Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Lexikos

versión On-line ISSN 2224-0039

versión impresa ISSN 1684-4904

Lexikos vol.27 Stellenbosch 2017

ARTICLES

Polyseme Selection, Lemma Selection and Article Selection

Poliseemseleksie, lemmaseleksie en artikelseleksie

Henning BergenholtzI; Rufus H. GouwsII

ICentre for Lexicography, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark and Department of Afrikaans and Dutch, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa (hb@bcom.au.dk)

IIDepartment of Afrikaans and Dutch, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa (rhg@sun.ac.za)

ABSTRACT

In linguistics, more specifically in the field of lexical semantics, a lot of attention has been given to polysemy and homonymy. The identification of and distinction between polysemy and homonymy should not be regarded as unproblematic. The lexicographic practice has traditional ways of presenting and treating polysemy and homonymy. This paper focuses on approaches in both linguistics and lexicography to polysemy and homonymy. Examples from the lexicographic practice are given. It is then shown that that the traditional lexicographic presentation and treatment of homonymy and polysemy in dictionaries with a text reception function, does not really assist the users adequately in their search to find the appropriate meaning of an unfamiliar linguistic expression. It is shown that different dictionaries often have the same lemma selection but not the same selection of polysemes. It is important that a dictionary should correctly coordinate a meaning and a specific linguistic expression. Consequently, a new approach is suggested for the presentation and treatment of homonymy and polysemy. Negotiating criticism expressed in both linguistics and lexicography, it is proposed that the lexicographic practice, in the case of dictionaries for text reception, should abolish the traditional distinction between homonyms as well as the presentation of the different senses of a polysemous word in a single article. Each meaning, whether the only meaning of a lexical item or one of any number of different senses, should be the only item giving the meaning in an article.

Keywords: article selection, dictionary user, homonymy, lemma selection, lexicography, linguistics, meaning, polyseme selection, polysemy, text production, text reception

OPSOMMING

In die taalkunde en meer spesifiek die leksikale semantiek het polisemie en homonimie reeds heelwat aandag gekry. Die vasstelling van asook onderskeid tussen polisemie en homonimie is nie onproblematies nie. In die leksikografiese praktyk is daar tradisionele maniere waarop polisemie en homonimie aangebied en bewerk word. Hierdie artikel wys op benaderings in sowel die taalkunde as die leksikografie tot homonimie en polisemie. Voorbeelde uit die leksikografiese praktyk word aangebied. Daarna toon hierdie artikel aan dat die tradisionele aanbieding en bewerking van polisemie en homonimie in woordeboeke met teksbegrip as funksie nie werklik die teikengebruiker help in sy/haar soektog na die verklaring van betekenis van 'n onbekende leksikale item nie. Daar word aangetoon dat verskillende woordeboeke dikwels dieselfde lemmakeuse het maar nie dieselfde poliseeemkeuse nie. Dit is belangrik dat 'n woordeboek die korrekte koördinasie van 'n uitdrukking en sy betekenis moet bied. Gevolglik word 'n nuwe benadering in hierdie artikel voorgestel. Na aanleiding van kritiek uit sowel die taalkunde as die leksikografie word voorgestel dat daar in die leksikografiese praktyk, in die geval van woordeboeke vir teksbegrip, afstand gedoen word van die tradisionele onderskeid tussen verskillende homonieme asook van die aanbieding van verskillende polisemiese waardes van 'n woord in een artikel. Elke betekeniswaarde, hetsy die enigste betekenis van 'n uitdrukking hetsy 'n polisemiese waarde, moet die enigste aanduider van betekenis in 'n artikel wees. Daar word geargumenteer ten gunste van 'n fokus op artikelkeuse met lemmakeuse en poliseemkeuse as onderafdelings.

Sleutelwoorde: artikelkeuse, betekenis, homonimie, leksikografie, lemmakeuse, poliseemkeuse, polisemie, taalkunde, teksbegrip, teksproduksie, woordeboekgebruiker

1. Introduction

In the treatment of lexical meaning in dictionaries lexicographers often adhere to a distinction between homonymy and polysemy, originating from the field of linguistics. This has a direct influence on the ordering and presentation of items giving the meaning of expressions in these dictionaries - irrespective of whether this expression is a single word, a multiword item, e.g. a fixed expression or a loan word combination, or a lexical item smaller than a word, e.g. a stem or an affix. The user is confronted by a lexicographic tradition according to which homonyms, that is lexical items with identical form but unrelated meanings, are entered as separate lemmas. Polysemy, where a single lexical item has different related senses, is treated by including all the senses in a single dictionary article with that lexical item as the lemma.

In a dictionary that has to satisfy a communicative function, the question arises whether adherence to the traditional treatment and presentation of homonymy and polysemy has any significance for the intended target user. This question will be addressed in the present paper. The emphasis will be on dictionaries used for text reception purposes but suggestions made in this paper may also be relevant to the other communicative functions, such as text production and translation.

2. Homonymy and polysemy

In the field of linguistics homonymy and polysemy are regarded as determining two different types of lexical ambiguity, cf. Lyons (1977: 550). In the study of lexical semantics and the presentation and treatment of lexical meaning in dictionaries both linguists and lexicographers have shown significant interest in polysemy and homonymy, cf. in this regard among others Zgusta (1971), Lyons (1977), Jeffery (1982), Stock (1984), Geeraerts (1986; 2013), Gouws (1983; 1989) and more recently Bergenholtz and Agerbo (2014a, b, c). In linguistics and lexicography homonymy is usually regarded as two or more lexical items with the same form but synchronically unrelated meanings, e.g. gum (=secretion of some shrubs and trees) and gum (=flesh around roots of the teeth), whereas polysemy is seen as the different related meanings (or senses) of a single lexical item, e.g. fence (= a barrier or railing ... enclosing an area of ground // a large upright obstacle in ... showjumping // a guard ... in machinery) (The Concise Oxford Dictionary).

In their dictionaries lexicographers frequently adhere to the distinction between homonymy and polysemy. Homonyms are presented as separate lemmas, each with a distinguishing homonym marker (gum1and gum2) whereas the different senses of a polysemous lexical item, also referred to in this paper as different polysemes1, are presented in a single article:

fence ...1. ...

2. ...

3. ...

From a linguistic point of view valid criticism against a too easy classification of words as being homonyms has been expressed by Lyons (1977: 550-569). Lyons indicates typical criteria introduced by linguists to distinguish between polysemy and homonymy. One such a criterion is the lexicographer's knowledge of the historical derivation of words. Homonyms are regarded as having developed from formally distinct lexical items. Lyons shows that the etymological criterion is not always decisive, among others because the historical derivation is not always certain. In addition, Lyons regards information about the origin of words as often irrelevant in the synchronic analysis of language.

A second criterion to which Lyons (1977: 551) refers and that is often used by linguists in distinguishing between polysemy and homonymy is relatedness versus unrelatedness of meaning. Lyons shows that there are problems in using this criterion of relatedness, e.g. the fact that relatedness of meaning can be regarded as a matter of degree. In this regard the intuition of native speakers may not be sufficient for a distinction between polysemy and homonymy.

Formal identity is a further criterion in the definition of homonymy (Lyons 1977: 557). This identity regards the phonological and the orthographic presentation of lexical items. He clearly argues that the condition of formal identity is not strong enough. Turning to lexicography Lyons (1977: 565) indicates that in traditional lexicographic practice a comparatively weak notion of syntactic identity is used when deciding whether two words are homonyms. Lyons (1977: 567) regards polysemy, a product of metaphorical creativity, as essential in the functioning of language whilst homonymy is not essential. Some of the suggestions Lyons makes to circumvent the problems of distinguishing between polysemy and homonymy will be discussed in a following section of this article. Important here is his critical approach to the traditional distinctions between polysemy and homonymy.

Although seen as two types of ambiguity the traditional distinction between homonymy and polysemy is not always unambiguous - in terms of an Old Danish fixed expression it is an elastic tape measure. Lexicographers do not all agree on distinguishing criteria for polysemy and homonymy. Wahrig (1973) rejected meaning as a distinguishing criterion between polysemy and homonymy in favour of a more unambiguous grammatical criterion. For him homonymy prevails when one and the same orthographic word is used for different lexical words with the same word class, or when within the same word class different inflection paradigms occur. Although such an approach to homonymy might be clearer and can perhaps be employed in a less ambiguous way its lexicographic application can often lead to a collection of different meanings in a single dictionary article of a given word. Bergenholtz and Agerbo (2014c) not only question the criteria to distinguish between polysemy and homonymy but also the actual existence of homonymy and polysemy, albeit that their proposals maintain a traditional lexicographic presentation and treatment of homonymy and polysemy - because such a model "is closer to the solution that dictionary users are familiar with". Whether such an approach is convincing remains to be seen.

In this paper the existence of homonymy and polysemy as concepts in the field of linguistics is acknowledged. The assumption is also that the polysemy of a lexical item prevails when the meaning of that word is assessed in isolation. As soon as a word is introduced to actual language use, the context activates a single sense and the other senses disappear for that context. With the exception of intended or unintended ambiguity a word in any given context has only one meaning.

3. Lexical meaning and contextual meaning

Can a lexical word that is characterised by a specific content connected to a specific expression have more than one meaning? In this paper we will argue against such an approach. Many linguists and lexicographers would have a different opinion. Their question would rather be: How many meanings can a word have? This is for example seen in the title of the contribution of Louw (1995). Louw adheres to a traditional approach that distinguishes between contextual and lexical meaning and he only regards the latter type as relevant to lexicography and should therefore be accounted for in dictionaries. Louw (1995) argues rightly that only the meaning of a word should be presented in dictionaries. The different uses of a given word should not be elevated to and presented as the meaning of the word. Louw argues against an inflation of polysemous senses that do not represent the meaning of the word but merely its use. According to Louw such a distinction between meaning and use, more precisely between lexical and contextual meaning, makes it possible to reduce the number of meanings, i.e. polysemous senses, of a given word. Louw regards such a reduction as helpful because a long list of polysemous senses can easily lead to dictionaries that lack user-friendliness. Louw argues against dictionaries that present the uses of a word as its different meanings:

They define usage rather than lexical meaning. ... It is of the utmost importance to distinguish lexical meaning from contextual meaning. ... However, if we fail to distinguish lexical meaning from contextual meaning we are bound to accept that whenever a word is used, a meaning comes from that usage. (Louw 1995: 358f)

This paper does not try to contradict Louw's distinction between contextual and lexical meaning or to argue against his approach that the use of a word should not be regarded as its meaning. This paper merely responds to Louw's question, i.e. "How many meanings can a word have?" It will be shown that the number of meanings of a word should not influence the way in which that word and those meanings are presented and treated in a dictionary.

Linguists do not agree on the nature and extent of polysemy. An approach that differs significantly from that of Louw (1995) is found in Panman (1982) who does not acknowledge the occurrence of either homonymy or polysemy in the case of lexical words. According to Panman homonymy and polysemy only prevail between words in context:

The present study argues that it is preferable to regard the phenomena as relations between word-tokens rather than between lexical items. (Panman 1982: 105)

An even more radical approach is found in Hanks (2000) and Hanks and Bradbury (2013). The latter contribution starts with the leading question: "Do words have meaning?" and the answer that is provided is a clear "No". Seemingly in contrast to Louw (1995) and more in agreement with Panman (1982) the basic assumption in Hanks and Bradbury is that a word only has meaning and can only have a meaning in a concrete context. According to Hanks and Bradbury (2013: 28) one cannot give a meaning to a lexical word in an isolated abstract construction.

This article maintains that scholars like Louw, Panman and Hanks and Bradbury primarily argue as linguists and not as lexicographers. A lexicographer is interested in the information needs and reference skills of the potential target user of a given dictionary. Whether a specific item in a dictionary can be regarded according to one or more linguistic theories as real meaning or not is not a question that has relevance for the user of the dictionary. A dictionary user needs help, and a lexicographer wants to provide help. Lexicographers achieve this by making a tool, a dictionary, available to the users. The potential dictionary user may for example not understand a word he or she reads in a text and then consults a dictionary for assistance to obtain an explanation of the meaning of the given word. Such items giving the meaning can be presented in different ways in different dictionaries, also because these dictionaries may differ with regard to their user types and may have fundamentally different usage situations. This contribution will primarily be concerned with the communicative situation where a mother-tongue speaker or a foreign language speaker encounters text reception problems.

In this article the authors do not try to show how an ideal item giving the meaning in a cognitive dictionary should look in a case of a dictionary that would like to inform as broadly as possible on the meaning of a word and how this meaning or these meanings can be related historically or systematically to other meanings. This is the topic in papers like that of Halas (2016) that concludes with a proposal for a comprehensive systematic presentation. Halas discusses the English verb drop of which the treatment contains six main meanings and twenty four submeanings or submeanings of a submeaning. In comparison to her breakdown of the meaning of this word the divisions within Wittgenstein's "Tractatus" look relatively simple! The practical value of this work is not easily detectable. The approach in this paper is that such minuscule divisions do not have a place in the lexicographic practice. To determine systematic knowledge about the word, this breakdown is so opaque that users will have extreme difficulties to obtain a clear overview of the coherence. The current paper rather looks at the lexicographic practice, especially in dictionaries for text reception, and at alternative ways in which meanings can be linked to expressions.

4. Polysemy in the lexicographic practice

Publications dealing with polysemy often use a single example or very few examples, often with a strong focus on verbs, cf. Louw (1995) and Halas (2016). Verbs frequently have numerous different uses and these uses, as indicated by Louw (1995), are listed in dictionary articles as senses to illustrate an apparent high occurrence of polysemy. The current paper also employs only a few examples but they are taken from different Danish as well as English dictionaries and the chosen lemmas are nouns and not verbs. The expressions represented by these lemmas are to a far lesser degree prone to a situation where the use of a word can be elevated to its meaning.

4.1 Polysemy in three Danish dictionaries

The following section contains a comparison of the selection of polysemes in three recent Danish monolingual dictionaries. Two of these dictionaries are polyfunctional. They strive to supply the user with assistance to solve information problems in different situations, e.g. with regard to text reception, text production and knowledge about words in the Danish language. This paper only focuses on the selection of polysemes from the perspective of text reception problems where only the item giving the meaning is of importance. Text reception is the only function of the third dictionary that has mother-tongue speakers of Danish with a reception problem as target user group. Monofunctional dictionaries like this one are very helpful as online products but also in the printed format. The first printed Danish dictionary was such a monofunc-tional dictionary (although there had been an earlier printing of the first volumes of a Danish dictionary that was never completed). This monofunctional dictionary (Leth 1800) was compiled for young people who did not understand all the expressions in the religious texts they read. Yet the majority of Danish dictionaries since then have been polyfunctional, e.g. the Politikens Nudansk Ordbog (2005) and Den Danske Ordbog (2017), in contrast to the monofunctional Den Danske Betydningsordbog (2017). These three dictionaries do not display the same lemma selection and number of lemmas.

- NUD (Politikens Nudansk Ordbog 2005) has more or less 47 000 lemmas

- DDO (Den Danske Ordbog 2017) has 98 639 lemmas

- DDB (Den Danske Betydningsordbog 2017) has 118 212 lemmas

The comparison of the polyseme selection in these three dictionaries is done by means of a limited number of lemmas. These lemmas, as is the case in the discussion of English dictionaries in paragraph 4.2, come from the article stretches of the letters s and t. Although the problem of text reception is only discussed in more detail with regard to the first example, i.e. the lemma stjernekigger (= stargazer), a comparable approach was followed for the other examples but due to space restrictions the results have not been presented here. A question to be answered is what the meaning of stjernekigger is in the following sentences obtained from a Google search on 6 February 2017:

(1) Hun ser sød ud, men hvis denne lille pige var en stjernekigger under fødslen, så har hun uden tvivl været noget af en udfordring for moderen. (= She looks sweet but if this little girl had really been a stargazer during her birth, she would undoubtedly have been a challenge to her mother.)

(2) Stjernekiggere og romantikere har gode chancer for at se stjerneskud, når stjerneskudssværmen Geminiderne er aktiv i perioden 4.-17. december. (= Stargazers and romanticists have good chances of seeing a shooting star when the swarm of shooting stars are active in the period between 4 and 17 December.)

(3) Araberen, som den redhårede pige red, var en typisk stjernekigger, som styrtede af sted med hovedet lige i vejret. (= The Arab on which the red-haired girl was riding was a typical stargazer, running to the front with its head lifted up.)

(4) Den hvidkantede stjernekigger er svær at få øje på, når den har gravet sig ned i havbunden. Selv kan den nemt se de småfisk og skaldyr, der er så uheldige at svømme forbi dens vagtsomme blik. (The stargazer with white edges is difficult to find when it has buried itself in the sea sand. It can easily see small fish and seafood that has the bad luck to swim directly into its watchful sight.)

(5) Stjernerne skaber opmærksomhed og tiltrækker en masse stjernekiggere, der håber at se en kendis på den røde løber. (The stars draw the attention and draw many stargazers to their close proximity, who hope to see a famous actor on the red carpet.)

The three dictionaries display the following polyseme selection for stjernekigger (= stargazer):

The NUD does not have this lemma.

The DDO includes this lemma and presents two polysemes:2

1. person that loves stars or likes to look at stars as a hobby, often with binoculars or a telescope.

2. child that is born with his face looking upwards and with the neck bent to the back.

The DDB has five polysemes:

1. person interested in stars and other celestial bodies and who observes them through appropriate binoculars; as well as professional astronomers and amateur astronomers.

2. baby that has turned at birth with his face to the top or not towards the womb of his mother that could cause difficulties during the birth because in this position the head cannot easily move through the pelvis of the mother.

3. horse that has a bad posture or has been trained incorrectly and has its head raised when being ridden.

4. person who goes to places where famous people are in order to see them and perhaps have contact with them.

5. family of fish with a typical appearance with the eyes on top of the head and with a big mouth directed upwards.

The more lemmas and the more polysemes a dictionary has, the better are the chances that a user with a text reception need will find the required assistance. NUD does not include the lemma stjernekigger at all and can therefore not be of real assistance. DDO has two polysemes, helping with examples (1) and (2) but not with the other three examples. The DDB includes the lemma and the polysemes that can explain all the different examples.

Already in this first example we can notice the tendency that is confirmed by the other examples: The bigger the lemma selection, the bigger the polyseme selection. This is interesting because one could have expected that dictionaries with fewer lemmas would present the most frequently used lemmas and their different meanings. Naturally, when saying this one has to negotiate the type of dictionary from which the lemmas have been selected but comparable dictionaries have been used for the selection of lemmas to be discussed in this section.

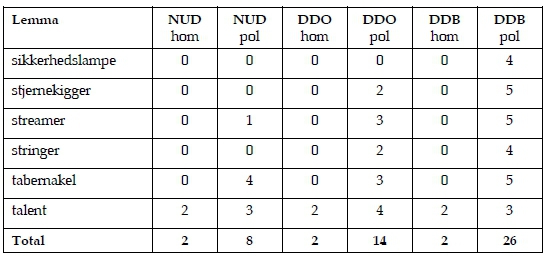

The following results can be obtained from the treatment of homonymy and polysemy with regard to the selected lemmas in the three dictionaries:

Sikkerhedslampe (safety lamp) only appears in one of the three dictionaries - the DDB that presents the following meanings:

1. lamp that burns with petroleum or another kind of inflammable liquid and of which the flame is protected in such a way that it cannot cause a fire, explosion or something similar in a mine.

2. lamp that hangs on a wall and lightens the environment when it registers a movement.

3. small lamp that a person carries or attaches somewhere, that flashes continuously or shines constantly so that other people can see an oncoming person or object, e.g. someone jogging in the dark.

4. lamp that is part of a security facility and that shines when the alarm is activated.

The word sikkerhedslampe (safety lamp) always refers to something regarding a lamp and security, but this is clear to anyone who speaks Danish. But he/ she does not actually know exactly for what a security lamp is used in a specific instance and how it functions. This is only clear from a polyseme selection with different items giving the meaning as in the dictionary referred to above.

The lemma streamer (streamer) has been included in all three these dictionaries.

The NUD does not have different polysemes for the lemma but only the following single meaning:

a sticker that is used as advertisement for a company or a product and e.g. affixed to the back window of a car.

The DDO has three polysemes:

1. longish sticker with a radiant promotional text, often affixed to the inside of the back window of a car.

2. headline in a newspaper, written in capitals.

3. an artificial fly for fly fishing, often coloured silver or gold, with wings made of feathers or hair to imitate prey species of the fish.

The DDB has five polysemes:

1. longish poster to be affixed, especially on glass panes and car windows.

2. device that one can use, for different types of acoustic devices, e.g. cellular phone, computer or music device, so that the sound can be transferred directly without the use of a cable.

3. person or company that produces radio, music or films that are not transmitted by means of normal media but can be seen or heard in the Internet.

4. fly for fly fishing, consisting of a tiny hard core with a long tail of hair or feathers, to lure fish like trout by imitating small prey species when being moved through the water or on the surface of the water.

5. long cable pulled behind a boat that investigates the bottom of the sea, while powerful sound waves are transmitted that are reflected from the bottom of the sea and are registered by the cable when the reflecting wave reaches the surface of the water.

The lemma stringer (stringer) is not found in the NUD but has been included in both the other dictionaries.

The DDO has two polysemes:

1. journalist or other person providing information, often from abroad, without being fully employed, with the information used by one or more editorial desks as alternative source to their own correspondents.

2. long buttresses in the body of a boat or airplane.

The DDB has four polysemes:

1 beams on the long side of a ship or airplane to support the body and make it more stable.

2 journalist that does not work for a specific newspaper or medium but provides contributions for different media on a specific topic, often because he is abroad and reports on local matters.

3 cord through the mouth and gills of a fish that has been caught by a fisherman or diver, or must be held briefly before being set free again.

4 T-shirt or vest without sleeves but only thin straps over the shoulders that gives the user freedom of movement when used during training.

All three dictionaries include the lemma tabernakel (tabernacle).

The NUD has four polysemes but with a non-transparent numbering because two independent meanings do not have their own polysemy number but are only identified by means of a bullet. In spite of this unsystematic presentation all the meanings are given as separate polysemes below:

1. the transportable shrine of the Jews that especially played an important role during the period in the desert.

• altar cupboard in a Catholic church where bread for the communion is kept.

• a church of some Christian sects, e.g. the Mormons.

2. noise made by celebrating people.

The DDO has three polysemes:

1. sanctuary in the form of a tent that the Israelites took with them according to the Old Testament during their time in the desert.

2. altar cupboard in a Catholic church in which the Eucharistic bread is kept.

3. (place with) noise, festivity and commotion.

The DDB has five polysemes:

1. transportable shrine in a tent used by the Israelites during the desert trek from Egypt to Israel..

2. church of the Mormons.

3. small cupboard where the bread for the communion and the holy casks are kept in Catholic churches.

4. confusing variety of restless noisy people.

5. a fierce and hardly comprehensible discussion with input from different sides.

This example clearly shows that lemma selection is an overrated lexicographic problem. The selection of meaning is much more interesting in this regard as just as many meaning gaps can be detected as are the number of lemma gaps often discussed in dictionary criticism.

All three dictionaries have the lemma talent (talent).

NUD has two homonyms and in total three polysemes, with the exceptional way of giving a separate meaning for the first homonym albeit without an own number. We do not maintain this but rather present three meanings, i.e. also polysemes:

talent, Homonym 1

innate ability within a specific area

• a person who is talented

talent, Homonym 2

a weight and money unit used in ancient times

The DDO has two homonyms and in total four polysemes:

talent, Homonym 1

1. ability or gift within a specific area

2. person who possesses exceptional qualities

talent, Homonym 2

1. weight and money unit of different sizes that was used in ancient times in Babylon and Greece

2. new Greek weight unit, equal to 150 kg

The DDB has two homonyms and in total three polysemes:

talent, Homonym 1

1 innate ability to cope with a specific discipline or type of assignment with exceptional good results

2. person with superb abilities or qualities of whom one therefore has huge expectations

talent, Homonym 2

old weight and money unit that was used in ancient times, among others in Babylon.

With regard to these dictionary articles with talent as lemma one can repeat the comment made with regard to tabernakel: Dictionaries do not differ that much when it comes to lemma selection; the more significant difference is on the level of polyseme selection.

4.2 Polysemy in six English dictionaries

For the purpose of this paper the following English dictionaries were used to look for the equivalents of the lemmas taken from the three Danish dictionaries:

- NODE (The New Oxford Dictionary of English) (1998) Roughly 86 000 lemmas.

- WIK (Wiktionary, Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License) [Internet dictionary (Wordnik)] (2017) No lemma count.

- WordNet 3.0 [Internet dictionary (Wordnik)] (2017) No lemma count.

- HID (The Heritage Illustrated Dictionary of the English Language) (1973). Roughly 68 500 lemmas.

- MWL (Merriam-Webster's Advanced Learner's English Dictionary) (2008) Roughly 38 500 lemmas.

- LSAD (Longman South African School Dictionary) (2007). Roughly 20 500 lemmas.

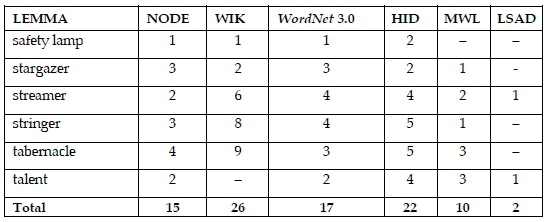

The following table shows a synopsis of the findings of polysemes:

Yet again, one has to negotiate the specific type of dictionary when comparing the number of polysemes presented in the different articles. As can be expected a school dictionary like the LSAD displays fewer polysemes because its cover-age of both lexical items and their meanings is not as comprehensive as that of the other dictionaries. Whereas no lemma count is indicated for WordNet and Wiktionary a comparison of the NODE, HID and MWL shows, contrary to the results in paragraph 4.1, that the highest occurrence of polysemes does not prevail in the dictionary with the most lemmas (the NODE). This is not a significant issue in the current discussion, also because none of these dictionaries are monofunctional.

These dictionaries treat the selected lemmas as follows:

stargazer: With the exception of the LSAD all the other dictionaries have included a lemma stargazer. The meaning of this word is presented as follows:

The NODE has three polysemes:

1. an astronomer or astrologer

2. a horse that turns its head when galloping

3. a fish of warm seas that normally lies buried in the sand ...

WIK has two polysemes:

1. One who stargazes.

2. A perciform fish in the family Uranoscopidae.

WordNet gives the following three polysemes:

1. heavy-bodied marine bottom-lurkers with eyes on flattened top of the head

2. someone indifferent to the busy world

3. a physicist who studies astronomy

The HID has the following two polysemes:

1. an astronomer or astrologer

2. any of various marine bottom-dwelling fishes ...

MWL has a single meaning:

a person who looks at the stars; a person who studies astronomy or astrology

Yet again, the dictionaries have the same lemma but the polyseme selection differs considerably. A Google search on 16 March 2017 gives evidence of a significant number of occurrences of the word stargazer being used to refer to a certain fetal position. However, none of the dictionaries accounts for this meaning.

safety lamp: MWL and LSAD do not include this word as a lemma. It could well be because of a word bias that makes little provision for the inclusion of multiword lemmas.

The NODE, WIK and WordNet each has a single meaning for safety lamp:

NODE

a miner's portable lamp with a flame which is protected, typically by wire gauze ...

WIK

A miner's lamp designed to avoid explosion by enclosing the flame in fine wire gauze.

WordNet 3.0

an oil lamp that will not ignite flammable gases

The HID has two polysemes:

1. a miner's lamp with a protective wire gauze ...

2. any specially protected lamp

The same core meaning is given in all the dictionaries.

Streamer is the only word in the list that has been included all the selected dictionaries. It is treated as follows:

NODE has the following two polysemes for this word, albeit that the second "polyseme" actually gives another variant form:

1. long narrow strip of material used as a decoration or symbol

2. short for TAPE STREAMER

WIK gives the following six polysemes:

1. A long, narrow flag, or piece of material used or seen as a decoration.

2. A newspaper headline that runs across the entire page.

3. A data storage system, mainly used to produce backups, in which large quantities of data are transferred to a continuously moving tape.

4. In fly fishing, a variety of wet fly designed to mimic a minnow.

5. One who searches for stream tin.

6. A stream or column of light shooting upward from the horizon, constituting one of the forms of the aurora borealis.

WordNet also has four polysemes:

1. a newspaper headline that runs across the full page

2. long strip of cloth or paper used for decoration or advertising

3. a long flag; often tapering

4. light that streams

The HID has four polysemes:

1. a long narrow flag, banner or pendant

2. any long narrow pendant, strip of material

3. a shaft or ray of light extending upward from the horizon

4. a newspaper headline that runs across a full page

MWL displays two polysemes and the LSAD a single item giving the meaning:

MWL

1. A long, narrow piece of coloured paper or plastic that is used as a decoration

2. A long, narrow flag

LSAD

a long thin piece of coloured paper for decorating a place.

The different orderings of the same polysemes in the different dictionaries yet again confirm the often unsystematic treatment of polysemy and the difference in the polyseme selection, with senses that apparently have a high frequency of use not qualifying for inclusion in some dictionaries, cannot be explained.

Stringer occurs in all dictionaries but the LSAD.

It has three polysemes in the NODE:

1. a longitudinal structural piece in a framework, especially that of a ship or aircraft

2. informal a newspaper correspondent, not on the regular staff of a newspaper, ...

3. a stringboard [=a supporting timber or skirting in which the ends of the steps in a staircase are set]

WIK has no less than eight polysemes for this word:

1. Someone who threads something; one who makes or provides strings, especially for bows.

2. Someone who leads someone along.

3. A horizontal timber that supports upright posts, or supports the hull of a vessel.

4. A freelance correspondent not on the regular newspaper staff, especially one retained on a part-time basis to report on events in a particular place.

5. Wooden strip running lengthwise down the centre of a surfboard, for strength.

6. A hard-hit ball.

7. A cord or chain, sometimes with additional loops, that is threaded through the mouth and gills of caught fish.

8. A libertine; a wencher.

WordNet has the following four polysemes:

1. a worker who strings

2. a member of a squad on a team

3. brace consisting of a longitudinal member to strengthen a fuselage or hull

4. a long horizontal timber to connect uprights

HID has five polysemes with the second polyseme subdivided into two sub-senses:

1. a person or thing that strings

2. architecture a. A long heavy horizontal timber used for any of several connective or supportive purposes b. A stringboard

3. a lengthwise timber used to support rails

4. a member of a specified string or squad on a team

5. a part-time representative for a news publication ...

The MWL has but a single meaning:

a journalist who is not on the regular staff of a newspaper ...

The subdivision presented in the second polyseme given in the HID leads to a question regarding the selection of polysemes and the way in which polysemes are distinguished. Does the occurrence of different senses of the word stringer in the field of architecture imply that they are subsenses and not senses? In addition, the same comments made with regard to the lemma streamer also apply here. Although the dictionaries do not differ with regard to their lemma selection, there are vast differences regarding the polyseme selection. The inclusion of a word as lemma does not guarantee a successful consultation procedure for a user looking for a specific meaning. Linking lemmas to different meanings is not done in an exemplary way.

The learners' dictionary LSAD is the only one that does not include the lemma tabernacle.

The NODE has four polysemes:

1. (in biblical use) a fixed or movable habitation, typically of light construction

2. a meeting place for worship ...

3. an ornamented receptacle or cabinet ...

4. a partly open socket or double post on a sailing boat's deck ...

WIK has no less than nine polysemes - the highest number of polysemes for any one of the selected lemmas:

1. Any temporary dwelling, a hut, tent, booth.

2. The portable tent used before the construction of the temple, where the shekinah (presence of God) was believed to dwell.

3. Transferred to the Jewish Temple at Jerusalem as continuing the functions of the earlier tabernacle.

4. Any portable shrine used in heathen or idolatrous worship.

5. A sukkah, the booth or 'tabernacle' used during the Jewish Feast of Sukkot.

6. A small ornamented cupboard or box used for the reserved sacrament of the Eucharist, normally located in an especially prominent place in a Roman Catholic Church.

7. A temporary place of worship, especially a tent, for a tent meeting, as with a venue for revival meetings.

8. Of any abode or dwelling place, especially of the human body as the temporary dwelling place of the soul, or life.

9. A hinged device allowing for the easy folding of a mast 90 degrees from perpendicular, as for transporting the boat on a trailer, or passing under a bridge.

WordNet has three polysemes:

1. the Mormon temple

2. (Judaism) the place of worship for a Jewish congregation

3. (Judaism) a portable sanctuary in which the Jews carried the Ark of the Covenant on their exodus

HID has five polysemes and the MWL three:

HID

1. a. The portable sanctuary in which the Jews carried the Ark of the Covenant through the desert. b. The Jewish temple.

2. A case or box on a church altar containing the consecrated host and wine of the Eucharist.

3. A place of worship ...

4. A niche for a statue or relic.

5. A boxlike support in which the heel of a mast is stepped.

MWL

1. A place of worship ...

2. A box in which the holy bread and wine are kept

3. The Tabernacle a small moveable tent that was used as a place of worship by the ancient Israelites

WIK is the only dictionary that does not include the lemma talent.

The NODE has two polysemes:

1. natural aptitude or skill

2. a former weight and unit of currency ...

WordNet also has two polysemes:

1. a person who possesses unusual innate ability in some field or activity

2. natural abilities or qualities

HID has the most polysemes, no less than four, for this word:

1. A mental or physical aptitude ...

2. Natural endowment or ability of a superior quality.

3. Gifted people collectively.

4. A variable unit of weight and money ...

The MWL has three polysemes and the LSAD has one:

MWL

1. A special ability that allows someone to do something well

2. A person or group of people with a special ability to do something well

3. Brit. Slang People who are sexually attractive

LSAD

natural ability to do something well.

A look at the treatment of polysemy in these dictionaries emphasises the consistency in lemma selection but the lack of consistency in polyseme selection. The lesser occurrence of homonyms, in comparison with the Danish dictionaries, should also be noted.

5. Polyseme selection and lemma selection = article selection

In dictionaries that have to assist mother-tongue speakers as well as foreign language speakers with reception problems the most helpful, i.e. the most user-friendly, dictionary will be the one with the most lemmas and the most polysemes.3 With regard to mother-tongue speakers it especially applies to those with a good command of both written and spoken language that experience a text reception problem when confronted with a new word, a new meaning, a rare word or an infrequently used meaning. Including as many lemmas and as many polysemes as possible could lead to a space problem in printed dictionaries, and it should also be considered that comprehensive, especially multi-volume, dictionaries are not easy to handle and are very expensive. But the space problem does not prevail in e-dictionaries. Rapid access could be a problem but this problem can be solved.

A typical approach to polysemy is that the most frequently used words will have the most meanings. This is true when departing from the point of view that a single word has different meanings. One could then argue that a dictionary with few lemmas would usually have many more polysemes compared to a dictionary with many lemmas. The preceding analysis does not support this point of view - rather the opposite. With certain exceptions it was found that the more lemmas in a dictionary, the more polysemes are given for these lemmas. This may be helpful in different types of learners' dictionaries where only the high frequency words and the high frequency meanings are presented. In dictionaries for mother-tongue speakers and advanced learners an approach where a dictionary with many lemmas also has many polysemes is quite surprising and not as helpful to its target users as one would have expected.

Many dictionaries still maintain the traditional distinction between homonyms and polysemes. This tradition is not only dubious but it also does not concur with the understanding of a word. When one assumes that a lemma represents a lexical word or a lexicalised fixed expression and also assumes that a lexical word is a linguistic sign, it does not support the continuation of the current system. One can just look at the different meanings of stjernekigger (stargazer). These different meanings have so little in common that one cannot work with the idea of a linguistic sign with solidarity between the expression and its contents.

Both the relevant discussions in linguistics and theoretical lexicography and the presentation and treatment of homonymy and polysemy in the lexicographic practice show ambiguity in the different perspectives on homonymy and polysemy as two forms of lexical ambiguity. From the field of theoretical lexicography Bergenholtz and Agerbo (2014c) offer their criticism whilst Lyons (1977) deals with uncertainties in linguistics regarding especially the problem of a distinction between homonymy and polysemy. Consequently one can argue in favour of the abolishment of the traditional distinction between homonymy and polysemy. The terms lemma selection and polyseme selection could rather be complemented by the more encompassing term article selection. In the lexicographic practice article selection could proceed in two subsequent steps: (1) lemma selection, that could also be referred to as the selection of expressions and (2) polyseme selection, also to be referred to as selection of meaning. Each article has but one lemma which is the name and guiding element of the article and it combines different variant forms of the expression with the same contents, e.g. all the inflexional forms of a specific lexical word/ lexeme. The meaning selection determines what polyseme should be linked with the expression. This paper argues in favour of an alternative approach compared to the one prevailing in many current dictionaries.

6. Towards an alternative approach

Lyons (1977: 553-554) does not try to find a solution to the problem of distinguishing between homonymy and polysemy but rather finds ways of circumventing it. The two ways he proposes are "to maximise homonymy by associating a separate lexeme with every distinct meaning" - and this procedure he applies to occurrences of both homonymy and polysemy - and secondly to maximise polysemy. This implies "that distinctions of sense can be multiplied indefinitely" and will lead to an increased inclusion of all meanings and senses of a lexical item in a single dictionary article.

From the perspective of a dictionary user with a text reception problem the nature and theoretical status of the distinction between homonymy and polysemy is of little significance. Such a user wants to find the meaning of an unfamiliar word and in order to succeed in such a dictionary consultation this user has to find the specific expression - whether a word, a multiword unit or a lexical item smaller than a word. Whether the meaning is presented as one of the senses of a polysemous word, as a meaning of a homonym or as the only meaning allocated to a lemma that is one of a series of similar expressions does not determine the satisfaction of the user's need. Important is that the user finds the expression and finds the meaning.

The lexicographer has to present an article selection that allocates a specific meaning to a specific expression, presented as lemma of the article. The typical dictionary user is not supported or deterred by a system where lemmas are marked as homonyms - this is an insignificant lexicographic tradition that can be abolished without diminishing the successful satisfaction of text reception needs. But also a maximisation of polysemy does not add value to the text reception solutions of a dictionary. Yet again the user is not interested in relations between senses of a given expression but rather in a specific meaning of a specific expression.

A new approach, relying on the groundwork done by Lyons (1977) in the field of linguistics and Bergenholtz and Agerbo (2014c) in the field of lexicography, could be to maximise article selection by linking each expression as lemma but to a single meaning - whether this meaning is a polyseme or a meaning not related to any other meaning. The suggestions by Lyons to maximise homonymy or polysemy are given within a linguistic frame; the idea to maximise article selection is directed at the lexicographic practice.

Allocating a single meaning to a lemma implies a much more simplified article. The major simplification lies therein that the new approach prevents a proliferation within an article into numerous senses. By restricting the items giving the meaning to a single one per article the user with a text reception need has no problem in quickly linking an expression to the relevant meaning - even though the maximisation of articles leads to the inclusion of different lemmas with the same form. These simplified articles could enhance the access of users to meaning.

Although the existence of the notion of polysemy is not contested, its lexicographic value is questioned. A new approach links expressions to single meanings without being hampered by questions regarding relatedness and non-relatedness between different meanings expressed by words with the same form. Introducing a simplified article structure by moving away from the nesting of polysemes in a single article creates the space and opportunity to present a slightly more comprehensive item giving the meaning. This could further enhance the text reception function of the given dictionary.

7. Some consequences

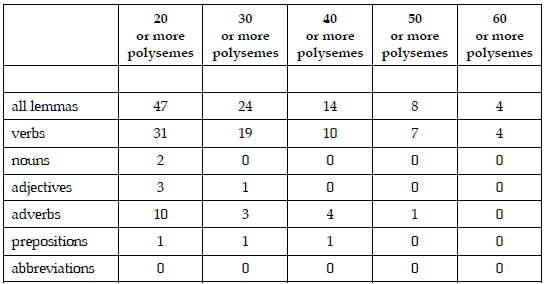

A solution consisting of a maximisation of articles and abolishing the distinction between polysemy and homonymy in the lexicographic practice will necessarily lead to an increase in the number of articles but not as massive an increase as one would have thought.

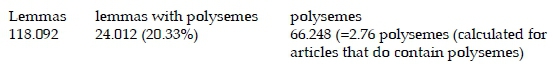

Den Danske Betydningsordbog (2017) contains "only" 222 instances where a single lemma has ten or more polysemes. This represents 0,19% of all articles in this dictionary. The spreading of polysemes is as follows:

When looking at different part of speech classes it is interesting to note that a high number of polysemes can be found in the articles of certain verbs:

verbs 103 (0.19% of all verb lemmas)

nouns 59 (0.07% of all noun lemmas)

adjectives 38 (0.24% of all adjective lemmas)

adverbs 15 (1.39% of all adverb lemmas)

prepositions 15 (9.38% of all preposition lemmas)

abbreviations 1 (0.06% of all abbreviation lemmas)

The relative occurrence of polysemes in the articles of verbs is even bigger if one looks at lemmas with a higher number of polysemes

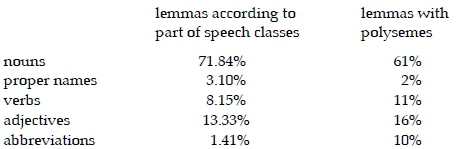

Because it is not possible to have an automatic count of the distribution of polysemes a non-representative count has been made by taking 20 x 100 lemmas from 20 different places in the alphabetical sorting. This shows that in the database for Danish monolingual dictionaries one finds more occurrences of polysemy for nouns than for other part of speech classes (the result for adverbs and prepositions gave less than 1% and is therefore not in the list):

It is also clear from these numbers that there is a definite relation between the number of lemmas and their part of speech classes - with abbreviations as an exception. The number of polysemes for nouns is slightly less compared to the total number of nouns as lemmas. But these numbers do show that polysemy is especially relevant for nouns, whereas a huge number of polysemes occur at a small number of verbs. Of the 118.092 articles in Den Danske Betydningsordbog (2017) 25 012, i.e. 20.33%, display polysemes. The number of articles in a dictionary without homonymy and polysemy will therefore rise but not too much. Such an approach will also give the user a true indication of the extent of a dictionary because, as seen from the examples given in this article, two dictionaries could have selected a given number of lemmas but with completely different numbers of meanings for these lemmas.

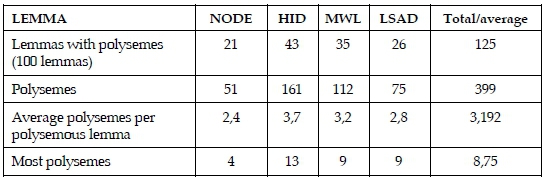

Four of the English dictionaries used in this paper also show that for a random count of 100 lemmas the average number of polysemes per lemma where polysemy prevails is only 3,192 and only 31,25% of all lemmas display polysemes.

This yet again emphasises the fact that an abolishment of homonymy and polysemy in dictionaries in favour of a maximisation of articles will not increase the number of articles too drastically. In a printed dictionary the result will be manageable and in online dictionaries this approach will cause no problems at all.

The type of discussion presented in this paper with regard to polysemy could be expanded to other semantic relations, e.g. synonymy. Where polysemy and polyseme are terms that are used to reflect something of the relation between an expression and different meanings, the terms synonymy and synonym are used to reflect on the relation between a single meaning and different expressions. The suggested treatment of polysemy where each polyseme has its own article, coincides with the treatment of synonymy where the same meaning can be repeated in different articles introduced by different lemmas that are synonyms. In certain types of dictionaries synonyms can also be used as the item giving the meaning of another word. This topic will not be discussed in this paper. Bergenholtz and Gouws (2012) offer more in this regard.

8. In conclusion

In this paper the lexicographic presentation of homonymy and especially polysemy was discussed from the perspective of a dictionary for text reception purposes. It could be argued that a similar approach can be employed in dictionaries for the other communicative functions, i.e. text production and translation, but not in a dictionary with a cognitive function. There homonymy and polysemy may have a role to play, albeit that lexicographers should take cognizance of the suggestions made by Lyons (1977).

The approach suggested in this paper can be regarded as a theoretically based suggestion for the lexicographic practice. The needs and reference ease of the target user group should be a determining factor in each and every decision regarding the selection, presentation and treatment of items in a dictionary. This approach will lead to a noticeable increase in the number of articles this will not be a problem in online dictionaries, the default medium of modern-day lexicography. The simplification of dictionary articles with only a single item giving the meaning in each article shows that a text reception dictionary does not have to maintain the shaky distinction between homonymy and polysemy. The lack of such a distinction is no loss for lexicography if one considers the limited help the traditional lexicographic presentation of homonymy and polysemy has offered the user in need of text reception assistance.

Acknowledgement

This work is based on research supported in part by the National Research Foundation of South Africa (Grant specific unique reference number (UID) 85434). The Grantholder acknowledges that opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in any publication generated by the NRF supported research are that of the author(s), and that the NRF accepts no liability whatsoever in this regard.

References

Allen, R.E. (Ed.). 19908. The Concise Oxford Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [ Links ]

Bergenholtz, Henning et al. (Eds.). 2017. Den Danske Betydningsordbog. Odense: Ordbogen.com (www.ordbogen.com). [ Links ]

Bergenholtz, Henning and Heidi Agerbo. 2014a. Meaning Identification and Meaning Selection for General Language Monolingual Dictionaries. Hermes. Journal of Language and Communication in Business 52: 125-139. [ Links ]

Bergenholtz, Henning and Heidi Agerbo. 2014b. Extraction, Selection and Distribution of Meaning Elements for Monolingual Information Tools. Lexicographica 30: 488-510. [ Links ]

Bergenholtz, Henning and Heidi Agerbo. 2014c. There is No Need for the Terms Polysemy and Homonymy in Lexicography. Lexikos 24: 27-35. [ Links ]

Bergenholtz, Henning and Rufus H. Gouws. 2012. Synonymy and Synonyms in Lexicography. Lexicographica 28: 309-335. [ Links ]

Den Danske Ordbog. Moderne dansk sprog. 2017. http://ordnet.dk/ddo. (Accessed February 2017.)

Geeraerts, Dirk. 1986. Woordbetekenis: een overzicht van de lexicale semantiek. Leuven/Amersfoort: Acco. [ Links ]

Geeraerts, Dirk. 2013. The Treatment of Meaning in Dictionaries and Prototype Theory. Gouws, Rufus H. et al. (Eds.). 2013. Dictionaries. An International Encyclopedia of Lexicography. Supplementary Volume: Recent Developments with Special Focus on Computational Lexicography: 487-495. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Gouws, Rufus H. 1983. Polisemie as leksikografiese probleem. Sinclair, A.J.L. (Ed.). 1983. G.S. Nienaber - 'n Huldeblyk: 199-205. Bellville: UWK Drukkery. [ Links ]

Gouws, Rufus H. 1989. Leksikografie. Cape Town: Academica. [ Links ]

Halas, Ana. 2016. The Application of the Prototype Theory in Lexicographic Practice: A Proposal of a Model for Lexicographic Treatment of Polysemy. Lexikos 26: 124-144. [ Links ]

Hanks, Patrick. 2000. Do Word Meanings Exist? Computers and the Humanities 34: 205-215. [ Links ]

Hanks, Patrick and Jane Bradbury. 2013. Why Do We Need Pattern Dictionaries (and What is a Pattern Dictionary, Anyway)? Kernerman Dictionary News 21: 27-31. [ Links ]

Jeffery, C.D. 1982. An Application of Firthian Principles to the Analysis of Polysemous Lexical Items. Van Rensburg, M.C.J. (Ed.). 1982. Kongresreferate: 18de Jaarlikse Kongres van die Linguiste-vereniging van Suider-Afrika, Rhodes Universiteit, Grahamstad: 113-126. Bloemfontein: Universiteitsdrukkers UOVS. [ Links ]

Leth, Jens. 1800. Dansk Glossarium. En Ordbog til Forklaring over det danske Sprogs gamle, nye og fremme Ord og Talemaader for unge Mennesker og for Ustuderede. Et Forsog. Med en Fortale af Professor Rasmus Nyerup. Kkibenhavn: Trykt paa Hofboghandler Simon Poulsens Forlag hos Bogtrykker Morthorst's Enke & Comp.

Louw, Johannes P. 1995. How Many Meanings to a Word? Kachru, Braj and Henry Kahane (Eds.). 1995. Cultures, Ideologies, and the Dictionary. Studies in Honor of Ladislav Zgusta: 357-365. Tübingen: Niemeyer. [ Links ]

Lyons, John. 1977. Semantics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Morris, William. 1973. The Heritage Illustrated Dictionary of the English Language. Boston, Massachusetts: American Heritage Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Panman, Otto. 1982. Homonymy and Polysemy. Lingua 58: 105-136. [ Links ]

Pearsall, J. (Ed.). 1998. The New Oxford Dictionary of English. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Perrault, Stephen, J. (Ed.). 2008. Merriam-Webster's Advanced Learner's English Dictionary. Springfield, Massachusetts: Merriam-Webster. [ Links ]

Politikens Nudansk Ordbog. 2005. 19. udg. København: Politikens Forlag.

Stock, Penelope F. 1984. Polysemy. Hartmann, Reinhard R.K. (Ed.). 1984. LEXeter '83 Proceedings. Papers from the International Conference on Lexicography at Exeter, 9-12 September 1983: 131-140. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer. [ Links ]

Summers, Delia (Ed.). 2007. Longman South African School Dictionary. Harlow: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Wahrig Gerhard. 1973. Deutsches Wörterbuch. Gütersloh/Berlin/München/Wien: Bertelsmann Lexikon Verlag. [ Links ]

Wiktionary, Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License. [Internet dictionary (Wordnik)] (2017).

WordNet 3.0 [Internet dictionary (Wordnik)] (2017).

Zgusta, Ladislav. 1971. Manual of Lexicography. The Hague: Mouton. [ Links ]

1. In this paper the term polyseme refers to a linguistic expression that has more than one meaning and to each one of those meanings and the rest of the partial articles that has the same expression as lemma.

2. Henceforth only the English translations of the Danish polysemes will be given.

3. It may differ in a dictionary for text production purposes, especially for foreign language users, but this paper is only concerned with text reception.