Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Lexikos

On-line version ISSN 2224-0039

Print version ISSN 1684-4904

Lexikos vol.31 Stellenbosch 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.5788/31-1-1630

ARTICLES

https://doi.org/10.5788/31-1-1630

Feminine Personal Nouns in the Polish Language. Derivational and Lexicographical Issues

Vroulike persoonsname in Pools. Afleidings- en leksikografiese kwessies

Agnieszka Malocha-Krupa

Institute of Polish Philology, Philological Faculty, University of Wroclaw, Poland (agnieszka.malocha-krupa@uwr.edu.pl)

ABSTRACT

The paper is dedicated to issues related to designations of women in the Polish language from the second half of the 19th century until the present time. The socio-cultural history of a group of Polish feminine personal nouns (referred to as feminitives or feminatives) which denote women's social and/or occupational status is discussed. It is argued that feminine personal nouns have been directly dependent on various ideologies: women's emancipation, socrealism and feminism. Ideologies have impacted the use of feminatives, by intensifying or limiting their use in discourse during a particular period, and the attitude of language users to ideologies has influenced the way in which feminatives are perceived. While presenting the richness of the repertoire of gender exponents in contemporary Polish, the possibility of the incorporation of feminine personal formations into dictionaries of general Polish in a scientific and objective manner is investigated. A similar idea was proposed at Wroclaw University, as a result of which a group of female lexicographers compiled Slownik nazw zenskich polszczyzny [Dictionary of Polish Female Nouns]. Some of its innovative lexicographical assumptions (description, not prescription, a discourse-centred method) are discussed in this article. The text corpus presented in the article enables the reader to trace the history of feminine personal nouns in Polish, i.e. their disappearance and re-appearance in the language.

Keywords: feminativum/feminine personal nouns, word formation, LEXICOGRAPHY, LANGUAGE CULTURE, EMANCIPATION OF WOMEN, FEMINISATION, GENDER MORPHOLOGY, GENDER AND LANGUAGE, DERIVATION, PRAGMATICS

OPSOMMING

Hierdie artikel skenk aandag aan kwessies rondom die benoeming van vroue in Pools vanaf die tweede helfte van die 19de eeu tot vandag. Die sosio-kulturele geskiedenis van 'n groep Poolse vroulike persoonsname (waarna verwys word as feminitiewe of feminatiewe) wat vroue se sosiale en/of beroepsstatus aandui, word bespreek. Daar word aangevoer dat vroulike persoonsname direk afhanklik was van verskeie ideologieé: die emansipasie van vroue, Sosialis-tiese Realisme en feminisme. Ideologieé het die gebruik van feminatiewe deur middel van die intensivering of beperking van hul gebruik in die redevoering in 'n bepaalde periode bei'nvloed, en die taalgebruikers se houding teenoor ideologieé het 'n uitwerking gehad op die manier waarop feminatiewe waargeneem word. Terwyl die rykheid van die repertoire van gendervoorbeelde in hedendaagse Pools bespreek word, word die moontlikheid van die insluiting van vroulike per-soonsnaamvorme in algemene Poolse woordeboeke op 'n wetenskaplike en objektiewe manier ondersoek. 'n Soortgelyke idee is by die Wroclaw Universiteit voorgestel waarna 'n groep vroulike leksikograwe die Stownik nazw zenskich polszczyzny [Woordeboek van Poolse vroulike naam-woorde] saamgestel het. Sommige van die innoverende leksikografiese aannames (deskriptief, nie preskriptief nie, 'n diskoersgesentreerde metode) word in hierdie artikel bespreek. Die tekskorpus wat in die artikel voorgelê word, stel die leser in staat om die geskiedenis van vroulike persoonsname in Pools, m.a.w. hul verdwying en herverskyning in die taal, na te spoor.

Sleutelwoorde: feminativum/vroulike persoonsname, woordvorming, LEKSIKOGRAFIE, TAALKULTUUR, EMANSIPASIE VAN VROUE, FEMINISASIE, GENDER-MORFOLOGIE, GENDER EN TAAL, AFLEIDING, PRAGMATIEK

1. Introduction

Feminine personal nouns, their stylistic value, normative assessment, and - more broadly - ways of expressing information about the feminine gender in the Polish language have been debated on for over 120 years. The earliest discussions on the topic are known, for instance, from linguistic periodicals from the beginning of the 20th century: Jezyk Polski [The Polish Language] and Poradnik Jezykowy [A Language Guide], and the most recent analyses have been presented by Karamanska and Mlynarczyk (2019), Kielkiewicz-Janowiak (2019), Szpyra-Kozlowska (2019a, b). During the last twenty years, quite a few linguistic monographies have been devoted to the complex issue of feminine personal nouns in Polish, including: Malgorzata Karwatowska, Jolanta Szpyra-Kozlowska: Lingwistyka plci. Ona i on w jezyku polskim [Gender Linguistics. She and He in the Polish Language] (2005); Marek Lazinski: O panach i paniach. Polskie rzeczowniki tytularne i ich asymetria rodzajowo-plciowa [On Men and Women. Polish Titular Nouns and Their Sex/Gender Asymmetry] (2006); Marta Nowosad-Bakalarczyk: Plec a rodzaj gramatyczny we wspólczesnej polszczyznie [Natural and Grammatical Gender in Contemporary Polish] (2009); Katarzyna Dembska: Tendencje rozwojowe polskich i rosyjskich nazw zawodowych kobiet na tle jezyka czeskiego [The Development Tendencies in Polish and Russian Female Profession Names within the Context of the Czech Language] (2012); and Agnieszka Malocha-Krupa: Feminatywum w uwiklaniach jezykowo-kulturowych [Feminitives and Their Linguistic and Cultural Entanglements] (2018). For a very long time now, feminine personal nouns have belonged to the standard repertoire of issues igniting contentious, frequently affective debate, dependent on numerous extra-linguistic parameters. That is why on 25 November 2019 the Council for the Polish Language (a consultative and advisory institution with regard to the use of the Polish language, established in 1996 by the Executive Board of the Polish Academy of Sciences (PAN)) published a communique on feminine forms of names of professions and titles, in which they state as follows:

The right to use feminine personal nouns should rest with the speaker, and one should remember that along with recently publicised calls in the media for creating them, there exists some resistance against them. Not everyone will refer to a woman as goscini [a hostess] or profesorka [a professoress], even if she herself explicitly voices such an expectation. The Council for the Polish Language at the Executive Board of PAN recognises that Polish needs a more expanded, possibly full symmetry of masculine and feminine personal nouns in its vocabulary. (http://www.rjp.pan.pl/index.php)

In my research - to which this article refers - I apply the notion of feminati-vum both to the category of nomina feminativa (an open set of forms) and its individual textual representations. I define the latter as a linguistic form that is a synthetic (one-word) name of a woman, containing a morphological (suffixal or paradigmatic) indicator of femininity. My reflection, which arises from more than a dozen years' excerption of feminine material and its scientific examination, primarily focuses on designations that are synthetic names of female professions, titles, academic degrees, social statuses (sometimes I also analyse feminine possessive names, surnames of wives and daughters, as well as attributive names).

2. How we explicate information about gender in the Polish language

From the perspective of the word-formation system of the Polish language, feminine personal nouns are derived from masculine derivational bases by taking various suffixes: the most productive -ka (e.g. nauczyciel->nauczyciel-ka [a male/female teacher], student - student-ka [a male/female student]), -ini/ -yni (przodek->przodk'-ini [a male/female ancestor], wydawca->wydawcz-yni [a male/ female publisher]); as well as some less frequent ones such as: -ica/-yca (aniol->aniel'-ica [a male/female angel]), -ina/-yna (hrabia->hrab'-ina [a count/a countess]), -anka (kolega->kolez-anka [a male/female friend]), etc. Nowadays, more and more feminine personal nouns are being formed by adding the paradigmatic formative -a to masculine forms such as przewodniczacy, ksiegowy, alimenciarz, doktor, maestro, minister. This is how the traditional uses were formed: przewodniczac-a [a chairwoman], ksiegow-a [a female accountant], as well as: alimenciar-a [a non-working woman who lives off maintenance money], doktor-a [a female doctor], maestr-a [a female maestro], ministr-a [a female minister], which are to be found in discourses of pro-gender-equality circles.

The trend to designate women in a way that communicates information about their gender derivationally, which has been discussed above, is competing with the concealment of that information in generic forms such as: doktor [a male/ female doctor or physician], klient [a male/female customer], minister [a male/ female minister], pacjent [a male/female patient], prezydent [a male/female president] that are used to refer to both genders. There is still another trend - an intermediate, universally approved one, which consists in creating analytic constructions: the form of address pani [madam] combined with a noun which is shared by the genders, e.g. pani minister [madam minister], pani doktor [madam doctor], pani prezydent [madam president]. The above nominating techniques, i.e. derived personal feminine nouns, the use of gender neutral nouns, and the use of analytic constructions are competing with each other, with the second and third models being predominant in the case of jobs, professions, functions and academic degrees regarded as prestigious. Since 1989 (a period of political and cultural transformation and a transition from a communist to a democratic system in Poland), the models have been attracting criticism from persons from pro-gender-equality circles. In line with the idea of gender-and-sexual symmetry in language, which they promote (Karwatowska and Szpyra-Kozlowska 2005), they propose that the feminine form should be derived from each masculine one, and they are using more and more synthetic feminine personal forms; often those are innovative constructions, not accepted by the customary norm, e.g. detektywka [a female detective], geniuszka [a female genius], hydrauliczka [a female plumber], kibicka [a female fan], krótkowidzka [a short-sighted woman], majorka [a female major], osiedlenczyni [a female settler] or rabusia [a female robber], and falling outside codified Polish. Apart from the existence of systemic, derivational solutions, information about gender in Polish can also be expressed inflectionally, by combining the exponent of femininity with inflected parts of speech:

- an adjective: nowa podsekretarz [a new female undersecretary], znakomita minister [an excellent female minister], badz wrazliwa [be sensitive (spoken to a woman)];

- an inflected participle: wybierana przedstawicielka [an elected female representative], interesujaca kobieta [an interesting woman], dominujaca prezydent [a dominating female president] (or, innovatively, prezydentka [a female president]);

- a pronoun/possessive: jej praca [her work], tamte osadniczki [those female settlers], owa nauczycielka [that female teacher];

- a verb: tak zadecydowalas [this is what you decided (spoken to a woman)], one przywolywaly [they summoned (about women)], czytelniczka napisala [a female reader wrote], Lila zglosila [Lila (a female name) reported].

That way of introducing information about gender is particularly valuable, when a given masculine personal noun does not lend itself to creating a feminine personal form that would gain universal approval. For example, standard Polish widely accepts the structure like

Lekarz prowadzaca mi zalecila [The lead doctor prescribed (it) to me],

in which there is no agreement between the subject and the predicate (lekarz zalecila) and between the subject and its designation (lekarz prowadzaca). Here, the noun is used in generic reference, and the morpheme of the participle and the verb function as exponents of information about femininity - in both cases, it is the inflectional ending -a. On the other hand, if we decide to derive a feminine personal noun from the masculine (lekarka [a female doctor]), the syntactic agreement will be preserved, but the utterance will be marked as colloquial:

Lekarka prowadzaca mi zalecila [The female lead doctor prescribed (it) to me].

With reference to a man, the corresponding utterance has the form:

Lekarz prowadzacy mi zalecil [The lead doctor prescribed (it) to me].

Here, the noun lekarz and the participle prowadzacy [lead] that describes it are in agreement, typical of Polish syntax, just like in the structure

lekarz zalecil [the doctor prescribed].

Sometimes also the failure to inflect a noun indicates femininity.

Spotkam sie z lekarz [I will see a female doctor] (not-inflected) vs.

Spotkam sie z lekarka [I will see a female doctor] (inflected, with suffixal derivation).

Wywiad z minister [An interview with a female minister] (not inflected) vs. Wywiad z ministra/ministerka [An interview with a female minister] (ministra and ministerka are forms proposed by pro-gender-equality circles and currently not in universal use).

As shown above, a user of the Polish language has at their disposal a plethora of morphological means that expose information about femininity.

3. From the 19th-century emancipatory breakthrough to the second decade of the 21st century

Today, the most heated discussions centre around word-formation techniques: the (in)ability to derive feminine personal nouns. Researchers are pointing out that the strategy for the derivation of feminine personal nouns has been productive for centuries (Klemensiewicz 1957: 106, 102; Kreja 1964: 129; Lazinski 2006: 247-248; Dembska 2012: 21-22), but its productivity was boosted after 1989 thanks to ideas and actions of the feminist and pro-gender-equality circles, who propose that feminine personal forms be derived from each masculine one. Historically, its creations of female names led to fewer normative doubts at the turn of the 20th century than they do today (cf. Wozniak 2014; Karamanska and Mlynarczyk 2019; Malocha-Krupa 2018a).

When looking at the history of functioning of the feminine personal noun category, it is noticeable that its products appear in texts with a changing frequency, dependent on the ideology prevailing at the time, the adopted (or imposed) system of values, typical or characteristic of a given communicative community. Sometimes feminine personal nouns are omitted in communication (invisibility of women), while on other occasions their presence in the discourse is marked by high frequency. It happens when, for some reason or another, the gender parameter becomes communicatively relevant, in many cases, from the linguistic perspective, approaching textual redundancy (that excess of information about gender is one of the determinants of contemporary texts of pro-gender-equality circles). That is because feminine personal nouns belong to a word-formation category whose products are clearly and in many respects dependent on political and cultural factors. The increased productivity of the formations in question can be associated with the prevailing sociocul-tural trends and ideologies: once the emancipation of women, after WWII - social realism, and after 1989 - feminism (exemplification and analysis of the phenomenon are presented in the monograph: Malocha-Krupa 2018a).

3.1 The history of the functioning of feminine morphological structures can be divided into three periods. From the 2nd half of the 19th century, emancipatory ideas, contributing to women's increased presence in public and professional life, affected derivation of feminine personal noun innovations. Material excerpted from the Lviv-based fortnightly magazine 'Ster' (the editions from the years 1895-1897) indicates that the biggest number of new feminine personal forms belonged to two lexico-semantic fields. Those were names of positions of power (60% of the new language units, e.g. inspektorka [a female inspector], ordynatorka [a female department head]), names of professions and functions requiring tertiary education (59% of the new language units, e.g. architektka [a female architect], weterynarka [a female veterinary surgeon]). The names of the professions that women entered which came into use after the emancipation of women had started have been raising stylistic and word-formation doubts more often than those of the occupations and professions that women had traditionally followed (the lexical innovation rate of the latter amounts to 0%).

Analysis of the texts from the fortnightly 'Ster' reveals certain analogies with contemporary phenomena similar to the ideas of the gender equality discourse. It can be concluded on the basis of how nouns are worded in respect of the gender category (e.g. wlasciciel/wlascicielka [a male/female owner], czytelnik/ czytelniczka [a male/female reader], wirtuoz/wirtuozka [a male/female virtuoso], wystawca/wystawczyni [a male/female exhibitor]) that the communicating parties felt there was a need to differentiate the two gender categories, and quite often feminine personal forms were derived from masculine ones. Another manifestation of the productivity of the word-formation category in question was the existence of variants within it - linguistic formations performing a similar function in a given period of time and competing with each other for the same position within the language system. The Polish language of the second half of the 19th century had many instances of semantic doubles referring to names of women's professions (e.g. ponczoszniczka/ponczoszarka [a female stocking maker], krawcowa/krawczyni [a female dressmaker], skrzypaczka/skrzypicielka [a female violin player]).

Discussions about the stylistic value of many names should be regarded as the first outcome of the achievements of women's emancipation (this is attested to by the earliest linguistic periodicals: Poradnik Jezykowy and Jezyk Polski). Women, having gained election rights in 1918, in the newly reborn Poland, freed from the rule by the three partitioning countries, began to demand appellation corresponding to that of men. Gradually, they started to reject possessive suffixes, traditionally combined with surnames of maidens and wives (traditionally: pan Malocha [Mr Malocha], his wiie->Malosz-yna, his daughter->Malosz-anka; pan Nowak [Mr Nowak], his wife->Nowak-owa, his daughter->Nowak-ówna), and, consequently, seeking the same designation as that of men (today only: pani Malocha [Ms Malocha], pani Nowak [Ms Nowak]), also as regards names of professions, which led to a weakening of the traditional derivational models and the strengthening of the trend to use some names of professions and academic titles generically. The published language use recommendations emphasising the need to accept and follow the regular word-formation patterns in Polish by deriving feminine personal nouns from masculine bases also evolved in the first half of the 20th century. When Poland regained its independence, the direct threat to the existence of its language and culture disappeared, and a relaxation, even if a partial one, of the language-tradition relationship and an opening to new communicative trends became possible. The fight to preserve the language thanks to its strict adherence to tradition was no longer the fundamental normative criterion. Increasingly, linguists started to support gender-neutral uses that were becoming more and more popular, instead of traditional solutions consisting in deriving feminine personal designations.

3.2 After WWII, the richness of the feminine lexis was a result of conscious propagandistic efforts by the authoritarian state, in which the equality of men and women was one of the slogans of Marxist-Leninist ideology. The new economic and political reality, the Polish People's Republic, demanded a new model of femininity. It was popularised by means of poster images, magazine covers, newsreels, one-off prints, literature and art. That 'poster image of a woman', saturated with ideological motifs, calling for taking on any social challenge, promoting equal access to work and women's professional mobilisation, often in jobs which were traditionally regarded as manly was accompanied by specific linguistic activities. Language was turned into a carrier, transmitter and cumulator of pragmatic values, propagated and controlled by the centralised communist apparatus that existed in the Polish People's Republic. To that aim, new feminine personal forms were derived, including gwinciarka [a female thread maker], hutniczka [a female steelworker], instalatorka [a female installer], lutowaczka [a female solderer], spawaczka [a female welder], which I refer to as propagandistic labels of socialist feminism. Their feminine personal grammatical structure was meant to persuade women (the persuasive function) that because the authorities were addressing them directly, they were becoming important participants in civic life. The introduction of feminine personal nouns (to replace previous generic appellations) in the state-monopolised mass media was also intended to make it easier for women to identify with the jobs and positions the authorities were actively promoting (the identifying function). Being an expression of designation of the new, indoctrinated work reality, desired by the state-building apparatus, the feminine derivates validated its authenticity (the magical function). The above conclusions are based on an analysis of a corpus of texts from some newspapers and magazines published in the years 1946-1956 (primarily 'Przyjaciólka', 'Trybuna Ludu', 'Kraj', 'Mucha', 'Moda i Życie', 'Naprzód Dolnoslaski' and 'Żolnierz Polski') that I have collected.

The belief in the equality of men and women, grounded in the social awareness of the Polish People's Republic, was understood as 'one and the same', i.e. 'being the same under law and at work', in line with the propagandist and constitutional image of emancipation of women. For that reason, the professional appellations of men and women were gradually becoming uniform and assuming an identical, masculine form, connoting appropriate prestige, formality, domination, higher rank and normativity. The word-formation indicators of femininity were disappearing from communication, while at the same time the trend to use the same names to refer to both genders strengthened. This conclusion particularly relates to formations denoting a certain social hierarchy (names of positions of authority, such as ambasador [ambassador], general [general], kanclerz [chancellor], marszalek [marshal], minister [minister], premier [prime minister], prezydent [president]) as well as occupations or statuses recognised as prestigious (adwokat [advocate], prokurator [attorney], prezes [chairperson]).

3.3 Because of the trend that grew in the subsequent decades of the 20th century towards generic usages and in the light of a declining productivity of the feminine personal noun category, after the political and cultural breakthrough of 1989 (a redevelopment of the political system, the first free, democratic elections to the Polish parliament), the feminist and leftist circles started to promote the idea of linguistic-gender symmetry and of deriving a semantically equivalent feminine personal form from each masculine one. This idea was and still is informed by the belief that it is worth extracting from the linguistic void something that which is socially relevant, which explicates the gender of communicating parties. And this factor in connection with postmodern constructs, identity attitudes and anti-discriminatory concepts, has become a communica-tionally pertinent parameter and a relevant element of the new, equality-conscious language etiquette (Malocha-Krupa, Holojda, Krysiak and Pietrzak 2013). The feminist theories (especially those inspired by the second wave of feminism), both those literary-science-oriented and those within the area of gender linguistics, focus, among other things, on the connection between the symbolic (linguistic) and social orders. They regard language and communication as significant indicators of patriarchal attitudes, tools for gender-based distribution of social roles and statuses, reservoirs of ways of perception and categorisation of information about gender, which - in this study perspective - appear as asymmetrical and hierarchical. They also indicate that all masculine is privileged at the expense of the feminine - subordinated to masculine notions, ways of perception, designation and valuation. Such a critical analysis of linguistic and discursive reality is related to a more or less directly explicated reformative approach to manifestations of the privileged position of either gender in the symbolic order, its exclusion or depreciation. Thus, the study of gender linguistics and feminist criticism is of a teleological nature - through description, analysis, and subsequent reinterpretation of areas that require change, they attempt to deconstruct the traditional conceptual or grammatical system and to establish a new one, based on the concept of equality. The above-mentioned analyses and communicative practices aim to promote the 'coming out of silence' (primarily by women), the naming of the unnamed, the finding of one's own voice, and lexical and semantic symmetry in designating men and women. Projects developed from the feminist perspective, aimed at balancing social relations through making changes to language also left their mark on the Polish language and have been influencing its development for nearly three decades. The ideas of gender linguistics and feminist criticism of language initiated sui generis activation of the lexical and word-formation layers of Polish which relate to nominative operations on the feminine category. Most probably the history of productivity of feminine personal nouns would have been different if not for the involvement of feminist and pro-equality circles in propagating the idea to complement the existing lexical and semantic gaps as regards designating women, particularly their professions, positions and social functions. That is probably why there is a widespread belief that 'feminine personal nouns have been invented by feminists', 'bored female academicians' - however, as analysis has shown: Kreja 1964; Wozniak 2014; Malocha-Krupa 2018a; Karamanska and Mlynarczyk 2019; Mlynarczyk 2019, such nouns had been an important part of the word-formation system of the Polish language earlier. As Prof. Jan Miodek has been saying during his lectures at Wroclaw University for the last few decades: 'Poles' natural word-formation reflex means creation of feminine names'. Feminist movements have only managed to restore a portion of the traditional feminine personal lexis, subjecting some of the old names to neosemantisation, melioration of their meaning (e.g. adwokatka [a female advocate], mecenaska [a female lawyer], ministerka [a female minister]), and setting in motion derivation of innovative formations, required to meet the new naming needs with a view to achieving the equality vision between the symbolic linguistic reality and the extra-linguistic one. The return of feminine personal nouns to general Polish, especially that used in journalism, is an ongoing process. We have observed a stylistic reclassification of many a formation that was originally used in a limited environment or was perceived as marked in general Polish. However, numerous feminine personal nouns, especially those naming degrees, professions or statuses characterised by high social prestige, are regarded by a majority of speakers as stylistically non-neutral. They are thus not accepted, and are often perceived as reflections of feminist or pro-gender-equality views. The nouns are again associated with ideology, although they are also often alleged to sound depreciatory or humorous.

4. Codification of feminine person nouns as a challenge to lexicography

Today, we are seeing a revival of feminine personal nouns (feminine, suffixal derivation) in the Polish language used by pro-gender-equality circles, efforts to expand the limits of normativeness, the overcoming of the limits of codification, which are affecting the condition of the general Polish language. Usages with both-gender references are competing with increasingly more frequent feminine personal noun updates. For years we have seen discussions on their functionality, acceptability and stylistic value (cf. e.g.: Lazinski 2006, Holojda 2013, Kielkiewicz-Janowiak 2019, Szpyra-Kozlowska 2019a, b) as well as the ability to examine them in detail. As one of the researchers has noticed:

In a country with rather conservative attitudes, both to gender roles and language use norms, it might be sensible to dissociate the issue from the political agenda it is in fact part of. (Kielkiewicz-Janowiak 2019: 167)

The issue regarding feminine personal nouns is neither new nor one-dimensional. Undoubtedly, dictionaries of general Polish have failed so far to rise to the challenge to provide a fuller, objective codification of the language units in question. Their position in contemporary lexicography is 'indefinite, uncertain' (Krysiak 2016: 84). Dictionary authors either ignore them or do not agree as to their stylistic value, assigning a stylistic qualifier to them, or the stylistic value assigned by the authors is not accepted by all parties to communication. Patrycja Krysiak, author of, for instance, a monograph Feminine Names in Contemporary Polish and French Lexicography. Comparative Analysis of Selected Most Recent Polish and French General Dictionaries (2020), already noticed in one of her earlier publications that: 'exclusion of feminine personal nouns by lexicographers is causing language users to treat them with a considerable degree of uncertainty - after all, a dictionary is the basic source of knowledge about language for non-specialists' (Krysiak 2016: 89). On the one hand, they often assume that if a given word is not to be found in a dictionary, it should not be used in communication, and, on the other hand, conscious communication participants are aware of the need to adjust their lexical choices to the principles of communication that are changing right in front of us, particularly as regards the gender-equality etiquette. There is also a growing demand for explicit knowledge, recipelike knowledge regarding which words should be used in the public space and how, and this demand is enormous. This is attested by questions sent to language advisory services and numerous emails asking for resolving normative doubts that I receive - they might be used as a basis for a language guide on how to communicate gender-equality today.

Consequently, lexicographers are faced with an uneasy task. They recognise the dynamism of change in the habits regarding communication about gender, the social demand for their description and codification. However, the lexical material relating to the phenomenon is extremely difficult to describe unambiguously and in a simple way. At the present stage of changes in the normative and gender-equality awareness, in the early 2020s, one should even ask whether it is at all possible to codify and stylistically qualify women's designations in a way that would be fully scientific, objective, free from any individual or subjective opinions. I believe not. Any specific form is only included in codification if someone decides to do so, using of course some previously adopted criteria.

This is attested to by discussions on stylistic value of numerous feminine personal nouns: names of positions of power (dyrektorka [a female director], ministerka [a female minister], prezydentka [a female president]), names of professions (nauczycielka [a female teacher], prawniczka [a female lawyer], psy-cholozka [a female psychologist]), and characterising names (interpretatorka [a female interpretator], przodkini [a female ancestor], goscini [a female guest]). Their use and valuation depends on many parameters: the communicative situation, an attitude to language, views on social reality, sensitivity to gender-equality issues, as well as aesthetic sense and associations that a given form triggers.

5. A dictionary of female nouns

The doubts referred to above and lexicographers' inconsistency in recording (or omission of) feminine personal forms led to the idea to publish a 'Dictionary of Polish Female Nouns'. Several female linguists from Wroclaw University, Poland: Katarzyna Holojda-Mikulska, Patrycja Krysiak, Marta Sleziak, the author of this article, Agnieszka Malocha-Krupa, undertook a pioneering attempt to scientifically tackle the issue, and published in 2015 Slownik nazw zenskich polszczyzny [Dictionary of Polish Female Nouns; further on referred to as SNŻP].

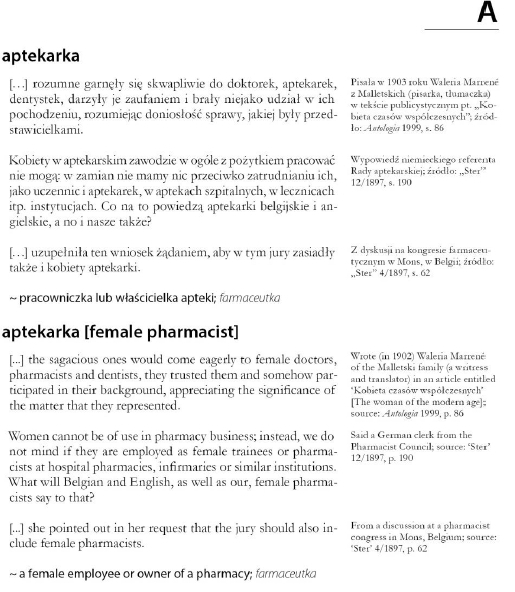

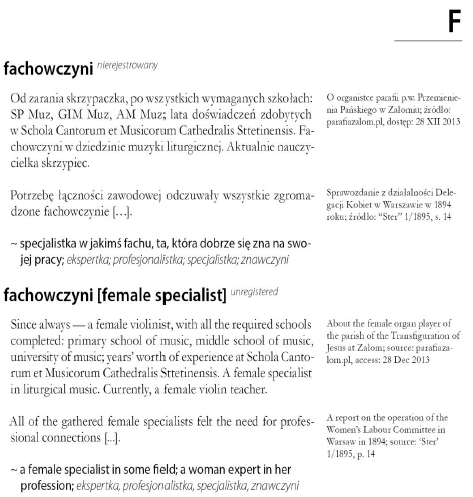

The concept of the dictionary relates to 'the typological truth about the centuries-long richness of the Polish language in terms of derivation processes within the category of femininity' (Miodek 2017: 172). It contains feminine lexemes from texts written during the period spanning the second half of the 19th century and the present times.

This is the first dictionary in Polish lexicography to only contain feminine structures, in linguistics referred to as feminine personal nouns (cf. Sec. 1). Before, feminine personal nouns were made part of other publications, found their way into language use guides and normative books, for instance works devoted to word-formation trends in Polish. However, there had been no special publication recording authentic uses of feminine personal nouns in Polish, excerpted from written texts.

The total number of the incorporated lexical items amounts to 2,103, including 422 (i.e. 20.07%) that until 2014 had not appeared in any dictionaries of general Polish language (that group has both some innovative formations, like bodypainterka [a female bodypainter], bookcrosserka [a female bookcrosser], brafit-terka [a female bra-fitter], castingowiczka [a female participant in a casting], copywriterka [a female copywriter], forumowiczka [a female forum participant], ghostwriterka [a female ghostwriter], headhunterka [a female headhunter], japiszonka [a female yuppie], lobbystka [a female lobbyist], performerka [a female performer], researcherka [a female researcher], senselierka [a female smell expert], shopperka [a female shopper], slamerka [a female participant in a poetry slam], streetworkerka [a female streetworker], trendsetterka [a female trendsetter], vlogerka [a female vlogger], and some traditional ones, which for various reasons had not been codified in other dictionaries, e.g. eksperymentatorka [a female experimenter, ratowniczka [a female rescuer], ubezpieczycielka [a female insurance agent]). SNŻP is, above all, a source of knowledge about language and its transformations related to changing reality. It presents feminine personal nouns used in public discourse: old ones and nearly forgotten ones (swiekra [the husband's mother], zelwa [the husband's sister]) as well as some entirely new ones (couchsurferka [a female participant in couchsurfing], galerianka [a young female student offering sexual services at a shopping centre]); referring to professions that are rare or non-existent today (ponczoszniczka [a female stocking maker], sekserka [a female that determines sex of chicks]) or those that have appeared recently (bodypainterka [a female bodypainter], profilerka [a female profiler]); referring to women living in the peculiar reality of the Polish People's Republic (formiarka [a female form maker], traktorzystka [a female tractor driver]) or to social roles that never change (matka [a mother], zona [a wife]).

The publication constitutes a scientific description of a section of reality that is reflected in language. It is based on the principle of an objective search for and recording of language forms that fulfil appropriate criteria, and the editing approach was to adopt a method of description of the gathered material that would be free from any direct valuation of each entry. The over-riding goal was to show the richness of feminine personal nouns, their diversity, variable stylistic value that sometimes comes to light, particularly well visible in the case of nouns attested to with 19th-century uses.

The dictionary may be treated as an open file and a collection of word forms to choose from when composing one's own texts, adopting a traditional approach or a pro-gender-equality one towards the changing social reality, open to linguistic innovation or making use of the mine of nouns, often forgotten ones. It can also be used for checking usage contexts and the presence of feminine personal nouns in official texts. The book can also be looked upon as a guide to a world in which women play an important role, and its reader may find out, from the carefully-considered selection of quotations, how their social roles have changed, how the professional and family life they create has evolved, and how our reality (not only that of women) has changed over the years.

5.1 Some of the lexicographical assumptions

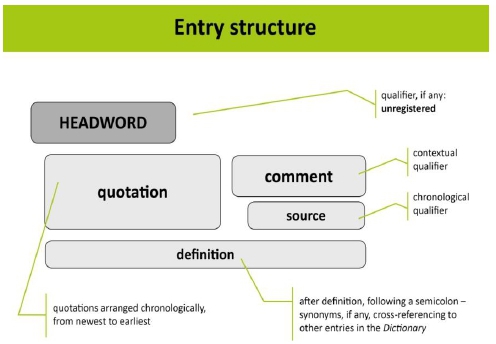

Slownik nazw zenskich polszczyzny uses an innovative lexicographical method, particularly as regards the layout of entries and introduction of direct and indirect description qualifiers. It was assumed that the quotation, text and discourse would play the primary role; therefore, the approach was called a discourse-centred method. In it, a lexeme is directly highlighted by a quotation, and a quotation by a comment, so the definition of the lexeme is given at the end - sometimes with synonyms as cross-references to other entries in the collection of texts. The definition constitutes the last structural element of an entry. This solution does away with the traditional order and the linearity of the sequential, expected, predictable elements of a typical microstructure of an entry, but it is conducive to involving the reader in the text and making them understood on their own the meaning of the lexeme and how it is used on the basis of its textual representation.

This concept was appreciated by the scientific reviewers of the dictionary. Prof. dr hab. Miroslaw Banko wrote:

I also support the idea of the dictionary speaking to the reader above all in the voices of the quoted authors and authoresses, often well-known public figures, either living now or a hundred years ago. Thanks to the quotations, the book gains credibility and historical depth, and involves the reader intellectually as well as emotionally.

The method adopted is described both in the Introduction to the dictionary, and in some published articles: Sleziak 2018; Malocha-Krupa 2018b.

The publication constitutes a scientific description of a section of reality that is reflected in language. Because of the adopted method (a descriptive, not a prescriptive dictionary), it documents the variety and productivity of feminine personal noun formation.

Below - illustratively - I present two examples of entry-level articles from SNŻP:

5.2 Consequences of descriptivism

The dictionary's descriptiveness results not only from the democratic view of the language that is close to its editors but also from the fact that in many cases at the present stage of the development of the Polish language, when various ways of introducing information about the female gender into text are competing with one another (cf. Section 2) and parties to communication have varying approaches and axiological systems (cf. Section 4), the lexicographer who is not always objective is unable to unambiguously and accurately establish the stylistic value of a given feminine personal noun. In the case of nouns that are currently stylistically suspicious to some users this seems impossible. Frequently, in the same contexts, text types/genres and discourses, both a generic and a feminine personal form can be used.

Many people will regard feminine personal nouns such as kierowniczka [a female manager] or dyrektorka [a female director] as non-neutral stylistically and will qualify them as colloquial, while other people, not always those in favour of gender equality, will use such words to introduce themselves in formal situations, will use them in writing, put on business cards or websites of the institution they represent (i.e. in official language contact situations). In the normative awareness of such people, such forms are neutral stylistically.

That is why in the case of SNŻP the decision was made to do away with - as worded by Marta Sleziak (2018: 254) 'arbitrary normative solutions'. As far as stylistically doubtful forms are concerned, the reader will have to choose the form themselves - either the suffixal one, which they will find in the dictionary (e.g. analityczka [a female analyst], dyrektorka [a female director], prezeska [a female president] - stylistically doubtful to some people), or the both-gender variant, which - in line with the adopted assumptions - are not included in the dictionary. Plenty of stylistic information can be derived from the material documentation (quotations) provided by the authors on purpose, as well as commented contexts in which a given feminine personal noun is used and its sources (Sleziak 2018).

6. In conclusion

The publication of SNŻP confirmed the existence of a significant social demand for linguistic opinions on the designations of women as regards their occupations, positions, public functions and academic degrees. Two days after the meet-the-authors session the dictionary was out of print, and the reprint was sold out within several weeks. Dozens of invitations to give lectures, numerous telephone calls and e-mails requesting interviews, as well as a constant flow of requests for expert advice (primarily by e-mail) on feminine personal nouns, their creation and stylistic value attest to the lively reception of the publication.

Those who have had a careful look at SNŻP (Przeglad Uniwersytecki 2016(2)) have recognised the values of the dictionary, e.g. that arising from the fact that 'although it focuses on a selected, single word-formation and semantic category, i.e. female personal nouns, it shows their broad textual, pragmatic and sociocultural background'. (Rzymowska and Poprawa 2016: 36), The material collected in it enables you to track the paths of the history of the feminine personal noun category - its disappearances and reappearances in Polish. The publication's reviewers have also expressed their appreciation for the adopted word-formation techniques, thanks to which - in their opinion - the SNŻP collection of texts can be an inspiration and an object of further lexical and semantic studies, both into feminine personal nouns functioning in official language, and into neologisms and nonce words reflecting current cultural processes.

The dictionary's authors are now working on a new, expanded edition of SNŻP, which will introduce a modified entry structure.

References

Dembska, K. 2012. Tendencje rozwojowe polskich i rosyjskich nazw zawodowych kobiet na tle jezyka czeskiego [The Development Tendencies in Polish and Russian Female Profession Names within the Context of the Czech Language]. Torun: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Mikolaja Kopernika. [ Links ]

Holojda, K. 2013. Jak Polki postrzegaja feminatywy? [What Do Polish Women Think about Feminine Personal Nouns?] Malocha-Krupa, A., K. Holojda, P. Krysiak and W. Pietrzak. 2013. Równosciowy savoir-vivre w tekstach publicznych [Gender-equality savoir-vivre in Public Texts]: 101-105. Warsaw: The Chancellery of the Prime Minister, Office of the Government Representative for Equal Treatment. http://www.ifp.uni.wroc.pl/data/files/pub-9470.pdf

Karamanska, M. and E. Mlynarczyk. 2019. Komponenty eksponujace ceche zenskosci w nazwach stowarzyszen II Rzeczpospolitej [Exponents of the Feature of Femininity in Names of Associations in the Second Republic of Poland]. Annales Universitatis Paedagogicae Cracoviensis 283. Studia Linguistica 14: 67-78. [ Links ]

Karwatowska, M. and J. Szpyra-Kozlowska. 2005. Lingwistyka plci. Ona i on w jezyku polskim [Gender Linguistics. She and He in the Polish Language]. Lublin: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Curie-Sklodowskiej. [ Links ]

Kielkiewicz-Janowiak, A. 2019. Gender Specification of Polish Nouns Naming People: Language System and Public Debate Arguments. Slovenscina 2.0: Empirical, Applied and Interdisciplinary Research 7(2): 141-171. https://doi.org/10.4312/slo2.0.2019.2.141-171 [ Links ]

Klemensiewicz, Z. 1957. Tytuly i nazwy zawodowe kobiet w swietle teorii i praktyki [Women's Professional Titles and Names in Theory and Practice]. Jezyk Polski 37(2): 101-119. [ Links ]

Kreja, B. 1964. Slowotwórstwo nazw zenskich we wspólczesnym jezyku polskim (wybrane zagadnienia) [Word Formation of Polish Female Personal Nouns (Selected Issues)]. Jezyk Polski 44(3): 129-140. [ Links ]

Krysiak, P. 2016. Feminatywa w polskiej tradycji leksykograficznej [Feminine Personal Nouns in Polish Lexicographical Tradition]. Rozprawy Komisji Jezykowej WTN [Papers of the Language Committee of Wroclaw Scientific Association]. Wroclawskie Towarzystwo Naukowe, Yearbook 42: 83-90. [ Links ]

Krysiak, P. 2020. Nazwy zenskie we wspólczesnej leksykografii polskiej i francuskiej. Analiza porównawcza wybranych najnowszych polskich i francuskich slowników ogólnych [Feminine Names in Contemporary Polish and French Lexicography. Comparative Analysis of Selected Most Recent Polish and French General Dictionaries]. Wroclaw: Oficyna Wydawnicza ATUT. [ Links ]

Lazinski, M. 2006. O panach i paniach. Polskie rzeczowniki tytularne i ich asymetria rodzajowo-plciowa [On Men and Women. Polish Titular Nouns and Their Sex/Gender Asymmetry]. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN. [ Links ]

Malocha-Krupa, A. (Ed.). 2015. Slownik nazw zenskich polszczyzny [Dictionary of Polish Female Nouns]. Entries by: Holojda K., P. Krysiak, A. Malocha-Krupa and M. Sleziak. Wroclaw: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Wroclawskiego.

Malocha-Krupa, A. 2018a. Feminatywum w uwiklaniach jezykowo-kulturowych [Feminitives and Their Linguistic and Cultural Entanglements]. Wroclaw: Oficyna Wydawnicza ATUT. [ Links ]

Malocha-Krupa, A. 2018b. Opis leksykograficzny feminatywum. (Nie)mozliwosci zobiektywizowania [Lexicographic Description of Feminine Personal Nouns. (In)ability to Objectivise]. Banko, M. and H. Karas (Eds.). 2018. Miedzy teoria a praktyka. Metody wspólczesnej leksykografii [Between Theory and Practice. Methods in Contemporary Lexicography]: 151-165. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego.

Malocha-Krupa A., K. Holojda, P. Krysiak and W. Pietrzak. 2013. Równosciowy savoir-vivre w tekstach publicznych [Gender-equality savoir-vivre in Public Texts]. Warsaw: The Chancellery of the Prime Minister, Office of the Government Representative for Equal Treatment. http://www.ifp.uni.wroc.pl/data/files/pub-9470.pdf [ Links ]

Miodek, J. 2017. Slownik nazw zenskich polszczyzny [recenzja]. Dictionary of Polish Female Nouns [A Review]. Sojka-Masztalerz, H., M. Porawa and T. Piekot (Ed.). 2017. Obraz wojny w mediach, pamieci i jezyku [The Picture of War in the Media, Memory and Language]: 171-172. Oblicza Komunikacji [Facets of Communication] 10(2017). Wroclaw: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Wroclawskiego.

Mlynarczyk, E. 2019. Tendencje nazwotwórcze w chrematonimii spolecznosciowej II Rzeczypospolitej (na przykladzie nazw stowarzyszen) [Trends Related to Creating Names in Social Chrematonymy of the Second Polish Republic (Based on the Names of Associations)]. Onomastica 63: 209-226. https://onomastica.ijp.pan.pl/index.php/ONOM/article/view/78 [ Links ]

Nowosad-Bakalarczyk, M. 2009. Plec a rodzaj gramatyczny we wspólczesnej polszczyznie [Natural and Grammatical Gender in Contemporary Polish]. Lublin: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Curie-Sklodowskiej. [ Links ]

Rzymowska, L. and M. Poprawa. 2016. Portret kobiety w slowach zapisany [A Portrait of a Woman as Recorded in Words]. Przeglad Uniwersytecki 2016(2): 36-37. https://www.bu.uni.wroc.pl/sites/default/files/images/doc/PU_2016_02.pdf

Szpyra-Kozlowska, J. 2019a. "Premiera", "premierka" czy "pani premier"? Nowe nazwy zenskie i ograniczenia w ich tworzeniu w swietle badania ankietowego ['Premiera', 'premierka' or 'pani premier'? New Female Personal Nouns and Constraints on Their Formation in the Light of a Questionnaire Study]. Jezyk Polski 99(2): 22-40. https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=780107 [ Links ]

Szpyra-Kozlowska, J. 2019b. Feminitives in Polish: A Study in Linguistic Creativity and Tolerance. Bondaruk, A. and K. Jaskula (Eds.). 2019. All Around the Word: Papers in Honour of Bogdan Szymanek on his 65th Birthday: 339-364. Lublin: Wydawnictwo KUL.

Sleziak, M. 2018. Prymat leksykograficznego egzemplum i jego konsekwencje dla hasla - na przykladzie Slownika nazw zenskich polszczyzny [Primacy of Lexicographical Example and Its Consequences for the Entries - On the Example of the Dictionary of Polish Feminatives]. Banko, M. and H. Karas (Eds.). 2018. Miedzy teoria a praktyka. Metody wspólczesnej leksykografii [Between Theory and Practice. Methods in Contemporary Lexicography]: 245-255. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego.

Wozniak, E. 2014. Jezyk a emancypacja, feminizm, gender [Language and Emancipation of Women, Feminism, Gender]. Rozprawy Komisji Jezykowej Lódzkiego Towarzystwa Naukowego [Papers of the Language Committee of Lódz Scientific Association] 60: 295-312. http://www.rjp.pan.pl/index.php [ Links ]