Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Lexikos

versão On-line ISSN 2224-0039

versão impressa ISSN 1684-4904

Lexikos vol.27 Stellenbosch 2017

ARTICLES

The Dictionary in Examinations at a South African University: A Linguistic or a Pedagogic intervention?*

Die woordeboek in eksamens by 'n Suid-Afrikaanse universiteit: 'n taalkundige of 'n opvoedkundige ingryping?

Dion Nkomo

School of Languages, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa (d.nkomo@ru.ac.za)

ABSTRACT

This paper interrogates students' use of dictionaries for examination purposes at Rhodes University in South Africa. The practice, which is provided for by the university's language policy, is widely seen as a linguistic intervention particularly aimed at assisting English additional language students, the majority of whom speak African languages, with purely linguistic information. Such a view is misconceived as it ignores the fact that the practice predates the present institutional language policy which was adopted in 2006. Although it was difficult to establish the real motivation prior to the language policy, this study indicates that both English mother-tongue and English additional language students use the dictionary in examinations for assistance that may be considered to be broadly pedagogic rather than purely linguistic. This then invites academics to reconsider the manner in which they teach and assess, cognisant of the pedagogic value of the dictionary which transcends linguistic assistance.

Keywords: dictionary use, dictionary assistance, pedagogical lexicography, open-book examinations, linguistic intervention, pedagogic intervention

OPSOMMING

Hierdie artikel ondersoek studente se gebruik van woordeboeke vir eksamendoeleindes by die Rhodes Universiteit in Suid-Afrika. Die praktyk, waarvoor daar voorsiening gemaak word in die universiteit se taalbeleid, word wyd beskou as 'n taalkundige ingryping met suiwer taalkundige inligting wat in die besonder daarop toegespits is om Engels Addisionele Taal-studente te help, waarvan die meerderheid Afrikatale praat. So 'n siening is 'n mistasting, aangesien dit die feit ignoreer dat die praktyk van voor die huidige institusionele taalbeleid, wat in 2006 aanvaar is, dateer. Alhoewel dit moeilik was om die werklike motivering daarvoor vóór die huidige taalbeleid vas te stel, toon hierdie navorsing dat sowel Engels Moedertaal- as Engels Addisionele Taal-studente die woordeboek tydens eksamens gebruik vir hulp wat oor die algemeen beskou kan word as opvoedkundig eerder as suiwer taalkundig. Dit dring akademici om die manier waarop hulle onderrig gee en assessering doen, te heroorweeg, en kennis te neem van die opvoedkundige waarde van die woordeboek, wat taalkundige hulp oortref.

Sleutelwoorde: woordeboekgebruik, woordeboekhulp, opvoedkundige leksikografie, oopboekeksamens, taalkundige ingryping, opvoedkundige ingryping

1. Introduction

This paper interrogates students' use of dictionaries for examination purposes at Rhodes University in South Africa. The practice is provided for by the language policy of the university while the institution's assessment policy is silent about it. The language policy requires academic departments to "provide access to a wider range of dictionaries in examinations" where appropriate (Rhodes University Language Policy 2006; 2014). Accordingly, the African Language Studies and the German Studies sections of the School of Languages and Literatures recommend the use of certain dictionaries in translation and language learning studies examinations. Such dictionary use during examinations is common in South Africa and abroad (Atkins 1998; Barnes et al. 1999; Bensous-san 1983; Bishop 2000; Nesi and Haill 2002). However, it is the use of monolingual English dictionaries during examinations, almost across the board, that concerns this paper. As far as could be established, this practice is rare although it would not be surprising to see it spreading with the on-going efforts of implementing university language policies in South Africa. Besides implementing multilingualism, the language policies encapsulate interventions that are hoped to help students with challenges posed by the language of teaching and learning. it is important that such interventions are investigated in terms of their efficacy.

The rationale for dictionary use in examinations at Rhodes University is not explicitly articulated but rather inferred only in terms of the language policy as an intervention that seeks to eliminate linguistic barriers for English additional language students, the majority of whom speak African languages. This suggests that the dictionaries, which are discussed later in the article, are consulted for purely linguistic problems during examinations, especially by English additional language students. For this reason, the practice is supported by academics who regard it as integral in facilitating students' success irrespective of linguistic backgrounds. Unfortunately, such claims are not based on concrete knowledge of what happens during examinations in relation to dictionary use. Even more remarkable, the senior citizens of the institution only recall that the practice pre-dates the language policy which came into effect in 2006. institutional language policies became a legislative imperative following the recommendation of the Language Policy for Higher Education in 2002 in order to outline how universities would, among other issues, address the language of teaching and the role of indigenous African languages as part of transformation. The argument for dictionary use during examinations as a transformative intervention that facilitates epistemic access for English additional language students therefore becomes an unsustainable case of convenience where the language policy merely co-opted a practice whose original motivation might have been different from the current discourses of language in higher education.

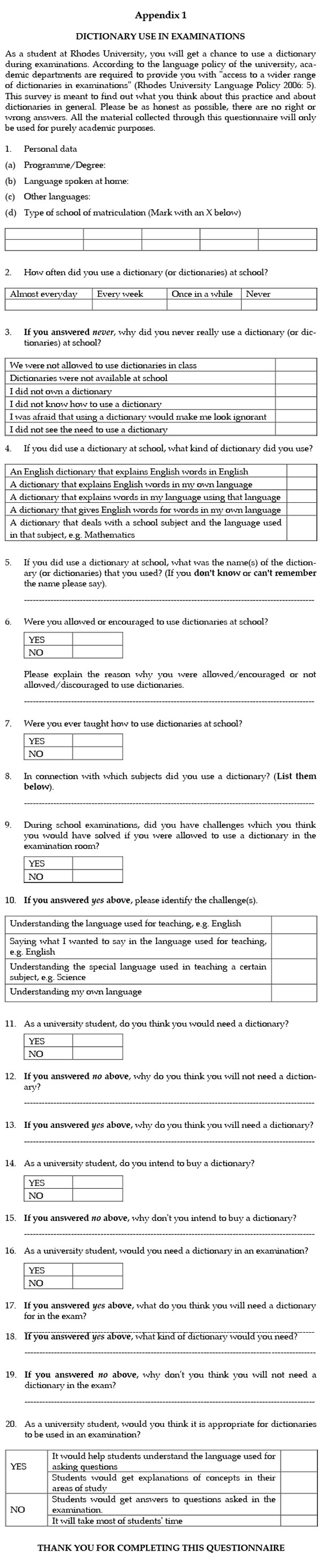

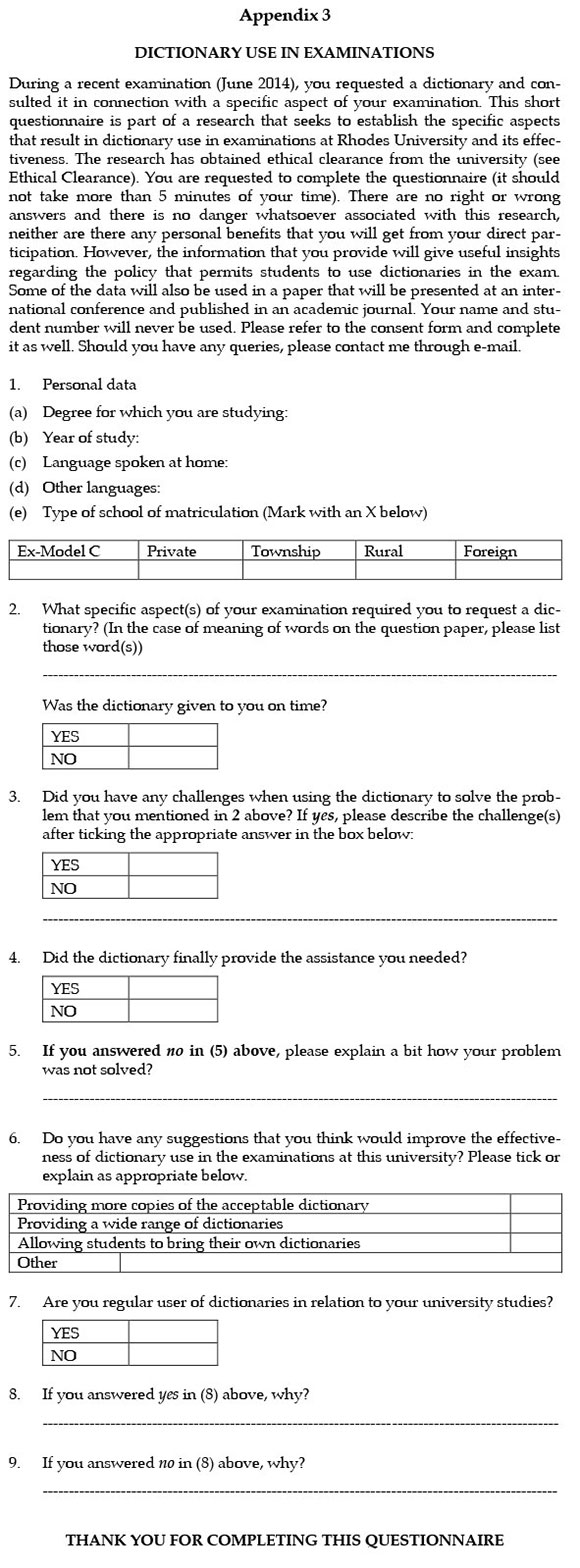

This paper is based on data that was collected through three questionnaire surveys, observations and interviews. The first questionnaire (Appendix 1) was administered among first-year students during registration in February 2014 to get new students' views regarding a practice that would characterise their examinations. The second questionnaire (Appendix 2) was completed by returning students to establish the extent to which they have been using the dictionary in their previous examinations. The final questionnaire (Appendix 3) was completed during the June 2014 examinations by students who were observed using the dictionary in particular examinations mainly to establish specific issues that instigated dictionary consultation. Observations were conducted over two weeks during the June 2014 examinations to get a sense of the prevalence and frequency of dictionary use, as well as the information needed and obtained by students in the process. Interviews were conducted with the key institutional stakeholders, including the Deputy Vice-Chancellor for Teaching and Learning, University Registrar, the Dean of Students, the Chairperson of the institutional Language Committee, academics and students in order to solicit perceptions towards the practice. Appropriate ethical procedures were followed, including seeking institutional permission from the Registrar, the Examinations Officer and applying for ethical clearance from the Rhodes University Ethical Standards Committee. Students who participated in the research were also fully informed about it and advised about the voluntary nature of their participation.

Using the collected data, this article challenges the purported language-oriented motivation for dictionary use in examinations and projects a pedagogic argument as an alternative. The data displays various perceptions regarding dictionary use at Rhodes University, both in general and specifically in connection with examinations, and presents an empirical picture of what actually happens with the dictionary in examination venues. For this purpose, the notion of open-book examinations, complemented by insights from pedagogical lexicography, informs the discussion. In the context of rapidly developing educational technologies, including computer-based assessments, issues of open-book examinations and access to electronic dictionaries and other tools installed in such technologies during examinations become relevant. The adoption of take-home examinations as a strategy of saving the academic year following student protests in 2016 by Rhodes University and other South African institutions has probably catalysed the implementation of open-book examinations, which will have implications for dictionary use during examinations.

2. Pedagogical lexicography

Although lexicography was originally regarded as a branch of linguistics (Zgusta 1971), and dictionaries as largely linguistic instruments (Atkins and Rundel 2008; Béjoint 2010), McArthur (1986) aptly regards them as containers of knowledge, with other modern scholars recognising that such knowledge transcends language (Wiegand 1984; Tarp 2008). The branch of lexicography that provides relevant theoretical lenses for understanding the needs of students leading to dictionary consultation in examinations and the assistance obtained from dictionaries would be pedagogical lexicography, also called learner's lexicography (Cowie 2002; Tarp 2008). It developed in connection with the teaching of English as a foreign language in Asia in the 1970s through groundbreaking lexicographic approaches of Albert Snell-Hornby, Harrold Palmer and Michael West, who were experienced English teachers. The term learner's dictionary has been extensively used as part of titles of dictionaries produced for English additional language learners. However, its interpretation has been restricted to regard a learner only as somebody who is learning an additional language, as opposed to a native speaker, who may also enrol in a programme to learn his/her native language (Gouws 2010; Tarp and Gouws 2012). Such an interpretation concurs with the generally problematic perception in this study that the dictionary in examinations supports English additional language students. In a sense that resonates with the South African education system, the learner in pedagogical lexicography refers to any person who is learning any language, native or additional, or any academic subject (Gouws 2010; Tarp and Gouws 2012). This means that users who consult dictionaries in relation to their learning, qualify to be learners, as the dictionary offers them assistance in connection with their education. In this paper, principles drawn from pedagogical lexicography are used to characterise the needs of students who consult dictionaries during examinations and the type of information provided by the dictionaries to satisfy those needs.

3. Open-book examinations

The use of dictionaries under examination conditions evokes an old debate on open-book examinations. Open-book examinations entail the use of different pedagogic aids such as graphics calculators and computer algebra systems in mathematics, atlases in geography, set texts in literature or even dictionaries in second language acquisition or translation studies, textbooks and notes in any subject (Stalnaker and Stalnaker 1934; Boniface 1985; Barnes et al. 1999; Bensoussan 1983; Bishop 2000; Graham et al. 2003; Kemp et al. 1996; Monaghan 2000). The consensus seems to be that open-book examinations are not inherently inappropriate. Graham et al. (2003: 320) reckon that such examinations offer better opportunities of aligning assessment with curriculum objectives, teaching practices and even real life or work situations compared to some traditional closed-book examinations for which students have to prepare by cramming concepts that they may never need in their future professions. For example, the use of graphics calculators and computer algebraic systems in mathematics examinations has been considered helpful in as far as candidates have been taught how to use these tools appropriately for specific tasks in the course (Stalnaker and Stalnaker 1934: 117). The use of learning aids becomes part of the skills that are the focus of assessment alongside others in the course. The same could be said of dictionary use in the context of second language learning or translation studies examinations where looking up the meaning of words can be helpful for the candidate who would be able to choose appropriate translation equivalents, comprehend definitions and then apply them appropriately in the relevant context. Dictionary using skills become important for the translator's future practice. In this paper, the notion of open-book examinations is used in relation to the purposes for which dictionaries are used in examinations vis-à-vis how the questions have been formulated, and whether such use is consistent with the hypothesis that the dictionary is permitted only as a language intervention tool.

4. Perceptions of academics

Interviews with university personnel revealed perceptions ranging from support to opposition and indifference towards dictionary use in examinations. The contradictory perceptions indicate different attitudes towards the language question in higher education, as it is assumed to be the major issue addressed by the practice, as well as the pedagogic role of the dictionary in general. Some of the perceptions are unfortunately misguided. Academics who support the dictionary in examinations, as already indicated, evoke the institutional language policy and would recommend any intervention meant to eradicate linguistic barriers to access by and success for English additional language students. They particularly advance that mother-tongue English speakers enjoy an advantage over their non-mother tongue peers who have to switch from other languages whenever they move in and out of academic spaces. The dictionary is thus seen as a transformative intervention supporting English additional language students, just like opening spaces for indigenous languages in South African higher education and education broadly to level the field for students with diverse linguistic, cultural and educational backgrounds. While sensitivity towards the language issue is welcome, this argument falls short as it disregards the long history of the practice and takes for granted what students do with the dictionary and what dictionaries offer, especially considering the fact that the dictionaries used employ English as the language of explicating the academic language with which English language additional students are struggling.

There are basically two arguments advanced by academics against the dictionary in examinations. One position simply opposes the language-policy oriented argument, positing that the language-problem in South African higher education is misconstrued if not overstated (Boughey 2002), given that academic language is nobody's mother-tongue. From this position, language-based problems should not be an excuse for students' academic struggles to the extent of needing the dictionary as an intervention in examinations. This argument is hugely flawed, if not insensitive; it disregards the notion of pedagogy of place, thereby decontextualising academic expectations of university students. It constructs universities as similar across space and time, while delinking the linguistic identities of students from the curriculum. Specifically, the argument fails to recognise that mother-tongue speakers of the language of teaching and learning already have stronger linguistic and cultural foundations for the development of academic language than non-mother tongue speakers. Although there are some irregularities regarding dictionary use in examinations, as the study shows, the practice may not simply be challenged by merely dismissing the language problem or saying 'not at university' without a pedagogic qualification of why not at university and particularly in examinations.

The limitation of the foregoing argument against dictionary use in university examinations leads to the second one, which appears to be a matter of greater consideration. This argument advances that dictionary use for examination purposes may not be embraced or dismissed as a question of right or wrong. Instead, the role of the dictionary must be considered in relation to the broader curriculum aims and in terms of its implications for assessment. Such discourse can be illustrated by the views of a Pharmacy lecturer who considers dictionary use for pharmacy examinations problematic in that the dictionary may explain not only the language but also the concepts that students need to learn and master during the course in order to apply them in future practice. The orientation is that discipline-specific terminology, which is also assessed in various subjects, is an integral part of the pharmaceutical knowledge. Thus, according to this academic, the technical acumen of a student who needs a dictionary in the exam would be suspect, i.e. the student may not have fully achieved the learning outcomes of the course. This view is shared by the majority of lecturers who are conscious of what they teach and how they assess. Another example is from the Law Faculty where the following instruction was given in a Legal Pluralism examination paper:

The Oxford Concise English Dictionary may be used during this examination for the purpose of looking up words that are not legal terms relevant to the course content. Invigilators may ask you which word you wish to look up to determine whether the use of the dictionary is appropriate.

This statement indicates that dictionary use may be considered appropriate or inappropriate, depending on what students look up and in relation to course content.

However, there are some academics who prohibit the dictionary in their examinations because they consider it unhelpful and a time-wasting exercise. The view is that dictionaries provide limited and unreliable definitions when it comes to discipline-specific language and students who consult a dictionary for this purpose would be misguided. A Journalism and Media Ethics lecturer prohibits dictionary use in his examinations mainly to protect his students from this danger. Unfortunately, this view is based on limited knowledge about dictionaries as knowledge tools, particularly around issues of dictionary typology and the kinds of assistance that users may get from different types of dictionaries. While some dictionaries may have limitations, as indicated by Nielsen (2015), such limitations may not be generalised to the extent of influencing a policy on dictionary use.

Finally, it is significant to note that some academics who are not against the use of dictionaries in examinations at Rhodes University do not clearly or strongly support the practice. The practice is now part of a tradition that new academics merely embrace without giving it sufficient thought or taking it into cognisance when setting examinations. Their attitude towards the practice is at best that of indifference and prevails even among the senior management of the university. Some thought-provoking questions during separate interviews with the Registrar and the Dean of Students saw a sudden change in the practice even before the findings of this research were presented. The Examinations Office, which supplies the dictionaries, suddenly called on academics to include a compulsory instruction regarding the permissibility of dictionary use on their examination papers since June 2014. The sudden change indicates that there was hitherto no well-conceived institutional position regarding dictionary use in examinations. Nevertheless, it has offered academics an opportunity to think about the dictionary and ways of formulating assessment tasks which may have implications for dictionary use in examinations. Whether such an opportunity is optimised is a question for the future.

5. Perceptions of students

The data obtained through Questionnaires 1 and 2 indicate that students generally support dictionary use under examination conditions. 69 of the 109 first-year students who completed the questionnaire thought they would need the dictionary during university examinations, a privilege they have never had at school level. This is most probably because of fear of the unknown as students expect a steep increase in academic expectations from high school to university. One student actually remarked, "I have never written an exam of university level and would not know what to expect" (sic). Such students seem to expect language use at university to increase in complexity together with the level of depth in academic engagement. Interestingly, 7 of the 69 first-year students who indicated that they would take advantage of dictionary use in examinations consider the practice as cheating which may "give students answers". Such sentiments also emerge from Questionnaire 2 data. 48 out of 95 students considered dictionary use as an appropriate intervention in examinations.

However, only 26 of the 95 students indicated that they had resorted to this intervention, with 2 of them regarding it as bordering on cheating. The perception that dictionary use in examinations borders on cheating also surfaced in some responses of first-year students who anticipated not to need the dictionary, as well as the returning students who indicated that they have never experienced the need in their previous examinations. Some students made the following remarks:

- Examination is preparation. Dictionaries mean less prep is required.

- People should learn all the necessary language when studying for the exam.

- Students should understand all concepts before the exam.

- Learners should be able to understand questions without it. If they don't, either work was not studied ...

- I used it to find definitions I should have learnt. They were provided in class.

These sentiments suggest that dictionary use in examinations supports or rewards lack of effort on the part of students and generally concur with the arguments of the majority of academics typified by the Pharmacy lecturer and Law Faculty referred to above. However, such sentiments did not feature in Questionnaire 3 data, perhaps given that students completed the questionnaire immediately after using the dictionary in their examinations. The chances of these students being critical of the practice immediately after benefitting from it would be low.

Comprehending questions seems to be the most salient reason why new students anticipated the need for the dictionary in their examinations. This is captured below:

- ... so that I could give explicit answers and be sure that I understood the question.

- So that I may look up words that I do not fully understand and I may answer confidently.

- Using a dictionary would ensure that I am fully able to understand all the questions.

- To correctly answer questions.

Within the function theory of lexicography, which is based on a simple communication model, comprehension is an important aspect of the text reception function of dictionaries in communicative situations (Bergenholtz and Tarp 2003; Tarp 2008). According to this theory, comprehension problems arise when one is not familiar with the language that is used or some of its aspects. A combined total of 19 students who support dictionary use in examinations indicate that the dictionary would provide assistance in relation to understanding English, the language of teaching at university, or understanding the specialised languages used in the different discipline-specific subjects. A link was made by some students between comprehension challenges and the proficiency of English additional language students, as can be seen below:

- ... language of study is English and not all students necessarily understand it and therefore need a dictionary.

- ... if English is not their home language.

- ... there are a lot of English words that will be new to me as I am not used to using English as my medium of instruction and communication.

- Because I want to make sure of the words that I will use or read. ... English is not my mother tongue.

- Afrikaans was my home language (at school) so I will need a dictionary for some explanations.

Such a link may not be dismissed. English mother-tongue speakers would have a broader vocabulary base compared to their non-mother tongue counterparts. This provides a stronger foundation for building the academic language and has implications for their communicative competence, including comprehension which is fundamental to how well students respond to examination questions and tasks (Rundell 1999: 35). However, although comprehension is largely a communicative process, it may also be affected by cognitive factors that are beyond issues of language. Language per se may never be the sole factor in the examination. One also needs to be cognisant of what the language is used in connection with, inasmuch as examination preparation and the pedagogies that precede it may not be limited to linguistic processes. Therefore, a dictionary that addresses only linguistic problems would be appropriate for use in examinations if language was the real and only issue that the intervention sought to deal with. Yet it remains unclear yet whether the problems are only linguistic and also whether the dictionary offers purely linguistic assistance in a manner that does not affect assessment. When asked why they would need a dictionary in their examinations, some first-year students made allusions to pedagogical issues that make the dictionary handy:

- Exams can be so overwhelming that you forget even the minor words used in questions. So having a dictionary will make me feel at ease.

- Exam questions are often vague and sometimes lecturers include words that may not be fully understood by myself or other students .

- Learners should be able to understand questions without it. If they don't, either work was not studied or lecturer did not set appropriate papers.

From the above responses regarding circumstances that lead to students using the dictionary, issues of anxiety, poor examination preparation by students as well as poor formulation of examination questions and tasks by lecturers come to the fore (see also Stalnaker and Stalnaker 1934: 119). This clearly suggests that the dictionary serves as more than a linguistic intervention. Whether the intervention offers sufficient assistance and whether such assistance is indeed necessary is another question. One student who considers dictionary use to provide room for cheating indicated that (s)he would use the dictionary for the convenience of having it: "If it is available why not?"

6. Dictionary users, their linguistic backgrounds and subjects of study

81 post-examination questionnaires were completed by 79 candidates who used the dictionary during the June 2014 examinations. Two candidates notably completed the questionnaire twice in connection with separate examinations. The 79 candidates are those who wrote their examinations at the observed venues (exams were written concurrently at several venues and not all of them could be observed) and consented to participate in the research as others had no energy, interest nor time to complete the questionnaire after energy-sapping examinations. This means that dictionary use during examinations at Rhodes University was more prevalent than reported here.

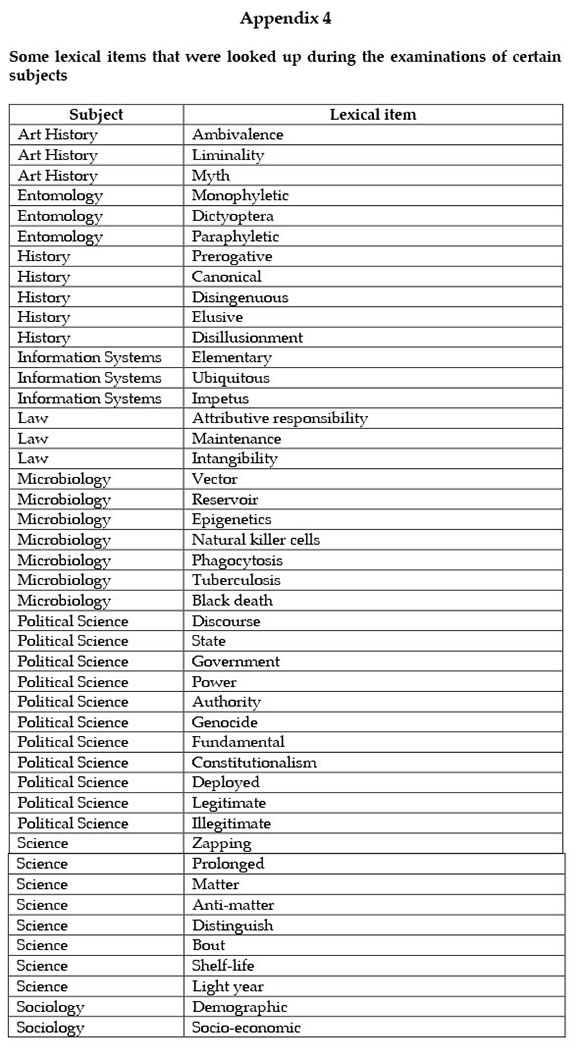

Observational and Questionnaire 3 data indicate that the dictionary was used in connection with various subjects that include Art History, Economics, Entomology, History, Information Systems, Law, Microbiology and Political Science during the June 2014 examinations. The subjects are offered in four of the five faculties whose examinations were observed, with the Faculty of Pharmacy having no dictionary usage instance. The non-use of the dictionary for Pharmacy examinations may be attributed to the fact that students had no choice as their examinations clearly prohibited dictionary use through the compulsory instruction that had just come into effect. On the other hand, the use of the dictionary by Law students is an interesting case where candidates either did not read the instruction regarding dictionary use or deliberately violated it. As may be seen from Appendix 4, legal terms and expressions were looked up while the instruction only permits students to look up non-legal words. This suggests that invigilators did not fulfil the responsibility of checking what students would look up, a difficult task indeed.

When looking at the users of dictionaries during the June 2014 examinations, observational data presented speakers of indigenous African languages as a slight majority, true to the anticipation of the language-policy oriented rationale of the intervention. However, mother-tongue English speakers also used the dictionary. A third-year English monolingual student writing an Entomology examination who requested the dictionary countless times is a good example. This suggests that the problems prompting dictionary consultation may not be exclusively linguistic. To some extent, they may have to do with the preparedness of the candidate for examinations, which includes how students have been taught and prepared for their examinations. For example, while 26 of the 51 candidates who wrote the Introduction to Science Concepts & Methods Paper 1 examination used the dictionary (some of them repeatedly), they are on the Extended Studies Programme (ESP), which offers an alternative access route to higher education for students with lower than the required entry level points. Most of them speak isiXhosa, the most dominant language in the Eastern Cape, the province where Rhodes University is located. Generally, ESP students have low levels of preparedness for university education, having attended under-resourced schools. The programme employs different intervention strategies to see these students through the course before joining mainstream programmes. When it comes to examinations, the dictionary seems to become very handy for ESP students.

What is disappointing from a lexicographic point of view is that a significant number (34 out of 79) examination candidates who used the dictionary responded negatively to the question which sought to establish whether or not they were generally regular dictionary users in their academic lives. Most of them indicated that they did not experience language problems that require regular dictionary support as their vocabulary was good enough. However, triangulating this explanation with what some students had looked up, e.g. prolonged, impetus, government, power, etc., suggests otherwise. It highlights a generally poor dictionary culture among South African students (Gouws 2013; Nkomo 2015; 2016; Taljard et al. 2011) who overstate their knowledge while underestimating the potential benefits of dictionary use. There are others who benefit from a lexicographic intervention such as internet dictionaries but do not classify them as dictionaries because for them only printed dictionaries qualify to be called thus. Responses such as "I use the internet" were unsurprisingly prominent.

Although the number (40) of candidates who claimed to be regular dictionary users is higher than those who claimed not to be, most of them are ESP students. One of them indicated that they are required to buy two dictionaries, one general-purpose English dictionary and a science dictionary for the Introduction to Scientific Concepts and Methods module. One ESP lecturer who supports dictionary use in examinations confirmed that she encourages students to buy and use dictionaries in their studies in connection with language problems. Most of the ESP students indicated that they were regular dictionary users in their studies because they struggled with English. Some even emphasised the value of dictionaries in their disciplines such that dictionaries are an essential part of their educational toolkits.

7. Specific needs of examination candidates from the dictionary

The need for meaning emerged most prominently during examinations that were observed, as is the case of dictionary use in general (Atkins 1998; Chen 2012; Dziemianko 2010; Nesi and Haill 2002; Rundell 1999; Scholfield 1999). 74 out of a total of 79 students who completed Questionnaire 3 consulted the dictionary for meaning information. The only other information type that was reportedly sought was spelling, albeit by a few candidates. Unfortunately, it could not be established whether spelling is such an emphasised skill in their studies that would also be marked in examinations.

The potential need for meaning was also high among new students who completed Questionnaire 1. Typical answers in response to why the respondents thought they would need a dictionary in examinations included the following:

- (To) understand certain terms

- Explaining difficult jargon

- Technical jargon might prove difficult

- So that we can have a better way of understanding concepts

- To know the real definition of the terms, especially in Biology/Chemistry

The same applies to returning students who responded to Question 12 of Questionnaire 2. They had to choose at least one of the five options, namely, understanding English, expressing oneself in English, understanding discipline-specific language, understanding one's own language and other reasons that had to be specified. From the 26 dictionary users in previous examinations, the need to understand the language of teaching a certain subject (terminology and register) featured most prominently (10 times), followed by the need to understand the language of teaching (English) generally. Again, it is the need for meaning information that is generally highlighted.

It is important to determine the nature of linguistic forms for which examination candidates need meaning information. Are the problems linguistic or pedagogic? Appendix 4 lists the items whose meaning was sought during the June examinations. Based on the context of usage in the respective examinations, only a few of those items, e.g. socio-economic (Sociology), impetus (Information Systems), prolonged (Introduction to Science Concepts and Methods), disillusionment (History), disingenuous (History), legitimate and illegitimate (History) may be considered to be general words without specialised disciplinary designations. There are others which were isolated from expressions in which they may have developed special meanings and looked up as separate words, e.g. fundamental instead of fundamental contradiction (Political Philosophy), liminality instead of cultural liminality (Art History and Visual Culture), ubiquitous instead of ubiquitous intelligence (Information Systems), among others. However, the majority of lexical items that were looked up appear to have discipline-specific designations and meanings; they fall within the terminological scope or registers of particular disciplines, as indicated by the context of usage of underlined items in the examination questions presented below:

- Which of the following does not apply to data?

(a) Is a fact of any kind

(b) Raw material

(c) Elementary

(d) Intangible (Information Systems 201).

- Part of the library's long term-vision is to strive towards securing unrestricted access to research outputs (i.e. supporting the Open Access movement). This is an example of:

(a) Democratization of knowledge

(b) Ubiquitous intelligence

(c) Secularization of knowledge

(d) Commoditization of knowledge (Information Systems 201).

- Discuss how Dictyoptera protect their eggs, and the defensive adaptations of Phasmida (Entomology 202 - Theory Paper 1).

- Define monophyletic and paraphyletic. Discuss the implication for understanding biodiversity, and give examples of their influence on modern classification of insect orders (Entomology 202 - Theory Paper 1 ).

- Discuss the concepts of ambivalence and cultural liminality found at the core of mas and carnival performances... (Art History and Visual Culture 1).

- Write an essay on constitutionalism as theory of limitation. Start by defining a) the state, b) government and authority (Puzzles in Contemporary Political Philosophy and Introduction to Political Theory, Paper 1 ).

- The Rwanda genocide can be understood as a massive failure to negotiate the fundamental contradiction. Write an essay in which you discuss the role of Hamitic hypothesis in this failure (Puzzles in Contemporary Political Philosophy and Introduction to Political Theory, Paper 1 ).

- Distinguish between matter and anti-matter, giving an example of each (Introduction to Science Concepts and Methods, Paper 1 ).

- What does the word zapping mean? (Introduction to Science Concepts and Methods, Paper 1 ).

The above examples illustrate that the lexical items that were looked up constitute vital aspects of the knowledge that was being assessed. As articulated in the TermNet motto that "There is no knowledge without terminology", disciplinary knowledge and terminology are inextricably linked. This suggests that the items that were looked up represent concepts that were studied in class, as indicated by some students. In that case, dictionary use in the respective examinations was not only a question of students having language problems but also problems related to what they have been taught and probably how they have (not) engaged with it beyond the lectures. It is in such cases where dictionary use may unduly benefit students, although the problem may be rooted in the manner of formulating the questions as indicated by Stalnaker and Stalnaker (1934: 119).

8. Dictionary assistance for examination candidates

In lexicography, a distinction has been made between general-purpose dictionaries and specialised dictionaries (Béjoint 2010; Gouws and Prinsloo 2005). The former deal with a particular language in a holistic and general way, whereas the latter deal with specialised languages and knowledge constituting specific disciplines. However, modern dictionaries may be considered to be typological hybrids as their efforts to address different user needs result in them combining features drawn from different types of dictionaries (Béjoint 2010). Generalpurpose dictionaries also include lexical items traditionally belonging to specialised dictionaries treating vocabulary of different specialised disciplines and subjects. Furthermore, when such lexical items are included, enough indications are given regarding the disciplinary associations of such vocabulary, including specialised definitions. However, publications that have analysed definitions of specialised and scientific terms in general dictionaries indicate that the definitions are not always helpful as they are sometimes littered with mistakes or completely false (cf. Nielsen 2015).

Different dictionaries, namely The Concise Oxford Dictionary (COD), The South African Concise Oxford Dictionary (SACOD) and its second edition entitled The Oxford South African Concise Dictionary (SACOD2) are used at Rhodes University during examinations. In terms of typology, they all fall under the category of general-purpose dictionaries. However, the university seems to have been under the impression that one dictionary was being used. Since June 2014, the instructions on examination question papers have specifically referred to the COD. This dictionary was originally published in 1911 based on the Oxford English Dictionary (OED). The idea was to produce a medium-sized dictionary offering a concise description of English out of the comprehensive OED. SACOD was adapted from the 10th edition of COD for South African users and therefore contains words and phrases considered to be mainly South African while its second edition is an update which captures more recent developments. The SACOD2 contains "a large number of scientific and technical terms, legal phrases and other specialist terms, especially those likely to be encountered by the general public and students' (Kavanagh 2002: vii). This also applies to the other two dictionaries. Accordingly, most words listed in Appendix 4 are available in these dictionaries, including dictyoptera, monophyletic and paraphyletic from a highly specialised subject such as entomology. The examples in Table 1 below illustrate that the idea that dictionaries do not provide explanations of meaning that are relevant to specialised disciplines is far from true. The dictionaries explain the terms that students looked up in ways that may provide assistance that addresses not only language but also subject knowledge gaps. However, it is the brevity of the definitions that would leave questions regarding the adequacy of assistance that students get in relation to complex questions about specialised subjects and topics.

Besides providing specialised explanations of meanings, the two editions of SACOD go further than the COED by including subject-field labels which indicate the disciplines, e.g. Astronomy, Biology, Linguistics, etc., in which the lexical items are used. In the case of polysemous lexical items doubling up as general words and subject-specific terms and registers, e.g. government, or even those that are used across disciplines with different meanings, e.g. discourse, the labels serve to disambiguate the senses by guiding the dictionary user to the appropriate disciplinary meaning. Not surprisingly, the majority of students who looked up discipline-specific terms during the June 2014 examinations indicated that their needs were successfully addressed. However, students' successful dictionary consultations and their claimed successes may not be necessarily translated into successful examination question responses or performance of assessment tasks. Such success could not be determined without access to students' examination scripts, and this was beyond the scope of the present study.

However, there are other students who were unsuccessful in getting the needed information from the dictionaries they consulted. In part, this was a result of inappropriate dictionary use. For example, students who looked up fundamental contradiction in politics would have been unfortunate because what they looked for is a context-embedded expression rather than a disciplinary term, while those who looked up fundamental separately would not have benefitted either because they would have gotten only a general sense of the word. The same applies to ubiquitous knowledge and ubiquitous in the case of an Information Systems examination.

9. Efficacy of dictionary use under examination conditions

Notwithstanding its (possible) benefits to its users, under examination conditions, the dictionary should not be used at all costs. Certainly not at the inconvenience of other examination candidates. It is most probably along this reasoning that certain rules, albeit not documented as part of the Rhodes guidelines for invigilators, have to be applied when dictionary requests arise and are dealt with by invigilators. During an examination, when a candidate requests a dictionary, the invigilator is supposed to hand it over to the student, wait as the student consults the dictionary and collect it immediately to make it readily available for the next student who makes a similar request. The candidate should not overstay his/her consultation time with the dictionary.

Generally, students who used the dictionary during the 2014 examinations reported through Questionnaire 3 that the dictionary was generally handed on time and benefitted them. However, some candidates were concerned that they were not allowed to bring their own dictionaries and that the university supplies no more than two copies per venue. One candidate who identified herself as a regular dictionary user from her primary school days reckoned that being allowed to bring own dictionaries would benefit her more instead of having to regularly request one only for the invigilator to wait impatiently for her to finish. This actually links up with a concern that was expressed by first year students that they would not use a dictionary in an exam and the returning students who indicated that they had not previously used the dictionary because it could cost them valuable examination time, a concern raised in relation to other aids and notes used in open-book examinations (Boniface 1985: 201). However, this particular candidate even indicated that there were instances where she would do without the dictionary despite experiencing the need fearing that she would be deemed unintelligent because of her frequent dictionary use during examinations. Despite what was reported through questionnaires, observations also indicated some problems which result in the practice failing to adhere to the stipulated guidelines. That some examination candidates admitted that they were not regular dictionary users outside examinations manifested itself in the form of observed poor dictionary skills. Some students would page back and forth trying to find the words, with panic and frustration indicating that they were indeed struggling. This would result in them failing to get what they were looking for and even keeping the dictionary longer, with the invigilator or other students waiting.

Another problem pertains to students who seemed to be generally unknowledgeable about dictionary use. Instead of looking up meaning promptly and continue with the exam, some students seemed to regurgitate dictionary data, looking in the dictionary, writing a few words on the answer script, looking again, and writing again. Thus some students were not processing dictionary data to apply it to their answers. Instead, they seemed to take the data for answers. Yet no regulation empowers invigilators to monitor how exactly the dictionary is used. This makes the instruction stipulating that invigilators check what students need in Law examinations even difficult to apply. The management of dictionary requests and dictionary use is only one of the several responsibilities of the invigilators. Giving space to a current dictionary user and the need to also attend to other candidates sometimes means a prolonged hold of the dictionary by one candidate at the expense of others. During the Introduction to Science Concepts and Methods exam, where more than 60% of the candidates used the dictionary, there were instances when the need for the dictionary was so high that several students would wait long for the dictionary. The student with the dictionary would also be under extreme pressure, something that any intervention under examination conditions should be addressing rather than exacerbating.

Perhaps the most problematic issue about the dictionary use practice discussed in this article pertains to the use of different dictionaries. For the university, it probably does not matter, given the popular misconception that all dictionaries dealing with the same language are the same. Unfortunately, students may get different forms of assistance depending on the venue of their examination and the copy that would be available at the time of request. The SACOD adapted the OCED to make it accessible for South Africans while the 2nd edition of the SACOD did not only seek to update the dictionary but also to increase its accessibility. The accessibility levels of the dictionaries vary. For example, the word genocide, which was looked up by students writing the Political Science examination is defined as "the mass extermination of human beings, esp. of a particular race or nation" by the COD, while the SACOD (2nd Ed.) defines it as "the deliberate killing of a very large number of people from a particular ethnic group or nation". Both definitions are factually correct, but the reference to "mass extermination of human beings" instead of "killing of a very large number of people" in the COD may require other students, especially non-mother speakers of English, to further look up extermination. In other words, the COD definition may be more accessible to mother-tongue speakers of English than to their non-mother-tongue counterparts whom the practice is thought to support more. Such a flaw is fatal to the claim that the dictionary is a linguistic intervention for English additional language learners during examinations at Rhodes University.

10. Conclusion

This paper has presented an empirical picture of dictionary use under examination conditions at Rhodes University. This picture displays some irregularities regarding the practice. Unlike the lexicographer, "a harmless drudge" according to Samuel Johnson's (in)famous definition in his landmark A Dictionary of the English Language, the dictionary in examinations is not always harmless, depending on its type and how it is used. That students looked up and managed to obtain curriculum-relevant information from the dictionary for examination purposes is not surprising from the perspective of pedagogical lexicography. What is rather surprising is the naivety of academics who believe that dictionaries are merely linguistic tools with no relevance to the broader academy. Not only English additional language students use dictionaries in examinations, but also their mother-tongue counterparts. While a few students looked up words to confirm spelling and meaning of words that would impede their comprehension of examination questions, the majority needed subject-related information, including what should have been covered in their courses. More importantly, the dictionaries used provide such information, although the accessibility levels vary across the three dictionaries that are used, with mother-tongue English speakers having a better chance of benefiting more since the explanations are in their language.

Although dictionary use in examinations seems to be irregular according to the present study, this does not reduce the pedagogic value of dictionaries. Like the other aids used in open-book examinations, the dictionary may become harmful in the hands of a candidate who is not an experienced dictionary user or the one who has not prepared well for the examination, as observed in this study. As Stalnaker and Stalnaker (1934: 117) argue:

The case for open-book examinations involves the importance of knowing where to find information, how to evaluate it, and how to use it.

Academics also need to play a role in developing dictionary skills and think about how dictionaries can be used as resources in the curriculum, and formulating questions in a manner that may effectively assess rather than compromise what is being assessed. Not only will dictionaries prove to be useful linguistic tools, but also alternative pedagogical resources.

Acknowledgement

The author is indebted to Simthembile Matyobeni and Sisonke Mawonga who were the research assistants in this study. The two research assistants were responsible for administering Questionnaires 1 and 2, as well as data capturing.

References

Dictionaries

Johnson, S. 1755. A Dictionary of the English Language. London: J. & P. Knapton/T. & T. Longman et al. [ Links ]

Kavanagh, K. (Ed.). 2002. South African Concise Oxford Dictionary. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Thompson, D. (Ed.). 1995. The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Current English. Ninth edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [ Links ]

Van Niekerk, T. and J. Wolvaardt (Eds.). 2010. The Oxford South African Concise Dictionary. Second edition. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Other Literature

Atkins, B.T.S. (Ed.). 1998. Using Dictionaries. Studies of Dictionary Use by Language Learners and Translators. Lexicographica. Series Maior 88. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer. [ Links ]

Atkins, B.T.S. and M. Rundell. 2008. The Oxford Guide to Practical Lexicography. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Barnes, A. et al. 1999. Dictionary Use in the Teaching and Examining of MFLs at GCSE. Language Learning Journal 19(1): 19-27. [ Links ]

Béjoint, H. 2010. The Lexicography of English. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Bensoussan, M. 1983. Dictionaries and Tests of EFL Reading Comprehension. ELT Journal 37(4): 341-345. [ Links ]

Bergenholtz, H. and S. Tarp. 2003. Two Opposing Theories: On H.E. Wiegand's Recent Discovery of Lexicographic Functions. Hermes, Journal of Linguistics 31: 171-196. [ Links ]

Bishop, G. 2000. Developing Learner Strategies in the Use of Dictionaries as a Productive Language Learning Tool. Language Learning Journal 22(1): 58-62. [ Links ]

Boniface, D. 1985. Candidates' Use of Notes and Textbooks during an Open-book Examination. Educational Research 27(3): 201-209. [ Links ]

Boughey, C. 2002. 'Naming' Students' Problems: An Analysis of Language-related Discourses at a South African University. Teaching in Higher Education 7(3): 295-307. [ Links ]

Chen, Y. 2012. Dictionary Use and Vocabulary Learning in the Context of Reading. International Journal of Lexicography 25(2): 216-247. [ Links ]

Cowie, A.P. 2002. English Dictionaries for Foreign Learners: A History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Dziemianko, A. 2010. Paper or Electronic? The Role of Dictionary Form in Language Reception, Production and the Retention of Meaning and Collocations. International Journal of Lexicography 23(3): 257-273. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. 2010. The Monolingual Specialised Dictionary for Learners. Fuertes-Olivera, P.A. (Ed.). 2010. Specialised Dictionaries for Learners: 55-68. Berlin: De Gruyter. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. 2013. Establishing and Developing a Dictionary Culture for Specialised Lexicography. Jesensek, V. (Ed. ). 2013. Specialised Lexicography. Berlin: De Gruyter. [ Links ]

Gouws, R.H. and D.J. Prinsloo. 2005. Principles and Practice of South African Lexicography. Stellenbosch: SUN PReSS. [ Links ]

Graham, T. et al. 2003. The Use of Graphics Calculators by Students in an Examination: What Do They Really Do? International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology 34(3): 319-334. [ Links ]

Kemp, M. et al. 1996. Graphics Calculator Use in Examinations: Accident or Design? Australian Senior Mathematics Journal 10(1): 36-50. [ Links ]

McArthur, T. 1986. Worlds of Reference. Lexicography, Learning and Language from the Clay Tablets to the Computer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Ministry of Education. 2002. Language Policy for Higher Education. Pretoria.

Monaghan, J. 2000. Some Issues Surrounding the Use of Algebraic Calculators in Traditional Examinations. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology 31(3): 381-392. [ Links ]

Nesi, H. and R. Haill. 2002. A Study of Dictionary Use by International Students at a British University. International Journal of Lexicography 15(4): 277-305. [ Links ]

Nielsen, S. 2015. Legal Terms in General Dictionaries of English: The Civil Procedure Mystery. Lexikos 25: 246-261. [ Links ]

Nkomo, D. 2015. Developing a Dictionary Culture through Integrated Dictionary Pedagogy in the Outer Texts of South African School Dictionaries: The Case of Oxford Bilingual School Dictionary: IsiXhosa and English. Lexicography 2(1): 71-99. [ Links ]

Nkomo, D. 2016. An African User-Perspective on English Children's and School Dictionaries. International Journal of Lexicography 29(1): 31-54. [ Links ]

Rhodes University. 2006. Language Policy. Grahamstown: Rhodes University. [ Links ]

Rhodes University. 2014. Revised Language Policy. Grahamstown: Rhodes University. [ Links ]

Rundell, M. 1999. Dictionary Use in Production. International Journal of Lexicography 12(1): 35-54. [ Links ]

Scholfield, P. 1999. Dictionary Use in Reception. International Journal of Lexicography 12(1): 13-34. [ Links ]

Stalnaker, J.M. and R.C. Stalnaker. 1934. Open-book Examinations. The Journal of Higher Education 5(3): 117-120. [ Links ]

Taljard, E. et al. 2011. The Use of LSP Dictionaries in Secondary Schools - A South African Case Study. South African Journal of African Languages 31(1): 87-109. [ Links ]

Tarp, S. 2008. Lexicography in the Borderland between Knowledge and Non-knowledge: General Lexicographical Theory with Particular Focus on Learner's Lexicography. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer. [ Links ]

Tarp, S. and R.H. Gouws. 2012. School Dictionaries for First-Language Learners. Lexikos 22: 333-351. [ Links ]

TermNeT. http://www.termnet.org/ (Accessed 23 March 2016).

Wiegand, H.E. 1984. On the Structure and Contents of a General Theory of Lexicography. Hartmann, R.R.K. (Ed.). 1984. LEX'eter '83 Proceedings. Papers from the International Conference on Lexicography at Exeter, 9-12 September 1983: 13-30. Lexicographica. Series Maior 1. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag. [ Links ]

Zgusta, L. 1971. Manual of Lexicography. The Hague: Mouton. [ Links ]

Examination papers cited in the article

Introduction to Science Concepts & Methods Paper 1. Examination. June 2014. Rhodes University.

Information Systems 201. Examination. June 2014. Rhodes University.

Entomology 202 - Theory Paper 1. Examination. June 2014. Rhodes University.

Art History and Visual Culture 1. Examination. June 2014. Rhodes University.

Puzzles in Contemporary Political Philosophy and Introduction to Political Theory, Paper 1. Examination. June 2014. Rhodes University.

Introduction to Science Concepts and Methods, Paper 1. Examination. June 2014. Rhodes University.

Legal Pluralism. Examination. June 2014. Rhodes University.

* This article was presented as a paper at the Nineteenth Annual International Conference of the African Association for Lexicography (AFRILEX), which was hosted by the Research Unit for Language and Literature in the SA Context, North-West University, Potchefstroom Campus, Potchefstroom, South Africa, 1-3 July 2014.