Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Lexikos

On-line version ISSN 2224-0039

Print version ISSN 1684-4904

Lexikos vol.30 Stellenbosch 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.5788/30-1-1548

ARTICLES

Valency Dictionaries and Chinese Vocabulary Acquisition for Foreign Learners

Valensiewoordeboeke en Chinese woordeskatverwerwing vir vreemdetaalleerders

Jun GaoI; Haitao LiuII

ISchool of Foreign Languages, Zhejiang Gongshang University, Hangzhou, China (gj821211@hotmail.com)

IIInstitute of Quantitative Linguistics, Beijing Language and Culture University, Beijing, China; Department of Linguistics, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China; Ningbo Institute of Technology, Zhejiang University, Ningbo, China (Corresponding Author, htliu@163.com)

ABSTRACT

Valency is a major source of lexical errors in foreign language learning. Accordingly, the research question is how the syntactic and semantic properties of a word can be retrieved from the corpora and represented in a Chinese valency dictionary to facilitate foreign learners' vocabulary acquisition. Within the three aspects of the valency framework - logical-semantic, syntactic and semantic-pragmatic valency - this study examines 60 cases of Chinese lexical misuse extracted from the HSK (Chinese Language Proficiency Test) Dynamic Compositions Corpus. The results suggest that the majority of cases of misuse occur in the dimension of semantic-pragmatic valency and that this semantic-pragmatic misuse can be ascribed to various factors such as semantic collocations, emotive variables, text styles, registers, and other contextual factors. The results are then utilized as syntactic, semantic and pragmatic information to be presented in a Chinese valency dictionary. Specifically, the results obtained from a case study of a misused word by referring to a large-scale native Chinese speaker corpus help retrieve a relatively full list of complementation patterns, based on which the study designs a Chinese valency entry that embodies three basic elements - quantitative valency, qualitative valency and valency patterns.

Keywords: Chinese Valency Dictionary, Valency Entry, Logical-semantic Valency, Syntactic Valency, Semantic-pragmatic Valency, Chinese Vocabulary Acquisition, Lexical Misuse, Complementation Patterns, Learner Corpus, Native Speaker Corpus

OPSOMMING

Valensie is 'n groot bron van leksikale foute in die aanleer van 'n vreemde taal. Gevolglik ontstaan die vraag hoe sintaktiese en semantiese eienskappe van 'n woord uit die korpus verkry en in 'n Chinese valensiewoordeboek weergegee kan word om woordeskat-verwerwing vir vreemdetaalleerders te vergemaklik. Met inagneming van die drie aspekte van 'n valensieraamwerk - logies-semantiese, sintaktiese en semanties-pragmatiese valensie - word 60 gevalle van Chinese leksikale foute wat uit die HSK (Chinese Taalvaardigheidstoets) Dinamies Saamgestelde Korpus onttrek is, bestudeer. Die resultate dui daarop dat die meeste van die foute plaasvind in die semanties-pragmatiese valensie-dimensie en dat hierdie semanties-pragmatiese foute toegeskryf kan word aan verskeie faktore soos semantiese kollokasies, emotiewe verander-likes, teksstyle, registers, en ander kontekstuele faktore. Die resultate word dan benut as sintak-tiese, semantiese en pragmatiese inligting wat in 'n Chinese valensiewoordeboek weergegee moet word. Meer spesifiek, die resultate wat verkry word uit 'n gevallestudie van 'n verkeerd gebruikte woord wat onttrek is uit 'n grootskaalse Chinese moedertaalssprekerskorpus, help om 'n relatief volledige lys aanvullingspatrone, wat gebaseer is op die studieontwerpe van 'n Chinese valensie-inskrywing wat drie basiese elemente insluit - kwantitatiewe valensie, kwalitatiewe valensie en valensiepatrone - te verkry.

Sleutelwoorde: Chinese valensiewoordeboek, valensieinskrywing, logiessemantiese valensie, sintaktiese valensie, semanties-pragmatiese valensie, chinese woordeskatverwerwing, leksikale wangebruik, aanvullings-patrone, aanleerderskorpus, moedertaalkorpus

1. Introduction

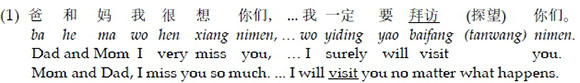

A word, as a 'composite unit of form and meaning' (Lyons 2000: 23), has invariably been in the limelight of foreign language teaching and learning. Traditionally, the teaching of Chinese as a foreign language has centered on grammar while neglecting vocabulary to some extent. Sun (2006) argues that vocabulary should assume a fundamental role in Chinese teaching since it is on the basis of vocabulary that grammatical rules can be established. In practical learning, only a handful of lexical problems such as synonyms are posed and addressed in the classroom; whereas, a considerable number of lexical puzzles emerge from learners' daily study due to the specific features of Chinese vocabulary such as flexibility of word order and lack of inflections and derivations (Sun 2006). What follows is a case of misuse of baifang  visit) found in the HSK Dynamic Compositions Corpus (a corpus that collected the writings of non-native Chinese learners who participated in the HSK advanced level writing tests). The correct word is offered in the parentheses:

visit) found in the HSK Dynamic Compositions Corpus (a corpus that collected the writings of non-native Chinese learners who participated in the HSK advanced level writing tests). The correct word is offered in the parentheses:

In this example, the examinee intended to express the meaning 'to pay a visit to his or her parents'. However, despite the fact that both baifang  and tanwang

and tanwang  are honorific verbs whose PATIENTs are the elder members of one's family, 'parents' are excluded from the list of semes (i.e. semantic features) presupposed by the PATIENT of baifang. In this respect, baifang and tanwang are synonyms and share the same English equivalent 'visit', but require different semantic features for their PATIENTs. Without solid lexical knowledge or proper guidance from teachers and reference books, learners tend to misuse the word.

are honorific verbs whose PATIENTs are the elder members of one's family, 'parents' are excluded from the list of semes (i.e. semantic features) presupposed by the PATIENT of baifang. In this respect, baifang and tanwang are synonyms and share the same English equivalent 'visit', but require different semantic features for their PATIENTs. Without solid lexical knowledge or proper guidance from teachers and reference books, learners tend to misuse the word.

As the 'silent teacher', learners' dictionaries are expected to provide systematic information of lexical usage. However, compared with the worldwide popularity of English learners' dictionaries, Chinese dictionaries for foreign learners (hereafter CLDs) have received scant attention. According to the investigation conducted by Xie et al. (2015: 4), more than 80% of foreign learners of Chinese 'do not know or barely know' CLDs. Most of them consult Chinese or Chinese-English dictionaries compiled for native speakers of Chinese. This situation may cause problems for foreign learners. Therefore, it is an urgent task to enhance learners' awareness of using CLDs.

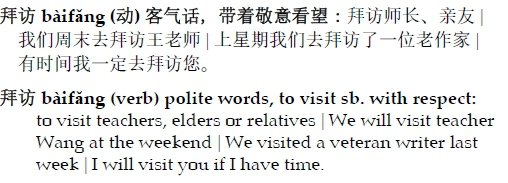

Apart from enhancing learners' awareness, the quality and user-friendliness of CLDs need to be considered. Nevertheless, existing CLDs have some weaknesses that might not cater for learners' practical needs. For instance, Zhang (2011) points out that the system of CLDs, especially their definitions, largely follow the fashion of traditional Chinese dictionaries for native speakers; Xie et al. (2015) found that it is rather common that present CLDs lack systematic syntactic and pragmatic information. For example, the following entry of baifang in the Commercial Press Learners' Dictionary of Contemporary Chinese (Lu and Lv 2007) only shows one syntactic pattern - (NP) + VP + NP, and it lacks the pragmatic information of excluding 'parents' from the object slot of visiting:

Another problematic situation is that foreign learners, as noted, are inclined to consult Chinese-English dictionaries and that most monolingual CLDs provide simple English equivalents for the Chinese entry-words. Thus, English, as the international language, may influence the acquisition of Chinese vocabulary to some degree. In Example 1, learners' incomplete lexical knowledge of baifang and their association with the English equivalent 'visit' may cause the negative transfer and make a syntactically-correct but semantically-and-pragmatically-incorrect sentence. The mastery of the three aspects of a word - syntactic, semantic and pragmatic - is essential in foreign language learning. To achieve this goal, foreign learners need a CLD that offers systematic information on words.

In this regard, valency theory and valency dictionaries, having proved to be effective in foreign language teaching and learning (Herbst and Götz-Vot-teler 2007; Helbig and Schenkel 1969), could lend theoretical and practical support for foreign learners to acquire Chinese vocabulary in that valency constructions present the syntactic-semantic-pragmatic information of lexical units in a systematic and comprehensive manner.

It is generally acknowledged that modern valency theory was founded by French linguist Lucien Tesnière (1959) and was then systematically developed by German scholars. The notion of valency was borrowed from chemistry. As atoms have the ability to combine with a certain number of other atoms to constitute larger units, words have the property of attracting a selected number of words to form larger units. Accordingly, valency can be generally defined as the 'ability of words to combine in this way with other words' (Herbst et al. 2004: vii). The first valency dictionary of German verbs was compiled in 1969 by German linguists Helbig and Schenkel, and then Sommerfeldt and Schreiber published valency dictionaries of German adjectives and nouns respectively in 1974 and 1977. Not incidentally, the first English valency dictionary (VDE) was also compiled by scholars from Germany (Herbst et al. 2004). One of the principal aims of valency dictionaries, as argued by Herbst et al. (2004: vii), is to help 'advanced foreign learners to write grammatically correct and idiomatic English because it shows them in which constructions a word can be used'. In this respect, the nature of valency dictionaries tallies with that of learners' dictionaries as the lat-ter's 'most interesting features are their efforts to develop new ways of defining words and provide information necessary for encoding' (Béjoint 2002: 73).

VDE is by nature a descriptive dictionary that provides a comprehensive depiction of the valency properties of the English lexicon. The representation of comprehensive lexical information is realized by its profuse use of grammatical and semantic codes extracted and synthesized from the Bank of English and the COBUILD-corpus of present-day English. Metalexicographers have expressed their concern over the use of codes in general-purpose learners' dictionaries: while compilers spare no efforts to include information for encoding in the dictionary, users take far less interest in consulting this type of information since they find information in coded form is too dense, confusing and time-consuming for grasping (Béjoint 2002; Cowie 2002). However, this concern about the usability of coded information for language production can possibly be lessened when taking into account users' study activities and proficiency level as well as the purpose of the dictionary. Bareggi's (1989) study shows that first-year undergraduates of English tend to use dictionaries mainly for decoding activities while from the third year on, they begin to attach equal importance to encoding. Bareggi (1989) also indicates that only 50 percent of the freshmen are able to comprehend grammatical codes, but for juniors, the figure rises to almost 100 percent. Neubach and Cohen (1988) also confirm that learners with high proficiency are better at making use of the dictionary information than those with low proficiency. At this point, VDE, as stated, primarily aims to serve the advanced learners in their encoding activities. It is expected that the intended users of VDE, if properly trained, can better understand and exploit the information for encoding activities.

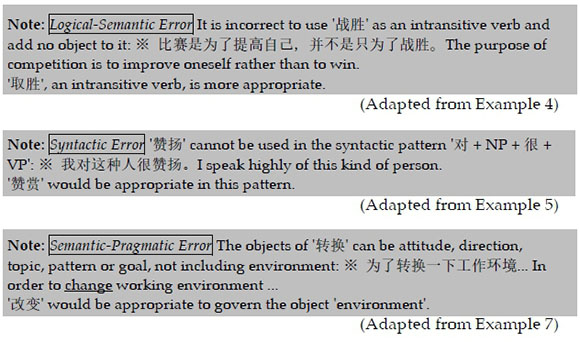

Despite its strengths, Fillmore (2008) points out some weaknesses of VDE, which may impair its practicability. For instance, VDE treats verbs in detail and at length while not giving equal weight to nouns and adjectives. Particularly, the nouns derivationally related to verbs have combinatory properties similar to those of the corresponding verbs and thus need to be treated equally. This critical point is a significant reminder for future research and compiling of a Chinese valency dictionary undertaken by the present study. Moreover, 'by being corpus-based and therefore non-prescriptive, VDE has no way to introduce negative evidence, and the entries are not set up to include warnings about mistakes' (Fillmore 2008: 78). This indicates the importance of including learner corpora, in addition to native speaker corpora, in the construction of a Chinese valency dictionary to provide prescriptive guidelines for users. Therefore, apart from the description of valency information gained from a native speaker corpus (CCL), the current study will provide 'Note' blocks, alerting the users to common lexical errors extracted from a learner corpus (HSK Corpus). (See examples in Section 3.4 and Figure 3 in Section 4.)

Just as the compilation of VDE was greatly influenced by German thoughts of valency, the introduction of valency theory into China was initially promoted by Chinese scholars of German language (Wu 1996). Valency theory was widely used in the study of Chinese grammar (Shen 2000; Shen and Zhen 1995; Yuan 2010; Zhou 2011) and teaching Chinese as a foreign language (Lu 1997; Shao 2002). Correspondingly, some scholars proposed that the theoretical framework of valency be employed to construct CLDs. Mei (2003) believes that valency theory can be utilized to help set up the grammatical information of modern Chinese learners' dictionaries. With regard to the difficult issue of synonym discrimination that often challenges foreign learners of Chinese, Zhang's (2007) study holds that the syntactic, semantic and pragmatic levels explicitly presented by valency models can provide elaborate discriminatory information of synonyms. Xu (2012) examines divalent Chinese nouns in the Contemporary Chinese Dictionary (native-speaker-oriented) and the Commercial Press Learners' Dictionary of Contemporary Chinese (foreign-learner-oriented). Xu (2002) found that about 40% of the lexicographic definitions and examples in these two dictionaries do not incorporate valency elements. This calls for the urgent task of systematically organizing the complements of divalent nouns in CLDs. Furthermore, Han and Han (1995a and 1995b) endeavoured to compile a 'con-trastive German-Chinese valency dictionary of verbs'. Taking Mannheim school's valency theory as the foundation, they adopted a semantic view of valency for describing Chinese verbs' valency patterns. Similarly, Zhan (2000) proposed to develop a valency-based dictionary - A Valency-Based Semantic Dictionary. Zhan (2000) holds the view that the representation of the semantic valency information of a Chinese synonymous word in the dictionary can help differentiate the semantic collocations in its different senses, thus assisting the computer to identify accurate English equivalents.

In light of the previous review of valency dictionaries, the research into and the compilation of a Chinese valence dictionary for foreign learners, which primarily aims to provide comprehensive syntactic-semantic-pragmatic information of lexical units, is of practical significance. For one thing, the inclusion of valency into dictionaries can solve, at least to a considerable degree, the problems of current CLDs such as lack of syntactic information, under-differentiated senses and ill-arrangement of examples according to syntactic features of the headwords. For another, there are only limited studies that relate valency theory to CLDs. Some of these studies base the syntactic and semantic collocation information on researchers' intuition and introspection rather than on corpus evidence. In this regard, the present study follows the compilation principle of the Valency Dictionary of English, which combines 'corpus research and the theoretical background of valency theory' (Herbst et al. 2004: xxii). On account of these problems and facts, the research question of this study is how the syntactic and semantic properties of a word can be retrieved from the corpora and be presented in a Chinese valency dictionary to facilitate foreign learners' vocabulary acquisition. To answer this question, the study firstly elaborates on valency theory and key concepts of the user perspective (Section 2). It then employs two Chinese corpora and the Valency Dictionary of English to analyze the misuse of Chinese vocabulary within the valency framework, for the purpose of setting up a database for the construction of a Chinese valency dictionary (Section 3). Finally, the study tentatively designs a valency entry of a Chinese word based on the results of analysis (Section 4).

2. Valency theory and the user perspective

This section lays the theoretical basis from two parts. One is the construction of a valency framework for data analysis and discussion as well as the design of a valency entry in a proposed Chinese valency dictionary. Another part is the user perspective from which the user-friendliness of the Chinese valency dictionary undertaken by this research project can be enhanced.

2.1 The valency framework

Different researchers compare valency to different but similar concepts. Tes-nière, the founder of valency theory, perceives a verb as an 'atome crochu' (atom with hooks) which can attract a certain number of actants as its 'dépendance' (1959: 238). De Groot (1949) focuses on the idea of 'restriction', arguing that different classes of words have different patterns of syntactic valency and that valency refers to the possibility and impossibility of headwords restricting or being restricted by other words. Therefore, valency is not an exclusive property of verbs but a shared capacity of all other word classes such as nouns, adjective, adverbs, prepositions, numerals, etc. In fact, Sections 73 to 77 in Tesnière's (1959) work discusses the valency structure of nouns, adjectives and adverbs. Kacnel'son's (1948 and 1988) key idea is 'potentiality', defining a word as a lexical unit that has syntactic potentiality, which enables content words to combine with other words. Hence, valency is regarded as a means to express potential syntactic relations or to uncover potential grammatical phenomena.

Based on Tesnière and other forerunners, German scholars developed the valency theory into a system. In general, the valency framework constructed by German scholars can be summarized with regard to three dimensions: logical-semantic, syntactic and semantic (Gao and Liu 2019; Han 1993 and 1997). Bondzio (1978) upholds the concept of logical-semantic valency. A headword has the ability of governing other words (i.e. complements) by assigning different semantic roles to them. For example, the verb visit reveals the relation between 'visitor' and 'the visited'. Bondzio (1978) adopts the term 'slot' from logic to refer to the relations between the headword and its dependents. In this respect, visit has two slots determined by its semantic components. Accordingly, these conceptually based slots constitute the valency of a word, and the number of slots corresponds to the number of valency. Hence, logical valency relates to the quantitative aspect of valency.

Syntactic valency, put forward by Helbig (1992), is the formal realisation of logical valency in a language. In a particular sentence, the logical-conceptual relations are transformed into syntactic relations. However, syntactic structure and logical structure do not coincide on many occasions because sometimes the former cannot fully realize the latter. For instance, logically, give is a trivalent verb that can govern three elements 'agent', 'patient' and 'recipient'. Syntactically, give can be a monovalent, divalent or trivalent verb as in the sentences To give or take is a choice, They were given a box to carry and My teacher gives me a book. Therefore, a logical valency structure may have different syntactic representations.

Different from logical valency, semantic valency is concerned with the semantic or collocational properties of the headword. The semantic roles assumed by the complements of the headword, as depicted in logical valency, need to have compatible properties in order to combine with the headword (Han 1993). As seen in the Introduction, baifang visit) prerequires its PATIENTs to have the semantic feature of 'elder members of one's family, not including parents'. As a result, although I baifang my parents is logically and syntactically correct, it is semantically improper in terms of the valency framework.

In addition to logical, syntactical and semantic valency, another aspect - pragmatic valency - is put forward and discussed by some linguists. Rúzicka (1978) connects valency with communication, pointing out that the selection of complements, mainly optional complements, depends on the context of communication. In certain communicative contexts, obligatory complements can also be removed from the sentence. Helbig (1992) further probes into the connections between valency and communication. Apart from Rúzicka's idea of contextual selection of complements, Helbig includes two other factors: text style and semantic collocation. Complementation patterns are determined by various styles of texts, which, in turn, are decided by communicative purposes. For semantic collocation, it refers to the semantic valency mentioned earlier. As the headword presupposes the semantic features of its complements, when they are collocated in such a way, pragmatic errors can be avoided.

Based on German scholars' study on valency, the present study employs a similar but slightly different valency framework. As Section 3 analyzes lexical misuse committed by foreign learners of Chinese due to their misapplication of valency patterns, the analysis will be approached from three aspects of valency: logical-semantic, syntactic and semantic-pragmatic (Gao and Liu 2019). Logical-semantic valency and syntactic valency are drawn respectively from Bondzio (1978) and Helbig (1992) as mentioned earlier in this section, with the former referring to the repertoire of semantic roles assumed by the complements of a headword and the latter referring to the formal realisation of logical-semantic valency in a sentence. However, the sentence formed out of syntactic arrangement of semantic roles is sometimes incorrect in terms of other semantic and pragmatic requirements. These factors, such as semantic features (±Human, ±Elder members of the family), text styles (Literary, Explanatory), registers (Written-Formal, Spoken-Informal), emotive variables (Derogatory-Commendatory) and other contextual factors, need to be taken into account. Therefore, semantic-pragmatic valency integrates these factors to guarantee the generation of semantically and pragmatically correct sentences. In summary, the valency framework adopted by this study is illustrated in Table 1 (Gao and Liu 2019: 331):

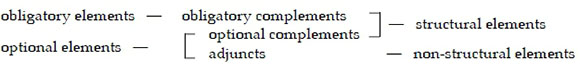

There is a pair of concepts requiring further explanation, namely complement and adjunct. Although complements and adjuncts are elements of a sentence, they have different structural status. Helbig and Schenkel (1969) have differentiated these two elements as shown below:

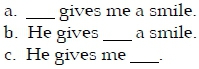

Obligatory and optional complements can be distinguished through an 'Elimi-nierungstest' (elimination test). For instance, in the sentence He gives me a smile, if all the complements are deleted one by one, only sentence b is correct:

In this case, 'He' and 'a smile' are obligatory complements while 'me' is optional.

Schumacher (1986) uses the method of an 'Implikazionsprobe' (implication) to differentiate optional complements from adjuncts. This method is based on logical-semantic valency, which gives a full list of semantic components of the governing word. Although not all the semantic components are selected in a particular sentence within a particular context, they are implied or presupposed by their governor. For example, bring (within the sense of CARRY) implies three semantic components: somebody brings something to somebody else. As a result, for the sentence He brought a dictionary to me three days ago, after all the elements are deleted one by one, sentences c and d are correct:

a. _brought a dictionary to me three days ago.

b. He brought_to me three days ago.

c. He brought a dictionary_three days ago.

d. He brought a dictionary to me_.

'To me' in sentence c is a semantic component implied by the governing word bring; whereas 'three days ago' in sentence d is not within the list of implied complements. Thus, 'to me' is an optional complement and 'three days ago' an adjunct.

The example entry of a Chinese learners' dictionary in Section 4 will be designed within the valency framework and find a practical way to treat obligatory complements, optional complements and adjuncts in the dictionary. Section 3 utilizes the valency framework established as such to analyze and discuss the lexical misuse committed by foreign learners of Chinese, the purpose of which is to prepare authentic data from learner and native speaker corpora for the construction of a Chinese valency dictionary. However, the compiling of a dictionary needs not only guidance from linguistic theory, but also lexicographical principles in order to cater to the needs of intended users. For this reason, the next section adopts the user perspective to set up the basis for its usability.

2.2 Valency dictionaries and the user perspective

Valency dictionaries have been claimed to be a useful reference tool for foreign language learning owing to its comprehensive and systematic description of lexical information. For example, Herbst et al. (2004: vii) state in the VDE that the following questions, which may baffle English learners, can be answered by consulting the dictionary: 'Is it avoid to do something or avoid doing something?', 'is try to do something the same as try doing something?', or 'Can you say the exhibition opened in English or not?'. Nevertheless, there is no empirical evidence to testify to the usability of valency dictionaries. This study also endeavours to conceive a valency dictionary for foreign learners of Chinese. This conception is, to some extent, limited in that it involves no user surveys, which may not give the intended users what they want in the dictionary. For this limitation, the present authors attempt to fulfil the minimum requirement for lexicographers as proposed by Béjoint (2002: 112): 'Lexicographers must give to the public what the public expects, or at least what they think the public expects, at the expense if necessary of what a truly scientific description of the language would require'. For this purpose, the study employs some of the key concepts of the user perspective to design the dictionary, which is constructed within the valency framework and on the basis of corpus data, for meeting the needs of the expected users. As well, in the last section, this limitation is included as a suggestion for further research into users' expectation in regard to valency dictionaries.

Hartmann (2005) summarises six user perspectives: pedagogical lexicography, dictionary awareness, user sociology, reference needs, reference skills and user training. As these perspectives are interrelated, the study discusses them from four viewpoints.

Firstly, the Chinese valency dictionary proposed in this study is pedagogical in nature. It is a tendency for modern British pedagogical dictionaries to include more information for encoding, such as syntactic patterns, collocations and registers (Béjoint 2002; Svensén 1993). This reflects an increasing need for productive activities on the part of foreign learners. While traditional learners' dictionaries need to consider the simplicity of the setup of encoding information to cater to the need of common users, which may lead to the omission of some vital information (Cowie 2002), a valency dictionary can explicitly present as much encoding information as possible by essentially focusing on helping learners with their encoding tasks. This pedagogical purpose with encoding orientation is reflected in the design of a valency entry of a Chinese valency dictionary in Figure 3, Section 4. Moreover, as argued by Fillmore (2008), valency dictionaries for foreign learners need not only descriptive representation of encoding information, but also prescriptive guidelines. In this regard, the proposed Chinese valency dictionary provides 'Note' blocks, which warn users against common lexical errors found in a learner corpus. (See examples in Section 3.4 and Figure 3 in Section 4.)

Secondly, according to Hartmann (2005), users of pedagogical dictionaries generally have a low level of awareness of dictionary contents and typology. They, especially low-level users, are more familiar with and take more interest in such information categories as meaning and spelling while neglecting those for encoding activities, such as frequency, syntactic patterns and collocations (Béjoint 2002). The low level of dictionary awareness leads to users' failure to make full use of the information, thus reducing the potential usefulness of a dictionary. Furthermore, the valency dictionary, specially designed for encoding, is relatively new in lexicographical typology, and little is known of its population of active users, as well as their knowledge, proficiency level and skill at using the dictionary. The urgent task, as expressed by some metalexico-graphers (Béjoint 2002; Cowie 2002; Hartmann 2005), is to introduce user training programs to improve user skills, which entails the joint efforts of the whole education system. For instance, user training programs need lessons and instructions from teachers, the setup of lexicographical courses by academic institutions, the inclusion of user training in the national curriculum by educational departments, the supply of easy-to-read users' guides and workbooks by publishers, and improvements in the user-friendliness of dictionaries on the part of lexicographers.

Thirdly, user sociology and needs are closely connected, as Hartmann (1989: 103) hypothesizes that 'different user groups have different needs'. Among the six aspects regarding reference needs (Hartmann 2005: 88), two are relevant to the present study: text production (semantic or syntactic problems for writers) and language acquisition. In order to investigate these needs for a better design of the Chinese valency dictionary, an intricate set of sociological variables of users - age, gender, first language background, foreign language proficiency level, educational background, habit of using dictionaries, attitude toward dictionaries, ownership, dictionary awareness, etc. - should be taken into consideration in future surveys as suggested in Section 5. For achieving as much user-friendliness as possible, the study, in its present form, attempts a short profile of prospective users, including the explanation of their proficiency level and the contexts in which they are expected to use the dictionary. (See Section 4.)

Fourthly, a good command of reference skills is the prerequisite for successful dictionary use and the ensuing satisfaction of user needs. The types of linguistic activities conducted by users determine the types of skills and strategies needed in the look-up process (Hartmann 2005, Wiegand 1998). As mentioned, the Chinese valency dictionary examined in this study aims to meet the user needs of language acquisition in general and text production in particular. It is suggested that in future empirical surveys, special attention be paid to the skills required in the consultation of information in the Chinese valency dictionary for writing activities engaged in by foreign learners of Chinese. Specifically, the survey could be implemented according to the seven essential components of the consultation process specified by Hartmann (2005: 90-92): activity problem, determining problem word, selecting dictionary, external search (macrostructure), internal search (microstructure), extracting relevant data and integrating information. Another possible way of training users' reference skills for consulting the Chinese valency dictionary is to provide relevant training exercises in the front or back matter.

This section first establishes the linguistic foundation - the valency framework - for designing a Chinese valency dictionary and then touches on the user perspective in the hope that the design and the future compilation of the dictionary could be friendly to prospective users, on the basis of which the data analysis and discussion in the next section are conducted.

3. An analysis of lexical misuse caused by misapplication of valency patterns

3.1 Research design

The present section of this study comprises three main parts. In section 3.2 misused cases of Chinese words are collected from the HSK Dynamic Compositions Corpus (hereafter HSK Corpus). In section 3.3 an analysis of the collected data is conducted along the three dimensions of the valency framework. The analysis is assisted by consulting three Chinese dictionaries and the Beijing University Corpus of Modern Chinese Language (CCL). In section 3.4 the results of the analysis, which have implications for a Chinese valency dictionary, are discussed, and then a comparison is drawn between the valency patterns of misused words and those of English equivalents in order to identify the influence of improper transfer of valency structure on lexical use, which suggests the idea of a contrastive bilingual valency dictionary.

It is necessary to make a brief introduction to HSK Corpus and CCL before the analysis unfolds. As the source of data collection, HSK Corpus is a learner corpus developed by Beijing Language and Culture University. It collected the compositions of non-native learners of Chinese who participated in HSK high-level tests from the year 1992 to 2005. Its scope now reaches 4,240,000 words and 11,569 compositions. Besides the collection of original compositions through scanning, it includes annotated materials in which interlanguage misuse is manually labelled. The annotation covers five levels of the Chinese language: Chinese characters, punctuation, words, sentences and texts. This study stays at the level of words whose annotation ranges from misused words, missing words to unnecessary words, supplemented by the statistics of various types of lexical misuse.

As the reference corpus, CCL is a native speaker corpus developed by the Center for Chinese Linguistics, Beijing University. It collects various sources of modern Chinese language such as spoken language materials from TV dialogues and interviews as well as written language materials from history, government white papers, economic reports, health and medicine, dictionaries, newspapers, films, literature, translation, essays, etc. Its scope now reaches 581,794,456 words.

3.2 Data collection

As mentioned earlier, HSK Corpus provides its users with statistical facts about interlanguage misuse at all levels. This study focuses on the lexical level, but due to the limitation of time and space, it does not attempt to examine all the types of lexical misuse committed by foreign learners of Chinese, only selecting some samples. First, Chinese words whose pinyin (Chinese pronunciation system) begins with letter Z are chosen as the level-one sample for investigation. The Z-group occupies the largest portion of Chinese words in the corpus (grouped together according to initial pinyin letters), containing 2,369 words, among which 622 are annotated as misused cases. These 622 annotated words are then selected as the level-two sample for examination. The annotation covers all types of misuse such as misspellings, missing words and unnecessary words. As well, the annotation covers all classes of words like nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, conjunctions, prepositions, etc. For a systematic and thorough inquiry into complementation patterns, the study chooses verbs as the level-three sample. We conduct a close screening of these verbs one by one in order to trace interlanguage misuse caused by improper transfer of valency patterns from English to Chinese.

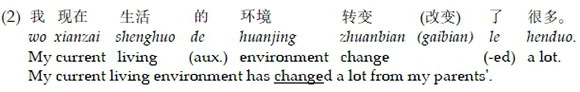

The criterion of screening is that the misused word and the correct one provided by the corpus share the same English equivalent(s). The equivalents are confirmed by consulting some Chinese dictionaries for foreign learners such as A Dictionary of Chinese Usage: 8000 Words (Chinese Proficiency Center Beijing Language and Culture University 2000) (hereafter HSK 8,000) or bilingual dictionaries for native learners such as A New Century Chinese-English Dictionary (Hui 2004). In Example 2, zhuanbian  and gaibian

and gaibian  have the same English equivalent 'change', but zhuanbian is labelled as a misused case. The reason is that although zhuanbian and gaibian can both govern such complements as 'attitudes' and 'ideas', 'living environment' is not within the governing power of zhuanbian. The meaning nuance of this pair of near-synonyms is implicitly embodied in their semantic collocations, and this implicity can be unearthed from the perspective of semantic-pragmatic valency.

have the same English equivalent 'change', but zhuanbian is labelled as a misused case. The reason is that although zhuanbian and gaibian can both govern such complements as 'attitudes' and 'ideas', 'living environment' is not within the governing power of zhuanbian. The meaning nuance of this pair of near-synonyms is implicitly embodied in their semantic collocations, and this implicity can be unearthed from the perspective of semantic-pragmatic valency.

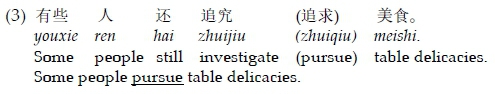

However, in Example 3, zhuijiu  find out/investigate) and zhuiqiu

find out/investigate) and zhuiqiu  pursue/go after) do not share the same English equivalent. The obvious meaning differences between this pair of lexical items do not necessarily call for a close examination within the valency framework. Thus, cases of this kind are excluded from the study.

pursue/go after) do not share the same English equivalent. The obvious meaning differences between this pair of lexical items do not necessarily call for a close examination within the valency framework. Thus, cases of this kind are excluded from the study.

Furthermore, the corpus provides all the misused cases of a word owing to its polysemous nature. Hence, the misuse of a polysemous word can be classified into one or more than one group, and each group is represented by a synonym of one of the senses of the word in question. For instance, the misuse of the word zaocheng (üffiSi, create; cause/give rise to; bring about) fall into three groups represented respectively by its synonyms chuangzao  create), chansheng

create), chansheng  cause/give rise to) and dailai

cause/give rise to) and dailai  bring about). Each group is treated as a case. Finally, after screening, there are 60 cases found in level-three samples, as displayed in Table 2:

bring about). Each group is treated as a case. Finally, after screening, there are 60 cases found in level-three samples, as displayed in Table 2:

3.3 Data analysis

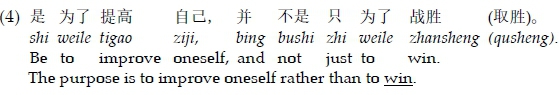

This section scrutinizes lexical misuse within the valency framework and identifies the dimension(s) - logical-semantic, syntactic or semantic-pragmatic - in which the misuse occurs. The scrutiny of lexical misuse is first conducted by consulting both native-speaker-oriented (the Contemporary Chinese Dictionary) and foreign-learner-oriented (the Commercial Press Learners' Dictionary of Contemporary Chinese; HSK 8,000) Chinese dictionaries. In Example 4, zhansheng ( win) is usually a transitive divalent verb that governs an object such as an enemy, a team or difficulty (from the Contemporary Chinese Dictionary). Therefore, it is incorrect to use zhansheng as a monovalent verb without objects; whereas qusheng

win) is usually a transitive divalent verb that governs an object such as an enemy, a team or difficulty (from the Contemporary Chinese Dictionary). Therefore, it is incorrect to use zhansheng as a monovalent verb without objects; whereas qusheng  win), an intransitive monovalent one, is appropriate. This kind of misuse involves logical-semantic valency.

win), an intransitive monovalent one, is appropriate. This kind of misuse involves logical-semantic valency.

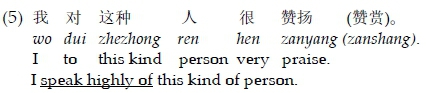

In Example 5, both zanyang  praise) and zanshang

praise) and zanshang  , praise) are divalent verbs, but only zanshang can be used in the syntactic pattern 'dui

, praise) are divalent verbs, but only zanshang can be used in the syntactic pattern 'dui  treat) + NP + hen

treat) + NP + hen  very) + VP' (from HSK 8,000). Therefore, these misused cases involve syntactic valency.

very) + VP' (from HSK 8,000). Therefore, these misused cases involve syntactic valency.

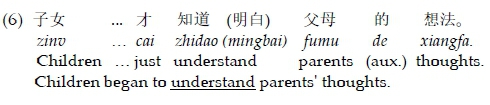

In Example 6, it is semantically correct for zhidao  know) to be collocated with 'one's thoughts' (from the Contemporary Chinese Dictionary). However, in this specific context, mingbai

know) to be collocated with 'one's thoughts' (from the Contemporary Chinese Dictionary). However, in this specific context, mingbai  , understand) is more appropriate. These cases of misuse, which are largely due to contextual factors, involve semantic-pragmatic valency.

, understand) is more appropriate. These cases of misuse, which are largely due to contextual factors, involve semantic-pragmatic valency.

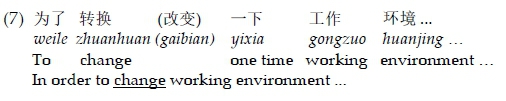

In Example 7, zhuanhuan  change) can be both a monovalent and divalent verb and its usage conforms to syntactic rules. However, its object is usually attitude, direction, topic, or pattern, not including environment which, nevertheless, can be governed by gaibian

change) can be both a monovalent and divalent verb and its usage conforms to syntactic rules. However, its object is usually attitude, direction, topic, or pattern, not including environment which, nevertheless, can be governed by gaibian  change) (from HSK 8,000). Hence, the semantic collocation is improper. These cases of misuse involve semantic-pragmatic valency.

change) (from HSK 8,000). Hence, the semantic collocation is improper. These cases of misuse involve semantic-pragmatic valency.

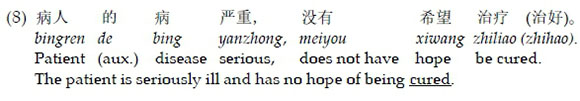

In Example 8, zhiliao  cure) is a transitive divalent verb and its semantic collocates include 'disease' (from HSK 8,000). Nevertheless, in this context, the speaker implies that the disease needs to be treated and the patient can thus recover. In this respect, zhihao

cure) is a transitive divalent verb and its semantic collocates include 'disease' (from HSK 8,000). Nevertheless, in this context, the speaker implies that the disease needs to be treated and the patient can thus recover. In this respect, zhihao  cure) is correct because it incorporates both of the semes 'to treat a patient' and 'to help a patient gain recovery'. Thus, these cases of misuse are motivated by semantic and contextual factors and fall into the dimension of semantic-pragmatic valency.

cure) is correct because it incorporates both of the semes 'to treat a patient' and 'to help a patient gain recovery'. Thus, these cases of misuse are motivated by semantic and contextual factors and fall into the dimension of semantic-pragmatic valency.

However, some analyses of lexical misuse cannot be accomplished by simply consulting dictionaries. As mentioned in the Introduction, the majority of the definitions and examples in these dictionaries do not contain full lists of complementation patterns (Xu 2012). To solve this problem, the present study turns to CCL, a large-scale native Chinese speaker corpus, by adopting the method of studying semantic prosody (a corpus-based study of the semantic environment of a given word). The approach is a combination of corpus-based and corpus-driven investigations, which involves four steps (Partington 1998; Sinclair 1991 and 1996; Wei 2002). Firstly, a number of concordance lines are randomly retrieved from the corpus. The next step is to determine the span of the node word and then establish colligation(s) (i.e. syntactic structure) by observing the collocates around the node word. Then, semantic features of these collocates are analyzed. The last step is to draw out the semantic prosodies of the key word. This approach can lend support to the analysis of valency structure. The colligations established by observing collocates help identify complementation patterns. The revelation of semantic features of collocates helps to work out a relatively full list of semes of the headword. More importantly, the conclusion of semantic prosodies helps uncover pragmatic information of the headword such as emotive variables.

In Example 9, the usage of zhaolai  , attract) cannot be found in these dictionaries. For this reason, the study opts for a corpus-based and corpus-driven method and it entails three steps.

, attract) cannot be found in these dictionaries. For this reason, the study opts for a corpus-based and corpus-driven method and it entails three steps.

Step 1: The establishment of colligations

The frequency of occurrence of the node word zhaolai in CCL is 1,444, from which we randomly select 100 concordance lines. The span is set as -7/+7, and the words within this span are collocates for observation. Our study shows that there are 5 types of colligations for the node word zhaolai:

1) NP + zhaolai + NP. This colligation is the most frequent, accounting for 83% of the total concordances.

2) zhaolai + de

structural auxiliary). The colligation accounts for 8% of the total concordances. This construction functions mostly as adjectives (7%) to modify nouns, such as zhaolai de gongren

recruited workers), zhaolai de xuesheng

, recruited students) and zhaolai de pengyou

invited friends). Only one case acts as a noun (1%), such as zhaolai de ze shi yidui fen'nu de qianze

What our action incurred was a pile of furious denunciation).

3) NP + shi

, be) + cong (A, from) + someplace + zhaolai + de

structural auxiliary). This colligation takes up 4% of the total. For example, zhanshi duoshu shi cong nongcun zhaolai de

, Most of the soldiers were conscripted from rural areas).

4) ba

used to advance the object of a verb to the position before it) + NP + zhaolai + le

, structural auxiliary). This colligation only occurs once (1%). For example, ba gongren zhaolai le

Prospective employees were recruited).

5) Idioms or fixed phrases. There are four cases of idioms centered on zhaolai (4%), such as zhaolai huiqu

, to call in and send away sb. at will) and congshi zhaolai

, admit it; make a clean breast of everything).

Step 2: Collocates and their semantic properties

The first type of colligation forms the overwhelming majority of all the concordances, and the complements of zhaolai  attract) are divided into three groups:

attract) are divided into three groups:

Group one: people (such as staff, talented human resources, soldiers, customers and readers) and vehicles. The colligations with this group of complements occupy 31% of all the concordances.

Group two: negative comments, emotions and attitudes (such as condemnation, reproach, indifference, sarcasm, quarrel, catcall, dissatisfaction, criticism and rude language) as well as unfavourable things (such as disaster, trouble, punishment, ill consequence and mosquito). The frequency of this group of complements is higher than that of group one, reaching 46%.

Group three: resisting power (such as opponent, counter-attack and resistance).

The colligations with this group of complements take up only 6%.

The complements in the second type of colligation, which account for 8%, are divided into two groups:

Group one: people (such as personnel, talented human resources, soldiers and friends). The colligations with this group of complements take up 7%.

Group two: negative comments (such as quarrel). The colligation represented by this group occurs once (1%).

The complements in the third type of colligation, which account for 4% of concordances, fall into one group, that is, people such as workers, child labourers and soldiers.

For the fourth type of colligation, which accounts for 1% of concordances, the complement of the governing word zhaolai is employees.

The fifth type of colligation (4%) has no explicit complements.

The semantic features of the complements in those colligations can be summarized as follows. The governing verb zhaolai presupposes three classes of complements whose respective semantic components are: people; negative comments, emotions, attitudes, unfavourable things; and resisting power.

Step 3: Prosodic structure

Based on the above observations concerning the semantic features of complements, the prosodic structure of zhaolai  attract) is summarized in Table 3:

attract) is summarized in Table 3:

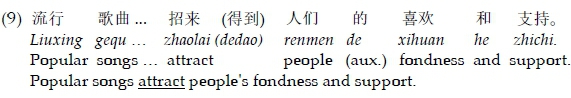

It can be seen from the table that zhaolai is not surrounded by a positive semantic environment but by the nearly even configuration of negative and neutral prosodies. Apart from the groups of 'fixed phrases' and 'resisting power', when zhaolai is collocated with "people", it carries a neutral prosody, and when collocated with the group of complements - negative comments, emotions and attitudes - it carries a negative prosody. When it comes to Example 9 where zhaolai collocates with two positive emotive and attitudinal words xihuan  fondness) and zhichi

fondness) and zhichi  support), the foreign learner obviously misuses the word in terms of semantic-pragmatic valency.

support), the foreign learner obviously misuses the word in terms of semantic-pragmatic valency.

With the joint assistance of dictionaries and corpora, the 60 cases of lexical misuse listed in Table 2 are examined and the misuse of valency are identified. The results are summarized in Tables 4, 5 and 6 (due to the limitation of space, examples from the HSK Corpus are not provided):

3.4 Discussion

In this section the results of the above analysis which have implications for the information structure of a Chinese valency dictionary are firstly discussed. It then compares the valency patterns of misused words with those of English equivalents in order to trace the influence of negative transfer of valency structure on lexical use, which may shed light on the construction of a contras-tive bilingual valency dictionary.

From Tables 4, 5 and 6, it can be seen that the majority of cases of misuse occur in the dimension of semantic-pragmatic valency, taking up 85%. 11.7% of vocabulary misuse cases occur in the dimension of syntactic valency and only 3.3% in the dimension of logical-semantic valency. As argued by Han (1993), logical-semantic valency of a certain concept in different languages is generally the same because of people's shared experience. That is, the semantic roles of complements presupposed by the governing verb in different languages are nearly the same, or the governing verb has the same valency number in different languages. Thus, it is easy to explain that there are only two cases of misuse involving logical-semantic valency.

Different languages have different grammatical or syntactic systems. For example, Chinese words lack inflections and derivations and the word order is relatively flexible, which is in stark contrast to English vocabulary. Consequently, there might be distinct differences between Chinese and English syntax. However, as the study shows, there are only seven cases of vocabulary misuse caused by improper application of syntactic patterns. One possible reason is that the language proficiency of these foreign learners who took part in HSK tests was not that high, so that they tended to use less complicated sentence structure. Another possible reason is that the study does not examine special constructions organized by structural auxiliaries such as ba  used to advance the object of a verb to the position before it), bei

used to advance the object of a verb to the position before it), bei  used in the passive voice to introduce the doer of the action), shi

used in the passive voice to introduce the doer of the action), shi  , make/cause/have), you ... you ...

, make/cause/have), you ... you ...  expressing the coexistence of several conditions or qualities), etc.

expressing the coexistence of several conditions or qualities), etc.

The bulk of the cases of misuse occurs in the semantic-pragmatic dimension. This type of misuse manifests a great diversity and can be attributed to the factors listed in Table 1 (The valency framework). Table 6 shows that most cases of semantic-pragmatic misuse can be ascribed to semantic collocation. Semantically, some headwords cannot govern particular complements. For instance, zaodao  encounter) cannot be collocated with 'troubles or difficulties', zhiliao (tnJTf, cure) cannot govern 'problems', and the object of zhuangman

encounter) cannot be collocated with 'troubles or difficulties', zhiliao (tnJTf, cure) cannot govern 'problems', and the object of zhuangman  be filled with) should not be 'smell of cigarettes'.

be filled with) should not be 'smell of cigarettes'.

Another leading factor is context, which gives rise to a number of cases of misuse. Some words, without contextual restrictions, can be in collocation with a range of words. However, in a particular context, the range of collocation is restricted. For example, in a general context, it is appropriate to say Please zhuyi _ pay attention to) the pains of patients. Nonetheless, in the sentence I hope people from all walks of life can pay attention to the pains of patients, the word guanzhu ( , pay attention to) is more appropriate. Moreover, generally the expression zhankai

, pay attention to) is more appropriate. Moreover, generally the expression zhankai  spread) arms makes sense; but in the situation of helping children to walk with one's hands, the sentence My father zhankai his arms to support me to walk is awkward in the light of common sense.

spread) arms makes sense; but in the situation of helping children to walk with one's hands, the sentence My father zhankai his arms to support me to walk is awkward in the light of common sense.

The third semantic-pragmatic factor is emotive variables. The semantic environment around the headword decides its collocation with its complements. For example, zizhang  , develop) tends to govern complements with derogatory sense - 'malpractice, bad habit, arrogance or crimes', but not those with positive sense.

, develop) tends to govern complements with derogatory sense - 'malpractice, bad habit, arrogance or crimes', but not those with positive sense.

As for register or formality of words, there are two cases of misuse. For instance, zhixi  know) is a word with high degree of formality and it cannot be used in informal writing.

know) is a word with high degree of formality and it cannot be used in informal writing.

The last factor is text style, with only one case of misuse. zhu ({i, stay) is usually a word that is adopted in literary writing like poems. Therefore, it is stylistically improper to use this word in the sentence His love zhu at my heart in daily conversation.

In short, lexical misuse committed by foreign learners of Chinese can be analyzed from all three dimensions of the valency framework, with semantic-pragmatic errors being the most frequent. These results can be re-organized to be published as dictionary information. Specifically, the data gained from the native speaker corpus (CCL) can be presented as the basic information of a valency dictionary: quantitative valency, qualitative valency and valency patterns (Helbig and Schenkel 1969; Herbst et al. 2004). This treatment will be described and processed in detail in Figure 3, Section 4. The data gained from the learner corpus (HSK Corpus) can be arranged as tips or notes at the end of an entry so as to enhance learners' awareness of common lexical errors. This 'Note' block can be introduced by labels such as 'logical-semantic error', 'syntactic error' and 'semantic-pragmatic error'. For instance,

The possible causes for these cases of misuse are further discussed in the rest of this section by comparing the valency patterns of two misused words with those of English equivalents, which may help trace the influence of improper transfer of valency structure on lexical use. As noted, most contrastive valency studies are conducted among Indo-European languages such as German-English (Emons 2006, Mittmann 2007, Roe 2007), German-French (Plewnia 2006),

German-Italian (Bianco 2006), German-Spanish (Fandrych 2006), German-Russian (Nübler 2006), German-Bulgarian (Baschewa 2006), German-Romanian (Stänescu 2006) and German-Polish (Schatte 2006). This study contributes to the few contrastive studies between Indo-European and Sino-Tibetan languages.

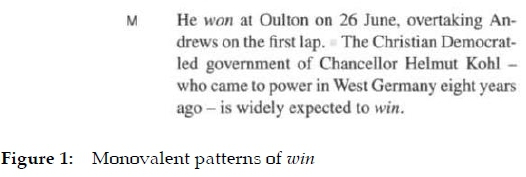

In Example 4, the English equivalent of the misused word zhansheng  is 'win'. According to the Valency Dictionary of English (Herbst et al. 2004: 948), the maximum number of valency complements of the headword is four and the minimum number is one, which means that 'win' can be used as an intransitive verb. From Figure 1, the monovalent verb 'win' has two complementation patterns: NP + win and NP + be (expected, etc.) to + win:

is 'win'. According to the Valency Dictionary of English (Herbst et al. 2004: 948), the maximum number of valency complements of the headword is four and the minimum number is one, which means that 'win' can be used as an intransitive verb. From Figure 1, the monovalent verb 'win' has two complementation patterns: NP + win and NP + be (expected, etc.) to + win:

When composing a Chinese sentence which expresses the meaning - 'The purpose is to improve oneself rather than to win', the student may resort to his/her bilingual mental lexicon and retrieve the word zhansheng from his/her knowledge about Chinese. In the meantime, his/her inherent knowledge of the English word win is activated. Following the wrong association of the divalent Chinese verb zhansheng and the monovalent pattern of the English verb win, lexical misuse may occur.

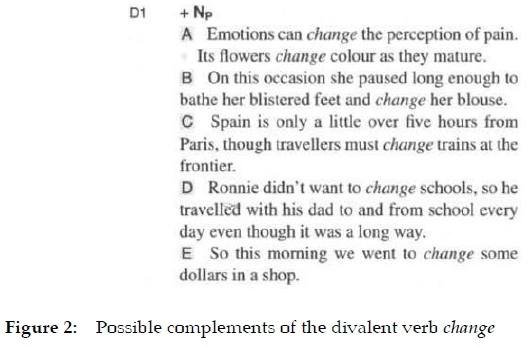

In Example 7, the English equivalent of the misused word zhuanhuan is 'change'. According to VDE (Herbst et al. 2004: 122), this headword can govern at most four complements. From Figure 2, it can be seen that one possible object of divalent change is 'school', which indicates a particular environment or location:

In order to express 'to change my working environment' in Chinese, the examinee retrieves the word zhuanhuan and activates his/her knowledge about the semantic properties of change. The juxtaposition of zhuanhuan (whose list of objects excludes 'environment') and the semantic properties of change (which empower the verb change to govern the object 'environment') may result in a pragmatic failure.

The above discussion shows that through the analytic lenses of the valency framework, the influence of improper transfer of the valency structure from one language to another can be revealed. This inspires the idea of a bilingual Chinese-English dictionary that introduces the differences and similarities between Chinese and English lexical items in different aspects. This idea is briefly represented in Table 7 and may be worthy of further research, which needs larger corpus data support.

4. A valency dictionary for foreign learners of the Chinese language

With the analysis in Section 3, different levels of lexical misuse emerge from the data. The question arises: how to help foreign learners of Chinese to avoid making such mistakes. The answer may partly lie in a valency dictionary that systematically provides syntactic-semantic-pragmatic information of words, which might enhance learners' language proficiency. This section first introduces the basic elements of a Chinese valency dictionary for foreign learners and then designs one valency entry with a brief profile of prospective users.

Similar to German and English valency dictionaries, the Chinese valency dictionary has three basic elements: quantitative valency, qualitative valency and valency patterns.

Quantitative valency relates to the 'number of complements required for the verb to occur in an acceptable sentence' (Herbst et al. 2004: x). The complement inventory incorporates both obligatory and optional complements. Another quantitative feature of the dictionary is that it introduces the concept of 'probabilistic valency' (Herbst et al. 2004; Liu 2009). Labels, such as rare, freq. and very freq., are used to indicate the frequency of valency patterns based on the CCL corpus.

Qualitative valency describes the characteristics of complements. Both obligatory and optional complements' semantic roles and properties are elaborated. Optional complements are placed in parentheses '( )' to be distinguished from obligatory complements. Furthermore, a 'Note' block is provided at the end of the entry to warn learners against the common valency errors that might be committed in encoding tasks.

Valency patterns specify the syntactic structure of the governing word and its complements. Patterns are displayed in the form of combinations of phrases or clauses, such as NP + ~ + NP, substantiated by concrete examples. Furthermore, those adjuncts that can help exemplify a complete sentence structure are also included and placed in angle brackets '< >'.

Taking zhaolai  from Example 9 as the entry word, these three elements of a valency dictionary are organized as follows:

from Example 9 as the entry word, these three elements of a valency dictionary are organized as follows:

It should be noted that this design of a valency entry is an example based on the results of data analysis in Section 3. While the data analyzed is a limited range of sample concordance lines retrieved from the corpora, it cannot exhaust all the possible valency patterns. This Chinese valency dictionary in a bilingualized form is mainly intended for advanced foreign learners of the Chinese language. The dictionary can be used in the setting of classroom teaching and learning or in self-study. It is expected that learners use the dictionary to retrieve relevant information to write in a correct and idiomatic manner. It is also expected that learners read the 'Instructions to Users' and finish corresponding exercises in the front matter for the sake of efficient and effective use of the dictionary.

5. Conclusion

Lexical misuse occurs on different levels in foreign language acquisition and can be analyzed in terms of the three dimensions of the valency framework - logical-semantic, syntactic and semantic-pragmatic. Following the analysis, this study found that 85% of the cases of misuse involve semantic-pragmatic valency, 11.7% involve syntactic valency and only 3.3% involve logical-semantic valency. In addition, there are diverse factors responsible for lexical misuse in the semantic-pragmatic dimension, among which semantic collocation and contextual factors are most influential. Other pragmatic factors include emotive variables, text styles and registers. These cases of lexical misuse and analytical results discovered from authentic corpus material are largely lacking in treatment in popular Chinese learners' dictionaries, and thus need to be properly represented and foregrounded in CLDs. The study hence designed a valency entry that includes all these information types to aid foreign learners' acquisition of Chinese words.

There are four suggestions for further research on valency dictionaries and Chinese vocabulary learning. Firstly and primarily, in addition to verbs, it might be important to study the valency of other lexical classes such as nouns, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, numerals and quantifiers so that the Chinese valency dictionary can provide comprehensive information concerning all classes of Chinese vocabulary. Secondly, pragmatic valency still has room for further studies. Most of previous valency studies focus on syntactic and semantic aspects. Although the present study found that various factors contribute to lexical misuse in semantic-pragmatic valency, they are not scrutinized completely and thoroughly and there might be other unknown pragmatic factors. Thirdly, as suggested in Section 3.4, the research project of a contrastive Chinese-English valency dictionary could be promoted to help learners discern lexical errors caused by interlingual transfer of valency structure. Finally, it is suggested that empirical studies be conducted to verify the usability of Chinese valency dictionaries. The feedback from user surveys may help improve the design and compilation of Chinese valency dictionaries.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to two anonymous reviewers and the editor of Lexikos for their valuable suggestions and comments. The current research was funded by the Zhejiang Provincial Planning Project of Philosophy and Social Sciences (No. 17NDJC224YB) and the New Key Professional Think Tank of Zhejiang Province - the Zhejiang Gongshang University Cultural Industry Think Tank.

References

Ágel, V. et al. (Eds.). 2006. Dependenz und Valenz: ein internationales Handbuch der zeitgenössischen Forschung. Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Bareggi, C. 1989. Gi Studenti e il Dizionario: Un'inchiesta presso gli Studenti di Inglese del Corso di Laurea in Lingue e Letterature Straniere Moderne della Facolta di Lettere di Torino. Prat Zagrebelsky, M.T. et al. (Eds.). 1989. Dal Dizionario ai Dizionari. Orientamento e Guida all'uso per Studenti di Lingua Inglese: 155-179. Torino: Tirrenia Stampatori. [ Links ]

Baschewa, E. 2006. Kontrastive Fallstudie: Deutsch-Bulgarisch. Ágel, V. et al. (Eds.). 2006: 1229-1233.

Béjoint, H. 2002. Modern Lexicography: An Introduction. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. [ Links ]

Bianco, M.T. 2006. Kontrastive Fallstudie: Deutsch-Italienisch. Ágel, V. et al. (Eds.). 2006: 1187-1196.

Bondzio, W. 1978. Abriß der semantischen Valenztheorie als Grundlage der Syntax. III. Teil. Zeit-schrift für Phonetik, Sprachwissenschaft und Kommunikationsforschung 31(1): 21-33. [ Links ]

Chinese Proficiency Center Beijing Language and Culture University (Ed.). 2000. A Dictionary of Chinese Usage: 8000 Words. Beijing: Beijing Language and Culture University Press. [ Links ]

Cowie, A.P. 2002. English Dictionaries for Foreign Learners: A History. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. [ Links ]

De Groot, A.W.D. 1949. Structurele Syntaxis. Den Haag: Servire. [ Links ]

Emons, R. 2006. Contrastive Case Study: Predicates in English and German. Ágel, V. et al. (Eds.). 2006: 1170-1176.

Fandrych, C. 2006. Kontrastive Fallstudie: Deutsch-Spanisch. Ágel, V. et al. (Eds.). 2006: 1197-1206.

Fillmore, C.J. 2008. A Valency Dictionary of English. International Journal of Lexicography 22(1): 55-85. [ Links ]

Gao, J. and H.T. Liu. 2019. Valency and English Learners' Thesauri. International Journal of Lexicography 32(3): 326-361. [ Links ]

Han, W.H. 1993. Basic Concepts and Research Methods of Valency Theory. Journal of Tianjin Foreign Studies University First Issue: 22-32.

Han, W.H. 1997. Views and Differences Concerning the Essential Issues from the Main Schools of German Valency Theory. Linguistics Abroad 3: 12-20, 31. [ Links ]

Han, W.H. and Y.X. Han. 1995a. The Theoretical Basis and Compilation Program of A Contrastive German-Chinese Valency Dictionary of Verbs. Journal of Tianjin Foreign Studies University 1: 12-20. [ Links ]

Han, W.H. and Y.X. Han. 1995b. A Sequel to the Theoretical Basis and Compilation Program of a Contrastive German-Chinese Valency Dictionary of Verbs. Journal of Tianjin Foreign Studies University 2: 17-27. [ Links ]

Hartmann, R.R.K. 1989. Sociology of the Dictionary User: Hypotheses and Empirical Studies. Hausmann, F.J. et al. (Eds.). 1989. Wörterbücher. Ein internationales Handbuch zur Lexikographie/ Dictionaries. An International Encyclopedia of Lexicography /Dictionnaires. Encyclopédie internationale de lexicographie. Volume I: 102-111. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Hartmann, R.R.K. 2005. Teaching and Researching Lexicography. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. [ Links ]

Helbig, G. 1992. Probleme der Valenz-und Kasustheorie. Tubingen: Niemeyer. [ Links ]

Helbig, G. and W. Schenkel (Eds.). 1969. Wörterbuch zur Valenz und Distribution deutscher Verben. Leipzig: VEB Bibliographisches Institut. [ Links ]

Herbst, T. and K. Götz-Votteler. 2007. Valency: Theoretical, Descriptive and Cognitive Issues (Trends in Linguistics Studies and Monographs 187). Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Herbst, T., D. Heath, I.F. Roe and D. Götz (Eds.). 2004. A Valency Dictionary of English: A Corpus-Based Analysis of the Complementation Patterns of English Verbs, Nouns and Adjectives. Berlin/ New York: Mouton de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Hui, Y. (Ed.). 2004. A New Century Chinese-English Dictionary. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. [ Links ]

Kacnel'son, S.D. 1948. O Grammaticeskio Kategorii. Vestnik Lenningradskogo Universiteta, Serija Istorii, Jazyka i Literatury 2: 114-134. [ Links ]

Kacnel'son, S.D. 1988. Zum Verständnis von Typen der Valenz. Sprachwissenschaft 13: 1-30. [ Links ]

Liu, H.T. 2009. Dependency Grammar: From Theory to Practice. Beijing: Science Press. [ Links ]

Lu, J.M. 1997. Valency Grammatical Theory and Teaching Chinese as a Second Language. Chinese Teaching in the World 1: 3-13. [ Links ]

Lu, J.J. and W.H. Lv (Eds.). 2007. Commercial Press Learners' Dictionary of Contemporary Chinese. Beijing: The Commercial Press. [ Links ]

Lyons, J. 2000. Linguistic Semantics: An Introduction. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. [ Links ]

Mei, X.J. 2003. Valency Grammar and the Compilation of Modern Chinese Learners' Dictionaries. Lexicographical Studies 5: 39-46. [ Links ]

Mittmann, B. 2007. Contrasting Valency in English and German. Herbst, T. and K. Götz-Votteler (Eds.). 2007: 271-286.

Neubach, A. and A.D. Cohen. 1988. Processing Strategies and Problems Encountered in the Use of Dictionaries. Dictionaries 10: 1-19. [ Links ]

Nübler, N. 2006. Kontrastive Fallstudie: Deutsch-Russisch. Ágel, V. et al. (Eds.). 2006: 1207-1213.

Partington, A. 1998. Patterns and Meanings. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Plewnia, A. 2006. Kontrastive Fallstudie: Deutsch-Französisch. Ágel, V. et al. (Eds.). 2006: 1177-1186.

Roe, I. 2007. Valency and the Errors of Learners of English and German. Herbst, T. and K. Götz-Votteler (Eds.). 2007: 217-228.

Rúzicka, R. 1978. Three Aspects of Valence. Abraham, W. (Ed.). 1978. Valence, Semantic Case, and Grammatical Relations: 47-54. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Schatte, C. 2006. Kontrastive Fallstudie: Deutsch-Polnisch. Ágel, V. et al. (Eds.). 2006: 1214-1216.

Schumacher, H. (Ed.). 1986. Verben in Feldern, Valenzwörterbuch zur Syntax and Semantik deutscher Verben. Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Shao, J. 2002. Valency Theory and Lexical Teaching of Chinese as a Foreign Language. Language Teaching and Linguistic Studies 1: 43-49. [ Links ]

Shen, Y. 2000. Valency Theory and Studies on Chinese Grammar. Beijing: Language and Culture University Press. [ Links ]

Shen, Y. and D.O. Zhen (Eds.). 1995. Studies on Valency Grammar of Modern Chinese. Beijing: Beijing University Press. [ Links ]

Sinclair, J. 1991. Corpus, Concordance, Collocation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Sinclair, J. 1996. The Search for Units of Meaning. Textus 9(1): 75-106. [ Links ]

Sommerfeldt, K.-E. and H. Schreiber (Eds.). 1974. Wörterbuch zur Valenz und Distribution deutscher Adjektive. Leipzig: VEB Bibliographisches Institut. [ Links ]

Sommerfeldt, K.-E. and H. Schreiber (Eds.). 1977. Wörterbuch zur Valenz und Distribution der Substantive. Leipzig: VEB Bibliographisches Institut. [ Links ]

Stänescu, S. 2006. Kontrastive Fallstudie: Deutsch-Rumänisch. Ágel, V. et al. (Eds.). 2006: 1234-1243.

Sun, D.J. (Ed.). 2006. A Study on Teaching Chinese Vocabulary as a Foreign Language. Beijing: The Commercial Press. [ Links ]

Svensén, B. 1993. Practical Lexicography: Principles and Methods of Dictionary-making. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Tesnière, L. 1959. Elements de Syntaxe Structurale. Paris: Klincksieck. [ Links ]

Wei, N.X. 2002. General Approaches to Studying Semantic Prosody. Foreign Language Teaching and Research 34 (4): 300-307. [ Links ]

Wiegand, H.E. (Ed.). 1998. Perspektiven der pädagogischen Lexikographie des Deutschen. Untersuchungen anhand von Langenscheidts Großwörterbuch Deutsch als Fremdsprache. Tübingen: Max Nie-meyer. [ Links ]

Wu, W.Z. 1996. A Review of Studies on Chinese Verb Valency. Journal of Sanming University 2: 1-11. [ Links ]

Xie, H.J., X.Y. Zheng and L.P. Zhang. 2015. An Investigation of and Study on Chinese Dictionaries for Foreign Learners. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. [ Links ]

Xu, X.H. 2012. Lexicographical Definitions and Exemplifications of Bivalent Nouns. Lexicographical Studies 4: 32-37. [ Links ]

Yuan, Y.L. 2010. A Study on Chinese Valency Grammar. Beijing: The Commercial Press. [ Links ]

Zhan, W.D. 2000. Valency-Based Chinese Semantic Dictionary. Applied Linguistics 1: 37-43. [ Links ]

Zhang, S.J. 2007. The Construction of Synonym Discrimination Information in Foreign-oriented Chinese Learners' Dictionary. Foreign Language Research 3: 94-97. [ Links ]

Zhang, Y.H. 2011. Studies on Lexicographic Definitions for Foreign-oriented Chinese Learners' Dictionaries. Beijing: The Commercial Press. [ Links ]

Zhou, G.G. 2011. A Study on Valency Grammar of Contemporary Chinese. Beijing: Higher Education Press. [ Links ]