Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Lexikos

On-line version ISSN 2224-0039

Print version ISSN 1684-4904

Lexikos vol.30 Stellenbosch 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.5788/30-1-1591

ARTICLES

On Pronunciation in a Multilingual Dictionary: The Case of Lukumi, Olukumi and Yoruba Dictionary

De la Prononciation dans un Dictionnaire Multilingue: Le Cas du Dictionaire Lukumi, Olu kumi et Yoruba

Joy O. UguruI; Chukwuma O. OkekeII

IDepartment of Linguistics, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria (joy.uguru@unn.edu.ng)

IIDepartment of Linguistics, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria (chukwuma.okeke@unn.edu.ng)

ABSTRACT

This study centres on reflecting the pronunciation of lemmas in a proposed multilingual dictionary of Lukumi, Olukumi and Yoruba. It shows how the differences and similarities in their pronunciation can be displayed in the proposed dictionary. Lukumi is spoken in Cuba while Olukumi and Yoruba are spoken in Nigeria. The parent language, Yoruba, was used as a reference point to highlight the etymology of Lukumi and Olukumi as well as to buttress their similarities. Two downloaded Lukumi wordlists making up 134 words were used to elicit information on Olukumi equivalents through oral interview. Twenty-two words are used as sample entries. Following Mashamaite's method of promoting the compilation of bilingual dictionaries between African languages, the study presents Lukumi as the source language while Olukumi and Yoruba are the target languages; English translations of the lemmas are shown. The pronunciation of the lemmas is given alongside their meanings and grammatical categories. No dictionary of any Nigerian language has pronunciation of headwords given; hence this study is a positive innovation; also, the display of pronunciation provides evidence of the similarities shared by the three languages. The transcription of the lemmas serves as a good learning aid for the language learners. The dictionary will go a long way to preserve the endangered Lukumi and Olukumi languages.

Keywords: lemma, olukumi, lukumi, yoruba, pronunciation, cognacy, LEXICOSTATISTICS, MULTILINGUAL DICTIONARY, NIGERIA

RÉSUMÉ

Cette étude met l'accent sur une réflexion à propos de la prononciation des lemmes dans un dictionnaire multilingue planifié incluant le lukumi, l'olukumi et le yoruba. Il montre comment les différences et similitudes dans leur pronon-ciation peuvent être présentées dans le dictionnaire en proposition. Le lukumi est parlé au Cuba tandis que l'olukumi et le yoruba sont parlés au Nigéria. La langue parente, le yoruba, a été utilisée comme point de référence pour mettre en évidence l'étymologie du lukumi et de l'olukumi ainsi que pour renforcer leurs similitudes. Deux lexiques téléchargés du lukumi, comprenant un total de 134 mots, ont été utilisés pour obtenir des informations sur les équivalents olukumi par le biais d'un entretien oral. Vingt-deux mots sont utilisés comme exemples d'entrées. Suivant la méthode de Mashamaite pour promouvoir la confection de dictionnaires bilingues entre les langues africaines, l'étude présente le lukumi comme langue source tandis que l'olukumi et le yoruba sont les langues cibles; des traductions en anglais des lemmes sont présentées. Les différentes prononcia-tions des lemmes sont présentées avec leurs significations et de leurs catégories grammaticales. Aucun dictionnaire d'aucune langue nigériane n'a de prononciation pour leurs entrées ou lemmes; cette étude est donc une innovation positive. Aussi, l'affichage de la prononciation apporte la preuve des similitudes partagées par les trois langues. La transcription des lemmes est une bonne aide à l'apprentissage pour les apprenants de langues. Le dictionnaire contribuera grandement à préserver les langues lukumi et olukumi qui sont menacées de disparition.

Mots-clés: LEMME, OLUKUMI, LUKUMI, YORUBA, APPARENTEE, LEXICOSTATISTIQUE, DICTIONNAIRE MULTILINGUE, NIGERIA

Introduction

Olukumi and Lukumi are spoken by Yoruba descendants in Delta state of Nigeria and in Cuba respectively. While Olukumi speakers are Yoruba descendants who migrated to the present day Delta state (Oshimili Local Government Area) of Nigeria, Lukumi speakers are descendants of Yoruba slaves taken to Cuba and Brazil. Olukumi is spoken in secluded communities like Ugbodu, Ukwunzu and others, hence most of their linguistic heritage has been maintained. Similarly, Lukumi has been maintained because it is mainly used for religious purposes. According to Mason (1997) Lukumi is an alternative term to Olukumi and means 'my friend'. They are similar, having originated from Yoruba, a major Nigerian language spoken in the South West zone. Lukumi has the code, ISO 639-3 luq. It is of the Niger Congo family, specifically of the Yoruboid subgroup. Olukumi, though it does not have a code yet, is also of Yoruboid subgroup. Both varieties are highly related to Yoruba as shown by scholars (Arokoyo 2012; Okolo-Obi 2014 and Anabaraonye 2018).

This paper focuses on indicating pronunciation in a multilingual dictionary with Lukumi as the source language and Olukumi and Yoruba as target languages. Also, in order to have wider readership English translations are provided since Lukumi and Olukumi are spoken in different continents, and the former is used internationally for religious and research purposes. The phonetic features of lemmas are shown for easy pronunciation by readers, especially second language speakers and learners.

We have adopted the method of Mashamaite (2001) who proposes presenting African languages as source languages. He laments that in South Africa, bilingual dictionaries on African languages have English or Afrikaans as the source language while the African languages serve as the target languages. He shows that there is no case where an African language is used as a source language except for bi-directional bilingual dictionaries. A similar situation can be found in Nigeria. Hence this study fills this gap, being a positive move to project an African language as a source language. Also, though there will be English translations in the proposed multilingual dictionary, the focus is on the three African languages, Lukumi, Olukumi and Yoruba.

Olukumi is not documented, written or studied in schools. Similarly, Lukumi is solely used orally for religious purposes. These situations will lead to the extinction of both languages. Hence the present study is a good step towards the preservation and use of Olukumi and Lukumi. Onwueme (2015) expresses fears that Olukumi could go extinct since its speakers bear Igbo names; Igbo is spoken in their neighbouring communities. Most Olukumi people are bilingual, speaking Igbo and Olukumi, hence the strong influence of Igbo. Concordia (2012) shows that Lukumi retains Yoruba features because it is mainly used for religious purposes. According to Schepens et al. (2013) more frequently used words tend to lose more characters than less frequently used words. Thus, the case of Olukumi which is used for daily activities is understood.

Importance of indicating phonetic features and cognates in dictionaries

According to Van Keymeulen (2003) lexicographers should not include more than they can handle in a dictionary to avoid inadequate management of the data. He however points out that the dictionaries he worked on have such microstructure as pronunciation, meaning, collocations and example sentences; they only include 'general vocabulary' and not terminologies. Though he opines that including elements of microstructure in the dictionary depends on the purpose of the dictionary, it is pertinent that information on pronunciation of the headwords be included in every dictionary since the users have the need to pronounce the words, irrespective of the purpose of the dictionary. Hence in this work, the pronunciation of the lemmas, alongside other macrostructural information, is provided.

Most dictionaries on African languages do not have phonetic transcriptions. This is evident in Igbo dictionaries (Williamson 1972; Blench 2013; Mbah et al. 2013). Some efforts made to include pronunciation in Yoruba dictionaries have not been efficiently done. Yai (1996) chooses to indicate pronunciation of Yoruba words using 'English spelling' in brackets. For example, the Yoruba word, Osúmarè has the pronunciation (oshoomanray). Similarly, Michelena and Marrero (2010) use Spanish spelling to indicate the pronunciation of Yoruba words in their own dictionary. This method of indicating pronunciation is not standard (not phonetic) and can be very misleading.

Rosenhouse (2018) shows that some Arabic language dictionaries have phonetic transcriptions. Nevertheless, these phonetic transcriptions do not always help the learner since his mother tongue affects the pronunciation of the second language. However, it is better that the dictionary gives the learner a guide on what the pronunciation of the lemmas is so as to reduce mispronunciation which is a major factor in misinterpretation of meaning. Vishnevskaya (2013) points out that phonetic transcription is important for lexicographic purposes. According to him, modern dictionaries, particularly those meant for bilinguals, should have phonetic information. Thus, the current study centres on developing a multilingual dictionary with phonetic details of the lemmas in the language varieties under study. The phonetic aspects help to identify lexical items that are related in the language varieties; this is a big aid to both the language speaker and the learner.

The indication of the pronunciation of the lemmas in a dictionary aids the learner to internalize the spellings and pronunciation of lexemes. According to Shoba (2001) the phonetic-phonological information on a lexical unit is the essential component of the dictionary entry because it facilitates the pronunciation of the word. In her evaluation of Nguni dictionaries, she discovers that the treatment of pronunciation information is inadequate and inconsistent. She concludes that though phonetic-phonological information is included in almost all types of dictionaries, its presentation is associated with certain problems. It is therefore important that a lexicographer understands the phonetic features of a language so as to be able to present them well.

Sobkowiak (2003) distinguishes between lexicographic phonetics and phonetic lexicography. He explains that lexicographic phonetics is phonetics as applied to the process of dictionary making. It centres on the presentation of accent, stress, dialectal variations and other phonetic features in the dictionary. On the contrary, phonetic lexicography centres on other phonetic issues, particularly the place and the role of pronunciation in dictionary compilation.

Mafela (2005) also reveals that adding etymology (cognacy and lexicosta-tistical facts) could be used to solve the problem of meaning discrimination in dictionaries. This is very pertinent in the case of Lukumi and Olukumi which sprang from the Yoruba language. Due to the long distance separating the two varieties, some words have lost their phonetic features; in such cases, only etymology, where reference is made to the parent language Yoruba, can establish any relationship. Hence Yoruba has been included in this study.

The purpose, functions, nature and typology of the planned dictionary

The earliest attempt at compiling Yoruba vocabulary was that of Crowther (1865). The present study is a prototype of what is being proposed since the list of words is limited. The main dictionary project will be more detailed, covering all areas of life communication. The proposed dictionary will be a Lukumi-Olukumi-Yoruba multilingual dictionary with English translations. There are examples of such dictionaries. According to Marello and Tomatis (2008) some of the earliest efforts in making trilingual dictionaries include that of Inglott Bey (1899) who compiled the dictionary of English homonyms with translations in Italian and French. This was done to help foreigners studying the English language.

Multilingual dictionaries enable thematic and alphabetic lookup. Mashamaite (2001) points out that the primary purpose of bilingual dictionaries is to assist speakers of various languages to learn one another's languages hence promoting multilingualism. He shows that bilingual dictionaries help users to perform the following: reading and listening; speaking and writing as well as translating. No doubt, if these roles can be achieved in the cases of Olukumi and Lukumi, then their preservation and spread is guaranteed. Mashamaite laments the lack of bilingual dictionaries between African languages; this is one of the gaps that the present study aims at filling.

Any modern dictionary derives its data from a corpus (Prinsloo and De Schryver 2009; De Schryver 2006); hence the compilers have to build and query an electronic corpus for the specific language(s) first. In the case of this study, both the online and offline data ought to be crosschecked for accuracy since the language varieties, Lukumi and Olukumi, are spoken in diaspora and the likelihood of influence by languages spoken in their environments is high. Hence care has been taken to crosscheck the collected data with Yoruba, their parent language.

Identifying the phonemes of the languages under study as well as those of the major languages that influenced them

Nota Bene: phonemes

Olukumi vowels: /i/, /u/, /u/, lil, / i/, /u/, /e/, lol, ld, lil, hl, hl, /a/, lal.

Olukumi consonants:

Plosive: /b/, /t/, /d/, /k/, /g/, /kp/, /gb/.

Nasal: /m/, /n/, /ji/, /g/, /gw/.

Trill: /r/

Fricatives: /f/, /s/, /z/, /ƒ/, /y/, /gw/, /fi/.

Affricate: /d3/

Approximant: /j/, /w/.

Lateral: /l/

Igbo vowels: /i/, /i/, /u/, /u/, /o/, /d/, /e/, /e/, /a/.

Igbo consonants:

Plosives: /p/, /b/, /t/, /d/, /k/, /g/, /kp/, /gb/, /kw/, /gw/.

Nasals: /m/, /n/, /ji/, /g/, /gw/.

Affricate: /ij/, /cfe/.

Fricative: /s/ /z/ /f/ /ƒ/ (/3/) /y/ /fi/.

Approximant: /[ /, /j/, /w/.

Lateral: /l/

Esan (adapted from Ikoyo-Eweto 2017)

Vowels: /a/, /a/ /e/, /e/, / e/, /i/, /K/, /o/, /o/, /o/, /u/, / ü/.

Consonants: /p/, /b/, /t/, /d/, /k/, /g/, /kp/, /gb/, /ty/, /m/, /n/, /B/, /f/, /v/, /s/, /z/, /3/, /x/, /y/, /tt/, /&,/, /m/, /rr/, /n/, /p/, /l/, /r/, /j/, /w/.

The phonemic inventory of Lukumi (also known as Anagó) as documented by Olmsted (1953) appears below.

Lukumi/Anagó vowels: /i/, /e/, /e/, /a/, /o/, /u/.

Lukumi/Anagó consonants: /b/, /gb/, /kp/, /d/, /t/, /j/, / t/, /g/, /k/, /f/, /s/, /r/, /l/, /m/, /n/, /p/, /rj/.

Spanish phonemes:

Spanish has 24 phonemes, 5 vowels and 19 consonants

Spanish vowels: /i/, /u/, /e/, /o/, /a/.

Consonants:

Plosives: /p/, /b/, /t/, /d/, /k/, /g/.

Nasals: /m/, /n/, /p/.

Affricate: /tt/

Fricatives: /f/, /e/, /s/, /r/, /x/.

Lateral: /l/,/A/.

Flap: /r/

Trill: /r/

Yoruba vowels: /i/, /i/, /u/, /u/, /e/, /o/, /e/, /e/, /o/, /o/, /a/.

Yoruba consonants:

Plosive: /b/, /t/, /d/, /j/, /k/, /g/, /kp/, /gb/. Nasal: /m/, /n/, /n/.

Trill: /r/

Fricative: /f/, /s/, /$/, /b/.

Affricate: /d3/

Approximant: /j/, /w/.

Lateral: /l/

Phonemic and lexical similarities in Lukumi, Olukumi and Yoruba

Lukumi, Olukumi and Yoruba have many linguistic items that are similar. Olukumi, however, has some phonemes that are non-existent in Yoruba; for instance the /z/ phoneme was borrowed from Igbo (Arokoyo 2012). However, its affinity with Yoruba is evident from the manifestation of high nasality Okolo-Obi (2014). Similarly, Lukumi, which has been very much influenced by Spanish, lost a lot of Yoruba features, particularly grammatical features, prosodic features and some phonemes which have been replaced with Spanish ones (Anabaraonye 2018).

Methods

Oral interview was a major method of data collection in this study. Also, from the Internet, some Cuban Lukumi wordlists were obtained (cf. references for websites) since there is no Lukumi speaker in the immediate environment of the study. Some of the words (kinship terms, numbers, body parts, pronouns, and other basic terms) align with those in the list of Swadesh (1952) while others (common in Yoruba culture) are concepts that feature in Yoruba traditional religion since Lukumi is mainly used for religious purposes. To get their Olukumi equivalents, the words were used to get information through an oral interview with an adult male Olukumi native speaker (Mr. Ogwu) in Ukwunzu, an Olukumi speaking community. A Yoruba native speaker, (Mr. Komolafe) also gave the Yoruba versions. Subsequently, the phonetic features of the words were determined with a view to reflecting them in the dictionary in a way to show their similarities or dissimilarities.

In compiling the entries of the language, the method of Mashamaite (2001) is adopted with modification. This method, the hub and spoke model, links the lexical items of the spoke (source) languages to a common hub (target language). Our focus is to give dictionary users basic information of the entries, including their phonetic forms, while maximising space.

Presentation and compilation of the lemmas

Generally, dictionary entries are arranged in alphabetical order of headwords, which are usually in bold typeface. Dictionary articles generally present the following information types:

i. Pronunciation information

ii. Spelling information

iii. Part of speech information

iv. Figures of speech information

v. Meaning demarcation information

vi. Cross-reference information and

vii. Information on construction

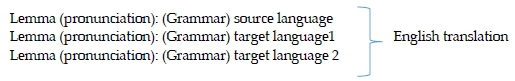

In the proposed dictionary, Lukumi, Olukumi and Yoruba lemmas are transcribed phonemically to provide both pronunciation and spelling information to the user. In glossing the Olukumi, Lukumi and Yoruba lexical entries in a multilingual dictionary, some user's guide information are highlighted below. Also, the glossed lexical entries of the three languages are presented in an alphabetical order. Check interline sections.

Furthermore, following the international ISO code format for languages, the ISO code OLU, LUK and YOR are used to specify the three languages. The grammatical category is written in abbreviation to the first letter of the word class. Example: noun = n. For the brief illustration of the proposed multilingual dictionary, only the main grammatical category is used. n.: Check the interline sections.

In our demonstration, because the Nigerian languages' equivalents are complete and near cognates, repetition of words is avoided unless where there is difference in tone. The pronunciation information provided also helps in meaning demarcation. If a headword used in a definition is polysemous, the exact meaning of what is intended is clearly stated in the English description. There are also word and space economy. Check the interline sections.

We downloaded Lukumi words from the internet (website addresses can be seen in the references). The words consist of religious and basic words.

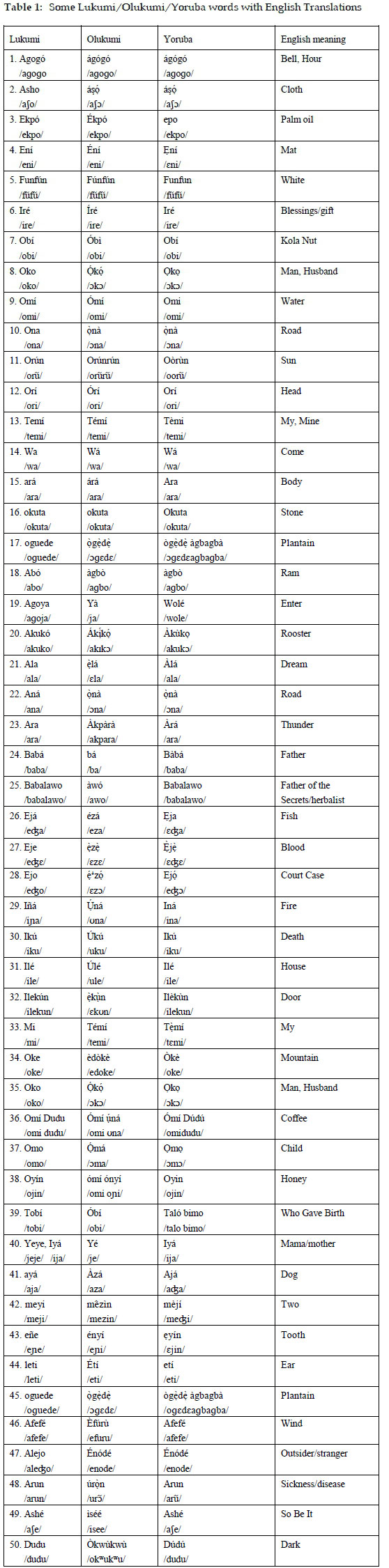

Some of the words and their equivalents in Olukumi and Yoruba are given in Table 1 below. However, twenty-two (22) words are used to exemplify (typify) what the proposed dictionary should look like.

It can be seen that from 1 to 45, the lexical items are highly similar in the three languages. Yoruba and Lukumi maintained similarity for the lexical items from 46 to 50, but Olukumi displayed some dissimilarities in the phonemes of the lexical items involved.

Sample compilation of the lemmas

Although Nesi (2009) points out that the electronic dictionary is better than the paper one, it is pertinent to point out that concerning the languages and the circumstance under study, paper dictionary is more accessible and better to comprehend than the electronic one. Hence compilation is discussed here with the paper dictionary in mind.

Nesi (1999: 56) emphasizes the fact that many useful features such as indexes and cross-reference symbols have been added in the paper-dictionaries to assist the user in multiword searches. However, Nesi (1999: 55-56) concludes that the more information the paper-based dictionary contains, the harder (and more time-consuming) it will become for learner users to find exactly what they need to know. This is due to the presence of so much unwanted information. Meijs (1992: 152) as reported by Nesi (1999: 65) predicts "the imminent demise of the dictionary as a book".

As already pointed out in the previous sections, most dictionaries on indigenous Nigerian languages lack some basic features which can enhance their usage and facilitate learning by second language learners. Igbo dictionary by Williamson (1972) which has English as the target language and Igbo as the source language is a mono-directional dictionary serving the need of English speakers. A more recent work Igbo Adi, (Mbah et al. 2013) is bidirectional; part A takes care of Igbo speakers while Part B benefits English speakers. Both works, including others not mentioned, do not feature pronunciation as proposed in the present study.

This study proposes a multilingual dictionary for the three languages under study. Most multilingual dictionaries, particularly online ones, are compiled in a tabular format. This study proposes a completely different approach from these. Here, we propose a method where there is only one part and each of the three languages have equal representation of the information provided in that part. In other words, speakers and learners of all the languages in the dictionary benefit from that one holistic part.

In typifying the compilation of the proposed dictionary, we partly adopt the model of Mashamaite (2001); that is, the hub and spoke model, a model he proposes for compiling bilingual dictionaries between African languages. He shows that it has the advantage of being economical to use. However, the adoption of the method is with modification since the phonetic features, which he did not consider, are included here. Hence the major parameters of the model will be retained while we incorporate other features that emphasize both meaning and pronunciation. Mashamaite's model seems to emphasize meaning and grammar to the detriment of pronunciation (phonetic form). This is a gap we hope will be filled in the proposed dictionary. Consider, below, an excerpt from Mashamaite (2001: 118).

Source language: Northern Sotho - thelebisene

Target languages: English - television

Lexical unit: same/different

Form unit: same/different

Phonetic form: same/different

Conceptual equivalence: complete

Since the above format will not be good for our dictionary, the following format will be adopted in the proposed dictionary:

As usual, the entries are entered alphabetically but presented diagrammatically for clarity and space economy. The form unit, phonetic form (transcription), the lexical unit and grammatical category of the lemmas are displayed with economy of space. The English translations of the lemmas are placed after the braces, an indication that English language is not a focus in the dictionary. Generally, the reversibility principle is applied even though the dictionary will have only one section. Every information that would have been obtained from a second or third section (since three languages are involved) is evident in the sole section. The reversibility principle, which is important for the full understanding of the lemmas from one language to another, is evidently displayed since the translations of the lemmas in the three languages are included in the sole section. Also, the phonemic inventories of the three languages should be displayed in the preliminary pages. The display of the entries in the proposed dictionary is typified below in Table 2.

The presentation of this dictionary is to be likened to that of a dictionary of synonyms where synonyms of lexemes are supplied without the explanation of what the entry words are. In the main dictionary, more words, than the number shown above, will be documented.

This simple, space compacted easy to read method is hereby proposed for multilingual dictionaries, especially paper multilingual dictionaries. Some authors of African languages opine that tone should not be marked since they make works to be cumbersome. However, the format adopted in indicating the pronunciation of lemmas, alongside other features in the proposed dictionary, has shown that it is not cumbersome; rather, making available this information will facilitate the learning of the languages by second language learners particularly.

Furthermore, the degree of reflection of the reversibility principle in the lemmas shown in this study evidently displays the similarities shared by the three languages in their phonetic, lexical and form units. That is, most of their lexical items (lemmas) are translation equivalents in the three languages. De Schryver (2006) citing a scholar like Gouws (1996) shows that the reversibility principle is the condition where the lemmas or translation equivalents in a bilingual dictionary are translation equivalents in the two sections of the dictionary. In a bilingual dictionary, there are usually two sections, the first section dealing with translations from language A to B while the second section deals with translations from language B to A. The reversibility principle demands that both sections should have translation equivalents. For a multilingual dictionary, there may not be such sections; rather (as in the case of this proposed dictionary) lemmas of the languages for a particular entry are given together. However, the reversibility principle is taken into consideration if the lemmas of the languages concerned in the dictionary have equivalent translations (as is the case in the twenty-two sample entries shown above). De Schry-ver (2006) points out that if words in one language do not map to words in another language, some complexity and especially ingenuity are applied to present their equivalents so as to maintain the reversibility principle.

According to Svensén (1993) translation equivalence entails expressions in the source language having counterparts which are semantically as near as possible in the target language. The high degree of similarities between the three languages under study is seen in the fact that most of their meaning equivalents (lexical units) coincide with their word equivalents (form units). That is, they are linguistically equivalent; in other words, there is a high degree of homogeneity (word for word translation) between the source language, Lukumi and the target languages, Olukumi and Yoruba. This is easily noticeable in the three headwords (one headword for each language) presented for the lemmas. Any observed differences between them could be as a result of varying degrees of influence from the languages and cultural practices (contexts) of their immediate environments.

Discussion

From the entries in this work, it can be observed that Lukumi has retained more Yoruba phonetic features than Olukumi. The implication here (though some words are mainly based on religion) could be that the two varieties, particularly Olukumi, are diverging from the parent language, Yoruba. The divergence of Olukumi could be as a result of influence from the languages, particularly Igbo, surrounding it. There are fears that it could face extinction because of this influence. There is therefore need to intensify its study and documentation so as to foster its maintenance. Hence the proposal for a multilingual dictionary, (as initiated in this study covering Lukumi, Olukumi and Yoruba, with translations in English) should be adopted.

However, there are similarities in the phonemes of Lukumi and Olukumi. Interestingly, their lexical similarity appears to align with their phonemic similarity. They have mainly phonetic spelling; that is, most of their phonemes bear the same symbols as the letters of their alphabet. This is because according to Coulmas (1989) alphabets for African languages were influenced by the work of phoneticians at the International Institute of African Languages and Cultures in London. This institute established the Practical Orthography of African Languages; which was influenced by the IPA, thus being based on the principle of one letter corresponding to one sound. In spite of their phonetic spelling, transcribing the lemmas to show their pronunciation is important since some of the letters do not have one-to-one relationship with the phonemes they represent.

Implications of including pronunciation in a multilingual dictionary

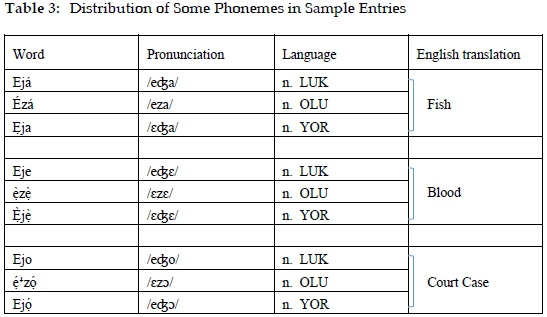

Showing the pronunciation of entries helps in revealing the phonetic similarities and dissimilarities of lexical items in a multilingual dictionary. This in turn, aids in revealing the relationship between the language varieties. Also, it reveals their etymology. This can be seen in the distribution of some phonemes in the sample entries shown above. Consider the ones shown below in Table 3:

From the lemmas above, it can easily be deduced that the phoneme /z/ is used in place of /d3/ in Olukumi. Also, that Lukumi and Yoruba use of the same phoneme not only shows the etymology of Lukumi and Olukumi but also portrays the fact that Lukumi has retained more Yoruba features than Olukumi.

Only the transcription of their pronunciation can explicitly show these facts, making it easy for speakers as well as second language learners to use the dictionary.

Brandon (1993) explains that phonetic transcription gives uniformity in pronunciation and spelling. This is because the language users are not in doubt as to how to pronounce the words. According to Carroll (1992) phonological representations serve as bases for cognate pairing, which is a major step in compiling a multilingual dictionary. Thus phonetic transcriptions aid in ascertaining the words that have equivalents in the languages represented in the dictionary.

Since the varieties in the proposed dictionary are mainly spoken by people on different continents, it is necessary to have sufficient information in it so as to avoid confusing users. Hence sufficient information, including pronunciation, should be made available in the dictionary. The dictionary can be posted online even though its design is for paper dictionary. Lew (2011) opines that indicating pronunciation in online dictionaries is necessary.

Mashamaite (2001) opines that bilingual dictionaries may serve different purposes depending more on the communicative needs of the dictionary users than on the amount of information supplied by the compiler.

Bilingual dictionaries also aid in translation; here displaying the lexical features of the languages helps a lot. Thus this work, having shown the phonetic and lexical features of the varieties under study, has provided enough information to make the proposed multilingual dictionary functional in language use and study. This is because it is multi-directional; speakers of these languages can use it for various language purposes. According to Rojas (2012) there is a need to have multilingual dictionaries for minority languages. He emphasizes that it is not only international languages that should have multilingual dictionaries. The present study is a step towards achieving this for Lukumi, Olukumi and Yoruba. Hence the significance of this study in the conservation of Olukumi and Lukumi (which are endangered) cannot be over emphasised.

Conclusion

Since the major target of language study is speech, this paper has taken time to show how pronunciation can be displayed in a multilingual dictionary being proposed for Lukumi, Olukumi and Yoruba. The aim of this paper is to show the extent to which Olukumi and Lukumi are mutually intelligible (judging from the phonetic and semantic similarities of their lexical items). The paper shows how a multilingual dictionary can display these similarities and aid intelligibility and communication among the speakers/learners of the languages. We conclude that this can be done through the indication of the phonetic/phonemic transcription of entries of each language.

We show that through the indication of pronunciation of the entries, the phonemic similarities and dissimilarities between the languages can be displayed. For instance, the various phonemes that are available in the languages and those only available in one or two of them, are easily identifiable through the indication of pronunciation. A good example is the phoneme, /gb/ which exists in Olukumi and Yoruba but does not feature in Lukumi. In the latter, it is replaced with the phoneme, /b/. The word lists used for the study reveal that Lukumi has retained more Yoruba features than Olukumi. The latter is like a linguistic island hedged round by Igbo and Esan; it has assimilated so many borrowed words that most of its Yoruba features are fast eroding.

However, Lukumi and Olukumi share many phonetic features particularly in the areas of syllabic reduplication and vowel nasality. Nonetheless, whereas Olukumi manifests tone, Lukumi uses accents as obtains in Spanish, its language of influence. Moreover, certain phonemes existent in Olukumi (which are of Igbo origin) do not exist in Lukumi and Yoruba. Without documenting and studying these languages, most of their features will be lost to the surrounding languages. Worse still, their imminent death is inevitable. A study of this kind is therefore pertinent.

References

Dictionaries and Wordlists

Blench, R. (Ed.). 2013 Dictionary of Onichà Igbo. Cambridge: Roger Blench Kay Williamson Educational Foundation. [ Links ]

Crowther, S.A. 1865. Vocabulary and Dictionary of the Yoruba Language. London: W.M. Watts. [ Links ]

Lucumi Dictionaries: https://www.orishaimage.com/blog/dictionaries. Downloaded 30/01/2018.

Lucumi Vocabulary: http://www.orishanet.org/vocab.html. Downloaded 30/01/2018.

Ogwu, E. 2017. Headmaster of a primary school in Ukwunzu, (oral interview with researcher), 31st March 2017.

Williamson, K. (Ed.). 1972. Igbo-English Dictionary. Benin: Ethiope Publishing Corporation. [ Links ]

Yai, Olabiyi Babalola. 1996. Yoruba-English, English-Yoruba Concise Dictionary. New York: Hippocrene Books. [ Links ]

Other references

Anabaraonye, K. 2018. A Closer Look into Lucumi and Yoruba in Comparison. Havana Live, 18 March 2018. https://havana-live.com/an-in-depth-look-into-lucumi-and-yoruba-in-comparison/.

Arokoyo, B.E. 2012. A Comparative Phonology of the Olükümi, Igala, Owe and Yoruba Languages. Paper presented at the Conference on Towards Proto-Niger Congo: Comparison and Reconstruction, Paris 18-21 September 2012.

Brandon, G. 1993. Santeria from Africa to the New World: The Dead Sell Memories. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

Carroll, S. 1992. On Cognates. Second Language Research 8(2): 93-119. [ Links ]

Concordia, M.J. 2012. The Anagó Language of Cuba. Unpublished M.A. Thesis. Miami: Florida International University. [ Links ]

Coulmas, F. 1989. The Writing Systems of the World. Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

De Schryver, Gilles-Maurice. 2006. Compiling Modern Bilingual Dictionaries for Bantu Languages: Case Studies for Northern Sotho and Zulu. Corino, E. et al. 2006. Atti del XII Congresso Internazionale di Lessicografia, Torino, 6-9 settembre 2006 / Proceedings XII Euralex International Congress, Torino, Italia, September 6th-9th, 2006: 515-525. Alessandria: Edizioni dell'Orso. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. 1996. Idioms and Collocations in Bilingual Dictionaries and Their Afrikaans Translation Equivalents. Lexicographica 12: 54-88. [ Links ]

Ikoyo-Eweto, E.O. 2017. Phonetic Differences between Esan and Selected Edoid Languages. Journal of Linguistics, Language and Culture 4(1): 65-85. [ Links ]

Lew, R. 2011. Online Dictionaries of English. Fuertes-Olivera, P.A. and H. Bergenholtz (Eds.) 2011. e-lexicography: The Internet, Digital Initiatives and Lexicography: 230-250. London/New York: Continuum. [ Links ]

Mafela, M.J. 2005. Meaning Discrimination in Bilingual Venda Dictionaries. Lexikos 15: 276-285. [ Links ]

Marello, C. and M. Tomatis. 2008. Macro- and Microstructure Experiments in Minor Bilingual Dictionaries of XIX and XX Century. Bernal, E. and J. DeCesaris (Eds.). 2008. Proceedings of the XIII EURALEX International Congress, Barcelona, 15-19 July 2008: 1155-1164. Barcelona: Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Institut Universitari de Lingüística Aplicada. [ Links ]

Mashamaite, K.J. 2001. The Compilation of Bilingual Dictionaries between African Languages in South Africa: The Case of Northern Sotho and Tshivenda. Lexikos 11: 112-121. [ Links ]

Mason, J. 1997. Ogun: Builder of the Lukumi's House. Barnes, S.T. (Ed.). 1997. Africa's Ogun: 353-368. Bloomington/Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

Mbah, B.M., E.E. Mbah, E.S. Ikeokwu, C.O. Okeke, I.M. Nweze, C.N. Ugwuona, C.M. Akaeze, J.O. Onu, E.A. Eze, G.A. Prezi and B.C. Odii. 2013. Igbo Adi. Nsukka: University of Nigeria Press. Michelena, M. and R. Marrero. 2010. Diccionario de Términos Yoruba. Pronunciación, sinonimias y uso práctico del idioma lucumíde la nación Yoruba. Mexico/Miami/Buenos Aires: Prana.

Nesi, H. 1999. The Specification of Dictionary Reference Skills in Higher Education. Hartmann, R.R.K. (Ed.). 1999. Dictionaries in Language Learning: Recommendations, National Reports and Thematic Reports from the TNP Sub-Project 9: Dictionaries: 53-67. Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin. [ Links ]

Nesi, H. 2009. Dictionaries in Electronic Form. Cowie, A.P. (Ed.). 2009. The Oxford History of English Lexicography: 458-478. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Okolo-Obi, B. 2014. Aspects of Olukumi Phonology. M.A. Project Report. Nsukka: University of Nigeria. [ Links ]

Olmsted, D.L. 1953. Comparative Notes on Yoruba and Lucumí. Journal of the Linguistic Society of America 29(2): 157-163. [ Links ]

Onwueme, I.C. 2015. Questions Not Being Asked: Topical Philosophical Critiques in Prose, Proverbs, and Poems. Bloomington: AuthorHouse. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, D.J. and Gilles-Maurice de Schryver. 2009. Corpus Applications for the African Languages, with Special Reference to Research, Teaching, Learning and Software. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 19(1-2): 111-131. [ Links ]

Rojas, D. 2012. Multilingual Dictionary for Minority Languages. https://launchpad.net/milandic. Accessed 04/06/2018.

Rosenhouse, J. 2018. Modern Arabic Dictionaries: Phonetic Aspects and Implications Zeitschrift für Arabische Linguistik 67: 71-89. DOI: 10.13173/zeitarabling.67.0071.

Schepens, J., T. Dijkstra, F. Grootjen and W.J.B. van Heuven. 2013. Cross-language Distributions of High Frequency and Phonetically Similar Cognates. PLoS One 8(5): e63006. [ Links ]

Shoba, F.M. 2001. The Representation of Phonetic-Phonological Information in Nguni Dictionaries. M.A. Thesis. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University. [ Links ]

Sobkowiak, W. 2003. Pronunciation in Macmillan English Dictionary for Advanced Learners on CD-ROM. International Journal of Lexicography 16(4): 423-441. [ Links ]

Svensén, Bo. 1993. Practical Lexicography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Swadesh, M. 1952. Lexico-statistic Dating of Prehistoric Ethnic Contacts: With Special Reference to North American Indians and Eskimos. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 96(4): 452-463. [ Links ]

Van Keymeulen, J. 2003. Compiling a Dictionary of an Unwritten Language: A Non-corpus-based Approach. Lexikos 13: 183-205. [ Links ]

Vishnevskaya, G.M. 2013. Language Globalization through the Prism of Lexicography. Karpova, O.M. and F.I. Kartashkova (Eds.). 2013. Multi-Disciplinary Lexicography: Traditions and Challenges of the XXIst century: 2-10. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [ Links ]