Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Lexikos

On-line version ISSN 2224-0039

Print version ISSN 1684-4904

Lexikos vol.28 Stellenbosch 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.5788/28-1-1457

ARTICLES

Corpus-driven Bantu Lexicography Part 1: Organic Corpus Building for Lusoga

Omutengeso gw'eitu ogukozesebwa mu namawanika w'ennimi dha Bantu. Ekitundu 1: Okuzimba namukyukilo w'eitu ly'Olusoga

Gilles-Maurice de SchryverI, II; Minah NabiryeIII, IV

IBantUGent, Department of Languages and Cultures, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium

IIDepartment of African Languages, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa (gillesmaurice.deschryver@UGent.be)

IIIBantUGent, Department of Languages and Cultures, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium

IVDepartment of Teacher Education and Development Studies, Kyambogo University, Kampala, Uganda (minah.nabirye@UGent.be)

ABSTRACT

This article is the first in a trilogy that deals with corpus-driven Bantu lexicography, which is illustrated for Lusoga. The focus here is on the building of a so-called 'organic corpus' from scratch, while the next two instalments will deal with the use of that corpus on the macrostructural and microstructural levels, respectively. Not many detailed descriptions of corpus-building efforts exist for Bantu languages, so each and every step is discussed in detail, paying particular attention to the parameters that have to be taken into account, while not losing sight of the need to log the metadata either.

Keywords: bantu, lusoga, corpus building, organic corpus, oral, written, source, period, genre, topic, metadata

OBUFUNZE

Olupapula luno n'olusooka ku isatu edhinaayogela ku musomo gw'omutengeso gw'eitu ogukozesebwa mu namawanika w'ennimi dha Bantu nga gulaga omulimu ogw'akolebwa ku Lusoga. Mu lupapula luno, eisila lili ku nzimba ya itu namukyukilo okuva ku ntandiiko. Ebitundu ebinaaba mu lupapula olw'okubili n'olw'okusatu biidha kugema ku nkozesa ya itu lino ku isa ly'omutindiigo ogw'ebizimbibwa mu mutegeko n'eisa elilaga eitu lino mu mwoleko ogw'azimbibwa mu mutindiigo n'engeli omusingi ogulimu bwe gulagibwa mu iwanika. Mu nnimi dha Bantu, emilimu egilaga omusingi guno tigitela kuwandiikibwaku mu butongole okusobola okumanhisa abo abayinza okuba nga bagasibwa. Kale buli kitundu ekiteesebwaku mu nnambika eli mu mpapula eisatu dhino kitoolayo buli kanhomelo ka bukodyo n'emitendela egy'agobelebwa ela gy'akozesebwa mu kusenvula omulimu gw'okuzimba omutimbo gw'ekyebungo ky'olulimi Olusoga gwonagwona.

Ebigambo ebikulu: bantu, lusoga, okuzimba eitu, eitu namukyukilo, endhogela, empandiika, obuvo, ekiseela, ennambika, ekinhumyo, omutimbo gw'ekyebungo

1. Goal of the present study

In this article we wish to show how an electronic corpus for a Bantu language, especially an under-resourced Bantu language, may be assembled from scratch. We have lexicographic applications in mind, but such corpora may also be used (and have successfully been used) for Bantu corpus linguistics studies more generally. While Bantu corpora have been built for about two decades now, explicit descriptions of their composition are rare in the literature. For instance, in his MA dissertation de Schryver (1999: 103-117) devotes about 14 pages to the design, structure, contents and text collection of a 300 000-word Cilubà corpus, but to this date that study remains unpublished. When it comes to the descriptions of the corpora that have been assembled for the South African Bantu languages, these are typically less than a page long (de Schryver and Prinsloo 2000). On the other hand, corpus stability tests have been carried out for the South African Bantu languages (Prinsloo and de Schryver 2001, Prinsloo 2015), as well as attempts at multilingual corpus building and multilingual data extraction (de Schryver 2002, Prinsloo and de Schryver 2005). Scientific articles on the Zimbabwean corpora built under the umbrella of ALLEX/ALRI tend to focus on specific topics, such as tagging issues for a Shona corpus (Chabata 2000) or the sociolinguistic, political and economic considerations that influence the contents of a corpus of Zimbabwean Ndebele (Hadebe 2002). Even the latest version of the widely-used Helsinki Corpus of Swahili is not accompanied by a proper description (Hurskainen 2016).

The only exceptions to this pattern seem to be the corpora built to carry out corpus linguistics studies at BantUGent (i.e., the UGent Centre for Bantu Studies) where, for instance, the PhDs of Mberamihigo (2014), Nshemezimana (2016) and Misago (2018) describe the various Kirundi corpora built, or where the PhD of Kawalya (2017) describes the Luganda corpus that he used for his study. The building of a Lingála corpus may be found in the PhD of Sene-Mongaba (2013), reworked and expanded as Sene-Mongaba (2015). Our effort (Nabirye 2016), on which the Lusoga case study presented below is based, is also the result of PhD research undertaken at BantUGent.

With regard to corpus-building efforts for Lusoga, only one exploratory study has appeared so far (Nabirye and de Schryver 2011). In that study, the main focus was on the writing problems that the corpus builder encounters during the transcription of oral material and the implications for the corpus lexicographer when data is extracted from such a corpus. In contrast, of particular interest in the present study will be the parameters/axes that can be used to characterise the composition of a Bantu-language corpus, these being, in addition to oral vs. written, also the distribution of the sources, the periods, the genres and the topics. Orthographic issues will only briefly be recapped here. Furthermore, the value of detailed corpus documentation will be exemplified; this will be done by means of the inclusion of and reference to a comprehensive addendum. Corpus-query software will be mentioned in passing.

2. The Lusoga language and publications in Lusoga

Lusoga is a largely undocumented Great Lakes Bantu language classified as JE16 (Guthrie 1948, Maho 2009). According to the Uganda Bureau of Statistics, 2 062 920 people identified themselves as Basoga in 2002 (UBOS 2006: 12), a figure that grew by nearly half to a respectable 2 960 890 by 2014 (UBOS 2016: 71). While immediately acknowledging that not all people who claim to be Basoga also necessarily speak 'Lusoga', however defined,1 one should still realise that several million people currently speak Lusoga, of which about two million are monolingual. While it might surprise that a language with up to three million speakers may be largely undocumented, it is fitting to recall that there are even endangered languages with millions of speakers (Adelaar 2014).

Lusoga was first reduced to writing near the end of the 19th century, as pointed out by Condon a century ago:

The Basoga Batamba had no written characters. Nor do any writings on rocks or pictorial characters exist. According to native report - and I mean natives of a ripe old age - there never was, as far as they remember, any means whatever of placing down their verbal utterances. All messages from one chief to another were committed to a trustworthy man, who learned the communication by heart, and so delivered the message by word of mouth. It is only within the last 15 years that the language of this people has been put in book form. (Condon 1911: 368)

The very first language data for Lusoga may be found in the 'vocabularies' included in Johnston (1902: 980-991) as well as in Condon (1911). However, we have found no evidence to suggest that Lusoga was documented in earnest prior to the 1960s. The earliest reference uncovered so far with an exclusive focus on Lusoga is the orthography of Byandala (1963). That booklet was followed by the documentation of Lusoga proverbs and riddles in Lyavala-Lwanga (1967, 1969). There is no record of Lusoga materials produced during the 1970s or the 1980s. Writing on and in Lusoga was again picked up in the 1990s. The first Lusoga publication in this period was the second version of the Lusoga orthography: Kajolya (1990). It was followed by two attempts at publishing a newspaper, which faltered shortly after: Kodh'eyo (1997-98) and Ndimugezi (1998-99). From the late 1990s and early 2000s onwards, the main output in Lusoga has come from the Cultural Research Centre (CRC), a religious body based in Jinja (e.g., CRC 1998a, 1999a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, 2000a, b, 2002, 2005a, Kaluuba et al. 2010, CRC 2011).2 Also, one very prolific writer is Gulere who, amongst others, self-published ten children's story books, which he placed online in various locations at various times and in various formats (Gulere 2011a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j). Gulere moreover self-published two translations, one of Antigone, a tragedy by the ancient Greek playwright Sophocles from 441 BC (Gulere 2007a), another of The Bride, a play in English by the Ugandan Austin L. Bukenya from 1987 (Gulere 2007b).3 Lastly, a first novel has now been published in Lusoga, written by Kuunya (2011a).

3. Building a corpus for Lusoga

3.1 Towards an organic (but structured), general-language, synchronie Lusoga corpus

The basics of corpus building for the Bantu languages have been described by de Schryver and Prinsloo (2000). The two important concepts that also applied to the building of our Lusoga corpus are that of an 'organic corpus' and that of a 'structured corpus'. An 'organic corpus' has been defined by Atkins, Clear and Ostler as follows:

[...] a corpus may be thought of as organic, and must be allowed to grow and live if it is to reflect a growing, living language. [...] In order to approach a 'balanced' corpus, it is practical to adopt a method of successive approximations. First, the corpus builder attempts to create a representative corpus. Then this corpus is used and analysed and its strengths and weaknesses identified and reported. In the light of this experience and feedback the corpus is enhanced by the addition or deletion of material and the cycle is repeated continually. [...] In our ten years' experience of analysing corpus material for lexicographical purposes, we have found any corpus - however 'unbalanced' - to be a source of information and indeed inspiration. Knowing that your corpus is unbalanced is what counts. (Atkins et al. 1992: 1, 4, 6)

De Schryver and Prinsloo link this to what they call a 'structured corpus' as follows:

Formulated differently, it is any corpus compiler's task to attempt to assemble a representative corpus for his/her specific need(s). Subsequent additions and deletions of sections should be seen as a balancing activity to rectify initial weaknesses, but more importantly, also to take account of and track a growing, living language. As such, there is no such thing as 'the' corpus of a certain language (variety). Rather, at any point in time one selects a certain number of texts from the range of available electronic texts (which might or might not be grouped together into sub-corpora), and uses 'a' corpus for the specific research one wishes to pursue. The minimum requirement for any organic corpus is thus that the corpus compiler(s) will have attempted to put some structure in assembling the range of electronic texts. Within this framework, any first attempt at compiling an organic corpus will at least result in a structured corpus. (de Schryver and Prinsloo 2000: 92)

Our Lusoga corpus is both structured and organic. On the whole, the organicity means that the overall size has increased and decreased over the years.

Corpus building for the Bantu languages is always slightly opportunistic, in that one adds the little existing written material one can get hold of, except when a serious imbalance results. In other words, to get going, one often makes do with an 'imperfect corpus', which is then modified later on, when 'better' data becomes available. Over and above this balancing act, the corpus used should always attempt to be representative of the population that is the subject of the planned description or research. For a general-language corpus, the goal is consequently to acquire as many different genres as possible, that deal with as wide a topic range as possible. Existing written material for all but a few Bantu languages is unfortunately biased in this respect. Most are the result of (modern) missionary activities, so the genre Biblical documents tends to be over-represented in many Bantu corpora. Conversely, for Bantu languages with a varied, vibrant and ongoing online media presence, the genre Journalism may be overrepresented, and within that, topics such as Sports and Politics. Of course, when the aim is to describe features of biblical works or journalistic texts, then such types of corpora may indeed be 'representative', and when multiple sources have been equally sampled, these corpora may also be 'balanced'. But if the goal is to describe the general language, then an effort needs to be made to achieve both representativeness and balance in another way. It is here that the material found in the oral component of a corpus may bring a solution, as it did for our Lusoga corpus (cf. infra, §3.5.1).

Another important point concerns the time period covered by a Bantu corpus. In all but a few cases, this will be 'the present', with that present optionally stretching back to a number of decades, maximum half a century. Although attempts are being made to build Bantu corpora with time-depths of at least half a century down to a century - such as for Zulu (de Schryver and Gauton 2002), Kirundi (Mberamihigo et al. 2016) and Luganda (Kawalya et al. 2018) - the only Bantu corpus containing substantial amounts of diachronic data that has been built (and used)4 is the set of corpora for the Kikongo Language Cluster, where some parts are up to four centuries old, while others go back to around 250 years ago (Bostoen and de Schryver 2015). For Lusoga, the aim has always been to build a synchronic corpus covering the general language. Material older than a few decades is in any case extremely rare for Lusoga (cf. supra, §2). When available, it was nonetheless included in an attempt to widen the genre/topic range.

3.2 The 0.5m Lusoga corpus

A first Lusoga corpus, of about half a million words, was built as part of the research leading to an MA dissertation. Its composition is as shown in Table 1 (adapted from Nabirye (2008: 70)).

3.3 The 0.9m Lusoga corpus

For a corpus-based study of the Lusoga noun (de Schryver and Nabirye 2010) the Lusoga 'MA corpus' was supplemented with the full text of the Eiwanika ly'Olusoga (Nabirye 2009), being a monolingual Lusoga dictionary compiled without the use of a corpus. The reasoning at the time was that because the example sentences from that dictionary were the result of original fieldwork, they could as well form part of a Lusoga corpus. A number of reports written in Lusoga (from the Busoga clan leaders, the private sector, academia, etc.) were also added, as was the initial impetus for a true oral part of the Lusoga corpus (i.e., the first few transcriptions of conversations, interviews and songs). The make-up of this Lusoga 'noun corpus' is as shown in Table 2 (taken from de Schryver and Nabirye (2010: 100)).

This version of the Lusoga corpus contained about 870 000 running words (tokens), and about 150 000 orthographically different words (types). Not only the transcriptions of conversations, interviews and songs but also the dictionary examples (together close to a third of the total) could be considered reductions of spoken data to text; the other genres being written texts from the start. From Table 3 (also taken from de Schryver and Nabirye (2010: 100)) one may further deduce that most sources are recent to very recent, with over 98% produced during the past two decades.

3.4 The 1.1m Lusoga corpus

Following the Lusoga noun study, and with the acquisition of more data to compensate for it, the dictionary data was again dropped from the Lusoga corpus. Although based on natural language production, the dictionary examples lacked the original context, and had in any case been 'selected' for their pedagogical value. As such, they did not have their place in a proper text corpus, that is, one that consists of large sections of free-flowing, running text. Instead, the symbolic oral section of about 6 000 tokens in the Lusoga 'noun corpus' was enlarged to well over 400 000 tokens. Furthermore, various texts translated from English, as well as digital-born Lusoga material, were also added, to obtain the corpus that was used for the study of the writing problems in a Lusoga corpus (Nabirye and de Schryver 2011). The composition of that new corpus is as shown in Table 4 (adapted from Nabirye and de Schryver (2011: 123)).

This 1.1m Lusoga 'writing-problems corpus' - just as the earlier 0.9m Lusoga 'noun corpus' and the even earlier 0.5m Lusoga 'MA corpus' - was not annotated for any linguistic features. As such, these corpora were not tagged for parts of speech, nor lemmatised. They are known as 'raw corpora'.

3.5 The 1.7m Lusoga corpus

The latest iteration of the Lusoga corpus stands at over 1 700 000 tokens and about 200 000 types. The various text files of the 1.1m Lusoga 'writing-problems corpus' were cleaned up, re-assembled and renamed. New material was added for each genre except Journalism. For the latter, however, all the newspaper clippings were reprocessed with better software (cf. infra, §3.5.2). It is this version of the Lusoga corpus that we will now study in more detail.

3.5.1 Oral vs. written distribution

In contrast to the 0.5m Lusoga corpus, which had no transcribed text, and the 0.9m one with just 5 716 such tokens, a major effort in building the 1.7m Lusoga corpus went to expanding the oral component even further compared to the 1.1m Lusoga corpus. While the model of all modern corpora, the 100m British National Corpus (BNC 1994-2018), has set the standard for general-language corpora to contain 10% spoken material vs. 90% written material (Rundell and Stock 1992: 46), we managed to triple this conventional allocation of the spoken part in the total. In all, 216 audio files were transcribed, amounting to well over half a million tokens, as may be seen from Table 5, which corresponds to 31% of the total corpus, illustrated graphically in Figure 1.

There is nothing magic about attaining over half a million words of spoken data,5 nor about reaching a division of a third for oral vs. two-thirds for written data, but for a language which to this date is chiefly an oral language, it simply looked like a necessity in order to ensure that any explanations drawn from this corpus would also reflect real language usage. The oral component is sizeable enough so as to feature in every screenful of concordance lines, where oral and written material is instantly juxtaposed and may be cross-compared to make sure there are no differences between oral vs. written language use that would need to be reported.

What is true is that there is an addictive aspect to corpus building, so a goal was set to reach about '100 hours of audio'. Indeed, the 541 129 tokens of transcribed material correspond to exactly 98 hours, 42 minutes, and 38 seconds of audio files. Transcribing half an hour of audio took on average two hours, which means that 400 hours were required for all the transcriptions (not counting the fieldwork and hours spent recording in the first place, nor the many hours to collect and log all the metadata and consent forms). The types of audio recorded and transcribed are varied, and include modern and traditional songs, radio talk shows, traditional ceremonies (as currently being performed), business meetings, interviews and dialogues.

3.5.2 Source distribution

The bulk of the written part of the 1.7m Lusoga corpus was assembled through the digitization of more or less every work, down to every snippet, ever written and published in Lusoga, whether commercially or produced as grey literature. A total of 85 sources were scanned in high resolution, after which the optical character recognition (OCR) tool of OmniPage (1995-2018) was utilised to turn the images into machine-readable texts.6 These 85 sources were good for about 670 000 tokens. OCR was also used to re-digitise large parts of the two shortlived Lusoga newspapers: Kodh'eyo: Busoga etebenkere (Kodh'eyo 1997-98) and Ndimugezi n'omukobere: The factfinder (Ndimugezi 1998-99). Due to the poor quality of the printing of these newspapers, the OCR output required substantial clean-up. The result was about 200 000 tokens of newspaper articles. A further 62 files were obtained electronically. These included self-published works found on the Internet, unpublished material from friends, private e-mail and mailing list communications, translations into Lusoga taken from government, NGO and commercial websites, as well as some religious material found online. All these texts together came to about 260 000 tokens. The translations we ourselves had made over the years, 15 of them, were also added, which contributed a further 25 000 tokens, as well as some of our own writings, six texts with just 2 500 tokens. The remainder consisted of low-resolution images of texts found online, as well as a single hand-written document, which were all retyped, adding another 25 000 tokens.

An overview of these various sources may be seen in Table 6. For a mostly undocumented and oral language like Lusoga, we must admit that we never expected to be able to reach nearly 1.2m tokens of material that had been written in one way or another. Extending the corpus building effort beyond the more obvious transcriptions and OCR, as seen in the last five bullets of Table 6, clearly helped in this regard (and in effect resulted in about a quarter of the written data).

3.5.3 Period distribution

As may be seen from the data presented in Table 7 and the bar chart shown in Figure 2, the 1.7m Lusoga corpus is essentially a synchronic corpus with a time-depth of just over 20 years.

Only four files represent the 1940s, 1960s and 1980s.7 The 1990s and 2000s are equally represented, with about 400 000 tokens each, while the 2010s (and only up to August 2013 at that) is represented by as many as 850 000 tokens. While each of the past two periods and the present one cover both oral and written material, up to 70% of the transcriptions concern spoken data from the 2010s, which is the main reason why the 2010s contain more material than any other period. Another is the flurry of primers that were produced in the 2010s, in the wake of the recognition of Lusoga as a medium of instruction in 2005 (NCDC 2006: 5).

3.5.4 Genre distribution

The 391 files of the 1.7m Lusoga corpus were also grouped into 12 broadly-defined genres, as summarised in Table 8 and shown graphically in Figure 3. Three genres dominate, making up more than half the corpus: Biblical documents (23% of the tokens),8Literature (16%) and Radio talk shows (15%). Also sizable are Journalism (12%) and E-mails (9%). Each of the next five genres contains about a twentieth (5%) of the total corpus: Policy documents, Interviews, Songs, Celebrations, and Academic documents. Newsletters and Advertisements each represent less than 1% of the total.

3.5.5 Topic distribution

The different files in the Lusoga corpus were also grouped into 18 broadly-defined topics. To do so, related subjects were brought together, such as:

Health:

- Health planning

- Ill-health & death

- Rural health management

- Traditional healing

- AIDS scourge

- Eye-care education ...

Inspirational:

- Self-appreciation

- Jubilation

- Honouring activity

- Hope message

- Graduation ceremony ...

Even though a strict division between genre and topic is not always possible, and even though some files actually deal with various topics, the data shown in Table 9 may be considered to be a good approximation of the actual topics covered in the corpus.

While a quarter of the Lusoga corpus deals with Religion, the inverse also means that three-quarters does not, which is fine given the usual bias in Bantu-language corpora. The topic Networking actually covers such varied items as newspaper texts, mailing-list messages, songs about networking, and even advertisements. The other topic labels are self-explanatory. The data is shown graphically in Figure 4.

While the percentages for each of the broadly-defined topics as seen in Figure 4 may or may not reflect the actual allocation to each of these topics in the way Lusoga is used by millions of speakers on a daily basis in Busoga, what is relatively certain is that the coverage of the range and variation is rather wide in the 1.7m Lusoga corpus.

3.5.6 The orthography in the corpus

Important to observe at this point is that the various orthographies as seen in the original written sources were left intact. Bar a few exceptions, there are no tone markings in the corpus.

This implies that the stated number of types (i.e. the orthographically unique words) is always slightly inflated compared to a corpus in which the spelling would have been homogenised. Working with a corpus that contains various spellings for some of the same words is not an insurmountable hurdle; it only means that one is dealing with some (evenly spread) noise as far as the type counts are concerned; the token counts, however, are (mostly) correct.

Although a number of Lusoga orthography guides exist, one must conclude that they did not have much impact on helping the different authors streamline their writing in Lusoga. But then, the majority of the texts which are now in the corpus were not necessarily meant for formal usage, so their authors did not adhere to a strict application of any orthographic rules. For example, biblical prayer books are in-house documents that are only employed for the purposes of religious teaching. The different short stories and the novel in Lusoga have all been produced informally and are written in a style that the authors feel is most appropriate at the time of writing. E-mails and website texts in Lusoga display a severely unregulated use of written Lusoga. Also, the type of written Lusoga found in this category of sources is often mixed with English. In addition, Lusoga is borrowing sounds from neighbouring languages, such as the palatal nasal [μ] which is not an indigenous Lusoga sound. One also notices a switch between the voiced labio-velar approximant [w] and the velar fricative [Y]; and the fact that the Lusoga dental sounds are being relegated to neighbouring alveolar sounds (which are easier to pronounce for non-native speakers). Most prominent is an ongoing discussion on whether Lusoga really has a trill [r], only a flap [f], or neither of the two - which results in inconsistent uses of /r/ and /l/ in the orthography.10

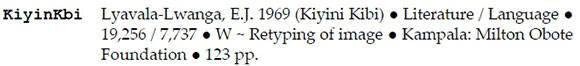

Instances of orthography-based problems in writing Lusoga are shown in examples (1) & (2). (For the abbreviations in the glosses, see the explanations at the end.)

In the examples in (1) the author decided to write the dental nasal as /nhy/, the voiced labio-velar approximant as /hw/, and the voiceless palatal plosive as /c/, as well as making distinctions in writing the trill after /i, e/ and the lateral flap after /u/ and /a/. The orthographic problems seen in examples of this nature seem to arise out of a need to use a phonetic-inspired orthography. Such orthographic interpretations may simply be idiosyncratic improvisations made in the absence of a proper (and popular) phonetic description of the sounds of Lusoga.

On the other hand, the examples in (2) reflect a user who is continuously code switching, and missing out on a few basic grammatical forms in the writing system. This is probably due to ignorance or the lack of a proper grounding in writing Lusoga.

The type of issues seen in the two examples can be generalised as occurring rather often in the informal written texts included in the corpus. While the spelling of the original texts was left intact, recognition errors might have been introduced during the OCR process, with some of the letters being machine unreadable and interpreted differently, even though we did our utmost to read through the OCRed material.

It is also probable that some 'errors' were introduced during the transcription process: while we tried to steer away from it, there was a tendency to 'over-correct' misspoken sections and hesitations, as the goal of our corpus-building efforts is not to use the material for, say, sociolinguistic studies of detailed turn-taking, but to use the material to uncover language as it was meant to be (Hanks 2012: 416).11

We do trust that these 'inconsistencies' and 'errors' have not obscured the proper usages of Lusoga.

3.5.7 Querying the corpus

The 391 files of the 1.7m Lusoga corpus are stored as plain text files, and as such this 1.7m Lusoga corpus is also a 'raw corpus'. Raw corpora may successfully be searched using off-the-shelf corpus-query software like WordSmith Tools (Scott 1996-2018). WST was indeed used in this way to present the various corpus counts above, and will also be used for the macrostructural and microstructural illustrations in the next two parts of this set of three articles.

However, and as we will explain in Part 2, the 1.7m Lusoga corpus was also part-of-speech tagged and lemmatised for lexicographic purposes. Either or even both of these levels (i.e., the part-of-speech labels and/or the lemmas of each orthographic word) may also be added as tags to all (or part of the) 1.7m tokens of the Lusoga corpus. Software such as WST is able to handle such marked-up text files as well.

3.5.8 Corpus file IDs, corpus filename bibliography and corpus metadata database

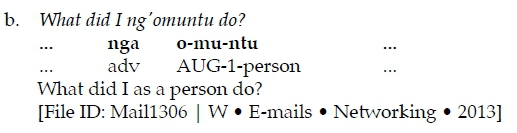

As could be seen in examples (1) and (2), for material excerpted from the corpus, it is good practice to mention the source from which it was taken. In (1) this information was presented following all the examples, and in (2) this was done on the line following the interlinear glossing and translation. In all cases, the corpus details are presented between square brackets.

In actual fact, for all material that is quoted from a corpus, whether for lexicographic purposes or more generally in corpus linguistics, three distinct levels of supplementary information may be provided for each source. At the quoted material itself a File ID may be provided, together with 'minimal information', here on whether the treated example is either taken from the written or the oral section of the corpus, and further information on the genre and topic, as well as the year or period, in the following format:

at examples

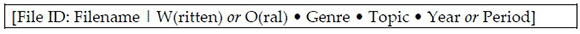

The Filename also serves as the entry point to Addendum 1, where further details on each source may be found. The author (or for audio, performer) as well as the title of the work (either as published or as given by us), the number of types and tokens for the work, the source of the work, the place of publication and publisher, as well as the number of pages of the work (or for audio, length of the recording) are all provided in that addendum. The format used for the twelve slots of information in Addendum 1 is always as follows:

in Addendum 1

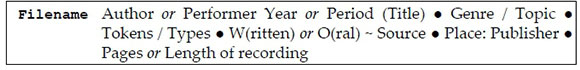

For instance, the Filename for (1) above reveals the following in Addendum 1:

This type of information includes what one would find in a traditional bibliography (before the first bullet, after the penultimate and last bullets), but adds corpus-specific information to that (all the rest in-between).

in the corpus metadata database

Addendum 1 is an extract from a larger database, which, for the written sources and when relevant, also includes the translator and date of translation, as well as the edition number and year of original publication. For the oral material, that database additionally includes the date of the recording, and the names of the recorders and transcribers. Lastly, for each source the standardised type-token ratio (with a base of 1 000) and the standard deviation thereof are also given.12

A notes field is used for any additional information that needs to be mentioned. This corpus metadata database, which brings together all the metadata of the corpus in a structured format, is available electronically and may be consulted at BantUGent together with the corpus itself.

3.5.9 Original data database

While it is feasible to store all of the 391 files in one single folder, much more intelligent is to arrange the files into various folders and sub-folders, for instance reflecting the different genres (12 sub-folders) or topics (18 sub-folders). How this is organised for a particular corpus depends on the use that will be made of that corpus. Another division could be oral vs. written, or the use of sub-folders that reflect the different time periods in the corpus, or even combinations of all of the above using tiered sub-folders. What has furthermore proven to be very useful is to keep several copies of the corpus at hand: in each, one finds the same data, but structured differently.

What is of paramount importance, however, is to keep a parallel version of one of these corpus structures in a different (off-site) location, where all the original files are kept. There the original audio (.wav, .mp3, ...) and at times even videos (.mp4, .webm, ...) are stored, as well as the original web pages (.htm, .html, ...), documents (.doc, .pdf, ... ) and images (.jpeg, .png, ...). Temporary files such as those used to turn scanned material ('image pdfs') with OCR software (e.g., .opd) into machine-readable images ('searchable pdfs') should also be kept there. This parallel version of the corpus, or original data database, not only functions as a backup from which the corpus files could be regenerated whenever this would prove to be necessary, but it is also the first place to go to whenever in doubt about a certain transcription (audio) or the orthography in an automatically-recognised (written) work. Published texts, with their formatting, and multimedia files furthermore contain more information than the text (.txt) versions in the corpus, which may at times and for certain purposes be useful to consult.

4. Discussion

In this article we have given a detailed description of the building of a general-language corpus for Lusoga, an under-resourced Bantu language. We showed that it is indeed possible to reach a substantial size, in this case 1.7 million tokens, a third of which consists of oral data, even though the building of this corpus has basically been a one- to two-person effort. This stands in sharp contrast to for instance the ALLEX/ALRI corpora, for which scores of students were sent into the field and as many were enlisted to transcribe the recordings.

Our corpus is an 'organic corpus', as material has not only been added over the years, but some of it has also been taken away, while still other parts were replaced after being reworked. Merely having more data does not necessarily mean one has better data, as one should keep an eye on balance as well. In the overview presented in the present article, the 1.7m Lusoga corpus is a 'raw corpus', in that it has not been annotated; but it was pointed out that with the results from Part 2, part-of-speech tags and/or lemma tags could enrich this corpus linguistically.

We also illustrated the importance of knowing one's corpus, not only in terms of the oral vs. written distribution, but similarly with regard to the distribution of the sources, periods, genres, and topics. Variations on our presentation are of course possible, and indeed in the PhDs of Mberamihigo (2014), Nshemezimana (2016) and Misago (2018) for Kirundi, as well as the PhD of Kawalya (2017) for Luganda, three-dimensional graphs are shown in addition, the third dimension representing the diachronic aspects of their corpora. The point, however, is that a detailed description of a corpus is needed if one is to make intelligent use of it.

As the details in the addendum indicate, we further place particular importance on the metadata of a corpus. Metadata may evidently be put to good use when actually using a corpus: for lexicographic ends, but also far beyond in the wider discipline of linguistics. There are no doubt differences between the spoken and the written forms of a language, and certain phenomena may be realised slightly differently depending on the genre or topic, just as word use differs with register. Likewise, for differences in word use depending on the author or performer, or even the publishing house of a certain work (each with their own style guide and own approach to copy-editing), and so on. Sub-corpora may indeed be assembled along such lines.

Reformulated, depending on how one intends to use a corpus, all the categorisations given so far may play an important role. But they do not inform each study in the same way. Within the field of lexicography, the first two and main uses of a corpus have to do with the creation of the macrostructure of a dictionary on the one hand, and the compilation of the articles in the microstructure on the other. These two topics will now be looked into, and illustrated for Lusoga, in two follow-up studies.

Abbreviations

# noun class number FV final vowel

ADV adverb SG singular

AUG augment SMx subject marker (of cl. or cl. class person x)

CON connective

Acknowledgements

The research for this article was funded by the Special Research Fund of Ghent university. Thanks are due to the two anonymous referees.

References

Adelaar, W.F.H. 2014. Endangered Languages with Millions of Speakers: Focus on Quechua in Peru. JournaLIPP 3: 1-12. [ Links ]

Atkins, B.T.S., J. Clear and N. Ostler. 1992. Corpus Design Criteria. Literary and Linguistic Computing 7(1): 1-16. [ Links ]

BNC. 1994-2018. British National Corpus. Available online at: http://www.natcorp.ox.ac.uk/.

Bostoen, K. and G.-M. de Schryver. 2015. Linguistic Innovation, Political Centralization and Economic Integration in the Kongo Kingdom: Reconstructing the Spread of Prefix Reduction. Diachronica 32(2): 139-185 + 13 pages of supplementary material online. [ Links ]

BSU. 1994. Mariko Omutwe Ogwokuna n'Ogwokutaanu mu Lusoga [A Selection from St. Mark's Gospel Chapters 4 and 5 in Lusoga]. Kampala: The Bible Society of Uganda. [ Links ]

BSU. 1996. Mariko. Amawulire Amalungi mu Lusoga [The Gospel of Mark in Lusoga]. Kampala: The Bible Society of Uganda. [ Links ]

BSU. 1998. Endagaano Empyaka [New Testament]. Kampala: The Bible Society of Uganda. [ Links ]

BSU. 2011. Endagaano Empyaka ni Zabbuli [New Testament and Psalms]. Kampala: The Bible Society of Uganda. [ Links ]

BSU. 2014. Baibuli. Ekibono kya Katonda. Omuli n 'ebitabo ebyetebwa deuterokanoniko/apokurifa [Bible. The Word of God, Which Also has the Books Known as Deuteronomy/Apocrypha]. Kampala: The Bible Society of Uganda. [ Links ]

Byandala, G.I. 1963. The Lusoga Orthography. Iganga.

Chabata, E. 2000. The Shona Corpus and the Problem of Tagging. Lexikos 10: 75-85. [ Links ]

Cohen, D.W. 1986. Towards a Reconstructed Past: Historical Texts from Busoga, Uganda (Union Académique Internationale, Fontes Historiae Africanae Series Varia III). Oxford: Oxford University Press (for the British Academy). [ Links ]

Condon, M.A. 1911. Contribution to the Ethnography of the Basoga-Batamba Uganda Protectorate, Br. E. Africa. Part 2. Anthropos: International Review of Ethnology and Linguistics 6(2): 366-384. [ Links ]

CRC. 1998a. Kintu. Jinja: Cultural Research Center. [ Links ]

CRC. 1998b. Priestly Ordination of Rev. Richard Kayaga Gonza, Rev. Silvester Makwali. Bugembe: Diocese of Jinja. [ Links ]

CRC. 1999a. Ababita Ababiri. Jinja: Cultural Research Centre. [ Links ]

CRC. 1999b. Akatabo Akasooka ak'Enfumo edh'Abasoga. Jinja: Cultural Research Center. [ Links ]

CRC. 1999c. Amagezi Tigamalwayo. Jinja: Cultural Research Center. [ Links ]

CRC. 1999d. Ensambo edh'Abasoga. Jinja: Cultural Research Center. [ Links ]

CRC. 1999e. Mwidhe Tufume. Jinja: Cultural Research Center. [ Links ]

CRC. 1999f. Obufunvu Magezi. Jinja: Cultural Research Centre. [ Links ]

CRC. 1999g. Omuvangano mu Busoga. Jinja: Cultural Research Centre. [ Links ]

CRC. 1999h. Twire ku Butaka. Jinja: Cultural Research Centre. [ Links ]

CRC. 2000a. Enkabi Ekifiini mu Busoga. Jinja: Cultural Research Centre. [ Links ]

CRC. 2000b. Lwaki Abakazi Tibabeeda Mulambo. Jinja: Cultural Research Centre. [ Links ]

CRC. 2002. Ebikoiko eby'Abasoga. Jinja: Cultural Research Centre. [ Links ]

CRC. 2003a. Diocesan Family Day. Iganga: Diocesan Printery. [ Links ]

CRC. 2003b. The Priestly Ordination for Rev. Deacon Mbaziira Henry Jude, Rev. Deacon Musana Paul. Bugembe: Diocesan Printery. [ Links ]

CRC. 2003c. Priestly Ordination of Rev. Serapio Kasuura Wamara Araali. Bugembe: Diocese of Jinja. [ Links ]

CRC. 2004. A Lusoga Grammar (Revision of Korse 1999). Jinja: Cultural Research Centre. [ Links ]

CRC. 2005a. Ebindi kw'Idembe ery'Obw'omuntu mu Nsi Yoonayoona. Kisubi: Marianum Publishing Company. [ Links ]

CRC. 2005b. Priestly Ordination of Deacon Mwangi Simon Gitua, Deacon Mugabe Paschal Atwooki, Deacon Jenga Fred. Jinja: Little Sisters of St. Francis. [ Links ]

CRC. 2008. Enhembo mu Mikolo Emitukuvu Egyo Busaserdooti, Obudyakoni ne Miruka e Kyebando Parish nga 02-08-2008. Kyebando.

CRC. 2009. Ensambo dh'Abasoga (Kisoga Proverbs) (Revision of CRC 1999). Kisubi: Marianum Publishing Company. [ Links ]

CRC. 2010. Installation of Rt. Rev. Bishop Charles Martin Wamika as Bishop of Diocese of Jinja. Kisubi: Marianum Publishing Company. [ Links ]

CRC. 2011. Ensengeka y'Omusomo gw'Ekikulu (Curriculum for Functional Adult Learners in Lusoga). Kisubi: Marianum Publishing Company. [ Links ]

CRC. 2012a. Basoga Catholics in and Around Kampala. Nsambya: Diocese of Jinja. [ Links ]

CRC. 2012b. Missa mu Lusoga Ebiseera eby'Amatuuka n'Amazaalibwa. Jinja: Diocese of Jinja. [ Links ]

CRC. 2012c. Missa mu Lusoga Ebiseera eby'Amazuukira. Jinja: Diocese of Jinja. [ Links ]

CRC. 2012d. Missa mu Lusoga Ebiseera eby'Ekisiibo. Jinja: Diocese of Jinja. [ Links ]

CRC. 2012e. Missa mu Lusoga Ebiseera eby'Omwaka n'Enaku edh'Abatuukirivuu. Jinja: Diocese of Jinja. [ Links ]

CRC. 2012f. Missa mu Lusoga Ensengeka y'Emikolo gya Wiiki Entukuvu. Jinja: Diocese of Jinja. [ Links ]

CRC. 2012g. Thanks Giving Mass. for Rev. Sr. Restetuta Wangoye. Jinja: Diocese of Jinja. [ Links ]

de Schryver, G.-M. 1999. Bantu Lexicography and the Concept of Simultaneous Feedback, Some Preliminary Observations on the Introduction of a New Methodology for the Compilation of Dictionaries with Special Reference to a Bilingual Learner's Dictionary Cilubà-Dutch. Unpublished M.A. dissertation. Ghent: Ghent University. [ Links ]

de Schryver, G.-M. 2002. Web for/as Corpus: A Perspective for the African Languages. Nordic Journal of African Studies 11(2): 266-282. [ Links ]

de Schryver, G.-M. and R. Gauton. 2002. The Zulu Locative Prefix ku- Revisited: A Corpus-based Approach. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 20(4): 201-220. [ Links ]

de Schryver, G.-M. and M. Nabirye. 2010. A Quantitative Analysis of the Morphology, Morpho-phonology and Semantic Import of the Lusoga Noun. Africana Linguistica 16: 97-153. [ Links ]

de Schryver, G.-M. and D.J. Prinsloo. 2000. The Compilation of Electronic Corpora, With Special Reference to the African Languages. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 18(1-4): 89-106. [ Links ]

Devos, M. and G.-M. de Schryver. 2013. From 'habitually going' to 'maybe': Grammaticalization and Lexicalization of an Epistemic Sentence Adverb in Swahili. Anon. (Ed.). 2013. Abstracts of The 21st International Conference on Historical Linguistics: 29. Oslo: University of Oslo. [ Links ]

Devos, M. and G.-M. de Schryver. 2016. From Usually Going to Epistemic Possibility. Origin and Development of an Epistemic Sentence Adverb in Swahili. Anon. (Ed.). 2016. 6th International Conference on Bantu Languages, Workshop on the Expression of Mood and Modality in Bantu Languages: 11. Helsinki: University of Helsinki. [ Links ]

Facebook. 2004-18. Facebook Online Social Media and Social Networking Service. Available online at: https://www.facebook.com.

Gonza, R.K. 2007. Lusoga-English Dictionary and English-Lusoga Dictionary (revision of Korse 2000). Kampala: MK Publishers. [ Links ]

Gulere, C.W. 2007a. Nantamegwa (translation into Lusoga of Antigone, a play by Sophocles from 441 BC). Busembatya: Lusoga Language Academic Board. [ Links ]

Gulere, C.W. 2007b. Omugole (translation into Lusoga of The Bride, a play by Bukenya from 1987). Busembatya: Lusoga Language Academic Board. [ Links ]

Gulere, C.W. 2009. Lusoga-English Dictionary / Eibwanio. Kampala: Fountain Publishers. [ Links ]

Gulere, C.W. 2011a. Abasikawutu. Busembatia: Association of Lusoga Language Educationists, Researchers and Translators. [ Links ]

Gulere, C.W. 2011b. Amagelo mu Nsiko. Busembatia: Association of Lusoga Language Educationists, Researchers and Translators. [ Links ]

Gulere, C.W. 2011c. Ebikete bya Busoga. Busembatia: Association of Lusoga Language Educationists, Researchers and Translators. [ Links ]

Gulere, C.W. 2011d. Ekidhuubo kya Giligoori. Busembatia: Association of Lusoga Language Educationists, Researchers and Translators. [ Links ]

Gulere, C.W. 2011e. Engabo ya Busoga. Busembatia: Association of Lusoga Language Educationists, Researchers and Translators. [ Links ]

Gulere, C.W. 2011f. Lusoga Nguli Namanha. Busembatia: Association of Lusoga Language Educationists, Researchers and Translators. [ Links ]

Gulere, C.W. 2011g. Ndi ni Mukazi Wange. Busembatia: Association of Lusoga Language Educationists, Researchers and Translators. [ Links ]

Gulere, C.W. 2011h. Nsobola Nsobola. Busembatia: Association of Lusoga Language Educationists, Researchers and Translators. [ Links ]

Gulere, C.W. 2011i. Ogusolo ni Ekikaadho. Busembatia: Association of Lusoga Language Educationists, Researchers and Translators. [ Links ]

Gulere, C.W. 2011j. Okusanhusa Tikwesanhusa. Busembatia: Association of Lusoga Language Educationists, Researchers and Translators. [ Links ]

Gulere, C.W. and M. Wambi. 2011. Lusoga Olusonhe. Busembatia: Association of Lusoga Language Educationists, Researchers and Translators. [ Links ]

Guthrie, M. 1948. The Classification of the Bantu Languages (Handbook of African Languages). London: Oxford University Press (for the International African Institute). [ Links ]

Hadebe, S. 2002. The Ndebele Language Corpus: A Review of Some Factors Influencing the Content of the Corpus. Lexikos 12: 159-170. [ Links ]

Hanks, P. 2012. The Corpus Revolution in Lexicography. International Journal of Lexicography 25(4): 398-436. [ Links ]

Hurskainen, A. 2016. Helsinki Corpus of Swahili 2.0 (HCS 2.0) Annotated Version. Available online at: http://urn.fi/urn:nbn:fi:lb-2016011301.

Johnston, H.H. 1902. The Uganda Protectorate. An Attempt to Give Some Description of the Physical Geography, Botany, Zoology, Anthropology, Languages and History of the Territories under British Protection in East Central Africa, between the Congo Free State and the Rift Valley and between the First Degree of South Latitude and the Fifth Degree of North Latitude. London: Hutchinson & Co. [ Links ]

Kajolya, J.B.N. 1990. The Lusoga Orthography (revision of Byandala 1963). Jinja: Lusoga Ecumenical Committee. [ Links ]

Kaluuba, J.P., J. Kivuunike, J.S. Dhizaala and C. Nabirye. 2010. Gw'Olekera Abato: Okusoma kuleeta obusobozi. Jinja: Cultural Research Centre, Marianum Publishing Company and Literacy and Adult Basic Education. [ Links ]

Kaluuba, J.P. and P. Korse. 2010. Kintu (revision of CRC 1998). Jinja: Cultural Research Centre. [ Links ]

Kasozi, J. 2000. Mwidhe Tugye Tusenge. Jinja: Diocese of Jinja. [ Links ]

Kawalya, D. 2017. A Corpus-driven Study of the Expression of Modality in Luganda (Bantu, JE15). Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation. Ghent: Ghent University. [ Links ]

Kawalya, D., G.-M. de Schryver and K. Bostoen. 2018. From Conditionality to Modality in Luganda (Bantu, JE15): A Synchronic and Diachronic Corpus Analysis of the Verbal Prefix -andi-. Journal of Pragmatics 127: 84-106. [ Links ]

Kennedy, G. 1998. An Introduction to Corpus Linguistics (Studies in Language and Linguistics). I lar-low, Essex: Addison Wesley Longman. [ Links ]

Kodh'eyo. 1997-98. Kodh'eyo: Busoga etebenkere (a short-lived newspaper in Lusoga). Kampala: Kodh'eyo Publications. [ Links ]

Korse, P. 1999. A Lusoga Grammar. Jinja: Cultural Research Centre. [ Links ]

Korse, P. 2000. Dictionary Lusoga-English / English-Lusoga. Jinja: Cultural Research Centre. [ Links ]

Kuunya, C. 2011a. Agakuba Omughafu. Kisubi: Marianum Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Kuunya, C. 2011b. Gulaama eyOlusoga [Grammar of Lusoga]. Kisubi: Marianum Publishing Company. [ Links ]

LULANDA and CRC. 2001. Empandiika eyOlulimi Olusoga Enkalamu [Standard Lusoga Orthography]. Jinja: Lusoga Language Development Academy & Cultural Research Centre. [ Links ]

LULANDA and CRC. 2004. Empandiika ey'Olulimi Olusoga Enkalamu [Standard Lusoga Orthography] (2nd edition). Jinja: Lusoga Language Development Academy & Cultural Research Centre. [ Links ]

Lyavala-Lwanga, E.J. 1967. Endheso dh'Abasoga [Proverbs of the Basoga]. Kampala: Milton Obote Foundation. [ Links ]

Lyavala-Lwanga, E.J. 1969. Kiyini Kibi [on language and Lusoga riddles]. Kampala: Milton Obote Foundation. [ Links ]

Maho, J.F. 2009. NUGL Online: The Online version of the New Updated Guthrie List, a Referential Classification of the Bantu Languages. Available online at: http://goto.glocalnet.net/mahopapers/nuglonline.pdf.

Mberamihigo, F. 2014. L'expression de la modalité en kirundi : Exploitation d'un corpus électronique. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation. Brussels; Ghent: Université libre de Bruxelles; Ghent University. [ Links ]

Mberamihigo, F., G.-M. de Schryver and K. Bostoen. 2016. Entre verbe et adverbe : Grammaticalisation et dégrammaticalisation du marqueur épistémique umeengo/umeenga en kirundi (bantou, JD62). Journal of African Languages and Linguistics 37(2): 247-286. [ Links ]

Misago, M.-J. 2018. Les verbes de mouvement et l'expression du lieu en kirundi (bantou, JD62) : Une étude linguistique basée sur un corpus. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation. Ghent: Ghent University. [ Links ]

Mwesigwa, R. s.d. Mu Bigere Bye. Olugero lw'Abasoga ku kugoberera Yesu. Jinja: Church of Christ. [ Links ]

Nabirye, M. 2008. Compilation of the Monolingual Lusoga Dictionary. Unpublished M.A. dissertation. Kampala: Makerere University. [ Links ]

Nabirye, M. 2009. Eiwanika ly'Olusoga. Eiwanika ly'aboogezi b'Olusoga n'abo abenda okwega Olusoga [A Dictionary of Lusoga. For Speakers of Lusoga, and for Those Who Would Like to Learn Lusoga]. Kampala: Menha Publishers. [ Links ]

Nabirye, M. 2016. A Corpus-based Grammar of Lusoga. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation. Ghent: Ghent University. [ Links ]

Nabirye, M. and G.-M. de Schryver. 2011. From Corpus to Dictionary: A Hybrid Prescriptive, Descriptive and Proscriptive Undertaking. Lexikos 21: 120-143. [ Links ]

Nabirye, M., G.-M. de Schryver and J. Verhoeven. 2016. Illustrations of the IPA: Lusoga (Lutenga). Journal of the International Phonetic Association 46(2): 219-228 (+ supplementary audio online). [ Links ]

NCDC. 2006. THEMA News Letter (Issue 2. December 2006). Kampala: National Curriculum Development Centre. [ Links ]

Ndimugezi. 1998-99. Ndimugezi n'omukobere: The Factfinder (a short-lived newspaper, with sections in Lusoga). Jinja: Ndimugezi Publications. [ Links ]

Nshemezimana, E. 2016. Morphosyntaxe et structure informationnelle en kirundi : Focus et stratégies de focalisation. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation. Ghent: Ghent University. [ Links ]

OmniPage. 1995-2018. Optical character recognition (OCR) software now available from Nuance Communications. Available online at: http://www.nuance.com/for-individuals/by-product/omnipage/.

Prinsloo, D.J. 2015. Corpus-based Lexicography for Lesser-resourced Languages - Maximizing the Limited Corpus. Lexikos 25: 285-300. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, D.J. and G.-M. de Schryver. 2001. Monitoring the Stability of a Growing Organic Corpus, with Special Reference to Sepedi and Xitsonga. Dictionaries: Journal of The Dictionary Society of North America 22: 85-129. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, D.J. and G.-M. de Schryver. 2005. Managing Eleven Parallel Corpora and the Extraction of Data in All Official South African Languages. Daelemans, W., T. du Plessis, C. Snyman and L. Teck (Eds). 2005. Multilingualism and Electronic Language Management. Proceedings of the 4th International M1DP Colloquium, 22-23 September 2003, Bloemfontein, South Africa (Studies in Language Policy in South Africa 4): 100-122. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

Rundell, M. and P. Stock. 1992. The Corpus Revolution 3. A Consideration of the Prospects and Potential of Corpus-and-concordance Lexicography (third article of three). English Today, The 1nternational Review of the English Language 8(4): 45-51. [ Links ]

Scott, M. 1996-2018. WordSmith Tools. Available online at: http://www.lexically.net/wordsmith/.

Sene-Mongaba, B. 2013. Le lingála dans l'enseignement des sciences dans les écoles de Kinshasa : Une approche socioterminologique. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation. Ghent: Ghent University. [ Links ]

Sene-Mongaba, B. 2015. The Making of Lingala Corpus: An Under-resourced Language and the Internet. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 198: 442-450. [ Links ]

UBOS. 2006. The 2002 Uganda Population and Housing Census, Analytical Report, Population Composition. Kampala: Uganda Bureau of Statistics. [ Links ]

UBOS. 2016. The National Population and Housing Census 2014 - Main Report. Kampala: Uganda Bureau of Statistics. [ Links ]

Wabugoyera, J.B. Kasubi, J.P. Kaluuba, Mukama, M. Maganda and M. Maganda. 2008. Ekimuliikirira, August-October 2008. Jinja: Diocese of Jinja. [ Links ]

Wambi, M., R. Naigaga and CRC. 2005. 1dha Tusome [Come and We Read]. Jinja: Lusoga Language Authority. [ Links ]

YouTube. 2005-18. YouTube video-sharing website. Available online at: https://www.youtube.com.

1. In our work Lusoga, as in all subsequent mentions of 'Lusoga corpus', narrowly refers to the Lutenga variety only (Nabirye et al. 2016).

2. At the CRC library in Jinja, a substantial amount of grey literature may also be found, either written by the CRC staff itself, or facilitated by them. These works are mostly for internal use, of a religious nature and typically do not have a stated publisher, but may be 'assigned' to the CRC (e.g., CRC 1998b, Kasozi 2000, CRC 2003a, b, c, 2005b, 2008, Wabugoyera et al. 2008, CRC 2010, 2012a, b, c, d, e, f, g). Other religious works often do not have publication years, such as Mwesigwa (s.d.), except for those published by The Bible Society of Uganda, for which, see Endnote 8. Lately, the CRC has begun rejacketing earlier works, including CRC (2009) and Kaluuba and Korse (2010). The CRC also played a pioneering role in producing the first grammars for Lusoga (Korse 1999, CRC 2004, Wambi et al. 2005, Kuunya 2011b), the first bilingual Lusoga-English dictionaries (Korse 2000, Gonza 2007), new orthographies (LULANDA and CRC 2001, 2004), as well as readers (e.g., Gulere and Wambi 2011).

3. Gulere also compiled a bilingual Lusoga-English dictionary (Gulere 2009).

4. At BantUGent a diachronic corpus for Swahili with a time-depth of up to two centuries is under construction. Research articles have not yet been published, however, although preliminary results have been presented at conferences (Devos and de Schryver 2013, 2016).

5. While not magic, Rundell and Stock (1992: 46) refer to this part of a corpus as the 'Holy Grail': 'Truly spontaneous speech, however - the everyday conversation of ordinary members of the public - has so far been available only in very small quantities and for lexicographers this remains the "Holy Grail". '

6. In earlier descriptions of corpus building for the Bantu languages, some attention was paid to the type of OCR errors one needs to attend to (de Schryver 1999: 116). Today's OCR software is however so performant that all one needs to remember is that the letter combination read as 'rn' should often be corrected to the single letter 'm'.

7. Observe that material for the 1980s was found after all, in an academic publication (Cohen 1986), following a memorable search (Nabirye 2016: 25-27). Although eventually published in 1986, this edited material is based on recordings made two decades earlier, in 1966-1967.

8. A late entrant - in the sense that it came too late to be added to the 1.7m Lusoga corpus (apart from the fact that it may not have been desirable for reasons of representativeness and balance) - is the full Bible in Lusoga, which became available in 2014 (BSU 2014). As is normally the case with biblical works, the full Bible (BSU 2014) incorporates the New Testament (BSU 1998) - published earlier and included in the 1.7m Lusoga corpus. The New Testament itself incorporated the even earlier Gospel of Mark (BSU 1996), which in turn incorporated the still earlier Chapters 4 and 5 of the same gospel (BSU 1994). After the New Testament was released, at least one other edition appeared, with the addition of the Psalms from the Old Testament (BSU 2011).

9. The topic Language mainly includes material about teaching the language of Lusoga and instructional material for Lusoga (written in Lusoga), as well as website texts and journal abstracts on Lusoga (written in Lusoga).

10. See Nabirye et al. (2016) for more on these phonetic issues.

11. Or, as Kennedy (1998: 82) writes: 'A transcription is an imperfect written approximation of a speech event which exists initially as a dance of air molecules. The level of delicacy or amount of detail in a transcription is [... ] related to the use to which the transcription will be put'.

12. As defined by Scott (1996-2018) 'the standardised type/token ratio (STTR) is computed every n words as Wordlist goes through each text file. By default, n = 1,000. In other words the ratio is calculated for the first 1,000 running words, then calculated afresh for the next 1,000, and so on to the end of your text or corpus. A running average is computed, which means that you get an average type/token ratio based on consecutive 1,000-word chunks of text. (Texts with less than 1,000 words (or whatever n is set to) will get a standardised type/token ratio of 0.)'.