Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Scientia Militaria: South African Journal of Military Studies

versão On-line ISSN 2224-0020

versão impressa ISSN 1022-8136

SM vol.50 no.2 Cape Town 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.5787/50-2-1375

ARTICLES

Comparing deployment experiences of South African National Defence Force personnel during peace support missions: Sudan vs Democratic Republic of Congo

Nicolette Visagie1; Renier Armand du Toit2; Stephanie Joubert3; David Schoeman4; Didi Zungu5

Military Psychological Institute: Human Factor Combat Readiness Section

ABSTRACT

The South African National Defence Force (SANDF) has operational responsibilities in Africa regarding peace support operations. These deployments are the bread and butter of the SANDF and members are therefore frequently deployed for extended periods. These deployments are unique environments with taxing circumstances, which place various psychological demands on the soldier. The psychological impact of these demands originates not only from combat and the consequent clinical effect thereof, but also from organisational factors and the contribution of family stressors. The study reported here endeavoured to examine the positive and negative subjective deployment experiences of soldiers in two different mission areas. The data are compared and further utilised to provide a framework of two proposed matrices, namely booster and stressor matrices, which may affect the optimal psychological functioning of soldiers. The study adopted a survey design utilising qualitative data focusing on retrospective data. The data stems from the Psychological Demobilisation Questionnaire developed by psychologists in the SANDF and amended by the authors. Data were collected from both combat service support and combat forces, from two different missions in different countries, both missions were one year in duration. Data revealed both positive and negative experiences correlating with the context of operations. These themes were categorised in terms of the sphere of functioning (organisational, family and clinical) from the deployment experience. The booster and stressor matrices provide a practical and accessible framework to military commanders on how to 'boost' or mitigate some of the experiences of their deployed force, as the commanders play a key role in the deployed soldier's experience and the impact of such experiences in the theatre of operation.

Keywords: peace support operations, SANDF, deployment experiences psychological impact of operations.

Introduction

The SANDF commenced its contributions of personnel to peace support operations (PSOs) in 1998, and has been involved in various deployments, reaching 14 missions altogether in 2013 (Lotze et al., 2015; Wilen & Heinecken, 2017). These missions - which can be seen as the 'bread and butter' of the SANDF - present the soldiers with a myriad of psychological demands (Britt & Adler, 2003). These demands on the soldiers occur specifically during and after deployment. Two distinct theatres of operation in which the SANDF have served are Operation Cordite (in the Darfur region of Sudan) and the Force Intervention Brigade (FIB) (in north-eastern Kivu, a province in the Democratic Republic of Congo [DRC]).

Tools that are useful for screening large groups, specifically related to post-traumatic stress in military samples, have been explored to address the time and personnel constraints that regular health assessments place on the South African Military Health Service (SAMHS) (Van Wijk et al., 2013). Most of these needs are centred on the negative experiences or impact of the PSO on the wellbeing of our soldiers, with most of the adverse effects focused on the clinical functioning of soldiers (Raju, 2014; Van Wijk, 2011). These are imperative to mitigate any long-term effects of deployment.

An exploration into factors that contribute to the overall deployment experience of the soldier whilst deployed for 12 months was however lacking at the time of this research. The current study therefore provides a snapshot to understand the possible influence of these experiences on the soldier's overall deployment wellbeing, together with the notion that such understanding could provide the organisation with valuable information for future deployments.

This study examined the positive and negative self-reported experiences of SANDF personnel during two different missions, and the data are compared. The descriptions of the deployment experiences provided an understanding of the deployment experiences in terms of themes. These themes were furthermore categorised into three distinct spheres of functioning, and a tripartite model is presented to understand the impact these deployment experiences had on our soldiers. The themes were gleaned from the positive and negative deployment experiences.

Peace support operations

The SANDF is trained for conventional warfare; however, mostly conducts PSOs. These missions have been described by South African researchers such as Wilen and Heinecken (2017) as challenging for various reasons. One of these challenges is characterised as no clearly defined foe. Soldiers therefore have to rely on skill sets other than their conventional warfare training, such as negotiation, diplomatic skills, observation and strategies in order to avoid conflict. Peacekeepers also face difficulty or are accused of contravening the principle of impartiality, a core value of peacekeeping alongside the consent of the parties and the non-use of force except in situations of self-defence (Salaun, 2019). These unique challenges of PSOs, which are not inherent in traditional warfare, have a direct influence on the deployment experiences of personnel that have to negotiate or establish the status quo.

According to the SANDF (2006, p. 23):

PSO is a military term used to denote multi-functional and multinational operations conducted in support of a UN mandate, focused on activities to restore peace within war-torn countries/regions. These operations include all civil and military organisations and may involve diplomatic efforts, humanitarian actions and military deployments. Outside military circles, the term 'Peacekeeping' is often used erroneously to embrace all PSO, including PE [peace enforcement].

Furthermore, when consent for and compliance with a PSO is high, peace enforcement (PE) and peace keeping (PK) forces will adopt similar approaches. Both PK and PE are designed to achieve the same end-state, which is a secure environment and a self-sustaining peace. In the first instance, a PK force bases its operations on the consent of the parties, and is not capable of exercising force beyond that required for self-defence. Such a force would find its freedom of action considerably more constrained than a combat-capable PE force, should consent be uncertain or withdrawn (SANDF, 2006, p. 24).

A lightly armed PK force, therefore, should not be given, nor attempt to conduct, enforcement tasks that may provoke hostile reactions that are beyond its ability to manage and that may escalate to war. Only a PE force prepared for combat and capable of effective coercion should be deployed into a potentially hostile environment" (South African Army, n.d., p. 24 par 4).

Operations Cordite and the Force Intervention Brigade

The only constant in all missions to which our soldiers deploy is the soldier. Operations differ in their history, belligerents, mandates and environment. These differences have a role to play in the experience of the peacekeeper, and the subsequent outcome of the experience.

Operation Cordite

The mission in Darfur in the Sudan was originally a PK mission authorised under Chapter VI of the UN Charter, and commissioned under the African Union (AU) as the African Union Mission in Sudan (AMIS). AMIS initially had an observer mandate, implying that the PK forces were mandated to 'observe and report' and the use of force was authorised only in self-defence. The PK force was soon increased, and the mandate adapted to include aspects such as the separation of belligerent factions, assurance of freedom of movement, and enforcement of the ceasefire agreement, but the use of force was still restricted to self-defence and to prevent the blatant perpetration of atrocities (E.Visagie, personal communication, 12 October 2021). The mandate of AMIS was continually amended and forces expanded as the situation in Darfur developed and worsened. This continued until 2007, when the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 1564, which paved the way for the replacement of AMIS with UNAMID. UNAMID was the African Union-United Nations Hybrid Operation in Darfur. This was a joint PK mission commissioned by the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) after the passing of Resolution 1769, but still under Chapter VI of the UN Charter. The peacekeepers were, under this new mandate, allowed to use force in self-defence and to protect civilians and humanitarian operations. Both AMIS and UNAMID were therefore always under Chapter VI of the Charter and no offensive military operations were ever mandated. The PK forces were there to observe and report and to monitor and enforce the peace agreement and ceasefire agreement. Operation Cordite was the SANDF operation under which South Africa contributed forces to both AMIS and UNAMID (E Visagie, personal communication, 12 October 2021).

From Operation Mistral to FIB

Operation Mistral is the SANDF operation that contributed forces to MONUC and later to MONUSCO in the DRC. MONUC was the original UN mission, mandated by UNSC Resolution 1291, to observe and report on the compliance with peace accords by the belligerent factions in the DRC until 2010, after which MONUSCO was established with the passing of UNSC Resolution 1925 (E. Visagie, personal communication, 12 October 2021) Both MONUC and MONUSCO are mandated under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, authorising them to take action in order to -

• protect UN personnel, facilities, installations and equipment;

• ensure the security and freedom of movement of its personnel; and

• protect civilians under imminent threat of physical violence.

Unlike the AMIS and UNAMID forces, the MONUSCO forces are therefore authorised to use force to execute its mandate, although offensive military operations are not allowed.

The Force Intervention Brigade (FIB) was conceived at an international conference where the failure of MONUSCO to end the violence in the DRC featured prominently on the agenda (E. Visagie, personal communication, 12 October 2021). The FIB is not the first instance where the UNSC has authorised the use of force, but it was the first time in UN history where a PK force was established and authorised to use offensive military operations to 'neutralise and disarm' groups or factions threatening peace and security. Although still under Chapter VII of the Charter, the mandate of the FIB is purely offensive, allowing it to plan and execute targeted offensive operations in order to attack and destroy rebel and militia groups. Its first operations were conducted against the M23 Militia group in Eastern DRC, which was attacked and defeated. Several bases of the ADF have been attacked and destroyed by the FIB in the period after that (E Visagie, personal communication, 12 October 2021).

The Cordite and Mistral deployments therefore differed mainly in mandate. Whereas Operation Cordite forces were severely hampered by mandate restrictions, Operation Mistral, and specifically the FIB, had a much more robust and offensive mandate, giving it much more freedom to act militarily.

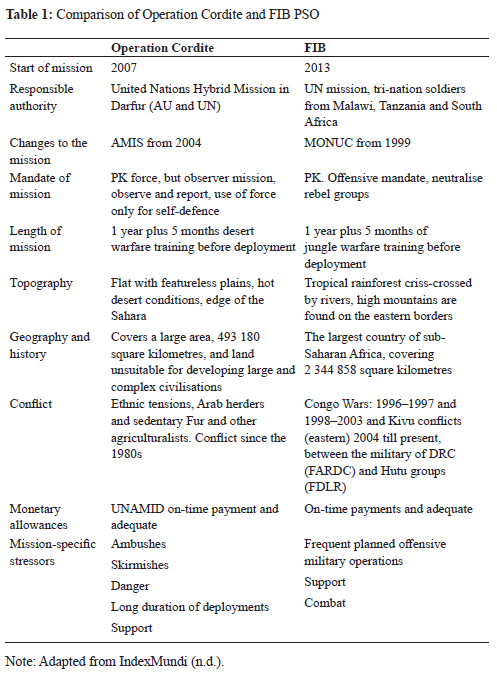

A comparison of the operations is presented in Table 1 for some additional contextual information. The type of area as well as the nature of the mission contributes greatly to the experience of the soldier (Martin, 2019). The two areas are compared for an understanding of the mission-specific and geographical differences or similarities that may affect SANDF personnel during their tour of duty.

During 2015, some 2 200 SANDF personnel were deployed on PK duties. During that time, a total of 18 000 troops were either deployed, being prepared for deployments, or coming back from deployments. The heavy burden of deployments on the SANDF and its personnel and the varying nature of the deployments are highlighted by Table 1. This could have contributed negatively or positively to the psychological wellbeing of soldiers (Martin, 2019).

Deployment experiences of soldiers associated with PSO

A vast body of literature documents stressor experiences associated with soldiers and military deployments (Bartone et al., 1998; Kgosana & Van Dyk, 2011; Raju, 2014). Little literature regarding the positive experiences of soldiers during deployments is available (see Runge et al., 2020). Over the years, the SANDF has contributed to this body of literature, focusing on exploring the experiences of specific groups during deployment, such as military psychologists, airborne section leaders, as well as a PK mission in DRC (Bruwer & Van Dyk, 2005; Williamson, 2015; Zungu & Visagie, 2020).

PSO operations place demands on deploying soldiers that heavily overlap with stressors found in traditional work settings, such as role-related stressors, time and workload stressors, relationship stressors, change stressors, physical and environmental stressors as well as organisational culture stressors. However, deployment environments also have military-specific stressors, such as mission ambiguity, engagement rules of engagement, leadership climate stressors as well as cultural and situational ambiguity (Campbell & Nobel, 2009, Van Dyk, 2009).

According to Chambel and Oliviera-Cruz (2010), soldiers on a PKO develop a perception of mutual obligations between themselves and the organisation about the mission. By deciding to deploy to a mission, soldiers accept the obligations of such deployments and have expectations related to the obligations of the organisation toward them. This may include aspects such as financial reward, support, upkeep of their wellbeing as well as career opportunities.

A breach of psychological contract occurs when workers (in this case, soldiers) feel that the organisation (i.e. the SANDF) have failed them in compliance with its obligations (Chambel & Oliviera-Cruz, 2010). This results in a lack of predictability and control, a sense of deprivation, and even emotionally strong responses, which all contribute to reduced job engagement as well as possible burnout (Vermetten et al., 2014). An even greater concern for the organisation is that these responses, coupled with the demanding work environments, may also be conducive to counterproductive work behaviour and indiscipline (Campbell & Nobel, 2009; Chambel & Oliviera-Cruz, 2010; Tucker et al., 2009).

When a soldier deploys, it inevitably entails separation from his or her family. The process of establishing the parent as a reliable source of comfort and reassurance can be affected and the security of the parent-child relationship may be compromised (Paley et al., 2013).

Considering the current nature of PSO where soldiers are frequently involved in ambushes or attacks, families may experience heightened stress, which would normally be associated with combat-related deployments (Hollingsworth, 2011; Williamson, 2015). Just as deployments affect relationships at home, stressors could serve as a distraction for members, which may compromise their effectiveness and safety (Ferero et al., 2015). The length of the deployment serves as a further indicator of the influence of deployment on families: the longer the deployment, the more ingrained the additional roles and responsibilities, and the greater the accumulation of worries, fears and resentment (Paley et al., 2013).

Some positive experiences reported in studies are aspects such as close relationships with local people by working together and sharing knowledge, feeling connected to the bigger picture to which the soldier contributes, comradeship amongst the soldiers and officers of the unit as well as feeling rewarded by doing good for the local people (see Runge et al., 2020; Schok et al., 2008). Other positives are access to healthcare for the whole family, the opportunity for advancement of the career of a soldier, which will result in increased pay benefits, which also positively influences the family (Schok et al., 2010). Furthermore, members who can find meaning in processing deployment events report more self-confidence, express greater appreciation for family and friends, and also believe that the experience had expanded their horizons and personal growth (Schok et al., 2010; Schok et al., 2008); thus, all placing the individual and the family in a better position than before the deployment.

Combat-related stressors and military operations are synonymous with the term 'posttraumatic stress disorder' (PTSD), as well as the high prevalence of major depressive disorder, generalised anxiety disorder, alcohol misuse, dependence and suicidal ideation (MacDonald et al., 1999). Most of the literature generated in the SANDF and other militaries is focused on the exposure to hazards and the influence of traumatic events during deployments (see Litz, 2004; Runge et al., 2020; Van Wijk & Martin 2021).

Soldiers who are exposed to death, destruction and harm toward powerless populations are at a great risk of developing symptoms of distress (Bramsen et al., 2000). Furthermore, feelings of powerlessness as a result of the mandate of a mission could also affect soldiers' emotions negatively when they are faced with witnessing atrocities against the local population where they have no mandate to intervene (Rosebush, 1998; Shigemura & Nomura, 2002). An example of soldiers being subjected to the suffering of the local population is, for instance, incidents in the Darfur region, where small children - often malnourished - have to walk with their mothers for long hours in the heat to fetch water.

The SANDF has also made a call for more women to be part of front-line operations, which places women at a greater risk of developing PTSD together with the unique stressors that women face in military operations (Chaumba & Bride, 2010). In research, these unique stressors can be categorised as intrinsic, extrinsic and organisational dimensions. Examples of these are gender violence dimensions, family dimensions, cultural dimensions, physiological dimensions, psychological dimensions and sexual dimensions (Hoge et al., 2007; Tarrasch et al., 2011; Walsh, 2009). Various angles toward the scourge of PTSD in militaries therefore have to be re-evaluated, as the notion used to be that mostly men develop PTSD in militaries (Crum-Cianflone & Jacobson, 2014).

Together with the unique challenges of PSO and the psychological impact on soldiers, these operations also offer circumstances for psychological growth (Newby et al., 2005). Post-traumatic growth is not resilience, which is a person's ability to bounce back after adversity; rather, post-traumatic growth refers to the process (which usually takes a long time) during which people are faced with adversity and endure psychological struggles that challenge their being (Collier, 2016). After this process, people usually have learnt new insights about themselves and the way they view the world, which translates to psychological growth (Park et al., 2021).

In addition, the underutilised term "peacekeeper stress syndrome" (Weisaeth & Sund, 1982 in Britt & Adler, 2003, p. 218) has uniquely been coined within the context of PKOs. 'Peacekeeper stress syndrome' was first described in 1979 in a Norwegian PKO and, since then, it has been reported in more than 10 multinational UN PKOs (Shigemura & Nomura, 2002). What sets a PKO apart from the trauma experienced by war is the cognitive processing of soldiers during these types of operations, namely humanitarian assistance, restoration and promotion of sustainable peace (Raju, 2014). Soldiers' thinking about the rationale of PKO operations versus that of conventional warfare is different, and therefore stressors are experienced differently, which adds to the experience of the soldier on a cognitive and emotional processing level, which in turn facilitates psychological growth.

Aim

The aim of the study was twofold, namely firstly, to explore and compare the positive and negative subjective deployment experiences of SANDF soldiers during two distinctly different mission areas; and secondly, to provide a guiding framework based on these experiences, which could be utilised to by the organisation to predict soldiers' deployment experiences in terms of three spheres of functioning. This novel framework of booster and stressor matrices provides the organisation with a valuable tool for informing interventions about the human factor during PSOs, and therefore contributing to the optimal functioning and psychological wellbeing of soldiers during deployment.

Methodology

The study adopted a survey design utilising a qualitative approach focusing on retrospective data. The data stemmed from the Psychological Demobilisation Questionnaire (PDQ) developed by psychologists in the SANDF and amended by the authors. This questionnaire has been utilised in its amended form for the past 12 years; therefore, the same version of the PDQ was administered to respondents in both missions. The questionnaire is circulated as part of the demobilisation process before soldiers return from the mission area. The current data were collected from SANDF members from both combat service support and combat forces from two different mission areas, namely Operation Cordite and the FIB. The deployments were both one year in duration.

Survey

The PDQ was developed to explore the psychological dynamics of deployment. Questions tap into different aspects, which may potentially have a psychological impact on deployed soldiers and consequently influence individual and group functioning. For the purposes of the study, only the demographical information provided as well as two open-ended questions were utilised. Individuals were asked to report in writing on what they felt was best (i.e. boosted their experience) and worst about the deployment. No limitation was placed on the number of responses the individual could provide.

Sample

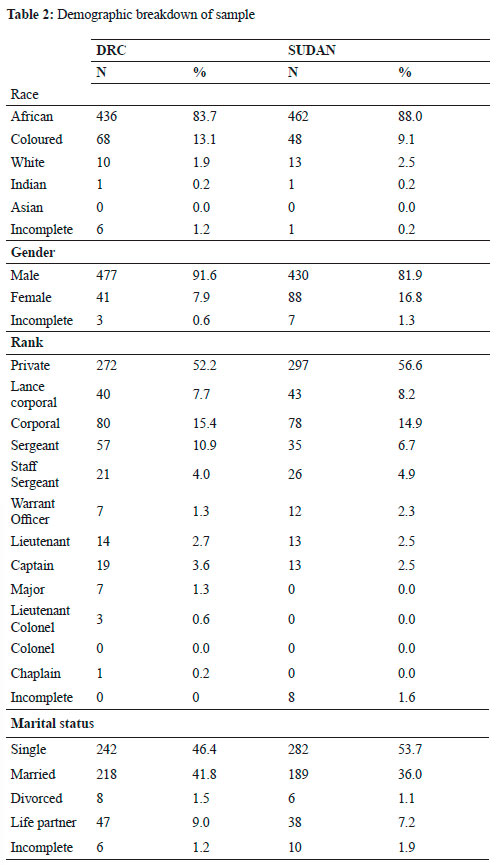

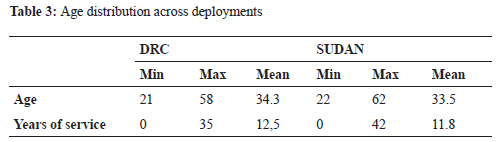

A total of 1 046 soldiers participated in the study. Tables 2 and 3 below illustrate the composition of the sample from Operation Cordite (n=525) and FIB (n=521) missions respectively.

Analyses

The data for the study were analysed by means of thematic analysis. The survey data were recorded, coded and analysed. Open coding was utilised. Following the initial coding process, labels were assigned to the various codes. These labels were consequently analysed and grouped according to the main themes identified within the data. The main themes were firstly compared in terms of similarity as well as uniqueness for each mission based on simple content comparison. The main themes are presented as percentages to gain insight into the frequency of the themes. These frequencies provide the profile of the negative and positive deployment experiences of each mission. Please note that all responses are reproduced verbatim and unedited.

Results

The results for both mission areas will be presented, firstly the positive deployment experiences will be considered, followed by the negative experiences.

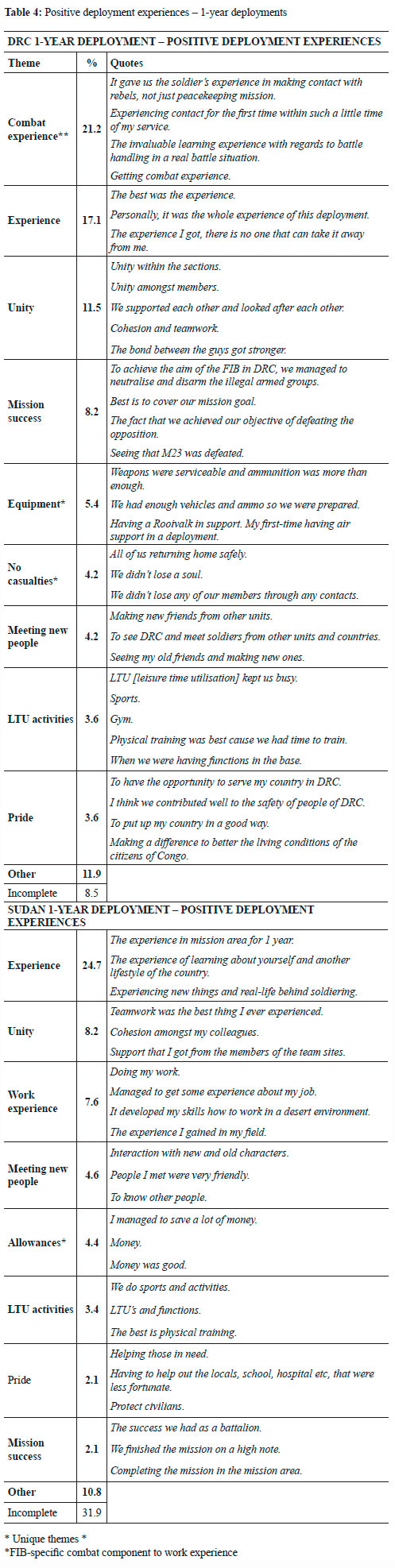

Table 4 indicates themes, along with typical responses associated with the theme, about positive deployment experiences of deployment. When comparing the data for both theatres of operation, seven main themes were evoked. These were:

• 'Experience' (related to the deployment experience in general)

• 'Unity'

• 'Work experience'

• 'Meeting new people'

• 'LTU activities'

• 'Pride' in the mission'

• 'Mission success'.

It is important to note that in terms of the FIB, 'Work experience' includes combat-related experience due to the mandate of the mission.

Unique positive deployment experiences were evident in both data sets. Within the FIB, these were:

• 'No casualties'

• 'Equipment'

• serviceable equipment

• different types of weapons

• serviceable and available vehicles.

In this regard, the deployment and availability of the "Rooivalk attack helicopter" (Participant D56) in the mission area were specifically highlighted as a positive contributor to soldier morale. Operation Cordite respondents highlighted 'Allowances' as the only unique positive aspect during this deployment. Considering the varying nature of the two deployments, these unique themes may be attributed to the mandate of the deployment as well as specific incidents or occurrences during the deployment period.

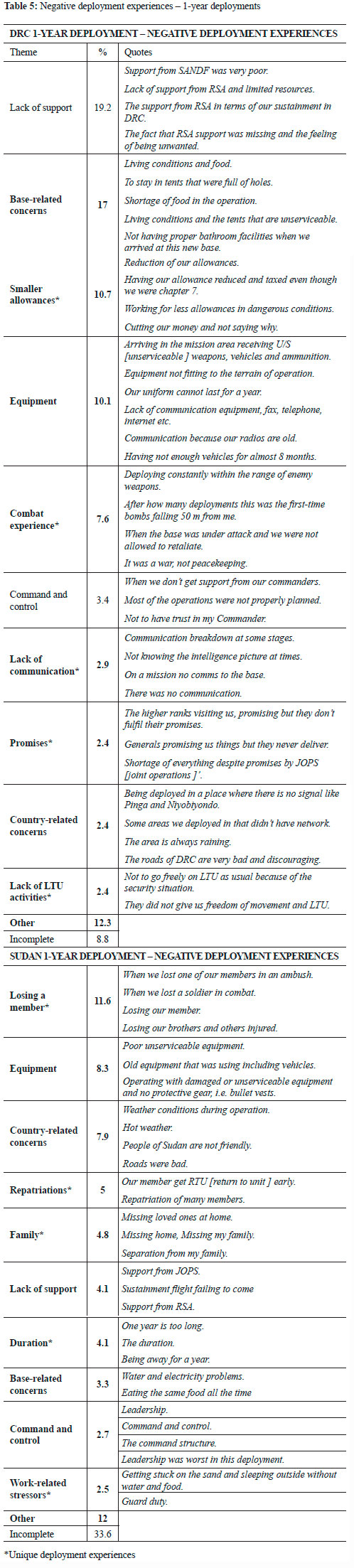

Table 5 highlights themes, along with responses associated with negative experiences during one year deployments, unique responses are indicated by the asterisk.

When comparing the negative deployment experiences of soldiers, five main themes for both theatres of operation were identified as presented in Table 5:

• 'Lack of support'

• 'Equipment'

• 'Base-related concerns'

• 'Country-related concerns'

• 'Command and control'.

Similar concerns for both theatres emerged concerning base-related aspects in terms of the food that was received, accommodation, and base facilities. Similarly, country-related aspects also manifested as negative experiences across both theatres of operation, with each country presenting challenges in terms of the environment and infrastructure, such as travelling to areas of responsibility on poor roads where vehicles break frequently.

Greater variance was evident in terms of the unique themes related to the negative deployment experiences of soldiers as opposed to the positive deployment experiences. Within the DRC unique themes were:

• 'Smaller allowances'

• 'Promises' and perceived lies from higher structures in the SANDF

• 'Lack of communication'

• 'Lack of LTU activities'.

In contrast, within the Darfur deployment, the pertinent unique themes centred on:

• 'Losing a member'

• 'Repatriation'

• 'Family'

• 'Duration'

• 'Work-related stressors'.

Whilst a strong collation between the general stressors was found in both deployment areas, distinct incidents during each of the missions contributed significantly to the varying nature of the experience of soldiers.

Discussion

This study compared the positive and negative deployment experiences of SANDF members during two different missions. The types of positive and negative deployment experiences were similar to those reported on in previous research across various countries and missions (see Runge et al., 2020). It was found that the majority of the positive experiences of deployed personnel were consistent across both the DRC and Darfur deployments with minor variations in its perceived weighting to members. According to the main themes, the respondents valued the work and combat experience, the experience of deployment, the unity, mission success, meeting new people, the leisure time utilisation (LTU) activities. They furthermore had a sense of helping and reported pride in the execution of their duties during both deployments.

These findings are in keeping with PSO research (see Karney & Crown, 2011; Morris-Butler et al., 2018; Raju, 2014), which found that contrary to the popular narrative that deployment is a harmful experience, there are significant positive experiences reported by deployed military personnel. Focusing on the positive experiences associated with military service, which are often under-reported, furthermore validates the sense of meaning derived from military deployment by soldiers. The identification of positive experiences can be seen as part of a meaning-making process. This sense of meaning-making furthermore serves as a protective factor from the negative effects of stressors among deployed soldiers (Seol et al., 2020).

Unique positive experiences associated with the DRC mission were combat experience, ample and serviceable equipment, the support of the 'Rooivalk' attack helicopters from South Africa, and the fact that no casualties were suffered during the deployment. It is perhaps surprising that these are a reflection of the FIB, which had a robust offensive mandate. Our findings are thus consistent with the view that a soldier is truly at peace during 'wartime' where they know what is expected of them and they have trained accordingly. In contrast to this, increased logistical, financial and operational support is associated with a traditional military mandate, such as PSOs. This operational support, in turn, contributed significantly to reported positive deployment experiences.

Positive deployment experiences during the Darfur mission were associated with 'Remunerative rewards' as a unique main theme. A specific association with the nature of the operations is evident, as the financial benefit is consistent with previous findings associated with PKO (see Raju, 2014). The unique positive experiences indicate a relationship with the nature of the operation, PE or PK. This could also be indicative of the unique requirements of deployed personnel during missions with different mandates. Psychological requirements during PE are specified as mental toughness, channelled aggressiveness, physical fitness; and during PK, self-discipline, diplomacy, negotiation skills, tolerance for boredom, and understanding of the conflict (Densmore, 2004).

In line with previous research, participants across both theatres of operation reported negative deployment experiences related to support, living conditions, vehicles and equipment, a lack of information as well as a lack of command and control (Bartone et al., 1998; Coll et al., 2011; King et al., 2006; Van Dyk, 2009). The duration of the deployment can furthermore be seen as a catalyst that served to amplify the negative experiences of soldiers during deployment.

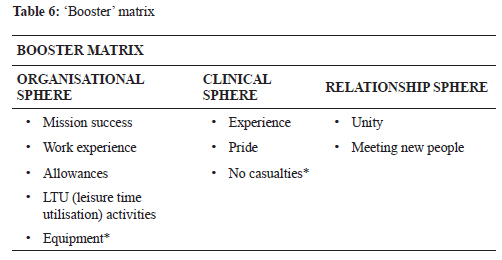

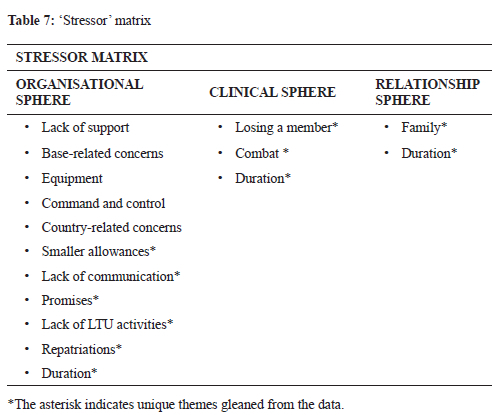

The themes of positive and negative experiences can be categorised in terms of the sphere of functioning within which the deployment experience has an impact. A positive deployment experience can therefore be described as a 'booster' during deployment whereas a negative deployment experience can be described as a 'stressor'. The design of a 'booster' and 'stressor' matrix based on the findings of this research is presented in Tables 6 and 7. These matrices provide a practical and accessible guiding framework to military commanders on how to 'boost' or 'mitigate' some of the experiences of their deployed force.

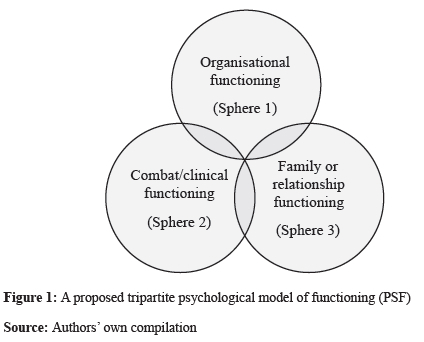

In the examination of the booster (Table 6) and stressor (Table 7) matrices, it is clear that the majority of the positive and negative themes are rooted in the organisational sphere of functioning. Whilst this may be the case, it is important to note that the spheres are not mutually exclusive. Elements within one sphere may have a direct influence on other spheres (see Figure 1). The duration of the deployment presents an example of this. Whilst the duration of the deployment is prescribed by the organisation and the tenets of mission requirements, the outcome of a 1 year deployment may have a marked effect on the clinical sphere of functioning of the individual as well as on his or her relationships with family and friends, and therefore the relationship sphere of functioning.

The matrices thus merely provide a vigorous demarcation of the various 'boosters' and 'stressors', which may have an effect on the psychological wellbeing of soldiers within the various spheres of functioning.

A deeper interrogation of the underlying categorisation of the themes reveals that these can be distilled into a multi-dimensional psychological model of functioning (see Figure 1 below) as a result of the deployment experiences. The model is conceptualised by categorising the positive and negative deployment experiences of respondents in this research article in terms of three spheres of functioning. These spheres categorise the deployed soldier's deployment experiences in these three spheres, which are not mutually exclusive but can overlap as seen in the data. These spheres of functioning are the organisational, clinical and relationship spheres. Through this categorisation of the themes, the tripartite model assists with the practical application (planning, intervention) of these findings within the deployment context. In this configuration, the tripartite model provides a novel tool for commanders and the force employer to strategise and plan for experiences the soldier may encounter.

The organisational sphere accounted for the majority of both positive and negative deployment experiences of soldiers. This challenges popular convictions that the majority of studies focus on peacekeepers' wellbeing through analyses of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (see Vasterling et al., 2015). In this sphere, most elements are under direct control and influence of the military commander. The focus areas should be good leadership, command and control, effective communication, payment of financial rewards, ensuring serviceable vehicles and base-related concerns (create conditions conducive to living and food). These factors are nothing new, and are already on the radar of the commander.

The contribution of the proposed model lies in the subjective data of soldiers presented as evidence to commanders of how important these aspects are to them. Within the organisational sphere, the psycho-social team has a role to play through the implementation of a structured programme of functions and LTU activities. The role of the military commander would be to instil a sense of pride, to emphasise and 'boost' the contribution his or her contingent is making, and in essence to highlight the difference his or her troops are making in the community. This gives evidence of the phenomenon of intrinsic rewards, which is viewed as the most powerful predictor of overall work satisfaction across occupational groups (see Lang et al., 2010; Renard & Snelgar, 2016).

The clinical sphere is characterised by the elements of loss and absence (Maguire et al., 2013), and personnel are typically shielded from these elements by using internalisation of positive experiences, which serves as a protective element in terms of psychological wellbeing. Clinicians and psycho-social teams should take cognisance of these themes. The clinical sphere is expected to have a significant influence during the post-deployment phase, where the protective hold of the 'booster' elements will start to wane.

The unity, cohesion and teamwork within the relationship sphere play a significant role in keeping the force together. Soldiers typically rely on their social network of family and friends to serve as a support network at home. In the absence of friends and family, the stimulation of new relationships and unit cohesion provides the social structure and support, which is a basic human need. The influence of this sphere during deployment is more apparent when the social support structure in the form of unit cohesion is absent. Furthermore, in accordance with existing literature, the influence of this sphere is likely to increase as soldiers engage in reintegration with their families after deployment (Esposito-Smythers et al., 2011). Family members should be educated and informed about the role that they can play in reducing stress during military deployments, and interventions should be tailored to fit the soldiers' context (Ferero et al., 2015).

Conclusion

This research studied the deployment experiences of SANDF personnel across two different missions. Positive and negative deployment experiences were examined, and these experiences were found to be consistent across both missions. The positive deployment experiences were found to be 'Experience related to deployment', 'Unity', 'Work experience', 'Meeting new people', 'LTU activities', 'Pride' in the mission, 'Mission success' and 'Allowances'.

The negative deployment experiences related to 'Lack of support', 'Equipment', 'Base-related concerns', Country-related concerns', 'Lack of LTU' and 'Command and control'. The novel contribution of this research lies within the revelation that military commanders have a significant sphere of influence and control over the experiences (positive and negative) of the deployed PSO force.

This study provides military leaders with information and practical strategies to 'boost' the mental readiness of deployed members across operations and to plan for or mitigate possible negative outcomes utilising the 'stressor' matrix. The matrices should be included during the deployment planning phase to ensure that the focus is on reducing stressors during deployment as well as planning for the inclusion of 'booster' items, such as projects to help the local community and interactions with new people from other serving forces. The main spheres of influence are the organisational, clinical and relationship spheres. It is critical to focus on all three spheres during all phases of deployment to enhance and sustain the mental readiness of deployed personnel. Military leaders at all levels have a key role to play in the deployed soldier's experience within the theatre of operation.

Limitations

The study relied on a cross-sectional survey design where data were collected during a specific phase of deployment. The findings are therefore specific to the late deployment phase and should not be generalised to other phases of deployment. Future research could add to an understanding of these stressors over time, by introducing a time lag during assessment to measure the experiences of soldiers during different phases of deployment, to extend the current scope of the current research, and ultimately add more value to the wellbeing of soldiers.

References

Bartone, P. T., Adler, A. B., & Vaitkus, M. A. (1998). Dimensions of psychological stress in peacekeeping operations. Military Medicine, 163(9), 587-593. [ Links ]

Bramsen, I., Dirkzwager, A. J. E., & Van der Ploeg, H. M. (2000). Predeployment personality traits and exposure to trauma as predictors of posttraumatic stress symptoms: A prospective study of former peacekeepers. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 1115-1119. [ Links ]

Britt, T. W., & Adler, A. B. (Eds). (2003). The psychology of the peacekeeper: Lessons from the field. In Psychological dimensions to war and peace. Praeger. https://doi.org/10/1163/18754112-90000046 [ Links ]

Bruwer, N., & Van Dyk, G. A. J. (2005). The South African peacekeeping experience: A comparative analysis. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 31 , 30-39. [ Links ]

Campbell, D. J., & Nobel, O. B. Y. (2009). Occupational stressors in military service: A review and framework. Military Psychology, 21(2), 47-67. [ Links ]

Chambel, M. J., & Oliveira-Cruz, F. (2010). Breach of psychological contract and the development of burnout and engagement: A longitudinal study among soldiers on a peacekeeping mission. Military Psychology, 22, 110-127. [ Links ]

Chaumba, J., & Bride, B. E. (2010). Trauma experiences and posttraumatic stress disorder among women in the United States military. Social Work in Mental Health, 8(3), 280-303. [ Links ]

Coll, J. E., Weiss, E. L., & Yarvis, J. S. (2011). No one leaves unchanged: Insights for civilian mental health care professionals into the military experience and culture. Social Work in Health Care, 50(7), 487-500. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2019.168480 [ Links ]

Collier, L. (2016). Growth after trauma: Why are some people more resilient than others - and can it be taught? American Psychological Association: Monitor on Psychology, 47(10), 48. [ Links ]

Crum-Cianflone, N. F., & Jacobson, I. (2014). Gender differences of postdeployment posttraumatic stress disorder among service members and veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts. Epidemiologic Reviews, 36(1), 5-18. [ Links ]

Densmore, M. C. (2004). Warfighter-peacekeeper psychological aptitude: Assessing the soldier's psychological aptitude for effective performance in combat or traditional peacekeeping operations [Unpublished master's thesis]. The College of William and Mary in Virginia. [ Links ]

Esposito-Smythers, C., Wolff, J., Lemmon, K. M., Bodzy, M., Swenson, R. R., & Spirito, A. (2011). Military youth and the deployment cycle: Emotional health consequences and recommendations for intervention. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(4), 497-507. https://doi:10.1037/a0024534 [ Links ]

Ferero, A. M., Springer, P., Hollist, C., & Bischoff, R. (2015). Crisis management and conflict resolution: Using technology to support couples throughout the deployment. Contemporary Journal of Family Therapy, 37(1), 281-290. https://doi:10.1007/s10591-015-9343-9 [ Links ]

Forbes, D., Pedlar, D., Adler, A. B., Bennet, C., Bryant, R., Busuttil, W., Cooper, J., Creamer, M. C., Fear, N. G., Heber, A., Hinton, M., Hopwood, M., Jetly, R., Lawrence-Wood, A., McFarlane, A., Metcalf, O., O'Donnell, M., Phelps, A., Richardson, J. D., Wessely, S. (2019). Treatment of military-related post-traumatic stress disorder: Challenges, innovations and the way forward. International Review of Psychiatry, 31(1), 95-110. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2019.1595545 [ Links ]

Hoge, C. W., Clark, J. C., & Castro, C. A. (2007). Commentary: Women in combat and the risk of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression. International Journal of Epidemiology, 36, 327-329. [ Links ]

Hollingsworth, W. G. (2011). Community family therapy with military families experiencing deployment. Contemporary Family Therapy, 33(3), 215-228. [ Links ]

IndexMundi. (N.d.). Sudan vs. Democratic Republic of the Congo. https://www.indexmundi.com/factbook/compare/south-sudan.democratic-republic-of-the-congo [ Links ]

Karney, B. R., & Crown, J. S. (2011). Does deployment keep military marriages together or break them apart? Evidence from Afghanistan and Iraq. In S. Wadsworth & D. Riggs (Eds.), Risk and resilience in U.S. military families (pp. 23-45). Springer. https://doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-7064-02 [ Links ]

Kgosana, C. M., & Van Dyk, G. (2011). Psychosocial effects of conditions of military deployment. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 21(2), 323-326. [ Links ]

King, L. A., King, D. W., Vogt, D. S., Knight, J., & Samper, R. E. (2006). Deployment risk and resilience inventory: A collection of measures for studying deployment-related experiences of military personnel and veterans. Military Psychology, 18(2), 89-120. [ Links ]

Knobloch, L. K., Pusateri, K. B., Ebata, A. T., & McGlaughlin, P. C. (2014). Communicative experiences of military youth during a parent's return home from deployment. Journal of Family Communication, 14(4), 291-309. [ Links ]

Lang, J., Bliese, P. D., Adler, A., & Holzl, R. (2010). The role of effort-reward imbalance for reservists on a military deployment. Military Psychology, 22(4), 524-541. https://doi:10.1080/08995605.2010.521.521730 [ Links ]

Litz, B. T. (2004). The stressors and demands of peacekeeping in Kosovo: Predictors of mental health response. Military Medicine, 169, 198-206. [ Links ]

Lotze, W., De Coning, C., & Neethling, T. (2015, September 9). Contributor profile: South Africa. International Peace Institute. https://www.ipinst.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/ipi-pub-ppp-South-Africa.pdf [ Links ]

MacDonald, C., Chamberlain, K., & Long, N. (1999). Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and its effects in Vietnam veterans: The New Zealand experience. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 24(2), 63-68. [ Links ]

Maguen, S., Litz, B. T., Wang, J. L., & Cook, M. (2004). The stressors and demands of peacekeeping in Kosovo: Predictors of mental health response. Military Medicine, 169(3), 198-206. [ Links ]

Maguire, K. C., Heinemann-LaFave, D., & Sahlstein, E. (2013). To be so connected, yet not at all: Relational presence, absence, and maintenance in the context of wartime deployment. Western Journal of Communication, 77(3), 249-271. https://doi:10.1080/10570314.2012.757797 [ Links ]

Martin, G. (2019, April 24). SANDF peacekeeping efforts continue in Africa. defenceWeb. https://www.defenceweb.co.za/joint/diplomacy-a-peace/sandf-peacekeeping-efforts-continue-in-africa/ [ Links ]

Morris-Butler, R., Jones, N., Greenberg, N., Champion, B., & Wessely, S. (2018). Experiences and career intentions of combat-deployed UK military personnel. Occupational Medicine, 68(1), 177-183. https://doi:10.1093/occmed/kqy024 [ Links ]

Newby, J. H., McCarroll, J. E., Ursano, R. J., Zizhong, F., Shigemura, M. D., & Tucker-Harris, Y. (2005). Positive and negative consequences of a military deployment. Military Medicine, 170(10), 815-819. [ Links ]

Paley, B., Lester, P., & Mogil, C. (2013). Family systems and ecological perspectives on the impact of deployment on military families. Clinical Child Family Psychology, 16, 245-265. [ Links ]

Park, J., Lee, J., Kim, D., & Kim, J. (2021). Posttraumatic growth and psychological gains from adversities of Korean special forces: Consensual qualitative research. Current Psychology [Advance online publication]. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02308-z [ Links ]

Raju, M. S. V. K. (2014). Psychological aspects of peacekeeping operations. Industrial Psychiatry Journal, 23(2), 149-156. https://doi:10.4103/0972-6748.151693 [ Links ]

Renard, M., & Snelgar, R. J. (2016a). How can work be designed to be intrinsically rewarding? Qualitative insights from South African non-profit employees. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 42(1), a1346. https://dx.doi.org/1-.4102/sajip.v42i1.1346 [ Links ]

Renard, M., & Snelgar, R. J. (2016b). Measuring positive, psychological rewards: The validation of the Intrinsic Work Rewards Scale. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 26(3), 209-215. [ Links ]

Rosebush, P. A. (1998). Psychological intervention with military personnel in Rwanda. Military Medicine, 163(8), 559-563. [ Links ]

Runge, C. E., Waller, M. J., Moss, K. M., & Dean, J. A. (2020). Military personnel ratings of a deployment and their positive and negative deployment experiences. Military Medicine, 185(9), 1615-1623. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usaa109 [ Links ]

Salaun, N. (2019). The challenges faced by UN peacekeeping missions in Africa. The Strategy Bridge. https://thestrategybridge.org/the-bridge/2019/10/ [ Links ]

Schok, M. L., Kleber, R. J., & Boeije, H. R. (2010). Men with a mission: Veterans' meaning of peacekeeping in Cambodia. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 15(4), 279-303. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325020903381873 [ Links ]

Schok, M. L., Kleber, R. J., Elands, M., & Weerts, J. M. P. (2008). Meaning as a mission: A review of empirical studies on appraisals of war and peacekeeping experiences. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 357-365. https://doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2007.04.005 [ Links ]

Seol, J. H., Park, Y., Choi, J., & Sohn, Y. W. (2021). The mediating role of meaning in life in the effects of calling on posttraumatic stress symptoms and growth: A longitudinal study of navy soldiers deployed to the Gulf of Aden. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 599109. https://doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.599109 [ Links ]

Shigemura, J., & Nomura, S. (2002). Mental health issues of peacekeeping workers. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 56(5), 483-491. [ Links ]

South African Army. (N.d.). Joint warfare publication 106 Part 2: Peace support operations. Author. [ Links ]

Sun-tzu, & Griffith, S. B. (1964). The art of war. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [ Links ]

Tarrasch, R., Lurie, O., Yanovich, R., & Moran, D. (2011). Psychological aspects of the integration of women into combat roles. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(2), 305-309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.10.014 [ Links ]

Tucker, J. S., Sinclair, R. R., Mohr, C. D., Adler, A. B., Thomas, J. L., & Salvi. A. D. (2009). Stress and counterproductive work behavior: Multiple relationship between demands, control and soldier indiscipline over time. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 14(3), 257-271. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014951 [ Links ]

Van Dyk, G. A. J. (2009). The role of military psychology in peacekeeping operations: The South African National Defence Force as an example. Scientia Militaria, 37(1), 113-135. https://doi.org/10.5787/37-1-62 [ Links ]

Van Wijk, C. H. (2011). The Brunel Mood Scale: A South African norm study. South African Journal of Psychiatry, 17(2), 44-54. [ Links ]

Van Wijk, C. H., & Martin, J. H. (2021). Promoting psychological adaptation among navy sailors. Scientia Militaria, 49(1), 23-34. https://doi:10.5787/49-1-1260 [ Links ]

Van Wijk, C. H., Martin, J. H., & Hans-Arendse, C. (2013). Clinical utility of the Brunel Mood Scale in screening for post-traumatic stress in a military population. Military Medicine, 178(4), 372-374. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-12-00422 [ Links ]

Vasterling, J. J., Taft, C. T., Proctor, S. P., MacDonald, H. Z., Lawrence, A., Kalell, K., Kaiser, A. P., Lee, L. O., King, D. W., King, L. A., & Fairbank, J. A. (2015). Establishing a methodology to examine the effects of war-zone PTSD on the family: The Family Foundations Study. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 24(2), 143-155. https://doi:10.1002/mpr.1464 [ Links ]

Vermetten, E., Greenberg, N., Boeschoten, M. A., Delahije, R., Jetly, R., Castro, C. A., & McFarlane, A. C. (2014). Deployment-related mental health support: Comparative analysis of NATO and allied ISAF partners. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5(1), a23732. http://doi:10.3402/eiptv5.23732 [ Links ]

Walsh, B. (2009, January 13). When Mommy comes marching home: Women in the military are developing PTSD at alarming rates. BU Today. https://www.bu.edu/2009/when-mommy-comes-marching-home [ Links ]

WeisEeth, L., & Sund, A. (1982). Psychiatric problems in UNIFIL and the U.N. soldier's stress syndrome. International review of the Army, Navy and Air Force Medical Services, 55, 109-116. [ Links ]

Wilen, N., & Heinecken, L. (2017). Peacekeeping deployment abroad and the self-perceptions of the effect on career advancement, status and reintegration. International Peacekeeping, 24(2), 236-253. https://doi.org/10.1080/13533312.2016.1215247 [ Links ]

Williamson, E. (2015). The experiences of airborne section leaders during peacekeeping operations: A South African perspective [Unpublished master's dissertation]. University of Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Zungu, D., & Visagie, N. (2020). All eyes on Sudan: The journey of female psychologists in the theatre of operation. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 46(1), a1739. https://doi.org/10.4102/saiip.v46i0.1739 [ Links ]

1 Lt Col Nicolette Visagie has served in the SANDF for the past 18 years. She is a trained clinical psychologist but a soldier at heart. She was the first psychologist to volunteer to deploy for more than three months in Sudan. She deployed to the Congo and Burundi numerous times and formed part of the mission to repatriate citizens from Wuhan. She headed a small section of specialist, psychologists for 11 years. The section's work has been invaluable to the SANDF. She is now responsible for managing psychologists in theatres of operation, as well as operationalising the hostage negotiation capability.

2 Maj RA du Toit holds a Master's degree in Research Psychology from the University of the Western Cape. Having joined the Military Psychological Institute in 2011, he has developed a passion for the operational environment and has been a member of the Human Factor Combat Readiness section. He had the privilege of deploying to the DRC in both 2013 and 2014 to conduct operational research in the field both prior to and with the deployment of the first Force Intervention Brigade. His main areas of interest include behavioural permutations and stress models during Peace Support and Peacekeeping missions, the design and implementation of selection tools for specialist selections and specialist/operational research.

3 Stephanie Joubert is an Industrial Psychologist working at the Human Factor Combat Readiness Section of the Military Psychological Institute. Her work focuses specifically on providing psychological interventions, services, training, and research that is necessary to contribute to the wellness of deploying soldiers. Stephanie has a passion for the military environment as well as an interest in optimising both organisational and individual functioning within this setting. She has presented and published academic research related to this field. She is currently focusing her efforts on optimising organisational functioning through strategic management and planning processes.

4 David Schoeman is an Industrial Psychologist at the Military Psychological Institute, where he is staffed in the Human Factor Combat Readiness department since 2012. His work is mostly focused on operational aspects that influence the functioning of internal and external deployed military personnel. Furthermore he is completing his PhD on performance psychology characteristics of SANDF military personnel. He is also a qualified paratrooper and has conducted numerous research projects within the airborne environment. His passion lies in the development of individuals in order to reach their fullest potential. He also has a passion for wildlife, and values experiences above possessions.

5 Didi Zungu is an Industrial Psychologist at the Military Psychological Institute within the South African National Defence Force. This placement included an external operational deployment to Sudan (Darfur) which she completed during 2013. She received a bachelor's degree in Human Resource Management from the University of Pretoria, an honour's and master's degree in Industrial and Organisational Psychology from the University of South Africa. Her research fields of interest are within operational psychology, military deployment experiences as well as the impact of military deployments on relationships and families.