Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Lexikos

versão On-line ISSN 2224-0039

versão impressa ISSN 1684-4904

Lexikos vol.31 Stellenbosch 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.5788/31-1-1651

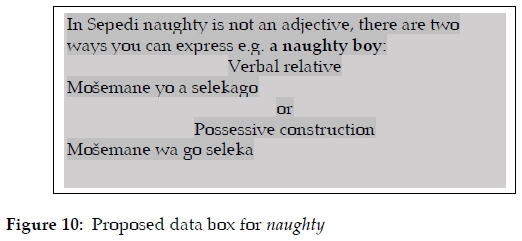

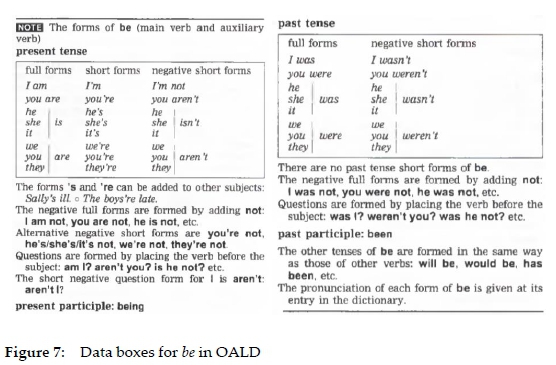

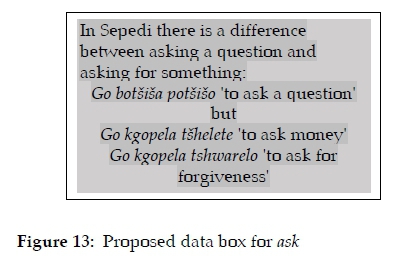

5. Data boxes as dictionary entries

5.1 Data boxes and addressing relations

The addressing structure and various addressing relations in dictionaries are important to identify the scope of each item in a dictionary article and the target of its treatment. According to Hausmann and Wiegand (1989: 328) a treatment unit results "when a form mentioned and information relating to that form are brought together. The relation of form and information is that of topic and comment." The "way in which a form and information relating to that form are brought together is the addressing procedure." Each information item is addressed to a form that is known as its address.

Data boxes are functional constituents of dictionaries and should not be employed as mere procedures of lexicographic face-lifting. They are included in dictionaries as part of the lexicographic treatment procedures. When allocating a data box to a specific search zone cognizance needs to be taken of the specific treatment contributed by the data box. Dictionary users should know exactly what constitutes both the address and the addressing relation of each data box.

To ensure an optimal comprehension of the relevant addressing relation, it is important that the notion of addressing has to be employed in an unambiguous way. In this article the procedures of addressing as discussed in Gouws (2014) will be employed. Wiegand and Gouws (2013) restrict addressing to relations within condensed articles where items display the addressing relations. Wiegand and Gouws (2013: 273) say that there are no addressing relations in non-condensed dictionary articles or in other non-condensed accessible entries. This implies that an item like a lemma sign cannot be addressed by an item text, even if the item text contributes to the treatment of the lemma. In contrast to this approach, Gouws (2014: 183) expands the application of the notion of addressing. The term addressing is used to incorporate both primary addressing which is the traditional procedure prevailing in condensed articles, and secondary addressing to go beyond textual condensation and item status as prerequisites for addressed entries. In accordance with this approach both items and item texts can participate in procedures of addressing. The addressing element and its address do not have to be in the same dictionary article and addressing can occur between different types of constituents of a word list, e.g. also between a phased-in inner text and an item in a dictionary article.

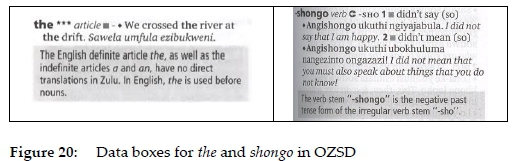

5.2 The position for data boxes and the different types of data box entries

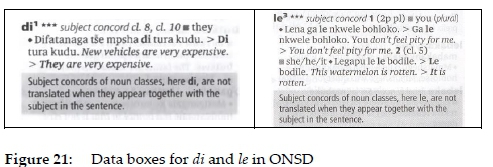

In accordance with the data distribution structure of a specific dictionary the lexicographer has to allocate data-carrying segments to the different search positions in the dictionary. Where a dictionary displays a frame structure the positioning of data in the articles of the word list will be complemented by text constituents or other entries presented in the front and/or back matter sections of that dictionary. As a carrier of text types a dictionary could also include outer texts in its middle matter section.

Dictionaries have different search positions, traditionally ranging from a search zone within a dictionary article to the article as search area and the word list, the largest search position, as search field, cf. Wiegand, Beer and Gouws (2013: 63). Gouws (2018: 228) argued in favour of a further and more comprehensive search position, i.e. the search region. This search position is constituted by all the textual components of a dictionary as a text compound. For a single volume dictionary this is the most comprehensive search position. Although the outer texts of the front and back matter sections of a dictionary fall outside the domain of the search field they are part of the search region of a dictionary. Data boxes typically occur within a word list, that is a search field, of a dictionary. This could be within the central and only word list which is the most frequent occurrence of data boxes, or within any other word list that is part of a word list series of a given dictionary. Looking at data boxes in this article, the focus will only be on those data boxes occurring in a word list, i.e. within the search field of dictionaries. Data boxes in outer texts will not be discussed.

As entries in a search field the status of all data boxes is not the same. Data boxes could be phased-in inner texts, article-internal item texts or mere items occupying a search zone in a dictionary article. These different types of data boxes will be discussed in the subsequent sections.

5.3 Expanded word lists

The data distribution structure of any dictionary determines the way in which the lemmata presenting the macrostructural coverage of the dictionary have to be ordered within the word list of that dictionary. Whether it is a straight alphabetical ordering or an ordering with sinuous lemma files that enables the use of niched and nested lemmata, a word list will consist of a number of article stretches that accommodate articles with the lemmata as their guiding elements.

When planning the data distribution structure of a dictionary lexicographers need to make a decision regarding the type of word list the dictionary will display. This is determined by specific features of the nature of data allocated to the word list. In this regard a distinction is made between a single word list and an expanded word list, cf. Bergenholtz, Tarp and Wiegand (1999: 1766). A single word list contains article stretches but no inserts or phased-in inner texts, whereas an expanded word list also contains article stretches as well as inserts and/or phased-in inner texts. These inserts and phased-in inner texts split sequences of articles within partial article stretches. Therefore an expanded word list is also known as a split word list.

The distinction between inserts and phased-in inner texts is significant for the identification of data boxes.

5.3.1 Distinguishing between inserts and phased-in inner texts

5.3.1.1 Inserts

According to the Wörterbuch zur Lexikographie und Wörterbuchforschung/Dictionary of Lexicography and Dictionary Research (Wiegand et al. 2017), (henceforth abbreviated as WLWF) an insert is a text or text part that is inserted into the word list of a dictionary. It is an immediate constituent of the dictionary as a text compound. Inserts often are sections of photos, inserted between two article stretches or between two pages of an article stretch. In the Merriam-Webster's Advanced Learner's English Dictionary (Perrault 2008), (henceforth abbreviated as MWALD), the article stretch of the letter M is split between the lemmata mascot and masculine by an insert titled Color Art. This insert, with its own table of contents, contains pictures of themes like colours, vegetables, landscapes, gems and jewellery and clothing. These pictures do not adhere to the alphabetical ordering within the article stretch and although it splits the word list this insert is not an immediate constituent of either the specific article stretch or the word list. It is an immediate constituent of the dictionary as text compound and carrier of text types. Consequently inserts cannot be regarded as a type of data box or the type of data box discussed in this article.

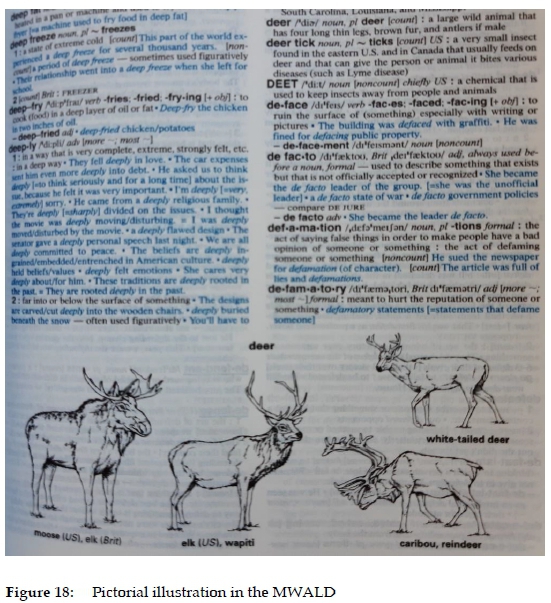

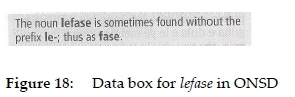

The form of inserts sometimes resemble that of data boxes, e.g. the section on birds in an insert from the MWALD contains pictures of a variety of birds and the data box occurring in the article of the lemma deer, cf. figure 18 in paragraph 5.5.2.1, contains a number of pictures of different types of deer. Although both these text constituents are carriers of pictures, the insert is a different type of lexicographic text and will not be discussed any further in this article.

5.3.1.2 Phased-in inner texts

Phased-in inner texts occur in expanded word lists where they split the article stretches, resulting in internally expanded article stretches (Bergenholtz, Tarp and Wiegand 1999: 1766). The phased-in inner texts typically contain data relevant to a lemma in close proximity within the same article stretch and often also to other lemmata occurring in remote articles. The data in the phased-in inner texts can also have a more general relevance to the specific lemma or might link thematically with it. Phased-in inner texts often have an inner text title that can concur, but not necessarily, with the lemma of an article in its proximity. This title could also identify the more general nature of the data in the specific text. These texts are usually typographically distinguishable from default articles as constituents of a word list by being framed or presented with a coloured background. Examples will be provided in a subsequent section of this article.

Article-internal data boxes and phased-in inner texts sometimes show strong resemblances but the nature of a specific box as a text constituent of the word list determines whether it has to be regarded as an article-internal box or a box presented as phased-in inner text.

5.4 Article-internal data boxes

5.4.1 Items and item texts

One of the most frequent occurrences of data boxes is within dictionary articles. As constituents of articles data boxes do not form part of the obligatory micro-structure but rather enrich the obligatory microstructure, resulting in an extended obligatory microstructure. Data boxes in dictionary articles mostly contain text data but they can also display non-textual data. Data boxes are not default entries in any article but their use can be regarded as an extended treatment procedure. They can either contain items or item texts. Wiegand and Smit (2013: 153) distinguish as follows between items and item texts:

An item is a functional text segment without the status of a sentence but with the status of a text segment which is given as a discernible item form assigned with at least one genuine function, the latter being precisely such that a user can obtain knowledge about the item's subject as lexicographical information.

An item text is a functional text segment with item function and text constituent status exhibiting a complete and distinct natural-language syntactical structure and consisting of at least one sentence.

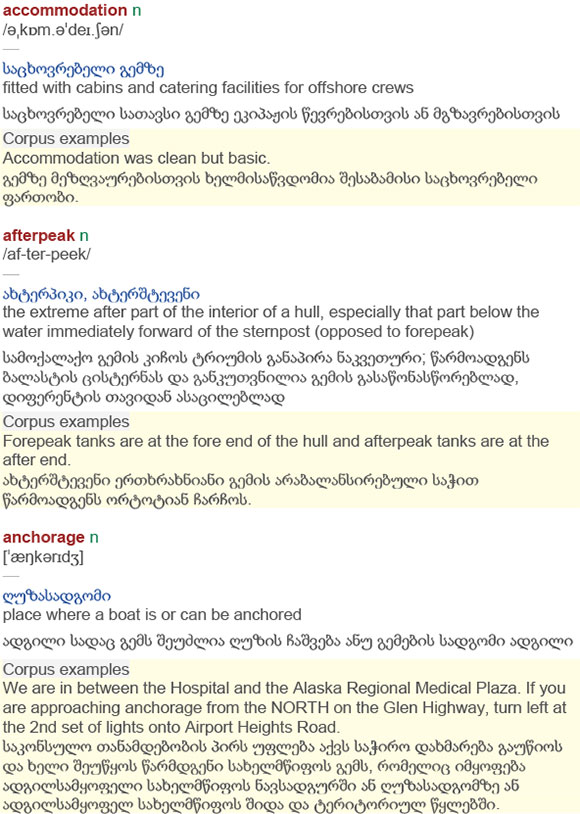

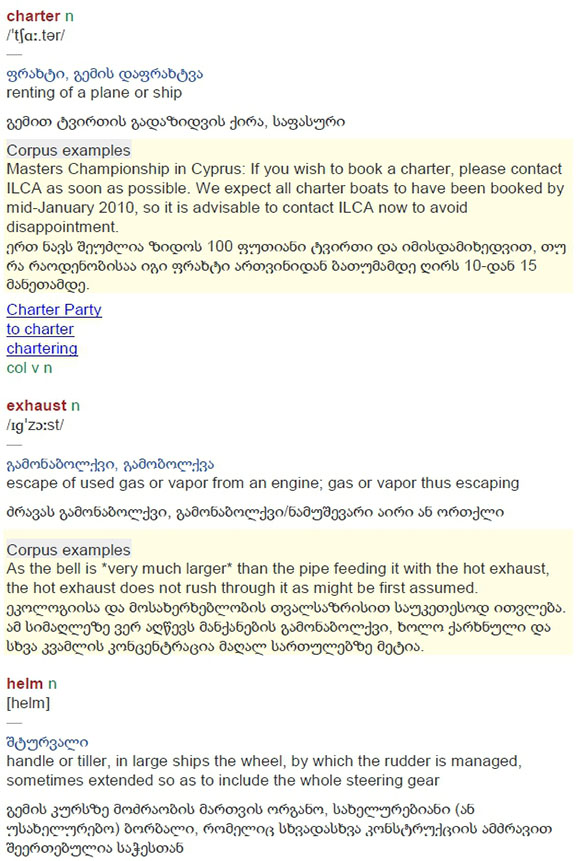

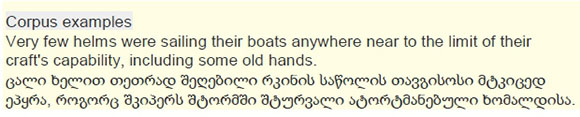

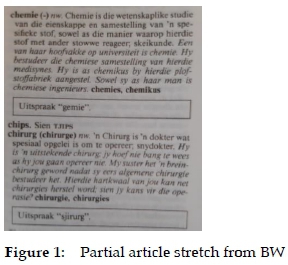

As constituents of dictionary articles data boxes may contain data presented in either condensed or non-condensed format. The articles in figure 1, a partial article stretch from the monolingual Afrikaans learner's dictionary Basiswoordeboek van Afrikaans (Gouws et al. 1994), (henceforth abbreviated as BW) contain two data boxes with items giving the pronunciation of the word represented by the lemma of the specific article. This dictionary only gives pronunciation guidance for a limited number of selected lemmata. It is not part of the obligatory microstructure and when pronunciation guidance is regarded as necessary, it is presented in a data box accommodated in the final slot of the article. The entries "Uitspraak 'gemie'" (= Pronunciation 'gemie') and "Uitspraak 'sjirurg'" (= Pronunciation 'sjirurg') are condensed forms and thus items.

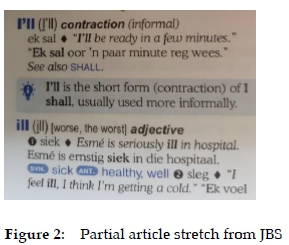

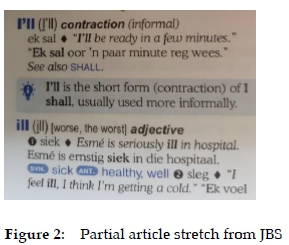

The data box in figure 2 from the Junior Tweetalige Skoolwoordeboek/Junior Bilingual School Dictionary, (Stoman et al. 2018), (henceforth abbreviated as JBS) contains a sentence which is an entry given in non-condensed form. This entry therefore is an item text.

Whether entries are items or item texts may have implications for the addressing relations in an article. This will be discussed in a further section of this article.

5.4.2 Positioning data boxes within dictionary articles

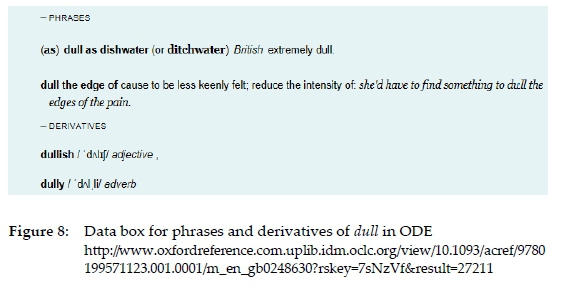

Data boxes are functional dictionary entries because they contribute to achieving the genuine purpose of the dictionary in which they occur. That implies that from the data on offer in a data box users must be able to retrieve information that can assist them in finding a solution to the problem that initiated the specific dictionary consultation procedure. Because data boxes result from extended treatment procedures and are usually not entries belonging to the obligatory microstructure of a dictionary, users will not know beforehand whether an article contains a data box. That is why it is important that these boxes need to be clearly marked as framed or coloured text constituents. Dictionary articles have no fixed slot reserved for data boxes. When planning the data distribution structure of a dictionary lexicographer's need to decide on the slots in dictionary articles that could accommodate search zones populated by data boxes. Data boxes could be placed in different text positions in dictionaries, cf. Taljard et al. (2014: 698). They could be included within the comment on form or comment on semantics or in an alternative position, e.g. as precomment or postcomment.

5.4.2.1 Data boxes at the end of an article

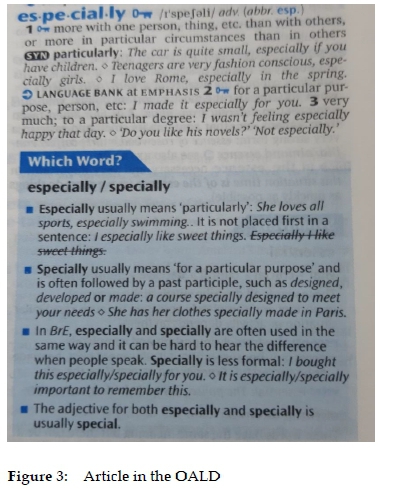

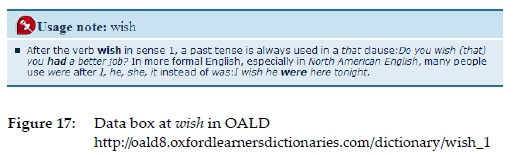

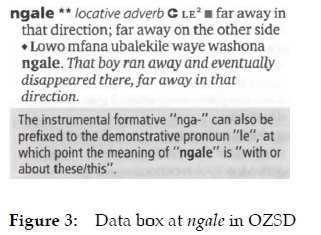

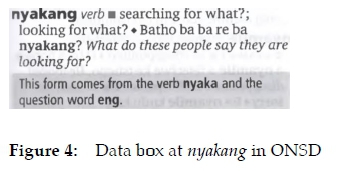

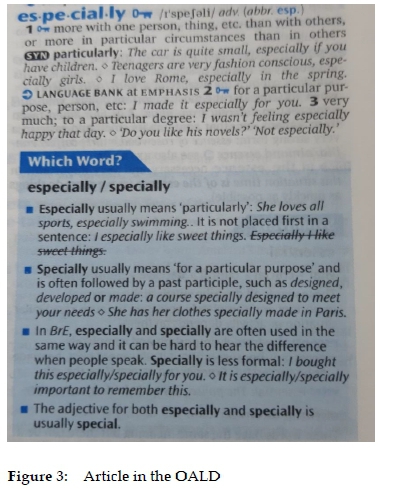

One of the most typical positions allocated to data boxes, cf. Gouws and Prinsloo (2010), is a slot at the end of the article. In such a position the data box often falls beyond the scope of either the comment on form or the comment on semantics. As postcomment the data box is in a position of salience - further accentuated by its frame or colouring. Figure 3 shows the article of the lemma sign especially in the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary of Current English (Turnbull 2010), (henceforth abbreviated as OALD):

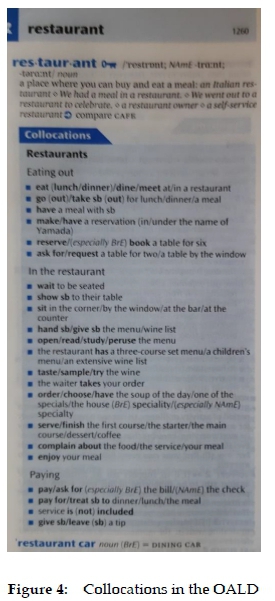

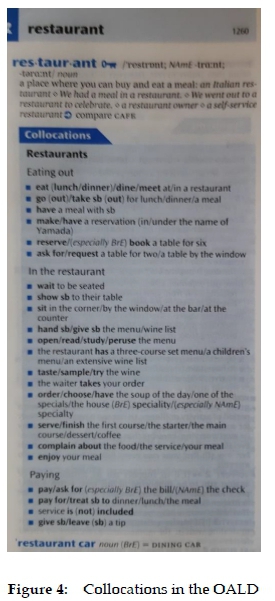

The obligatory microstructure ends with the items in the third subcomment on semantics. The lexicographers have felt the need to present the users with additional guidance regarding the use of the words especially and specially. The data box containing this data has the title "Which Word?" and is presented after the comment on semantics as a postcomment to the article. Another example of a box presented as postcomment in the same dictionary can be found in the article of the lemma sign restaurant, figure 4. A type of data box frequently given in this dictionary contains collocations, but not necessarily collocations in which the word represented by the lemma functions as either base or collocator, but rather collocations applicable in the semantic domain of the word represented by the lemma sign. The user gets assistance regarding typical collocations used when dining in a restaurant:

The OALD presents the entries in data boxes against a blue background. These data boxes can easily be identified by the users of this dictionary.

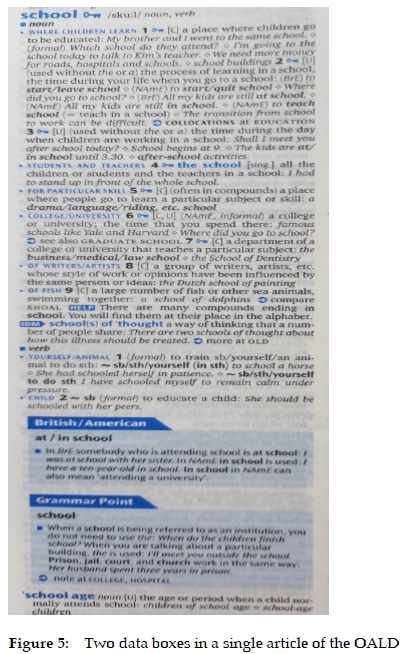

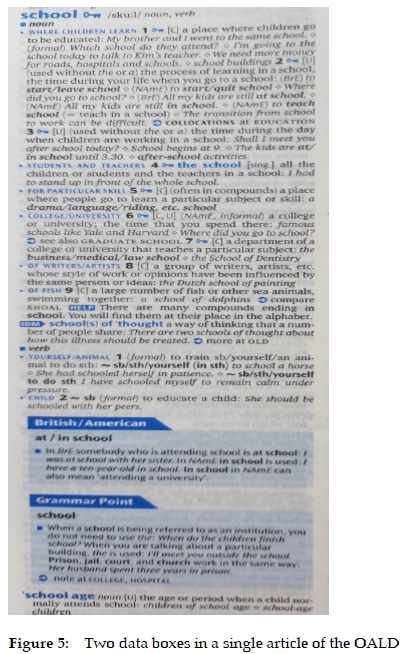

There is no restriction on the number of data boxes per article, but lexicographers need to be careful not to have a data box overload that could diminish the emphasis on these boxes. An inflation of data boxes should therefore be avoided, but even more than one clearly marked data box per article should still be in order, as seen in figure 5, the article of the lemma sign school in the OALD. The two boxes "British/American" and "Grammar Point" are clearly identifiable and can enhance the nature and extent of the lexicographic treatment in this article.

Where a data box is presented as postcomment in the article of a lemma representing a polysemous lexical item it is not always clear whether the treatment presented in the box is directed at only one or more senses or at all the senses of the word. This problem will be elaborated on in section 5.4.2.4.

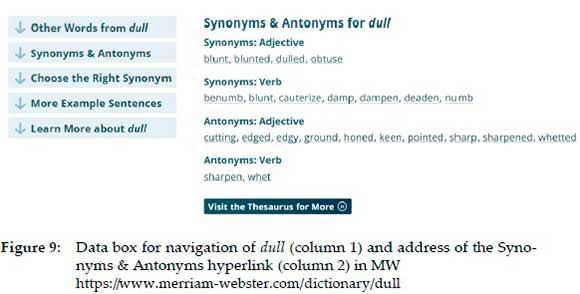

5.4.2.2 Data boxes at the beginning of the article

The lemma sign of an article is part of the main outer access structure of the dictionary and a guiding element of the specific article. Irrespective of the type of information a user wants to retrieve from a dictionary article as search area the access to that item, especially in a printed dictionary, proceeds via the lemma sign onto the search paths of the inner access structure. Items positioned in search zones in close proximity of the lemma are in salient positions. The framed or coloured appearance of data boxes adds focus to their occurrence as text constituents of an article and if such a box is awarded a position close to the lemma sign it further elevates the salience of the data in the box.

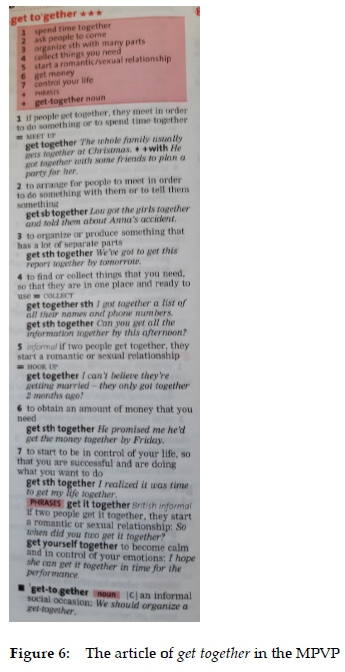

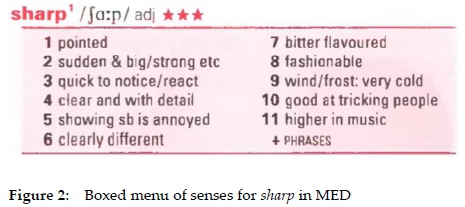

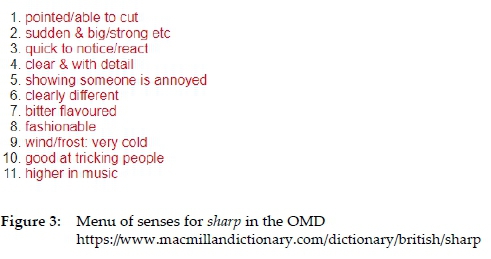

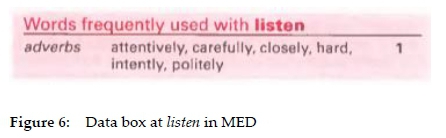

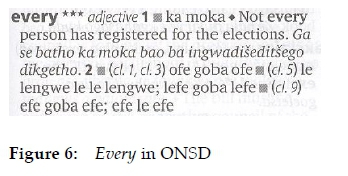

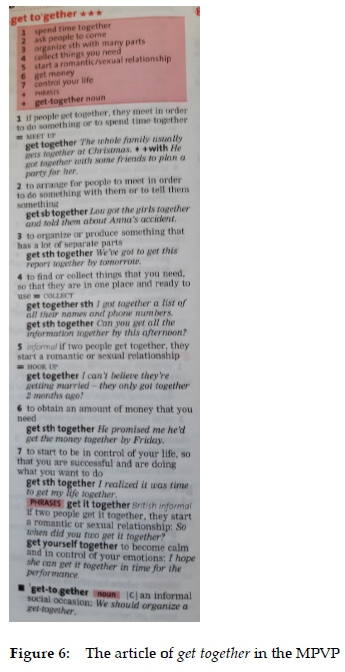

The Macmillan Phrasal Verbs Plus (Rundell 2005), (henceforth abbreviated as MPVP) uses data boxes in a slot close to the beginning of an article, to provide an overview of the senses where the phrasal verb represented by the lemma sign has five or more than five senses. This box differs from other boxes because it does not contain the kind of data typically allocated to data boxes. It displays items conveying the menu of the comment on semantics and they function as navigational entries in this article. Alternative strategies for the provision of such navigational guidance could for instance be shortcuts, signposts and guidewords and will be discussed in detail in Part 2 of this series. The box as seen in figure 6 functions in such an article as a precomment.

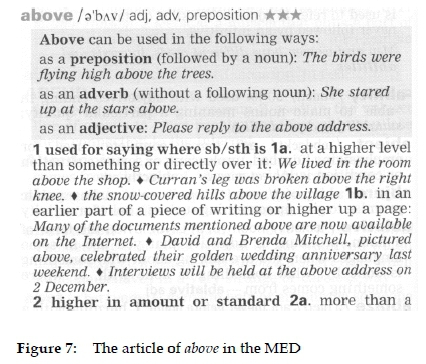

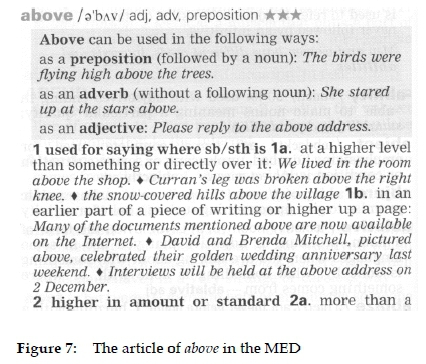

Data boxes are also included as precomments of articles in the Macmillan English Dictionary (Rundell 2007), (henceforth abbreviated as MED). In figure 7, the article of the lemma sign above, the data box contains data regarding the use of the word above in its occurrence in different parts of speech. It makes the user aware of the differences between these uses.

To ensure that the target user of this learner's dictionary will focus on the differences between the uses of the word, this data can at best be presented in a precomment instead of being subsumed under the cotextual items in different comments or subcomments on semantics of one of the three partial articles of this twofold complex dictionary article, cf. Wiegand and Gouws (2011: 242).

Because the beginning of an article is a significant position of salience in a dictionary article lexicographers should carefully consider the type of data boxes to include in that search zone.

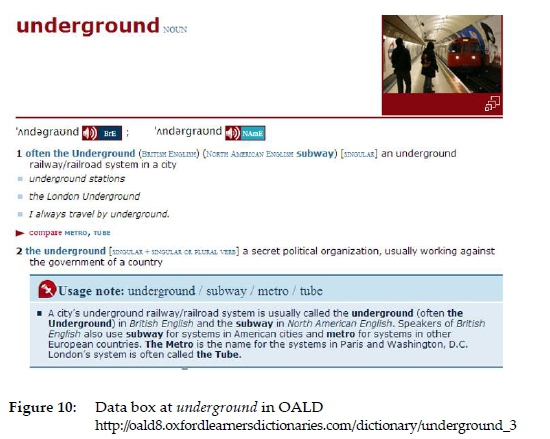

5.4.2.3 Data boxes as article windows

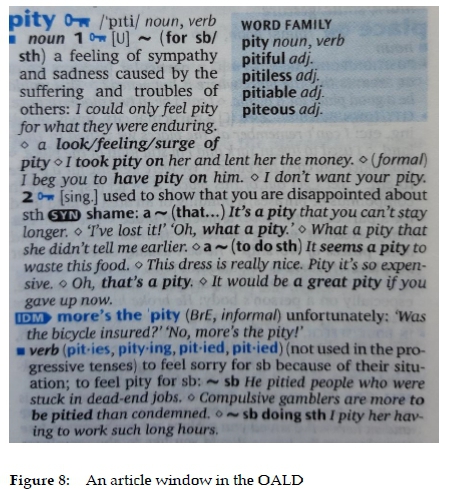

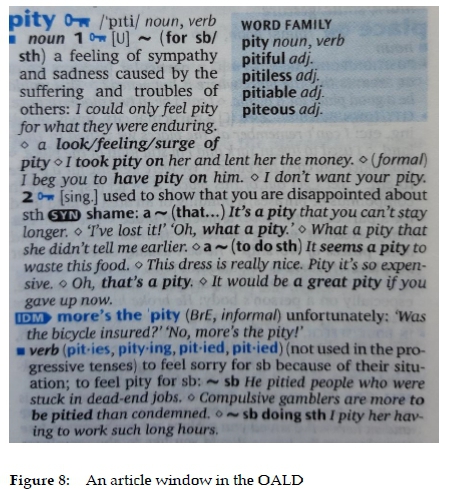

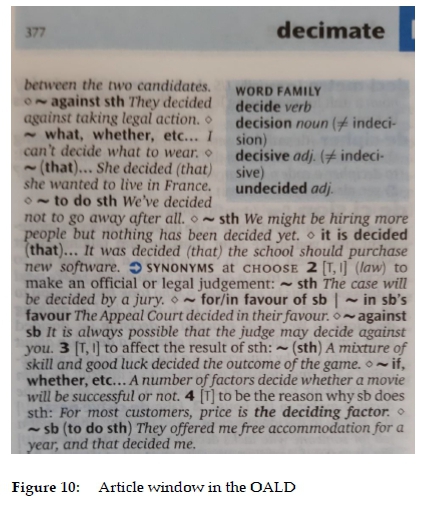

Lexicographers often have innovative ideas regarding the way of presenting data in their dictionaries. In the OALD several types of data boxes are used, with some types reserved for specific types of data. An article window is a type of data box reserved for a single type of data, i.e. word families, as seen in figure 8:

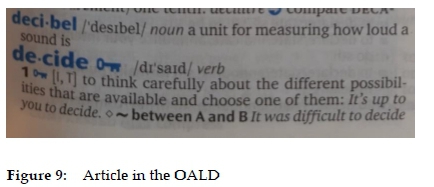

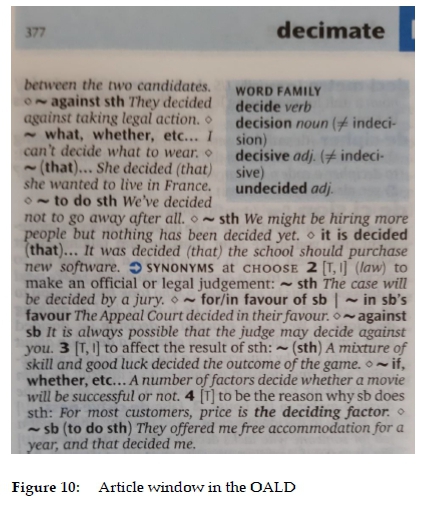

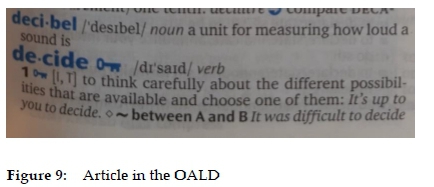

In the front matter text "Key to dictionary entries" it is said that: "Word families show words related to the headword." Although articles could in principle have windows in different article positions, e.g. top right, top centre, top left, middle right, middle centre, middle left, bottom right, bottom centre and bottom left, the OALD primarily uses the top right corner for its window data boxes. However, the layout of a dictionary article on the page could also have an influence on the position of the window. The editors of the OALD are consistent in always placing data boxes presented in article windows in the top right corner of a text block, albeit not necessarily of the article. Where an article commences at the bottom of a column there could be a lack of space for a window in the top right corner of the article, as seen in figure 9.

However, the window is then positioned in the top right corner of the text block, containing the remainder of the article, that starts in a new column, as seen in figure 10.

Technically such a window occupies the right centre of the article. From a layout perspective it could be argued that the OALD always presents its windowed data boxes in the top right corner of a text block, preferably but not always the top right corner of the article.

A brief identification of word families as found in the article windows can be valuable assistance to the target users of this dictionary. Users should be aware of this assistance but unfortunately the OALD does not provide an outer text in the front matter section with a list of articles that contain these windows. In spite of the focus that a data box puts on this data, there is no defined search path besides the main alphabetical outer access structure to guide users to these articles that contain article windows. This lack of predictable access impedes the added value of these article windows.

5.4.2.4 Data boxes within a comment of an article

Whether an article-internal data box contains an item or an item text, the contents of that data box is presented as part of a treatment procedure. This procedure is directed at one or more specific treatment units that constitute the address within this procedure of addressing. The positioning of article-internal data boxes directly reflects the relevant addressing relations in which data boxes can become involved.

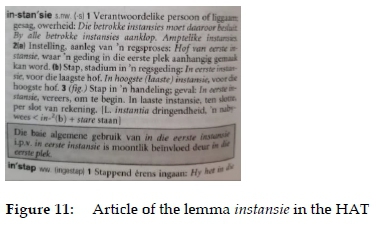

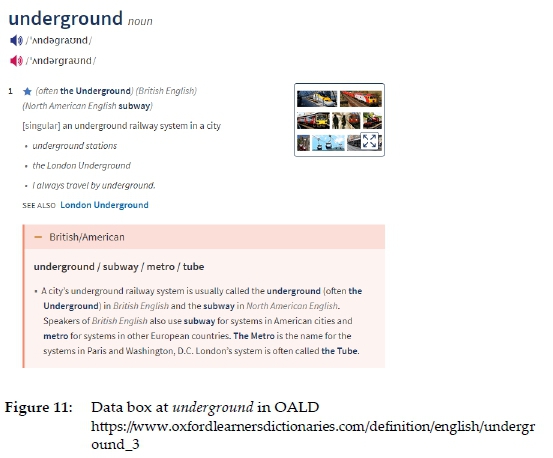

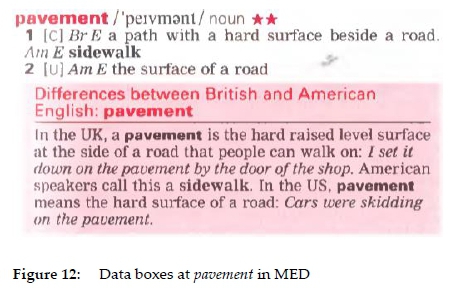

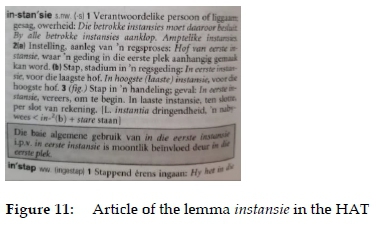

Although lemmatic addressing, i.e. with the lemma as address, is the most frequently used addressing procedure in dictionaries, other types of addressing also prevail, especially non-lemmatic addressing. Various aspects of addressing are dealt with in Hausmann and Wiegand (1989), Louw and Gouws (1996), Gouws and Prinsloo (2005), Wiegand (2006; 2011) and Gouws (2014). Lexicographers utilise data boxes to emphasise certain entries not accounted for by items in search zones of the obligatory microstructure of a dictionary. These items or item texts do not always have the lemma as address, but often occur within one of the comments of an article, especially the comment on semantics or a subcomment on semantics, where they participate in relations of non-lemmatic addressing. A less optimal article-internal positioning of a box of which the entry or entries are not addressed at all the senses of the word represented by the lemma sign of the article may diminish the added value the data box is supposed to have. In figure 11 from the Handwoordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal (HAT) (Odendal and Gouws 2005) the data box is included as postcomment at the end of the article. The contents of the box only applies to the use of the word instansie in its second and third senses. From this presentation it is not clear that the box is not addressed at the first sense.

Figure 12 is a partial article of the lemma open2from the Longman Exams Dictionary (Summers 2006), (henceforth abbreviated as LED). This article contains two data boxes, so-called study notes. Both these data boxes are presented within single subcomments on semantics for the first and the second sense of the polysemous word open. By positioning them there the lexicographer ensures that the user can know what the exact address of the data box is:

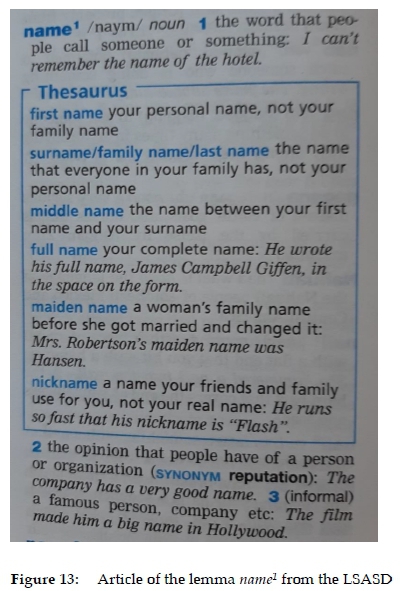

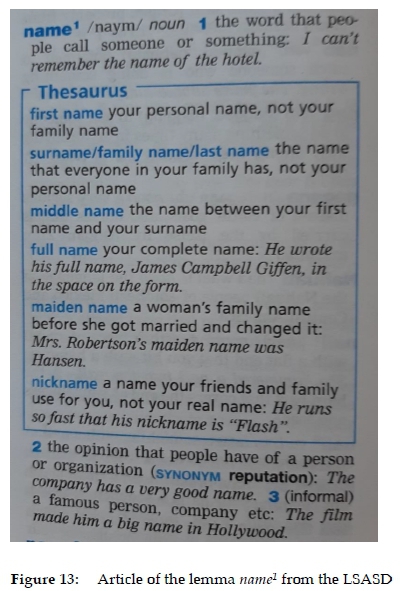

In the Longman South African School Dictionary (Bullon et al. 2007, (henceforth abbreviated as LSASD)) the article of the lemma sign name1has three subcomments on semantics. The thesaurus data box is positioned at the end of the first subcomment on semantics. The thesaurus guidance in the data box is only applicable to the first sense of the word name.

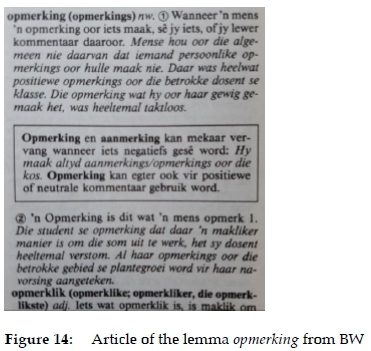

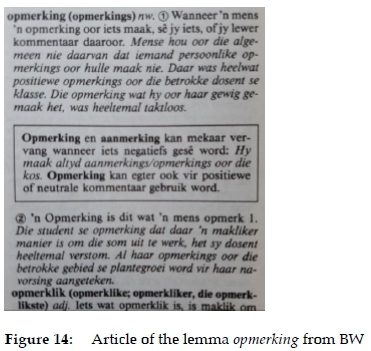

Figure 14 from BW shows a data box that only has the first sense of the word opmerking as its address. Such a procedure of immediate addressing is to the benefit of the target user of the dictionary and demands less dictionary using skills compared to correctly interpreting the address of a data box that is not positioned in close vicinity to its address, even if the user was able to identify the appropriate sense:

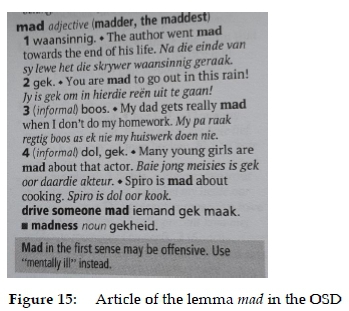

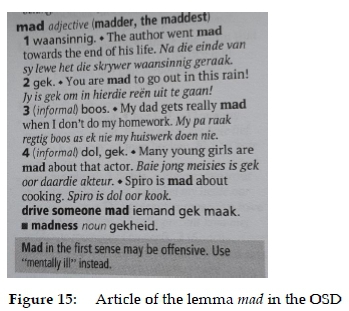

Where the treatment in a data box is directed at only one of the senses of a polysemous word or at only one of the items in the article and the data box is not positioned in such a way that an immediate addressing relation is possible, the lexicographer should clearly indicate what the address of the contents of the data box is. Such an approach is seen in figure 15, the article of the lemma mad in the Oxford Afrikaans-Engels/English-Afrikaans Skoolwoordeboek/School Dictionary (Pheiffer 2007), (henceforth abbreviated as OSD):

In this article with its four subcomments on semantics, the data box has been included as postcomment but it is clearly stated that it is addressed at the first sense.

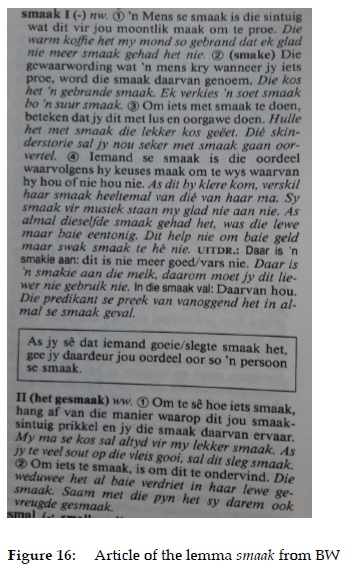

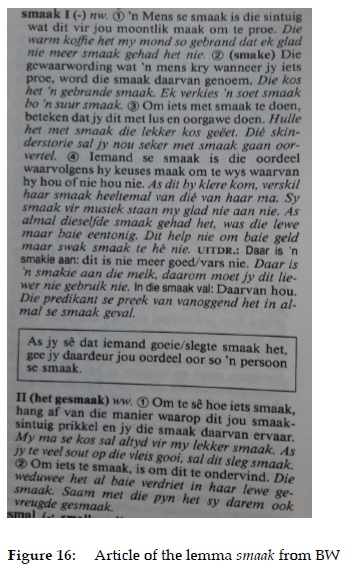

Where a word can be used in more than one part of speech, the lexicographic treatment typically results in a complex article with a partial article for the occurrence of each of these parts of speech (Wiegand and Gouws 2011: 243). Data boxes could then be positioned in a search zone of one of the partial articles so that the other part of speech occurrence of the word falls beyond the scope of the data box. This can be seen in figure 16 from BW where the data box is positioned at the end of the first partial article of the article with the lemma smaak as guiding element.

5.5 Phased-in inner texts as data boxes

5.5.1 Article-external text boxes

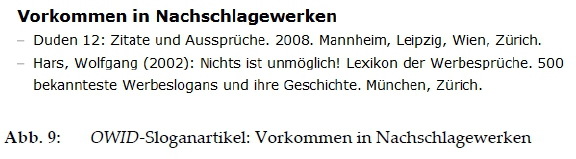

Data boxes can also be accommodated in the word list of dictionaries as phased-in inner texts. These data boxes are immediate constituents of the article stretches of the word list and function as article-external data carriers. Data boxes presented as phased-in inner texts typically have a connection with a lemma that is the guiding element of an article occurring in the specific article stretch into which the data box is phased in. These data boxes can be items or item texts and participate in either primary or secondary addressing relations. In addition to having the lemma that is in close proximity as address, these data boxes can also participate in relations of remote addressing, cf. Louw and Gouws (1996), where one or more lemmata in the same or often in other article stretches can be the address. As is the case with article-internal text boxes, different types of data can be presented in these data boxes, cf. Wiegand et al. (2017: 140-144 (WLWF)).

Phased-in inner texts could be constituents of the word list of a dictionary with a single alphabetical macrostructure or constituents of different word lists of dictionaries with poly-alphabetical macrostructures with vertical or horizontal parallel alphabetical access structures, cf. Wiegand (1989: 402) and Wiegand and Gouws (2013: 88). In the remainder of this section the focus will primarily be on phased-in inner texts in single macrostructures but reference will briefly be made to their occurrence in dictionaries with poly-alphabetical macrostructures with vertical parallel alphabetical access structures.

5.5.2 Phased-in inner texts in the primary macrostructure

In an expanded word list different types of phased-in inner texts can be included to split the article stretches.

5.5.2.1 Data boxes phased out of the article

In paragraph 5.4.2.3 it was mentioned that the layout of a dictionary page could influence the positioning of text boxes presented as article windows. In a comparable way the structure and layout of a dictionary article and the physical size of a specific item could lead to such an item not being included as micro-structural constituent but rather in an article-external data box. This is where a phased-in inner text is the result of an item phased out of an article and phased into the article stretch as a data box.

Due to the position of an article in a column and on a page and due to their size pictorial illustrations do not always fit into the boundaries of an article as search area. The application of a well-defined data distribution structure may then lead to a situation where such a pictorial illustration is phased out of the article and presented within a data box included as phased-in inner text.

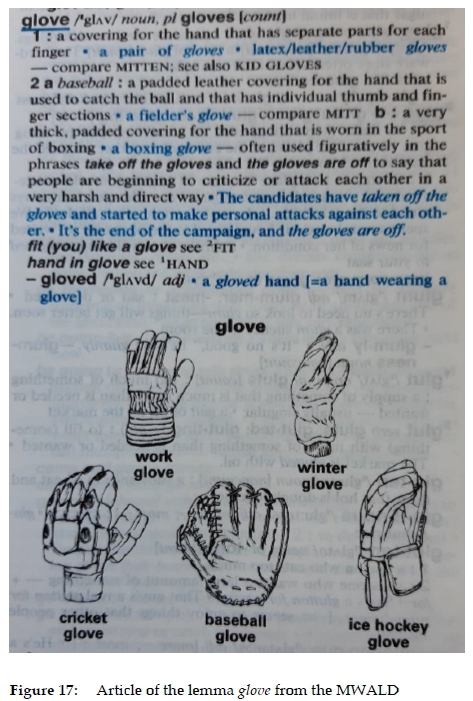

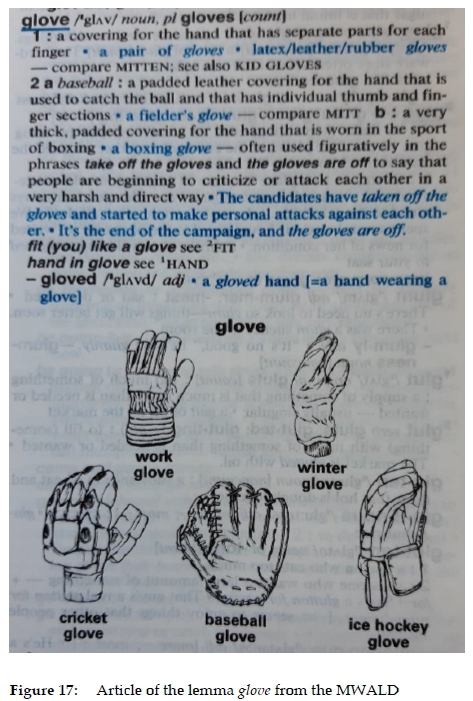

The MWALD often contains pictorial illustrations as items in its articles, as can be seen in figure 17, the article of the lemma glove:

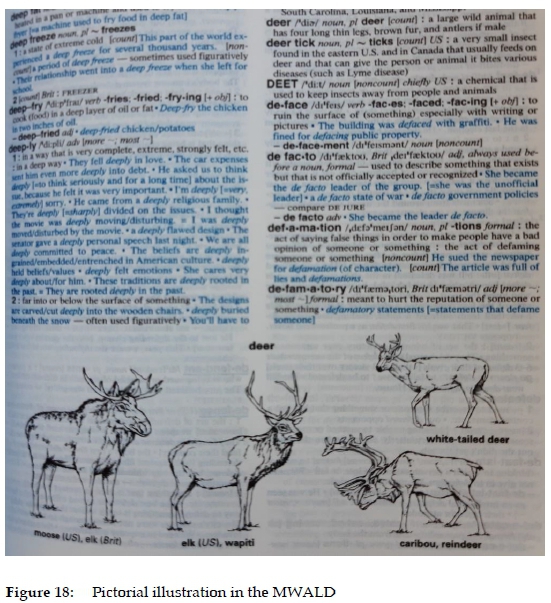

No pictorial illustration is presented within the borders of the article of the lemma sign deer in the MWALD. However, an illustration does occur on the same page, in an article-external position, as can be seen in figure 18 where the illustration is entered across two columns and splits the partial article stretch between the articles of the lemmas defamatory and defame:

It could have been problematic for the lexicographers to fit this illustration into the article of the lemma deer. Consequently it has been phased out of the article and positioned as a phased-in inner text in the article stretch, where its title has the same form as the article of the lemma deer. Because the pictorial illustration is in close proximity of the article of the lemma deer, this article has no reference to the pictorial illustration.1

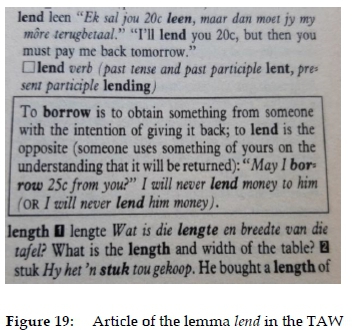

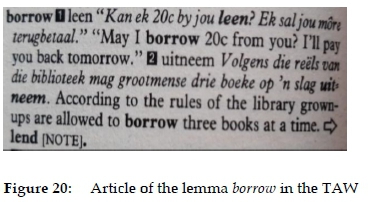

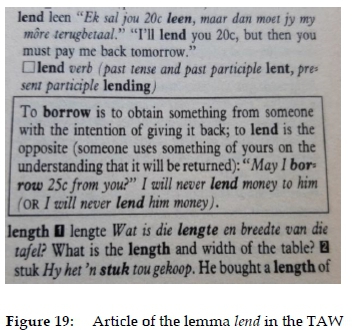

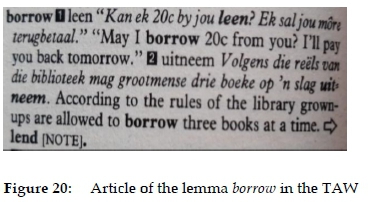

In dictionaries a distinction can be made between single and synopsis articles, cf. Bergenholtz, Tarp and Wiegand (1999: 1780). The treatment in a single article is directed only at the lemma of that article, whereas the treatment in a synopsis article also contains data relevant for the treatment of the lemmata of other articles. Data boxes also have a single or a synopsis character. This applies to article-internal as well as article-external data boxes. Figure 19, the article for the lemma lend in the Tweetalige aanleerderswoordeboek/Bilingual Learner's Dictionary (Du Plessis 1993), (henceforth abbreviated as TAW), has an article-internal data box presented as postcomment. The contents of this data box apply to the lemma lend but it is also remotely addressed at the lemma borrow. Figure 20 shows the article of the lemma borrow with an item giving a cross-reference to lend.

The data box in the article of the lemma lend is a synopsis data box. In a similar way the data box titled deer is a synopsis data box. The pictures are also relevant for the treatment of lemmata like moose, elk and caribou. Consequently the articles of these lemmata have an item giving a cross-reference "see picture at DEER".

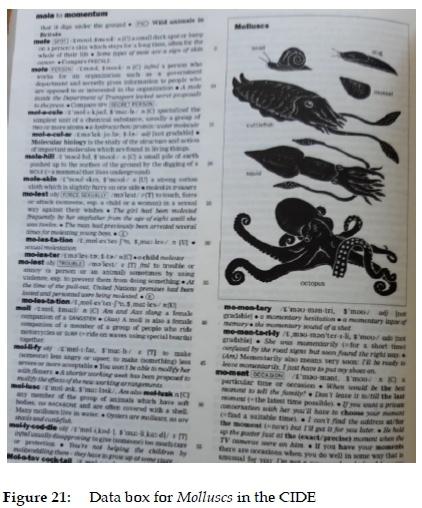

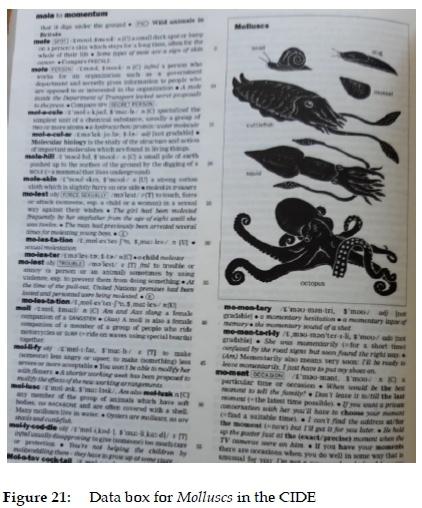

Positioning the contents of the data box deer not within the article but as an article-external phased-in inner text, can probably best be motivated on article and page layout grounds. A similar use of data boxes where the data have been phased out of an article and into a data box functioning as phased-in inner text, is found in the Cambridge International Dictionary of English (Procter 1995), (henceforth abbreviated as CIDE). Figure 21 shows the framed data box Molluscs presented as a phased-in inner text. The contents of this box could have been included in the nearby article of the lemma mollusc. The layout of the column might have been disturbed by this illustration and consequently it was phased-out into a data box in the partial article stretch but still in close vicinity of the lemma sign. This is also a synopsis data box that functions as the cross-reference address for cross-reference items in the articles of lemmata like cuttle fish, octopus and snail:

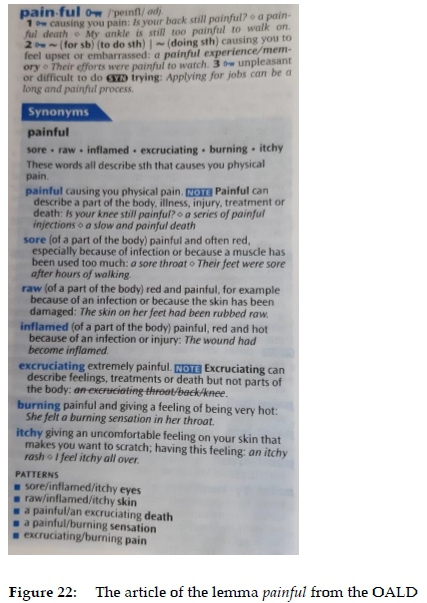

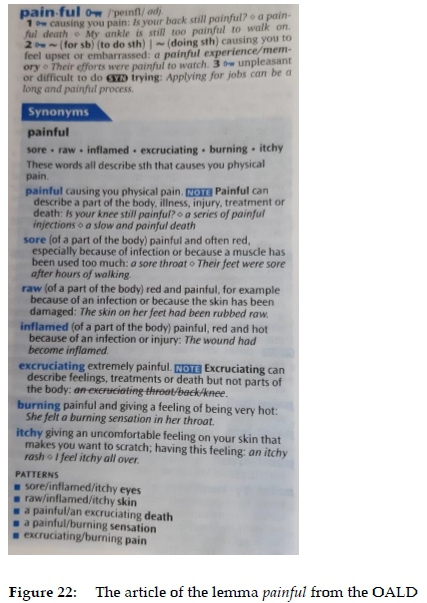

Phasing-out procedures do not only target non-boxed data that could have been included in a search zone of an article and allocate them to an article-external data box. These procedures can also target data boxes that could have had an article-internal position and phase them out to function as article-external data boxes and phased-in inner texts. The OALD frequently includes a text box containing synonyms in a postcomment position of an article, as can be seen in figure 22, the article of the lemma painful:

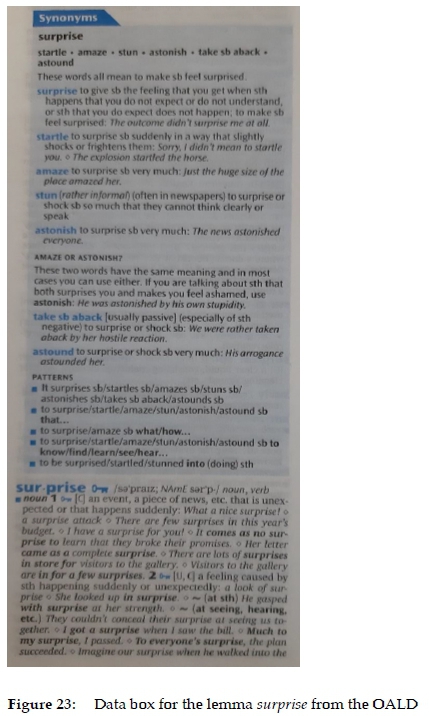

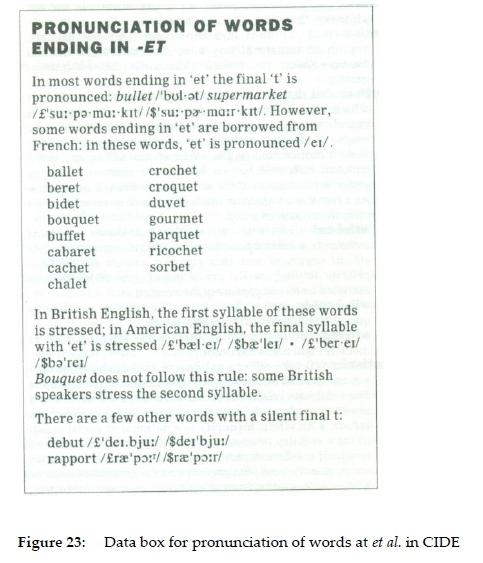

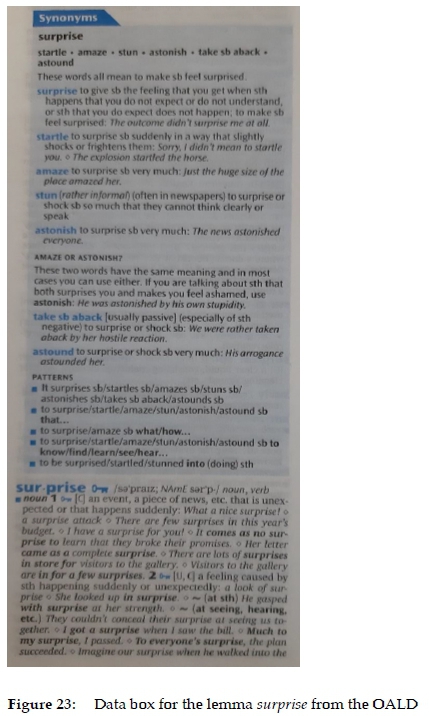

This can be regarded as the default positioning of a data box that contains synonyms. The data box for synonyms is often phased out of the article and positioned as a data box and phased-in inner text in the textual position immediately preceding the article. This is probably due to article and page layout considerations, a column break and the approach not to allow column or page breaks to divide a data box into two sections but always to present such a data box as an uninterrupted text block. This can be seen in figure 23, the article of the lemma surprise:

The biggest section of the article of the lemma surprise appears in the left column with a brief section of this article continuing in the right column. Had this section also been included in the left column there would probably not have been room for an uninterrupted data box as postcomment in that column. Consequently the data box was phased out to an article-external position, preceding the article. This data box is not positioned as precomment because it lies outside the article borders.

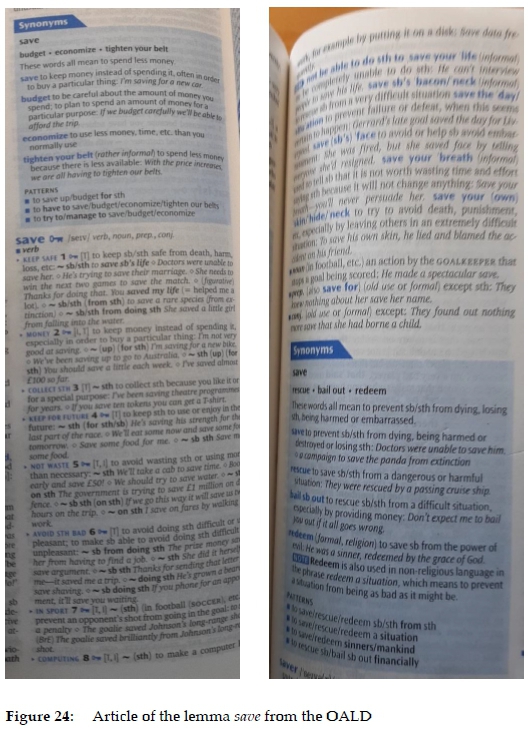

Because the planned data distribution structure of a dictionary needs to be executed in a meticulous and consistent way, it is not plausible to deviate from such a structure for column or page break or article or page layout reasons. Such a deviation impedes the access of users to the required data. The structural inconsistency resulting from the phasing out of items to article-external data boxes can be seen in the treatment of the lemma save in the OALD. In the OALD synonyms are frequently provided in data boxes, as seen in the treatment of painful. Irrespective of the degree of complexity of an article (whether it is a single or an n-fold complex article) or the number of senses treated in one or more subcomments on semantics, article-internal data boxes containing synonyms are presented as postcomments. Although such a positioning of the data box may cause addressing uncertainty in complex articles or articles with polysemous lexical items as lemmata, knowledgeable users will become familiar with this positioning of data boxes if this execution of the data distribution structure is done in a consistent way.

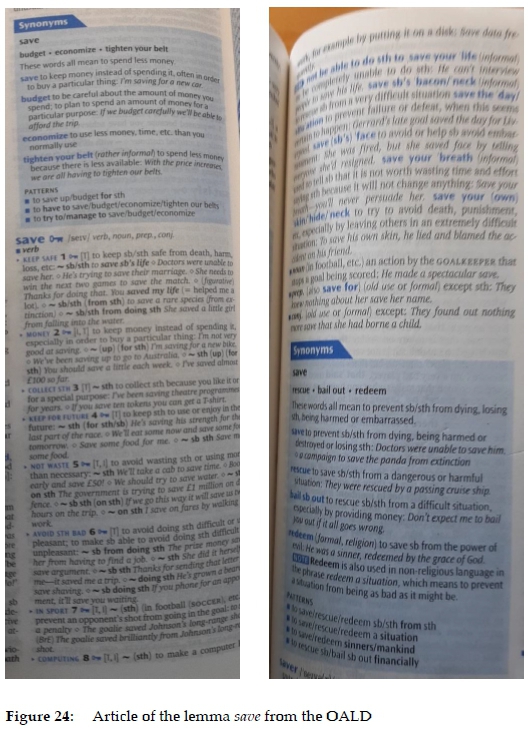

Column and page breaks result in deviations of this execution of the default data distribution structure. The treatment of the lemma save is presented in a threefold complex article with partial articles for the use of the word save as different parts of speech, namely as verb, noun, preposition and conjunction. The partial article treating the occurrence of save as a verb accounts for eight polysemous senses of this word, presented in different subcomments on semantics. The treatment is interrupted by a column and page break within the eighth subcomment on semantics. For the senses presented in the first two subcomments on semantics synonyms are provided in data boxes. The data box containing the synonyms for the first sense is included article-internally, according to the default data distribution of this type of text constituent, as a postcomment. However, the data box containing synonyms for the second sense has been phased out to a position immediately preceding the article of the lemma save as an article external phased-in inner text. This can be seen in figure 24 that shows the article as it is spread over the right column of the first and the left column of the second page:

Successfully accessing this data will be challenging for even a knowledgeable user of this dictionary. This is a typical situation where procedures in the lexicographic practice, i.e. allowing column and page breaks to impede the execution of the default data distribution structure, has resulted in theory-determined dictionary structure problems. A more user-friendly way of dealing with these two data boxes would have been to either add them both as postcomments (reflecting the order of the senses at which they are addressed) or, even better, include each data box in a slot in the relevant subcomment on semantics. This would have enabled procedures of immediate addressing that would have assisted users in a quicker and better retrieval of information.

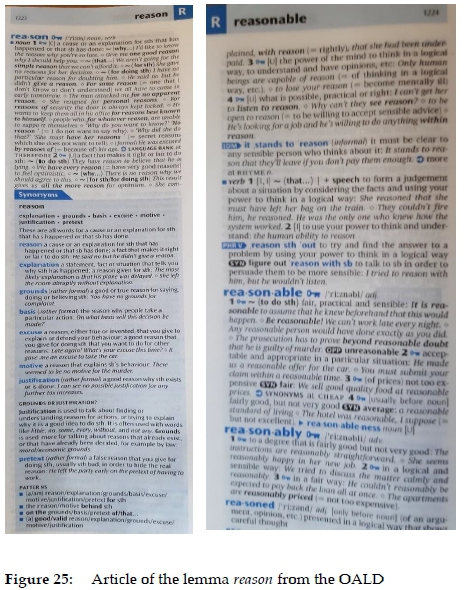

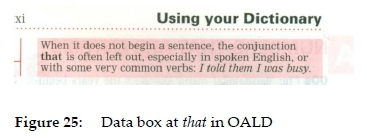

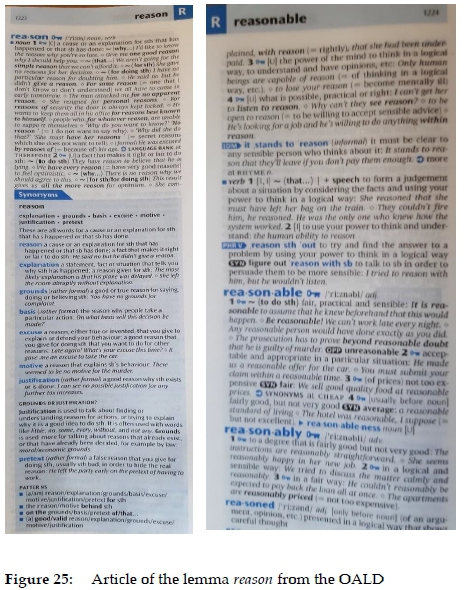

In some articles the inconsistency in the positioning of synonym data boxes in the OALD on column and page break grounds, results in such an article-internal data box not being included as the default postcomment but rather within the comment on semantics. The lemma reason has a single complex article with partial articles for its occurrence as noun and as verb. The article is interrupted by a column and page break, as seen in figure 25:

The comment on semantics of the partial article in which the occurrence as noun is treated, makes provision for four polysemous senses of this word. A data box is provided that contains synonyms for the first sense of this word. In order to present an uninterrupted text block the data box containing synonyms is positioned within the comment on semantics of the partial article in which the occurrence of reason as a noun is treated. It is positioned at the end of the first column on the first page on which the article is given. The data box occurs within the subcomment on semantics in which the second sense is treated, even though the synonyms are addressed at the first sense of the word. This positioning defies logical and consistent addressing relations.

5.5.2.2 Article-external data boxes resembling articles or article-internal items

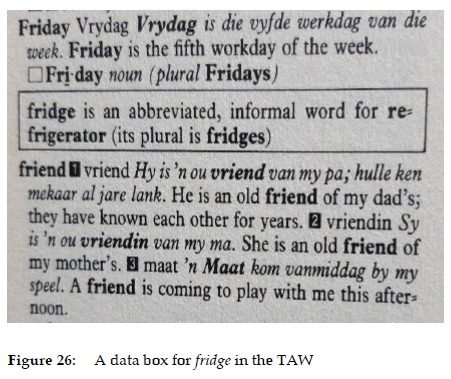

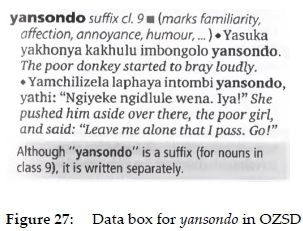

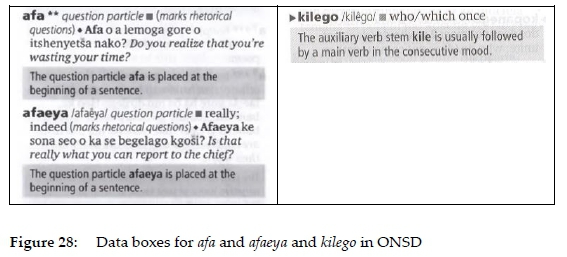

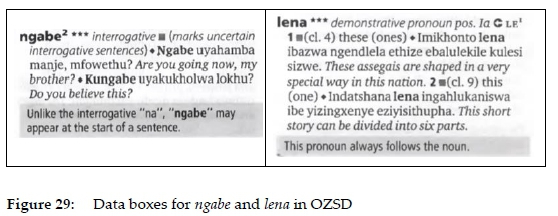

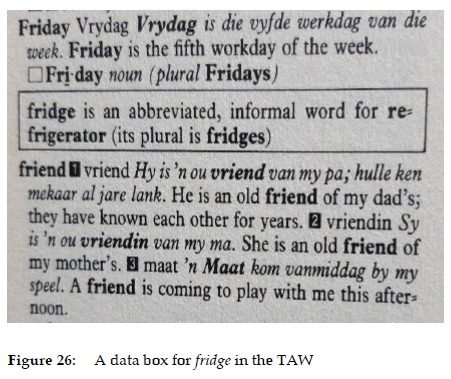

Data boxes included in the word list as phased-in inner texts are often inserted between two other articles in a partial article stretch where it adheres to the alphabetical ordering. These data boxes typically have a guiding element that looks like a lemma and the box contains a rudimentary treatment of that word. In the TAW the word fridge had not been selected as a lemma candidate. However, the lexicographer must have felt the need to make the users of this learner's dictionary aware of that informal English word. Consequently, a data box was included as a phased-in inner text and inserted in its alphabetical position in the article stretch between the articles of the lemmata Friday and friend, as seen in figure 26, with the frame clearly identifying it as a data box and not a default article:

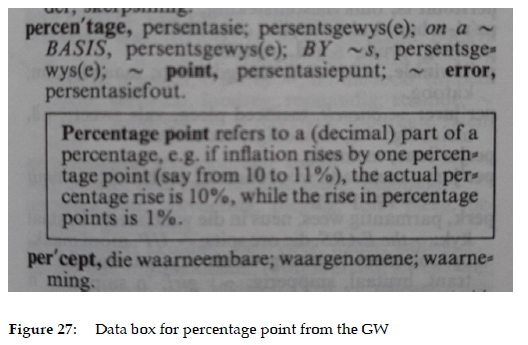

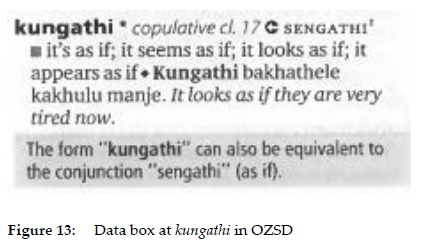

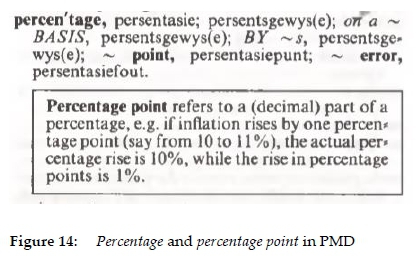

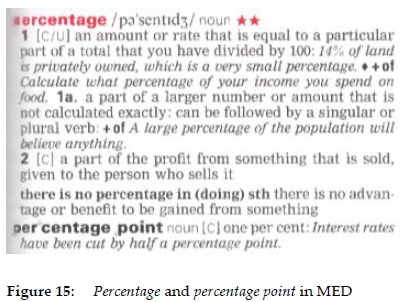

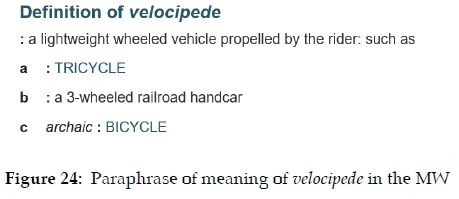

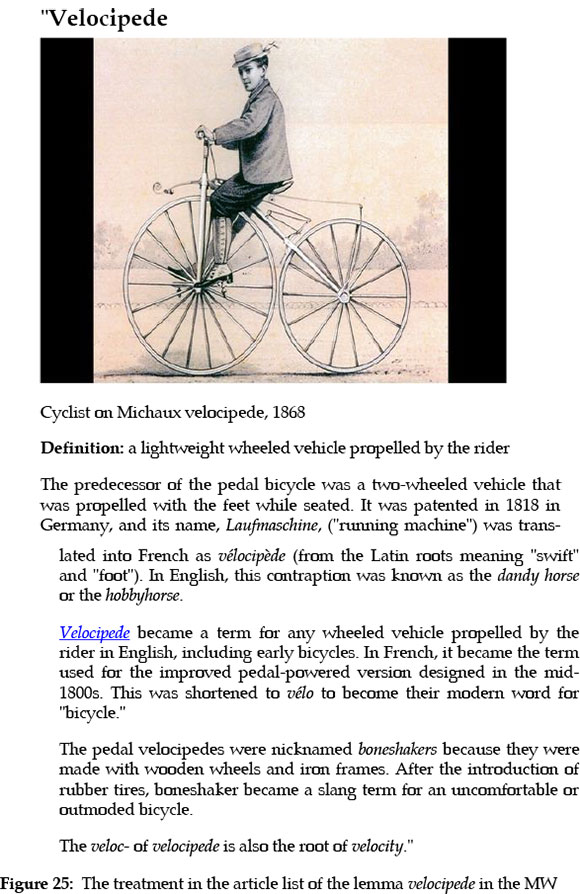

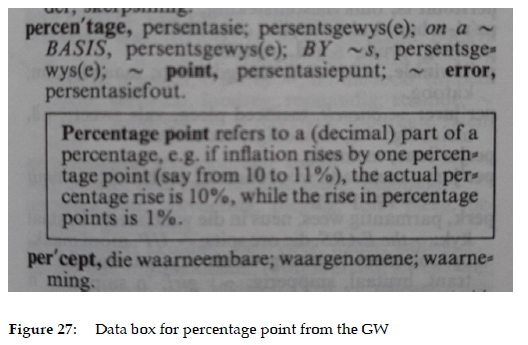

Figure 27, a partial article stretch from Groot Woordeboek/Major Dictionary (Eksteen et al. 1997); (henceforth abbreviated as GW), contains the data box with percentage point as its guiding element. This box follows the article niche attached to the article of the lemma percentage. This niche also contains the sublemma percentage point in a condensed format. In the niche the treatment of the lemma is restricted to an item giving a translation equivalent. The lexicographer wants to increase the assistance to users regarding this lemma and consequently employs the phased-in data box to supply the expression percentage point with a paraphrase of meaning.

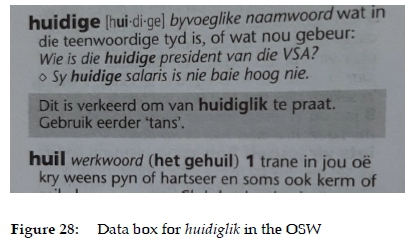

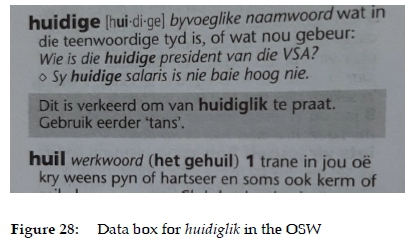

Data boxes do not always look like articles but can occur in the alphabetical position of a word that has not been included as lemma, in order to make the user aware of some relevant feature of that word. In Afrikaans the word huidiglik (=presently) is often used. However, from a linguistic perspective the use of this word is not approved. The word does not qualify for inclusion as a lemma, but the lexicographers of the monolingual Afrikaans school dictionary the Oxford Afrikaanse Skoolwoordeboek (Louw 2012), (henceforth abbreviated as OSW) would like to make their users aware of the fact that the word should not be used. The word tans should rather be used. In the alphabetical slot where huidiglik would have been entered had it been a lemma in this dictionary, the lexicographers include an article-external data box, cf. figure 28, to sensitise users that they should not use the word huidiglik.

The data box in figure 28 is not a postcomment in the article of the lemma huidige but rather a phased-in inner text.

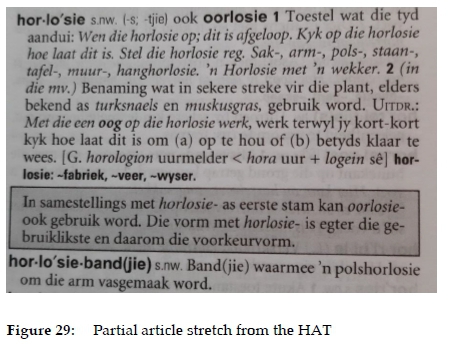

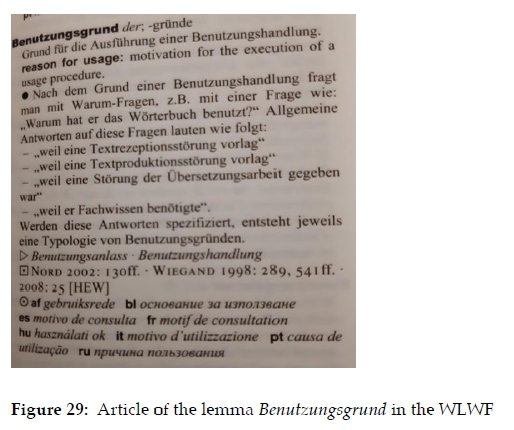

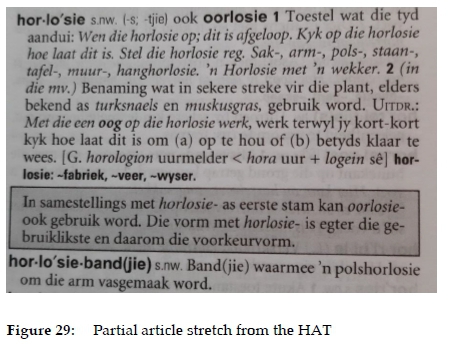

Article-external data boxes often include data that do not represent a data type that belongs to the default microstructural items but it does add to the treatment of a given lemma or lemma cluster. Figure 29 presents a partial article stretch from HAT:

In the comment on form of the article of the lemma horlosie (watch) it is indicated that oorlosie is a variant form of horlosie. Attached to the article of this lemma is a lemma cluster, presented as a first level nest that includes a condensed presentation of compounds with horlosie- as first stem. Between this nest and the following main lemma a data box has been inserted with guidance regarding the formation of compounds with horlosie- as first stem. Although this data is relevant to the main lemma horlosie- and to the sublemmata presented in the nest, the data box is positioned outside the article of the main lemma as well as the nest of sublemmata and therefore it is a phased-in inner text.

5.5.2.3 Other article boxes included as phased-in inner texts

A variety of other types of data boxes also function as phased-in inner texts in dictionaries. A typical feature of many of these data boxes is their synopsis character whilst the data presentation in others complements and expands the default data coverage of a specific lemma. These data boxes convey data regarded by the lexicographer as important enough to include them in salient search venues like data boxes. The added value of these data boxes is unfortunately too often impeded by insufficient access guidance.

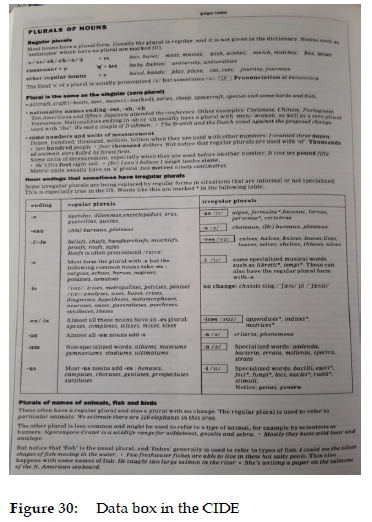

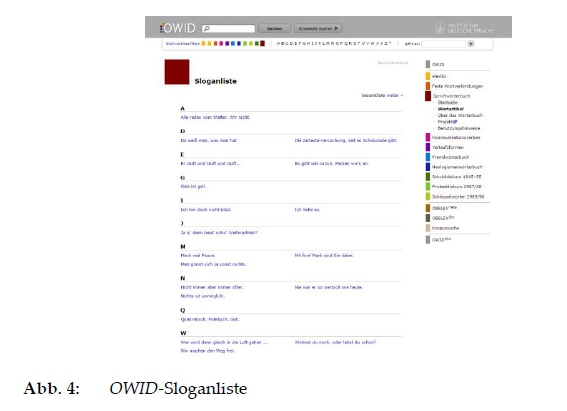

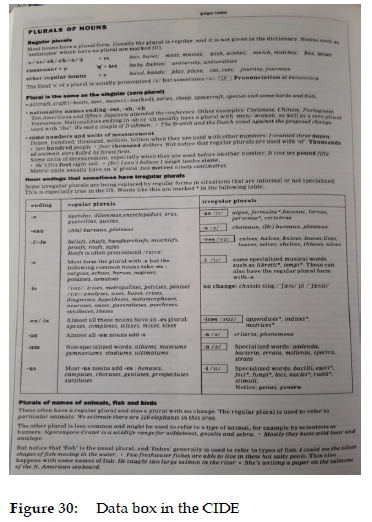

In close proximity of the article of the lemma plural in CIDE one finds the data box titled "Plural of nouns", presented in figure 30:

The treatment in this data box is not addressed at any single lemma but it adds value to the treatment of all nouns that take plural. The problem is that it is very difficult for users in need of this guidance to know where to find the help. CIDE has a back matter text that provides an alphabetical index with relevant page numbers of all pictures, language portraits and lists of false friends included in the word list. The list includes an entry "Plurals" but no entry "Plural of nouns", the title of the data box in figure 30. It will remain a challenge for the target users of this dictionary to optimally benefit from this data box. They will probably only have access to this data box if they accidentally consult that page, seeing that the lemma plural is on the previous page and its article has no cross-reference to the data box.

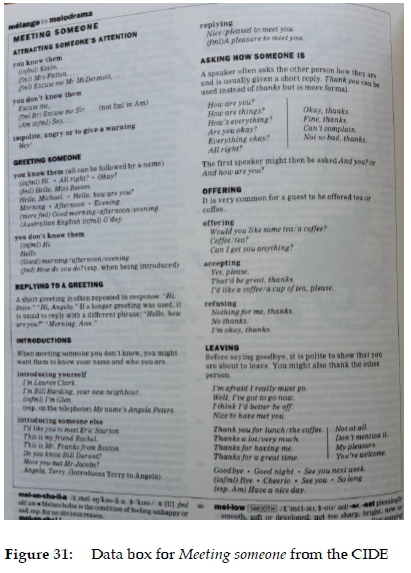

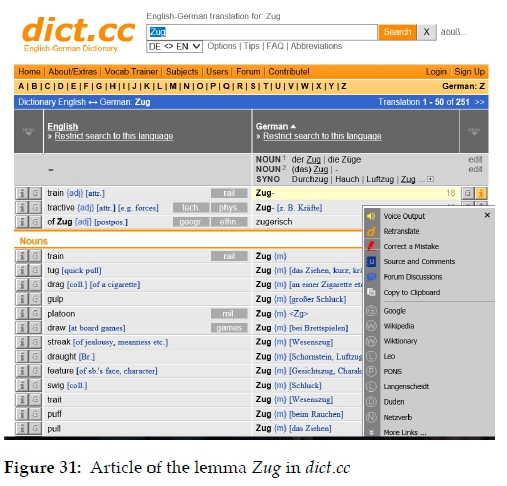

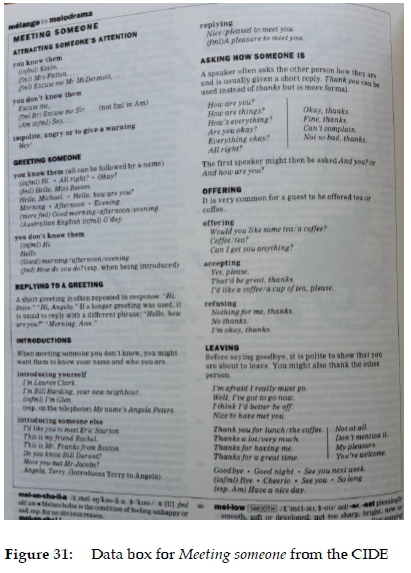

Having consulted the lemmata meet and meeting in the CIDE a user has to turn the page to find the data box "Meeting someone", given in figure 31:

This data box contains pragmatic and cultural guidance that could assist the envisaged target users of this dictionary in their daily communication. Skilled users will be able to access this data box via the back matter list. However, for the user not aware of that list it would have been better if this data box could have been positioned on the same page where the lemmata meet and meeting appear.

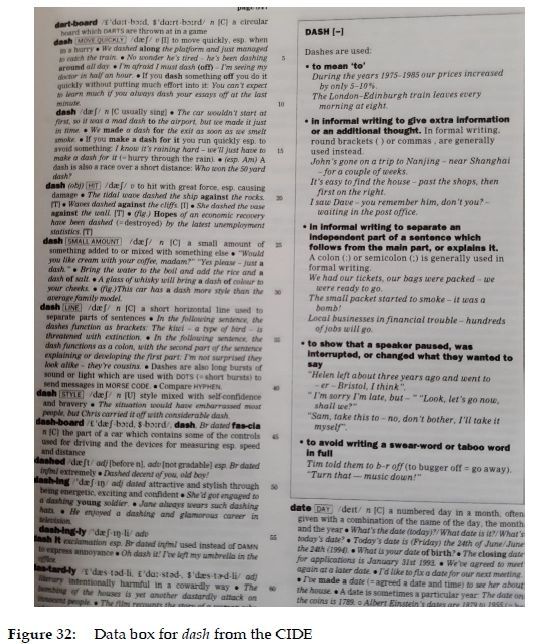

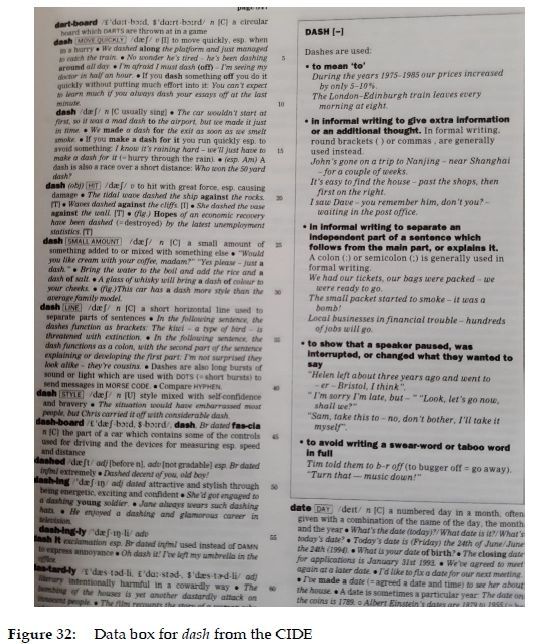

On the same page in CIDE where the lemma dash is treated a data box has been presented that offers valuable complementary assistance regarding the use of a dash, cf. figure 32:

The contents of a data box like this one can hardly be included in the article of the corresponding lemma. Data boxes like these elevate the quality of the lexicographic treatment.

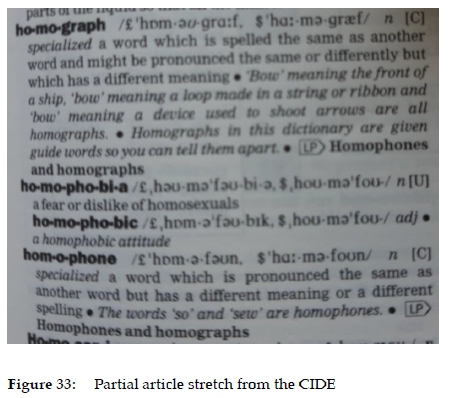

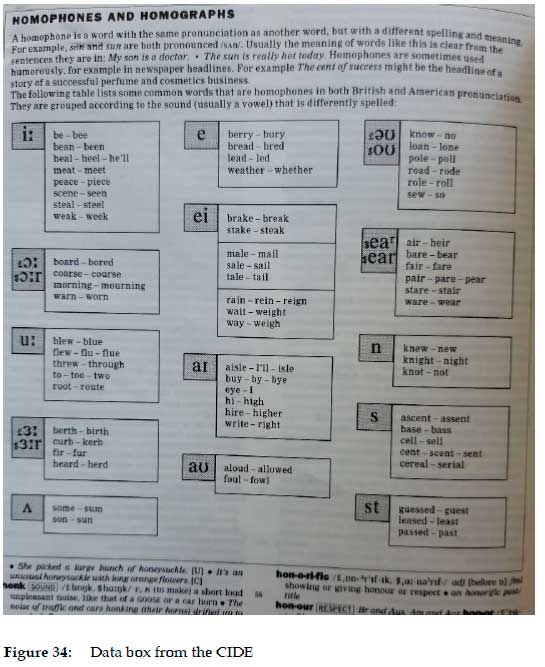

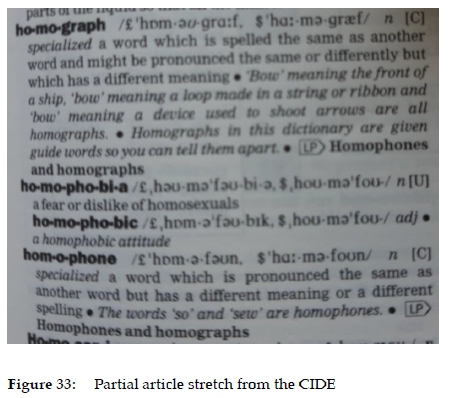

Even if an article in a learner's dictionary displays an extended obligatory microstructure lexicographers have to restrict the extent of the data presented in the different search zones and should refrain from procedures of data overload. If lexicographers want to respond to the needs of the users of a learner's dictionary, like CIDE, for some linguistic guidance typically contained in text books, they can use data boxes included as phased-in inner texts to convey this kind of data. Figure 33, a partial article stretch from CIDE, contains articles of the lemmata homograph and homophone. In each one of these articles there is an item giving a cross-reference to the language portrait (LP) Homophones and homographs.

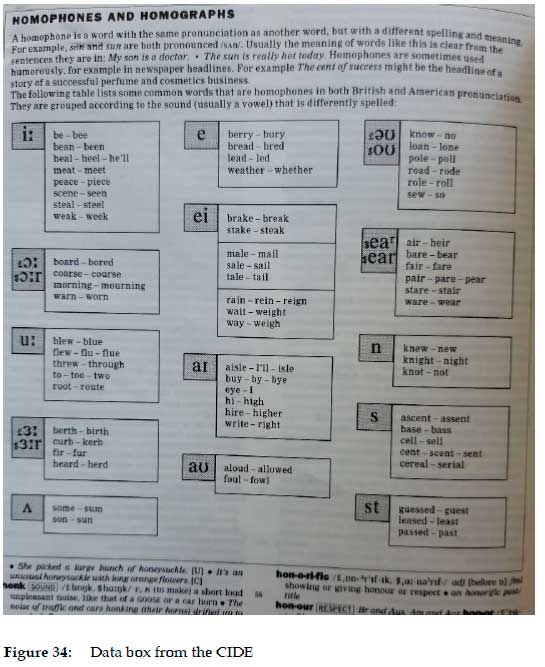

This language portrait is presented as the data box seen in figure 34. This data box can also be accessed via the index in the back matter text. It has a synopsis character that could assist users in clearly distinguishing between homophones and homographs.

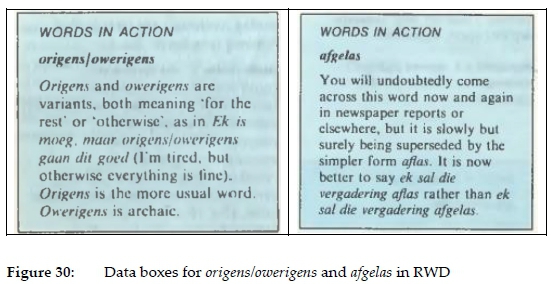

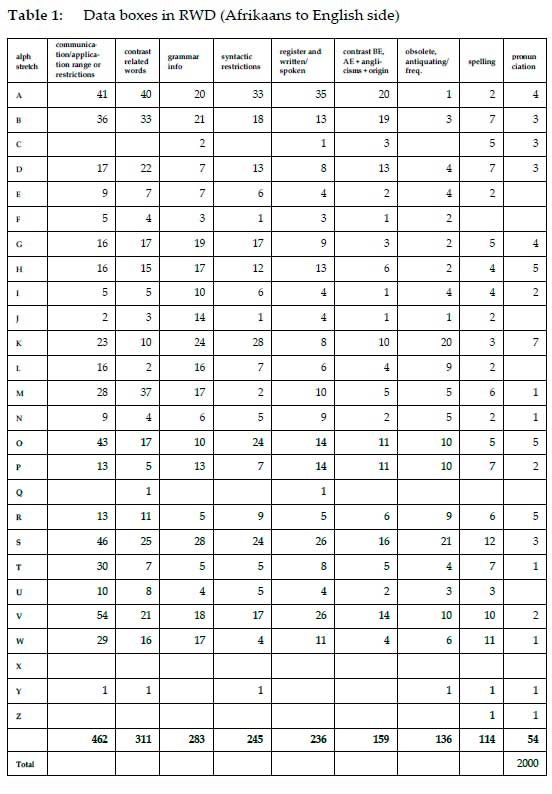

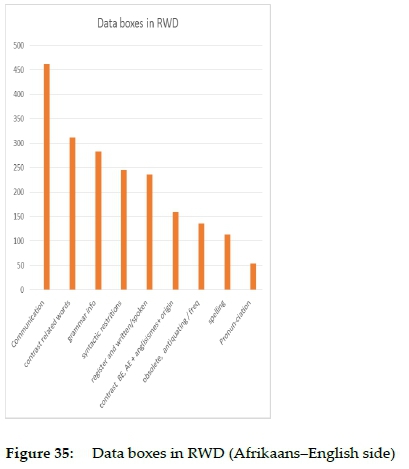

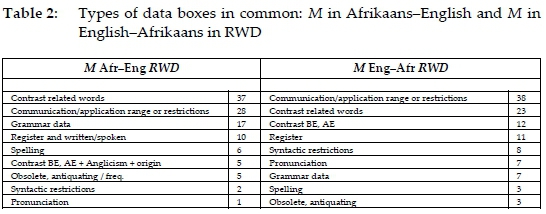

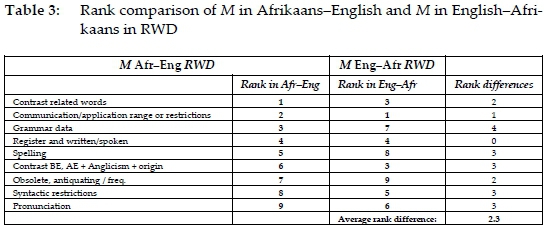

5.5.3 Phased-in inner texts in the secondary constituent of a parallel macro-structure

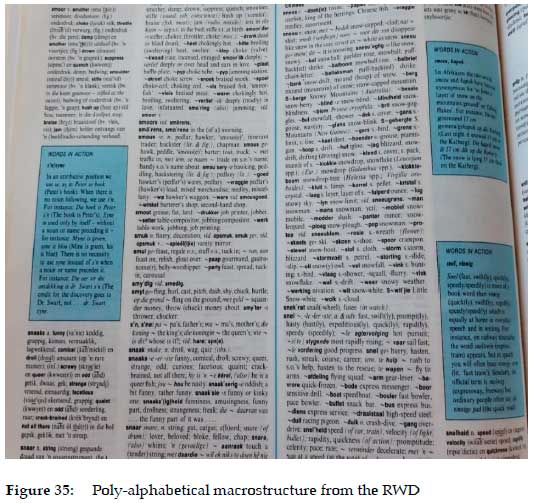

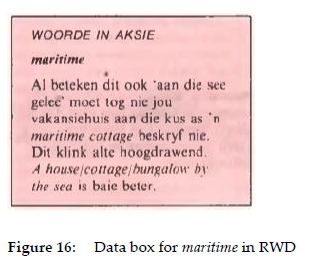

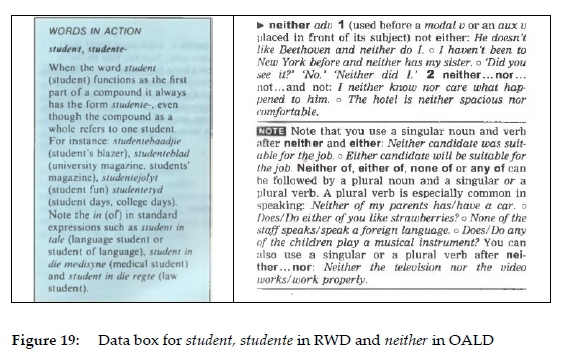

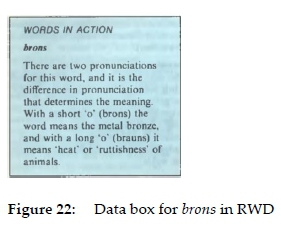

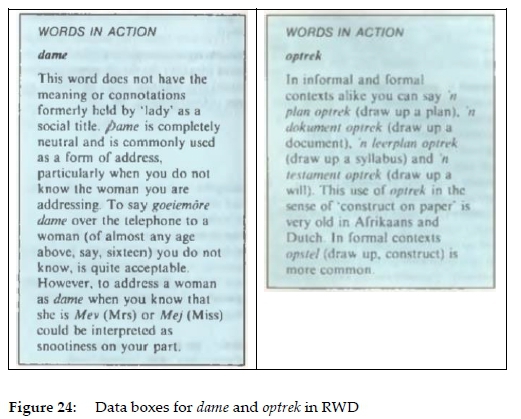

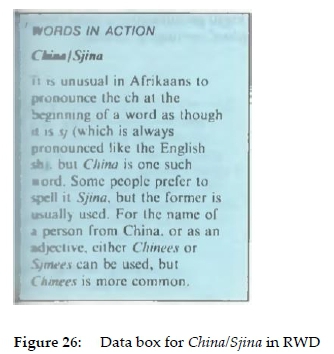

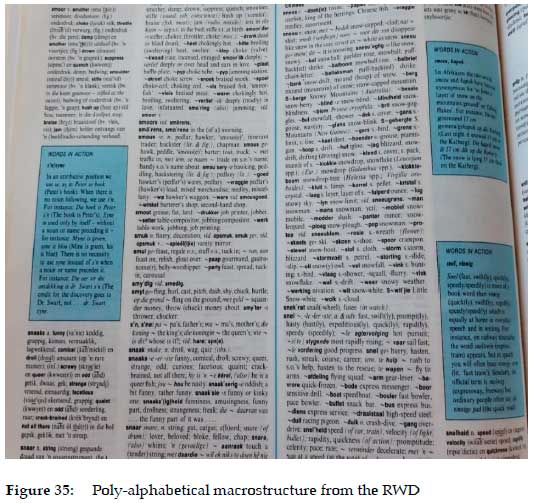

Dictionaries can have more than one word list and therefore more than one macro-structure. More than one macrostructure could prevail within the same alphabetical constituent of a dictionary. One such type identified by Wiegand (1989: 402) and Wiegand and Gouws (2013: 88) is the poly-alphabetical macrostructures with vertical parallel alphabetical access structures. The Reader's Digest AfrikaansEngelse Woordeboek/English-Afrikaans Dictionary (Grobbelaar 1987), (henceforth abbreviated as RWD), displays these macrostructures. The primary macrostructure of this dictionary is presented in two central columns on each page. An additional column on the left and an additional column on the right of the two central columns constitute a secondary macrostructure. The partial article stretch of the secondary macrostructure on each page falls within the alphabetical domain of the partial article stretch of the primary macrostructure on the same page. The RWD is an expanded version of a previously published bilingual dictionary. The primary macrostructure is an unchanged version of that of the previous dictionary. The secondary macrostructure is constituted by new text constituents. In the secondary word list there are articles that have a selection of lemmata from the primary macrostructure as guiding elements. A different and innovative treatment (not to be discussed here) has been executed in these articles. The secondary macrostructure displays an expanded word list with partial article stretches split by phased-in inner texts, as seen in figure 35:

The text boxes presented as phased-in inner texts are titled Words in action. They are addressed at some of the source and target language items in the articles of the primary macrostructure and they contain different types of data, e.g. pragmatic, usage, linguistic and lexical guidance.

The data boxes help to introduce new comments to enhance the quality of the original dictionary.

Conclusion

Data boxes occur frequently and in diverse ways in dictionaries. This is especially the case in printed dictionaries, although some electronic dictionaries, especially those that are based on printed dictionaries, also employ this type of lexicographic entry. Although various aspects of the use of data boxes have been discussed in metalexicographic literature, much still needs to be done in this regard. This paper focused on what data boxes are, identified them as a type of lexicographic entry and indicated where they are positioned in dictionaries and that they should be used in such a way that they add value to dictionaries. This can serve as an aid for future lexicographers who wish to employ data boxes in their dictionaries.

Endnote

1 The value of a picture presenting different types of deer (but not all types) is not discussed here. The decision to give a pictorial illustration rests with the lexicographer. Therefore it cannot be expected that a specific word will be illustrated or illustrated in the same way in all dictionaries. For example, the online version of the MED does not contain such an illustration.

Acknowledgement

This work is based on the research supported in part by the National Research Foundation of South Africa (Grant specific unique reference numbers (UID) 85434 and (UID) 8576). The Grantholders acknowledge that opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in any publication generated by the NRF supported research are that of the authors, and that the NRF accepts no liability whatsoever in this regard.

References

Dictionaries

BW = Gouws, R., I. Feinauer and F. Ponelis. 1994. Basiswoordeboek van Afrikaans. Pretoria: J.L. van Schaik.

CIDE = Procter, P. (Ed.). 1995. Cambridge International Dictionary of English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

GW = Eksteen, L.C. et al. (Eds.). 199714. Groot Woordeboek/Major Dictionary. Cape Town: Pharos.

HAT = Odendal, F.F. and R.H. Gouws. 20055. Verklarende Handwoordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal. Cape Town: Pearson Education South Africa.

JBS = Stoman, A. et al. (Eds.). 2018. Junior Tweetalige Skoolwoordeboek/Junior Bilingual School Dictionary. Cape Town: Pharos.

LED = Summers, D. (Ed.). 2006. Longman Exams Dictionary. Harlow: Pearson Education.

LSASD = Bullon, S. et al. (Eds.). 2007. Longman South African School Dictionary. Harlow: Pearson Education.

MED = Rundell, M. (Ed.). 20072. Macmillan English Dictionary for Advanced Learners. Oxford: Macmillan.

MPVP = Rundell, M. (Ed.). 2005. Macmillan Phrasal Verbs Plus. Oxford: Macmillan Education. MWALD = Perrault, S.J. (Ed.). 2008. Merriam-Webster's Advanced Learner's English Dictionary. Springfield, Massachusetts: Merriam-Webster.

OALD = Turnbull, J. (Ed.). 20108. Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary of Current English. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

OSD = Pheiffer, F. et al. (Eds.). 2007. Oxford Afrikaans-Engels/English-Afrikaans Skoolwoordeboek/School Dictionary. Cape Town: Oxford University Press Southern Africa.

OSW = Louw, P. (Senior Editor). 2012. Oxford Afrikaanse Skoolwoordeboek. Cape Town: Oxford University Press Southern Africa.

RWD = Grobbelaar, P. 1987. Reader's Digest Afrikaans-Engelse Woordeboek/English-Afrikaans Dictionary. Cape Town. The Reader's Digest Association, South Africa (Pty) Ltd.

TAW = Du Plessis, M. 1993. Tweetalige aanleerderswoordeboek/Bilingual Learner's Dictionary. Cape Town: Tafelberg.

WLWF = Wiegand, H.E., M. Beißwenger, R.H. Gouws, M. Kammerer, A. Storrer and W. Wolski (Eds.). 2017. Wörterbuch zur Lexikographie und Wörterbuchforschung/Dictionary of Lexicography and Dictionary Research. Vol. 2. Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter.

Other references

Bergenholtz, H., S. Tarp and H.E. Wiegand. 1999. Datendistributionsstrukturen, Makro- und Mikrostrukturen in neueren Fachwörterbüchern. Hoffmann, L. et al. (Eds.). 1999. Fachsprachen. Ein internationales Handbuch zur Fachsprachenforschung und Terminologiewissenschaft/ Languages for Special Purposes. An International Handbook of Special-Language and Terminology Research, Bd./Vol. 2: 1762-1832. Berlin: De Gruyter. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. 2014. Expanding the Notion of Addressing Relations. Lexicography: Journal of ASIALEX 1(2): 159-184. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. 2018. Expanding the Data Distribution Structure. Lexicographica 34: 225-237. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. and D.J. Prinsloo. 2005. Principles and Practice of South African Lexicography. Stellenbosch: SUN PReSS, AFRICAN SUN MeDIA. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. and D.J. Prinsloo. 2010. Thinking out of the Box - Perspectives on the Use of Lexicographic Text Boxes. Dykstra, A. and T. Schoonheim (Eds.). 2010. Proceedings of the XIV Euralex International Congress, Leeuwarden, 6-10 July 2010: 501-511. Leeuwarden: Fryske Akademy. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. and S. Tarp. 2017. Information Overload and Data Overload in Lexicography. International Journal of Lexicography 30(4): 389-415. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. et al. (Eds.). 2013. Dictionaries. An International Encyclopedia of Lexicography. Supplementary Volume: Recent Developments with Focus on Electronic and Computational Lexicography. Berlin/New York: De Gruyter. [ Links ]

Hausmann, F.J. and H.E. Wiegand. 1989. Component Parts and Structures of Monolingual Dictionaries: A Survey. Hausmann, F.J. et al. 1989-1991: 328-360.

Hausmann, F.J. et al. (Eds.). 1989-1991. Worterbücher. Dictionaries. Dictionnaires. An International Encyclopedia of Lexicography. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Louw, P.A. and R.H. Gouws. 1996. Lemmatiese en nielemmatiese adressering in Afrikaanse verta-lende woordeboeke. Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Taalkunde 14(3): 92-100. [ Links ]

Taljard, E., D.J. Prinsloo and R.H. Gouws. 2014. Text Boxes as Lexicographic Device in LSP Dictionaries. Abel, A., C. Vettori and N. Ralli (Eds.). 2014. Proceedings of the 16th EURALEX International Congress: The User in Focus, Bolzano/Bozen, Italy, 15-19 July 2014: 697-705. Bolzano/ Bozen: EURAC. [ Links ]

Tarp, S. 2004. Basic Problems of Learner's Lexicography. Lexikos 14: 222-252. [ Links ]

Wiegand, H.E. 1989. Aspekte der Makrostruktur im allgemeinen einsprachigen Wörterbuch: alphabetische Anordnungsformen und ihre Probleme. Hausmann, F.J. et al. 1989-1991: 371-409.

Wiegand, H.E. 1996. Das Konzept der semiintegrierten Mikrostrukturen. Ein Beitrag zur Theorie zweisprachiger Printwörterbücher. Wiegand, H.E. (Ed.). 1996. Wörterbücher in der Diskussion II: 1-82. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer. [ Links ]

Wiegand, H.E. 2006. Adressierung in Printwörterbüchern. Präzisierungen und weiterführende Überlegungen. Lexicographica 22: 187-261. [ Links ]

Wiegand, H.E. 2011. Adressierung in der ein- und zweisprachigen Lexikographie. Eine zusammenfassende Darstellung. Kürschner, W. and M. Ringmacher (Eds.). 2011. Aus Ost und West: 109-234. Frankfurt: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Wiegand, H.E., S. Beer and R.H. Gouws. 2013. Textual Structures in Printed Dictionaries. An Overview. Gouws, R.H. et al. (Eds.). 2013: 31-73.

Wiegand, H.E. and R.H. Gouws. 2011. Theoriebedingte Wörterbuchformprobleme und wörter-buchformbedingte Benutzerprobleme I: Ein Beitrag zur Wörterbuchkritik und zur Erweiterung der Theorie der Wörterbuchform. Lexikos 21: 232-297. [ Links ]

Wiegand, H.E. and R.H. Gouws. 2013. Addressing and Addressing Structures in Printed Dictionaries. Gouws, R.H. et al. (Eds.). 2013: 273-314.

Wiegand, H.E and M. Smit. 2013. Microstructures in Printed Dictionaries. Gouws, R.H. et al. (Eds.). 2013: 149-214.

* This is the first in a series of three articles dealing with various aspects of lexicographic data boxes.

^rND^sBergenholtz^nH.^rND^nS.^sTarp^rND^nH.E.^sWiegand^rND^sGouws^nR.H.^rND^sGouws^nR.H.^rND^sGouws^nR.H.^rND^nD.J.^sPrinsloo^rND^sGouws^nR.H.^rND^nS.^sTarp^rND^sLouw^nP.A.^rND^nR.H.^sGouws^rND^sTaljard^nE.^rND^nD.J.^sPrinsloo^rND^nR.H.^sGouws^rND^sTarp^nS.^rND^sWiegand^nH.E.^rND^sWiegand^nH.E.^rND^sWiegand^nH.E.^rND^sWiegand^nH.E.^rND^nR.H.^sGouws^rND^1A01^nXiqin^sLiu^rND^1A02^nJing^sLyu^rND^1A03^nDongping^sZheng^rND^1A01^nXiqin^sLiu^rND^1A02^nJing^sLyu^rND^1A03^nDongping^sZheng^rND^1A01^nXiqin^sLiu^rND^1A02^nJing^sLyu^rND^1A03^nDongping^sZhengARTICLES

For a Better Dictionary: Revisiting Ecolexicography as a New Paradigm

Vir 'n verbeterde woordeboek: 'n Herbesoek aan die ekoleksikografie as nuwe paradigma

Xiqin LiuI; Jing LyuII; Dongping ZhengIII

ISchool of Foreign Languages / Research Center for Indian Ocean Island Countries, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China (flxqliu@scut.edu.cn)

IISchool of Foreign Languages, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou, China (Corresponding Author, jinglyu@qq.com)

IIIDepartment of Second Language Studies, University of Hawai'i at Mãnoa, Honolulu, USA (zhengd@hawaii.edu)

ABSTRACT

Driven by practical conundrums that users often face in maximizing (e-)dictionaries as a companion resource, this article revisits and redefines ecolexicography as a new paradigm that situates compilers and users in a relational dynamic. Drawing insights from ecolinguistics and cognitive studies, it appeals for rethinking the compiler-user relationship and placing dictionaries in a distributed cognitive system. A multidimensional framework of ecolexicography is proposed, consisting of a micro-level and a macro-level. To the micro-level, both symbolic and cognitive dimensions are added: (1) the dictionary can be symbolically viewed as a semantic and semiotic ecology; (2) dialogicality should be highlighted as an essential aspect of e-dictionary compilation/ design, and distributed cognition can be emancipatory for rethinking dictionary use. The macro-level concerns the obligations of lexicographers as committed to three interrelated ecologies or ecosystems: language, socio-culture and nature. Transdisciplinary in nature, ecolexicography involves a holistic, systematic and integrative methodology to nourish lexicographical practice and research. Corpus-based Frame Analysis is introduced to identify ecologically destructive frames and ideologies so that the dictionary discourse could be reframed. The study upgrades our understanding of the ontological, epistemological and methodological aspects related to ecolexicography, serving as a call for philosophical reflections on metalexicography. It is also expected to create an opportunity for lexicographers to examine problems with (e-)dictionaries in a new light and dialogue about how to find solutions.

Keywords: e-dictionary, learner's dictionary, semantic ecology, semiotic ECOLOGY, ECOLINGUISTICS, ECOLEXICOGRAPHY, DIALOGICALITY, DISTRIBUTED COGNITION, SOCIO-CULTURE, CORPUS-BASED FRAME ANALYSIS, METALEXICOGRAPHY

OPSOMMING

Voortgedryf deur praktiese probleme wat gebruikers dikwels ervaar in die maksimalisering van (e-)woordeboeke as 'n handboekhulpbron, word 'n herbesoek aan die ekoleksikografie gebring en word dit geherdefinieer as nuwe paradigma wat samestellers en gebruikers in 'n relasionele dinamika posisioneer. Uit insigte wat verkry is uit die ekolinguistiek en kognitiewe studies word daar gevra om 'n herbesinning van die samesteller-gebruikers-verhou-ding en om woordeboeke in 'n verspreide kognitiewe stelsel te beskou. 'n Multidimensionele raam-werk van die ekoleksikografie, wat bestaan uit 'n mikro- en makrovlak, word voorgestel. Tot die mikrovlak word beide simboliese en kognitiewe dimensies gevoeg: (1) die woordeboek kan simbolies beskou word as semantiese en semiotiese ekologie; (2) diskoers moet beklemtoon word as 'n essensiële aspek van die samestelling/ontwerp van die e-woordeboek, en verspreide kognisie kan bevrydend wees vir die herbeskouing van woordeboekgebruik. Die makrovlak is gemoeid met die verpligting van leksikograwe wat verbind is tot drie ekologieë of ekostelsels wat onderling aan mekaar verbonde is: die taal, sosiokultuur en natuur. Die ekoleksikografie, transdissiplinêr van aard, behels 'n holistiese, sistematiese en integrerende metodologie om die leksikografiese praktyk en navorsing te voed. Korpusgebaseerde Raamanalise word gebruik om ekologies destruktiewe raamwerke en ideologieë te identifiseer sodat woordeboekdiskoers geherdefinieer kan word. Hier-die studie verbeter ons begrip van die ontologiese, epistemologiese en metodologiese aspekte wat verband hou met die ekoleksikografie, en ontlok filosofiese denke rakende die metaleksikografie. Daar word ook verwag dat dit 'n geleentheid vir leksikograwe sal bied om probleme rakende (e-)woordeboeke in 'n nuwe lig te ondersoek en vir gesprekvoering oor hoe om oplossings vir hier-die probleme te vind.

Sleutelwoorde: e-woordeboek, aanleerderswoordeboek, semantiese ekoLOGIE, SEMIOTIESE EKOLOGIE, EKOLINGUISTIEK, EKOLEKSIKOGRAFIE, DISKOERS, VERSPREIDE KOGNISIE, SOSIOKULTUUR, KORPUSGEBASEERDE RAAMANALISE, METALEKSIKOGRAFIE

1. Introduction

Ecology refers to (the scientific study of) the relation of plants and living creatures to each other and to their surroundings. How organisms interact with one another and with their environment has become "a central question governing the survival and sustainability of human societies, cultures and languages" (Cronin 2017). Ecolinguistics (or ecological linguistics) investigates language in an ecological context. It explores the role of language in the human society and the ecosystem, and shows how linguistics can be used to address key ecological issues. This new branch of linguistics represents a turning point in language studies. Revolutionary in nature, it catalyzes the growth of many interdisciplinary fields of research. It distinguishes two positions for the ecological study of languages: one concerned with the relations between languages, and languages with the environment; the other investigating the interrelationships existing in a language (Albuquerque 2018). This distinction was first elaborated by Makkai (1993), who put forward the term "exoecological linguistics" for the former, and "endoecological linguistics" for the latter. They could be understood as the macro-level and the micro-level in the framework of ecolinguistics.

Originating from lexicography and ecolinguistics, ecolexicography was first proposed by Sarmento (2000) as a part of applied linguistics, with a focus on addressing the effects and results that each lexeme brings to dictionary users. Sarmento (2005) argues that the main issue of ecolexicography is what the role of words is in our world and how a word can create, maintain or destroy a world. Many scholars (e.g. Hoey 2001; Tsunoda 2005) resonate with this viewpoint, stressing the importance of dictionaries as a tool of promoting linguistic diversity, socio-cultural harmony, and environmental sustainability. However, Sarmento (2000, 2002, 2005) holds that ecolexicography does not deal with the elaboration of ecology dictionaries or ecological terms. This perspective may be too limited as ecolexicography unavoidably faces the treatment of ecological vocabulary.

Albuquerque (2018) describes ecolexicography as a new discipline in lexicography and explores what it could contribute to pedagogical lexicography, especially in the analysis of dictionaries and the microstructure, and in producing teachers with a different worldview and in environmental education for students. He argues that eco-lexicography as a science should assist lexicographers to: develop a new way of looking at the world (the ecological vision of the world) and the words; realize the power of the words of a language for its speakers and for the world; offer ways to identify the ecological factors in language; and propose a new structure of article and definition (ibid.). He also points out that research on ecolexicography regarding these aspects is only at an embryonic stage, and it is necessary to lay a foundation for the ecolexicography approach that needs more researchers, research and projects. There is actually significant potential for (re)discovering important inroads or beneficial outcomes.

To breathe new life into this field, we have to re-examine the lexicographical products seriously, and rethink the cognitive and socio-cultural processes of dictionary compilation and use from a novel perspective. This article is expected to create an opportunity for lexicographers to dialogue about the problems they encounter with (e-)dictionaries and communicate how our ecolexicography proposal can shed light on the solutions it can provide.

2. Rationale for revisiting ecolexicography

2.1 Practical problems: the necessity

Abundant literature (e.g. Hoey 2001; Tsunoda 2005) reveals that there are at least two kinds of problems with current dictionaries: anti-ecological language and destructive ideologies, and problematic (e-)dictionary design and use.

2.1.1 Anti-ecological language and destructive ideologies

Many dictionaries, including pedagogical dictionaries, are not ecologically oriented and do not pay enough attention to users' awareness of the importance of environmental protection and sustainable development of human society or cultures (Wang 2003).

Tian et al. (2016) find that some examples in The New Age English-Chinese Dictionary (NAECD) fail to adopt a positive attitude toward ecology. Four tendencies of lexicographers dealing with biological and ecological lexemes were identified by Trampe (2001): (1) reification, i.e. treatment of certain living beings as things (goods of production or consumption), e.g. "cow" is a commodity; (2) use of euphemism (and other language mechanisms) to hide certain facts that may be regarded as violent for the consumer or general public, e.g. "pesticide" is replaced by "plant protection tool"; (3) defamation of traditional/ subsistence agriculture, which are generally labeled as being "unproductive", "expensive", etc.; (4) use of slogans and phraseological elements to convince the population that the destruction of the ecosystem is something natural/inevitable or even to disguise such destruction, affirming it as something good, e.g. "to create more wealth for all". These four tendencies alert lexicographers to the anti-ecological language of the world economic vision that is fragmented, increasingly alienating the human being from other species and nature (Albuquerque 2018).

Furthermore, anti-sociocultural ideologies are found in dictionaries. Tenorio (2000) claims that some definitions in The Collins COBUILD English Language Dictionary (CCELD) are inaccurate and biased in gender representation, and ignore changes in society. Hu et al. (2019) assert that The Contemporary Chinese Dictionary (CCD) portrays men as valuable social members while overlooking the value of women.

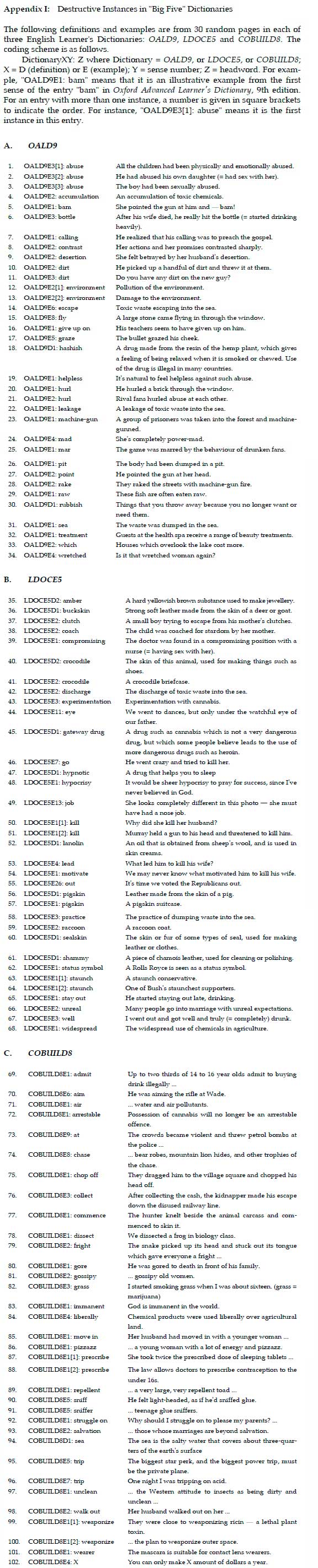

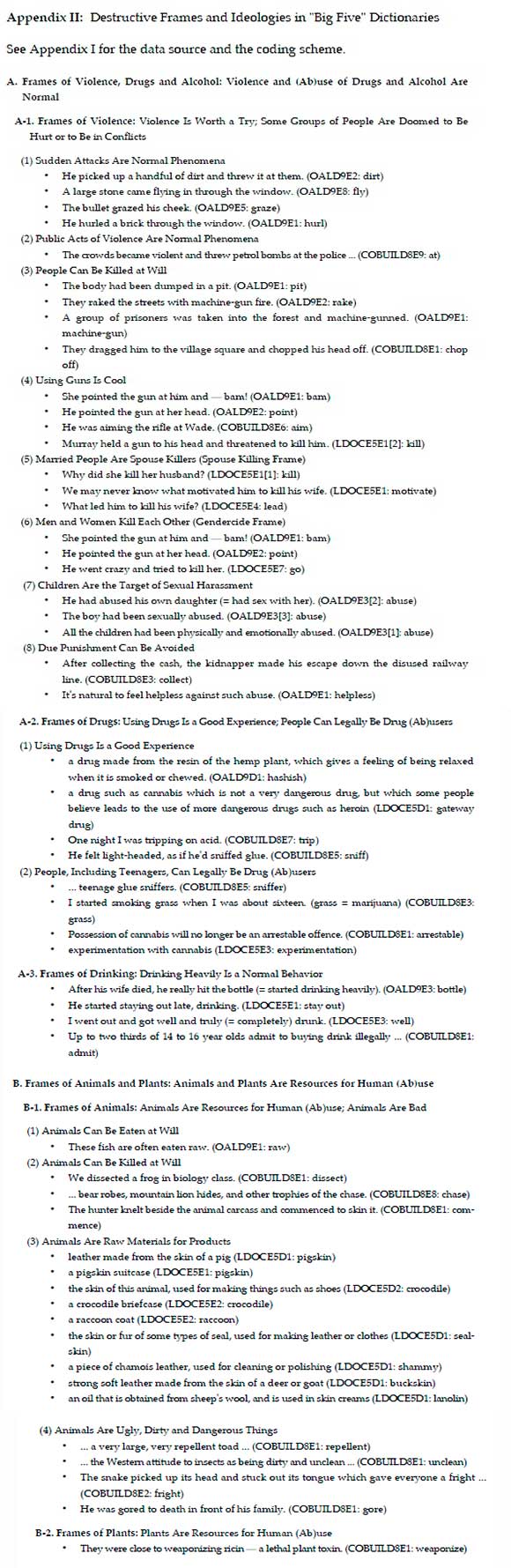

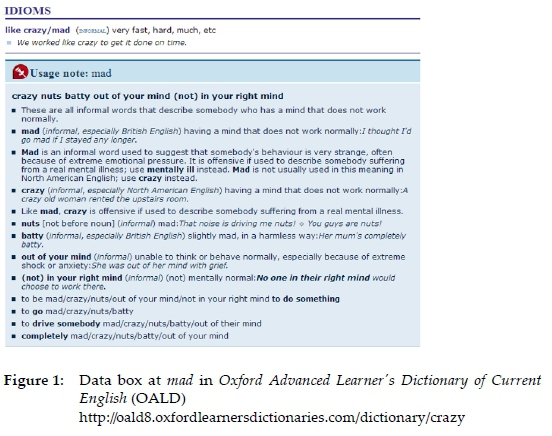

We found similar results (see Appendices I and II) after examining three of the "Big Five" dictionaries1: Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary (OALD9), Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English (LDOCE5) and Collins COBUILD Advanced Learner's Dictionary (COBUILD8). To achieve representativeness and generalizability of our data and the outcomes, we retrieved 30 random pages from each dictionary and all the linguistic data in those pages were collected to create a corpus. Each text was annotated and analyzed to disclose the ecologically (non)destructive frames in dictionaries. Frames (also called schemas) are schematizations of our experience and knowledge of the world (Fillmore 1985), and description of word meanings must be associated with cognitive frames in the reader's mind2. In our survey, we adapted and integrated corpus-based discourse analysis (Baker 2006) into frame analysis (Fillmore and Baker 2009; Lakoff 2014). The procedure of frame analysis (Blackmore and Holmes 2013) is to ask the following questions for a particular frame: What values does the frame embody? Is a response necessary? Can the frame be challenged? If so, how? Can (and should) a new frame be created?

We compared the frames represented by the headwords in the dictionaries and those represented by the same words in Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA). In the end, we identified over 30 potentially destructive instances (definitions and examples) from more than 30 entries of each of the three dictionaries. For instance, "He had abused his own daughter" and "The boy had been sexually abused" are used as illustrative examples in the entry of "abuse" in OALD9 (see Part A in Appendix I). In total, we found that 23 themes were disharmoniously framed, and many of them were beyond the traditional lexicographic attention because it seems that the top seven themes we have identified (violence, animal, drug, possession, pollution, sea and alcohol) have not been fully discussed in lexicography (Lyu and Liu, in preparation). Destructive frames and ideologies (e.g. "Children are the target of sexual harassment", see Part A in Appendix II) seem to be prevalent, largely due to lexicographers' choice in this challenging age of the Anthropocene (ibid.).

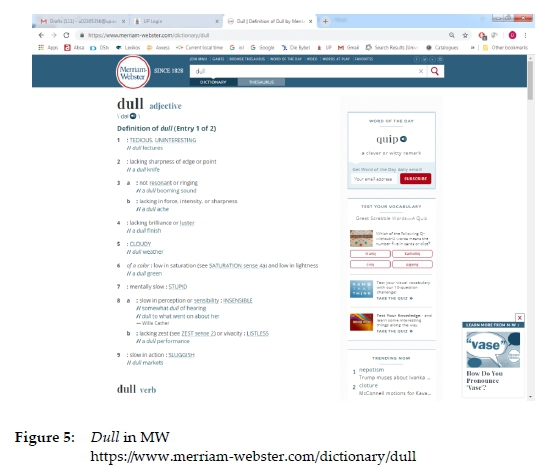

2.1.2 Problematic (e-)dictionary design and use

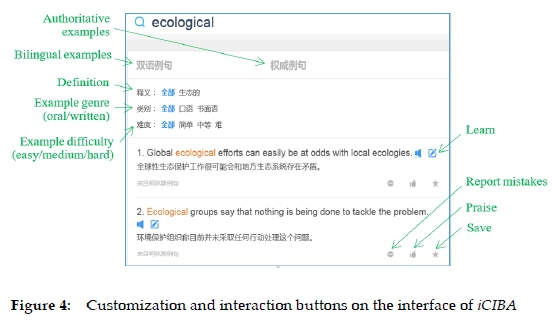

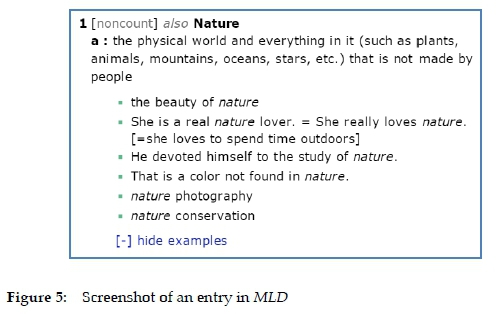

Researchers find that many lexicographic e-products were developed with little influence from innovative theoretical suggestions and, as a result, current e-dictionaries often do not live up to the expectations of users and are misused by their users (cf. Gouws 2014). Many of them have problems including definition insufficiency and inaccuracy (Zhang 2015: 79-82), lack of customization (Liu, Zheng and Chen 2019), information overload (Gouws and Tarp 2017; Huang and Tarp 2021) and lack of education in dictionary use (e.g. Winestock and Jeong 2014). For instance, dictionaries integrated into English learning applications produced in China were found to suffer from deficiencies such as "inconsistent treatment of words and senses, data overload, difficult access, and inconvenient location of the pop-up window that displays the lexicographical items", which may "impact negatively on the learners' motivation and the learning process in general" (Huang and Tarp 2021). In the digital revolution, the way of displaying data in e-dictionaries must be redefined (Gouws 2014), and semiotic resources (e.g. color, typography, and navigation devices) should be properly employed according to the context (Liu 2015, 2017; Farina et al. 2019).

Underlying reasons for the above problems are complex, and some may be ontological and epistemological. At the fundamental level, many lexicographers, perhaps indulged in Western analytical thinking, still hold a fragmented view, rather than a systematic view of the components in a dictionary and its microstructure. There lacks an awareness that a dictionary, comparable to ecology, is characterized by complexity, holism, diversity and dynamicity. For example, the lack of e-dictionary customization and individualization is against the principle of ecological diversity and dynamicity. The technical transition from paper-based to electronic layout demands different cognitive attention and visual engagement. Users' individual and collective needs should be considered by designers. From an ecological perspective of language learning, even if a universal dictionary could be made, the users would tailor its use (especially those with a high degree of literacy and computer skills). So, dictionary design should try to allow users to adapt the product to their needs, goals and values, to some extent (see Liu, Zheng and Chen 2019 for an example of varying types of motivation for smartphone dictionary use in China).

To make things even worse, the practice that one definition/example fits all, or lack of adaptability, may aggravate the problem of data overload. For instance, the word "pig" is defined as "An omnivorous domesticated hoofed mammal with sparse bristly hair and a flat snout for rooting in the soil, kept for its meat" in the Lexico.com (called Oxford Dictionaries English before 2019, https://www.lexico.com/definition/pig). This is a general dictionary (rather than a specialized one) and the definition is offered to users in general, but this is a very difficult technical definition. It is very likely that many users do not understand the difficult terminologies in the complicated explanation. Perhaps such information/data overload (Gouws and Tarp 2017), traceable to inconsideration of dictionary types and users, is against the principle of "ecological harmony" (cf. Zhou 2017). The idea that online dictionaries have unlimited space has furthered the often uncritical inclusion of too much data (Gouws and Tarp 2017).

In brief, the status quo highlights the importance of proper ontological and epistemological orientations for lexicography. With an ecological view, ecolexicography has the potential to offer a fresh set of theoretical-methodological contributions in dictionary research and compilation, especially in the proposal of a differentiated microstructure (Albuquerque 2018). Nevertheless, for systematic strategies to remedy the above problems, ecolexicography needs to be redefined as a new paradigm by drawing theoretical and methodological insights from related fields.

2.2 Theoretical underpinnings: the feasibility

2.2.1 Lexicographical theories

Three theories may shed new light on ecolexicography, the Communicative Theory of Lexicography (Yong and Peng 2007), the Function Theory of Lexicography (Bergenholtz and Nielsen 2006; Tarp 2007), and the Discourse Approach to Critical Lexicography (Chen 2019).

The first two theories are user-oriented and focus on the interactivity feature of dictionary compilation and use. The Communicative Theory of Lexicography views the dictionary as communication (instead of reference and text). Drawing insights from Systemic-Functional Linguistics (Halliday 1985), Yong and Peng (2007) assert that dictionary context encompasses three subcategories: field, mode and tenor. This communicative perspective inspires reconsideration of the interaction between dictionary compilers and users. According to the Function Theory of Lexicography (Bergenholtz and Nielsen 2006; Tarp 2007), dictionary functions are communication-orientated or cognition-orientated, and lexicographers must identify the relevant functions and select and present appropriate data so that the dictionary satisfies the needs of users in different situations.

Chen's (2019) Discourse Approach to Critical Lexicography, or Critical Lexicographical Discourse Studies (CLDS), offers both theoretical and methodological inspirations for ecolexicography. Responding to the call for lexicographers' social accountability, CLDS views the dictionary as discourse, and discourse is a three-tiered concept consisting of "a piece of text, an instance of discursive practice and an instance of social practice" (Fairclough 1992). To uncover the ideologies and power relations in dictionaries, CLDS analysts will first conduct an analysis of the dictionary as text, investigating, for example, the choice of vocabulary in explaining the meaning of a word, the choice of illustrative examples, and the order of senses (ibid.). Thereafter how the dictionary is produced, distributed and consumed will be examined, followed by a discussion of the social context in which the dictionary is produced and consumed (ibid.).

2.2.2 Ecolinguistic and cognitive theories

Two interrelated theoretical achievements in ecolinguistic and cognitive studies may offer nourishments for ecolexicography and help transform the discipline. The first is the "distributed language" and EDD (ecological, dialogical and distributed) theory (Van Lier 2002; Cowley 2011; Linell 2009, 2013; Zheng 2012; Steffensen 2015), and the second is Steffensen and Fill's (2014) redefinition of ecolinguistics by identifying the four ways in which the ecology of language is conceptualized.

Distributed language theory means that language is not an independent symbolic system used by individuals for communication but rather an array of behaviors that constitute human interaction. Language perception occurs in a context of activity and interactivity (Van Lier 2002). Permeating the collective, individual and affective life of living beings, language is a profoundly distributed, multi-centric activity as a part of our ecology, and it gives us an extended ecology in which our co-ordination is saturated by values and norms that are derived from our sociocultural environment (Cowley 2011). In brief, language (or language use) is ecological, dialogical (linked to others) and distributed (rather than located to any single place, such as the speaker's brain) (Zheng 2012).

In applied linguistics, Van Lier (2002) might be the first to have introduced an ecological perspective to language education. The ecological view has inspired a rethink of language and language acquisition/cognition from a socio-cultural perspective and boosted the development of such emerging theories as "the Complexity Theory" (see Larsen-Freeman 2011). Ecolinguists redefine language by dividing it into two different consensual domains: (1) first-order languaging (linguistic actions and activities in the communication); (2) second-order sociocultural inscriptions and norms (Kravchenko 2009). Following this theoretical vein, Zheng (2012) proposed her ecological view of language learning and use which highlights the dialogicality and distributed cognition of participants in communication. Distributed cognition means that cognition is spread in and reliant on different contexts. Traditional cognition is redefined as an activity "distributed" in the physical and socio-cultural environment. In cultural ecologies, resources like a dictionary can link people in practices that enable the accomplishment of tasks.

In ecological terms, agents' languaging behaviors are caused not by stimuli but the affordances, opportunities for action and coaction motivated by the ecosocial environments (Zheng et al. 2012). Language is embodied (not merely abstractly procedural), embedded (shaping and shaped by social systems in a cultural world), enacted (living in or realized in and through action), extended, situated, and multi-scalar (existing on different time-scales) (Cowley 2011; Linell 2013).

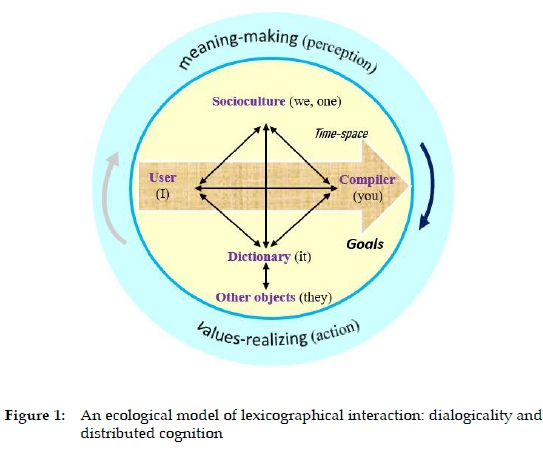

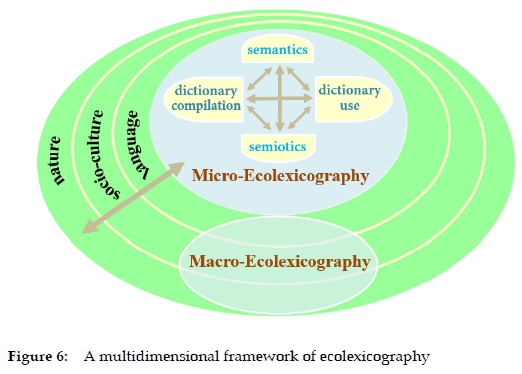

Based on the communication models of semiotic activity by Zheng (2012) and Linell (2009), we build an ecological model of lexicographical interaction (see Figure 1).

In the outer layer of the model, there are two concepts from ecological psychology, meaning-making (perception system) and values-realizing (action system). Values-realizing means that an individual agent makes "a conscious choice among multiple values at play in any given moment of action and interaction" (Zheng et al. 2012). It is values that "guide the selection and revision of goals across diverse time-space scales, under which the sociocultural norm 'we' (laws or rules of phonology, syntax, or semantics) are nested" (Zheng 2012). There are interactions among the dictionary user (I), compiler (you), sociocultural norm (we), dictionary (it) and other objects (they) in the real world or virtual space.

Based on the model (Figure 1), the relationship between the dictionary (it) and its user (I) should be rethought. The dictionary should be a friend that is always there, so faithful, helpful and thoughtful. This means that it should have such qualities as accuracy, functionality and adaptability. In addition, the interaction between the dictionary (it) and the other objects (they) in the physical environment is also meaningful. To improve its adaptability and customization, an e-dictionary is often embedded in or fused with the interfaces of learning activities like those of reading or writing software. Meaning-making and values-realizing are in the cycle of perception and action involving dictionary compilation and use.

Another illuminating insight that ecolexicography can gain from ecolinguistics contributes to an upgraded understanding of its overall framework. Steffensen and Fill (2014) point out four ways the language ecology has been conceptualized as a symbolic ecology, a cognitive ecology, a natural ecology, and a sociocultural ecology. Similarly, in terms of ecolexicography, a symbolic ecology can be understood as the semantic and semiotic ecology in a dictionary. A cognitive ecology of lexicography involves dictionary compilation/ design as dialogism and dictionary use as distributed cognition. The two constitute the microlevel of ecolexicography. At the macrolevel, ecolexicography should be committed to serving the linguistic, natural and sociocultural ecologies. The differentiation (and complementarity) between the microlevel and the macrolevel of ecolexicography mirrors the exoecological vs. endoecological division in ecolinguistics.

The endoecological position or the microlevel of ecolexicography, an obvious lacuna in literature, needs to be delineated to form a complete framework. This article aims to take a small step toward addressing the gap by revisiting ecolexicography as a new paradigm.

3. Ecolexicography at the micro-level

3.1 The semantic and semiotic ecology in a dictionary

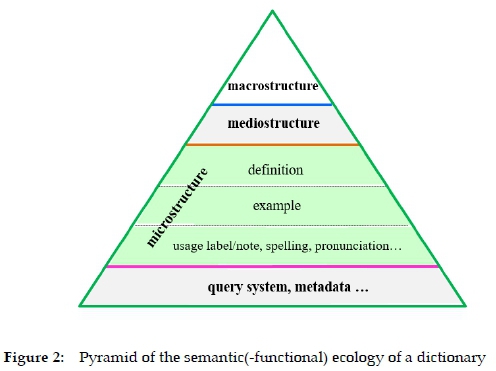

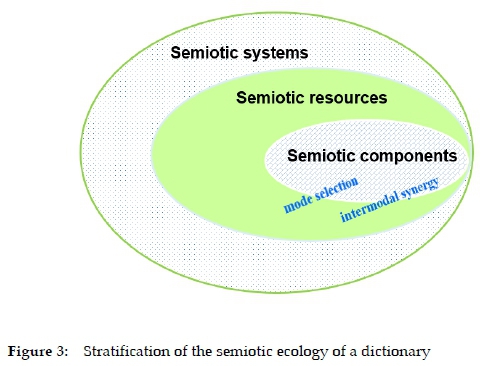

Some scholars (e.g. Liu 2015) hold that the dictionary as a complex system can be symbolically compared to an ecology in two senses, semantic and semiotic.