Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Scientia Militaria: South African Journal of Military Studies

versão On-line ISSN 2224-0020

versão impressa ISSN 1022-8136

SM vol.50 no.3 Cape Town 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.5787/50-3-1381

ARTICLES

Knowledge of, attitudes toward and practices of ethics of war of the officers and soldiers of the Zambia Army

William SikazweI; Eustarckio KazongaII; Evance KalulaIII

IUniversity of Lusaka368

IIUniversity of Lusaka369

IIIUniversity of Cape Town370

ABSTRACT

Since the end of the world wars, the demise of the Cold War and the end of liberation wars in Africa, the changing character of warfare has given birth to uncertainties about how states will respond to acts of aggression in the face of ethics of war, or the moral rules of war. It has become difficult for states to conduct permissible self-defence and other-defence against non-state actors or sub-state groups, which do not have a sovereign (political and territorial integrity) to protect. In the face of this reality, it is not known how much knowledge military personnel world over have on ethics of war, what their attitude towards ethics of war is, and how they practice these ethics of war during war and operations other than war. Research was therefore conducted to assess knowledge of, attitudes toward and practices of the ethics of war of officers and soldiers of the Zambia Army.

A mixed method research was undertaken using explanatory sequential approach. A sample of 420 participants was drawn from officers and soldiers serving in the Zambia Army. Questionnaires were used to collect quantitative data, while focus group discussions and interviews were undertaken to collect qualitative data. The findings from the focus group discussions and interviews provided depth and understanding about how the officers and soldiers felt about ethics of war. The findings of focus group discussions and interviews also helped to explain the findings from the quantitative data.

Quantitative data were analysed at two levels. The first level of analysis comprised descriptive statistics in the form of frequency distribution tables, means and percentages. The second level involved inferential statistics by applying the chi-square test in order to determine the relationship, if any, between the independent variables and the dependent variables using the Statistical Packaging for Social Sciences. Further, the research used Spearman's rank correlation coefficient to measure the strength and direction of association between two ranked variables. Analysis of qualitative data begun during the data collection exercise by arranging the field notes according to salient themes in relation to the objectives. This was followed by pinpointing, examining and recording patterns within the data collected.

The conclusion of the study showed that, at the time, the majority of the Zambia Army officers and soldiers were reasonably acquainted with the knowledge of ethics of war. The study further concluded that Zambia Army officers and soldiers held very strong and positive attitudes towards the ethics of war at the time. In addition, the officers and soldiers also widely accepted and supported the ethics of war, as they considered them beneficial. It was evident from the research that the Zambia Army soldiers and officers practiced the ethics of war extensively and regularly during both local and international operations. However, more needs to be done to increase knowledge levels.

Keywords: just war theory, ethics of war, jus ad bellum, jus in hello, jus post bellum.

Introduction

The world has witnessed an evolution in the character of warfare since the end of the two world wars, the demise of the Cold War and the end of liberation wars in Africa. The changing character of warfare has given birth to uncertainties about how states will respond to acts of aggression in the face of ethics of war, or the moral rules of war, as it is sometimes called. In the past two centuries, the world has seen inter-state wars, the two world wars and a wide range of various types of conventional warfare. Frowe posits that, people have questioned how politicians and soldiers, who are perpetrators of these killings have been praised as heroes. Soldiers returning from wars have been accorded parades where they are decorated and awarded medals for their courage and skills in the battlefield, and generally, adventure seeking children aspire to become soldiers.371

With the demise of interstate wars and the emergence of wars against non-state actors or sub-state groups as the biggest threat to international security, legal scholars and political scientists are therefore re-examining the application of principles of jus ad bellum (justice of war), jus in hello (justice during the war) and jus post bellum (justice after the war). The reasons for resorting to war, the manner in which war is conducted, and the conditions after the end of a war are coming under the microscope. It has become difficult for states to conduct permissible self-defence and other-defence against non-state actors or sub-state groups, which do not have a sovereign (political and territorial integrity) to protect. Worse still, it has become difficult to determine whether to give this kind of aggressor prisoner of war status or not, according to Frowe.

The study on which this article is based, considered ethics of war, which is founded on the just war theory, which is the theoretical foundation of the morality of war. This theory holds that war can sometimes be morally justified, but even when it is justified, the means or methods used to fight a war are still limited by moral considerations, Frowe posits. The origins ofjust war theory can be traced back to St Ambrose and St Augustine. Augustine argued, war was morally justified if it was declared by the appropriate secular authority, if it had a just cause, and if it was fought with rightful intentions. Augustine further argues, a cause was just if it involved fighting to bring about a condition of peace or to punish wrong doers and promote the good. In those olden years, he said, 'intentions were rightful if the prince who waged the war did so with the intent of realizing one or more of these justifying causes'. According to Kansella and Carr, the foregoing conditions were later endorsed by St Thomas Aquinas who revived Augustine's view and built it into his monumental inquiry and into the law of nature, which he understood to govern the relations of human beings. Just like St Augustine, Aquinas was mainly concerned with the just cause of war and argued, 'if a war qualified as just, then everything could be done to bring war to its desirable end'.372

Frowe further posits, 'it is important to understand that 'Just War Theory', which guides ethics of war, has been a perennial concern of political scientists, theologians, philosophers, warriors, military leaders and politicians on the morality of war and its conduct'.373 A number of scholars, such as McMahan and Coverdale have all contended in their discourse that just war theory aims at providing a guide on the right way for states to act in potential conflict situations.374 Christopher and other authors argue that the classical just war theory can be traced back to the ancient civilisations of India, China and Greece.375 However, it resurfaced in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries following the devastating effects of the two world wars, the invention of nuclear weapons, and liberation wars or indeed operations other than war.

Sibamba writes that the Zambia Army has since inception been involved in domestic, regional and international operations.376 At domestic level, the Army was employed to defeat the Adamson Mushala insurgency from 1976 to 1982.377 According to the Zambia Army Archives, the Zambia Army was involved in the liberation wars of Southern Africa from 1965 to 1990.378 Since liberation movements were a potential threat to internal security, Zambia found a just cause to engage in self-defence in accordance with the provisions of the General Customary Law and the UN Charter at Article 51, which give the right of collective and individual national self-defence.379 Zambia further found itself engaged in internal security operations against the Mozambican National Resistance (RENAMO) after Mozambique gained its independence. At the advent of independence of most Southern African States, the focus of the Zambia Army shifted to international engagements towards humanitarian interventions in the area of peace support operations. In most PSOs, Zambian troops were confronted with the obligation to protect the civilian population in accordance with Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter where the use of force is authorised.380

However, despite the involvement of the Zambia Army in these operations, it was still unclear whether the Zambia Army personnel were familiar with the existence of ethics of war or morality of warfare, as evidenced during the conduct of almost all operations undertaken by the Zambia Army during liberation wars, counter-insurgency operations and internal security operations. With a mandatory requirement for all United Nations PSOs to be conducted within the confines of the principles of the ethics of war or morality of war rules, it has become apparent that Zambia Army personnel should have the requisite knowledge on the existence and application of the rules of war. Non-adherence to these rules would make the Zambia Army culpable of committing war crimes or crimes against humanity. It was necessary therefore to undertake the current study to establish:

• how much knowledge officers and soldiers had of ethics of war;

• the attitudes of officers and soldiers towards the ethics of war, practices or adherence to these ethics of war; and

• whether knowledge of, attitudes toward and practices of the ethics of war were related to variables such as gender, formal education, type of service and length of service.

Since it was found that there was little coverage of ethics of war in military schools at the time, this study had to trigger inclusion of the subject into the curriculum. Most important was the contribution to the body of knowledge through innovation of a model to be used by officers and soldiers of the Zambia Army during training and when conducting both conventional and asymmetric warfare, since it is now an ethical requirement and it is also required by law. Further, it was expected the findings of the study would help the country in the formulation of defence policy, military strategy, as well as training and fighting doctrine of the Zambia Army or the Zambia Defence Force. The findings may also ignite interest for future research in ethics of war, especially among scholars of law and military studies.

Research problem

While much research is done globally on ethics of war, little has been done to establish how much is known by the military combatants, about their attitudes towards ethics of war, and whether they are practising these ethics of war during operations. This knowledge gap is conspicuous on the continent of Africa, and more so in Zambia where no or very little research has been done on ethics of war. The legal rules of war authorise a resort to war in self-defence, according to the provisions of the General Customary Law and the UN Charter at Article 51, which give the right of collective and individual national self-defence.381 While the legal dimension of the rules of war have been used by the Zambia Army during military operations, it was not known at the time of the study:

• whether officers and soldiers had knowledge of the ethics of war;

• what their attitudes were towards ethics of war; and

• whether ethics of war were practiced during operations by Zambia Army officers and soldiers.

Other than the knowledge gap, the risk of non-compliance with the ethics of war would be a loss of credibility and potential indictment of Zambia Army personnel for war crimes or crimes against humanity. Above all, it was presumed that the study would help the Republic of Zambia to attain United Nations, African Union and international protocols.

Literature review

In the literature reviewed, theoretical conflict was identified in the interpretation of just war theory itself and the number of scholars who have questioned its reliability, especially in modern times. As highlighted in the literature, scholars, such as Babic, argue, 'the Just War Theory has very deep flaws in that it criminalizes war, which reduces warfare to police action, and finally implies a very strange proviso that one side has a right to win'.382 McMahan and other writers who bring out this theoretical conflict argue that the concern of just war theory was with a rather pure conception of right and wrong.

These researchers posit that this conception of right and wrong made few concessions to pragmatic considerations. They were however unwilling to compromise matters of principle for the sake of considerations of consequences.383 The arguments by the researchers offered an interesting line of inquiry using qualitative methods to determine whether members of the Zambia Army agree with these writers.

Another notable gap identified in the literature referred to a knowledge void. More specifically, this gap involved scarcity of literature, including literature from related research domains that focused on different demographics. In earlier studies, such as by Kelly and other authors, the focus has been mainly on Western wars conducted mostly in the Middle East.384 However, despite this great work, none of these prominent authors give much detail on the African context. It was therefore clear that the just war theory in the African context needs further study in order to narrow the knowledge gap. Further, despite intense philosophical debate regarding ethics of war theories, little work has been done on whether a soldier has adequate knowledge of the moral dimension of war. Watkins and Goodwin, for instance, state that, across nine studies, they found consistent evidence that the judgments of ordinary individuals of soldiers' actions are influenced by the justness of the soldiers' causes, contrary to the principle of combatant equality as postulated by the just war theory and Western scholars.385 This finding suggests further existence of provocative exceptions and contradictory evidence that was interrogated by this research.

Following a critical review of literature, another gap was identified by the researcher, namely a methodological gap. This gap is in the conflict with the research methods used in prior studies, and was mainly explored using a singular or common method. From the literature reviewed, this researcher found no literature that had used mixed methods to examine knowledge of, attitudes toward and practices of the ethics of war. The most vigorous literature found was a comparative study conducted by Verweij, Hofhuis and Soeters to assess the moral judgment of Dutch officers, officer candidates and university students.386 However, this study was quantitative by nature and was done among military men and women using four dilemmas: two standard ethical dilemmas and two specific military dilemmas based on experiences from military practice, developed by the researchers. Given the fact that the structure of the test conducted by these researchers left many moral considerations undisclosed, they recommended the use of their test in combination with a qualitative research methodology.387

In addition to using mainly quantitative methods, very few scholars have used military population in their studies. As an exemption in the literature reviewed, the thesis by De Graaff is based on a military population from which the sample was drawn. De Graaff considered empirical studies of individual moral assessment of servicemen in practice. She equally used both qualitative and quantitative research methods in her study. However, her study was based on operational situations and excluded non-operational situations, which De Graaff herself acknowledges as a methodological weakness.388 McAlister et al also provide good comparisons in their study where the sample population comprised soldiers. However, the weakness of this latter study is that the survey was limited to students in selected schools and thus not broad enough to generalise findings.389 Overall, gaps in the literature reviewed are seen not only in the theory itself, but also in research methodology and population.

Methodology

The explanatory sequential mixed methods design was used in this study. This design is an approach in mixed methods that involves a two-phase project in which the researcher collects quantitative data in the first phase, analyses the results, and then uses the results to plan or build on to the second phase of qualitative data collection and analysis. The quantitative results inform the types of participants who have to be selected purposefully to participate in the qualitative phase. This has a considerable influence on the questions asked to the respondents. Qualitative data actually helps to explain the quantitative results in detail. The first two phases are then triangulated into a third phase where quantitative data provide general patterns and width, while qualitative data provide experience and depth to the study. The findings from qualitative phase help to contextualise and enrich the findings, increase validity and generate new knowledge, explains Creswell.390

In this study, the researcher applied a cross-sectional descriptive survey design during the quantitative phase, as data collected from a cross-section of officers and soldiers were representative of all rank structures for the study. The study was descriptive and specifically focused on the Zambia Army. Descriptive research attempts to describe, explain and interpret conditions of the present, according to Creswell.391 The main purpose of descriptive research is to examine a phenomenon that is occurring at a specific place and time. It is concerned with conditions, practices, structures, differences or relationships that exist, opinions held and processes that are going on or trends that are evident,392 . This was the most appropriate research design for this study to investigate knowledge of, attitudes towards and practices of officers and soldiers of Zambia Army. The study examined the phenomenology of ethics of war, conditions under which this is practiced, as well as the experiences and opinions of personnel of the Zambia Army regarding this phenomenon.

Participants in the research

The population comprised commissioned officers and non-commissioned officers serving in the Zambia Army. The target population comprised officers and soldiers from ten fighting units of the Zambia Army. Due to the nature of the institution under study, the actual population was not given for security reasons. Nevertheless, the Cochran formula, which uses proportions of p and q, was used, as recommended by Cochran in his literature on sampling techniques,393 to determine the target population, which was a subset of the population for the purpose of the study. The calculation to determine sample size is explained in the next paragraph for ease of understanding. A total of420 respondents were given questionnaires but only 413 participated in the study during the quantitative stage. During the qualitative stage, the number was small, as only 15 participants from each of the three provinces selected for the purpose based on convenience, were involved in focus group discussions, while three former army commanders participated in the interview.

Sample size determination

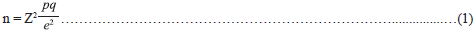

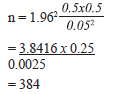

Phenomenological studies normally target smaller populations of not more than 50. In this study, the phenomenological approach therefore targeted a qualitative dimension of not more than 50 respondents who participated in focus group discussions and personal interviews. The sample size for the quantitative dimension was determined by using a population determination formula, while questionnaires were used for collecting data for this purpose. Cochran developed a formula for large populations, which yields a representative sample for proportions.394 This study used the following Cochran formula to determine the appropriate sample size:

where:

n = sample size required

Z = 1.96 for a 95% confidence interval using a Z-table E = the specified margin of error (± 5)

p = an estimate of the proportion of the population that has a characteristic of interest

q = an estimate of the proportion of the population that does NOT have a

characteristic of interest q = 1-p since p + q = 1.

The maximum variability is obtained when p = 0.5.

Therefore:

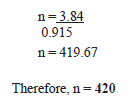

Assuming an 8.5% non-response rate

Sample size

Both probability and non-probability sampling techniques were used in this study. From the population of officers and soldiers, 420 participants were randomly selected from the ten fighting units, forty-two from each unit, and subjected to the questionnaire. The officers and soldiers who were selected to respond to the questionnaire were drawn from across all the ranks in the Zambia Army from the lowest rank of private to that of colonel. The two ranks of major general and lieutenant general were exempted from answering the questionnaire during quantitative data collection, as these two ranks were only held by the two most senior officers of the Zambia Army. Additionally, it was difficult to get the rank of brigadier general due to their national duty commitments. During collection of qualitative data, two four-star generals and one three-star general however participated in personal interviews.

Data collection

Field research was the main source of data collection. Structured questionnaire was designed and given to selected participants. Focus group discussions were arranged in selected provinces, and participants interacted to share experiences and opinions. Additionally, an interview guide was used and personal interviews were conducted with key participants in order to maintain the focus and relevance of the study.

Data analysis

Quantitative data were analysed at two levels. The first level of analysis was descriptive statistics in the form of frequency distribution tables, means and percentages. The second level involved inferential statistics by applying the chi-square test in order to determine the relationship, if any, between the independent variables and the dependent variables using the latest version of the Statistical Packaging for Social Sciences (SPSS 16.0). Data were further subjected to Spearman's rank correlation coefficient analysis to measure the strength and direction of the relationship among the independent and dependent variables further.

In the study, analysis of qualitative data began during the data collection exercise by arranging the field notes according to salient themes in relation to the objectives. This was followed by pinpointing, examining and recording patterns within the data collected. This type of thematic content analysis was used in the study because of its relevance to the description of a phenomenon and its association with a specific research question. This method of analysis was also tied to the specific theory on which the ethics of war is grounded. Thematic content analysis allowed for a rich, detailed and comprehensive description of data that were collected during the study. This led to a fuller understanding of research findings. Qualitative stage findings explained the results of the quantitative strand of the study.

Findings and perception

The study was able to establish the knowledge of, attitudes toward and practices of ethics of war of officers and soldiers of Zambia Army. The findings and perception about the findings are discussed in the following paragraphs:

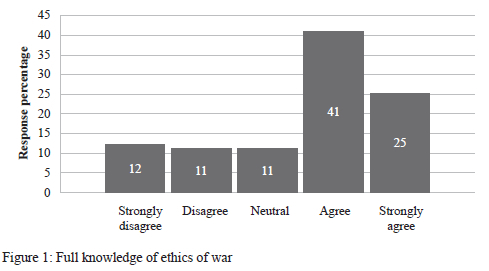

Knowledge

In order to establish whether officers and soldiers of the Zambia Army had knowledge about ethics of war, the respondents involved in the study were assessed based on their own experiences and the extent to which they believed that they were fully knowledgeable about the ethics of war. The study findings showed that 41% of the respondents agreed to having full knowledge of the ethics of war, and 25% agreed strongly. Of the officers, 66.0% affirmed that they were fully knowledgeable in terms of the ethics of war. A further 11.0% of the respondents were neutral (i.e. neither agreeing nor disagreeing), while another 11.0% disagreed, and 12% strongly disagreed to being fully knowledgeable. These findings showed that the majority of the officers and soldiers felt that they had full knowledge of the ethics of war. A lack of certainty in 11% and disagreement by 23% of the respondents meant that there was a need to up-scale knowledge levels of officers and soldiers in the Zambia Army. Figure 5.1 reflects statistical details in this regard.

In the Zambia Army, officers and soldiers are normally expected to possess a thorough grounding in knowledge of the ethics of war that would help them conduct themselves professionally during local and international operations. In this vein, the study revealed that, at the time, most of the officers and soldiers actually understood the fundamental principles of the ethics of war, with their predominant sources of information being the military schools and pre-deployment programmes. The military schools as source of information conducted scheduled training for the officers and soldiers based on a standard curriculum. The curriculum was broad-based and exposed trainees to various aspects of the military. However, although the curriculum used by the Army at the time was being well taught, it did not contain a comprehensive coverage of the ethics of war compared to the pre-deployment training to which the officers and soldiers had been exposed before being deployed on international operations. Unfortunately, pre-deployment training was also seldom allocated ample time to enable the officers and soldiers to be thoroughly trained to prepare them for deployment to foreign countries.

During the study, the officers and soldiers expressed the levels of their knowledge of the ethics of war by correctly identifying and articulating the principles of the ethics of war. It was clear that the majority of officers and soldiers had at least a fundamental understanding of the ethics of war. They were able to recognise that it was -

• ethical to use war for self-defence;

• ethical to declare war with the right motive or cause;

• ethical to declare intention before starting a war;

• ethical for legitimate authority only to declare a war; but

• unethical to kill non-combatants.

Unfortunately, many of the officers and soldiers failed to recognise that it could be ethical to use war as a means to enhance or promote peace.

Attitudes

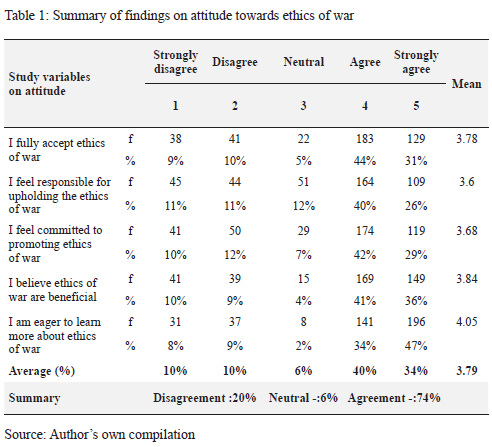

One of the key issues of the study was to assess the attitudes of officers and soldiers towards the ethics of war. Five questions were appropriately designed into the questionnaire to enable the assessment of the attitudes towards the ethics of war in the Zambia Army. The study found that 74% of the Zambia Army officers and soldiers showed positive behaviour towards the ethics of war. This was buttressed by the computed grand mean of 3.79, which was way above the average Likert scale value of 3. The results on the other hand, showed a proportion of the officers and soldiers (20% disagreement) not expressing satisfactory attitude towards the ethics of war. It was also observed that only 6% of the respondents were disinterested in stating their exact attitude; hence, choosing to remain neutral. These findings entailed that the majority of the officers and soldiers of the Zambia Army demonstrated a positive attitude towards the ethics of war, which might be attributed to the levels of knowledge acquired.

Ethics of war are widely accepted as a norm in the Zambia Army by both officers and soldiers who maintain a positive posture towards ethics of war. Most officers and soldiers fully accept the ethics of war, feel personally responsible to uphold the ethics, and feel committed to promoting it. Generally, the Zambia Army officers and soldiers believe that the ethics of war are beneficial to them and they are therefore eager to learn more about these ethics. Some of the fundamental factors that were seen to affect the attitudes of officers and soldiers toward the ethics of war included their religion, level of formal education attained as well as length of service. This study was however not able to provide evidence to show that the acceptance of the ethics of war was directly influenced by the type of service in which the soldiers and officers were involved (whether commissioned or non-commissioned). Table 1 provides statistical details in this regard.

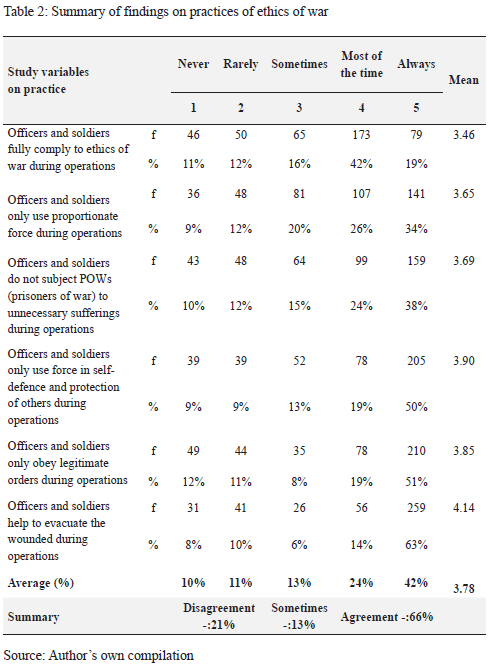

Practices

To assess how the ethics of war were being practiced by Zambia Army officers and soldiers during their operations, a different five-point Likert-type scale was used in which: 1=Never, 2=Rarely, 3=Sometimes, 4=Most of the time and 5=Always. The findings showed that the majority of respondents (66%) agreed that the Zambia Army officers and soldiers practiced the ethics of war during their operations compared to 21% of the respondents who disagreed. This was further supported by the computed grand mean value of 3.78, which was above the Likert scale threshold of 3. Only about 13% of the respondents believed that the ethics of war were occasionally practiced by Zambia Army officers and soldiers during their operations.

While the study gave a positive outlook in terms of how knowledgeable the officers and soldiers of the Zambia Army were at the time, 34% of respondents were not sure whether they had knowledge of ethics of war and the percentage of those who thought they actually did not have the knowledge was too big to be ignored (i.e. 21%).Table 2 shows statistics of various variables that were studied to establish whether officers and soldiers of Zambia Army practiced ethics of war. Details in form of frequencies, percentages and mean give statistics of compliance to ethics of war, use of proportionate force and how officers and soldiers of Zambia Army treat prisoners of war and the wounded. The findings on practices revealed that there was a need to give more information on principles of the ethics of war to officers and soldiers. This should be done by increasing coverage of the ethics of war in the curriculum at military schools and also by conducting seminars in units. Table 2 gives statistical details on practices of ethics of war.

Perception

Findings from the current research support most of the views by various authors in literature in terms of the need for adequate knowledge in ethics of war. Examining the need for soldiers to have adequate understanding of the moral law, Whitman, Haight and Tipton395 refer to the events of 16 March 1968 when C Company of Task Force Barker of the American Forces in Vietnam entered My Lai, a suspected enemy stronghold and killed over 500 civilians.396 These figures consisted mostly women, children and the aged who were found by the American Forces after their search mission. The search is reported not to have found any enemy soldiers. This event, the authors point out, more than any other event in the Vietnam War, had a profound influence on the United States Army for years to come. It became, and still is today the centrepiece of just war theory at all levels of army training, according to the authors. As a result of the massacre at My Lai, all soldiers in the United States Army get at least some instructions on the laws of land warfare (found in The Hague and Geneva conventions) and the just war theory that undergirds these laws. Their views underscore the importance of mainstreaming just war in the training curricula for military personnel.397

Kelly,398 like other American scholars on ethics, confirms from his research and studies, American Military officers throw ethics of military to the wind for the sake of their career. He claims professional ethics suffer for the purpose of enhancing chances of career progression and praises from authorities. According to Kelly, the United States Army has not progressed far enough in resolving problems in professionalism and ethics. He argues that, improvement to the ethical climate of the military requires two significant changes. He says first change involves the philosophy of leadership held by senior officers; and the second involves internalization of the Army's ideal values of honesty, and integrity as subsumed into the perceived motto of duty, honour and country'.

Kelly concludes that the subject of ethics in the United States Army is moderately covered, and he recommends wide coverage of military education in ethics as the best way to improve ethics in the military profession.399 During this study, similar experiences were reported by officers and soldiers of the Zambia Army during focus group discussions. This research also confirmed the views of Whitman, Haight and Tipton that there is a requirement to cover ethics of war at all levels of training at military schools in order to fill the gaps of knowledge that were identified during this study.400 When it comes to the Zambia Army, many activities have been undertaken to modernise the structures and equipment. Efforts have been made to review the core values, the vision and the soldiers' creed, which have been included in order to instil in officers and soldiers a spirit of patriotism and unity. Internalisation of the values of discipline, personal courage, duty, loyalty, respect, selfless service, professionalism, integrity, godliness and esprit de corps is what is guiding the Zambia Army today.

From the reviewed literature, it was evident that, although a certain level of knowledge existed among the officers and soldiers, more still needs to be done to minimise violations of the ethics of war. This should be generalised, as it may not just be unique to the Zambia Army, but applies in Africa and beyond.

From the literature reviewed, the assessment of the attitude towards ethics of war by the study found the same pattern of acceptance to abide by these ethics. In his article, Simonovic writes about attitudes and types of reaction toward past war crimes and human rights abuses. He argues that, attitudes cannot be directly observed but they can be identified only on the basis of various indicators. He posits that, individuals, societies, and various international actors can and usually do have different attitudes toward past war crimes and human rights abuses.Simonovic further states that the most interesting part of his study are the prevailing attitudes, which are the ones that are supported by the dominant political forces within the post-conflict or transitional society itself.401

McAlister et al402 conducted research with the objective of studying the cultural differences in moral disengagement, which lends support to attitudes used to justify violence. They studied five countries, and wrote a report, which was reviewed during this study because it involves the study of attitude, which is one of the variables investigated during this study. According to this group of researchers, aggressive responses to intergroup and international conflicts are partly determined by processes of moral disengagement. Their argument is that, through these processes, the perpetration of violence against potential victims is made acceptable by the expression of attitudes that influence personal and collective judgments of choices for resolving conflicts by acts of aggression. They posit that when moral disengagement occurs, violence is justified by invoking 'rights' or 'necessities', which provide excuses for the infliction of suffering upon others.403 The officers and soldiers who participated in this study also mentioned a negative attitude against war crimes and human rights abuses experienced during operations. From their participation in liberation wars, the operation against RENAMO, and the counterinsurgency operations against Adamson Mushala, they have learnt lessons where they felt certain actions might not have been taken if they had knowledge on the ethics of war. It was clear in their minds that future operations should be guided by principles of ethics of war.

The findings of this research are in agreement with those by Gilman404 who identifies the importance of the legal setting in the practice of ethics and enforcement of ethical codes of conduct. In his work, "Ethics codes and codes of conduct as tools for promoting an ethical and professional public service", Gilman maintains that law, regulation and parliamentary or executive orders are a critical part of an ethics regime. This is because law is seen as the basis for ethics or code of standards that are embodied not only as law, but also seen as laws that are effective.405 Zambia's being state party to the Geneva Convention has implications significant for the behaviour of the Zambia Army officers and soldiers during their operations, including their conduct with respect to the ethics of war. It was established during this research that the Zambia Army officers and soldiers acknowledge their obligation to practice the ethics of war by conducting themselves within the norms of international law, including the Geneva Convention. At the time of this research, it seemed that Zambia Army's officers and soldiers have maintained an impeccable track record of ethical conduct in their international operations.

According to the findings of this research, the majority of officers and soldiers tend to practice the ethics of war during their local and international operations. Some of the principles commonly upheld by officers and soldiers in practicing the ethics of war include proportionate use of force, not subjecting POWs to unnecessary suffering and only resorting to apply force in circumstances that justify either self-defence or protecting other people from harm. In addition, at the time of this research, the Zambia Army officers and soldiers were able to demonstrate their ability to apply the ethics of war correctly by obeying legitimate orders given to them by their superiors and by helping to evacuate the wounded. But despite the officers and soldiers being seen to practice the ethics of war to a significant degree, the quality of their practice could be enhanced if the Zambia Army would take measures aimed at promoting knowledge acquisition through means such as allocating more time to pre-deployment training and engaging more officers and soldiers in international operations. Pre-deployment training and actual deployment of the officers and soldiers provide rare opportunities for officers and soldiers to apply themselves to the ethics of war.

The Mushala Insurgency, RENAMO encounters and liberation wars, mentioned as background to this article, give insight about the changing operation environment, which has evolved from the traditional conventional warfare to asymmetric warfare. Although the aforementioned operations by the Zambia Army were not the modern type of terrorist actions, they still have a similarity in the sense that these activities were conducted by non-state actors and the targets were civilians. Although the Zambia Army engaged in warlike operations against the Mushala and RENAMO armed groups, these operations did not fall under international armed conflict but under internal armed conflict. The reason was that Mushala rebels were conducting their operations in order to express their discontent and to change the government of Zambia, while the RENAMO rebels - although coming from another country - were conducting their operations in order to get weapons and logistics to sustain their operations against the ruling government in Mozambique. The ethics of war were applicable to the Mushala and RENAMO armed groups as well since this was a moral issue, which was not based on legal dimensions. The Mushala and RENAMO armed groups could be indicted under the International Humanitarian Law because their activities could be termed as internal armed conflict. Conversely, the liberation wars could be termed international armed conflict since the war was between one state and another under the disguise of attacking liberation camps by one state, and self-defence by the other. Despite the study findings showing that knowledge, attitude and practices of ethics of war were reasonably good, it was clear that much was not known about the ethics of war during the aforementioned operations. Personal interviews and focus group discussions revealed events and activities that were against the ethics of war in the Mushala and RENAMO operations. This could be attributed to a lack of knowledge, which led to a negative attitude and a lack of practice of the ethics of war. The officers and soldiers now have reasonable knowledge about the ethics of war because of pre-deployment training for international peacekeeping operations with a bias on legal aspects of international humanitarian law.

The current research gives hope for a peaceful future by way of its findings that the attitude of officers and soldiers is positive. This provides fertile ground for adherence to the ethics of war in the sense that officers and soldiers of the Zambia Army are willing to acquire knowledge in the ethics of war. Further, it is reassuring that the research established that the majority of officers and soldiers are practicing the ethics of war when conducting their operations. Attitude and practice are important prerequisites for the adherence to the ethics of war, and it is gratifying that officers and soldiers of the Zambia Army have these attributes. The research brought about a new understanding that generally, officers and soldiers have varying degrees of knowledge of the ethics of war. They have reasonable knowledge about the principles of the ethics of war and the consequences of not adhering to the requirements ofjus ad bellum and jus in bello. During the study, it was observed that acceptance of the ethics of war was to some extent influenced by religious beliefs, which could be dealt with in the curriculum of ethics of war for all military schools and during pre-deployment training. Issues of religion are sensitive, especially when it comes to global security, and this subject therefore requires a full study in order to understand how religion influences the ethics of war. The attitude of officers and soldiers towards ethics of war is positive, and this contributes to good practices during operations. However, the military world over would further enhance adherence to the ethics of war if the subject was widely covered at all levels of training in military schools. Seminars and conferences to discuss the ethics of war would also help by enhancing adherence to ethics of war.

Research benefits

Based on the findings, a model for improving knowledge of, attitudes toward and practices of the ethics of war of officers and soldiers serving in the Zambia Army has been developed. The model could be used starting from the recruitment stage of both officers and soldiers. Candidates could be required to meet set requirements on recruitment, and would start the ethics of war curriculum as officer cadets and recruits at their training academies and centres. The curriculum will be progressive as the officers and soldiers do their career progression. The model has been well designed such that it involves monitoring and evaluation at all stages of their career courses. The model will therefore assist in filling the knowledge gap that triggered this research. In addition, the findings will assist in formulating policies and strategies by the Ministry of Defence and the Zambia Defence Force. A manual could also be developed that would explain how the model will be operationalised.

Conclusion and recommendations

The general conclusion from both the quantitative and qualitative findings of the research was that, at the time, the majority of the Zambia Army officers and soldiers were reasonably acquainted with the knowledge of ethics of war. This knowledge of the ethics of war is acquired locally from the few available military schools, and training they undergo before being deployed for operations (United Nations pre-deployment training). Lastly, it was to some extent observed that officers' and soldiers' acceptance of the ethics of war seemed to be influenced by religious beliefs, which must be covered adequately in the curriculum and during pre-deployment training.

At the time of this research, it seemed that the attitudes of officers and soldiers towards the ethics of war were being affected by factors such as gender, level of education, length of service and type of service, although details of the variable relationships have not been included in this article.

Correct application of the ethics of war by most of the Zambia Army officers and soldiers was noted. Some of the factors that could have limited the application of the ethics of war during operations include, among many, the lack of a clear understanding of the ethics of war by some of the officers and soldiers as well as inadequate coverage of ethics of war in the curriculum at military schools.

The following recommendations are made based on this research:

• The Zambia Defence Force should consider creating an up-to-date staff development policy that would enable it to make adequate investment in staff development programmes and to motivate more officers and soldiers to upgrade their formal education to at least diploma or equivalent. This would indirectly build capacity in the officers and soldiers to acquire knowledge of the ethics of war.

• The selection of officers and soldiers to be deployed on operations should be based on certain criteria to ensure knowledgeable personnel are nominated to participate. Conduct during the operations should be evaluated at the end of the mission as an after action review (AAR) in order to draw lessons and identify weaknesses that need to be reviewed in the curriculum.

• The Zambia Defence Force should modernise its curriculum being taught in military schools. The curriculum should be updated with relevant theories and concepts of the ethics of war and consequences for non-adherence. In addition, important aspects of international law, culture and geography should be incorporated to broaden the understanding of the officers and soldiers, which could be a significant factor in making them adaptable to various operational environments. Further, the curriculum should be benchmarked so that the Zambia Defence Force curriculum is standard and more generic to the ethics of war curriculum of Defence Forces in other countries in order to avoid knowledge gaps.

368 William Sikazwe is the current Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the Republic of Zambia to the Republic of Turkey. He has been a military career officer in Zambia Army for 36 years and retired at the rank of Lieutenant General. He held several command and staff appointments before he was appointed as Army Commander and awarded Grand Commander of the order of Distinguished Service. He served with the United Nations Peacekeeping operations in Angola before serving in Darfur with the African Mission in Sudan. He is a holder of Doctor of Philosophy Degree in Ethics.

369 Eustarckio Kazonga is a professor of Health Sciences Biostatistics at the University of Lusaka. He was educated at the University of Zambia, Limburgs University-Belgium, and the University of the Western Cape in South Africa in the fields of Mathematics, Statistics, Biostatistics and Public Health. He is a Fellow of the Royal Statistical Society and a Member of the Institute of International Statistical Institute (ISI). He is the Interim Vice President of the Statistics Association of Zambia (SAZ). He also once served as Deputy Minister of Defence, Minister of Local Government and Housing, and Minister of Agriculture and Cooperatives in Zambia.

370 Evance Kalula is Chairperson of the ILO Committee on Freedom of Association (CFA). He is Emeritus Professor of Law at the University of Cape Town and Honorary Professor at the University of Rwanda. He is a fellow of the African Academy of Sciences (AAS), Zambian Academy of Sciences and the Stellenbosch Institute for Advanced Study (STIAS). He is a member of Council of the Academy of Science of South Africa (ASSAf). He serves as Executive Policy Advisor at the University of Lusaka (UNILUS). He ispast President of the International Labour and Employment Relations Association (ILERA).

371 F Frowe. The ethics of war and peace: An introduction. New York, NY: Routledge, 2011, 711.

372 D Kinsella and CL Carr. The Morality of War: A Reader. Colorado, Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2007.

373 F Frowe. op. cit.

374 This group of authors include J McMahan. "The ethics of killing in war". Ethics 114/4. Symposium on Terrorism, War and Justice. July 2004, 693 - 733. JF Coverdale. "An introduction to the just war tradition". Article, Pace international Law Review Journal, XVI/II. 2004, 222 - 276.; E Brits. Just war theory and non-state actors. Auburn, AL: Auburn University Press, 2012.

375 P Christopher. The ethics of war and peace: An introduction to legal and moral issues (3ed). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, NJ: Pearson Education, 1999.

376 FG Sibamba. The Zambia Army and I: Autobiography of a former army commander. Ndola: Mission Press, 2010.

377 Ibid.

378 Zambia Army Archives, n.d.

379 International Committee of the Red Cross. Customary international humanitarian law. NewYork, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2005. [ Links ]

380 Ibid.

381 Ibid.

382 J Babic. Ethics of war as a part of military ethics. Brill Nijnoff, Laden Boston, 2016, 120 - 126.

383 The other authors who have contributed to this subject include J McMahan. The ethics of killing in war. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 1994; MT Beard. "War rights and military virtues: A philosophical re-appraisal of just war theory". PhD dissertation. University of Notre Dame Australia, 2014; BA Valentino. "Just war and unjust soldiers: American public opinion on the moral equality of combatants". Ethics & International Affairs 33/4. 2019. 411-444.

384 Another group of authors to these arguments includes TE Kelly. "Ethics in the military profession: The continuing tension". In J Brown & MJ Collins (eds), Military ethics and professionalism: A collection of essays, Washington D.C. National Defence University Press, 1981; R Gribble Wesley, S Klein, DA Alexander, C Dandeker and NT Fear. "British public opinion after a decade of war: Attitudes to Iraq and Afghanistan, 2014, 128 - 150. D Owen. "Refugees, fairness and taking up the slack: On justice and the international refugee regime". Moral Philosophy and Politics 3/2. 2016. 141-164; D Öberg. "Ethics, the military imaginary, and practices of war". Critical Studies on Security 7/3. 2019. 12; A Bousquet, J Grove and N Shah. "Becoming war: Towards a martial empiricism". Security Dialogue 51. 2020. 118 -99. doi: 10.1177/0967010619895660.

385 HM Watkins & GP Goodwin. "A fundamental asymmetry in judgments of soldiers at war". Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 149/3. 2020. 419-444. [ Links ]

386 D Verweij, K Hofhuis & J Soeters. "Moral judgement within the armed forces". Journal of Military Ethics 6. 2007. 19-40. [ Links ]

387 Ibid.

388 MC de Graaff. Moral forces: Interpreting ethical challenges in military operations, Doctoral Thesis, Universiteit Twente, 2017.

389 A McAlister P Sandstrom, P Puska, A Veijo, R Chereches and L Heiddmets, . "Attitudes of youth in five countries towards war and killing". Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 2001.

390 JW Creswell. Educational Research. New Jersey: Upper Saddle River, 2002. [ Links ]

391 Ibid.

392 Ibid.

393 Cochran, W. G. (1977). Sampling techniques. 3rd Ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

394 Ibid.

395 JP Whitman, CG Haight & PE Tipton. "Citizens and soldiers: Teaching just war theory". Teaching Philosophy 17/1. 1994. 29-39.

396 Ibid.

397 Ibid.

398 Kelly, T. E. (1981). Ethics in the Military Profession: The Continuing Tension. ed. James Brown and Michael J. Collins.

399 Ibid.

400 Whitman et al. op. cit.

401 I Simonovic. "Attitudes and types of reaction toward past war crimes and human rights abuses". Yale Journal of International Law, 29. 2004. 343.

402 McAlister, A. e. (2001). Attitudes of youth in five countries towards war and killing. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 111 - 165.

403 Ibid.

404 SC Gilman. "Ethics codes and codes of conduct as tools for promoting an ethical and professional public service: Comparative successes and lessons". Prepared for the PREM. Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2005.

405 Ibid.