Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Lexikos

versão On-line ISSN 2224-0039

versão impressa ISSN 1684-4904

Lexikos vol.27 Stellenbosch 2017

ARTICLES

Intellectualization through Terminology Development*

Intellektualisering deur terminologieontwikkeling

Langa Khumalo

Linguistics Program, School of Arts, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. (khumalol@ukzn.ac.za)

ABSTRACT

The term intellectualization was famously used in the Prague School to describe a process that a language undergoes in its development and refinement. In our South African context intellectualization entails a carefully planned process of hastening the cultivation and growth of indigenous official African languages so that they effectively function in all higher domains as languages of teaching and learning, research, science and technology. This article critically examines the terminology development process that is being driven at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (henceforth UKZN) as one of the key agents of language intellectualization. The article critically evaluates the UKZN terminology development model that is used to harvest, consult and authenticate isiZulu terminology for Administration, Architecture, Anatomy, Computer Science, Environmental Science, Law, Physics, Psychology, and Nursing disciplines. Outflow platforms for the terminology in this development model are loosely listed as the 'database' and the 'development platform' but there is no clear end-user platform for students and lecturers, who seem to be the main end-user-targets of the whole terminology development initiative. The article will propose an improved model to cater for AnyTime Access, which is convenient for student needs between lectures, and improve the harvesting mechanism in the existing model.

Keywords: intellectualization, terminology development, harvesting, crowdsourcing, consultation, verification, authentication, anytime access

OPSOMMING

Die term intellektualisering is oorspronklik deur die Praagse skool gebruik om 'n proses wat 'n taal tydens sy ontwikkeling en verfyning ondergaan te beskryf. in ons Suid-Afrikaanse konteks behels intellektualisering 'n sorgvuldig beplande proses om die ontwikkeling en groei van plaaslike amptelike Afrikatale te bespoedig sodat hulle effektief op alle hoëvlakterreine funksioneer as tale van onderrig en leer, navorsing, wetenskap en tegnologie. Hierdie artikel doen 'n kritiese ondersoek na die terminologieontwikkelingsproses wat by die Universiteit van KwaZulu-Natal (voortaan UKZN) bestuur word as een van die sleutelfigure van taalintellektualisering. UKZN se terminologieontwikkelingsmodel word gebruik om isiZulu-terminologie binne die dissiplines Administrasie, Argitektuur, Anatomie, Rekenaarwetenskap, Omgewingswetenskap, die Regte, Fisika, Sielkunde en Verpleegkunde te oes, te raadpleeg en te staaf. Die artikel evalueer hierdie model krities. Afvoerplatforms vir die terminologie in hierdie ontwikkelingsmodel word losweg gelys as die 'databasis' en die 'ontwikkelingsplatform', maar daar is geen duidelike eindgebruikerplatform vir studente en dosente nie, wat waarskynlik die belangrikste eindgebruikerteikengroep van die hele terminologie-ontwikkelingsinisiatief vorm. Die artikel stel 'n verbeterde model voor wat deurlopende toegang sal bied, wat gerieflik vir studente se behoeftes tussen lesings sal wees, en wat die oesmeganisme in die bestaande model sal verbeter. * This article was presented as a paper at the Twenty-first Annual International Conference of the African Association for Lexicography (AFRILEX), which was hosted by the Xitsonga and Sesotho sa Leboa National Lexicography Units, Tzaneen, South Africa, 4-6 July 2016.

Sleutelwoorde: intellektualisering, terminologieontwikkeling, oes, skaredeelname, konsultasie, verifikasie, stawing, deurlopende toegang

1. Introduction

It can be argued that South African Higher Education (henceforth SAHE) is increasingly embracing the imperative of transmuting African languages to be the kernel of the academy. This has been recently articulated in the #FeesMustFall initiative (cf. Chetty and Knaus 2016). Hitherto the dominant languages in SAHE have been English and Afrikaans. It has been persuasively argued that the high attrition rate in Africa's education system is in part due to the fact that Africa is uniquely one of the few continents where children receive education in foreign tongues (cf. Finlayson and Madiba 2002). It is in this vein that the UKZN language policy and plan (2006 revised 2014) recognizes the prominent role that language plays in the teaching and learning. Through its language policy and plan, UKZN has taken an initiative to cultivate, modernize and elaborate isiZulu so that it becomes a vehicle in knowledge production and knowledge dissemination. one of the stated aims of the UKZN language policy is to "achieve for isiZulu the institutional and academic status of English" and to "provide facilities to enable the use of isiZulu as a language of learning, instruction, research and administration" (Language Policy of the UKZN 2014: 2). It is in this regard that, while UKZN upholds the principle of multilingualism, English and isiZulu are the two official languages of the institution. It has thus been persuasively argued that in order for African languages to be used in education as languages of instruction, innovation, science, mathematics and logic, there has to be a clear, conscious and careful process of the intellectualization of these languages.

Through its language policy and plan, UKZN articulates a clear objective to remove language as a barrier of access and success. The notion of access and success is articulated in the 1994 UNESCO World Conference framework of action where the following was noted: that our education systems should

[...] accommodate all children regardless of their physical, intellectual, social, linguistic or other conditions. This should include disabled and gifted children, street and working children, children from remote or nomadic populations, children from linguistic, ethnic, or cultural minorities and children from other dis-advantaged or marginalized area and groups. (UNESCO, 1994, Framework for Action on Special Needs Education: 6)

SAHE is thus encouraged to:

[...] recognize and respond to the diverse needs of their students, accommodating both different styles of learning and ensuring quality education to all through appropriate curricula, organizational arrangements, teaching strategies, resource use and partnerships with their communities. (UNESCO, 1994, Framework for Action on Special Needs Education: 11-12)

Hence UKZN's strategy to cultivate isiZulu so that it becomes a language of administration and all academic activity in order to eliminate problems of language being a barrier to access and success. In order to achieve this, UKZN has committed huge financial and human resources. This article thus critically examines the UKZN's language program. The article locates terminology development as one of the ways through which the University seeks to intellectualize isiZulu. The article further evaluates the limitations of the University's current terminology development model, and proposes an improved model to cater for the novel notion of AnyTime Access that we motivate here in order to satisfy end-user-needs.

2. Intellectualization

Intellectualization is a term originally used by Havranek (1932), a linguist from the Prague School, to characterize a process that a language undergoes in its advancement.

By the intellectualization of the standard language, which we could also call its rationalization, we understand its adaptation to the goal of making possible precise and rigorous, if necessary abstract, statements, capable of expressing the continuity and complexity of thought, that is, to reinforce the intellectual side of speech. This intellectualization culminates in scientific (theoretical) speech, determined by the attempt to be as precise in expression as possible, to make statements which reflect the rigor of objective (scientific) thinking in which the terms approximate concepts and the sentences approximate logical judgements. (My emphasis). (Havránek 1932: 32-84)

Intellectualization thus is a clear process of (functionally) cultivating, developing, elaborating and modernizing a language so that the terminology of the language can carry the full weight of scientific rigor and precision, and that its sentences can accurately express logical judgements resulting in a language that has the capacity to function in all domains. As the direct consequence of intellectualization the speakers of the language derive the pride, self-assurance and resourcefulness in the (new) ability to discuss the most complex of issues ranging from the mundane to academic and beyond.

Intellectualization has been famously associated with the development of Tagalog in the Philippines. The cultivation process involved Tagalog's lexical enrichment through terminology to enable its use in academia. Philippine linguistics and sociolinguists are recognized by Neville Alexander in Busch, Busch and Press (2014) as the doyens in the scholarship of intellectualization. Sibayan (1999: 229) characterizes an intellectualized language as one:

[...] which can be used for educating a person in any field of knowledge from kindergarten to the university and beyond.

Thus, an intellectualized language has the capacity to discuss any issue regardless of its complexity. According to Finlayson and Madiba (2002: 53), in the South African context intellectualization is a meticulous procedure aimed at expediting the growth and development of hitherto underdeveloped African languages to augment their capacity to effectively interface with modern developments, theories and concepts. It is imperative to note that germane to this process is the development of discipline specific terminology. The paucity of such specialized terminology is often cited as the reason why African languages cannot be used as languages of teaching and learning, hence their discernment as shallow and inadequate (cf. Shizha 2012).

Intellectualization in our context thus means the radical transformation of the capacity and role of indigenous African languages in carrying and conveying all forms of knowledge in all spheres of life. While the government through the Constitution (1996, section 6) has expressed commitment "to elevate the status and advance the use of" these hitherto underdeveloped languages, very little has actually been done to improve their status and role in SAHE (cf. Olivier 2014). The argument on the status and role of these languages has been sharply brought back to the center of SAHE through the #FeesMustFall. Writing on the #FeesMustFall, Chetty and Knaus (2016) posit that at the center of the 2015 student protests was the disruption of the status quo with regards to "[...] institutions' language policies, high fees, structural inequalities and colonial symbols."

3. UKZN Language Program

UKZN has a University Language Board (henceforth ULB), which was set up through a committee charter (2006 amended 2010). The ULB meets quarterly and its mandate is to develop, implement, monitor and review the University Language Policy and Plan. The ULB is required to report to the University Senate once a year, and importantly its annual report to Senate must be in both English and isiZulu. It is chaired by a Deputy Vice-Chancellor (henceforth DVC), who is also a member of the University's Executive. As reiterated above, UKZN first adopted its Language Policy and Plan in 2006, which was subsequently revised in 2014 following the University's college reorganization and the introduction of the Use of Official Languages Act of 2012. In its strategy to institutionalize language planning and development, UKZN established the University Language Planning and Development Office (henceforth ULPDO), which is headed by a Director who is a member of the ULB, and reports to the DVC.

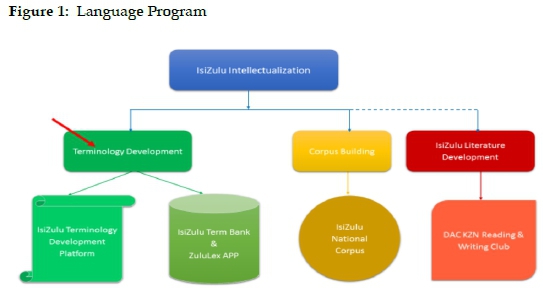

The program to intellectualize isiZulu so that it (ultimately) functions at par with English in all high function domains across the University is initiated by the ULPDO, and is reported quarterly at the ULB. The major thrust of the language program (see Fig. 1.) as approved by the ULB is the creation of discipline specific terminology in isiZulu, the building of an isiZulu National Corpus, and the development of a contemporary body of literature in isiZulu. Other language activities include the provision of training workshops, translation and (simultaneous) interpreting services, Sign Language advocacy, the Sesotho Bua Le Nna (Let's Talk) Program, language research, and the development of computational tools.

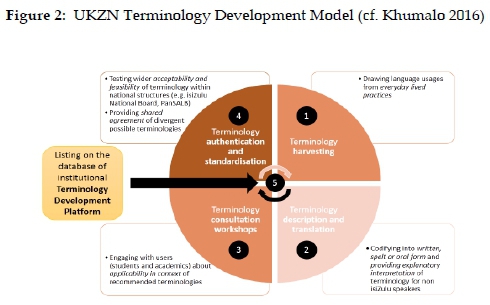

The article critically evaluates the UKZN terminology development model (see Fig. 2.) used to harvest, consult and authenticate isiZulu terminology for Administration, Architecture, Anatomy, Computer Science, Environmental Science, Law, Physics, Psychology, and Nursing to date. In this model, outflow platforms for the authenticated terminology are loosely indicated as the 'database' and 'development platform'. There is no clear end-user platform for students in the model, yet the students seem to be the main end-user-target of the whole terminology development initiative. Other important end-users are lecturers, teachers, lexicographers, educational interpreters and translators, isiZulu speakers, and authors. The article will propose an improved model to cater for AnyTime Access, which is convenient particularly for student needs between lectures, and propose an improved harvesting mechanism for the existing model. We critically examine the terminology development model in section 4, discuss in section 5 and conclude in section 6.

4. Terminology Development Model

UKZN has identified terminology development as one of the main cogs (together with corpus building and computer assisted language tools) to drive the goal of isiZulu intellectualization. One of the important principles in the development of specialized terminology at UKZN is to observe statutory mandatory processes. These processes are driven by the Pan South African Language Board (henceforth PanSALB), which is a Board constituted through an Act of Parliament. Through the provisions of the PanSALB Act 59, (1999), there exists an isiZulu National Language Body, UMZUKAZWE, which is short for UMkhandlu WesiZulu Kuzwelonke.

In light of these provisions, UKZN has designed a unique terminology development process with five important stages that incorporate the statutory processes facilitated by PanSALB through its KwaZulu-Natal Provincial office. There are five stages in the UKZN terminology development model and these include 1) harvesting of existing usage terms; 2) description and translation of terminology that has been harvested or created; 3) consultation and verification with end-users about terminology proposed, and 4) authentication and standardization through official national structures. The "finalization" of the process in the current model takes place in 5) through the listing of these terms on the terminology databases for wider institutional and national usage. The five stages are illustrated in Figure 2 below.

The current terminology development model as shown in Fig. 2 relies on the discipline lecturers, as experts in their fields, to initiate the harvesting of terms that are central to the module or course that they lecture in. While the UKZN language policy exists as an instrument that enables the development of teaching materials in both English and isiZulu, the enforcement of the policy is tepid, cautious and not compulsory. Hence harvesting is thus done voluntarily by discipline lecturers who are committed to the principles of the UKZN language policy, and also realize the value in making their teaching materials available to students in both languages. The harvested terms are a wordlist of key terms created from a main course/module or a major reference work. Because of the expenses involved in convening a single terminology development workshop (each workshop ca. R65 000-R95 000), the ULPDO has imposed a minimum requirement of at least 500 terms to be submitted for them to be taken through the development processes. Each workshop is a minimum of three days and can go up to five days depending on the complexity of the subject or discipline.

Once the terms are harvested and have been submitted to the ULPDO, the latter convenes a consultative workshop with a panel of at least two discipline experts, lexicographers, linguists, terminologists, and students of up to 25 individuals to describe, create and codify the isiZulu terms. This approach can be rightly criticized as top-down, elitist and exclusionary because it seems to target experts to the exclusion of general isiZulu speakers and other stakeholders who are outside the academe. A counter-argument is that terminology development is inherently a specialized task for people with certain levels of expertise for use by people working or training in a particular specialized discipline. A balance of the top-down and bottom-up approach is argued for in section 5 below.

Once the terms have been described and codified the ULPDO convenes a second workshop for the PanSALB subcommittee of isiZulu national language body to consider the terms. This is called the verification workshop. After the verification committee has thoroughly engaged academics and students in these often grueling verification workshops, the agreed terms are then submitted to the full isiZulu national language body (UMZUKAZWE) for authentication and standardization. The UMZUKAZWE is convened by the PanSALB regional office through the request of the ULPDO to consider and approve the consulted and verified terminology. Once the full UMZUKAZWE has approved the terms in the presence of the discipline experts, ULPDO notifies the ULB, and afterwards the terms are ready to be used in the lecture room and in formal academic discourses. In the current terminology development model the authenticated terms are stored in a database. It is crucial to observe that these workshops (consultative, verification and authentication) are arduous to both academics and students, and the members of each committee involved in the process. It is through sheer individual commitment and dedication by academics in each disciplines, and the members of the isiZulu language committees, that UKZN has completed in a narrow sense (given that terminology development is a continuous process) the terminology development processes in the following disciplines: Administration, Architecture, Anatomy, Computer Science, Environmental Science, Law, Nursing Science, Physics, Psychology, and Research.

The terminology development model is cyclical. Once a discipline has gone through all the processes, ULPDO moves on to the term list submitted by the next discipline experts and the process is repeated. It is clear that the process requires a huge investment both in terms of time and financial resources.

5. Discussion

In this section we critically evaluate the terminology development model. The current model relies on the discipline lecturers to initiate harvesting. This harvesting work is done over and above the discipline lecturer's other teaching, research, and administrative commitments. Those who have done so have demonstrated outstanding commitment. However the harvesting has become slow and erratic. This is attributable to the University's Teaching Workloads Framework (used to assess teaching) and Performance Measurers (used to assess research, among other things). According to the Teaching Workloads Framework the norm is that a lecturer must have at least 810 hours of teaching. The approved performance measures are 60 Productivity Units (henceforth PU) for lecturers, 90 PUs for senior lecturers, 120 PUs for associate professors and 150 PUs for professors per year. A single publication in a Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) approved journal carries 60 PUs. This means a lecturer has to publish at least a single journal article per annum, while a professor has to publish two and a half articles in the same period. There are indeed some lecturers who have abandoned terminology development for their disciplines citing huge workloads, while expressing the obvious need for isiZulu terminology as a useful intervention to improve conceptual and epistemic access.

To mitigate erratic terminology harvesting, and the effects of a clearly top-down and exclusionist approach to terminology development, ULPDO is introducing (computational) technology in term harvesting. Crowdsourcing has been advanced as a useful strategy to harness discipline specific terminology. This argument was advanced when ULPDO was developing isiZulu terminology in computer science. The two discipline experts, Dr Maria Keet and Dr Graham Barbour created a novel method (cf. http://www.commuterm.co.za/) of harnessing terms in computer science using computational resources (cf. Keet and Barbour 2014). This is a useful strategy to improve the collection of terminology, which can also be further extended to include online commentary in order to augment the role of the consultative workshop, with a view of replacing it in the long term in order to reduce costs.

The current UKZN terminology development model can be criticized for being a top-down approach to language planning. Language planning is often viewed as a top-down process, which is characterized by Cooper (1989: 45), and Grin (1996: 31) as a considered, planned, systematic effort to influence and affect the language behavior of a particular society through crafting and implementing regulations or policies, thus regulating a speech community's language behavior. According to Webb (2002: 42) for language planning to be effective, top-down processes need to be complemented by a bottom-up approach, which means that the interest, views, attitudes and linguistic competences of the targeted speech community must be accommodated.

In explicating the bottom-up approach, Kaplan and Baldauf (1997: 50), distinguish between activities of governments and agencies and activities of pressure groups and individuals in the language planning process (cf. Sithole 2017). According to these distinctions, a bottom-up approach to language planning refers to the language cultivation activities of individual and pressure group agencies. We argue in this article that a judicious mixture of the top-down and bottom-up approach may render a better outcome for the UKZN terminology development model.

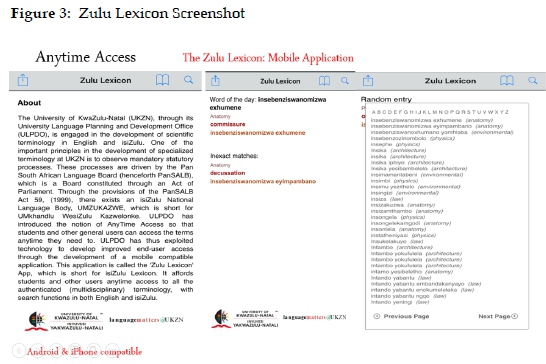

In order to also improve access to the authenticated and finalized terminology we propose a clearer end-user platform(s) for students, lecturers, teachers, lexicographers, educational interpreters and translators, and isiZulu speakers. Hitherto a lot of terminology has been developed by many universities in the country, the National Language Services in the Department of Arts and Culture (DAC), and the South Africa Norway Tertiary Education Development Program (SANTED) multilingual glossary project, among others. Terminology developed is stored away in some inaccessible databases without any dissemination strategy. ULPDO has developed two open-source platforms to cater for a broad-based end-user uptake of its authenticated terminology. ULPDO has also introduced the notion of AnyTime access so that students and other users can access the terms anytime they need them. ULPDO has exploited technology to develop improved end-user access through the development of a mobile compatible application. The application is called the Zulu Lexicon, which is short for isiZulu Lexicon, and is a free download from iTunes and Google Play in Smartphone and Android. The Zulu Lexicon affords students, lecturers, and other end-users anytime access at their fingertips to all the authenticated (multidisciplinary) terminology, with search functions on the APP in both English and isiZulu as shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3 shows the landing page for the Zulu Lexicon App (on the left hand side) the word-of-the-day in the discipline of anatomy in the middle, and the a-z lexicon with random entries under the letter I of the Roman alphabet (on the far right). The APP has other filters to make searching very easy, and user-friendly for users to find the kind of information they want.

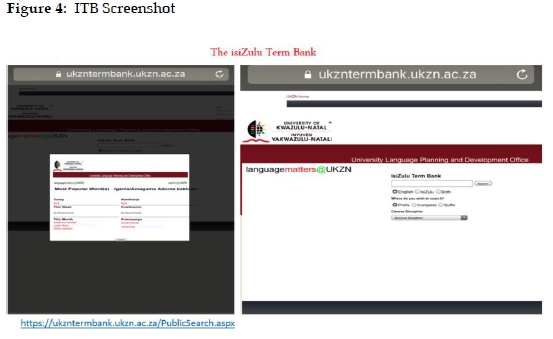

The second open source terminology resource is the isiZulu Term Bank. ULPDO developed the isiZulu Term Bank (ITB) as an open source database that is freely accessible on the following URL: https://ukzntermbank.ukzn.ac.za. It is a flexible system that can be incrementally populated with more authenticated terms for existing disciplines that are already in the database or with new disciplines whose terms have been developed and authenticated. Figure 4 below shows the ITB screenshot.

The left screen shows the landing page for the isiZulu Term Bank. The landing page will flash the most popular word of the day, week and month on the screen. The screen window is closed upon clicking the close button at the bottom of flashing page. On the right side of Fig. 4 is the screen showing the home page with easy to use functionalities. The end-user can search for a term by language (English or isiZulu), word structure (prefix, suffix or complete word) or by discipline, by following a drop down menu. The Zulu Lexicon APP and the isiZulu Term Bank are two open source technology platforms that the ULPDO has developed in order to effectively disseminate the authenticated isiZulu terminology that has been developed to date in the disciplines of Administration, Architecture, Anatomy, Computer Science, Environmental Science, Law, Physics, Psychology, and Nursing Science. As open source resources, the Zulu Lexicon application and the isiZulu Term Bank are freely available to students, lecturers, teachers, lexicographers, educational interpreters and translators, isiZulu speakers, and authors.

6. Conclusion

The article has argued that intellectualization is a gradual process, which culminates in a scientific language capable of reflecting the rigor of objective thinking. While the Constitution (1996) recognizes the importance of developing the official indigenous African languages, the imperative to cultivate them for higher level functions in order to improve access and success at higher education institutions in order to arrest rampant attrition rates has been brought sharply to the fore in the recent #FEESMUSTFALL initiative. SAHE is thus embracing the importance of bringing these hitherto marginalized languages at the very center of teaching and learning. This is arguably a very length process.

The article has argued that terminology development is one of the vital cogs in the intellectualization process. The paucity of terminology is often cited as the reason why African languages cannot contribute meaningfully to the knowledge economy, and this is articulated in Bamgbose (2002: 2), when citing lack of political will by those in authority as an impediment: "[...] They are quick to point out that African languages are not yet well developed to be used in certain domains or that the standard of education is likely to fall [...]." We thus argue in this article that terminology development should not be exclusively a top-down and selective process involving workshops often with a few discipline experts, terminologists, lexicographers and linguists, which is very resource intensive, but must embrace a bottom-up approach through crowd-sourcing (cf. Keet and Barbour 2014) in cases of terminology harvesting, including usurping certain functions of the consultative workshops in order to improve efficiency and reach, enhance acceptance, and preclude exclusion while cutting back on expenditure. Thus, the UKZN terminology development process must embrace a mixed approach in which the top-down and bottom-up approaches complement each other.

It is clear that stages 1 and 2 in the current ULPDO terminology development model (term harvesting and consultation workshops) can be enhanced using computational resources. It must be argued that the discipline expert knowledge is required consistently throughout the terminology development process. In order for these experts to be able to also participate in the online platforms (and at a later stage in verification and authentication workshops), a process must be initiated by the ULPDO to submit to the ULB and ultimately to Senate an argument to formally recognize participation in the terminology development within the Teaching and Workloads Framework. This will ensure that expert standards are retained, and rebut the argument that terminology development for African languages is an exercise in dumbing down education.

The strategy to improve access to multidisciplinary authenticated terminology using a novel mobile application the Zulu Lexicon and the isiZulu Term Bank introduces to the UKZN terminology development model new end-user platforms. The multidisciplinary terms are now available anytime to students, lecturers, teachers, lexicographers, educational interpreters and translators, isiZulu speakers, and authors.

References

Bamgbose, A. 2002. Launch of the Activities of the African Academy of Languages: Mission and Vision of the ACALAN. ACALAN Special Bulletin 2002: 24-25. [ Links ]

Chetty, R. and C.B. Knaus.2016. #FeesMustFall: SA's Universities are in the Grip of a Class Struggle. Mail&Guardian, 14 January 2016. Accessed on 31 July 2016.

Cooper, R.L. 1989. Language Planning and Social Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Finlayson, R. and M. Madiba. 2002. The Intellectualization of the Indigenous Languages of South Africa: Challenges and Prospects. Current Issues in Language Planning 3(1): 40-61. [ Links ]

Grin, F. 1996. The Economics of Language: Survey, Assessment, and Prospects. Grin, F. (Ed.). 1996. Economic Approaches to Language and Language Planning. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 121: 17-44. [ Links ]

Havranek, B. 1932. The Functions of Literary Language and its Cultivation. Havranek, B and M. Weingart (Eds.). 1932. A Prague School Reader on Esthetics, Literary Structure and Style: 32-84. Prague: Melantrich. [ Links ]

Kaplan, R.B. and R.B. Baldauf. 1997. Language Planning from Practice to Theory. Clevedon: Multi-lingual Matters. [ Links ]

Keet, C.M. and G. Barbour. 2014. Limitations of Regular Terminology Development Practices: The Case of isiZulu Computing Terminology. Alternation: Special Edition 12: 13-48. [ Links ]

Khumalo, L. 2016. Disrupting Language Hegemony: Intellectualizing African Languages. Samuel, M., R. Dhunpath and N. Amin (Eds.). 2016. Disrupting Higher Education Curriculum. Undoing Cognitive Damage: 247-264. Rotterdam/Boston/Taipei: Sense Publishers. [ Links ]

Olivier, J. 2014. Compulsory African Languages in Tertiary Education: Prejudices from News Website Commentary. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 32(4): 483-498. [ Links ]

Shizha, E. 2012. Reclaiming and Re-visioning Indigenous Voices: The Case of the Language of Instruction in Science Education in Zimbabwean Primary Schools. Literacy Information and Computer Education Journal (LICEJ), Special Issue 1(1): 785-793. [ Links ]

Sithole, E. 2017. From Dialect to 'Official' Language: Towards the Intellectualization of Ndau in Zimbabwe. Unpublished D.Phil. Thesis. Grahamstown: Rhodes University. [ Links ]

UNESCO. 1994. The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education. Paris: UNESCO. [ Links ]

Webb, V.N. 2002. Language in South Africa: The Role of Language in National Transformation, Reconstruction and Development. Amsterdam/Philadelphia, Penn: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

* This article was presented as a paper at the Twenty-first Annual International Conference of the African Association for Lexicography (AFRILEX), which was hosted by the Xitsonga and Sesotho sa Leboa National Lexicography Units, Tzaneen, South Africa, 4-6 July 2016.