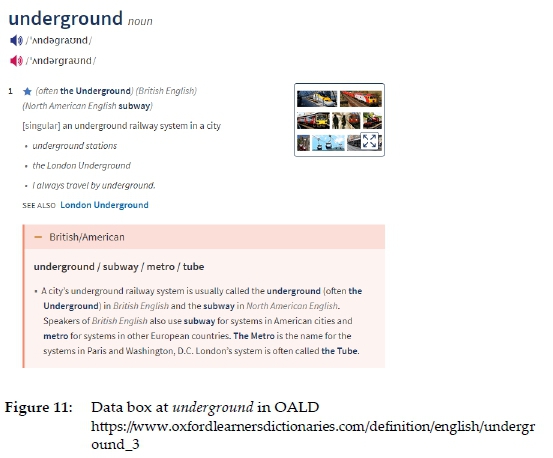

Typical of this type of data box is contrasting two or more words or different senses of the same word in variations of the language as in figure 10.

In figure 10 a data box linked to the first sense of underground nicely contrasts underground, subway, metro and tube in a very economical way. The same data box content is presented in the online Oxford Learners Dictionaries (https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com) but under the clickable menu item "+ British/ American underground / subway / metro / tube" as in figure 11.

This databox is repeated at metro, tube and subway.

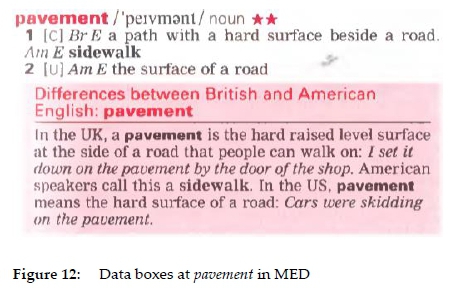

In figure 12 the data box for pavement contrasts British versus American English.

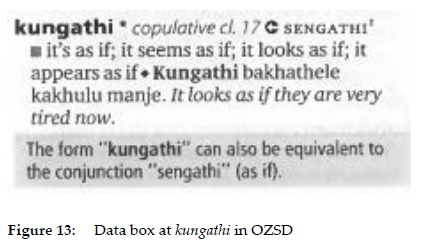

Consider also an isiZulu example for kungathi versus sengathi in figure 13.

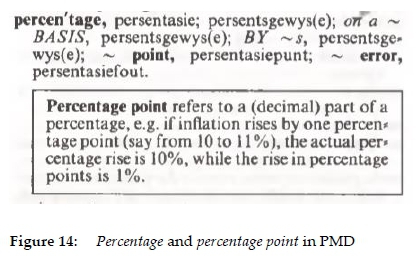

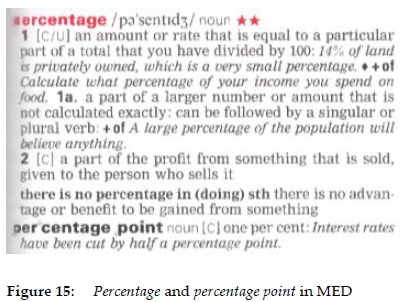

Once again, it has to be stated that lexicographers are under no obligation to provide data boxes for contrasting words - they could opt for alternative strategies or even not to contrast the words at all. Pharos Major Dictionary (PMD) treated percentage point as a sublemma in an article niche attached to the article of the main lemma percentage and provides a data box at the end of the article niche as in figure 14. The data box gives valuable additional information on percentage point and contrasts percentage and percentage point very well. In the presentation and treatment of percentage point in this case the compilers opted for a single subarticle where the default data type, i.e. a translation equivalent. is given but it is supplemented by an article-external data box. MED, however, takes a different approach by lemmatising and treating percentage and percentage point in two separate main articles without a data box or any effort to relate them as in figure 15.

2.2.2 Data boxes focused on application range or restrictions

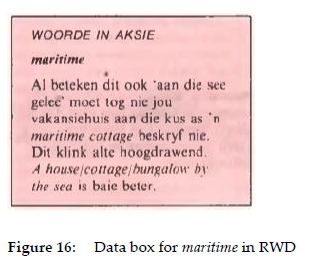

This type of data boxes guides the user in terms of the contexts in which a word can be used as well as instances where the use of such a word would be inappropriate. Consider figure 16.

in figure 16 the data box for maritime explains the meaning of maritime as 'adjacent to the sea' but that it should not be used to refer to a house at the seaside.

2.2.3 Data boxes providing grammar information

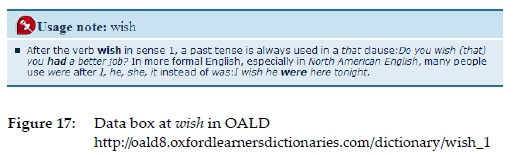

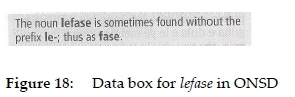

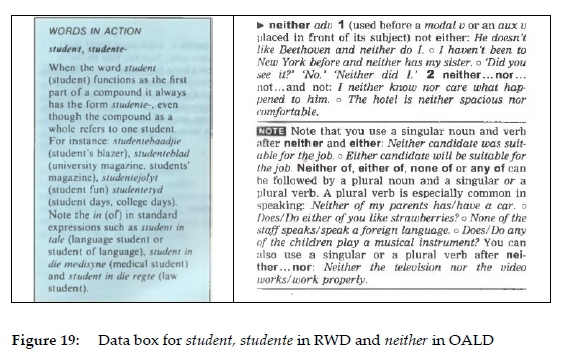

Data boxes giving guidance to correct grammatical use cover a variety of aspects such as the use of singular versus plural forms, tense forms of verbs, translations, abbreviated and irregular forms, etc. Consider figures 17 and 18:

The use of wish in figure 17 is restricted on grammatical grounds, i.e. in terms of tense and nature of the following verb.

in figure 18 the data box for lefase indicates its use without the prefix. Consider also the data boxes for student/studente and neither in figure 19. It indicates that the form studente- is required for use as the first part of a compound and that neither should be followed by a singular noun, etc.

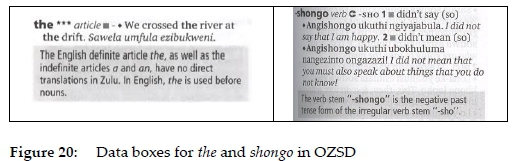

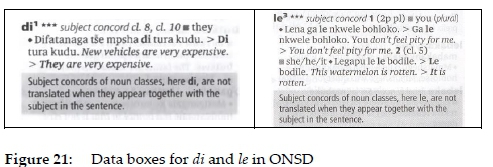

Finally the data boxes in figures 20 and 21 deal with the important issues, i.e. (a) that the, a and an do not have translation equivalents in isiZulu; (b) in certain cases subject concords are not translated [di1and le3] and (c) providing grammatical information on tense form of an irregular verb [-shongo].

2.2.4 Data boxes for pronunciation guidance

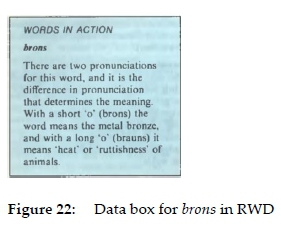

Pronunciation guidance is usually given in the default treatment of the lemma by means of descriptions, respelling or phonetic symbols, but specific pronunciation issues such as pronunciation comparison with other words can be given in data boxes. In figure 22 the "o" in brons is described in terms of the basic characteristics of "short" and "long".

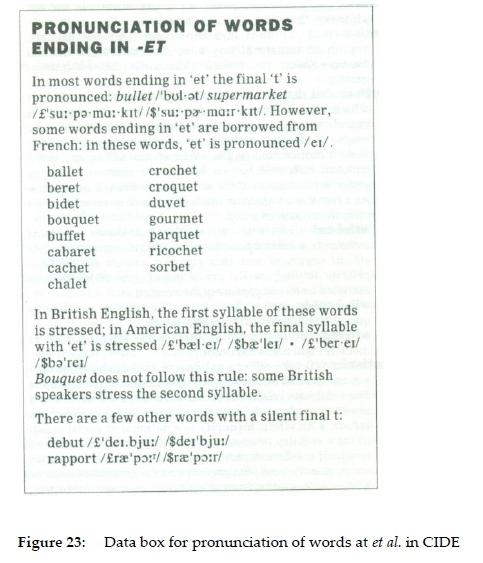

In figure 23 guidance in pronunciation of words ending in -et, presented in the partial article stretch between the articles of et al. and etc. in Cambridge International Dictionary of English (CIDE), is given by means of phonetic transcriptions and stress on syllables.

2.2.5 Data boxes indicating register

Data boxes on register deal with issues such as formal/informal and written versus spoken language.

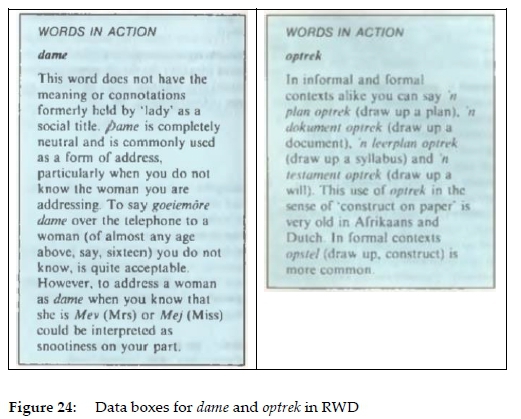

In figure 24 the data box reflects on change of meaning and connotations of the Afrikaans word dame compared to its English equivalent lady, and the contexts in which the use of this word is acceptable or not. The data box for optrek gives guidance on formal versus informal use as well as mentioning antiquation in certain senses.

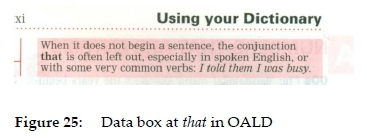

In figure 25, among other aspects, guidance is given on the use or omission of that in spoken language.

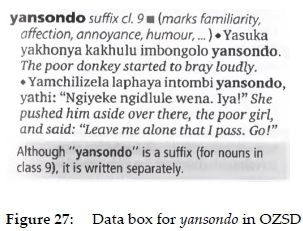

2.2.6 Data boxes dealing with spelling

This type of data boxes mainly deals with spelling variants, capitalization and word divisions.

In figure 26 the data box indicates that both spelling variants, i.e. China and Sjina, are acceptable in Afrikaans.

In figure 27 the data box deals with word division, i.e. that this nominal suffix is written separately.

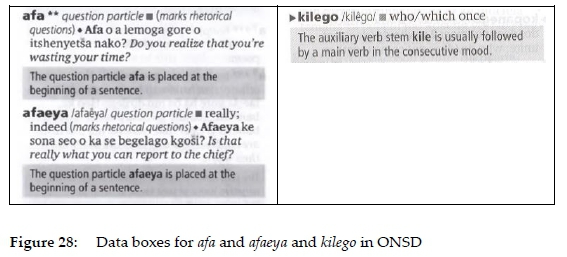

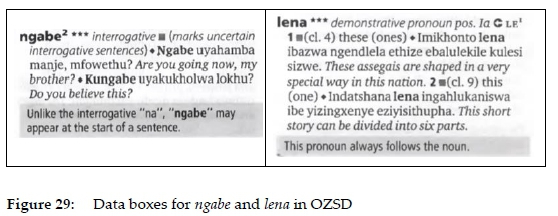

2.2.7 Data boxes indicating syntactic restrictions.

This type of data boxes mainly gives guidance on syntactic positions of words in sentences. Consider the following examples that are only relevant for Sepedi and isiZulu respectively in figures 28 and 29.

In Sepedi, the question particles afa and afaeya in contrast to the question particle na are restricted to the sentence-initial position. The auxiliary verb stem -kilego, which is in the relative mood is followed by the consecutive.

Consider also the data boxes given for the isiZulu words ngabe and lena in figure 29. These boxes indicate that na cannot be used sentence-initially but that it is permissible for ngabe and that the demonstrative pronoun lena has to be used post-nominally.

These are also good examples of a language specific issue for an African language not applicable to other members of the language family as mentioned above.

2.2.8 Data boxes dealing with obsolete, archaic and antiquating words

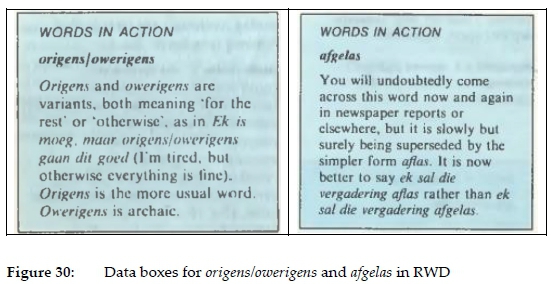

This type of data box has its finger on the pulse of a language in terms of language change. We regard "obsolete" and "archaic" in terms of MED as "no longer used" and "antiquating" as becoming obsolete, cf. figure 30.

In figure 30 it is indicated that although origens and owerigens have the same meaning, owerigens became archaic. The same holds true for afgelas in the sense of the intended cancellation of, e.g. a meeting, which is antiquating in favour of aflas.

2.3 A top tier of data boxes

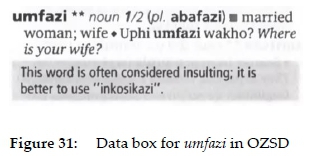

The proposed top tier of data boxes is distinguished for providing users with indispensable salient data of a serious nature regarding warnings, taboos and even illegal words. Even inside the category of top tier, a hierarchy can be distinguished ranging from mere recommendation in the sense of 'often considered insulting' to 'avoid using this word' to 'absolutely forbidden to use', i.e. of which the use is a criminal offence and punishable by law.

In figure 31 the data box at umfazi in OZSD is an example of a mere recommendation, i.e. where a better option is suggested.

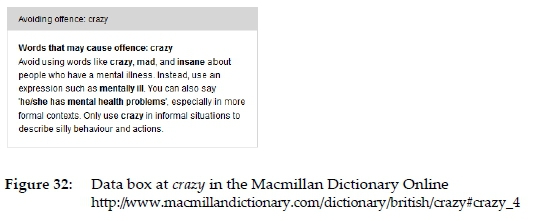

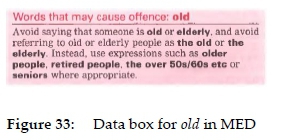

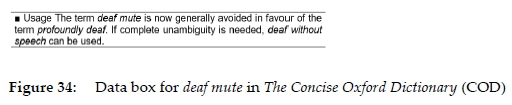

The data boxes in figures 32, 33 and 34 suggest a stronger condition, i.e. avoidance of the words crazy, old and deaf mute when referring to a person.

In the (South) African context a number of words, mostly words insulting black people, exist that are considered to be so offensive that it is illegal even to say or write these words. Aliases have to be used if reference to such words are absolutely necessary e.g. in media reports or the judicial system e.g. the k-word, n-word, h-word, m-word etc.

In 1994 the Bureau of the Woordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal (WAT) made a sincere attempt to address this issue by organising an international conference on the handling of insulting and sensitive lexical items in order to formulate a policy on the handling of such lexical items in the WAT. Harteveld and Van Niekerk (1995: 233) report on the outcome of this conference and state that the point of departure of the WAT was to fulfil its ideal of comprehensiveness but also to follow a policy of sensitive handling of lexical items.

Die Buro van die WAT wil in sy strewe na omvattendheid nie aandadig wees aan die vestiging of bestendiging van rassistiese leksikale items deur die opname daarvan in die WAT nie, maar hy het wel 'n verantwoordelikheid om gebruikers te waarsku teen die rassistiese aard van sekere leksikale items. Dit kan hy slegs doen as hy hierdie leksikale items identifiseer en op een of ander wyse onder die aandag van die gebruiker bring. (Harteveld and Van Niekerk 1995: 235) (The Bureau of the WAT, in its pursuit of comprehensiveness, does not want to be complicit in the establishment or perpetuation of racist lexical items by including them in the WAT, but it does have a responsibility to warn users against the racist nature of certain lexical. items. He can only do this and if he identifies these lexical items and somehow brings them to the attention of the user.)

The dilemma of lexicographers is clear - on the one hand they do not want to contribute to the use of offensive lexical items by including them in the dictionary but on the other hand feel a strong responsibility to reflect the lexicon of the specific language and, especially, to warn their users against the use of offensive terms.

3. A summary of data box types in RWD, ONSD and OZSD

The final section of this article reflects a survey that was made of all data boxes in the Afrikaans to English side of RWD as well as the Sepedi to English and English to Sepedi side in ONSD and the isiZulu to English and English to isiZulu sides of OZSD.

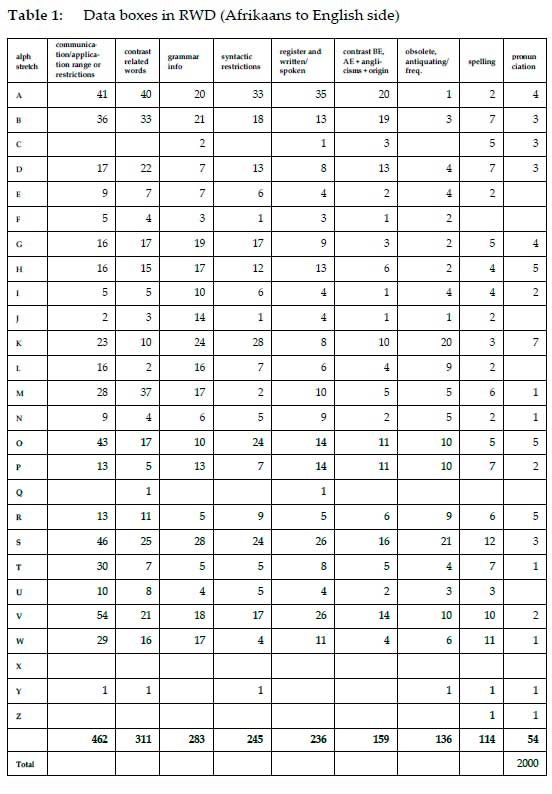

In the Afrikaans to English side of RWD no less than 2,000 data boxes were provided as broken down in descending order in terms of type and given per alphabetical stretch in table 1.

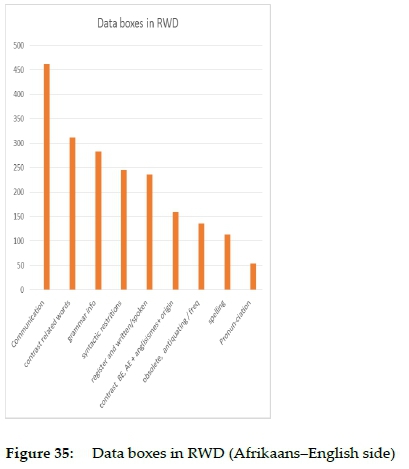

From table 1 and figure 35 it is clear that the top five types of data boxes deal with issues related to range of application, restrictions, contrast, grammar, syntactic restriction and register. The 2,000 data boxes presented in 639 pages give an average of approximately 3 boxes per page.

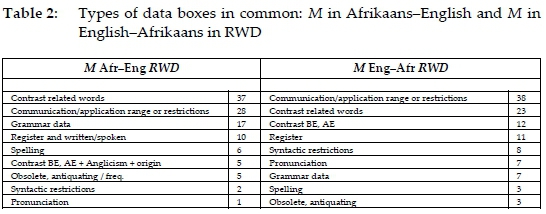

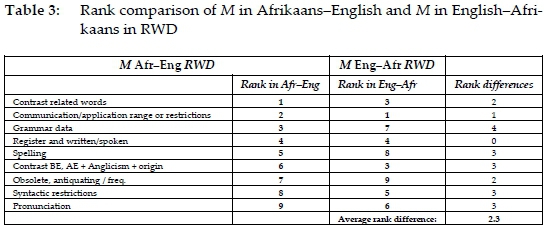

Consider the content summary of data boxes in the alphabetical stretches for M in RWD (Gouws and Prinsloo 2010: 507) in table 2 with rank comparisons of these categories between the two sides in table 3.

From the rank comparisons in table 3 it is clear that the average rank difference is very small indicating similarity in the types and contents of data boxes in the Afrikaans-English and English-Afrikaans sides.

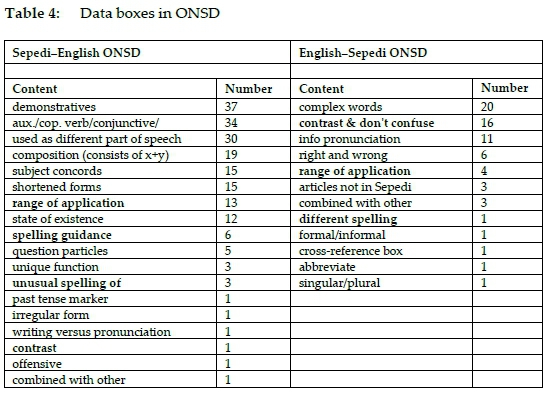

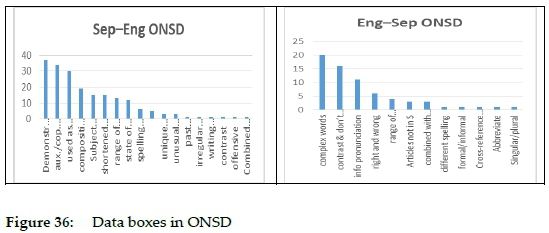

The types of data boxes used in the Sepedi to English and English to Sepedi sides of ONSD are given in table 4 and graphically illustrated in figure 36. The data types indicated in boldface in table 4 indicate the types of data boxes that occur on both sides of the dictionary.

Most of the data boxes in the Sepedi to English side give guidance on the nature and use of demonstratives while most data boxes on the English to Sepedi side deal with complex words.

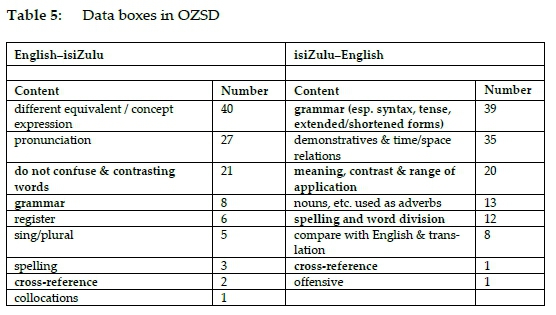

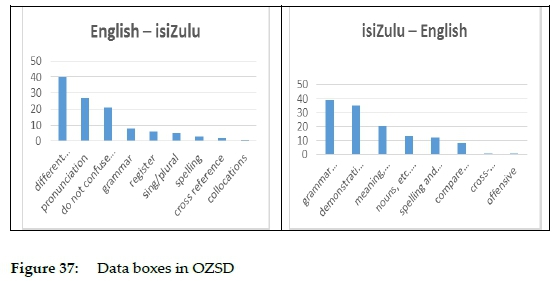

Data boxes giving guidance on equivalents and ways to express concepts top the list of data box contents in the English to isiZulu side and data boxes dealing with grammatical issues pertaining to syntax, tense and extended or shortened forms being the most frequent in the isiZulu to English side, cf. table 5 and figure 37.

4. Conclusion

In Part 1 (this volume) the focus was on data boxes as text constituents. This article focused on the types and contents of data boxes and in Part 3 guidance will be offered for prospective compilers on data boxes of the future. In Part 2 it was emphasized that no structural planning of data boxes nor specific user-guidance on the nature and use of data boxes or distinction between different types of data boxes was observed in the dictionaries studied. Data boxes are presented in a haphazard way without any clear treatment convention and conformity. What lies beyond doubt, however, is that all the sources quoted above express a need for a lexicographic strategy to help users to avoid common mistakes, get additional information, learn more about the word and its origin, etc. The focus was on the analysis of data boxes in existing dictionaries to determine the nature of data presented in boxes and a three-part hierarchy was suggested. The first type was labelled as the mere bringing together and highlighting of aspects such as menus for the different senses of the word and lists of typical collocations. The second type, a much larger and more diverse category dealt with data boxes providing salient information which falls outside the default lexicographic treatment devices such as paraphrase of meaning, translation equivalent paradigms and examples of use. The final category represents the top tier in the proposed hierarchy namely data boxes for restricted words in terms of warnings and alerts to their use or avoidance.

Acknowledgement

This research is supported in part by the South African Centre for Digital Language Resources (SADiLaR). Findings and conclusions are those of the authors.

References

Dictionaries

CALD = Mcintosh, Colin (Ed.). 2013. Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary. 4th edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

CD = Cambridge Dictionary. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/. [Accessed 1 August 2020.]

CIDE = Procter, P. (Ed.). 1995. Cambridge International Dictionary of English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

COD = Thompson, Della (Ed.). 1995. The Concise Oxford Dictionary. 9th Edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

LDOCE = Procter, P. (Ed.). 1978. Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English. Harlow: Longman. MED = Rundell, M. (Ed.). 2002. Macmillan English Dictionary for Advanced Learners. Oxford: Macmillan Education.

MW = Merriam Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com. [Accessed 1 August 2020.]

OALD = Turnbull, J. (Ed.). 2010. Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary of Current English. 8th edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Accessed 24 December 2013.]

OALDC = Crowther, Jonathan (Ed.). 1995. Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary of Current English. 5th edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

ODE = Oxford Dictionary of English. http://www.oxfordreference.com.

OMD = Macmillan Dictionary - British English Edition. https://www.macmillandictionary.com/dictionary/british/. [Accessed 2 August 2020.]

ONSD = De Schryver, G.-M. (Ed.). 2007. Oxford Bilingual School Dictionary: Northern Sotho and English / Pukuntsu ya Polelopedi ya Sekolo: Sesotho sa Leboa le Seisimane. E gatisitswe ke Oxford. Cape Town: Oxford University Press Southern Africa.

OZSD = De Schryver, G.-M. (Ed.). 2010. Oxford Bilingual School Dictionary: Zulu and English / Isichazamazwi Sesikole Esinezilimi Ezimbili: IsiZulu NesiNgisi, Esishicilelwe abakwa-Oxford. Cape Town: Oxford University Press Southern Africa.

PMD = Pharos Major Dictionary. Eksteen, L.C. (Ed.). 1997. Groot Woordeboek Afrikaans-Engels/Engels-Afrikaans / Major Dictionary Afrikaans-English/English-Afrikaans. 14th expanded edition. Cape Town: Pharos.

RWD = Grobbelaar, P. et al. (Eds.). 1987. Reader's Digest Afrikaans-Engelse Woordeboek /English-Afrikaans Dictionary. Cape Town: The Reader's Digest Association, South Africa (Pty) Ltd.

Other references

Gouws, R.H. and D.J. Prinsloo. 2005. Principles and Practice of South African Lexicography. Stellenbosch: SUN PReSS. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. and D.J. Prinsloo. 2010. Thinking out of the Box - Perspectives on the Use of Lexicographic Text Boxes. Dykstra, A. and T. Schoonheim (Eds.). 2010. Proceedings of the XIV Euralex International Congress, Leeuwarden, 6-10 July 2010: 501-511. Leeuwarden: Fryske Akademy. [ Links ]

Harteveld, P. and A.E. van Niekerk. 1995. Beleid vir die hantering van beledigende en sensitiewe leksikale items in die Woordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal (as formulated by the authors). Lexikos 5: 232-248. [ Links ]

* This is the second in a series of three articles dealing with various aspects of lexicographic data boxes.