Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Lexikos

On-line version ISSN 2224-0039

Print version ISSN 1684-4904

Lexikos vol.30 Stellenbosch 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.5788/30-1-1568

ARTICLES

Special Field and Subject Field Lexicography Contributing to Lexicography

Spesialeveldleksikografie en vakleksikografie lewer 'n bydrae tot leksikografie

Rufus H. Gouws

Department of Afrikaans and Dutch, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa (rhg@sun.ac.za)

ABSTRACT

Restricted dictionaries are fully-fledged dictionaries and their contribution to lexicography should never be underestimated. Because restricted dictionaries often are neglected in lexicographic discussions this article emphasises the significance of their role as members of the lexicographic family. Within a comprehensive dictionary culture the focus should not only be on dictionaries dealing with languages for general purposes but also on dictionaries in which languages for special purposes are treated. This paper firstly offers some terminological clarity and distinguishes between subject field dictionaries and special field dictionaries. The user-perspective is then discussed before it is shown how aspects of a general theory of lexicography also prevail in these dictionaries. This applies among others to the subtypological classification as well as different lexicographic functions. Using a dictionary from each of the categories of subject field and special field dictionaries it is indicated how dictionary structures are employed and further developed in an innovative way. Attention is given to structures like the article structure and the frame structure and to a transtextual approach in monolingual dictionaries with a bilingual dimension. The focus in the discussion of the subject field dictionary is on different aspects of the macrostructure. An explanation is given of double-layered sublemmata and it is shown how integrated macrostruc-tures are employed in this dictionary. It is indicated how this section of the lexicographic practice can enrich the field of metalexicography and dictionary research.

Keywords: back matter texts, double-layered sublemmata, first level SUBLEMMATA, GUIDING ELEMENT, INTEGRATED MACROSTRUCTURE, LEARNER'S DICTIONARY, PARTIAL ARTICLE STRETCHES, SPECIAL FIELD DICTIONARY, SPECIALISED DICTIONARY, SUBJECT FIELD DICTIONARY, SUBLEMMATA, TRANSTEXTUAL APPROACH, USER-PERSPECTIVE

OPSOMMING

Beperkteveldwoordeboeke is volwaardige woordeboeke en hulle bydrae tot die leksikografie mag nie onderskat word nie. Aangesien beperkteveldwoordeboeke dikwels in leksikografiese gesprekke afgeskeep word, beklemtoon hierdie artikel die belang van hulle rol as lede van die woordeboekfamilie. In 'n omvattende woordeboekkultuur moet die fokus nie net op woordeboeke vir taal vir algemene doeleindes wees nie, maar ook op woordeboeke waarin die taal vir spesifieke doeleindes bewerk word. Dié artikel bied eerstens 'n terminologiese vereenduidiging en onderskei tussen vakwoordeboeke en spesialeveldwoordeboeke. Daarna word die gebruikers-perspektief bespreek voordat daar aangetoon word hoe aspekte van die algemene leksikografie ook in hierdie woordeboeke ter sake is. Dit geld onder meer aspekte van die subtipologiese verdeling asook verskillende leksikografiese funksies. Aan die hand van 'n lid van elk van die kategorieë van vak- en spesialeveldwoordeboeke word daar gewys hoe veral woordeboekstrukture op 'n innoverende manier in hierdie woordeboeke benut en aangepas word. Aandag word onder meer gegee aan die artikelstruktuur en die raamstruktuur asook 'n transtekstuele benadering in eentalige woordeboeke met 'n tweetalige dimensie. Die fokus in die bespreking van die vakwoordeboek is veral op verskillende aspekte van die makrostruktuur. 'n Beskrywing word gebied van dubbelvlak-kige sublemmata. Daar word ook gewys hoe geïntegreerde makrostrukture in die betrokke woor-deboek gebruik word. Daar word aangedui hoe vanuit hierdie afdeling van die leksikografie-praktyk die terrein van die metaleksikografie en woordeboeknavorsing verruim kan word.

Sleutelwoorde: AANLEERDERWOORDEBOEK, AGTERTEKSTE, DEELARTIKELTRAJEKTE, DUBBELVLAKSUBLEMMATA, EERSTEVLAKSUBLEMMATA, GEBRUIKERSPERSPEKTIEF, GEÏNTEGREERDE MAKROSTRUKTURE, GIDSELEMENT, SPESIALEVELDWOORDEBOEK, SUBLEMMATA, TRANSTEKSTUELE BENADERING, VAKWOORDEBOEK

1. Introduction

Kilgarriff (2012: 27) says: "When ordinary people refer to dictionaries, they mean general language dictionaries like the Oxford English Dictionary, Le Grand/Petit Robert, Duden, Webster, etc." He criticises an approach where a quantitative comparison between general language dictionaries and what he calls special language dictionaries is used to indicate that many dictionaries do not have language as their object. According to Kilgarriff such a comparison:

"is like noting that there are more local airstrips than international airports in the world, so basing an account of aviation on local airstrips. Numbers of publications alone do not give a good overall picture, and I remain convinced that general language dictionaries are central to the lexicographical firmament."

This central position of general language dictionaries, and to regard them as default or prototypical dictionaries, especially due to their high frequency of use, cannot and should not be disputed. However, one also has to acknowledge the existence of numerous dictionaries that are not general language dictionaries, e.g. those dealing with the terminology of different subject fields. They do not primarily focus on language and do not have the same frequency of use as general language dictionaries, but this does not exclude them from the domain of lexicography. It would be an injustice to underestimate their value as lexicographic products and their contribution to the development of the broad field of lexicography.

According to Wiegand (1989: 251) lexicography is a practice, aimed at the production of dictionaries in order to initiate another practice, i.e. the cultural practice of dictionary use. The lexicographic practice gives evidence of a variety of dictionary types with different aims, objectives, functions and users. The lexicographic practice is comprehensive and all types of dictionaries fall within its scope. This comprehensive nature does not only apply to the lexicographic practice but also to the theoretical component of lexicography, i.e. metalexicog-raphy and dictionary research. Metalexicography and dictionary research are concerned with dictionaries and not only with general language dictionaries. Dictionary research is directed at all types of dictionaries. In this regard Schierholz (2003: 10) says that the total of all theories directed at lexicography and dictionaries as well as the scientific practice are regarded as dictionary research.

Lexicography, both the practice and the theory, contains a variety of subdomains, including domains that have their focus on e.g. general language dictionaries, subject-specific dictionaries or dictionaries focusing on a specific data type, e.g. pronunciation dictionaries or spelling dictionaries.

This paper aims to show some mutual aspects of special field lexicography and general language lexicography. This can be illustrated by means of typological diversity but it can also be seen in the way in which lexicographic functions and different dictionary structures come to the fore in these different domains of the lexicographic practice. Bergenholtz (1995: 53) aptly captures the approach to be followed in this paper, when he says that lexicography has both general language and the language of subject fields in its scope.

2. Towards terminological clarity

2.1 Terminography and special field lexicography

In the fields of lexicography and terminology there are different points of view regarding the use of the terms terminography and special field lexicography and whether they should be regarded as synonyms or not, cf. the well-balanced discussion in Bergenholtz (1995). This distinction will not be discussed in the present paper. The term terminography will not be used here. Instead, the terms special field lexicography and subject field lexicography will be used - but not as synonyms. In the subsequent paragraph the less precise terms specialized dictionaries and specialized lexicography will also be used, albeit that this use will then be discarded.

2.2 Specialised lexicography versus general lexicography

In the English lexicographic terminology it has been a problem to find an unambiguous term for that section of lexicography that does not have general language as its object. Terms like special language dictionaries, subject-specific dictionaries, special field dictionaries, specialised dictionaries and technical dictionaries have been used. Bergenholtz and Tarp's Manual of Specialised Lexicography gave a firm footing to the term specialised dictionaries/lexicography. This term is also used in publications like Schierholz (2003: 5), Fuertes-Olivera (2010), Jesensek (2013) and in translating terms like Fachwörterbuch (Specialized dictionary) and Fachlexikographie (Specialized lexicography) in the Wörterbuch zur Lexikographie und Wörterbuchforschung / Dictionary of Lexicography and Dictionary Research (Wiegand et al. 2010-2020) as well as in the Routledge Handbook of Lexicography (Fuertes-Olivera 2018). In this handbook Humbley (2018: 317) explains the use and scope of this term as follows:

"Specialised dictionaries are defined here by the specialised nature of the subjects they treat, focusing on particular subject fields, professional practices or even leisure activities such as sports ..."

For the general dictionary user and even for the lexicographer it often remains unclear exactly what is meant by specialised lexicography. Does it only refer to dictionaries in which the lexicon of subject fields is treated or also to other dictionaries that do not have the full lexical stock of the general language as its object or do not present a treatment comparable to that of traditional general language dictionaries?

In his typological classification of dictionaries Zgusta (1971: 204) makes a distinction between "general dictionaries on the one side, and restricted (or special) dictionaries on the other". According to Zgusta the restriction lies therein that the lexicographer decides "that he will make his choice from only a certain part of the lexicon of the language." Zgusta argues that there is practically an endless number of different restrictions - reflecting any principle or combination of principles determined by the lexicographer of a dictionary. These include language varieties, slang, jargon, trades, crafts, sports, professional languages, etymology, loan words, abbreviations, etc.

In the comprehensive international encyclopedia of lexicography (Hausmann et al. 1989-1991) the German term Spezialwörterbücher is often used to refer to certain types of restricted dictionaries, e.g. in the table of contents of the second volume Paradigmatische Spezialwörterbücher, Spezialwörterbücher zu markierten Lemmata and Spezialwörterbücher mit bestimmten Informationstypen. The respective English translations of this term are completely unsatisfactory: Paradigmatic dictionaries (no attempt to translate the Spezial-), Dictionaries dealing specifically with marked standard language entrywords and Dictionaries offering specific types of information. English clearly presents no adequate equivalent for this occurrence of Spezial-.

The scope of Zgusta's term restricted dictionary could include dictionaries falling within the scope of both the German terms Fachwörterbuch and Spezialwörterbuch - something not achieved by either specialised dictionary or special field dictionary. In English a clearer terminological differentiation is needed. In this paper the terms special field and subject field will be used. Subject field dictionary will be used as an approximate equivalent of the German Fachwörterbuch and special field dictionary as an approximate equivalent of Spezialwörterbuch. The latter category includes the whole range of Zgusta's restricted dictionaries with the exception of dictionaries dealing with academic subjects. This implies that e.g. dictionaries of football terms, philately, idioms and pronunciation will be regarded as special field dictionaries, whereas dictionaries of e.g. chemistry, linguistics and economics will be regarded as subject field dictionaries.

In the remainder of this paper the focus will be on various aspects of restricted dictionaries to illustrate that subject field and special field lexicography do not only fall within the scope of the overarching discipline of lexicography, but also that the practice of subject and special field lexicography contributes to the development of the broad domain of lexicography.

3. The metalexicographic domain

In the emergence and early development of the discipline of metalexicography and dictionary research there had been a strong focus on general language dictionaries. This was to the detriment of special and subject field lexicography where insufficient in depth research into these domains prevailed, as indicated by Wiegand (1988). During the last decades the situation has improved - as is evident in research publications such as Tarp (1994; 2000), Schierholz (2003; 2013), Wiegand (2003; 2004; 2004a), Fuertes-Olivera and Arribas-Bano (2008), Fuertes-Olivera (2010), Jesensek (2013), Humbley (2018). In various contributions in Hausmann et al. (1989-1991) different types of special field dictionaries have also been discussed. Gouws (2016: 107-109) argues in favour of a comprehensive dictionary culture that should have the full lexicographic spectrum, including both general language and special and subject field dictionaries, in its scope.

Albeit that research into and discussions about special and subject field dictionaries are not yet on equal par with that of general language dictionaries the contributions have shown that special and subject field lexicography belongs to the broader field of lexicography and these publications reflect a significant number of mutual issues between general language and special and subject field lexicography. Some of these aspects will be briefly referred to in the subsequent paragraphs.

4. The user-perspective and dictionary typology

Dictionaries are planned and compiled in response to the needs and reference skills of a well-defined target user group. In general language dictionaries it has been a longstanding approach that diverse target user groups demand different approaches and different dictionaries, even with regard to dictionaries belonging to the same broad category like monolingual or bilingual dictionaries. Bergenholtz and Tarp (2010: 28) indicate that terminographers and most lexicographers agree that terminography differs from lexicography in various ways including: "The target group of terminology is the expert, whereas in lexicography it is the layman." However, a look at the development in the field of lexicography clearly shows that when it comes to subject field lexicography as executed by lexicographers this is not the case. Humbley (2018: 319) recognises different types of users of specialised dictionaries. These user groups are laypersons, educated laypersons and experts. Gouws (2016: 109) complements the classification of experts, semi-experts and laymen made by Bergenholtz and Tarp (1995: 19) with an additional group, namely the informed layperson. This is a layperson in a specific subject field but he or she has acquired some knowledge of that specific field. The user-perspective with regard to the fields of special and specialised lexicography also comes to the fore in modern-day metalexicography publications like Fuertes-Olivera and Arribas-Bano (2008), Fuertes-Olivera (2010) and Jesensek (2013).

Cognizance of the user has also expanded the typological spectrum of subject field dictionaries. One of the major typological explosions in general language dictionaries has been the emergence and growth of pedagogical dictionaries, especially learner's dictionaries, during the last two decades of the previous century. Learner's dictionaries became a significant focal point in metalexicographic discussions, cf. Lemmens and Wekker (1986), Cowie (1987), Hartmann (1992) Van der Colff (1996), Hollos (2004), Steyn (2004), Tarp (2004; 2008) and Runte (2015). This typological category has also found its way into the domain of subject field lexicography, once again cf. Fuertes-Olivera and Arribas-Bano (2008), Fuertes-Olivera (2010) and Jesensek (2013). A growing number of subject field dictionaries have also been compiled for users belonging to the class of learners.

Learner, a more or less unambiguous term in general language lexicography, had also been employed in special and subject field lexicography where it acquired more than one sense. Gouws (2010) already referred to the ambiguity in the use of the word learner when discussing special and subject field dictionaries. In some of these dictionaries the target user is a learner of the specific subject or field, e.g. in the Schüler Duden: Die Musik (Kwiatkowski 1989). In other cases the user is a learner of the language of the dictionary who needs a specific subject field dictionary. An example of such a dictionary is the Oxford Dictionary of Computing for Learners of English (Pyne and Tuck 1996). As stated in its preface, this subject field dictionary has been compiled for users learning the English language. In some cases learner could refer to users with both these qualities. The Ungarisch-Deutsches Deutsch-Ungarisches Fachwörterbuch zur Rentenversicherung (Fata 2005) is a subject field dictionary but it is also intended to be a learner's dictionary used in institutes where German is taught as specialised foreign language.

The user and the subtypological nature of special and subject field dictionaries determine the contents. This is clear when comparing the treatment of the same term in a subject field dictionary for learners of the field and experts in the field. The SASOL Science and Technology Resource (Hartmann-Petersen et al. 2001), a subject field dictionary for school learners, defines the term genome as follows:

The Gene Technology Encyclopedic Dictionary (Kaufmann and Bergenholtz 1998), a subject field dictionary aimed at the expert, defines the same term as:

5. Innovative improvements in the lexicographic practice

The interactive relation between theory and practice in lexicography implies that theory should guide the practice, but it should also be enriched by the practice. This applies to all domains of the lexicographic practice and to a theoretical approach underpinned by a comprehensive and all-inclusive dictionary culture. As a result special and subject field dictionaries need to be products of the application of a sound theoretical approach, and developments in lexicographic theory should also reflect changes initiated in an innovative lexicographic practice. In the remainder of this paper it will be shown how lexicographic theory has contributed to ensuring some good subject and special field dictionaries but also how advances in some of these dictionaries have resulted in improvements in the relevant lexicographic theory - where practice takes the lead and theory has to catch up.

Every dictionary should have an intended target user group and the lexicographic needs and reference skills of this group should determine the contents, functions and structures of the specific dictionary. As seen in the treatment of the term genome the extent of data presented in the item giving the paraphrase of meaning shows a vast difference that is determined by the needs of the target users. The lexicographic functions to be satisfied by a specific dictionary should also be determined in accordance with the user group of that dictionary. The Wörterbuch zur Lexikographie und Wörterbuchforschung / Dictionary of Lexicography and Dictionary Research (Wiegand et al. 2010-2020) is a subject field dictionary compiled for the expert and semi-expert. With regard to lexicographic functions, the typical user consults this dictionary with either a communicative need of text reception or translation or a cognitive need. The article of the lemma sign expandiertes allgemeines Suchbereichsstrukturbild (Figure 3) shows how the text reception function is achieved in the brief item giving a definition (presented in the first search zone) whilst a cognitive function is accounted for in the section introduced by the bullet (•), where additional data transfer and more encyclopedic explanations are presented. The translation function is satisfied by the listing of translation equivalents in the final search zone of the article. The variety of search zones in this article also indicates the way in which an article structure with an appropriate inner access structure gives evidence of a well-planned packaging of data. Theory is applied to practice.

In the subsequent sections it will be shown how the practice of special and subject field lexicography utilises insights from the field of dictionary research in an innovative way to enhance the quality of certain dictionary structures.

5.1 A special field dictionary

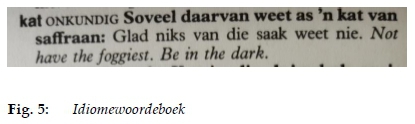

Idiomewoordeboek (De Villiers and Gouws 1988) is a special field dictionary that presents and treats a selection of Afrikaans idioms and fixed expressions. This dictionary illustrates that dictionaries dealing with a subsection of the lexicon of a given language can utilise and improve existing dictionary structures and can enrich the lexicographic practice as well as the field of metalexicography and dictionary research. Figure 4 displays a partial article stretch from this dictionary. Although idioms and fixed expressions are the primary treatment units, they are not the guiding elements of the articles in terms of the outer access structure of the dictionary. Due to practical problems in entering full idioms as guiding elements, this dictionary has opted for a system where a single core word from the expression is entered as guiding element in its alphabetical position. The idiom or fixed expression is entered, in bold, in a separate search zone. In partial article stretches with different articles of idioms and fixed expressions for which the same core word has been selected, there is a repeated occurrence of that core word as iterative guiding element. This can be seen in Figure 4 with regard to the core word kat (cat):

Figure 5 presents the article in which the idiom soveel daarvan weet as 'n kat van saffraan is treated:

In terms of Wolski (1989: 365) the guiding element kat is a lemma part occurring in a lemma-external position, here specifically as guiding element in the article entrance position, albeit isolated from the full form of the lemma sign. Between the guiding element and the idiom functioning as primary treatment unit is the item ONKUNDIG. This item gives the semantic field to which the idiom belongs. The back matter section of this dictionary contains two texts that can assist the user to find idioms and expressions that fall within specific semantic fields. The first text gives the item indicating the semantic field as guiding element of an index article, as seen in Figure 6.

This is followed by a listing of words, that are guiding elements of articles in the main text, containing idioms and expressions that reflect a meaning falling within the specific semantic field. The article of the index lemma ONKUNDIG guides the user, among others, to the guiding element kat where the idiom soveel daarvan weet as 'n kat van saffraan is treated. Where a partial article stretch in the main text contains more than one idiom or fixed expression with the same guiding element, these articles are ordered according to the alphabetical value of the items giving the semantic field - in Figure 4 from NIKS - WAAG.

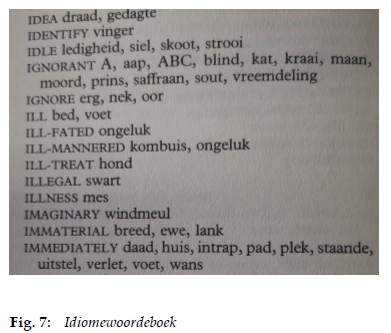

Idiomewoordeboek is a monolingual dictionary that has been partly bilin-gualised (cf. Hartmann 1994). In the main text of the dictionary, the idiom or fixed expression is followed by a brief paraphrase of meaning in Afrikaans (in Figure 5 Glad niks van die saak weet nie). Then one or more items in English follow that present one or more equivalent idioms or fixed expressions in English, or one or more brief paraphrases of meaning (In Figure 5: Not have the foggiest. Be in the dark). This bilingual dimension is continued in the back matter section with a text that contains a list of English words representing the different semantic fields, functioning as guiding elements of the index articles. Figure 7 presents a partial article stretch from this back matter text.

The English item functioning as guiding element of the index article, e.g. IGNORANT in Figure 7, is followed by words directing the user to the relevant idioms or fixed expressions in the central text of the dictionary. These English items do not occur in the central list of the dictionary.

It is clear that the lexicographic process resulting in Idiomewoordeboek was devised in a planned and consistent way. In terms of the discussion of lexicographic processes in Wiegand (1998: 37-38) this dictionary adheres to significant criteria that characterise the lexicographic practice like calculability, analysability, verifiability, regulatability, learnability and testability.

With regard to adhering to and expanding the general theory of lexicographic theory, this dictionary employs and creatively enhances existing lexicographic structures and displays a variety of features accounted for in meta-lexicography as well as innovative adaptations. These innovations are seen in the macrostructural presentation, the article structure and the ordering of items within the articles where both alphabetical and semantic criteria play a determining role, the frame structure, the transtextual use of a bilingual dimension and the poly-accessible nature of this dictionary.

5.2 A subject field dictionary

The structures of some subject field dictionaries also give evidence of the extent to which these restricted dictionaries are rooted in the overarching domain of lexicography and that they do not function alongside it. Existing structures are employed and often adapted in such an innovative way, that these changes activate further research and discussions in the field of metalexicography and dictionary research.

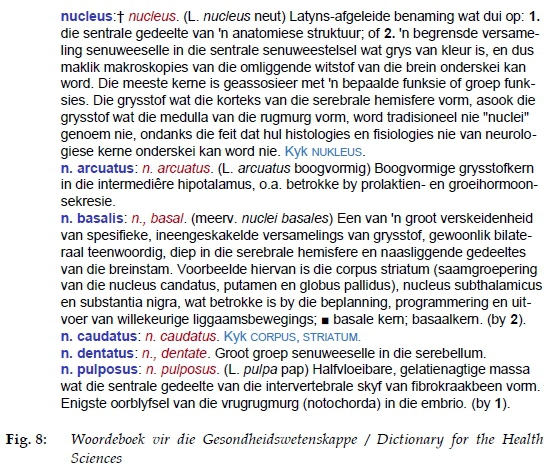

The South African Woordeboek vir die Gesondheidswetenskappe / Dictionary for the Health Sciences (Brink and Lochner 2011), henceforth abbreviated as WGW, has experts and semi-experts in the field of the health sciences as its target user group. This dictionary displays a number of interesting macrostructural strategies.

5.2.1 Macrostructural strategies

5.2.1.1 Sublemmatisation

According to Wiegand and Gouws (2013: 78) the macrostructure of a dictionary is the textual structure that presents the ordering of all the elements that contribute to the macrostructural coverage of the specific dictionary. It is important to note that they refer to all elements of the macrostructural coverage. Bergen-holtz, Tarp and Wiegand (1999) give a comprehensive discussion of the ordering of lemmata in subject field dictionaries. They also refer to the ordering of multiword terms as lemmata and specifically to their occurrence in non-grouped niches (Bergenholtz, Tarp and Wiegand 1999: 1817). The WGW also has to negotiate the inclusion and treatment of numerous multiword terms. Some of these terms are included as main lemmata in the default vertical ordering of the macrostructural presentation, but many are ordered in non-grouped clusters in either a nested or a niched format. According to Gouws (2012: 259) these clusters are often attached to the article of the preceding main lemma of which the lemma sign represents a term that also functions as the initial part of the multiword term. For space-saving reasons this first lemma part is given in an abbreviated format in the cluster, resulting in a partial lemma, cf. Bergenholtz, Tarp and Wiegand (1999: 1817), presented here as sublemma. Attached to the article of the lemma sign nucleus Figure 8 shows the condensed non-grouped niche of partial lemmata, presented as sublemmata: n. arcuatus, n. basalis, n. caudatus, n. dentatus, n. puposus, representing the multiword terms nucleus arcuatus, nucleus basalis, nucleus caudatus, nucleus dentatus and nucleus puposus.

Working with target users that are experts in this field and supposedly have already acquired good reference skills, these ordering and textual condensation procedures should be in order. To enhance the users' success in retrieving the required information the lexicographers also explain their lemmatisation procedures in the user guidelines text in the front matter section.

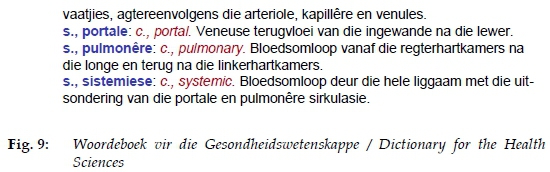

The strategy of including multiword terms as condensed partial sublemmata in non-grouped clusters is taken a step further in article nests that display a lemmatisation procedure where the nest is also attached to the article of a lemma sign that represents a term that is a final part of the multiword term. Figure 9 shows such a partial article stretch of the main lemma sirkulasie and an attached nest of partial sublemmata from s., enterohepatiese to s., sistemiese:

Each article in the nest has a guiding element that has an abbreviation of the preceding main lemma as first component. The comma after the abbreviated lemma part indicates that that lemma part functions as final component of the multiword term that has the subsequent word as first component. The condensed sublemma s., enterohepatiese should accordingly be read as enterohepatiese sirkulasie. This is an example of first level nesting, cf. Gouws (2001: 106), where the alphabetical ordering is maintained within the nest but not with regard to the surrounding main lemmata. In the guidelines to the dictionary this lemmatisation procedure is explained in non-metalexicographic lay terms. It is employed to include sublemmata in close proximity of that main lemma that corresponds to the semantic core of the term presented by the sublemma. In the nested articles in Figure 9 sirkulasie would be the semantic core of the terms presented by the different sublemmata.

Taking cognizance of the diverse lemmatisation procedures in general language dictionaries the WGW does not only follow this example, but also employs other macrostructural strategies. In Figure 10 the main lemma is nekrose and the attached partial article nest contains the non-grouped condensed lemmata that have the partial lemma n., akute tubulêre as nest entrance lemma.

This cluster also displays first level nesting. In populating the nest the primary focus of the lexicographers has not been the lemmatisation of only multiword terms. Besides multiword terms this cluster also contains compounds of which the condensed lemma part is the second stem, and semantic core element, and the non-initial part of the guiding element the first stem of the compound. The compound lemmata in this partial article stretch are n., druk-, n., fosfor- and n., kwik- of which the full forms are druknekrose, fosfornekrose and kwiknekrose.

Nests in general language dictionaries can also include sublemmata with the nest attached to an article of which the lemma sign represents the lexical item that is represented by the non-initial stem of a compound or even the non-initial word of a multiword term. Such a form of lemmatisation is found in Figure 11 from Basiswoordeboek van Afrikaans (Gouws et al. 1994).

Such a co-occurrence of complex words, e.g. musiekkamer, musikant, popmusiek, as well as multiword items, e.g. klassieke musiek, ligte musiek, as sublemmata in a single article nest also prevails in the partial article stretch given in Figure 10. This subject field dictionary also embraces macrostructural strategies devised for general language dictionaries.

5.2.1.2 Double-layered sublemmatisation

The WGW employs a well-known strategy when ordering some compound and multiword lemma candidates as partial lemmata in a cluster of sublemmata within article nests and niches. Relying on this strategy, for both space-saving and semantic reasons, this dictionary takes the initiative to move from a system adhering to single layers of sublemmata to a system where double-layered sublemmata occur (cf. Gouws 2012: 268). Figure 12, a partial article stretch from the WGW, gives evidence of this strategy.

Attached to the article of the lemma sign hemostase is a cluster containing a nest with two sublemmata, i.e. h., eksogene and h., endogene (representing the terms eksogene hemostase and endogene hemostase). These lemmata constitute the first layer of sublemmata. Attached to the article of the sublemma h., endogene, and not to the article of the main lemma hemostase, a further nest occurs, that contains articles of the sublemmata e.h. deur ekstravaskulêre meganismes, e.h. deur intravaskulêre meganismes and e.h. deur vaskulêre meganismes. (endogene hemostase deur ekstravaskulêre meganismes, etc.) These lemmata give evidence of a second level of sublemmata, constituting a process of double-layered sublemmatisa-tion.

This procedure of double-layered sublemmatisation ensures a close proximity between the second layer of sublemmata and their preceding first level sublemma that represents the semantic core of the sublemmata in the second layer. However, it also introduces another significant macrostructural aspect, i.e. the notion of integrated macrostructures.

5.2.1.3 Integrated macrostructure

Wiegand (1989a: 482; 1996: 3) and Wiegand and Smit (2013: 176) discuss different types of microstructures. One of the distinctions they make, is between integrated and non-integrated microstructures. Where an integrated micro-structure prevails each subcomment on semantics has its items giving example sentences positioned in the same integrate as the corresponding item giving the paraphrase of meaning or translation equivalent, as seen in Figure 13, a shortened article from the Macmillan Dictionary (https://www.macmillandictionary.com/dictionary/).

Putting the examples in the same subcomment on semantics as the paraphrase of meaning leads to proximity and a relation of direct addressing between the items giving the examples and the respective item giving the paraphrase of meaning. Proximity enhances comprehensibility.

The use of nesting and niching procedures in the ordering of lemmata shows some resemblance to the notion of integration because a cluster of articles are integrated into a partial article stretch by attaching them to the article of a vertically ordered main lemma. However, although arguments could be offered to support the notion of an integrated macrostructure here, the traditional forms of horizontal lemmatisation by means of niching and nesting are regarded in this paper as well-established lemmatisation procedures and not as instances of an integrated macrostructure. An integrated macrostructure prevails when the lemmatisation procedure that enables closer proximity between sublemmata and a preceding (sub)lemma goes a step further than the traditional forms of sinuous lemma files by means of horizontal ordering. Figure 12 illustrates how macrostructural items are brought into close proximity beyond the first layer of sublemmatisation and clustered as a second layer of partial sublemmata attached to the article of a sublemma. This is one of the types of an integrated macrostructure in the WGW.

The partial article stretch given in Figure 14 shows another example of an integrated macrostructure.

Attached to the article of the main lemma steriliteit the first layer of sublemmata stretches from s., absolute to s., vroulike. The article of the sublemma s., manlike contains a further cluster of sublemmata, i.e. m.s., aspermatogeniese; m.s., dis-spermatogeniese and m.s., normospermatogeniese. The corresponding full forms of these partial sublemmata would be aspermatogeniese manlike steriliteit, dissperma-togeniese manlike steriliteit and normospermatogeniese manlike steriliteit. In this example the second layer of sublemmata is not attached to the article of the preceding first layer sublemma but rather integrated into the article - as signalled by the colon positioned immediately before the second layer of sublemmata. These sublemmata represent terms that indicate defects that can cause the problem referred to by the term functioning as the preceding first level sublemma. The proximity stresses the semantic relation between these two layers of sublemmata.

Another type of integrated macrostructure can be seen in Figure 15.

There is no niche or nest attached to the article of the main lemma tomografie - a niche or nest needs to contain more than one lemma. However, a single sublemma t.,rekenaar (rekenaartomografie), with its abbreviated forms in Afrikaans and English RT, CT, is attached to the article of tomografie. Gouws (2012: 269) refers to such a single sublemma as a macrostructurally-isolated sublemma. The occurrence of this article with the single sublemma as guiding element offers a landing zone for a cluster of nine second level sublemmata of which only the first four are shown in Figure 15. These four second level sublemmata are r, aksiale; r, dinamiese; r, elektronstraal-; and r, enkelfotonemissie. The condensed lemma part r. represents the word rekenaartomografie, the full form of the sublemma of the article to which the second level sublemmata have been attached. The full form of the first of these sublemmata will be aksiale rekenaartomografie. In Figure 15 the integrated macrostructure employs a procedure of double-layering of sublemmata to attach a second level article nest to a macro-structurally-isolated sublemma. Yet again, the integrated macrostructure brings semantically related terms into close proximity - something that could not have been achieved as successfully without the double-layer of sublemmata.

There are two other types of integrated macrostructures prevailing in the WGW that will be discussed briefly - one with double-layered sublemmata and one with single level sublemmata. In the user guidelines of the WGW the editor says that in instances where the main lemma groups a big group of analogous combinations together each combination is treated as a sublemma, ordered alphabetically according to the first letter and numbered accordingly. This can be seen in Figure 16 (which is not an example of an integrated macro-structure) where 16 sublemmata are entered (of which only the first six are given here). They are not compound forms or multiword items in which the term represented by the main lemma occurs but they resemble hyponyms with the main lemma as superordinate. Their inclusion as a specific type of sublemma is determined on semantic grounds. These sublemmata are also entered in cross-reference articles in their respective alphabetical positions elsewhere in the relevant article stretches.

The type of nest with numbered sublemmata as seen in Figure 16 creates an opportunity for an application of double-layered sublemmatisation and the use of additional integrated macrostructural procedures. This can be seen in Figure 17.

Figure 17 presents an occurrence of double-layered sublemmata where a second layer of sublemmata geregtigheid, goedwilligheid, niekwaadwilligheid and outonomie is integrated into the article of a first level sublemma. The lemmata in this second layer are terms representing fundamental principles of norms referred to in the article of the first level sublemma geneeskunde-etiek. This results in an integrated macrostructure - each term is a guiding element and primary treatment unit of an article.

The last type of an integrated macrostructure does not need an occurrence of double-layered sublemmatisation. It is the result of semantically related sublemmata being integrated into different subcomments on semantics of a dictionary article. The article of the polysemous term buis (Figure 18) has three subcomments on semantics, identified by roman numerals given in brackets as polysemy markers. The third subcomment on semantics contains an item giving an English translation equivalent and a cross-reference item guiding the user to the lemma kanaal. The first two subcomments on semantics, each has an item giving a translation equivalent and an item giving a brief paraphrase of meaning. Integrated into these subcomments on semantics are nests with sublemmata presenting both compounds and multiword terms. Each sublemma contains the element buis and they link semantically with that sense of the main lemma buis that prevails in the given subcomment on semantics. The lexicographer has employed an integrated macrostructure to ensure that seman-tically related terms are entered not only in close proximity of the relevant main lemma but in close proximity of the relevant sense.

Integrated macrostructures presuppose a system where the vertical ordering of lemmata is complemented by a horizontal ordering. Two main types of integrated macrostructures have been employed in the WGW. Figures 12, 14 and 15 display the first type of integrated macrostructure. The integration is due to a second layer of sublemmata where the sublemmata are either integrated into the partial article stretch of first level sublemmata (Fig. 12), integrated into a partial article stretch by being attached to macrostructurally-isolated first level sublemma (Fig. 14) or integrated into an article of a first level sublemma (Fig. 15). Figure 17 shows a variant of this first type but where there is a relation between a nest of numbered sublemmata integrated into the article of a first level sublemma and a concept referred to in the preceding treatment of the first level sublemma. They are integrated into the article of the first level sublemma.

The second type of integrated macrostructure is seen in Figure 18. Here the first layer of sublemmata are integrated into separate subcomments on semantics of the article of a main lemma, signalling that there is a close semantic relation between the sublemmata and the sense of the main lemma expressed in the specific subcomment on semantics.

6. In conclusion

Special field lexicography and subject field lexicography are subdomains of lexicography. Typical lexicographic procedures are used in these dictionaries. Where the compiler of such a dictionary takes the necessary cognizance of guidelines from a general theory of lexicography such a dictionary can become a good dictionary not only on account of the contents but also due to the appropriate dictionary structures and an adherence to the user-perspective and the relevant lexicographic functions. Lexicographers of special field and subject field dictionaries often employ lexicographic procedures and structures in an innovative way. This gives theoretical lexicographers the opportunity to analyse and discuss these innovations, and use them as a point of departure from where the fields of metalexicography and dictionary research can be enriched.

Acknowledgement

This work is based on the research supported in part by the National Research Foundation of South Africa (Grant specific unique reference number (UID) 85434). The Grantholder acknowledges that opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in any publication generated by the NRF supported research are that of the author(s), and that the NRF accepts no liability whatsoever in this regard.

References

Dictionaries

Brink, A.J. and J. de V. Lochner (Eds.). 20112. Woordeboek vir die Gesondheidswetenskappe/Dictionary for the Health Sciences. Cape Town: Pharos. [ Links ]

De Villiers, M. and R.H. Gouws. 1988. Idiomewoordeboek. Cape Town: Nasou. [ Links ]

Fata, I. 2005. Ungarisch-Deutsches Deutsch-Ungarisches Fachwörterbuch zur Rentenversicherung. Szeged: Grimm Kiadó [ Links ].

Gouws, R. et al. (Eds.). 1994. Basiswoordeboek van Afrikaans. Pretoria: J.L. van Schaik [ Links ]

Hartmann-Petersen, P. et al. 2001. SASOL Science and Technology Resource. Claremont: New Africa Education Publishing. [ Links ]

Kaufmann, U. and H. Bergenholtz (Eds.). 1998. Encyclopedic Dictionary of Gene Technology. Toronto: Lugus Libros. [ Links ]

Kwiatkowski, G. (Ed.). 19892. Schüler Duden: Die Musik. Mannheim: Dudenverlag. Macmillan Dictionary. https://www.macmillandictionary.com/dictionary/. (Consulted 10 February 2020.)

Pyne, S. and A. Tuck. 1996. Oxford Dictionary of Computing for Learners of English. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Wiegand, H.E. et al. (Eds.). 2010-2020. Wörterbuch zur Lexikographie und Wörterbuchforschung / Dictionary of Lexicography and Dictionary Research. Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Other literature

Bergenholtz, H. 1995. Wodurch unterscheidet sich Fachlexikographie von Terminographie? Lexicographica 11: 50-59. [ Links ]

Bergenholtz, H. and S. Tarp (Eds.). 1995. Manual of Specialised Lexicography. The Preparation of Specialised Dictionaries. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Bergenholtz, H. and S. Tarp. 2010. LSP Lexicography or Terminography? The Lexicographer's Point of View. Fuertes-Olivera, P.A. (Ed.). 2010: 27-38.

Bergenholtz, H., S. Tarp and H.E. Wiegand. 1999. Datendistributionsstrukturen, Makro- und Mikrostrukturen in neueren Fachwörterbüchern. Hoffmann, L. et al. (Eds.). 1999. Fachsprachen. Ein internationales Handbuch zur Fachsprachenforschung und Terminologiewissenschaft/ Languages for Special Purposes. An International Handbook of Special-Language and Terminology Research, Bd./Vol. 2: 1762-1832. Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Cowie, A.P. (Ed.). 1987. The Dictionary and the Language Learner. Papers from the EURALEX Seminar at the University of Leeds, 1-3 April 1985. Lexicographica. Series Maior 17. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer. [ Links ]

Fuertes-Olivera, P.A. (Ed.). 2010. Specialised Dictionaries for Learners. Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Fuertes-Olivera, P.A. (Ed.). 2018. The Routledge Handbook of Lexicography. London/New York: Rout-ledge. [ Links ]

Fuertes-Olivera, P.A. and A. Arribas-Bano (Eds.). 2008. Pedagogical Specialised Lexicography: The Representation of Meaning in English and Spanish Business Dictionaries. Terminology and Lexicography Research and Practice (TLRP) 11. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. 2001. The Use of an Improved Access Structure in Dictionaries. Lexikos 11: 101-111. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. 2010. The Monolingual Specialised Dictionary for Learners. Fuertes-Olivera, P.A. (Ed.). 2010: 55-68.

Gouws, R.H. 2012. Innovative Strategies in Macrostructural Choices. Ndinga-Koumba-Binza, H.S. and S.E. Bosch (Eds.). 2012. Language Science and Language Technology in Africa. Stellenbosch: Sun Press: 251-269.

Gouws, R.H. 2016. Increasing the Scope of the Treatment of Specialised Language Terms in General Language Dictionaries. Schierholz,S. et al. (Eds.). 2016. Wörterbuchforschung und Lexikographie. Berlin: De Gruyter: 101-118.

Gouws, R.H. et al. (Eds.). 2013. Dictionaries. An International Encyclopedia of Lexicography. Supplementary Volume: Recent Developments with Focus on Electronic and Computational Lexicography. Berlin/New York: De Gruyter. [ Links ]

Hartmann, R.R.K. 1992. Lexicography, with Particular Reference to English Learners' Dictionaries. Language Teaching 25(3): 151-159. [ Links ]

Hartmann, R.R.K. 1994. Bilingualised Versions of Learners' Dictionaries. Fremdsprachen Lehren und Lernen 23: 206-220. [ Links ]

Hausmann, F.J. et al. (Eds.). 1989-1991. Wörterbücher. Ein internationales Handbuch zur Lexikographie/ Dictionaries. An International Encyclopedia of Lexicography/Dictionnaires. Encyclopédie internationale de lexicographie. Handbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft 5.1-5.3. Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Hollos, Z. 2004. Lernerlexikographie: syntagmatisch. Konzeption für ein deutsch-ungarisches Lernerwör-terbuch.Tübingen: Max Niemeyer. [ Links ]

Humbley, J. 2018. Specialised Dictionaries. Fuertes-Olivera, P.A. (Ed.). 2018: 317-334.

Jesensek, V. (Ed.). 2013. Specialised Lexicography. Print and Digital, Specialised Dictionaries, Databases. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter. [ Links ]

Kilgarriff, A. 2012. Review of Pedro A. Fuertes-Olivera and Henning Bergenholtz (Eds.). e Lexicography: The Internet, Digital Initiatives and Lexicography. Kernerman Dictionary News 20: 26-29. [ Links ]

Lemmens, M. and H. Wekker. 1986. Grammar in English Learners' Dictionaries. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer. [ Links ]

Runte, M. 2015. Lernerlexikographie und Wortschatzerwerb. Lexicographica. Series Maior 150. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter. [ Links ]

Schierholz, S.J. 2003. Fachlexikographie und Terminographie. Zeitschrift für Angewandte Linguistik 39: 528. [ Links ]

Schierholz, S.J. 2013. New Developments in Lexicography for Special Purposes I: An Overview of Linguistic Dictionaries. Gouws, R.H. et al. (Eds.). 2013: 431-442.

Steyn, M. 2004. The Access Structure in Learner's Dictionaries. Lexikos 14: 275-298. [ Links ]

Tarp, S. 1994. Funktionen in Fachwörterbüchern. Schaeder, B. and Bergenholtz, H. (Eds.). 1994. Fachlexikographie. Fachwissen und seine Repräsentation in Wörterbüchern: 229-246. Tübingen: Gunter Narr. [ Links ]

Tarp, S. 2000. Theoretical Challenges to Practical Specialised Lexicography. Lexikos 10: 189-208. [ Links ]

Tarp, S. 2004. Basic Problems of Learner's Lexicography. Lexikos 14: 222-252. [ Links ]

Tarp, S. 2008. Lexicography in the Borderland between Knowledge and Non-knowledge. General Lexicographical Theory with Particular Focus on Learner's Lexicography. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer. [ Links ]

Van der Colff, A. 1996. Zur Konzeption eines einsprachigen deutschen Lernerwörterbuchs. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University. [ Links ]

Wiegand, H.E. 1988. Was eigentlich ist Fachlexikographie? Haider Munske, H. et al. (Eds.). 1988. Deutscher Wortschatz. Lexikologische Studien. Berlin: De Gruyter: 729-790.

Wiegand, H.E. 1989. Der gegenwärtige Status der Lexikographie und ihr Verhältnis zu anderen Disziplinen. Hausmann, F.J. et al. (Eds.). 1989-1991: 246-280.

Wiegand, H.E. 1989a. Arten von Mikrostrukturen im allgemeinen einsprachigen Wörterbuch. Hausmann, F.J. et al. (Eds.). 1989-1991: 462-501.

Wiegand, H.E. 1996. Das Konzept der semiintegrierten Mikrostrukturen. Ein Beitrag zur Theorie zweisprachiger Printwörterbücher. Wiegand, H.E. (Ed.). 1996. Wörterbücher in der Diskussion II. Vorträge aus dem Heidelberger lexikographischen Kolloquium: 1-82. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer. [ Links ]

Wiegand, H.E. 1998. Wörterbuchforschung. Berlin: De Gruyter. [ Links ]

Wiegand, H.E. 2003. Wörterbuch zur Lexikographie und Wörterbuchforschung. Dictionary of Lexicography and Dictionary Research. Städler, Thomas (Ed.). 2003. Wissenschaftliche Lexikographie im deutschsprachigen Raum. Im Auftrag der Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften: 417-437. Heidelberg: Winter. [ Links ]

Wiegand, H.E. 2004. Über die Unterschiede von Fachlexikographie und Terminographie. Am Beispiel des Wörterbuchs zur Lexikographie und Wörterbuchforschung. Wiegand, H.E. (Ed.). 2004. Studien zur zweisprachigen Lexikographie mit Deutsch IX: 135-152. Germanistische Linguistik 178. Hildesheim/Zürich/New York: Georg Olms. [ Links ]

Wiegand, H.E. 2004a. Reflections on the Mediostructure in Special-Field Dictionaries. Also According to the Example of the Dictionary for Lexicography and Dictionary Research. Lexikos 14: 195-221. [ Links ]

Wiegand, H.E. and R.H. Gouws. 2013. Macrostructures in Printed Dictionaries. Gouws, R.H. et al. (Eds.). 2013: 73-110.

Wiegand, H.E. and M. Smit. 2013. Microstructures in Printed Dictionaries. Gouws, R.H. et al. (Eds.). 2013: 149-214.

Wolski, W. 1989. Das Lemma und die verschiedenen Lemmatypen. Hausmann, F.J. et al. (Eds.). 1989-1991: 360-371.

Zgusta, L. 1971. Manual of Lexicography. The Hague: Mouton. [ Links ]