Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Lexikos

versão On-line ISSN 2224-0039

versão impressa ISSN 1684-4904

Lexikos vol.29 Stellenbosch 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.5788/29-1-1518

ARTICLES

African Language Dictionaries for Children - A Neglected Genre

Afrikataalwoordeboeke vir kinders - 'n miskende genre

Elsabé TaljardI; Danie PrinslooII

IDepartment of African Languages, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa (elsabe.taljard@up.ac.za)

IIDepartment of African Languages, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa (danie.prinsloo@up.ac.za)

ABSTRACT

Children's dictionaries are instrumental in establishing a dictionary culture and are the gateway to sustained and informed dictionary use. It is therefore surprising that very little attention is paid to these dictionaries in scholarly research. In this article we reflect on the design of two series of dictionaries and one free-standing dictionary, all presumably aimed at first-time dictionary users, specifically looking at how selected design elements are aligned with the lexicographic needs of the target users. We argue that the conceptualization of children's dictionaries for African-language-speaking children should be a bottom-up process, and that an Afrocentric approach, taking the target user's Frame of Reference as the point of departure, is preferable to a Eurocentric approach, which often leads to a mismatch between conceptual relationships and linguistic form and function in African language dictionaries.

Keywords: children's dictionaries, african language dictionaries, user's perspective, theory of lexicographic communication, afrocentric approach to dictionary compilation, user's frame of reference (for)

OPSOMMING

Kinderwoordeboeke speel 'n belangrike rol in die vestiging van 'n woordeboekkultuur en gee toegang tot volgehoue en kundige woordeboekgebruik. Dis is daarom vreemd dat daar min aandag gegee word aan hierdie tipe woordeboeke in akademiese navorsing. In hierdie artikel besin ons oor die ontwerp van twee woordeboekreekse en 'n vrystaande woordeboek, wat almal oënskynlik gemik is op beginnergebruikers van woordeboeke. Ons kyk spesifiek na die belyning van die ontwerp-aspekte van die woordeboeke met die gebruikers se leksikografiese behoeftes. Ons dui aan dat die konseptualisering van kinderwoordeboeke vir sprekers van Afrikatale op grondvlak behoort te begin, en dat 'n Afrosentriese benadering verkieslik is bo 'n Eurosentriese benadering. Laasge-noemde benadering lei dikwels tot 'n mispassing tussen konseptuele verhoudings, en linguistiese vorm en funksie in Afrikataalwoordeboeke.

Sleutelwoorde: kinderwoordeboeke, afrikataalwoordeboeke, gebruikers-perspektief, teorie van leksikografiese kommunikasie, afrosentriese benadering tot woordeboekkompilasie, gebruiker se verwysingsraamwerk

Introduction

Judging by the dearth of research on children's dictionaries, lexicographers do not seem to regard this dictionary genre as worthy of serious academic attention. The situation is even worse for children's dictionaries published in the (South) African languages. With the exception of the publication of Gouws, Prinsloo and Dlali (2014) and an MA dissertation by Putter (1999), children's dictionaries have not been the focus of lexicographic research, attracting little more than a sidelong reference in general discussions on lexicographic theory and practice. Gouws (2013) does however refer to the important role that foundation phase dictionaries, i.e. dictionaries aimed at 7-9 year olds, play in the establishment of a dictionary culture in South Africa. He rightly remarks that "a general theory of lexicography [...] should assist any lexicographer planning any new dictionary, also foundation phase dictionaries". Dictionaries for children are the gateway to the establishment of a dictionary culture and it is therefore surprising that the compilation and evaluation of such dictionaries receive so little attention from researchers in lexicography.

The Oxford First Bilingual Dictionary series, e.g. the Oxford First Bilingual Dictionary Setswana + English (2008) reflects a layout by topic, indexes in English and Setswana and has a curriculum focus. Such a thematic ordering as well as the provision of indexes was also followed in a series of Foundation Phase dictionaries published by Maskew Miller Longman in 2010 and the Official Foundation Phase CAPS dictionaries of the South African National Lexicography Units (2018).

In this article we reflect on the design of two series of dictionaries and one free-standing dictionary, all presumably aimed at first-time dictionary users, specifically looking at how selected design elements are aligned with the lexicographic needs of the target users.

Our study takes the user's perspective as its point of departure, but we also refer to Beyer's theory of lexicographical communication, specifically referring to the importance of the user's Frame of Reference (Beyer 2014). The dictionaries on which our investigation will focus are:

- A series of Foundation Phase dictionaries, 2010, published by Maskew Miller Longman (henceforth MML dictionaries);

- The Official Foundation Phase CAPS dictionaries, 2018, published by the South African National Lexicography Units (henceforth NLU dictionaries); and

- The Jufhoan Children's Picture Dictionary, 2014, published by University of KwaZulu-Natal Press (henceforth JCP dictionary).

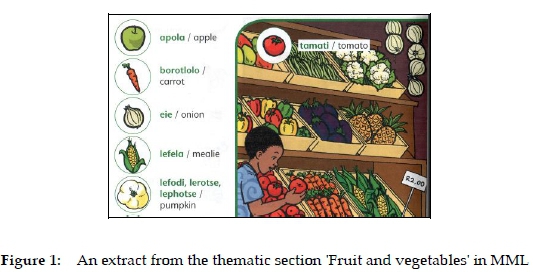

The first two titles both constitute a series of bilingual dictionaries, with each dictionary treating English and an African language. Both dictionaries consist of three major sections, i.e. a picture section on specific themes such as 'my body', 'clothes', 'my family', 'our home', 'in the kitchen', etc., followed by sections where lemmas are presented in alphabetical order in English and the relevant African language (with or without treatment), and page numbers linking the word with its illustration in the thematic section. Figure 1 is an extract from the thematic section of MML.

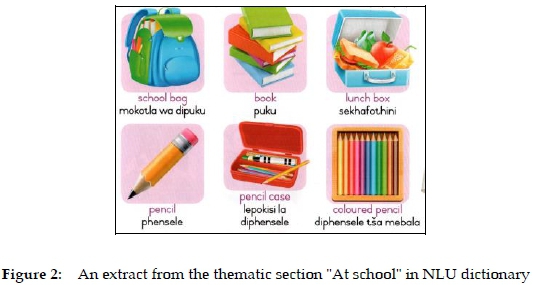

In the NLU dictionaries a similar thematic pictorial approach is followed, but pictures are mainly presented individually as in figure 2. Indexes in English and the African language of the words and their illustrations are given, with page numbers linking the lemma with its pictorial illustration.

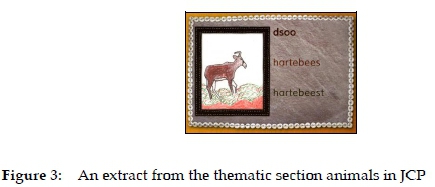

The third dictionary is free-standing, treating three languages, i.e. Ju | 'hoan, Afrikaans and English. Ju|'hoan is a Northern Khoesan language, spoken by San people in Namibia and Botswana. It is an endangered language, spoken by 11 000 speakers. The Ju| 'hansi people are to a large extent a marginalized society, trying to survive under difficult socio-economic circumstances. In the JCP the thematic section focuses on animals, birds, insects, hunting, dance, and home and family - themes of importance in the everyday life of Ju | 'hoan children, cf. figure 3. At the back of the dictionary a translated word list per theme of the Afrikaans words in Ju|'huansi and English is given with page references to words and their pictorial illustrations in the main section of the dictionary.

In all of these dictionaries, treatment revolves around pictorial illustrations. Cianciolo (1981: 1) says picture books in general communicate with and appeal to children; they enrich, extend and expand children's background of experiences. Al-Kasimi (1977: 97) however says that the importance of pictorial illustrations is not always taken seriously and that the use of pictorial illustrations is rarely dealt with in the literature on lexicography. Gouws et al. (2014: 39) conclude that "the challenge for the lexicographer is to maintain a sound balance between the selection of the terms, the extent of the treatment, the detail of the distinction and the target user's skills and existing knowledge." Gouws et al. (2014: 25), emphasize that no single dictionary can be everything for everyone. This also holds true for dictionaries directed at specific target users, and each dictionary has to be considered as part of the broader family of dictionaries and not as an isolated product.

In order to contextualize our study, we will first present some terminological clarification as to the use of the terms 'children's dictionaries' versus 'picture dictionaries' since it has transpired that some confusion exists regarding the use of these terms. This will be followed by a classification of the dictionaries according to Tarp's (2011) suggested dictionary typology. Since we approach our discussion from a user's perspective, we then attempt to establish the profile of the intended users and their lexicographic needs, because these aspects are crucial in the planning and conceptualization of a dictionary. It has to be mentioned that whilst monolingual picture dictionaries might be regarded as the norm in the rest of the world, learners in South Africa are expected to use bilingual dictionaries, which immediately place them in relation to the dominant language (English). A detailed discussion of the preference for and/or desirability of monolingual versus bilingual dictionaries, how-ever, fall outside the scope of this article. We discuss the issue of an Afrocentric versus a Eurocentric approach to compiling dictionaries for African language children. A critical analysis of the selection of visual content viewed against the initial conceptualization is followed by suggested guidelines for illustrations in children's dictionaries. Since paper dictionaries are still the norm for African language speaking children, our discussion is restricted to paper dictionaries.

Children's dictionaries/picture dictionaries: terminological clarification

As Tarp (2011: 229) points out, commercial publishing houses cannot be expected to use scientifically correct terms for their products. Their use of terminology is determined by their target market rather than by a desire to be scientifically correct. In the academic literature, it seems that a terminological distinction is made between picture dictionaries on the one hand, and children's dictionaries on the other. The term 'picture dictionary' is used to refer to a special type of dictionary, especially designed to assist people with speech disabilities or no speech to communicate. These dictionaries therefore do not only have children as their target users and they are often tailor-made to the needs of a specific user and usage situation. Even so, the term 'picture dictionary' is used by publishers to refer to and market dictionaries aimed at children, where pictures or illustrations provide access to the lexicographic information provided in the dictionary. Two of the dictionaries under discussion in this article contain the words 'picture dictionary' in their titles, despite their intended target users not fitting the profile of users of picture dictionaries as described in the academic literature. The term 'children's dictionary' is perhaps a more apt designation for the dictionaries under discussion in this article. All three dictionaries are ono-masiological in nature, moving from a concept via a pictorial illustration to a word and its meaning. The onomasiological nature of these specific dictionaries is the essential feature that distinguishes them from other dictionaries, such as what is generally termed school dictionaries. An onomasiological approach provides a natural fit for a thematic - instead of an alphabetical - ordering, since concepts and their accompanying illustrations, related to a specific theme, are grouped together. Access to the information contained in the dictionary is therefore via the illustration, and on finding the relevant picture, the user should be able to connect the concept to its linguistic representation, i.e. the lemma.

Typological contextualization

In terms of Tarp's (2011) typology of pedagogical dictionaries the dictionaries under investigation straddle two typological categories. In terms of the age of the target group, these dictionaries are classified as school dictionaries, and if the type of learning that the dictionaries are supposed to support is taken as a typological criterion, they should be classified as dictionaries for both native language and non-native language learners. The category 'school dictionary' can, in terms of the South African education system, be further subdivided according to the educational phase of the target users, i.e. Foundation Phase (Grades 1 to 3, although Grade 0 or R is sometimes informally included), Intermediate Phase (Grades 4-7), Senior Phase (Grades 7-9), which all fall within the General Education and Training Band, and the Further Education and Training Band (Grades 10-12). The first two dictionaries that we refer to in our discussion are both aimed at Foundation Phase learners, i.e. learners in the age bracket of roughly 7 to 9 years, or 6 to 9 years if Grade 0/R is included. This is also reflected in the titles of the two dictionaries. These learners are typically pre-literates to early literates. Linking a dictionary to a specific educational phase is a generally recognized marketing strategy amongst (South African) publishers - it is aimed at assisting parents and teachers in the selection of an appropriate dictionary. Furthermore, schools (via the provincial departments of education) are the main potential clients of dictionary publishing houses. The Ju/'hoan Children's Picture Dictionary, published for Namibian children, does not refer explicitly to any educational phase of the target users, other than simply indicating that it is a dictionary for children.

Profiling the user

Identifying the target user of the dictionaries under discussion seems a straightforward exercise. We have already referred to the age group at which these dictionaries are aimed. From a pedagogical perspective, the target users of the MML and NLU dictionaries are learners who - according to the official policy of the Department of Basic Education - receive instruction in their home language for the first three years of formal schooling (i.e. from grade 1).1However, as South Africa is a multilingual environment, the learning of a second or additional language plays an important role, since, for many learners, the language of instruction switches to English in their fourth year of schooling. It is therefore important that learners be exposed to English from early on. Gouws et al. (2014: 26) however, point out that the need for dictionaries directed at learners' home languages should never be denied. In order to promote multilingualism, it is important that South African learners have a solid grounding in and knowledge of their home language before moving on to the acquisition of a second language, cf. Gouws et al. (op. cit.). The emphasis when planning a dictionary for these target users should therefore be on assisting users with the understanding of basic concepts, appropriate for their age level, in their home language, thus bridging the gap between pre-literacy and literacy. A secondary aim should be the provision of access to English as an additional language. Such an approach would also be in line with the official Language in Education policy, in which the promotion of additive bilingualism is stated as one of the aims of the Ministry of Education's language policy, cf. https://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/DoE%20Branches/GET/GET%20Policies/LanguageEducationPolicy1997.pdf?ver=2008-06-28-134223-253.

The target user of the JCP dictionary has a different profile. The title of the dictionary refers to children as target users, without specifying their age. In the front matter of the dictionary, it is stated that native-speakers of Ju|'hoansi and learners of Ju|'hoansi as an additional language can use the dictionary. In the case of the MML and NLU dictionaries, the target user is contextualized within the formal South African education system, and the dictionary is presented as a tool that can support learners within a school environment. These aspects are lacking in the case of the JCP dictionary. In fact, it is not clear to what extent the children in the Ju|'hoan community are exposed to formal schooling, or what language that schooling is offered in.

Although the delineation of the intended user of the MML and NLU dictionaries seems clear, one can argue that it represents a rather over-simplified view of the actual grass roots situation in South African schools. Target users of school dictionaries in South Africa are extremely diverse, reflecting the inequalities that continue to plague South African society, with educational inequalities being among the most prominent. Webb (1999: 358) identifies three sociolinguistic categories relevant to the education sector, i.e. larger urban areas, smaller urban areas and deep rural areas. Each of these categories has its own profile with regard to, inter alia, the level of exposure to an additional language, the general literacy level and the prominence of African languages as languages of teaching and learning. Although it would be unfair to expect of lexicographers and publishing houses to make provision for the total diversity of the target users, we are of the opinion that this aspect needs to be considered, specifically with reference to series of dictionaries, such as the MML and NLU dictionaries. In each dictionary of the series, a different language pair is treated. Even within the parameters set by the curriculum of the Foundation Phase that forms the basis of these dictionaries, some leeway for differentiation between language pairs should exist and should be explored by lexicographers and publishers. This issue is discussed below and illustrated by means of practical examples.

Conceptualization of the dictionary: top down or bottom up?

It is generally accepted within the lexicographic community that the compilation of any dictionary must be preceded by proper planning, cf. Gouws and Prins-loo (2005: 13-19). During the planning phase, issues such as the organisation plan, the genuine purpose and lexicographic function, and the conceptualization of the dictionary are considered. Dictionary planning is thus a pragmatic and concrete process, with tangible outputs. These processes are however, very seldom documented and any researcher interested in these inner workings of the lexicographic process for any specific dictionary or dictionary project has mostly to rely on information provided in the front matter of the dictionary, in media releases and marketing blurbs. Additionally, this type of information has to be inferred from an analysis of the structure and content of the dictionary. Fortunately for the MML dictionaries, a description of the planning process is provided in Gouws et al. (2014: 26, 27). They indicate that the dictionaries are aimed at native-speakers of the respective languages, but provision is to be made for access to English as an additional language. This means that, for example, the Sepedi-English version of the dictionary series is aimed at native-speakers of Sepedi who are learning English as a first additional language. The dictionaries are furthermore envisaged as assisting users with text reception and text production, as well as serving their cognitive needs. This then constitutes the genuine purpose of the dictionary. In the user's guide of these dictionaries, the information about the genuine purpose of the dictionary is confirmed and also conveyed to the user. Compare the following excerpt from the Sepedi-English dictionary:

This dictionary will help you to:

- speak, read and write in Sepedi as Home Language

- understand and use English as Additional Language

- learn and use Sepedi as Additional Language.

In addition to the explicit formulation of the genuine purpose of these dictionaries, the lexicographers have stated a complementary aim, i.e. the establishment and promotion of a dictionary culture, familiarizing target users with the dictionary as a practical instrument that can play an important role in the process of lifelong learning, cf. Gouws et al. (2014: 27).

As is the case regarding the MML dictionaries, the NLU dictionaries' genuine purpose is that of production, reception and cognition, and they also echo the sentiment of establishing a dictionary culture from an early age. However, the NLU dictionaries are less clear about the language profile of their intended target user, stating in the user's guide to these dictionaries that they were designed to assist learners with learning the relevant African language or English as an additional or second additional language. This seems to imply that either the African language or English could be the home language of the intended target user. However, it is also indicated that the dictionary can be instrumental in the transition from the African language as medium of instruction in the Foundation phase to English as medium of instruction in the Intermediate phase, thus implying that the actual target users are speakers of an African language as home language, who are learning English as their first additional language. This would be in line with the actual situation in South African classrooms, where 81.9% of learners in the Foundation phase have an African language as home language2. As dictionaries are compiled for specific users, it is extremely important that lexicographers should be clear about the language profile of the target user, since the language through which the user will access the information in the dictionary will have a direct impact on the structure of the dictionary - it would, inter alia, determine the language of lemmatization and also the metalanguage used in the dictionary.

Gouws (2016: 365) points out that the genuine purpose of a dictionary may extend beyond the mere extraction of information from the data that is provided for the lexical items represented by the lemma signs. The information leaflet that accompanies the JCP dictionary states that the compilation of the dictionary is a "community-driven project that highlights Ju|'hoan culture". From the rudimentary microstructure, the nature of the illustrations and layout of the dictionary, it is clear that extraction of information through a detailed lexicographic treatment is not the main aim of the compilers of this dictionary. The editorial team consisting of academics, project advisors and illustrators also includes members of the Ju|'hoan community, and another stated aim of the team is to create a broader awareness about the Ju|'hoan language and culture, and to prevent this endangered language from disappearing forever.

It is essential that the genuine purpose of the dictionary needs to be realized in the compilation thereof. The extent to which the final lexicographic product is aligned with its genuine purpose will determine its usefulness as a lexicographic utility tool.

Since the MML and NLU dictionaries are school dictionaries, it is to be expected that their content must be aligned and integrated with the curriculum for the relevant educational phase at which these dictionaries are aimed. Both the MML and NLU dictionaries emphasize the fact that the content is structured to align with information provided in the Curriculum Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) documents. These documents are official documents, from the Department of Basic Education, setting out the policy on curriculum content and assessment for each educational phase. The users' guides to both dictionaries indicate that the dictionaries are theme based, and that the selection of themes was done according to the CAPS for the Foundation Phase.

Basing a dictionary and its contents on a prescribed school curriculum implies that the conceptualization of the dictionary was in essence top-down. The contents of the dictionary, i.e. the themes to be addressed, as well as the lemma list are to a certain extent predetermined. The user's guide to the NLU dictionaries states that the themes include the basic words of objects and actions that learners may encounter in everyday life. This statement raises an issue that is particularly pertinent to children's dictionaries, i.e. the notion that literature aimed at children needs to relate to the child's lived experience and that lexicographers should take cognisance of the user's frame of reference (FoR). The other side of the lexicographic coin is that lexicographers also operate from within their own frame of reference. According to Beyer's (2014) theory of lexicographic communication (TLC), the FoR of the lexicographer is part of the expressive information conveyed in a dictionary. Expressive information refers to information about the lexicographer as sender, one aspect of which is the lexicographer's frame of reference (FoR). He states the following in this regard: "Both the sender's and the receiver's frame of reference (=FoR) come into play here, since messages are construed and encoded in utterances against the sender's FoR, and utterances are decoded and messages reconstructed against the receiver's FoR" (Beyer 2014: 47). In the case of children's dictionaries, it is almost inevitable that the (adult) lexicographer's frame of reference and that of the child as target user will not coincide, resulting in an unsuccessful transfer of the lexicographic message to the user, or simply put, an unsuccessful dictionary consultation. Nevertheless, determining the FoR of the target user should form part of the dictionary planning process and should not be left to supposition. Granted, determining the FoR of children in this specific age bracket is no mean task. One possible solution is suggested by Cignoni et al. (1996): "It is important to evidence the significance and determining aid that children can give to the compilation of a dictionary designed for their purposes and needs". They suggest that children as target users of the planned dictionary should not only be seen as users of the final product, but they should also participate in the compilation of the dictionary as a utility tool. Involving the target user in the planning and conceptualization of the dictionary would constitute a bottom-up process, which could contribute to bridging the gap between the perceived FoR of children and their actual FoR. Determining the FoR of South African Foundation Phase learners is complicated by the heterogeneous nature of the target user, as pointed out earlier. In this regard, the planning and conceptualization of the JCP dictionaries represent an innovative and creative approach. The planners of this dictionary had the advantage of a small, homogeneous body of target users, whose FoR is easier to determine. In an information pamphlet accompanying the dictionary, it is stated that members of the community led the way in the selection of themes, lexical entries, design and layout, and that children were actively involved in developing the JCP dictionary.

The themes that have been selected in the JCP use the real life experi-ence(s) of the target user as their point of departure and reflect the lived experiences of the target users. These themes are: animals, birds, insects, reptiles and creepy crawlies, home and the family, hunt, gather and dance. Selecting themes that children as dictionary users can relate to and which fall within the ambit of their FoR can contribute not only to a successful dictionary consultation process, but also to the establishment of a dictionary culture.

A second aspect of the top-down approach is the motivation for the compilation and publishing of the dictionary. For both the MML and the NLU dictionaries, the initial motivation for the dictionaries was to a certain extent externally motivated. Gouws et al. (2014: 24) point out that it is common practice in South Africa for commercial publishers to take responsibility to continue providing dictionaries to satisfy the lexicographic needs of different user groups with different needs and reference skills. With regard to the MML dictionaries, Gouws et al. (op. cit.) state that "[i]n order to meet the lexicographic needs of a new generation of South African learners, the publishing house Maskew Miller Longman (MML) decided to launch a series of dictionaries in different official languages which are aimed at learners in the foundation phase of primary school". Even though externally (and commercially) motivated, such an approach should not be viewed in a negative light. The publishing of dictionaries as a commercial venture actually works to the advantage of the production of good dictionaries. A dictionary that satisfies the needs of the intended user should - at least in theory - add to the commercial value of the dictionary, although we recognize the fact that quality content is not the only factor that determines whether a dictionary will sell or not. Even so, it is in the interest of publishers to avail themselves of the services of lexicographers, experts in education and language experts in order to ensure the publication of a good dictionary. This is exactly the approach taken by the publishers of the MML dictionaries.

The NLU dictionaries, on the other hand, have been compiled to fulfil a legislative obligation, and are thus also externally motivated. The back cover of each of the dictionaries in the series states that the dictionary is a product of the relevant NLU, who is "constitutionally and legislatively mandated to develop dictionaries and other material, on behalf of the South African government, in order that all Government Departments and Agencies, public and private schools, tertiary institutions and libraries have the resources needed to fulfil their obligations to all our country's indigenous languages". We do recognize that the fulfilment of a legislative obligation does not exclude other motivational factors such as commercial interests or competition from other publishers, but these considerations are not always made public. A strong point in favour of these dictionaries is the fact that they have been compiled by trained lexicographers, who are also first language speakers of the relevant African languages. However, a question that needs to be asked is to what extent the input of the lexicographers was restricted by the publisher.

Although the compilation of the JCP dictionary is also not entirely internally motivated, there is evidence of a much greater involvement and support from the Ju|'hoan community. As already indicated, the selection of the themes to be addressed was done in collaboration with members of the community, but perhaps even more significantly, the illustrations, as well as the sound and video recording which appears on a CD-ROM that accompanies the dictionary, were all done with the direct assistance of community members. This dictionary is probably the most successful in terms of establishing the FoR of the target users, and secondly in terms of the involvement of the speaker community in the initial planning and conceptualization of the dictionary.

Eurocentric or Afrocentric?

In a discussion regarding the Eurocentric versus the Afrocentric nature of African language dictionaries, Prinsloo (2017: 5) sketches a number of scenarios for African language dictionaries. These scenarios range from dictionary compilation by foreigners abroad, which represents a true Eurocentric approach, to dictionary compilation by African language speakers, which represents a true Afro-centric approach. According to Gouws (2007: 315), the linguistic situation in postcolonial Africa has resulted in a "drastic swing from externally motivated to internally motivated dictionaries, resulting in a situation which sees the majority of new lexicographic projects in Africa characterized by an Afro-centred approach that deviates from the Eurocentred approach". This seems to be a rather over-optimistic view of the current state of African language dictionaries. Being internally motivated and compiled by African language speakers does not guarantee an Afrocentric approach to dictionary compilation. Prah (2007: 23) is rather blunt in his condemnation of the current situation, referring to "cultures and languages of the majorities [which] are suppressed and silenced in favour of a dominant Eurocentric high culture, which everybody is willy nilly obliged by force of circumstance to emulate".

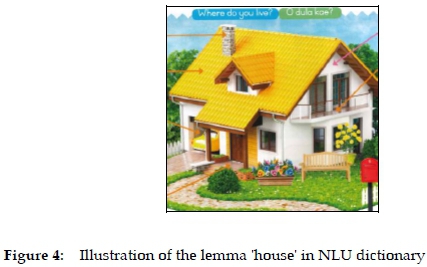

A children's dictionary that is truly Afrocentric is much more than a dictionary characterized by a superficial adaptation of illustrations depicting black children instead of their white counterparts. It is a dictionary that is sensitive to portraying anything European as the default and as an ideal that has to be emulated. In the following example, the concept 'my house', taken from the NLU series is represented by an illustration that is unmistakably a typical European dwelling:

There is no denying the fact that many African language speaking children do grow up in houses such as these, but the reality in South Africa is that many children grow up in townships, informal settlements and rural areas where dwellings look much different from the one depicted above. A dictionary that is truly Afrocentric should make provision for the fact that a less formal or traditional dwelling can also represent the concept 'my house', cf. the illustration for the concept 'house' in the JCP dictionary:

The dictionary should furthermore also be sensitive to what can at best loosely be termed African values. We use the term 'African values' in a very circumspect manner, since we are quite aware of the dangers of generalization and stereotyping, but again, this relates to depicting and thus defining concepts in terms of the FoR of the target user. Instead of the usual nuclear family consisting of a mother, father and their offspring, the family depicted in the NLU dictionary is the extended family, including the grandparents, which is often typical of African societies. Considering the South African reality, a family is sometimes child-headed, or headed by a grandmother; these are factors that should be considered by lexicographers working within an African environment.

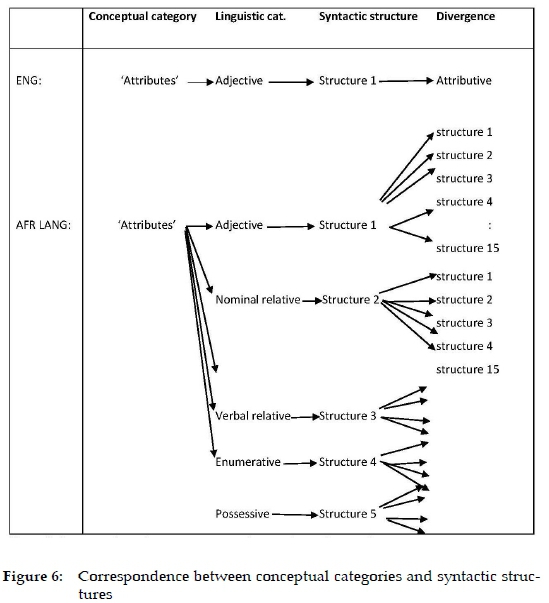

Dictionaries for African children should be much more than dubbed over versions of dictionaries initially conceptualized for English- (or Afrikaans-) speaking target users. African language lexicographers are all too often relegated to the role of translator. They are presented with a lemma list, and a preconceived dictionary layout and dictionary structure as a fait accompli. Lexicographers are then tasked with the provision of translation equivalents of the lemmas and also with the translation of, for example, definitions and usage examples, with very little regard to the challenges characteristic of African language lexicography. The remark by Gouws et al. (2014: 26) suggests that this was the case for the MML dictionaries: "MML realised the need for a dictionary directed at the specific needs and usage situation of South African foundation phase learners. This publishing house already had a monolingual English dictionary for first-language foundation phase learners, and a decision was made to embark on a series of foundation phase dictionaries for the other official South African languages, resulting in the current series of dictionaries". It would seem that the existing monolingual English dictionary was used as a blueprint for the bilingual dictionaries in the series. Although a pragmatic and efficient procedure with regard to time and money, such an approach does not always work to the advantage of African language dictionaries, the reason being that the whole conceptualization of the dictionary is based on a non-African language and a non-African epistemology. Such a practice can result in a mismatch between conceptual relationships and (linguistic) form and function. This is especially relevant in children's dictionaries, where the emphasis is on the establishment of conceptual relationships. The conceptual category 'attributes' is a case in point. In English, there is a one-to-one correspondence between the conceptual category 'attributes', the linguistic category 'adjective', and the syntactic structure used to express these concepts. In the African languages, however, there is a one-to-many correspondence between the conceptual category 'attributes' and the linguistic categories that are used as nominal descriptors. Attributes in African languages are expressed by a number of different constructions - some attributes are expressed by means of adjectives (lebone le lehubedu 'red light'), some by means of so-called possessive constructions (ngwana wa boomo 'headstrong child') or nominal relatives (ngwana yo boomo 'headstrong child'), and others by means of verbal relative constructions (meetse a a elago 'flowing water'). Furthermore, due to the complex system of concordial agreement in the African languages, each syntactic structure can diverge into potentially 15 structures, depending on the noun that is being described. Compare the following diagram:

Whereas the concept 'red', for example, is expressed by means of the attributive use of the adjective in English, in Sepedi, this concept can be expressed as wo mohubedu, se sehubedu, le lehubedu, a mahubedu and ye khubedu, depending on the object which is described as being red. In cases such as these, the lexicographer needs to give additional guidance to the African language user, to compensate for the conceptual mismatch. This additional guidance could be by means of providing usage examples.

Matching concepts to pictures, matching pictures to lemmas

With regard to the use of illustrations in dictionaries in general, Gouws (2014: 164, 165) emphasises that illustrations must be functional, i.e. they must assist the user with the retrieval of (semantic) information; if not, they are non-functional, and can have a cosmetic function at best. The most important function of illustrations is therefore supporting verbal descriptions.

The illustrations in children's dictionaries are different to ostensive definitions in so-called illustrated dictionaries because of the onomasiological nature of children's dictionaries. An onomasiological approach implies that the point of departure is the concept, which is represented by the lemma as a linguistic sign and visually illustrated by means of a picture or illustration. The illustration therefore forms an integral part of the treatment of the lemma since it is the only element providing additional semantic information. The underlying assumption in the compilation of children's dictionaries is that the user - being pre-literate or early literate - will move from the illustration to the lemma. According to Gouws et al. (2014: 30), seeing the picture and word together allows users to make the necessary link between the concept as represented by the picture, and the relevant word. The illustration is probably the first point of entry for the user, specifically for pre-literate and early literate users. Only in cases where the user has already attained some level of literacy does it become possible to use the lemma as the guiding element or first point of entry. In such cases, the illustration serves as a support for the definition and/or example material.

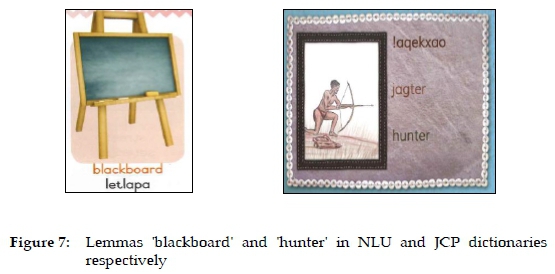

In the NLU and JCP dictionaries, verbal descriptions are quite sparse, consisting of a single lemma and its translation equivalent(s) only. In these cases, the illustration is the primary element in providing additional semantic information. Compare the treatment of the lemmas 'blackboard' (letlapa) and 'hunter' (!aqekxao) in the NLU (Northern Sotho-English) and JCP dictionaries respectively:

In the MML dictionaries, where definitions and example sentences are given, illustrations are additional support mechanisms and should be aligned with and confirm the information provided in the contents of these data categories. In the alphabetical lemma list of the MML dictionary, definitions are provided in the target language, followed by a usage example and its translation in English. Compare the treatment of the lemma 'snake' (noga) in the Northern Sotho-English dictionary:

In this example, the picture of the snake confirms the information given in the definition: a snake is a long, thin animal and does not have feet.

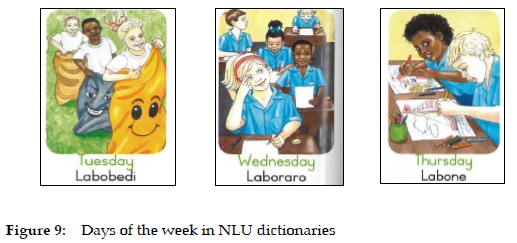

It is important that the illustration is a clear and unambiguous representation of the relevant concept, i.e. that the link between the concept and the illustration is clear, otherwise the illustration is non-functional. Compare the following examples from the NLU dictionary in which the days of the week are treated:

The functionality of these illustrations is questionable. For example, the illustration of the lemma Labobedi 'Tuesday' does not provide users with additional semantic information that would enable them to distinguish Tuesday from the other weekdays. Lexicographers would do well to follow the accepted lexicographic practice of defining the days of the week in terms of days that precede or follow a particular day, and find an innovative way to visually represent this. Having a picture of a calendar and indicating the days in relation to each other would be more functional. The utilization of the same illustrations for different, non-related concepts is a further indication that these particular illustrations may not be functional. The illustration used for Thursday, for example, is also used elsewhere in the same dictionary to illustrate the verb itlwaetsa 'practice'; the illustration for Wednesday is used to illustrate the verb soma 'work'. In the latter instances, the functionality of the illustrations is also doubtful.

Apart from the overarching function of illustrations of supporting verbal descriptions, a number of functions specifically relevant for children's dictionaries can be identified. In the first instance, illustrations should contribute to the cognitive development of the user, cf. Putter (1999: 92) in this regard. The thematic ordering of lemmas lays the basis for the establishment of semantic networks. Concepts that are semantically related can be presented in the same visual space, and illustrations can be utilized to highlight the distinguishing features of each concept. Differences and similarities between different concepts related to a specific semantic category can be illustrated. Compare the following examples of different animal tracks, categorized under the theme 'hunting' from the JCP dictionary:

The illustrations provide the user with enough information to distinguish cog-nitively between the tracks of a lion, a gemsbok and a giraffe. These lemmas, however, are treated on different pages, even though they belong to the same theme. Providing them on the same page would have strengthened the cognitive links between these concepts and would have made the similarities and differences immediately visually evident to the user.

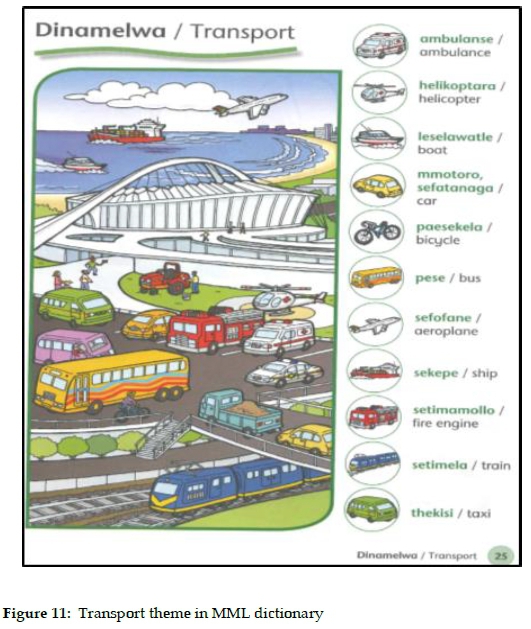

The thematic pages of the MML dictionaries have the added advantage that related concepts are represented within a context and in the same visual space, thus visually supporting the relatedness of the concepts. Compare in this regard the theme on transport in the Northern Sotho-English dictionary:

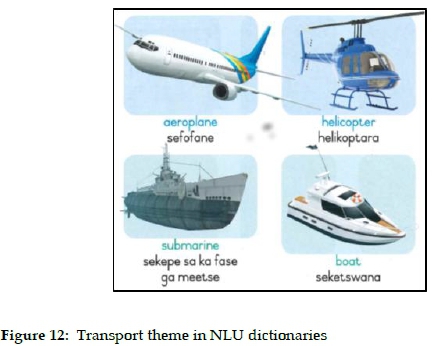

The representation of different kinds of vehicles within the same space assists users in identifying the similarities and differences between related concepts at a glance: a train is a vehicle that travels on a track, an aeroplane flies in the air, and boats float on water. Although related concepts are treated on the same page in the NLU dictionaries, each lemma and its accompanying illustration is provided without any bigger context. In cases such as these the illustration usually depicts the prototypical member of a class of objects, cf. Putter (1999: 85). Note that the background of each individual illustration is neutral and does not provide any additional visual information that could supplement the semantic information.

A second function of illustrations in children's dictionaries is to expand the user's experiential world, cf. Putter (1999: 99). She argues that users are exposed to illustrations of objects that do not form part of their frame of reference, and by internalizing these concepts, their FoR is expanded. Although we agree in principle, in terms of the discussion regarding the importance of establishing the FoR of the target user during the planning phase, we argue that a balance must be struck between what target users are familiar with and to which they can relate, and exposure to concepts with which they are (still) unfamiliar. A dictionary that limits users' exposure to new concepts by presenting them only with illustrations of objects that fall within their FoR will fail to meet their cognitive needs in that it does not offer users the opportunity to expand their FoR by internalizing new concepts. On the other hand, overwhelming users with illustrations of concepts that are foreign to their FoR can be equally negative. Although Gouws and Tarp (2017) focus their discussion of lexicographic information and data overload on e-dictionaries, we believe that their views can also be applied to paper dictionaries. Furthermore, whereas they use the term 'data overload' to refer to the provision of superfluous data within a dictionary article, we would argue for a more general interpretation of the term, i.e. that any element of the dictionary, be it on the microstructural or macrostructural level, can overload the user with data. Confronting users of a children's dictionary with too much (visual) information that falls outside of their FoR amounts to information overload. According to Speier et al. (as cited by Gouws and Tarp 2017: 395), "information overload occurs when the amount of input to a system exceeds its processing capacity". When taking into consideration the level of cognitive development of the target user of the dictionaries under discussion, flooding them with illustrations of too many foreign concepts increases the cognitive load on the user. Not only do they have to internalize the new concept, they also have to make the link to the lemma as the linguistic sign representing the concept. This could alienate users from the dictionary, and have a negative effect on sustained dictionary use and the establishment of a culture of dictionary use.

It is against this background that one could question the inclusion of a number of lemmas and their accompanying illustrations in the NLU dictionaries. In the thematic section of sport, for example, the lemmas 'skiing', 'ice skating' and 'fencing' are treated, and in the section on entertainment, the lemmas 'piano', 'saxophone' and 'movie, film' appear - the concept 'piano' being illustrated by means of a picture of a grand piano.3 Of course, this relates to the issue of lemma selection - if the visual representation of a particular concept falls outside the FoR of the user, it is probable that the concept itself falls outside the FoR. The lexicographer therefore needs to consider whether a specific concept forms part of the lived experience of a learner in the Foundation Phase and whether the inclusion of such a lemma is justified. One cannot help but question the inclusion of lemmas such as 'urchin', 'barnacle', 'plankton', 'sloth' and 'reindeer' - to name but a few - in the NLU dictionaries.

Lexicographers should furthermore consider including lemmas representing concepts that may be specific to the FoR of speakers of a specific language. African languages in South Africa mostly have a strong regional basis; consequently, certain concepts with which, for example, a Sepedi speaker may be familiar will be outside the FoR of a Sesotho speaker, and vice versa.4 Consider, for example, concepts such as masotsa 'mopani worms' and lerula 'marula fruit' which may represent everyday objects to a Sepedi speaker, but with which a Sesotho speaker may be unfamiliar. This would be true for names of plants, animals, birds etc. that are endemic to a particular geographical area. One could imagine that the Xhosa-English dictionary would need to include the names of and accompanying illustrations of common fish species, but that the Tswana-English dictionary in the same series would find the inclusion of such lemmas redundant, since they fall outside the FoR of many young Tswana speakers. The same argument would hold for cultural concepts that are particular to a specific culture and/or language group.

Possible guidelines for illustrations in children's dictionaries

Considering the very specific function of illustrations in children's dictionaries, it is important that these illustrations are designed in collaboration with lexicographers, a point already raised by Gouws et al. (2014: 37). Illustrations in a children's dictionary are different from illustrations in general children's literature, since they are lexicographic devices that function as guiding elements in the dictionary article. The following could be considered as guidelines for selection of illustrations that are functional as lexicographic devices.

Factual correctness

Care must be taken that an illustration is a factually correct representation of a particular concept as signified by the lemma. If there is a mismatch between the concept, the lemma and its illustration, the cognitive information that is presented to the user will be incorrect. In the NLU dictionaries, there are quite a number of lemmas where there is a mismatch between the concept, the lemma and the visual representation. In the thematic section on Entertainment, the lemma 'violin' is treated, but the illustration is that of a cello. In the English-Sepedi version, the English lemmas are mostly aligned with the illustrations, but there are instances of a mismatch between the Sepedi lemma and the illustration. The English lemma 'gemsbuck', for example, is correctly illustrated, but the Sepedi equivalent, i.e. phala refers to an impala. In the section on 'Different Homes', the lemma 'log cabin' appears. The lexicographer/translator may have been unfamiliar with the concept of a log cabin, and misinterpreted the English lemma as referring to a cabin that can be locked. The concept of a log cabin was clearly outside of the FoR of the adult lexicographer, once again raising the issue of appropriate lemma selection for a children's dictionary.

Free from 'visual noise'

Illustrations must be free from 'visual noise', i.e. unnecessary and irrelevant detail that could potentially distract users from correctly identifying the concept that is represented by the illustration. Al-Kasimi (1977: 102) uses the term 'preciseness' in this regard: "The dictionary user's attention should be directed only to the feature of the pictorial illustration relevant to the desired concept". The simplicity of illustrations in the JCP dictionary are perhaps the most successful of the three dictionaries in terms of preciseness: there can be little doubt as to what concept the picture is illustrating, cf. the lemmas 'chicken' and 'kettle' in this regard:

Even so, there is always the possibility of interpretive difference, due to dictionary users' FORs being widely different.

In order to facilitate preciseness, lexicographers have at their disposal a variety of devices that can assist in focusing the user's attention on the feature that is relevant for functional illustration of the concept. These include arrows, colour cues to indicate the most important feature of the illustration, and position cues that, according to Al-Kasimi (1977: 102), imply that the most important portion of the picture should be placed either in the centre, or upper left part of the illustration.

A number of articles in the NLU dictionaries are less successful in this regard. Compare the illustrations for the lemmas 'tropic', 'grassland' and 'pond' in this regard.

In all three examples, the pictures are inadequate representations of the aforementioned concepts. In these examples, an animal is the foregrounded, focal element in the illustration, and the user's intention will likely be distracted by the prominence of the chimpanzee, zebra and duck in the three examples respectively. The illustrations therefore do not adequately support the verbal information provided in the article, since they are open to dual and/or incorrect interpretation.

Free from stereotyping

Saying that children are impressionable beings is stating the obvious. Nevertheless, lexicographers who plan and eventually compile dictionaries with children as target users must be extremely sensitive to enforcing, sometimes inadvertently, any kind of stereotype, be it gender, racial or cultural stereotyping. Depicting the school principal as male and the teacher as female, using male figures to illustrate occupations such as those of engineer, lawyer, dentist, accountant and optometrist entrenches the perception that these occupations belong to the domain of males. In an attempt to circumvent stereotypical depiction of occupations, the NLU dictionaries use figures that are supposed to be gender neutral; however, their attempts at gender neutrality are scuppered by the fact that these figures display distinctly male characteristics - they are all depicted wearing ties. The only figure that is unmistakeably female - dressed in high heels and a flowery dress - is the picture used to illustrate the concept of shopping. For the compilers of the JCP dictionary, avoiding gender stereotyping must have posed a serious challenge, since gender roles are extremely strongly embedded in the cultural community of the Ju|'hansi speakers: men are hunters and women are gatherers. Depicting a hunter as female and someone gathering food from the veld as male would negatively affect the credibility of the cognitive information offered by the dictionary. The lexicographer therefore had no choice but to stick to the gender-based roles in preparing illustrations for the concepts 'hunter' and 'gatherer'.

Illustrating the un-illustratable

Gouws et al. (2014: 37) state categorically that it is not necessary for all lemmas in a children's dictionary to be illustrated with pictures, since some concepts can simply not be illustrated. If an illustration does not contribute to better understanding of the concept being illustrated, it becomes redundant and can even create confusion on the part of the user. The lexicographer should not fall into the trap of trying to include an illustration in each and every dictionary article, simply for the sake of using an illustration. Illustrations are lexicographic devices, therefore the decision as to the inclusion or exclusion of an illustration, the nature of the illustration and its placement should be a cooperative effort of both publisher and lexicographer, and both role players must consider the functionality of all illustrations. Lexicographers should look for innovative alternatives to provide additional semantic information for concepts that are difficult to illustrate due to their abstract nature or for another reason, cf. concepts such as 'manners', 'obedient', 'lazy', 'respect', etc. (cf. the NLU dictionaries' articles in this regard). A further consideration, specifically in the case of dictionaries aimed at children in the foundation phase, should be whether such a concept is indeed relevant in a foundation phase dictionary.

Conclusion

Dictionaries for children speaking an African language should be much more than beautifully illustrated picture books. Their conceptualization and subsequent compilation should be based on sound theoretical principles, as is the case for dictionaries compiled for adult users. In terms of Gouws et al. (2014), they should maintain a sound balance between the selection of the terms, the extent of the treatment, the detail of the distinction, and the target user's skills and existing knowledge. Conceptualization of these dictionaries should be a bottom-up process, calling for a collaborative effort between the target user, the lexicographer, the publisher, educational experts, illustrators and graphic designers. In their design and compilation, the currently available dictionaries for South African children have not yet made the paradigm shift from a Eurocentric to an Afrocentric approach.

Acknowledgements

Financial support by (a) the South African Centre for Digital Language Resources (SADiLaR) and (b) the National Research Foundation of South Africa (Grant specific unique reference numbers 85763 and 103898) is hereby acknowledged. The Grantholders acknowledge that opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in any publication generated by the NRF supported research are those of the authors, and that the sponsors accept no liability whatsoever in this regard.

Bibliography

Dictionaries

Jones, K. and Cwi, T.F. 2014. Ju/'hoan Tsumkwe Dialect/Prentewoordeboek vir kinders/Children's Picture Dictionary. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press. [ Links ]

Mabule, M. 2010. Longman Pukuntsu ya sehlopafase: Sepedi/English. Cape Town: Maskew Miller Longman. [ Links ]

Mojela, V.M. (Ed.). 2018. Picture Dictionary: English-Sesotho sa Leboa. Gr R-3: The Official English-Sesotho sa Leboa Foundation Phase CAPS-linked Illustrated Dictionary of the Government of the Republic of South Africa. South Africa: Sesotho sa Leboa National Lexicography Unit.

Paizee, D. (Ed.). 2008. Oxford First Bilingual Dictionary. Setswana + English. Cape Town: Oxford University Press Southern Africa. [ Links ]

Other

Al-Kasimi, A.M. 1977. Linguistics and Bilingual Dictionaries. Leiden: E.J. Brill. [ Links ]

Beyer, H.L. 2014. Explaining Dysfunctional Effects of Lexicographical Communication. Lexikos 24: 36-74. [ Links ]

Cianciolo, Patricia J. 1981. Picture Books for Children. Second edition. Chicago: American Library Association. [ Links ]

Cignoni, L., E. Lanzetta, L. Pecchia and G. Turrini. 1996. Children's Aid to a Children's Dictionary. Gellerstam, M. et al. (Eds.). 1996. EURALEX '96 Proceedings I-II, Papers Submitted to the Seventh EURALEX International Congress on Lexicography in Göteborg, Sweden: 659-666. Gothenburg: Department of Swedish, Göteborg University. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. 2007. On the Development of Bilingual Dictionaries in South Africa: Aspects of Dictionary Culture and Government Policy. International Journal of Lexicography 20(3): 313-327. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. 2013. Establishing and Developing a Dictionary Culture for Specialised Lexicography. Jesensek, V. (Ed.). 2013. Specialised Lexicography. Print and Digital, Specialised Dictionaries, Databases: 51-62. Lexicographica Series Maior 144. Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. 2014. Expanding the Notion of Addressing Relations. Lexicography: Journal of ASIALEX 1(2): 159-184. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. 2016. Enkele minder bekende Afrikaanse woordeboekmonumente (A Few Lesser Known Afrikaans Dictionary Monuments). Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskapppe 56(2-1): 355-370. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. and D.J. Prinsloo. 2005. Principles and Practice of South African Lexicography. Stellenbosch: SUN PReSS, AFRICAN SUN MeDIA. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H., D.J. Prinsloo and M. Dlali. 2014. A Series of Foundation Phase Dictionaries for a Multilingual Environment. Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics 43: 23-43. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. and S. Tarp. 2017. Information Overload and Data Overload in Lexicography. International Journal of Lexicography 30(4): 389-415. [ Links ]

Prah, K.K. 2007. Challenges to the Promotion of Indigenous Languages in South Africa. Retrieved from http://www.casas.co.za.

Prinsloo, D.J. 2017. Analyzing Words as a Social Enterprise: Lexicography in Africa with Specific Reference to South Africa. Miller, J. (Ed.). 2017. Analysing Words as a Social Enterprise: Celebrating 40 Years of the 1975 Helsinki Declaration on Lexicography. Collected Papers from AustraLex 2015: 42-59. https://www.adelaide.edu.au/australex/publications/.

Putter, A.-M. 1999. Verklaringsmeganismes in kinderwoordeboeke. Unpublished M.A. Dissertation. Potchefstroom: Potchefstroom University for Christian Higher Education. [ Links ]

Tarp, S. 2011. Pedagogical Lexicography: Towards a New and Strict Typology Corresponding to the Present State-of-the-Art. Lexikos 21: 217-231. [ Links ]

Webb, V. 1999. Multilingualism in Democratic South Africa: The Over-estimation of Language Policy. International Journal of Educational Development 19: 351-366. [ Links ]

1. We acknowledge that a not insignificant number of learners, especially in metropolitan, urban areas attend schools in which the language taught as home language, is not the learner's actual home language. This is especially the case in areas which are linguistically diverse.

2. Statistics provided by the Department of Basic Education in personal e-mail.

3. We do acknowledge that our view on these concepts being outside the FoR of the target user may be subjective and to some extent intuitive, and fully agree that an empirical study is necessary to ascertain whether this is indeed the case.

4. Gauteng would be a notable exception to the regionality of the South African languages, being a province where speakers of many different languages live side by side.