Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Scientia Militaria: South African Journal of Military Studies

On-line version ISSN 2224-0020

Print version ISSN 1022-8136

SM vol.50 n.2 Cape Town 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.5787/50-2-1370

ARTICLES

Safe and optimistic: Experiences of military members after the first repatriation of South Africans during the Covid-19 pandemic

Danille Elize Arendse1

Military Psychological Institute, SANDF, Department of Psychology, University of Pretoria

ABSTRACT

The Covid-19 pandemic presented a period of unprecedented uncertainty. The repatriation of South African citizens from Wuhan was a first for the South African government. These special circumstances of risk presented a unique opportunity to explore experiences of military members who were at the frontline. The primary aim of this study was to investigate the experiences of South African National Defence Force (SANDF) members involved in the first South African repatriation of its citizens due to the Covid-19 crisis. This included aspects such as possible stigma, perceptions and emotions towards Covid-19, repatriation, and quarantine experienced by the SANDF members. A quantitative research approach was adopted for this study. The exploratory study used purposive sampling to include only military members involved in the first South African repatriation and quarantine procedure for the Covid-19 pandemic. The research sample comprised 13 SANDF regular force members of whom 85% had tertiary qualifications. These military members were asked to complete informed consent forms and a newly created questionnaire, the Stigma and Related Matters Questionnaire. A reliability, correlation and frequency analysis was performed through SPSS. Cronbach's alpha indicated high reliability and several strong relationships among the statements. The findings indicated that the military members involved in the return and quarantine of repatriated South Africans, were mostly positive and supportive of virus containment measures and lockdown practices. Military members did not report holding any stigmatising or discriminatory beliefs around Covid-19. These responses are in contrast with literature from other countries where people reported experiencing severe discrimination. The current responses however also support literature that reports positive perceptions on virus containment measures. More research is recommended as the Covid-19 pandemic persists in South Africa.

Keywords: Covid-19, South Africa, repatriation, stigma, South African National Defence Force.

Introduction

The SANDF undertook mercy missions to repatriate our citizens abroad, who were fearful and wanted to be reunited with their families ... you have demonstrated that the SANDF can be relied on in good and bad times, in times of peace and times of war, in times of stability and prosperity, and in times of crisis (Ramaphosa, 2021, n.p.).

The Covid-19 pandemic presented a period of unprecedented uncertainty and a wave of social issues. Months after Covid-19 had first appeared in Wuhan, China (Kawuki et al., 2021); South Africa was faced with the Covid-19 pandemic within its borders. For this reason, South Africa chose to act, and decided to impose a national lockdown and to repatriate its citizens from abroad. This national lockdown was implemented to decrease the spread of infections and to prepare the health care system to accommodate advanced cases of the virus. This national lockdown took a phased approach, which comprised five levels depending on the severity of Covid-19 infections. Part of the national lockdown was the repatriation of South Africans from Wuhan (Kawuki et al., 2021).

Covid-19 placed a considerable strain on society and all facets of life (Lohiniva et al., 2021). The practices of quarantine and self-isolation and the national lockdown were all implemented in order to contain Covid-19. Such practices could however cause psychological distress because of the fear, anxiety and uncertainty they impart (Lohiniva et al., 2021). Repatriation was regarded as important because it would alleviate South Africans of the psychological effect of Covid-19 and a strict lockdown imposed by Wuhan. It was also seen as a means by which the South African government could protect its people and bring them home to safety and their loved ones. Through the repatriation, trust and belief in the South African government was sparked as similar actions were taken by other countries across the world (Kawuki et al., 2021). Although repatriation is an essentially well-intentioned action, there are negative consequences for repatriated persons and health care workers. These consequences include stigma, discrimination, social exclusion, mockery and insults (Kawuki et al., 2021).

The Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) conducted studies in 2020 at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic in South Africa. The focus of these surveys was on the knowledge and awareness South Africans had of Covid-19 as well as on assessing the effect that the national lockdown had on South Africans (Dukhi et al., 2020; HSRC, 2020; Turok & Visagie, 2020). Some of their findings indicated that the lockdown affected individuals in predominately informal settlements who suffered from hunger and a lack of income due to an increase in unemployment. Additionally the lockdown restricted informal businesses from generating an income (Dukhi et al., 2020; HSRC, 2020; Turok & Visagie, 2020). Overall, despite the problems above, the research found that most people had positive attitudes towards self-isolation, and they adhered to the national lockdown regulations (Dukhi et al., 2020; HSRC, 2020).

A different study by De Quervain et al. (2020) considered the influence of the lockdown on the mental health of Swiss people. Their findings indicated that the lockdown had created numerous burdens, such as school and work changes, problems with childcare, people living alone, thinking about the future, limited free movement, increased reliance on digital media and class teachings, and a decrease in socialising. The effect of these burdens led to an increase in stress for individuals (De Quervain et al., 2020).

The impact of Covid-19 on mental health was also investigated in China (Wang et al., 2020). It was found that a large number of people suffered from depression and anxiety, with a few individuals experiencing severe depression and anxiety due to Covid-19 (Lohiniva et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2020).

Another study found that, in extreme cases, there were a few suicide cases due to the Covid-19 pandemic (Thakur & Jain, 2020), with cases including -

• a man from India who had incorrectly diagnosed himself with Covid-19 (Goyal et al., 2020);

• a man from Bangladesh who was avoided by community members due to his confirmed Covid-19 status (Thakur & Jain, 2020); and

• a couple from Chicago, where the man killed himself and his girlfriend because he suspected that they both had Covid-19 (Griffith, 2020).

When considering this, the issue of vicarious trauma becomes particularly relevant. Vicarious trauma can be understood as the experience of trauma-like symptoms brought about by working closely and for extended periods with traumatised victims (Li et al., 2020). The role that SANDF members played during repatriation and the national lockdown might have made them susceptible to vicarious trauma. Li et al. (2020) however found that individuals who were not frontline workers and normal civilian individuals in China experienced higher levels of vicarious trauma compared to the frontline nurses. The acute vicarious trauma experienced by civilian individuals and non-frontline workers was ascribed as due to their lack of psychological preparedness for the Covid-19 pandemic, their empathy towards Covid-19 patients and their lack of knowledge regarding the Covid-19 pandemic (Li et al., 2020).

An important mental health issue related to Covid-19 is stigma. Stigma is simply understood as the discrimination against individuals based on them having undesirable characteristics (Lohiniva et al., 2021; Budhwani & Sun, 2020; World Health Organization [WHO], 2020). In a study by Hasan et al. (2020), four societal groupings were identified in both Bangladesh and India as suffering from stigma and discrimination, namely

• individuals who were Covid-19 positive and who required quarantine'

• frontline health care workers;

• law enforcement officers; and

• workers who were generally subject to discrimination, such as domestic workers (Hasan et al., 2020).

Similar social exclusion due to Covid-19 was observed during an Iranian study (Dehkordi et al., 2020). In China, people from Wuhan, the place associated with the Covid-19 outbreak, experienced stigma and discrimination from other parts of China - a form of xenophobia - and were refused entry into hotels. Those from Wuhan were also forced to undergo a medical check before entering other parts of the country (He et al., 2020). In the digital sphere, Chinese people were also victim to stigma and discrimination.

This took the form of people tweeting that Covid-19 was a "Chinese virus" or "China virus" (Budhwani & Sun, 2020, p.1). In addition to this, the reference to "Chinese virus" (Budhwani & Sun, 2020, p.1) by the then US President Donald Trump sparked a sum of 177 327 tweets all using this reference to refer to Covid-19 (Budhwani & Sun, 2020).

In this way, stigma and discrimination are not limited to certain spaces but may escalate in both physical and digital domains due to fear, ignorance or misinformation. When considering the mental health implications associated with Covid-19, it becomes imperative to monitor and establish whether any stigma or discrimination had taken place. This will allow one to educate military members and the general public and correct stigmatising information and behaviour so that these do not hinder health care interventions in future.

Research aim and objectives

The repatriation of South African citizens from Wuhan was a first for the South African government. These special circumstances of risk presented a unique opportunity to explore experiences of military members who were at the frontline. Based on the studies discussed above, there was no research on the SANDF population in relation to Covid-19 at the time of this research. When one considers the considerable sacrifice offered by SANDF members during the Covid-19 pandemic and the national lockdown in South Africa, it becomes imperative that research be done on this population. The important information obtained at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic through the repatriation exercise could provide a baseline for further research regarding the SANDF and Covid-19. It is also worth considering the valuable and unique insights that SANDF members could provide regarding the first South African repatriation and initial emotions and perceptions of Covid-19.

The exploratory study reported on here aimed to explore the experiences of SANDF members on the first South African repatriation of its citizens due to Covid-19. This had to inform possible stigma, perceptions and emotions that might have been held at the time by SANDF members towards Covid-19, repatriation and quarantine.

This aim was achieved by exploring -

• the perceptions of individuals towards quarantine;

• perceptions towards the first South African repatriation of its citizens;

• possible emotions that individuals might have had towards Covid-19 and the national lockdown;

• any stigma regarding Covid-19; and

• the perceptions of information regarding Covid-19.

Method

This was an exploratory quantitative study, because the researcher only aimed to explore the phenomena and not to confirm any findings. As a result, no hypotheses were stated for this study (Arendse & Maree, 2019). The overarching aim of the study was to consider the experiences of SANDF members on the first South African repatriation in terms of Covid-19. This aim was achieved through the five objectives of the study. The objectives involved descriptive statistics in order to assess the frequency of responses for particular items. Correlation and reliability analyses were conducted on one section of the questionnaire to identity significant relationships between the items. The reliability was assessed as an initial evaluation of the psychometric properties of the questionnaire. Since the sample size was relatively small due to the unique nature of the repatriation mission, the statistical analyses were interpreted with caution and will form a baseline for future psychometric evaluation of the questionnaire.

Participants

The study was aimed at including only SANDF members who had participated in the first repatriation flight to Wuhan, China, and quarantine in South Africa for Covid-19. The sampling procedure was thus purposive sampling. There were no other requirements for the SANDF members participating in the study.

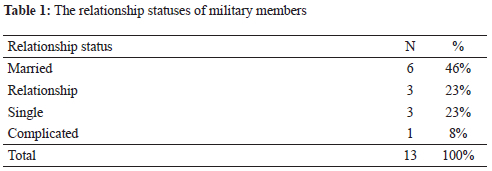

Of the individuals involved in the repatriation, 13 agreed to participate in the study. Although this was a small number of participants, it should be noted that there were very few SANDF members required for the repatriation and quarantine mission. The military members were predominately males (85%). The ages of the military members ranged from 29 to 55 years with a mean age of 39 years. The indicated race groups were African (77%) and White (23%). The majority of the languages indicated were Sepedi (23%), English (15%) and Setswana (15%). Only three of the nine provinces in South Africa were represented, namely Gauteng (77%), Mpumalanga (8%) and North-West (8%). The highest education of the repatriated military members ranged from Grade 12 to a master's degree, with the majority of the military members having a bachelor's degree (31%). The occupations listed by the military members included military practitioners, nurses, a psychologist, a social worker and a few military officers. The relationship statuses of the military members are indicated in Table 1. The majority of the staff were married (46%). In terms of the number of dependants listed by the military members, this ranged from none to 7 dependants. The type of dependants was identified as both financial and emotional (31%) and only financial (39%).

Instrument

A self-completed questionnaire labelled Stigma and Related Matters Questionnaire was empirically created by the researcher and was informed by literature (see Brooks et al., 2020; Cheung, 2015; Person et al., 2004; Stangl et al., 2019). The questionnaire was only piloted on a few members to assess the language used and to confirm their understanding of the questions posed. No psychometric analysis of the questionnaire was conducted prior to the repatriation sample. The instructions were provided to ensure clarity and the biographical questions were added for research purposes to describe the sample participating in the study. No identifying information was required on the questionnaire and this ensured anonymity. The Stigma and Related Matters Questionnaire contains 37 questions, namely 12 word association questions and 25 Covid-19 statements. The first section, word association questions, consists of five answer options with the fifth option allowing participants to enter a more suitable answer if one is not available. The second section, Covid-19 statements, consists of 25 statements with five answer options (strongly disagree, disagree, unsure, agree, and strongly agree). As stated previously, there no psychometric properties were indicated on the questionnaire because the repatriation sample was the first to use the questionnaire. Moreover, the questionnaire was specifically developed for the Covid-19 pandemic. This article will however be reporting on the initial reliability of the questionnaire. The Stigma and Related Matters Questionnaire took a maximum of 10-15 minutes to complete. It should be noted that in this study, the term 'persons under investigation' (PUI) referred to the repatriated individuals for whom the SANDF members had to care during the repatriation and quarantine.

Data collection procedure

The following procedure was followed for this study: after getting permission from the relevant authorities within the South African Medical Health Service (SAMHS), a nodal person was identified within the repatriated group to assist with the data collection process because strict Covid-19 protocols were in place for the repatriated group at the time. The researcher provided the nodal person with the following: a step-by-step administration guideline for the questionnaire, the information sheet, consent forms, and copies of the questionnaire. When the informed consent forms were handed to the individuals, the nodal person explained the research to them. On agreement of participating in the research, the consent forms were collected and the Stigma and Related Matters Questionnaire was given to them to complete. The Stigma and Related Matters Questionnaire was then returned to the researcher by the nodal person once the repatriation process had been completed. All 13 questionnaires were completed and returned. The consent forms and questionnaires were filed in a secure facility.

Data analysis

Since the questionnaire predominately contains closed-ended answer options, the chosen method of analysis was quantitative. Descriptive statistics were run through SPSS to explore the nature of the sample that completed the questionnaire. The racial biographical information was required to explain the sample obtained. No generalisations or inferences were made during this research study on the basis of the biographical data, and thus it only served to describe the sample. Frequencies were calculated to assess the pattern of responses for the word association questions and Covid-19 statements of the questionnaire. Since the word association questions did not have a standard answer option and allowed participants to enter their own answer, these items were excluded from a reliability and correlation analysis. As a result, the reliability and correlation analysis was only run on the Covid-19 statements to evaluate the internal consistency and relationships among these statements. The correlation strength was interpreted according to the framework drafted by the Quinnipiac University (cited in Akoglu 2018): .1 negligible, .2 weak, .3 moderate, .4-.6 strong, .7-.9 very strong and 1 perfect. It should also be noted that, when conducting the reliability analysis, the negatively phrased items (16 items) were reverse scored. The reliability coefficient, Cronbach's alpha, was interpreted in terms of the closeness of the value to 1, which would be indicative of a high internal consistency within this section of the questionnaire (Arendse, 2020; Cronbach, 1951; Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994; Taber, 2018).

Ethical considerations

In line with the South African Good Clinical Practise Guidelines (Department of Health, 2006), the participants in the study did not meet the requirements for a vulnerable population. Moreover, it should be noted that their participation was regarded as a "negligible risk" (Department of Health, 2006, p. 17). The risk involved with this research study was therefore very low. This low risk was informed by the minimal potential risk this study posed to participants, as there were no physical risks associated with participating in the study. Additionally, the subject matter covered in the questionnaire concerned perceptions and emotions and did not pose any psychological discomfort or stress to the participants. The following ethical principles were taken into account in terms of this study and are also informed by the South African Good Clinical Practise Guidelines (Department of Health, 2006): respect for persons, informed consent, voluntary participation, and beneficence and justice. Efforts were made to protect individual autonomy, minimise harm and maximise benefits. The steps taken to ensure that there was compliance with these ethical principles involved that military members -

• were informed of the research and that participation was voluntary;

• completed an informed consent form, and the questionnaire did not require any identifying information; and

• were informed throughout the process that, if they were uncomfortable with any questions, they could contact the researcher.

This study was ethically approved by the 1 Military Hospital Ethics Committee (ref: 1MH/302/6/01.07.2020), a registered ethics committee.

Results

The results section presents the descriptive, reliability and correlation analyses conducted in terms of the questionnaire. The results are presented according to the two sections of the questionnaire, namely the word association (descriptive statistics) and the Covid-19 statements (reliability, descriptive and correlation analyses).

Word association responses

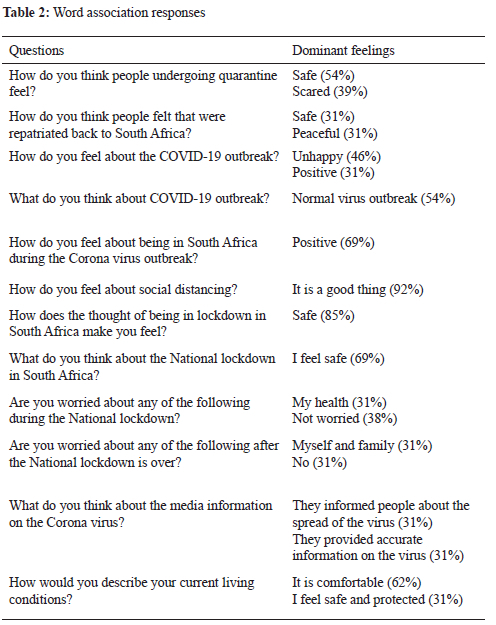

The word association questions had predominately two main responses. The responses to these questions were labelled as dominant feelings because the answer options indicated different emotional states.

In Table 2, the dominant emotional states are indicated for the different questions posed in this section of the questionnaire. When examining the responses to the different questions, it became apparent that there was a predominantly positive outlook on Covid-19, repatriation and quarantine. Although very little was known about Covid-19 at the time of the study in the year 2020, the respondents felt safe and were supportive of government measures such as social distancing and the lockdown.

Covid-19 statement responses

The results for the Covid-19 statements are presented as follows: reliability, frequency of responses, and correlation of these statements.

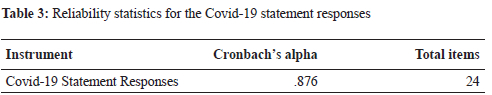

In Table 3, the reliability statistic is indicated for the Covid-19 statements. A Cronbach's alpha of .876 suggests that these 24 Covid-19 statements were sufficiently reliable (see Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994).

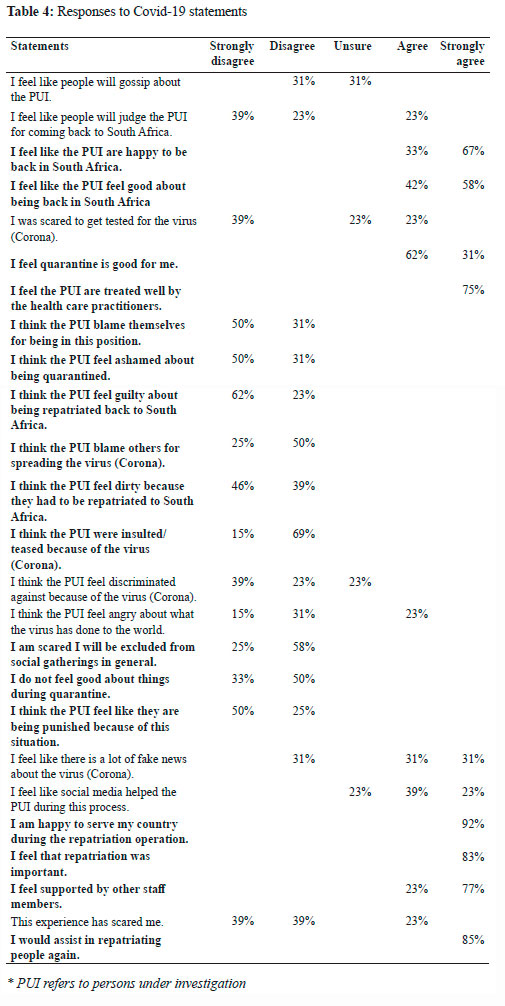

In Table 4, the frequencies of responses chosen by the military members are indicated. It should be noted that only the highest percentages are shown in the table to illustrate the predominant responses. In general, the 'unsure' answer option was only used to a small extent as military members appeared to have a clear idea of whether they agreed or disagreed with the statements. There were some statements that showed a very clear pattern of agreement and disagreement by military members. These sentences were bolded to show how clearly military members responded to these statements. When assessing the content of the statements and the responses by military members, it became very apparent that an overwhelming sense of positivity and dedication was indicated in their responses. The responses to quarantine, repatriation and the perception of PUI's feelings suggest that the military members experienced the Covid-19 repatriation and quarantine as an important task that they were confident to execute. It is however worth noting that there was a smaller percentage of military members that were not as positive and had some doubts regarding the perception of PUI's feelings and quarantine.

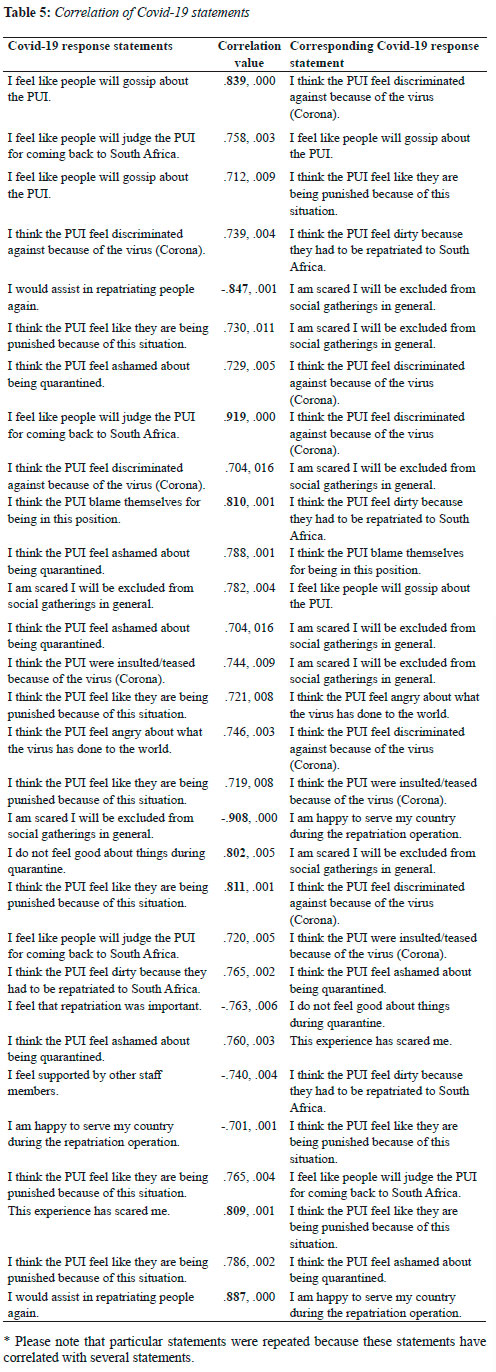

In Table 5, the highest statistically significant correlations observed across the different Covid-19 statements are shown. There were some high correlations but these were not statically significant and were thus not included in the table above. All the correlations in the table are considered large, indicating that there are strong to very strong relationships among these statements (Akoglu, 2018). The strength of these relationships suggests that the statements indicated above are measuring similar constructs. In addition to this, some strong negative correlations indicate that these statements have an inverse relationship with one another. The correlations that have been highlighted in Table 5 show the statements with the strongest relationships. These statements are:

• I think the PUI feel discriminated against because of the virus (Corona)

• I am scared I will be excluded from social gatherings in general

• I think the PUI feel like they are being punished because of this situation

• I think the PUI feel dirty because they had to be repatriated to South Africa

• I am scared I will be excluded from social gatherings in general

• I am happy to serve my country during the repatriation operation.

Discussion

The results are discussed according to the objectives of the study as indicated previously.

Exploring perceptions towards quarantine

The military members' responses to the questions indicated that they perceived the PUI as feeling both safe and scared with regard to quarantine. Their feeling 'scared' could have been due to the uncertainty regarding Covid-19 at the time of repatriation, while those indicating 'safe' were perhaps confident in terms of the process of quarantine. Lohiniva et al. (2021) however found that participants were worried and fearful during quarantine. The military members did not feel that the PUI felt ashamed about quarantine (81%) and they strongly agreed that the PUI were treated well by health care practitioners (75%). They agreed that quarantine was necessary (93%) and they felt good about things during quarantine (83%). Likewise, Lohiniva et al. (2021) found that individuals did not experience stigma during quarantine, as their social interactions were limited. Hasan et al. (2020) however found that those individuals who were Covid-19-positive and needed to quarantine were subject to stigma and discrimination. This also led to them being socially excluded by others (Hasan et al., 2020). PUI undergoing quarantine in Bangladesh had their details disclosed to the public, and they were evicted onto the street because of their Covid-19 status and symptoms (Hasan et al., 2020).

Exploring perceptions towards South Africa's first repatriation

Since this was the first South African repatriation related to Covid-19, it presented an extraordinary experience for both the military members and PUI. According to the military members, PUI -

• felt safe and peaceful regarding their repatriation back to South Africa;

• did not feel guilty about being repatriated back to South Africa (85%);

• did not feel dirty because they had to be repatriated to South Africa (85%);

• were happy to be back in South Africa (100%);

• felt good about returning to South Africa (100%); and

• felt that people would not judge the PUI for returning to South Africa (62%).

Kawuki et al. (2021) acknowledge that repatriation was important and held many benefits for the country. However, they warn against the after-effects of being repatriated that may lead to discrimination and stigma.

The military members' own perceptions towards their experience of repatriation revealed the following:

• they were happy to serve their country (South Africa) during the repatriation operation (92%);

• they felt that repatriation was important (83%);

• they would assist in repatriating people again (85%);

• they felt supported by other staff members; (100%); and

• the repatriation experience did not scare them (78%).

The positive attitude towards repatriation and its necessity was in line with findings by Kawuki et al. (2021).

Exploring possible emotions towards Covid-19 and national lockdown

Some of the military members felt that the Covid-19 outbreak was a normal virus outbreak (54%). Farhana and Mannan (2020) similarly found that medical professionals understood Covid-19 as a result of natural causes, which correlates to how the majority of the SANDF military members viewed the Covid-19 outbreak. The positive experience of military members may be explained by timely and reliable information received about the Covid-19 outbreak. Olapegba et al. (2020) however reported that 50% of their study participants (Nigerians) viewed Covid-19 as a "biological weapon designed by the government of China" (Olapegba et al., 2020, p. 6).

The Covid-19 outbreak made some of the military members feel unhappy (46%) while others felt positive (31%). The positive outlook on lockdown was also found in the HSRC study (Dukhi et al., 2020; HSRC, 2020). The 46% unhappiness among this sample indicated above agreed with the finding by Roy et al. (2020) where people were concerned and fearful of Covid-19.

The military members predominately felt that lockdown (69%) and being in lockdown in South Africa made them feel safe (85%). This correlates with the HSRC findings that 99% of South Africans complied with the movement restrictions while 50% of them felt safe (Dukhi et al., 2020, HSRC, 2020). Abdelhafiz et al. (2020) similarly found a positive attitude among Egyptian participants in their study. The current study and the study by Abdelhafiz et al. (2020) are however contradictory, as in India and Nepal, people expressed their restlessness and distress that a lockdown was being enforced because of Covid-19 (Koirala et al., 2020).

When asked what they were worried about during and after the national lockdown was over, the responses by the military members indicated that some were worried about their health (31%), and about themselves and their family (31%), while others were not worried (38% and 31% respectively across different questions). When asked about their perception of PUI in relation to Covid-19, military members indicated that -

• they thought that the PUI did not blame themselves for being in this position (81%);

• they thought PUI blamed others for spreading the Covid-19 virus (75%); and

• they did not think that the PUI felt angry about what the virus had done to the world (46%).

The perception that military members had regarding the emotions of PUI towards the Covid-19 pandemic could have been influenced by the PUI acquiring sufficient information on the Covid-19 outbreak and their repatriation. In contradiction to this, Lohiniva et al. (2021) found that participants felt that they were stigmatised because some blamed them for getting Covid-19 and others were angry with them for making them vulnerable to infection of Covid-19.

Exploring any stigma regarding Covid-19

The military members indicated that they felt social distancing was a good thing (92%). Furthermore, they felt positive about being in South Africa during the Corona virus outbreak (69%) and they were not scared that they would be excluded from social gatherings (83%). This was contradictory to Roy et al. (2020) who found that people were avoidant of socialising and there was fear regarding the spread of the virus. In Bangladesh, PUI, health care workers and law enforcement officers involved with Covid-19 were all subject to stigma and discrimination (Hasan et al., 2020; Lohiniva et al., 2021). This also involved social exclusion and some being asked to leave their homes (Hasan et al., 2020). In Iran, PUI reported experiencing social rejection due to their Covid-19-positive status. Some indicated that their family also limited telephonic contact as they felt they could become infected through telephonic contact, while some reported that their neighbours stopped their children from playing together after their Covid-19 status had become known (Dehkordi et al., 2020). The results obtained for the current study might differ from other studies as the study was conducted early in 2020 and emotions towards social distancing and the Covid-19 pandemic might have differed later in 2020.

The military members were unsure whether people would gossip about the PUI (31%) but did not feel that the PUI were insulted and/or teased because of the virus (84%). They did not feel that the PUI felt discriminated against (62%) or that they felt that they were being punished because of the situation (75%). In contrast, Roy et al. (2020) found that recovered individuals from India were exposed to some stigma. Lohiniva et al. (2021) found that participants experienced others gossiping about them due to Covid-19 and as a result, they felt discriminated and stigmatised. It should however be cautioned that the Stigma and Related Matters Questionnaire was completed before reintegration into society, and thus the PUI did not have contact with people outside their quarantine. As a result, these findings might have been premature.

Exploring the perceptions of information regarding Covid-19

The military members reported that they felt the media informed people about the spread of the virus (31%) and that they provided accurate information on the virus (31%). This relates to a study by Roy et al. (2020) and another by Olapegba et al (2020) which found that people knew the basic transmission of the virus and how to prevent it, as it was very contagious. Geldsetzer (2020), Abdelhafiz et al. (2020) and Olapegba et al. (2020) similarly found that people were informed on the virus symptoms and protocols to follow when they were infected with Covid-19.

Although the military members felt that there was a lot of fake news about the virus (62%), they also felt that social media helped the PUI during the process (62%). There were also some reports of misinformation in some studies that contributed to stigma (see Abdelhafiz et al., 2020; Lohiniva et al., 2021). Lohiniva et al. (2021) and De Quervain et al. (2020) both found that individuals who kept up to date with Covid-19 news showed increased stress levels.

Overall, the perceptions of quarantine and towards being quarantined were positive. Based on the responses by military members, it was suggested that the perceptions and experiences of repatriation were strongly supported by them and by PUI. The emotions indicated by the military members were predominately optimistic and suggested that they were in agreement with the imposed lockdown as it allowed them to feel safe. Despite this feeling of safety, there were some worries that were indicated by the military members. Moreover, their perception of how PUI felt regarding Covid-19 suggested that some had accepted the virus outbreak and did not cast blame on themselves or others. The responses by military members and their perception of how the PUI felt, suggested that, for the majority of them, there appeared to be no stigma at the time. It should however be noted that this did not mean that there was no stigma present, but rather that it was only present to a small extent for this sample. In terms of how information on Covid-19 was perceived by military members, there appeared to be mixed responses regarding the accuracy of information available on social media. It should be noted that the current study was conducted at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic and the views and perceptions indicated in this article might have shifted since. In terms of the questionnaire, the Covid-19 statements showed great promise with the high reliability observed. The word association questions should however be researched further before developing them into closed-ended statements that can be validated.

Limitations and recommendations

There were a few limitations in terms of this study that should be noted. The self-administered questionnaire on stigma and related matters was not comprehensive in terms of all the emotions and perceptions experienced or present during the Covid-19 pandemic in South Africa. For this reason, this article can only reflect deductions on the responses to the questions. Since participation in this study was voluntary, the sample size or this study was very small. However, the significance of this sample (i.e. the first repatriation by South Africa), was examined for exploratory purposes. The study was conducted during the onset of Covid-19 in 2020, and thus the emotions and feelings were only relevant for that particular period and for the military members participating in the study. There was a restriction of range so it is not possible to generalise the results of this study. It is recommended that follow-up studies be conducted in terms of the questionnaire to explore both changes in attitude and the validity of the questionnaire.

Conclusion

During the initial outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, many nations were compelled to repatriate their citizens from across the globe, and South Africa was among these nations. This repatriation mission was a first for South Africa, and the SANDF was an essential part of this mission. The main aim of the study was to explore the experiences of SANDF members involved in both the repatriation of citizens and quarantine in terms of the Covid-19. Although a small sample was obtained, the repatriation and quarantine mission did not require many SANDF members to be involved. The Stigma and Related Matters Questionnaire provided valuable information and a baseline for other SANDF studies related to Covid-19. In addition to this, the high reliability obtained for the statements section of the questionnaire advocates the continued use of the questionnaire. The findings suggested that the military members were predominately positive and supportive of virus containment measures and lockdown practices. The majority did not report any stigmatising or discriminatory beliefs around Covid-19 nor did they believe the PUI were stigmatised. Their responses were however in contrast to literature from other countries and contexts where people reported having experienced severe discrimination and stigma. There was however literature that supported the positive perceptions on virus containment measures observed in this study. It should be noted that this study took place during the onset of Covid-19 in South Africa while the military members were not yet in contact with the outside world and this may have affected their responses at the time. This study contributes to Covid-19 research and provides a particularly unique observation with its focus on the SANDF and South Africa's first repatriation. More research is recommended on the Covid-19 pandemic in South Africa, and particularly its effects in the SANDF.

Acknowledgements

The author declares that she has no financial or personal relationship that may have inappropriately influenced her in writing this article. The author would like to thank Ms Sasha Jugdav for her assistance with this project.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not reflect the official position of any institution.

References

Abdelhafiz, A. S., Mohammed, Z., Ibrahim, M. E., Ziady, H. H., Alorabi, M., Ayyad, M., & Sultan, E. A. (2020). Knowledge, perceptions, and attitude of Egyptians towards the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Journal of Community Health, 45(5), 881- 890. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-020-00827-7 [ Links ]

Akoglu, H. (2018). User's guide to correlation coefficients. Turkish Journal of Emergency Medicine, 18, 91-93. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.tjem.2018.08.001 [ Links ]

Arendse, D. E. (2020). The impact of different time limits and test versions on reliability in South Africa. African Journal of Psychological Assessment, 2(14), 1-10. http://doi.org/10.4102/ajopa.v2i0.14 [ Links ]

Arendse, D. E., & Maree, D. (2019). Exploring the factor structure of the English Comprehension Test. South African Journal of Psychology, 49(3), 376-390. [ Links ]

Brooks, S., Webster, R., Smith, L., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395(10227), 912-920. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8 [ Links ]

Budhwani, H., & Sun, R. (2020). Creating COVID-19 stigma by referencing the novel coronavirus as the "Chinese virus" on Twitter: Quantitative analysis of social media data. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(5), 1-7. https://doi.org/10.2196/1930 [ Links ]

Cheung, E. Y. L. (2015). An outbreak of fear, rumours and stigma: Psychosocial support for the Ebola virus disease outbreak in West Africa. Intervention, Journal of Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Conflict Affected Areas, 13(1), 70-76. https://doi.org/10.1097/WTF.00000000000000079 [ Links ]

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16, 297-334. [ Links ]

Dehkordi, M. A., Eisazadeh, F., & Aghjanbaglu, S. (2020). Psychological consequences of PUI with coronavirus (COVID-19): A qualitative study. Iranian Journal of Health Psychology, 2(2), 9-20. https://doi.org/10.30473/IJOHP.2020.52395.1074 [ Links ]

Department of Health. (2006). Guidelines for good practice in the conduct of clinical trials with human participants in South Africa. [ Links ]

De Quervain, D., Aerni, A., Amini, E., Bentz, D., Coynel, D., Gerhards, C., Fehlmann, B., Freytag, V., Papassotiropoulos, A., Schicktanz, N., Schlitt, T., Zimmer, A., & Zuber, P. (2020). The Swiss Corona Stress Study. http://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/jqw6a [ Links ]

Dukhi, N., Mokhele, T., Parker, W., Ramlagan, S., Gaida, R., Mabaso, M., Sewpaul, R., Jooste, S., Naidoo, I., Parker, S., Moshabela, M., Zuma, K., & Reddy, P. (2021). Compliance with lockdown regulations during the COVID-19 pandemic in South Africa: Findings from an online survey. The Open Public Health Journal, 14, 45-55. [ Links ]

Farhana, K. M., & Mannan, K. A. (2020). Knowledge and perception towards novel coronavirus (COVID-19) in Bangladesh. International Research Journal of Business and Social Sciences, 6(2), 75-79. http://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3576523 [ Links ]

Geldsetzer, P. (2020). Knowledge and perceptions of COVID-19 among the general public in the United States and the United Kingdom: A cross-sectional online survey. Annals of Internal Medicine, 173(2), 157-160. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-0912 [ Links ]

Goyal, K., Chauhan, P., Chhikara, K., Gupta, P., & Singh, M. P. (2020). Fear of COVID 2019: First suicidal case in India! Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 49, Art. 101989. https://doi.org/10.1016./j.ajp.2020.101989 [ Links ]

Griffith, J. (2020, April 6). Illinois man who suspected girlfriend had COVID-19 fatally shoots her and himself. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/illinois-man-who-suspected-girlfriend-had-covid-19-fatally-shoots-n1177571 [ Links ]

Hasan, M., Hossain, S., Saran, T. R., & Ahmed, H. U. (2020). Addressing the COVID-19 related stigma and discrimination: A fight against "infodemic" in Bangladesh. Minerva Psichiatrica, 61(4), 184-191. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/gpbj7 [ Links ]

He, J., He, L., Zhou, W., Nie, X., & He, M. (2020). Discrimination and social exclusion in the outbreak of COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(8), 17-20. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17082933 [ Links ]

Human Sciences Research Council. (2020). HSRC study on COVID-19 indicates overwhelming compliance with the lockdown. http://www.hsrc.ac.za/en/media-briefs/general/lockdown-survey-results [ Links ]

Kawuki, J., Papabathini, S. S., Obore, N., & Ghimire, U. (2021). Evacuation and repatriation amidst COVID-19 pandemic. SciMedicine Journal, 3, 50-54. http://doi.org/10.28991/SciMedJ-2021-03-SI-7 [ Links ]

Koirala, J., Acharya, S., & Neupane, M. (2020, April 4). Perceived stress in pandemic disaster: A case study from India and Nepal. SSRN. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3568388 [ Links ]

Li, Z., Ge, J., Yang, M., Feng, J., Qiao, M., Jiang, R., Bi, J., Zhan, G., Xu, X., Wang, L., Zhou, Q., Zhou, C., Pan, Y., Liu, S., Zhang, H., Yang, J., Zhu, B., Hu, Y., Hashimoto, K., ... Yang, C. (2020). Vicarious traumatization in the general public, members, and non-members of medical teams aiding in COVID-19 control. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 88, 916-919. https://doi.org/10.1016Zj.bbi.2020.03.007 [ Links ]

Lohiniva, A.-L., Dub, T., Hagberg, L., & Nohynek, H. (2021). Learning about COVID-19-related stigma, quarantine and isolation experiences in Finland. PLOS ONE, 16(4), e0247962. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247962 [ Links ]

Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Olapegba, P. O., Ayandele, O., Kolawole, S. O., Orguntayo, R., Gandi, J. C., Dangiwa, A. L., Ottu, I. F., & Iorfa, S. K. (2020). A preliminary assessment of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) knowledge and perceptions in Nigeria. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.11.20061408 [ Links ]

Perappadan, B. S. (2020, March 31). Preventing stigma related to COVID-19 requires full-throated campaign, says expert Gita Sen. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/preventing-stigma-related-to-covid-19-requires-full-throated-campaign-says-expert-gita-sen/article31215075.ece [ Links ]

Person, B., Sy, F., Holton, K., Govert, B., Liang, A., & NCID/SARS Community Outreach Team. (2004). Fear and stigma: The epidemic within the SARS outbreak. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 10(2), 358-363. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1002.030750 [ Links ]

Ramaphosa, C. (2021, February 22). President commends SANDF role in COVID-19 fight. South Africa Government News Agency. https://www.sanews.gov.za/south-africa/president-commends-sandf-role-covid-19-fight [ Links ]

Roy, D., Tripathy, S., Kar, S. K., Sharma, N., Verma, S. K., & Kaushal, V. (2020). Study of knowledge, attitude, anxiety and perceived mental healthcare need in Indian population during COVID-19 pandemic. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102083 [ Links ]

Stangl, A. L., Earnshaw, V. A., Logie, C. H., Van Brakel, W., Simbayi, L. C., Barre, I., & Dovidio, J. F. (2019). The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework: A global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Medicine, 17(31), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-019-1271-3 [ Links ]

Taber, K. S. (2018). The use of Cronbach's alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Research Science Education, (48), 1273-1296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2 [ Links ]

Thakur, V., & Jain, A. (2020). COVID 2019-suicides: A global psychological pandemic. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 88, 952-953. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.062 [ Links ]

Turok, I., & Visagie, J. (2020). COVID-19 hits poor urban communities hardest: Density matters. HSRC Review, 18(4), 26-28. [ Links ]

Wang, C., Pan, R., Wan, X., Tan, Y., Xu, L., Ho, C. S., & Ho, R. C. (2020). Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), Art. 1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051729 [ Links ]

World Health Organization. (2020). Social stigma associated with COVID-19: A guide to preventing and addressing social stigma. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/covid19-stigma-guide.pdf [ Links ]

World Medical Association. (2013). Declaration of Helsinki Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. World Medical Association General Assembly. [ Links ]

1 Danille Elize Arendse obtained a BA (psychology), BA Honours degree (Psychology) and MA (Research Psychology) degree from the University of the Western Cape. She joined the SANDF in 2011 as a uniformed member and became employed as a Research Psychologist at the Military Psychological Institute (MPI). She completed her PhD in Psychology at the University of Pretoria in 2018. She currently holds a Major rank and is the Research Psychology Intern Supervisor and Coordinator at MPI. She is also a Research Associate for the Department of Psychology at the University of Pretoria. She has recently become an Accredited Conflict Dynamics Mediator. She is currently participating in the Diverse Black Africa program affiliated with Michigan State University. She has presented and published papers both locally and internationally.