Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Lexikos

versão On-line ISSN 2224-0039

versão impressa ISSN 1684-4904

Lexikos vol.29 Stellenbosch 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.5788/29-1-1520

ARTICLES

Lexicographical Contextualization and Personalization: A New Perspective

Leksikografiese kontekstualisering en verpersoonliking: 'n Nuwe perspektief

Sven TarpI; Rufus GouwsII

IDepartment of Afrikaans and Dutch, Stellenbosch University, South Africa; Centre for Lexicographical Studies, Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, China; International Centre for Lexicography, Universidad de Valladolid, Spain; and Centre for Lexicography, University of Aarhus, Denmark (st@cc.au.dk)

IIDepartment of Afrikaans and Dutch, Stellenbosch University, South Africa (rhg@sun.ac.za)

ABSTRACT

Contextualization, i.e. to provide solutions to users' information needs directly in the situation or context where these needs occur, played a significant role in the work of the Greek scribes who inserted glosses into manuscript copies of the works of Homer and other earlier writers in order to explain obsolete and unusual words. After the invention of the glossary, a schism developed within lexicography. On the one hand, there was the new compilation of glossaries and dictionaries of a still more complex and sophisticated nature. On the other hand, there was the traditional insertion of glosses into manuscript copies of books from previous periods. Although the advent of dictionaries diminished the use of contextualization procedures they were still adhered to in some publications. This paper discusses the occurrence of contextualization and personalization procedures in different eras and environments and it is shown how these procedures also introduced a lexicographic practice to some extra-dictionary environments. The importance of contextualization and personalization in modern-day lexicography is stressed. Lexicographers often have had unfulfilled dreams of new possibilities within the digital environment. However, the lack of adequate technology has made their dreams impossible - at that stage. Today new technologies and collaboration between lexicography and information science offer numerous new challenges that can be met by lexicographers. It is shown how lexicographical products being integrated into information tools little by little are closing the more than two thousand year old schism in European lexicography, i.e. reuniting contextualization and personalization. Lexicographers, the modern-day scribes, have to endeavour to make the seemingly impossible possible.

Keywords: contextualization, e-reader, extra-dictionary, gloss, glossary, information science, information tools, personalization, scribes, writing assistant

OPSOMMING

Kontekstualisering, dit is om oplossings vir gebruikers se inligtingsbehoef-tes te verskaf presies in die situasie en konteks waar die behoefte ontstaan, het 'n belangrike rol gespeel in die werk van die Griekse skribas wat glosse in die manuskripte van kopieë van Homeros en ander vroeë skrywers gevoeg het om onbekende en ongewone woorde te verduidelik. Na die ont-wikkeling van die glossarium het 'n kloof binne leksikografie ontstaan. Enersyds was daar die samestelling van glossaria en woordeboeke van 'n nog meer gesofistikeerde aard. Andersyds was daar die tradisionele invoeging van glosse in ouer manuskripte. Alhoewel die koms van woordeboeke die gebruik van kontekstualisering verminder het, is dié werkswyse steeds in sommige publikasies gebruik. Hierdie artikel bespreek die voorkoms van kontekstualisering en verpersoonliking in verskillende eras en omgewings en daar word aangetoon hoe hierdie werkswyses 'n leksikografiese aard in sommige buite-woordeboekomgewings ingelui het. Die belang van kontekstualisering enverpersoonliking in die moderne leksikografie word benadruk. Leksikograwe het dikwels onver-vulde drome gehad van nuwe moontlikhede in die digitale omgewing. Die tekort aan toereikende teg-nologie het hulle drome in daardie stadium 'n onmoontlikheid gemaak. Vandag bied nuwe tegnologie en samewerking tussen leksikografie en inligtingswetenskap talle uitdagings wat leksikograwe kan oorkom. Dit word aangetoon hoe leksikografiese produkte in inligtingswerktuie geïntegreer word en geleidelik word die kloof wat reeds meer as tweeduisend jaar in die Europese leksikografie bestaan, oorbrug deur 'n hereniging van kontekstualisering en verpersoonliking. Leksikograwe, die moderne skribas, moet poog om die oënskynlik onmoontlike moontlik te maak.

Sleutelwoorde: buite-woordeboek, e-leser, glos, glossarium, inligtings-werktuie, inligtingswetenskap, kontekstualisering, skribas, skryfhulp, verpersoonliking

0. Introduction

History is a funny thing. It develops through bumps and jumps, most of the time forwards but frequently also backwards. Sometimes it even tends to repeat itself, in most cases as a tragedy. Other times specific phenomena appear in a specific historical period without us humans paying much or any attention to them for years or even centuries. The phenomena seem to be of little relevance and are therefore left to an anonymous existence until they, in one of those tricky turnabouts in history, suddenly are brought into the limelight although they, as phenomena, are much older than those who promote them as new and revolutionary. The concepts of contextualization and personalization within lexicography are symptomatic of phenomena that have shared such a destiny.

In a lexicographical - and information science - perspective contextuali-zation means, in addition to its traditional linguistic sense, to provide solutions to users' information needs directly in the situation or context where these needs occur. The modern GPS is an example of such a contextualized service. When a person is driving and has to turn right in order to continue to the fixed destination, the GPS voice gives the instruction to turn right say 100 m before reaching the crossroad. Another driver on their way to the same destination who is 200 m behind the first driver will not get this instruction until a few seconds later. The GPS instructions are contextualized because they are delivered in the exact moment and place where they are needed.

Personalization is somehow related to contextualization but nonetheless different in nature. It means that the provider of information in one way or another knows when a particular user has or is expected to have an information need and also how to prepare the corresponding lexicographical data and adapt them to the user's particular profile so he or she can effectively make use of them in order to meet his or her particular need. It is a matter of course that personalization does not exclude that the needs of different users with more or less the same profile can be met by the same set of lexicographical data. It just means that the data in terms of language, formality, content and design should be prepared and presented in such a way that users can solve their particular problems as smoothly as possible.

In the following article, we will show how contextualization and personalization entered into lexicography more than two thousand years ago and developed over time. We will also discuss how these two interrelated phenomena were separated, especially after the introduction of the printing technology, and almost completely ignored in the academic literature until their recent "resurrection" as a result of the new digital technologies.

1. Where it all began - at least in Europe

Four decades ago, the Egyptian scholar Al-Kasimi (1977: 1) observed that the "major motives behind the rise of lexicography differ from one culture to another" and that each culture therefore develops "dictionaries appropriate to its characteristic demands". In this perspective, and based on a study by Stathi (2006), Hanks (2013: 507) traces the origin of European lexicography back to the Classical Greek Period where "it was customary for Greek scribes to insert glosses into manuscript copies of the works of Homer and other earlier writers" in order to explain "obsolete and unusual words". In contrast to the difficulty experienced by their predecessors in the Middle East who worked on clay tablets, the introduction of pen and parchment made it easy for the Greek scribes to perform this task with a certain elegance. Hanks explains how the glosses, from the third century BC onwards, were "compiled into separate glossaries by scholars at the library in Alexandria" thus giving birth to the dictionary form, as we have known it since then. Historians of lexicography see "the origin of the 'dictionary' proper in this cavalier yet practical way of adding snippets to copied texts" (McArthur 1986: 76).

As it is customary in the mainstream British lexicographical tradition, Hanks (2013) then focusses on some highly relevant linguistic phenomena which he convincingly develops throughout his article. However, if one changes the focus and takes an overall historical approach, another extremely interesting phenomenon will materialize.

Readers of old texts obviously had information needs when they ran into unfamiliar words. These information needs were neither general nor abstract but very much concrete and directly related to both a specific activity (reading) and a specific place (page, line, position) in the text. When the scribes inserted glosses into manuscript copies of the classical works, they did it in the specific context where the information need first occurred. These glosses, or proto-lexicographical data, were therefore by definition, and from the very beginning, contextualized data.

Manuscript books were valuable and only few people could afford to have their own personal copies. This suggests that the majority of literate people who, for their part, only made up a tiny minority of the total population, would have to go to public places (the birth of libraries) in order to read, study and enjoy the works of Homer and other writers. The scribes, who worked at such places and were highly respected, may therefore have known at least some of these readers personally and observed their problems when encountering words that were "obsolete and unusual", maybe even discussing it with them. In this respect, the glosses inserted into the manuscript copies also represented a personalized service based on personal acquaintance or even relationship between scribes (proto-lexicographers) and readers (proto-lexicographical users).

Thus, it transpires that European dictionary making was born out of a tradition where the Greek scribes provided personalized and contextualized data to readers whom they knew had (or whom they expected to have) comprehension problems, and therefore also information needs, when reading the works from a previous period.

This interesting, user-friendly and admirable phenomenon began to partially disintegrate only two centuries later when the scholars at the library in Alexandria started compiling separate glossaries. This new invention should not be underestimated as it gave birth to a completely new and successful cultural practice, the making of dictionaries, which has survived for more than two thousand years and satisfied the needs of hundreds of millions of people. However, although being a very practical and useful invention, the glossaries also had a less desirable secondary effect. It meant that the satisfaction of information needs occurring in a specific context was decontextualized and externalized to a different information source. This may be a small problem when the glossary is adapted to a specific book and structured according to the consecutive appearances of the possible problems giving rise to information needs. In most dictionaries, this is not the case. Their macrostructures are organized alphabetically, systematically, or according to other principles that break any direct connection to a specific problem in a specific text. The introduction of separate reference works therefore created a new distance between the occurrence of an information need and its lexicographical solution. This distance grew bigger over time. It also extended the consultation time, complicated the consultation process and increased the risk of not finding an appropriate solution. In this way, the use of contextualized data was abandoned by the branch of lexicography dedicated to dictionary making.

2. Looking back with new eyes

After the invention of the glossary, a schism developed within lexicography. On the one hand, there was the new compilation of glossaries and dictionaries of a still more complex and sophisticated nature. On the other hand, there was the traditional insertion of glosses into manuscript copies of books from previous periods. This situation lasted for almost two thousand years. It continued through the Roman Imperial Period and the three European Middle Ages until the fortunate advent of the printing press in the 15th century. The scribes' beautiful profession died out soon after the introduction of this disruptive technology. And so did the last remains of lexicographical contextualization, at least for the time being.

However, although contextualization was completely abandoned by the compilers of dictionaries, personalization continued to express itself in different ways. In the beginning, the technological and societal conditions for the printed dictionary were still limited. The editions were small and most lexicographers had a fairly good knowledge of their relatively small group of customers and their needs.

Captains, who themselves had experienced communication problems when arriving in foreign seaports, compiled bilingual and multilingual dictionaries to be used by members of their crews as well as fellow captains and seamen. Priests, who had observed learners' problems when studying the Bible, authored special dictionaries explaining difficult words and expressions. Many missionaries in the colonial countries were the first authors of bilingual dictionaries between their own mother tongue and the indigenous languages. Malachy Postlethwayt, the author of The Universal Dictionary of Trade and Commerce (1774), had a very clear idea of the needs of his future users, many of which he knew personally. For a detailed discussion of this dictionary, see Tarp and Bothma (2013). The same applies to Samuel Johnson and other well-known and unknown lexicographers from that period.

Even today, you can find many authors who started their lexicographical career on their own initiative after observing unfulfilled user needs, typically within specialized subject fields and small user segments. Most writers of the Scandinavian emigrant's dictionaries, a variant of learner's dictionaries discussed by Pálfi and Tarp (2009), are either emigrants themselves or language teachers who have a very profound knowledge of the problems related to the learning of a new language. The authors are not trained lexicographers but dedicated people who want to assist the emigrants. Their works are seldom a commercial success as they are mostly printed in small editions by small publishing houses dedicated to language didactics.

The situation in terms of the big general dictionaries is different. From the 19th century onwards, a phenomenon that could be described as lexicographical alienation began to spread. The editions became bigger and bigger as a result of the growing societal demands and the continuous development of the printing technology. The dictionaries reached out to many more users with different profiles. The negative consequence of this massification was that users were decontextualized from the specific situation (reading, writing, learning) where their information needs occurred. Instead, they are treated as abstract individuals with abstract needs without paying much attention to their specific needs in different situations. To a large extent, the production of dictionaries became business as usual, although there were beautiful exceptions. In some cases, dictionary projects do not even take their point of departure in detected user needs, but in the aspirations of certain families or companies who want to show that they too are knowledgeable and can produce such highly regarded works.

The result of all this was a still larger distance between the lexicographers and their users who, in the late 20th century, ended up being characterized as the "well-known unknown" (Wiegand 1977: 59). The upsurge and rapid spread of lexicographical user research during the past three to four decades is as an attempt to remedy this alienation. Publishing houses resort to market research by focus groups in order to get a better grasp on their customers' needs and expectations and thereby raise their sales. Lexicographers employ questionnaires and other methods to get a better picture of the well-known unknown, mostly obtaining general knowledge of usage that can only partially be applied in concrete dictionary projects.

However, it is a question whether this kind of remedial action can replace the direct personal contact with users. Tarp and Ruiz Miyares (2013) report on a special Cuban experience where authors of school dictionaries organize caravans and socialize with teachers and learners. In this way, both users and lexicographers get a better knowledge of each other for the benefit of the quality, relevance and proper usage of the dictionaries.

Gouws (2016) discusses how the authors of the Ju/'hoan Tsumkwe dialect dictionary (Jones et al. 2014) were in personal contact with their target users from a small speech community with an endangered language in order to determine exactly what they needed. Each article in this dictionary contains an illustration made by members of the speech community. These illustrations, respond to real information needs. They help the children to learn the language and grasp the meaning of words unknown to them. The motto was "Hold your people, your language and your culture tightly together".

Similar experiences are rare and highlights the need for a discussion and redefinition of the social role of lexicographers. This redefinition must depart from the need to offer a more personal lexicographical service to users and take into account the current technological possibilities of providing new and better solutions to old problems.

3. The (almost) forgotten reality

Contextualization was an integral part of proto-lexicographic work. In spite of the reduced levels of contextualization and personalization due to the introduction and development of traditional dictionaries some authors of modern-day texts still adhere to the contextualization tradition.1

According to Evans (1979: 104):

The invention of writing was the most revolutionary of all human inventions, for in one great blow it severed the chains which tied an individual and his limited culture to a finite region of space, to a restricted slice of time ...

Manual writing and the later use of the printing press and digital devices created the opportunities to present more and more data and also to integrate different types of data into a single text in order to enhance the successful retrieval of information.

The increased production of texts compelled the authors to ensure that their users understand the texts and this often demanded that a brief explanation of difficult or lesser known words had to be included. As was the case with glosses provided as annotations in manuscripts this contextualization is in an extra-dictionary environment. Today, in extra-dictionary environments, one finds an increase in assistance given to the target readers of different texts in order to meet their specific information needs. This can for example be found in text books where new terms are introduced and these terms are immediately explained so that the user can acquire the necessary text reception help. In the text book Kontemporêre Afrikaanse Taalkunde (Carstens and Bosman 2017), directed at students of Afrikaans linguistics, terms are often introduced and explained to the target users. In their chapter on Pragmatics in this book Van Niekerk and Olivier (2017: 338) make a reference to the Afrikaans terms lokusie, illokusie and perlokusie and immediately explain these terms as follows (the translation has been added):

Die lokusie is die uitspreek van 'n sin met 'n bepaalde verwysing en referensie. (= Locution is the pronunciation of a sentence with a specific reference)

Die illokusie is die uitspreek van 'n sin met 'n bepaalde bedoeling (bevel, ver-soek, ens.) (= Illocution is the pronunciation of a sentence with a specific purpose (command, request, etc.)

Die perlokusie is die uitspreek van 'n sin om 'n bepaalde reaksie by die hoorder teweeg te bring ... (= Perlocution is the pronunciation of a sentence to evoke a specific reaction from the listener)

The explanations represent contextualized data which help the reader to understand a term in a specific context. It constitutes a form of specialized lexicography that continues the scribes' tradition of inserting glosses, and where lexicographic procedures are introduced into an extra-dictionary environment.

Contextualized lexicographical data in texts often take the form of footnotes and endnotes. Burm and Van der Merwe (1973) present the well-known Middle Dutch epic poem Van den Vos Reynarde. Their publication is directed at Afrikaans students of Middle Dutch who are not familiar with all the Middle Dutch words and expressions. The verse lines of the poem are numbered and on each page there are footnotes starting with the number of the line and a problematic word or expression in that line. This is followed by a brief treatment - either an Afrikaans translation equivalent, a translation of a line or a part of the line, a brief grammatical note and often a reference to a specific paragraph in a Middle Dutch textbook.

In a South African edition of the Dutch novel Het Fregatschip Johanna Maria (Van Schendel 1971) certain words in the text have an endnote number. In the back matter section of this novel the endnotes are arranged by chapter and the problematic word in the text is treated by means of a brief explanation of meaning or an Afrikaans translation equivalent. This edition of Van Schendel's novel was specifically prepared for Afrikaans students studying Dutch literature. The endnotes were written by a professor of Afrikaans and Dutch literature and the contextualization is directed at the specific needs of the student target group.

Another text genre where contextualizing procedures can often be found, is restaurant menus. An entry on the menu is often given in a foreign language, the language of origin of the specific dish, followed by a translation equivalent in the default language of the menu or a brief paraphrase of meaning in this default language. A menu of a South African restaurant includes the following entries:

Bobotie

Baked curried mince with ...

The traditional Afrikaans dish (bobotie) is the main entry in this slot on the menu. Before mentioning the accompanying side dishes a brief paraphrase of meaning ("baked curried mince") is given to help the foreign visitor to the restaurant to understand the meaning of the word bobotie. This is yet again an attempt by the compiler of the menu, by means of a procedure of contextualization, to assist the user in retrieving the appropriate information from the entries on the menu.

The restricted environment of a specific text, whether a textbook, novel or menu, and familiarity with the target users of that text makes it easier for authors and compilers of the text to guide their specific readers with respect to specific questions that may arise when the text is read. Contextualized entries like footnotes, endnotes and translation equivalents directed at the explanation of a given word in the text will assist the reader who is not familiar with this word, its meaning or its translation equivalent. This was done in the proto-lexico-graphic works where words in manuscripts were annotated and these endeavours are still used today.

One potential problem with some extra-dictionary contextualization procedures is the fact that the users do not know whether they are accessing curated data or not. In text books users will regard the paraphrases of meaning or the translation equivalents as equal in quality as the data presented in specialized dictionaries. Glosses, annotations and lexicographic contributions in general texts, including menus, are not necessarily seen as having the same authority as comparable entries in dictionaries. This is due to the traditional approach that dictionaries are authoritative sources of information. Unfortunately, practical experience has also shown that lexicographic data in extra-dictionary sources often are incorrect translation equivalents or inappropriate paraphrases of meaning.

Contextualization does not only occur in an extra-dictionary environment. Dictionaries are also texts and the language used in a dictionary may include words or expressions that need to be explained for the target user of the dictionary.

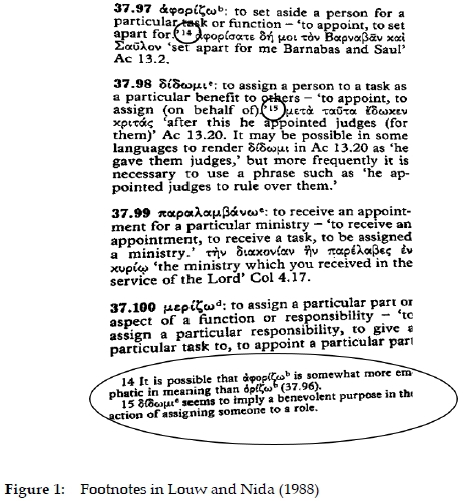

In the Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament based on Semantic Domains (Louw and Nida 1988) footnotes are used to give additional information regarding some aspect dealt with in a dictionary article. Figure 1 contains footnotes 14 and 15 for articles 37.97 and 37.98 respectively that present additional contextualized data.

By adding these footnotes the lexicographers did something similar to what the early scribes have done in their proto-lexicographic work - introduce procedures of contextualization to benefit the target reader.

4. The few visionaries

In the previous sections reference was made to extra-dictionary contextualiza-tion. A question is whether this kind of treatment of words and expressions should be regarded as extra-lexicographical contextualization? The perspective adhered to in this paper is that lexicographic work does not necessarily only have to be performed within dictionaries. Where a word occurring in a text is complemented by either a paraphrase of meaning or a translation equivalent this treatment resembles a part of the treatment typically found in dictionaries, i.e. a lexicographic treatment.

The past decades have witnessed a number of visionary ideas and proposals that can form a basis for a renewed attempt at yet again giving contextuali-zation and personalization their rightful place in lexicographic endeavours.

In the proto-lexicographic environment the scribes knew exactly what the problems of the readers of manuscripts would be. They could predict the words that were in need of explanation and they could provide the necessary contextualized solutions to these problems. Today lexicographers are not in that position where they know exactly what kind of explanation to provide. Hanks (1979: 35) said:

The lexicographer is in the impossible position of a man who undertakes to answer peoples' questions, but since he does not know at the time of compilation what questions exactly his public will ask, he has to word his entries so as to answer all possible questions about them.

These answers are not necessarily directed at the specific needs of the target users and do not enhance either contextualization or personalization. Another linguist had insight in this problem and its detrimental effect on dictionaries. Bolinger (1985: 69) said:

Lexicography is an unnatural occupation. It consists in tearing words from their mother context and setting them in rows ... to make them fit side by side, in an order determined not by nature but by some obscure Phoenician sailors ... Half of the lexicographer's labor is spent repairing this damage to an infinitude of natural connections that every word in any language contracts with every other word .

Bolinger realized the problem but was unable to provide a solution. Some visionary lexicographers did come to the fore with suggestions to counter the problems of decontextualization and to move beyond the unnatural environment of a dictionary towards the provision of personalized data directly in the context where the user experiences an information need.

Bergenholtz (1998: 93) refers to an information tool found in Disney cartoons, i.e. the Junior Woodchucks' Guidebook, introduced in the 1950s, that provides answers to almost all the questions of Donald Duck's nephews Huey, Dewey and Louie. This expresses the need for a personalized information tool that could provide one or more users with all kinds of information they might need and that makes provision for quick and easy access to the data.

The ideas expressed by Hanks, Bolinger and Bergenholtz form a sound basis for further innovative work to ensure higher levels of contextualization and personalization in lexicographic environments - whether in dictionaries or in extra-dictionary sources.

The era of visionary dreaming about these new approaches culminated in De Schryver (2003). He presents a comprehensive list of dreams discussed by a number of lexicographers. These dreams focus on the possibilities the digital environment could offer lexicography. They include hopes for different levels of interface for different users, a personal dictionary and the possibility to choose the content and presentation languages. Such dreams form the basis of enhanced future contextualization and personalization possibilities. It is succinctly expressed by Varantola (2002: 31):

I will be shamelessly selfish and ask for the impossible. I will advocate for a dictionary that will always adapt to my needs and always be ready to provide me with exactly the answer that I need and will also agree with. I also expect the dictionary to be able to give satisfactory answers to those questions that I forget to ask.

It is important to note that Varantola regarded her dream as an impossibility. This also applies to many of the other dreams and suggestions that never came to fruition. The lack of the appropriate technical means played a role in impeding the realization of such proposals. Many of the visions, dreams and proposals were expressed without being sure that the day will come that they could be realized. That time has arrived and lexicographers need to formulate plans that could lead to a new lexicographic dispensation. This paper shows some steps towards this realization.

5. The first lexicographical steps towards a contextualized renaissance

De Schryver (2003) listed more than hundred dreams expressed by a large number of lexicographers in the previous decades. These dreams were, by definition, premature as the corresponding technology was not yet developed. A few of the dreams have subsequently been realised in different tools, at least partially. The rest are still waiting for Godot and many of them will probably share the fate of Vladimir and Estragon.

Since then, lexicographers have not stopped having dreams, or visions, as we prefer to call them.

Gouws (2006), for instance, proposed the idea of a Mutterwörterbuch, a mother dictionary, in the field of bilingual dictionaries with Afrikaans and German as language pair. The idea was that from such a comprehensive bilingual dictionary different users and different user groups would be able to retrieve personalized information directed at their specific punctual needs. Scepticism on the side of a publishing house unfortunately worked against these ideas - also because it would have challenged the then existing technology.

Rundell (2007: 49) emphasizes customization and personalization as "likely new directions" that can unpick "the current globally-marketed one-size-fits-all package", i.e. the standardized dictionary. In the Internet, Google and Wiki-pedia era, a major challenge in terms of learners' dictionaries is to provide information "which is either not available elsewhere, or not available in an easy-to-use form that takes account of learners' needs (and limitations)" (p. 50). How should this be done? According to the British scholar, the way forward is to make the lexicographical resources less static and more dynamic:

A possible scenario is to see our reference materials as a set of components which customers can mix and match according to their needs. (Rundell 2007: 59)

Tarp (2011) continues in the same vein and proposes a future lexicographical Rolls Royce as a possible way forward to "the individualization of needs satisfaction". This vision is explained in more detail by Tarp (2012) who, among other things, highlights "user profiling, situation description and filtering" as techniques to obtain a more personalized product. He also suggests that "each individual user of a lexicographical e-tool will be given the option to design his or her own master article in terms of the types of data wanted and their arrangement on the screen." (Tarp 2012: 261). The technology required to offer this fancy solution is already there, but publishers do not seem to be very enthusiastic about the idea. The reason is probably that they do not expect users - especially those who only occasionally consult a particular e-tool - to be willing to spend their time designing master articles. In this respect, Tarp (2012) represents the necessary exaggerations born out of an over-optimistic view.

Gouws' (2006) "mother dictionary", Rundell's (2007) "mix and match" and Tarp's (2012) "master article" certainly pointed to a further personalization of the lexicographical product. Nonetheless, the proposals were, to a large extent, of little use as they required a number of steps which most users would probably not take. None of the three authors grasped the main picture. If they had looked back at the Classical Greek Period with new eyes, they would have known that personalization, in order to be successful, has to be combined with a new type of contextualization of the lexicographical product. The way forward is not to ask users to go looking for information in new and complex ways, to mix and match components or to design fancy master articles. The real challenge is rather to develop tools that can provide personalized and customized service to users directly in the context where they experience information needs, and without the users having to take any, or only a few, steps to solve their problems.

Just as it was the case with many of the visionary lexicographers mentioned by De Schryver (2003), this limitation in their visions was most likely due to the fact that the relevant technologies allowing us to think out of the box were not yet fully developed, or developed at all. Today, the technology required to take a big step forward is here, at least to a certain extent.

6. The real solution - at least for now

Currently, there are various examples of lexicographical products being integrated into information tools that little by little are closing the more than two thousand year old schism in European lexicography, i.e. reuniting contextuali-zation and personalization. These advanced information tools are above all designed to assist the reading, writing and translation of texts as well as learning in general. In this chapter, we will briefly discuss tools designed to assist e-reading and L2 writing.

Kindle and other e-readers allow users who have comprehension problems to access integrated dictionaries that may provide assistance with a simple click or touch on the word in question. (For examples and a detailed discussion, see Bothma and Prinsloo 2013). The same holds true for various smart phones and tablets.

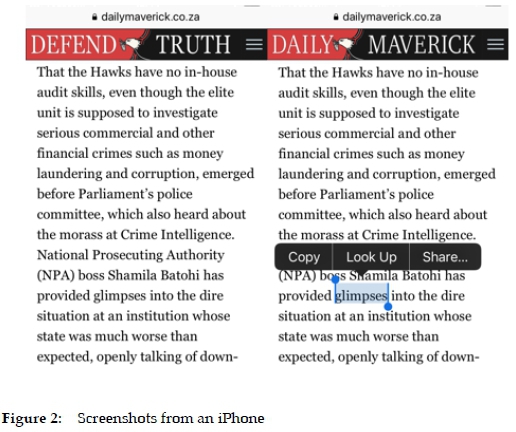

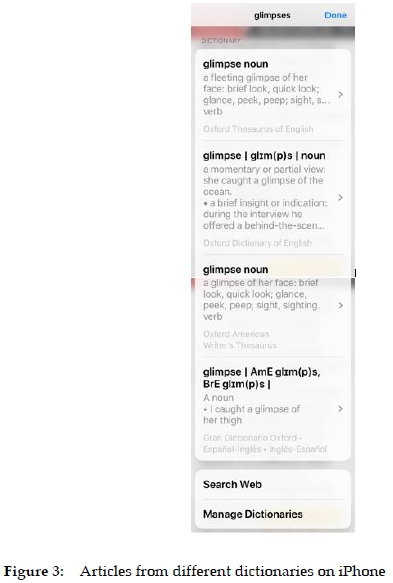

In Figure 2, a person reading an article from a South African newspaper on an iPhone does not understand the word "glimpses" and therefore touches the word with a finger. A little box is immediately displayed on the screen, on which a touch on "Look Up" gives access to a number of preselected dictionaries (Figure 3).

The articles in Figure 3 are taken from four different dictionaries, three monolingual English ones and one biscopal English-Spanish, which have been pre-selected by the owner of the iPhone. If the user does not feel comfortable with these dictionaries and want to re-saddle, a simple touch on the button "Manage Dictionaries" unfolds a page where the user can delete some of the dictionaries and add others that are more adapted to his or her profile. In this way, the user can personalize the lexicographical service requested from the device.

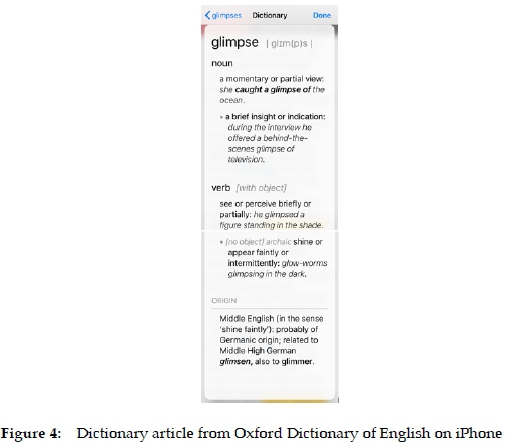

If the user wants to continue the search process, he or she may access one of the dictionary articles indicated in Figure 3, for instance the one from the Oxford Dictionary of English. To the big surprise for users of high-tech tools, a ghost from the past then appears in the form of a traditional dictionary article. The two articles displayed in Figure 4, which in this case contain few senses, also include data types (e.g. pronunciation and etymology) which are completely irrelevant for a user who just wants to understand a specific word. This results in lexicographical data overload as defined by Gouws and Tarp (2017). The user therefore frequently has to scroll down in order to find first the word class and then the sense that are relevant in each consultation, as neither word classes nor senses are prioritized according to the specific context. This prolongs and complicates the search process and goes against the idea of contextualization.

Hence, on the one hand, the user gets access to the lexicographical service directly in the context where the information need occurs, i.e. contextualiza-tion. On the other hand, the long road to the required data means that full contextualization is still a challenge to modern lexicography and producers of high-tech tools. Currently, companies like IBM are conducting comprehensive interdisciplinary research in order to develop a tool that can deduce the specific meaning of a word from the context. Unfortunately, and as far as we are informed, they have not yet come up with any convincing results.

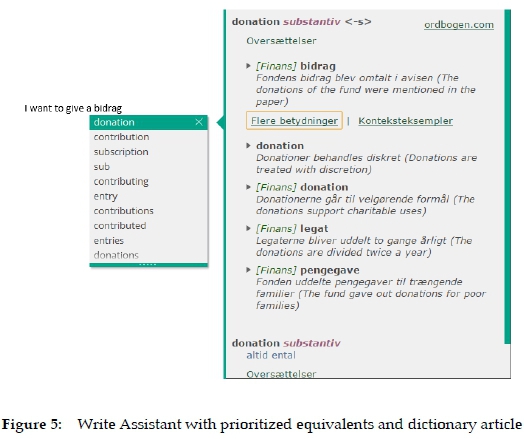

More or less the same applies to the writing assistant produced by the Danish company Ordbogen A/S; c.f. Tarp et al. (2017). This tool, branded as Write Assistant, is designed to provide instantaneous assistance to L2 users who may have language problems when writing in English. So far it is available for users with Danish, Spanish, German, French, Italian and Arabic as a mother tongue. In contrast to the monolingual writing assistants which are available on tablets and smart phones, the Danish Write Assistant does not only provide word terminations and predict the next word in the sentence. It also offers L2 equivalents when the users write an L1 word, as well as the possibility to access a dictionary article directly from the suggested words or equivalents (Figure 5).

Instead of expecting an active role from users, which in most cases would be highly unlikely, Write Assistant "observes" its users and, on this basis, chooses the set of lexicographical data most likely to meet their needs in each concrete situation. These data are placed in the immediate vicinity of the word that may pose challenges to the writer. This is shown in the small window in Figure 5, where the English equivalents to the Danish word bidrag are placed directly below this word. In addition, the order of the equivalents is prioritized by the tool based on an automatic analysis of the context and the calculation of the most likely solution in this particular context.

When the word or equivalent suggested by Write Assistant is sufficient to meet the user's needs - for instance, if it is only used as a reminder - the tool has achieved the complete reunification of personalization and contextualiza-tion.

However, if the user is not sure which of the suggested words to use, or how to use it, and therefore proceeds to open the big window by touching or clicking on one of the suggested words, a problem similar to the one discussed above appears. As can be seen in Figure 5, the dictionary article, which is a beta version, is still very traditional and therefore not fully adapted to the user's needs in each consultation. With the introduction of artificial intelligence in the autumn of 2019 as well as a much closer interdisciplinary collaboration between lexicographers, designers and information engineers, the provider of the tool expects to eventually uncover the scribes' 2 500 years old secret in the nearby future.

In this respect, it is worth stressing that lexicography is no longer the responsibility of a lone ranger on a white horse. Team work has become extremely important. Collaboration with other fields like information science is a prerequisite for successful lexicographic endeavours in the digital era.

7. Perspectives

The past few years have seen a continuous development of the new disruptive technologies with the introduction of neural networks, artificial intelligence, among others. These technologies are now making their ways into lexicography and the production of information tools in general. As a result, lexicographers are exposed to new horizons.

With contextualization and personalization being reunited we are on the brink of seeing the end of the schism that existed for so long in lexicography. The accumulation of more than two thousand years of dictionary-making experience puts the modern scribes in a much better position to produce con-textualized and personalized lexicographical data. These efforts are supported by innovative ways of providing an information merge through the mediation of new technologies. This ascertains yet again that lexicography as a discipline is now closely related to information science.

Modern-day lexicographers are in a position to make some of the unfulfilled dreams of the past a reality. The challenge of the future is to make the impossible possible.

We have work to do.

9. Literature

Al-Kasimi, A.M. 1977. Linguistics and Bilingual Dictionaries. Leiden: E.J. Brill. [ Links ]

Bergenholtz, H. 1998. Das schlaue Buch. Vermittlung von Informationen für textbezogene und textunabhängige Fragestellungen. Zettersten, A., J.E. Mogensen and V.H. Pedersen (Eds.). 1998. Symposium on Lexicography VIII. Proceedings of the Eighth International Symposium on Lexicography May 2-4, 1996 at the University of Copenhagen: 93-110. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer. [ Links ]

Bolinger, D. 1985. Defining the Indefinable. Ilson, R. (Ed.). 1985. Dictionaries, Lexicography and Language Learning: 69-73. Oxford: Pergamon Press. [ Links ]

Bothma, T.J.D. and D.J. Prinsloo. 2013. Automated Dictionary Consultation for Text Reception: A Critical Evaluation of Lexicographic Guidance in Linked Kindle e-Dictionaries. Lexicographica 29(1): 165-198. [ Links ]

Burm, O.J.E. and H.J.J.M. van der Merwe. 1973. Van den Vos Reynarde. Pretoria: J.L. van Schaik. [ Links ]

De Schryver, G.-M. 2003: Lexicographers' Dreams in the Electronic-Dictionary Age. International Journal of Lexicography 16(2): 143-199. [ Links ]

Evans, C. 1979. The Micro Millennium. New York: Viking. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. 2006. Die zweisprachige Lexikographie Afrikaans-Deutsch - Eine metalexikogra-phische Herausforderung. Dimova, A., V. Jesensek and P. Petkov (Eds.). 2006. Zweisprachige Lexikographie und Deutsch als Fremdsprache: 49-58. Hildesheim: Georg Olms. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. 2016. Enkele minder bekende Afrikaanse woordeboekmonumente. Tydskrif vir Gees-teswetenskappe 56(2-1): 355-370. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. and S. Tarp. 2017. Information Overload and Data Overload in Lexicography. International Journal of Lexicography 30(4): 389-415. [ Links ]

Hanks, P. 1979. To What Extent Does a Dictionary Definition Define? ITL 45-46: 32-38. [ Links ]

Hanks, P. 2013. Lexicography from Earliest Times to the Present. Allan, K. (Ed.). 2013. The Oxford Handbook of the History of Linguistics, 503-536. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Jones, K.L. et al. (Eds.). 2014. Ju/hoan Tsumkwe Dialect/Prentewoordeboek vir kinders/Children's Picture Dictionary. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press. [ Links ]

Louw, J.P. and E. Nida. 1988. Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament Based on Semantic Domains. New York: United Bible Societies. [ Links ]

Pálfi, L.-L. and S. Tarp. 2009. Lernerlexikographie in Skandinavien - Entwicklung, Kritik und Vorschläge. Lexicographica 25: 135-154. [ Links ]

McArthur, T. 1986. Worlds of Reference. Lexicography, Learning and Language from the Clay Tablet to the Computer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Postlethwayt, M. 1774. The Universal Dictionary of Trade and Commerce: With Large Additions and Improvements, Adapting the Same to the Present State of British Affairs in America, Since the Last Treaty of Peace Made in the Year 1763. With Great Variety of New Remarks and Illustrations Incorporated throughout the Whole: Together with Everything Essential that is Contained in Savary's Dictionary: Also, All the Material Laws of Trade and Navigation Relating to these Kingdoms, and the Customs and Usages to which All Traders are Subject. The Fourth Edition. London: W. Strahan, J. and F. Rivington, J. Hinton. [ Links ]

Rundell, M. 2007. The Dictionary of the Future. Granger, S. (Ed.). 2007. Optimizing the Role of Language in Technology-enhanced Learning. Proceedings of the expert workshop organized in Louvain-la-Neuve (Belgium), 4-5 October 2007: 49-51. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00197203/document/. (Consulted 4 July 2019).

Stathi, E. 2006. Greek Lexicography, Classical. Brown, K. (Ed.). 2006. Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics. Vol. 5: 145-146. Second Edition. Oxford: Elsevier. [ Links ]

Tarp, S. 2011. Lexicographical and Other e-Tools for Consultation Purposes: Towards the Individualization of Needs Satisfaction. Fuertes-Olivera, P.A. and H. Bergenholtz (Eds.). 2011. e-Lexicography: The Internet, Digital Initiatives and Lexicography: 54-70. London/New York: Continuum. [ Links ]

Tarp, S. 2012. Online Dictionaries: Today and Tomorrow. Lexicographica 28(1): 253-267. [ Links ]

Tarp, S. and T.J.D. Bothma. 2013. An Alternative Approach to Enlightenment Age Lexicography: The Universal Dictionary of Trade and Commerce. Lexicographica 29(1): 222-284. [ Links ]

Tarp, S. and L. Ruiz Miyares. 2013. Cuban School Dictionaries for First-Language Learners: A Shared Experience. Lexikos 23: 414-425. [ Links ]

Tarp, S., K. Fisker and P. Sepstrup. 2017. L2 Writing Assistants and Context-Aware Dictionaries: New Challenges to Lexicography. Lexikos 27: 494-521. [ Links ]

Van Niekerk, A. and J. Olivier. 2017. Pragmatiek. Carstens, W.A.M. and N. Bosman (Eds.). 2017. Kontemporêre Afrikaanse Taalkunde: 329-363. Pretoria: Van Schaik [ Links ]

Van Schendel, A. 1971. Het Fregatschip Johanna Maria. (South African edition). Pretoria: Academica. [ Links ]

Varantola, K. 2002. Use and Usability of Dictionaries: Common Sense and Context Sensibility? Corréard, M.-H. (Ed.). 2002. Lexicography and Natural Language Processing: A Festschrift in Honour of B.T.S. Atkins: 30-44. Göteborg: EURALEX. [ Links ]

Wiegand, H.E. 1977. Nachdenken über Wörterbücher. Aktuelle Probleme. Drosdowski, G., H. Henne and H.E. Wiegand (Eds.). 1977. Nachdenken über Wörterbücher: 51-102. Mannheim/Vienna/Zürich: Bibliographisches Institut. [ Links ]

1. As indicated earlier in this article we use the term contextualization in a way that deviates from the way in which it is often used in lexicography and linguistics. In this paper it refers to the provision of solutions to users' information needs directly in the situation or context where these needs occur.