Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Lexikos

versão On-line ISSN 2224-0039

versão impressa ISSN 1684-4904

Lexikos vol.29 Stellenbosch 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.5788/29-1-1514

ARTICLES

Theoretical and Practical Reflections on Specialized Lexicography in African Languages*

Teoretiese en praktiese gedagtes oor die gespesialiseerde lek-sikografie in Afrikatale

Dion Nkomo

School of Languages and Literatures: African Language Studies, Rhodes University, Makhanda (Grahamstown), South Africa (d.nkomo@ru.ac.za)

ABSTRACT

In this article, reflections are made on some specialized lexicographical/termino-graphical resources being produced in African languages. The resources are produced in order to contribute towards the intellectualization of those languages for expanded functional usage. The article focuses on lemma selection, provision of data/information for included lemmata and structural aspects of the surveyed resources. With regard to the first area of focus, the article identifies the lack of a systematic approach to lemma selection, which undermines the potential of the resources as communicative and cognitive tools in specialized subject fields and disciplines. Secondly, regarding the provision of data categories, instances of insufficient information and cases of inclusion of irrelevant information are identified, both of which have implications for the functional value of the resources within specialized domains. Finally, reflections on aspects of dictionary structure indicate sub-standard structural designs which affect the user-friendliness of the resources, but some innovative structural designs are also identified. Overall, the article argues for a stronger lexicographic orientation in terms of the theoretical underpinnings guiding the production of specialized lexicographical/terminographical resources in African languages.

Keywords: specialized lexicography, terminography, african languages, intellectualization of african languages, lemma selection, african lexicography, terminology, terminography

OPSOMMING

In hierdie artikel word gedagtes oor sommige gespesialiseerde leksi-kografiese / terminografiese hulpbronne wat in Afrikatale saamgestel word, weergegee. Dié hulpbronne word geskep om 'n bydrae te lewer tot die intellektualisering van hierdie tale vir uitgebreide funk-sionele gebruik. Daar word gefokus op lemmaseleksie, op die verskaffing van data/inligting vir die lemmas wat ingesluit is en op strukturele aspekte van die hulpbronne wat ondersoek is. In die artikel word daar met betrekking tot die eerste fokusarea 'n gebrek aan 'n sistematiese benadering tot lemmaseleksie geïdentifiseer wat die moontlikhede van die hulpbronne as kommunikatiewe en kognitiewe hulpmiddels in gespesialiseerde onderwerpsvelde en dissiplines beperk. Tweedens word, met verwysing na die aanduiding van datakategorieë, gevalle van onvoldoende inligting en gevalle van insluiting van irrelevante inligting geïdentifiseer wat albei implikasies vir die funksio-nele waarde van die hulpbronne binne gespesialiseerde domeine inhou. Laastens dui gedagtes oor aspekte van woordeboekstruktuur op substandaard strukturele ontwerpe wat die gebruikersvrien-delikheid van die hulpbronne beïnvloed, maar sommige innoverende strukturele ontwerpe word ook geïdentifiseer. In die geheel beskou, word in hierdie artikel gepleit vir 'n strenger leksikogra-fiese orientëring in terme van die teoretiese basis wat die skep van gespesialiseerde leksikografiese/ terminografiese hulpbronne in Afrikatale rig.

Sleutelwoorde: gespesialiseerde leksikografie, terminografie, afrikatale, intellektualisering van afrikatale, lemmaseleksie, afrika-leksikografie, terminologie, terminografie

1. Introduction

Language policies and language planning efforts seeking to develop and promote the continent's indigenous African languages that were marginalized during the colonial era and the apartheid era in south Africa have culminated in the proliferation of lexicographical resources focusing on specialized academic and professional disciplines. Examples include specialized dictionaries in the fields of biology, linguistics, literature, medicine and music produced under the auspices of the African Languages Research Institute (ALRI) in Zimbabwe. In South Africa, the Department of Arts and Culture (DAC), the National Lexicography Units (NLUs), commercial publishers, institutions of higher education and other organisations have made significant contributions. Appearing in different sizes, formats and mediums, whether all those resources are fit to be called dictionaries is a debate that emerges from their compilers and users alike. For example, in the first volume of Understanding Concepts in Mathematics and Science - A Multilingual Learning and Teaching Resource Book in English, IsiXhosa, IsiZulu and Afrikaans, henceforth Understanding Concepts in Mathematics and Science, Young et al. (2005: viii) make a strong disclaimer that:

This is a resource book, not a textbook. It is also not a dictionary, nor a teaching method book. It should thus be always used together with approved classroom teaching and learning materials (present author emphasis).

There are numerous resources whose compilers appear to be in a dilemma of both attraction and repulsion by the term dictionary, in a manner that is reminiscent of what Landau (1984: 6) said about the power of the term dictionary. On the one hand, such power tends to elevate the status of some reference works that are called dictionaries, thereby making them successful and popular among users. On the other hand, it causes other resources to be judged harshly when they are called dictionaries but then fail to satisfy certain criteria commonly associated with dictionaries. Consequently, some compilers play it safe by calling their products by several other names instead of dictionaries. What is remarkably common among the studied resources is that, through their titles and/or subtitles, front matter or blurb texts, they identify specific cognitive and communicative lexicographic functions that they seek to achieve, and their overarching endeavour to contribute to the intellectualization of African languages. Broadly speaking, they can comfortably be accounted for in Bergen-holtz and Nielsen's (2006) inclusive disciplinary conceptualization of specialized lexicography, even though some of their compilers would prefer to call them otherwise, e.g. terminology products. It is for this reason that this article adopts a seemingly indecisive use of specialized lexicographical/terminographical resources. Tarp (2000: 214) is quite critical of scholars who consider specialized lexicography as something different from lexicography in general (which is the case with some terminographers). Lukasik (2016) even prefers to use the term 'pedagogical terminographers' to refer to compilers of specialized pedagogical dictionaries.

This article offers a theoretical engagement with an assortment of products whose production constitutes an integral aspect of the intellectualization of African languages for purposes of expanding their functional spaces (Kaschula and Nkomo 2019). The article illustrates how different compilers seek to contribute to this endeavour by identifying and analyzing the specific functions of some of the products. The development, documentation and description of terminology in these resources are regarded as central to the intellectualization of African languages, and the significance and potential of such works cannot be overemphasized. Hence the need to subject them to critical reflections.

While reflecting on the surveyed resources, this article argues for a stronger lexicographic orientation in terms of the theoretical underpinnings guiding their production. Weak theoretical foundations compromise the utility value of some of the products. This is particularly the case regarding lemma selection, as illustrated in Section 4. The article observes that in their lemma selection, some compilers lack systematic approaches that are appropriate for specialized lexicography. Beyond lemma selection, the analysis is extended to the provision of data categories in some of the studied lexicographic resources, identifying instances of insufficient information and cases of inclusion of irrelevant information. This is done in Section 5. Finally, reflections are made on some aspects of dictionary structure in Section 6, focusing on sub-standard structural designs and innovative structural designs. However, before getting into those core sections, the article provides some context in Section 2 by giving a brief overview of lexicography in African languages, following by a quick survey of specialized lexicography in Section 3. Concluding remarks are made in Section 7.

2. An overview of lexicography in African languages

Situating specialized lexicography in African languages within a broader historical context of African lexicography enables an appreciation of the vital role that specialized dictionaries could play in solving communication and cognitive problems facing African societies and the challenges confronting this branch of lexicography (Gouws 2013; Nkomo 2010). Gouws (2013: 52) observes that:

Too many metalexicographers were only concerned with general language dictionaries ... This lack of concern with LSP dictionaries led in far too many cases to LSP dictionaries not really qualifying as dictionaries but merely playing an inferior role as word lists or other restricted (and often handicapped) reference products.

As general language dictionaries have claimed most of the attention of historical dictionary research, the needs of diverse user groups regarding specialized subject knowledge and languages used in different disciplines and professions have been neglected. Efforts of addressing such needs have quite often lacked theoretical insights, resulting in what Tarp (2012) aptly describes as a slow-motion development of this branch of lexicography, especially in terms of the quality of dictionaries produced.

At least four types of dictionaries, albeit not mutually exclusive, may be identified in the lexicography of African languages from a historical perspective. Firstly, lexicography in African languages began with bilingual dictionaries pairing African languages with more powerful European languages like English produced by early missionaries to support their learning of African languages for evangelization purposes (Gouws 2007; Nkomo 2018). Dictionaries such as Kropf's (1899) Kafir-English Dictionary in isiXhosa and Hannan's (1959) Standard Shona Dictionary contributed to the codification and standardization of those African languages, thereby laying foundations for further intellectualization and use of the languages in standardized forms (Gouws 2007).

Secondly, monolingual dictionaries would follow to consolidate the position of African languages as either official or national languages. This is typically seen in post-apartheid South Africa where National Lexicography Units were established with their main function being the production of comprehensive general purpose dictionaries in the country's eleven official languages. These types of dictionaries are generally expected to further contribute to the standardization of the languages, allowing them to function authoritatively in their own right, without reference to the more powerful languages such as English. Simango (2009) refers to this as 'weaning Africa from the Europe', which suggests an ideological endeavor of linguistic decolonization.

Thirdly, especially in South Africa, the language-in-education policy which seeks to cultivate multilingualism in education incentivized the production of bilingual and multilingual school dictionaries mainly by commercial publishers such as Oxford University Press - Southern Africa, Maskew-Miller Longman and Pharos. For example, Oxford University Press - Southern Africa has over recent years produced a series of bilingual school dictionaries pairing English with languages such as isiZulu, isiXhosa and Sesotho sa Leboa.

The NLUs have also produced school dictionaries including a recent series of foundation phase picture dictionaries (see Taljard and Prinsloo 2019).

Lastly, although not a distinct category, as some of them fall under school dictionaries, specialized dictionaries have also gained significant attention linked to the endeavour of using indigenous official languages in specialized academic and professional disciplines. Just like general-purpose monolingual dictionaries in African languages, specialized dictionaries also seek to enhance and affirm the potency of languages in the post-colonial dispensation of the continent. The remainder of this article reflects on this category of dictionaries in African languages.

3. Specialized lexicographical and terminographical resources in African languages

In line with Gouws (2007) and Nkomo (2018) who underscore the interface between lexicography and language policy, this section offers a brief survey of specialized lexicographical and terminographical resources within the language policy environments of South Africa and Zimbabwe. South Africa arguably stands out in terms of an explicit lexicographical/terminographical and language policy interface. The post-apartheid legislative framework, central to which is the constitutional proclamation of the nine indigenous languages as official languages, as well as the imperative that they must be treated with parity alongside Afrikaans and English, had a catalytic effect on lexicography and terminology in African languages. At the level of basic education, the Language-in-Education Policy (LiEP), adopted in 1997, acknowledges "the cognitive benefits ... of teaching through one's medium (home language)". The cognitive challenges associated with the use of a language that learners are not proficient in are intricately linked to communicative problems, hence the LiEP's commitment to "the development of official languages" in order "to counter disadvantages resulting from different kinds of mismatches between home languages and languages of learning and teaching". It is in the context of such a legislative and policy framework that the majority of specialized lexicographical products have been developed in the African languages of South Africa. Most of them have been targeted at learners. This is consistent with Lukasik's (2016: 211) assertion that "one of the most important function of specialised dictionaries is the pedagogical (didactic) function". This is also captured in Fuertes-Olivera's (2010) edited volume entitled Specialised Pedagogical Lexicography for Learners. As one of the key role-players in the field of terminography in South Africa, the DAC has devoted significant attention to the "Schools Project" which is dedicated to the "documentation of existing terminology, and facilitation of the development of terminology in the African languages for new concepts that appear in the teaching materials for Grades 1 to 6" (DAC 2013a: v). This has resulted in the publication of the following series of multilingual resources:

- Multilingual Financial Terminology List

- Multilingual Human, Social, Economic and Management Sciences Terminology List

- Multilingual Natural Sciences and Technology Term List (SeSotho)

- Multilingual Natural Sciences and Technology Term List (Tshivenda-Xitshonga)

- Multilingual Natural Sciences and Technology Term List (Nguni)

- Multilingual Mathematics Dictionary: Grade R-6

- Multilingual HIV/Aids Terminology

- Multilingual Soccer Terminology List

The needs facing the education sector have also inspired other projects such as the Concept Literacy Project, leading to the publication of two concept literacy resource books for Mathematics and Science by Young et al. (2005; 2009). Organizations such as the Project for the Study of Alternative Education in South Africa (PRAESA) and the Human Sciences Research Council (HRSC), among others have also made notable contributions in terms of specialized lexico-graphical/terminographical work. Even the National Lexicography Units (NLUs) find themselves compelled to move beyond their primary function of producing comprehensive general-purpose monolingual dictionaries to produce dictionaries such as Isichazi-magama seMathematika neNzululwazi, an isiXhosa Mathematics and Science dictionary for primary schools produced by the IsiXhosa National Lexicography Unit. What is perhaps more remarkable is that some of these resources have been published by commercial publishers who were previously too cautious if not skeptical to publish material in African languages due to limited market demand. Maskew Miller Longman's Longman Multilingual Maths Dictionary for South African Schools: English, isiXhosa, Afrikaans and Cambridge University Press's Isichazi-magama seziBalo Sezikolo saseCam-bridge are examples that illustrate an attitude change by commercial publishers towards African languages dictionaries.

Universities have also responded to pedagogical challenges connected to the language barrier in South African higher education by developing, documenting and describing terminology in African languages (Nkomo and Madiba 2011). The Language Policy for Higher Education and the Ministerial Report on the Use of Indigenous Languages in Higher Education expanded the potential functional space for African languages and the need for their development in higher education. The latter explicitly mandated each institution to identify specific African language(s) that they would promote and develop for academic purposes. Terminology work focusing on isiXhosa at Stellenbosch University and isiZulu at the University of KwaZulu-Natal illustrate commitment to such a mandate.

Lukasik (2016: 212) aptly states that "the role of ... [specialized lexico-graphical/terminographical works] as carriers of specialized knowledge renders them indispensable tools in maintaining the flow of professional information". As such, terminographical works have also been produced for other types of users, who include professionals in various subjects and translators.

The Use of Official Languages Act compels government departments and state entities to choose and use at least three official languages with parity, which means that their services should be available in all the chosen languages. This requires the departments to translate their key policies, plans and reports into African languages. It is against this backdrop that the DAC's Multilingual Financial Terminology (DAC 2013b), Multilingual HIV Terminology (DAC 2013c) as well as the Multilingual Parliamentary/Political Terminology (DAC 2013d) lists become relevant. The legislative framework makes it imperative that termino-graphical tools and resources are developed to address communicative problems associated with the underdevelopment of the languages in South Africa.

The Zimbabwean legislative environment that inspired lexicographic activities from the 1990s has been slightly different from that of South Africa in that Zimbabwe did not have an overt language policy document until 2013. However, similar ideological aspirations regarding lexicography and the intellectualization of African languages have been obvious. For example, at the University of Zimbabwe, ALRI was established with a clear mission: To research and document the Zimbabwean languages in order to expand their use in all spheres of life. The expansion of the use of Zimbabwean languages in all spheres of life was envisaged to be attainable through mainly specialized lexicography. In the master plan of the African Languages Lexical (ALLEX) Project, which would be institutionalized in ALRI, several specialized dictionaries were listed as target outputs of the project. By the time the ALLEX Project ended, the following specialized dictionaries had been published:

- Duramazwi reDudziramutauro neUvharanomwe (a Shona dictionary of linguistic and literary terms)

- Durazwi remiMhanzi (a Shona dictionary of music terms)

- Isichazamazwi SesoMculo (a Ndebele dictionary of music terms)

- Duramazwi reUrapi neUtano (a Shona dictionary of biomedical terms)

These dictionaries were meant to support the infusion of Shona and Ndebele, the country's major indigenous languages, into the specialized domains that were mainly reserved for English. For example, English is the dominant language of teaching and learning in Zimbabwe across all educational levels. Advanced linguistic and literary studies in Shona and Ndebele continue to be conducted mainly through the medium of English since the early studies by colonial scholars. Hence the need for the specialized Duramazwi series in Shona and similar dictionaries in Ndebele, although progress could not be made in the latter beyond Isichazamazwi SesoMculo. Targeting student doctors and nurses, Duramazwi reUrapi neUtano notes on its blurb and introductory texts that because of their English-dominant academic and professional training, health-care providers cannot easily communicate with Zimbabweans who are not competent in English. It is such communication gaps and challenges between medical experts and their non-expert clientele that specialized lexicography in African languages can potentially address.

4. Lemma selection issues

Lemma selection decisions determine the typological distinction of specialized lexicographical resources from general-purpose dictionaries. While the latter may include lexical items with specialized disciplinary designations (Gouws 2013), they often label or mark them to indicate that they are not the default members of the word-list structure. This is clearly illustrated in Figure 1, a Screenshot of an article stretch leucine - leucoplast from the South African Concise Oxford Dictionary (SACOD) below:

Users of dictionaries such as SACOD are not always guaranteed to get assistance regarding specialized terminology or concepts from general-purpose dictionaries. On the other hand, specialized dictionaries are primarily consulted for information regarding language and concepts with specialized academic or professional designations. A law student or a legal practitioner will be more disappointed if they fail to find a specific legal term in a law dictionary than in a general-purpose dictionary.

As they were conceived to assist specific users regarding specific academic or professional disciplines and subject fields, lexicographical/terminological resources surveyed in the previous section are expected to describe the relevant terminology and concepts included as lemmata. The South African Mathematics and Science dictionaries compiled for learners and teachers clearly delineate their broad subjects (Mathematics and Science) as well as the specific sub-fields within those disciplines. Isichazi-magama seMathematika neNzululwazi indicates that its mathematics section explains concepts falling under algebra and geometry while the science section covers fauna, flora, matter, energy, change, earth and planets. The Longman Multilingual Maths Dictionary for South African Schools: English, isiXhosa, Afrikaans commits itself to responding to the national Mathematics curriculum.

According to Nielsen (1995), a systematic presentation of the subject fields covered by dictionaries is crucial for lemma selection. A detailed conceptual mapping of the subject-field and its sub-fields is necessary to ensure that relevant lexical items within the delineated scope are systematically included. Supposing that the compilers of the studied Mathematics and Science dictionaries judiciously included lexical items within the clearly delineated scopes, the dictionaries would be expected to complement other official curriculum materials like textbooks and workbooks to a greater effect. However, subject-field delineation and its systematic presentation may not be sufficient. Subsequent procedures of lexicographical description, including how the lemmata are defined, are equally important for the resources to be useful products of specialized lexicography.

Some resources developed to assist users with specialized linguistic and conceptual data are less helpful because they omit key terminology. While Lukasik (2016: 214) identifies the major shortcoming of specialized dictionaries to be a consequence of having "been constructed for 'everybody'", it is worth noting that far too often, they are also 'constructed by everybody'. This includes subject experts or lexicographers who over-rely on the former for advice on lemma candidates. While the input of subject experts remains indispensable in specialized lexicography, it should be solicited and utilized within clearly conceived lexicographical frameworks established by qualified lexicographers rather than over-relying on experts for lexicographical matters. Experts may be oblivious of the needs of non-expert users and take for granted some terms and concepts assuming that users know them, or even impose complex definitions and defining language to the detriment of users who may either fail to find some terms or struggle to comprehend their meanings. A survey conducted by Mawonga et al. (2014) to test a Political Philosophy Terminology resource whose list was compiled by a lecturer established that students could not find most of the terms that challenged them in their Political Science module offered at their university. Students experienced difficulties with more terms and concepts beyond what the lecturer considered to be difficult terms.

Compilers of some specialized lexicographical resources in African languages have adopted a commendable procedure of using specialized texts to circumvent the problem highlighted above. Specialized dictionaries for schools typically draw lemmata from the language used in curriculum documents, textbooks and assessment material. The Multilingual Parliamentary/Political Terminology List published by the DAC also illustrates this practice, having drawn its lemmata from Hansard reports (parliamentary debates); parliamentary proceedings (speeches, motions, notices of motions); parliamentary papers (order papers, minutes, announcements, tablings and committee reports) and legislation (Acts, Bills, government notices, proclamations and Gazettes) (DAC: 2013d: iii). With such diverse specialized texts dealing with the relevant specialized domains, it is possible to capture the key concepts and terms for inclusion. Using specialized texts as a form special corpora is therefore recommended (Bowker and Pearson 2002). Corpus query tools such as WordSmith Tools or Sketch Engine can enable lexicographers to identify lemma candidates and their keyness values with more efficiency and precision. However, special corpora may not be used exclusively given the limitations of special corpora when it comes to matters of size, representativeness and balance (Bowker and Pearson 2002). For example, despite the commendable use of Hansard reports (parliamentary debates); parliamentary proceedings (speeches, motions, notices of motions); parliamentary papers (order papers, minutes, announcements, tablings and committee reports) and legislation (Acts, Bills, government notices, proclamations and Gazettes) as a form of a special corpus to identify relevant parliamentary and political terminology, the DAC (2013d) resource does not include terms related to different types of democracy. While the user may get meaning information, including translation equivalents in ten languages for the English terms democracy, conciliatory democracy and consociational democracy, he/ she may get stuck regarding terms such as authoritarian democracy, direct democracy, presidential democracy, parliamentary democracy, participatory democracy and representative democracy. While such terms might not have appeared in any of the collected texts, an exploration of the conceptual structure of political science as a subject would have helped the compilers, working closely with the subject expert, to foresee that translators and language practitioners for whom the resource is developed may need those terms in the future. It is also possible that the terms could have been omitted due to manual or traditional term extraction from texts, which is inefficient.

Writing on theoretical challenges to practical specialized lexicography almost twenty years ago, Tarp (2000) ably demonstrated how a discussion of lemma inclusion or exclusion might become irrelevant. However, such discussions remain necessary as they stimulate theoretical reflections on lexicographic practice. The Shona music terms dictionary, Duramazwi RemiMhanzi, has included, described and illustrated diagrammatically as lemmata the following words: gamburabota (thumb), mungedzapenzi (index finger), mungedzazvose (index finger), munongedzo (index finger), mudapakati (middle finger), nhembayemwana (ring finger), kasiyanwa (little finger). The inclusion and lexicographical description of these finger names, three of which are synonyms for the index finger, needs to be interrogated, especially in view of the target users. A close analysis of the dictionary reveals that these lexical items also appear frequently in the explanations of lemmata referring to music instruments, especially how instruments are played or handled. For example, reference is made to middle fingers (minongedzo) in the explanation of the lemma madhebhe, a type of mbira. Therefore, what emerges to have been adopted is the principle that definitions should not use words that are not explained in the same dictionary. However, the relevance of such a principle is questionable in this dictionary, which is targeting mother-tongue speakers of Shona studying and teaching music at schools, colleges and universities. Given that the premise of compiling this dictionary is making music knowledge accessible to the target users in their mother tongue, the dictionary does not offer the relevant help as the definitions of such lexical items do not make explicit references to how the fingers referred to are useful in playing or handling specific instruments.

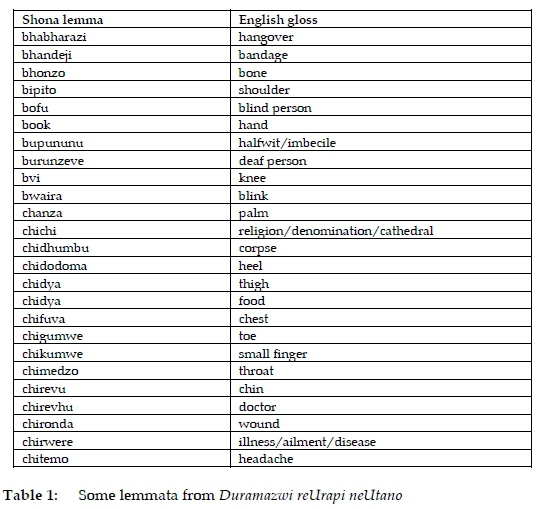

At the beginning of this section it was asserted that lemma selection decisions will, to a large extent determine whether the final product would be a specialized dictionary or general-purpose dictionary. As in the case of the music terms dictionary discussed above, one may indeed wonder about the inclusion of the twenty-five lemmata identified from the Shona biomedical terms dictionary listed in Table 1 below:

The twenty-five lemmata were identified from the first fifteen pages of the dictionary. Twelve of them refer to basic body parts like shoulder, hand, chin, palm, chest, heel, thing, etc. Some of the lemmata have multiple synonyms which are also entered and as separate lemmata. Seven lemmata have been entered with individual comprehensive treatment in the dictionary which however, includes general rather than specialized definitions. The target users of this dictionary are mother-tongue Shona-speaking medical student doctors and trainee nurses. Shona is taught as a compulsory language subject for Shona-speaking learners from the first grade to the General Certificate of Education: Ordinary Level after which students can train as nurses or future medical students may specialize in science subjects. The point is that the target users are mother-tongue speakers of the language who would have studied it for eleven years. One would wonder if they would not know such words for them to search for their general definitions, which may be looked up in a general dictionary, if needed, and whether there were no more unfamiliar lexical items from the biology and medical fields that could be accommodated.

While similar questions may be raised regarding some lemmata in the DAC's Multilingual Mathematics Dictionary: Grade R-6, the compilers seem to have thought deeply about such lexical items. The compilers write:

Mathematics is generally referred to as Numeracy Skills in Grades 1 to 3. In these grades a number of general terms such as match, choose, fill in, light, heavy etc. are included. To teach the learners about space and position many prepositions such as like, behind, on, under, etc. are included. Learners have to learn about measurements, capacity, height, weight, length, shapes, and patterns. In the context of Mathematics terms such as long, tall, wide, full, half-full and even cup (measurement: 250 ml) have a mathematical meaning, and are thus included in the list, although it might be argued that they are general words in other contexts.

In order to read the time on a clock the learners need to know that hand may be used to indicate the hand of a clock (long hand, short hand) and they learn that even a clock has a face. Learners also have to learn how to use a calculator. It is sometimes difficult to decide on the status (general words or subject specific terms) of lexical items in school texts, and that is why many terms used in teaching Mathematics at primary level are regarded to be ordinary words, but are nevertheless included in the glossary (DAC 2013a: v).

Such a theoretically-motivated lemma selection procedure needs to be considered in the compilation of specialized lexicographical/terminographical resources in African languages in order to improve their reliability as sources of specialized terminological and conceptual information. Furthermore, an appropriate lexicographical treatment of lemmata needs to accompany such a procedure in order to provide users with assistance that they would barely get from general dictionaries. This is discussed in the next section.

5. Lexicographical treatment of lemmata: Insufficient versus irrelevant information

While a well-conceived and diligently constructed lemma list will provide a solid foundation for a specialized dictionary, it will not automatically translate into an effective and user-friendly product. After locating the lexical item that prompts dictionary consultation, the user must find the relevant data type(s) from which the needed information may be retrieved. Thus the lexicographical treatment of included lemmata is another equally important theoretical decision with practical import. The retrievable information must be relevant, sufficient and accurate in order to address the question(s) that prompted the dictionary consultation procedure. Questions of relevance, adequacy and accuracy are therefore crucial in the analysis of the surveyed dictionaries.

5.1 Insufficient information

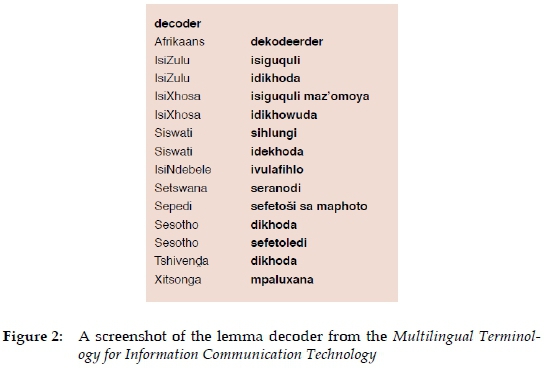

The problem of insufficient treatment of included lemmata is one notable weakness of African language lexicographical/terminographical resources that prevails more when compilers distance themselves, their practice and products from lexicography as a discipline. In some of the resources, the compilers avoid the term dictionary in their titles, opting instead for glossary, terminology or terminology list. As noted earlier, the term remarkably emerges in blurbs, forewords and other introductory texts, as illustrated by the resources produced by the Unit for IsiXhosa at Stellenbosch University's Language Centre, e.g. Isigama Somthetho / Law Terminology / Regsterminologie. Although the DAC products are clearly identified as dictionaries by their compilers, they offer the typically bare minimal treatment of the included terms as illustrated by the following screenshot (DAC 2013e) and can barely be described as more than terminology lists.

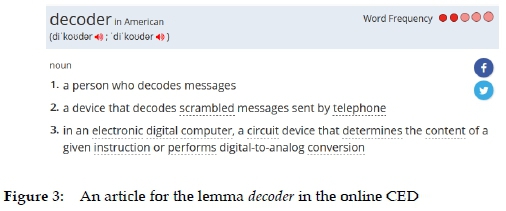

The screenshot illustrates the treatment of the term decoder in the Multilingual Terminology for Information Communication Technology, which is saved as a Multilingual ICT Dictionary. From this resource, the data that the user may access constitutes the translation equivalents in the other ten South African official languages. For some of the languages, two equivalents, a coinage and a transliterated borrowing, are provided. On the one hand, while the coinages may capture some properties of a decoder, they may not be easily understood by a mother-tongue speaker in terms of their specialized ICT designation, which lies somewhere between the three senses captured by the online Collins English Dictionary (CED) as follows:

The problem with some of the coinages is that despite appearing to be transparent and self-explanatory, they may not be unambiguous enough for one to easily determine which of the three special designations captured in the online CED they refer to. For example, the coined isiZulu term isiguquli may literally translate into 'that which changes or transforms something'. This could be a transformer, an electric device, which is not necessarily the same as a decoder, or it could be a person who transforms something. With the term not appearing in other isiZulu dictionaries, lack of additional information implies that the mother-tongue isiZulu speaker who is challenged because of limited or a lack of English competence does not necessarily benefit from this resource in his/ her quest for unambiguous communication and comprehension of the term. Newly coined terms in African languages will not be known to the majority members of the speech communities despite morphological appropriateness and what may appear to be semantic transparency. Therefore, while the preface of the Multilingual Terminology for Information Communication Technology states that "[T]o promote effective communication in these domains it is essential that terminology should be available for all the languages in these fields of knowledge" (DAC 2013e: v), it is clear that equivalent terminology alone is insufficient and that newly coined terms are not sufficiently explicit to independently facilitate unambiguous communication within the specialized disciplinary and subject fields.

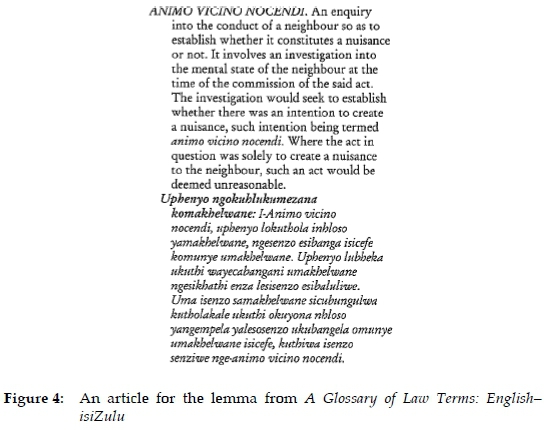

In order to communicate effectively, terminology users in African languages will need additional information which includes terminological definitions in both English and the target language to provide explanations of meaning. For those who are competent in English, English explanations will serve a disambiguating purpose as they search for target language terminology for mother-tongue text production purposes. Target language explanations may assist those with limited English competence to understand the meaning of the terms first in their own language and then in English if necessary. Failure to provide such information makes DAC products inferior to many others such as the bilingual glossary series of the University of KwaZulu-Natal, see for example Figure 4 illustrating an article from A Glossary of Law Terms: English-isiZulu.

The detailed explanation of Animo vicino nocendi in both English and isiZulu has great potential to assist novice law students who speak isiZulu to understand the concept to which the term refers, especially as the explanations use simplified language. However, etymological information for the Latin dominated law terminology would be useful for to provide further assistance for cognitive purposes.

Furthermore, pictorial and diagrammatical illustrations prove to be useful in conveying meaning information, especially in the scientific and practical disciplines. The Illustrated Glossary of Southern African Architectural Terms: English-isiZulu and the Longman Multilingual Maths Dictionary for South African Schools:

English, isiXhosa, Afrikaans have been well-conceived in this respect, as they try to provide as many pictures and diagrams as possible. However, others such as the Illustrated Science and Technology Dictionary / Isichazi-magama sezeNzululwazi neTeknoloji appear to be economic and arbitrary in illustrating concepts. Not only does arbitrariness result in some resources providing insufficient information, it may also lead to the inclusion of irrelevant information as shown in the next sub-section.

5.2 Irrelevant information

In order for lexicographers to provide relevant information types in their works, it is instructive to recall Tarp's (2000: 198) assertion that "the only way to reach a scientific conclusion of what should be included in a dictionary is to base this conclusion on an analysis of the user, the user characteristics, the user situations, the user needs and the corresponding lexicographic functions". Although specialized lexicography in African languages has thus far been discussed within the general framework of language intellectualization, it is important to engage in a more nuanced analysis of the products according to the function theory of lexicography (Tarp 2008) before identifying data that offers irrelevant information from some of the resources.

The cognitive lexicographic function (Tarp 2008) of specialized lexico-graphical/terminographical products recognizes their "pedagogical (didactic) function" (Lukasik 20l6: 211; see also Fuertes-Olivera 2010; Tarp 2005) "as carriers of specialised knowledge" (Lukasik 2016: 212). This function, or at least the intention to serve it, prevails in most specialized lexicographical/termino-graphical products in African languages. For example, the cognitive function finds expression when Young et al. (2005: 9) articulate that the aim of the resource Understanding Concepts in Mathematics and Science 2 is "to provide teachers and learners with accredited specialists' expert knowledge, understandings and descriptions of ... key concepts" in "Mathematics, Physics, Chemistry, Geography and Life Sciences". The cognitive function similarly motivated the compilation of the Illustrated Glossary of Southern African Architectural Terms: English-isiZulu, as Frescura and Myeza (2016: xv) reiterate its intention to support students with "ready access to a specialized lexicon", part of which carries "an inherent symbolism associated with the social values and cultural heritage of traditional rural society". A Glossary of Law Terms: English-isiZulu was developed to "improve cognitive development, critical thinking and epistemic access to complex pedagogies" (Khumalo 2018: x). As such, specialized lexicography/terminography in African languages is not simply about languages per se but more importantly about knowledge (cf Antia and Ianna 2016: 78), which underscores the cognitive function of the lexicographical products.

While cognitive lexicographic functions are distinguished from communicative functions (Tarp 2008), it is noteworthy that they are not mutually exclusive. Comprising of mainly text reception and text production, communicative functions are integral components of knowledge acquisition, knowledge production, knowledge reproduction and knowledge dissemination. The functions are equally critical for specialized lexicography/terminography in African languages. The use of English specialist terms in various professional fields and disciplines impedes comprehension of texts, both in oral and written forms. In order to address the problem of text comprehension that is impeded by English, mainly meaning information is provided in the mother tongue either in the form of translation equivalents or explanations of meaning in the form of terminological definitions. Once English terms have been understood via the mother tongue, they may then be used better for text production in English, the dominant official language. However, with specialized lexicography/terminog-raphy being conceived as part of the ultimate intellectualization of African languages for use in high status domains, the produced resources are also meant to assist users with terms and information that support text production in the target languages. As an example, A Glossary of Law Terms: English-isiZulu was conceived to launch "the process of cultivating and advancing isiZulu to be an appropriate tool for legal education and education practice" (Zondi 2018: xiv), i.e. facilitating legal communication within the academy and the profession.

Apart from insufficient information in some of the studied resources, as shown in the previous subsection, the opposite - inclusion of irrelevant data, may be noted in some specialized lexicographical/terminographical products in African languages. The problem may not be as prevalent as that of insufficient information but it is significant in terms of theoretical insights into specialized lexicography. One illustration of this issue is part-of-speech (PoS) information in Isichazi-magama seMathematika neNzululwazi and the Illustrated Science and Technology Dictionary / Isichazi-magama sezeNzululwazi neTeknoloji. In the former, all lemmata, which are English lexical items accompanied by isi-Xhosa translation equivalents, bilingual PoS labels such as n/b (noun/isibizo), v/nz (verb/isenzi) and adj/bl (adjective/isibaluli) are provided, with nouns being the majority. In the latter, most but not all lemmata are accompanied by monolingual PoS labels, namely n. (noun), v. (verb), pref. (prefix) and adj. (adjective), with nouns dominating again. Apart from the unexplained and inconsistent provision of PoS information in the latter dictionary, the decision to provide this information is not motivated anywhere in any of the two dictionaries which seem to focus on the cognitive function. With a more holistic curriculum approach which does not isolate language teaching from content subjects, it could be argued, even without the lexicographers clearly identifying this possibility, that the provision of such information could develop learners' knowledge of grammar. Furthermore, it could be argued that the provision of this information could develop users' awareness of the value of this type of lexicographic information. However, the lexicographers' utter silence about it suggests that they are equally oblivious of its inclusion. Compare this with the provision of PoS in the Multilingual Parliamentary Dictionary where this type of information is only purposefully included for disambiguation in cases where an included term belongs to more than one word class, e.g. audit as a noun and also as a verb. The motivation appears to be clear in the latter case.

Another type of lexicographic information of which the inclusion may be questioned is tone marking in Shona music terms dictionary Duramazwi reMimhanzi. This dictionary is largely cognitive in its functional dimension as it seeks to facilitate Shona mother-tongue speakers' access to specialist and ethno-musicological knowledge through Shona terminology and encyclopedic explanations. With the tonal aspects of language pertaining to oral text production (pronunciation) and, to some extent, oral text reception (auditory perception), this information could possibly be relevant if the dictionary was targeted at non-mother-tongue speakers of Shona. Tonal information is also supplied in Duramazwi ReDudziramutauro neUvaranomwe, the Shona dictionary of linguistic and literary terms, where it could possibly be justified in that tone would be an important topic of which each lemma could serve as a practical example for students. Without a clear motivation, it could be postulated that this type of information was included in both dictionaries taking after the general-purpose dictionaries, which had just been published as trendsetters in Shona monolingual lexicography.

The foregoing analysis presents the provision of PoS information and tonal marking in the discussed specialized dictionaries as grey areas. The value added to those dictionaries by the inclusion of such information remains doubtful. While insufficient information would clearly reduce the functional value of dictionaries, users may not always feel the negative impact of irrelevant information. However, from an academic point of view, inclusion of irrelevant information illustrates insufficient theoretical guidance in the planning and execution of practical lexicographic tasks. There may also be practical implications in terms of wasted dictionary space and time that is dedicated to the inclusion of irrelevant information. This may unnecessarily delay the publication of the dictionary. Without a convincing motivation of including such information for mother-tongue Ndebele-speaking music students and practitioners, the editors of the Ndebele music terms dictionary, Isichazamazwi SezoMculo, opted against its inclusion in light of the financial cost of hiring a linguist specializing in tone. The sentiment remains that some lexicographers included the data following trends in general-purpose lexicography rather than catering for the needs of their users in specific usage situations.

6. Design and structural issues

Improvement in lemma selection decisions and lexicographical treatment of selected lemmata in specialized lexicographical/terminographical products in African languages will need to be complemented by effective design and structural frameworks. Taking design and structural issues for granted may undermine a product that provides the necessary data at both macro- and microstructural levels. Accessibility of the necessary data is as important as its availability. Against this principle, the lexicographical/terminographical resources surveyed in this study may be divided into three categories, i.e. those that adopt fairly standard structural designs without much creativity in their data presentation, those that are sub-standard in their approach because of little if any inspiration from theoretical lexicography and those that adopt innovative approaches. The next two subsections will exemplify the latter two, i.e. sub-standardly structured resources and innovatively structured resources in 6.1 and 6.2 respectively, noting that there is not much to learn from the first category. It suffices to note that fairly standard dictionary designs are generally traditional in terms of their structural presentation of included lexicographical data even though they may not be as bad as those described as sub-standard in 6.1 below. However, the innovative practices noted in 6.2 need to be considered in the improvement of not only the sub-standardly structured resources but also those that display standard macro- and microstructures as there is always a room for improvement.

6.1 Sub-standard structural designs and presentation

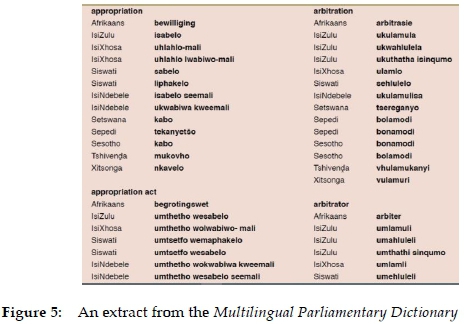

This category pertains to those resources that are mainly called glossaries or terminology lists. Compilers tend to list translation equivalents of selected English terms in target languages in a manner that indicates limited attention to structural and design issues. Consider Figure 5 below (DAC 2013d):

The extract from the Multilingual Parliamentary Dictionary is typical of DAC products which simply provide lists of translation equivalents in the other ten South African official languages for English terms. As they appear in bold print, English lemmata are admittedly easy to identify. So are the translation equivalents, which are also in bold and accessible via a vertical list of language names in regular print. However, in cases where more than one translation equivalent is provided in a particular language, e.g. three equivalents in isiZulu for arbitration, the language name is listed three times to indicate each of the equivalents. This results in some articles being longer than others, although each article provides translation equivalents for ten other official languages for English terms, which could be avoided by listing the equivalents horizontally for each English term. More importantly, the user will never be certain about the sense relations of multiple translation equivalents. At a cursory level, the translation equivalents may be regarded as synonyms, given that the English term is given without any explanation, which suggests multiplicity of senses. However, it will only take a competent isiZulu speaker to know that the isiZulu equivalents ukulamula (stopping a conflict), ukwahlulela (judging) and ukuthatha isinqumo (making a decision) are not absolute synonyms. Translators working under pressure may miss the nuanced differences and pick any of the translation equivalents, if not the first one, given that the criteria and order for listing multiple equivalents is not explained anywhere in the DAC dictionaries. Thus, as simple as the structure may appear to the eye, making sense of it may be more complex in a real user situation. Such a challenge may not be addressed by only thinking about the implications of the presentation but also by making use of outer texts to describe the structure of the resources, including providing user guidelines.

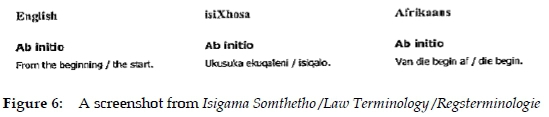

The seemingly simple but sub-standard structural designs and presentation of lexicographical data is not exclusive to DAC terminological dictionaries but characterize terminological products compiled for use in institutions of higher learning. Consider the Figure 6 below.

The screenshot is an article from Isigama Somthetho / Law Terminology / Regs-terminologie, which aims to "support Xhosa-speaking students who . struggle with difficult Law terms" and "widen the scope of ... [their] understanding, so that these students are afforded the opportunity to learn and understand these Law terms through their mother tongue" (Sibula 2007: iii). Having adopted a similar structure, the editors of the Illustrated Multilingual Science and Technology Dictionary / Isichazi-magama sezeNzululwazi neTeknoloji Ngeelwimi Ezininzi aver that "[t]he column format makes it simple to move from one language to another" (Mbude-Shale, Wababa and Welman 2008: vi). However, the brevity of the English explanations and their translations, as well as the lack of discipline-specific contextual examples of usage make it inconceivable how first-year law students struggling with legal terminology would benefit from such an article. The structural presentation shows that these simplistic structures accompany the provision of insufficient data as a major limitation of some specialized lexicographical/terminographical products in African languages. A tentative approach in the conceptualization of the majority of the products results in compilers neglecting design and structural issues, focusing on translating English terms.

6.2 Innovative design and structural presentation

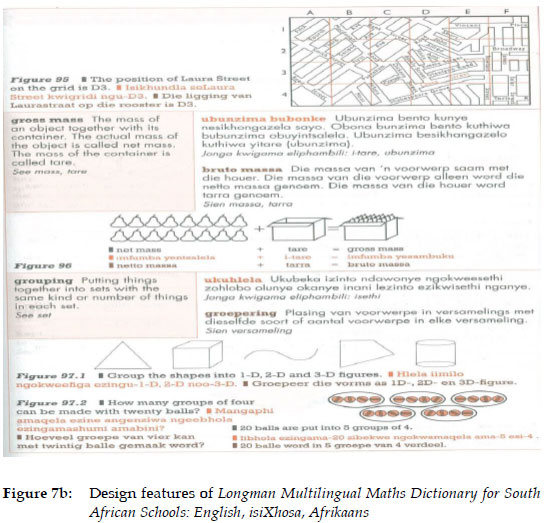

Notwithstanding the neglect of structural and design considerations in the compilation of lexicographical/terminographical resources highlighted in the previous sub-section, there are other gratifying and inspiring products in African languages which demonstrate lexicographers' meticulous consideration for the accessibility and user-friendliness of their products. Consider the examples in Figure 7a and 7b below. The examples illustrate key design features of two Mathematics dictionaries, namely IsiChazi-magama sezoBalo (Figure 7a) and the Longman Multilingual Maths Dictionary for South African Schools: English, isiXhosa, Afrikaans (Figure 7b). Apart from being specialized dictionaries, these dictionaries target junior school learners, i.e. children. Their use of colorful illustrations is a typical feature of children's dictionaries that increases the accessibility of the specialized mathematical content in the dictionaries. Not only are the colorful illustrations able to demonstrate complex mathematical operations for the target users, they also serve to attract the users and instill in them love for a generally intimidating and challenging subject, thereby serving a pedagogic function of specialized lexicography.

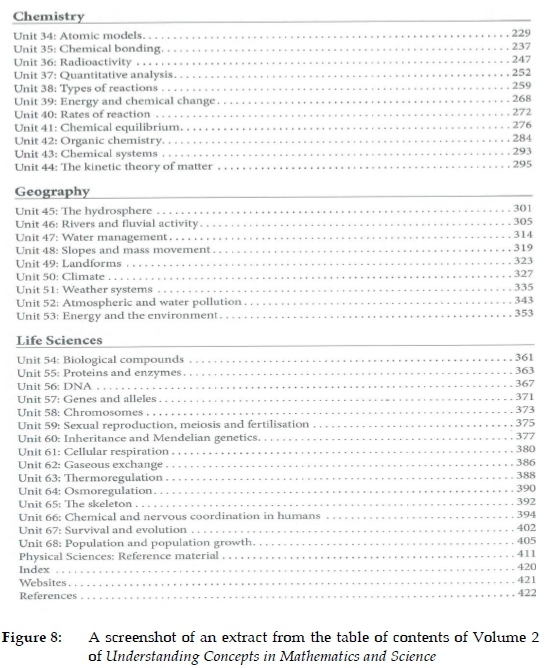

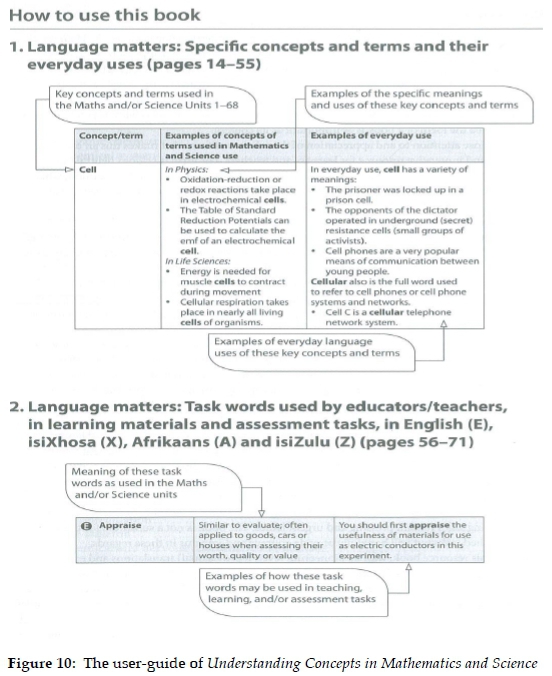

Young et al. (2005; 2009) also provide innovative examples of a functional approach to the design and structure of specialized lexicographical products. It is probably in view of the adopted structural design that the authors avoid calling their works dictionaries. The main text of Understanding Concepts in Mathematics and Science Vol. 2 covers sixty-eight broad topics that are considered key concepts within five Grade 10-12 subject areas under the old National Curriculum Statement, namely Mathematics, Physics, Chemistry, Geography and Life Sciences. A thematic macrostructure is then adopted whereby those topics are grouped under specific units, as shown in Figure 8 below for Chemistry, Geography and Life Sciences.

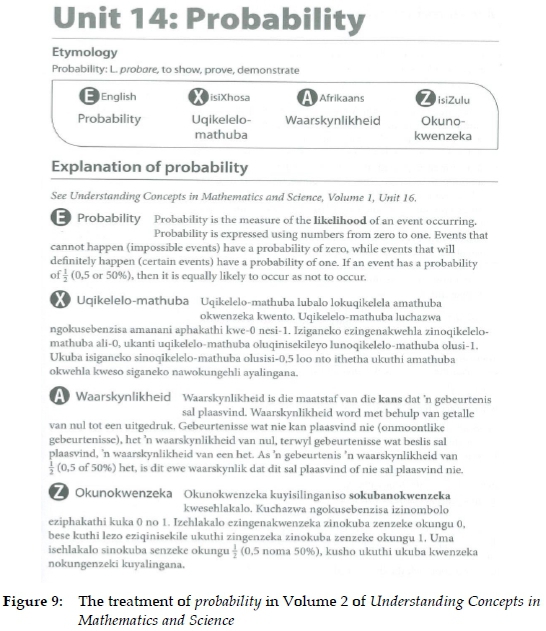

On a microstructural level, comprehensive treatment and clarity are prioritized ahead of space economy, with the multilingual and encyclopedic treatment of each concept taking several pages. Consider the treatment of the concept of probability shown in Figure 9 below. The treatment includes the presentation of etymological data, isiXhosa (X), Afrikaans (A) and isiZulu (Z) translation equivalents for each English (E) term followed by explanations in all four languages. Thereafter, more information follows about each topic, supported by examples and illustrative diagrams where necessary.

Besides the main text, there are useful outer-texts. Front matter texts include the following:

- How to use this book, a well-structured user guide that may help users as they familiarize themselves with the resource (see Figure 10 below)

- Multilingual contents, a table of contents listing unit titles in English and giving their translation equivalents in the four languages with their relevant pages

- Language matters: Concepts and terms, which provide scientific and everyday explanations of specific terms used within the broad topics covered in the main texts. The explanations are in English

- Language Matters: Task words, a text which provides isiXhosa, Afrikaans and isiZulu translation equivalents of instruction words used in teaching and assessment of the five subject areas, together with explanations in all the four languages.

The main text is followed by back-matter texts, two of them being:

- Physical Sciences: Reference material, a text dealing with examination guidelines and providing tables of common quantities symbols and SI units used in the five subject areas

- Index, a text which provides quick access to the specific pages in which specific terms and concepts are discussed.

The other two provide a list of websites and references to other publications that were used in the entire project. Based on the foregoing, it may be seen that not only rich are the Understanding Concepts in Mathematics and Science volumes in terms of their provision of subject-specific content and language, they also facilitate access to this rich material through their diligent data distribution structure. They are poly-accessible through their different access routes and may be used together with textbooks or to some extent as textbooks. Once mastered by the users, their innovative and hybrid structural features could be critical in establishing a dictionary culture not only for specialized lexicography within the framework outlined in Gouws (2013) but for the utilization of a variety of lexicographical products.

7. Conclusion

From the preceding sections of this article, it can be seen that there is a proliferation of specialized lexicographical/terminographical products in African languages. It was noted that the production of such products is inspired by the language intellectualization endeavor that is aligned to post-colonial language policies which seek to eradicate the colonial and apartheid (in South Africa) legacy of marginalization of African languages. The main focus of the article was reflecting on lemma selection, which determines to a large extent the cognitive and communicative assistance that users may get from these products within the context of specialized disciplinary fields and subjects, especially at a terminological level, the provision of additional data to support the understanding and usage of terminology, as well as aspects of design and structures. On the first issue, the article noted problems with lemma selection, with some dictionaries including items that are of little if any value in the respective subject fields or disciplines, while compilers of other products do not seem to use criteria that facilitate the inclusion of important terms and avoid glaring gaps. Problems of insufficient information and irrelevant information were also noted, with the former being typical of oversimplified products that mainly provide only translation equivalents while the latter appears to be an uncritical application of principles of general-purpose dictionaries. Similarly, problems were noted regarding structural aspects of some resources, but positives were also noted in this respect. Overall, it is apparent that there is more room for improvement, with the main problem being that the production of such resources lacks a strong orientation from lexicographic theories. Most of the surveyed resources were compiled largely by translators or at best terminolo-gists, working in collaboration with educationists and disciplinary experts in the relevant fields, all of them united by enthusiasm or sympathy towards multilingualism and African languages. Thus the relevant lexicographic expertise for lemma selection, inclusion of data categories and presentation of data is lacking. Antia and Ianna (2016) express a similar concern regarding terminology work in South Africa, which they regard as mere translation exercise without engagement with ontological issues that inspire terminology as a discipline. The compilers of the studied resources and African language speech communities appear to be content about the mere availability of the resources in their languages, even though most of the products may not be effective and user friendly in usage real situations.

Acknowledgements

Financial support by the National Research Foundation of South Africa (Grant specific unique reference numbers UID108981) is hereby acknowledged. The Grantholder acknowledges that opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in any publication generated by the NRF supported research are those of the author, and that the sponsor accepts no liability whats oever in this regard.

References

Antia, B. and B. Ianna. 2016. Theorising Terminology Development: Frames from Language Acquisition and the Philosophy of Science. Language Matters 47(1): 61-83. [ Links ]

Bergenholtz, H. and S. Nielsen. 2006. Subject-field Components as Integrated Parts of LSP Dictionaries. Terminology 12(2): 281-303. [ Links ]

Bowker, L. and J. Pearson. 2002. Working with Specialized Language: A Practical Guide to Using Corpora. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Chimhundu, H. and E. Chabata. 2006. Duramazwi reDudziramutauro neUvaranomwe. Gweru: Mambo Press. [ Links ]

Collins English Dictionary Online. https://www.collinsdictionary.com/submission/5703/Collins+English+Dictionary+online. Date of Access: 22 August 2019.

Department of Arts and Culture. 2013a. Multilingual Mathematics Dictionary: Grade R-6. Pretoria: Department of Arts and Culture. [ Links ]

Department of Arts and Culture. 2013b. Multilingual Financial Terminology List. Pretoria: Department of Arts and Culture. [ Links ]

Department of Arts and Culture. 2013c. Multilingual HIV/Aids Terminology. Pretoria: Department of Arts and Culture. [ Links ]

Department of Arts and Culture. 2013d. Multilingual Parliamentary/Political Terminology. Pretoria: Department of Arts and Culture. [ Links ]

Department of Arts and Culture. 2013e. Multilingual Terminology for Information Communication Technology. Pretoria: Department of Arts and Culture. [ Links ]

Department of Arts and Culture. 2013f. Multilingual Human, Social, Economic and Management Sciences Terminology List. Pretoria: Department of Arts and Culture. [ Links ]

Department of Arts and Culture. 2013g. Multilingual Natural Sciences and Technology Term List (Nguni). Pretoria: Department of Arts and Culture. [ Links ]

Department of Arts and Culture. 2013h. Multilingual Natural Sciences and Technology Term List (SeSotho). Pretoria: Department of Arts and Culture. [ Links ]

Department of Arts and Culture. 2013i. Multilingual Natural Sciences and Technology Term List (Tshivenda-Xitshonga). Pretoria: Department of Arts and Culture. [ Links ]

Department of Arts and Culture. 2013j. Multilingual Soccer Terminology List. Pretoria: Department of Arts and Culture. [ Links ]

Department of Education. 1997. Language-in-Education Policy. Pretoria: Department of Education. [ Links ]

Department of Higher Education and Training. 2002. Language Policy for Higher Education. Pretoria: Department of Higher Education and Training. [ Links ]

Deyi, S., G. Minshall and T. Tokwe. 2008. Longman Multilingual Maths Dictionary for South African Schools: English, isiXhosa, Afrikaans. Cape Town: Maskew Miller Longman. [ Links ]

Feza, N. et al. 2016. IsiChazi-magama sezoBalo. Pretoria: Human Sciences Research Council. [ Links ]

Frescura, F. and J. Myeza. 2016. Illustrated Glossary of Southern African Architectural Terms: English-isiZulu. Durban: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press. [ Links ]

Fuertes-Olivera, P.A. (Ed.). 2010. Specialised Dictionaries for Learners. Berlin: De Gruyter. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. 2007. On the Development of Bilingual Dictionaries in South Africa: Aspects of Dictionary Culture and Government Policy. International Journal of Lexicography 20(3): 313-327. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. 2013. Establishing and Developing a Dictionary Culture for Specialised Lexicography. Jesensek, V. (Ed.). 2013. Specialised Lexicography. Print and Digital, Specialised Dictionaries, Databases: 51-62. Lexicographica Series Maior 144. Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Hannan, M. 1959. Standard Shona Dictionary. Salisbury: The Rhodesia Literature Bureau. [ Links ]

IsiXhosa National Lexicography Unit. 2013. Isichazi-magama seMathematika neNzululwazi. Cape Town: South African Heritage Publishers. [ Links ]

Kaschula, R.H. and D. Nkomo. 2019. Intellectualisation of African Languages: Past, Present and Future. Wolff, H.E. (Ed.). 2019. The Cambridge Handbook of African Linguistics: 601-622. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Khumalo, L. 2018. Introduction. Zondi, K. 2018. A Glossary of Law Terms: English-isiZulu: ix-x. Durban: University of KwaZulu Natal Press. [ Links ]

Kropf, A. 1899. Kafir-English Dictionary. Alice: Lovedale Mission Press. [ Links ]

Landau, S.I. 1984. Dictionaries: The Art and Craft of Lexicography. New York: Scribner Press. [ Links ]

Lukasik, M. 2016. Specialised Pedagogical Lexicography: A work in Progress. Polilog: Studia Neo-filologiczne 6: 211-226. [ Links ]

Mawonga, S., P. Maseko and D. Nkomo. 2014. The Centrality of Translation in the Development of African Languages for Use in South African Higher Education Institutions: A Case Study of a Political Science English-isiXhosa Glossary in a South African University. Alternation 13: 55-79. [ Links ]

Mbude-Shale, N., Z. Wababa and K. Welman. 2008. Illustrated Multilingual Science and Technology Dictionary / Isichazi-magama sezeNzululwazi neTeknoloji Ngeelwimi Ezininzi. Cape Town: New Africa Books. [ Links ]

Mheta, G. (Ed.). 2005. Duramazwi reMimhanzi. Gweru: Mambo Press. [ Links ]

Ministerial Committee appointed by the Ministry of Education. 2003. Ministerial Report on the Use of Indigenous Languages in Higher Education. Pretoria: Department of Higher Education Training. [ Links ]

Mpofu, N., H. Chimhundu, E. Mangoya and E. Chabata (Eds.). 2004. Duramazwi reUrapi neUtano. Gweru: Mambo Press. [ Links ]

Nielsen, S. 1995. Dictionary Components. Bergenholtz, Henning and Sven Tarp (Eds.). 1995. Manual of Specialised Lexicography. The Preparation of Specialised Dictionaries: 167-187. Amsterdam/ Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Nkomo, D. 2010. Affirming a Role for Specialised Dictionaries in Indigenous African Languages. Lexikos 20: 371-389. [ Links ]

Nkomo, D. 2018. Dictionaries and Language Policy. Fuertes-Olivera, P.A. (Ed.). 2018. The Routledge Handbook of Lexicography: 152-165. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Nkomo, D. and M. Madiba. 2011. The Compilation of Multilingual Concept Literacy Glossaries at the University of Cape Town: A Lexicographical Function Theoretical Approach. Lexikos 21: 144-168. [ Links ]

Nkomo, D. and N. Moyo. 2006. Isichazamazwi SesoMculo. Gweru: Mambo Press. [ Links ]

Sibula, P. 2007. Isigama Somthetho / Law Terminology / Regsterminologie. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University Language Centre. [ Links ]

Simango, S.R. 2009. Weaning Africa from Europe: Toward a Mother-tongue Education Policy in Southern Africa. Brock-Utne, B. and I. Skattum (Eds.). 2009: 201-212. Languages and Education in Africa: A Comparative and Transdisciplinary Analysis. Oxford: Symposium Books. [ Links ]

Taljard, E. and D.J. Prinsloo. 2019. African Language Dictionaries for Children - A Neglected Genre. Lexikos 29: 199-223. [ Links ]

Tarp, S. 2000. Theoretical Challenges to Practical Specialised Lexicography. Lexikos 10: 189-208. [ Links ]

Tarp, S. 2005. The Pedagogical Dimension of the Well-conceived Specialised Dictionary. Ibérica. Journal of the European Association of Languages for Specific Purposes 10: 7-21. [ Links ]

Tarp, S. 2008. Lexicography in the Borderland between Knowledge and Non-Knowledge: General Lexicographical Theory with Particular Focus on Learner's Lexicography. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer. [ Links ]

Tarp, S. 2012. Specialised Lexicography: 20 Years in Slow Motion. Ibérica. Journal of the European Association of Languages for Specific Purposes 24: 117-128. [ Links ]

Van Niekerk, T. and J. Wolvaardt (Eds.). 2010. Oxford South African Concise Dictionary. Second edition. Cape Town: Oxford University Press Southern Africa. [ Links ]

Wababa, Z., K. Welman and K. Press (Eds.). 2010. Isichazi-magama seziBalo Sezikolo saseCambridge. Cape Town: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Young, D. et al. 2005. Understanding Concepts in Mathematics and Science - A Multilingual Learning and Teaching Resource Book in English, IsiXhosa, IsiZulu and Afrikaans. Volume 1. Cape Town: Maskew Miller Longman. [ Links ]

Young, D. et al. 2009. Understanding Concepts in Mathematics and Science - A Multilingual Learning and Teaching Resource Book in English, isiXhosa, isiZulu and Afrikaans. Volume 2. Cape Town: Maskew Miller Longman. [ Links ]

Zondi, K. 2018. A Glossary of Law Terms: English-isiZulu. Durban: University of KwaZulu Natal Press. [ Links ]

* This article is a revised version of a paper that was presented at the 24th Annual International Conference of the African Association for Lexicography (AFRILEX), hosted by the Department of Language and Literature Studies, University of Namibia, Windhoek, Namibia, 26-29 June 2019. The author acknowledges the constructive feedback obtained from conference delegates as well as the two anonymous adjudicators.