Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Scientia Militaria: South African Journal of Military Studies

versão On-line ISSN 2224-0020

versão impressa ISSN 1022-8136

SM vol.51 no.1 Cape Town 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.5787/51-1-1404

ARTICLES

South Africa's Military Deployment to Northern Mozambique: Lessons from the United States of America's (Mis)Adventure in Afghanistan

Joseph Olusegun Adebayo80

Journalism and Media Studies Department Cape Peninsula University of Technology Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

In mid-2021, the government of South Africa deployed troops from the South African National Defence Force to the troubled Northern Province of Mozambique as part of a Southern African Development Community regional force to quell the threat posed by insurgents in the country. Poignantly, the deployment happened at about the same time the United States of America completed the withdrawal of its troops from Afghanistan after twenty years of military intervention. Shortly after the departure of the American troops, Afghanistan degenerated into anarchy with the takeover of government machinery by the Taliban, bringing to the fore years of discourse on the sustainability of military interventions. Scholars have adduced many reasons for the American "failure" in Afghanistan. One of the most prominent reasons was the failure of American policymakers to understand the role of tribe, religion, and ethnicity in conflict dynamics. Although the socio-political, socioeconomic, and sociocultural contexts of the South African intervention in Mozambique differ from the American context, there are lessons South Africa could learn to avoid some pitfalls. Employing secondary data, they study on which this article is based, examined the 20-year military American involvement in Afghanistan to proffer possible lessons for the involvement of the South African government in Mozambique.81

Keywords: Afghanistan, Cabo Delgado, Military Intervention, Mozambique, Southern Africa Development Community (SADC), South African National Defence Force (SANDF).

Introduction

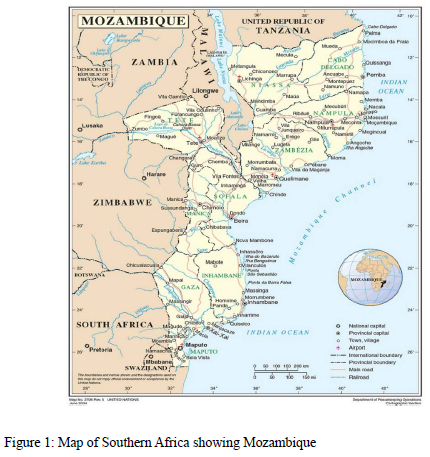

Mozambique has undergone one conflict after another since its independence from Portugal in June 1975. Shortly after independence, there was a bitter civil war from 1977 to 1992 between FRELIMO and RENAMO. Then, after a period of momentary negative peace, fighting resumed in 2013. However, the warring parties eventually signed peace deals in 2014 and 2019. Nonetheless, amidst the fighting between FRELIMO and RENAMO, an Islamist militant group, who identify as the Ansar al-Sunna, emerged, launching terror attacks in villages and towns in Mozambique's northern province of Cabo Delgado.82 The first major attack was in early October 2017. Since then, the insurgency has escalated, leading to increased attacks on civilians, public infrastructure, and government buildings.83 At the end of2020, the conflict claimed an estimated 2 400 lives and internally displaced close to half a million people.

While terrorist organisations generally seek attention by claiming attacks (sometimes falsely) and making public statements, Ansar al-Sunna's modus operandi seems different. The group rarely makes public statements, and their motives remain unclear. This has consequently given rise to speculation and conspiracy theories regarding the existence of the group. For example, state officials believe the quest to control Cabo Delgado's oil, gas and mineral riches is the main motive behind the insurgency. The government also claims unemployment amongst the youth population is the reason behind the attacks, and that global Jihadist organisations are preying on the vulnerability of the unemployed.84

According to the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED), which tracks political violence worldwide, the ongoing insurgency in Mozambique has led to over 3 100 deaths and the internal displacement of nearly 856 000 people. UNICEF estimates that most of the affected are women and children. In May 2020, at the Extraordinary Organ Troika Summit of Heads of State and Governments, held in Harare, Zimbabwe, the government of Mozambique requested assistance from the Southern African Development Community (SADC) member states to contain growing acts of terrorism within its territory. However, it took over a year before the regional body sent troops to the troubled nation. The delay by the SADC to intervene emboldened the insurgents further, with their activities spreading beyond Mozambique's northern province and threatening to spill into neighbouring countries.85

The example of Boko Haram's speedy growth and transformation from a group of stick-wielding Islamists in a remote town in Borno State, North-East Nigeria, into one of the deadliest terrorist organisations in the world should have spurred SADC member states into swifter action. For example, from what was geographically a "Nigerian conflict", the Boko Haram insurgency spread to Chad, Cameroun, and Niger, threatening several other countries in the Sahel region. The decision by SADC member states to deploy a standby force in support of Mozambique to combat terrorism and acts of violent extremism in Cabo Delgado, though arguably late, is a commendable one. Although there were no official data on the numerical strength of the standby force, estimates put the figure at about 3 000 soldiers, with the bulk coming from South Africa.86

This article focuses on South African (SA) military involvement in Mozambique. Given the pivotal strategic position of South Africa in the sub-region and the continent at large, the success or failure of the regional military intervention in Mozambique would depend to a large extent on the SA commitment - militarily, politically, and economically. Arguably, South Africa gains most when the region is at peace. Conversely, a destabilised subregion has the potential to affect South Africa adversely. Moreover, a refugee crisis is not what South Africa needs anytime soon. Government statistics put the SA population at 60 million, with estimated 3 million immigrants.87 South Africa has been plagued by recurrent bouts of xenophobic violence since at least 2008, with foreigners often accused of taking jobs in a country where a third of the workforce is unemployed.88 Escaping the crisis in Mozambique could worsen the immigration challenge South Africa currently faces. Even more worrisome is the possibility of the "crossing over" of radical Islamists from Mozambique into South Africa. Essentially, South Africa is not only in Mozambique for the sake of Mozambique and the SADC. South Africa is in Mozambique because of (and for) South Africa itself.89

It is, however, critical for South Africa not to miss the ethnoreligious side of the conflict in Mozambique. There are many underlining remote and immediate causes of disputes, and if not considered when designing peacekeeping or military intervention, these disputes could cause widespread resentment. The "failures" of military interventions by America in Vietnam, Iraq, Venezuela, and Afghanistan show the need to understand the politics of tribes before embarking on military or even diplomatic missions abroad. South Africa must not assume that all Mozambicans would rally around them in support. On the contrary, in sharply divided societies, for instance Mozambique, interventions such as proposed by the SADC often stimulate group conflict with political movements and parties coalescing around more primal identities, such as tribe and religion.90

Mozambique: Deconstructing an Insurgency

The origin of insurgency in Mozambique dates to the early 2000s when young men within the Islamic Council of Mozambique began to forge a radical approach to their practice of Islam. After facing opposition from prominent Islamic clerics, the group created a registered sub-organisation within the Islamic Council called Ansaru-Islam. The group, which started in Cabo Delgado, built new mosques, and preached a stricter form of Islam. Their initial focus was on religious debates, practice, and opposition to the secular state. However, in 2010, the villagers of Nhacole in the Balama District destroyed the group's mosque and chased out sect members who fled to Mucojo in the Macomia District. The group also faced stiff opposition in Mucojo. For example, in 2015, violence erupted when sect members tried to impose an alcohol ban forcefully. As a result, the police had to intervene on various occasions.91

Although the Mozambican government has consistently claimed to be actively fighting insurgents and insurgencies in the country, the crisis does not seem to subside. Five issues have affected the ability of the government's counter-insurgency (COIN) efforts.

• The government was generally clumsy in handling the insurgency, particularly the response of security agencies. There were indiscriminate arrests of innocent members of the public instead of arresting Islamists - this brewed resentment amongst members of the public against the police and other security agencies. This approach is akin to the initial response of the Nigerian police and military to the Boko Haram insurgents in their early days in Maiduguri. There were accusations of indiscriminate arrests (and summary execution) of young men and women in Maiduguri in the guise of arresting Boko Haram members. The action of the Nigerian police and armed forces fuelled community resentment, thereby making initial efforts at ending the insurgency futile.

• The government restricted and clamped down on journalists and human rights organisations. This meant that the only communication that made it to the public sphere was from the government or the insurgents. The implication was that propaganda from both ends became rife.

• The ongoing piracy of the Mozambican coast and the intractable insurgency by RENAMO divided the government's focus and drew attention away from the catastrophe in Cabo Delgado.

• The challenge posed by widespread inequality, poverty, and corruption enabled the insurgency in the first place. But, again, the problem was similar to the Boko Haram insurgency in Northern Nigeria, where poverty, a lack of primary education, and religiosity permeate society.

• There is the challenge of a lack of inter-paramilitary cooperation. As a result, the Mozambican military and national police battle for operational control, to the detriment of the war against insurgency.92

Perhaps, one of the most telling challenges ofthe Salafi-jihadi insurgency in Mozambique is the gradual whipping up of ideological sentiments. The insurgents recognise longstanding feelings of marginalisation, exclusion, and relative deprivation.93 However, recent direct drivers, such as current economic changes, the way the Mozambican government handles governance challenges, and the influence of regional and global jihadi groups, have escalated the conflict. Moreover, the group has been able to win over some members of their host communities subtly, further complicating an already complex war.

Here lies one of the significant challenges of military intervention, especially from an SA perspective. Because the insurgency in Mozambique has gradually evolved into an ideological one, there is a need to understand that the South African National Defence Force (SANDF) must consider the complexities of local group dynamics beyond military intervention.94 The Mozambican government has already revoked its earlier stance that foreign elements sponsored the conflict. Instead, the government approached the European Union to help them (with the finances?) to address the feelings of marginalisation by sections of the country. Chua argues that the failure of American policymakers to understand or consider group dynamics and political tribes in the lead-up to American military intervention in Afghanistan could be one of the reasons America failed in Afghanistan. She remarked thus:

The Taliban is not only an Islamist but also an ethnic movement. The vast majority of its members are Pashtuns. Pashtuns founded it. It rose out of and derived its staying power because of threats to Pashtun dominance. Unfortunately, American leaders and policymakers missed these ethnic realities entirely, and the results have been catastrophic.95

The Polemics of Contemporary Military Interventions

Military interventions, especially the need for or against them, have assumed different meanings in the last decade, i.e., 1990 to 2020. For example, during the Cold War (1947-1991), military interventions allowed "powerful" states to dominate "weak" ones. However, there have been justifications for military interventions recently, especially where the goal was to avoid humanitarian catastrophes and to re-establish international peace and security. Punitive intervention saw the light in the late 1980s. The United States (US) air strike on Libya in 1986 was the first example. A new pattern of collective intervention preceded an extraordinary diminution of other unilateral practices in the early 1990s. Missile attacks by the United States on Iraq in 1993 and against military installations in Afghanistan and Sudan in August 1998 triggered much of the then new interventionist debate. These attacks prompted the rising discussions on the legitimising effect of humanitarian interventions resulting from unilateral state-centred interventions. Whether unilateral or multilateral, humanitarian intervention became central to the polemics of the new debate on intervention.96

The challenge with humanitarian interventions is that organisations or governments often premise interventions on an assumption of an understanding of local contexts by the intervening organisation or nation. For example, UN-led military interventions in Africa have not achieved the desired results, despite billions of dollars spent and the use of superior weapons compared to armed militia groups in the countries where UN military forces operate. Vested interests have hampered UN military interventions in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Sudan, Mali and the Central African Republic (CAR). In addition, the UN failed to fully understand the underlying sociocultural and socio-political issues. United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the DR Congo (MONUSCO) operates to neutralise armed groups and to reduce the threat posed to state authority and civilian security space for stabilisation activities. However, in most African countries where the organisation operates, it has failed to achieve its lofty goals set during its formation in 1999. For example, in South Sudan, the organisation has been unable to stem the growth and incessant raping of young women and girls and maiming of innocent civilians by armed militia groups. The underlying issues are sometimes more profound than what military interventions alone can settle.97

Former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan once admitted that the United Nations lacked the institutional capacity to conduct military enforcement measures under Chapter VII of the UN Charter. Mr Annan, while presenting his UN Report on Reform, stated that the United Nations could not implement decisions on the Security Council rapidly and effectively, calling for the dispatch of peacekeeping operations in crises. Increasingly, the United Nations has reduced its missions and peacekeepers globally. Apart from the cost of such missions, the bottom line is that most UN missions do not succeed in achieving their set goals. Although this article focuses on SA involvement in the SADC intervention force in Mozambique, South Africa could glean many lessons from past UN military interventions especially their challenges.98

Theorising an Intervention: The Just War Theory

South African (SA) military intervention in Mozambique can be premised within the ambit of the just war theory. Although eclipsed for nearly two centuries (1700-1800), the theory has regained prominence at the forefront of public discourse because of two conditions of the contemporary world:

• A new international system has replaced the once-dominant European balance-of-power system with a more diverse powerplay and "players"; and

• The magnitude, range and impact of military weapons available for warfare in the modern world were unimaginable years ago. These "new" weapons have unprecedented and unquantifiable destructive capabilities, thereby radically altering the technique and rationale of (and for) warfare.99

The just war theory is premised on Christian philosophy, although scholars suggest that the idea extends back to Christianity.100 The theory states that:

• Taking a human life is wrong;

• States must act swiftly in a manner that defends their citizens, the state, and justice; and

• Defending moral values and protecting innocent human life require a willingness to use force and violence.101

The main components of the just war theory are Jus ad Bellum - the decision of the justification for war; and Jus in Bello - the conduct during the war.

Given the potential of the Mozambican conflict spilling over into South Africa, one can safely argue that South Africa is "right" in providing its troops for military intervention in Afghanistan.

Scholars have further broken down the features of Jus ad Bellum:102

• There must be a just cause to go to war;

• The decision ought to be made by a legitimate authority;

• Force is to be used only with the right intention and as a last resort;

• There must be reasonable hope for success, with peace as the expected outcome; and

• The use of force must be proportionate and discriminate

It is safe to assume that SA military intervention in Mozambique met the conditions or features of Jus ad Bellum mentioned above. There is a just cause for the intervention. The continued Islamist insurgency poses a real threat to the peace, security, and territorial integrity of South Africa. As stated earlier in this article, the potential impact is beyond a possible spilling over of violent acts into SA territory (although that is a possibility). The probable influx of refugees seeking safety in South Africa poses a socioeconomic threat. South Africa is already grappling with an immigration challenge that has fuelled feelings of relative deprivation, frustration, aggression, and xenophobia among local people.

The decision to intervene in Mozambique was also legitimate as the South African Presidency sanctioned it following the 16-nation SADC resolution to support the Mozambican goal of quelling the insurgency.

The use of proportionate and discriminate force is debatable. What is proportionate? What is discrimination? These questions become even more pertinent in a multi-ethnic and ethno-religiously divided nation, such as Mozambique. Furthermore, given the massive recruitment of civilians, some under aged, in the Mweni region of the country, differentiating between civilians and combatant insurgents is a Herculean task. Chances are therefore that disgruntled local Mozambicans would accuse the SA military of war crimes at some point in the intervention. The accusations have already started. For example, clips depicting some members of the SANDF hurling a corpse over a pile of burning rubble in Mozambique have irked public concerns. The gory clip also showed a soldier pouring a liquid over the body as other soldiers, dressed in SA military uniforms, watched, and filmed the scene on their mobile phones. Such images could raise local dissatisfaction with the military, making the already tricky intervention even more challenging.103

An essential feature of Jus ad Bellum critical to the study reported here was that there must be reasonable hope for success, with peace as the expected outcome. This feature was one of the main focuses of the study. Further, the researcher considered the point at which the SA military would achieve success in Mozambique. Sociopolitical conditions regarded as a success were defined, and it was questioned whether "success" should be according to UN protocols or SA foreign policy. Lastly, the researcher had to decide how success would be measured. It is vital to state that the current study did not take the very robust SA foreign department for granted. It is, arguably, one of the most professional foreign departments on the continent. The chances that policymakers and experts in the Presidency had asked and answered these salient questions and more before committing to military intervention in Mozambique are therefore high indeed. However, as social scientists, it is pertinent that we do not assume anything. Sometimes, policymakers can find the missing link between policy conception and policy implementation in a well-thought-out research article, a conference, a colloquium, or a policy brief. There are however (but should not be) assumptions in the humanities and social sciences.

The US (Mis)adventures in Afghanistan

For two decades (2001-2021), the United States stationed its troops in Afghanistan in a war that claimed over 2 300 US military personnel and various injuries to over 20 000 others. Estimates put the cost of the Afghan (mis)adventure at over $1 trillion. Operation Enduring Freedom, as the US mission in Afghanistan (and the larger-scale global war on terrorism) was code-named and had clear mandates by then-President George Bush.104The orders were to destroy al-Qaeda, which had attacked the United States on 9/11, and to overthrow the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, which had hosted them. However, the conflict also claimed close to half a million Afghans, i.e. government forces, Taliban forces and civilians. One would have expected such considerable numbers of human and material sacrifices to translate into a more stable Afghanistan. Unfortunately, however, the consensus is that the US mission was a failure, especially after America had conducted a rushed, poorly planned, and chaotic withdrawal that left many Afghans and the world apprehensive about the potential ripple effects on peace and security in the Middle East and globally.105

The US-led military mission in Afghanistan, which started in 2001, had its roots in the global Cold War of the 1970s, especially with the invasion of Afghanistan by the Soviets in December 1979. The invasion led to sanctions by the United States against Moscow, entangled in efforts to stabilise communist Afghanistan against rising Islamic backlash. The government of President Ronald Reagan embraced the anti-communist insurgents, the Mujahideen, a group the government of President Jimmy Carter armed and referred to as "freedom fighters". As a result, there had been a history of conflicts between the two nations, with deep-seated resentments even before the 2001 US mission to Afghanistan.106

Perhaps unwittingly, one of the fallouts of the US-led military mission to Afghanistan was the unholy alliances that Islamist groups formed to wage war against the United States. Soon, the American military mission in Afghanistan became perceived as a US-led war against Islam, not Islamism. Since Afghanistan is a Muslim country, the US-led war validated al-Qaeda's ideology of "saving Islam from foreign infidels" and winning the support of not just other Islamist groups but also some members of the Muslim world.107

Here lies an important lesson for SA involvement in Mozambique and future military involvement in Africa and globally. The rise of radical Wahhabism2 in Mozambique means that Islamist groups have radicalised young Mozambicans into believing that the ongoing insurgency is a wholly religious one - an attempt to plant Islam throughout the entire Mozambique. Any country attempting to halt that process would inevitably be regarded as an enemy of Islam, moving the conflict to ideological warfare. Ideological warfare is often most difficult to handle. It is one thing to fight insurgents, but to fight an ideology premised on religious conviction is something entirely different. As a result, South Africa could unwittingly be termed an "enemy of Islam", thereby courting disaster in the form of "new" regional enemies.

It is crucial to differentiate the American invasion of Afghanistan from the South African military mission in Mozambique. The American invasion of Afghanistan was an emotional response aimed at satisfying the collective psychological need for revenge for the 9/11 attacks rather than a strategic consideration. South Africa however deployed its troops to Mozambique to help quell rising insurgency and terrorism among Islamic State-connected insurgents. One can argue that the South African move is strategic rather than impulsive.108However, even the best strategies fail when faced with on-the-ground realities. The SA-led SADC intervention force already met a series of setbacks, namely logistics hiccups, a lack of inter-military cooperation in intelligence gathering and sharing, especially with Rwandan and Mozambican troops, and poor coordination in general. These challenges sound similar to the early issues American troops faced in Afghanistan.

Focus on Terrorism rather than Insurgency

One of the reasons adduced for the American failure in Afghanistan was the inability of the United States and its allies to create and train home-grown Afghan national security forces capable of handling the security challenges plaguing the nation. It was obvious that the US-led troops would not be in Afghanistan forever. Experts argue that the United States focused on the Taliban as an extremist group rather than as a significant political insurgent force. In failing to address the real-world level of Afghan progress in governance, security, and economics, it treated one symptom of a far broader disease in many ways and, in doing so, did much to defeat itself.109

Suffice it to add that in Mozambique, the SA, and SADC Mission in Mozambique (SAMIM) focus on counterterrorism and COIN operations. The scale and precision shows intentionality of purpose. The goal should be building the capacity of the Mozambican army and government to stem the remote and immediate causes of violent extremism or the propensity for young people to join extremist groups.

The United States undermined the legitimacy of the Afghan state by focusing on the "War on Terror". They further undermined efforts by the international community to accelerate peacebuilding activities in Afghanistan. Moreover, the approach adopted by the United States enabled a slanted narrative from the Taliban about its goal of violently resisting the oppressive and authoritarian tendencies of the United States against perceived weak states, particularly Islam. The Taliban, with the unintentional help of the United States, thus established itself as an alternative authority.110

Ignoring Underlying Ethnoreligious Differences

Another reason why the United States failed in Afghanistan was a lack of attention to underlying ethnoreligious divisions already existing in Afghanistan. The multi-ethnic Islamic population in Afghanistan further consists of fractious political clans and tribes. Victory over an Islamist group by members from certain ethnic groups would unwittingly mean victory for the "other" ethnic groups. There is no winning such a war. It was a vicious pendulum, which led to dissatisfaction wherever it swung. The American problem in Afghanistan was a failure to understand that it was not simply about a war against radical Islam. It was also an ethnic problem rooted in a cardinal rule of tribal politics: ethnoreligious groups do not give up their dominance quickly once they are in power.111

The war in Mozambique has similar remote and immediate causes, and South Africa should pay attention to the dynamics to avoid the mistakes of the American military mission in Afghanistan. Rather than focus on terrorism alone, South Africa should examine the ethnic dimensions of the conflict. There are feelings of relative deprivation from certain ethnic groups in Mozambique, particularly the Mweni, who reside on the coast. The Mweni ethnic group has consistently complained of marginalisation due to a lack of economic development and political participation; thus, making them ready recruits for any group, such as Ahlu Sunna Wal Jama (ASWJ), which promises an improvement of their socioeconomic position.112

Using Fraym's human geography data,113 a recent study examined the ethnic dimension of the conflict in Mozambique.114 Researchers combed a base layer map depicting the percentage of Makua language speakers with attack locations. Findings showed that 93 per cent of terrorist attacks were conducted in areas with low-density Makua speakers; thus, affirming the ethnic component of the insurgency. Suffice it to say that the study highlighted a cluster of attacks in the Cabo Delgado Makau areas in the interior, and Makonde communities on the northcentral border with Tanzania. Researchers argued that this could be due to a change of tactics by ASWJ in 2019 by refocusing its operations on the coast and road networks for easy escapes after attacks. The shift indicates that ASWJ faced difficulties recruiting fighters in non-Mweni areas, further confirming the ethnic dimension of the conflict.115

This article however does not suggest that ethno-religiously diverse nations are more prone to civil wars or insurgencies than homogenous ones. Several racially and ethnically diverse nations are not engrossed in civil war or overt physical violence, such as Brazil and the United States of America. However, such countries could be experiencing some form of structural violence, although very few ever spiral into outright civil war.117 Insurgencies, like the one in Mozambique, are often fuelled by conditions that favour insurgency, such as small, lightly armed bands practising guerrilla warfare from rural base areas. While this position is arguable, it is pertinent to note that the Mozambican conflict, like the Boko Haram conflict in Northeast Nigeria, is entangled in difficult-to-discern ethnoreligious dynamics where it is increasingly difficult to differentiate cultures from ethnicity and religion. As conflicting, even confusing as this may sound, the bottom line is that the SANDF intervention in a sociocultural and sociopolitical terrain, such as Mozambique, about which they have little or no knowledge, should be considered completely neutral. 'Befriending' a group could be mistaken for supporting one ethnic group over another, causing dissatisfaction and, ultimately, failure.118

US policymakers acted with ignorance of the peculiarity of the Afghan context. In addition, US officials failed to interact with locals, making assumptions and conducting military operations hoping these would lead to security and stability. The lack of contextual knowledge meant that US policymakers and troops in Afghanistan implemented projects that sometimes unwittingly appeared to support one powerbroker or ethnic group at the expense of another. The action by the United States stoked local conflicts and created opportunities for insurgents to form alliances with disaffected parties.119

Unrealistic Timelines and Expectations

Interestingly, the SANDF mission in Mozambique has not generated much public interest. Many South Africans are probably unaware that their troops are stationed in a nation just a few thousand kilometres away, and that the success or failure of the mission could affect their lives in one way or the other. In addition, the country grapples with a myriad of other sociopolitical and socioeconomic issues of its own. Still, the near lack of attention to (or even interest in) the activities of SANDF could lead to complacency on the part of the military, such as an unverified video showing SA soldiers allegedly cruelly burning a dead body.120

America's military missions abroad have consistently been subjects of national discourse in the United States. Americans thus often hold the military to their word when the US military lists timelines and expectations. Nonetheless, one of the primary reasons the US mission in Afghanistan failed was because of unrealistic timelines and expectations rather than a plan dealing with what was realistically achievable with the knowledge of what was on the ground in Afghanistan. The United States hence prioritised its political preferences for what Afghanistan should look like. Moreover, it was all on US terms. US officials were vague about the exact resources required to undertake the mission, and how long it would take to achieve the set goals. Instead, US officials provided implicit deadlines that ignored sociopolitical and sociocultural dynamics in Afghanistan. As stated earlier, it was a hurried step to assuage an angry US public following the 9/11 bombing.

Unsurprisingly, twenty years after the invasion of Afghanistan, and with nearly $1 trillion spent, the United States hurriedly left the country almost the same way they came in. One of the goals of the US mission in Afghanistan was to flush out the Taliban. Ultimately, the United States handed over a deeply fractured Afghanistan to the Taliban when it left. The SA government must set realistic and achievable goals and timelines for the SANDF to avoid the mistake America made in Afghanistan. Again, it is vital to restate that the SANDF has very professional military strategists who must have liaised with the Presidency to ensure that the goals and timelines of the military mission in Mozambique were deliberated and agreed upon. This policy-directional article aims to contribute to ensuring that the SANDF and the South African presidency are meticulous and precise in their approach to the execution of the military mission to Mozambique.

Undertaking military missions with unrealistic goals and a lack of timelines is like playing a football game without goalposts, duration and referees. It is an aimless venture that will ultimately lead to burnout. Already, the SANDF has extended its mission to Mozambique. Military missions globally are often stretched for one reason or the other. The fact is that war operations are punctuated by unpredictability and uncertainty, especially COIN and counterterrorism operations. Already there were deadlines set by the SA government before the initial deployment. As stated in the just war theory, not only is there a need for a just cause to go to war; there must be reasonable hope for success, with peace as the expected outcome. The keyword here is "expected outcome".121 Expectations must be set (with obvious considerations for the unpredictability of wars) and continually measured. Such expectations have to include a possible end date for involvement in an intervention.

The aim of setting deadlines is not to have rigid start and end dates. As stated earlier, military missions are unpredictable. However, the Presidency has to ensure that the SA mission to Mozambique does not snowball into a never-ending war, like the American mission in Afghanistan, which lasted twenty years. The deadlines provide 'break' periods to assess the mission vis-á-vis set goals and objectives to determine whether progress is being made. Without such 'windows', the mission could become endless. 122 The SANDF statement during the announcement of the extension of the military mission thus stated:

We must create conditions for the people of Mozambique to start picking up where things have fallen between the cracks and start going on with their lives, so governance aspects must also be strengthened because the problem cannot be resolved purely through the military.123

Corruption

The ultimate point of failure for our efforts ... wasn't an insurgency. It was the weight of endemic corruption.124

The continued stay of the SANDF in Mozambique could also breed government and military corruption. Military missions are expensive.125 Brown University's Cost of War project estimated that America spent $290 million daily for 7 300 days of war and nation building in Afghanistan. When the United States hurriedly left Afghanistan, it left abandoned air bases, untraceable lethal weapons, uncompleted construction projects, and an army of Afghans who had become rich through US-aided corruption. No matter how well-intentioned military interventions are, they sometimes become channels for organised crime by both the military and government officials. Corruption becomes prevalent when the war lingers for longer than necessary or anticipated. A total of 115 US service members were convicted of stealing, rigging contracts, and taking bribes. Since 2015, crimes in Iraq and Afghanistan have been valued at more than $50 million.126

The problem with corruption in military interventions is that it often "succeeds" in nations with a propensity for corruption. For example, the 2021 Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction Report suggested the United States fuelled corruption in Afghanistan by injecting tens of billions of dollars into the Afghan economy, using inadequate oversight and contracting practices, and partnering with malign powerbrokers. According to the report, the US government was slow to recognise the magnitude of the problem, the role of corrupt patronage networks, the way corruption threatened US goals, etc.127

The United States might have avoided the many pitfalls it experienced in Afghanistan, especially from endemic corruption, if the US government had made anticorruption efforts top priority in contingency operations. The United States should have also developed a shared understanding of the nature and scope of corruption in Afghanistan through intentional political economy and network analyses. Moreover, whether wittingly or unwittingly, alliances with powerbrokers with the aim of achieving short-term gains risk empowering such powerbrokers to initiate and take part in systemic corruption.

South Africa faces many corruption issues in government - from state capture to inflated tenders and power sector corruption. A Joint Standing Committee in Defence (JSCD) report estimates that corruption in the SANDF is rife. The report states that fraud in the SA Army is R1,065 billion, followed by Logistics (R400 million), the SA Navy (R295 million), the Command and Management Information System (CMIS) at R234 million, Joint Operations at R138 million, and the South African Military Health Service (SAMHS) at R58 million. The continuous stay of the SANDF in Mozambique could breed corruption that might make the continuation of the mission a profit for a few in the military and the government. At that point, continuous extensions would be celebrated by 'beneficiaries.128 South Africa can learn from the aforementioned "mistakes" of the US military intervention in Afghanistan to prevent a similar occurrence in Mozambique, and future military missions.

Conclusion

They have got to fight for themselves.129

In the aftermath of the withdrawal of US forces from Afghanistan, President Biden stated that the onus now lies with the Afghan people to fight for the soul of their nation. Biden argued that after spending $1 trillion in twenty years in Afghanistan, it was time for the United States to hand over the process of rebuilding Afghanistan to the Afghan people. The statement could have been prevented if things had been done correctly - if the timeline of the intervention was clear and defined whether the Afghan Army were equipped and capacitated to execute the process of national rebuilding.

Within ten days of the US withdrawal from Afghanistan, the Taliban took control of towns and cities across the country. As can be observed from Figure 3, on 6 August, there were 165 contested provinces, 129 government-controlled areas, and 104 areas controlled by the Taliban. Ten days after the US departure, only 41 sites were contested, and the government-controlled regions reduced significantly from 129 to 12. The Taliban controlled 345 areas against 104 ten days earlier. Twenty years later, the United States left Afghanistan worse than when they arrived.

It is important to restate that the SA mission in Mozambique is a regional effort to stem the spread of terrorism in the SADC region, and not a sole mission of South Africa. However, as stated earlier, South Africa has the most to lose if the conflict in Mozambique snowballs into other countries in the region. The SA mission is therefore national before regional.

South Africa must also assert itself as a regional and continental superpower.131 One of the early challenges that the multinational force in Mozambique faced was a lack of logistics and coordination.132 There seems to be a subtle power tussle amongst contributing nations to the multinational force, although there is an agreement that South Africa will lead the troops of SADC in Mozambique. While knowledge of local geographical and sociopolitical terrain favours the appointment of local military officers - in this case, the Mozambican Army, as coordinators of the intervention - South Africa nonetheless has to play a significant leading role while respecting the territorial integrity of Mozambique. There is no need for political correctness. South Africa is in Mozambique to protect SA interests.

In many ways, the SA military involvement in Mozambique is similar to the Nigerian military involvement with the Economic Community of West African States Monitoring Group (ECOMOG) in Liberia and Sierra Leone in the 1980s and early 1990s. Nigeria bore over 70% of the financial and military cost of sustaining the regional army unit. Years after the war, estimates put the cost of the war for Nigerian taxpayers at almost $8 billion. Beyond the financial burden, Nigeria lost thousands of troops in the wars. However, Nigeria took the decisive lead in the operation, providing most of the ECOMOG force commanders and leading the planning, coordination, and execution of the intervention. It is critical to restate that South Africa - as the primary contributor of troops and logistics to the mission - should take a clear lead in the operation in Mozambique.133

2 Wahhabism advocates a purification of Islam, rejects Islamic theology and philosophy developed after the death of the Prophet Muhammad, and calls for strict adherence to the letter of the Koran and hadith (i.e., the recorded sayings and practices of the Prophet).

80 Joseph Olusegun Adebayo is an NRF-rated media, conflict, and governance researcher in the Journalism and Media Studies department at the Cape Peninsula University of Technology in South Africa.

81 A Chua, Political Tribes: Group Instincts and the Fate of Nations (London: Bloomsbury, 2018). [ Links ]

82 CP Turner, Mozambique: The Cabo Delgado insurgency, Conflict Analysis and Resolution Information Services, 4 January 2021. <https://carisuk.com/2021/01/04/mozambique-the-cabo-delgado-insurgency/> [Accessed on 14 December 2022].

83 CH Vhumbunu, 'Insurgency in Mozambique: The Role of the Southern African Development Community', Accord, 1 January 2021. <https://www.accord.org.za/conflict-trends/insurgency-in-mozambique-the-role-of-the-southern-african-development-community/> [Accessed on 6 December 2022].

84 E Morier-Genoud, 'Tracing the History of Mozambique's Mysterious and Deadly Insurgency', The Conversation, 28 February 2019. <https://theconversation.com/tracing-the-history-of-mozambiques-mysterious-and-deadly-insurgency-111563> [Accessed on 6 December 2022].

85 VOA, 'Officials Say Insurgency in Northern Mozambique is Spreading', 17 December 2021. <https://www.voazimbabwe.com/a/officials-say-insurgency-in-northern-mozambique-is-spreading/6359580.html> [Accessed on 18 January 2023].

86 AfricaNews, 'Southern African nations to send troops to Mozambique', 23 June 2021. <https://www.africanews.com/2021/06/23/southern-african-nations-to-send-troops-to-mozambique/> [Accessed on 6 December 2022].

87 K Moyo, 'South Africa Reckons with Its Status as a Top Immigration Destination, Apartheid History, and Economic Challenges', Migration Policy Institute, 18 November 2021. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/south-africa-immigration-destination-history [Accessed on 15 June 2023].

88 STATS SA, 'Beyond unemployment - Time-Related Underemployment in the SA labour market,' 2023. https://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=16312#:~:text=South%20Africa's%20unemployment%20rate%20in,the%20fourth%20quarter%20of%202022 [Accessed on 15 June 2023].

89 A Sguazzin, 'S. Africa Says Banks to Keep Zimbabweans Accounts Open', Bloomberg, 13 December 2021. <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-12-13/south-africa-withdraws-directive-on-zimbabwe-immigration-permits> [Accessed on 14 December 2022].

90 A Sguazzin, 'S. Africa Says Banks to Keep Zimbabweans Accounts Open', Bloomberg, 13 December 2021. <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-12-13/south-africa-withdraws-directive-on-zimbabwe-immigration-permits> [Accessed on 14 December 2022], 6.

91 A Sguazzin, 'S. Africa Says Banks to Keep Zimbabweans Accounts Open', Bloomberg, 13 December 2021. <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-12-13/south-africa-withdraws-directive-on-zimbabwe-immigration-permits> [Accessed on 14 December 2022], 4.

92 A Sguazzin, 'S. Africa Says Banks to Keep Zimbabweans Accounts Open', Bloomberg, 13 December 2021. <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-12-13/south-africa-withdraws-directive-on-zimbabwe-immigration-permits> [Accessed on 14 December 2022], 4.

93 E Estelle & JT Darden, 'Combating the Islamic State's Spread in Africa: Assessment and Recommendations for Mozambique', Critical Threats, 2021. <https://www.criticalthreats.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Combating-the-Islamic-State%E2%80%99s-Spread-in-Africa.pdf> [Accessed on 23 December 2022].

94 E Estelle & JT Darden, 'Combating the Islamic State's Spread in Africa: Assessment and Recommendations for Mozambique', Critical Threats, 2021. <https://www.criticalthreats.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Combating-the-Islamic-State%E2%80%99s-Spread-in-Africa.pdf> [Accessed on 23 December 2022], 9.

95 E Estelle & JT Darden, 'Combating the Islamic State's Spread in Africa: Assessment and Recommendations for Mozambique', Critical Threats, 2021. <https://www.criticalthreats.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Combating-the-Islamic-State%E2%80%99s-Spread-in-Africa.pdf> [Accessed on 23 December 2022], 1.

96 M Ortega, 'Military Intervention and the European Union', ChallotPaper 45 (2001). <https://www.iss.europa.eu/sites/default/files/EUISSFiles/cp045e.pdf> [Accessed on 21 December 2022].

97 I Mugabi, 'Why UN Missions are Failing in Africa', DW, 2021. <https://www.dw.com/en/why-un-peacekeeping-missions-have-failed-to-pacify-africas-hot-spots/a-57767805> [Accessed on 28 December 2022].

98 M Malan, Peacekeeping in Africa: Trends and Responses. Occasional Paper No. 31 (Pretoria: Institute for Security Studies, 1998).

99 L Miller, 'The Contemporary Significance of the Doctrine of Just War', World Politics, 16, 2 (1964), 254-286.

100 R Cox, 'Expanding the History of the Just War Tradition: The Ethics of War in Ancient Egypt', International Studies Quarterly, 61, 2 (2017), 371-384.

101 BBC, 'Just War: Ethics Guide', 2023. <https://www.bbc.co.uk/ethics/war/just/introduction.shtml> [Accessed on 16 January 2023].

102 J Raines, 'Osama, Augustine, and Assassination: The Just War Doctrine and Targeted Killings', Transnational Law and Contemporary Problems, 12, 1 (2022), 217-243.

103 Agence France-Presse, 'South Africa Possible War Crimes Probed', Voice of America Online, January 2023. <https://www.voaafrica.com/a/s-africa-possible-war-crimes-probed/6911930.html> [Accessed on 16 January 2023].

104 C Malkasian, 'How the Good War Went Bad: America's Slow-motion Failure in Afghanistan', Foreign Affairs, 1, 1 (2021). <https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/afghanistan/2020-02-10/how-good-war-went-bad> [Accessed on 2 January 2023].

105 I Chotiner, 'How America Failed in Afghanistan', The New Yorker Online, 15 August 2021. <https://www.newyorker.com/news/q-and-a/how-america-failed-in-afghanistan> [Accessed on 2 January 2023].

106 T Greentree, 'What went Wrong in Afghanistan?', The US Army College Quarterly, 51, 4 (2021), 7-21. [ Links ]

107 T Greentree, 'What went Wrong in Afghanistan?', The US Army College Quarterly, 51, 4 (2021), 24. [ Links ]

108 A Butt, 'The Afghan War: A Failure Made in the USA', AlJazeera Online, 23 December 2019. <https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2019/12/23/the-afghan-war-a-failure-made-in-the-usa> [Accessed on 10 January 2023].

109 A Cordesman, 'Learning from the War: "Who Lost Afghanistan?" Versus Learning "Why we Lost", Working draft (Washington D.C.: Centre for Strategic International Studies, 2021).

110 F Weigand, 'Why Did the Taliban Win (Again) in Afghanistan?', LSE Public Policy Review, 2, 3 (2022), 5. <https://ppr.lse.ac.uk/articles/10.31389/lseppr.54/> [Accessed on 17 January 2023].

111 F Weigand, 'Why Did the Taliban Win (Again) in Afghanistan?', LSE Public Policy Review, 2, 3 (2022), 5. <https://ppr.lse.ac.uk/articles/10.31389/lseppr.54/> [Accessed on 17 January 2023], 2.

112 F Weigand, 'Why Did the Taliban Win (Again) in Afghanistan?', LSE Public Policy Review, 2, 3 (2022), 5. <https://ppr.lse.ac.uk/articles/10.31389/lseppr.54/> [Accessed on 17 January 2023], 7.

113 Fraym. Using Human Geography Data to Predict Violence in Africa. <https://fraym.io/blog/detecting-vulnerability-with-hg/> [Accessed on 17 June 2023].

114 J Davermont, 'Is There an Ethnic Insurgency in Northern Mozambique?', Fraym Online, January 2023. <https://fraym.io/blog/ethnic-insurgency-nmz/> [Accessed on 12 January 2023].

115 J Davermont, 'Is There an Ethnic Insurgency in Northern Mozambique?', Fraym Online, January 2023. <https://fraym.io/blog/ethnic-insurgency-nmz/> [Accessed on 12 January 2023].

116 Fraym. Using Human Geography Data to Predict Violence in Africa. <https://fraym.io/blog/detecting-vulnerability-with-hg/> [Accessed on 17 June 2023].

117 P. Hiller, Structural Violence and War: Global Inequalities, resources, and Climate Change. In W. Wiist & White (Eds.), Preventing War and Promoting Peace: A guide for Health Professionals (pp. 90-1020), 2017. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

118 J Fearson & D Laitin, 'Ethnicity, Insurgency, and Civil War', American Political Science Review, 9, 1 (2003), 75-90. [ Links ]

119 Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, What We Need to Learn: Lessons from Twenty Years of Afghanistan Reconstruction, 2021. <https://www.sigar.mil/pdf/lessonslearned/SIGAR-21-46-LL.pdf> [Accessed on 18 January 2023].

120 Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, What We Need to Learn: Lessons from Twenty Years of Afghanistan Reconstruction, 2021. <https://www.sigar.mil/pdf/lessonslearned/SIGAR-21-46-LL.pdf> [Accessed on 18 January 2023], 21.

121 Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, What We Need to Learn: Lessons from Twenty Years of Afghanistan Reconstruction, 2021. <https://www.sigar.mil/pdf/lessonslearned/SIGAR-21-46-LL.pdf> [Accessed on 18 January 2023], 18.

122 'South Africa Extends Mission against Mozambique Rebels', Africa News Online, April 13, 2022. <https://www.africanews.com/2022/04/13/south-africa-extends-mission-against-mozambique-rebels/> [Accessed on 18 January 2023].

123 'South Africa Extends Mission against Mozambique Rebels', Africa News Online, April 13, 2022. <https://www.africanews.com/2022/04/13/south-africa-extends-mission-against-mozambique-rebels/> [Accessed on 18 January 2023].

124 Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, What We Need to Learn: Lessons from Twenty Years of Afghanistan Reconstruction, 2021. <https://www.sigar.mil/pdf/lessonslearned/SIGAR-21-46-LL.pdf> [Accessed on 18 January 2023], 21.

125 N Crawford, The US Budgetary Costs of the Post-9/11 Wars: 20 Years of War, Cost of War Research Series, Watson Institute, Boston University, 2021. <https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/files/cow/imce/papers/> [Accessed on 2 February 2023].

126 N Crawford, The US Budgetary Costs of the Post-9/11 Wars: 20 Years of War, Cost of War Research Series, Watson Institute, Boston University, 2021. <https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/files/cow/imce/papers/> [Accessed on 2 February 2023].

127 N Crawford, The US Budgetary Costs of the Post-9/11 Wars: 20 Years of War, Cost of War Research Series, Watson Institute, Boston University, 2021. <https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/files/cow/imce/papers/> [Accessed on 2 February 2023], 33.

128 defenceweb, 'Defence Corruption and Fraud Totals R2.2 billion - Provost Marshal General'. <https://www.defenceweb.co.za/featured/defence-corruption-and-fraud-totals-r2-2-billion-provost-marshal-general [Accessed 18 January 2022].

129 defenceweb, 'Defence Corruption and Fraud Totals R2.2 billion - Provost Marshal General'. <https://www.defenceweb.co.za/featured/defence-corruption-and-fraud-totals-r2-2-billion-provost-marshal-general [Accessed 18 January 2022].

130 BBC, How the Taliban stormed across Afghanistan in 10 days, 16 August 2021. < https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-58232525 [Accessed April 2022].

131 South Africa Extends Mission against Mozambique Rebels', Africa News Online, April 2022. <https://www.africanews.com/2022/04/13/south-africa-extends-mission-against-mozambique-rebels/> [Accessed on 18 January 2023].

132 South Africa Extends Mission against Mozambique Rebels', Africa News Online, April 2022. <https://www.africanews.com/2022/04/13/south-africa-extends-mission-against-mozambique-rebels/> [Accessed on 18 January 2023].

133 C Osakwe & B Audu, 'The Nigerian-led ECOMOG Military Intervention in the Sierra Leone Crisis: An Overview', Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 8, 4 (2017), 107-116.