Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Lexikos

versão On-line ISSN 2224-0039

versão impressa ISSN 1684-4904

Lexikos vol.29 Stellenbosch 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.5788/29-1-1513

ARTICLES

The Lexicographic and Lexicological Aspects of a Web-Based Chrestomathy of Gothic and Anglo-Saxon Written Records

Die leksikografiese en leksikologiese aspekte van 'n webge-baseerde chrestomatie van Gotiese en Angel-Saksiese geskrewe rekords

Tinatin MargalitadzeI; George MeladzeII

ILexicographic Centre, Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, Tbilisi, Georgia (tinatin.margalitadze@tsu.ge)

IILexicographic Centre, Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, Tbilisi, Georgia (meladzegeorge@yahoo.com)

ABSTRACT

There is a general lack of web-based tools for morphologically complex dead/old languages. Reading texts in such languages even with dictionaries is quite challenging. It is difficult to identify the lemma of a word form occurring in texts, which one could look up in a dictionary. The need for additional grammatical information about a word (classes of declension, conjugation, etc.) poses another problem.

The Lexicographic Centre at Ivanè Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University (TSU) has embarked on creating a fully digitalized, web-based chrestomathy of Gothic and Anglo-Saxon texts with dictionaries and grammatical paradigms integrated in it, which would facilitate the study of these linguistically important languages. Each word of the digital versions of Gothic and Anglo-Saxon texts is hyperlinked to the corresponding headword from the dictionary. The dictionary entry itself, in addition to the meaning of the word, provides via another hyperlink all necessary information concerning the morphological class and inflectional patterns of the word in question.

The paper describes the structure of the Chrestomathy and its modus operandi; analyses the dictionary component of the online resource and some lexicographic solutions; discusses lexicological and technical aspects of the online resource, etc.

The method applied in the Chrestomathy can be successfully used in developing similar resources for extant, morphologically complex languages characterized with the abundance of inflectional and suppletive forms, such as Hungarian, Turkish, Russian, German, Georgian and many others.

Keywords: digital humanities, gothic, anglo-saxon, comparative linguistics, synchrony and diachrony, semantic equivalence

OPSOMMING

Daar is 'n algemene tekort aan webgebaseerde hulpmiddels vir morfologies komplekse dooie/antieke tale. Selfs met behulp van woordeboeke is dit redelik uitdagend om tekste in hierdie tale te lees. Dit is moeilik om die lemma van 'n woordvorm wat in die tekste voorkom, te identifiseer sodat dit in 'n woordeboek nageslaan kan word. Die behoefte aan addisionele grammatikale inligting van 'n woord (tipes verbuiging, vervoeging, ens.) skep weer 'n ander probleem.

Die Leksikografiese Sentrum by Ivanè Javakhishvili Tbilisi Staatsuniversiteit (TSU) het begin met die skep van 'n volledig gedigitaliseerde, webgebaseerde chrestomatie of studiehulp van Gotiese en Angel-Saksiese tekste met woordeboeke en grammatikale paradigmas daarin geïnte-greer, wat die studie van hierdie taalkundig belangrike tale sal vergemaklik. Elke woord van die digitale weergawes van Gotiese en Angel-Saksiese tekste is deur hiperskakels verbind met die oor-eenstemmende trefwoorde in die woordeboek. Buiten die betekenis van die woord verskaf die woordeboekinskrywing self via 'n ander hiperskakel al die noodsaaklike inligting rakende die mor-fologiese klas en verbuigingspatrone van die tersaaklike woord.

Hierdie artikel beskryf die struktuur van die chrestomatie en die modus operandi daarvan; analiseer die woordeboekkomponent van die aanlynbron en sommige leksikografiese oplossings; bespreek leksikologiese en tegniese aspekte rakende die aanlynbronne, ens.

Die metode wat toegepas word in die chrestomatie kan suksesvol aangewend word in die ontwikkeling van soortgelyke bronne vir lewende, morfologies komplekse tale, wat gekenmerk word deur talle verbuigings- en suppletiewe vorme, soos Hongaars, Turks, Russies, Duits en nog vele ander.

Sleutelwoorde: digitale geesteswetenskappe, goties, angel-saksies, ver-gelykende linguistiek, sinchronie en diachronie, semantiese ewivalensie

1. Introduction

The article provides a researched-based and theoretically-engaging presentation of the online Chrestomathy which was executed at the Lexicographic Centre of TSU with the funding of Shota Rustaveli National Science Foundation of Georgia (Grant No. FR17_87).

The Chrestomathy is conceived as a web-based resource for studying the Gothic and Anglo-Saxon (Old English) languages and represents the rapidly developing field of Digital Humanities (DH).

The Chrestomathy is intended as a complex digital resource which can considerably facilitate the study of aforesaid languages, so important for general linguistics, German, English and Scandinavian studies. The electronic online resource comprises dictionaries, as well as Gothic and Anglo-Saxon (Old English) texts represented in their electronic, programmatically processed format.

The texts included in the online Chrestomathy are programmatically integrated with Gothic-Georgian/Gothic-English and Anglo-Saxon-Georgian/ Anglo-Saxon-(Modern) English dictionaries and with the morphological paradigms of Gothic and Anglo-Saxon words, i.e. electronic grammatical tables demonstrating the patterns of inflection (declension, conjugation, etc.) from the aforesaid two languages. The entire resource has its Georgian and English versions, making them accessible to the individuals interested in philology, linguistics and, especially, in Germanic studies in general, or, in Indo-European studies and comparative linguistics in particular both in Georgia and (thanks to the international status of English) in the entire world.

This is the brief introduction to the online Reader and its aims. A more detailed analysis of its composition, as well as its lexicographic, lexicological and technical aspects will follow.1

2. Why Old/Dead Languages and Why Specifically Gothic and Anglo-Saxon?

Gothic is a so-called dead language from the East Germanic subgroup of languages. The language is preserved in the form of a few surviving manuscripts (mainly fragments from Gothic gospels). Gothic is not directly ancestral to any extant language, but due to various circumstances, it has unique importance both for the diachronic study of modern Germanic and Indo-European languages and comparative or general linguistics.

By a number of its morphological and lexical features, Gothic is a very archaic language, in some aspects even more archaic than runic Norse (e.g. the gradation of root-forming vowels: u/-au- [sunus vs sunaus, sunau] or -i-/-ai-[*mahtis, mahtim vs mahtais, mahtai] in Gothic -u- stem and -i- stem nouns, absent in runic Norse; Krause 1951). This very archaism makes Gothic immensely valuable to linguists. Gothic, as it seems, is very similar to Common Germanic (Proto-Germanic) parent language. One could state that Gothic may be regarded as one of the surviving (in the form of manuscripts, of course) dialects of presumed Proto-Germanic Ursprache. To certain degree, the relation of Gothic to modern Germanic languages can be compared to the relation of scantily (unlike Gothic) preserved Umbrian or Oscan to modern Romance languages.

The aforesaid archaic nature of Gothic makes its linguistic affinity (and, consequently, that of other Germanic languages) especially conspicuous with Latin, Lithuanian, Sanskrit and other Indo-European languages. Mastering Gothic language incredibly broadens the linguistic thinking of a scholar. Knowing Gothic and other old languages is scientifically much more advantageous than acquiring general information about linguistic affinity in scientific papers or etymological dictionaries. Immediate familiarity with this unique and archaic language whose written records are still available, gives a scholar some very clear idea of the peculiarities of the functioning and development of language as such both on synchronic and diachronic levels. We dare say that the knowledge of Gothic and other ancient Indo-European languages (such as Greek, Latin, Lithuanian, Sanskrit, etc.) is as necessary for a linguist, as the knowledge of human anatomy is for a physician or a surgeon. Without such knowledge one cannot form an adequate understanding of the processes defining how language functions and develops.

This is why Gothic is taught at the institutions of higher education of many countries, such as in Leiden University (the Netherlands), University of Copenhagen (Denmark) and other universities. There is an important centre for the research on Gothic at Uppsala University (Sweden), where Codex Argenteus, the most valuable surviving record of the Gothic language is kept and where the computerized database of Gothic texts was created. In the Soviet era, Gothic was taught to linguists during their postgraduate studies (including at Tbilisi State University). Nowadays, Gothic is taught to the students of Tbilisi State University Bachelor's Degree Programmes and Master's Degree Programmes within the framework of theoretical courses: "Introduction to Germanic Philology" (Bachelor's Degree Programme) and "Comparative Grammar of Germanic Languages" (Master's Degree Programme). "Introduction to Germanic philology" is also taught at other Georgian universities, e.g. at Batumi Shota Rustaveli State University.

Such an attitude towards Gothic indicates that, in academic circles, Gothic philology by its status is practically equated with Classical philology.

From the philological and linguistic points of view, the Anglo-Saxon language is equally important. Especially taking into consideration the fact that it constitutes an early stage of development of the English language, which is so important and widely used today.

Beowulf, one of the most important works of English literature, a rare product of the synthesis of Pagan and Christian cultures, is written in Anglo-Saxon/Old English. This epic poem written in alliterative verse can be fully appreciated only in the original, which necessarily requires the knowledge of the Anglo-Saxon language. Literary works composed in Anglo-Saxon/Old English are considered to be an important part of English literature. Accordingly, quotations from Beowulf and other pieces of literature written in Old English are included in the articles of the Oxford English Dictionary as illustrative citations.

The knowledge of Old English and Middle English (which is a kind of transitional stage between the English of the Anglo-Saxon period and the Modern English language) helps one clearly understand why spelling and pronunciation in Modern English differ so substantially. Such knowledge also facilitates the attainment of proficiency in English spelling and orthography. Without at least some basic knowledge of Middle English and Early New English (the early stage of the Modern English language) it is practically impossible to read and adequately comprehend the works of important and influential English authors such as Chaucer or Shakespeare. This is why Anglo-Saxon or Old English is taught in many institutions of higher education having respective departments of English philology.

3. Background: Types of Available Printed and Electronic Resources for Old Languages

Qualitatively speaking, there are two types of resources for studying old languages, viz. printed and electronic.

In the Soviet Union and post-Soviet countries (where the concerned project originates from) the users interested in old languages could avail themselves of several different printed resources (in Russian). The majority of these resources consisted of language manuals (including the description of the phonetics, morphology and syntax of the language in question), as well as the paradigms/grammatical tables of word declension and conjugation, texts to read for the language acquisition and necessary glossaries. Such printed resources included for instance a Gothic manual + reader + glossary by Mirra Gukhman (Gukhman 1958). There was a similar book by S. Chemodanov, which included texts in Old High German, Old Low Saxon and Middle High German (Chemodanov 1978). The book was appended with Gothic material: similar morphological tables for Gothic, Gothic glossary and some excerpts from Codex Argenteus.

The book by the Russian-Soviet scholar Alexandr Smirnitsky (Smirnitsky 1953) included Old English/Anglo-Saxon, Middle English and Early New English texts, as well as brief description of the historical development of the English grammar and the glossary of Old English, Middle English and Early New English words.

The book by the outstanding Russian specialist in Scandinavian studies, Mikhail Steblin-Kamensky "Old Icelandic Language" (Steblin-Kamensky 1955) shared essentially the same structure (i.e. a review of grammar, morphological paradigms, Old Icelandic texts and the glossary).

The use of this type of educational material for the acquisition of old languages is too tiresome and time-and-energy consuming to be sufficiently effective for the education of our modern, highly "digitalized" youth, who are accustomed to the routine use of computerized devices like smartphones and tablets, to say nothing of computers themselves.

The root of the problem lies in the fact that the languages in question (Gothic and Anglo-Saxon) belong to the so-called synthetic type and are marked with considerable morphological diversity. It means that each word, whether it be a noun, adjective or verb, occurs in text in many different inflectional forms, depending on its case, number, gender or person. For example, qamt in Gothic means 'you came' (or, more precisely, 'thou camest'), qëmum means 'we came' and qëmun - 'they came', while the initial form, the infinitive of this verb which a reader/student should look up in a dictionary, is qiman -'to come'. A similar pattern is observed with nouns and adjectives. Nouns and adjectives are inflected in Gothic in accordance with their number, gender and case, so that it is not always easy to determine the respective lemma (which must be looked up in a dictionary) for each of these word forms.

There is a very similar picture in Anglo-Saxon, which is marked with the nearly identical morphological complexity and diversity of inflectional forms, whether it be in the declension of nouns and adjectives, or in the conjugation of verbs.

As a result, reading a Gothic or Anglo-Saxon text in a printed chrestoma-thy, a learner of language has to constantly refer to the grammar tables (paradigms) showing the regularities of the inflection of nouns, adjectives and verbs, in order to determine their lemmas. Only then can he/she look up the word in a dictionary and determine its meaning. It is easy to imagine how laborious and cumbersome this process may be using printed books. It may take a vast amount of time and energy to read, morphologically analyze and understand just one sentence using such an obsolete method, no matter how comprehensive dictionaries or reference books may be available to the person in question.

The second type of educational tools for studying old languages includes electronic databases/chrestomathies (with dictionaries/glossaries). Some examples include the Gothic language database (available online) administered by Uppsala University Library (The Gothic language); Gothic Online - an online reader of Gothic texts compiled by the Linguistic Research Center of the University of Texas at Austin (Gothic Online);2Wulfila Project - a small digital library dedicated to the study of Gothic and Old Germanic languages, hosted by the University of Antwerp, Belgium (Project Wulfila) (http://www.wulfila.be/), contains almost all known Gothic texts, thoroughly analyzed on word-by-word basis both morphologically and semantically;3 the online version of the well-known Bosworth-Toller Anglo-Saxon Dictionary (Anglo-Saxon Dictionary); an online dictionary of Old High German hosted by the Saxon Academy of Sciences in Leipzig, Germany (Althochdeutsches Wörterbuch) and some others.

It should be noted that the online electronic resources providing exhaustive information on the meaning and morphological status of the texts they feature, leave very little to students' creativity, curiosity and diligence and make the reading process too easy. Experience shows that such 'simplification' is not really helpful for students in memorizing morpho-grammatical regularities and semantics of the old language(s) they wish to master.

4. Web-Based Chrestomathy - Reasons for its Composition and Modus Operandi

The problems and difficulties described in the previous section led to the development of an electronic resource which, in the authors' opinion, would significantly facilitate the mastery of these two philologically important languages.

4.1 The Initial Reader

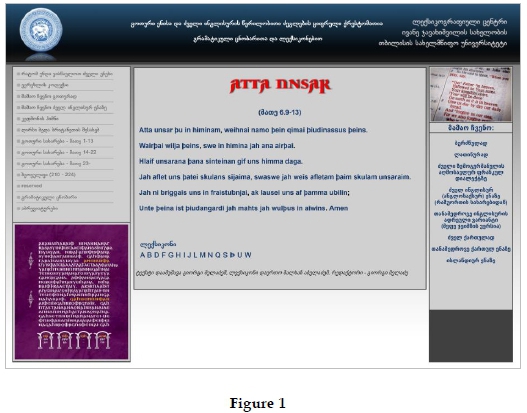

As a first step, we tentatively developed a web-based educational Reader (http://gothic.margaliti.com/siteatta.htm) which includes the Gothic version of the Lord's Prayer (Atta unsar which in Gothic means "Our Father", see Figure 1), the Lord's Prayer in Anglo-Saxon, as well as some other fragments of Gothic and Anglo-Saxon texts together with certain auxiliary and/or supporting materials.

In the Gothic text of the Lord's Prayer every word is hyperlinked and pop-up windows supply complete morpho-semantic analysis of words. Proceeding from the considerations discussed in the previous section, this method was rejected and other texts are not hyperlinked. Instead of hyperlinks, glossaries, provided for each text, contain not only lemmas as headwords, but also all word forms of a given text which are cross-referenced to corresponding lemmas. For example: in the glossary of the Old English version of the Lord's Prayer, the word form heovonum is cross-referenced to the lemma heovon 'heaven'; the word form urne is directed to ure, 'our' and so on.

The development of the Reader was dictated by the need of teaching Gothic and Anglo-Saxon to the students of Tbilisi State University. The introduction of the Reader to students made the teaching process more enjoyable and considerably increased their interest in these languages, in etymologies of words, in affinity of languages and comparative linguistics in general. Encouraged by this initial success, we further elaborated our idea and the decision was made to develop an integrated, complex, more sophisticated electronic web-based resource for reading Gothic and Anglo-Saxon texts, based on an adequate piece of computer software. We also decided to supply this upgraded version of the resource with an English interface, in order to make it accessible to English-speakers/foreigners. Such an electronic resource, as we hope, will enable Georgians as well as English-speaking foreigners to read and analyze old texts in these linguistically very important languages by means of their native Georgian or English. The importance of computer software is emphasized because without an adequate programmatic support, any collection of electronic texts will be exactly as (or even more) unmanageable and hardly navigable, as the printed versions of such texts.

4.2 The New Chrestomathy

In order to give the readers of the present article some general idea of the composition and organization of the Chrestomathy, how it works and what the exact method of its operation is, we would like to make a brief demonstration using computer screenshots.

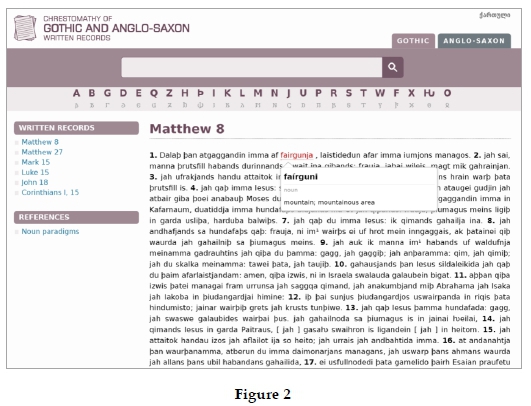

The Chrestomathy (http://germanic.ge/en/got) includes 6 Gothic texts from the New Testament4 and 7 Anglo-Saxon texts,5 all of which are lemma-tized, that is, all words of these texts have their lemmas identified and each of them is hyperlinked to the respective dictionary headwords.

This is illustrated below. If we choose a Gothic text from the Chrestomathy (Chapter 8 from Matthew's gospel for instance http://germanic.ge/en/got/record/matthew-8/) and move our mouse pointer over some word (say, fairgunja in the very first line of the text, see Figure 2), we shall see a hover box with the essential information about the word: lemma/dictionary headword faírguni; Part of speech (PoS) tag noun and the definition of the word 'mountain, mountainous area'.

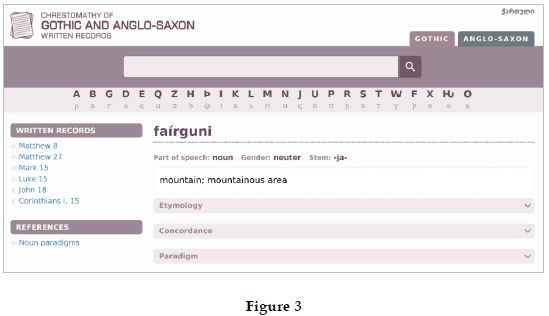

Double-clicking on the word fairgunja will direct us to the full dictionary entry containing more detailed information concerning the word in question (see Figure 3).

This "shorter" default version of the article provides the following information: lemma/headword fatrguni); PoS tag (noun); Gender (neuter); Stem type (-ja- stem); and Definition ('mountain, mountainous area').

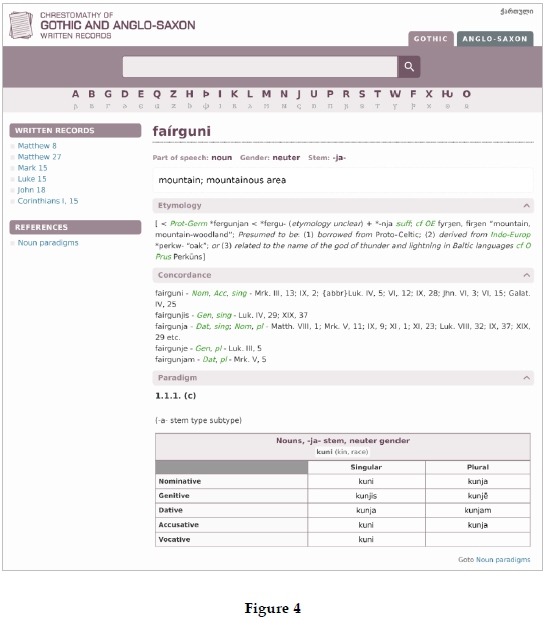

The extended version of the same article with Etymology, Concordance and Paradigm boxes toggled on conveys respectively the following information: (i) etymology (the word's supposed origin and its purported correspondences in cognate Germanic and Indo-European languages); (ii) concordance (inflectional forms of a word as they occur in various places of Gothic texts, with their exact occurrences precisely indicated); and (iii) the generalized paradigm of -ja- stem nouns, shown on the example of the Gothic word kuni ('kin, family') (see Figure 4; for more detailed information about the dictionary component of the Chrestomathy, see section 4.3).

Similarly, in their extended versions, entries defining verbs contain (in addition to the PoS tag) information on the type of each verb in question (strong, weak, irregular), its class (strong verb class 3, weak verb class 2, etc.), and, due to the wide and frequent use of participial constructions in Gothic, present participle (in cases where the present participle form is attested for the particular Gothic verb).

With the additional boxes toggled on, each verb entry provides the information on the word's etymology and concordance/occurrences (as in case with other parts of speech) and also the paradigm of the conjugation of this type of verb.

In addition, taking into consideration the morphological specificities and importance of present participles in Gothic, "extended" versions of verb entries are hyperlinked to the generalized declensional paradigm of present participles (shown on the example of qipands - 'saying, speaking'). This paradigm is supplied with a short explanatory text (which can also be toggled on/off) characterizing the use and functions of present participles in Gothic.

The web-based Chrestomathy also contains the paradigms of strong and weak declensions of Gothic (and Anglo-Saxon) adjectives, of personal, possessive, relative, etc. pronouns and so on.

The Anglo-Saxon version of the web-based reader operates quite similarly.

4.3 The Dictionary Component of the Chrestomathy

A dictionary entry of Gothic words consists of three parts: 1. Description of meaning; 2. Concordance; 3. Etymology.

4.3.1 Meaning

Description of meaning of Gothic words in a bilingual Gothic-Georgian Dictionary would be somewhat different from the approach adopted by us for the present Chrestomathy. In an ordinary bilingual dictionary, one of the challenges of lexicographers is the problem of equivalence, which is to be addressed properly (Adamska-Salaciak 2010; Margalitadze and Meladze 2016).

Comparison of the translation of one and the same Gothic word in the Georgian translation of Gospels, reveals that in many cases, a Gothic word has several contextual equivalents in Georgian. For example: meaning of the Gothic verb gafulljan is 'to fill', in Georgian ògbQÒò 'avseba'. In Luke 1:15 'jah ahmins weihis gafulljada nauhban in wambai aibeins seinaizos' ('and he shall be filled with the Holy Ghost, even from his mother's womb'), the Gothic verb gafulljan is translated by the Georgian verb ocißbgoo aghvseba (lit. 'to overflow'); in Mark 15:36 'bragjands ban ains jah gafulljands swam akeitis ('And one ran and filled a sponge full of vinegar'), the Gothic verb gafulljan is translated by a Georgian verb ftòjjçigBcDò 'gazhghenta' (lit. 'to soak, to saturate').

In a bilingual Gothic-Georgian Dictionary entry of the Gothic verb gafulljan, its meaning would be described by the Georgian equivalent oßbjoo 'avseba' (lit. 'to fill'), followed by several illustrative citations from Gospels, where the Gothic verb in question is translated by different Georgian contextual equivalents ('to overflow', 'to soak'; see examples above).

As mentioned above, a different approach was adopted for the dictionaries integrated in the present Chrestomathy. Dictionary entries do not contain illustrative quotations as the Chrestomathy contains texts from Gospels where Gothic words are attested. As to description of meaning, alongside general Georgian equivalents of Gothic words, contextual equivalents may also be provided in some instances, when these contextual equivalents are used in the texts of the Chrestomathy. In the case of the Gothic verb gafulljan, discussed above, its dictionary entry in the Chrestomathy contains two meanings: 1. oßbg&o 'to fill'; 2. gjòfjçigBcDò 'to soak, to saturate'. The latter is a contextual equivalent of the Gothic verb gafulljan (see discussion above), but it is added to the entry as a separate meaning, because this contextual equivalent is attested in Mark 15, one of the texts of the Chrestomathy. Some dictionary entries of the Chrestomathy contain Gothic collocations, also attested in the texts of the Chrestomathy.

Thus an entry structure of a dictionary incorporated in the Online Chrestomathy differs from an entry structure of an independent bilingual Gothic-Georgian dictionary. Such lexicographic decisions were dictated by didactic considerations and, from our point of view, will facilitate the understanding of Gospel texts.

4.3.2 Concordance

Articles in the Gothic dictionary are also supplied with Concordance information, showing exact textual occurrences of each Gothic word (chapters and paragraphs of Gospels, Epistles, etc.). Textual occurrences of Gothic words are sorted out according to grammatical forms. For example:

gafulljada - III person, singular, mediopassive (voice), indicative (mood) - Luke I, 15; gafullidedun - III person, plural, past, indicative (mood) - Luke V, 7; John VI, 13; Skeireins VII, 8

gafulljands - present participle - Mark XV, 36.

The subject of concordances of Gothic words and the linguistic importance we attach to the identification and analysis of contextual occurrences of Gothic lexical units will be discussed in more detail in the final section of this article.

4.3.3 Etymology

Each dictionary entry includes Etymologies: i.e. cognate words from related Old Germanic (Old English, Old High German, Old Saxon, Old Frisian, Old Norse, Old Icelandic) or other Indo-European languages (Ancient Greek, Latin, Sanskrit, Hittite, Slavic languages, etc.) etymologically connected with the particular Gothic word/dictionary headword. Thus, the resource gives the user a clear idea of the etymological background of a word, showing at the same time the pattern of development, which the meaning of its root has followed in particular related languages.

Experience shows that etymologies are one of the most interesting issues in the study of these languages for students. They find it very interesting to discover that an English word may have cognate forms in Gothic, Sanskrit, Latin, Old Church Slavonic and other languages. Consequently, this part of the dictionary entry is treated with due attention. Etymologia proxima (immediate etymology) is provided for all Gothic words, i.e. each entry contains cognate words from Old Germanic languages, as well as reconstructed Proto-Germanic words. For example: etymological part of the entry of the Gothic word dags 'day' includes the following information: [Proto-Germanic *dagaz; Old English dceß (Modern English day); Old Frisian dei, άϊ; Old Saxon dag; Old High German tag, tac (Modern German Tag); Old Icelandic dagr (Modern Icelandic dagur)].

Despite the wide-spread opinion that providing etymologia remota (remote etymology) should be avoided in order to make less mistakes in etymologies (Buchi 2006; Durkin 2009), the decision was made still to include cognate words from other Indo-European languages. This decision was based on students' interest in such information, on the other hand, the dictionaries in question are not etymological ones, which fact justifies occasional inclusion of even conjectural information. For example: the etymology of the Gothic word himins 'heaven' includes the following information: [Proto-Germanic *hemina-, *hemna-; Old Saxon hevan, heban; himil; Old Icelandic himinn; Old Frisian himel, himul; Old High German himil; - Indo-European *akmen-; Sanskrit ásmãn "stone, rock; heaven, firmament"; Avestan asman- "stone; heaven, firmament"; Greek άκμων "anvil"; Lithuanian akmuo "stone"; Old Slavic kcmiu (Russian KcmeHb "stone")]. Students find such etymologies very interesting. They realize that the English word heaven may be cognate with a word denoting 'stone' in another related language, because ancient peoples believed that the firmament was of solid matter. Semantic differentiation between cognate words in different related languages is another issue which sparks students' interest, therefore such cases are provided not only with cognate forms, but also their meanings, as is seen from the example above with himins.

The dialog boxes containing the information concerning word etymology and concordance can be toggled on or off by means of on-screen buttons.

4.3.4 Grammatical Information in Entries

As already mentioned above, each dictionary entry provides all necessary information concerning the morphological class and inflectional patterns of the word in question. Furthermore, morphological paradigms of main parts of speech: noun, verb, adjective and pronoun are created electronically and incorporated in the Chrestomathy. Figure 4 shows the toggled-on generalized paradigm of -ja- stem nouns, presented on the example of the Gothic word kuni ('kin, family').

Thus the dictionary article is connected via another hyperlink with the grammatical paradigm showing the declensional pattern of this class (-ja- stem) of Gothic neuter nouns. The forms given in the paradigm will help the user quickly and clearly understand that the word he/she has looked up in the dictionary (fairgunja) is a form of dative case, singular of the entry headword fairguni.

The treatment of Anglo-Saxon texts and corresponding morphological information is essentially the same insofar as the Anglo-Saxon/Old English language shows considerable morphological similarity with Gothic. Thus, the ways of the presentation in the Chrestomathy of lexico-semantic and morphological data concerning Anglo-Saxon are practically identical with those employed with respect to Gothic. The only difference is that Anglo-Saxon dictionary articles are not supplied with concordance information, as far as the great abundance of Old English texts makes it unnecessary and practically impossible to indicate all manuscripts, texts or contexts where this or that Anglo-Saxon word occurs.

4.4 The Method

As one can see, instead of leafing to and fro through the volumes of printed readers, the Georgian-speaking or English-speaking student of Gothic and Anglo-Saxon having access to our Chrestomathy, can comfortably sit in front of a computer screen with all the important lexical and grammatical information, necessary for the proper understanding of a text written many centuries ago, being just a mouse click away.

On the other hand, this method was also developed because we do not approve of the approach involving word-for-word translation and the presentation of the full grammatical information concerning the word under analysis inside the pop-up or drop-down windows. Our deliberate purpose was to avoid unnecessary simplification of the process of analysis of the surviving old texts for language learners. We preferred to encourage the application of the dictionary integrated in the electronic reader with respective morphological paradigms connected with dictionary articles. This will, hopefully, on the one hand, encourage the development of independent and creative linguistic thinking in old language learners and, on the other hand, facilitate stable memorization of semantic and morphological peculiarities of these languages. We also hope that such approach to learning old languages will give students better insight in understanding the peculiarities of the functioning and development of language as such both on synchronic and diachronic levels, understanding of underlying processes which are at play in language.

5. Some Linguistic, Lexicographic and Other Difficulties Associated with the Chrestomathy

In this section there will be discussed some difficulties, encountered at various stages of the development of the online resource.

When the work on the Gothic-Georgian and Gothic-English dictionaries started, it was expected that old Georgian and English translations of Gospels would substantially facilitate the task of finding exact Georgian and English equivalents for Gothic words. Such expectations in this respect were based on the fact that, as a rule, older translations of Gospels very closely follow their Greek original, but in fact this was not always the case. This happened because despite the presence of considerable contentual proximity of respective Gothic, Georgian and English Gospel texts, there were some significant differences in the concrete means of grammatical conveyance of the same meaning. For instance, one difficulty encountered in the process of defining Gothic verbs was caused by the issue of the verb transitivity-intransitivity, namely, many Georgian and English intransitive verbs corresponded to their Gothic counterparts which were in fact transitive, but stood in (medio)passive voice. Relying upon Georgian/English rendition of such Gothic verbs and interpreting them in the dictionary as intransitive would be erroneous and inadmissible. Thanks to background knowledge as concerns the etymology of Gothic and other Germanic words, possible mistakes in addressing this particular issue were avoided.

The disambiguation of homonyms also posed significant linguistic and technical problems. It should be noted that each and every specific homonym in the Chrestomathy is individually hyperlinked to its corresponding lemma in the dictionary, eliminating any chance of mistake or misinterpretation.

For instance, the Gothic word im, wherever it means 'them' (personal pronoun, dative case, plural of all three genders) is hyperlinked to the dictionary lemma eis 'they' (personal pronoun, nominative case, plural, masculine), but any homonymous Gothic word im encountered anywhere in the texts with the meaning '(I) am' is hyperlinked to the lemma/dictionary entry wisan 'to be'.

Likewise, the Anglo-Saxon word for when used in the sense of the preposition, is linked to the lemma/entry for (meaning essentially the same as the modern English preposition 'for' ); however, when the homonymous word for represents the past tense (singular, 1, 3 persons) of the strong verb faran ('to fare', 'to go', 'to proceed' ), in such cases a mouse-click on for will direct the user to the dictionary headword faran - verb 'to fare'. Also, the occurrences of the words hund whenever they may be encountered in the text, will direct us either to the entry where hund means 'hound', 'dog', or to the entry where hund means 'hundred', depending on the meaning of the word in its concrete context.

Another problem is a purely Anglo-Saxon issue, which also had to be addressed while implementing the project. The point is that many Old English words are attested in their different variant forms. This is due to the fact that Old English as a language and its literature developed over several centuries, so it is only natural that Anglo-Saxon texts reflect the diachronic evolution of Old English in its morphology and vocabulary. Besides, these texts are written in various regional varieties of Anglo-Saxon (traditionally referred to as dialects), such as West Saxon, Anglian (Northumbrian and Mercian), and Kentish. This fact also adds to the multiplicity of spelling variants of Old English words. For instance, Anglo-Saxon noun xcer (meaning "field" or "acre") may occur in different texts (or even in one and the same text) in its variant spelling forms like xcyr or acer. Pronoun célc (Modern English "each") is often spelt also as elc, ealc or ylk. Noun frip (which means "peace; truce") is attested in a variety of spelling forms such as frio, fryp, fryö, friopu, frioöu, freopu and so on. This very abundance of spelling variants caused certain difficulties which had to be addressed somehow. The said difficulties were associated both with the disambiguation of homonyms and with the lemmatization of tokens, since it was necessary to determine initial forms for various words occurring throughout seven Anglo-Saxon texts in many different spelling varieties. These initial forms coincide with the word forms/lemmas, chosen for the headwords of respective dictionary entries of the Chrestomathy.

6. Prospects for the Development and Sustainability of the Chrestomathy

With the ever increasing availability of the Internet, computers, digitalized devices, electronic databases and mobile technologies, the application of digitalized, web-based, computationally engaged research, scientific and teaching resources logically becomes advisable and even necessary.

Working in the field of Germanic languages and comparative linguistics, we could not oversee this necessity of the use of digital technologies in the pursuit of our scholarly and academic activities.

The advantages (as we see them) of the application of digital tools in the process of the acquisition of Gothic and Anglo-Saxon languages were demonstrated above. The above-described method allows a reader to quickly process and "digest" substantial amounts of morphological and lexico-semantic information using multiple blocks of grammatical data integrated into the single digital resource. This method allows avoiding the waste of time and energy on the mind-numbing "navigation" through the seas of pages of printed volumes, as it was inevitable with the use of older non-digital textual resources. This is especially important in case of old/dead languages, which by definition do not allow of the use of any form of immersion methods or interaction with native speakers. Reading daily more pages of the texts written in old languages guarantees the easier memorization and better mastery of the languages available exclusively in the form of written records.

In the future, Lexicographic Centre at TSU plans to work on the composition of similar web-based readers/chrestomathies for the texts in other linguistically important languages such as Old Icelandic, Old High German and Old Frisian. To this end, we are holding some preliminary talks with certain Icelandic and Frisian academic and research institutions, as well as with individual scholars, about the possible cooperation in this field.

We also do not rule out the possibility of composing, in the not so distant future, similar web-based educational resources also with respect to linguistically and scientifically important Indo-European languages like Lithuanian, Avestan and Sanskrit.

In this regard it should be mentioned that Tbilisi State University has a longstanding tradition of teaching ancient Indo-European languages: back in the 1920s, Avestan and Sanskrit were taught at TSU on the initiative of a prominent Georgian linguist Giorgi Akhvlediani, who had composed the Avestan and Sanskrit textbooks. It is our ambition to try to revive the tradition of studying and teaching these important languages at TSU.

There are also other plans with regard to the Gothic and Anglo-Saxon Chrestomathy discussed in the present article, as well as to our prospective web-based resources involving other languages. We expect that the English interface, making the web-based educational resources accessible to an international scholarly audience and general public, will facilitate and encourage their use by foreign students and can help Georgia become a regional centre for the study and teaching of these languages. The substantial improvement of the level of teaching Gothic, Anglo-Saxon and other linguistically significant languages, as well as the establishment of an entire school of trained specialists in the field of old Indo-European languages and comparative linguistics will be another substantial benefit brought about by the successful implementation of the project(s).

Finally, another possible application of the digital readers/chrestomathies is that this same method can be equally successfully used for the acquisition of proficiency in contemporary, "living" languages. Our native Georgian for example, at least in some of its aspects, is known to be quite difficult to learn. Foreigners find the structure and morphology of Georgian verbs particularly difficult to adequately study and master (cf. Shanidze 1973; Holisky 1979; Gip-pert 2016). We believe that digitalized, integrated readers comprising texts in Georgian or other notoriously difficult languages like Hungarian or Finnish, for instance, could greatly facilitate the acquisition of such languages. Georgian texts with all words hyperlinked to their respective dictionary entries, providing in their turn additional information on the peculiarities of morphology of the words in question could greatly help foreigners consolidate their theoretical knowledge of the Georgian grammar and transform it into practical awareness of the laws and regularities of the contemporary Georgian language. In particular, the use of digitalized Georgian readers would make the task of mastering the conjugation of extremely versatile and multiform Georgian verbs much easier and much more feasible for foreign learners of Georgian.

7. Some Lexicological Aspects of the Project

The Chrestomathy discussed above, combines two main aspects of scholarly activities of the authors of the present article: Germanic philology and Lexicography. One more sphere of our interest is the issue of semantic equivalence and anisomorphism between the synonyms from different languages. Many prominent specialists in the field of lexicography and linguistics have expressed their views on the subject of equivalence of synonyms in various languages (cf. Adamska-Salaciak 2010; Gouws and Prinsloo 2008; Hartmann 2007; Zgusta 1971, 2006). Without the adequate realization of the fact that synonyms are not always fully equivalent, it is practically impossible to find the best translation and give proper definition to a word from the source language within a dictionary word-entry, as it has often been discussed in the papers of renowned lexicologists (cf. Geeraerts 2010; Hausmann 1985; Katz and Postal 1964).

Working on the Gothic component of the Chrestomathy, editing and perfecting Gothic-Georgian dictionary and analyzing the text of Gothic Gospels, we could not fail to note how linguistically interesting it would be to find out how much equivalent the synonymous words used in the Gothic, Greek, Latin, Old Georgian and English versions of the New Testament really were. This vision of the Gothic texts motivated us to supplement the entries of the Gothic-Georgian and Gothic-English dictionaries with the special section, the aforementioned Concordance feature, containing information about occurrences of this or that Gothic word throughout the surviving Gothic texts. This information is meant to help us in the future in "tracking" Gothic words in specific contextual surroundings in order to identify their matches in Old Georgian, Greek or Latin translations of the New Testament and help us determine the degree of their equivalence.

Using the information on the contextual occurrences of the Gothic lexical units, it is planned to dedicate a special research to the analysis of the issues of semantic equivalence which the Gothic, Georgian or other translators of the New Testament must have had to address. Our experience with various (Gothic first and foremost) translations of the Scripture has convinced us that such an analysis will yield interesting results from the general linguistic, lexicological, lexicographical, cultural and other points of view.

One interesting example could be the comparison of a well-known passage from Matthew 6:28, where Gothic gakunnaip blomans haipjos (literally "perceive the flowers of the heath/field") corresponds to the Latin "considerate lilia agri" in Clementine Vulgate, Greek καταμάθετε τα κρίνα τοΰ άγροΰ("learn thoroughly/ examine/consider the lilies of the field") and the Old Georgian განიცადენით შროშანნი ველისანი (literally "perceive/experience the lilies of the field/valley"). It is especially interesting to note the parallelism between Gothic gakunnan and Old Georgian განცდა (both verbs meaning approximately "to perceive", "to get to know" or "to experience" ), remembering that the majority of modern translations of this excerpt have something like "see/observe/look at the lilies of the field". No less interesting is the semantic anisomorphism between the Gothic blomans ("flowers") on the one hand and Latin, Greek and Old Georgian lilia, κρίνα, შროშანნი("lilies") on the other hand.

Similar and even more interesting results can be obtained after the deep analysis of the usage of Gothic words in the surviving chapters of Gospels and other Gothic texts, which analysis will be conducted based on the Concordance feature of the web-based Chrestomathy.

8. Conclusion

This is in brief what we wanted to share with colleagues from lexicographical, lexicological and linguistic community about the digitalized Chrestomathy. We thought that the information about this educational and research resource was worth making public for various reasons: (1) the Chrestomathy will increase the interest of students in studying Gothic and Anglo-Saxon; its English interface makes this online resource globally available for those who are interested in these two linguistically important old languages and, generally, in language diachrony and comparative linguistics; (2) as far as old/"dead" languages are concerned, the Reader will enable a user easily to consolidate his/her knowledge of the languages which are no longer in use; (3) the Chrestomathy allows to scientifically analyze the vast blocks of data pertaining to old languages (Gothic, Anglo-Saxon), since all primary and auxiliary texts/data included therein are represented in electronically searchable format; (4) furthermore, the Resource has the potential to facilitate the composition of similar resources with respect to extant/"living" languages. Chrestomathies based upon the method applied in the online resource described above can be successfully used for mastering morphologically complex (mostly synthetic) languages characterized with the abundance of inflectional and suppletive forms, such as Hungarian, Turkish, Russian, German, Georgian and many others. Web-based chrestomathies similar to the one described in the present article, allowing the instant identification of the lemmas of each allomorph occurring throughout the texts, could be very useful and reliable digital tools for the mastery of the languages of the said type; (5) especially with respect to Anglo-Saxon (which is the earlier form of modern English language) the Chrestomathy facilitates the tracking and analysis of the processes of linguistic change and allows one to arrive at certain generalized conclusions concerning language diachrony; and finally (6) the Concordance feature, provided for the Gothic section of the Chrestomathy allows researchers to study and analyze the problem of semantic equivalence, which is universally relevant and important already on the synchronic level of language research and analysis. All these features, as we think, make the online resource interesting and noteworthy both from theoretical and practical points of view.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank their colleagues, participants of the project presented above, who have contributed to its successful implementation. These are (in alphabetical order) Malkhaz Abuladze (the compiler of Gothic-Georgian and Anglo-Saxon-Georgian dictionaries included in the Chrestomathy), Maia Davlianidze (technical assistant) and George Kerechashvili (programmer, web developer, software specialist).

References

Adamska-Salaciak, A. 2010. Examining Equivalence. International Journal of Lexicography 23(4): 387-409. [ Links ]

Althochdeutsches Wörterbuch. Sächsische Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Leipzig. Accessed at: http://awb.saw-leipzig.de [28/01/2019].

Anglo-Saxon Dictionary (digital edition). Bosworth-Toller Anglo-Saxon Dictionary. Accessed at: http://bosworth.ff.cuni.cz/ [26/01/2019].

Buchi, É. 2006. Etymological Dictionaries. Durkin, Ph. (Ed.). 2006. The Oxford Handbook of Lexicography: 338-349. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Chemodanov, N.S. 1978. Chrestomathy in the History of the German Language. Moscow: Vysshaya Shkola. (In Russian) [ Links ]

Durkin, Ph. 2009. The Oxford Guide to Etymology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Geeraerts, D. 2010. Theories of Lexical Semantics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Gippert, J. 2016. Complex Morphology and its Impact on Lexicology: The Kartvelian Case. Margalitadze, T. and G. Meladze (Eds.). 2016. Proceedings of the XVIIEURALEX International Congress: Lexicography and Linguistic Diversity, 6-10 September, 2016, Tbilisi, Georgia: 16-36. Tbilisi: Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University. http://euralex.org/category/publications/euralex-2016/.

Gothic Online. The Linguistics Research Center, The University of Texas at Austin College of Liberal Arts. Accessed at: (https://lrc.la.utexas.edu/eieol/gotol/10) [31/01/2019].

Gouws, R.H. and D.J. Prinsloo. 2008. What to Say about "manana", "totems" and "dragons" in a Bilingual Dictionary? The Case of Surrogate Equivalence. Bernal, E. and J. DeCesaris (Eds.). 2008. Proceedings of the XIII EURALEX International Congress, Barcelona, 15-19 July 2008: 869-877. Barcelona: Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Institut Universitari de Lingüística Aplicada.

Gukhman, M.M. 1958. Gothic Language. Moscow: Izdatelstvo literatury na inostrannykh yazykakh. (In Russian)

Hartmann, R.R.K. 2007. Interlingual Lexicography: Selected Essays on Translation Equivalence, Contrastive Linguistics and the Bilingual Dictionary. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer. [ Links ]

Hausmann, F.J. 1985. Lexikographie. Schwarze, Christoph and Dieter Wunderlich (Eds.). 1985. Handbuch der Lexikologie: 367-411. Königstein/Ts.: Athenäum. [ Links ]

Holisky, D.A. 1979. On Lexical Aspect and Verb Classes in Georgian. Clyne, Paul R., Hanks, William F. and Carol L. Hofbauer (Eds.). 1979. The Elements: A Parasession on Linguistic Units and Levels Including Papers from the Conference on Non Slavic Languages of the USSR: 390-401. Chicago : Chicago Linguistic Society. [ Links ]

Katz, J.J. and P.M. Postal. 1964. An Integrated Theory of Linguistic Descriptions. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Krause, W. 1951. Die Sprache der urnordischen Runeninschriften. Heidelberg: Carl Winter Universitätsverlag. [ Links ]

Margalitadze, T. and G. Meladze. 2016. Importance of the Issue of Partial Equivalence for Bilingual Lexicography and Language Teaching. Margalitadze, T. and G. Meladze (Eds.). 2016. Proceedings of the XVII EURALEX International Congress: Lexicography and Linguistic Diversity, 6-10 September, 2016, Tbilisi, Georgia: 787-797. Tbilisi: Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University. http://euralex.org/category/publications/euralex-2016/.

Project Wulfila (a small digital library dedicated to the study of Gothic and Old Germanic languages, hosted by the University of Antwerp, Belgium). Accessed at: http://www.wulfila.be/ [30/01/2019].

Shanidze, A. 1973. Foundations of Georgian Grammar. Tbilisi: Tbilisi University Press. [ Links ]

Smirnitsky, A.I. 1953. Chrestomathy in the History of the English Language from VII to XVII Centuries. Moscow: Izdatelstvo literatury na inostrannykh yazykakh. (In Russian) [ Links ]

Steblin-Kamensky, M.I. 1955. Old Icelandic Language. Moscow: Izdatelstvo literatury na inostrannykh yazykakh. (In Russian) [ Links ]

The Gothic Language. Uppsala University Library. Accessed at: (http://www.ub.uu.se/about-thelibrary/exhibitions/codex-argenteus/the-gothic-lanuage/) [31/01/2019].

Zgusta, L. 1971. Manual of Lexicography. Prague: Academia / The Hague: Mouton. [ Links ]

Zgusta, L. 2006. Lexicography Then and Now: Selected Essays. Edited by Fredric S.F. Dolezal and Thomas B.I. Creamer. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer. [ Links ]

1. As an explanatory note, it should be mentioned here that the Chrestomathy is due to be completed by the end of 2019 when all of its programmatic features will be fully functional.

2. This online resource includes about ten Gothic texts/fragments from Codex Argenteus and Skeireins; texts are morphologically and semantically analyzed on sentence-by-sentence basis; some basics of Gothic grammar are also supplied.

3. It is worth mentioning however, that homonyms in many cases are not disambiguated. This is, most likely, due to the reliance on the text analyzer using relatively general algorithms.

4. Matthew 8; Matthew 27; Mark 15; Luke 15; John 18; Corinthians I, 15

5. Ælfric's Genesis XXVII, 1-29; Bede on Britain (Geographical description of Britain by Bede the Venerable); Csdmon - Story and Hymn (Bede's narrative about Gedmon and his famous hymn); Béowulf (several excerpts from the poem); The Coming Of The English (Bede's description of the coming of the English to Britain); Ohthere's Account (Account of a 9th century Norwegian seafarer Ohthere about his voyages which he gave to King Alfred the Great of Wessex); An Excerpt From Old English Chronicles (from Parker Manuscript)