Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Lexikos

On-line version ISSN 2224-0039

Print version ISSN 1684-4904

Lexikos vol.27 Stellenbosch 2017

ARTICLES

Koalas, Kiwis and Kangaroos: The Challenges of Creating an Online Australian Cultural Dictionary for Learners of English as an Additional Language

Koalas, kiwi's en kangaroes: Die uitdagings in die skep van 'n aanlyn Australiese kulturele woordeboek vir aanleerders van Engels as 'n addisionele taal

Julia MillerI; Deny A. KwaryII; Ardian W. SetiawanIII

ISchool of Education, The University of Adelaide, Australia (julia.miller@adelaide.edu.au)

IIDepartment of English Literature, Airlangga University, Indonesia (kwary@yahoo.com)

IIIThe State Polytechnic Manufacture Bangka Belitung, Sungai Liat, Indonesia (ardian.setiawan@gmail.com)

ABSTRACT

This article reports on an online cultural dictionary for learners of English as an Additional Language (EAL) in Australia. Potential users studying English for academic purposes in an Australian university pre-entry program informed each stage of the dictionary's creation. Consideration was given to the need for such a dictionary; terms to be included; information necessary for each entry (including audio and visual material); use of a limited defining vocabulary; example sentences; notes on each term's usage; and evaluation of user feedback once the dictionary had been launched online. Survey data indicate that users particularly value the dictionary's ease of use, example sentences, and specifically Australian content (including pronunciation given in an Australian accent). It is suggested that more entries be added, and that cultural dictionaries be created for other varieties of English, as well as for other languages.

Keywords: Australian, culture, dictionary, English as an additional language, learner's dictionary, online

OPSOMMING

In hierdie artikel word verslag gedoen oor 'n aanlyn kulturele woordeboek vir aanleerders van Engels as 'n Addisionele Taal (EAT) in Australië. Potensiële gebruikers wat Engels vir akademiese doeleindes in 'n Australiese universiteitstoelatingsprogram studeer, het die inligting vir elke fase in die skep van die woordeboek verskaf. Daar is oorweging geskenk aan die behoefte aan so 'n woordeboek; terme wat ingesluit moet word; inligting wat benodig word vir elke inskrywing (insluitend oudio- en visuele materiaal); die gebruik van 'n beperkte definiëringswoordeskat; voorbeeldsinne; notas oor die gebruik van elke term; en die evaluering van gebruikersterugvoer nadat die woordeboek aanlyn verskyn het. Data verkry uit die vraelyste dui daarop dat gebruikers spesifiek waarde heg aan die gebruikersvriendelikheid, voorbeeldsinne, en spesifiek Australiese inhoud (insluitend uitspraak gegee in 'n Australiese aksent). Daar word voorgestel dat meer inskrywings bygevoeg word, en dat kulturele woordeboeke geskep word vir ander variëteite van Engels, sowel as vir ander tale.

Sleutelwoorde: australies, kultuur, woordeboek, engels as addisionele taal, aanleerderswoordeboek, aanlyn

Background

Studying in another country usually requires a good command of that country's language. For example, a speaker of English as an additional language (EAL) who wants to study in an Australian university will usually need to obtain a minimum International English Language Testing System (IELTS) score of 6. However, this level of English does not prevent the student from having problems when encountering English words in daily life. For example, on arriving in Australia they might look for a meal and see the word brekkie on a board outside a café. Not knowing the meaning of brekkie, they consult a dictionary but cannot find an entry. Indeed, brekkie appears in only one of the major English learner's dictionaries (the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary). They would also be unlikely to find the word in a bilingual dictionary. Brekkie in fact is the Australian slang word for breakfast. Even on deciphering this meaning, however, further problems arise: what constitutes breakfast in Australia, and when do people eat this meal?

In these days of easy Internet access (in many countries, though not necessarily throughout the vastness of outback Australia), it is relatively simple to search for a word online, using either a computer, a tablet or a mobile phone. Even then, however, the student may run into problems. Urban Dictionary is likely to show up first in a search for slang words such as brekkie (though of course the student does not initially know that brekkie is slang). The definitions in Urban Dictionary may include accurate explanations, but these can be obscured by misleading information, inaccurate spelling, or highly colourful language. Brekkie, for example, has three Urban Dictionary entries, each with an example sentence incorporating its use (given here in brackets):

1. Abbreviation of breakfast. (Couldn't be arsed to eat brekkie this morning.)

2. An Australian slang term for breakfast. (I had eggs and tomato on toast for brekkie today.)

3. A person who is obssesed with the breakfast club. Kinda like a trekkie. But insted a brekkie. (Ashley is obssesed with the breakfast club i consider her as a brekkie.)

(Urban Dictionary, accessed on 3 December 2015)

The second definition here is accurate, and uses a helpful example which elaborates on the content of a possible Australian breakfast. The first definition is adequate, although the example sentence is confusing and contains a taboo word. The third definition is confusing, badly spelled, and uninformative. Other common Australian words fare even worse on this site, with the innocent koala receiving 27 definitions, including the alarming and misspelt:

A very dangerous mammal that is prone to attack. Also poisonous, these are deadly beast which we must protect ourselves from. Even now many officials are considering bombing all koala habits to destroy these dangerous beasts. Alternate definiton: a whore.

It is evident, then, that students should be guided towards trustworthy dictionaries, and in fact all the six major English learner's dictionaries are freely available online: Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary (CALD), Collins COBUILD Advanced Dictionary (COBUILD), Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English (LDOCE), Macmillan English Dictionary for Advanced Learners (MEDAL), Merriam-Webster Learner's Dictionary (MWLD), and Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary (OALD). unfortunately, however, these dictionaries are mainly aimed at the British or American English markets, and fail to include many terms used in other English-speaking countries. Australia used to have a dictionary for advanced learners, the excellent Macquarie Learner's Dictionary (1999), but this is no longer published. The Australian National Dictionary (2016) and Macquarie Dictionary (2013) are designed for native speakers of English and do not contain all the information a learner may need. Moreover, although they are available online, they are not free to use. There is thus a need for a reliable dictionary for EAL learners in Australia, since Australian cultural references are frequently missing from the existing learner's dictionaries. A cultural dictionary of Australian terms for EAL learners would help to fill this gap, and a freely available online version would make such a dictionary easily accessible.

Literature review

In compiling a learner's dictionary, at least eleven factors need to be considered: dictionary medium; definition style; spelling variations; grammatical information; pronunciation guide; defining vocabulary; usage labels; example sentences; audiovisual material; language variety; and cultural context. All of these must relate to the needs of the proposed dictionary user, who in this case is an adult EAL learner in Australia.

- Dictionary medium

Online dictionaries are superseding paper dictionaries, and in some cases (e.g. Macmillan) publishers are no longer producing hard copy dictionaries and are only publishing online. This is unfortunate for those people who do not have Internet access. Nevertheless, for those producing a dictionary under a limited budget, the advantages of an online dictionary are manifold. There is no limit as to space, because there are no printing costs; audiovisual material can be incorporated more cheaply; and it is easier to update the material in the dictionary. Despite these advantages, however, it is still important that users' needs be considered and that the lexicographer should not be carried away by the potential of the new online medium (Gouws 2011: 21).

There is debate over the terminology to describe online dictionaries. Lew and De Schryver (2014: 342-344) examine the terms 'electronic dictionary', 'e dictionary', 'digital media dictionary', 'digital dictionary', and 'online dictionary', and predict that the term 'online dictionary' may well become the term favoured by lexicographers and metalexicographers. Since the dictionary described in this paper is purely online, and this term is favoured by many writers, we have chosen the term 'online dictionary' to describe our work.

- Definition style

The style of definition in the leading English learner's dictionaries varies. While CALD, LDOCE, MEDAL, MWLD, and OALD all use an analytical format (Lew and Dziemianko 2006: 229) based around a phrase (e.g. emphasis: special importance that is given to something (OALD online 7 April 2015) ), COBUILD is distinctive in using a sentence definition (emphasis: Emphasis is special or extra importance that is given to an activity or to a part or aspect of something (COBUILD online 7 April 2015) ). The sentence definition has been criticized for its uneconomical length (Cowie 1999: 160). However, this is no longer a problem in an online dictionary.

- Spelling variations

One of the most common reasons for consulting a dictionary is to verify a word's spelling (e.g. Harvey and Yuill 1997: 259), and it is standard practice in dictionaries to provide spelling variations. These variations may reflect differences within the same variety of a language (e.g. hello/hallo/hullo in UK English) or differences between language varieties (e.g. litre in UK English and liter in American English).

- Grammatical information

information on a word's part of speech and other grammatical features is an important element in a learner's dictionary (Zgusta 2006), although it is not clear how much users refer to this information (Bogaards 2001: 105), especially if it is given in codified form (Lew and Dziemianko 2006: 226). For example, the symbol 'U' might represent the fact that a noun is uncountable, but users may be unaware of this because they fail to consult the dictionary's user guide. in fact, research suggests that users gain grammatical information more by seeing a word used in an example sentence (Dziemianko 2006) than by following a dictionary code. These reservations notwithstanding, grammatical information can be used to good effect by learners and teachers if they are aware of its existence and usefulness.

- Pronunciation guide

Learners' needs, and changes in English pronunciation according to the variety of English, have led to the inclusion of IPA characters in learner's dictionaries (Häcker 2012), compared to other systems of pronunciation, such as the use of diacritics and ordinary Roman alphabetic symbols (Fraser 1997). Online dictionaries can also provide audio files, and recent research (reviewed in Lew 2015) indicates that users highly value this feature, although Lew (2015) recommends that phonemic transcriptions also be included to raise awareness of phonemic contrasts with users' first languages.

- Defining vocabulary

One key pedagogical factor in the design of learner's dictionaries is the use of a limited defining vocabulary (DV), so that learners are not faced with incomprehensible words in definitions. The idea of such a vocabulary was first created by West and Endicott in The New Method English Dictionary of 1935 (Cowie 1999: 24). In that dictionary, 1490 words were used to define 23,898 entries (Cowie 1999: 24). Even such a limited list of defining words can pose problems for learners, however, and each DV word may itself need to appear as a headword (Cowie 1999: 24). Of the current advanced learner's dictionaries, LDOCE was the first to use a DV of around 2000 words (Procter et al. 1978: viii-ix), based on West's (1953) General Service List of English Words. Most of the other learner's dictionaries also use a controlled DV. CALD (2008) has 2000 words; COBUILD (2009) has 3197; LDOCE (2003: 1943) has 'around 2000 common words'; MEDAL (2002: 1677) has 'under 2500 words'; and OALD (2010: R43) uses 'keywords' from the Oxford 3000 list. MWLD does not have a defining vocabulary, but includes a list of 3000 core vocabulary words. There is a tendency to understate the number of words used in a DV (Cowie 1999: 110), and to list only one word (the lemma) in the DV when in fact three words are used in definitions within the dictionary. For example, COBUILD (online, 6 March 2015) lists only accident in its DV, but the words accidental and accidentally are used in the definitions of collateral damage and bump, respectively.

Another problem arises when a word is needed for a definition but falls outside the DV because it is of a technical nature. Three British learner's dictionaries (MEDAL, LDOCE, and OALD) use small capital letters for these extra words, with either an explanation in brackets immediately after the word or a link to the extra word's entry in the main dictionary. For example, LDOCE (2003: 1943) defines kangaroo as 'an Australian animal that moves by jumping and carries its babies in a POUCH (= a special pocket of skin) on its stomach'. Similarly, MEDAL (2002) defines kangaroo as 'a large Australian animal that moves by jumping, has strong back legs, and carries its baby in a POUCH (= pocket on the front of its body)'. Pouch is a technical word that is explained in the LDOCE and MEDAL definitions because it is not commonly used and so is not part of the DV. OALD (2010: 844) reverses the explanation and use of the word pouch and defines kangaroo as 'a large Australian animal with a strong tail and back legs that moves by jumping. The female carries its young in a pocket of skin (called a POUCH) on the front of its body.' One might question the need for the word pouch in this definition, since it appears after its explanation ('a pocket of skin'). CALD omits any reference to a pouch. COBUILD (2009) and MWLD use the word pouch in their definitions, but do not highlight it or explain it in any way. They do, however, define pouch under its own separate headword, although this is not hyperlinked from kangaroo. These varied examples indicate the problem of using technical or more unusual words in definitions. However, there is a limit to how simple a definition needs to be. Xu (2012: 369), for example, criticizes the LDOCE definition of tabasco as 'a very hot-tasting liquid' for being 'unnatural'. Furthermore, there are some words, such as marsupial, which are essential to a definition and yet hard to explain. None of the kangaroo definitions above includes this word, and yet, to be accurate, it is important to distinguish a mammal from a marsupial, particularly in a country such as Australia which has many marsupials.

- Usage labels

Labels in dictionary entries enable users to know the part of speech, as well as the register, frequency, and context of a word in everyday discourse. Words that are not labeled are considered to represent standard usage (Kipfer 1984: 140), but the application of labels to entries is often problematic. Currency and frequency of use, for example, may change according to the age of the user. Furthermore, labels such as old-fashioned are used inconsistently in the advanced learner's dictionaries (Miller 2011), sometimes indicating that a word is used mainly by older people and at other times indicating that the word is passing out of use altogether. At the opposite end of the age spectrum, many new words used by younger age groups may prove to be ephemeral, and it is hard to keep track of these in a dictionary, although online versions make the updating process easier. Context is also important: is a word used by everyone in all circumstances, or is its use restricted in some way? It is important for learners to be aware of such details and to know which words are used in which circumstances by a certain age group (Atkins and Rundell 2008: 229). Currency and usage can be indicated in a dictionary by means of a usage label and further portrayed in the example sentences. Frequency of use information requires corpus data in order to be accurate.

- Example sentences

Sentences which exemplify usage are vital for learners, in that they not only explain but also model native speaker use of a language (Sinclair et al. 1987: xv).

For this reason, authentic examples of use, taken from native speaker corpora, are preferable to invented sentences. Such example sentences must, however, complement the definition. In the third Urban Dictionary entry quoted in the introduction to this paper, the example sentence (Ashley is obssesed with the breakfast club i consider her as a brekkie) adds nothing helpful to the definition. The first example (Couldn't be arsed to eat brekkie this morning) tells the reader that brekkie is something edible and that it is eaten in the morning, which is helpful. The second example sentence, however (I had eggs and tomato on toast for brekkie today), shows the reader that have collocates with breakfast, and that eggs, tomato and toast are examples of breakfast food. It is therefore much more informative, although it still does not tell the reader at what time of day the meal is eaten. Example sentences thus need to be both authentic and informative so that they illustrate the headword and show its use in a real life contest. In our dictionary, example sentences were taken wherever possible from the Australian version of the VOLE corpus in Sketch Engine. Where words did not appear in the VOLE corpus, an Australian Internet search was conducted to find suitable examples. All example sentences were chosen because they not only showed the word in use in a sentence but also added a dimension of understanding to the term. As in LDOCE (2003), words used in the example sentences were not restricted to the defining vocabulary, as to do so would have placed unnatural limits on the examples and excluded the use of most of the authentic corpus illustrations.

- Audiovisual material

Dictionaries should be user friendly, with data that match what users need and that are presented 'in a convivial, pedagogical and easy-to-use way' suitable for a particular user situation (Heid 2011: 289, 290). This may entail factors such as the appearance of the dictionary interface, the layout of the contents, and the principles upon which the dictionary is based. Online dictionaries make it easier to include images, audio clips, and video clips, and to hyperlink to other entries within the dictionary. These features are not without potential problems, however. Lew (2011: 246) indicates that online dictionaries of English have not yet used video imagery to a great extent and that, in any case, animated images do not aid vocabulary retention. Other researchers (for example, Chun and Plass 1996) have indicated that static images are more effective than videos in helping users to remember vocabulary. However, it should be noted that while retention is a desirable outcome of dictionary use, initial comprehension of a term is equally important, and both static and video images may have a role to play here (cf. Atkins and Rundell 2008: 210-211; Svensén 2009: 298; Ogilvie 2011: 393). Audio files can add to the richness of an online dictionary, but so far all the main learner's dictionaries contain only British or US English pronunciation. This fails to cater for the decoding and encoding needs of language learners in other English speaking countries.

- Language variety

Among the countries in which a language is spoken as either a first or official language, it is inevitable that variations of that language will occur. For example, Australia has its own variety of English, originating from the children of the first British settlers who arrived in Australia early in the nineteenth century (Delbridge 1983: 36). However, Australian English only came to be recognized in its own right a few decades ago (Peters 2001). Apart from its own pronunciation, Australian English is often marked by colloquial terms and informality of style (Peters 2007: 251) with a tendency to shorten words, so that biscuit becomes bikkie and breakfast becomes brekkie. Informality is seen in words such as Kiwi, used to refer to inhabitants of New Zealand, and Pom/Pommy used (not always flatteringly) to refer to a British person.

- Cultural context

In addition to style and pronunciation, each variety of a language reflects the culture in which it is used. The word 'culture' refers to the values, beliefs and customs held or practised by a social group over the generations (Bolaffi et al. 2003: 61). Culture may be made explicit through language, and, in fact, Zgusta (2006) emphasizes that every word of a language is 'embedded in culture' (p. 114). A cultural dictionary may include terms that are not unique to a particular culture, but may have special significance within it or be used frequently by people in that country (Béjoint 2011).

Because a cultural dictionary could include references to events, such as Australian Rules football matches, and other items, such as road signs, the phrase 'culturally bound term' is useful. A culturally bound term is 'a cultural entity that is unique to a particular language and culture in a country, or has a unique meaning in that country among a certain cultural group' (Kwary and Miller 2013).

A dictionary of Australian culturally bound terms could benefit international students, migrants, tourists, and business people visiting the country, as well as anyone who is simply curious to see a list of terms commonly associated with Australia. Because Australia is a vast country, with six states and two territories, culturally bound terms may differ from place to place. Nevertheless, many terms are commonly used throughout the country.

Study

Aim

This action research study focuses on the needs of international students in Adelaide, the capital city of the state of South Australia. It details the process by which an online Australian cultural dictionary was created and provides guidelines for those wishing to construct a similar resource.

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the University of Adelaide's ethics committee, and all students involved in the study received information and complaints procedure sheets, and signed a consent form. There were nine stages in the dictionary's development.

Stage 1

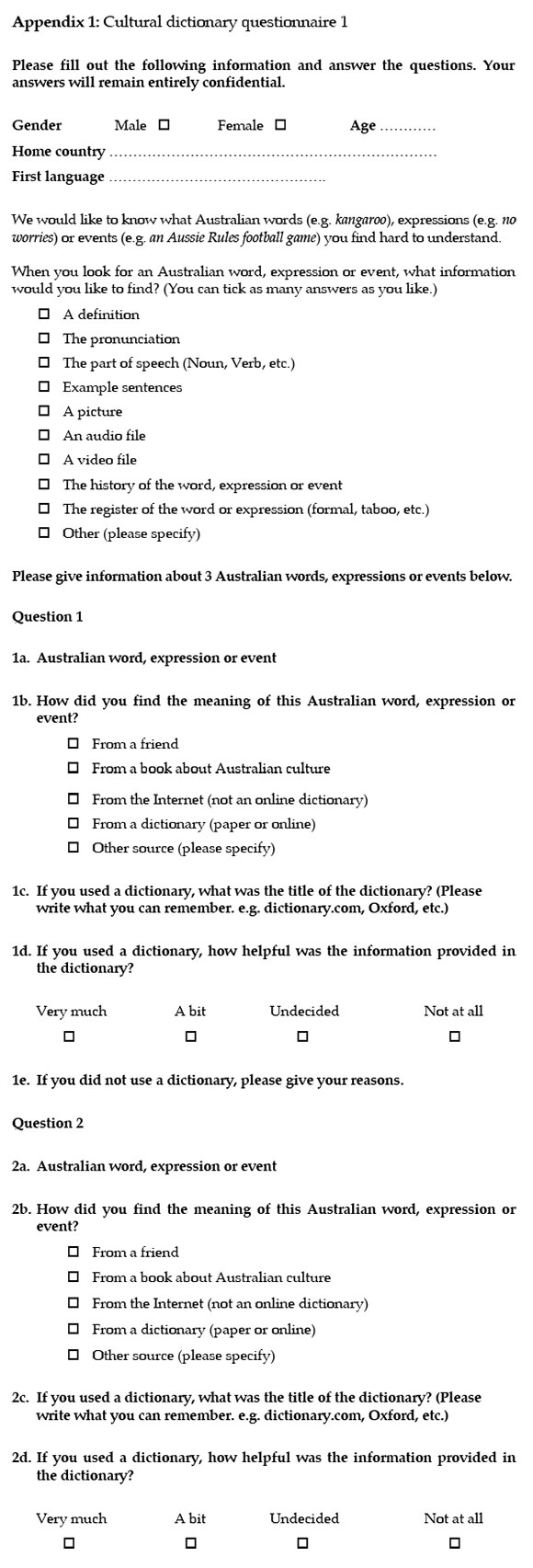

In order to establish which words needed to be included in an Australian cultural dictionary (ACD) for EAL learners, a paper questionnaire was administered to 269 international students on a 20 week pre-enrolment English program (PEP) which prepared them for entry to a South Australian University. (Please see Appendix 1 for details of the questionnaire.) The questionnaire requested details of each student's age, gender, home country, and first language. Students were then asked what information they would like to find in a dictionary (e.g. definition, part of speech, pronunciation). Finally, they were asked to list three Australian words or expressions that they found hard to understand, and requested to say where they had found out the meaning of that word, whether they had used a dictionary, and, if so, how helpful that dictionary had been. The three words or expressions most frequently elicited from all the students were then incorporated in a second written questionnaire.

Stage 2

The second questionnaire (see Appendix 2) presented a new group of international students on the PEP course (n = 337; similar demographics to the first group) with three terms (koala, brekkie, and Royal Adelaide Show) highlighted as problematic by students responding to the first questionnaire. These terms were presented in three ways:

Version A: existing online dictionary entries for koala (OALD online), brekkie (Macquarie Dictionary), and Royal Adelaide Show (based on the entry for show in CALD online)

Version B: our own definition, together with IPA pronunciation, pictures, parts of speech, and example sentences

Version C: our own definition, together with IPA pronunciation, pictures, parts of speech, and example sentences, amplified by historical and more encyclopaedic information, together with a word history

The majority of the students (75%) preferred version B. In other words, they wanted a definition that was more complete than that found in a normal learner's dictionary, but they did not want to be swamped by encyclopaedic information or etymology. This is in line with Szczepaniak and Lew (2011)'s suggestion that users may pay little attention to etymological information in a dictionary entry.

Stage 3

A third questionnaire (see Appendix 3) was later presented online to a third cohort of students from the same course (n = 97), in order to cross check the suggestions in questionnaire 1 and elicit more terms necessary for an Australian cultural dictionary.

Stage 4

The terms suggested by students in questionnaires 1 and 3 were conflated, and any words or expressions mentioned at least twice were included in a database, leading to the following entries: Aboriginal; the Adelaide Festival; the Adelaide Fringe; the Royal Adelaide Show; Anzac day; Anzac biscuit; arvo; Aussie; Aussie Rules; barbie; barrack for; bbq; beaut; bickie/bikkie; big/small bickies/bikkies; bikie; billy; bloke; bludge; bludger; bogan; Bottoms up!; brekkie; budgie smugglers; bush tucker; byo; Centrelink; chip; chook; Christmas Pageant; cricket; Dagwood dog; deli; dingo; (duckbill) platypus; dob in; dummy; dummy run; dunny; echidna; eftpos/EFTPOS; emu; esky; fair enough; footy; g'day; goanna; Good on ya!; heaps; Hills hoist; Hockeyroo; hoon; hotel; How are you going?; How's it going?; It's your call; kangaroo; kiwi; Kiwi; kiwifruit; koala; lamington; lolly; marsupial; mate; Milo; No worries; O-Bahn; outback; pie floater; pokies; Pom; Pommy; (I) reckon; rort; sanga; See ya; She'll be right; showbag; Socceroo; Strine; spill; spruik; stoush; stubby holder; sunnies; sweet as; swag (=collection); swag (=bedding roll); Tasmanian devil; tax file number; tea (= evening meal); thongs; tracky dacks; tragic; Ugg boots; Uluru; ute; Vegemite; wallaby; Wallaby; What are you after?; What's up?; wombat; yakka; Zombie Walk.

Some terms not unique to Australia (alpaca; the Ashes; Brussels sprout; cheers; cuppa; Long time no see; spread oneself too thin; Sugar!; ta; tea; tram; vertical garden; yonks; and yummy) were salient to the participants and so were also included in the dictionary. Other terms (e.g. chip, hotel, lolly) may appear in British dictionaries, but have a different meaning in Australia. Only 28 of the terms appeared in all the 'Big 6' English learner's dictionaries, while 31 did not appear in any of them.

Stage 5

An online Australian cultural dictionary for English language learners was then developed, based on the terms in the database. For each word, the part of speech, IPA pronunciation, and grammatical information (e.g. countable or uncountable noun) were provided. A simple definition was then written. The resulting definitions were circulated in an online survey to 20 adult native speakers of English in Australia who had lived for most of their lives in that country, with the request that they check the definitions for adequacy and accuracy. Changes were then made to the definitions based on the feedback of these speakers.

Stage 6

All the words used in the definitions, including information on part of speech and usage, were made into a corpus and analysed for frequency using Adelaide Text Analysis Tool (AdTAT) concordancing software (The University of Adelaide 2013). Numerals were removed from the resultant word list, as were words which were explained in the definition (e.g. backyard (garden)) or had their own definition (e.g. marsupial is used in various definitions, but has its own definition). Equivalents in other languages (such as Salut for Cheers) were also removed, and so were proper nouns relating to inventors (e.g. the Hills hoist: named after its inventor, Lance Hill). Another list was made in which only root words (such as quick or sandwich) were included in the defining vocabulary, and related parts of speech and plural forms (such as quickly, sandwiches) were removed. This resulted in a defining vocabulary of 845 words, 146 of which do not appear in any form in the Academic Word List (Coxhead 1998) or the New General Service List (Browne et al. 2013). Some of these, such as Australia, were not thought to present any difficulty to learners. However, there were still words in the defining vocabulary which occurred only once and which might not be entirely simple for learners. For example, desiccated, though it is the correct name of a type of coconut product, was thought to be too complicated, so the explanation dried was added in brackets afterwards. After all explanations had been added and simplifications made where possible, 33 words remained which might have been problematic for learners.

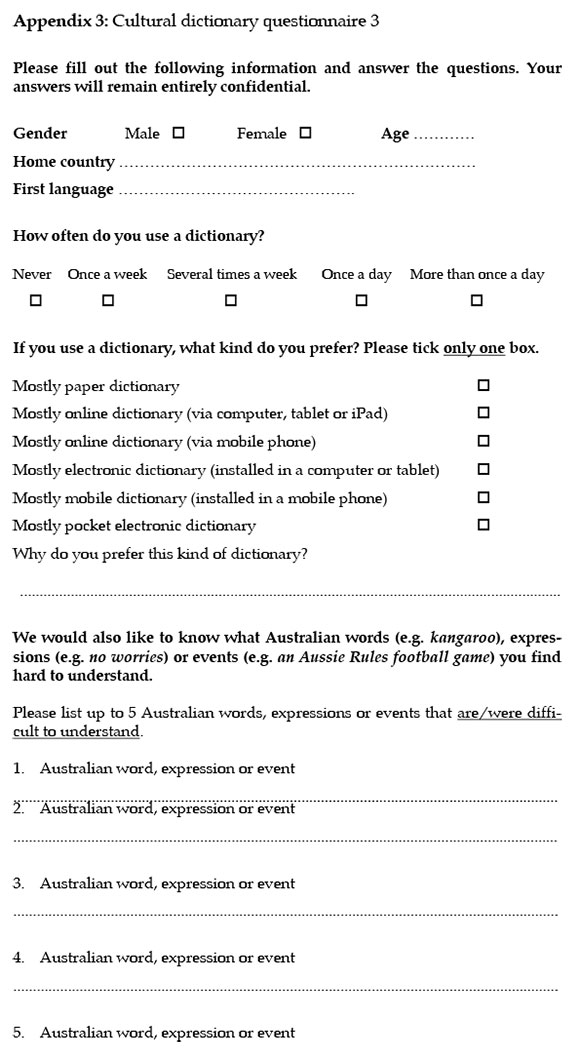

Stage 7

A fourth questionnaire was formed around these 33 defining vocabulary items to check student understanding of the terms. This online questionnaire was completed by 35 students on the PEP course (25 male, 10 female, average age 22, with 66% from China). This was a convenience sample, as all the students on the course were invited to complete the survey, but only 35 responded. Most of the students (89%) had been in Australia for one to four months, and their global IELTS scores ranged from 5 to 7, with many (71%) in the 5.5 to 6.5 brackets.

This defining vocabulary questionnaire gave the participants four possible meanings for a word and a 'don't know' option. For example, to test the understanding of the phrase arcade game the first question asked 'Which one of these is the best example of an arcade game?', with the answer options of 'darts', 'baseball', 'a poker machine', 'snooker' and 'I don't know'. Owing to the nature of the online survey program (SurveyMonkey) at that time, it was not possible to include a picture for each possible meaning. Twenty-four words were understood by 80% or more of participants. The remaining words were arcade game, fairground, frankfurter, lizard, malted, oats, overhead, eucalyptus and spikes. These words were either removed from the defining vocabulary or explained further. For instance, lizard is essential to the definition of goanna, but the definition was extended to 'Any type of Australian monitor lizard (a reptile with legs) from 20 centimetres to 2 metres long'. The word oats was retained in the definition of ANZAC biscuit, as oats are a central ingredient, and the more generic word grain might also not be recognized by students. Eucalyptus (with its more common alternative gum) was retained in the definition of koala because koalas are most commonly found in eucalyptus trees and eat eucalyptus leaves. The phrase long soft spikes was retained in the definition of echidna because the more suitable alternatives - quills or spines - were thought to be even less recognizable by students. Even the more established learner's dictionaries have trouble with defining quills: 'any of the long sharp pointed hairs on the body of a porcupine' (CALD); 'one of the long pointed things that grow on the back of a porcupine' (LDOCE); 'a long thin sharp object like a stick that grows from the body of porcupines and some other animals' (MEDAL); and 'one of the long sharp stiff spines on a porcupine' (OALD). We rejected spines because of possible confusion with vertebrae.

Stage 8

After all words and multimedia files had been collected, a new dictionary database was created using TLex software. For the sake of data standardization, the database was saved in TLex format (tldict file), meaning that all features of the software could be used easily. Next, the collected words were put into the database as new entries. Details were given for each word, including lemma sign, pronunciation/phonetic symbols, part of speech label, definition, and examples. Multimedia files (pictures, sounds, and videos) were assigned to the entries. The database was then exported into an HTML file. One HTML file was generated from each entry/word; all labels for the entries were included.

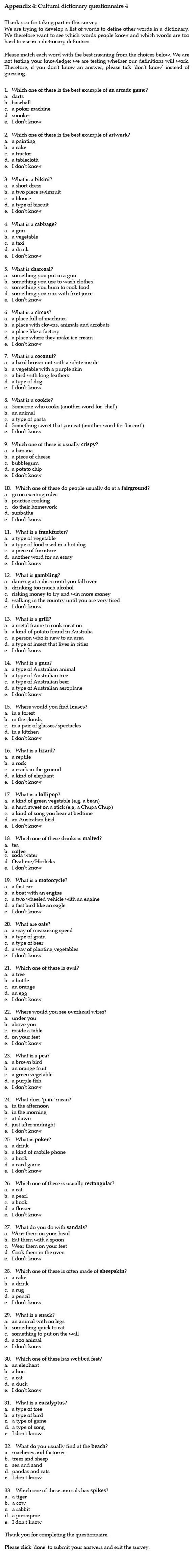

As TLex exports HTML files in plain text, an interface template for the dictionary website had to be designed (see Figure 1). In making the interface template, we considered consistency and predictability (Lynch and Horton 2008) in terms of the layout of the website and its paths or navigational links. Different pages on the site used the same template, and this was designed to be interesting for users and easily accessible. Links or elements were created and put on all HTML pages, which were designed to be accessible through devices such as desktops, tablets, and mobile phones. Therefore, the dimension of the interface template was set to be dynamic, having the ability to adapt to the height and width of the device screen.

In order to make a website easily accessible, HTML files and their components such as photos and audios must be small in size. Therefore, all multimedia files were compressed and resized. A domain name/hosting, www. culturaldictionary.org, was created, and all HTML files and the multimedia components were uploaded. HTML5 audio player was set as the player for the audio files because it is small, can be opened using most browsers and is routinely used for playing audio files on the Internet. However, we found that only Firefox, Chrome, Safari, Opera, and Internet Explorer 9 and above supported the HTML5 audio standard, and the audio files did not work on Internet Explorer 8 or earlier. We therefore added this caveat to the website. Rather than hosting video files on the website, the videos were uploaded to YouTube with links embedded on the HTML pages of the dictionary website. To track the traffic data of the website, Google analytics code was put on the home page.

Features of the Australian Cultural Dictionary

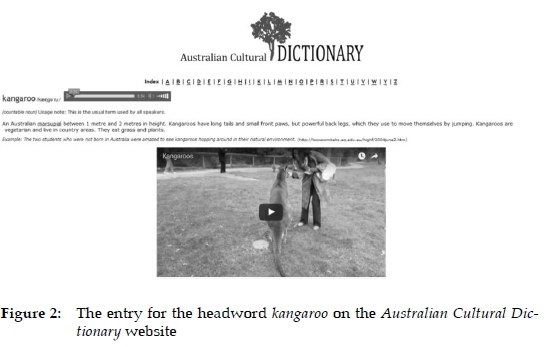

The ACD is a freely accessible online dictionary with 119 entries in its initial phase. Figure 2 shows an example of the dictionary entry for the headword kangaroo.

As can be seen in Figure 2, an entry consists of a headword, pronunciation, grammatical information, usage note, definition, example, and a picture. Some entries, such as the entry for kangaroo, also contain a video and hyperlinks to other entries (in this case, to the word marsupial). The headword and pronunciation are placed in the first line. Each headword has its own entry. The headwords with spelling variations, i.e. bickies/bikkies and big/small bickies/ bikkies, as well as EFTPOS/ eftpos, are presented in the same entry. The pronunciation is given in IPA characters and audio files that use either a male or female voice with an Australian accent. Therefore, users who cannot read IPA characters can listen to the pronunciation from the audio file.

The second line consists of the grammatical information and usage note. As shown in Figure 2, the grammatical information is not abbreviated (for example, C or U/NC), but spelled out (i.e. 'countable noun') to make it easier for users to understand. The usage notes are included so that dictionary users are aware of the register of each term, and of occasions for its use. Common terms like the Ashes (relating to cricket) are marked 'This is the usual term used by all speakers'. More restricted forms are marked 'This term is used by many speakers' (e.g. barrack for); 'This term is used by some speakers' (e.g. arvo); 'This term is used by some speakers, often in the older age groups' (e.g. sanga); or 'This term is used by some speakers, often from the younger age groups' (e.g. What's up?). Common words such as Aussie, which are not official terms but are frequently used, are marked 'This term is used by speakers of all ages'. Special circumstances are noted, such as 'This term is used by many people when writing an invitation' (e.g. bbq, byo).

The definitions present an initial phrase followed by an explanatory sentence where necessary. As explained previously, the definitions are written using a limited defining vocabulary to make it easier for the users to comprehend them. Hyperlinks to other entries in the ACD are also provided. After the definition, there is an example sentence. Example sentences were taken wherever possible from the Australian version of the VOLE (Varieties of Learner English) corpus in Sketch Engine. Where words did not appear in the VOLE corpus, an Australian Internet search was conducted to find suitable examples. All example sentences were chosen because they not only show the word in use in a sentence but also add a dimension of understanding to the term. As in LDOCE (2003), words used in the example sentences are not restricted to the defining vocabulary, as to do so would have placed unnatural limits on the examples and excluded the use of most of the authentic corpus illustrations.

All entries include a photograph. Although there is debate in the literature about the use of photographs rather than drawings (Szczepaniak and Lew 2011: 330), it was more economical for us to take our own photographs or to buy stock photographs, rather than to commission drawings from an artist. Videos are also provided in those cases where a moving image would add useful information to an entry. For example, a video of a kangaroo jumping provides a vivid demonstration of its distinctive motion which it is hard to capture in words or even in a photograph. The number of videos was also restricted due to time limitations in filming and editing.

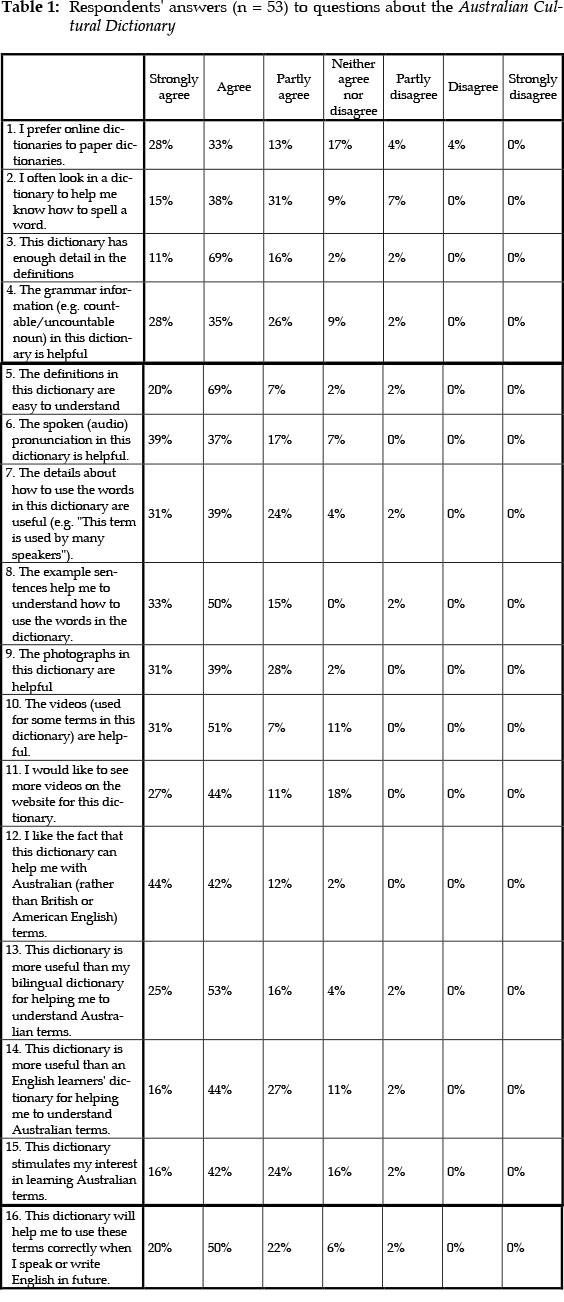

Evaluation and discussion

Two consecutive new cohorts of PEP students were informed of the ACD website in 2015, and a notice was put on the dictionary's homepage inviting participants to complete an online evaluation in return for a $10 book voucher. By the end of November 2015 there were 53 responses in total (55% male; 45% female). Most respondents (89%) were aged between 20 and 39 and all came from non-English speaking countries, with nearly three quarters (74%) from China. All but one of the respondents were living in Australia at the time of undertaking the survey. The survey asked detailed questions about the dictionary website (see Table 1 for questions and responses). In addition, there were two open-ended questions asking about the best features of the dictionary and suggestions for improvement (summarised in Table 2).

The percentages below, based on the data in Table 1, mainly refer to the total number of respondents who agreed or strongly agreed with a statement.

With regard to general dictionary use, fewer students than expected (61%) preferred online to paper dictionaries. There were also only 53% who used a dictionary to check spelling (although this figure is much higher than Harvey and Yuill's (1997: 259) finding of 24%).

The restricted DV was obviously effective, as 89% of users found the definitions easy to understand. Most of them (80%) also agreed that the ACD provides enough detail in its definitions. Grammatical information was useful for 64% of respondents, indicating that users do actually use (or claim to use) this information (cf. Bogaards 2001). The audio pronunciation was well received (76%), and 70% found the usage information helpful. Example sentences were also thought to be beneficial (83%). Both photographs and videos were considered helpful, but the videos were appreciated more than the photographs (i.e. 82% for videos and 70% for photographs). In addition, 71% requested more videos in a future edition.

Participants particularly liked the Australian focus (86%), and 78% found the ACD more useful than their usual bilingual dictionary for understanding Australian terms. However, only 60% found it more useful than their English learner's dictionary. Nevertheless, only 28 of our terms appeared in all the Big 6, and 31 terms were not in any of the Big 6.

More than half the respondents (56%) said the dictionary stimulated their interest in learning Australian terms. This shows that the ACD could be used as a tool to introduce EAL learners to Australian terms and to encourage better understanding of Australian culture.

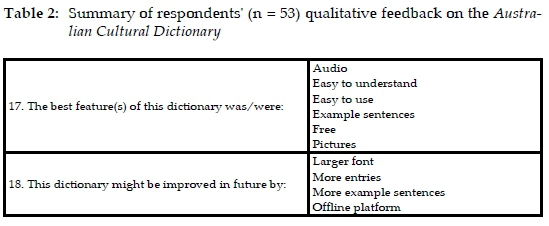

Answers to the open ended questions suggested that participants appreciated the fact that the dictionary was free, easy to use and easy to understand. They also particularly liked the audio files and pictures. For the further development of the ACD, they wanted more entries and more example sentences, and would have liked offline availability and a larger font. At the moment, the default font type and size of the definition in the ACD is Verdana 10.5, which is actually similar to the font size of the other online learner's dictionaries. In addition, users can use the Ctrl + buttons on their keyboard if they want a larger font size.

Conclusion

The ACD was an experiment in creating a specialized dictionary to meet a perceived need. Its reception indicates that the need was largely met, particularly in relation to the dictionary's Australian focus, its use of videos and spoken pronunciation, its example sentences and the clarity of its definitions. Useful information was also gained about certain dictionary use habits, the main findings here being that only 61% of participants preferred online to paper dictionaries and 53% of participants used dictionaries to help with spelling.

The data indicate that students do indeed appreciate cultural information in a dictionary, and that this need may not be met in current learner's dictionaries or bilingual dictionaries, particularly if the target culture is not that of the UK or the US. It is therefore suggested that the current ACD be expanded by using words found in the indices of books on Australian culture or by collecting additional data using the method explained in this article. We also suggest that similar dictionaries be created for other varieties of English and for other languages.

References

Atkins, B.T.S. and M. Rundell. 2008. The Oxford Guide to Practical Lexicography. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Béjoint, H. 2011. Review of Patrick J. Cummings and Hans-Georg Wolf: A Dictionary of Hong Kong English. Words from the Fragrant Harbour. International Journal of Lexicography 24(4): 476-480.

Bogaards, P. 2001. The Use of Grammatical Information in Learners' Dictionaries. International Journal of Lexicography 14(2): 97-121. [ Links ]

Bolaffi, G., R. Bracalenti, P. Braham and S. Gindro (Eds.). 2003. Dictionary of Race, Ethnicity and Culture. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Browne, C., B. Culligan and J. Phillips. 2013. A New General Service List (1.01). Available: http://www.newgeneralservicelist.org/ [17 December 2014].

Butler, S. (Ed.). 2013. Macquarie Dictionary. Sixth edition. Sydney: Pan Macmillan Australia. [ Links ]

Chun, D.M. and J.L. Plass. 1996. Effects of Multimedia Annotations on Vocabulary Acquisition. The Modern Language Journal 80(2): 183-198. [ Links ]

Cowie, A.P. 1999. English Dictionaries for Foreign Learners: A History. Oxford: Oxford University Press/Clarendon Press. [ Links ]

Coxhead, A.J. 1998. An Academic Word List (English Language Institute Occasional Publication 18). Wellington, New Zealand: Victoria University of Wellington. [ Links ]

Delbridge, A. 1983. On National Variants of the English Dictionary. Hartmann, R.R.K. (Ed.). 1983. Lexicography: Principles and Practice: 23-40. London: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Dziemianko, A. 2006. User-friendliness of Verb Syntax in Pedagogical Dictionaries of English. Lexicographica Series Maior 130. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer. [ Links ]

Fraser, H. 1997. Dictionary Pronunciation Guides for English. International Journal of Lexicography 10(3): 181-208. [ Links ]

Gouws, R. 2011. Learning, Unlearning and Innovation in the Planning of Electronic Dictionaries. Fuertes-Olivera, P.A. and H. Bergenholtz (Eds.). 2011. e-Lexicography: The Internet, Digital Initiatives and Lexicography: 17-29. London/New York: Continuum. [ Links ]

Häcker, M. 2012. The Change from Respelling to IPA in English Dictionaries: Increase in Accuracy or Increase in Prescriptivism? Language and History 55(1): 47-62. [ Links ]

Harvey, K. and D. Yuill. 1997. A Study of the Use of a Monolingual Pedagogical Dictionary by Learners of English Engaged in Writing. Applied Linguistics 18(3): 253-278. [ Links ]

Heid, U. 2011. Electronic Dictionaries as Tools: Towards an Assessment of Usability. Fuertes-Olivera, P.A. and H. Bergenholtz (Eds.). 2011. e-Lexicography: The Internet, Digital Initiatives and Lexicography: 287-304. London/New York: Continuum. [ Links ]

Kipfer, B.A. 1984. Workbook on Lexicography: A Course for Dictionary Users with a Glossary of English Lexicographical Terms. Exeter Linguistic Studies 8. Exeter: University of Exeter. [ Links ]

Kwary, D. and J. Miller. 2013. A Model for an Online Australian English Cultural Dictionary Database. Terminology 19(2): 258-276. [ Links ]

Lew, R. 2011. Online Dictionaries of English. Fuertes-Olivera, P.A. and H. Bergenholtz (Eds.). 2011. e-Lexicography: The Internet, Digital Initiatives and Lexicography: 230-250. London/New York: Continuum. [ Links ]

Lew, R. 2015. Research into the Use of Online Dictionaries. International Journal of Lexicography 28(2): 232-253. [ Links ]

Lew, R. and G.-M. de Schryver. 2014. Dictionary Users in the Digital Revolution. International Journal of Lexicography 27(4): 341-359. [ Links ]

Lew, R. and A. Dziemianko. 2006. A New Type of Folk-inspired Definition in English Monolingual Learners' Dictionaries and its Usefulness for Conveying Syntactic Information. International Journal of Lexicography 19(3): 225-242. [ Links ]

Lynch, P.J. and S. Horton. 2008. Web Style Guide: Basic Design Principles for Creating Web Sites. New Haven/London: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Miller, J. 2011. Never Judge a Wolf by its Cover: An Investigation into the Relevance of Phrasemes included in Advanced Learners' Dictionaries for Learners of English as an Additional Language in Australia. Ph.D. Thesis. Adelaide, Australia: Flinders University. [ Links ]

Moore, B. (Ed.). 2016. The Australian National Dictionary. Second edition. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Ogilvie, S. 2011. Linguistics, Lexicography, and the Revitalization of Endangered Languages. International Journal of Lexicography 24(4): 389-404. [ Links ]

Peters, P. 2001. Corpus Evidence on Australian Style and Usage. Blair, D. and P. Collins (Eds.). 2001. English in Australia: 163-178. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Peters, P. 2007. Similes and Other Evaluative Idioms in Australian English. Skandera, P. (Ed.). 2007. Phraseology and Culture in English: 235-255. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Procter, P. et al. (Eds.). 1978. Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English. London/Harlow: Longman. [ Links ]

Rundell, M. (Ed.). 2002. Macmillan English Dictionary for Advanced Learners. Second edition. Oxford: Macmillan Education. (MEDAL) [ Links ]

Sinclair, J.M., P. Hanks, G. Fox, R. Moon and P. Stock (Eds.). 1987. Collins Cobuild English Language Dictionary. London/Glasgow: William Collins Sons & Co. [ Links ]

Sinclair, J. (Ed.). 2009. Collins Cobuild Advanced Dictionary of English. Boston, MA: Heinle Cengage Learning/Harper Collins Publishers. (COBUILD) [ Links ]

Summers, D. (Ed.). 2003. Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English. Fourth edition. Harlow, Essex: Pearson Education. (LDOCE) [ Links ]

Svensén, B. 2009. A Handbook of Lexicography. The Theory and Practice of Dictionary-making. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Szczepaniak, R. and R. Lew. 2011. The Role of Imagery in Dictionaries of Idioms. Applied Linguistics 32(3): 323-347. [ Links ]

The University of Adelaide. 2013. AdTAT: The Adelaide Text Analysis Tool. Available: http://www.adelaide.edu.au/red/adtat [17 December 2014].

Urban Dictionary. Available: http://www.urbandictionary.com/ [3 December 2015].

Walter, E. (Ed.). 2008. Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary. Third edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (CALD) [ Links ]

Wehmeier, S. (Ed.). 2010. Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary. Eighth edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (OALD) [ Links ]

West, M. (Ed.). 1953. A General Service List of English Words: With Semantic Frequencies and a Supplementary Word-List for the Writing of Popular Science and Technology. London/New York: Longmans/Green. [ Links ]

Xu, H. 2012. A Critique of the Controlled Defining Vocabulary in Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English. Lexikos 22: 367-381. [ Links ]

Zgusta, L. 2006. Lexicography Then and Now: Selected Essays. Edited by Dolezal, F.S.F. and T.B.I. Creamer. Lexicographica. Series Maior 129. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer. [ Links ]