Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Lexikos

versão On-line ISSN 2224-0039

versão impressa ISSN 1684-4904

Lexikos vol.30 Stellenbosch 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.5788/30-1-1580

ARTICLES

Sethantso sa Sesotho and Sesuto-English Dictionary: A Comparative Analysis of their Designs and Entries*

Sethantso sa Sesotho en Sesuto-English Dictionary: 'n Vergelykende analise van die ontwerp en inskrywings

T.L. Motjope-MokhaliI; I.M. KoschII; Munzhedzi James MafelaIII

IDepartment of African Languages and Literature, University of eSwatini, eSwatini (Corresponding Author, tlmotjope@gmail.com)

IIDepartment of African Languages, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa (ikosch7@gmail.com)

IIIDepartment of African Languages, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa (munzh.mafela@gmail.com)

ABSTRACT

This article seeks to establish the relationship and extent of similarity between two Sesotho dictionaries, published in the 1800s and 2005 respectively. The two dictionaries under discussion are the Sesuto-English Dictionary by Mabille and Dieterlen and Sethantso sa Sesotho by Hlalele. The former dictionary, like most dictionaries of other African languages pioneered by the missionaries, is bilingual. The latter dictionary is the first monolingual dictionary for Sesotho and it was compiled by a mother tongue-speaker of the language. The closeness of the content of the two dictionaries is established by applying the user-perspective approach as the framework of analysis. Through an analysis of the designs and entries in the two dictionaries, the study discovers similarities and differences in terms of the use of non-standard symbols and atypical sound patterning, illustrative phrases/sentences and obsolete or archaic words. Given the amount of obsolete items in Sethantso sa Sesotho, one of the recommendations emanating from this study is that Sethantso sa Sesotho be revised or that a new monolingual dictionary be produced which will include more modern words that will meet the needs of contemporary users.

Keywords: bilingual dictionary, monolingual dictionary, lexical items, comparison, theory of adaptation, sesotho dictionaries, similarities, differences, obsolete and new words

OPSOMMING

Hierdie artikel poog om die verhouding en omvang van ooreenkoms tussen twee Sesotho woordeboeke, wat onderskeidelik in die 1800s en 2005 gepubliseer is, te bepaal. Die twee woordeboeke onder bespreking is die Sesuto- English Dictionary deur Mabille en Dieterlen en Sethantso sa Sesotho deur Hlalele. Eersgenoemde woordeboek is tweetalig, soos die meeste woordeboeke van ander Afrikatale wat die pionierswerk van sendelinge was. Laasgenoemde woordeboek is die eerste eentalige woordeboek vir Sesotho en is saamgestel deur 'n moedertaalspreker van die taal. Die ooreenkoms in die inhoud van die twee woordeboeke word bepaal deur die toepassing van die gebruikersperspektiefbenadering as raamwerk van ontleding. Deur middel van 'n analise van die ontwerp en inskrywings in die twee woor-deboeke stel die studie ooreenkomste en verskille vas ten opsigte van die gebruik van nie-stan-daard simbole en atipiese klankkombinasies, verduidelikende frases/sinne en die gebruik van ouderwetse woorde. In die lig van die aantal ouderwetse inskrywings in albei woordeboeke, is een van die aanbevelings van hierdie studie dat Sethantso sa Sesotho hersien moet word of dat 'n nuwe eentalige woordeboek opgestel moet word wat meer hedendaagse woorde insluit wat aan die behoeftes van huidige gebruikers sal voorsien.

Sleutelwoorde: tweetalige woordeboek, eentalige woordeboek, leksikale items, vergelyking, teorie van aanpassing, sesotho woordeboeke, oor-eenkomste, verskille, ouderwetse en nuwe woorde

1. Background information

Sesotho is a language spoken in Lesotho and in the Republic of South Africa (RSA). However, there is a Lesotho orthography and a South African orthography that is used respectively by the Basotho residing in these two countries. Although the language in these countries is the same, each country retains its identity through its orthography. As a result, most prescribed and recommended Sesotho texts used in Lesotho schools are written in the Lesotho orthography. This study focuses only on the dictionaries written in Lesotho orthography and the word 'Sesotho' refers to the language used strictly in Lesotho.

Sesotho is one of the first Southern African languages to have documents penned down in writing compared to the other indigenous languages. Sesotho's strong literary traditions are seen in works such as Thomas Mofolo's novels Moeti oa Bochabela (The Traveller to the East) (1907), and Chaka (1925), as well as Mangoaela's Lithoko tsa Marena a Basotho (A collection of praises of Basotho chiefs) (1921) (http://www.kwintessential.co.uk/lang). Although Lesotho orthography is older than the South African one, the development of dictionaries in Lesotho has been very slow.

The Sesotho lexicography was pioneered by the missionaries just like the lexicography of other African languages. Literature reveals that the dictionaries of African languages were particularly meant for second-language speakers and were utilised as instrumental tools for the acquisition of vocabulary. Scholars such as Awak (1990), Busane (1990), Gouws (2005), Makoni and Mashiri (2007), Nkomo (2008), Prinsloo (2013) and Otlogetswe (2013) argue that the missionaries' priority was not to develop African languages but rather to create tools enabling them to fulfil their goals in Africa. Awak (1990: 17) states that the early vocabularies were not intended to be used by Africans but were aimed at guiding the missionaries and other Europeans who wanted to learn African languages for evangelisation purposes. Many dictionaries produced around the late nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries were therefore bilingual.

In Sesotho, like in other African languages, such as isiXhosa, the dictionaries compiled by the missionaries are still used as reliable and accessible sources (Mtuze 1992). However, these dictionaries contain several words that have become obsolete and their vocabulary is limited because many words which are currently used do not occur in such dictionaries. Africans have recently begun engaging in producing dictionaries that are geared towards the needs of their fellow Africans. It is assumed that (monolingual) dictionaries produced by mother-tongue speakers are expected to meet the needs of the mother-tongue speakers. Dictionary production has recently developed considerably in African communities, however, Sesotho dictionaries have lagged behind. The rate at which Sesotho dictionaries are produced is very slow despite the fact that Sesotho was one of the first languages to have written documents. The first Sesotho monolingual dictionary was published in 2005. When one looks at the gap between the prominent dictionary published by the missionaries in the 1800s, the Sesuto-English Vocabulary (1878), later revised and titled the Sesuto-English Dictionary, which was last edited in 1937 (i.e. the last edition of the old Sesuto-English Dictionary), and a new dictionary, the Sethantso sa Sesotho (2005), one learns that several changes have occurred in the language. The changes were motivated by various factors such as time, technological advances, language changes, and the borrowing and creation of new words (Rundell 2008). It is therefore necessary for Basotho scholars to come together and compile Sesotho dictionaries as a group and not as individuals. The current study intends to establish the nature of the divergence or overlap between Sethantso sa Sesotho and Sesuto-English Dictionary by analysing their designs and entries. The research seeks to determine, amongst others, if the new Sesotho monolingual dictionary has moved beyond the older one by incorporating the new words that have entered Sesotho and to establish if the dictionary meets the needs of the contemporary users.

2. Dictionaries under scrutiny

This section provides the history of the two dictionaries under scrutiny: Sesuto-English Dictionary and Sethantso sa Sesotho.

2.1 Sesotho-English Dictionary

The first Sesotho dictionary had its beginning on a sailing ship from England to South Africa around 1859. Paroz (1950) records that Adolph Mabille started the Sesotho vocabulary list during that long journey to South Africa with the assistance of his wife born at Thaba-Bosiu as the daughter of Eugene Casalis. Mabille began the Sesotho vocabulary list initially for his personal use but on his arrival at Morija, he established a printing press and published his first Sesotho dictionary in 1878 under the title Sesuto-English Vocabulary. Ambrose (2006: 20) argues that the dictionary was published in 1876 and not 1878. He stresses that even though most sources give the date as 1878, it looks like they confuse this year with Mabille's Helps for to learn the Sesuto language [sic], which was published in 1878. Mabille edited the dictionary in 1893, and after his death in 1894, Dieterlen took over. Paroz (1950) highlights that the Dieterlens (Mrs. Dieterlen included) added the names of plants to the vocabulary and were responsible for the third edition in 1904, the fourth edition in 1911 (when Dieterlen changed the title to the Sesuto-English Dictionary) and the fifth edition in 1917. Since then, the dictionary has had no additions to the word list. In 1937, the words in the addendum of the fifth edition were fused with the main text in the sixth edition of the dictionary. According to Ambrose (2006: 4-5):

The 7th, 8th, and 9th editions were effectively reprints of the 6th edition and should have been indicated as such by the publishers (the Morija Sesuto Book Depot) and not as new editions.

Ambrose further posits that there was, however, a true seventh edition of the dictionary by a new missionary called R.A. Paroz who observed that Sesotho is an inflected language in which both prefixes and suffixes are attached to a stem. Consequently, he reclassified the words according to their stems, i.e. a word such as mpho (gift) is not found under the letter /m/ but rather under /f/, which starts the stem -fa (give). This means that to find the word mpho, one has to look under the stem -fa. Paroz also added some new words and changed the title of the dictionary to Southern-Sotho-English Dictionary. The revised and reclassified edition is what Ambrose calls "the true seventh edition" (2006: 5), which was published in 1950 using the Lesotho orthography and in 1961 using the Republic of South Africa's orthography (8th edition). According to Paroz (1950), the main difference between Mabille and Dieterlen's Sesuto-English Dictionary and Southern-Sotho-English Dictionary lies in the classification of lexical entries. Whereas the first six editions of the dictionary (up to 1937) used the word approach whereby entries could be looked up under the first letter of the word (mostly in the singular form), the seventh and later editions (from 1950 onwards) followed the stem approach, whereby words carrying prefixes were classified according to the first letter of the stem as illustrated above with the entry mpho. The current study looks at the sixth edition (1937) but the reprint (2000) of that edition is utilised. The dictionary includes words from different subject fields such as initiation, poetry, dance, food, history and plants to mention a few.

2.2 Sethantso sa Sesotho

The Sethantso sa Sesotho was compiled by Batho Hlalele (a former Catholic priest) in 2005. According to Ambrose (2006), the author spent over 40 years collecting and recording in writing the meanings of words in Sesotho. Sethantso sa Sesotho is a general dictionary which consists of words from various subject fields such as initiation, poetry, dance, food, history, proverbs and idioms. The dictionary uses phonemic sorting for the arrangement of its words while following the normal alphabetical order of English that is, from the letter "a" to "u". It offers detailed information regarding word categories, for example, in the case of nouns, it presents the class number to which the noun belongs, its plural prefix and information on the origin of the noun in question where applicable. In the case of verbs, various verbal suffixes are provided to indicate different extensions that apply to them. Past tense forms are also provided. In addition, decimal points are used to show places of junction between morphemes that make up each word. Examples of word usage are also offered to indicate how certain words can be used in context. Furthermore, lexicographic labels are provided to give the user an idea regarding which field or subject a particular word belongs to. These features make it unique because it differs from others which are restricted in nature such as Matsela's Sehlalosi: Sesotho Cultural Dictionary of 1994 and Pitso's 1997 thesaurus called Khetsi ea Sesotho.

According to the information provided in the back matter of Hlalele's dictionary (2005), Sethantso sa Sesotho is the first Sesotho monolingual dictionary of its kind produced by a mother-tongue speaker. It encourages users to speak and write "Sesotho sa 'Mankhonthe" which can be translated as 'the real Sesotho' or 'the original Sesotho'. The dictionary is used as a reference book by students at secondary and high school level. It is also useful to student teachers, teachers, lecturers and university students who are doing African languages and literature and libraries all over the Southern African Development Community (SADC) countries. Sethantso sa Sesotho has not yet been revised since its publication (according to the researcher's knowledge).

3. Comparing dictionaries

Comparative studies between dictionaries are made for various reasons including the evaluation of dictionary use while reading and writing, reasons for dictionary consultation, knowledge of words and assessment of the users' needs which determine the dictionary plan. For instance, scholars such as Prinsloo (2005), Laufer (2000), Nesi (2000) and Lomicka (1998) deal with the effectiveness of paper dictionaries versus electronic dictionaries during a reading comprehension experiment. Shiqi (2003) analyses dictionaries that were produced over a period of time while Rundell (2008), Hatherall (1986) and El-Badry (1986) survey dictionaries which derive from the same source to identify the changes that occurred over time. This study follows those carried out by scholars such as Shiqi (2003), Rundell (2008), Hatherall (1986) and El-Badry (1986).

Shiqi (2003) analyses ancient and modern Chinese monolingual dictionaries from the ninth century BC to 2002. The study looks at the development of these dictionaries in terms of their classification, arrangement of words, number of entries, how words are explained, and types of words included, such as names of implements, geographical features, names of plants and animals as well as kinship terms. The study reveals that ancient dictionaries were used as a basis upon which the modern dictionaries are compiled. The ancient dictionaries are smaller and were created by individuals while the modern ones are larger and produced by groups of scholars. Words and characters are mostly arranged according to the radical order (that is, characters of the same radical are grouped together) both in the ancient and modern dictionaries. Explanation of words is brief in the ancient dictionaries compared to the modern ones and the number of entries increased. Both the ancient and modern dictionaries contain common and specialised terms. This means that the modern ones are improved and add on to what was already presented. For instance, the modern dictionaries cover scientific and technical terms from more than 120 disciplines.

Rundell (2008) studied the recent developments in English monolingual dictionaries. The study deals with the extent to which the advanced English Monolingual Learner's Dictionary (MLD) has moved on from Hornby's Idiomatic and Syntactic English Dictionary (ISED) of 1942. The study establishes that the dictionary now has broadened to encompass such areas as pragmatics, cultural allusion, encyclopaedic information and guidance on every aspect of grammar and usage. Again, monolingual learner's dictionaries moved away from the model of the native-speaker's 'dictionary of record' towards a more 'utilitarian' lexicography, in which the needs of the user take precedence over all other factors.

Hatherall (1986) compares the Duden Rechtschreibung 's 1985 edition by Leipzig and the 1986 edition by Mannheim and reveals that the editions differed significantly from each other mainly because they stemmed from different publishers and different editorial boards.

El-Badry (1986) surveys seven Arabic-English and eight English-Arabic dictionaries in order to trace the development of the bilingual lexicography of these two languages in terms of the explicit or implicit plans of their respective authors and the sources they draw on. The study found that Arabic-English dictionaries used source material from several contemporary bilingual dictionaries and an Arabic monolingual dictionary. The English-Arabic dictionary utilised bilingual dictionaries of Arabic and French plus other linguistic and literary works of classical writers.

Studies similar to those undertaken by Shiqi, Rundell, Hatherall and El-Badry have not yet been done in Sesotho dictionaries. This study therefore attempts to bridge that gap by establishing the relationship between the Sesuto-English Dictionary and the Sethantso sa Sesotho to determine what needs to be done to improve dictionaries in Sesotho.

4. Comparison of the Sesuto-English Dictionary and the Sethantso sa Sesotho

To establish whether or not there is a relationship between the Sesuto-English Dictionary and the Sethantso sa Sesotho, the designs and entries of the two dictionaries were compared. Dictionary design involves proper planning of the structure of the dictionary in question. According to Gouws and Prinsloo (2005: 13-16), the plan is concerned with the direct lexicographic issues and focuses on aspects such as the lexicographic functions, dictionary typology, target user, structure of the dictionary, and lexicographic presentation.

Lexical entry 'refers to the entry in a dictionary of information about a word' (http://www.thefreedictionary.com). The study therefore compared all lexical entries, also known as headwords, contained in the Sethantso sa Sesotho with those that are presented in Sesuto-English Dictionary, that is, all the items shared by the two dictionaries were identified as well as those that are peculiar to Sethantso sa Sesotho only. This means that the study focuses only on the lexical items that are included in the Sethantso sa Sesotho while those that appear only in the Sesuto-English Dictionary are left out. This is done to establish how close or far the two dictionaries are and to find out if the new dictionary is better than its predecessor.

4.1 Differences

The two dictionaries are different in the sense that, the Sesuto-English Dictionary was compiled by missionaries in the nineteenth century to assist them to learn and understand Sesotho so that they could evangelise the Basotho. On the other hand, the Sethantso sa Sesotho was written by a Mosotho in the twenty-first century to help the Basotho to use the language appropriately.

The dictionaries are also different in that the former is bilingual while the latter is monolingual. One might argue that this fact does not place the two dictionaries on an equal footing for the purpose of a comparative analysis. However, only the Sesotho section of the bilingual dictionary is compared to entries in the monolingual dictionary. In addition, these dictionaries are the only Sesotho dictionaries of note available currently and much can be learnt from a comparison between the two, even though the former has the non-Sesotho speaker in mind as its target user, while the latter is aimed at both the non-Sesotho and mother-tongue speakers. The dictionaries are of different sizes. Unlike Shiqi's (2003) ancient dictionaries which were smaller than the modern ones, the Sethantso sa Sesotho (recent dictionary) is smaller than the Sesuto-English Dictionary with 9,561 lexical items compared to the 20,039 items included in the Sesotho section alone of the bilingual dictionary. The discussion below will focus on the arrangement of words, word-division, derivation, noun classes and plural morphemes.

4.1.1 Arrangement of words

The two dictionaries use the same orthography and the same orthographical alphabet except that the Sesuto-English Dictionary includes the letters d, g and v which are not in the Sethantso sa Sesotho. All the entries in both dictionaries start with the lemma, which appears in bold type. In both the Sesuto-English Dictionary and the Sethantso sa Sesotho, words are arranged in an ordinary alphabetical order, however, in the Sesuto-English Dictionary the article stretches are represented by monographs, whereas the Sethantso sa Sesotho has utilised phonemic sorting. For instance, in Sethantso sa Sesotho, words are arranged as follows: A, B, Ch, E, F, H, Hl, I, J, K, Kh, K'h, L, M, N, Ng, Ny, O, P, Ph, Pj, Psh, Q, Qh, R, S, Sh, T, Th, Tj, Tl, Tlh, Ts, Ts, U. The digraphs and trigraphs hl [i]; kh [kxh]; k'h [kh ]; ng M; ny [n]; pj [pj]; psh [pjh]; qh [!h]; sh [ƒ]; th [th]; tj [tj]; tl [ti]; tlh [tih]; ts [ts]; ts [tsh] are thus treated as separate article stretches. This implies that words such as hopola (remember) and hula (pull) appear before the word hlaba (prick or sting) in this dictionary. The order itself might cause a problem especially during the first consultation of the dictionary because guidance is not provided to help users know how to search for words. This means that only users who are experts in Sesotho might find the order of words in the Sethantso sa Sesotho easier to understand than those who are learning the language, particularly if they are not sure of the spelling of a word. The latter group might thus not find the phonemic sorting of words user-friendly, despite the fact that the dictionary is intended for both mother-tongue and second-language learners as stipulated in the back-matter, namely that it can be used by students and lecturers of African languages and literature in all the SADC countries. The dictionary does not conform to the user-perspective approach which expects dictionaries to serve the specific needs and research skills of specific target user groups, that is, dictionaries need to provide in the real needs of real users and take into consideration the users' reference skills (Gouws and Prinsloo 2005: 3). Again, those who know the spelling are also likely to be confused because they might think that the word(s) they are looking up are not in the dictionary yet they are there but placed where users are not expecting to find them. According to Prinsloo (2013: 247), dictionaries that use phonemic sorting instead of an alphabetical order, irritate users. He further states that even though the phonemic sorting is based on sound grammatical considerations, users regard it as user-unfriendly.

4.1.2 Word-division

In the Sesuto-English Dictionary, word-division is not indicated while in the Sethantso sa Sesotho verb-roots are separated from the verbal ending/suffixes by a dot [.] to show users where different suffixes can be inserted, because in most cases the verb root does not change. For instance, the lemma kheloh.a (err/turn from) consists of:

Verb-root + verbal-ending

kheloh + a

This indicates that the word is made up of two parts which are /kheloh-/ and /-a/. The first part of the word (i.e. the root) cannot change whereas the second one can change. According to Guma (1971) the verbal root is the central morpheme, which cannot change even after all affixes, whether prefixal, infixal or suffixal, have been removed. This information enables users to know where to insert or not to insert any morpheme. Some of the morphemes that can be put into that slot include past-tense morphemes.

4.1.3 Derivation

In the Sesuto-English Dictionary, derivative forms are presented in the dictionary article of the lemma and are followed by explanations of their meanings. For example:

talima, v.t., to look at, to contemplate, to consider, to watch; to concern one; talimana, to look at one another, to be parallel; taba ena e talimane le 'na, that matter concerns me; italima, v.r., to look at oneself; talimisa, v.t., to cause to look at, to help to consider a question; to direct toward ... (Mabille and Dieterlen 2000: 436).

In the Sethantso sa Sesotho, on the other hand, the derived words appear as separate headwords as in the following extracts:

talim.a(.ile & .me) / kutu-ketso/ ho sheba ho hong kapa e mong; ho boha ho hong ... (<talima) (Hlalele 2005: 260)

talim.an.a(.e) /kutu-ketso/ ho shebana; ho bohana; ho halimana. (<talima) (Hlalele 2005: 260)

talim.el.a(.etse) / kutu-ketso-ketsetso/ ho sheba ho hong ka morero o itseng ... (<talima) (Hlalele 2005: 261).

talim.is.a(.itse) /kutu-ketso-ketsiso/ ho etsa hore ho talingoe ... (<talima) (Hlalele 2005: 261)

The inclusion of (<talima) at the end of each of these articles shows that the headwords are derived from talima which means to look at or to watch. Some users may believe that the above headwords are not related and that also contributed to the number of lexical items treated in Sethantso sa Sesotho. One would assume that if related words are treated as separate headwords, one could have expected an increase in the number of lexical entries in Hlalele (2005) - yet this is not the case.

4.1.4 Noun classes and plural morphemes

Information regarding the noun classes and the plural morphemes is not offered in Sesuto-English Dictionary whereas it is provided in Sethantso sa Sesotho, as in the following examples:

tinkana, n., ox with horns bent forward (Mabille and Dieterlen 2000: 457)

tinkana (li.) /lereho 9/ poho kapa pholo e linaka li koropeletseng ka mahlong (Hlalele 2005: 269).

The (li.) is a plural morpheme of tinkana and the number (9) indicates the noun class of the headword. Provision of the plural morphemes and the noun classes is essential for students and other people who may want to learn the language, hence, making the dictionary user-friendly. These are the major differences seen in the two dictionaries. The following section deals with the similarities.

4.2 Similarities

The gap between the last edition of the Sesuto-English Dictionary (i.e. 1937, before it was revised following the stem approach) and the publication of the Sethantso sa Sesotho (2005) is roughly 68 years. It is therefore, surprising to see that the two dictionaries share the following features: use of foreign sounds and sound patterning, illustrative phrases and use of old/obsolete words. One would have expected a greater measure of modernisation in Sethantso sa Sesotho.

4.2.1 Use of non-standard symbols and atypical sound patterning

The two dictionaries make use of some symbols which are not part of the standard practical orthography of Sesotho as is evident in their use of d and g. The symbol d (phonemically /l/) is utilised in words such as daemane (diamond) instead of taemane and diabolosi (devil) instead of liabolosi (Mabille and Dieterlen 2000: 54). The same dictionary also uses the symbol g (phonemically /x/) in words such as gansi (goose) for khantsi and galasi (glass) for khalasi (Mabille and Dieterlen 2000: 69) etc.

Likewise, the Sethantso sa Sesotho also uses the symbol d which is not represented in the Sesotho orthography. This is evident in its inclusion of words such as adora (to adore), adoreha (adorable) (Hlalele 2005: 1) and sanadere (particular type of gun) (Hlalele 2005: 233).

It is true that the sound [d] is part of the spoken language, but the symbol d is not included in the inventory of Sesotho orthography. The sound [d] is a variant of the phoneme /l/ and is perceived when the phoneme /l/ is followed by the vowels [i] or [u], i.e. when there are syllables with (l + i) = li; and (l + u) = lu. The syllables (li) and (lu) in Sesotho are pronounced as [di] and [du]. Hence, the first syllable of the Sesotho greeting Lumela does not sound like [lu] in Luke but rather like [du]. Hlalele (2005: v) mentions that 'd' is realised when 'l' is used with the vowels 'i' and 'u', but when 'd' is followed by the vowels 'a', 'e' and 'o' it changes to 't'. However, he failed to apply that rule to the words adora, adoreha and sanadere. Hlalele contradicts himself, since he says:

... puo efe kapa efe e na le nteteroane ea eona e sa itsetlehang ho tsa puo tse ling. Haeba taba li tsamaea ka nepo, le mainahano a tsepameng, puo ka 'ngoe e latela tsela ea eona ea mongolo e sa pepang mongolong oa puo tse ling (2005: iv).

(... each language has its own sound system which does not lean on other languages. If things go the right way based on the right thinking, each language should use its own orthography without leaning on other languages - own translation).

According to this statement, each language should use its own orthography as it is a language in its own right. However, based on Hlalele's use of symbols which are not part of the standard Sesotho orthography, one gets confused because it looks like there are exceptional cases which allow users to use d and not t even though Hlalele himself mentioned that the letter d should be changed to t when followed by the vowels a, e and o. Dictionaries are expected to provide users with information (for example, spelling) that is valid and acceptable, however, the inclusion of this type of information may mislead learners in particular. They might believe that the mentioned symbols can be used yet they are not among the standard Sesotho symbols.

Furthermore, both dictionaries utilised atypical sound patterning. This is seen in the inclusion of words such as tramontene or tramtene (turpentine) (p. 473) in the Sesuto-English Dictionary and trakema (drachma) and trakone (dragon) (p. 273) in the Sethantso sa Sesotho. The dictionaries (especially Sethantso sa Sesotho) did not attempt to adapt atypical sound combinations to comply with the open syllable system of Sesotho, whereby unacceptable consonant clusters should be separated by vowels. Even though /t/ and /r/ are among the phonemes of Sesotho, they are not among the consonants that can form consonant clusters. A common Sesotho syllable structure consists of a consonant and a vowel (Guma 1971: 25). On the other hand, vowels are correctly added at the end of these words to comply with the Sesotho syllable structure in a word. All Sesotho words end with vowels except for words ending with ng /q/.

It seems that where the missionaries were unable to represent particular Sesotho sounds in the standard orthography, they utilised symbols from European languages to stand in for sounds which they could not represent otherwise. This is reasonable and understood for foreign language speakers and particularly the missionaries for they were the first to put Sesotho into writing. However, the continued use of non-standard symbols and atypical sound patterning in Sethantso sa Sesotho does not reflect that the new dictionary was produced by a mother-tongue speaker nor that it has moved away from the Sesuto-English Dictionary.

4.2.2 Illustrative phrases and sentences

The use of similar illustrative phrases is another factor that links the Sesuto- English Dictionary and the Sethantso sa Sesotho. It seems that the majority of illustrative sentences which are used in the Sethantso sa Sesotho are duplications of the ones used in the Sesuto-English Dictionary. For example:

khala, n., crab; likhala tsa molapo o le mong, (crabs of the same brook, people of the same kind) (Mabille and Dieterlen 2000: 127)

khala2 (li.) /lereho 9/ phoofotsoana e nyenyane e phelang metsing e tsamaeang ka lekeke. ml. khala tsa molapo o le mong: batho ba morero o le mong, ba mekhoa e tsoanang, ba sepheo se tsoanang, ba utloanang (Hlalele 2005: 80)

khanyapa, n., a fabulous water serpent; selemo sa Khanyapa, 1840 (Mabille and Dieterlen 2000: 129)

khanyapa (li.) /lereho 9/ pula e ngata hoo meholi e phuphuthang fatse 'me lifate li kotohang ka metso; noha eo ho hopoloang hore ke ea metsi 'me ha e falla nakong ea lipula tsa melupe ea litloebelele e heletsa matlo 'me e fothola lifate. Selemo sa khanyapa: selemo se hlahlamang komello e kholo ea lerole le leholo le lefubelu sa 1840 sa pula e bongata bo tsabehang (Hlalele 2005: 82).

phõnyõnyõ, n., something one cannot seize or hold; ho tsoara phonyonyo, to try and to fail (Mabille and Dieterlen 2000: 352).

phonyonyo (#bongata) /lereho 9/ eng le eng e se nang botsoareho. ml. ho tsoara phonyonyo: ho tsoara 'mamphele ka sekotlo; ho ba bothateng; ho itsoarella ka mohatl'a pela (Hlalele 2005: 182)

The italicised phrases or sentences occur in both dictionaries as seen in the above extracts. There are several instances of this, and that proves that the two dictionaries are somehow related. The use of similar illustrative phrases in the dictionary that was published many years after the Sesuto-English Dictionary suggests that the Sethantso sa Sesotho has not moved away from the former. It is assumed that if a different source had been used instead of Sesuto-English Dictionary, the illustrative sentences could have been different.

Ilson (1986) posits that there is nothing wrong with using information from existing dictionaries, because lexicographers have opportunities to add value to the existing data in order to maximise the usefulness of a new dictionary for users. Bothma and Tarp (2012) concur that lexicographers do not only make use of existing lexicographical tools but they reuse and recreate existing data from the database, internet and elsewhere. Again, this is in line with the theory of adaptation, which stipulates that 'art is derived from other arts' (Hutcheon 2013: 2), which simply means that a new text is created with material from elsewhere, i.e. the product is an 'extended reworking of other texts [and] adaptations are often compared to translations' (Hutcheon 2013: 16). This indicates that in adaptation, changes can occur in terms of the order of items/events, reduction or expansion of some material that can lead to major differences between the source, and the adapted text.

4.2.3 Use of old/obsolete words

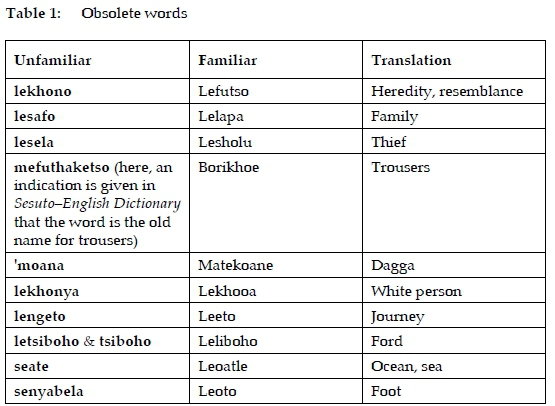

Words which were used during the compilation of Sesuto-English Dictionary (old/obsolete words) are also presented in Sethantso sa Sesotho as if they are common. These words are mostly used by old people and are not common to the contemporary users as they are not found in the majority of literary texts or newspapers. The following words show evidence of such instances:

The words presented in Table 1 above are rarely used but they are presented as if they are common in Sethantso sa Sesotho. This dictionary provided these words without indicating through the use of lexicographic labels that they are archaic. For instance, the Sesuto-English Dictionary revealed that a word such as mefuthaketso (trouser) refers to the 'old' name for trouser but Hlalele presented it as if it is a normal word. Zgusta (1971) posits that all obsolete and regional words should be labelled as such by a sign or label because if this were not done, the word would be regarded as normal or current. The fact that mefuthaketso was already considered 'old' when the Sesuto-English Dictionary was compiled, shows that there is a possibility that users might not encounter it in their daily conversations.

In some instances, the Sethantso sa Sesotho uses unfamiliar words as the headwords and the common words are only found in the explanation of the words in question. That is, the commonly used words do not occur as headwords in the dictionary. When going through the explanation, one notices that the word refers to a known item, which is not in the dictionary. The following extracts bear testimony to such occurrences:

lekhono (#bongata) /lereho 5/ lefutso; tsoano e tsoeleletseng (Hlalele 2005: 115).

letsiboho (ma.) /lereho 5/ moo ho tseloang nokeng; leliboho (Hlalele 2005: 119).

In the above extracts, the words lefutso and leliboho are common but they are not treated as headwords in this dictionary. The fact that Hlalele used the common words while explaining the meanings of the words considered unfamiliar, shows that he was aware of their existence, but he did not include them as main lemmata for some reasons known to him. This type of presentation does not benefit the users who only know the currently used words because it is difficult to anticipate that the known words would appear under the explanation of the meanings of the less familiar words. As a result, one may conclude that Sethantso sa Sesotho seems to have been neglecting the current generation since its focus is similar to that of Mabille and Dieterlen. If Hlalele wanted users to have knowledge of both versions of the words (i.e. former and current usage), he should have included the unknown as well as the known lexical items as headwords in the dictionary. Based on these findings, it is evident that the new dictionary has not distanced itself from the old one and that the changes that have occurred in Sesotho have been neglected.

The shift from dictionaries compiled by the missionaries to modern dictionaries is expected to be seen through the inclusion of current terminology. Mtuze (1992) emphasises that the latest developments are reflected in a dictionary by including neologisms introduced into the lexicon via current politics, technology, diseases, etc. The high frequency words are expected to be given appropriate treatment and consideration in monolingual dictionaries more than in other dictionaries because they are widely used in textbooks (Holi 2012). If we concur with Mtuze's (1992) idea, that the dictionaries produced by the missionaries contain many words that have fallen into disuse, and have limited vocabulary, then Sesotho lexicography has not yet moved away from the past. Many words which are currently used do not occur in this new Sesotho dictionary. Therefore, the study concludes that Sethantso sa Sesotho has moved away only slightly from the Sesuto-English Dictionary. It is as if it was intended for the same target users (i.e. Mabille and Dieterlen's target group). It is also assumed that much of what Hlalele has produced may soon be of little value to the current generation because many of the changes in the Sesotho language were neglected in his dictionary. As a result, the Sethantso sa Sesotho is not considered to be better than Sesuto-English Dictionary.

5. Conclusion and recommendations

In conclusion, it was found that the two dictionaries chosen for comparative analysis in this study, revealed pertinent differences and similarities. They are different in their typology since the Sesuto-English Dictionary is bilingual and was produced by missionaries while the Sethantso sa Sesotho is monolingual and was compiled by a Sesotho mother-tongue speaker. The former was published in the 19th century while the latter was published in the 21st century. The old dictionary is large since it consists of 20,039 headwords in the Sesotho section whereas the number of headwords in the new dictionary is less (only 9,561), contrary to the trend found in studies by Rundell (2008), Hatherall (1986), and El-Badry (1986) which revealed that new dictionaries (particularly, those derived from the former ones) were larger than the old ones and showed a spectacular increase of words over the years and throughout the editions. The Sesuto-English Dictionary is alphabetically ordered while the Sethantso sa Sesotho followed phonemic sorting. Again, the old dictionary does not show word division but the new one does. Derived forms are treated under the same dictionary article in the old dictionary while in the new one they are presented as separate items and the word from which the word is derived is indicated at the end of the dictionary article. In addition, the old dictionary does not provide plural morphemes and classes of nouns while in the new one they are offered. The manner in which the Sethantso sa Sesotho has presented information is considered beneficial to the contemporary user with regard to the indication of noun classes, plural morphemes and word-division. Regarding the similarities, the two dictionaries make use of some symbols which are not part of the standard Sesotho orthography and atypical sound patterning. This suggests that the new dictionary does not fully meet the needs of the current generation. The study concludes that the new dictionary has not distanced itself much from the old one and that the information contained in the new dictionary may soon lose its usefulness.

The study led to the realisation that there is need to produce a new mono-lingual dictionary to improve the existing one. The dictionary to be produced should contain most current words which have entered Sesotho due to science and technology, borrowing, diseases, abuse, politics etc. that have never been written down in dictionaries and other words which are frequently used as well as words from the existing dictionaries. It is necessary to provide detailed information regarding the pronunciation of some Sesotho phonemes which could potentially be pronounced differently by people who are not familiar with the language. It is also recommended that Sesotho dictionaries should be compiled by groups of scholars and not by individuals.

References

Ambrose, D. 2006. Lesotho Annotated Bibliography: Dictionaries and Phrase Books. Maseru: House 9 Publications, National University of Lesotho. [ Links ]

Awak, M.K. 1990. Historical Background, with Special Reference to Western Africa. Hartmann, R.R.K. (Ed.). 1990. Lexicography in Africa: Progress Reports from the Dictionary Research Centre Workshop at Exeter, 24-25 March 1989: 8-18. Exeter Linguistic Studies 15. Exeter: University of Exeter Press.

Bothma, T.J.D. and S. Tarp. 2012. Lexicography and the Relevance Criterion. Lexikos 22: 86-108. [ Links ]

Busane, M. 1990. Lexicography in Central Africa: The User-perspective, with Special Reference to Zaïre. Hartmann, R.R.K. (Ed.). 1990. Lexicography in Africa. Progress Reports from the Dictionary Research Centre Workshop at Exeter, 24-26 March 1989: 19-35. Exeter: Exeter University Press. [ Links ]

El-Badry, N. 1986. The Development of the Bilingual English-Arabic Dictionary from the Middle of the Nineteenth Century to the Present. Hartmann, R.R.K. (Ed.). 1986. The History of Lexicography: 57-64. Studies in the History of the Language Sciences 40. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Gouws, R.H. 2005. Lexicography in Africa. Brown, K. (Ed.). 2005. Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics: 95-101. Second edition. Oxford: Elsevier. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. and D.J. Prinsloo. 2005. Principles and Practice of South African Lexicography. Stellenbosch: SUN PReSS. [ Links ]

Guma, S.M. 1971. An Outline Structure of Southern Sotho. Pietermaritzburg: Shuter and Shooter. [ Links ]

Hatherall, G. 1986. The Duden Rechtschreibung 1880-1986: Development and Function of a Popular Dictionary. Hartmann, R.R.K. (Ed.). 1986. The History of Lexicography: 85-98. Studies in the History of the Language Sciences 40. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Hlalele, B. 2005. Sethantso sa Sesotho. Maseru: Longman. [ Links ]

Holi, I.H.A. 2012. Monolingual Dictionary Use in an EFL Context. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/elt.v5n7p2. [Accessed on 13 March 2014.]

Hutcheon, L. 2013. A Theory of Adaptation. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Ilson, R.F. 1986. Lexicographic Archaeology: Comparing Dictionaries of the Same Family. Hartmann, R.R.K. (Ed.). 1986. The History of Lexicography: 127-136. Studies in the History of the Language Sciences 40. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Laufer, B. 2000. Electronic Dictionaries and Incidental Vocabulary Acquisition: Does Technology Make a Difference? Heid, U., S. Evert, E. Lehmann and C. Rohrer (Eds.). 2000. Proceedings of the Ninth EURALEX International Congress, EURALEX 2000, Stuttgart, Germany, August 8th-12th, 2000: 849-854. Stuttgart: Institut für Maschinelle Sprachverarbeitung, Universität Stuttgart. [ Links ]

Lomicka, L. 1998. "To Gloss or Not to Gloss": An Investigation of Reading Comprehension Online. Language Learning and Technology 1(2): 41-50. Retrieved from http://llt.msu.edu/vol1num2/pdf/article2.pdf. [Accessed on 19 March 2017.]

Mabille, A. and H. Dieterlen. 2000. Sesuto-English Dictionary. Reprint. Morija: Morija Sesuto Book Depot. [ Links ]

Makoni, S. and P. Mashiri. 2007. Critical Historiography: Does Language Planning in Africa Need a Construct of Language as Part of its Theoretical Apparatus? Makoni, S. and A. Pennycook (Eds.). 2007. Disinventing and Reconstituting Languages: 62-89. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Mangoaela, Z.D. 1921. Lithoko tsa Marena a Basotho. Morija: Morija Sesuto Book Depot. [ Links ]

Matsela, F.Z.A. 1994. Sehlalosi: Sesotho Cultural Dictionary. Maseru: Macmillan Boleswa. [ Links ]

Mofolo, T. 1907. Moeti oa Bochabela. Morija: Morija Sesuto Book Depot. [ Links ]

Mofolo, T. 1925. Chaka. Morija: Morija Sesuto Book Depot. [ Links ]

Mtuze, P.T. 1992. A Critical Survey of Xhosa Lexicography 1772-1989. Lexikos 2: 165-177. [ Links ]

Nesi, H. 2000. On Screen or in Print? Students' Use of a Learner's Dictionary on CD-ROM and in Book Form. P. Howarth and R. Hetherington (Eds.). 2000. EAP Learning Technologies. BALEAP Conference Proceedings: 106-114. Leeds: Leeds University Press.

Nkomo, D. 2008. Towards a Theoretical Model for LSP Lexicography in Ndebele with Special Reference to a Dictionary of Linguistic and Literary Terms. Unpublished M.Phil. Thesis. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University. [ Links ]

Otlogetswe, T.J. 2013. Introducing Tlhalosi ya Medi ya Setswana: The Design and Compilation of a Monolingual Setswana Dictionary. Lexikos 23: 532-547. [ Links ]

Paroz, R.A. 1950. Southern Sotho-English Dictionary. Morija: Morija Sesuto Book Depot. [ Links ]

Pitso, T.T.E. 1997. Khetsi ea Sesotho. Cape Town: CTP Book Printers. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, D.J. 2005. Electronic Dictionaries Viewed from South Africa. Hermes, Journal of Linguistics 34: 11-35. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, D.J. 2013. Issues in Compiling Dictionaries for African Languages. Jackson, H. (Ed.). 2013. The Bloomsbury Companion to Lexicography: 232-255. London/New York: Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Rundell, M. 2008. Recent Trends in English Pedagogical Lexicography. Fontenelle, T. (Ed.). 2008. Practical Lexicography: A Reader: 221-243. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Shiqi, X. 2003. Chinese Lexicography Past and Present. Hartmann, R.R.K. (Ed.). 2003. Lexicography: Critical Concepts: 158-173. London/New York: Routledge. www.kwintessential.co.uk/lang. [Accessed on 19 July 2014.] www.thefreedictionary.com/lexical+entry by Farlex. [Accessed on 24 July 2014.]

Zgusta, L. 1971. Manual of Lexicography. The Hague: Mouton. [ Links ]

* This study is based on T.L. Motjope-Mokhali's doctoral thesis A Comparative Analysis of Sesuto-English Dictionary and Sethantso sa Sesotho with Reference to Lexical Entries and Dictionary Design which was submitted to and granted by UNISA, Pretoria in 2016.